Abstract

Background:

Family caregivers might enhance veteran engagement in health and nonhealth services (i.e., vocational/educational assistance).

Purpose:

To describe how veterans with disabilities perceive their recovery needs, identify types of social support from caregivers that help veterans engage in Veterans Affairs (VA) health and nonhealth services, and explore participant views of VA institutional support for caregivers to help veterans engage in these services.

Methods:

Joint in-depth qualitative interviews with U.S. veterans and family caregivers (n = 26).

Findings:

Caregivers performed social support functions that helped veterans engage in health and vocational/educational services and institutional support from VA enhanced caregivers’ capacity.

Discussion:

Caregivers are well positioned to align health and nonhealth services with patient needs to enhance recovery. Staffing a point person for caregivers within the health system is key to help families develop a coordinated plan of treatment and services to improve patient success across health and nonhealth domains. Nurses are well suited to perform this role.

Keywords: Family caregivers, Health system, Persons with disabilities, Qualitative research, Social support, U.S. Department of Veterans, Affairs, Vocational assistance services

Introduction

Since 2001, more than 3.1 million veterans have returned from the Post-9/11 wars (Holder, 2018). Many of these veterans are in their prime working years and upon their return they seek to continue their education and find employment. However, many Post-9/11 veterans come home with disabling service-related conditions, such as traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which can negatively impact their physical and emotional health and cognitive function (Meterko et al., 2012). As a result, seeking postsecondary degrees and finding or maintaining employment may be a challenge; these difficulties can lead to poor economic and health outcomes (Erbes, Kaler, Schult, Polusny, & Arbisi, 2011; Fischer et al., 2015; Kukla, Rattray, & Salyers, 2015; Resnik, Borgia, Ni, Pirraglia, & Jette, 2012; Sayer et al., 2010).

Veterans report a desire for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to provide services to address all aspects of their recovery (Carlson et al., 2018; Sayer et al., 2010). The VA is the umbrella organization that includes the (a) Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which delivers a variety of health services, and (b) Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), which administers financial benefits and provides job and education assistance. As part of its mental health services, VHA offers supported employment (Pogoda, Levi, Helmick, & Pugh, 2017), an evidence-based vocational rehabilitation program that helps individuals with disabilities find and maintain competitive, community-based employment (Bond & Drake, 2014; Resnik & Allen, 2007). Relative to other vocational programs, supported employment is associated with higher likelihood of attaining work and higher income (Davis et al., 2018; Twamley et al., 2013). VBA offers Vocational Rehabilitation & Employment (VR&E) services to help with job training through educational assistance and skills training workshops, employment accommodations, and coaching. VBA also offers educational assistance through the Post-9/11 GI Bill, which provides financial support for postsecondary education.

Recently, VA rolled out the Whole Health approach (Gaudet & Kligler, 2019), which recognizes that health is strongly linked with social supports and activities that bring personal fulfillment, including education and meaningful employment (Administration VH, 2016). The emphasis on Whole Health presents an opportunity for the VA to develop policies to meet the cross-cutting health, educational, and vocational needs of veterans with service-related injuries. However, these needs are not always addressed in a systematic and coordinated manner. Delivery of these services is compartmentalized within distinct VA divisions (i.e., VHA and VBA) and across different program offices within these divisions, which impedes coordinated approaches to care. In addition, few eligible veterans with service-related disabilities use vocational rehabilitation services (Abraham, Ganoczy, Yosef, Resnick, & Zivin, 2014). To effectively meet the needs of veterans with disabilities, VA needs to identify approaches to coordinate the delivery of existing health and vocational services.

In 2010, VA established the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC), a national program that utilizes nurses and social workers to provide education, training, and stipends for family caregivers of veterans who were injured during Post-9/11 military service (Public Law: 111-163). Support from caregivers helps to bridge clinical and home-based care (Van Houtven, Voils, & Weinberger, 2011; Van Houtven et al., 2017), but it is unclear what social support functions (Wills, 1985) caregivers undertake to help veterans engage in health. Moreover, little is known about the role that social support from caregivers might play to increase veteran engagement in under-used vocational services and to align the delivery of health and vocational/educational services to meet veterans’ cross-cutting recovery needs.

Social support theory suggests that social support functions—including informational, instrumental, and information support—might increase use of health and other services by offsetting “stressors”—or barriers—in the process of seeking care (Wills, 1991). For example, increasing patient access to information, encouraging care-seeking behaviors, and helping patients to overcome logistical barriers, such as transportation or scheduling difficulties, can increase patient access to services (Van Houtven et al., 2011).

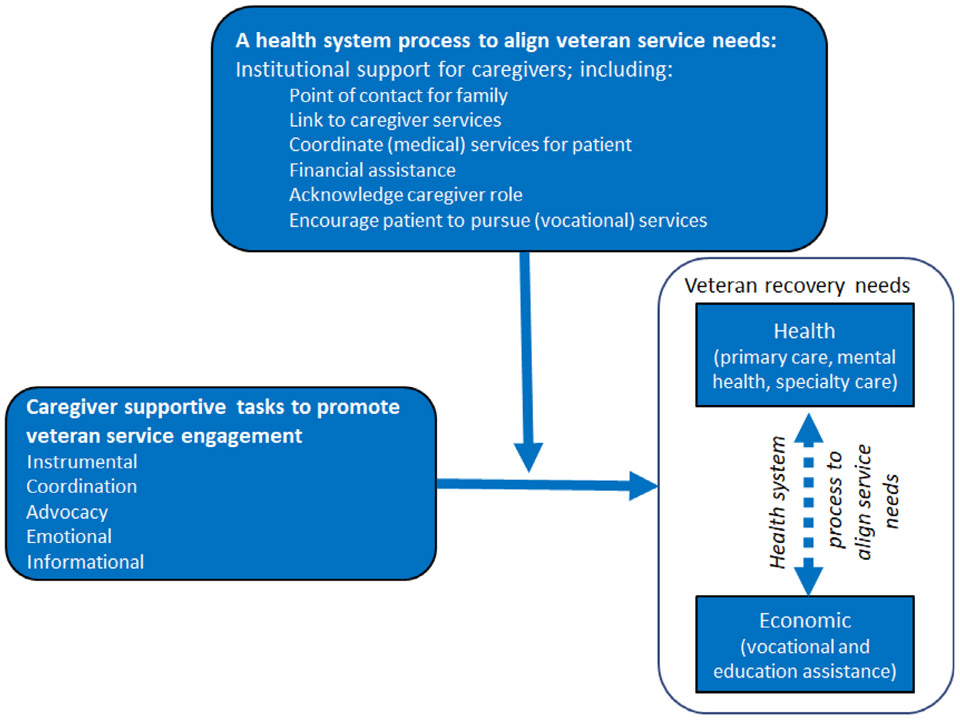

The overall aim of this study is to understand how social support functions performed by family caregivers can help to increase use of health and vocational/educational services for veterans with acquired disabilities (Wills, 1985, 1991). Specifically, the objectives of this study are to (a) describe how veterans with acquired disabilities perceive their own recovery needs and alignment of VA services to meet those needs, (b) identify types of social support from caregivers that have helped veterans to engage in VA health and vocational/educational assistance services (i.e., supported employment, VR&E, or the Post-9/11 GI Bill), and (c) explore whether veterans and caregivers view VA support for caregivers as helpful for assisting veterans to engage in these services. We then apply these findings to an exploratory conceptual map that begins to map a high-level process for how caregivers and institutional support for caregivers might help veterans with disabilities engage in vocational/educational services.

Materials and Methods

Sample Description

We recruited veterans and designated caregivers from an administrative list of a preapproved cohort of caregivers who enrolled in PCAFC for at least 3 months between May 1, 2010 and September 30, 2014; currently the only systematic way to identify family caregivers who provide substantial support to veterans is through this administrative list. Veterans with at least one documented interaction with supported employment, VR&E, or the Post-9/11 GI Bill and whose designated caregiver was willing to participate in the one-time interview were eligible to participate. Veterans who met these criteria received a recruitment letter and a follow-up call from study staff to explain the purpose of the research, to convey the risks and benefits of participating in the study, and to assess eligibility. Interviews occurred between April and September 2018 with subjects who provided verbal consent; each participant received $25. This study was approved by an institutional review board.

Data Collection

We conducted twenty-six 60-min semistructured telephone interviews with veterans and their caregivers; joint interviews are appropriate for studying shared social interactions, such as health care decision-making (Polak & Green, 2016). The interview script was developed and piloted with a VA Veteran and Caregiver Engagement Panel. Interview questions solicited information about veterans’ postmilitary life goals; how the caregiver was involved in helping the veteran to use health care and supported employment, VR&E, and/or the Post-9/11 GI Bill; the role of PCAFC support in the veteran’s use of health and vocational/educational services; and any communication the veteran had with his/her health care team about his/her use of vocational/educational services. Interviews were conducted by two trained interviews (M.S.B. and K.M.) and were digitally recorded and transcribed. Once interviews were completed and each interviewer wrote down notes from the interviews.

Data Analysis

We used applied thematic analysis (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012) to analyze participant responses, which proceeded in three stages. First, we developed structural codes based on domains within the interview guide (e.g., context, role of caregiver in service engagement, role of PCAFC role in service engagement) that were informed by social support theory (Wills, 1991). Two analysts (M.S.B. and K.M.) then reviewed content within these structural codes and came to consensus on an initial set of content codes (e.g., caregiver role in service engagement: instrumental, coordination, and advocacy); this process was repeated as new information emerged and, ultimately, no new codes were identified. The analysts also discussed their own potential biases and relationships with the data to minimize the influence of individual-level perspectives on data analysis and interpretation. Content codes were applied and intercoder agreement was assessed by checking consistency of coding on the first five interviews and then when codes with low intercoder agreement were applied; all coding discrepancies were resolved by discussion. After all data were coded, analysts organized the data and summarized themes; each coder verified the other coders’ summaries. Respondents were not recontacted to ask for feedback on the transcripts or findings to avoid undue burden. ATLAS.ti analytical software was used to apply and organize codes.

Results

Describe statistics for the study sample are provided in (Table 1).

Table 1 –

Veteran Descriptive Characteristics and Use of Educational/Vocational Services

| Baseline Characteristics (n = 26) | |

|---|---|

| Mean veteran age | 42.2 |

| Mean caregiver age | 38.3 |

| Veteran sex, % | |

| Male | 100 |

| Female | 0 |

| Caregiver sex, % | |

| Male | 0 |

| Female | 100 |

| Veteran age, % | |

| 30 and under | 0 |

| >30 and ≤40 | 53.8 |

| >40 and ≤50 | 23.1 |

| >50 and ≤60 | 19.2 |

| >60 | 3.8 |

| Veteran race, % | |

| White/Caucasian | 63.5 |

| Black/African American | 9.6 |

| Asian | 0 |

| Native American/Pacific Islander | 1.9 |

| Mixed | 1.9 |

| Other | 11.5 |

| Prefer not to answer | 11.5 |

| Caregiver race, % | |

| White/Caucasian | 69.2 |

| Black/African American | 3.8 |

| Asian | 0 |

| Native American/Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Mixed | 3.8 |

| Other | 0 |

| Prefer not to answer | 15.4 |

| Veteran ethnicity, % | |

| Hispanic, Latino | 11.5 |

| Caregiver ethnicity, % | |

| Hispanic, Latina | 7.7 |

| Veteran/caregiver relationship, % | |

| Spouse | 84.6 |

| Parent/c hild | 7.7 |

| Significant other | 7.7 |

| PCAFC services revoked when we spoke to them, % | 30.8 |

| Present or past health conditions of veteran spontaneously disclosed by respondents | |

| PTSD | 46.2 |

| TBI | 38.5 |

| Chronic pain | 23.1 |

| Musculoskeletal injury/limb loss | 50.0 |

| Memory loss/problems (without explicit description of TBI) | 23.1 |

| Headaches | 11.5 |

| Vision/hearing | 11.5 |

| Substance use | 7.7 |

| Other mental health (mood disorder, bipolar, anxiety) | 38.5 |

| Respondents Who Recalled Veteran Using Vocational, Training, or Educational Services | % |

| Used supported employment at least once | 15.4 |

| Used VR&E at least once | 57.7 |

| Used Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits | 65.4 |

| Used at least two of the services | 42.3 |

Note. TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Theme 1: Health and Economic Life Goals Intersect

Veterans’ recovery needs encompass health and vocational/educational domains, but health system processes that align services to meet these needs are limited. Veterans described how their postmilitary life goals intersected health and economic domains. By “staying healthy” they could provide for their families or contribute to society. Conversely, participating in VBA vocational/educational services also helped achieve health-related goals. Participants identified several reasons for why their health improved after using vocational/educational services, including greater self-confidence, building new skills, identifying enjoyable hobbies, and increased socialization. For example, one veteran who pursued training in physical education reported that identifying a career that he valued reduced his alcohol use and improved his sense of self. Another veteran who used the GI Bill to pursue photography courses described how that experience reduced his PTSD symptoms: “For me it was therapeutic […] I believe that something like that will help a lot of Veterans too [that suffer] from PTSD.” (ID6).

However, respondents reported limited interaction between VHA clinical health care teams and VBA vocational/education counselors. One veteran talked about how there is a “disconnect between the VA health care side and the benefits side (i.e. VR&E, GI Bill)” (ID1357); he went on to explain that in his experience health care providers might be aware of a program, like the GI Bill, but they do not know how to apply for it.

Despite this sentiment, respondents offered a few examples of how VHA health care providers enabled them to use vocational/educational services, including providing documentation for academic accommodations; providing care (e.g., medication, referrals) to enable the veteran to participate in school; providing referrals to a specific vocational service; and encouraging the veteran to pursue these services.

“I told [medical doctor] I wanted to go to school and he wanted me to go to school as well. He thought it would be good for me […] the [mental health] counselor that I see is, she thought it was good for me to go to school, they encouraged me to look into stuff. She [mental health counselor] was going to recommend me for a social worker program because she thought that I would be good at that […] and they even wrote letters for me for testing accommodations.” (ID47)

However, a few veteran respondents described how their health care providers discouraged or inhibited them from using vocational/educational services by refusing to sign application paperwork for these services.

“I did mention to my providers that I was pursuing it. My psychiatrist expressed concern that pursuing any kind of educational prospects were going to be too stressful for me and that I shouldn’t do it. I didn’t get any other support from any medical providers after [getting that response from the psychiatrist] I didn’t even talk to them. There was no support at our local VA for the [VBA] programs.” (ID58)

Theme 2: Caregiver Tasks to Support Health and Vocational Service Engagement

While all caregivers were involved in the veteran’s health care, many also played some role in helping veterans to use vocational/educational services. We identified five types of caregiver support that respondents reported helped veterans engage in health and vocational/educational services: instrumental, coordination, advocacy, emotional, and informational (Wills, 1991). Three out of four of the common functions of support (Wills, 1991) align with the tasks we observed—emotional, instrumental, and informational support. We identified advocacy and coordination as additional key functions.

Instrumental Support

Instrumental support refers to concrete ways that individuals directly assist one another and was frequently discussed as a type of support that enabled veteran service use. Instrumental tasks for health care included providing transportation to appointments and managing medication. Instrumental tasks were also frequently cited to support use of vocational/education services; tasks encompassed registering the veteran for classes, helping the veteran to complete assignments, coordinating paperwork for VA benefits or school disability services, reviewing the veteran’s resume and job applications, caring for children, and handling household tasks. A few respondents alluded to ways that caregivers performed instrumental support tasks across both health and vocational/educational services by managing household calendars and tracking health care appointments and class schedules.

Coordination

Coordination involves managing multiple instrumental tasks and synthesizing and conveying information to various service providers. One caregiver described her coordinating role within health care:

“Informing [providers] of progress at home, how he’s doing mentally, how he’s doing physically. And then letting them know side effects or anything that [is] going on with medications that he’s taking.” (ID736)

Caregiver coordination tasks encompassed reaching out to VA providers, professors, and disability services to help streamline the process of applying to and attending school. While coordination tasks were less frequently cited for educational/vocational services, respondents described this type of support as key to veteran success in school. For example, one caregiver described the multitude of tasks that she undertook to ensure that the veteran ’s needs would be met so that he could be successful in an academic setting:

“I toured some of the schools with him and I would sit in on those conversations to make sure things weren’t being missed. I would help him get paperwork or applications filled out, information assembled to send into the school or the VA […] I would help him type up papers or I [would] contact the school and ask for additional deadlines because he was having a hard time meeting the deadlines. I sent in medical documentation for […] disability, for them to grant him that extra time to complete assignments and I would email his professors and send them all that information as well.” (ID411)

Advocacy

Advocacy involves speaking on behalf of another person to ensure that their needs are being met. Respondents described instances where caregivers provided vigilant oversight of the health care process to ensure that veterans got the services they needed. For instance, caregivers would speak to providers on behalf of the veteran to clarify next steps, request medicine refills, or insist that the veteran receives referrals to different specialists. In a few cases, caregivers sought assistance from high-level officials, including the medical director. Veterans expressed appreciation for these types of efforts:

“She understands how to advocate … she knows the right things to ask and the terminology that the healthcare folks use to be able to get the right answers […] she has to track changes and watch what’s going on with me and then translate that and sometimes has to tell medical professionals we need this consult. Sometimes she has to say look, we can’t waste time with you trying to figure [this] out in six months […] it’s going to be too late, so we’re going to do this instead.” (ID88)

Caregivers also described how they might articulate the veteran’s point of view to instructors and school counselors who may not be familiar with the impact of service-related disabilities on the veteran’s ability to organize information, concentrate and perform other tasks that are instrumental to academic success. While advocacy was also more commonly reported for health care services, stories about advocacy in academic settings showed how caregivers powerfully communicated the inherent challenges of acquired disabilities on the veteran’s academic performance. For example:

“I was able to help by going to the registrar’s office, going to the special services department, and ensuring that everything was handled, and the professors were aware that he isn’t a joke and he’s here, and he wants to be taken seriously, but it’s more than just the arm that’s missing. It’s the intellectual and emotional disabilities that affect these veterans more because it’s harder for us able bodies to recognize the difference.” (ID15)

Emotional Support

In general, caregivers expressed caring and empathetic attitudes toward the veteran, though the explicit role of social support in service engagement was less salient. Caregivers calmed veterans when they had difficulty managing their emotions during frustrating encounters with health care or school staff. Respondents also described how caregivers encouraged the veteran to seek services to “get their life back on track”; one caregiver said, “… he wanted to go for it [VR&E] and I was more than happy to see him do it. If that’s what he wanted to do, then I was all for it.” (ID152).

Informational Support

Several respondents described how caregivers provided advice about how to navigate the VA Health Care System and the process of attending college. For example, caregivers who had attended college helped to prepare the veteran for the experience:

“I’ve already had one undergrad degree. So I was more aware of what he was going to be experiencing to help him gear up for what he’s going in for.” (ID15)

Theme 3: Institutional Support for Caregivers to Support Service Engagement

Dyads described how institutional support for family caregivers helped veterans engage in VA health services and, in a more limited way, vocational/educational services. Respondents described how institutional support for caregivers provided by PCAFC was essential for improving veteran use of health care services; key elements included providing a point of contact in VA for families to address caregiver and veteran needs, providing financial assistance, and acknowledging the caregiver role.

Respondents reported that one of the most important elements of PCAFC was having a point of contact within the VA system for caregivers. Caregiver Support Coordinators (CSCs) linked caregivers to services for them, including caregiver skills workshops, disease education, respite care, and support groups. As a point of contact for caregivers, the CSCs provided families with a channel in the VA system through which the caregiver could be empowered to seek support for the veteran. For example, several respondents described instances when they encountered challenges with VHA, such as trying to access follow-up care, and caregivers reached out to their assigned CSC who helped them resolve the issue. CSCs also helped to facilitate veteran care by circumventing or coordinating processes that veterans and caregivers found difficult to navigate; examples included scheduling health care appointments with specialists, getting prescriptions filled, and acquiring medical equipment. One caregiver said:

“[The CSC] is probably the biggest godsend I’ve ever had. She [CSC] knows all the programs […] Right now, we’re working on a service dog. We’re working on the application to get a walk-in shower installed. And she also gave us a program that we could do to get help with building…we have to build a new house because [veteran] can’t get into our house very well. If we have a problem, she knows the services.” (ID277)

The stipend allowed caregivers to devote more time to supporting the veteran and his health care and less time working for an income. One veteran described how the financial assistance aided his recovery:

“I forget a lot of stuff, I don’t do a lot of stuff to completion because of my medical conditions, so by her being able to stay home more through the caregiver program and not having to work […] helps me accomplish a lot of my goals and our goals as a family. […] Before, she was working I would miss a lot of my appointments. I would forget most of my appointments. I would forget to take medicines, or I’d over-medicate myself. My lack of being able to work was really affecting our financials because she couldn’t work full-time, but I couldn’t work, so it was bad.” (ID102)

Respondents also talked about the benefits of having the designation of “caregiver.” Specifically, respondents perceived that participating in PCAFC formalized the caregivers’ role and increased the caregivers’ legitimacy in the eyes of health care providers. For example, respondents said that caregivers were able to participate in more aspects of the veteran’s care because they were enrolled in PCAFC: “In a lot of ways it’s given her more legitimacy to make my appointments with the providers. The providers take her more seriously.” (ID58)

Examples of how PCAFC helped veterans to engage in vocational/educational services were less common. However, several veterans reportedly learned about vocational/ educational services from PCAFC staff or were encouraged by PCAFC staff to pursue these services, “One of the nurses there […] was saying well you could do something for yourself, and you can go to school.” (ID67). Respondents also acknowledged the importance of the stipend for freeing up the caregivers’ time. One veteran who pursued postsecondary education through the Post-9/11 GI Bill reported that his caregiver met with his professors every semester. Another veteran who used supported employment said that his caregiver helped him manage his health so that he could get to a place where he could find a job:

“I wouldn’t be anywhere near where I am now if she didn’t have the ability to take that time and work less hours and spend that time with me at my appointments, so that way she can make sure that I do everything they tell me […] if I hadn’t made that progress and gotten to where I am now, there’s no way that I’d be contemplating school and employment and kids. I’d be years behind where I am right now if we didn’t have a caregiver support program giving us that time. That five, ten hours a week really adds up and makes a big difference.” (ID647)

Discussion

Conceptual Map

We used the findings (Figure 1) to depict for the first time how social support from caregivers helps patients with disabilities to engage in services. This conceptual map is not meant to delineate causality; additional research is needed to confirm the validity of the constructs and how the model applies in populations with different characteristics.

Figure 1 –

Conceptual map: caregiver support for promoting veteran engagement in and across health and vocational/educational services.

Consistent with previous research (Fischer et al., 2015; Sayer et al., 2010), recovery goals reported by our Post-9/11 veteran participants cut across health and vocational/educational domains. However, while the VA system (i.e., VHA and VBA) offers health and vocational/educational services, there are few health system processes that align these services to comprehensively address veteran recovery needs (represented by dashed line).

While caregivers play a fundamental role in helping veterans engage in VA services, particularly health care, their role in vocational/educational services is more limited. Types of social support tasks that caregivers undertake are similar across service domains. For example, respondents cited coordination and advocacy as essential caregiver tasks for health services, yet these tasks were rarely mentioned in discussions about vocational/ educational services. The limited role that caregivers play in vocational/education services is surprising; veterans often do much of the groundwork to coordinate with individuals across service domains, including health providers, vocational/educational service counselors, work colleagues, and school staff, even though coordination can be challenging for veterans with functional limitations (Kukla, McGuire, & Salyers, 2016). Additionally, participating in these services requires that veterans interact with civilians who may lack insight on how combat exposure can impact them physically and mentally (Steele, Salcedo, & Coley, 2011); thus, for veterans to succeed in these settings, advocacy is essential. Caregivers perform advocacy and coordination functions for health care, and with additional knowledge caregiver support could be extended to educational/vocational services.

We propose that VA institutional support for caregivers has the potential to increase engagement in services by providing resources and support to the caregiver and potentially strengthening system-level processes of service integration. Our findings confirm previous research findings that VA institutional support for caregivers increases veteran engagement in health care (Van Houtven et al., 2017). However, only a few dyads reported that PCAFC staff encouraged them or gave them information to navigate vocational/educational services. Participants viewed PCAFC to be more influential for health care than educational/vocational services likely because PCAFC is a VHA program that provides resources related to veteran physical and mental health care.

Limitations

Our methods have several limitations. First, some individuals had not recently used the vocational/educational services that may have affected the extent to which they could accurately recall their experiences. Moreover, identifying veterans who had used supported employment was particularly challenging; contact information was outdated and many veterans did not recall using this service. Second, as both the veteran and caregiver had to participate in the interview, our sample may not have included veterans whose caregivers were less engaged or supportive. Also, we were unable to identify family caregivers who never applied to PCAFC. Our sample is not generalizable to all disabled U.S. veterans who use services within an integrated health system; despite our efforts to recruit a diverse sample, all of the veteran participants were male and the caregiver participants were female. Further, veteran participants were all over 30 years old. The findings and conclusions are also only pertinent to veterans who desire caregiver support and whose caregivers have the capacity to provide this support; if these conditions are not met, other supports may be needed to help veterans engage in nonmedical services. Lastly, despite the benefits of joint interviews for eliciting information about complex interactions (Sayer, Spoont, Nelson, Clothier, & Murdoch, 2008), this type of interview did not allow us to capture information from participants that they did not wish to disclose in front of their partner.

Considerations

Several veterans reported improvements in health as a result of their participation in vocational/educational services. This finding suggests that including these services as part of overall patient treatment could yield important health benefits and this is consistent with existing literature (Bond & Drake, 2014; Kukla, Bond, & Xie, 2012). While caregivers can assist veterans to meet their complex cross-cutting needs by helping them to connect with the right combination of health and vocational/educational services, in practice this occurs infrequently. Given caregivers’ holistic knowledge of the veteran’s experiences, their involvement in veteran health services positions them to communicate with clinical teams about the veteran’s other goals and needs, such as job or education assistance. Caregivers can also relay information about the veteran’s progress and coordinate with clinical teams for documentation and supplies needed to enhance the veteran’s success in vocational/educational services.

Institutional support provided to caregivers to help veterans engage in health care can serve as a model for extending caregiver support into other settings where the focus is on work and education. However, while PCAFC has an orientation toward recovery and psychosocial rehabilitation, there is an opportunity to strengthen how this approach translates into practice by systematically equipping caregivers with the tools and information they need to navigate within and across VA health and vocational/educational services. To accomplish this, PCAFC nursing and social worker staff could work with the family to develop a comprehensive plan to document and address the veterans’ needs and goals (Simmons, Drake, Gaudet, & Snyderman, 2016). Some caregivers may experience high levels of fatigue and burn-out; these caregivers may need additional support from the CSCs before they are ready to help implement a comprehensive plan to address health and nonhealth needs; in these cases, caregiver needs could be incorporated into the comprehensive plan. Additionally, PCAFC staff could provide caregivers with a comprehensive list and description of health, vocational/educational, and other services across VA and provide recommendations and referrals as appropriate. PCAFC can also create systematic protocols to help families develop these plans. Further, PCAFC staff could routinely cultivate relationships with vocational/ education counselors and coordinators to facilitate connections between caregivers and these programs.

Developing relationships between caregiver support programs, health care providers, and health/nonhealth divisions might also enhance perceptions of caregivers; several respondents reported that their PCAFC affiliation bestowed credibility and formalized their role as part of the health care team. This is important because currently there is little precedent or expectation for caregivers to help veterans navigate vocational/educational services. Caregivers initiated interfacing with health and vocational/educational services when the veteran had difficulty coordinating services himself or when there was no other coordination support available through VA. Therefore, PCAFC has an opportunity to more broadly influence VA’s cultural perspective about the role that caregivers can play across health and vocational/educational services (Sperber et al., 2019).

We offer a few cautions related to caregiver involvement in health and vocational/educational service integration. First, in some cases veterans may limit communication between health and vocational/educational services. Veterans who are working would compensation benefits or other support (i.e., VA health care insurance, the PCAFC stipend) if VA providers or VBA benefits counselors perceive that they are no longer impaired by their disabilities (Wyse, Pogoda, Mastarone, Gilbert, & Carlson, 2018). Another challenge is that some veterans may not desire caregiver involvement in these services (Fischer et al., 2015). Our study participants did not express this sentiment, but in such cases, veterans must determine the extent to which others are involved in helping veterans meet their recovery goals. Finally, a few respondents described how some providers were not supportive of veterans seeking vocational training and education. If this provider-level attitude is pervasive across VA, it could inhibit system level efforts to encourage caregivers to help coordinate veteran care across health and nonhealth services. While our recommendations have focused on the role of nurses and social workers as point-persons for caregivers to help activate change, provider attitudes must also be addressed through change efforts (Sperber et al., 2019).

Implications

We offer considerations for how U.S. and non-U.S. health systems can advance institutional policy efforts that leverage social support from family caregivers to align existing, but siloed, health and vocational/educational services. By aligning health and nonhealth services, health systems can better meet the wide-ranging needs of persons with disabilities.

VA offers a robust program of services and supports for family caregivers. Further, VA is an integrated health system with similarities to non-U.S. health systems. As such, VA is a laboratory for global health system innovations in caregiver support; lessons learned from these efforts can be translated into other U.S. and non-U.S. health systems to bolster support for caregivers of adults with complex illnesses due to disability or injury. Our results demonstrate that institutional support for caregivers could have a strong influence on aligning services with patient’s needs. Specifically, by adopting caregiver support policies that have been implemented in VA, other health systems can also leverage social support from family caregivers to address the intertwined health, educational, and vocational needs of persons with complex, chronic conditions. A key feature of this institutional support is staffing a point-person for family caregivers as part of an interdisciplinary team. Working together with the caregiver and patient, such coordination can lead to a comprehensive Whole Health (Gaudet & Kligler, 2019) plan of treatment and services that acknowledges and considers the patient’s cross-cutting needs. Nurses and social workers are well-placed to serve as a system-level point-person for family caregivers because professional values and job roles match the type of support that family caregivers require. A primary component of most nursing and social work practice involves system-level efforts to reduce health risks; this focus is strongly aligned with the construct of Whole Health, which acknowledges that health depends on multiple inputs, including meaningful employment and strong social relationships (Zenzano et al., 2011). Further, across clinical contexts nurses and social workers routinely provide support to and educate family caregivers (Grant & Ferrell, 2012; Zenzano et al., 2011).

Conclusions

While service delivery across divisions is siloed, veterans identified interdependencies in their lives between health and vocational/educational goals. Caregivers are an available social support with an intimate knowledge of the patient’s cross-cutting goals and needs. Caregivers have the potential to work with health care teams and nonhealth service counselors to coordinate the delivery of the right services at the right time to address patients’ complex needs and help them to achieve their recovery goals. If health systems develop and implement well-crafted policies to strengthen support for family caregivers across health and nonhealth services, there is an opportunity to meaningfully improve the health and well-being of persons with acquired disabilities. Future studies in more diverse samples are needed to validate the constructs and relationships identified in the conceptual map. Specifically, these studies should capture information about caregiver and care recipient function to better understand how these factors might influence a caregiver’s ability to provide the observed functions. Such studies would help to refine the model and adapt it for families with varying health and stress-related needs.

Acknowledgments

Support for this publication was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through the Systems for Action National Coordinating Center, ID 74941. Additional support comes from the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT; CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Caregiver Support Program, and Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (PEC 14-272). We would like to acknowledge the efforts of Karen Stechuchak who compiled the recruitment list and Emilie Travis who recruited all participants.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Durham VA Institutional Review Board.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2019.08.006.

REFERENCES

- Abraham KM, Ganoczy D, Yosef M, Resnick SG, & Zivin K (2014). Receipt of employment services among Veterans Health Administration users with psychiatric diagnoses. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(3), 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Administration VH. (2016). Whole health for life: Components of proactive health and well-being. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; Available from: https://www.va.gov/PATIENTCENTEREDCARE/resources/components-of-proactive-health.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, & Drake RE (2014). Making the case for IPS supported employment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KF, Pogoda TK, Gilbert TA, Resnick SG, Twamley EW, O’Neil ME, & Sayer NA (2018). Supported employment for veterans with traumatic brain injury: Patient perspectives. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(2S) S4–S13.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Kyriakides TC, Suris AM, Ottomanelli LA, Mueller L, Parker PE, & …VA CSP #589 Veterans Individual Placement and Support Toward Advancing Recovery Investigators. (2018). Effect of evidence-based supported employment vs transitional work on achieving steady work among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Kaler ME, Schult T, Polusny MA, & Arbisi PA (2011). Mental health diagnosis and occupational functioning in National Guard/Reserve veterans returning from Iraq. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 48(10), 1159–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EP, Sherman MD, McSweeney JC, Pyne JM, Owen RR, & Dixon LB (2015). Perspectives of family and veterans on family programs to support reintegration of returning veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services, 12(3), 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet T, & Kligler B (2019). Whole health in the whole system of the veterans administration: How will we know we have reached this future state? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(S1), S7–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, & Ferrell B (2012). Nursing role implications for family caregiving. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 28(4), 279–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, & Namey EE (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications, Inc.. [Google Scholar]

- Holder KA (2018). Veterans who have served since 9/11 are more diverse.

- Kukla M, Bond GR, & Xie H (2012). A prospective investigation of work and nonvocational outcomes in adults with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(3), 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukla M, McGuire AB, & Salyers MP (2016). Barriers and facilitators related to work success for veterans in supported employment: A nationwide provider survey. Psychiatric Services, 67(4), 412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukla M, Rattray NA, & Salyers MP (2015). Mixed methods study examining work reintegration experiences from perspectives of veterans with mental health disorders. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 52(4), 477–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meterko M, Baker E, Stolzmann KL, Hendricks AM, Cicerone KD, & Lew HL (2012). Psychometric assessment of the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory-22: The structure of persistent postconcussive symptoms following deployment-related mild traumatic brain injury among veterans. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 27(1), 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogoda TK, Levy CE, Helmick K, & Pugh MJ (2017). Health services and rehabilitation for active duty service members and veterans with mild TBI. Brain Injury, 31(9), 1220–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak L, & Green J (2016). Using joint interviews to add analytic value. Qualitative Health Research, 26(12), 1638–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik L, Borgia M, Ni P, Pirraglia PA, & Jette A (2012). Reliability, validity and administrative burden of the community reintegration of injured service members computer adaptive test (CRIS-CAT). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12,145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik LJ, & Allen SM (2007). Using International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health to understand challenges in community reintegration of injured veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 44(7), 991–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, & Murdoch M (2010). Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatric Services, 61(6), 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Spoont M, Nelson DB, Clothier B, & Murdoch M (2008). Changes in psychiatric status and service use associated with continued compensation seeking after claim determinations for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(1), 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons LA, Drake CD, Gaudet TW, & Snyderman R (2016). Personalized health planning in primary care settings. Federal Practitioner, 33(1), 27–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber NR, Boucher NA, Delgado R, Shepherd-Banigan ME, McKenna K, Moore M, & …Van Houtven CH (2019). Including family caregivers in seriously Ill veterans’ care: A mixed-methods study. Health Affairs, 38(6), 957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele JL, Salcedo N, & Coley J (2011). Service members in school: Military veterans’ experiences using the Post-9/11 GI Bill and pursuing postsecondary education. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Baker DG, Norman SB, Pittman JO, Lohr JB, & Resnick SG (2013). Veterans Health Administration vocational services for Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom veterans with mental health conditions. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 50(5), 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Smith VA, Stechuchak KM, Shep- herd-Banigan M, Hastings SN, Maciejewski ML, & …Oddone EZ (2019). Comprehensive support for family caregivers: Impact on veteran health care utilization and costs. Medical Care Research and Review, 76(1), 89–114 1077558717697015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, & Weinberger M (2011). An organizing framework for informal caregiver interventions: Detailing caregiving activities and caregiver and care recipient outcomes to optimize evaluation efforts. BMC Geriatrics, 11, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA (1985). Supportive functions of interpersonal relationships In Cohen SI, & Syme SL (Eds.), Social support and health (pp. 61–82). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA (1991). Social support and interpersonal relationships In Clark MS (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology: Prosocial behavior 12Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wyse JJ, Pogoda TK, Mastarone GL, Gilbert T, & Carlson KF (2018). Employment and vocational rehabilitation experiences among veterans with polytrauma/traumatic brain injury history. Psychological Services PMID is: 30265073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenzano T, Allan JD, Bigley MB, Bushardt RL, Garr DR, Johnson K, & …Stanley JM (2011). The roles of healthcare professionals in implementing clinical prevention and population health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(2), 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]