Abstract

Objective:

Road traffic crashes (RTCs) are common amongst motorcyclists in Kigali, Rwanda. The Service d’Aide Medicale Urgente (SAMU), a prehospital ambulance service, responds to many of these crashes. We aimed to describe motorcycle related RTCs managed by SAMU.

Methods:

SAMU clinical data including demographic information, injury characteristics, and management details were analyzed descriptively for all motorcycle crashes occurring between December 2012 to July 2016.

Results:

There were 2,912 motorcycle related RTCs over the study period representing 26% of all patients managed by SAMU. The incidence of motorcycle crashes in Kigali was 258 crashes per 100,000 people over the 3.5-year study period. The average age was 30 years and 80% were males. The most common injuries were to the lower extremity (n=958, 33%), head (n=878, 30%), or upper extremity (n=453,16%). Injuries often resulted in fractures of extremities (n=740, 25%) and external hemorrhage anywhere in the body (unspecified region) (n=660, 23%), yet few were severe based on the Kampala Trauma Score (n=23, 2%) and Glasgow Coma Scale (n=42, 1.5%). The most common interventions were provision of Diclofenac (n=1526, 52.5%), peripheral IV access (n=1217, 42%), and administration of IV fluids (n=1048, 36%).

Conclusion:

Motorcycle related RTCs represent a large burden of disease for patients treated by SAMU in Kigali, Rwanda. Young men are most at risk of injury which imposes a financial strain to society. While injuries occurred frequently, critical trauma cases from motorcycle crashes were uncommon. This may be a result of several initiatives in Rwanda to improve road safety.

Keywords: Motorcycle, Africa, Prehospital, Emergency Medicine, Road Users

Introduction:

Road traffic crashes (RTCs) are a global problem. Each year they cause over 1.25 million deaths and an additional 35 million non-fatal injuries.[1] This has made RTCs the 8th leading cause of death globally and the number one cause of death in 15-to 29-year olds.[1] Worldwide, deaths due to RTCs rose 46% between 1990 and 2013.[2] Unfortunately, this rise is expected to continue as there is estimated to be a 40% increase in global deaths due to RTCs over the next few years. In 2030, it is estimated that RTC death will reach 1.9 million per year.[3]

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are the most susceptible. Despite having only 54% of the world’s vehicles, LMICs have 90% of deaths related to RTCs.[4] This is in part due to the emergence of the use of motorcycles as a major means of intra and inter-city transportation in LMICs.[5–7] This emergence has corresponded with a doubling in worldwide deaths related to two wheeled vehicles.[8] The risk of dying from a motorcycle crash is 20 times higher than other motor vehicles.[9] These findings have led the UN to emphasize road safety in the Sustainable Development Goals aiming of cutting road traffic deaths in half by 2020 (SDG 3.6).[10]

In Rwanda, as in many LMICs, the increase in motorcycle use has led to a rise in RTCs.[11] There are more two and three wheeled motor vehicles than cars and, according to the Rwandan National Traffic Police, they are the most frequently involved vehicles in RTCs.[12–14] There are nearly 55,000 motorcycles in Rwanda making them the most common mode of transport. Their popularity is due to their affordability and capacity for delivering riders from door to door rapidly.[15–16] Hospital data shows that the majority of patients involved in motorcycle RTCs are male, and the most common injuries were to the extremities.[17] Motorcycles were implicated in 73% of all traffic injuries (n=900) in 2011 at the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK), up from 41% reported in 2004.[18–19] However, little information exists on the characterization of injuries or management in the prehospital setting.

Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente (SAMU) is a division of the Rwandan Ministry of Health established in 2007 to provide prehospital emergency medical services. All patients treated by SAMU since 2012 have been recorded in a prehospital electronic database. The purpose of this study is to describe this database with regards to the epidemiology of motorcycle crashes in Kigali, Rwanda and the prehospital care provided by SAMU.

Methods:

Study Context and Setting

SAMU is the only emergency medical service in Rwanda. They utilize nurses and nurse anesthetists to deliver emergency prehospital care and transportation in the capital city of Kigali and surrounding areas. Caller information is received and assessed by trained professionals through a toll-free public 912 communication center. Ambulances are dispatched depending on patient need. Healthcare professionals, trained bedside nurses and anesthetists, perform triage, provide stabilizing interventions, and make decisions regarding transportation. SAMU has previously been described in detail.[20]

Data Collection and Variables

This study retrospectively analyzed a database containing all patients treated by SAMU for motorcycle related RTCs between December 2012 and May 2016. This time period represents the most complete and accurate information available. SAMU collects clinical data using paper run sheets for each patient encounter that includes patient demographics, history, encounter information, physical exam findings, and vital signs. They electronically enter this data into a secure online REDCAP database (Vanderbilt University; Nashville, Tennessee, USA) created in collaboration with Brigham Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Service d’Aide Medicale Urgente as previously described. [13]

Demographics, vital signs, injury mechanism, type of injury, and treatment were analyzed for this study. Vital signs included oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate. Hypoxia was defined as oxygen saturation less than 90%. Tachypnea was defined as a respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths per minute. Hypotension was defined as systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg. Tachycardia was defined as heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute. RTCs were defined as any incident involving a road vehicle including automobile, motorcycle, or bicycle. Motorcycle related RTCs were identified as any crash involving a motorized two-wheeled vehicle. The SAMU team determined and recorded anatomic location of injury based on their clinical assessment and care during transportation. Additionally, SAMU utilizes a triage system which categorizes each case as “absolute”, “relative”, or “no urgency” based on mechanism, clinical presentation and vital signs. Transport destinations included referral hospitals (highest level of care), district hospitals (mid-level care), and health centers (primary care). Primary transportation referred to movement of patients to their initial health facility while secondary transportation referred to transfer of patients between health facilities.

Injuries were further characterized by Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Kampala Trauma Score (KTS), Shock Index (SI), mechanism of trauma, anatomical location, and urgency. The KTS was used to describe injury severity and calculated using respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, age, neurologic status, and number of significant injuries. KTS scores of <6, 7–8, and 9–10 were classified as a clinical status of severe, moderate, and mild in line with the modified KTS scoring system. SI was calculated using heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure. SI greater than 0.9 was considered severe. The pediatric specific shock index was used for patients between the ages of 4 and 16. Patients under 4 years old were excluded due to lack of validated metrics.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Only patients with recorded values for a given variable were included in analysis.

Ethical Consideration

The project is part of a formal Memorandum of Understanding between Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and the Ministry of Health of Rwanda to facilitate trauma and emergency systems development in Rwanda. Ethical approval has been obtained from the Rwandan Ministry of Health as well as the Virginia Commonwealth University, IRB number: HM20011011. The REDCap registry has received IRB approval from Harvard University, VCU, and the Rwandan Ministry of Health.

Results:

Demographics

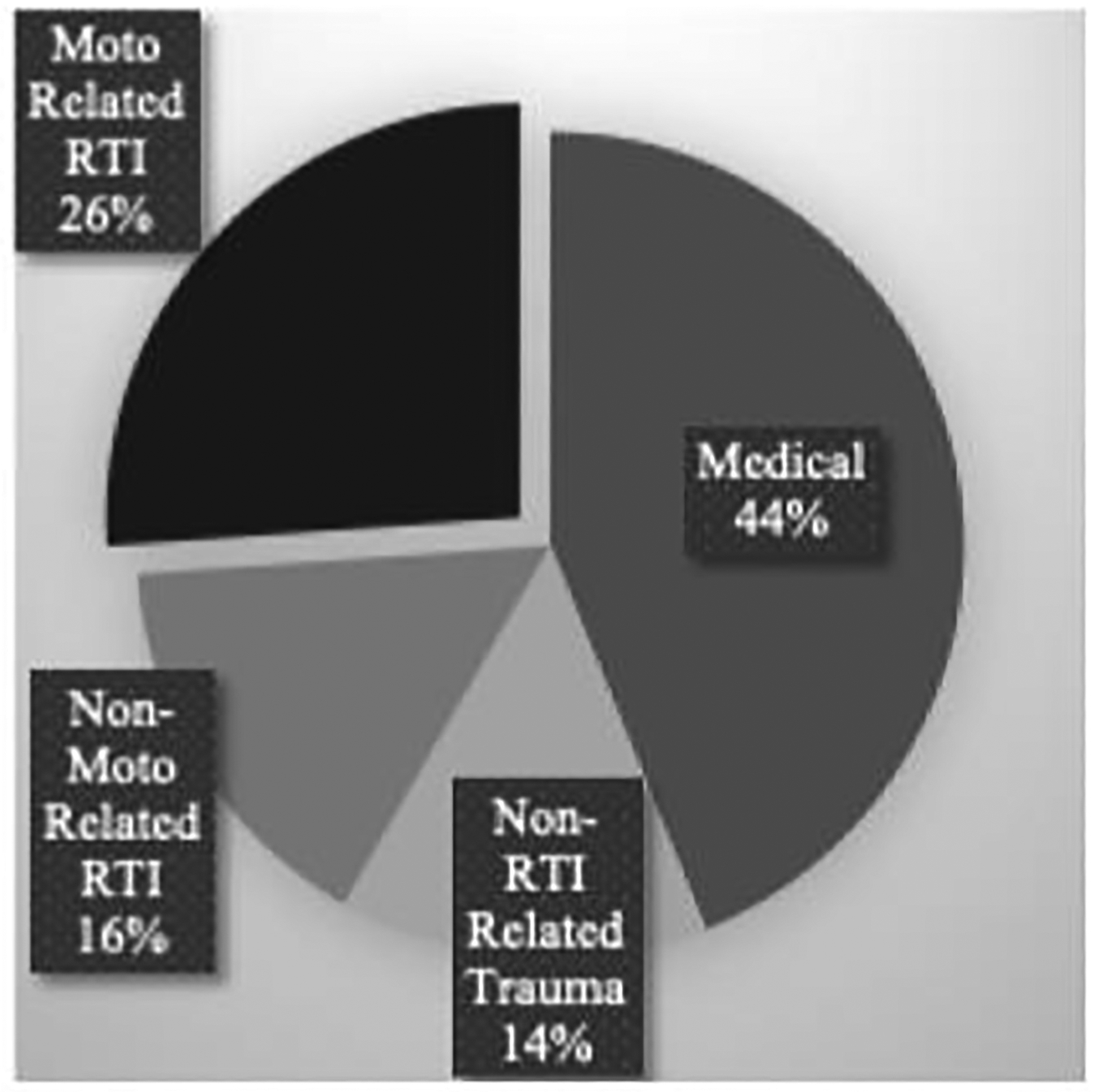

SAMU responded to a total of 11,161 patients from December 2012 through June 2016, of which 4,649 (42%) involved RTCs (Figure 1). Motorcycles were involved in 2,912 (63%) RTCs. The mean age was 30 (10) and the median age was 29 (24, 34). There were 2,331 (80%) males. The most common RTCs involving motorcycles were those between a motorcycle and a car (n=1,183, 41%) followed by those between a motorcycle and a pedestrian (n=841, 29%), motorcycle-motorcycle (n=391, 13%), single motorcycle (n=367, 13%), and motorcycle-bicycle (n=130, 4%). The incidence of motorcycle crashes in Kigali seen by SAMU was 258 crashes per 100,000 people during the 3.5-year study period.

Figure 1.

Etiology of SAMU Call.

Presentation

Patients sustained a number of injuries due to motorcycle related RTCs (n=2912). The majority of injured patients were the driver of the motorcycle (n=725, 46.5%), however, the patient’s role was only recorded for 55% of patients. Lower extremity trauma was most common (n=958, 33%) followed by traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) (n=878, 30%) and upper extremity trauma (n=453, 15.5%). 29 (3.5%) patients with TBIs had a GCS less than 8 while 651 (76%) had a GCS of 15. Drivers and passengers of the motorcycle most commonly sustained lower limb trauma while pedestrians most often suffered head trauma. The smell of alcohol was noted on 119 (16.5%) motorcycle drivers involved in an RTC (table 1). Motorcycle related RTCs resulted in 740 (25%) fractures of which 390 (56%) were closed and 306 (44%) were open. Other common injuries included external hemorrhage (n=660, 23%) and bruising (n=647, 22%). There were 601 (41%) patients with one or more severe injuries based on clinical presentation. Most patients were assigned a triage status of relative urgency (n=2037, 71%) and 260 (9%) were assigned a triage status of absolute urgency.

Table 1.

Injury Patterns and Severity Based on Patient’s Role n Motorcycle Related RTC.

| Patient’s Role in RTC | Number of Patients | Most Common Injury | Severity, |

|---|---|---|---|

| Driver | 725 (46.5%) | Lower Limb Trauma (207, 28.5%) | 53 (7.5%) |

| Passenger | 459 (29.5%) | Lower Limb Trauma (125, 27%) | 26 (5.5%) |

| Pedestrian | 311 (20%) | Head Trauma (92, 29.5%) | 18 (6.0%) |

| Missing = 1,358 (46.5%) |

Note: Missing is the patient’s role in the RTC.

SAMU recorded several vital signs upon arrival at each patient encounter. Tachycardia (n=161, 7%) and tachypnea (n=137, 5%) were the most common physiologic derangements, while hypoxia (n=83, 3%) and hypotension (n=25, 1%) were less common. SAMU responders noted that 42 (1.5%) patients had severe traumatic brain injury (GCS ≤ 8). Kampala Trauma Score (KTS) and Shock Index (SI) were also calculated to further assess severity of injury. Using these metrics, it was found that 23 (2%) patients had a severe KTS (< 6) and 100 (3.5%) had a severe SI.

Treatment and Transportation

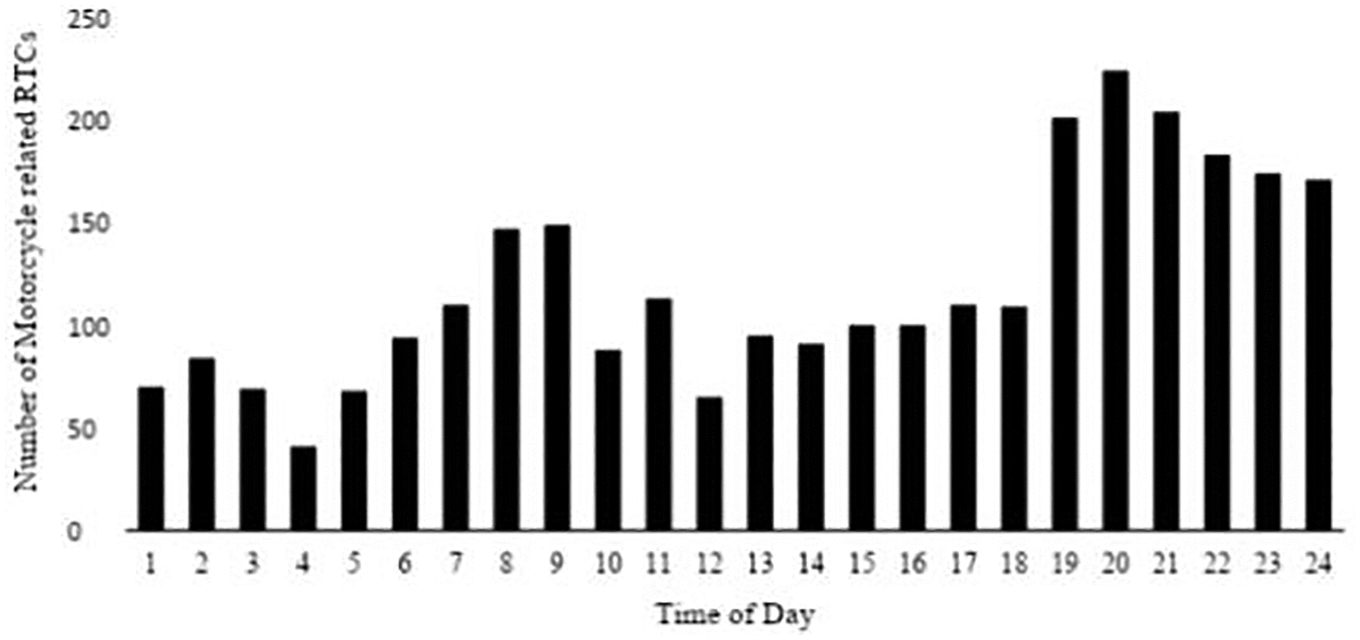

SAMU teams performed many interventions in the field and made decisions regarding transportation. Ambulances traveled a median of 12 km (8–22 km) to reach a healthcare facility. Patients were most commonly involved in motorcycle related RTCs between 19:00 and 21:00 (Graph 1). Most patients involved in a motorcycle related RTCs (n=2805, 97%) underwent primary transportation. Many patients were transported to the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK, n=1,080, 42.5%) or Kibagabaga District Hospital (n=770, 30%). Patients with more acute presentations based on urgency status, lower GCS, and injuries classified as severe were more likely to be transported to CHUK which is the major trauma center in the country (p<0.01).There were 337 (13%) patients that required on-site care without the need for transfer to a healthcare facility. These patients had less acute presentations based on urgency status, GCS, and number of severe injuries (p<0.01). The most common interventions for these patients was the application of wound dressings (n=222, 66%) and the provision of pain medications (n=146, 43%). Additionally, four (<1%) patients were found dead upon SAMU arrival and four (<1%) died during transportation to the hospital. SAMU is not contacted if a patient is found dead by a bystander.

SAMU performed interventions for 1,361 (47%) patients involved in a motorcycle related RTC. The most common interventions were establishing peripheral IV access (n=1,217, 89%), administering fluids (n=1,048, 77%), and external hemorrhage control (n=1,036, 76%). They immobilized 708 (52%) patients with cervical collars and 673 (49%) patients with splints. The most commonly administered medications were analgesics, including nonsteroidal analgesic drugs and opioids.

Discussion:

This study describes motorcycle related RTCs treated by SAMU in the prehospital setting of Kigali, Rwanda. Our results show that young men were commonly involved in motorcycle crashes and often sustained lower extremity and head injuries. While few injuries were severe, SAMU did respond to a high number of motorcycle crashes and recorded an incidence of 258 crashes per 100,000 people in Kigali over the 3.5-year study period. The most common interventions performed were the provision of medications, establishment of peripheral IV access, and administration of fluids.

We report a high incidence of motorcycle crashes in Kigali, Rwanda. This incidence is higher than reports from neighboring countries. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Kampala, Uganda report incidences of 24 and 190 motorcycle crashes per 100,000 people respectively. This may be due to Rwanda being one of the densest countries in Africa with a rapidly urbanizing population. This concentrated population could be forced to use their motorcycles at lower speeds due to significant crowding. This could decrease the severity of motorcycle collisions. The population is increasingly turning to motorcycle transportation as a cheap and convenient mode of transportation. Despite the high incidence, most injuries were mild or moderate. This could reflect the government of Rwanda’s dedication towards improving road safety but could be due to significant crowding on the densely populated streets of Rwanda forcing more low-speed collisions. Additionally, Rwanda has enacted several laws regarding road safety such as mandating helmet use for all motorcycle riders. While this has helped reduce head injuries the impact on location, injury patterns and timing of motorcycle crashes has yet to be seen.

Our findings support global trends showing men are more likely to be involved in RTCs than women, especially in LMICs. Three quarters of road traffic deaths globally occur among men under 25 years of age.[1] Men are traditionally breadwinners of their families and must often travel for work. Additionally, a common profession for men is motorcycle taxi driver. Almost all motorcycle taxi drivers in Kigali are men, as only four women were registered to drive motorcycles in 2012. Between 2011 and 2014 there was a 30-fold higher number of motorcycle licenses issued to men compared to women in Rwanda. Motorcycle related RTCs are affecting a large number of young working men which can prevent them from earning a living during their recovery and compounds the substantial economic burden of injury. Although no economic estimates exist specifically examining motorcycle crashes, the annual costs of all RTCs in LMICs are estimated to be between USD$65–100 billion. Between 2015 and 2030 RTCs are predicted to cost Rwanda USD $347 million and cause a per capita loss of USD $25. Injury prevention through road safety and delivery of high-quality prehospital care for this population can improve health and economic productivity in the country. The findings of this study have been shared with the Rwandan Ministry of Health, the Rwandan National Police, as well as a local non-profit, Healthy People Rwanda, which focuses on road safety education and injury prevention. A collaborative group has been established to help create a national driver safety course for motorcyclists and a public health campaign to raise awareness about road safety.

We report similar injury characteristics as previous studies. RTCs often result in head and lower extremity injuries in LMICs. Studies from other sub-Saharan African countries including Benin, Uganda and Sierra Leone report 38–41% incidence of traumatic brain injury in motorcycle crashes. Our study found that 30% of motorcycle related RTCs managed by SAMU in Kigali had traumatic brain injury. Furthermore, the head injuries observed in our patient population were typically mild or moderate based on GCS and KTS. Lower rates and less severe head injuries may be due to mandatory helmet laws and strict limitations on the number of passengers on a motorcycle at one time. Fractures were also common among patients treated by SAMU. This is similar to previous studies showing high rates of fractures amongst RTC victims.[20] Prehospital care is essential for fracture management. Early recognition and reduction can control hemorrhage, reduce pain, and lower rates of complications such as amputation. Rapid stabilization of fractures is the recommended standard of care; however this cannot be accomplished without timely access to hospital care through a well-functioning prehospital ambulance service.

SAMU provided care at the scene to 1,361 (47%) patients involved in motorcycle related RTCs and was able to treat 337 (13%) motorcycle related RTC patients at the site of the crash without having to transport to a healthcare facility. In addition to providing lifesaving interventions and reducing injury complications, prehospital services have been shown to decrease emergency department utilization. This is an essential resource in LMICs where overcrowding in the emergency rooms may stress resource limitations. SAMU’s ability to care for minor injuries may lead to fewer emergency department visits.

While the greatest benefit of prehospital trauma care can be achieved through the consistent application of vital interventions, the essential components of that care are not well established in LMIC settings. Based on our study early identification of injuries, stabilization of fractures, and acute management of external hemorrhage should be fundamental principles of prehospital care in LMICs. Common interventions performed included provision of pain-relieving medication, establishment of peripheral IV access, and administration of fluids. We have developed and implemented a context appropriate prehospital trauma care course for SAMU in a train-the-trainers manner as well as field guidelines for managing such injuries in order to ensure the delivery of high-quality prehospital care in Kigali, Rwanda. The results of these programs will be published shortly.

The World Health Organization has recommended the implementation of emergency medical systems to improve injury outcomes in LMICs. In response to this finding, the Rwandan Ministry of Health created SAMU in 2007 and it remains one of only a few prehospital emergency medical services operating in LMICs. SAMU has overcome many barriers faced by other organizations by establishing a centrally coordinated prehospital care system. They provide emergency transportation and injury management in the prehospital setting which is essential to optimizing clinical outcomes. Due to limited data prior to the formation of SAMU, it is difficult to measure the extent of their impact on outcomes and further studies are needed. SAMU works in a resource limited environment with a heavy burden of motorcycle related RTCs. Financial constraints impede progress and limit expansion. More resources and training are needed to support SAMU’s efforts to reduce the impact of injury. SAMU is working in partnership with the Ministry of Health to optimize prehospital services. Data from this study as well as other internal reviews is being used to develop strategies to improve supply chains and create preventative campaigns.

There are several limitations in this study. The true incidence of motorcycle related RTCs is likely higher than we report as only patients in motorcycle crashes managed by SAMU are included in this study. Thus, we did not include crashes that did not require SAMU or patients that accessed the hospital via private means. Additionally, there is currently no trauma registry used throughout Rwanda or a linkage between hospital records and prehospital services. We therefore do not report on patient care at healthcare facilities or ultimate outcomes. Future studies are needed connecting prehospital data with police and hospital records. Furthermore, diagnoses made in the prehospital setting may differ from those provided in the hospital. Lastly, this data was manually entered into patient run sheets and digitized into the Redcap database without major data auditing which may have resulted in errors or omissions.

Motorcycle related RTCs are responsible for a large burden of injury in Kigali, Rwanda. Patients are often young men sustaining moderately severe head and lower extremity injuries. SAMU provides much needed prehospital care and transportation for these patients as an integral part of the Rwandan healthcare system. Investment in injury prevention, educational initiatives, and prehospital care are essential for the country to continue its efforts to improve road safety.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Motorcycle Related RTCs by Time of Day.

Acknowledgements:

Pamela Walter, Thomas Jefferson University for her critical review of the manuscript.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R21:1R21TW010439-02, NIH P20: 1P20CA210284-01A, Rotary Foundation Global Grant #GG1749568

Footnotes

Supplemental data for this article are available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2020.1785623

References:

- 1.Road traffic injuries. Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries. (Accessed: 26th March 2019)

- 2.Lozano R et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO | World Health Statistics 2007. (2010).

- 4.Road traffic injuries. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries. (Accessed: 26th March 2019)

- 5.Al-Hasan AZ, Momoh S & Eboreime L Urban poverty and informal motorcycle transport services in a Nigerian intermediate settlement: a synthesis of operative motives and satisfaction. Urban, Planning and Transport Research 2015;3:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeleye Amos O., and Ogun Millicent I.. 2017. “Clinical Epidemiology of Head Injury from Road-Traffic Trauma in a Developing Country in the Current Era.” Frontiers in Neurology 8 (December): 695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeleye AO, Clark DJ, Malomo TA. Trauma demography and clinical epidemiology of motorcycle crash-related head injury in a neurosurgery practice in an African developing country. Traffic Inj Prev 2019;20:211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO | The burden of road traffic crashes, injuries and deaths in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. (2018). doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.163121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organization, W. H. & Others. World report on road traffic injury prevention: summary in World report on road traffic injury prevention: summary (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 10.SDG Goal 3 Target 3.6. (World Health Organization, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Road Traffic Report. (Rwanda National Police, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel A et al. The epidemiology of road traffic injury hotspots in Kigali, Rwanda from police data. BMC Public Health 2016;16:697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim WC et al. Vital Statistics: Estimating Injury Mortality in Kigali, Rwanda. World J. Surg 2016;40:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Size of the resident population | National Institute of Statistics Rwanda. Available at: http://www.statistics.gov.rw/publication/size-resident-population. (Accessed: 13th March 2019)

- 15.Rwandan transport authorities to regulate moto taxi, promote cashless payment - Pan African Visions. Pan African Visions (2018). Available at: https://www.panafricanvisions.com/2018/rwandan-transport-authorities-regulate-moto-taxi-promote-cashless-payment/. (Accessed: 17th April 2019)

- 16.Of Kigali’s grand plans to control traffic. The New Times | Rwanda (2013). Available at: https://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/62581. (Accessed: 1st April 2019)

- 17.Nsereko E & Brysiewicz P Injury surveillance in a central hospital in Kigali, Rwanda. J. Emerg. Nurs 2010;36:212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen Ingabire JC, Petroze RT, Calland F, Okiria JC & Byiringiro JC Profile and Economic Impact of Motorcycle Injuries Treated at a University Referral Hospital in Kigali, Rwanda. Rwanda Medical Journal / Revue Médicale Rwandaise 2015;72:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Twagirayezu E, Teteli R, Bonane A & Rugwizangoga E Road traffic injuries at Kigali University Central Teaching Hospital, Rwanda. East and Central African Journal of Surgery 2008;13:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enumah S, Scot JW, Maine R, Uwitonze E, Nyinawankusi JDA, Riviello R, Byiringiro JC, Kabagema I, Jayaraman S. (2016). Rwanda’s model prehospital emergency care service: a two-year review of patient demographics and injury patterns in Kigali. Prehospital and disaster medicine, 31(6), 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.