Abstract

Doxorubicin is a highly effective chemotherapy agent used to treat many common malignancies. However, its use is limited by cardiotoxicity, and cumulative doses exponentially increase the risk of heart failure. To identify novel heart failure treatment targets, we previously established a zebrafish model of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy for small molecule screening. Using this model, we previously identified several small molecules that prevent doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity both in zebrafish as well as in mouse models. In this study, we have expanded our exploration of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by screening 2,271 small molecules from a proprietary, target-annotated tool compound collection. We found 120 small molecules that can prevent doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, including seven highly-effective compounds. Of these, all seven exhibited inhibitory activity towards Cytochrome P450 family 1 (CYP1). These results are consistent with our previous findings in which visnagin, a CYP1 inhibitor, also prevented doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Importantly, genetic mutation of cyp1a protected zebrafish against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity phenotypes. Together, these results provide strong evidence that CYP1 is an important contributor to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and highlight the CYP1 pathway as a candidate therapeutic target for clinical cardioprotection.

Keywords: Cardiology, Cardiovascular disease, Drug therapy, Oncology, Toxins/drugs/xenobiotics

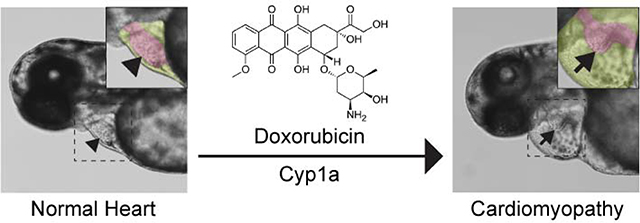

Graphical Abstract

Doxorubicin is a potent chemotherapy agent but its use is limited by cardiotoxic side effects. Using a zebrafish model of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy for small molecule screening, CYP1 was identified as a candidate therapeutic target for clinical cardioprotection.

Introduction

Anthracyclines such as doxorubicin (Dox) are potent chemotherapy drugs used to treat a broad range of cancers including breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma and sarcoma. Dox is one of the most effective antitumor agents; however, patients treated with cumulative doses of doxorubicin above 300 mg/m2 show a dramatically increased rate of cardiotoxicity.[1] With limited cardioprotective treatments available, the cardiotoxic side effects of Dox limit its dosing, thereby potentially impairing cancer treatment outcomes.[2] The exact mechanism for Dox-induced cardiotoxicity remains unclear and is likely multifactorial. To address the limitations of Dox, our laboratory has previously established a zebrafish model of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy and identified cardioprotective compounds that do not interfere with Dox’s ability to kill tumor cells.[3] This Dox-induced cardiotoxicity model recapitulates several key aspects of human disease phenotypes, including increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and reduced heart contractility.[3]

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has proven to be an excellent vertebrate model for disease modeling and chemical screening.[4] It has a high degree of genome and molecular signaling conservation when compared to humans. Zebrafish larvae are small in size, develop rapidly and are optically transparent, making them a suitable tool for high-throughput in vivo drug screening. In addition, the heart of a zebrafish larva can be visualized directly with simple bright-field microscopy, an attribute advantageous for cardiovascular research. A more detailed description of using zebrafish as a preclinical vertebrate cardiovascular disease model for drug discovery is available elsewhere.[5]

We have previously identified that the Cytochrome P450 family 1 (CYP1) enzymes play an important role in Dox-induced cardiotoxicity. Dox causes robust induction of CYP1, and pharmacological inhibition or gene knockdown of Cyp1a prevents Dox-induced cardiomyopathy.[3b] In this study, we extended the in vivo screening approach we previously established to screen 2,271 compounds from a proprietary target-annotated tool compound collection, with the goal of identifying additional targets for doxorubicin cardioprotection, or of confirming CYP1 as a major target for doxorubicin cardioprotection. This compound collection contains small-molecules (MW<500 amu) previously used in other medicinal chemistry programs. The data are curated from 1943 distinct targets across 322 organisms. Details of how these data were captured and curated into the ChemGenie database have been previously disclosed.[6] The screen and subsequent SAR expansion identified additional hit compounds that prevent Dox-induced cardiomyopathy phenotypes. Target enrichment analysis of these compounds, as well as CYP1 inhibition analyses, suggested that a subset of these compounds also inhibit CYP1 activity. Importantly, cyp1a mutant zebrafish were protected against Dox-induced cardiomyopathy phenotypes. Our results, together with our previous findings [3b], suggest that CYP1 inhibition prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity.

Results

Small molecule screening using a zebrafish model of Dox-induced cardiomyopathy

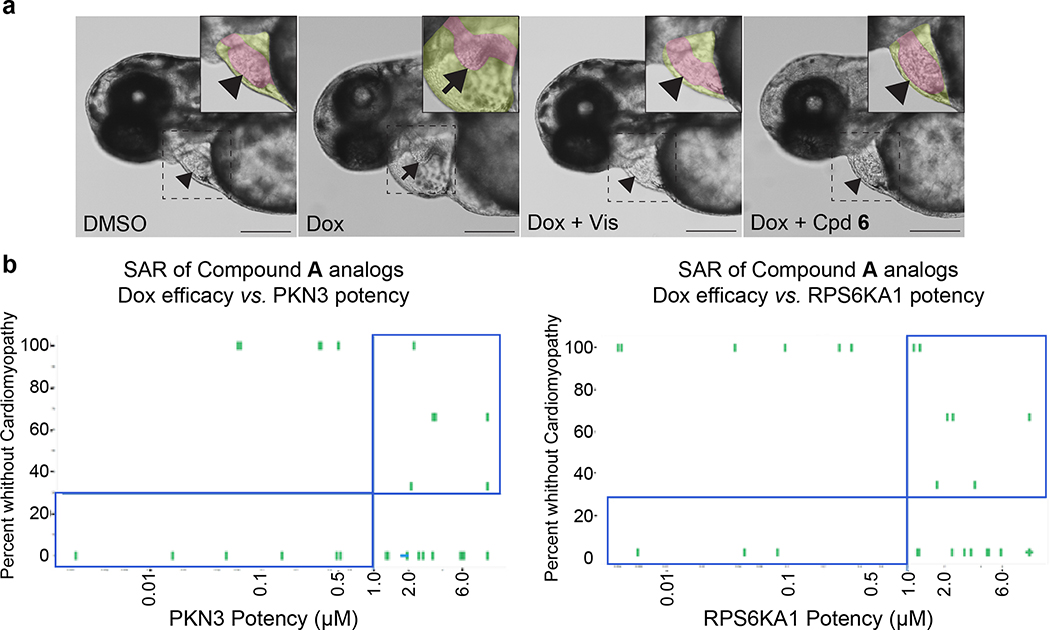

We have previously established an embryonic zebrafish model of Dox-induced cardiomyopathy characterized by decreased cardiac contraction, pericardial edema, and decreased blood flow through the vasculature.[3a] Using this model for small molecule screening, a cardioprotective phenotype is defined by having normal cardiac contraction and blood flow, as well as no pericardial edema (Fig. 1a). In this screen, each compound was tested on six embryos co-treated with Dox and the number of embryos showing rescued phenotypes was counted.

Fig. 1.

Zebrafish doxorubicin model and effect of compound treatment. (a) Representative images showing the morphology of the zebrafish heart at 3 days post fertilization with treatments indicated. Dotted square indicates the region where inset image was made. Pseudo-color was used in the inset image to highlight the heart (magenta) and pericardium (yellow). DMSO, 1% DMSO control treated; Dox, 100 μM doxorubicin treated; Dox + Vis, 100 μM doxorubicin and 20 μM visnagin co-treated, Dox + Cpd 6, 100 μM doxorubicin and 10 μM compound 6 co-treated. Arrowhead and arrow indicate normal and abnormal heart morphology, respectively. Scale bar = 200 μm. (b) Zebrafish efficacy in the doxorubicin model for a given compound is plotted on the y-axis and its potency for an annotated target is plotted on the x-axis. 10 μM compound A was used. In this representative case, zebrafish efficacy cannot be directly attributed to its potency at the annotated target. Compounds exhibiting inconsistent correlation between its in vitro activity at the target and in vivo efficacy are highlighted in the blue rectangle.

In the first round of screening, 2,271 compounds from a compound collection annotated with biological targets were tested at a 10 μM concentration. This screening concentration was used because, based on our experience with previous zebrafish screens, it yields a manageable hit rate without producing high rates of non-target specific toxicity. From this screen, 81 compounds showed rescue in 6 out of 6 embryos tested while 44 compounds showed rescue in 5 out of 6 embryos. Subsequently, these 125 hit compounds were selected for dose response experiments to generate dose-response curves and derive maximal effective concentration EC100 values. The number of compounds with EC100 >10 μM, 10 μM, 3.3 μM, 1.1 μM, 0.37 μM, and 0.12 μM was 18, 46, 35, 13, 7 and 1, respectively.

We then investigated the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of several chemotypes. Several compounds showed efficacy in the Dox model with EC100s between 0.12 μM – 1.1 μM. Subsequent SAR around these compounds was explored to determine if the annotated target was responsible for the efficacy in the doxorubicin model. For this study, 387 SAR compounds were tested in full dose response. The number of compounds with EC100 >10 μM, 10 μM, 3.3 μM, 1.1 μM, 0.37 μM, and 0.12 μM was 255, 46, 32, 28, 18 and 8, respectively. SAR expansion led to the identification of more potent compounds in the Dox assay.

However, the efficacy of these SAR compounds did not correlate well with the potency of their annotated targets (Fig. 1b). For example, one hit in the zebrafish screening assay, Compound A, was selected for further profiling in two SAR studies. Compound A was annotated in the CHEMGENIE database as having sub-micromolar potency for two targets, PKN3 and RPS6KA1. The targets of interest were interrogated by expanding the SAR of the hit compound to include analogs possessing a range of potencies. It would be expected that if inhibition of a particular target was responsible for the efficacy in the zebrafish model, rescue of the cardiomyopathy would be evident with compounds that are more potent at the annotated target. Additionally, compounds inactive at the annotated target should not rescue the cardiomyopathy. For both targets, potent compounds failed to rescue the cardiomyopathy phenotypes. Furthermore, the rescue of Dox-induced cardiomyopathy was seen with compounds that are inactive at the annotated targets. These results suggest that targets other than these two annotated targets in our screening collection may be responsible for efficacy in the Dox model. A key assumption in this analysis is that potency for the human target is comparable for the zebrafish homolog. It should be noted that this was not experimentally confirmed. As the SAR of annotated target potency was not consistent with efficacy in the Dox model, as with many of the hit compounds, we turned our attention to a target enrichment analysis.

Determination of CYP1A1 as a putative target

A target enrichment analysis[6] was performed as described in the methods. From this analysis, Cytochrome P450 family proteins were among the top target candidates identified (Table 1). Our previous findings showed that Dox treatment induced significant upregulation of the CYP1 family of enzymes (CYP1A, CYP1B1, and CYP1C1). Co-treatment of Dox with a previously identified hit compound, visnagin, showed significantly less CYP1 induction and a rescue of Dox-induced cardiomyopathy phenotypes in zebrafish.[3b] Based on these findings and the current target enrichment analysis, we have selected members of the cytochrome P family as the target candidate pathway for further analysis.

Table 1.

The top target candidates identified by target enrichment analysis.

| Symbol | Protein | Normalized Probability |

|---|---|---|

| CYP11B2 | cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily B member 2 | 2.09 |

| GRM5 | glutamate metabotropic receptor 5 | 1.95 |

| CYP11B1 | cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily B member 1 | 1.74 |

| CYP1A2 | cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 2 | 1.37 |

| CYP8B1 | cytochrome P450 family 8 subfamily B member 1 | 1.37 |

| TTK | TTK protein kinase | 1.27 |

| GRM7 | glutamate metabotropic receptor 7 | 1.25 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | 1.21 |

| GRM3 | glutamate metabotropic receptor 3 | 1.16 |

| PTGES | prostaglandin E synthase | 1.12 |

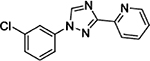

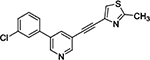

To determine if any of these hit compounds also target CYP1A as previously reported,[3b] a CYP1A inhibition assay was performed with compounds 1 – 7 (Table 2). Compounds 1 and 2 were discovered through an SAR study around the annotated target GRM5 (target enrichment score 1.95, rank 2/1125 targets). Both structurally similar and distinct compounds were active in the Dox model. However, structurally similar compounds which were inactive for GRM5 were also active in the Dox model. This discrepancy was consistent with several other examples where the annotated target may not be responsible for efficacy in the Dox model. Further inspection of the activity profiles of these compounds revealed that these compounds were potent inhibitors of CYP1A (Table 2, Supp. Fig. 1). We were encouraged by these findings and by previously published results suggesting that GRM5 antagonists may be substrates for CYP1A1/1A2 isoforms.[7] Therefore compound 3, a structural derivative of 3-((2-methyl-4-thiazolyl)ethynyl)pyridine (MTEP) which is a potent and selective GRM5 antagonist, was selected for evaluation and exhibited an EC100 of 41 nM in the Dox model.

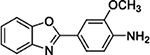

Table 2.

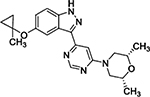

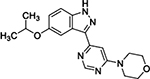

Chemical structure of compounds selected for further profiling and their corresponding inhibitory activity on human CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, as well as efficacy in the zebrafish Dox model.

| Compound | ZF EC100 (nM) | CYP1A1 % Inhibition @ 10000 nM | CYP1A2 % Inhibition @ 10000 nM |

|---|---|---|---|

1

|

1100 | 87.2 | 37.1 |

2

|

1100 – 2200 | 101.3 | 76.8 |

3

|

41 | 99.5 | 98.1 |

4

|

730 – 1100 | 107.6 | 18.8 |

5

|

27 – 82 | 97.6 | 80.6 |

6

|

1100 | 96.2 | −14.2 |

|

7 |

246 | 98.2 | 93.9 |

In a separate SAR campaign, compound 4 was found to be active in the Dox model with an EC100 of 1.1 μM; however, it was striking that many structurally similar and distinct compounds which were potent for LRRK2 (weighted target enrichment score 0.91, ranked 25/1125) were inactive in the Dox model. Additionally, several structurally similar compounds were also inactive in the Dox model. Further inspection of the activity profile of 4 in the CHEMGENIE database showed that this compound was a potent inhibitor of CYP1A. One structurally similar (ECFP4 Tanimoto = 0.82) analog, 5, displayed efficacy in the Dox model with an EC100 of 41 nM. Compound 5 was found to be a potent CYP1A1 inhibitor, supporting the hypothesis that CYP1A inhibition was responsible for efficacy in the Dox model.

With these insights, we investigated a 2-phenyl-benzoxazole chemotype, represented by compounds 6 and 7, which exhibited activity in the Dox model, with EC100s of 1.1 μM and 370 nM, respectively. Although the annotation of these compounds did not converge on a particular target in our CHEMGENIE database, nor did the activities at any one target possess potency < 500 nM, we were intrigued to determine if the efficacy of these compounds in the Dox model could be attributed to CYP1A activity. Both 6 and 7 proved to be potent inhibitors of CYP1A1 (Table 2; Supp. Fig. 1); thus, lending increased support to the hypothesis that CYP1A inhibition was responsible for efficacy in the Dox model of cardiomyopathy.

CYP1A is a key mediator of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy

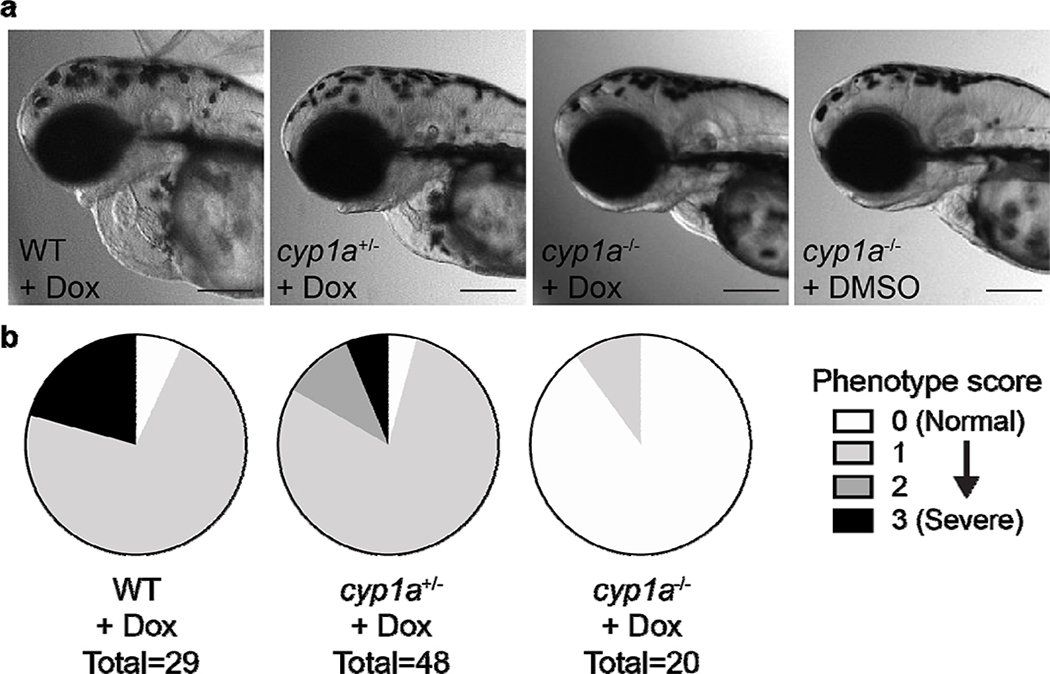

As CYP1A was identified as the putative target of hit compounds from the screen, we sought to determine if cyp1a knockout animals are protected from doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. We generated a cyp1a-null mutant zebrafish line using CRISPR-Cas9 technology with five guide RNAs targeting the putative active site residues of cyp1a, as previously described for transient knockdown experiments.[3b] cyp1a homozygous mutant animals developed normally and showed no morphological defects in the heart. Upon doxorubicin treatment, homozygous cyp1a mutants showed no doxorubicin-induced cardiac phenotypes (Fig. 2). Overall, our results suggested that cyp1a is an important contributor to doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy, and inhibition or genetic disruption of CYP1A protects animals from developing the adverse cardiac phenotypes induced by doxorubicin.

Fig. 2.

Zebrafish cyp1a mutation protected against Dox-induced cardiotoxicity. (a) Representative images showing the morphology of the WT or cyp1a mutant zebrafish heart at 3 days post fertilization with treatments indicated. DMSO, 1% DMSO control treated; Dox, 100 μM doxorubicin treated. Scale bar = 200 μm. (b) Quantification of cardiotoxicity phenotypes of WT or cyp1a mutant zebrafish treated with doxorubicin. Scoring of cardiotoxicity phenotypes includes decreased tail blood flow, decreased cardiac contractility, and pericardial edema. Each of these phenotypes is scored as 1. Phenotype score is the summation of all phenotypes present. 0 = normal morphology. 3 = all three cardiotoxicity phenotypes present.

Discussion

We have performed a phenotype-based, in vivo chemical screen of a proprietary annotated compound collection to identify compounds that prevent Dox-induced cardiotoxicity in zebrafish. The screen delivered robust, reproducible hits with a hit rate (6/6 rescue) of approximately 2%. For most hits, prevention of cardiotoxicity was virtually complete and dose dependent. SAR expansion was performed around several different chemotypes and in some cases appears to have produced compounds with improved potency.

Target enrichment analysis was used to identify annotated targets that were enriched among the hit list. Several potentially enriched targets were identified, and target hypotheses were tested by determining the effect of structurally divergent ligands for those targets. In most cases, no correlation was identified between in vitro potency toward the enriched, hypothetical target and in vivo cardioprotection in zebrafish. However, one hypothesized target, the CYP1A family, did appear to correlate with cardioprotection. Several potent and structurally divergent hits from the assay were found to be potent CYP1A1 ligands. The seven hit compounds depicted in Table 2 belong to five structurally distinct compound classes. Although we demonstrate here that all seven inhibit CYP1A proteins (Table 2), most or all of the hit compounds were included in the screening collection because of their annotated activity at non-CYP1A targets. For example, compounds 1–3 had been annotated as targeting GRM5, while compounds 4–5 had been annotated as targeting LRRK2. It remains to be determined whether or not targeting of GRM5 or LRRK2 contributes to the efficacy of the hits, but their ability to inhibit CYP1A1 appears to be the dominant factor influencing efficacy. Although we do not currently have data that strongly prioritize one hit over another, future efforts may focus on development of more CYP1-selective compounds, which then may exhibit fewer off-target activities during Dox treatment.

Because the previously identified cardioprotectant visnagin is known to inhibit CYP1A, we initiated the screen with the hypothesis that CYP1A is involved in visnagin’s mechanism of action, but we could not exclude the possibility that visnagin had other relevant targets, and we anticipated the screen would identify compounds that protected against doxorubicin through other targets. Surprisingly, the seven potent hits from the screen are structurally divergent but all inhibit CYP1A, confirming that CYP1A inhibition is an effective strategy for protecting the heart from doxorubicin in zebrafish. Furthermore, the observation that cyp1a mutant zebrafish are resistant to DOX cardiotoxicity indicates that disruption of CYP1A function alone is sufficient for DOX cardioprotection. These results suggested that cyp1a is a key contributor to doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in zebrafish.

We conclude that inhibition of CYP1A-family targets may effectively mitigate anthracycline toxicity in zebrafish. Whether CYP1A proteins influence doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through production of a cardiotoxic metabolite, or through some other means, remains to be determined. Future work beyond the scope of this paper should focus on determination of the doxorubicin metabolites formed by zebrafish, and exploration of conservation in mammalian models.

Conclusions

We screened a small molecule compound collection in a zebrafish model of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy (Supp. Fig. 2). From this screen, 120 compounds were identified as hits. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies around the annotated targets of these hits revealed that SAR around the annotated target was not consistent with the efficacy in the zebrafish model. A target enrichment analysis of this data set suggested that Cyp1 may be responsible for the efficacy of these compounds. In subsequent studies, we showed that several compounds active in doxorubicin model were Cyp1 inhibitors. Furthermore, cyp1a mutant zebrafish are protected against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Our results further confirm that CYP1 is an important contributor to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and suggest the CYP1 pathway as a therapeutic target for clinical treatment.

Methods

Zebrafish Dox model

TuAB zebrafish embryos at 30 hours post fertilization (hpf) were used for the doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity assay as previously described.[3] Briefly, experiments were performed in 96-well plates containing three embryos per well. At 30 hpf, embryos were treated with 100 μM Doxorubicin hydrochloride (Dox; Tocris Bioscience, cat. No. 2252) and co-dosed with screening compound. A proprietary annotated compound collection of 2,271 small molecules was used for the screen. In the first round of screening, 10 μM of each compound was co-dosed with 100 μM of doxorubicin in two replicate wells (six embryos total). Phenotypic cardioprotection was assessed at 40 hours post treatment. The cardiomyopathy phenotypes (decreased cardiac contraction, pericardial edema, and decreased tail blood flow) were assessed under light microscopy (5x magnification). Manual assessment for the presence or absence of these cardiomyopathy phenotypes was performed for each embryo. The number of embryos rescued from the cardiomyopathy phenotype was quantified for each compound tested. A hit was defined as a compound having ≥ 5/6 fish rescued from Dox-induced phenotypes. Zebrafish were considered to be rescued from the Dox-induced cardiomyopathy if all three features of the phenotype were absent. For those compounds demonstrating activity in zebrafish, dose response experiments were performed in 1/3 serial dilutions (10 μM, 3.3 μM, 1.1 μM, 0.37 μM, 0.12 μM, 0.041 μM, 0.014 μM, 0.0045 μM) to generate concentration response curves and calculate EC100 values. The same dose response experiments were performed in subsequent SAR compounds. Animals were maintained and embryos were obtained according to protocols approved by the University of Utah’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

SAR expansion

Select compound hits from the zebrafish model were selected for further SAR studies. For each compound of interest, an SAR study was conducted to investigate whether the compound’s potency on a particular target was responsible for the compound rescue from doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Targets of interest were defined when a hit compound showed <1 μM potency for that target as defined in our CHEMGENIE database.[6] In order to further explore if this annotated target was responsible for the efficacy in the Dox model, we selected a set of active compounds which were structurally similar to the initial hit, a set of active compounds which were structurally distinct to the initial hit, and a set of inactive compounds which were structurally similar to the initial hit. For this SAR investigation, compounds were considered structurally similar to the hit compound with a Tanimoto coefficient > 0.80 and were considered structurally distinct from the hit compound with a Tanimoto coefficient < 0.50. Tanimoto coefficients were calculated using an ECFP4 fingerprint. A compound was considered to be active on the target if its potency was < 500 nM. A compound was considered to be inactive on the target if its potency was > 1 μM. Selected compounds were tested for their ability to rescue three zebrafish at different concentrations (10 μM, 3.3 μM, 1.1 μM, 0.37 μM, 0.12 μM, 0.041 μM, 0.014 μM, 0.0045 μM) as described above. Zebrafish rescue is expressed as a percentage of fish rescued from the cardiomyopathy (0, 33%, 66%, 100%).

Weighted target enrichment analysis

To assess if compounds associated with particular targets were more likely to be active in the Zebrafish Dox model, a target enrichment analysis was performed. Compounds were first categorized - those capable of saving ≥ 5 fish in the Zebrafish Dox model were considered “hits,” and all other compounds were considered “non-hits.” A Naïve Bayesian model was trained on the hits versus non-hits, using known targets associated with the compounds as descriptors. The tool compound score, ranging from 0–1 and previously described,[6] for each compound-target interaction was used to “weight” the association between the compounds and targets. That is, when a compound-target pair had a high score, the target was associated as a feature more times for that compound. Likewise, if the tool score for a target was < 0.4, the target was not considered as a feature. If considered a feature (tool score > 0.4), the number of times a particular target was associated with a compound depended on the tool score (1 for 0.4 < tool score ≤ 0.5, 2 for 0.5 < tool score ≤ 0.6, 3 for 0.6 < tool score ≤ 0.7, and so on). The normalized probability (NPi) associated with each of the features (targets) was extracted from the Naïve Bayes model, and used to rank the targets.

| (1) |

where Hi is the number of target i features associated with active compounds, Ti is the total number of target i features, H is the total number of target features associated with active compounds, and T is the total number of target features associated with all compounds. Although we performed target enrichment at each step of the screen (initial screen, SAR expansion, etc), the target enrichment reported in Table 3 includes results for the initial tool library as well as compounds identified by the initial SAR expansion.

In order to generate the tool score used in the weighted target enrichment described above, targets that are homologues as defined by the HomoloGene ID [8] were first grouped together. We represent each target with a representative gene id – the human gene id if it is present in the group of targets mapping to the HomoloGene ID.

CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 Inhibition Assay

CYP1A1 inhibition experiments were performed by Cerep Panlabs (Eurofins) using human liver microsomes and phenacetin substrate (Assay # 2064). CYP1A2 inhibition experiments were performed by Cerep Panlabs (Eurofins) using recombinant CYP1A2 and 3-cyano-7-hydroxycoumarin, CEC, substrate (Assay #389). Mean percent inhibition was calculated using the furafylline reference inhibitor. Seven compounds were tested at four concentrations (10 μM, 1 μM, 100 nM, 10 nM). All concentrations were tested in duplicate.[9]

Generation of Cyp1a Mutant Zebrafish

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis was performed using five guide RNAs multiplexed to target the following sites in the putative active site of the zebrafish Cyp1a gene (exon 2; 5’ to 3’): CGATGAGTTCGGGAAGATCG; GCGGGATCTGTTTCGGACGC; GAATGGATCAAAGCTTCCAT; GCCCGTCTGGGATTTTCGTG; CGACAGGCGCTCCTAAAACA (citation 4). Potential founder fish were screened using gene fragment analysis, and a stable transgenic line was generated. Sanger sequencing of the mutated allele demonstrated an 8 bp insertion followed by a 72 bp deletion as follows (insertion; [deletion]): AGTATCCGTGGCTAACGTAATCTGCGGGATCTGTTTCATAAAGCG[GGACGCCGGCATAGTCATGATGATGATGAACTGGTGCGACTGGTTAATATGAGCGATGAGTTCGGGAAGATC]GTGGGCAGCGG.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Merck & Co., Inc. AA was supported by NIH K08HL145019 and a Scholar Award from the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

References

- [1].Suter TM, Ewer MS, Eur Heart J 2013, 34, 1102–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McGowan JV, Chung R, Maulik A, Piotrowska I, Walker JM, Yellon DM, Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2017, 31, 63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a Liu Y, Asnani A, Zou L, Bentley VL, Yu M, Wang Y, Dellaire G, Sarkar KS, Dai M, Chen HH, Sosnovik DE, Shin JT, Haber DA, Berman JN, Chao W, Peterson RT, Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 266ra170; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Asnani A, Zheng B, Liu Y, Wang Y, Chen HH, Vohra A, Chi A, Cornella-Taracido I, Wang H, Johns DG, Sosnovik DE, Peterson RT, JCI Insight 2018, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lam PY, Peterson RT, Curr Opin Chem Biol 2019, 50, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pott A, Rottbauer W, Just S, Expert Opin Drug Discov 2020, 15, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kutchukian PS, Chang C, Fox SJ, Cook E, Barnard R, Tellers D, Wang H, Pertusi D, Glick M, Sheridan RP, Wallace IM, Wassermann AM, Drug Discov Today 2018, 23, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Green MD, Yang X, Cramer M, King CD, Neurosci Lett 2006, 391, 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W, J Comput Biol 2000, 7, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dierks EA, Stams KR, Lim HK, Cornelius G, Zhang H, Ball SE, Drug Metab Dispos 2001, 29, 23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.