Abstract

This paper examines the rapid spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its short-term impact on the Shariah-compliant UK Dow Jones market index to capture the dynamic behavior of stock returns at economy and industry levels. Using daily data over the period January 20 to May 20 and ten UK industrial sector groupings, the findings suggest a strong and statistically significant relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and the performance of the conventional stock market index. The findings also suggest that the disease interacts negatively but insignificantly with the Dow Jones faith-based ethical (Islamic) index compared to its UK counterpart. In addition, through an analysis of sector groupings, the paper shows that the stock returns of the information technology sector performed significantly better than the market, while stock returns of consumer discretionary sector, which includes transportation, beverages, tourism and leisure, consumer services performed significantly worse than the market during the COVID-19 outbreak. Other sector groupings fail to yield significantly plausible parameter values.

Keywords: Coronavirus (COVID-19), Behavioral finance, Stock market indices, Faith-based investments

1. Introduction

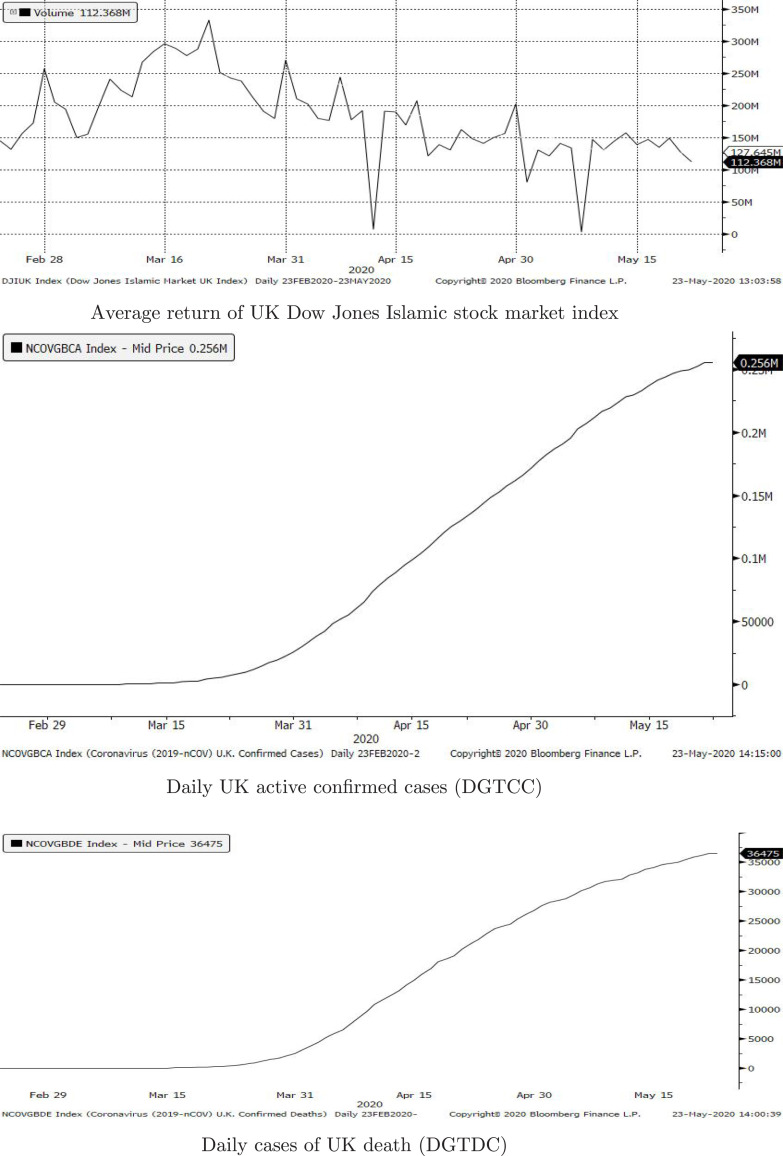

The coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak is an increasingly pervasive and influential economic challenge in modern history. The novel virus has rapidly spread across borders with more than 5,049,497 confirmed infections and 367,230 deaths in more than 195 countries and territories worldwide, carrying a mortality of approximately 6.07% compared with a mortality rate of less than 1% from influenza (WHO, 2020, Gormsen and Koijen, 2020, Lekhraj Rampal and Seng, 2020, Peters et al., 2020). Pandemics rarely affect all people and economies in a uniform manner (Duncan and Scott, 2005, Carlsson-Szlezak et al., 2020, Buklemishev, 2020, Papava and Charaia, 2020, Mogaji, 2020, He et al., 2020). For example, the UK is at present a highly volatile economy in terms of uncertainty in investment and production output due to the ongoing uncertainty and impact of Brexit and the unprecedented average of daily active confirmed cases and daily confirmed deaths caused by COVID-19 as seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

UKIDJ Index & COVID-19.

Beyond the immediate tragedies of death and disease, indirect effects through fear are taking hold of a significant number of people and investors around the world, which has had dramatic impacts on financial markets all over the world (Liu et al., 2019, Papadamou et al., 2020, Carter et al., 2020, Duxbury et al., 2020, Al-Awadhi et al., 2020). Hence, the spread of COVID-19 has had a major impact on the performance of stock market indices globally, as can be seen from Table 1. For example, the worldwide international equities represented by the S&P Global BMI fell 22.3% during Q1 2020. The S&P Global BMI Shariah, which only fell 17.2%, considerably outperformed its conventional peers by more than 500 bps. This tendency has been consistently achieved across all major regions, as the S&P500 Shariah outperformed its conventional peers by 2.7%, while the Dow Jones Islamic Market (DJIM) Europe and DJIM Emerging Markets have both outperformed their conventional peers by more than 8.0%.1

Table 1.

Comparative regional returns.

| % | % | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S&P Global BMI | −17.2 | −22.3 | 5.1 |

| DJIM World | −16.6 | −22.0 | 5.4 |

| S&P500 | −16.9 | −16.6 | 2.7 |

| DJIM Asia | −14.3 | −19.8 | 5.5 |

| DJIM Europe | −16.8 | −24.8 | 8 |

| DJIM developed markets | −16.7 | −21.6 | 5 |

| DJIM emerging markets | −15.9 | −24.4 | 8.5 |

| S&P Pan Arab composite | −20.6 | −23.4 | 2.5 |

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC-Index performance based on the total return in USD. Islamic World (IW); Islamic Euro (IE); Islamic Asia Pacific (IAP); Islamic Developed countries (ID); Islamic Emerging markets (IEM); Islamic United States (IUS); Islamic United Kingdom (IUK); Islamic Oil and Gas (IOG); Islamic Technology (IT); Islamic Healthcare (IHC); Islamic Consumer Goods (ICG); Islamic Consumer Services (ICS).

Much attention has been focused on the economic impact of Brexit on the UK economy, and this has been further amplified with the current financial and pandemic crisis (Liu et al., 2020, Fernandes, 2020, Davies and Studnicka, 2018). Consequently, decisions and variations associated with the performance of conventional and non-conventional stock market indices are clearly an empirical question of some importance. It is worth noting that investors are interested in investments with escalated profits, hence the Shariah-compliant market indices should be efficient and competitive to the conventional counterpart (Rehman et al., 2020, Balcılar et al., 2015, Hammoudeh et al., 2014).

With the significant rise in the number of crises facing the conventional financial system such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, stock market investors (i) perceive stock returns as being uncertain and became more attentive; (ii) are rational and hence have inquired for information on the fundamentals of Shariah related investment structures and characteristics. Clearly, virus crises that hit conventional financial systems are less harsh for the Islamic financial system (Balcılar et al., 2015). There are indeed differences between Shariah and non-Shariah complaint indexes in terms of screening and financial characteristics. For investment screening, the Shariah complaint indexes are growth focused small-cap industries; whereas the conventional indices are more value-focused mid-cap industries with higher environmental risk such as investments in energy industries (Hassan and Girard, 2010). In the case of financial characteristics, Shariah complaint indexes are characterized by low leverage and low account receivables, which reduce the financial risks and vulnerabilities related to periods of crisis such as COVID-19 (Farooq and Alahkam, 2016). Hence, extensive attention has been devoted to such faith-based investments (Hussain et al., 2019, Alam and Seifzadeh, 2020, Zandi et al., 2019, Sherif, 2016, Sherif and Erkol, 2017, Rifqi, 0000, Sherif and Hussnain, 2017, Kalimullina, 2020, Sadeghi et al., 2008, Derigs and Marzban, 2008, Alotaibi and Hariri, 2020, Seyyed et al., 2020, Tahir and Ibrahim, 2020, Akguc and Al Rahahleh, 2020, Ahmad et al., 2020, Fu et al., 2020, Castro et al., 2020).

Over the past several decades, Islamic finance has witnessed a remarkably broad expansion and unprecedented growth. It has grown from just $200bn in 2003 to an estimated predicted total of over $4 trillion in assets by 2030 (Alam and Seifzadeh, 2020). It is now offered in more than 60 countries and over 300 Islamic financial institutions. Globally, approximately 0.5% of financial assets are estimated to be under Sharia-compliant management. The industry’s total worth is estimated to be USD 3.50 trillion in 2020, denoting a 10.3% growth in assets in USD terms. Such significant growth has recently also extended to many non-Muslim countries in Asia and Europe (Alam, 2019). This is due to a broad diversification in cultures with a considerable number of Muslims immigrants (Alam and Seifzadeh, 2020).

Arguably the most contentious issue about faith-based investments vehicle is whether ethical overlays have a bearing on financial performance. Whilst a number of previous studies have considered this area (Hammoudeh et al., 2014, Al-Khazali et al., 2014, Fu et al., 2020, Abu-Alkheil et al., 2020, Umar et al., 2020, Climent et al., 2020, Haddad et al., 2020, Rehman et al., 2020, Anjum, 2020, Widyanata and Bashir, 2020, Sherif, 2016), much uncertainty remains regarding the significant differences between conventional and faith-based investments. The general perception and critique facing ethical investments stem from their contradiction with the principles of the efficient portfolio theory of Markowitz 1952, cited in Dhrymes (2017).2 It has been claimed that ethical investments underperform in the long run because they are subsets of the market portfolio and lack sufficient diversification (Bauer et al., 2005, Goodchild et al., 2002). Hence, investors regularly diversify their portfolios, aiming to minimize risk and maximize returns. However, several previous studies exhibit a general disagreement regarding the claim that faith-based investments (ethically screened firms) outperform their non-ethical screened counterparts (Charles et al., 2015, Masih et al., 2018, Sherif, 2016).

Inspired by the above arguments and the potential impact of evolution of the current COVID-19 pandemic crisis, this study examines and provides new evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on the performance of the Dow Jones Islamic market index compared to the FTSE100 index. In essence we investigate the relative importance of the Shariah-compliant Dow Jones market index to capture the dynamic behavior of stock returns at economy and industry levels. Thus, this study contributes to the existing literature in several ways: (1) while most empirical and theoretical research focuses heavily on investors’ attention and its impact on conventional stock returns/indices (Andrei and Hasler, 2015, Da et al., 2015), there is only limited academic research conducted on examining the performance of faith-based investments (ethical stock market index) and investor attention to the coronavirus pandemic, which is an important and ultimately new empirical question. In particular, the main research question to be answered in this study is formed as follows: is there a significant difference of stock returns between Shariah and conventional investments?; (2) this study contributes to the contemporaneous, but exponentially growing, literature on the effects of COVID-19 on the performance of financial markets (Alfaro et al., 2020, Gormsen and Koijen, 2020, Zhang et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Faith-based investments vs. conventional investments.

| Faith-based investments | Conventional investments |

|---|---|

| Asset-based investments | Interest-rate based investments |

| More desirable in the short-run | More desirable in the long-run |

| Based on the principles of profit and loss sharing (religion’s law) | Based on the principles of interest and usury |

| Investors maximize wealth by choosing among various faith compliant Investments | Investors evaluate investments based upon risk-return characteristics |

| Invest capital in line with a specific named faith | Invest capital for a proportionate interest of the fund’s net assets |

| Avoid investing in industries or companies that conflict with beliefs | Invest money into assets that are well-known |

| Generate a positive social impact inspired by their faith, Islamic, Catholic, and other religion’s law | Generate an unmeasurable social impact alongside a financial return |

The remainder of this paper is structured and further organized as follows. Section 2 presents a detailed literature review. Then the research methodology and data are discussed in Section 3. Section 4 shows our empirical results. Section 5 then concludes, considering the significance of our key findings and outlining a number of avenues for future research.

2. Literature review

Significantly, there is a much controversy and debate regarding the performance of faith-based investments when compared to their conventional counterparts. Recently, Shariah compliant investments, which represent aspect of the ethical and ‘restricted’ finance, have been the focus of a growing body of empirical research for a number of reasons; (i) the growing debate advocated by modern financial theory claiming that Shariah-compliant indices are riskier than their conventional peers due to their lack of diversification (Albaity and Ahmad, 2008); (ii) the assumption that faith-based ethical (Islamic) indices are more profitable than their peers due to their passing extra-financial screening criteria (Atta-Alla, 2012, Hussein and Omran, 2005).

Among the previous studies on Shariah compliant investments, a few have focused on the Dow Jones Islamic stock market Index (DJIMI) (Al-Khazali et al., 2014, El Khamlichi et al., 2014, Ho et al., 2014, Charles et al., 2015, Shamsuddin, 2014, Jawadi et al., 2014, Ftiti and Hadhri, 2019, Charles et al., 2017). The majority of these studies have followed the same methodologies of comparing the performance of DJIMI to other benchmarks, but the choices are somewhat different from one study to another depending on the performance measures and benchmarks used. For example, Al-Zoubi and Maghyereh (2007) find that the Islamic index outperforms the Dow Jones World Index; and that the former is less risky than the benchmark, suggesting this finding can be attributed to the profit and loss sharing principle in Islamic finance. In another study, Hassan and Girard (2010) examine the market efficiency and time-varying risk-return relationship using DJIM and the volatility of the DJIM index. Their study finds that the DJIM has outperformed the conventional indices; and the reward to risk and diversification benefits are similar in both indices. In contrast, Hakim and Rashidian (2002), Miniaoui et al. (2015), Girard and Hassan (2008), and Hoepner et al. (2011) find only insignificant differences between the performance of conventional and non-conventional indexes.

Another group of studies (Dhai, 2015, Becchetti et al., 2015, Sherif, 2016, Durand et al., 2016, Umer et al., 2019, Bauckloh et al., 2019, Landi and Sciarelli, 2019, Shaikh et al., 2019, Vasisht, 2017, Anwaar, 2016, Wu et al., 2017) has investigated the performance of the FTSE and other Islamic indices, and provide an overall picture of somewhat mixed findings. For example, Tahir and Ibrahim (2020) find that Shariah-compliant companies (SCCs) outperformed non-Shariah compliant companies in terms of both accounting and market returns. In another study, Anwaar (2016) finds supportive evidence of the relationship between firm performance and FTSE100 stock market returns. Wu et al. (2017) demonstrate that the socially responsible investment (SRI) portfolio performed better and recovered its value quicker post-crisis than did the non-SRI portfolio.

Following on from this, more recent research has started to utilize increasingly more available data to investigate Islamic and conventional investments (Trabelsi et al., 2020, Ahmed and Elsayed, 2019, Hasan and Abu, 2019, Trabelsi, 2019, Jawadi et al., 2019). For example, Trichilli et al. (2020a) investigated the portfolio optimization under investor’s sentiment states of Hidden Markov model; and find that the Bayesian efficient frontier of Islamic and conventional stock portfolios is affected by the investor’s sentiment state and the time horizon. In a separate study, Trichilli et al. (2020b) also examined the capability of the hidden Markov and investor sentiments to predict the dynamics of Islamic index’ returns in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) financial markets. They find that the effect of sentiment on predicting the future Islamic index returns is conditional on the MENA region. In another study, Abduh (2020) investigated the volatility of conventional and Islamic indices and the impact of the global financial crisis toward the volatility of both markets in Malaysia; and finds that Islamic index was less volatile during the crisis compared to the conventional index. In another key study, Haddad et al. (2020) examined the importance of permanent versus transitory shocks as well as their domestic and foreign components in explaining the business cycle fluctuations of seven Dow Jones Islamic stock markets (DJIM). They found that seven Dow Jones Islamic stock indices are insignificantly linked to the movements of global risk factors. Similarly, Boubaker et al. (2020) examined the common movement of three commodities (Oil, gas and gold) and the Dow Jones Islamic market index (DJIM). Their study indicated using Wavelet Squared Coherence (WSC), that there is a co-movement between DJIM and oil prices; and investors in Islamic stock market indices are yet to base their decisions on oil, gas or gold prices.

One further key argument that has recently been given much attention is related to different sources of financial volatility and major events that have affected stock market returns (Zhu et al., 2019, Corbet et al., 2020, Zaremba et al., 2020, Albulescu, 2020, Onali, 2020, Choudhry et al., 2016, Demirer et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2018, Antonakakis and Darby, 2013). These sources of financial volatility are market uncertainty due to disasters (Kowalewski and Śpiewanowski, 2020, Liu et al., 2019;Papadamou et al., 2020), economic conditions and political events (Bash and Alsaifi, 2019), institutional issues and social Media news (Bollerslev et al., 2018, Reboredo and Ugolini, 2018), environmental issues (Alsaifi et al., 2020), information demand and investor attention (Chronopoulos et al., 2018, Nikkinen and Peltomäki, 2020), and pandemic diseases (Chen et al., 2009, Ichev and Marinč, 2018). In this strand, Albulescu (2020) examined the impact of official announcements regarding new cases of infection and death ratios on the financial market volatility index (VIX); and finds that the death ratio positively influences VIX. In other words, the higher the number of affected countries, the higher the financial volatility is. In another study, Corbet et al. (2020) investigated the impact of global COVID-2019 pandemic on the volatility of stock markets; and find that a significant relationship between Chinese stock markets and Bitcoin evolved significantly during this period of enormous financial stress. Similarly, Mei and Guo (2004) examined the impact of political uncertainty on financial crises using a panel of 22 emerging markets; and find a significant relationship between political election and financial crisis. Also, Zaremba et al. (2020) examined the stringency of policy responses to the novel coronavirus pandemic in 67 countries around the world; and find that non-pharmaceutical interventions significantly increase equity market volatility. In the same vein, Chen and Chiang (2020) find evidence that a rise in economic policy uncertainty (EPU) leads to a decline in stock returns in the Chinese market. In the same line, Kowalewski and Śpiewanowski (2020) examined the stock market reaction to disasters; and find that the affected mining firms experience a cumulative drop in their market value of 1.15% in the first two days of a disaster.

From this review of previous literature here, it is noted that despite the multiplicity of previous empirical work focusing on the analysis of Islamic and conventional stock markets performance, the results are highly divergent and no consensus has been reached to date. In the same context, this paper attempts to fill the gap in the literature to deal with this same concept of performance. However, unlike previous studies, we try to give special importance to the current coronavirus pandemic, econometric techniques and the dynamic behavior of stock returns at economy and industry levels.

Table 3.

Summary statistics.

| Variable |

Panel A: Faith-based DJIUK Index |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.0015 | 13.63 | 4.369 | 0.1472 | 0.1656 | |

| 0.0255 | 0.1403 | 5.634 | 0.2689 | 0.6043 | |

| 0.0944 | 13.79 | 5.048 | 1.667 | 5.500 | |

| −0.1232 | 13.31 | 3.131 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| −0.7728 | −0.3057 | −0.2598 | 2.988 | 7.354 | |

| 9.084 | 1.886 | 1.779 | 13.77 | 62.98 | |

| Variable | Panel B: Conventional FTSE100 Index | ||||

| −0.0759 | 14.35 | 5.283 | 0.1472 | 0.1654 | |

| 0.7187 | 0.1342 | 0.2318 | 0.2676 | 0.6010 | |

| 2.261 | 14.53 | 1.884 | 1.667 | 5.500 | |

| −3.195 | 14.10 | 1.238 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| −0.9750 | 0.0226 | 0.1929 | 2.989 | 7.367 | |

| 6.992 | 1.492 | 1.277 | 13.77 | 62.98 | |

3. Data and methodology

This study investigates whether contagious infectious diseases affect stock market outcomes. The data adopted includes daily prices of companies listed on the UK Dow Jones Islamic stock market index and its counterpart FTSE100 index during the period from January 20 to May 20, 2020. The data is obtained from Bloomberg and, in addition to stock prices, includes market capitalization and market-to-book ratio. The study also used the number of daily active confirmed cases (NCOVGBCC) and daily cases of death (NCOVGBDC) from COVID-19 in the UK from the same source over the same period, which are available on a daily basis. Fig. 1 shows the cumulative average daily returns for the UK Dow Jones Islamic stock market index. The figure suggests that cumulative returns are slightly impacted by COVID-19 in terms of the daily active confirmed cases and the daily confirmed deaths caused by COVID-19, and that market returns are mostly uninterrupted as the growth of both daily active cases and confirmed deaths starts to decline. The data of ten sector groupings (Communications (COM), Consumer Discretionary (COND), Energy (ENG), Financial (FIN), Health Care (HC), Materials (MAT), Consumer Staples (CONS), Industrial (INDUS), Technology (TEC) and Utilities (UT)) are also obtained from Bloomberg.

A key and important step in event study methodology/process is to identify the actual day of the event (Binder, 1998). Subsequently, Henderson Jr (1990) and Dyckman et al. (1984) described this step as problematic and time consuming. Equipped with this claim and due to the fact that the peak of the event associated with COVID-19 pandemic is not the start date, but rather lasts for several days, the study hence adopts and follows the classical event study methodologies. Moreover, Kao and Chiang (1999) and Hsiao (1986) have stated and discussed the benefits of using panel data models; claiming that panel data regression reduces estimation bias and multicollinearity, controls for individual heterogeneity, and identifies the time-varying relationship between dependent and independent variables. Subsequently, the analysis in this study performs panel testing to investigate the performance of Shariah-compliant UK Dow Jones market index to capture the dynamic behavior of stock returns at economy and industry levels. The regression model employed in this study has the following functional form:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where is return index at different time periods, is daily growth in total confirmed cases, is the daily growth in total cases of death caused by COVID-19, is the natural logarithm of daily market capitalization, is the daily market-to-book ratio, and is the error or disturbance term.

For the UK sector groupings, the regression model employed in this study has the following functional form:

| (3) |

where is sector returns at different time periods, symbolizes a vector of explanatory variables at different time periods associated with each sector grouping, and is the error or disturbance term.

4. Empirical findings

The analysis begins with the descriptive analysis. Table 3 presents the stock market return characteristics and summary statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, Kurtosis and Skewness) pertaining to Islamic index and its mainstream conventional UK counterpart. In Table 3, panels and show that both conventional and non-conventional stock return indices have negative mean returns, indicating a clear impact of COVID-19 on the performance of the two indices. However, the faith-based stock market index is less impacted by COVID-19 ( 0.15%) than the peer ( 7.6%). Similarly, the skewness which measures the asymmetry of the probability distributions shows that both indexes are negatively skewed, indicating the higher probability of decrease in returns. These statistics suggest that on average the ethical stock market index (−0.15%) out-perform their conventional peer (−7.593%) during the pandemic period. Also, the conventional index is on average riskier (SD 71.87%) than the ethical stock market index (SD 2.5%.).

Table 4 shows the correlation matrix of the data. The highest negative correlation is between daily stock returns, with both the daily growth in total confirmed cases and the daily growth in total cases of death caused by COVID-19. The findings suggest that the faith-based stock market index performs and survives better than its UK conventional peer during the pandemic period. The overall results are not surprising, but provide quantitative evidence that the indices perform as might be anticipated, and offer some confidence to further examine these variables in more detail. This also clear from Fig. 1.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix.

| Panel A: Correlation matrix --- DJIUK |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.000 | |||||

| 0.0539 | 1.000 | ||||

| 0.0531 | 0.6088 | 0.000 | |||

| −0.1274 | −0.2605 | −0.2584 | 1.000 | ||

| −0.2327 | −0.3431 | −0.3439 | 0.4349 | 1.000 | |

| Panel B: Correlation matrix — FTSE100 | |||||

| 1.000 | |||||

| 0.0111 | 1.000 | ||||

| 0.0042 | −0.0581 | .000 | |||

| −0.0238 | −0.0311 | −0.0120 | 1.000 | ||

| −0.0169 | −0.0470 | −0.0159 | 0.4370 | 1.000 | |

In an attempt to ascertain the adequacy of the descriptive statistics to explain investment performance during the outbreak of the COVID-19, the performance of Islamic Dow Jones and conventional indexes are tested using panel regression. While Table 5 summarizes the estimates of faith-based investments associated with the daily growth in total confirmed and death cases, Table 6 presents the estimates of the conventional FTSE100 associated with the daily growth in total confirmed and death cases. Overall, these findings suggest that: (i) the stock returns of the conventional index are significantly negatively related to both daily growth in total confirmed cases and daily growth in total cases of death caused by COVID-19; (ii) faith-based investments/index are less exposed to the outbreak of COVID-19 than its conventional peer. These results are broadly comparable to the findings of Trichilli et al. (2020a) and Rejeb and Arfaoui (2019) who found that Islamic indices are partially immune from speculative shocks to global financial services. Furthermore, they indicated that the ethical stock market indices perform much better during calm periods and moderately better during times of crisis; and Islamic asset allocation is safer during pandemics and economic periods and distress. These findings are also in line with another group of studies that have found significant diversification benefits from investing in Islamic assets (Hakim and Rashidian, 2002, Guyot, 2011). This implies that Islamic indices are less risky than their peers, and this evidence is attributable to the profit and loss sharing principle in Islamic finance.3

Table 5.

Panel regression estimates: Faith-based investments.

| Panel A: Daily growth in total confirmed cases --- DJIUK |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| 0.0032 | −1.053 | −2.363 | |

| (0.0057) | (1.056) | (8.379) | |

| −0.0205 | −0.0013 | −0.0022 | |

| (0.0233) | (0.0302) | (0.0310) | |

| 0.0780 | 0.1828 | ||

| (0.0679) | (0.6696) | ||

| −0.0273 | |||

| (0.1730) | |||

| Panel B: Daily growth in total death cases — DJIUK | |||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| 0.0026 | −0.7761 | −2.766 | |

| (0.0047) | (0.8471) | (8.239) | |

| −0.0085 | −0.0068 | −0.0070* | |

| (0.0057) | (0.0060) | (0.0011) | |

| 0.0576 | 0.2166 | ||

| (0.0627) | (0.6581) | ||

| −0.0409 | |||

| (0.1686) | |||

*Significant at the 0.10 level.

Table 6.

Panel regression estimates: Conventional investments.

| Panel A: Daily growth in total confirmed cases --- FTSE100 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| 0.0407 | 0.0442 | 0.0479 | |

| (0.0105) | (0.0848) | (0.0852) | |

| −0.0798** | −0.0786** | −0.0784** | |

| (0.0341) | (0.0343) | (0.0344) | |

| 0.0281 | 0.0213 | ||

| (0.0207) | (0.0208) | ||

| 0.0003 | |||

| (0.0007) | |||

| Panel B: Daily growth in total death cases — FTSE100 | |||

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

| 0.0331 | 0.0514 | 0.0552 | |

| (0.0095) | (0.0847) | (0.0851) | |

| −0.0252*** | −0.0245*** | −0.0244*** | |

| (0.0007) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | |

| 0.0090 | 0.0093 | ||

| (0.0089) | (0.0090) | ||

| 0.0003 | |||

| (0.0007) | |||

***Significant at the 0.01 level **significant at the 0.05 level.

Next, the performance of investments and UK stock market index during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak for ten sector groupings (COM, COND, ENG, FIN, HC, MAT, CONS, INDUS, TEC, UT) introduced by Bloomberg (sector grouping classification, 2020). This is motivated by the findings of a number of researchers (Kizys et al., 2020, Chen et al., 2007) who demonstrate that a few sector groupings such as information technology, food processing, beverages, air transportation, and hotels among others are vulnerable and mostly impacted by pandemic diseases/outbreaks. Table 7 reports the estimates of panel data associated with ten sector groupings dummy variables that take the value one if stock is listed in that respective sector, and zero otherwise. The findings show that stock returns of the information technology sector grouping positively benefited from coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, and performed significantly better than the market. On the other hand, consumer discretionary sector (COND) which includes air and other transportation, beverages, tourism and leisure, consumer services appear to be the significant sectors that have been adversely influenced by the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak.

Table 7.

Panel regression estimates with sector groupings.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0537 | 0.0656 | 0.0871 | 0.1052 | 0.0469 | −0.0629 | 0.0567 | 0.0651 | 0.0694 | 0.0670 | ||

| (0.0856) | (0.0849) | (0.0913) | (0.0852) | (0.0818) | (0.0850) | (0.0851) | (0.0852) | (0.0851) | (0.0851) | ||

| 0.0093 | 0.0095 | 0.0124 | 0.0133 | 0.0078 | 0.0098 | 0.0092 | 0.0099 | 0.0105 | 0.0100 | ||

| (0.0090) | (0.0090) | (0.0098) | (0.0090) | (0.0086) | (0.0089 ) | (0.0090) | (0.009) | (0.0091) | (0.0090) | ||

| 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | ||

| (0.0007) | (0.0007) | (0.0007) | (0.0007) | (0.0006 ) | (0.0006) | (0.0007) | (0.0006) | (0.0007) | (0.0006) | ||

| −0.0246 | |||||||||||

| (0.0219) | |||||||||||

| 0.0029*** | |||||||||||

| (0.0006) | |||||||||||

| −0.0373 | |||||||||||

| (0.0572) | |||||||||||

| 0.2402*** | |||||||||||

| (0.0527) | |||||||||||

| −0.0194 | |||||||||||

| (0.0338) | |||||||||||

| −0.0199 | |||||||||||

| (0.0352) | |||||||||||

| −0.0463 | |||||||||||

| (0.0342) | |||||||||||

| −0.0029 | |||||||||||

| (0.0288) | |||||||||||

| −0.0227 | |||||||||||

| (0.0414) | |||||||||||

| 0.0087 | |||||||||||

| (0.0412) |

5. Conclusion

This paper investigated the Shariah-compliant stock market indices reactions to the increased uncertainty due to COVID-19 expansion as compared to the FTSE100 conventional index. The findings suggest a strong and statistically significant relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and the performance of the conventional stock market index. Such negative impact is over and above that of the Shariah-compliant stock market index. In addition, this paper analyzed the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the performance of ten UK sector groupings. Results show that stock returns of the information technology sector performed significantly better than the market; whereas stock returns of the consumer discretionary sector performed significantly worse than the market during the COVID-19 outbreak.

There are a number of implications for research and practice from these results. Firstly, the study offers insights to empower and enhance the strengthening of the policy measures required for policy makers in stock markets and economies. Secondly, from a broader perspective, the research and findings provide support for the existence of a risk-aversion channel of pandemic spread in the stock market. Comparing the conventional stock market indices with faith-based sources of stock investments and trading may provide insights into the globalization of such economic, trade and financial reforms. Finally, the findings could also be of interest to policy makers who are continually adopting regulations in attempts to curb possible presumable conflicts of interest in many other stock markets outside the UK. While investors can reconcile faith with finance, the financial market authorities could revise their regulations and legislation to enable banks and markets to include these types of products, and to propose new products with similar characteristics.

While this study helps contribute to existing literature on the COVID-19 pandemic, it also opens up avenues for further research. The most feasible immediate expansion would be to include other faith-based indexes (Christian and Jewish) omitted in this study due to the current unavailability of the data. In addition, future research should also look into Islamic sub-indices and include other institutions that are Islamic subsidiaries of conventional banks.

Footnotes

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC-Index performance based on the total returns in USD.

Main differences between faith-based and conventional investments are shown in Table 2.

In the Islamic mode of finance, the Arabic word Musharakah means “shirka” or sharing. Equipped with the profit and loss sharing principle, the main goal of investors is to maximize returns, which in turn maximizes the other party’s return.

References

- Abduh M. Volatility of Malaysian conventional and Islamic indices: does financial crisis matter? J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2020;11(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Alkheil A., Khan W.A., Parikh B. Risk-reward trade-off and volatility performance of islamic versus conventional stock indices: Global evidence. Rev. Pac. Basin Financ. Mark. Policies. 2020;23(01) [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F., Seyyed F.J., Ashfaq H. Managing a Shariah-compliant capital protected fund through turbulent times. Asian J. Manage. Cases. 2020;17(1_suppl):S32–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H., Elsayed A.H. Are islamic and conventional capital markets decoupled? Evidence from stock and bonds/sukuk markets in Malaysia. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2019;74:56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Akguc S., Al Rahahleh N. Shariah compliance and investment behavior: Evidence from GCC countries. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade. 2020:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Awadhi A.M., Al-Saifi K., Al-Awadhi A., Alhamadi S. Death and contagious infectious diseases: Impact of the COVID-19 virus on stock market returns. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2020;27(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khazali O., Lean H.H., Samet A. Do Islamic stock indexes outperform conventional stock indexes? A stochastic dominance approach. Pac.-Basin Finance J. 2014;28:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zoubi H.A., Maghyereh A.I. The relative risk performance of Islamic finance: a new guide to less risky investments. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Finance. 2007;10(02):235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Alam I. Interacting with Muslim customers for new service development in a non-Muslim majority country. J. Islam. Mark. 2019;10(4):1017–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Alam I., Seifzadeh P. Marketing Islamic financial services: A review, critique, and agenda for future research. J. Risk Financ. Manage. 2020;13(1):12. [Google Scholar]

- Albaity M., Ahmad R. Performance of Syariah and composite indices: Evidence from Bursa Malaysia. Asian Acad. Manage. J. Account. Finance. 2008;4(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Albulescu C. 2020. Coronavirus and financial volatility: 40 days of fasting and fear. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.04005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro L., Chari A., Greenland A.N., Schott P.K. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Aggregate and Firm-Level Stock Returns During Pandemics, in Real Time: Technical report. Working Paper No. w26950. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi K.O., Hariri M.M. Content analysis of Shariah-compliant investment equity funds in KSA: Does social justice matter? Int. J. Bus. Manage. 2020;15(6):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaifi K., Elnahass M., Salama A. Carbon disclosure and financial performance: UK environmental policy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020;29(2):711–726. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei D., Hasler M. Investor attention and stock market volatility. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015;28(1):33–72. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum S. Impact of market anomalies on stock exchange: a comparative study of KSE and PSX. Future Bus. J. 2020;6(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis N., Darby J. Forecasting volatility in developing countries’ nominal exchange returns. Appl. Financial Econ. 2013;23(21):1675–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Anwaar M. Impact of firms performance on stock returns (evidence from listed companies of FTSE100 index London, UK. Global J. Manage. Bus. Res. 2016;18(6):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Atta-Alla M.N. Using storytelling to integrate faith and learning: The lived experience of Christian ESL teachers. Int. Christ. Community Teach. Educ. J. 2012;7(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- Balcılar M., Demirer R., Hammoudeh S. Global risk exposures and industry diversification with shariah-compliant equity sectors. Pac.-Basin Finance J. 2015;35:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Bash A., Alsaifi K. Fear from uncertainty: An event study of khashoggi and stock market returns. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2019;23:54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bauckloh T., Heiden S., Klein C., Zwergel B. New evidence on the impact of the English national soccer team on the FTSE100. Finance Res. Lett. 2019;28:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R., Koedijk K., Otten R. International evidence on ethical mutual fund performance and investment style. J. Bank. Financ. 2005;29(7):1751–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Becchetti L., Ciciretti R., Dalò A., Herzel S. Socially responsible and conventional investment funds: performance comparison and the global financial crisis. Appl. Econ. 2015;47(25):2541–2562. [Google Scholar]

- Binder J. The event study methodology since 1969. Rev. Quant. Finance Account. 1998;11(2):111–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev T., Li J., Xue Y. Volume, volatility, and public news announcements. Rev. Econom. Stud. 2018;85(4):2005–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Boubaker H., Rezgui H. Co-movement between some commodities and the Dow Jones Islamic index: A Wavelet analysis. Econ. Bull. 2020;40(1):574–586. [Google Scholar]

- Buklemishev O.V. Coronavirus crisis and its effects on the economy. Popul. Econ. 2020;4(2):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson-Szlezak P., Reeves M., Swartz P. What coronavirus could mean for the global economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020;289:173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Carter P., Anderson M., Mossialos E. Health system, public health, and economic implications of managing COVID-19 from a cardiovascular perspective. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41(27):2516–2518. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro E., Hassan M.K., Rubio J.F., Halim Z.A. Relative performance of religious and ethical investment funds. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2020;11(6):1227–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Charles A., Darné O., Kim J.H. Adaptive markets hypothesis for islamic stock indices: Evidence from Dow Jones size and sector-indices. Int. Econ. 2017;151:100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Charles A., Darné O., Pop A. Risk and ethical investment: Empirical evidence from Dow Jones Islamic indexes. Res. Int. Bus. Finance. 2015;35:33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Cheung C.L., Tai H., Zhao P., Chan J.F., Cheng V.C., Chan K.-H., Yuen K.-Y. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza a pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, Hong Kong, China. Emerg. Infec. Dis. 2009;15(12):1970. doi: 10.3201/eid1512.091057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Chiang T.C. Empirical investigation of changes in policy uncertainty on stock returns–Evidence from China’s market. Res. Int. Bus. Finance. 2020;53(10) [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.-H., Jang S.S., Kim W.G. The impact of the SARS outbreak on Taiwanese hotel stock performance: an event-study approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007;26(1):200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry T., Papadimitriou F.I., Shabi S. Stock market volatility and business cycle: Evidence from linear and nonlinear causality tests. J. Bank. Financ. 2016;66:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chronopoulos D.K., Papadimitriou F.I., Vlastakis N. Information demand and stock return predictability. J. Int. Money Finance. 2018;80:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Climent F., Mollá P., Soriano P. The investment performance of US Islamic mutual funds. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3530. [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Larkin C., Lucey B. The contagion effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from gold and Cryptocurrencies. Finance Res. Lett. 2020;35(1) doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Z., Engelberg J., Gao P. The sum of all FEARS investor sentiment and asset prices. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015;28(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Davies R.B., Studnicka Z. The heterogeneous impact of Brexit: Early indications from the FTSE. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018;110:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Demirer R., Gupta R., Lv Z., Wong W.-K. Equity return dispersion and stock market volatility: evidence from multivariate linear and nonlinear causality tests. Sustainability. 2019;11(2):351. [Google Scholar]

- Derigs U., Marzban S. Review and analysis of current Shariah-compliant equity screening practices. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance Manage. 2008;1(4):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Dhai R. A comparison of the performance of the FTSE South Africa islamic index to the conventional market (JSE) in South Africa. South Afr. J. Account. Res. 2015;29(2):101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dhrymes P.J. Portfolio Construction, Measurement, and Efficiency. Springer; 2017. Portfolio theory: origins, Markowitz and CAPM based selection; pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C.J., Scott S. What caused the black death? Postgrad. Med. J. 2005;81(955):315–320. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.024075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand R.B., Laing E., Ngo M.T. The disciplinary role of leverage: evidence from east asian cross-border acquirers’ returns. Finance Res. Lett. 2016;18:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury D., Gärling T., Gamble A., Klass V. How emotions influence behavior in financial markets: a conceptual analysis and emotion-based account of buy-sell preferences. Eur. J. Finance. 2020:in press 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dyckman T., Philbrick D., Stephan J. A comparison of event study methodologies using daily stock returns: A simulation approach. J. Account. Res. 1984;22(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- El Khamlichi A., Sarkar K., Arouri M., Teulon F. Are islamic equity indices more efficient than their conventional counterparts? Evidence from major global index families. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2014;30(4):1137–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq O., Alahkam A. Performance of shariah-compliant firms and non-shariah-compliant firms in the MENA region. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2016;7(4):268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. 2020. Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy. Available at SSRN 3557504. [Google Scholar]

- Ftiti Z., Hadhri S. Can economic policy uncertainty, oil prices, and investor sentiment predict Islamic stock returns? A multi-scale perspective. Pac.-Basin Finance J. 2019;53:40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Wright D., Blazenko G. Ethical investing has no portfolio performance cost. Res. Int. Bus. Finance. 2020;52 [Google Scholar]

- Girard E.C., Hassan M.K. Is there a cost to faith-based investing: Evidence from FTSE Islamic indices. J. Invest. 2008;17(4):112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild B., Hickman P., Robinson D. Unpopular housing in England in conditions of low demand: coping with a diversity of problems and policy measures. Town Plan. Rev. 2002;73(4):373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Gormsen N.J., Koijen R.S. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper; 2020. Coronavirus: Impact on Stock Prices and Growth Expectations. (2020–22) [Google Scholar]

- Guyot A. Efficiency and dynamics of islamic investment: evidence of geopolitical effects on Dow Jones islamic market indexes. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade. 2011;47(6):24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad H.B., Mezghani I., Al Dohaiman M. Common shocks, common transmission mechanisms and time-varying connectedness among Dow Jones islamic stock market indices and global risk factors. Econ. Syst. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Hakim S., Rashidian M. 9th Economic Research Forum Annual Conference in Sharjah, UAE. 2002. Risk and return of islamic stock market indexes; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoudeh S., Mensi W., Reboredo J.C., Nguyen D.K. Dynamic dependence of the global Islamic equity index with global conventional equity market indices and risk factors. Pac.-Basin Finance J. 2014;30:189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan D., Abu M. Co-movement and volatility transmission between Islamic and conventional equity index in Bangladesh. Islam. Econ. Stud. 2019;26(2):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan K.M., Girard E. Faith-based ethical investing: The case of Dow Jones Islamic indexes. Islam. Econ. Stud. 2010;17(2):21–57. [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Liu J., Wang S., Yu J. The impact of COVID-19 on stock markets. Econ. Political Stud. 2020;8(3):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Jr G.V. Problems and solutions in conducting event studies. J. Risk Insurance. 1990;57(2):282–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.S.F., Rahman N.A.A., Yusuf N.H.M., Zamzamin Z. Performance of global islamic versus conventional share indices: international evidence. Pac.-Basin Finance J. 2014;28:110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hoepner A.G., Rammal H.G., Rezec M. Islamic mutual funds’ financial performance and international investment style: evidence from 20 countries. Eur. J. Finance. 2011;17(9–10):829–850. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 1986. Analysis of Panel Data. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain H.I., Grabara J., Razimi M.S.A., Sharif S.P. Sustainability of leverage levels in response to shocks in equity prices: Islamic finance as a socially responsible investment. Sustainability. 2019;11(12):3260. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein K., Omran M. Ethical investment revisited: evidence from Dow Jones Islamic indexes. J. Invest. 2005;14(3):105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ichev R., Marinč M. Stock prices and geographic proximity of information: Evidence from the Ebola outbreak. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2018;56:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawadi F., Jawadi N., Cheffou A.I. A statistical analysis of uncertainty for conventional and ethical stock indexes. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2019;74:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jawadi F., Jawadi N., Louhichi W. Conventional and Islamic stock price performance: An empirical investigation. Int. Econ. 2014;137:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kalimullina M. Islamic finance in Russia: A market review and the legal environment. Global Finance J. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.gfj.2020.100534. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao C., Chiang M.-H. 1999. On the estimation and inference of a cointegrated regression in panel data. Available at SSRN 1807931. [Google Scholar]

- Kizys R., Tzouvanas P., Donadelli M. 2020. From COVID-19 herd immunity to investor herding in international stock markets: The role of government and regulatory restrictions. Available at SSRN 3597354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski O., Śpiewanowski P. Stock market response to potash mine disasters. J. Commod. Mark. 2020 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Landi G., Sciarelli M. Towards a more ethical market: The impact of ESG rating on corporate financial performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019;15(1):11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lekhraj Rampal M., Seng L.B. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Med. J. Malays. 2020;75(2):95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Manzoor A., Wang C., Zhang L., Manzoor Z. The COVID-19 outbreak and affected countries stock markets response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(8):2800. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Peng G., Hu L., Dong J., Zhang Q. Using Google trends and Baidu index to analyze the impacts of disaster events on company stock prices. Ind. Manage. Data Syst. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Masih M., Kamil N.K., Bacha O.I. Issues in Islamic equities: A literature survey. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade. 2018;54(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mei J., Guo L. Political uncertainty, financial crisis and market volatility. Eur. Financial Manag. 2004;10(4):639–657. [Google Scholar]

- Miniaoui H., Sayani H., Chaibi A. The impact of financial crisis on Islamic and conventional indices of the GCC countries. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2015;31(2):357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Mogaji E. Financial vulnerability during a pandemic: Insights for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Res. Agenda Work. Pap. 2020;2020(5):57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkinen J., Peltomäki J. Crash fears and stock market effects: evidence from web searches and printed news articles. J. Behav. Finance. 2020;21(2):117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Onali E. 2020. Covid-19 and stock market volatility. Available at SSRN 3571453. [Google Scholar]

- Papadamou S., Fassas A., Kenourgios D., Dimitriou D. 2020. Direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 pandemic on implied stock market volatility: Evidence from panel data analysis; pp. 193–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papava V., Charaia V. GFSIS, Expert Opinion (136) 2020. The coronomic crisis and some challenges for the Georgian economy. [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Vetter P., Guitart C., Lotfinejad N., Pittet D. Understanding the emerging coronavirus: what it means for health security and infection prevention. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;104(4):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboredo J.C., Ugolini A. The impact of twitter sentiment on renewable energy stocks. Energy Econ. 2018;76:153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman M.U., Asghar N., Kang S.H. Do Islamic indices provide diversification to bitcoin? A time-varying copulas and value at risk application. Pac.-Basin Finance J. 2020;61 [Google Scholar]

- Rejeb A.B., Arfaoui M. Do Islamic stock indexes outperform conventional stock indexes? A state space modeling approach. Eur. J. Manage. Bus. Econ. 2019;28(3):301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rifqi, M., The cost of Sharia investing: Comparative empirical study in Indonesian stock market. J. Emerg. Econ. Islam. Res. 4 (4) 1–13.

- Sadeghi M. Financial performance of Shariah-compliant investment: evidence from Malaysian stock market. Int. Res. J. Finance Econ. 2008;20(8):15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Seyyed F.J., Shehzad C.T., Ashfaq H. Millat tractors limited: A Shariah-compliant investment opportunity. Asian J. Manage. Cases. 2020;17(1_suppl):S61–S77. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh S.A., Ismail A.G., Ismail M.A. Research in Corporate and Shari’ah Governance in the Muslim World: Theory and Practice. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2019. Shari’ah compliance governance for Islamic investments and their effects on performance’; pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin A. Are Dow Jones islamic equity indices exposed to interest rate risk? Econ. Model. 2014;39:273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M. Ethical Dow Jones indexes and investment performance: international evidence. Invest. Manage. Financ. Innov. 2016;(13, Iss. 2 (contin1)):206–225. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M., Erkol C.T. Sukuk and conventional bonds: shareholder wealth perspective. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2017;8(4):347–374. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M., Hussnain S. Family takaful in developing countries: the case of Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance Manage. 2017;10(3):371–399. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir M., Ibrahim S. The performance of Shariah-compliant companies during and after the recession period–evidence from companies listed on the FTSE all world index. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2020;11(3):573–587. [Google Scholar]

- Trabelsi N. Dynamic and frequency connectedness across Islamic stock indexes, bonds, crude oil and gold. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance Manage. 2019;12(3):306–321. [Google Scholar]

- Trabelsi L., Bahloul S., Mathlouthi F. Performance analysis of Islamic and conventional portfolios: The emerging markets case. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2020;20(1):48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Trichilli Y., Abbes M.B., Masmoudi A. Islamic and conventional portfolios optimization under investor sentiment states: Bayesian vs Markowitz portfolio analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Finance. 2020;51 [Google Scholar]

- Trichilli Y., Abbes M.B., Masmoudi A. Predicting the effect of Googling investor sentiment on islamic stock market returns. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance Manage. 2020;13(2):165–193. [Google Scholar]

- Umar Z., Kenourgios D., Naeem M., Abdulrahman K., Al Hazaa S. The inflation hedging capacity of Islamic and conventional equities. J. Econ. Stud. 2020 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Umer U.M., Sevil T., Sevil G. Forecasting performance of smooth transition autoregressive (STAR) model on travel and leisure stock index. J. Finance Data Sci. 2019;5(1):12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vasisht S. Performance analysis of selected shariah indices of the world. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manage. Appl. Sci. 2017;5(4) [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wei Y., Wu C., Yin L. Oil and the short-term predictability of stock return volatility. J. Empir. Financ. 2018;47:90–104. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019, Vol. 2019; p. 2633. [Google Scholar]

- Widyanata F., Bashir A. The causality between Indonesian Sharia stock index and market capitalization: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Ekon. Studi Pembang. 2020;12(1):45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Lodorfos G., Dean A., Gioulmpaxiotis G. The market performance of socially responsible investment during periods of the economic cycle–illustrated using the case of FTSE. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2017;38(2):238–251. [Google Scholar]

- Zandi G., Haseeb M., Widokarti J.R., Ahmed U., Chankoson T. Towards crises prevention: Factors affecting lending behaviour. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues. 2019;9(1):309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Zaremba A., Kizys R., Aharon D.Y., Demir E. Infected markets: Novel Coronavirus, government interventions, and stock return volatility around the globe. Finance Res. Lett. 2020;35 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Hu M., Ji Q. Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Finance Res. Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Liu Q., Wang Y., Wei Y., Wei G. Which fear index matters for predicting US stock market volatilities: Text-counts or option based measurement? Physica A. 2019;536 [Google Scholar]