Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is essential for diagnosis of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) are recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the current standard method to detect SARS-CoV-2 in suspected patients.1 However, collection of an NPS or oropharyngeal swab (OPS) can be technically difficult, uncomfortable for patients, may induce sneezing or coughing, and expose those nearby to aerosolised SARS-CoV-2).2

We postulate that alternative easier-to-sample swabs such as those from the nose (NS) or cheek (CS) may be equally sensitive in acute COVID-19 cases, and can be effectively taken by patients themselves. In addition, longitudinal analysis of serial samples collected contemporaneously from multiple upper respiratory tract (URT) sites, from the same patient, has not been well described. Here, we performed a prospective longitudinal analysis of three healthcare worker volunteers with differing clinical severities of acute COVID-19.

Shortly after a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 using the local diagnostic AusDiagnostics (Ausdiagnostics UK Ltd., Chesham, England) SARS-CoV-2 PCR test,3 each participant volunteered to provide serial self-collected swabs from the nasopharynx (NPS, 1 swab), just inside the soft part of the nose (NS, 1 swab), the oropharynx (OPS, 1 swab), inside the cheek (CS, 1 swab). In addition, we also decided to check for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the conjunctiva (CJS, 1 swab for both eyes). All of these swabs were taken at the same time-point, on a daily basis - or as frequently as was practical and tolerable - until all the SARS-CoV-2 viral loads became undetectable. Thus, each patient collected up to 5 separate swabs on a daily basis for this study.

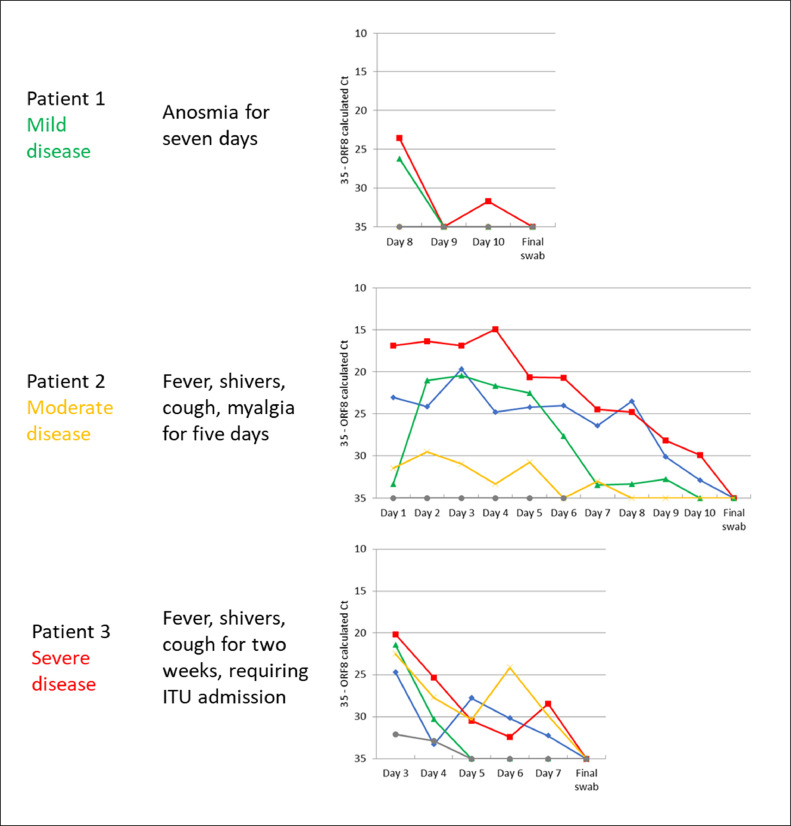

All three participants (hereafter referred to individually as ‘Patient’ 1, 2, or 3) became symptomatic with confirmed COVID-19 during the week of 12th April 2020. Patient 1 had mild COVID-19, complaining of a 7-day history of anosmia only; Patient 2 had moderate COVID-19, with a 5-day history of fevers, shivers, dry cough and myalgia; Patient 3 had severe COVID-19, presenting with a 2-week history of fevers, shivers and a productive cough that required supplemental oxygen therapy, and eventual admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) during the second week, after which no further swabs were taken. Final follow-up swabs were performed by the participants on 5th May 2020, two weeks after symptom onset for all participants.

From 17th April to 5th May 2020, a total of 105 swabs were collected from three participants (Fig. 1 ). Patient 1 (mild COVID-19) provided a total of four days of swabs (20 swabs) from Day 8 days post-symptom onset; Patient 2 (moderate COVID-19) provided a total of 11 days of swabs (55 swabs) from Day 1 post-symptom onset; Patient 3 (severe COVID-19) provided a total of 6 days of swabs (30 swabs) from Day 3 post-symptom onset. All three participants were PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2 on the final swabs taken on 5th May 2020.

Fig. 1.

Relative SARS-CoV-2 viral loads indicated by Aus Diagnostics ORF8 multiplex-tandem RT-PCR calculated cycle threshold (Ct) values (inverted y-axis) of Patient s 1–3 with differing severities of COVID-19. Samples which did not amplify have been given a nominal value of 35 (equivalent to the maximum calculated Ct for this assay). The ‘final’ (PCR negative) swab was taken 14 days post-illness onset for all Patients. Corresponding sample types according to sampling site (as discussed in the main text): Red squares: nasopharynx – nasopharyngeal swab (NPS); green triangles: nose – nasal swab (NS); blue diamonds: oropharynx – oropharyngeal swab (OPS); yellow crosses: cheek – cheek swab (CS); grey circles: conjunctiva – conjunctival swab (CJS). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Patient 1 (mild COVID-19) only had positive PCR results from the NPS and NS, with negative PCR results from the NS after day 8. Patient 2 had positive PCR results from all sites except for the conjunctiva, with the lowest cycle threshold (Ct) value (i.e. the highest viral load) in the NPS, followed by the OPS, NS and CS. Patient 3 had positive PCR values from all sites; with the lowest Ct value (highest viral load) in the NPS followed by NS, CS, OPS and CJS.

For all three participants, Ct values appeared to increase (i.e. the viral loads decreased) over time. For Patient 1 (mild COVID-19), the virus was only detected in the NPS and NS from Day 8 onwards, with some fluctuation in the detectability of the virus in the NPS. For Patient 2 (moderate COVID-19), the Ct values of the NPS, OPS and NS also increased over time, with some fluctuation in the detectability of the virus in the CS. For Patient 3 (severe COVID-19), the NPS, OPS and CS Ct values increased over time, demonstrating decreasing viral loads.

Our small longitudinal study cohort demonstrated several findings. Firstly, the most symptomatic case, Patient 3 was most likely to be viremic at multiple sites in the URT, as reported elsewhere.4 Secondly, self-swabbing from these various URT sites is an effective and sensitive way to collect diagnostic samples, as found elsewhere.5 Note that only one out of these three cases, Patient 3 who did not exhibit overt conjunctivitis, exhibited detectable virus from the conjunctiva within the first 5 days of illness. Patient 1′s first swab was only taken on Day 8 post-illness onset, so it is possible that any virus present earlier in conjunctival fluids may have been missed. However, this lower detection rate for conjunctival swabs (with or without overt conjunctivitis) is consistent with previous reports.6 Thirdly, the relative SARS-CoV-2 viral loads from the URT decreased with time in the 1–2 weeks post-COVID-19 symptom onset, regardless of disease severity. This has been shown elsewhere,7 though this is not always the case.8

From this small longitudinal cohort study on serially collected samples in acute COVID-19 cases of differing severity, we conclude that for symptomatic patients, it is difficult to obtain a ‘false negative’ result on NPS, OPS, NS or CS samples, if sampled early (within 5 days) post-symptom onset, even if the swab was ‘poorly’ taken. Despite a previous meta-analysis showing that sputum testing is possibly more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing,9 other studies have shown that self-sampling from various URT sites performed satisfactorily for the diagnosis of acute COVID-19.5 Sputum testing is not standard in many virology labs due to long-recognised problems related to its viscosity and risks of PCR inhibition,10 and not all COVID-19 patients will have a productive cough.

Therefore, we further confirm that early (within 5 days of symptom onset), self-swabbed NPS, OPS, NS or CS samples for SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic testing in acute COVID-19 cases is a sensitive, practical approach, which reduces patient discomfort (as self-swabbing can be controlled) and minimises virus exposure to healthcare workers.

References

- 1.WHO Laboratory testing of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases. 2020 https://www.who.int/publications-detail/laboratory-testing-for-2019-novel-coronavirus-in-suspected-human-cases-20200117 (Accessed 1st December) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marty F.M., Chen K., Verrill K.A. How to obtain a nasopharyngeal swab specimen. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):e76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm2010260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird P., Badhwar V., Fallon K., Kwok K.O., Tang J.W. High SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in respiratory staff nurses and correlation of COVID-19 symptom patterns with PCR positivity and relative viral loads. J Infect. Sep 2020;81(3):452–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tu Y.P., Jennings R., Hart B. Swabs collected by patients or health care workers for SARS-CoV-2 testing. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):494–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2016321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Güemes-Villahoz N., Burgos-Blasco B., Arribi-Vilela A. Detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in conjunctival secretions: is it a valuable diagnostic method of COVID-19? J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26219. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 24] 10.1002/jmv.26219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi A., Esmaeilzadeh E., Li Y., Bosch R.J., Li J.Z. SARS-CoV-2 detection in different respiratory sites: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EBioMedicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102903. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 18] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong J.H., Kim K.H., Jeong S.H., Park J.W., Lee S.M., Seo Y.H. Comparison of sputum and nasopharyngeal swabs for detection of respiratory viruses. J Med Virol. Dec 2014;86(12):2122–2127. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]