Abstract

Purpose:

Rhabdoid tumors (RTs) are devastating pediatric cancers in need of improved therapies. We sought to identify small molecules that exhibit in vitro and in vivo efficacy against preclinical models of RT.

Experimental Design:

We screened eight RT cell lines with 481 small molecules and compared their sensitivity to that of 879 other cancer cell lines. Genome-scale CRISPR–Cas9 inactivation screens in RTs were analyzed to confirm target vulnerabilities. Gene expression and CRISPR–Cas9 data were queried across cell lines and primary RTs to discover biomarkers of small-molecule sensitivity. Molecular correlates were validated by manipulating gene expression. Subcutaneous RT xenografts were treated with the most effective drug to confirm in vitro results.

Results:

Small-molecule screening identified the protein-translation inhibitor homoharringtonine (HHT), an FDA-approved treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), as the sole drug to which all RT cell lines were selectively sensitive. Validation studies confirmed the sensitivity of RTs to HHT was comparable to that of CML cell lines. Low expression of the antiapoptotic gene BCL2L1, which encodes Bcl-XL, was the strongest predictor of HHT sensitivity, and HHT treatment consistently depleted Mcl-1, the synthetic-lethal antiapoptotic partner of Bcl-XL. RT cell lines and primary-tumor samples expressed low BCL2L1, and overexpression of BCL2L1 induced resistance to HHT in RT cells. Furthermore, HHT treatment inhibited RT cell line and patient derived xenograft growth in vivo.

Conclusions:

RT cell lines and xenografts are highly sensitive to HHT, at least partially due to their low expression of BCL2L1. HHT may have therapeutic potential against RTs.

Keywords: Rhabdoid, SWI/SNF, homoharringtonine, omacetaxine

Introduction

Rhabdoid tumors (RTs) are devastating pediatric cancers with poor prognoses, despite the standard use of intensive multimodal therapy (1–3). Primary RTs can arise in the brain [referred to as atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (ATRTs)], the kidney [referred to as malignant rhabdoid tumors (MRTs)], or various soft tissues (4). The incidence and prognoses of RTs vary by tumor location: ATRTs represent about 6% of all pediatric central nervous system tumors, and the probability of 5-year survival of children with ATRT is 30% to 45% (2, 3, 5); that for children with MRT is 20% to 50%, depending on the stage of disease at diagnosis (1).

Although particularly aggressive pediatric cancers, RTs exhibit one of the lowest mutation rates ever characterized (6–9). The sole recurrent mutation detected in nearly all patient samples is biallelic inactivation of the SMARCB1 gene, and RTs are defined, in part, by the loss of expression of SMARCB1 protein (also known as SNF5, INI1, or BAF47) (10–12). SMARCB1 is a subunit of the SWI/SNF family chromatin-remodeling complexes (4). Sequencing studies have shown that genes encoding at least eight other SWI/SNF subunits are found to be recurrently mutated in more than 20% of all cancers, thereby underscoring the importance of this chromatin regulatory complex in cancer (13). Furthermore, inactivation of Smarcb1 in mice resulted in all animals rapidly developing cancer, thus establishing the gene as a potent tumor suppressor (14, 15). Because RTs lack recurrent targetable mutations and their prognoses and survival are poor, improved therapies are greatly needed.

Homoharringtonine (HHT) is a natural plant alkaloid purified from Cephalotaxus species of Chinese plum yew (16, 17). HHT has long been used in Chinese medicine to treat a variety of blood cancers, most notably acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where it yields an approximately 60% complete response rate (18). Although HHT has been studied clinically in the U.S. for decades, the discovery of a semisynthetic method to create a highly purified and consistent version of the drug, termed omacetaxine mepesuccinate (OM), led to its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) resistant to multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors (17, 19). In addition, a recent phase II trial of OM in patients with late-stage myelodysplastic syndrome showed a 33% overall response rate and increased survival (20). Finally, HHT is a safe and effective substitute for anthracyclines in young children with AML (21).

HHT inhibits protein translation by interacting with the A-site of the large ribosomal subunit (22–24). Although translation inhibition most likely leads to widespread changes in protein abundance in cancer cells, the decreased stabilities of a number of specific short-lived proteins have been reported to underlie the sensitivity to HHT, including Mcl-1 (25, 26), c-Myc (17, 27), and BCR–ABL in CML (28). Numerous protein changes most likely contribute to cell cycle arrest and cell death following HHT treatment; however, the precise mechanisms of HHT-mediated loss of cell viability remain unknown.

Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins play key roles in regulating cell death by influencing mitochondrial membrane integrity (29). The Bcl-2 family includes both proapoptotic (Bax, Bad, Noxa, etc.) and antiapoptotic (Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1, etc.) proteins, the balance of which determines whether a cell undergoes apoptosis (29). One particular pair of antiapoptotic proteins, the short-lived Mcl-1 and the more stable Bcl-XL, exhibits a consistent synthetic-lethal relationship in multiple systems (30–32). In general, cells tolerate the loss of one antiapoptotic member, but depletion of both proteins induces apoptosis.

Here, we report the results of our high-throughput screening of small molecules in RT cell lines to identify compounds and drugs to which these tumor cells show high sensitivity. We also investigated the mechanism(s) underlying this sensitivity to find new therapeutic approaches to this devastating pediatric disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (A204, G401, G402), C. David James (BT12, BT16), Children’s Oncology Group (CHLA266), Franck Bourdeaut (KD, MON), Yasumichi Kuwahara (KPMRTRY), Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)/Broad Institute Biological Samples Platform (KYM1, CMLT1, K562, KCL22, KPNYN, LAMA84, LUDLU1, NCIH747, NCIH1755, OVKATE, RMG1, SNU601, SW1783), Bernard Weissman (NCIH2004RT, TM87), and Timothy Triche (TTC549, TTC642, TTC709, TTC1240). Growth conditions are presented in Supplementary Table S1. All cell lines were SNP authenticated before screening and tested for Mycoplasma prior to using new frozen stocks, screening, and in vivo experiments. A luciferase reporter gene was inserted into A204, BT16, and TTC642 cells for in vivo studies and cultured as above.

Concentration-response curve screening

Screening of 481 small molecules across 840 cancer cell lines has been described (33–35). The same procedure was used to screen 47 additional cell lines (5 RTs). Each small molecule was tested over a 16-point concentration range (two-fold dilution) in technical duplicates. Cells were plated at 500 cells/well in 1536-well plates. Small molecules were added 24 hours later, and viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo (Promega) after 72 hours.

Follow-up screening

A cohort of RT, CML, and control cell lines representing multiple lineages were plated and screened with protein-translation inhibitors in a 384-well format as described previously (33, 34). Cells were plated at 1000 cells/well and treated 24 hours later. Small molecules (Supplementary Table S2) were added (1:300 dilution) using a CyBi-Well Vario (Endress+Hauser) pin-transfer machine or an HP D300e Digital Dispenser (Hewlett-Packard), and viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo 72 hours later.

Project Achilles analysis

We analyzed two independent Project Achilles CRISPR–Cas9 genome-scale loss-of-function screens: the GeCKO screen (19Q1) with 43 cancer cell lines (8 RTs) (36) and the Avana screen (19Q1) with 676 cancer cell lines (11 RTs). Preferential genetic dependencies (i.e. genes required for survival) between RTs and other cancer types were calculated as previously described (37). We then performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (38) on the list of preferential RT genetic dependencies using annotated pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (39).

Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated in R by comparing all HHT area under the curve (AUC) values from Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal version 2 (CTRPv2) to transcripts per million (TPM) expression values (CCLE) or to the Avana dependency scores for all genes. Correlation coefficients were transformed using Fisher’s z-transformation to approximate a normal distribution by normalization for cell line number (33).

Immunoblot analysis

For time-course, cells were plated at 2 million cells/plate in 10-cm plates. After 24 hours, cells were treated with HHT (100 nM; Tocris #1416) and harvested at the indicated times. For concentration-response, cells were plated at 300,000 cells/well in 6-well plates, allowed to adhere overnight, and treated with the indicated HHT concentrations for 4 hours. Immunoblots were performed as previously described (37) using antibodies indicated in Supplementary Table S3.

Primary tumor analysis

Primary RT samples were previously profiled using RNA-sequencing through the NCI Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) initiative (http://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target) (40). Additional TARGET TPM expression data for other primary solid tumors were downloaded from UCSC Xena (http://xena.ucsc.edu, TARGET Pan-Cancer (PANCAN) dataset, and TCGA PANCAN dataset). TARGET RT and paired normal kidney samples (dbGaP phs000218.v19.p7) were aligned or realigned with STAR, and transcript quantification was performed with RSEM to generate TPM expression per gene. Expression values were log2 transformed and floored at –3. For the PANCAN datasets, samples annotated as normal, cell line, xenograft, metastatic, or recurrent were excluded. BCL2L1 expression was compared between RT, normal kidney, and all other primary samples in the dataset.

SMARCB1 manipulation

SMARCB1 was expressed in RT cells from pLX401-SMARCB1 (Addgene, #111182) as previously described (37). SMARCB1 knock-out (KO) was performed in 293T cells (ATCC CRL-1573) using the Santa Cruz Ini1 CRISPR–Cas9 KO plasmids (sc-401485). Cells (50% confluent in 60-mm dishes) were transfected with 3 μg total plasmid mixture using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher, #L3000015), and sorted 48 hours later into 96-well plates. At least 30 individual clones were expanded and analyzed for deletion of SMARCB1 by immunoblot and Sanger sequencing. Two individual clones were further characterized for SWI/SNF complex composition by immunoblot, glycerol-sedimentation analysis, and immunoprecipitation/mass spectroscopy analysis (41).

Cell counting

Cells were plated at 100,000 cells/well of a 6-well plate in 2 mL culture media, allowed to adhere overnight, and treated with either DMSO (0.1% final) or HHT (100 nM final). Cells were harvested and counted as previously described (37).

Overexpression of BCL2L1

BCL2L1 and LacZ ORFs were ordered from the Broad Genetic Perturbation Platform (clone IDs: TRCN0000489920 and ccsbBroad304_99994). The ccsbBroad304_99994 was subcloned into the pLX307 vector (i.e., the same backbone as TRCN0000489920) using Gateway cloning (Life Technologies). After sequence verification, ORFs were lentivirally transduced into G402 RT cells. Cells were selected in puromycin for 4 days and then plated for concentration-response curves, HHT treatments followed by immunoblots, or IncuCyte imaging during HHT treatment.

IncuCyte imaging

For live-cell imaging, 1000 cells/well were plated into black clear-bottom plates (Corning, #3764). Small molecules were added 24 hours later using an HP D300e Digital Dispenser and immediately placed on an IncuCyte S3 for 10× phase imaging every 3 hours for 6 days. The phase % confluence metric (analysis metrics: segmentation adjustment 0.4, minimum area 400 μm2) was used to estimate per-well cell doublings relative to the initial scan.

RT xenografts

The pilot TTC642 in vivo studies were performed according to the approved protocols of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) using 6- to 8-week-old female NCr nude mice (Taconic, #NCRNU-F). For the tolerability study, three mice/arm were injected once daily with HHT dissolved in normal saline at either 2 or 3 mg/kg intraperitoneally (IP) or 3 mg/kg subcutaneously (SC). The body weight of each mouse was recorded daily to monitor drug tolerability. For the efficacy study, two million TTC642 cells in 100 μL [1:1 PBS:Matrigel (Corning, #354234)] were implanted subcutaneously into right flanks. When tumors reached approximately 150–250 mm3, mice were randomized [stratified randomization; Study Director 3.1 (Studylog)] to vehicle or HHT treatment (n=8 mice per arm). HHT (2 mg/kg) or saline vehicle was injected IP once daily for 28 days. Tumor volume (Volume = length*width2/2; measured with calipers) and body weight were measured twice per week. The primary endpoint was total tumor volume larger than 2000 mm3.

The follow-up studies were performed upon approval from the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s IACUC using athymic nude immunodeficient mice (Charles River Laboratories #553). Five million luciferase-labeled A204, BT16, and TTC642 cells or unlabeled SJMRT031055_X1 patient-derived xenograft cells [obtained from the Childhood Solid Tumor Network (http://www.stjude.org/CSTN/), dissociated, passaged, and cryo-preserved as a single cell suspension as described previously (42)] were implanted subcutaneously in right flanks with 50% Matrigel. Mice injected with luciferase-labeled cells were screened weekly by Xenogen® imaging and enrolled after achieving a target bioluminescence signal of 107 photons/sec/cm2 or a palpable tumor. Mice injected with SJMRT031055_X1 cells were observed weekly until a palpable tumor was detected. Chemotherapy started the following week.

Clinical grade vincristine (VCR; Hospira 1 mg/mL) and doxorubicin (DOXO; Actavis 2 mg/mL) were sourced from the St. Jude pharmacy. Mice were randomized into the following treatment groups: VCR (0.5 mg/kg IP once on days 1, 8, 15, and 22), DOXO+VCR (DOXO 6 mg/kg IP once on day 1, VCR as above), HHT 0.75 mg/kg (0.75 mg/kg SC twice daily on days 1–14), HHT 0.75 mg/kg+VCR (both as above), HHT 2 mg/kg (2 mg/kg IP once daily on days 1–28), HHT 2 mg/kg+VCR (both as above), and placebo (no chemotherapy).

Mice received two 28-day courses of chemotherapy. All mice were monitored daily including twice-weekly caliper measurements. For mice injected with luciferase-labeled cell lines, bioluminescence was monitored weekly. Mice with a signal of less than 105 photons/sec/cm2 (similar to background) were classified as complete response (CR) and 105-107 photons/sec/cm2 as partial response (PR). For SJMRT031055_X1, CR was defined as an undetectable tumor by calipers at endpoint. Endpoints included completion of the two courses and tumor burden at any time greater than 20% of body weight (tumor typically 3–5g). Mice that were found dead or moribund for reason other than tumor burden (e.g. unexpected death or drug toxicity) while not at endpoint were censored from the study but are reported in Supplementary Table S4.

Xenogen® Imaging and Quantification

Mice bearing luciferase-labeled cells were injected IP with Firefly D-Luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences; 3 mg/mouse). Bioluminescent images were taken five minutes later using the IVIS® 200 imaging system. Anesthesia was administered throughout image acquisition (isoflurane 1.5% in O2 at 2 liters/min). The Living Image 4.3 software (Caliper Life Sciences) was used to generate a standard region of interest (ROI) encompassing the largest tumor at maximal bioluminescence signal. The identical ROI was used to determine the average radiance (photons/s/cm2/sr) for all xenografts.

Results

RT cell lines are sensitive to HHT

We sought to identify small molecules to which RTs are preferentially sensitive by screening eight RT cell lines as part of the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal version 2 [CTRPv2 (33–35)]. In this unbiased screening platform, up to 887 cancer cell lines were treated with 16 concentrations (serial two-fold dilutions) of 481 small molecules, and AUC values were calculated for each cell line–molecule pair. When we compared the AUC values of RT cell lines with those of all other cancer cell lines, RT cell lines were particularly sensitive to HHT (Fig. 1A). All eight RT cell lines scored among the top 20% most sensitive cancer cell lines (Fig. 1B–C). Although individual RT cell lines were highly sensitive to other small molecules [Fig. 1A–B, (35, 37)], HHT was the most consistently effective drug, showing high activity against all RT cell lines tested.

Figure 1.

RT cell lines are highly sensitive to HHT. (A) Results of the CTRPv2 small-molecule screen were used to compare the median AUC of RT cell lines (n=8) with that of all other cancer cell lines (CCLs, n=840). Each circle represents one compound (n=481); HHT is indicated in red. A greater positive value indicates that RT cells are more sensitive to that compound. Significance was calculated using a K-test based on the distribution of AUC values across RT and other cancer cell lines. (B) All FDA-approved or clinical trial compounds in the CTRPv2 are ranked by the percentile of the least sensitive RT cell line. A lower percentile indicates that the cell line is more sensitive. (C) Dose-response curves of all CCLs (gray) to HHT (n=880); the RT cell lines (n=8) are indicated in blue. (D) HHT dose-response curves of an expanded set of RT (blue; n=16), CML (red; n=4), and control (gray; n=8) cancer cell lines. Error bars show SD of 2–4 biological replicates. (E) Distribution of AUC calculated from curves in C. A smaller AUC indicates greater sensitivity. Dashes indicate the median and interquartile ranges. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons correction. ***, P <0.001; ****, P <0.0001; NS, not significant.

Because HHT/OM has been approved by the FDA for treatment of CML, we compared the sensitivity of RT cells to that of CML cells. We performed HHT concentration-response curves in an expanded set of 16 RT cell lines, four CML cell lines, and eight control cancer cell lines that do not contain mutations in any SWI/SNF subunits (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. S1A–S1B). All additional RT cell lines were either as sensitive or more sensitive to HHT than were the RT cell lines included in the initial screening dataset (Fig. 1C). Sensitivity did not differ across the RT cell lines derived from three different anatomic locations (Supplementary Fig. S1C). These observations suggest that ATRTs, MRTs, and soft-tissue RTs are broadly sensitive to HHT.

RT (P<0.0001) and CML (P=0.0005) cell lines were significantly more sensitive to HHT than were the control cancer cell lines, but we found no difference (P=0.9551) in sensitivity between RT and CML cell lines (Fig. 1E). This result was surprising, given that hematopoietic and lymphoid cell lines (such as CML) were significantly (P<0.0001) more sensitive, on average, to all small molecules in the CTRPv2 than were other histologic types of cells (such as RTs) (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Together, these observations demonstrate that RT cell lines are highly and consistently sensitive to HHT at levels comparable to CML cell lines, which model the FDA-approved indication for the drug.

RT cells are sensitive to the loss of ribosomal subunits

Next, we investigated the mechanism underlying the sensitivity of RT cell lines to HHT. Given the established role of HHT in inhibiting ribosome function, we first evaluated whether RTs are also preferentially sensitive to genetic loss of ribosomal subunits. We recently reported the results of genome-scale CRISPR–Cas9 screens in various RT cell lines (35, 37, 41). Here, we used GSEA to probe these two independent sets of CRISPR–Cas9 dependency screens, one with 43 cancer cell lines (8 RT lines) (36) and the other with 676 cancer cell lines (11 RT lines). In both datasets, ribosomal subunits scored among the top two most preferentially represented pathways (out of 186) in RT cell lines (Fig. 2A–D). These analyses suggest that RT cell lines are more sensitive to genetic loss of the ribosome than are other cancer cell lines, which is concordant with RT cell lines exhibiting greater sensitivity to HHT.

Figure 2.

RT cells are particularly sensitive to the loss of ribosomal subunits. (A) GSEA using KEGG pathways on the preferential RT dependencies ranked by effect size in the GeCKO library CRISPR–Cas9-inactivation screens of RT (n=8) and other cancer cell lines (n=35). The top 10 pathways by normalized effect size are plotted. (B) GSEA plot for the KEGG ribosome pathway. More negative values (further right) indicate that the gene has a greater dependency in RT cell lines. (C-D) As in A-B, for the Avana library CRISPR–Cas9 dataset of RT (n=11) and other cancer cell lines (n=665).

To determine whether this dependency on ribosomal subunits is recapitulated by treatment with additional translation inhibitors, we screened the expanded cohort of RT and control cell lines introduced above with seven other inhibitors that were not part of the full CTRPv2 screen. Although RT lines were significantly more sensitive than the control lines to four (anisomycin: P=0.0026; bruceantin: P<0.0001; emetine: P=0.0044; verrucarin: P<0.0001) of the seven small molecules (Supplementary Fig. S2A–G), HHT was the protein-translation inhibitor to which the RT cell lines were most preferentially sensitive compared to control cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S2H). In addition, clustering analysis of the various protein-translation inhibitors revealed that RT cell line–specific sensitivity to HHT was most similar to sensitivity to bruceantin (Supplementary Fig. S2I), which also binds the A-site of the ribosome (24). Overall, these findings suggest that RT lines are generally sensitive to the loss of protein translation, but HHT is particularly effective across all RT cell lines studied.

RTs express low levels of BCL2L1, the best predictor of HHT sensitivity

Although it is well established that HHT inhibits the ribosome, the specific proteins affected by HHT and, in turn, the effects of those altered proteins on cell viability remain undefined. Examining gene expression and genetic dependency data for hundreds of cancer cell lines, we asked whether any predictive features suggested a plausible mechanism of action underlying HHT sensitivity. Across all cancer cell lines screened and of the nearly 17,000 gene-expression features studied, the greatest predictor of HHT sensitivity was low expression of BCL2L1 (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. S3A). With respect to genetic dependencies, of the more than 18,000 genes assessed, the best predictor of HHT sensitivity was vulnerability to the loss of MCL1 (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Fig. S3B). Notably, BCL2L1 and MCL1 have a well-established synthetic-lethal relationship in multiple contexts (30–32). Additionally, HHT causes rapid depletion of Mcl-1 (25, 26). These observations suggest that low expression of the more stable Bcl-XL protein sensitizes cells to HHT-mediated depletion of the shorter-lived Mcl-1 protein.

Figure 3.

RT cells express low levels of BCL2L1, the strongest predictor of sensitivity to HHT. (A) Distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients comparing the sensitivity to HHT with gene expression levels of all genes (n=16,973). (B) Distribution of Pearson correlation coefficients comparing the sensitivity to HHT with gene dependency scores of all genes (n=18,330) in the Avana CRISPR–Cas9 dataset. Each dot represents one gene. (C) Distribution of BCL2L1 gene expression in RT (n=21) and all other (n=1144) cancer cell lines (CCLs). Dashes indicate median and interquartile ranges. Significance was calculated using a two-sided unpaired t-test. (D) Immunoblots of Bcl-XL protein across RT, CML, and control cell lines. Both blots were processed and scanned simultaneously. (E) Comparison of BCL2L1 expression in log2-transformed TPM in primary MRTs and matched normal kidney samples (n=6 pairs). Significance was calculated using a two-sided paired t-test. (F) As in E, for all primary MRTs (n=37) and normal kidney samples (n=12). Dashes indicate the median and interquartile ranges. (G) BCL2L1 expression in primary MRTs (blue; n=37) and other primary tumor samples (n=7,687). Boxes show median and interquartile ranges. Outliers were determined by the Tukey method. Other primary tumors included in the analysis were as follows: adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC; n=77), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA; n=407), brain lower-grade glioma (LGG; n=509), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA; n=1,092), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC; n=304), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL; n=36), clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK; n=13), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD; n=288), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC; n=47), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA; n=181), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; n=153), head & neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC; n=518), kidney chromophobe (KICH; n=66), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC; n=530), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP; n=288), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC; n=369), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD; n=513); lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC; n=498), mesothelioma (MESO; n=87), neuroblastoma (NBL; n=153), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV; n=418), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD; n=178), pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG; n=177), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD; n=495), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ; n=92), sarcoma (SARC; n=258), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM; n=102), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD; n=414), testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT; n=148), thymoma (THYM; n=119), thyroid carcinoma (THCA; n=504), uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS; n=57), uterine corpus endometrioid carcinoma (UCEC; n=180), uveal melanoma (UVM; n=79), Wilms tumor (WT; n=120). ***, P <0.001; ****, P <0.0001.

Next, we questioned whether these global correlations across all cancer cell lines explained the observed sensitivity of RT cells to HHT. RT cell lines expressed significantly (P<0.0001) less BCL2L1 RNA than the average expression of BCL2L1 of all cell lines in the CCLE (43, 44) (Fig. 3C). RT cell lines were significantly (GeCKO: P=0.0490; Avana: P=0.0431) more dependent on MCL1 for cell viability than were the other cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S3C–D). In contrast, we did not find any difference (P=0.6817) in BCL2L1 expression among RT cell lines derived from different anatomic locations (Supplementary Fig. S3E), suggesting that low expression of BCL2L1 is a common feature of all types of RT. When we assessed the levels of Bcl-XL in the expanded set of RT cell lines and control cell lines, we found Bcl-XL at low levels in 14 of 16 RT cell lines and at moderate levels in the remaining two (Fig. 3D). Bcl-XL was expressed at high levels in some CML cell lines, suggesting that additional mechanisms, such as HHT-mediated loss of the short-lived BCR–ABL fusion protein (28), most likely contribute to CML sensitivity to HHT (Fig. 3D). Together, these results show that RT cell lines express low levels of BCL2L1, which was the best indicator of sensitivity to HHT across the CTRPv2 dataset.

To investigate whether these observations in cell lines extended to primary RTs, we analyzed RNA-sequencing data of primary MRTs (40) paired with normal kidney samples and other primary solid tumors. BCL2L1 expression was significantly (P=0.0002) lower in MRT samples than in matched normal kidney cells (Fig. 3E), a finding confirmed (P<0.0001) when all MRT samples were compared to all normal kidney samples in the dataset (Fig. 3F). In addition, when we compared primary MRT samples with more than 7500 other primary tumor samples from 35 different lineages, we discovered that MRTs expressed substantially less BCL2L1 than all but one other solid tumor type (Fig. 3G). Interestingly, the three lineages that expressed the lowest level of BCL2L1 were all pediatric kidney cancers. These observations emphasize that the expression of BCL2L1 is particularly low in primary MRTs and preclinical RT models.

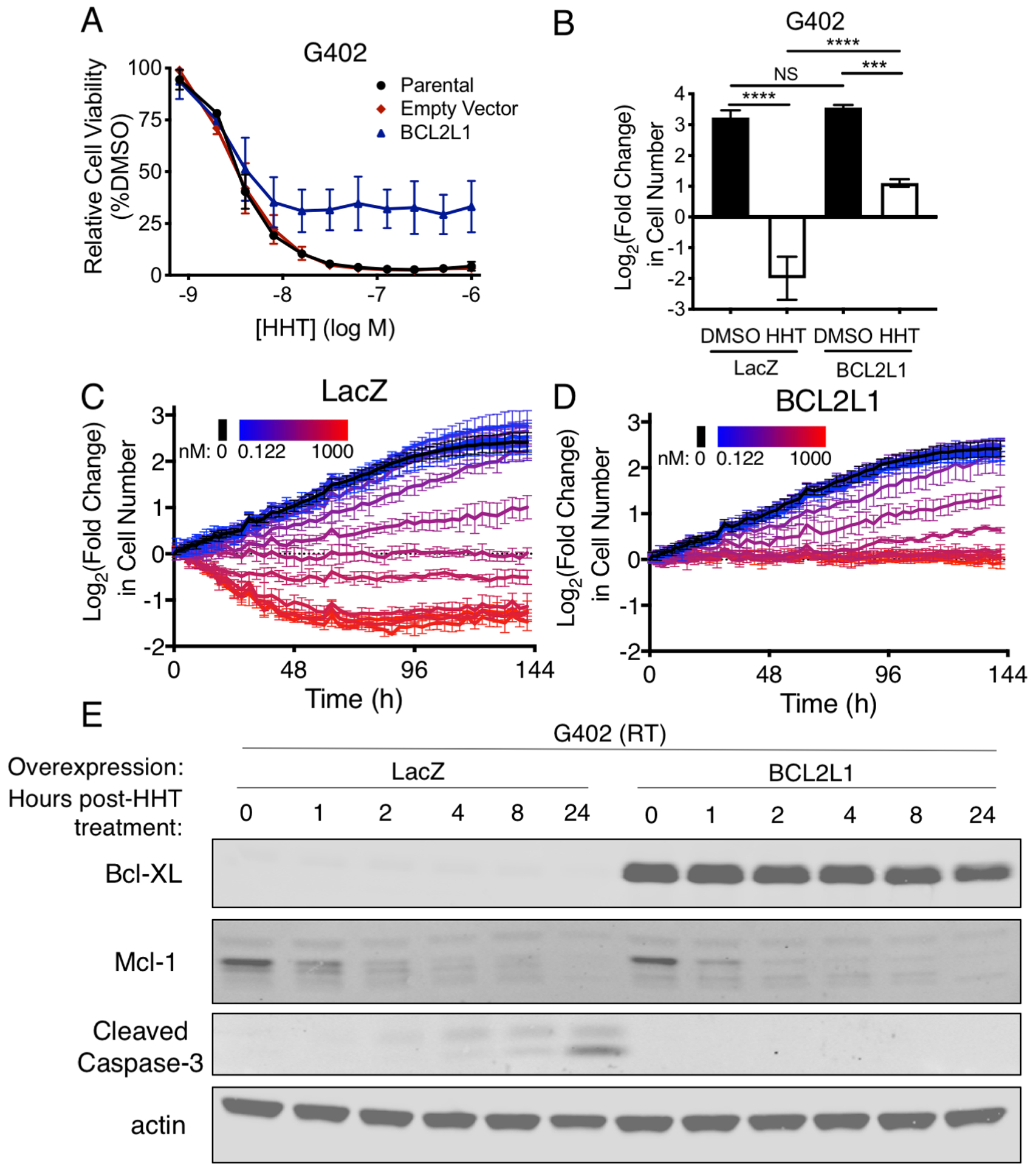

Low BCL2LI expression increases the sensitivity of RT cells to HHT

The inverse correlations between HHT sensitivity and BCL2L1 expression prompted us to assess the consequence of HHT treatment on the levels of Bcl-2 family proteins. In RT (G402) and CML (K562) cell lines, we observed substantial depletion of Mcl-1, which directly preceded the cleavage of caspase-3 only in RT cells that expressed low levels of Bcl-XL (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Bcl-XL expression was not substantially affected by HHT treatment (Fig. 4A). Mcl-1 was also depleted to a lesser extent upon HHT treatment in a control (NCIH1755) cell line with a medium-level sensitivity to HHT, also without accompanying caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 4A). Depletion of Mcl-1 and cleavage of caspase-3 occurred in a concentration-dependent manner in RT cells (Fig. 4B). We confirmed this finding of preferential cytotoxicity by conducting cell-count experiments in additional RT cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S4A–S4F). These observations suggest that HHT depletes Mcl-1 in many cell types, but a greater apoptotic response occurs in cells that express lower levels of Bcl-XL at baseline. This may explain why RTs, which express especially low baseline levels of Bcl-XL, are particularly sensitive to HHT.

Figure 4.

Treatment with HHT induces apoptosis in RT cells after the loss of Mcl-1 but not Bcl-XL. (A) Immunoblots of RT (G402), CML (K562), and control (NCIH1755) cells were assessed after treatment with 100 nM HHT for the indicated times. (B) Immunoblots of the same cell lines as in A were generated after treatment with increasing (half-log) concentrations of HHT for 4 h. Blots in A and B are representative of three biological replicates.

To confirm that the level of BCL2L1 expression determines HHT sensitivity, we overexpressed BCL2L1 in an RT cell line. While increased expression of BCL2L1 only modestly shifted the IC50 value towards resistance, it substantially reduced the maximal cytotoxicity caused by HHT treatment across multiple logs of concentrations (Fig. 5A–B). In addition, IncuCyte tracking of G402 cells showed that although LacZ-expressing G402 cells exhibited cytotoxicity at about 62 nM HHT (Fig. 5C), similar to the reported Cmax of 46 nM from a single dose of HHT in humans, those overexpressing BCL2L1 were resistant to HHT-mediated cytotoxicity at concentrations as high as 1 μM (Fig. 5D). Expression of BCL2L1 also substantially inhibited the cleavage of caspase-3 without affecting the loss of Mcl-1 (Fig. 5E), and did so in a highly concentration-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Overall, these results confirm that the expression of BCL2L1 influences the sensitivity of cancer cell lines to HHT.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of BCL2L1 causes resistance to HHT. (A) Dose-response curves of G402 RT cells transduced with parental (black), empty vector (red), or BCL2L1-overexpressing vector (blue) and treated with HHT. Error bars indicate the SD of three biological replicates. (B) Cell counts of G402 RT cells overexpressing LacZ or BCL2L1 treated with DMSO (black) or HHT (white, 100 nM) for 72 h. Data show mean ± SD of three biological replicates. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons correction. (C-D) IncuCyte tracking of G402 RT cells expressing LacZ (C) or BCL2L1 (D) treated with various concentrations of HHT, ranging from 0.122 nM (blue) to 1000 nM (red) with two-fold dilutions. Error bars indicate the SD of three technical replicates. (E) Immunoblots of antiapoptotic proteins and apoptotic induction were assessed after HHT treatment (100 nM) of G402 cells overexpressing LacZ or BCL2L1. ***, P <0.001; ****, P <0.0001; NS, not significant.

Low BCL2L1 expression in RT cells suggested that either the cell(s) of origin of RTs expresses abnormally low levels of BCL2L1 compared to neighboring normal cells, or SMARCB1 mutation leads to transcriptional repression of BCL2L1. To differentiate between these possibilities, we re-expressed SMARCB1 in three RT cell lines. We found no substantial differences in Bcl-XL protein expression when SMARCB1 was re-expressed (Supplementary Fig. S5B). Furthermore, while re-expression of SMARCB1 causes resistance to multiple other drugs (37, 45), we found no changes in RT sensitivity to HHT (Supplementary Fig. S5C–E). In addition, CRISPR–Cas9-mediated deletion of SMARCB1 in 293T cells did not increase sensitivity to HHT (Supplementary Fig. S5F–G). Overall, these results suggest that, rather than SMARCB1 mutation directly conferring sensitivity to HHT, RT progenitor cells transformed by the loss of SMARCB1 express low BCL2L1, which makes them inherently sensitive to HHT.

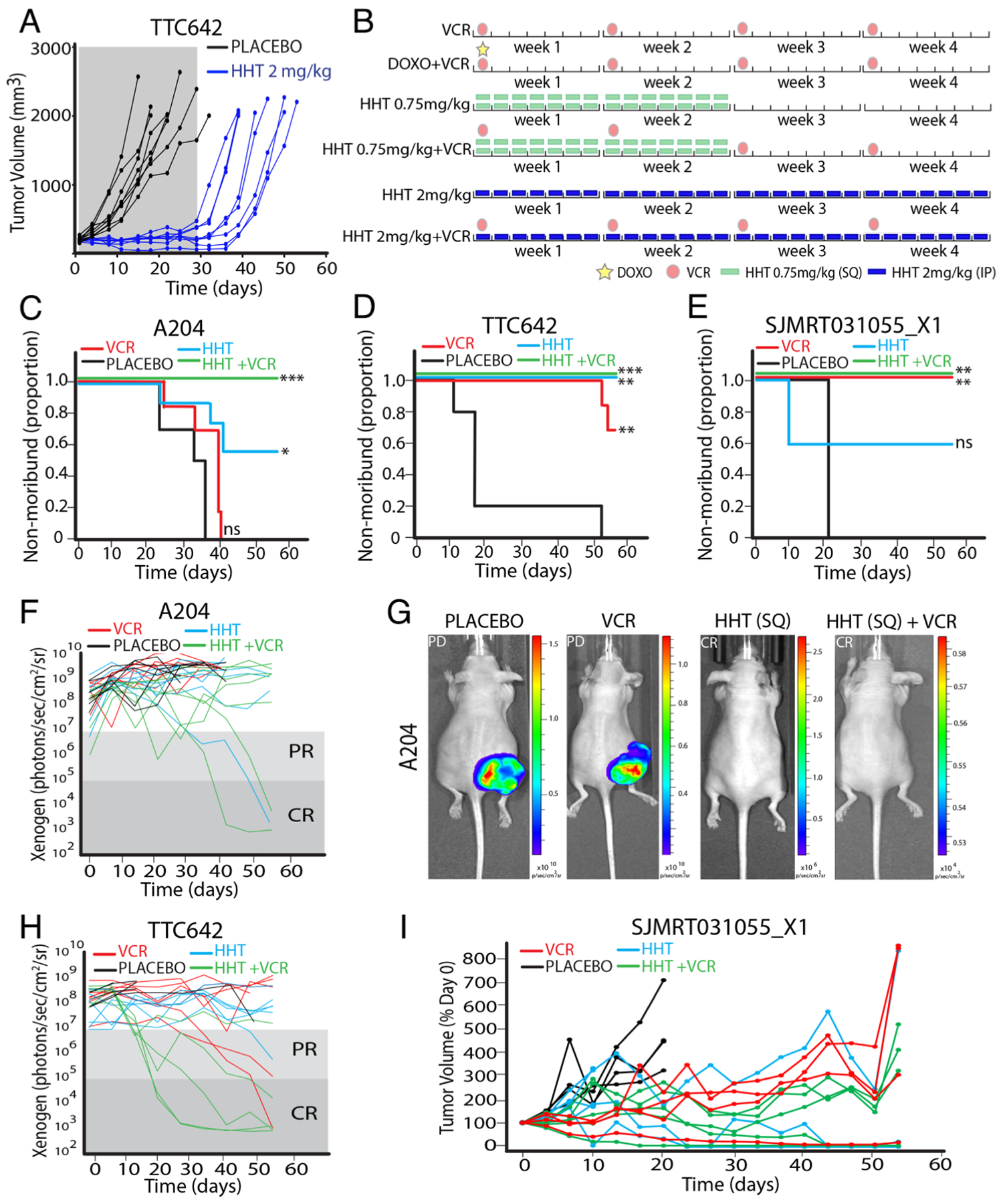

HHT inhibits RT growth in vivo

To confirm these cell culture-based findings in vivo, we performed preclinical testing using RT xenografts. Given the wide range of HHT doses used in vivo in the literature, we first performed a pilot tolerability study. A dose of 2 mg/kg HHT injected IP was well tolerated, but 3 mg/kg HHT caused substantial weight loss (Supplementary Fig. S6A). We began with TTC642 cells because they had a highly penetrant tumor-formation phenotype in mice (37). We then treated mice bearing RT xenografts with 2 mg/kg HHT injected IP once daily for 28 days; this blocked xenograft growth during the treatment period and significantly increased the survival of mice bearing xenograft tumors (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Fig. S6B) (P<0.0001). The tumors resumed growth once HHT was withdrawn.

Figure 6.

HHT inhibits RT xenograft growth in vivo. (A) Tumor volumes of vehicle (black) and HHT (blue) treated mice. Gray box indicated the treatment window. (B) Schematic of treatment arms. Two identical cycles for eight weeks total were given. VCR: vincristine; DOXO: doxorubicin. (C-E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing survival of A204 (C), TTC642 (D), and SJMRT031055_X1 (E) tumor-bearing mice. HHT groups were treated on the 0.75 mg/kg BID schedule. Significance was calculated using a Mantel-Cox test. (F) Xenogen values for A204 tumor-bearing mice. (G) Representative images of A204 tumor-bearing mice treated as indicated. (H) As in F for TTC642 tumor-bearing mice. (I) Tumor volumes for mice bearing SJMRT031055_X1 PDX. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

We next pursued a preclinical study using a previously described design (46) using four independent models: three luciferase-labeled cell-line xenografts (A204, BT16, and TTC642) and one patient-derived xenograft (PDX; SJMRT031055_X1). We designed the study with seven arms, each treated with two four-week cycles for a total of 8 weeks (Fig. 6B). We used three separate control arms: untreated; standard-of-care therapy vincristine (VCR); and standard-of-care combination therapy doxorubicin (DOXO) + VCR. The four experimental arms contained HHT: HHT at 0.75 mg/kg twice daily (BID) for 14 days followed by 14 days off (the calculated mouse equivalent of the FDA-approved schedule for CML); HHT at 0.75 mg/kg BID + VCR; HHT at 2 mg/kg daily (QD) for 28 days (equivalent to the pilot study); and HHT at 2 mg/kg QD + VCR. Five to seven mice bearing tumors of each xenograft type were randomized to each treatment arm.

Overall, we observed very similar findings between the two different HHT treatment schedules (Supplementary Fig. S6C–F), and so focused on the FDA-approved clinical schedule, but the full dataset is included in Supplementary Table S4. We also observed a higher degree of toxicity in the combined DOXO + VCR arm in this study (Supplementary Table S4).

In all four xenograft models we observed significant increases in mouse survival upon treatment with HHT alone (A204: P=0.0155; BT16: P=0.0387; TTC642: P=0.0009) or HHT in combination with VCR (A204: P=0.0004; TTC642: P=0.0020; SJMRT031055_X1: P=0.0047; Fig. 6C–E, Supplementary Fig. S6G). Complete responses (CR) were observed in some mice bearing all four xenograft types treated with HHT-based regimens (Fig. 6F–I; Supplementary Fig. S6H). Across all models, 16 CR (19.75% of 81) were observed in the four HHT-based treatment arms (Supplementary Table S4). In comparison, 3 CR (10.34% of 29) were observed in standard-of-care arms (Supplementary Table S4). Overall, HHT, alone and in combination, demonstrated efficacy in each of the four models.

Discussion

We tested 481 small molecules across a large number of RT cell lines and discovered that RT cell lines were highly and consistently sensitive to HHT. Because HHT/OM is an FDA-approved drug, these observations may have immediate therapeutic relevance. RT cell lines were as sensitive to HHT as were CML cell lines. A recent trial showed the safety and efficacy of HHT in children younger than 2 years with AML (21). This finding is particularly relevant, given the similar young age of patients with RTs.

We found that the baseline expression of BCL2L1 predicted the sensitivity of all cancer cell lines to HHT. This finding is consistent with an earlier report that higher expression of Bcl-XL predicts resistance to apoptosis in some leukemia cell lines (47). These findings may help identify additional types or subtypes of cancer beyond RTs that will most likely respond to HHT. In the case of RTs, all cell lines that we tested expressed low BCL2L1, and primary MRTs expressed among the lowest levels of BCL2L1 of all primary solid tumors tested. This low expression of BCL2L1 makes RT cells more sensitive to HHT-mediated depletion of Mcl-1, though we cannot eliminate the possibility that the depletion of additional proteins contributes to RT sensitivity to the drug. Consistent with the reduced Mcl-1 expression in RT cells upon HHT treatment reported here, an earlier report showed that RT cell lines are sensitive to the loss of Mcl-1 (48). Together, our experiments provide further evidence that HHT sensitivity depends on the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins.

The experiments reported here suggest that low expression of BCL2L1 is a property of RT cells independent of mutation in SMARCB1, although it remains possible that mutation in SMARCB1 influences BCL2L1 expression on a different timescale or in contexts not investigated here. One possible mechanism is that the undefined cell(s) of origin that are susceptible to transformation by SMARCB1 loss intrinsically express low levels of BCL2L1. We also observed that the three cancer types that expressed the lowest levels of BCL2L1 in primary samples were all pediatric kidney cancers. Together, these findings may point to a unique regulation of BCL2L1 in a subset of cells in the developing kidney that is reflected in tumors that arise from those cells. However, we also found that RT cell lines and xenografts derived from tissues other than kidney were susceptible to HHT, and similarly express low levels of BCL2L1, suggesting a broad relationship across the varied origins of these SMARCB1-deficient RTs. Testing of other pediatric kidney cancers for sensitivity to HHT could also be considered in future studies.

Our in vivo studies showed that HHT, either alone or in combination with the standard-of-care therapy VCR, led to a significant increase in average mouse survival in four independent models of RT, including one PDX. In addition, CRs were observed in HHT-treated mice bearing all four xenograft models and, in some models, HHT-based regimens outperformed standard-of-care arms. Importantly, the FDA-approved treatment schedule of HHT/OM was well-tolerated, both alone and in combination with VCR. We did observe a range of responses with some tumors continuing to progress with HHT treatment. Further studies will be needed to assess whether longer treatment courses, as well as additional standard-of-care and novel therapeutic combinations, could provide even greater benefit.

The equal sensitivities to HHT of RT and CML cell lines combined with the inhibition of RT tumor growth mediated by HHT in four independent xenograft models is promising. HHT has exhibited both efficacy and a favorable safety profile in young children; thus, it may be an effective treatment for the often-fatal RT. Clinical studies with this FDA-approved drug are needed to assess whether HHT, alone and in combination with other chemotherapies, holds promise for RT patients.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Rhabdoid tumors afflict young children and are associated with poor (30%−45%) survival. Those children who do survive often suffer debilitating short- and long-term toxicities caused by high-dose chemotherapy and radiation. Thus, more effective treatment is greatly needed. We found that rhabdoid tumor cell lines were as sensitive to the protein-translation inhibitor homoharringtonine as were models of chronic myelogenous leukemia, the drug’s FDA-approved indication. This result suggests that homoharringtonine may similarly improve the survival of children with rhabdoid tumors. We also identified low expression of the tumor-suppressor gene BCL2L1 as a biomarker for homoharringtonine sensitivity across all cancer types. This finding has the potential to advance the development of new, more effective treatment(s) for rhabdoid tumors and other cancers with a similar low BCL2L1-expression profile.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Roberts, Hahn, and Schreiber labs for insightful discussions. We thank Angela McArthur for manuscript comments. We thank Franck Bordeaut, C. David James, Yasumichi Kuwahara, Timothy Triche, and Bernard Weissman for cell lines. We thank Payton Archer, Childhood Solid Tumor Network, Preclinical Pharmacokinetics Shared Resource, and Center for In Vivo Imaging and Therapeutics at St. Jude for resources and assistance with in vivo studies. Support includes U.S. NIH grants T32GM007753 (TPH), T32GM007226 (TPH), P50CA101942 (ALH), R00CA197640 (XW), U01CA176058 (WCH), R01CA172152 (CWMR), and R01CA113794 (CWMR); ACS Mentored Research Scholar 132943-MRSG-18-202-01-TBG (ALH), Cure AT/RT Now (CWMR), Avalanna Fund (CWMR), Garrett B. Smith Foundation (CWMR), and ALSAC (CWMR, EAS). This work is partially based on data generated by the Cancer Target Discovery and Development (CTD2) Network (https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/ctd2/data-portal) and the TARGET initiative.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

W.C.H. is a consultant for Thermo Fisher, Solasta Ventures, MPM Capital, Frontier Medicines, Tyra Biosciences and Paraxel and a founder and a member of the scientific advisory board for KSQ Therapeutics. S.L.S. serves on the Board of Directors of the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation; is a shareholder and serves on the Board of Directors of Jnana Therapeutics; is a shareholder of Forma Therapeutics; is a shareholder and advises Decibel Therapeutics and Eikonizo Therapeutics; serves on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Eisai Co., Ltd., Ono Pharma Foundation, and F-Prime Capital Partners; and is a Novartis Faculty Scholar.

References

- 1.Dome JS, Fernandez CV, Mullen EA, Kalapurakal JA, Geller JI, Huff V, et al. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: renal tumors. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2013;60(6):994–1000. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartelheim K, Nemes K, Seeringer A, Kerl K, Buechner J, Boos J, et al. Improved 6-year overall survival in AT/RT - results of the registry study Rhabdoid 2007. Cancer medicine. 2016;5(8):1765–75. doi: 10.1002/cam4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer-Valuck BW, Chen I, Srivastava AJ, Floberg JM, Rao YJ, King AA, et al. Assessment of the treatment approach and survival outcomes in a modern cohort of patients with atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors using the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2017;123(4):682–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts CW, Biegel JA. The role of SMARCB1/INI1 in development of rhabdoid tumor. Cancer biology & therapy. 2009;8(5):412–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woehrer A, Slavc I, Waldhoer T, Heinzl H, Zielonke N, Czech T, et al. Incidence of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in children: a population-based study by the Austrian Brain Tumor Registry, 1996–2006. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5725–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieran MW, Roberts CW, Chi SN, Ligon KL, Rich BE, Macconaill LE, et al. Absence of oncogenic canonical pathway mutations in aggressive pediatric rhabdoid tumors. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2012;59(7):1155–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee RS, Stewart C, Carter SL, Ambrogio L, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, et al. A remarkably simple genome underlies highly malignant pediatric rhabdoid cancers. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122(8):2983–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI64400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torchia J, Picard D, Lafay-Cousin L, Hawkins CE, Kim SK, Letourneau L, et al. Molecular subgroups of atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours in children: an integrated genomic and clinicopathological analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16(5):569–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johann PD, Erkek S, Zapatka M, Kerl K, Buchhalter I, Hovestadt V, et al. Atypical Teratoid/Rhabdoid Tumors Are Comprised of Three Epigenetic Subgroups with Distinct Enhancer Landscapes. Cancer cell. 2016;29(3):379–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Versteege I, Sevenet N, Lange J, Rousseau-Merck MF, Ambros P, Handgretinger R, et al. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature. 1998;394(6689):203–6. doi: 10.1038/28212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biegel JA, Zhou JY, Rorke LB, Stenstrom C, Wainwright LM, Fogelgren B. Germ-line and acquired mutations of INI1 in atypical teratoid and rhabdoid tumors. Cancer research. 1999;59(1):74–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sevenet N, Sheridan E, Amram D, Schneider P, Handgretinger R, Delattre O. Constitutional mutations of the hSNF5/INI1 gene predispose to a variety of cancers. American journal of human genetics. 1999;65(5):1342–8. Epub 1999/10/16. doi: 10.1086/302639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadoch C, Hargreaves DC, Hodges C, Elias L, Ho L, Ranish J, et al. Proteomic and bioinformatic analysis of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes identifies extensive roles in human malignancy. Nature genetics. 2013;45(6):592–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts CW, Galusha SA, McMenamin ME, Fletcher CD, Orkin SH. Haploinsufficiency of Snf5 (integrase interactor 1) predisposes to malignant rhabdoid tumors in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(25):13796–800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250492697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts CW, Leroux MM, Fleming MD, Orkin SH. Highly penetrant, rapid tumorigenesis through conditional inversion of the tumor suppressor gene Snf5. Cancer cell. 2002;2(5):415–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Santini V, Murgo A, Cheson B, O’Brien SM. Homoharringtonine: history, current research, and future direction. Cancer. 2001;92(6):1591–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi V, Plunkett W, Cortes JE. Omacetaxine: a protein translation inhibitor for treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20(7):1735–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo CY, Tang JY, Wang YP. Homoharringtonine: a new treatment option for myeloid leukemia. Hematology. 2004;9(4):259–70. doi: 10.1080/10245330410001714194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, Rea D, Wetzler M, Lipton JH, Akard L, et al. Final analysis of the efficacy and safety of omacetaxine mepesuccinate in patients with chronic- or accelerated-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: Results with 24 months of follow-up. Cancer. 2015;121(10):1637–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Short NJ, Jabbour E, Naqvi K, Patel A, Ning J, Sasaki K, et al. A phase II study of omacetaxine mepesuccinate for patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia after failure of hypomethylating agents. American journal of hematology. 2019;94(1):74–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Tang Y, Chen J, Chen R, Gu L, Xue H, et al. Homoharringtonine is a safe and effective substitute for anthracyclines in children younger than 2 years old with acute myeloid leukemia. Frontiers of medicine. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang MT. Harringtonine, an inhibitor of initiation of protein biosynthesis. Molecular pharmacology. 1975;11(5):511–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fresno M, Jimenez A, Vazquez D. Inhibition of translation in eukaryotic systems by harringtonine. European journal of biochemistry. 1977;72(2):323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurel G, Blaha G, Moore PB, Steitz TA. U2504 determines the species specificity of the A-site cleft antibiotics: the structures of tiamulin, homoharringtonine, and bruceantin bound to the ribosome. Journal of molecular biology. 2009;389(1):146–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allan EK, Holyoake TL, Craig AR, Jorgensen HG. Omacetaxine may have a role in chronic myeloid leukaemia eradication through downregulation of Mcl-1 and induction of apoptosis in stem/progenitor cells. Leukemia. 2011;25(6):985–94. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen R, Guo L, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Wierda WG, Plunkett W. Homoharringtonine reduced Mcl-1 expression and induced apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(1):156–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-262808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu S, Wang J. Homoharringtonine and omacetaxine for myeloid hematological malignancies. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2014;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Hu Y, Michaels S, Segal D, Brown D, Li S. Inhibitory effects of omacetaxine on leukemic stem cells and BCR-ABL-induced chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in mice. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1446–54. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kale J, Osterlund EJ, Andrews DW. BCL-2 family proteins: changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(1):65–80. Epub 2017/11/18. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi H, Chen MC, Pham H, Matsuo Y, Ishiguro H, Reber HA, et al. Simultaneous knock-down of Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 induces apoptosis through Bax activation in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(12):2980–7. Epub 2013/08/21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han K, Jeng EE, Hess GT, Morgens DW, Li A, Bassik MC. Synergistic drug combinations for cancer identified in a CRISPR screen for pairwise genetic interactions. Nature biotechnology. 2017;35(5):463–74. Epub 2017/03/21. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najm FJ, Strand C, Donovan KF, Hegde M, Sanson KR, Vaimberg EW, et al. Orthologous CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes for combinatorial genetic screens. Nature biotechnology. 2018;36(2):179–89. Epub 2017/12/19. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rees MG, Seashore-Ludlow B, Cheah JH, Adams DJ, Price EV, Gill S, et al. Correlating chemical sensitivity and basal gene expression reveals mechanism of action. Nature chemical biology. 2016;12(2):109–16. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seashore-Ludlow B, Rees MG, Cheah JH, Cokol M, Price EV, Coletti ME, et al. Harnessing Connectivity in a Large-Scale Small-Molecule Sensitivity Dataset. Cancer discovery. 2015;5(11):1210–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberlick EM, Rees MG, Seashore-Ludlow B, Vazquez F, Nelson GM, Dharia NV, et al. Small-Molecule and CRISPR Screening Converge to Reveal Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Dependencies in Pediatric Rhabdoid Tumors. Cell reports. 2019;28(9):2331–44 e8. Epub 2019/08/29. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aguirre AJ, Meyers RM, Weir BA, Vazquez F, Zhang CZ, Ben-David U, et al. Genomic Copy Number Dictates a Gene-Independent Cell Response to CRISPR/Cas9 Targeting. Cancer discovery. 2016;6(8):914–29. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howard TP, Arnoff TE, Song MR, Giacomelli AO, Wang X, Hong AL, et al. MDM2 and MDM4 are Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors. Cancer research. 2019. Epub 2019/02/14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(43):15545–50. Epub 2005/10/04. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic acids research. 2017;45(D1):D353–D61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chun HE, Lim EL, Heravi-Moussavi A, Saberi S, Mungall KL, Bilenky M, et al. Genome-Wide Profiles of Extra-cranial Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors Reveal Heterogeneity and Dysregulated Developmental Pathways. Cancer cell. 2016;29(3):394–406. Epub 2016/03/16. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Wang S, Troisi EC, Howard TP, Haswell JR, Wolf BK, et al. BRD9 defines a SWI/SNF sub-complex and constitutes a specific vulnerability in malignant rhabdoid tumors. Nature communications. 2019;10(1):1881 Epub 2019/04/25. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart E, Federico S, Karlstrom A, Shelat A, Sablauer A, Pappo A, et al. The Childhood Solid Tumor Network: A new resource for the developmental biology and oncology research communities. Dev Biol. 2016;411(2):287–93. Epub 2015/06/13. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483(7391):603–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jane-Valbuena J, Kryukov GV, Lo CC, McDonald ER 3rd, et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature. 2019;569(7757):503–8. Epub 2019/05/10. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chauvin C, Leruste A, Tauziede-Espariat A, Andrianteranagna M, Surdez D, Lescure A, et al. High-Throughput Drug Screening Identifies Pazopanib and Clofilium Tosylate as Promising Treatments for Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors. Cell reports. 2017;21(7):1737–45. Epub 2017/11/16. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart E, Goshorn R, Bradley C, Griffiths LM, Benavente C, Twarog NR, et al. Targeting the DNA repair pathway in Ewing sarcoma. Cell reports. 2014;9(3):829–41. Epub 2014/12/02. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin S, Wang R, Zhou F, Zhang H, Jing Y. Bcl-xL is a dominant antiapoptotic protein that inhibits homoharringtonine-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Molecular pharmacology. 2011;79(6):1072–83. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ouchi K, Kuwahara Y, Iehara T, Miyachi M, Katsumi Y, Tsuchiya K, et al. A NOXA/MCL-1 Imbalance Underlies Chemoresistance of Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor Cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 2016;231(9):1932–40. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.