Abstract

We previously reported that eBAT, an EGF-targeted angiotoxin, was safe and improved overall survival for dogs with splenic hemangiosarcoma when added to the standard of care in a single cycle of three administrations in the minimal residual disease setting. Our objective for the SRCBST-2 trial was to assess whether increased dosing through multiple cycles of eBAT would be well tolerated and further enhance the benefits of eBAT. Eligibility was expanded to dogs with stage-3 hemangiosarcoma, provided that gross lesions could be surgically excised. The interval between eBAT and the start of chemotherapy was reduced, and the experimental therapy was expanded to three cycles, each administered at the biologically active dose (50 μg/kg) on a Monday/Wednesday/Friday schedule following splenectomy, and scheduled one week prior to the 1st, 2nd, and 5th doxorubicin chemotherapy. Twenty-five dogs were enrolled; six experienced acute hypotension with two requiring hospitalization. Self-limiting elevation of ALT was observed in one dog. A statistically significant survival benefit was not seen in this study in eBAT-treated dogs compared to a Contemporary comparison group of dogs with stages 1–3 hemangiosarcoma treated with standard of care alone. Our results indicate that repeated dosing cycles of eBAT starting one week prior to doxorubicin chemotherapy led to greater toxicity and reduced efficacy compared to a single cycle given between surgery and a delayed start of chemotherapy. Further work is needed to understand the precise mechanisms of action of eBAT in order to optimize its clinical benefits in the treatment of canine hemangiosarcoma and other tumors.

Keywords: targeted toxin, epidermal growth factor receptor, urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, sarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, canine

1. INTRODUCTION

Targeted toxins have emerged as promising agents that can target growth factor pathways with reduced toxicity. They are specifically designed to target receptors that are uniquely or highly expressed by cancer cells, improving tumor specificity and reducing the likelihood of adverse events. Bispecific targeted toxins have dual targeting ability that confers greater binding affinity and increased killing ability compared to their monospecific counterparts.1 The potency and specificity of bispecific toxins have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo against a variety of malignancies, including sarcomas.2–12

eBAT is a bispecific epidermal growth factor (EGF) angiotoxin developed as a targeted, second generation biologic drug to specifically target tumor cells and associated tumor neo-vasculature for sarcoma therapy. It consists of human EGF, targeting the EGF receptor (EGFR), expressed by a variety of tumors,1 human amino terminal transferase (ATF) of urokinase, targeting the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), and a genetically modified, de-immunized Pseudomonas exotoxin, leading to inhibition of protein synthesis. uPAR is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell surface protein associated with tumor invasion, migration and metastasis4,13 It is expressed on both the tumor cell surface and possibly the associated neovasculature, making it an attractive therapeutic target.4,7

Canine HSA is an incurable malignancy originating from blood vessel forming cells that is morphologically similar to human angiosarcoma. Median survival for people affected by angiosarcoma is about 16 months,14 which is comparable to the reported median survival of 4–6 months for dogs with HSA.15,16 In addition to its comparative aspects, several factors render HSA a good model for testing of eBAT: 1) co-expression of EGFR and uPAR has been shown in canine putative hemangiosarcoma stem cells and these cells are highly sensitive to eBAT-mediated cell killing;2 2) in vivo vascular structures resemble tortuous neo-angiogenic blood vessels, providing an excellent platform for simultaneous targeting of the tumor and its vasculature;7,17 and 3) while angiosarcoma occurs rarely in people, HSA is common in dogs, providing a unique opportunity to investigate a novel therapy in a realistic clinical setting.3

In the SRCBST-1 (sarcoma bispecific toxin trial-1) study, we found that eBAT was safe and potentially effective against canine splenic hemangiosarcoma (HSA) when administered post-splenectomy in one cycle of therapy of three treatments given on a Monday, Wednesday, Friday basis, followed by a delayed start of standard doxorubicin chemotherapy.3 An extremely important, albeit unexpected finding during SRCBST-1 was that eBAT did not cause any of the dose-limiting toxicities typically associated with EGFR targeting in humans.3 The biologically active dose (BAD) was determined to be 50 μg/kg intravenously. Notably, eBAT improved 6-month survival from <40% in a historical comparison population to approximately 70% in the eBAT-treated dogs. Six of the 23 dogs enrolled in SRCBST-1 lived >450 days. Nevertheless, approximately half of the dogs eventually developed metastatic disease, suggesting that modifications of dosing and/or dosing schedules may be needed to further improve clinical benefit. Studies with Pseudomonas exotoxin in humans have suggested that repeat cycles of administration may prolong remissions whereas the timing of treatment with targeted toxins used in conjunction with chemotherapy is unclear.18,19 The SRCBST-2 (sarcoma bispecific toxin trial-2) study described herein was undertaken to determine if multiple cycles of eBAT at the biologically active dose (50 μg/kg) given at a reduced interval from doxorubicin chemotherapy would be well-tolerated and further improve the outcome of dogs with splenic HSA.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. eBAT manufacturing

eBAT was produced at the University of Minnesota cGMP Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics (MCT) Facility as previously described.7 Release assays were performed by Pace Analytical Life Sciences, LLC (Minneapolis, MN) and/or at the MCT using previously reported release criteria of drug purity (>95%), endotoxin (<50 Eu/mg), stability, selectivity, potency (IC50<1.0 nM), sterility, and concentration.3 The drug was vialed and re-tested to meet all FDA specifications. Stability and potency were evaluated and confirmed during the study and at the end of the study.

2.2. Canine clinical study (SRCBST-2)

2.2.1. Variables changed from SRCBST-1 to SRCBST-2

The SRCBST-2 clinical study was designed to incorporate multiple cycles of therapy, where one cycle included three eBAT treatments spaced every other day over a 5-day period. eBAT was administered to dogs with spontaneous HSA after splenectomy and before the first, second, and fifth (last) cycle of doxorubicin chemotherapy. This is different from SRCBST-1 where only one cycle of eBAT was administered before the first doxorubicin treatment. While a dose escalation protocol was employed in SRCBST-1 to identify a biologically active dose (BAD), all dogs enrolled in SRCBST-2 were treated at the BAD (50 μg/kg/day). Eligibility was expanded from dogs with stage-1 or stage-2 splenic HSA (as in SRCBST-1) to dogs with stage-3 disease as long as macroscopic metastatic lesions could be surgically resected to achieve minimal residual disease (MRD). This was done to determine if a signal of efficacy could be detected at higher stages of disease. Acknowledging that formal quantification of MRD was not performed in this study, the term MRD is used throughout the manuscript to indicate the absence of macroscopic lesions and presumed residual microscopic disease in canine patients with splenic HSA following splenectomy.

Lastly, the interval between the administration of eBAT and commencement of doxorubicin chemotherapy was reduced with doxorubicin starting on day 8 instead of day 21 to improve compliance and efficiency, under the presumption that increasing the intensity of the protocol would translate into greater efficacy.

2.2.2. Description of the SRCBST-2 clinical study

SRCBST-2 was conducted with approval and oversight of the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Protocols 1110A06186 and 1507–32804A). Study design and implementation conformed to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines as they apply to studies in companion animals.20

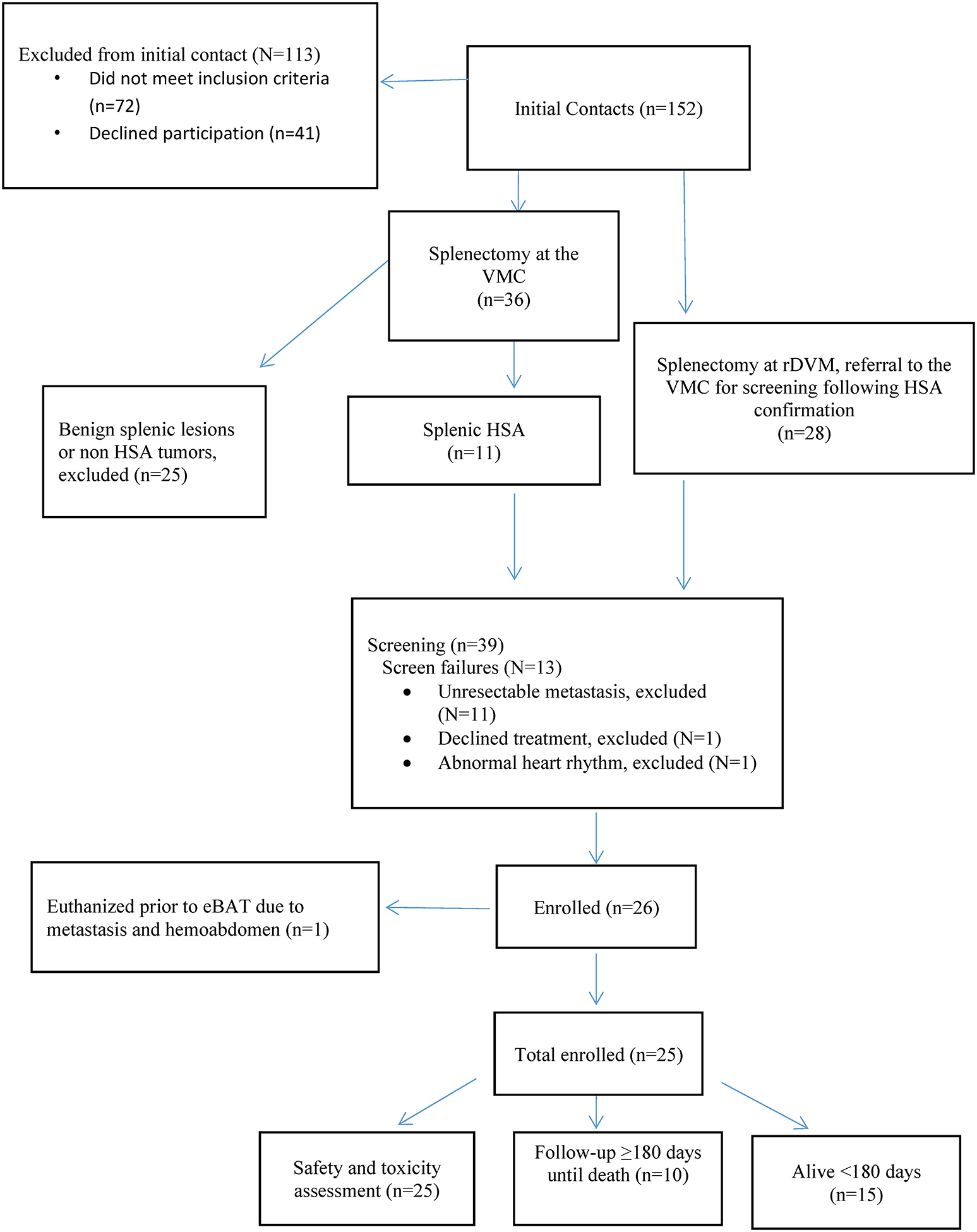

A CONSORT diagram showing the flow of study participants is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for SRCBST-2 study

Inclusion criteria included histopathologically-confirmed diagnosis of stage-1 (no evidence of tumor rupture) or stage-2 (evidence of tumor rupture) or stage 3 (metastatic) splenic HSA; evidence of regional or distant metastatic disease based on thoracic radiography and abdominal ultrasonography was permitted as long as lesions were amenable to surgical resection; no concurrent treatment with herbal treatments or supplements; performance score of 0 or 1 according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scale;21 adequate organ function; no serious comorbidities, such as renal or hepatic failure, congestive heart failure, or clinical coagulopathy.

Dogs were required to have a splenectomy prior to study entry. Each dog received a baseline complete history, physical examination, and laboratory testing that included a complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemical profile, coagulation parameters (prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time), and urinalysis. Thoracic radiography and abdominal ultrasonography were performed prior to enrollment. eBAT was administered in multiple cycles, each consisting of three intravenous treatments at the biologically active dose of 50 μg/kg/day. Pre-loading with intravenous fluids was done at a rate of 0.1–1 ml/kg/hr for 10 to 60 minutes depending on size of the dog. The drug was administered as a slow infusion over 5–20 minutes depending on volume and size of the dog.

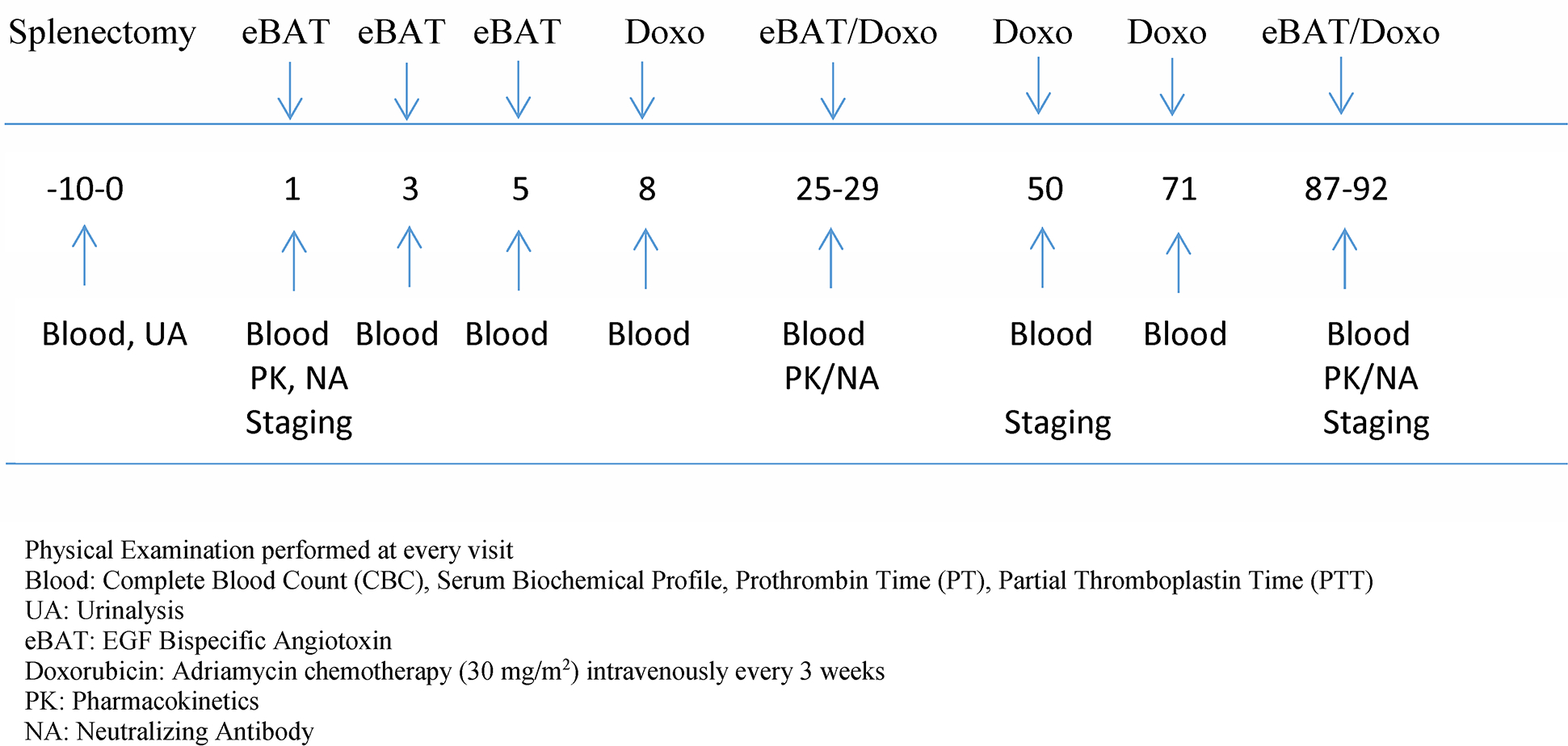

The first cycle was given on days 1, 3, and 5 of the week prior to the first doxorubicin administration. The two additional eBAT cycles were given in the weeks prior to the 2nd and 5th doxorubicin administrations, with the 3rd eBAT treatment in each of these cycles administered on the same day as doxorubicin chemotherapy. The study protocol is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study Protocol Timeline. Numbers indicate days of sample collection, staging and treatment. eBAT starts on Day 1 and is given prior to the 1st, 2nd, and 5th cycle of doxorubicin chemotherapy.

Disease reassessment included physical examination, blood and urine evaluation, thoracic radiography and abdominal ultrasonography prior to doxorubicin treatments # 3 and # 5. No medications were prescribed or administered concurrently, unless needed to manage toxicity or other, unrelated medical conditions. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to VCOG-CTCAE criteria.22 Adverse events related to the study drug or to doxorubicin chemotherapy were treated with supportive care, as needed. Gastrointestinal toxicities were managed with famotidine, omeprazole, metronidazole, metoclopramide, ondansetron, and/or maropitant. Antibiotic therapy was allowed for prophylaxis in the event of grade 3 or grade 4 neutropenia, or febrile neutropenia. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other analgesics (tramadol, gabapentin) were allowable for pain control as needed.

A historical comparison group (Comparison group), partially overlapping with the comparison group used in SRCBST-1, consisted of 35 dogs with stage-I (5 dogs), stage-II (23 dogs), or stage-III (7 dogs) HSA treated with SOC alone (surgery followed by adjuvant doxorubicin-based chemotherapy protocols) at the Veterinary Medical Center (VMC) between 2005 and 2018.

Owners of each dog gave written informed consent to treat prior to study entry. All dogs were treated at the University of Minnesota Veterinary Medical Center (VMC); the study was managed by the Clinical Investigation Center (CIC) of the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota in compliance with principles of Good Clinical Practice.23

2.3. eBAT Pharmacokinetics and Neutralizing Antibody Assays

Serum samples were collected before eBAT treatment (time 0) and 5, 15, and 30 minutes after the end of the infusion on days 1 and 25 to measure drug pharmacokinetics (PK). Baseline serum samples collected on days 1, 25, and 92, when available, were also used to assess the presence of neutralizing antibodies (NAs). A bioassay with human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells was used to measure eBAT PK, as reported.3 Cell authentication and Mycoplasma testing (confirmed negative for all strains) were conducted at IDEXX Bioresearch (Columbia, MO). Cells were incubated overnight prior to addition of the clinical batch eBAT. Proliferation was measured after 72 hours using a 3H-leucine assay. The presence of eBAT in serum was extrapolated from the standard curve as reported.19 The presence of NAs was inferred from the capacity of serum samples to block cell death caused by reference eBAT.3,12

2.4. Statistical analysis

The study was designed as a one-arm trial. For our statistical analysis, we provide summary statistics of baseline characteristics and study outcomes for the eBAT group, and provide formal comparisons with the historical comparison group (Comparison group) described above. Baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics and compared between eBAT-treated dogs and the Comparison group using the Chi-square or Fishers Exact test for categorical variable comparisons, and ANOVA for continuous variable comparisons. Adverse events associated with eBAT administration were recorded and summarized. The impact of NAs on outcome was evaluated using summary statistics. The primary survival outcome was time until HSA-related mortality. Survival time for all dogs was measured from the date of diagnosis to the time of death and was censored at the time of last contact for dogs surviving at the time of analysis. Dogs that died for reasons other than HSA were censored at the time of death. Kaplan Meier plots were used to summarize survival times and the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compare HSA-related survival between groups univariately and when adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, hemoabdomen (yes/no), weight in kilograms, days from splenectomy to chemotherapy, anemia at diagnosis, and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis. Given that multiple analyzers were used at different practices at diagnosis, “anemia” and “thrombocytopenia” were defined as values below individual respective reference ranges for hematocrit and platelets, respectively. The eBAT group had only one dog with stage I HSA and one dog with stage III disease; as a result, the estimated coefficient for stage was unstable and stage was not included in the model. All hazard ratios (HR) are presented with their 95% confidence interval (CI). Cause of death was unknown for 5 dogs in the eBAT group and 6 dogs in the Comparison group. We completed two analyses, one assuming that the cause of death for these dogs was HSA-related and one assuming that the cause of death for these dogs was not related to HSA, to evaluate the robustness of our conclusions to missing data. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Subjects

The investigators were in contact with 152 families via email or telephone to assess their dog’s eligibility to participate in SRCBST-2. Of these, 39 dogs were presented to Veterinary Medical Center for screening and 25 of these dogs met the criteria for enrollment in the study. Staging diagnostics were performed at the VMC in 22 of 25 enrolled cases, and at the referral Institution in the remaining 3 cases. All staging diagnostics were completed within a week prior to starting eBAT. Restaging diagnostics were performed prior to the 3rd and 5th doxorubicin treatment at the VMC in all cases except for two patients where restaging was completed prior to the 3rd doxorubicin at the referral Institution. Any imaging diagnostics performed at referral Institutions required interpretation by a board-certified radiologist. All eBAT treatments were administered exclusively at the University of Minnesota VMC; doxorubicin treatments were administered at the VMC in 19 cases, an outside facility in 2 cases, and a combination of the two in 3 cases. Of the dogs enrolled, one died due to complications from an inadvertent doxorubicin overdose given at the referring veterinarian’s clinic, another died due to complications from a dog fight, and one dog with stage II disease did not receive doxorubicin due to rapid disease progression. The analyses presented below include all 25 dogs; a sensitivity analysis without the three dogs described above showed results consistent with those reported in Section 3.3 (data not shown).

Baseline characteristics for dogs treated with eBAT and the comparison dogs are summarized in Table 1. Although the SRCBST-2 study allowed for the inclusion of Stage III HSA cases, only one was enrolled. The mean age in the eBAT-treated group was lower than the Comparison group (Mean±Standard deviation [SD]: 8.6±2.3 and 10.1±2.3 years respectively; p=0.018). The eBAT group also had a longer time between splenectomy and the initiation of chemotherapy (Mean±SD: 30.3±8.2 and 19.9±5.7 days respectively; p<0.0001). The most common laboratory abnormalities at the time of diagnosis and before splenectomy included mild to moderate anemia (13 dogs), thrombocytopenia (13 dogs), and mild leukocytosis (11 dogs), with some dogs showing more than one abnormality.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for dogs treated with eBAT and Comparison group

| eBAT-treated | Comparison group | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | Mean ± SD or n (%) | ||

| Number of Dogs | 25 | 35 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 8.6 ± 2.3 | 10.1 ± 2.3 | 0.018 |

| Sex (male) | 18 (72.0) | 19 (54.3) | 0.164 |

| Hemoabdomen | 22 (88.0) | 29 (82.9) | 0.722 |

| Stage III | 1 (4.0) | 7 (20.0) | |

| Weight (kilograms) | 30.5 ± 11.5 | 28.1 ± 11.3 | 0.425 |

| Body Condition Score (BCS) | 5.4 ± 0.8 | Not collected | NA |

| Days between splenectomy and chemotherapy | 30.3 (8.2) | 19.9 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

| Anemia | 13 (52.0) | 26 (78.8) | 0.048 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 13 (52.0) | 22 (73.3) | 0.159 |

| The P-value column is for the comparison between treatment groups. Chi-Square or Fishers Exact Test for categorical variables, ANOVA for continuous variables. | |||

BCS was not available in the records for dogs in the comparison group; breeds enrolled in the study included 8 Golden retrievers, 4 Labrador retrievers, 3 German Shepherd Dogs, 2 Boxers, and 1 each Mastiff, Great Dane, Boston terrier, Bichon frise, Pembroke Welsh Corgi, German short hair pointer, Flat coated retriever, mixed breed dog.

Chemotherapy in the Comparison group consisted of doxorubicin chemotherapy in 10 dogs, and doxorubicin chemotherapy combined with metronomic cyclophosphamide in 25 dogs. In one of these 25 dogs, metronomic chlorambucil was used to replace cyclophosphamide following the development of sterile hemorrhagic cystitis.

3.2. Multiple cycles of eBAT lead to increased incidence and severity of adverse events

A summary of the most severe adverse event for each dog in SRCBST-2 is shown in Table 2. Six dogs experienced hypotensive events that required a short-term hospitalization in two cases, one dog had self-limiting grade 4 alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation, one dog had a seizure episode mid-treatment, and three dogs experienced vomiting episodes. Facial edema and reddened skin, ears with swelling of the lips were noted in two dogs, respectively. A hypersensitivity reaction was suspected in these two dogs and treatment with diphenhydramine was instituted. One dog also received a single dexamethasone injection.

Table 2.

Description of eBAT-related adverse events

| Dog ID | Breed | eBAT Toxicity Grade | Cycle of AE Occurrance | eBAT Toxicity Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MN28 | Pembroke Welsh Corgi | 4 | Cycle # 2 (1st treatment) | ALT elevation eBAT discontinued |

| MN40 | Golden Retriever | 3 | Cycle # 2 (1st treatment) | hypotension+hospitalization (mid-treatment), vomiting, facial edema eBAT discontinued |

| MN35 | Great Dane | 3 | Cycle # 2 (1st treatment) | hypotension+hospitalization (mid-treatment), swelling of lips, reddening of ears and skin eBAT discontinued |

| MN45 | Golden Retriever | 2 | Cycle # 3 (1st treatment) | hypotension (mid-treatment) eBAT discontinued |

| MN30 | Golden Retriever | 2 | Cycle # 1 (3rd treatment) | hypotension (mid-treatment) |

| MN31 | Labrador Retriever | 2 | Cycle # 1 (3rd treatment) | hypotension (mid-treatment), nausea |

| MN32 | Labrador Retriever | 2 | Cycle # 2 (1st treatment) | seizure (mid-treatment) |

| MN49 | Labrador Retriever | 2 | Cycle # 2 (1st treatment) | vomiting and diarrhea (post-treatment, same day) |

| MN27 | Golden Retriever | 2 | Cycle # 2 (1st treatment) | vomiting/hypotension (mid-treatment) |

Twelve of the 25 enrolled dogs completed three planned cycles of eBAT; seven dogs completed two cycles, five dogs completed one cycle; one dog did not complete the initial cycle due to progressive disease prior to the third treatment. Reasons for not completing three cycles of eBAT included disease progression in eight dogs, accidental chemotherapy overdose at the referring veterinarian’s office in one dog, and eBAT-induced adverse events in four dogs. In most cases (6 out of nine), an adverse event occurred at the time of the 1st treatment of the second eBAT cycle, resulting in discontinuation of eBAT in 3 of these cases.

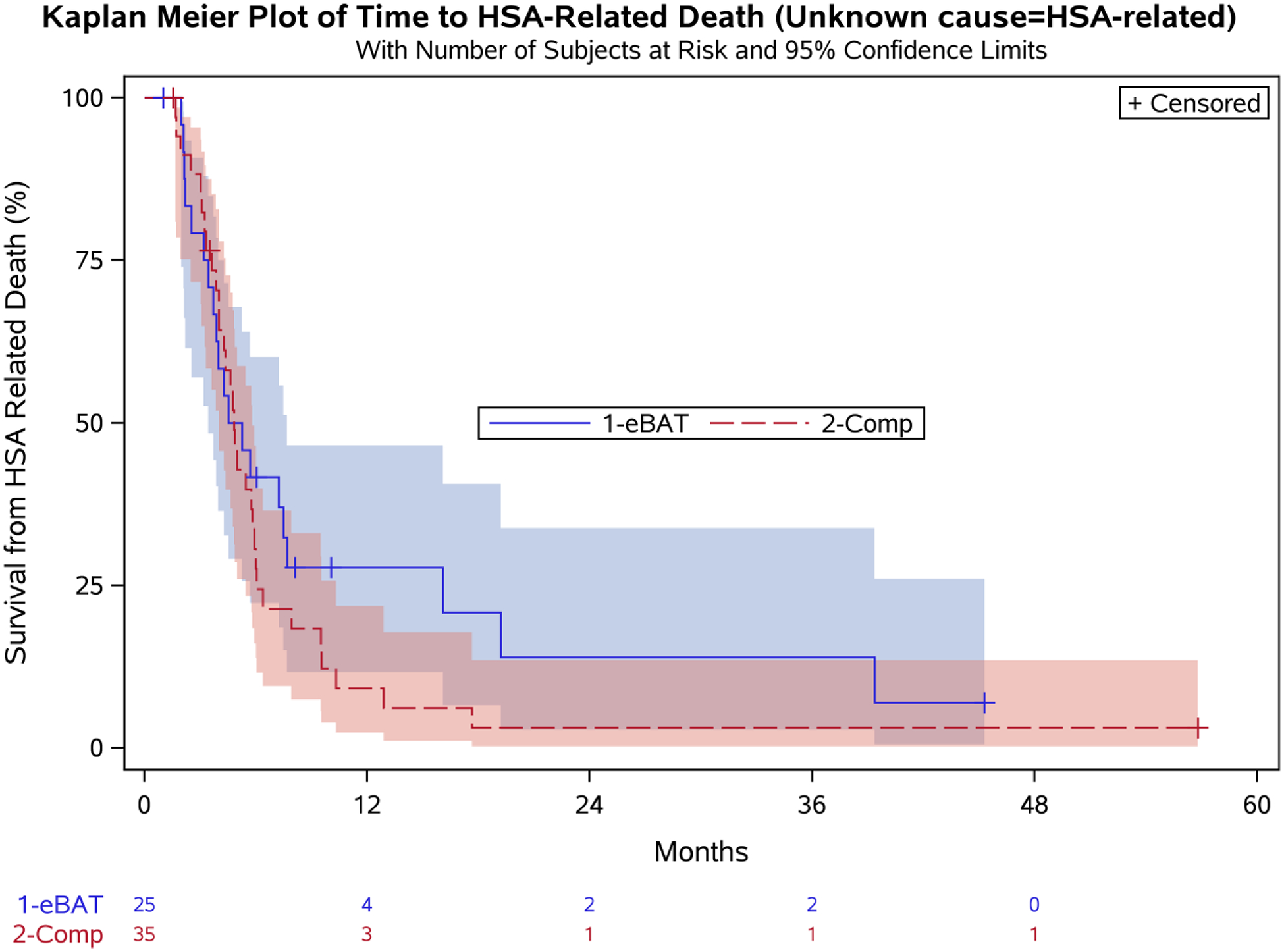

3.3. eBAT does not provide a statistically significant survival benefit when given in multiple cycles

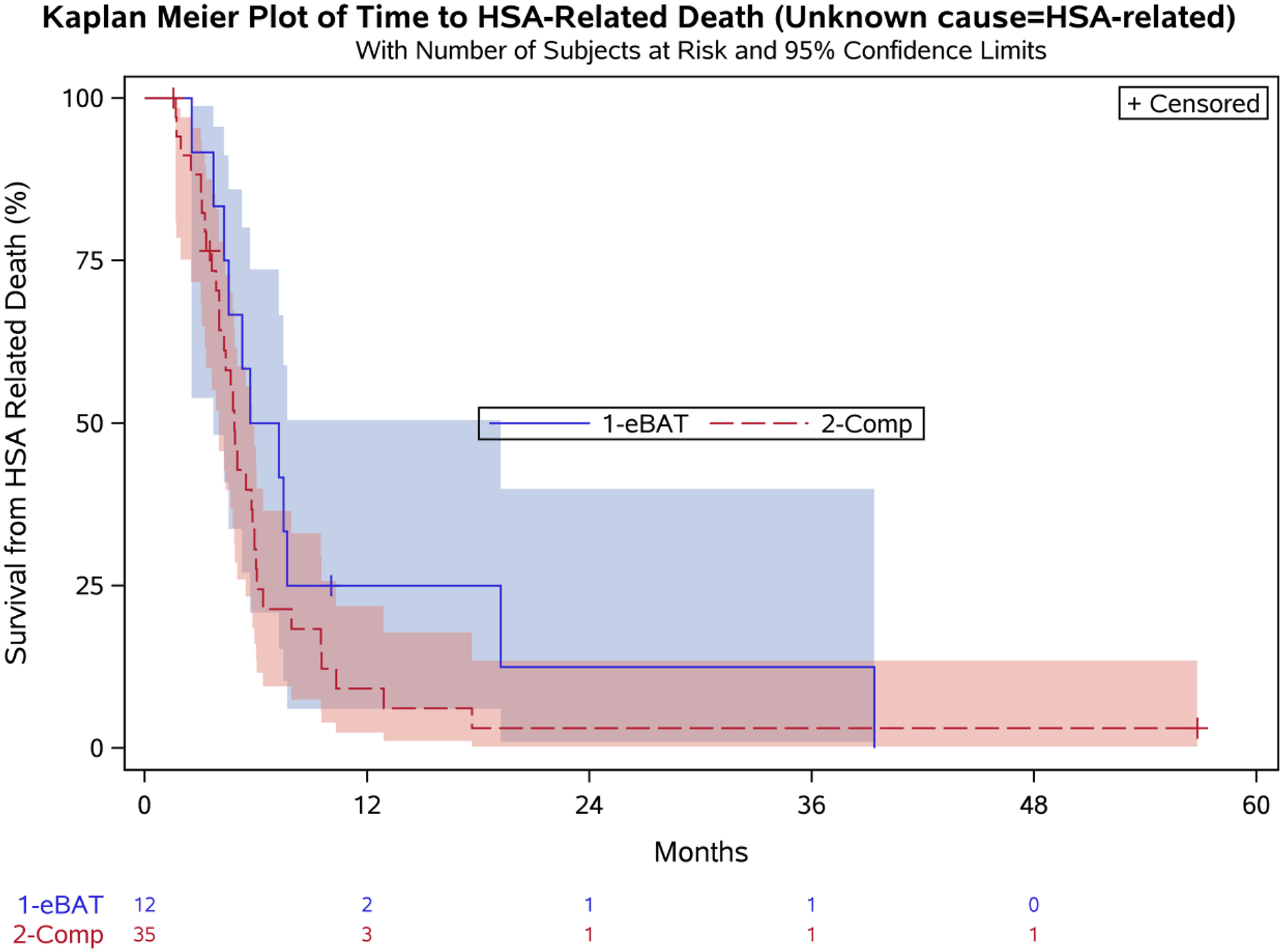

There were eleven dogs (five eBAT-treated and six Comparison group) for whom the relationship between HSA and the cause of death could not be ascertained; these deaths were treated as related to HSA in the analysis of HSA-related survival. The median survival was 4.9 months in the 25 dogs enrolled in SRCBST-2 (95% CI: 3.4, 7.7) and 4.8 months in the Comparison group treated with standard of care alone (95% CI: 4.0, 5.8) (Figure 3). Univariable and multivariable model results are shown in Table 3. The hazard ratio for treatment (defined as increased risk of death incurred by being an eBAT case) was not significant (HR=1.32 [95% CI: 0.60, 2.91]; p=0.489). An increased risk of death from HSA was associated with higher age (per 1-year increase: HR=1.33 [95% CI: 1.12, 1.58], p=0.001) and the presence of hemoabdomen (HR=1.87 [95% CI: 0.95, 3.69], p=0.033). Six-month survival rates were 41.7% (95% CI: 22.2, 60.1) for the eBAT-treated group and 30.6% (95% CI: 16.0, 46.4) for the Comparison group (Table 4).

Figure 3. Effect of multiple cycles of eBAT on survival of dogs with splenic HSA treated with adjuvant doxorubicin chemotherapy when unknown cause of death was considered to be related to HSA.

Kaplan-Meier Curve for all 25 dogs in the SRCBST-2 study versus the comparison dogs. Unknown cause of death in 11 cases (5 eBAT treated and 6 in the Comparison Group) was treated as related to HSA.

Table 3.

Survival analysis: Univariable and Multivariable Cox Regression Model Results

| Unknown Death Cause Treated as RELATED to HSA | Unknown Death Cause Treated as UNRELATED to HSA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable* | Univariable | Multivariable* | |

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) P-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) P-value |

| Treatment (eBAT vs. Comparison group) | 0.74 (0.42, 1.31) p=0.308 | 1.32 (0.60, 2.91) p=0.489 | 0.72 (0.38, 1.37) p=0.322 | 1.66 (0.65, 4.29) p=0.291 |

| Age at diagnosis (per 1 year increase) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33) p=0.004 | 1.33 (1.12, 1.58) p=0.001 | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) p=0.082 | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) p=0.095 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.40 (0.80, 2.45) p=0.243 | 1.87 (0.95, 3.69) p=0.068 | 1.36 (0.72, 2.55) p=0.341 | 1.68 (0.77, 3.63) p=0.189 |

| Hemoabdomen (yes vs. no) | 1.37 (0.61, 3.04) p=0.444 | 3.84 (1.11, 13.22) p=0.033 | 1.49 (0.58, 3.82) p=0.402 | 2.55 (0.63, 10.29) p=0.187 |

| Weight (per 1 kg increase) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) p=0.220 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) p=0.547 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) p=0.322 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) p=0.274 |

| Days from splenectomy to chemotherapy (per 1 day increase) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) p=0.853 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) p=0.458 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) p=0.194 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) p=0.103 |

| Anemia (yes vs. no) | 1.67 [0.90,3.13] p=0.106 | 0.65 (0.27, 1.55) p=0.335 | 2.38 (1.09, 5.21) p=0.030 | 1.17 (0.40, 3.41) p=0.778 |

| Thrombocytopenia (yes vs. no)* | 1.87 [1.01,3.47] p=0.047 | 1.59 (0.62, 4.04) p=0.334 | 2.31 (1.10, 4.84) p=0.027 | 1.62 (0.55, 4.78) p=0.378 |

5 comparison group dogs did not have platelets measured and therefore could not be included in the multivariable models or the univariable analysis of thrombocytopenia (total N=55).

Table 4.

Median survival and survival estimates at 6 month intervals for all eBAT-treated dogs, the twelve eBAT-treated dogs completing all three drug cycles, and the Comparison group. The estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals.

| Unknown Death Cause Treated as RELATED to HSA | Unknown Death Cause Treated as UNRELATED to HSA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eBAT (N=25 - all pts) | eBAT subset (N=12 completing all 3 eBAT cycles) | Comparison group (N=35) | eBAT (N=25 - all pts) | eBAT subset (N=12 completing all 3 eBAT cycles) | Comparison group (N=35) | |

| Median survival (months) | 4.9 (3.4, 7.7) | 6.5 (3.7, 19.2) | 4.8 (4.0, 5.8) | 7.2 (3.9, 19.2) | 7.5 (4.3, 19.2) | 4.9 (4.0, 7.9) |

| 6-mos (%) | 41.7 (22.2, 60.1) | 50.0 (20.8, 73.6) | 30.6 (16.0, 46.4) | 50.6 (28.7, 69.0) | 63.6 (29.7, 84.5) | 41.6 (24.6, 57.9) |

| 12-mos (%) | 27.8 (11.7, 46.6) | 25.0 (6.0, 50.5) | 9.2 (2.3, 21.8) | 33.8 (14.6, 54.1) | 31.8 (7.8, 59.8) | 14.3 (3.9, 31.2) |

| 18-mos (%) | 20.8 (6.5, 40.6) | 25.0 (6.0, 50.5) | 3.0 (0.2, 13.5) | 33.8 (14.6, 54.1) | 31.8 (7.8, 59.8) | 9.5 (1.7, 25.5) |

| 24-mos (%) | 13.9 (2.7, 33.8) | 12.5 (0.9, 39.9) | 3.0 (0.2, 13.5) | 22.5 (5.3, 46.9) | 15.9 (1.1, 47.5) | 9.5 (1.7, 25.5) |

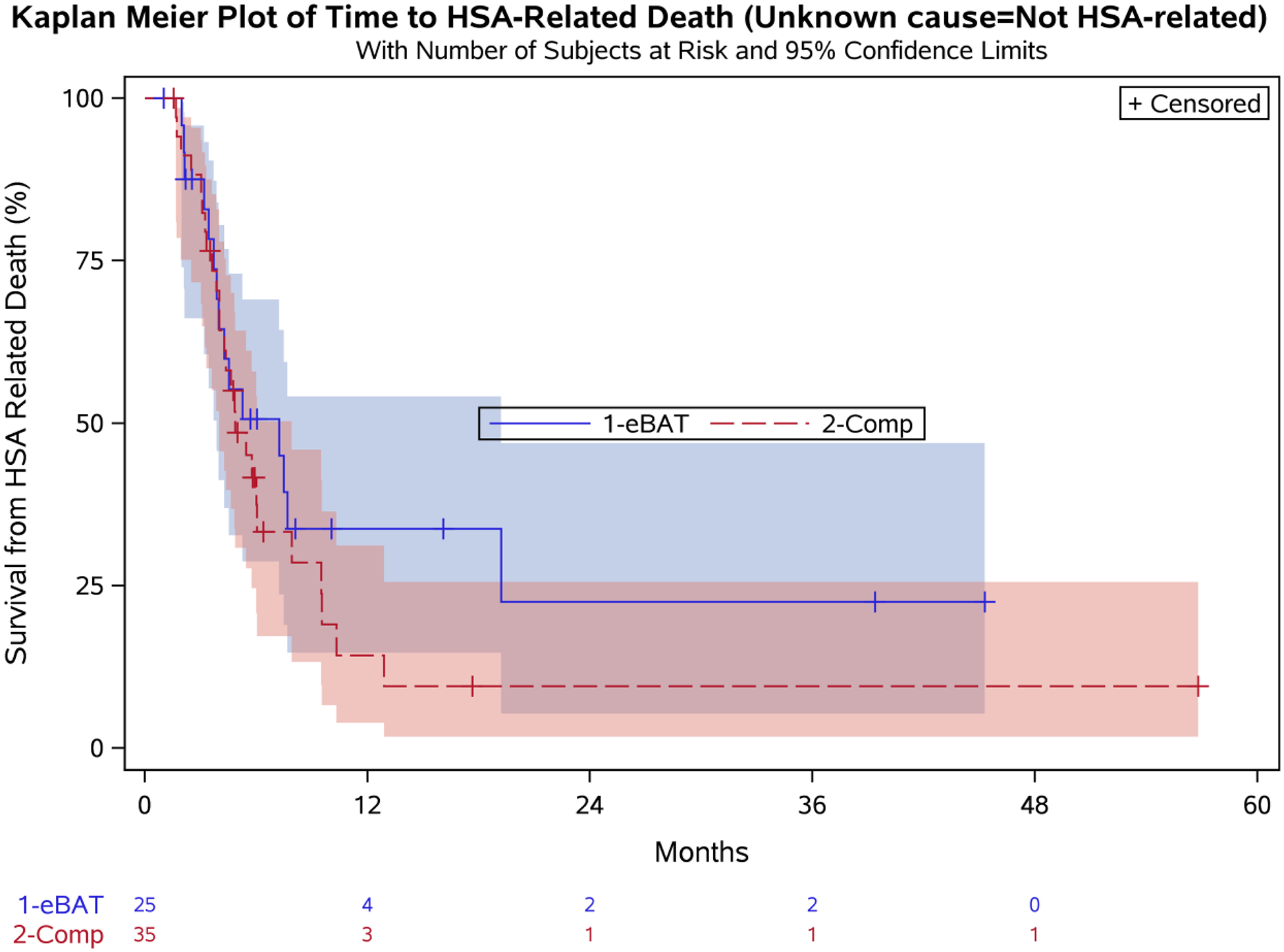

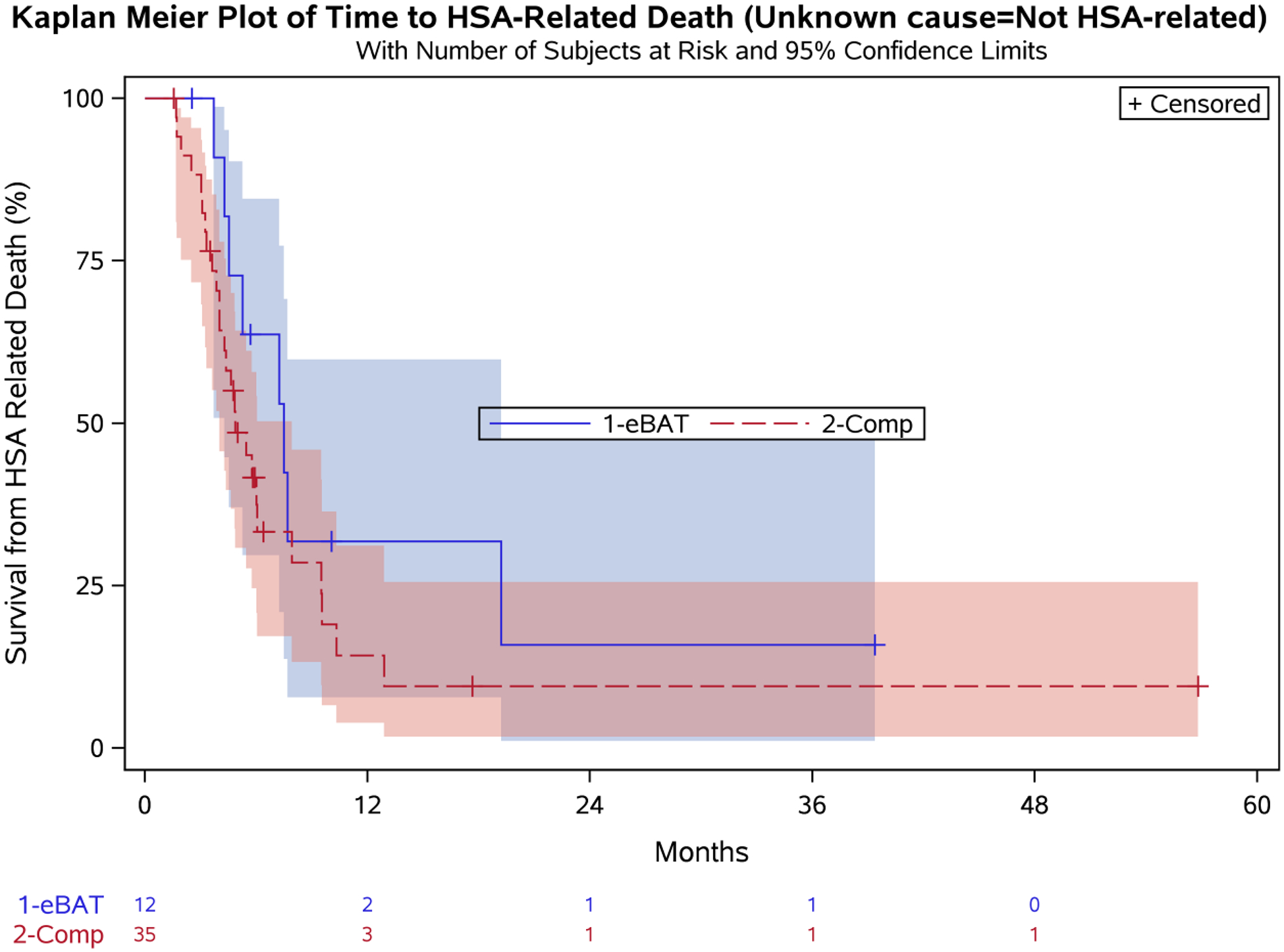

To confirm the lack of a significant survival advantage, we repeated the analysis considering unknown cause of death (N=11) as unrelated to HSA. Median survival for the 25 enrolled dogs was 7.2 months (95% CI: 3.9, 19.2) compared to 4.9 months (95% CI: 4.0, 7.9) for the Comparison group (Figure 4). The hazard ratio for treatment (defined as increased risk of death incurred by being an eBAT case) was again not significant (HR=1.66 [95% CI: 0.65, 4.29]; p=0.291). Six-month survival rates were 50.6% (95% CI: 28.7, 69.0) for the eBAT-treated group and 41.6% (95% CI: 24.6, 57.9) for the Comparison group (Table 4).

Figure 4. Effect of multiple cycles of eBAT on survival of dogs with splenic HSA treated with adjuvant doxorubicin chemotherapy when unknown cause of death was considered to be unrelated to HSA.

Kaplan-Meier Curve for all 25 dogs in the SRCBST-2 study versus the comparison dogs. Unknown cause of death in 11 cases (5 eBAT-treated and 6 in the Comparison Group) was treated as unrelated to HSA.

Twelve dogs completed all three planned cycles of eBAT. To determine if treatment completion provided a survival benefit, we performed similar analyses to include this patient population considering unknown cause of death as related to HSA (Figure 5A) or unrelated to HSA (Figure 5B). Median survival for the 12 dogs that completed 3 eBAT cycles was 6.5 months (95% CI: 3.7, 19.2) when unknown cause of death was considered related to HSA, and 7.5 months (95% CI: 4.3, 19.2) when unknown cause of death was considered unrelated to HSA.

Figure 5. Effect of eBAT on survival of dogs that completed 3 cycles of therapy when unknown cause of death was considered to be related to HSA (A) or unrelated to HSA (B).

Kaplan-Meier Curve for 12 dogs in the SRCBST-2 study that completed all planned eBAT cycles of therapy versus the Comparison Group.

3.4. Neutralizing Antibody (NA) to eBAT were observed and did not impact outcome

To determine if immunogenicity interferes with bioactivity, we screened serum samples for NA from all dogs at baseline. One dog had pre-existing antibody against eBAT. Samples for NA measurement were available for 16/25 dogs (64%) on Day 25 (prior to the second cycle of eBAT administration) and 6/25 dogs (24%) on Day 92 (prior to the third cycle of eBAT). NAs were detected in 14/16 dogs (87%) on Day 25 and in all 6 dogs on Day 92.

Drug was not detectable in circulation in the dog with pre-existing NAs against eBAT. Dogs in which we could detect drug in the circulation on Day 1 (N=11) had similar survival to dogs in which drug was undetectable (N=14): median survival was 4.5 months (95% CI: 2.1, 7.7) versus 5.3 months (95% CI: 3.2, 39.4) respectively, log-rank p=0.282; HR=1.66 [95% CI: 0.65, 4.26]. In all cases in which drug was detectable, drug was identified at 5 minutes post-dosing. The presence of detectable drug was not significantly associated with survival (p = 0.412) and, conditional on detectable drug, there was no association between AUC and survival (p = 0.865).

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to determine if multiple cycles of eBAT at the biologically active dose, in conjunction with standard of care would be well-tolerated and improve the outcome of dogs with splenic hemangiosarcoma in the microscopic disease setting. We showed that when eBAT was given in multiple cycles of therapy, the incidence and severity of adverse events directly related to the drug increased. In addition, repeated cycles of eBAT administered without a delay before starting chemotherapy did not seem to provide a significant survival benefit.

Hypotension was reported in our previous SRCBST-1 study, as well as in another study of human patients investigating treatment of advanced solid tumors with immunotoxin LMB-1, composed of monoclonal antibody B3 chemically linked to PE38, a genetically engineered form of Pseudomonas exotoxin. These events were transient and did not require fluids or pressor agents.3,10 While all six dogs experiencing hypotensive events in the SRCBST-2 study recovered, hospitalization and fluid therapy were needed in two cases. Both dogs were discharged from the hospital within 24 hours, but the owners elected discontinuation of eBAT therapy in both cases. eBAT was discontinued in two additional cases due to a hypotensive event and grade 4 ALT elevation, respectively. Interestingly, the majority of adverse events occurred at the time of the second cycle of administration, suggesting a cumulative toxicity of eBAT in treated patients. The cause for this finding remains unclear, but the fact that most dogs had developed NAs against eBAT by Day 25 (before the start of the second cycle) suggests a potential immunogenic response could have played a role. Notably, two dogs in the present study experienced signs associated with hypersensitivity reactions (facial edema, swelling of the lips, reddening of the skin and ears). In both cases, these signs occurred at the time of the 1st eBAT treatment of the 2nd administration cycle. None of the treated dogs experienced signs of capillary leak syndrome, the toxicity of greatest concern for immunotoxins, or adverse events typically associated with EGFR-targeted therapies.18, 24–26 This is in line with previous studies using eBAT in companion dogs with hemangiosarcoma as well as in in vivo mouse models of pediatric sarcomas,3,4 and suggests that the addition of the uPAR-directed ligand to an EGFR targeting molecule allowed eBAT to retain its ability to prevent EGFR-directed toxicity despite multiple cycles of therapy.

A previous study of anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin Moxetumomab Pasudotox in human patients with hairy cell leukemia showed durable, complete responses with repeated cycles of administration.19 In that study, the number of cycles required for achievement of a complete remission (CR) was 2–5 with a median of 3 cycles. Consolidation cycles were also administered to some patients achieving a CR. However, patients developing antibodies against the drug were not retreated; therefore, it is difficult to assess the impact of immunogenicity on tumor response and survival. NAs against eBAT were observed in study dogs following the first cycle of treatment. While an association between NAs and outcome was not detectable in this population, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that immunogenicity may have a negative influence on tumor response and survival in eBAT treated patients. If this is true, perhaps restricting administration of repeated cycles to patients that did not develop NAs could have potentially resulted in reduced toxicity and improved outcome. Logistically, this would have been difficult to accomplish since the time required for planning and NA assay completion would have delayed treatment with both eBAT and chemotherapy. It is also possible that a higher dose of eBAT could have overcome immunogenicity in some patients. In a previous study, one dog with pre-existing antibody against eBAT had detectable drug in circulation on Day 1.3 This dog was treated at a dose higher than the biologically active dose.

Eligibility was expanded to dogs with metastatic disease as long as lesions could be surgically resected, so that treatment could be administered in the MRD setting. Only one dog with stage-3 disease was enrolled in SRCBST-2. Therefore, the lack of a significant survival benefit cannot be explained by the inclusion of dogs with advance disease alone. Moreover, it seems unlikely that the inclusion of cases where cause of death was unknown influenced the outcome. When considering the worst-case, and possibly the most likely scenario that any unknown cause of death would be due to HSA, survival was similar between the eBAT-treated group and the Comparison group. As a sensitivity analysis, we also evaluated a scenario where any unknown cause of death was considered to be unrelated to HSA, and survival was comparable between the two groups. Furthermore, a significant survival advantage was not identified in the 12 dogs that completed all three planned cycles of eBAT. Studies evaluating further dose escalation will be necessary to identify an optimal dose, which might be different than the BAD of eBAT in patients with MRD as well as with metastatic and/or macroscopic disease.

Unlike SRCBST-1, where doxorubicin was administered on day 21 following one cycle of three treatments of eBAT given on days 1, 3, and 5, the interval between eBAT and doxorubicin administration was reduced in SRCBST-2 with doxorubicin starting on day 8 after the first eBAT cycle and coinciding with the third eBAT treatment on subsequent cycles. This variable was changed based on the presumption that a highly aggressive disease may be best treated with a similarly aggressive approach and that a shorter interval between eBAT and doxorubicin was likely to be well-tolerated given the remarkable safety profile of eBAT in our previous study.3 Here we showed that “more” eBAT does not appear to be better. Furthermore, it is possible, and even likely, that eliminating the two-week delay between the end of the first eBAT cycle and the administration of doxorubicin could have negatively impacted eBAT activity. In fact, the apparent high expression of uPAR in tumor-associated mononuclear inflammatory cells, in addition to tumor cells also raises the possibility that eBAT may act through a primary immune mechanism by attenuating or eradicating tumor associated macrophages and myeloid suppressor cells, which in turn removes a strong impetus for tumor formation and/or tumor progression.3,27–29 Based on this observation, it is conceivable that doxorubicin could have suppressed the immunomodulatory properties of eBAT, resulting in a reduced efficacy signal compared to SRCBST-1 where doxorubicin was administered three weeks after the first eBAT injection. As there are no data available regarding the effects of doxorubicin at standard veterinary dosing on the potential eBAT-induced immunomodulation, it is difficult to predict if changing the administration sequence of the two drugs by giving eBAT following doxorubicin rather than before would alter outcomes. Further studies will be needed to elucidate the impact of this potential protocol modification. Interestingly, the interval between splenectomy and chemotherapy was significantly longer in eBAT-treated dogs compared to the Comparison group. A similar finding was reported in the SRCBST-1 trial, but unlike SRCBST-1, where dogs starting chemotherapy later had a more favorable outcome, a statistical survival advantage was not observed in this study. This reduces the possibility that the improved outcome noted in SRCBST-1 was attributable to the selection of cases with longer survival, resulting in a potential response bias. Further studies will be needed to fully elucidate the mechanism of action of eBAT, understand how to optimize treatment dose and schedule, and identify patients that are most likely to benefit from this therapeutic strategy. Imaging studies in companion animal models and humans will be also required to illustrate the biodistribution of eBAT and identify sites of accumulation in tumor and non-tumor areas.

In conclusion, repeated cycles of adjuvant eBAT given closer in time to doxorubicin chemotherapy resulted in greater incidence and severity of adverse events and reduced efficacy compared to a single cycle of administration combined with delayed commencement of doxorubicin chemotherapy in dogs with HSA. The addition of an uPAR directed ligand to the EGFR targeting molecule abrogated the dose-limiting toxicities associated with EGFR targeting despite multiple cycles of therapy. Further studies are needed to identify patient populations that are most likely to benefit from this therapeutic strategy and optimize treatment dose and schedules. Given that EGFR and uPAR targets are invariably expressed in human sarcomas and carcinomas, future directions may also include testing of eBAT on a variety of EGFR and uPAR-expressing malignancies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the oncology clinicians and staff of the University of Minnesota Veterinary Medical Center for assistance with management of dogs participating in the study, and importantly, clients who allowed their pets to enroll in the study, and the dogs who made the study possible.

Funding

This work was supported by grant K01OD017242 (AB) from the Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health, grant AB15MN-002 from the National Canine Cancer Foundation (AB), a grant from the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota Sarcoma Translational Working Group (JFM, DAV, AB, JSK), Cancer Center Support Grant, P30 CA077598 (Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota), grant 1889-G from the AKC Canine Health Foundation (JFM), the US Public Health Service Grant R01 CA36725 awarded by the NCI and the NIAID, DHHS (DAV), the Randy Shaver Cancer Research and Community Foundation (DAV), Hyundai Scholar Senior Research Award, Hyundai Hope on Wheels (DAV), a CETI Translational Award from the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center (DAV), and a grant from GREYlong (JFM). The authors gratefully acknowledge generous support from the Angiosarcoma Awareness Foundation and donations to the Animal Cancer Care and Research Program of the University of Minnesota that helped support this project. JFM is supported in part by the Alvin S. and June Perlman Chair in Animal Oncology at the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement

- Federal agencies that oversee human and animal subject research

- University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- The investigator and research team for this study

- The sponsor or an agent for the sponsor

- Regulatory officials from the institution where the research is being conducted, to ensure compliance with policies or monitor the safety of the study

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that patent “Reduction of EGFR therapeutic toxicity,” related to this work and listing JFM, DV, and AB as inventors, has been filed by the University of Minnesota Office of Technology Commercialization. Anivive Lifesciences owns the license for eBAT for all non-human species and applications.

References

- 1.Oh F, Taras E, Todhunter D, Vallera DA, Borgatti A. Targeting EGFR and uPAR on human rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and ovarian carcinoma with a bispecific ligand-directed toxin. Clin Pharmacol 2018;10:113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schappa JT, Frantz AM, Gorden BH, Dickerson EB, Vallera DA, Modiano JF. Hemangiosarcoma and its cancer stem cell subpopulation are effectively killed by a toxin targeted through epidermal growth factor and urokinase receptors. Int J Cancer 2013;133:1936–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgatti A, Koopmeiners JS, Sarver AL, et al. Safe and effective sarcoma therapy through bispecific targeting of EGFR and uPAR. Mol Cancer Ther 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilbeam K, Wang H, Taras E, et al. Targeting pediatric sarcoma with a bispecific immunotoxin targeting urokinase and epidermal growth factor receptors. Oncotarget 2018; 9:11938–11947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh S, Stish BJ, Sachdev D, Chen H, Dudek AZ, Vallera D. A novel reduced immunogenicity bispecific targeted toxin simultaneously recognizing human EGF and IL-4 receptor in a mouse model of metastatic breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15(19):6137–6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh S, Tsai AK, Ohlfest JR, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Vallera DA. Evaluation of a bispecific biological drug designed to simultaneously target glioblastoma and its neovasculature in the brain. J Neurosurgery 2011; 114(6):1662–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai AK, Oh S, Chen H, Shu Y, Ohlfest JR, Vallera DA. A novel bispecific ligand-directed toxin designed to simultaneously target EGFR on human glioblastoma cells and uPAR on tumor neovasculature. J Neurooncol 2011;103(2):255–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stish BJ, Oh S, Vallera DA. Anti-glioblastoma effect of a recombinant bispecific cytotoxin cotargeting human IL-13 and EGF receptors in a mouse xenograft model. J Neurooncol 2008;87(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stish BJ, Oh S, Chen H, Dudek AZ, Vallera D. Design and modification of a novel bispecific ligand directed toxin, EGF4KDEL 7mut with decreased immunogenicity and potent anti-mesothelioma activity. Br J Cancer 2009; 101(7):1114–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pai LH, Wittes R, Setser A, Willingham MC, Pastan I. Treatment of advanced solid tumors with immunotoxin LMB-1: an antibody linked to Pseudomonas exotoxin. Nature Medicine 1996;2(3):350–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallera DA, Chen H, Sicheneder AR, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Taras EP. Genetic alteration of a bispecific ligand-directed toxin targeting human CD19 and CD22 receptors resulting in improved efficacy against systemic B cell malignancy. Leuk Res 2009; 33(9):1233–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vallera DA, Todhunter DA, Kuroki DW, Shu Y, Sicheneder A, Chen H. A bispecific recombinant immunotoxin, DT2219, targeting human CD19 and CD22 receptors in a mouse xenograft model of B cell leukemia/lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11(10):3879–3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Lan Y, Zhang D, Wang K, Wang Y, Hua ZC. SPRY1 promotes the degradation of uPAR and inhibits uPAR-mediated cell adhesion and proliferation. Am J Cancer Res 2014;4:683–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors: a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol 2014;37(5):473–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wendelburg KM, Price LL, Burgess KE, Lyons JA, Lew FH, Berg J. Survival time of dogs with splenic hemangiosarcoma treated by splenectomy with or without adjuvant chemotherapy: 208 cases (2001–2012). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015;247(4):393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner HL, London CA, Portela RA, et al. Maintenance therapy with toceranib following doxorubicin-based chemotherapy for canine splenic hemangiosarcoma. BMC Vet Res 2015;11:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thamm DH. Hemangiosarcoma In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, eds. Withrow & MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology 5th ed St Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2013;679–688. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachanova V, Frankel AE, Cao Q, et al. Phase I study of a bispecific ligand-directed toxin targeting CD22 and CD19 (DT2219) for refractory B-cell malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21(6):1267–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreitman RJ, Tallman MS, Robak T, et al. Phase I trial of anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin moxetumomab pasudotox (CAT-8015 or HA22) in patients with hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(15):1822–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinchcliff KW, DiBartola SP. Quality matters: publishing in the era of CONSORT, REFLECT, and EBM. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24(1):8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vail DM. Veterinary Co-operative Oncology Group - Common terminology criteria for adverse events (VCOG-CTCAE) following chemotherapy or biological antineoplastic therapy in dogs and cats v1.0. Vet Comp Oncol 2004;2(4):195–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guidance for Industry. Good clinical practice (VICH GL9) Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human services FDA, Center of Vet Med; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smallshaw JE, Ghetie V, Rizo J, et al. Genetic engineering of an immunotoxin to eliminate pulmonary vascular leak in mice. Nat Biotechnol 2003;21(4):387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Funakoshi T, Latif A, Galsky MD. Safety and efficacy of addition of VEGFR and EGFR-family oral small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors to cytotoxic chemotherapy in solid cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40(5):636–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Launay-Vacher V, Aapro M, De Castro G, et al. Renal effects of molecular targeted therapies in oncology: a review by the Cancer and the Kidney International Network (C-KIN). Ann Oncol 2015;26(8):1677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JH, Frantz AM, Anderson KL, et al. Interleukin-8 promotes canine hemangiosarcoma growth by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Exp Cell Res 2014;323(1):155–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamburini BA, Phang TL, Fosmire SP, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies inflammation and angiogenesis as distinguishing features of canine hemangiosarcoma. BMC Cancer 2010;10:619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorden BH, Kim JH, Sarver AL, et al. Identification of three molecular and functional subtypes in canine hemangiosarcoma through gene expression profiling and progenitor cell characterization. Am J Pathol 2014;184(4):985–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]