Abstract

The oncogene YAP has been shown previously to promote tumor growth and metastasis. However, how YAP influences the behavior of tumor cells traveling within the circulatory system has not been as well explored. Given that rate-limiting steps of metastasis are known to occur while tumor cells enter, travel through, or exit circulation, we sought to study how YAP influences tumor cell behavior within the circulatory system. Intravital imaging in live zebrafish embryos revealed that YAP influenced the distribution of tumor cells within the animal following intravenous injection. Control cells became lodged in the first capillary bed encountered in the tail, whereas cells over-expressing constitutively active YAP were able to travel through this capillary plexus, re-enter systemic circulation, and seed in the brain. YAP controlled transit through these capillaries by promoting active migration within the vasculature. These results were recapitulated in a mouse model following intravenous injection, where active YAP increased the number of circulating tumor cells over time. Our results suggest a possible mechanism where tumor cells can spread to organs beyond the first capillary bed downstream from the primary tumor. These results also show that a specific gene can affect the distribution of tumor cells within an animal, thereby influencing the global pattern of metastasis in that animal.

Keywords: Metastasis, Metastatic Dissemination, Zebrafish, YAP, Circulating Tumor Cells

Introduction

Metastasis comprises a complex cascade of events which culminates in the emergence of new tumors in distant locations (1). Prior research has shown that rate-limiting steps of metastasis can occur while tumor cells travel through the circulatory system, arrest at future sites of metastasis, extravasate, and grow into a new tumor, indicating the importance of understanding of these steps (2,3).

However, these steps can be challenging to study because they are highly dynamic. While in circulation, metastatic cells can travel at velocities of hundreds of microns per second, encounter a variety of physical and chemical stresses, and engage in transient interactions with a diverse cast of blood cells (4–7). Given the complicated and dynamic nature of these events, intravital imaging is required to fully elucidate them (8).

However, intravital imaging in mice is technically challenging and remains a routine technique in only a limited number of laboratories (9). One system that offers an attractive combination of an in vivo microenvironment with straightforward imaging techniques is the zebrafish embryo (10). Zebrafish embryos have been used to study the latter steps of the metastatic cascade including travel through circulation, arrest, extravasation, and early outgrowth at the metastatic site (11–16). Recently, high temporal and spatial resolution studies in zebrafish have elucidated how blood flow dynamics influence the locations of extravasation and how tissue-specific extravasation influences metastatic tropism (17,18).

We used the zebrafish system to test rapidly how genes known to promote metastasis in mice could influence the behavior of tumor cells in circulation. We observed that a Hippo-insensitive form of the oncogene YAP dramatically changed the behavior of tumor cells in circulation. YAP is a transcriptional co-activator that is downstream of the Hippo pathway (19). Increased activity of YAP (or its paralog TAZ) has been seen in almost every human cancer (20). In addition to promoting tumor growth and progression, YAP has been shown to promote metastasis in several tumor types (20–23). However, relatively little is known about how YAP influences the behavior of tumor cells in the circulation (22,24,25).

Here, we found that, while control cells remained trapped in the first capillary bed encountered, cells expressing active YAP were able to move through these vessels which allowed them to continue to travel through systemic circulation and disseminate more widely. This increased ability to move through small vessels appears to be due to enhanced intravascular motility. YAP cells also remained in circulation longer following intravenous injection into mice, suggesting that YAP can also enhance dissemination in a mammalian system. These results suggest a novel mechanism influencing the distribution of tumor cells throughout an animal.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish

Zebrafish were housed as previously described (26). The flk:dsRed2 zebrafish line was originally developed in the laboratory of Dr. Kenneth Poss (Duke) and was a kind gift from Dr. Mehmet Yanik (MIT). The fli1:EGFP zebrafish line was obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (Eugene Oregon). The flk:dsRed2 and fli1:EGFP lines were crossed into the transparent casper background (a kind gift from Dr. Leonard Zon, Boston Children’s Hospital). Following injection with tumor cells, embryos were maintained at 34C for the course of experiments. All zebrafish experiments and husbandry were approved by the MIT Committee on Animal Care.

Embryo Injections and Imaging

Embryo injections were performed as previously described (26). Embryos were imaged on an A1R inverted confocal microscope (Nikon) using the resonant scanner. For time-point imaging, Z stacks were acquired with a 7.4μm step size using a 10X objective. For time-lapse imaging, Z stacks were acquired with 7.4μm step size using a 10X objective with an additional 1.5X zoom lens for a total magnification of 15X. Whole embryos were imaged using a 4X objective to acquire Z stacks with a 15μm step size. For time-lapse imaging, Z stacks were acquired every 2–3 minutes for 12 hours following injection.

Embryos were mounted for imaging at single time points using a 3D-printed pin tool as previously described (26). For time courses, single embryos were housed in wells in 48-well plates between imaging. For time-lapse imaging, embryos were mounted in 0.8% agarose with 0.02% Tricaine (Sigma) in 24-well glass-bottom plates (Mattek). Embryos were maintained at 34C for the duration of time-lapse imaging through the use of a heated enclosure.

Real-time Cell Enumeration in Mouse Blood

Prior to intravenous injection into the jugular vein cannula of an un-anesthetized NOD/SCID/IL2Rγ-null mouse (NSG; Jackson Laboratory), confluent A375 EV and YAP-AA cells were harvested by trypsinization for 5 minutes. The trypsin was quenched with serum-containing medium and the cells were washed 3x with PBS and suspended at 25,000 cells per 50uL in PBS. During the 20–30 minute cell-preparation process, mice were connected to an optofluidic cell sorter as previously described (27) for a baseline scan. 25,000 ZsGreen cells of each type (A375 YAP-AA or EV) were injected slowly into the jugular veins of two separate mice. Each mouse’s blood was then scanned using the optofluidic cell sorter for the presence of fluorescent events for 3 hours after cell injection. All mouse experiments and husbandry were approved by the MIT Committee on Animal Care.

Cell Culture and Microfluidics

The A375 and HT-29 cell lines were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma), L-glutamine (2mM, ThermoFisher), and primocin (0.1mg/mL, Invivogen). HUVECS were grown in EGM medium (Lonza) supplemented with the EGM-2 BulletKit (Lonza). All cell lines were sorted for fluorescent protein expression on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD) to ensure that the entire population was fluorescent. Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination using the Lookout Mycoplasma qPCR Detection Kit (Sigma) prior to freezing down stocks. Vials were subsequently thawed and cultured for no more than one month for experiments. Cell stocks were made before passage 6. Microfluidics experiments using the constriction device were performed as previously described (28). The microfluidics constriction is 6um which is smaller than average diameter of the brain (9.9um) or tail vasculature (16.7um). Cells flowing through the device were traveling about twice as fast as cells flowing through the zebrafish vasculature (17,28).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

Additional materials and methods (tumor cell burden calculations, adhesion and migration assays, viral transduction and Western blotting) are described in the Supplemental Information.

Results

Metastasis Assays in Zebrafish Embryos

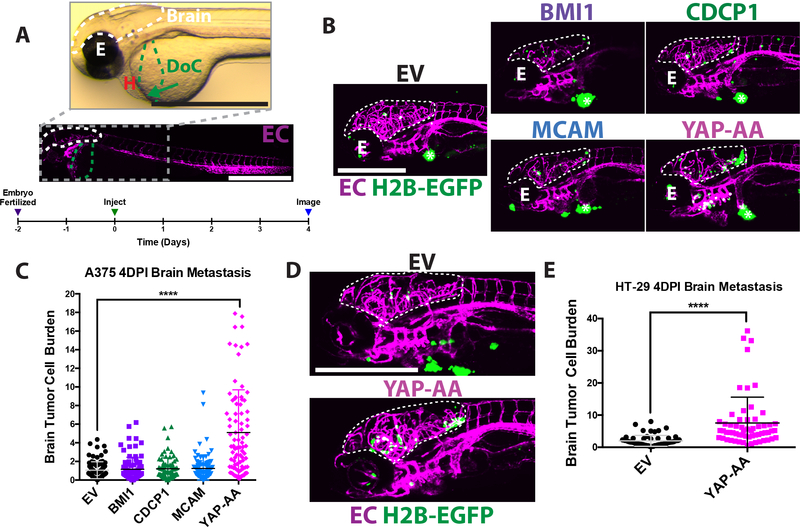

To study tumor cells in circulation and at the metastatic site, we injected cells directly into the circulation of 2-day-old zebrafish embryos via the Duct of Cuvier (DoC), a large vessel that drains directly into the heart using an established injection protocol (Fig 1A, Supplemental Movie 1) (11). As has been reported previously, most tumor cells are in the tail following injection, while few cells are in the brain of the embryo (17,18). This low basal level of metastasis combined with previous studies of brain metastasis in embryos (16,17) suggested to us that the brain might be a good location to look for enhanced metastasis. Metastasis was assayed 4 days post-injection (DPI) to allow cells time to extravasate and proliferate within the brain before imaging (Fig 1A).

Figure 1. YAP-AA promotes brain metastasis in zebrafish embryos.

(A) Overview images of a 2dpf flk:dsRed transgenic embryo with fluorescent endothelial cells (EC) imaged in brightfield (top) and fluorescence (bottom) to provide an overview of the experimental system. The target vessel, the Duct of Cuvier (DoC) is highlighted in green. An arrow indicates location of the injection site. The site of metastasis studied, the brain, is outlined in white. The eye (E) and heart (H) of the embryo are indicated. Scale bars are 1mm. The timeline below outlines the course of the experiments. (B) Representative images of the heads of flk:dsred zebrafish injected with A375 cells over-expressing different oncogenes or an empty vector (EV) control 4 days post-injection with the brain outlined in white. The eye is indicated by E. The tumor at the injection site is indicated with an asterisk *. Scale bar is 500μm. (C) Quantification of multiple images is shown in B; p<0.0001 using ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction for multiple hypothesis testing. n= 90 embryos per condition across 3 independent experiments. (D) Representative images of embryos 4 days after injection with HT-29 cells. Scale bar is 500μm. The brain is outlined by a white dotted line. (E). Quantification of images; p<0.0001 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. n=60 embryos per condition across 2 independent experiments. EC, endothelial cell. EV, Empty Vector; H2B-EGFP, A375 and HT-29 cells over-expressing histone H2B fused to EGFP. The same nomenclature will be used in all subsequent figures.

Cells were injected into flk1:dsRed transgenic embryos, which express dsRed in endothelial cells, allowing the vasculature to serve as a landmark. We generated A375 human melanoma and HT-29 human colon cancer cells which expressed histone 2B fused to EGFP (H2B-EGFP) and the far-red fluorescent protein iRFP670 to label the nucleus and cytoplasm respectively.

Four genes known to promote melanoma metastasis in mice, BMI1, CDCP1, MCAM, YAP, or an empty vector control (EV) (21,29–31), were over-expressed in these cells (Fig S1A) using a lentiviral expression system. BMI1, CDCP1, and MCAM were all wild-type proteins whereas YAP was a mutated form insensitive to inhibition by the Hippo pathway (YAP S127A,S381A, labeled as YAP-AA in this study; (21)).

A375 melanoma cells over-expressing these genes or an empty vector control (EV) were assayed for brain metastasis in the zebrafish embryo system. Only YAP-AA led to an increase in brain tumor cell burden, calculated as the percent area of the brain occupied by tumor cell nuclei (see supplemental materials and methods for further details) (Fig 1B and C). Similarly, YAP-AA promoted an increase in overall brain tumor size and number (Fig S1B, and S1C). YAP-AA also promoted brain metastasis by the HT-29 colon carcinoma cell line (Fig 1D, 1E and S1E). In A375 cells, YAP-AA enhanced brain metastasis out to 8DPI (Fig S1D). However, by this time, there was significant mortality so further experiments stopped at 4DPI. Overexpression of Wild-type YAP in the A375 cell line (Fig S2A) did not enhance metastasis (Fig S2B).

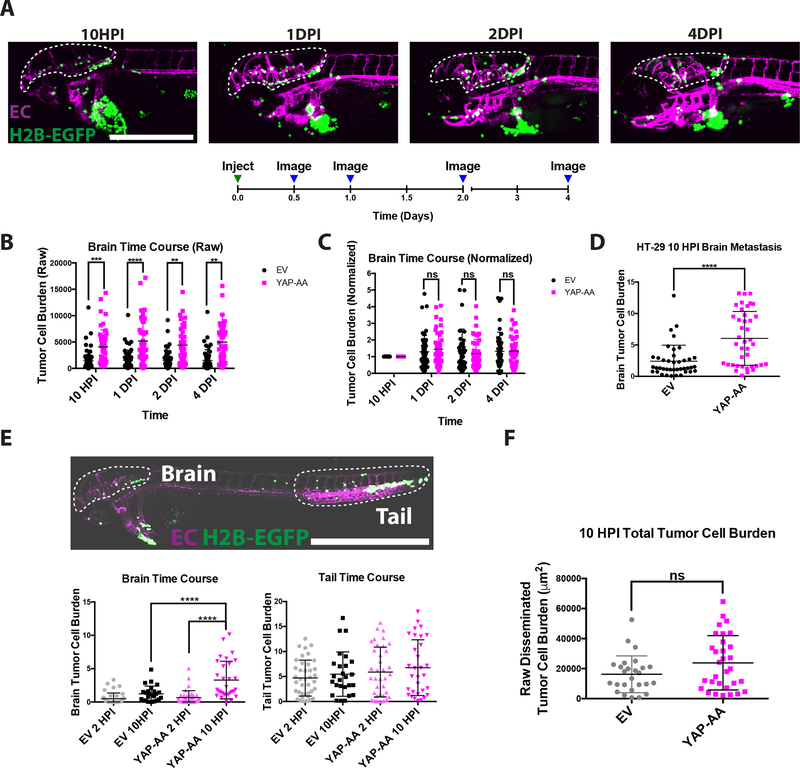

YAP-AA Promotes Brain Metastasis By 10 Hours Post-Injection

YAP regulates many properties that could influence metastasis, including proliferation, survival, and extravasation (20,22,32). To determine how YAP-AA was enhancing metastasis, we first investigated when YAP-AA was promoting metastasis. Embryos were imaged at 10 hours post-injection, 1DPI, 2DPI, and 4DPI (Fig 2A). At the earliest time point, 10 hours post-injection (HPI), there was already a significant difference between YAP-AA and EV control brain tumor cell burden (Fig 2B). It also appeared that the magnitude of the difference in brain tumor cell burden between control and YAP-AA cells did not change over time. To confirm that the effect of YAP-AA on metastasis occurred in the first 10 hours, the data for each fish were normalized to the 10-hour time point. When the data were analyzed in this way, there was no time-dependent difference between YAP-AA and control cells, indicating that YAP-AA’s enhancement of metastasis was occurring within 10 hours of injection (Fig 2C). YAP-AA also enhanced metastasis within the first 10 hours following injection in HT-29 cells (Fig 2D).

Figure 2. YAP-AA promotes metastasis within the first 10 hours of injection.

(A) Representative images of a single embryo injected with A375 cells imaged at the indicated time points. Scale bar is 500μm. (B) Quantification of the raw tumor cell burden in brains at the indicated time points. p=2.78×10−6,1.77×10−6,3×10−4, and 7.16×10−5 for each time point, respectively, using a two-tailed Student’s t-test at each time point with the Holm-Šídák correction for multiple hypothesis testing. n=52 embryos per condition across 2 independent experiments (C) Quantification of the same data as in (B) but the tumor cell burden for each embryo was normalized to the first time point for that embryo. Statistics were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test for each time point with the Holm-Šídák correction for multiple hypothesis testing. (D) Quantification of HT-29 tumor cell burden in brains 10 hours post-injection. p<0.0001 using a Student’s t-test. n= 40 embryos per condition over 2 independent experiments. (E) Overview image of an entire flk:dsRed embryo at 10HPI showing that most A375 cells (H2B-EGFP) in circulation arrest in the brain or the tail. Scale bar is 1mm. Quantifications are shown of tumor cell burden in the indicated organs at the indicated time points. p<0.0001 using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple hypothesis corrections. n=31 embryos per condition over two independent experiments. Scale bar is 1mm. (F) Sum of the area of fluorescent tumor cells (μm2) from (E) in the brain and tail at the 10-hour time points indicating that YAP-AA does not increase the total disseminated tumor cell burden. Statistics were done with a two-tailed Student’s t-test. p= 0.074. EC, endothelial cell. H2B-EGFP, tumor cell H2B-EGFP.

Following injection, there is often a bolus of cells at the injection site that could shed cells into circulation over time. Therefore, one possibility was that YAP-AA was promoting more cells to enter circulation. However, the size of the injection site bolus was not significantly different between EV and YAP-AA cells at 10HPI suggesting that YAP-AA was not promoting entry into circulation (Fig S3A and B).

Additionally, we compared the total disseminated tumor cell burden in EV and YAP-AA injected embryos. Following entry into circulation, most tumor cells lodge in the brain or tail of the embryo (Fig 2E). Therefore, the tumor cell burdens in the brain and tail were determined at 2HPI and 10HPI. At 2HPI, there was no difference between EV and YAP-AA in tumor cell burden in the brain. Consistent with previous experiments, by 10HPI, there was a significant difference between EV and YAP-AA tumor cell burden in the brain (Fig 2E). In the tail, there was a slight increase in the tumor cell burden between EV and YAP-AA injected fish by 10HPI. However, this difference was not significant (Fig 2E). When the sum of the tumor cell burden in the brain and tail (representing the overwhelming majority of disseminated tumor cells in the fish) was calculated, there was a slight increase in the total disseminated tumor cell burden in the YAP-AA embryos (Fig 2F). However, this difference was not statistically significant leading us to believe that enhanced entry into circulation could not explain the marked enhancement of brain metastasis observed. Rather, YAP-AA seemed to be primarily enhancing brain metastasis.

Given that YAP-AA appeared to be specifically enhancing brain metastasis, we hypothesized that YAP-AA might be affecting arrest in the brain, extravasation in the brain, or survival in circulation. To study these processes, we took advantage of the ability to perform time-lapse imaging in living embryos. The time that cells were seen to spend in the same spot within the brain vasculature was used as a proxy for arrest. When we compared the time that individual EV and YAP-AA cells spend arrested in the same location, there was no significant difference, suggesting that YAP-AA was not enhancing arrest (Fig S4A). YAP-AA also did not increase the fraction of cells that had extravasated by 10HPI (Fig S4B). We also probed extravasation by looking at the activity of invadopodia, ECM degrading protrusions that are required for extravasation, by performing gelatin degradation assays (33). YAP-AA cells degraded less fluorescent gelatin than did EV control cells (Fig S4C). These results together suggested that YAP-AA was not enhancing extravasation by A375 melanoma cells in this system. These results are in contrast with other tumor types (MDA-MB-231 and 4T1) where differences in brain metastasis in zebrafish embryos have been attributed to enhanced extravasation (16,17) and to other work where YAP has been shown to promote extravasation (25).

Finally, the survival of cells in circulation was studied. During programmed cell death, the nuclei of dying cells are seen to fragment (34). Using the H2B-EGFP label in our cells, we were able to monitor nuclear fragmentation over time. No significant differences in the fraction of cells seen to undergo nuclear fragmentation were observed between EV and YAP-AA cells (Fig S4D). Another possibility for YAP-AA’s enhancement of metastasis is through enhancing proliferation. However, given that mammalian cells take around 24 hours to divide, it seems unlikely that the difference in tumor cell burden that we see at 10 hours could be due to cell division. Collectively, these results indicate that YAP-AA is not promoting brain metastasis by significantly enhancing arrest, extravasation, survival in circulation, or proliferation in this system.

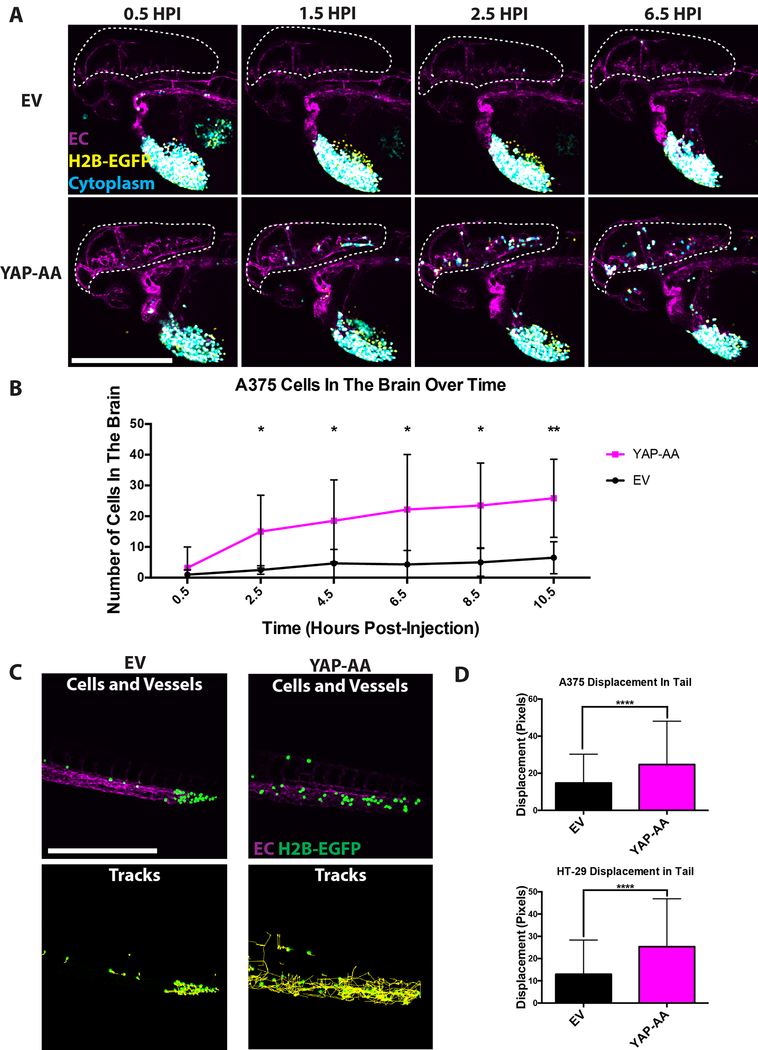

YAP-AA Promotes Tumor Cell Re-Entry Into Circulation Following Transient Arrest

During the collection of the data described above, we observed that there appeared to be more YAP-AA cells arriving in the brain during the hours after injection (Fig 3A and Supplemental Movies 2 and 3). When the cells in the brain were quantified over time, a steady influx of YAP-AA cells was observed over the first 10 hours while few EV cells were seen to arrive (Fig 3B). By 2.5HPI there was a significant increase in the number of YAP-AA cells in the brain and this increase between YAP-AA and control cells continued to increase over time (Fig 3B).

Figure 3. YAP-AA causes more cells to arrive in the brain.

(A) Representative still images from movies of the heads of embryos injected with EV or YAP-AA cells showing more YAP-AA-expressing cells arriving in the brain over time. Tumor cells express H2B-EGFP (yellow) and cytoplasmic iRFP670 (cyan). Overlap between these two channels appears white. EC, endothelial cell, magenta. Scale bar is 500μm. (B) Quantification of the number of A375 cells observed in the brain over time following injection. p=0.028 at 2.5HPI, p=0.037 at 4.5HPI, p=0.040 at 6.5HPI, p=0.011 at 8.5HPI, and p= 0.006 at 10.5HPI. Statistics were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test at each time point. n= 6 embryos per condition across 3 independent experiments. (C) Representative images of 7-hour A375 cell tracks in the tail generated in ImageJ from 12-hour movies. Tumor cells express H2B-EGFP (green). Scale bar is 500μm. (D) Quantification of 7-hour cell displacement in the tail for the indicated cell line. p<0.0001 for both cell lines. Statistics were calculated using a two-tailed student’s t-test. A375, n=1035 tracks per condition which were generated from movies of 6 embryos per condition. HT-29, n=724 tracks per condition generated from movies of 9 embryos per condition.

These observations showed that YAP-AA was promoting brain metastasis by increasing the numbers of cells that arrive in the brain in the first 10 hours. Given that YAP-AA only slightly enhanced the total number of cells in circulation, we wondered where these extra cells might be coming from. We took advantage of the small size of zebrafish embryos to image entire embryos to track all the cells in circulation over time. We observed that tumor cells were primarily clustered in the tail soon after injection (Supplemental Movies 4 and 5) as has been previously reported by others (17,18). The EV control cells primarily remained in the tail during the course of these movies. However, over time, YAP-AA cells were seen moving in the tail and rapidly disappearing (presumably after becoming dislodged and swept away by circulation as has been previously observed in this location (17,18)). Shortly thereafter, YAP-AA cells were observed to arrive at the brain. Given these observations and the observations that 1) YAP-AA only slightly increased the total number of cells in circulation 2) more YAP-AA cells arrive in the brain than control cells, we hypothesized that YAP-AA was affecting where cells end up in the animal by causing cells to leave the tail and re-enter systemic circulation.

To determine whether YAP-AA was causing tumor cells to leave the tail, the tails of embryos were imaged every 2 minutes for 12 hours following injection. While EV control cells mostly remained stationary following arrest, YAP-AA cells moved around within the tail vasculature and eventually disappeared (Fig 3C, D and Supplemental Movies 6 and 7).

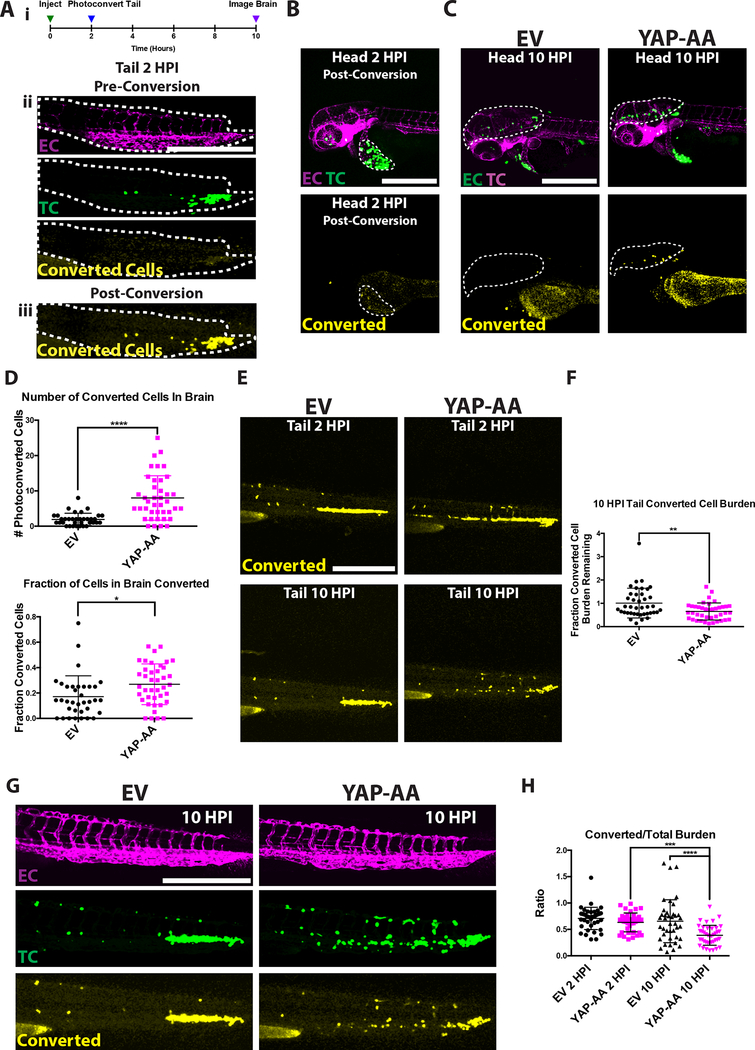

We next sought to determine whether the cells seen disappearing from the tail were traveling to the brain using the photoconvertible protein Dendra2, which converts from red to green fluorescence upon intense illumination with a 405nm laser (photoconverted signal is false-colored yellow in figure 4). A375 YAP-AA or EV control cells were engineered to express Dendra2 and iRFP670. iRFP670 is constitutively fluorescent and served as a control to label all tumor cells (false-colored green in figure 4). These cells were then injected into Fli1:EGFP embryos which have fluorescent vasculature (false-colored magenta in figure 4).

Figure 4. YAP-AA promotes tumor cell mobilization from the tail to seed the brain.

(A) (i) Experimental overview indicating that Dendra2-expressing A375 cells in the tail are photoconverted within 2 hours of injection. The brain is then imaged at 10HPI to identify photoconverted cells. (ii) A375 cells constitutively express iRFP670 (TC, green) allowing unconverted tumor cells to be identified. EC, Endothelial Cells are shown in magenta. (iii) Upon photoconversion, A375 cells exhibit converted Dendra2 fluorescence (yellow). The tail is outlined with a white dotted line. Scale bar is 500μm. (B) Image of the head at 2HPI after the cells in the tail have been photoconverted showing that cells in the head or injection site were not photoconverted. A bolus of A375 cells at the injection site is indicated with a white dotted line. Scale bar is 500μm. (C) Image of the head at 10HPI showing more photoconverted YAP-AA cells in the brain (white dotted line). Scale bar is 500μm. (D) Quantification of the number and fraction of photoconverted cells in the brain. P<0.0001 for the number of converted cells and p=0.012 for the fraction of cells that were converted. n= 35 embryos per condition across 3 independent experiments. (E) Image of photoconverted cells (yellow) in the tail at the indicated time points showing that YAP-AA cells are lost from the tail over time. (F) Quantification of the ratio of the photoconverted tumor cell burden remaining at 10HPI compared to 2HPI in the tail indicating the loss of photoconverted tumor cell burden over time. p=0.003 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. n= 35 embryos per condition across 3 independent experiments. Scale bar is 500μm.

(G) Representative images of the tails of fli1:EGFP zebrafish embryos 10HPI showing iRFP670 (green) labeling all A375 tumor cells and converted Dendra2 (yellow) labeling tumor cells photoconverted at 2HPI. Scale bar is 500μm. Endothelial cells are labeled in magenta.

(H) Quantification of the ratio of converted tumor cell burden to total tumor cell burden of images as in F. p<0.001 for YAP2HPI->YAP 10HPI, and p<0.0001 for EV10HPI->YAP10HPI using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. n=40 embryos per condition across 2 independent experiments. EC, endothelial cell. TC, tumor cell

Cells lodged in the tail were photoconverted at 2 hours post-injection (Fig 4A). If YAP-AA stimulates tumor cells to leave the tail and travel to the brain, there should be more photoconverted YAP-AA cells than photoconverted EV cells arriving in the brain by 10HPI. As a control, we first confirmed that only the cells in the tail were photoconverted at the 2HPI time point immediately following conversion (Fig 4B). At 10HPI, there were more photoconverted YAP-AA cells in the brains than photoconverted EV control cells (Fig 4C and D). The fraction of photoconverted cells in the brain at 10HPI was also significantly increased in embryos injected with YAP-AA cells (Fig 4D). These results fit our hypothesis that YAP-AA allows tumor cells to re-enter systemic circulation following initial arrest in the caudal capillary plexus.

We next studied the dynamics of photoconverted cells in the tail vasculature. If YAP-AA is causing tumor cells to leave the tail, one would expect the photoconverted YAP-AA tumor cell burden in the tail to decrease over time while the EV photoconverted tumor cell burden in the tail would remain about the same. Indeed this is what was observed (Fig 4E and F); at 10HPI there were many YAP-AA cells in the tail that were not photoconverted while almost all the EV control cells in the tail at this time point were still photoconverted (Fig 4 G,H). When the ratio of the converted to unconverted tumor cell burden in the tail was calculated, it was similar at the 2HPI time point for both EV and YAP-AA cells (Fig 4H). This ratio is not equal to 1 because photoconverted Dendra2 is dimmer than iRFP670. By 10 hours, this ratio had dropped for the YAP-AA cells while remaining essentially unchanged for EV control cells, again indicating that unconverted YAP-AA cells are arriving in the tail after photoconversion (Fig 4H). This observation fits the model that YAP-AA cells are constantly trafficking through the animal, becoming transiently entrapped in a vascular bed and eventually returning to systemic circulation. This leads to the question of whether YAP-AA cells are also leaving the brain vasculature.

While some cells were observed leaving the brain, there were also areas where cells remained sequestered for the duration of our imaging (Movie S2 and S3). As the vessels in the brain are narrower on average than the ones in the tail (17), we suspect that this difference may account for tumor cells remaining sequestered in the brain but escaping from the tail. One other explanation for YAP-AA cells escaping the tail would be that they are less able to extravasate in the tail than EV control cells. However, over the 10-hour period of interest, most cells are intravascular in both the EV and YAP-AA conditions (Movies S6 and S7).

YAP-AA Promotes Intravascular Migration which Allows Arrested Tumor Cells to Dislodge and Re-enter Systemic Circulation

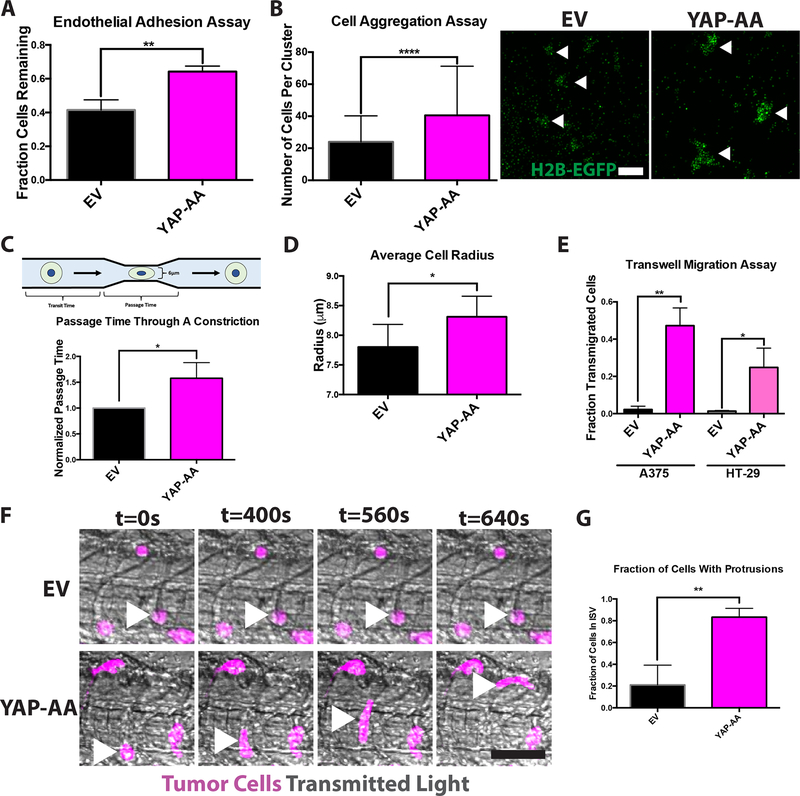

Once it became apparent that YAP-AA was enhancing tumor cell transit through the tail vasculature and that these cells could then travel to the brain, we investigated how YAP-AA could be facilitating transit through the tail vasculature. We hypothesized that YAP-AA might be doing this through decreased cell-cell adhesion, enhanced deformability, or enhancing active migration. However, YAP-AA cells were more adhesive to human endothelial cells in vitro (Fig 5A). YAP-AA cells also formed larger aggregates in a homotypic adhesion assay suggesting that they are more self-adhesive than control cells (Fig 5B). These two results combined suggested that YAP was not decreasing cell-cell adhesion.

Figure 5. YAP-AA promotes intravascular migration of tumor cells.

(A) Endothelial adhesion assay indicating that YAP-AA A375 cells are more adhesive to an endothelial monolayer. p=0.004 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test on data from 3 independent experiments. (B) Cell aggregation assay indicating that YAP-over-expressing A375 cells form larger aggregates in vitro. p<0.0001 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test n=117 aggregates per condition analyzed from two independent experiments. Arrowheads indicate example aggregates in an image of H2B-EGFP-expressing A375 cells following aggregation. Scale bar is 100μm. (C) Passage time through a 6μm constriction. n= 3 independent experiments with at least 300 cells analyzed per condition per experiment. p=0.03 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (D) Average cell radius determined using a Coulter counter. n= 7 independent experiments with at least 3000 cells per condition per experiment. p=0.02 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (E) Transwell migration assays for A375 and HT-29 cells indicating that YAP-AA promotes cell migration in vitro. A375, p=0.0013 HT-29 p=0.017. Statistics were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test on the averages of 3 independent experiments for each cell line. (F) Single frames from high-speed imaging of tumor cells in the tail 3 hours post-injection. Arrowheads indicate tumor cells of interest. Scale bar is 50μm. (G) Quantification of the fraction of tumor cells in the intersegmental vessels (ISVs) of the tail with protrusions that were at least as long as the cell nucleus. n=32 cells (EV) and 62 cells (YAP-AA) across 3 independent experiments. p=0.006 using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We next tested whether YAP might be making cells more deformable, and therefore better able to squeeze through narrow vessels, by measuring the time tumor cells took to pass through a 6μm constriction (passage time) in a previously described microfluidic device (28). Because tumor cells pass through this constriction in about a second, the passage times reflect a cell’s intrinsic deformability as there is not enough time to engage any active processes. The passage time of YAP-AA cells was 50% longer than that of EV control cells, indicating that YAP-AA cells were worse at moving through a constriction than control cells (Fig 5C). We believe that this increase in passage time may be due to YAP-AA cells being slightly larger than EV control cells (Fig 5D). To control for the fact that the two cell types were run through the device separately, the transit time through a region without a constriction was analyzed; EV and YAP-AA cells of the same size had the same transit times indicating identical running conditions (Fig S5A).

Given that YAP was not decreasing adhesion or enhancing deformability, we next investigated the possibility of active migration within the vasculature as it has been reported previously that tumor cells can actively migrate within the vasculature in the tail of 2-day-old zebrafish embryos (11). We first confirmed that YAP-AA enhanced migration in vitro in both the A375 and HT-29 cell lines in transwell migration assays, see supplemental methods (Fig 5E). We then tested whether YAP-AA was promoting migration in vivo by performing high-speed imaging of the tumor cells in the tail. We observed that almost all the EV control cells remained rounded and in the same spot during the course of these movies (Fig 5F and G and Movie S8). However, the YAP-AA cells dynamically extended protrusions and moved within the vessels (Fig 5F and G and Movie S9). This movement does not appear to be only a passive process because it still occurs when flow is blocked by an upstream tumor cell. When the movies of tumor cells in the brain were observed (Movies S2 and S3), YAP-AA cells also appear to migrate in the smaller vessels of the head whereas EV cells remain in the same spot over time suggesting that this migration is dependent on YAP and not on the architecture of the vasculature.

Collectively, our results from zebrafish suggest that YAP-AA can enhance tumor cell dissemination by promoting active migration through narrow capillary beds that entrapped control cells. This migration then allowed YAP-AA cells to re-enter systemic circulation and seed additional, downstream organs.

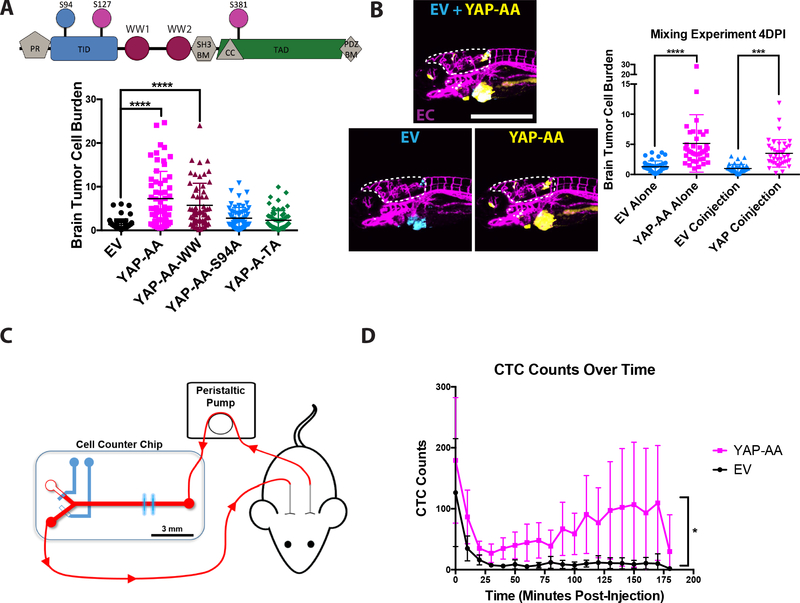

YAP Drives Dissemination Through TEAD-Mediated Transcription

We next sought to determine how YAP might be driving this enhanced dissemination at the molecular level. YAP is a transcriptional regulator, yet it lacks a DNA-binding domain so it requires interactions with partner transcription factors to regulate gene expression (19). Some of these partner transcription factors have been shown to have roles in metastasis, such as the TEADs, SMADs, and β-catenin (35). YAP’s promotion of metastasis has been shown to depend on interactions with different transcription factors in different contexts (21,36). YAP can also function to regulate genes independent from transcription (37). We therefore assayed whether the promotion of metastasis in this system was dependent on YAP’s ability to interact with the TEAD family of transcription factors, with other transcription factors through its WW domains, or through its transactivation domain. These possibilities were tested by over-expressing YAP with the S94A mutation which disrupts TEAD binding (YAP-AA-S94A), mutations that disrupt binding to the WW domains (W199F,W258F: YAP-AA-WW), or a deletion of the transactivation domain which abolishes transcriptional regulatory activity (YAP-A-TA)(Fig 6A, S6A). The YAP-AA-WW construct still promoted brain metastasis while YAP-AA-S94A and the YAP-A-TA mutants did not, indicating that YAP’s ability to interact with the TEAD family of transcription factors and to regulate transcription were both required to enhance metastasis in this context while interactions mediated through the WW domains were dispensable (Fig 6A).

Figure 6. YAP-AA increases the number of CTCs following intravenous injection into mice.

(A) (Upper) Domain map of YAP, indicating the locations of the mutations in the mutant constructs used. PR, Proline Rich; TID, TEAD Interacting Domain; PDZ BM, PDZ Binding Motif; WW, WW Domain; SH3 BM, SH3 Binding Motif; CC, Coiled-Coil Domain; TAD, Transactivation Domain. (Lower) Quantification of zebrafish brain metastasis formation 4DPI by A375 cells over-expressing the indicated mutant YAP constructs. (B) Brain tumor cell burden of EV control cells (cyan) and YAP-AA cells (yellow) at 4DPI from a co-injection experiment. p<0.0001 for cell types alone. p=0.0004 for co-injected cells. Statistics were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple hypothesis corrections. n=40 embryos per condition (EV alone, YAP-AA alone, and co-injection) across two independent experiments. Scale bar is 500μm. EC, endothelial cells (magenta). (C) Overview of experimental design for mouse CTC enumeration. Immediately after cell injection, the un-anesthetized mouse was connected to the cell-counter chip to enumerate fluorescent cells in the blood over time. A peristaltic pump withdraws blood from the carotid artery at a flow rate of 60 μL/min. The blood is directed into the main flow channel of the CTC sorter chip to excite and detect the ZsGreen-positive cells by blue (488 nm) laser lines and a photomultiplier tube (PMT), respectively. After exiting the chip, blood is returned to the mouse via the jugular vein cannula. (D) Quantification of the number of fluorescent A375 EV or YAP-AA CTCs detected during 10- minute intervals over time. n=5 mice per condition. p=0.031 using a repeated measures ANOVA.

YAP can regulate a large number of genes so we next were interested in narrowing down which YAP target genes may be promoting intravascular migration. Among the genes regulated by YAP are extracellular signaling molecules that could play a role in regulating motility. We had also observed that in previous work that soluble signaling factors can influence the behavior of nearby cells within the vasculature of zebrafish embryos (14). We therefore tested whether YAP-AA’s promotion of metastasis was a cell-autonomous process. Control A375 cells or YAP-AA cells were made to express Cerulean (Cyan) or iRFP670 (Yellow), respectively. Control and YAP-AA cells were injected into zebrafish embryos separately or mixed together in a 1:1 ratio. When co-injected, the YAP-AA cells showed enhanced brain metastasis by 4 days post-injection (Fig 6B). Co-injection did not enhance EV cell metastasis indicating that YAP’s enhancement of metastasis was confined to the YAP-AA cells (Fig 6B). These results suggest that YAP is promoting dissemination through a cell-autonomous mechanism that is not dependent on extracellular signaling molecules.

YAP-AA Increases Circulating Tumor Cells in Mice

We next sought to examine whether the results from zebrafish could be replicated in a mammalian system. We hypothesized that, if YAP-AA allowed tumor cells to travel through the first capillary bed encountered in mice, then YAP-AA cells should remain in circulation longer in a mouse than control cells following intravenous injection. We used a recently described system for studying the circulation dynamics of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in living mice to test this hypothesis (27). In this system, a catheter routes blood from the carotid artery through a custom cytometer and then returns it to the mouse via another catheter in the jugular vein (Fig 6C). Using this system, the number of fluorescently-labeled CTCs in blood can be tracked over time following a bolus injection via the jugular vein catheter. We observed significantly more YAP-AA cells in circulation over time compared to control cells (Fig 6D). Furthermore, while the number of EV CTCs quickly drops off, the number of YAP-AA cells initially drops but slowly increases between 25 and 175-minutes post-injection. This trend is consistent with our zebrafish results, where YAP-AA cells initially becoming lodged in small capillaries and slowly re-enter systemic circulation over time. These results show that YAP can increase the time tumor cells remain in circulation in a mammalian system. This increase in circulation time could allow these tumor cells to disseminate more widely throughout the animal than control cells that are mostly trapped in the earliest capillary beds they encounter.

Discussion

YAP Promotes Transit Through the First Capillary Bed Encountered

Our data suggest that YAP can induce tumor cells that have arrested in small capillaries to migrate within these vessels to points where they can re-enter systemic circulation and travel to distant organs. This observation represents a potential novel mechanism through which a gene can affect the distribution of disseminated tumor cells within an animal. This ability could conceivably then increase the fraction of disseminated tumor cells that can form metastases by allowing tumor cells to leave suboptimal metastatic sites and travel to more permissive ones.

It is often implicitly assumed that metastasizing tumor cells take a direct route from the primary tumor, through the circulatory system, to the metastatic site. Arrest in the capillaries of a distant organ is seen as the end of their trip, with cells either extravasating or dying. However our results, and the results of others (2,38,39), suggest that tumor cells might take a more circuitous route. In this model, arrest within the vasculature is not an endpoint but may be a transient event that an individual tumor cell could encounter multiple times, sampling different sites for suitability to establish a metastasis.

Intravital imaging studies in mice have observed that the arrest of individual tumor cells can be dynamic, with tumor cells often arresting temporarily before being carried along by blood flow some time later (12,26,40). Additionally, early studies, which tracked tumor cells in circulation in mice, suggested that cells seen departing following stable arrest in one organ can travel to other organs over the course of a few hours (2,41). At longer time scales, experiments show that tumor cell transit in animal models is more complex than just a linear stream from primary tumor to metastatic site. Instead, tumor cells can even metastasize from one primary tumor to another contralateral tumor or from a metastasis back to the primary tumor in a process called re-seeding (39).

The results of our experiments in mice, that YAP-AA cells remain in circulation longer than EV control cells, are consistent with activation of YAP allowing tumor cells to travel through the first capillary bed encountered. As the tumor cells in our experiments were injected intravenously into the jugular vein, the first capillary bed they encountered would be the lungs. Therefore, the fact that there were many more YAP-AA cells in circulation over time suggested that the YAP-AA cells were able to move through the capillaries in the lung to return to systemic circulation (Fig 6D). Furthermore, the slow increase in YAP-AA CTC counts over time is concordant with the results in zebrafish embryos where initially all YAP-AA cells are trapped in the tail vasculature and return to circulation over time (Movie S5).

Additional support for a dynamic model of arrest in the vasculature can be adduced from our result that YAP-AA cells are more adhesive to endothelial cells than control cells (Fig 5A). If arrest were entirely a passive process, then the more adhesive YAP-AA cells would be expected to be rapidly removed from circulation in our mouse experiments. The fact that YAP-AA cells circulate for much longer than control cells in figure 6D suggests that arrest is more complex than just passive adhesion to the endothelium.

One outstanding question is whether YAP-AA cells would form more tumors in organs downstream of the lungs in mice such as the liver. We suspect that this would be the case given that over-expressing activated YAP has previously been shown to greatly enhance the metastatic potential of poorly metastatic tumor cells and even primary cells in the lung (21). However, YAP can also influence the seeding and growth of metastases by regulating tumor cell survival and proliferation (22), which would make any increase in metastasis seen in a long-term experiment difficult to interpret.

The ability to move through the first capillary bed encountered may also be required to account for the presence of metastasis in some instances. For example, colon cancer frequently metastasizes to the liver which is the first capillary bed downstream through the circulatory system (42). However, colon cancer can also metastasize to the lungs. Given the layout of the circulatory system and the liver vasculature, it seems likely that in order to reach the lungs, tumor cells would first have to travel through capillaries in the liver (43). Genes that aid in this transit through the liver vasculature could therefore lead to more tumor cells reaching the lung and increase the number of metastases seen there.

YAP Promotes Intravascular Migration

A number of observations suggest that YAP-AA is promoting intravascular migration. First, our high-speed movies show YAP-AA cells actively extending protrusions and moving through the vessels in the tail in an elongated state that resembles active migration (Fig 5F and G). Second, the results from the microfluidic constriction device experiment suggested that the YAP-AA cells were not intrinsically better at squeezing through a channel (Fig 5C). Third, as has been previously reported, YAP greatly enhanced migration in 2D transwell migration assays (Fig 5E) (21).

Ours is also not the first report of intravascular migration by tumor cells in zebrafish embryos. For example, MDA-MB-435 melanoma cells were observed to migrate within the vasculature of zebrafish embryos following over-expression of Twist1 (11). Time-lapse imaging found individual tumor cells with a rounded morphology crawling actively within the vasculature. This crawling was confirmed to be an active process as it could occur against the direction of blood flow (11). Additional human and mouse tumor cell lines have been reported to crawl along the lumen of the vasculature in zebrafish embryos (18) as well as chicken embryos (33).

YAP’s Redistribution of Tumor Cells May Be Context-Dependent

Finally, a caveat to our experiments is that they were performed by over-expressing a constitutively active form of YAP. Ideally, we would also have shown that knocking down YAP in these cells would lead to a decrease in brain metastasis. However, the low baseline metastasis observed (Fig. 1B–E) makes it difficult to observe any decrease in metastasis in this system.

Also, in our experiments, YAP transcriptional activity was high, apparently independent of the state of the Hippo pathway. Given the failure of wild-type YAP to promote brain metastasis in our hands (Fig S2), it seems likely that YAP is normally repressed by the Hippo pathway within the vasculature in our system. However, there are a number of mechanisms that might activate YAP activity within the vasculature in other contexts.

YAP and TAZ have been shown to be activated by fluid shear stress (44,45) and this activation can promote tumor cell motility (45). Another way YAP could be activated within the vasculature is through the physical force on the nucleus as tumor cells are deformed by being pushed into narrow capillaries (46). It has been observed that tumor cells arrested in the vasculature undergo large deformations of their nuclei as they are pushed into narrow vessels by the blood flow so it seems likely that YAP/TAZ activity could be enhanced in these cells (12,47). Finally, tumor cells arrested at metastatic sites are known to interact with platelets and neutrophils (7,48,49) which have recently been shown to promote YAP/TAZ activity (50). As zebrafish lack circulating thrombocytes (the zebrafish equivalent of platelets) during the time period of our experiments, this mechanism for YAP activation would not have been available (51). Additionally, YAP activity could be constitutively high in some tumor cells as it has been shown that multiple oncogenic signaling pathways, such as Src, can lead to increased YAP activity and YAP-mediated metastasis (22,23).

In summary, we found that YAP-AA promoted brain metastasis in zebrafish embryos. Through time-lapse imaging, we were able to assess YAP-AA’s influence on arrest, extravasation, survival in circulation, and travel through the vasculature to determine how it was promoting metastasis in this system. We found that, while control cells arrested in the first capillary bed encountered and remained trapped there, YAP-AA induced tumor cells to migrate through these vessels and re-enter circulation, leading to more widespread dissemination and metastasis formation. Our results in mice were consistent with these results and suggest that YAP can enhance widespread dissemination in mammals as well. This ability to transit through the first capillary bed encountered represents a novel mechanism by which a gene can influence the global dissemination pattern of tumor cells and potentially increase the number of metastases in distant organs.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Findings demonstrate that YAP endows tumor cells with the ability to move through capillaries, allowing them to return to and persist in circulation, thereby increasing their metastatic spread.

Acknowledgements

We thank Adam Amsterdam for his guidance on experimental design and zebrafish husbandry. We thank Jess Hebert for his scientific advice, revisions to the manuscript, and assistance with mouse experiments. We also thank Eliza Vasile and Jeff Wyckoff of the Koch Institute Microscopy Core for their guidance on microscopy and assistance with imaging experiments. We thank Chenxi Tian for helpful discussions and assistance with mouse experiments. We also thank Alex Miller and Kelsey DeGouveia for their assistance with in vivo cytometry experiments.

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the MIT Ludwig Center For Molecular Oncology, and by the NIH (1RO1 CA184956 and 1U54CA217377). D.C.B was supported by the MIT Biology Department NIH training grant (5-T32-GM007287) and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported in part by the Koch Institute Support (Core) Grant (P30-CA14051) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

There are no potential conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor Metastasis: Molecular Insights and Evolving Paradigms Cell Elsevier Inc; 2011;147:275–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fidler IJ. Metastasis: quantitative analysis of distribution and fate of tumor emboli labeled with 125 I-5-iodo-2’-deoxyuridine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;45:773–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obenauf AC, Massagué J. Surviving at a distance: Organ-specific metastasis. Trends in Cancer. 2015;1:76–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirtz D, Konstantopoulos K, Searson PC. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis Nat Rev Cancer. Nature Publishing Group; 2011;11:512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furlow PW, Zhang S, Soong TD, Halberg N, Goodarzi H, Mangrum C, et al. Mechanosensitive pannexin-1 channels mediate microvascular metastatic cell survival. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:943–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM, Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z, et al. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature. 2015;527:186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labelle M, Hynes RO. The Initial Hours of Metastasis: The Importance of Cooperative Host-Tumor Cell Interactions during Hematogenous Dissemination. Cancer Discovery. 2012;2:1091–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahai E Illuminating the metastatic process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:737–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alieva M, Ritsma L, Giedt RJ, Weissleder R, van Rheenen J. Imaging windows for long-term intravital imaging: General overview and technical insights. intravital. 2014;3:e29917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White R, Rose K, Zon L. Zebrafish cancer: the state of the art and the path forward Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. Nature Publishing Group; 2013;13:624–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoletov K, Kato H, Zardouzian E, Kelber J, Yang J, Shattil S, et al. Visualizing extravasation dynamics of metastatic tumor cells. Journal of Cell Science. 2010;123:2332–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Au SH, Storey BD, Moore JC, Tang Q, Chen Y-L, Javaid S, et al. Clusters of circulating tumor cells traverse capillary-sized vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4947–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He S, Lamers GE, Beenakker J-WM, Cui C, Ghotra VP, Danen EH, et al. Neutrophil-mediated experimental metastasis is enhanced by VEGFR inhibition in a zebrafish xenograft model. J Pathol. 2012;227:431–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen MB, Hajal C, Benjamin DC, Yu C, Azizgolshani H, Hynes RO, et al. Inflamed neutrophils sequestered at entrapped tumor cells via chemotactic confinement promote tumor cell extravasation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:7022–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osmani N, Follain G, León MJG, Lefebvre O, Busnelli I, Larnicol A, et al. Metastatic Tumor Cells Exploit Their Adhesion Repertoire to Counteract Shear Forces during Intravascular Arrest. Cell Reports ElsevierCompany; 2019;28:2491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoletov K, Strnadel J, Zardouzian E, Momiyama M, Park FD, Kelber JA, et al. Role of connexins in metastatic breast cancer and melanoma brain colonization. Journal of Cell Science. 2013;126:904–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul CD, Bishop K, Devine A, Paine EL, Staunton JR, Thomas SM, et al. Tissue Architectural Cues Drive Organ Targeting of Tumor Cells in Zebrafish Cell Systems Elsevier Inc; 2019;:1–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Follain G, Osmani N, Azevedo AS, Allio G, Mercier L, Karreman MA, et al. Hemodynamic Forces Tune the Arrest, Adhesion, and Extravasation of Circulating Tumor Cells. Developmental Cell. 2018;45:33–52.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes & Development. 2013;27:355–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:783–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamar JM, Stern P, Liu H, Schindler JW, Jiang Z-G, Hynes RO. The Hippo pathway target, YAP, promotes metastasis through its TEAD-interaction domain Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. National Acad Sciences; 2012;109:E2441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren J, Xiao Y, Lamar J. YAP/TAZ Activation as a Target for Treating Metastatic Cancer. Cancers. 2018;10:115–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamar JM, Xiao Y, Norton E, Jiang Z-G, Gerhard GM, Kooner S, et al. SRC tyrosine kinase activates the YAP/TAZ axis and thereby drives tumor growth and metastasis J Biol Chem. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 2019;294:2302–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao B, Li L, Wang L, Wang C-Y, Yu J, Guan K-L. Cell detachment activates the Hippo pathway via cytoskeleton reorganization to induce anoikis. Genes & Development. 2012;26:54–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharif GM, Schmidt MO, Yi C, Hu Z, Haddad BR, Glasgow E, et al. Cell growth density modulates cancer cell vascular invasion via Hippo pathway activity and CXCR2 signaling Nature Publishing Group; 2015;:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamin DC, Hynes RO. Intravital imaging of metastasis in adult Zebrafish. BMC Cancer. BioMed Central; 2017;17:660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamza B, Ng SR, Prakadan SM, Delgado FF, Chin CR, King EM, et al. Optofluidic real-time cell sorter for longitudinal CTC studies in mouse models of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:2232–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byun S, Son S, Amodei D, Cermak N, Shaw J, Kang JH, et al. Characterizing deformability and surface friction of cancer cells Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. National Academy of Sciences; 2013;110:7580–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferretti R, Bhutkar A, McNamara MC, Lees JA. BMI1 induces an invasive signature in melanoma that promotes metastasis and chemoresistance. Genes & Development. 2016;30:18–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Ong S-E, Badu-Nkansah K, Schindler J, White FM, Hynes RO. CUB-domain-containing protein 1 (CDCP1) activates Src to promote melanoma metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1379–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie S, Luca M, Huang S, Gutman M, Reich R, Johnson JP, et al. Expression of MCAM/MUC18 by human melanoma cells leads to increased tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. YAP and TAZ: a signalling hub of the tumour microenvironment Nat Rev Cancer Springer US; 2019;:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leong HS, Robertson AE, Stoletov K, Leith SJ, Chin CA, Chien AE, et al. Invadopodia Are Required for Cancer Cell Extravasation and Are a Therapeutic Target for Metastasis. Cell Reports The Authors; 2014;8:1558–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Live to die another way: modes of programmed cell death and the signals emanating from dying cells Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. Nature Publishing Group; 2015;16:329–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M-K, Jang J-W, Bae S-C. DNA binding partners of YAP/TAZ BMB Rep Korean Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 2018;51:126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao B, Kim J, Ye X, Lai Z-C, Guan K-L. Both TEAD-binding and WW domains are required for the growth stimulation and oncogenic transformation activity of yes-associated protein. Cancer Research. 2009;69:1089–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori M, Triboulet R, Mohseni M, Schlegelmilch K, Shrestha K, Camargo FD, et al. Hippo signaling regulates microprocessor and links cell-density-dependent miRNA biogenesis to cancer. Cell. 2014;156:893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ZEIDMAN I, BUSS JM. Transpulmonary passage of tumor cell emboli. Cancer Res. 1952;12:731–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M-Y, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S, Nguyen DX, Zhang XHF, Norton L, et al. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell. 2009;139:1315–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kienast Y, Baumgarten von L, Fuhrmann M, Klinkert WEF, Goldbrunner R, Herms J, et al. Real-time imaging reveals the single steps of brain metastasis formation Nature Medicine Nature Publishing Group; 2009;16:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fidler IJ, Nicolson GL. Fate of recirculating B16 melanoma metastatic variant cells in parabiotic syngeneic recipients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;58:1867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Budczies J, Winterfeld von M, Klauschen F, Bockmayr M, Lennerz JK, Denkert C, et al. The landscape of metastatic progression patterns across major human cancers Oncotarget Impact Journals; 2015;6:570–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circulation Research. 2007;100:174–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HJ, Ewere A, Diaz MF, Wenzel PL. TAZ responds to fluid shear stress to regulate the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee HJ, Diaz MF, Price KM, Ozuna JA, Zhang S, Sevick-Muraca EM, et al. Fluid shear stress activates YAP1 to promote cancer cell motility. Nature Communications. 2017;8:14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elosegui-Artola A, Andreu I, Beedle AEM, Lezamiz A, Uroz M, Kosmalska AJ, et al. Force Triggers YAP Nuclear Entry by Regulating Transport across Nuclear Pores. Cell. 2017;171:1397–1410.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamauchi K, Yang M, Jiang P, Yamamoto N, Xu M, Amoh Y, et al. Real-time in vivo dual-color imaging of intracapillary cancer cell and nucleus deformation and migration. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Platelets guide the formation of early metastatic niches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E3053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct Signaling between Platelets and Cancer Cells Induces an Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Like Transition and Promotes Metastasis. Cancer Cell. Elsevier Inc; 2011;20:576–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haemmerle M, Taylor ML, Gutschner T, Pradeep S, Cho MS, Sheng J, et al. Platelets reduce anoikis and promote metastasis by activating YAP1 signaling Nature Communications Nature Publishing Group; 2017;8:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin H-F, Traver D, Zhu H, Dooley K, Paw BH, Zon LI, et al. Analysis of thrombocyte development in CD41-GFP transgenic zebrafish Blood. American Society of Hematology; 2005;106:3803–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.