Abstract

Adenoviruses are responsible for a spectrum of pathogenesis including viral myocarditis. The gap junction protein connexin43 (Cx43, gene name GJA1) facilitates rapid propagation of action potentials necessary for each heartbeat. Gap junctions also propagate innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses, but how viruses may target these structures is not understood. Given this immunological role of Cx43, we hypothesized that gap junctions would be targeted during adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) infection. We find reduced Cx43 protein levels due to decreased GJA1 mRNA transcripts dependent upon β-catenin transcriptional activity during Ad5 infection, with early viral protein E4orf1 sufficient to induce β-catenin phosphorylation. Loss of gap junction function occurs prior to reduced Cx43 protein levels with Ad5 infection rapidly inducing Cx43 phosphorylation events consistent with altered gap junction conductance. Direct Cx43 interaction with ZO-1 plays a critical role in gap junction regulation. We find loss of Cx43/ZO-1 complexing during Ad5 infection by co-immunoprecipitation and complementary studies in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived-cardiomyocytes reveal Cx43 gap junction remodeling by reduced ZO-1 complexing. These findings reveal specific targeting of gap junction function by Ad5 leading to loss of intercellular communication which would contribute to dangerous pathological states including arrhythmias in infected hearts.

Keywords: Adenovirus, Gap junction, Connexin, β-catenin, myocarditis

INTRODUCTION

Gap junctions comprising connexin proteins couple the cytoplasms of apposing cells, effecting the direct exchange of factors such as signaling molecules and ions (1). Connexin43 (Cx43, gene GJA1) is the most ubiquitously expressed connexin and is necessary for rapid propagation of action potentials in the working myocardium (2). Alterations in Cx43 and remodeling of gap junctions during cardiac stress alters electrical coupling between myocytes and precipitates the arrhythmogenic substrate of sudden cardiac death (3–5). Additionally, gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) facilitates the propagation of innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses. Specifically, transfer of 2’3’-cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP), capable of activating the interferon response, and cell-to-cell exchange of peptides utilized for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation by uninfected cells can both occur via GJIC (6–8). MHC presentation and interferon activation are both well-established antiviral processes and thus GJIC provides a means for uninfected cells to amplify the host response and limit viral spread (9–13).

Extensive transcriptional and post-translational regulation of Cx43 allows dynamic control of gap junction gating and turnover (14–16). Studies on specific transcriptional regulation of Cx43 during development and disease have identified numerous transcription factors responsible that include β-catenin, TBX2, PAR1, AP1, SP1, NKX2.5, STAT3, and IRX3 (17–19). Interestingly, gap junction formation is also regulated post-transcriptionally by internally translated isoforms of Cx43 which modulate channel assembly in the Golgi apparatus (20–22). Post-translational modifications, primarily phosphorylation of the Cx43 C-terminus, are well described in modification of forward-trafficking, gap junction assembly, channel conductance, and internalization (23–26). Furthermore, these phosphorylation events affect Cx43 protein-protein interactions with binding partners such as Zonula Occludens 1 (ZO-1) and 14-3-3 proteins (26–28). Data suggest Cx43/ZO-1 association is increased during incorporation into and removal from the gap junction plaque, interpreting this interaction with increased Cx43 trafficking dynamics (29–32). Additionally, tight junction associated molecules such as the Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) impact gap junction formation in addition to ZO-1 (33).

Adenoviruses are non-enveloped dsDNA tumor viruses typically associated with mild respiratory illness that can also lead to life-threatening diseases including viral myocarditis (34, 35). Importantly, adenovirus is increasingly recognized as a cause of sudden cardiac death and has been detected in 59% of patients with virus-associated myocarditis (35, 36). Human adenovirus serotypes 5 and 2 are predominantly responsible for adenoviral mediated viral myocarditis, but the molecular mechanisms of adenovirus cardiotropism and infection-induced arrhythmogenesis are unknown (37). Due to pathogen-host species specificity, modeling adenovirus-induced human viral myocarditis has been historically difficult and current knowledge of viral myocarditis mechanisms is primarily derived from mouse models utilizing another major cause of myocarditis in humans, Coxsackievirus B3 (38–42). Ineffective infection of murine cells with human adenovirus reveals species-dependent subcellular differences limiting development of such a model (43, 44). Previously reported mouse models of viral myocarditis utilizing mouse adenovirus have focused primarily on chronic damage caused by immune responses as opposed to alterations in cardiomyocyte biology during active infection (45–47). Adenoviral proteins in Early Region 4 (E4) are reported to negatively regulate Cx43 while positively regulating Cx40 in the context of Early Region 1 (E1) and 3 (E3) deleted human adenoviral vectors in mouse heart tissue which may not reflect wild type infection (48). Furthermore, adenoviral E4 open reading frame 1 (E4orf1) protein is known to activate AKT which, through phosphorylation, regulates both Cx43 and β-catenin (26, 49). With the advent of human induced pluripotent stem cell derived-cardiomyocytes (HiPSC-CM) it is now possible to study molecular mechanisms contributing to human adenoviral myocarditis and arrhythmogenesis. Indeed, HiPSC-CMs have been demonstrated as an effective model for screening antivirals for Coxsackieviral myocarditis (50).

Here, we investigate the effect of adenoviral infection on gap junctions and Cx43. Given that adenoviral early gene products activate host-cell protein kinase signaling pathways which are known to converge on Cx43, we hypothesized that Cx43 expression and GJIC would be compromised during infection (51–53). Spontaneously immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) infected with wild type human adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) are employed to determine the impacts on gap junction protein expression and function as a non-transformed epithelial cell model. These experiments are complemented with studies in HiPSC-CMs to validate physiological relevance and provide insight on the impact of infection on cardiac muscle cells which require gap junctions to facilitate each heartbeat. We demonstrate a loss of Cx43 at the level of transcription through β-catenin transcriptional activity and that gap junction function is impaired prior to loss of Cx43 protein. We find altered Cx43 phosphorylation associated with reduced channel open probability as a mechanism for reduced GJIC (54). Finally, reduced complexing of Cx43 with ZO-1 in cardiomyocytes demonstrates remodeling of cardiac electrical coupling structures during acute viral infection, which in vivo would contribute to an arrhythmogenic substrate.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HEK293FT (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), HEK293A (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), A549 (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), HT1080 (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), HaCaT (AddexBio, San Diego, CA, USA), and HaCaT-GJA1+ cells were maintained and passaged in DMEM, high glucose, with L-Glutamine (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), non-essential amino acids (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and MycoZap Plus-CL (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise specified. HiPSC-CMs were obtained from Axol Bioscience and maintained in Cadiomyocyte Maintenance Basal Medium (Axol, Cambridge, UK) supplemented with Cardiomyocyte Supplement (Axol, Cambridge, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37 °C.

Viruses and infection

Ad5 was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and propagated in A549 cells. AdlacZ was generated according to manufacturer’s instructions from pAd/CMV/V5-GW/lacZ (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Viruses were purified by CsCl ultracentrifugation as previously described and titer determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy in HEK293A cells (55). All infections were performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 in serum-free DMEM and supplemented with equal volume of supplemented DMEM (10 % FBS) 1-hour post infection (hpi). For inhibition of transcriptional activity of β-catenin using LF3, HaCaT cells were infected in serum-free DMEM as above followed by addition of equal volume supplemented DMEM (10 % FBS) containing DMSO or LF3 (final concentration 60 μM; Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) 1 hpi. To test LF3 effects on adenoviral replication kinetics, cells were infected and treated with LF3 as above followed by isolation of DNA using DNeasy (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was then performed for adenoviral genomes with SYBR Select Master Mix for CFX (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) on a QuantStudio 6 Flex system (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) with primers designed to amplify adenoviral gDNA (forward primer- TTAGATTATGTGGAGCACCC; reverse primer- CACATAATATCTGGGTCCCC). To assay changes in GJA1 mRNA independent of viral infection, HaCaT cells were treated with DMSO or LF3 (final concentration 60 μM) and subjected to RT-qPCR at 24 h post-treatment.

RT-qPCR

Cells were lysed in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and clarified by phenol-chloroform phase separation before RNA isolation using PureLink RNA mini kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and PureLink on-column DNase digestion (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated with iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Select Master Mix for CFX (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) on a QuantStudio 6 Flex system (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). 18SrRNA (forward primer-GGCCCTGTAATTGGAATGAGTC; reverse primer- CCAAGATCCAACTACGAGCTT) and GAPDH (forward primer- ACATCGCTCAGACACCATG; reverse primer- TGTAGTTGAGGTCAATGAAGGG) were utilized as internal references. Gene expression data was collected for CDKN1A (forward primer-GCAGACCAGCATGACAGAT; reverse primer- GAGACTAAGGCAGAAGATGTAGAG), SFN (forward primer- CACTACGAGATCGCCAACAG; reverse primer- GGTGCTGTCTTTGTAGGAGTC), GJA1 (forward primer- ACUUGGCGUGACUUCACUAC; reverse primer-GUACUGACAGCCACACCUUC), GJA5 (forward primer – GCAGCCTCAGCTTTACAAATG; reverse primer – GTGACAGATGTTGGCAGGAAT), GJC1 (forward primer- GGTAACCGAAGTTCTGGACAA; reverse primer- CAATCAGAACAGTGAGCCAGA), PKP2 (forward primer- AAGCGATGAGAAGATGTGACG; reverse primer- GGAGAGGTTATGAAGAATGCACA), TJP1 (forward primer- ATAGCTGATGTTGCCAGAGAA; reverse primer- CAGAGCTACGTTGGTCAGTTC), CTNNB1 (forward primer- AAAATGGCAGTGCGTTTAG; reverse primer-TTTGAAGGCAGTCTGTCGTA), TBX2 (forward primer- CCATCCCGCCTAGCACTAG; reverse primer- CTAGGCTCCCGGCTGTTTC), and F2R (forward primer- GTGCTGTTTGTGTCTGTGCT; reverse primer- AGCGACACAATTCAGACCCA).

Ad5 E4orf1 cloning and ectopic expression.

Ad5 E4orf1 was cloned into pSF-CAG-AMP (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using In-Fusion cloning (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, Ad5 genomes were isolated from 10 μl of purified Ad5 using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). E4orf1 was amplified using CloneAmp HiFi PCR Premix (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) with forward primer: CCGAGCTCTCGAATTATGGCTGCCGCTGTGGAAGC and reverse primer: AGTCAGTCAAGCTAGTTAAACATTAGAAGCCTGTCTTACAACAGGAAAAACA. Following pSF-CAG-AMP digestion with BamHI and EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and purification In-Fusion cloning was performed and successful constructs purified following validation by sequencing. HaCaT cell were plated in 100 mm dishes and transfected with 5 μg of pSF-CAG-AMP-Empty or pSF-CAG-AMP-E4orf1 24 h prior to harvesting and analysis by western blotting and RT-qPCR. Validation of E4orf1 ectopic expression by RT-qPCR was performed as above with forward primer- GCGTAGAGACAACATTACAGCC and reverse primer- TGTATGTTGTTCTGGAGCGGG and mRNA abundance calculated using the formula (1/(2CT of target)) / (1/(2CT of Reference Average)) with GAPDH and 18SrRNA utilized as internal references.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 % Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 % sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM NaF, 200 μM Na3VO4, 0.1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 mM n-ethylmaleimide) supplemented with HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Protein was clarified by sonication and centrifugation and concentration determined by DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). 4X Bolt LDS sample buffer supplemented with 400 mM DTT was added to samples then heated to 70 °C for 10 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE using NuPAGE Bis-Tris 4–12 % gradient gels and MES (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) running buffer according to manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were transferred to PVDF (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) membrane and fixed in methanol followed by air drying. PVDF membranes were reactivated in methanol followed by blocking in 5 % nonfat milk (Carnation, Los Angeles, CA, USA) or 5 % bovine serum albumin (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in TNT buffer (0.1 % Tween 20, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody labeling was performed overnight at 4 °C using primary antibodies rabbit anti-Cx43 (1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:5000; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), mouse anti-GAPDH (1:2000; Fitzgerald Industry International, Acton, MA, USA), mouse anti-Adenovirus Hexon [8C4] (1:5000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-β-catenin (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-phospho-β-catenin (Ser552) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse anti-Adenovirus E1A [M73] (1:2000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-phospho-(Ser) 14-3-3 Mode 1 binding motif (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-phospho-Cx43(Ser368) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse anti-ZO-1 (1:1000, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), mouse anti-E-Cadherin (1:1000; BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), rabbit anti-CAR (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), goat anti-RPL22 (1:800; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-Cx40 (1:500; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), rabbit anti-Cx45 (1:500; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), and rabbit anti-phospho-Cx43(Ser262) (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Membranes were washed 6 times before secondary antibody labeling for 1 h at room temperature with goat secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555, Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), or HRP (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or donkey anti-goat conjugated to Alexa Fluor 633 (1:5000; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Fluorescently labeled membranes were soaked in methanol and air dried prior to imaging. Clarity Western ECL (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) substrate was added to HRP labeled membranes according to manufacturer’s instructions prior to imaging. Stripping was performed following phospho-Cx43 isoform detection prior to labeling for total Cx43 using ReBlot Plus Strong (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Membranes were imaged on a Chemidoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Cells were fixed for 20 min with 4 % PFA in PBS at room temperature or for 5 min with −20 °C methanol on ice. Cells were permeabilized and blocked with 5 % normal goat serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 0.5 % Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody labeling was performed for 1 h at room temperature using rabbit anti-Cx43 (1:2000; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), mouse anti-E2A [B6–8] (1:250; generously provided by D. Ornelles, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Microbiology and Immunology), mouse anti-Adenovirus E1A [M73] (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-β-catenin (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), rabbit anti-Ad5 (1:5000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and mouse anti-ZO-1(1:500; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cells were washed 6 times prior to secondary antibody labeling for 1 h at room temperature with goat secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). During secondary antibody labeling cells were counterstained with DAPI and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) conjugated Alexa Fluor 647. Slides were mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Image analysis

To measure nuclear β-catenin enrichment, 8-bit single-Z image thresholding was performed on DAPI channels and divided by 255 to create fluorescence intensity values of 0 (non-nuclear) and 1 (nuclear). Single-Z images were utilized to reduce capture of axial fluorescence signal above and below nuclei. The threshold and binary DAPI channels were multiplied by the β-catenin channels to exclude non-nuclear signal and mean fluorescence intensity was subsequently normalized to total β-catenin mean fluorescence intensity after subtracting background. To measure Cx43/PDI colocalization, single Z-slices of Cx43 and PDI channels were subjected to Pearson’s correlation and Manders’ co-occurrence with thresholding using the JACoP plugin (56). Colocalization of pixels were generated using the Colocalization plugin. Analyses performed in ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Triton X-100 solubility assay

Cells were harvested in 1% Triton X-100 buffer (50mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 % Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM ethylene glycols-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N,N-tetraacetic acid [EGTA], 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4) supplemented with HALT Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher). Samples were rotated at 4 °C for 1 h. A small volume was removed to serve as the total protein fraction. Remaining lysate was centrifuged for 30 min at 15,000 × g at 4 °C and supernatant reserved as soluble fraction. Pellets containing insoluble proteins were resuspended in Bolt LDS sample buffer with DTT (Thermo Fisher). All samples were sonicated and centrifuged for 20 min. at 10,000 × g at 4°C followed by addition of 4X Bolt LDS sample buffer supplemented with 400 mM DTT where appropriate prior to western blotting.

Scrape-load dye-transfer assay

HaCaT cells were seeded and grown to confluency prior to infection with AdlacZ or Ad5 in 35 mm glass-bottom dishes and then washed 3 times with PBS prior to adding 0.05 % Lucifer Yellow (CH K+; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 100 μg/mL dextran (MW-10,000 Da.) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Scrape-load dye-transfer assay was performed as previously described using 5 min room temperature incubation time post-scrape (57). Cells were washed 3 times with PBS then immediately fixed for 20 min at room temperature with 37 °C 4 % paraformaldehyde prior to imaging. Quantification of dye spread was performed as previously described using ImageJ software (57).

Engineering of lentivirus-mediated stable GJA1 overexpressing HaCaT cells (HaCaT-GJA1+)

Lentivirus were produced from pLenti6.3-hGJA1 (20) according to manufacturer’s instructions (ViraPower Lentiviral Expression System; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and propagated in 293FT cells. Lenti-hGJA1 titer was determined according to manufacturer’s instructions in HT1080 cells and normalized virus was used to transduce HaCaT cells. 48 h post transduction, lentivirus-transduced HaCaT cells were treated with blasticidin (10 μg/ml) supplemented media. Media changes were performed every 2 days and viable colonies extracted with cloning rings (Scienceware, Warminster, PA, USA). Clones were expanded and screened for expression by western blotting and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

Immunoprecipitation

Infected HaCaT-GJA1+ or HaCaT cells were harvested at indicated hours post infection on ice in RIPA. Cell lysates were normalized to 500 μg per reaction. Inputs were removed prior to immunoprecipitation and denatured in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at RT. Protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) were added at 10 % sample volume to preclear lysates for 20 min at 4°C prior to immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-Cx43 antibody (2 μg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), or rabbit IgG isotype control (2 μg, Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at 4°C. Samples were then incubated with Protein G Dynabeads for 45 minutes at 4°C. Samples were washed in RIPA buffer followed by eluting with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer and subject to western blotting.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Ad5- or AdlacZ-infected HaCaT cells were harvested 24 hpi on ice in CoIP buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM NaF, 100 μM Na3VO4, 0.5% Triton X-100) with HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell lysates were normalized to 1 mg per reaction. Inputs were removed prior to CoIP and denatured in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer. Protein G Dynabeads were added at 10 % sample volume to preclear lysates for 30 min at 4°C prior to immunoprecipitation with mouse anti-ZO-1 (2 μg, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) or mouse IgG isotype control (2 μg, Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at 4°C. Samples were incubated with Protein G Dynabeads for 30 minutes at 4°C. Samples were washed in CoIP buffer followed by eluting and denaturing with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer and subject to western blotting.

Super-resolution STORM localization and analysis

Cells were fixed with −20 °C methanol on ice for 5 min followed by 3 washes with PBS. Cells were blocked with 5 % normal donkey serum and 0.5 % Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody labeling was performed for 1 h at room temperature with rabbit anti-Cx43 (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and mouse anti-ZO-1 (1:500; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cells were washed 6 times prior to secondary antibody labeling for 1 h at room temperature with donkey antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 or CF568 (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA). Cells were washed 6 times and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) conducted with a Vutara 350 microscope (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Cells were imaged in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 % (wt/vol) glucose buffer containing 20 mM mercaptoethylamine, 1% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol, 168 active units/ml glucose oxidase, and 1404 active units/ml catalase. 5000 frames were acquired for each probe and 3D images were reconstructed in Vutara SRX software. Coordinates of localized molecules were used to calculate pair correlation functions in the Vutara SRX software.

Statistics

All quantification was performed on experiments repeated at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad Prism 8.2.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were analyzed for significance using Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (when comparing basal gap junction gene expression data), two-way ANOVA, with Sidak’s (when comparing Ad5-infected to control within time points across multiple time points) or Dunnet’s (when comparing infected time points to 0 hpi) multiple comparisons tests. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Connexin43 protein levels are reduced during adenovirus type 5 infection.

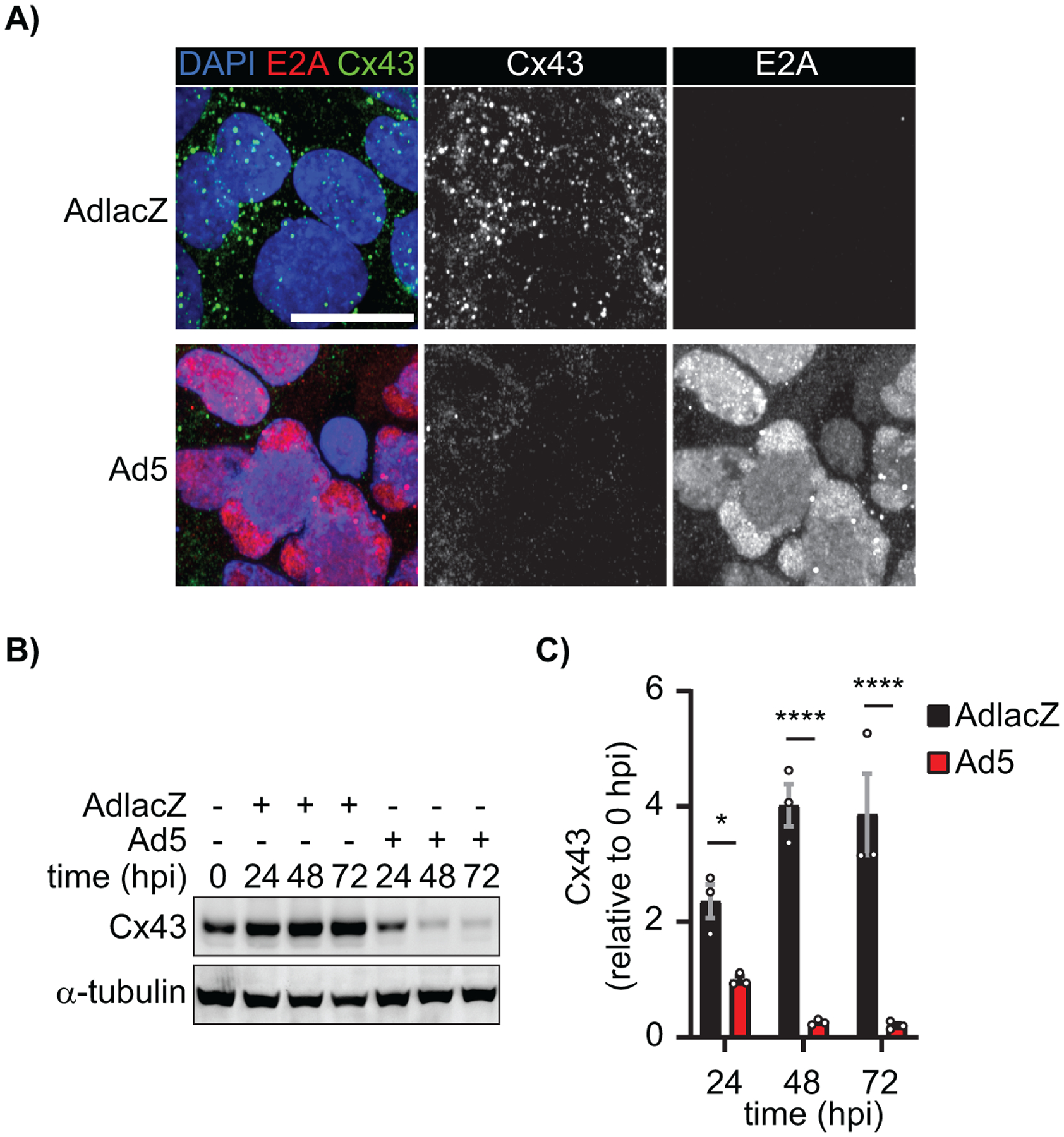

Given Cx43 gap junctions immunologically couple cells to effect propagation of antiviral immune responses, we sought to determine the impact on Cx43 by Ad5 infection (6–8). To assess Cx43 levels and subcellular localization (cytosolic or membrane) during infection, HaCaT cells were infected with either AdlacZ or Ad5 at a MOI of 10 iu/cell followed by fixation 48 hpi and immunolabeled for Cx43 (green) and visualized by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Adenoviral E2A (red) labeling confirms 100% infection with nuclei labeled using DAPI (blue). We find global reductions of Cx43 in Ad5-infected cells compared to controls (Figure 1A). To confirm immunofluorescence data biochemically, HaCaT cells were infected at a MOI of 10 iu/cell with Ad5 or AdlacZ and protein lysates were harvested every 24 hpi for 72 h. We find Cx43 levels are reduced to 42% by 24 hpi declining to 5% at 72 hpi compared to AdlacZ-infected controls (Figure 1B, quantified in 1C). To test global versus specific reductions in host-cell protein levels, we also investigated Cx40, Cx45, RPL22, E-cadherin, and CAR where we reveal a reduction of CAR to 48% with no loss of Cx40, Cx45, E-cadherin, or RPL22 at 24 hpi (Figure S1). AdlacZ is a replication incompetent adenoviral vector and serves as a control for virus binding primary and secondary receptors, integrin-mediated endocytosis, and cytosolic dsDNA host-cell responses. Increased Cx43 expression was observed over time in control cells which we attribute to stabilization of intercellular junctions upon confluency.

Figure 1). Connexin43 protein levels are reduced during adenovirus type 5 infection.

HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdlacZ at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 iu/cell and fixed at 48 hpi or protein harvested every 24 hpi for 72 h. A) Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of HaCaT cells at 48 hpi probed for Cx43 (green) and adenovirus E2A (red) with nuclei identified using DAPI (blue). Original magnification: X100. Scale bar: 20μm. B) Western blot probed for Cx43 expression in HaCaT cells. Detection of α-tubulin serves as loading control. C) Densitometry analysis of B. Statistical analysis was performed with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (n=3). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p<0.0001. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. See also Figure S1.

Specific targeting of gap junction gene transcription during adenovirus type 5 infection.

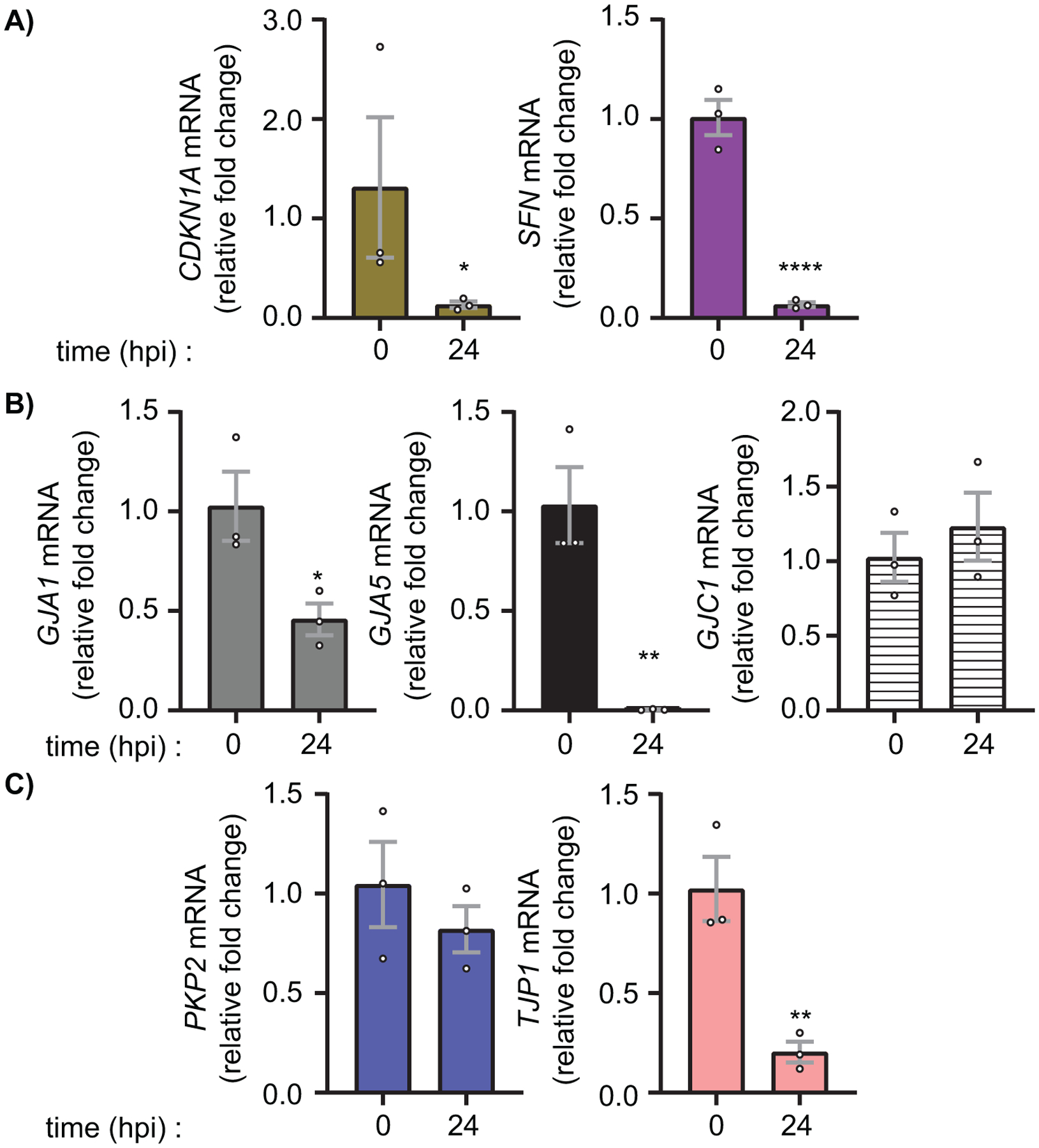

In order to determine if changes in Cx43 protein levels were a result of negative gene regulation, we performed RT-qPCR on Ad5-infected HaCaT cells at 24 and 48 hpi. We demonstrate dynamic host-cell gene expression at 24 hpi with both increased and decreased levels of specific host-cell mRNAs and, as such, we focused our studies on mechanisms of Cx43 gap junction modulation within this first 24 h period. By 48 hpi all genes tested were suppressed as expected as the viral life cycle had progressed to effect virally-induced host-cell global gene repression. Consistent with previous findings of active Ad5 infection inactivating and degrading p53, we confirm a reduction in known p53 transcriptional targets CDKN1A (p21) to 14% and SFN (14-3-3σ) to 7% (Figure 2A) (58–65). GJA5 (Cx40), GJA1 (Cx43), and GJC1 (Cx45) were detected by RT-qPCR in HaCaT cells, with GJA1 having highest expression (Figure S2). After infection with Ad5, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates a targeting of GJA1 and GJA5 in HaCaT cells reducing levels to 46% and 0.3% respectively (Figure 2B). Interestingly, although detectable, GJC1 is not negatively regulated during adenoviral infection (Figure 2B). Despite GJA5 mRNA reduction during adenoviral infection, protein levels are maintained at 24 hpi (Figure S1). To determine if Ad5 infection results in dysregulation of other critical junctional genes relevant to the cardiac intercalated disc, PKP2 (Plakophilin 2) and TJP1 (ZO-1) expression were analyzed. PKP2 mRNA levels are maintained while a reduction in TJP1 mRNA to 20% is detected at 24 hpi (Figure 2C).

Figure 2). Specific targeting of gap junction gene transcription during adenovirus type 5 infection.

HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and RNA was harvested at 24 hpi. A) RT-qPCR analysis of CDKN1A (p21) and SFN (14-3-3σ) to confirm active viral infection and known altered gene transcription. B) RT-qPCR analysis of gap junction family genes GJA1 (Cx43), GJA5 (Cx40), and GJC1 (Cx45). C) RT-qPCR analysis of junctional protein genes PKP2 (Plakophilin-2) and TJP1 (ZO-1). Statistical analysis performed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (n=3). *p≤0.05 **p≤0.01 ***p≤0.001 ****p<0.0001. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. See also Figure S1.

Early adenoviral factors induce β-catenin transcriptional activity through growth factor signaling.

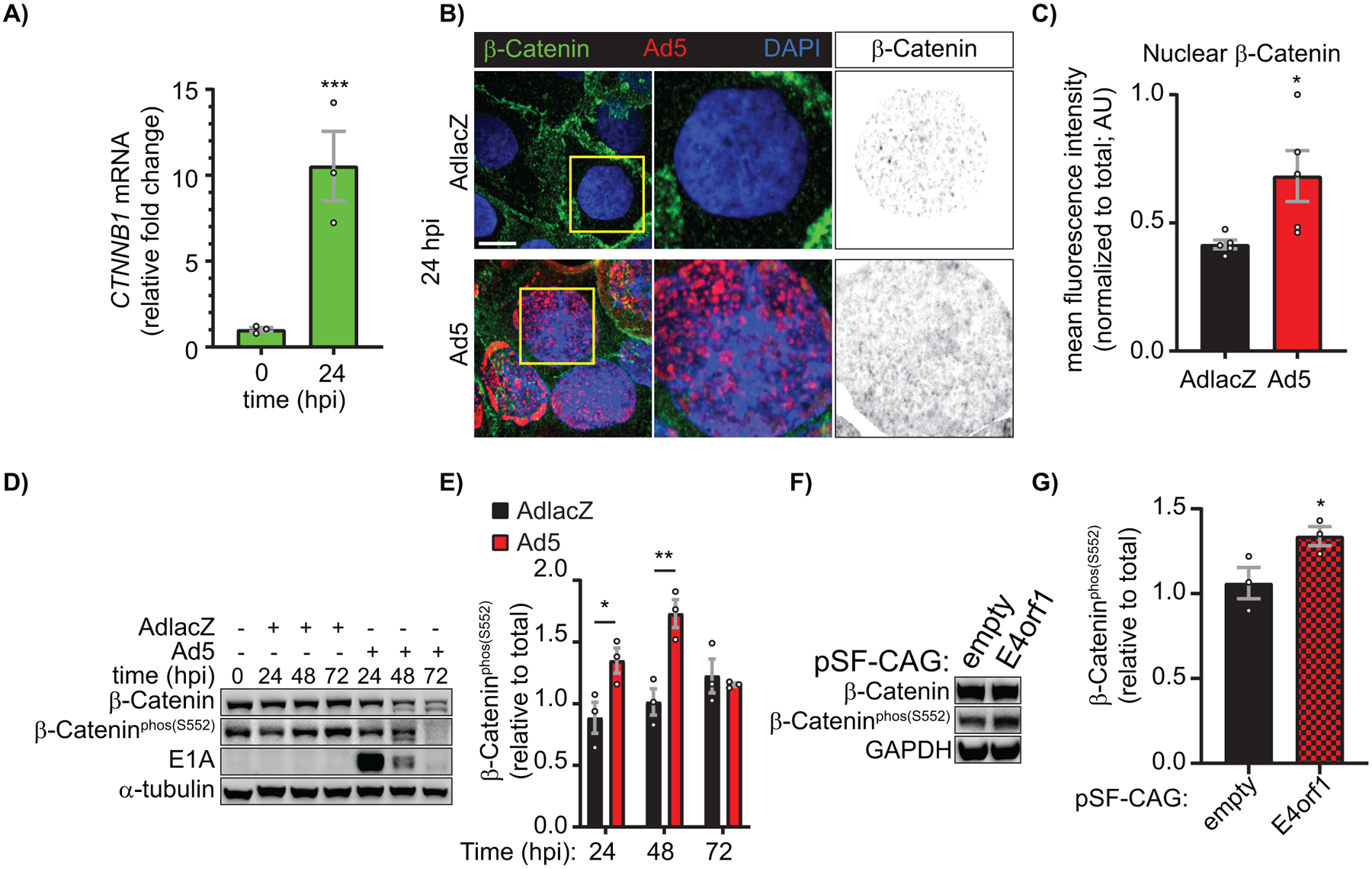

In order to determine the mechanism by which GJA1 is negatively regulated during Ad5 infection, RT-qPCR was performed on GJA1-known and -predicted transcription factors (19). CTNNB1 (β-catenin), TBX2 (T-Box 2), F2R (PAR-1) were found elevated 24 hpi (demonstrating global host-cell gene shutoff has not occurred at this early time point) (Supplemental Figure S3, Figure 3A). Given that β-catenin functions as both a transcription factor and a scaffolding protein shown to directly bind Cx43 (66, 67), localization of β-catenin was determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of AdlacZ- and Ad5-infected HaCaT cells 24 hpi (Figure 3B). Using single Z-position images, we find 64% increased nuclear β-catenin, as determined through binary mask generation and multiplication from DAPI signal (greyscale panels Figure 3B, quantified in 3C). To further validate increased nuclear β-catenin and associated transcriptional activity, phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser552 (β-cateninphos(S552)) by AKT which has previously been identified to result in translocation to the nucleus to effect transcriptional activity (68), was analyzed by western blot. We find a significant increase of 52% and 71% in β-cateninphos(S552) relative to total β-catenin at 24 and 48 hpi respectively (Figure 3D, quantified in 3E). Global effects on host cell RNA and protein would be occurring at later time points as viral assembly and cell lysis is underway so loss of significance at 72 hpi is expected. The adenoviral E4orf1 protein is known to activate AKT, leading us to ask if E4orf1 is sufficient to induce phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser552 (49, 53). In order to determine sufficiency, we transiently transfected HaCaT cells to overexpress adenoviral E4orf1 and analyzed β-cateninphos(S552) levels at 24 h post transfection where we find an increase of 28% (Figure 3F, quantified in 3G). Overexpression of adenoviral E4orf1 was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure S4).

Figure 3). Early adenoviral factors induce β-catenin transcriptional activity through growth factor signaling.

HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and RNA and protein were harvested or cells were fixed for immunofluorescence over a 72 h time course. A) RT-qPCR analysis of CTNNB1 (β-catenin) relative fold change from 0 hpi. (n=3). B) Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy for β-catenin (green) and Ad5 (red) with nuclei identified with DAPI (blue). Greyscale images in right panels identify nuclear β-catenin levels through DAPI binary mask multiplication from a single Z-slice. Original magnification: X100. Scale bar: 10μm. C) Quantification of nuclear β-catenin represented in B. (n=5). D) Western blot of total β-catenin and β-catenin phospho-Ser552 (transcriptionally active) also probed for Ad5-E1A to confirm infection and α-tubulin for loading control. E) Quantification of D by densitometry. (n=3). HaCaT cells were transfected with pSF-CAG-empty vector or -E4orf1 and protein harvested 24 hours post transfection. F) Western blot of total β-catenin and β-catenin phospho-Ser552 (transcriptionally active) also probed for GAPDH for loading control. G) Quantification of F by densitometry. (n=3). Statistical analyses performed using the unpaired Student’s t-test (A, C, G) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (E). *p≤0.05 **p≤0.01 ***p≤0.001 ****p<0.0001. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. See also Figure S2, S3.

β-catenin transcriptional activity is necessary for adenoviral Cx43 transcriptional suppression.

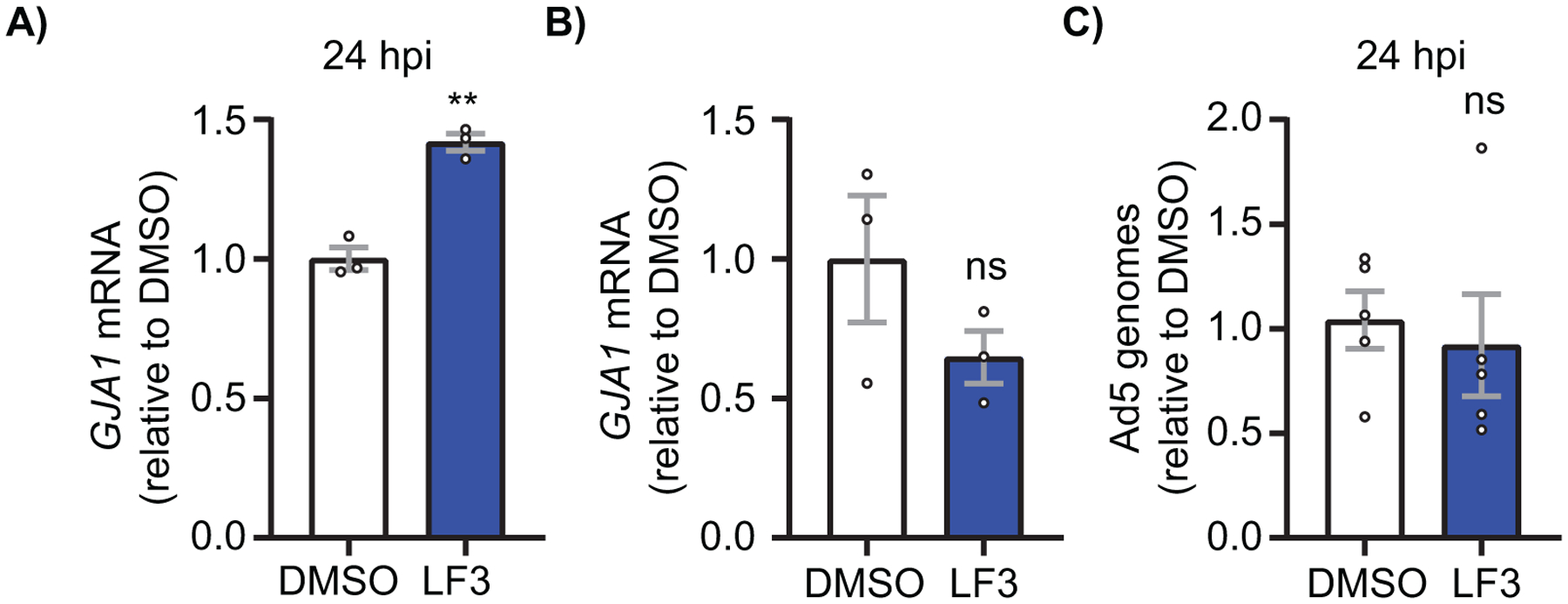

We next sought to determine if β-catenin transcriptional activity was necessary for reduced GJA1 mRNA during Ad5 infection in HaCaT cells. GJA1 mRNA levels are rescued by 42% in Ad5-infected HaCaT cells 24 hpi treated with LF3, a specific small molecule inhibitor of β-catenin transcriptional activity (69, 70), compared to DMSO treated infected cells (Figure 4A). In order to determine effects of LF3 alone in the absence of adenoviral infection on GJA1 mRNA levels, we treated uninfected HaCaT cells with LF3 for 24 h and find no significant change in GJA1 mRNA. Although not statistically significant but trending, LF3 in the absence of adenoviral infection appears to decrease GJA1 mRNA, potentially supporting previous findings which describe β-catenin as a classical transcriptional activator of GJA1 (71). Finally, we tested if LF3 alters viral replication kinetics and performed qPCR of adenoviral genomes 24 hpi in Ad5-infected, LF3-treated, HaCaT cells where no change in adenoviral replication kinetics was detected when compared to Ad5-infected, DMSO-treated controls (Figure 4C). In conclusion, inhibition of β-catenin transcriptional activity with LF3 is sufficient to rescue GJA1 mRNA levels during adenoviral infection independent of viral life cycle progression.

Figure 4). β-catenin transcriptional activity is necessary to reduce GJA1 mRNA during adenoviral infection.

HaCaT cells were treated with the β-catenin transcriptional inhibitor LF3 1 hpi or LF3 alone and harvested for RNA and DNA at indicated time points. A) RT-qPCR analysis of GJA1 mRNA at 24 hpi in cells treated with LF3 or vehicle and infected at a MOI of 10 iu/cell. (n=3). B) RT-qPCR analysis of uninfected HaCaT cells treated with vehicle or LF3 for 24 h. (n=3). C) qPCR analysis of viral genomes in HaCaT cells infected with Ad5 and treated with LF3 or vehicle and harvested 24 hpi. (n=5). ns: not significant. Statistical analyses performed using the unpaired Student’s t test. p≤0.05 is considered statistically significant. **p≤0.01. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

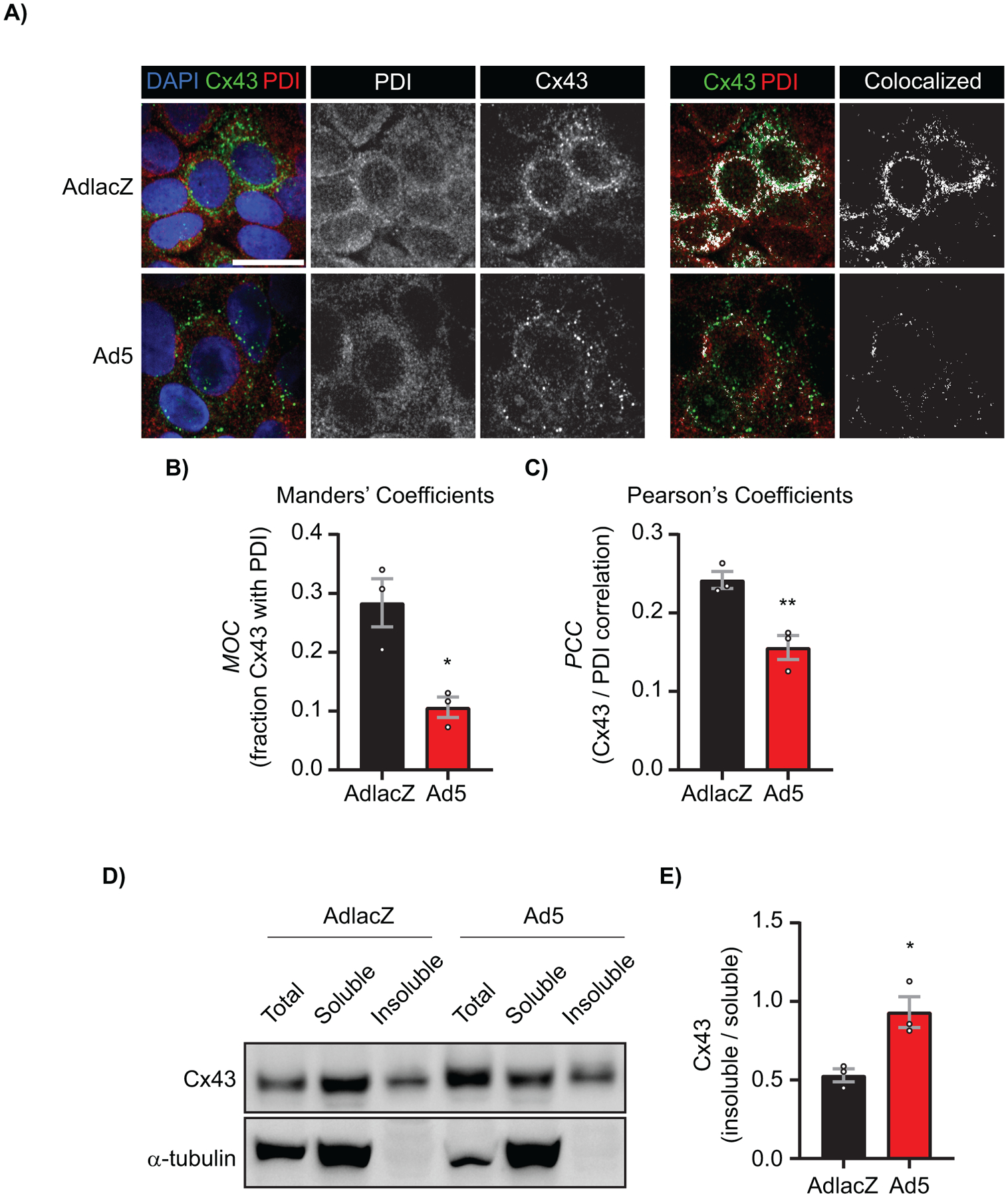

Cx43 protein occurs in reduced levels at the endoplasmic reticulum and is primarily junctional during adenovirus infection.

We next asked if Cx43 trafficking and localization were altered early during adenoviral infection. In order to determine if Cx43 is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and therefore subjected to altered forward trafficking during adenoviral infection, HaCaT cells were infected with AdlacZ or Ad5 followed by fixation and labeled for Cx43 and the ER resident protein, Protein Disulfide Isomerise (PDI) for colocalization analysis (Figure 5A). Changes in colocalization were quantified utilizing Manders’ cooccurrence and Pearson’s correlation functions and demonstrate a 36% reduction in Manders’ Coefficients and a 62% reduction in Pearson’s Coefficients in Ad5-infected HaCaT cells compared to AdlacZ-infected control cells at 24 hpi (Figure 5B, 5C). Given that there is less Cx43 colocalized with the ER of Ad5-infected HaCaT cells, we next sought to determine changes in junctional status of Cx43 (ie. cytosolic or membrane Cx43 compared to gap junction Cx43) by Triton solubility fractionation. We find a 76% increase in the insoluble / soluble Cx43 ratio in Ad5-infected HaCaT cells compared to AdlacZ-infected control cells at 24 hpi, signifying that remaining Cx43 is primarily within gap junction structures during adenoviral infection (Figure 5D, quantified in 5E).

Figure 5). Cx43 protein occurs in reduced levels at the endoplasmic reticulum and is primarily junctional during adenovirus infection.

HaCaT cells were infected with AdlacZ or Ad5 at a MOI of 10 iu/cell prior to fixation or protein harvesting at 24 hpi. A) AdlacZ- or Ad5-infected HaCaT cells were immunolabeled against PDI (red) to localize ER and against Cx43 (green). Cells were stained using DAPI to identify nuclei (blue). Colocalized Cx43 / PDI signal was determined with ImageJ (white). Original magnification: X100. Scale bar: 20 μm. B) Manders’ Coefficients calculations determined using fraction Cx43 with PDI. Data points represent averages of 8 images from 3 separate experiments. C) Pearson’s Coefficients calculations determined for Cx43 and PDI correlation. Data points represent averages of 8 images from 3 separate experiments. D) AdlacZ- or Ad5-infected HaCaT cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100 solubility assay buffer prior to fractionation and western blotting. Membrane probed against Cx43 (top panel) and α-tubulin (bottom panel) for loading control. E) Quantification of D. Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t-test. (n=3). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

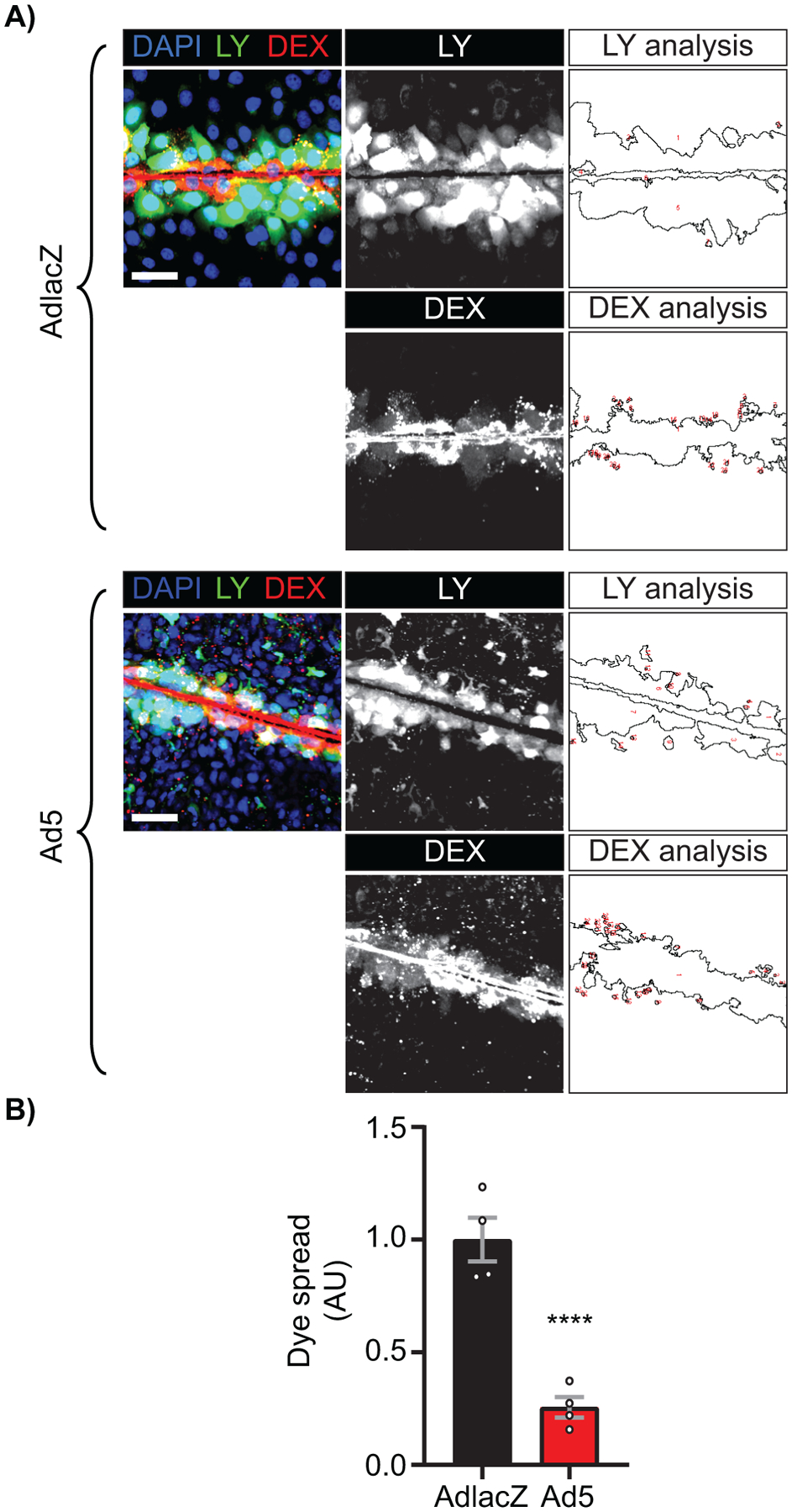

Adenovirus inhibits gap junction intercellular communication prior to reduction of Cx43 total protein levels during infection.

In order to determine if there is a functional change in GJIC, AdlacZ- or Ad5-infected HaCaT cells were analyzed by scrape-loading and dye-transfer of gap junction permeable 442 Da. Lucifer yellow (LY) and gap junction impermeable 10,000 Da. Dextran-Alexa Fluor 647 (Dex-647). Dye spread is found to be significantly reduced by 66% at 24 hpi, coinciding with reductions in Cx43 protein levels (Supplemental Figure S5A, quantified in S5B, Figure 1C). In addition to transcriptional and translational regulation, previous studies have demonstrated post-translational modifications of Cx43 in regulation of trafficking, internalization, gap junction permeability, and channel conductance (15, 23, 25, 27, 54, 72–75). Given that channel function can be altered independently of total protein level, we performed scrape-load dye-transfer assays on Ad5-infected HaCaT cells at 12 hpi, prior to detectable reductions in total Cx43 protein levels (Supplemental Figure S5C, quantified in S5D). We find a significant reduction in dye spread in Ad5-infected cells compared to AdlacZ-infected controls by 69% at 12 hpi indicating direct targeting of Cx43 gap junction channel function during Ad5 infection (Figure 6A, quantified in 6B).

Figure 6). Adenovirus inhibits gap junction intercellular communication prior to reduction of Cx43 total protein levels during infection.

HaCaT cells were plated to confluence on glass bottomed dishes and infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell. The Lucifer yellow (LY) scrape-load dye-transfer assay was performed at 12 hpi with 10,000 MW Dextran-AlexaFluor647 (Dex-647) as a gap junction non-permeable control. A) Representative confocal microscopy images of LY (green) and Dex-647 (red) transfer with nuclei identified with DAPI (blue). Middle greyscale panels show LY and Dex-647 alone and right panels illustrate quantification of each dye spread. Original magnification: X20. Scale bar: 50μm. B) Quantification of dye spread in A. Statistical analysis was performed with the unpaired Student’s t-test. (n=4). ****p<0.0001. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. See also Figure S4.

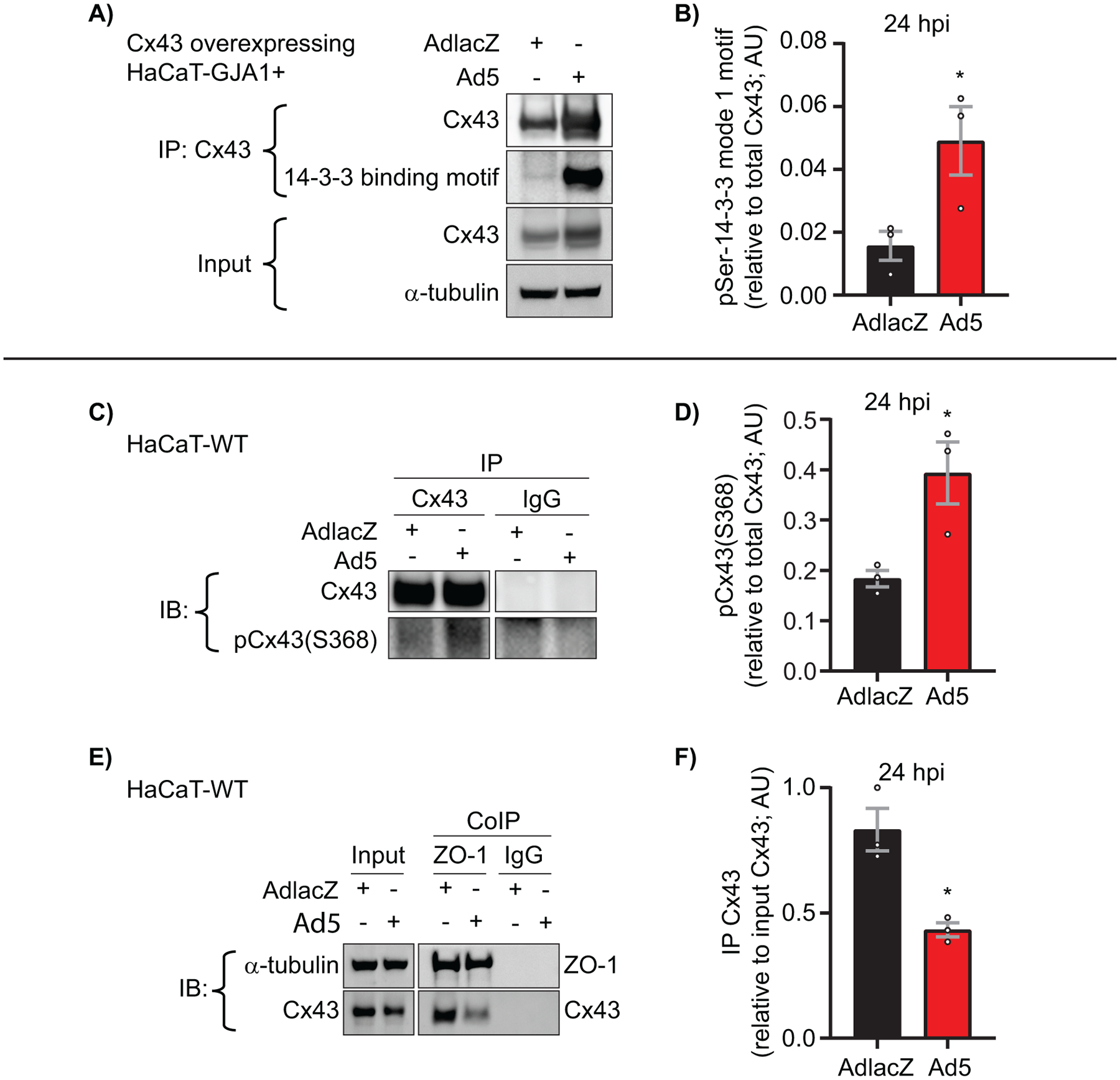

Direct targeting of Cx43 gap junctions through phosphorylation during adenovirus type 5 infection.

In addition to using wild-type HaCaT (HaCaT-WT) cells, we used lentiviral transduction to establish clonal HaCaT cells over-expressing GJA1 (HaCaT-GJA1+) to circumvent reduced Cx43 levels during Ad5 infection and better enable the interrogation of Cx43 phosphorylation status. AdlacZ- or Ad5-infected wild-type HaCaT (HaCaT-WT) and HaCaT-GJA1+ cells were analyzed for phosphorylation events known to impact channel opening probability, complexing with other proteins, and internalization. Phosphorylation of Cx43 at Ser373 by AKT creates a mode-1 14-3-3 binding motif which leads to decreased interaction of Cx43 with ZO-1 (26–28). Subsequent phosphorylation of Cx43 at Ser368 by PKC results in reduced channel open probability and/or altered conduction properties (54, 73, 76, 77). From infected HaCaT-GJA1+ cells, Cx43 was immunoprecipitated followed by western blotting for phospho-Serine-14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif which we find increased by 213% at 24 hpi (Figure 7A, quantified in 7B). This antibody has previously been demonstrated as specific for phosphorylation of Cx43 at Ser373 through site-directed mutagenesis (27). Cx43 was immunoprecipitated from AdlacZ- and Ad5-infected HaCaT-WT cell lysates followed by western blotting for Cx43 phosphorylated at Ser368 and total Cx43 where we find increased Ser368 phosphorylation of 114% (Figure 7C, quantified in 7D).The AKT phosphorylated 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif Ser373 of Cx43 has been reported to disrupt interaction between Cx43 and ZO-1(28). Cx43/ZO-1 complexing was analyzed in Ad5- or AdlacZ-infected HaCaT-WT cells by coimmunoprecipitating ZO-1 and immunoblotting for Cx43 where we find reduced Cx43 coimmunoprecipitated with ZO-1 relative to input Cx43, supporting our phosphoSerine-14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif findings in HaCaT-GJA1+ cells (Figure 7E, quantified in 7F). The MAPK phosphorylation site of Cx43 at Ser262 (pCx43S262) has been identified as downstream of Ser373/Ser368 phosphorylation and is a key event in the internalization and subsequent degradation of Cx43 (25, 27, 72). Interestingly, in Ad5-infected HaCaT-GJA1+ and HaCaT-WT cells we do not find increased Cx43 phosphorylation at Ser262 (Figure S6). Furthermore, we find increased total Cx43 in Ad5 infected HaCaT-GJA1+ cells supporting our finding that endogenous Cx43 is targeted at the transcriptional level, and not directly targeted for degradation during infection resulting in Cx43 being maintained in gap junctions.

Figure 7). Direct targeting of Cx43 gap junctions through phosphorylation during adenovirus type 5 infection.

HaCaT-GJA1+ cells or wild-type HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein was harvested at 24 hpi. A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of Cx43 followed by western blot probed for phosphoSerine-14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif to detect phosphorylation of Cx43-Ser373 at 24 hpi. α-tubulin serves as loading control. B) Densitometry analysis of A. C) IP of Cx43 followed by western blot for Cx43 phosphorylation at Ser368. Cx43 IP and IgG IP are from same membrane. D) Densitometry analysis of C. E) HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein harvested 24 hpi. Co-immunoprecipitation (CoIP) was performed for ZO-1 and Cx43 followed by western blotting. α-tubulin serves as loading control. F) Densitometry analysis of E. Statistical analysis performed with the unpaired Student’s t-test. (n=3). *p≤0.05 **p≤0.01 ***p≤0.001 ****p<0.0001. Data are represented as mean ±SEM. See also Figure S5.

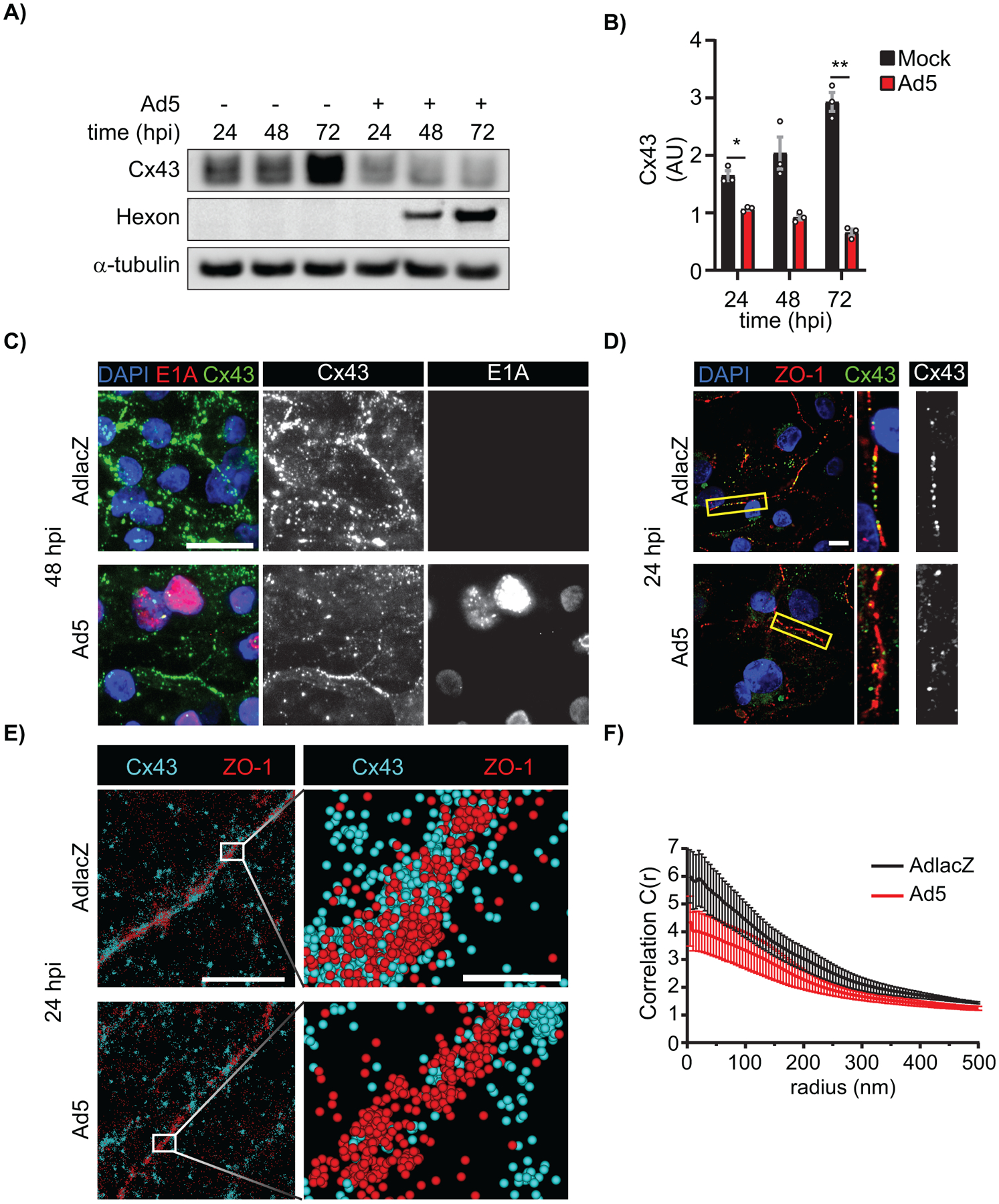

Ad5 targets Cx43 in cardiomyocytes and induces Cx43-gap junction remodeling.

We next sought to determine if Cx43 expression and Cx43-gap junction remodeling occurred in Ad5-infected cardiomyocytes and could thereby contribute to arrhythmogenic potential in infected hearts. HiPSC-CMs were infected with AdlacZ or Ad5 at a MOI of 10 iu/cell prior to harvesting protein or fixing for microscopy analysis. Recapitulating our findings in HaCaT cells, we find 35% reduced Cx43 protein levels in Ad5-infected cardiomyocytes at 24 hpi compared to mock-infected controls (Figure 8A, quantified in 8B). HiPSC-CMs were analyzed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy to specifically determine Ad5 induced reductions to cytoplasmic or membrane localized Cx43 in which we find global reductions 48 hpi (Figure 8C). Cx43 interactions with ZO-1 is experimentally described to increase gap junction plaque size, stabilize gap junctions, generate functional gap junctions in cardiomyocytes, and is also altered in failing human hearts (30, 32, 78–81). Alterations in Cx43 gap junctions and ZO-1 localization were assayed in HiPSC-CMs by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy and STORM super-resolution localization 24 hpi. In single Z-position data capture, there is a reduced Cx43 co-localization with ZO-1 at cell-cell borders by confocal microscopy (Figure 8D). In order to quantify Cx43/ZO-1 complexing in situ, we turned to super resolution localization measurements. To assess effects on Cx43/ZO-1 interaction, cross-pair correlation functions were generated from STORM data. The probability of localizing two distinct target molecules together at a given distance with a function value of 1 is interpreted as no correlation, while increased function values greater than 1 confirm complexing between molecules. By cross-pair correlation analysis we find reduced probability of Cx43/ZO-1 interaction in Ad5-infected HiPSC-CMs compared to AdlacZ controls at 24 hpi (Figure 8E, quantified in 8F). Cx43/ZO-1 STORM data in HiPSC-CMs parallels CoIP data in HaCaT cells where loss of Cx43/ZO-1 complexing was found (Figure 7E, 7F).

Figure 8). Ad5 targets Cx43 in cardiomyocytes and induces Cx43-gap junction remodeling.

HiPSC-CMs were infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein harvested or fixed for immunolabeling over a 72 h time course. A) Western blot probed for Cx43 expression in HiPSC-CMs. Detection of Ad5-Hexon protein expression serves to confirm infection and α-tubulin serves as loading control. B) Densitometry analysis of A. C) Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of HiPSC-CMs at 48 hpi probed for Cx43 (green) and adenovirus E1A (red) with nuclei identified using DAPI (blue). Original magnification: X100. Scale bar: 20μm. D) Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of HiPSC-CMs 24 hpi probed for Cx43 (green) and ZO-1 (red) with nuclei identified using DAPI (blue). Original magnification: X100. Scale bar: 10μm. Images representative of 3 separate experiments. E) Super resolution stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) derived point-cloud localizations of Cx43 (cyan) and ZO-1 (red) in Ad5- and AdlacZ-infected HiPSC-CMs 24 hpi. Zoomed out panels (left) scale bar: 2μm. Zoomed in panels (right) scale bar: 200nm. Sphere size: 30nm. F) Cross-Pair correlation functions for Cx43/ZO-1 complexing in E. (n=10). Statistical analysis was performed with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (B) (n=3). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p<0.0001. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

DISCUSSION

Viral subversion of intracellular processes is a topic of intense study covering mechanisms by which viruses hijack cellular machinery to replicate and assemble progeny. There is now growing interest in manipulation of intercellular junctions by viruses and how events within infected cells precipitate alterations in cell-cell coupling. Such disruptions in intercellular junctions likely contribute to mild symptoms in the respiratory system for example, but in organs relying on intercellular communication for function, such as the heart, resulting disturbances in electrical coupling would be arrhythmogenic and potentially fatal. Targeting of gap junctions has been previously reported for several viruses but our understanding of underlying mechanisms for gap junction targeting is limited (82–87). Prior research demonstrates, in the context of adenoviral vector-mediated transduction, that the adenovirus E4 gene products regulate Cx40 and Cx43 inversely through PKA and PI3K signaling (48). Here, we report changes in Cx43 expression occurs more rapidly during wild type Ad5 infection. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that during a wild type Ad5 infection, Cx43 and Cx40 are both negatively regulated at the mRNA level, revealing differences that may only be apparent in the context of active replication where all viral genes are working cooperatively, as would be the case in an infected heart. (48). At the protein level, we find Cx43 but not Cx40 or Cx45 to be significantly downregulated during adenoviral infection and therefore focus on Cx43 modulation for the majority of this study. Despite no detectable loss of Cx45 at the protein level in HaCaT cells, we reveal reductions in CAR during adenoviral infection which, in the context of cardiac infection, could potentially have an indirect effect on Cx45 localization and function in atrioventricular conduction as previously identified (33, 88). E1 genes are deleted in adenoviral vectors to prevent transactivation of adenoviral genes, including E4, which may contribute to observed temporal differences, and highlights that while the Zhang et al study is relevant to use of adenoviral vectors in gene transduction, it is not necessarily informative regarding wild type adenoviral pathogenesis (89–91).

The adenoviral life cycle length is dependent on cell type, and in the laboratory replication and assembly of viral progeny temporally accelerated in transformed or tumorigenic cell lines. Cytopathic effect was only apparent from 60 hpi in the immortalized HaCaT cells and terminally differentiated HiPSC-CMs used in this study. Our findings of altered gap junction function and suppression of Cx43 transcription occur within 12–24 hpi when cells would still be metabolically active and virally induced host-cell global repression is incomplete. We include later time points in Figures 1, 3, and 8 to provide greater temporal context over the whole viral replication and cell lysis cycle.

Cx43 transcriptional regulation is a complex process orchestrated through cell type-dependent and -independent transcription factors. For example, Nkx2.5 activation of GJA1 expression can be repressed by Irx3, which concomitantly acts as an activator for GJA5 (Cx40), highlighting the fine-tuned transcriptional control of gap junction genes (17). We find repression of Cx43 and Cx40 transcription during Ad5 infection while Cx45 mRNA levels are maintained. Indeed, work by several groups has focused on transcription factors involved in Cx43 and Cx40 with less known about Cx45 transcriptional regulation, partly due to the ambiguity of the Cx45 promoter by functional analysis (19, 92). Van der Heyden et al. demonstrated Cx43 is likely a Wnt1 signaling target while there were no changes to Cx45 expression providing an example of connexin isotype-specific transcriptional regulation (71). Furthermore, host-cell chromatin remodeling during adenoviral infection is an established mechanism of silencing cellular host genes and it is possible that Cx43 and/or Cx40 but not Cx45 transcription is suppressed through chromatin remodeling involving adenoviral E1A or adenoviral E4-orf3 related mechanisms (93–95).

Of GJA1 known and predicted transcription factors, β-catenin is particularly relevant given its multifaceted roles in complexing with Cx43 as a scaffolding protein and classical definition as an activating transcription factor for GJA1 (18, 66, 67, 71). Exquisite subversion of host cell transcriptional machinery by adenoviral proteins encompasses a breadth of strategies from chromatin remodeling to render target genes inaccessible to direct manipulation of transcription factor function (63, 89, 96–98). One example of direct manipulation of a transcription factor is phosphorylation of β-catenin by AKT, a well described target of adenoviral E4orf1 (53, 71). We find increased β-catenin nuclear translocation by immunofluorescence and confirm GJA1 transcriptional repression is dependent on β-catenin transcriptional activity using LF3, a small molecule inhibitor of β-catenin/TCF/Lef complex transcriptional activity (69, 70). Furthermore, adenoviral E4orf1 expression alone induces a comparable phosphorylation of β-catenin as achieved during Ad5 infection demonstrating sufficiency to directly affect the function of β-catenin. Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is reported in positive regulation of Gja1 in murine arteries and transcriptionally active β-catenin is known to lead to inhibition of NF-κB function (99, 100). One mechanism for indirect targeting of Cx43 expression by adenovirus could therefore involve this NF-κB/β-catenin axis. Direct suppression of GJA1 through β-catenin has not yet been described although repressive transcription cofactors have been identified including Reptin52 (complexing as β-catenin/Reptin52/TATA box binding protein), ICAT (inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF-4), and chibby, which may provide a means for direct transcriptional suppression during adenoviral infection (66, 101–103). Our findings demonstrating a previously undefined role for β-catenin in repression of GJA1 transcription, as opposed to the previously reported positive regulatory role (18), highlight the potential for studying Cx43 biology in the context of viral infection as a powerful tool in elucidation of critical cellular mechanisms of gap junction regulation.

As gap junctions facilitate the exchange of antiviral molecules including MHC class I peptides and cGAMP (6, 7, 104), GJIC is an attractive target for viruses, including Ad5, as a means to limit antiviral responses by reducing recruitment of immune cells and limiting the interferon response (9, 105, 106). Gap junction function can be modulated directly and independent of protein levels by post-translational modifications with extensive studies focusing on phosphorylation. Several signal transduction cascades associated with growth factor signaling and known to act on the Cx43 C-terminus are activated during Ad5 infection to mimic growth factor signaling. Specifically the E4orf1 and E4orf4 proteins ensure robust activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway which is well described in modulation of gap junction localization and function (27, 107). AKT phosphorylation at Ser373 is involved in Cx43 hemichannel recruitment into the gap junction proper but also represents initiation of a cascade leading to channel internalization and degradation (27, 28). PKC phosphorylation at Ser368 is associated with reduced channel open probability and is subject to cis-gatekeeper events involving Ser373 phosphorylation but Ser365 dephosphorylation (54, 108, 109). Subsequent phosphorylation of Cx43 by MAPK at residues including Ser255/262/279/282 is associated with internalization and eventual degradation (27, 72, 110, 111). We established HaCaT cells overexpressing GJA1 in order to circumvent transcriptional suppression during adenoviral infection to assay post-translational modifications to identify increased phosphorylation at Cx43 Ser373 but no induction of phosphorylation at MAPK-associated residues. The fact that Cx43 levels actually increase in these cells during Ad5 infection suggest that while transcriptional suppression of Cx43 occurs, direct targeting of the Cx43 protein through phosphorylation by adenovirus is restricted to limiting channel function and not induction of gap junction internalization and degradation. In agreement with our Cx43 Ser373 and Ser262 phosphorylation data is the finding that Cx43 is primarily junctional during adenoviral infection with reduced ER localization, supporting a model where de novo Cx43 synthesis is reduced and Cx43 is maintained in de facto gap junctions.

While the aforementioned phosphorylation events have direct effects on channel function and therefore electrical coupling, phosphorylation status also dynamically alters Cx43 complexing with other scaffolding and membrane proteins. Specifically, Cx43 interacting proteins c-Src, ZO-1, ZO-2, Occludin, Claudin-5, β-catenin, p120, N-Cadherin, Plakophilin-2, Ankyrin-G, NaV1.5, and mAChR, regulate gap junction function whereby complexing is reportedly regulated through phosphorylation of the Cx43 C-terminus (18, 79, 112–120). We report increased phosphorylation of Cx43 at Ser373 during Ad5 infection, an event that can alter Cx43/ZO-1 complexing and therefore tightly associated with incorporation into, and removal from, the gap junction plaque (28, 29, 31, 32, 74, 81). We confirm this dissociation by co-immunoprecipitation and our STORM data in infected cardiomyocytes also reveal reduced Cx43/ZO-1 complexing, signifying pathological remodeling that could contribute to arrhythmogenesis. Beyond the gap junction, cross-talk between junctional proteins and ion channels at the cardiomyocyte intercellular junction occurs on many levels. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that loss of Cx43 C-terminus results in disturbed NaV1.5 trafficking and sodium current, further providing evidence for the changes we describe during acute adenoviral infection and Cx43 phosphorylation contributing to the arrhythmogenic substrate (119). HiPSC-CMs now provide a model cell system in which to interrogate the impact of human adenoviral infection on excitable cells and tissues, where disruption of highly ordered intercellular structures has substantially more severe and life-threatening effects on organ function than in epithelia, for example.

Current understanding relating to viral infection of the heart predominantly focuses on chronic infection, or end-stage disease often related to immune-related global cardiac remodeling, dilated cardiomyopathy, and even sometimes post viral clearance (36, 121). Here, we identify a rapid shut down in intercellular communication through direct and indirect targeting of Cx43 gap junctions during adenoviral infection that, in cardiomyocytes, would contribute to an arrhythmogenic substrate. Our findings therefore provide mechanistic insight into arrhythmogenesis in the context of acute infection, where sudden cardiac death in young adults is increasing attributed to adenovirus (34, 35). In addition to animal models utilizing human Coxsackievirus B3, a murine model of viral myocarditis induced by mouse adenovirus has been developed. Mouse adenovirus serotype 1 (MAV-1) infection demonstrates interferon gamma and immunoproteasome activity induce cardiac damage in a chronic infection model in vivo (46, 47). Furthermore, increases in mortality in neonatal mice by MAV-1 is independent of viral load, inflammatory cytokine expression, or invading leukocytes, validating the need to understand acute viral pathogenesis prior to adaptive immune system cytotoxicity (45). While development of an animal model is necessary to truly isolate viral- vs immune-mediated effects, HiPSC-CMs provide a powerful system in which to examine effects of human viral infection on human heart muscle cells. Disruption of viral manipulation of cellular pathways identified here may inform design of therapeutics to protect against sudden cardiac death during infection. More broadly, as we further understand adenoviral manipulation of Cx43 and gap junctions, critical cellular pathways regulating this important cellular function will be elucidated with implications in all organ systems and disease states beyond cardiomyopathies.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1) Specific host-cell proteins are targeting during adenoviral infection. Related to Figure 1 and 2. HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein lysates harvested at 0 hpi and 24 hpi followed by western blotting. A) Western blot probed against E-Cadherin (top panel) and CAR (center panel) with α-tubulin probed for a loading control (bottom panel). B) Quantification of A. C) Western blot probed against RPL22 (top panel) with α-tubulin probed for a loading control (bottom panel). D) Quantification of C. E) Western blot probed against Cx45 (top panel) and Cx43 (center panel) with α-tubulin probed for a loading control (bottom panel). F) Quantification of E. G) Western blot probed against Cx40 (top panel) with α-tubulin probed for a loading control (bottom panel). H) Quantification of G. Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t-test. (n=3). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

Figure S2) GJA1 expression is higher than GJA5 and GJC1 in untreated HaCaT cells. Related to Figure 2. RT-qPCR was performed on HaCaT cells to determine baseline expression of GJA1, GJA5, and GJC1. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (n=3). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

Figure S3) GJA1-candidate transcription factors are elevated during Ad5 infection. Related to Figure 3. HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and RNA harvested at 24 hpi. RT-qPCR analysis of Ad5-infected HaCaT cells for transcription factor genes TBX2 and F2R which are previously shown to regulate GJA1 transcription relative to 0 hpi. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

Figure S4) Detection of E4orf1 mRNA in transfected HaCaT cells. Related to Figure 3. HaCaT cells were transfected with pSF-CAG-empty or -E4orf1 and RNA harvested 24 hours post transfection. E4orf1 is detected by RT-qPCR in transfected HaCaT cells. n=3. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

Figure S5) Adenovirus infection reduces gap junction function. Related to Figure 6. HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdLacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein was harvested at 6 and 12 hpi in addition to LY scrape-load dye-transfer assay at 24 hpi. A) Representative confocal microscopy images of LY (green) and Dex-647 (red) transfer with nuclei identified with DAPI (blue). Middle greyscale panels show LY or Dex-647 alone and right panels illustrate quantification of each dye spread. Original magnification: X20. Scale bar: 50μm. B) Quantification of A (n=3). C) Western blot probed for Cx43 expression with α-tubulin serving as loading control. D) Densitometric analysis of C (n=3). Statistical analysis performed by unpaired Student’s t-test (B) or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (D). *p≤0.05, ns: not significant. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

Figure S6) Adenovirus does not induce Cx43 phosphorylation at Ser262. Related to Figure 7. A) HaCaT-GJA1+ cells were infected with Ad5 at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein harvested 6, 12, and 24 hpi. Immunoprecipitation of Cx43 was performed following by western blot and probed for Cx43 phosphorylation at Ser262 (pCx43(S262)) and total Cx43. Immunoprecipitated Cx43 and IgG are from same membrane and exposure. Detection of Hexon confirms infection and α-tubulin serves as loading control. B) Densitometry of A. C) Wild-type HaCaT cells were infected with Ad5 or replication-incompetent AdlacZ at a MOI of 10 iu/cell and protein harvested 24 hpi. Immunoprecipitation of Cx43 was performed followed by western blot and probed for pCx43(S262) and total Cx43. Immunoprecipitated Cx43 and IgG are from same membrane and exposure. D) Densitometry of C. Statistical analyses performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. (n=3). p≤0.05 is considered statistically significant. ns: not significant. Data are represented as mean ±SEM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. David Ornelles (Wake Forest School of Medicine, Microbiology and Immunology) for providing adenovirus reagents and helpful discussion. Dr. Allison N. Tegge (Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, Department of Statistics, Virginia Tech) for consultation on statistical methods used and Dr. Samy Lamouille for critical review of this manuscript (Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Tech). This work was supported by a NIH NHLBI R01 grant (HL132236 to J.W.S.), an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (18PRE33960573 to P.J.C.), a NHLBI F31 grant (HL140909 to C.C.J.), and a NHLBI F31 grant (HL152649 to R.L.P.).

NONSTANDARD ABBREVIATIONS

- Cx43

Connexin43

- GJIC

Gap junction intercellular communication

- E4orf1

E4 open reading frame 1

- HiPSC-CM

Human induced pluripotent stem cell derived-cardiomyocyte

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- iu

Infectious units

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Unwin PN, and Zampighi G (1980) Structure of the junction between communicating cells. Nature 283, 545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vozzi C, Dupont E, Coppen SR, Yeh HI, and Severs NJ (1999) Chamber-related differences in connexin expression in the human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 31, 991–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, and Fishman GI (2001) Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circulation research 88, 333–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanagaratnam P, Rothery S, Patel P, Severs NJ, and Peters NS (2002) Relative expression of immunolocalized connexins 40 and 43 correlates with human atrial conduction properties. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 39, 116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poelzing S, and Rosenbaum DS (2004) Altered connexin43 expression produces arrhythmia substrate in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287, H1762–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ablasser A, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hemmerling I, Horvath GL, Schmidt T, Latz E, and Hornung V (2013) Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nature 503, 530–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neijssen J, Herberts C, Drijfhout JW, Reits E, Janssen L, and Neefjes J (2005) Cross-presentation by intercellular peptide transfer through gap junctions. Nature 434, 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SJ, King KR, Casali M, and Yarmush ML (2009) DNA-triggered innate immune responses are propagated by gap junction communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, and Rice CM (2011) A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472, 481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma S, tenOever BR, Grandvaux N, Zhou G-P, Lin R, and Hiscott J (2003) Triggering the Interferon Antiviral Response Through an IKK-Related Pathway. Science 300, 1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsend AR, Rothbard J, Gotch FM, Bahadur G, Wraith D, and McMichael AJ (1986) The epitopes of influenza nucleoprotein recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes can be defined with short synthetic peptides. Cell 44, 959–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braciale TJ, Morrison LA, Sweetser MT, Sambrook J, Gething MJ, and Braciale VL (1987) Antigen presentation pathways to class I and class II MHC-restricted T lymphocytes. Immunological reviews 98, 95–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zinkernagel RM, and Doherty PC (1974) Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature 248, 701–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beardslee MA, Laing JG, Beyer EC, and Saffitz JE (1998) Rapid turnover of connexin43 in the adult rat heart. Circ Res 83, 629–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laird DW, Castillo M, and Kasprzak L (1995) Gap junction turnover, intracellular trafficking, and phosphorylation of connexin43 in brefeldin A-treated rat mammary tumor cells. J Cell Biol 131, 1193–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallon RF, and Goodenough DA (1981) Five-hour half-life of mouse liver gap-junction protein. J Cell Biol 90, 521–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang SS, Kim KH, Rosen A, Smyth JW, Sakuma R, Delgado-Olguin P, Davis M, Chi NC, Puviindran V, Gaborit N, Sukonnik T, Wylie JN, Brand-Arzamendi K, Farman GP, Kim J, Rose RA, Marsden PA, Zhu Y, Zhou YQ, Miquerol L, Henkelman RM, Stainier DY, Shaw RM, Hui CC, Bruneau BG, and Backx PH (2011) Iroquois homeobox gene 3 establishes fast conduction in the cardiac His-Purkinje network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 13576–13581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ai Z, Fischer A, Spray DC, Brown AM, and Fishman GI (2000) Wnt-1 regulation of connexin43 in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest 105, 161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyamada M, Takebe K, and Oyamada Y (2013) Regulation of connexin expression by transcription factors and epigenetic mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828, 118–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James CC, Zeitz MJ, Calhoun PJ, Lamouille S, and Smyth JW (2018) Altered translation initiation of Gja1 limits gap junction formation during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Molecular biology of the cell [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyth JW, and Shaw RM (2013) Autoregulation of connexin43 gap junction formation by internally translated isoforms. Cell Rep 5, 611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeitz MJ, Calhoun PJ, James CC, Taetzsch T, George KK, Robel S, Valdez G, and Smyth JW (2019) Dynamic UTR Usage Regulates Alternative Translation to Modulate Gap Junction Formation during Stress and Aging. Cell reports 27, 2737–2747 e2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laird DW (2005) Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction internalization and degradation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1711, 172–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno AP, and Lau AF (2007) Gap junction channel gating modulated through protein phosphorylation. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 94, 107–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solan JL, and Lampe PD (2007) Key connexin 43 phosphorylation events regulate the gap junction life cycle. J Membr Biol 217, 35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park DJ, Wallick CJ, Martyn KD, Lau AF, Jin C, and Warn-Cramer BJ (2007) Akt phosphorylates Connexin43 on Ser373, a “mode-1” binding site for 14-3-3. Cell communication & adhesion 14, 211–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smyth JW, Zhang SS, Sanchez JM, Lamouille S, Vogan JM, Hesketh GG, Hong T, Tomaselli GF, and Shaw RM (2014) A 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif initiates gap junction internalization during acute cardiac ischemia. Traffic 15, 684–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn CA, and Lampe PD (2014) Injury-triggered Akt phosphorylation of Cx43: a ZO-1-driven molecular switch that regulates gap junction size. J Cell Sci 127, 455–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segretain D, Fiorini C, Decrouy X, Defamie N, Prat JR, and Pointis G (2004) A proposed role for ZO-1 in targeting connexin 43 gap junctions to the endocytic pathway. Biochimie 86, 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barker RJ, Price RL, and Gourdie RG (2002) Increased association of ZO-1 with connexin43 during remodeling of cardiac gap junctions. Circ Res 90, 317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhett JM, Jourdan J, and Gourdie RG (2011) Connexin 43 connexon to gap junction transition is regulated by zonula occludens-1. Molecular biology of the cell 22, 1516–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyofuku T, Yabuki M, Otsu K, Kuzuya T, Hori M, and Tada M (1998) Direct association of the gap junction protein connexin-43 with ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 273, 12725–12731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisewski U, Shi Y, Wrackmeyer U, Fischer R, Chen C, Schirdewan A, Jüttner R, Rathjen F, Poller W, Radke MH, and Gotthardt M (2008) The tight junction protein CAR regulates cardiac conduction and cell-cell communication. J Exp Med 205, 2369–2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savon C, Acosta B, Valdes O, Goyenechea A, Gonzalez G, Pinon A, Mas P, Rosario D, Capo V, Kouri V, Martinez PA, Marchena JJ, Gonzalez G, Rodriguez H, and Guzman MG (2008) A myocarditis outbreak with fatal cases associated with adenovirus subgenera C among children from Havana City in 2005. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology 43, 152–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowles NE, Ni J, Kearney DL, Pauschinger M, Schultheiss HP, McCarthy R, Hare J, Bricker JT, Bowles KR, and Towbin JA (2003) Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction. evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 42, 466–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dennert R, Crijns HJ, and Heymans S (2008) Acute viral myocarditis. Eur Heart J 29, 2073–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, and Bergelson JM (2005) Adenovirus receptors. J Virol 79, 12125–12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper LT (2009) Myocarditis. New England Journal of Medicine 360, 1526–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martino TA, Liu P, and Sole MJ (1994) Viral infection and the pathogenesis of dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research 74, 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pankuweit S, and Klingel K (2013) Viral myocarditis: from experimental models to molecular diagnosis in patients. Heart Fail Rev 18, 683–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gauntt CJ, Tracy SM, Chapman N, Wood HJ, Kolbeck PC, Karaganis AG, Winfrey CL, and Cunningham MW (1995) Coxsackievirus-induced chronic myocarditis in murine models. Eur Heart J 16 Suppl O, 56–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kearney MT, Cotton JM, Richardson PJ, and Shah AM (2001) Viral myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: mechanisms, manifestations, and management. Postgraduate Medical Journal 77, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jogler C, Hoffmann D, Theegarten D, Grunwald T, Uberla K, and Wildner O (2006) Replication properties of human adenovirus in vivo and in cultures of primary cells from different animal species. Journal of virology 80, 3549–3558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blair GE, Dixon SC, Griffiths SA, and Zajdel ME (1989) Restricted replication of human adenovirus type 5 in mouse cell lines. Virus Res 14, 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandrasekaran A, Adkins LJ, Seltzer HM, Pant K, Tryban ST, Molloy CT, and Weinberg JB (2019) Age-Dependent Effects of Immunoproteasome Deficiency on Mouse Adenovirus Type 1 Pathogenesis. Journal of Virology 93, e00569–00519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarthy MK, Malitz DH, Molloy CT, Procario MC, Greiner KE, Zhang L, Wang P, Day SM, Powell SR, and Weinberg JB (2016) Interferon-dependent immunoproteasome activity during mouse adenovirus type 1 infection. Virology 498, 57–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarthy MK, Procario MC, Twisselmann N, Wilkinson JE, Archambeau AJ, Michele DE, Day SM, and Weinberg JB (2015) Proinflammatory Effects of Interferon Gamma in Mouse Adenovirus 1 Myocarditis. Journal of Virology 89, 468–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang F, Cheng J, Lam G, Jin DK, Vincent L, Hackett NR, Wang S, Young LM, Hempstead B, Crystal RG, and Rafii S (2005) Adenovirus vector E4 gene regulates connexin 40 and 43 expression in endothelial cells via PKA and PI3K signal pathways. Circ Res 96, 950–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang D, Hawke D, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Meisenhelder J, Nika H, Mills GB, Kobayashi R, Hunter T, and Lu Z (2007) Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by AKT promotes beta-catenin transcriptional activity. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 11221–11229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma A, Marceau C, Hamaguchi R, Burridge Paul W, Rajarajan K, Churko Jared M, Wu H, Sallam Karim I, Matsa E, Sturzu Anthony C, Che Y, Ebert A, Diecke S, Liang P, Red-Horse K, Carette Jan E, Wu Sean M, and Wu Joseph C (2014) Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes as an In Vitro Model for Coxsackievirus B3–Induced Myocarditis and Antiviral Drug Screening Platform. Circulation Research 115, 556–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suomalainen M, Nakano MY, Boucke K, Keller S, and Greber UF (2001) Adenovirus-activated PKA and p38/MAPK pathways boost microtubule-mediated nuclear targeting of virus. The EMBO journal 20, 1310–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yousuf MA, Lee JS, Zhou X, Ramke M, Lee JY, Chodosh J, and Rajaiya J (2016) Protein Kinase C Signaling in Adenoviral Infection. Biochemistry 55, 5938–5946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frese KK, Lee SS, Thomas DL, Latorre IJ, Weiss RS, Glaunsinger BA, and Javier RT (2003) Selective PDZ protein-dependent stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by the adenovirus E4-ORF1 oncoprotein. Oncogene 22, 710–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lampe PD, TenBroek EM, Burt JM, Kurata WE, Johnson RG, and Lau AF (2000) Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J Cell Biol 149, 1503–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Green M, and Loewenstein PM (2006) Human Adenoviruses: Propagation, Purification, Quantification, and Storage. Current Protocols in Microbiology 00, 14C.11.11–14C.11.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bolte S, and Cordelieres FP (2006) A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. Journal of microscopy 224, 213–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Babica P, Sovadinová I, and Upham BL (2016) Scrape Loading/Dye Transfer Assay In Gap Junction Protocols (Vinken M, and Johnstone SR, eds) pp. 133–144, Springer New York, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarnow P, Ho YS, Williams J, and Levine AJ (1982) Adenovirus E1b-58kd tumor antigen and SV40 large tumor antigen are physically associated with the same 54 kd cellular protein in transformed cells. Cell 28, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yew PR, and Berk AJ (1992) Inhibition of p53 transactivation required for transformation by adenovirus early 1B protein. Nature 357, 82–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teodoro JG, and Branton PE (1997) Regulation of p53-dependent apoptosis, transcriptional repression, and cell transformation by phosphorylation of the 55-kilodalton E1B protein of human adenovirus type 5. Journal of Virology 71, 3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Querido E, Blanchette P, Yan Q, Kamura T, Morrison M, Boivin D, Kaelin WG, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, and Branton PE (2001) Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes & development 15, 3104–3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]