Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the social needs of families working with Health Leads at 18 pediatrics practices in 9 US cities and how reported social needs and success addressing them varied according to parents’ preferred healthcare language.

Methods:

We evaluated the social needs of English and Spanish-speakers that received assistance from HL from September 2013 to August 2015. The study sample included 11,661 households in the 4 regions where HL provided support within pediatric primary care practices. We used multivariable regression stratified by region to assess the association between language and successful resource connections.

Results:

Reported social needs differed by language. Spanish speakers most frequently reported needs related to food (food stamps, WIC and food pantries). English speakers most frequently reported child-related needs (childcare vouchers, Head Start and school enrollment). The association between household language and the odds of a successful resource connection varied by region.

Conclusions:

Our findings point out the critical need to address language barriers and other family and community when addressing unmet social needs as part of primary care.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, Latino, Pediatric primary care, Social/Resource needs, Limited English proficiency

INTRODUCTION

Identifying and addressing social needs in primary care has been found to improve health outcomes in children and adults. Families of pediatric patients who were provided with a navigator to help them connect to resources for their self-identified needs reported improvements in their child’s health status and more fulfillment of social needs compared to families provided with information on local resources.1 Addressing unmet social needs in adult primary care was associated with modest improvements in blood pressure and lipid levels.2 Food insecure pregnant women who enrolled in a food program had healthier blood pressure during pregnancy than their peers who were not referred or did not enroll in the food program.2

As promising programs addressing social needs in healthcare settings emerge, it is critical to understand the variation in both programmatic needs and solutions for fulfilling these needs. System changes that do not reflect the varied needs of diverse, vulnerable populations, particularly those who face difficulties accessing and enrolling in available resources, will not result in desired improvements in health outcomes.

Latino children in limited English proficiency (LEP) families are a vulnerable population for whom addressing social needs may mitigate existing health and healthcare disparities.

Latinos are the largest US minority and comprise the majority of the 25 million LEP persons in the US.3,4 Almost one in three Latino children lives below the poverty line.5 31% of families headed by a Latino citizen and 47% of families headed by a Latino non-citizen experience material hardship (crowded housing, food insecurity and/or unmet medical needs).6

Limited English proficiency has been shown to be a barrier to enrollment in public assistance programs, especially for Latinos.7 Latino parents report barriers to enrollment in public assistance programs for their children and their children are less likely to receive such benefits even when eligible.8 In a study of 23,056 WIC participants in Maryland living at/below 100% of the federal poverty level, infants born to Latino mothers were less likely than African American or White infants to receive all benefits for which they were eligible.9 LEP Latino families may be less likely to successfully enroll in public benefits programs in new-emerging destinations due to the lack of social network.10 Anti-immigrant rhetoric and tighter immigration law enforcement have resulted in a “chilling effect”—reduced participation of social welfare programs by eligible immigrant families, including US-born children.11–13

Health Leads© (HL) is one model for identifying and addressing patient social needs in primary care.14 A national non-profit established in 1996, HL partners with hospital systems and clinics to connect patients and families with needed community resources. At the time of this study, Health Leads served patients in eighteen clinics across 13 hospital systems in nine cities.14

In this multi-site, cross-sectional evaluation, we describe the social needs of families seeking assistance from HL at pediatric practices serving low-income families. Next we describe the volume and type of social needs and success rates for the HL program. Finally, we assess the relationship between head of household’s preferred language (English vs. Spanish) and HL’s success in addressing social needs. Previous work has described HL at individual sites, but has not examined patterns of social needs and successes across sites or according to parents’ preferred healthcare language.2

METHODS

Description of the Health Leads Program

At participating pediatric practices, families are screened for social needs as part of routine care using a standardized survey. Clinicians review survey results with families and connect the families to HL advocates as appropriate. Families can also self-refer to HL., When an unmet social need is identified, advocates meet with heads of households and according to the category of need provide them with a rapid resource referral, i.e., information only, or enrollment in the HL program. Social needs are organized into 11 categories as show in Table 1.HL is organized at the household level. For example, a mother seeking assistance with one or more social needs for her 3 children and herself would be captured as one household.

Table 1.

Health Leads universal social needs screener with categories and subcategories added

|

Finding childcare or daycare programs? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Child-Related | |||

| Subcategories: | (Early) Head Start, Childcare & Preschool Program Enrollment, Childcare Voucher/Subsidy, Out-of-School Time Programs, Summer camp, Tutoring | |||

|

Finding safety information or other supplies (childproofing, clothing, diapers)? | Yes | No | |

| Subcategories: | Baby Supplies, Clothing, Holiday Gifts, Household Goods/Furniture, School Supplies | |||

|

Finding food (food pantries)? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Food | |||

| Subcategories: | Food Stamps/SNAP, Pantries & Soup Kitchens, Seasonal Food, WIC | |||

|

Paying utility bills (gas, water, electric, phone)? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Utilities | |||

| Subcategories: | Energy Assistance/Subsidies, Shut Off Protection | |||

|

Finding job resources or job training programs? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Employment | |||

| Subcategories: | Employment 101 (RRR)*, Job Placement Services, Job Training (RRR) | |||

|

Finding housing search resources and emergency shelters? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Housing | |||

| Subcategories: | Emergency Shelter, Housing Assistance Agency, Housing Conditions Complaint, Market Rate Housing (RRR), Public Housing (RRR), Rental Assistance (RRR), Section 8 (RRR), Subsidized (RRR), Transitional & Supportive Housing (RRR) | |||

|

Finding adult education classes (GED, ESL, vocational schools)? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Adult education | |||

| Subcategories: | College (RRR), ESL/ESOL, GED/Basic Education | |||

|

Finding health insurance or healthcare providers? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Health | |||

| Subcategories: | Adult Health Insurance, Adult/Child Access to Primary Care, Adult/Child Dental Care, Adult/Child Fitness and/or Nutrition (RRR), Child Health Insurance, Family Planning (RRR), Home Health, Medical Equipment Prescription Assistance, Adult/Child Access to Specialty Care, Insurance (MCO/PPO/HMO) Navigation | |||

|

Applying for public benefits (TCA, SSI)? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Financial | |||

| Subcategories: | Birth Certificate/ID, Cash Assistance/TANF, Emergency Cash/Grant/Charity, Financial Literacy, SSI/SSDI, Tax Prep, Temporary Disability, Unemployment Benefits (RRR) | |||

|

Finding legal resources? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Legal | |||

| Subcategories: | Benefits Denial, Immigration | |||

|

Finding transportation to clinic appointments? | Yes | No | |

| Category of need: | Transportation | |||

| Subcategories: | Medical Transportation Assistance, Public Transit Assistance | |||

RRR: Rapid Resource Referral, i.e. families were provided with information regarding resources, but were not enrolled in Health Leads for active follow-up.

For households enrolling in the program, advocates collect information necessary to address social needs in an electronic database. The household’s assigned advocate follows up with the head of household via telephone calls or text messages to confirm that the need has been met or to provide additional assistance. Cases are ultimately resolved according to the following 3 categories, 1) successful, benefits received, 2) unsuccessful, need met elsewhere, could not be met or advocate lost contact with family, or 3) equipped, the household reported they could address their need without HL assistance. Advocates make at least 3 attempts to contact a head of household in the 30 days following a request. A case is closed if the advocate does not establish contact with a head of household in this timeframe.

Study Design and Data Source

This is a secondary analysis of de-identified, administrative data collected by HL when they enrolled families in order to address child and family social needs. Only data from HL- enrolled households were analyzed. Rapid resource referrals were excluded because no data were collected as to whether the need was met or not. HL provided data from 8 pediatric practices aggregated by region, Northeast 1, Northeast 2, Mid-Atlantic 1 and Mid-Atlantic 2.All practices serve publicly-insured, low-income patients. Family-level data were limited to preferred healthcare language of the head of household. Age, gender, income and race/ethnicity were frequently missing.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was conducted in two steps. First, social needs were described at the household level in order to understand the volume and types of needs by region, category and language (i.e. the head of household’s preferred language). For descriptive analyses, needs were treated as “ever-needs” (e.g. did the household ever need assistance related to food?). Student’s t-tests and two sample tests of proportions were used to compare differences in numbers and types of needs by language.

Second, outcomes of HL services were presented using event-level data on individual social needs (i.e. a single category of social need reported by a household at a single point in time). We conducted multivariable logistic regression to model the odds of successful resource connection according to type of social need and preferred language of the head of household, separately by region. Because a household could be represented multiple times, i.e. once per social need, robust Huber-White sandwich estimators of variance were used to account for the non-independence of observations.15

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

RESULTS

11,661 households in the 4 regions of study were referred to HL to address social needs from September 2013 to August 2015. Of these, 745 (6.4%) were dropped from analyses because the preferred language was either missing (1.1%, n=132) or not English or Spanish (5.3%, n=613). Data for 10,916 English or Spanish-speaking households were analyzed. Spanish-speaking households comprised 22.7% (n=2,481) of the sample. Household characteristics could not be meaningfully characterized, as demographic data (e.g. age, gender and race of heads of households) were frequently missing.

Northeast 1 had the most total households, n=4,481, while Mid-Atlantic 1 had the fewest, n=1,563 (Table 2). Mid-Atlantic 1 had the highest percentage of Spanish-speaking households (48.4%, n=756), while Mid-Atlantic 2 had the lowest (8.3%, n=239).

Table 2.

Study sample of Health Leads households (N=10,916) from September 1, 2013 to August 31, 2015 in 4 geographic regions according to the head of household’s preferred language.

| Preferred Healthcare Language | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Number of Householdsn (column %) | Spanish n (column %, row %) | English n (column %, row %) |

| Northeast 1 | 4,481 (41.1%) | 802 (27.6%, 15.3%) | 3,797 (45.0%, 84.7%) |

| Northeast 2 | 2,007 (18.4%) | 684 (32.3%, 40.0%) | 1,205 (14.3%, 60.0%) |

| Mid-Atlantic 1 | 1,563 (14.3%) | 756 (30.5%, 48.4%) | 807 (9.6%, 51.6%) |

| Mid-Atlantic 2 | 2,865 (26.3%) | 239 (9.6%, 8.3%) | 2,626 (31.1%, 91.7%) |

| Total | 10,916 | 2,481 (100%, 22.7%) | 8,435 (100%, 77.3%) |

Social needs according to the head of household’s preferred language are provided in Table 3. Spanish-speakers reported food-related needs more than anything else, with 35.7% of Spanish-speaking households ever needing food related resources. The most common social need among English speakers was child-related resources, with 38.5% ever reporting need. English speakers were significantly more likely than Spanish speakers to ever report needs related to utilities (28.1%, 16.2% respectively), employment (25.8%, 10.5%, respectively) and housing (24.6%, 11.4%, respectively). In contrast, Spanish speakers were significantly more likely than English speakers to ever report needs related to health (28.6%, 11.4%, respectively) and adult education (24.8%, 13.4%, respectively). Financial issues, legal problems and transportation were the least frequent social needs reported for both English and Spanish speakers.

Table 3.

Social needs of Health Leads households (N = 10,916) from September 1, 2013 to August 31, 2015 in 4 geographic regions according to the head of household’s preferred language

| Preferred Healthcare Language | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N=10,916 | Spanish n=2,481 | English n=8,435 | p-value | |

| # Social needs per household (mean (SD)) | 3.2 (2.7) | 2.8 (2.3) | 3.2 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Social Needs Categories (n (%) ever reporting a need in this category) | ||||

| Child-Related | 4,034 (37.0%) | 783 (31.6%) | 3,251 (38.5%) | <0.001 |

| Commodities | 3,368 (30.8%) | 670 (27.0%) | 2,698 (32.0%) | <0.001 |

| Food | 3,260 (29.9%) | 885 (35.7%) | 2,375 (28.2%) | <0.001 |

| Utilities | 2,776 (25.4%) | 403 (16.2%) | 2,373 (28.1%) | <0.001 |

| Employment | 2,433 (22.3%) | 261 (10.5%) | 2,172 (25.8%) | <0.001 |

| Housing | 2,357 (21.6%) | 283(11.4%) | 2,074 (24.6%) | <0.001 |

| Adult Education | 1,746 (16.0%) | 615 (24.8%) | 1,131 (13.4%) | <0.001 |

| Health | 1,671 (15.3%) | 709 (28.6%) | 962 (11.4%) | <0.001 |

| Financial | 923 (8.5%) | 236 (9.5%) | 687 (8.1%) | 0.031 |

| Legal | 662 (6.1%) | 121 (4.8%) | 541 (6.4%) | 0.005 |

| Transportation | 282 (2.6%) | 28 (1.1%) | 254 (3.0%) | <0.001 |

Italics indicate that % Spanish > % English

Households could request assistance with multiple social needs for multiple household members and/or on multiple occasions. As a result of routine screening, 10,916 households reported 32,731 unmet social needs (mean per household=3.2, SD=2.7). 4,481 households in Northeast 1 had 14,028 social needs (mean per household=3.2, SD=2.7). 2,007 households in Northeast 2 had 4,213 social needs (mean per household=2.3, SD=1.6). 1,563 households in Mid-Atlantic 1 had 4,258 social needs (mean per household=2.9, SD=2.8). 2,865 households in Mid-Atlantic 2 had 10,220 social needs (mean per household=3.8, SD=3.1). Both overall volume of household-reported social needs and social needs by language preference varied by geographic region (Table 2).

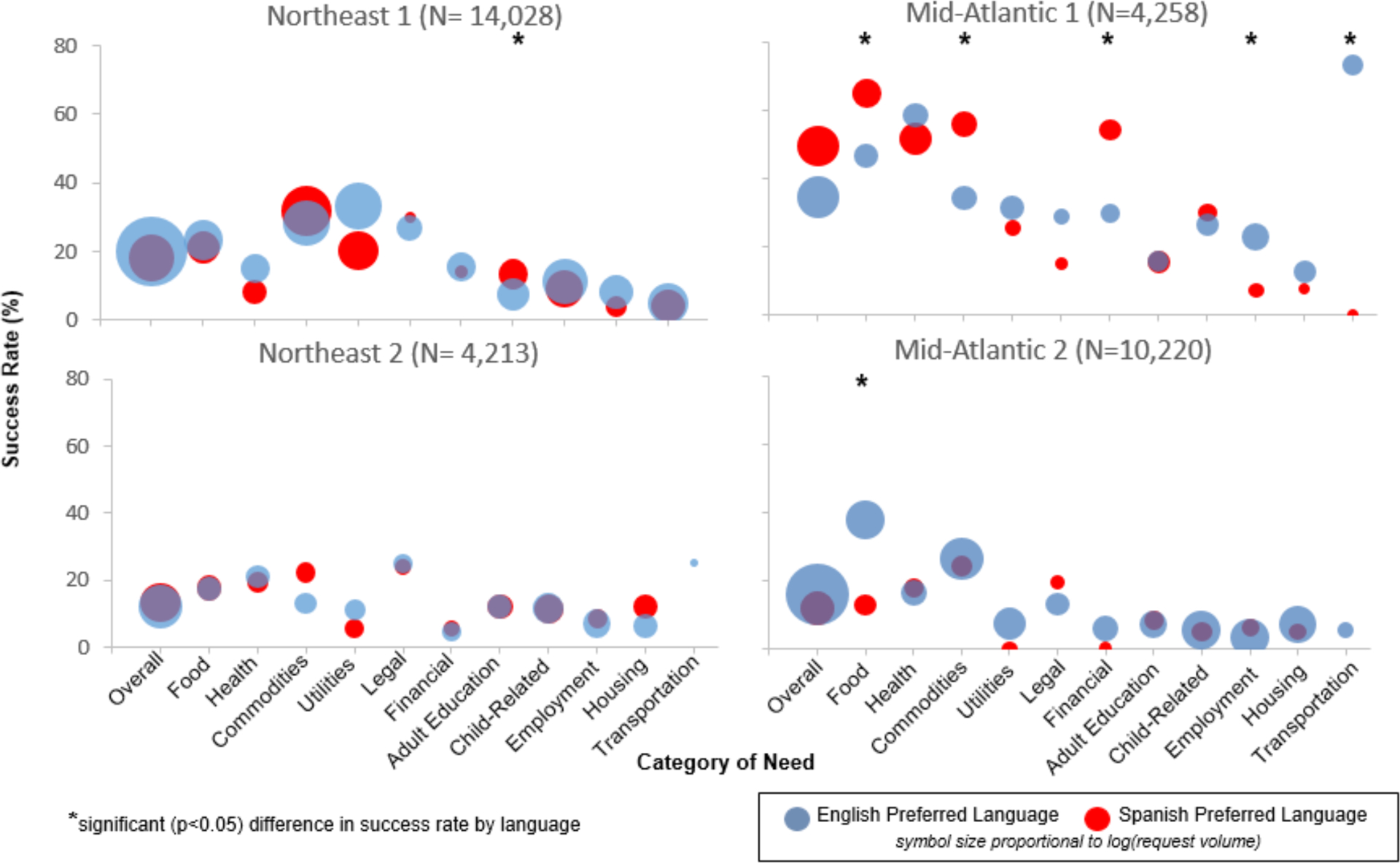

Successful resource connection rates varied according to type of social need, service region and head of household’s preferred language (Figure 1). Program-wide, transportation, food, health and commodities-related social needs had the highest rates of successful resource connections, with 53.2, 33.4, 32.5 and 29.0% success, respectively. Whereas food, health and commodities had high volumes of reported needs (4474, 2131 and 5727, respectively), only 312 transportation needs were reported program-wide during the study period. Housing and employment had low success rates program-wide (6.3% and 7.8%, respectively), despite high volumes of reported needs (3547 and 3134, respectively). Mid-Atlantic 1 demonstrated the highest overall rates of successful resource connection at 41.9%, compared to rates of 19.8%, 12.6% and 15.8% Northeast 1 Northeast 2 and Mid-Atlantic 2, respectively. Success rates were higher overall for Spanish-speakers, with 25.6% vs. 19.1% success in English-speakers. Rates of successful resource connection were significantly (p<0.05) greater in Spanish- vs. English-speaking households among those with adult education needs in Northeast 1 and those with food, commodities and financial needs in Mid-Atlantic 1. Conversely, rates of successful resource connection were significantly greater in English-speaking households among those with employment and transportation needs in Mid-Atlantic 1 and food needs in Mid-Atlantic 2.

Figure 1.

Success rate for social needs by region and category of need

In the multivariable logistic regression, data from Northeast 1 and Northeast 2 were combined given that Spanish language had a weak negative association with the odds of a successful resource connection (odds ratio 0.86; 95% confidence interval0.75–0.98) (Table 4). In contrast, Spanish language increased the odds of a successful resource connection in Mid- Atlantic 1 (odds ratio 1.28; 95% confidence interval1.01–1.62), but significantly decreased the odds of success in Mid-Atlantic 2 (odds ratio 0.63; 95% confidence interval0.43–0.92). English language preference served as the reference category. The odds of a successful resource connection also varied by region and by type of social need.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds* of a successful resource connection according to head of household’s preferred language and category of need.

| Northeast (n=18,253) | Mid-Atlantic 1 (n=4,258) | Mid-Atlantic 2 (n=10,220) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | P-value | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Spanish Language Preference | 0.86 | 0.75, 0.98 | 0.023 | 1.28 | 1.01, 1.62 | 0.038 | 0.63 | 0.43, 0.92 | 0.017 |

| Social Need Categories | |||||||||

| Food | 2.19 | 1.87, 2.57 | <0.001 | 3.53 | 2.18, 5.72 | <0.001 | 9.38 | 7.15, 12.32 | <0.001 |

| Health | 1.59 | 1.27, 2.01 | <0.001 | 2.78 | 1.75, 4.43 | <0.001 | 3.65 | 2.50, 5.32 | <0.001 |

| Commodities | 3.12 | 2.71, 3.57 | <0.001 | 2.08 | 1.29, 3.35 | 0.003 | 5.96 | 4.56, 7.80 | <0.001 |

| Utilities | 3.39 | 2.94, 3.92 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 0.68, 2.24 | 0.490 | 1.27 | 0.86, 1.86 | 0.230 |

| Legal | 2.83 | 2.21, 3.65 | <0.001 | 0.91 | 0.43, 1.96 | 0.817 | 2.81 | 1.78, 4.44 | <0.001 |

| Financial | 1.13 | 0.86, 1.50 | 0.377 | 2.04 | 1.18, 3.53 | 0.011 | 1.01 | 0.59, 1.74 | 0.969 |

| Adult education | 0.93 | 0.76, 1.16 | 0.534 | 0.46 | 0.26, 0.82 | 0.008 | 1.38 | 0.90, 2.10 | 0.138 |

| Child-Related | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — | Ref | — | — |

| Employment | 0.64 | 0.50, 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.43, 1.34 | 0.335 | 0.63 | 0.43, 0.91 | 0.014 |

| Housing | 0.42 | 0.33, 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.40 | 0.19. 0.84 | 0.015 | 1.29 | 0.93, 1.78 | 0.123 |

| Transportation | 7.71 | 4.40, 13.50 | <0.001 | 5.90 | 3.27, 10.65 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.22, 4.09 | 0.956 |

Adjusted odds were calculated using multivariable regression. Event-level data on individual social needs (N = 32,731) from September 1, 2013 - August 31, 2015. For category definitions see Table 1.

DISCUSSION

HL advocates assisted families of pediatric patients with a broad range of social needs and we analyzed HL’s success in connecting families to needed resources. In this sample, Spanish speakers most frequently reported needs related to food (food stamps, WIC and food pantries). English speakers most frequently reported child-related needs (childcare vouchers, Head Start and school enrollment). Both Spanish and English speakers less frequently reported needing assistance with financial issues, legal problems and transportation compared to other social needs. The odds of a successful resource connection were significantly higher for Spanish-speakers compared to English-speakers in Mid-Atlantic 1 regardless of type of social need. Spanish-speakers in regions other than Mid-Atlantic 1, however, had significantly lower odds of successful resource connection compared to English speakers.

As our findings support, social needs as well as the likelihood of success in addressing them vary by patient and community characteristics. We need more information regarding addressing social needs for LEP Latinos who are especially likely to live in poverty and to not receive public benefits for which they or their children are eligible. Data for our study were collected prior to the current political debate regarding the Public Charge, which has further suppressed participation in public benefits programs (Baltimore Sun).13,16 Tailoring programs to the cultural and linguistic needs of patients as well the community context requires upfront investment, but may increase effectiveness. We must ensure that this process is designed and functions in practice as a means of addressing a patient need and not simply of fulfilling an obligation on the part of the health care provider or system.

A better understanding of successes and failures in addressing social needs can guide development of effective programs. Evaluation of social needs screening and referral programs to date has focused primarily on the number of people served. Successful resource connections made and the impact on the health of the child and/or family well being requires further study. Our findings demonstrate that there is much to be gained in studying success or failure with resource connections. We found key differences across regions in both social needs and success of resource connection. The current data do not allow for exploration of site-specific implementation strategies and contextual factors that may have contributed to our findings. Our finding of regional variation supports the need for evaluation work across programs at different sites to identify common and distinct program implementation factors associated with effective programs. There is a considerable gap in knowledge about implementation factors of programs and how they may be related to successful resource connections and ultimately improved health.

Though comparative work across sites is limited, prior research provides some insight into contextual tailoring and its potential impact on effectiveness of social needs screening and referral programs. Marpagda et al. compared receipt of food resources for food insecure patients attending a diabetes clinic via personal assistance versus provision of information only.17 Patients receiving personal assistance were more likely to have their need met than patients who received information only.17 In follow-up interviews, patients reported that fear of immigration or legal repercussions prevented them from accessing community resources to address food insecurity, specifically that they lacked formal documentation of income or that use of public benefits would jeopardize them in the naturalization process.17 Another issue is the discrepancy between unmet social needs and interest in connection to resources. As part of pediatric primary care visits, Bottino et al screened for food insecurity as well as offered a menu of referrals to food resources.18 Among the 340 adult caregivers, there was only partial overlap between reporting food insecurity (31.2%) and requesting assistance connecting to a food resource (31.5%).18 While 16.8% of caregivers reported food insecurity and requested resource connection, 14.4% reported food insecurity, but did not request food resources and 14.7% did not report food insecurity, but did request food resources.18

Several limitations of the study deserve mention. Analyses did not control for differences in the head of household’s age, gender, income or race/ethnicity due to high rates of missing information in this patient-reported data. We could not reasonably correct the level of missingness with imputation methods or exclusion of individuals with missing data. As such, we could not make inferences about the effectiveness of HL programming among subgroups. Furthermore, data regarding social needs were available only in broad categories, potentially masking patterns of need and success within categories. For example, the category of health includes both adult health insurance and child health insurance needs, though specific needs related to enrolling and maintaining child health insurance may vary according to demographic characteristics.19 Our findings also may reflect in part either clinical practice differences or HL practice differences according to site. The analysis assumes equal quality across sites. Self-reported social needs may not reflect true needs. HL clients may censor their requests according to their awareness of public programs.

These limitations notwithstanding our findings demonstrate that within one national social needs screening and resource connection program unmet social needs are highly prevalent. In addition, social needs and whether these needs were met varied by region and by caregiver language status, which has direct implications for how programs are developed and implemented. Social needs screening and resource connection/referral programs continue to increase, but, as Gottlieb highlighted in a systematic review of social needs interventions, there is a need for higher-quality studies that move beyond process outcomes.20 There are many questions that these data cannot answer but our findings do support the critical need for the development of patient-centered programs to be complemented by rigorous studies of effectiveness. Subsequently, implementation researchers will need to answer questions of feasibility, sustainability and dissemination of successful programs. The ultimate question is whether screening and addressing social needs as part of healthcare improves health or healthcare outcomes, but there are many questions to answer first.21

What’s New:

Our findings call attention to the opportunity to address social needs in pediatric primary care and that programs designed to meet such needs must account for linguistic and contextual factors.

Funding:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, Laves E, Burns AR, Amaya A, Sweeney P, Schudel C, Adler NE. Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(11):e162521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, Reznor G, Atlas SJ. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):244–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Census Bureau. 2010. Census Briefs: The Hispanic Population 2010. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.. Published May 2011 Accessed 8 November 2018.

- 4.US Census Bureau. Language Spoken at Home: 2010 American Community Survey 1- Year Estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed 8 November 2018.

- 5.Proctor BD, Semega JL, Kollar MA. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherman A African American and Latino Families Face High Rates of Hardship. https://www.cbpp.org/research/african-american-and-latino-families-face-high-rates-of-hardship. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2006. Accessed 8 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeCamp LR, Bundy DG. Generational status, health insurance, and public benefit participation among low-income Latino children. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:735–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feinberg E, Swartz K, Zaslavsky AM, Gardner J, Walker DK. Language proficiency and the enrollment of Medicaid-eligible children in publicly funded health insurance programs. Matern Child Health J. 2002;6(1):5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert D, Nanda J, Paige D. Securing the Safety Net: Concurrent Participation in Income Eligible Assistance Programs. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):604–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeCamp LR, Polk S, Chrismer MC, Giusti F, Thompson DA, Sibinga E. Health Care Engagement of Limited English Proficient Latino Families: Lessons Learned from Advisory Board Development. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(4):521–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ku L, Matani S. Left Out: Immigrants’ Access To Health Care And Insurance. Health Aff (Milwood). 2001;20(1):247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hirsch JS. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkataramani M, Pollack CE, DeCamp LR, Leifheit KM, Berger ZD, Venkataramani AS. Association of maternal eligibility for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program with citizen children’s participation in the Women, Infants, and Children program. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(7):699–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leads Health. https://healthleadsusa.org. Published 2018. Accessed 8 November 2018.

- 15.StataCorp. 20.21 Obtaining Robust Variance Estimates In: Stata 15 Base Reference Manual. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richman R Baltimore school with large immigrant population loses vital funding source. The Baltimore Sun. May 6, 2019. https://www.baltimoresun.com/education/bs-md-ci-john-ruhrah-poverty-20190423-story.html?. Accessed December 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marpadga S, Fernandez A, Leung J, Tang A, Seligman H, Murphy EJ. Challenges and successes with food resource referrals for food-insecure patients with diabetes. Perm J. 2019;23:18–097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottino CJ, Rhodes ET, Kreatsoulas C, Cox JE, Fleegler EW. Food insecurity screening in pediatric primary care: Can offering referrals help identify families in need? Acad Peds. 2017;17(5):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BeLue R, Miranda PY, Elewonibi BR, Hillemeier MM. The association of generation status and health insurance among US children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler N. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am JPrev Med. 2017;53(5):719–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb L, Cottrell EK, Park B, Clark KD, Gold R, Fichtenberg C. Advancing social prescribing with implementation science. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018. May-Jun;31(3):315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]