Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains one of the most challenging malignancies. Desmoplasia and tumor-supporting inflammation are hallmarks of PDAC. The tumor microenvironment contributes significantly to tumor progression and spread. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) facilitate therapy resistance and metastasis. Recent reports emphasized the concurrence of multiple subtypes of CAFs with diverse roles, fibrogenic, and secretory. CXCR2 is a chemokine receptor known for its role during inflammation and its adverse role in PDAC. Oncogenic Kras upregulates CXCR2 and its ligands and, thus, contribute to tumor proliferation and immunosuppression. CXCR2 deletion in a PDAC syngeneic mouse model produced increased fibrosis revealing a potential undescribed role of CXCR2 in CAFs. In this study, we demonstrate that the oncogenic Kras-CXCR2 axis regulates CAFs function in PDAC and contributes to CAFs heterogeneity. We observed that oncogenic Kras and CXCR2 signaling alter CAFs, producing a secretory CAF phenotype with low fibrogenic features; and increased secretion of pro-tumor cytokines and CXCR2 ligands, utilizing NF-κB activity. Finally, using syngeneic mouse models, we demonstrate that oncogenic Kras is associated with secretory CAFs and that CXCR2 inhibition promotes activation of fibrotic cells (myofibroblasts) and impact tumors in a mutation-dependent manner.

Keywords: CAFs, CXCR2, oncogenic Kras, chemokines, paracrine factors, immunosuppression, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, inflammation, desmoplasia

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest human diseases, is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA [1]. The lack of both early detection tools and viable treatment options made pancreatic cancer one of the deadliest human malignancies [2]. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common and most aggressive subtype of pancreatic cancers [3, 4]. PDAC develops progressively as a result of accumulating genetic and epigenetic alterations [5]. Oncogenic Kras mutation occurs very early before the inception of the full-blown disease. Premalignant lesions with the Kras mutation progresses to PDAC with inactivation of tumor suppressors p53 and Smad4 [6]. Kras mutation is tightly linked to inflammatory signals that contribute to tumor growth and immunosuppression, thus enabling disease progression [7].

One of the major inflammatory signals in PDAC is CXCR2, which also has close ties to oncogenic Kras [8]. Our group has previously demonstrated that CXCR2 signaling plays a direct role in KRAS-induced autonomous cell growth by contributing to its intracellular signaling during PDAC development, tumor growth, and progression. This suggests that targeting CXCR2 signaling might be a feasible approach to inhibit KRASG12D induced PDAC tumor cell growth.

CXCR2 is the receptor for a group of C-X-C chemokines, including CXCL1–3 and CXCL5–8. CXCR2 signaling helps in recruiting granulocytes to the site of inflammation and also enable angiogenesis [9, 10]. CXCR2 ligands expression leads to the recruitment of immunosuppressive neutrophils and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [11, 12] and enhancing angiogenesis [13, 14]. Furthermore, CXCR2 signaling can directly contribute to tumor growth by promoting malignant cell proliferation and migration [8, 13]. Nonetheless, syngeneic implantation of cells derived from Pdx1-Cre; KrasG12D (KC) mouse into a CXCR2 knockout (Cxcr2−/−) model played both anti-tumor and pro-tumor roles. CXCR2 deletion suppressed angiogenesis, inducing an anti-tumor immune response, but additional, increased the induction of fibrosis and increased metastasis, revealing a potential role in the fibrotic compartment of PDAC [15].

PDAC is characterized by a dense and complex desmoplastic microenvironment composed of extracellular matrix (ECM), fibrotic cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells [16, 17]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) represent a significant component of the PDAC tumor microenvironment [16, 17]. CAFs are fibrotic cells of multiple origins, including pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), resident fibroblasts, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, fibrocytes, and others [18]. In response to external cues, quiescent fibrotic cells get activated, and when this activation occurs in the context of cancer, they become CAFs [19–21]. CAFs have been associated with supporting tumors in all the stages, from initiation to spread [19–21]. Myofibroblasts activated fibrotic cells with extensive ECM synthesis, have been used for long as a synonym for CAFs in the context of cancer [19–21]. Recent reports indicate the coexistence of multiple functional subsets of CAFs [22, 23]. The typical myofibroblasts are characterized by the upregulation of α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and ECM molecules such as collagen I [19–21]. The other subset, referred to as inflammatory or secretory CAFs, develops through paracrine signaling and tends to have low expression of αSMA and high expression of inflammatory mediators [22]. This functional heterogeneity could explain the versatility of CAFs and the failure of targeting desmoplasia to resolve PDAC [24, 25].

Taken together, our data demonstrate that CXCR2 signaling in the CAFs inhibits the myofibroblast phenotype and induces a phenotype with a secretory function. In the present study, we demonstrate that oncogenic Kras and CXCR2 signaling interaction in CAFs causes them to assume a phenotype that is characterized by lower expression of αSMA and ECM proteins, and higher expression of pro-tumorigenic secreted factors including immunosuppressive cytokines and tumor-supporting chemokines. We demonstrate that this phenotype is mediated through activating NF-κB transcription factor activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions

PDAC murine cells Panc02 cells and UN-KC-6141 cell line (referred to in this study as KC) [26]; and the immortalized mouse pancreatic stellate cells isolated from a healthy mouse pancreas (ImPSC) [27], was a kind gift from Dr. Raul Urrutia, Mayo Clinics. Panc02 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium (RPMI) (HyClone®, GE Life Sciences, UT). KC, along with ImPSC, were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (HyClone®, Thermo Scientific, UT). These media were supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, GA), L-glutamine (MediaTech, VA), vitamin solution (MediaTech), and gentamycin (Gibco, Life Technologies, NY).

Immortalized human CAF cell line (10–32 PC Puro) was derived from pancreatic tumor tissues. The pancreatic tumor was minced, fibroblasts were isolated by differential trypsinization and subsequently immortalized using hTERT. It was maintained in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS, L-Glutamine, vitamin solution, and Gentamycin. HPNE and HPNE-Kras: Immortalized human pancreatic duct-derived cell lines that express exogenous KRAS(G12D) (HPNE-Kras) or normally express wildtype Kras (HPNE) [28] were maintained in media consisted of three parts DMEM (HyClone®, Thermo Scientific, UT) and one part in M3:5 growth medium (INCELL, San Antonio, TX) supplemented with 5% FBS, L-glutamine, vitamin solution and gentamycin.

The previously described human PDAC cell lines derived from CD18/HPAF cell lines that were either transfected with KRAS(G12D) knockdown vector (CD18/HPAF-Kras KD) or control vector (CD18/HPAF-scram) [29] were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, L-Glutamine, vitamin solution, and Gentamycin. BxPC3 control and BxPC3-KRAS cells were a kind gift from Dr. Michel Ouellette University of Nebraska Medical Center. Both the cell lines were maintained in RPMI media supplemented with 5% FBS, L-glutamine, vitamin solution, gentamycin, and hygromycin B 200 μg/mL (Corning™, USA).

Generation of conditioned media

Cells were cultured in their respective complete media till the cell confluence reached 70%. Media was removed, cells washed with Hanks’s balanced salt solution (HBSS, Cellgro, Herndon, VA), and the media was changed to serum-free media for 72h. Both the conditioned media and the serum-free media (control conditioned media) contained the antibiotics in which cells were maintained. Conditioned media were normalized to the cell numbers from which the media were derived.

Co-culture using conditioned media and treatment with exogenous chemokines and inhibitor

Cells were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells/well using six-well plates and maintained in complete media for 24h. Complete media was replaced with serum-free media, diluted conditioned media, or different treatment and incubated for the various time points. The cells were treated for 24h for RNA analysis and 72h for protein and MTT analysis.

Reagents and antibodies

CXCR2 inhibitors SCH-479833 and SCH-527123, obtained from Schering-Plough Research Institute, and prepared by dissolving in 20% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD; Acros Chemical St. Louis, MO). Exogenous human CXCL8 and exogenous murine CXCL1 were obtained from (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Animal model and details of in-vivo studies

Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. All procedures performed were in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). We utilized two syngeneic immunocompetent mouse models to study the effect of Kras mutation and stromal CXCR2 signaling on tumor growth and metastasis. Two different murine PC cell lines, Panc02-GLUC-GFP (wildtype Kras) [30] and KRAS-PDAC-GFP (oncogenic Kras) [8], were implanted orthotopically in the pancreas of 6–8 weeks old Cxcr2+/+ (wildtype) and Cxcr2−/− (knockout) mice. Mice were sacrificed after 4–6 weeks, as previously described [15]. For orthotopic injection of Panc02-GLUC-GFP, we utilized five mice each in Cxcr2+/+ and Cxcr2−/− mice, whereas, for orthotopic injection of KRAS-PDAC-GFP, we utilized nine mice each in Cxcr2+/+ and eight mice in Cxcr2−/− mice. A part of the tumor was fixed in 10% formalin and processed for histological analysis.

mRNA expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the standard Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) protocol following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse Transcription was performed with 1μg RNA using iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix for qRT-PCR (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Regular PCR reactions were performed using Fast Start Taq dNTPack (Roche Diagnostics, IN, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) using the CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD). Primer sets used for the study are listed in Table 1. For regular PCR, amplified cDNA was resolved on EtBr containing 2% agarose gels. For real-time PCR mean Ct values of the target genes were normalized to mean Ct values of one or more the housekeeping control genes (Ribosomal protein large 13 A (RPL13A), β Actin, Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A (PPIA) and Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1)) [-ΔCt = Ct (housekeeping gene) – Ct (target gene)]. The ratio of mRNA expression of target genes versus the housekeeping gene was defined as 2(-ΔCt). Melting curve analysis was performed to check the specificity of the amplified product.

Table 1:

List of primers

| Gene | Temp. (°C) | Species | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cxcl1 | 55° | Murine | Forward 5’-TCGCTTCTCTGTGCAGCGCT-3’ Reverse 5’- GTGGTTGACACTTAGTGGTCT C-3’ |

| Cxcl2 | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-AGTGAACTGCGCTGTCAATG-3’ Reverse 5’-TTCAGGGTCAAGGCAAACTT-3’ |

| Cxcl3 | 68° | Murine | Forward 5’-GCAAGTCCAGCTGAGCCGGGA-3’ Reverse 5’-GACACCGTTGGGATGGATCGCTTT-3’ |

| Cxcl5 | 68° | Murine | Forward 5’-ATGGCGCCGCTGGCATTTCT-3’ Reverse 5’-CGCAGCTCCGTTGCGGCTAT-3’ |

| Cxcl7 | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-CTCAGACCTTACATCGTCCTGC-3’ Reverse 5’-AGCGCAACAAGGATCGTCCTGC-3’ |

| IL1 | 56° | Murine | Forward 5’-GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT-3’ Reverse 5’-ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT-3’ |

| IL4 | 56° | Murine | Forward 5’-GGTCTCAACCCCCAGCTAGT-3’ Reverse 5’-GCCGATGATCTCTCTCAAGTGAT-3’ |

| IL6 | 55° | Murine | Forward 5’-CCTCTGGTCTTCTGGAGTACC-3’ Reverse 5’-ACTCCTTCTGTGACTCCAGC-3’ |

| IL10 | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-GCTCTTACTGACTGGCATGAG-3’ Reverse 5’-CGCAGCTCTAGGAGCATGTG-3’ |

| IL12 | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-TGGGTTTGCCATCGTTTTGCTG-3’ Reverse 5’-ACAGGTGAGGTTCACTGTTTCT-3’ |

| IL13 | 55° | Murine | Forward 5’-CCTGGCTCTTGCTTGCCTT-3’ Reverse 5’-GGTCTTGTGTGATGTTGCTCA-3’ |

| IL17 | 55° | Murine | Forward 5’-TTTAACTCCCTTGGCGCAAAA-3’ Reverse 5’-CTTTCCCTCCGCATTGACAC-3’ |

| IFN-γ | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-ATGAACGCTACACACTGCATC-3’ Reverse 5’-CCATCCTTTTGCCAGTTCCTC-3’ |

| TNF-α | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-CCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT-3’ Reverse 5’-GCTACGACGTGGGCTACAG-3’ |

| Rpl13a | 58° | Murine | Forward 5’-ACTCTGGAGGAGAAACGGAAGG-3’ Reverse 5’-CAGGCATGAGGCAAACAGTC-3’ |

| Actin β | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3’ Reverse 5’-CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3’ |

| PPIA | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-TGTGCCAGGGTGGTGACTTT-3’ Reverse 5’-CGTTTGTGTTTGGTCCAGCAT-3’ |

| HPRT | 57° | Murine | Forward 5’-CCTAAGATGAGCGCAAGTTGAA –3’ Reverse 5’-CCACAGGACTAGAACACCTGCTAA-3’ |

| Acta2 (αSMA) | 56° | Murine | Forward 5’-CCCAGACATCAGGGAGTAATGG-3’ Reverse 5’-TCTATCGGATACTTCAGCGTCA-3’ |

| COL1A1 (Collagen I) | 56° | Murine | Forward 5’-GCCCGAACCCCAAGGAAAAGAAGC-3’ Reverse 5’-CTGGGAGGCCTCGGTGGACATTAG-3’ |

| COL4A1 (Collagen IV) | 55° | Murine | Forward 5’-TCCGGGAGAGATTGGTTTCC-3’ Reverse 5’-CTGGCCTATAAGCCCTGGT-3’ |

| IFN-γ | 60° | Human | Forward 5’-GCATCGTTTTGGGTTCTCTTGGCTCTTACTGC-3’ Reverse 5’ CTCCTTTTTCGCTTCCCTGTTTTAGCTGCTGG-3’ |

| IL17 | 56° | Human | Forward 5’-AGATTACTACAACCGATCCACCT-3’ Reverse 5’ GGGGACAGAGTTCATGTGGTA-3’ |

| TNF-α | 60° | Human | Forward 5’-GAG CTG AGA GAT AAC CAG CTG GTG-3’ Reverse 5’ CAG ATA GAT GGG CTC ATA CCA GGG-3’ |

| CXCL7 | 57° | Human | Forward 5’-ACTTGTAGGCAGCAACTCACC-3’ Reverse 5’ GGTGGAGAAGGCTGAGCTAG-3’ |

Western blot analysis

The total protein was isolated by lysing cells with RIPA buffer, and the protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein samples (40 μg) were electrophoresed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels and transferred to the Immobilon-p Transfer membrane (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). Membranes were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were probed with respective specific primary antibodies [αSMA (Thermofisher; 1:500) and HSP70 (Santacruz; 1:250)] overnight at 4˚C. Membranes were washed with tween 20 tris-buffered saline (TTBS) buffer three times and probed with respective secondary antibodies. Following washing with TTBS buffer membranes were visualized using Luminata Forte Western HRP Substrate Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA). We utilized NIH Image J Software for quantification of the intensity of the bands of our protein of interest and their respective loading control. We also normalized the bands to the Control cells used in the study.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Cells were seeded at 1×105 density in a six-well plate then treated with various treatment for the different time points. The supernatants of cultured cells were collected for ELISA. ELISA assays for mCXCL1, mCXCL2, mCXCL5, mCXCL7, and hCXCL8 were performed using a Duoset kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using Bio-Tek plate reader (Winooski, VT).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured on four-well chamber slides and treated according to their respective experiments. After ceasing the treatment, cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, then again washed with PBS for three times. Cells then blocked with antibody diluent (BD Biosciences) or blocking buffer (PBS with 3% BSA and 0.1% Saponin) for cytoplasmic targets. Cells were probed with the respective antibody (CXCR2 ( a gift from Dr. Strieter; 1:1000), αSMA (Thermofisher; 1:250), CD10 (Abcam; 1:50) and p50 (Biolegend; 1:100)) at 4˚C overnight. The next day, slides were stained with the respective antibody and counterstained with the nucleic staining 4, 6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Finally, slides were mounted with Vectashield® mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and observed under a fluorescent microscope.

NFkB p65 Transcription Factor Assay

CAF cells 10–32 PC Puro were plated at a density of 2×106 on a 100 mm dish in complete media. The following day cells were washed with HBSS and treated with HPNE and HPNE-KRAS cell condition media, or serum-free media, media containing 10 ng/mL CXCL8 and 10 ng/mL CXCL8 with 50 μg/mL of CXCR2 SCH-527123 for two hours. Cells were lysed to obtain nuclear fraction as described in the nuclear extraction kit (NBP2–29447, Novus Biologicals, CO, USA). A part of the obtained nuclear fraction protein was quantified using the BCA kit (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit). Furthermore, the nuclear fraction was utilized to perform NFκB p65 transcription factor assay as per the protocol given by the NFκB p65 transcription factor assay kit (ab133112, Abcam, MA, USA). The results were normalized to the amount of protein quantified.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Sections of 4μm thick from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized with xylene and dehydrated by incubating with decreasing ethanol concentrations. Antigen retrieval was performed using sodium citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) and microwave for 10 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubating with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 minutes. After blocking non-specific binding by incubating with serum, slides were probed with primary antibody (αSMA (Thermofisher; 1:250) and CD10 (Abcam; 1:50)) overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed, and the appropriate secondary antibodies were added. Immunoreactivity was detected using the ABC Elite Kit and 3, 3 diaminobenzidine substrate kit (DAB) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). A reddish-brown precipitate indicated positive staining. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin.

In vitro cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded at appropriate densities in 96-well plates and were allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were washed with HBSS and were incubated with serum-free media alone or with other treatments (conditioned media, CXCR2 inhibitors, exogenous CXCR2 ligands) for 72 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay, as previously described [31]. Briefly, 50 μl of the MTT reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) was added to each well and incubated for 2–4h. Media and MTT were removed and replaced by 100 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Percent inhibition of cell growth was calculated by the formula: [100 - (A/B) x 100], where ‘A’ and ‘B’ are the absorbance of the treated and Control group, respectively. The percentage of cell growth was calculated by the formula: [(A/B) x 100], where ‘A’ and ‘B’ are the absorbance of the treatment and control group, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad) software. The statistical method and sample size (n; the number of replicates) are indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Error bars on figures show standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-tailed Student’s t-test, ANOVA, and Posthoc comparisons using Mann-Whitney tests with a Bonferroni adjustment were performed when appropriate, as indicated in figure legends.

RESULTS

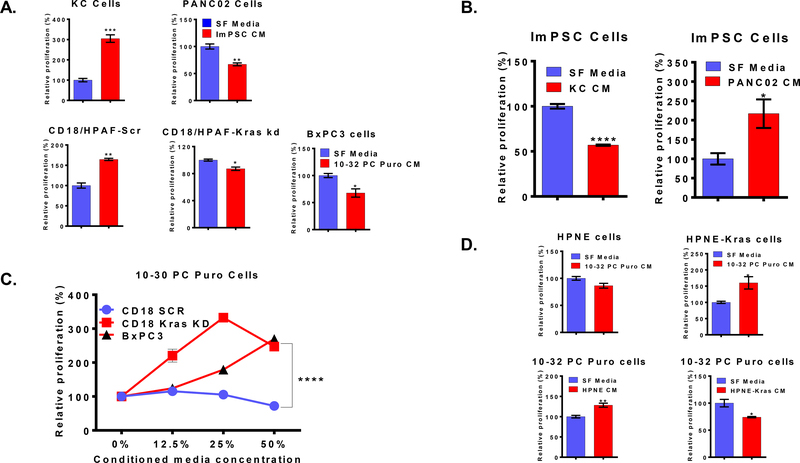

Kras-dependent paracrine inter-talk between CAFs and PDAC cells

We examined whether there is a paracrine inter-talk between tumor cells and CAFs. We utilized unidirectional co-culture techniques for this purpose. The proliferation of PDAC cells was measured following treatment with conditioned media collected from the CAFs ImPSC (murine) or 10–32 PC Puro (human). Relative to the treatment with serum-free media, ImPSC promoted the growth of tumor cells with activated oncogenic Kras (KC) while inhibiting cells with wildtype Kras (Panc02). Similarly, the conditioned media of human CAFs cell line 10–32 PC Puro enhanced the growth of CD18/HPAF-Scr, which possesses oncogenic Kras, while inhibited the growth of CD18/HPAF-Kras kd (with oncogenic Kras knockdown) and BxPC3 cells (with wildtype Kras) (Figure 1A). Next, we decided to investigate if the Kras-dependent differential response present also in CAFs treated with PDAC cells conditioned media. Conditioned media of PDAC cells carrying oncogenic Kras mutation (KC) inhibited the growth of ImPSC cells contrary to Kras wildtype cells (Panc02) that enhanced CAFs growth (Figure 1B). Similarly, BxPC3 cells and CD18/HPAF-Kras KD cells conditioned media promoted the growth of 10–32 PC Puro CAFs, when the CD18/HPAF-Scr has inhibited their growth (Figure 1C). However, we observed no noticeable morphologic changes when the PDAC cells were treated with CAF conditioned media, or the CAFs were treated with cancer cell-conditioned medium.

Figure 1: Kras status of PDAC cells determines the growth response in tumor cells and CAFs:

(A) The proliferation of murine PDAC cell lines (KC and Panc02) treated with conditioned media of the CAFs cell line (ImPSC) relative to serum-free media treatment, and the proliferation of human PDAC cell lines treated with conditioned media of the CAFs cell line (10–32 PC Puro) relative to serum-free media treatment. (B) The proliferation of ImPSC cells treated with conditioned media of PDAC cell lines relative to serum-free media treatment. (C) The proliferation of the human CAFs cell line (10–32 PC Puro) treated with conditioned media of PDAC cell lines relative to serum-free media treatment. (D) The proliferation of immortalized human pancreatic ductal cell lines treated with conditioned media of the CAFs cell line (10–32 PC Puro) relative to serum-free media treatment and proliferation of the human CAFs cell line (10–32 PC Puro) treated with conditioned media of pancreatic ductal cell lines relative to serum-free media treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA when appropriate. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001.

To confirm this observation, we utilized immortalized human pancreatic duct-derived cell lines that express exogenous Kras(G12D) (HPNE-Kras) or those normally express wildtype Kras (HPNE). The conditioned media of 10–32 PC Puro cells enhanced the growth of HPNE-Kras; whereas, HPNE-Kras conditioned media inhibited the growth of 10–32 PC Puro cells while HPNE conditioned media promoted it (Figure 1D). Together, the observations we described here the presence of Kras-dependent response orchestrated through paracrine factors secreted by tumor cells and stromal cells.

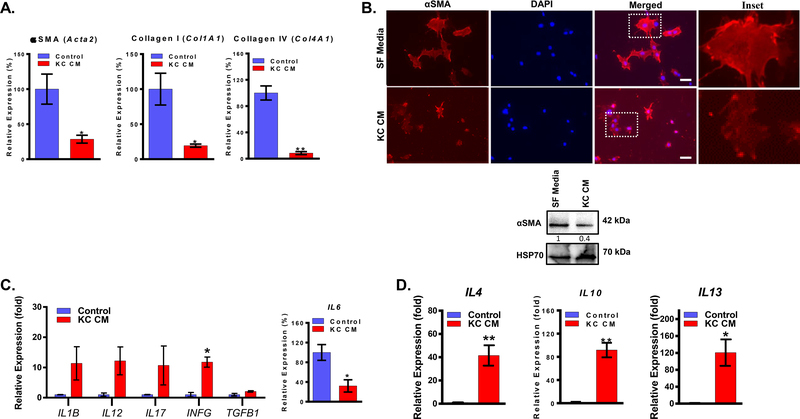

PDAC cells paracrine factors promote phenotype alterations in CAFs

Myofibroblasts are activated fibrotic cells that exhibit increased ECM synthesis and is characterized by the expression of αSMA as a marker. In cancer, myofibroblast was used synonymously to CAFs for many years [19–21]. We examined whether the PDAC cells-derived paracrine factors have any effect on the expression of myofibroblasts markers. ImPSC cells were treated with conditioned media of KC cells (oncogenic Kras mutation), Panc02, and BxPC3 cells (wildtype Kras mutation), and we investigated the expression of αSMA, Collagen I, and Collagen IV. KC conditioned media downregulated the mRNA expression of αSMA (Acta2) and the ECM proteins Collagen I (Col1A1) and Collagen IV (Col4A1) (Figure 2A). Similarly, Panc02 and BxPC3 conditioned media downregulated the mRNA expression of αSMA (Acta2) and the ECM proteins Collagen I (Col1A1), but Panc02 increased the expression of Collagen IV (Col4A1) (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the decrease of markers was lower when treated with wildtype Panc02 and BxPC3 than oncogenic KRAS. Furthermore, protein levels of αSMA determined by immunofluorescence and western blot showed that conditioned media of KC cells had decreased the expression of αSMA in ImPSC (Figure 2B). This indicates that oncogenic Kras promotes the secretion of paracrine factors that can alter CAFs away from their typical myofibroblast phenotype.

Figure 2: Paracrine factors of PDAC cells downregulates myofibroblasts markers and secrete immunosuppressive cytokines:

(A) Expression, determined by qPCR, of Acta2 (αSMA), Col1A1 (Collagen I), and Col4A1 (Collagen IV) in ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media relative to serum-free media for 24h treatment. (B) Expression of αSMA in ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media for or serum-free media for 72h determined by immunofluorescence and western blot. (C) Expression, determined by qPCR, of selected cytokines in ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media relative to serum-free media for 24h treatment. (D) Expression, determined by qPCR, of IL4, IL10, and IL13 in ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media relative to serum-free media for 24h treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. Scale bar = 50μm.

Ohlund et al. described the presence of a CAFs phenotype with a higher secretory function and a lower fibrotic function [22]. To determine if the Kras-promoted CAFs phenotype alterations are associated with a secretory function, we assessed the expression of multiple cytokines in ImPSC cells treated with conditioned media of KC cells in comparison to serum-free media control. The analysis of mRNA levels indicated several changes in the expression of multiple cytokines; however, IL6 expression was downregulated contrary to expectations (Figure 2C). Nonetheless, there was a significant upregulation of pro-tumorigenic cytokines, including IL4, IL10, and IL13 (Figure 2D). However, ImPSC cells treated with Panc02 and BxPC3 conditioned media did not demonstrate significant upregulation of cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 2). We observed similar results with the treatment of 10–32 PC Puro cells with isogenic cell line CD18-Scr and CD18-Kras-kd conditioned media (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, we demonstrate that the activation of oncogenic Kras in PDAC promotes the secretion of paracrine factors that contribute to modulating CAFs by altering them into a phenotype with more secretory function and lower fibrogenic features.

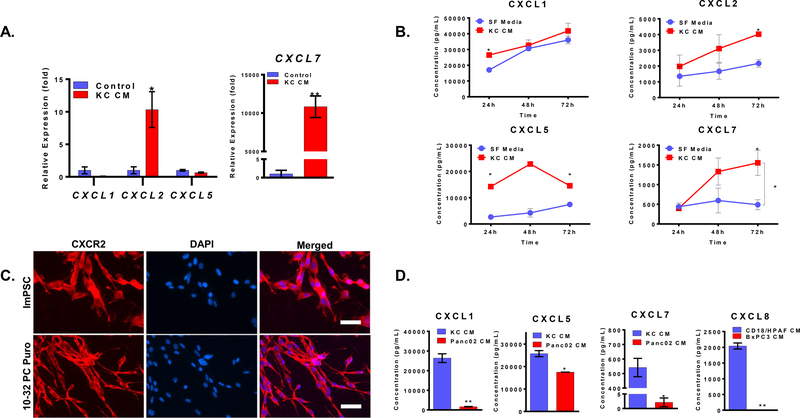

CAFs express CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands

CXCR2 ligands are known to play an adverse role in PDAC, mainly by promoting tumorigenesis, immunosuppression, and angiogenesis [8, 10, 11]. Analysis of CXCR2 chemokines revealed enhanced mRNA expression of CXCL2 and CXCL7 in ImPSC cells in response to the KC conditioned media treatment (Figure 3A). Similar enhanced mRNA expression of CXCR2 ligands was absent in ImPSC cells in response to the treatment with Panc02 and BxPC3 conditioned media (Supplementary Fig. 3). We also observed an increased expression of CXCL7 in 10–32 PC Puro cells with treatment of CD18-Scr in comparison with CD18-Krad kd or serum-free conditioned media (Supplementary Fig. 3). Analysis of the levels of chemokines in the supernatant of ImPSC cells showed that CAFs express high baseline levels of CXCL1 and CXCL5, moderate levels of CXCL2, and lower levels of CXCL7. Treating CAFs with conditioned media of KC cells did not increase CXCL1 or CXCL5 but slightly increased CXCL2 and significantly increased CXCL7 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: PDAC paracrine factors enhances the production of CXCR2 ligands:

(A) Expression, determined by qPCR, of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, and CXCL7 in ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media relative to serum-free media for 24h treatment. (B) The concentration of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, and CXCL7, as determined by ELISA, in the supernatant of ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media or serum-free media for 24, 48, or 72h. (C) Representative microscopic image of CXCR2 expression, determined by IF, in ImPSC and 10–32 PC Puro CAFs. (D) The concentration of CXCL1, CXCL5, and CXCL7 in the conditioned media of KC and Panc02 cells, and concentration of CXCL8, in the conditioned media of CD18/HPAF scr and BxPC3 cells, as determined by ELISA. The treatment was given for 72h. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA when appropriate. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. Scale bar = 50μm.

According to Ohlund et al., the secretory CAF phenotype developed at a distance from tumor cells implicating far-reaching paracrine factors like chemokines [22]. The paracrine factors CXCL1–3 and CXCL5–8 signal through the CXCR2 chemokine receptor [9, 10]. Our group has previously demonstrated the presence of a link between the activation of oncogenic Kras and the upregulation of CXCR2 ligands in PDAC [8]. We observed higher CXCR2 ligand expression in HPNE-Kras and CD18-Scr in comparison with HPNE and CD18-Kras kd, respectively [8]. Furthermore, our group has also reported that the stromal ablation of CXCR2 increased the fibrotic reaction in the syngeneic KC mouse model of PDAC, suggesting a role of CXCR2 signaling in regulating the fibrotic component in PDAC [15]. Thus, we decided to investigate if CXCR2 signaling is involved in the CAFs phenotype alterations. We started by confirming that our CAF cell lines express CXCR2 using immunofluorescence (Figure 3C); then, we used ELISA to measure CXCR2 ligands concentrations in the conditioned media of PDAC cells. KC conditioned media expresses more CXCL1, CXCL5, and CXCL7 than Panc02 (Figure 3D), and CD18/HPAF produced more CXCL8 than BxPC3 (Figure 3D). This set of experiments demonstrates that CAFs express CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands as well, and the expression of these ligands increases in the response of KC conditioned media. Thus, CAFs being positive for CXCR2 expression can respond to differential paracrine signals of pancreatic cancer cells by upregulating CXCR2 ligands. This contributes to the overall paracrine signaling within the tumor microenvironment, but, there is a possibility that this may be an autocrine effect that helps maintain CAFs secretory phenotype.

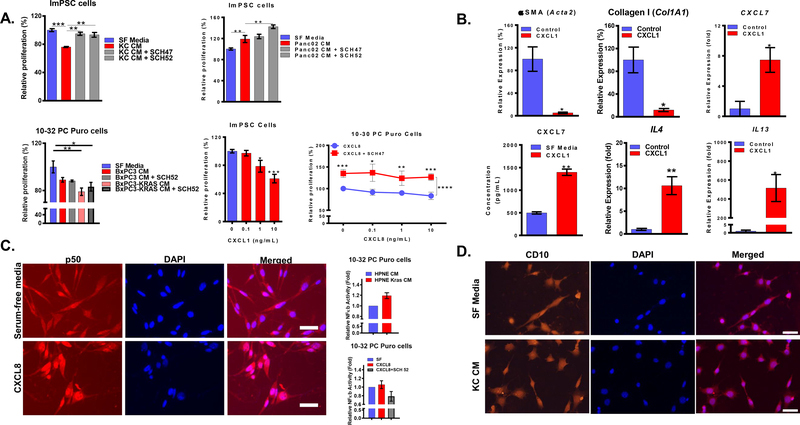

CXCR2 signaling in CAFs promotes the secretory phenotype by activating NF-κB

To assess the involvement of CXCR2 signaling in CAFs orientation, we treated ImPSC cells with conditioned media of KC or Panc02 cells in the presence or absence of CXCR2 pharmacological inhibitors. Blocking CXCR2 reduced the inhibitory effect of KC conditioned media and increased the growth stimulatory effect of Panc02 (Figure 4A). We observed similar results with the treatment of 10–32 Puro cells with conditioned media of isogenic BxPC3 and BxPC3-Kras cells in the presence or absence of CXCR2 inhibitors. (Figure 4A). Recombinant CXCL1 exhibited a dose-dependent inhibition of the growth of ImPSC cells similar to growth inhibition induced by treating 10–32 PC Puro cells with a recombinant CXCL8 that was reduced with CXCR2 inhibitor (Figure 4A). Lastly, ImPSC cells treated with recombinant CXCL1 downregulated Acta2 (αSMA) and Col1A1 (Collagen I) and upregulated IL4, IL13, and CXCL7 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4: CXCR2 signaling in CAFs induces a secretory phenotype:

(A) The proliferation of ImPSC cells treated with conditioned media of PDAC cell lines ± CXCR2 inhibitors (50 μg/mL) relative to serum-free media treatment; the proliferation of the ImPSC cells treated with increasing concentrations of recombinant CXCL1 (0–10 ng/mL) and the proliferation of 10–32 PC Puro cells treated with recombinant CXCL8 (0–10 ng/mL) ± CXCR2 inhibitors (50 μg/mL) relative to serum-free media for 72h treatment. (B) Expression, determined by qPCR, of Acta2, Col1A1, IL4, IL13 and CXCL7, and concentration of CXCL7, determined by ELISA, in ImPSC cells treated with recombinant CXCL1 (10 ng/mL) relative to serum-free media for 72h treatment. (C) Representative immunofluorescence image of p50 in 10–32 PC Puro cells treated with recombinant CXCL8 (10 ng/mL) or serum-free media for 2h; Fold change of NF-κb activity in 10–32 PC Puro cells with treatment of HPNE and HPNE Kras conditioned media, serum-free, CXCL8 (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of CXCR2 inhibitor (50 μg/mL). (D) Representative immunofluorescence image of CD10 in ImPSC cells treated with KC conditioned media or serum-free media. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA when appropriate. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. Scale bar = 50μm.

NF-κB is a transcription factor that has strong ties to both inflammation and cancer [34]. Furthermore, oncogenic Kras and CXCR2 have been reported to contribute to tumor progression through NF-κB [35–37]. Lastly, a new report described that NF-κB activation gives rise to a secretory subset of CAFs in breast and lung cancers that express GPR77 and CD10, which could be new markers for the secretory CAFs [23]. We investigated the involvement of the CXCR2 signaling in CAFs in NF-κB activation and CD10 expression. 10–32 PC Puro cells treated with HPNE-Kras conditioned media in comparison with HPNE (Figure 4C) and 10–32 PC Puro cells treated with CXCL8 in comparison with serum-free showed increased NF-κB nuclear translocation, an indication of increased NF-κB activity (Figure 4C). Blocking CXCR2 was able to reduce this NF-κB activity (Figure 4C). CD10 expression in ImPSC cells was not changed in response to KC conditioned media (Figure 4D). Collectively, we demonstrate that CXCR2 signaling in CAFs of PDAC causes activation of NF-κB that causes CAFs to assume a secretory phenotype.

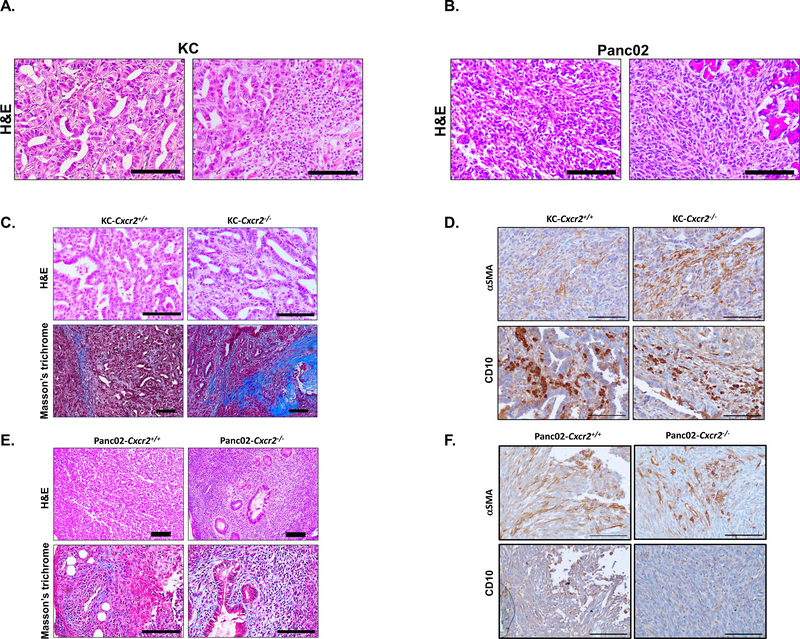

CXCR2 inhibition renders different impact based on PDAC mutations

We have determined that oncogenic Kras upregulates the CXCR2 ligands, which modulates CAFs orientation and activity. To investigate the role of PDAC mutations in-vivo, we utilized syngeneic mouse models transplanted with KC cells that carry oncogenic Kras [38] or Panc02 that carry wildtype Kras [30]. Histological assessment of KC tumor exhibited well-differentiated tumors with abundant duct formation, low to moderate infiltration of CAFs, and a high inflammatory infiltration, in particular, polymorph nuclear cells (Figure 5A). Panc02 tumors were undifferentiated with no to little duct formation and a high infiltration of CAFs (Figure 5B).

Figure 5: Kras-dependent CAFs distribution and effect of CXCR2 inhibition on stromal activity in-vivo:

(A) Representative image with H&E staining of tumors derived from KC implanted syngeneic mouse models showing the well-differentiated histology (left) and the abundant polymorph nuclear cells infiltration (right). (B) Representative image with H&E staining of tumors derived from Panc02 implanted syngeneic mouse models showing the undifferentiated histology (left) and the abundant CAFs infiltration (right). Scale bar = 100μm. (C) Representative immunohistochemistry images with H&E or Masson’s trichrome staining of tumors derived from KC implanted syngeneic mouse models. (D) Representative immunohistochemistry images of tumors derived from KC implanted syngeneic mouse models showing αSMA or CD10 staining. (E) Representative immunohistochemistry images with H&E or Masson’s trichrome staining of tumors derived from Panc02 implanted syngeneic mouse models. (F) Representative immunohistochemistry images of tumors derived from KC implanted syngeneic mouse models showing αSMA or CD10 staining. Scale bar = 100μm.

Next, we aimed to investigate the effect of the stromal CXCR2 deletion in the context of PDAC mutations. We utilized the syngeneic PDAC model of KC and Panc02 that implanted in Cxcr2−/− or wildtype. Our focus here was to assess the impact of CXCR2 deletion on CAFs and if it is linked to changes in the context of oncogenic Kras. In KC tumors, the deletion of CXCR2 did not exhibit alteration to the differentiation stage of the tumor cells; however, the primary observation was the increase of fibrotic reaction (Figure 5C). The increased fibrotic reaction in the KC model was associated with increased αSMA+ and with no difference in CD10+ CAFs, suggesting a diminished secretory CAFs repertoire (Figure 5D). CXCR2 knockout in Panc02 implanted mice seemed to have a more prominent anti-tumor effect. CXCR2 stromal deletion appears to ameliorate the aggressiveness of the tumor cells in Panc02 tumors, which was presented as increased ducts formation indicating a transformation from undifferentiated to poorly differentiated tumor (Figure 5E). Moreover, there was no noticeable change to the fibrotic reaction or the abundance of CAFs as there was no difference between αSMA+ and CD10+ staining (Figure 5F). Collectively, we demonstrate a mutation-dependent histological difference in PDAC and show that CXCR2 plays a role in stromal compartments. However, in both KC and Panc02 that implanted cells in Cxcr2−/− or wildtype mice, we observed no difference in the tumor growth but increased metastasis in CXCR2−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

PDAC, one of the most malignant tumors, is characterized by both tumor-supporting inflammation and abundant desmoplastic reaction [7, 39, 40]. Oncogenic Kras that occur early during PDAC progression is associated with an inflammatory signal such as CXCR2 [7, 8]. CXCR2 signaling in many cancer, including PDAC, has been proven adverse by contributing to tumor growth, immunosuppression, angiogenesis, and chemotherapy resistance [11, 41, 42]. CAFs are significant contributors to desmoplasia in many cancers, including PDAC [43]. Desmoplasia adds to tumorigenicity by supporting therapy hindrance and resistance, and metastasis [44]. CAFs for long have been regarded as myofibroblasts characterized by expression of αSMA and ECM proteins [19, 20]. Although CAFs have been known to secrete several paracrine factors, including CXCR2 ligands [20, 21, 41], it is only recently that this secretory function gained enough attention. Recent reports described distinct CAFs subsets with a specialized secretory function [22, 23]. Several studies suggested the presence of a relationship between CXCR2 signaling and stromal activity [45, 46]. Our group has demonstrated that the stromal ablation of CXCR2 enhances fibrosis [15]. The secretory CAFs phenotype was described to develop when there is no adjacency to the tumor cells [22], which suggests the involvement of far-reaching paracrine molecules such as CXCR2 ligands. The purpose of the present study was to determine the role of oncogenic Kras-CXCR2 axis in CAFs activity and function in PDAC.

Our data indicate a growth stimulatory effect of CAFs-derived paracrine factors on PDAC cells with oncogenic Kras but not PDAC cells with wildtype Kras. On the other hand, PDAC cells-derived paracrine factors stimulated CAFs growth when the cells had wildtype Kras and inhibited CAFs growth when the cells had oncogenic Kras mutation. This Kras-dependent response was shown to extend beyond tumor cell proliferation to alter the expression of myofibroblast CAFs-associated proteins, including αSMA and ECM synthesis, and to upregulates pro-tumor cytokines and chemokines. However, the reduced proliferation in CAFs with the upregulation of cytokines associated with oncogenic KRAS, also indicate a possibility of the stress response. By investigating the putative mechanisms by which these CAFs phenotype alterations occurred, we determined that CXCR2 signaling in CAFs is involved. Blocking CXCR2 ameliorated the inhibitory effect of the oncogenic Kras tumor cells paracrine factors and further enhanced the stimulatory effect of wildtype cells.

Furthermore, recombinant CXCR2 ligands treatment altered the expression profile in CAFs to reduce myofibroblasts markers and to upregulate pro-tumor paracrine factors. Lastly, we determined that the CXCR2-induced secretory function in CAFs is mediated through NF-κB activation. We also confirmed that the secretory phenotype express CD10, a marker that has been recently linked to secretory CAFs in breast and lung cancers [23]. Using syngeneic mouse models, we demonstrated mutation-dependent distinct histological features of PDAC cells as well as CAFs compartments, and that inhibiting CXCR2 could render different effects.

It is known that CAFs population is heterogeneous by cell origins [18]; however, the functional heterogeneity is a novel concept. Myofibroblast is the typical CAFs phenotype; but, there is more attention now to subsets of CAFs with a specialized secretory function [22, 23]. Albeit, the notion of secretory roles of CAFs is not new. It is known that CAFs express many receptors and secrete many paracrine factors; however, this was mainly attributed to CAFs’ versatility rather than their specialized functional subsets [19–21]. Looking into literature, we can find reports that have described what seems to be an abundant secretory function in CAFs. For example, chemotherapy treatment of breast cancer and PDAC induced senescence in CAFs and activated inflammatory transcription factors, including NF-κB and STAT1, which resulted in the upregulation of CXCR2 ligands that influenced chemotherapy resistance by promoting cancer stemness [41]. Senescent CAFs have been reported to assume secretory functions. For example, senescent CAFs were reported to produce inflammatory mediators such as CXCL8 and interleukin- (IL-)6, which contributed to tumor growth, tumor cell migration, and epithelial differentiation alteration [47–49]. Both oncogenic Kras and CXCR2 have links to senescence, which is mediated through the activation of inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB [50]. The data which we have collected suggests that KRAS/CXCR2 axis is associated with the abundance of the secretory phenotype CAFs. However, our results do not distinguish whether this abundance occurs as a result of the transformation or selection of CAFs. Hence, if we assume that this process is a selection process, then it is likely that CXCR2 paracrine signaling selects CAFs with inherent secretory properties.

Markers such as αSMA, fibroblast activation protein α (FAP), and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFR) have been utilized to identify CAFs [19–21]. Nonetheless, targeting CAFs using αSMA depletion rendered an adverse outcome by accelerating tumor progression as a result of enhanced therapy resistance and immunosuppression [24, 25]. Based on our current knowledge, we believe that the adverse outcome was a consequence of increasing the abundance of the secretory CAFs. Taken together, it is clear that the markers that have been heavily utilized are likely not uniformly expressed on CAFs; but, it is not clear if this because of CAFs origin or functional heterogeneity. We are warranted to dive further into the CAFs biology and attain better markers that allow targeting CAFs safely. There is not much we know about putative markers for the secretory CAFs. In PDAC, the secretory CAFs were described to express FAP and to have a low expression of αSMA [22]. The secretory CAFs described in the breast, and lung cancer had a similar expression of αSMA, FAP, and PDGFR to the other CAFs; however, they were identified using other surface markers such as GPR77 and CD10 [23]. CD10, a small metalloprotease, is known as a prognostic marker in hematological malignancies [51]. In solid tumors, stromal cells that express CD10 have been identified in several cancers, including PDAC, in which CD10+ CAFs promoted tumor cell growth and was associated with reduced survival and nodal metastasis [52]. Based on our observation in this study, we believe that CD10 is expressed on both myofibroblast and secretory CAFs. It is not clear, however, if all the CD10+ CAFs carry out a secretory function or if all the secretory CAFs express CD10.

Deleting CXCR2 has been attempted before and exhibited beneficial outcomes in some cases and adverse outcomes in others. Previously our group has also reported that the loss of CXCR2 in tumor cells has halted tumor cells proliferation and increased their apoptosis [8]. Our group did not evaluate invasion, metastasis or survival in this model. However, Steele at al. showed decreased liver metastasis in the global Cxcr2 knockout in the KPC model but no effect when they knocked out Cxcr2 only in the tumor cells, which means metastasis-promoting activity of Cxcr2 in the surrounding environment, not in the tumor cells [45]. Thus, CXCR2 has been suggested to have both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressive properties. This suggests that before we can target CXCR2 in pancreatic tumor microenvironment further evaluation of CXCR2 inhibition in different components of tumor microenvironment is warranted.

Inhibiting CXCR2 in the context of Kras mutation alone, increased fibrosis and metastasis [15]; whereas, CXCR2 inhibition in the context of other mutations, such as p53 or Tgfbr2, rendered beneficial outcomes [45, 46]. Our data demonstrated that the pronounced anti-tumor effects of CXCR2 deletion were observed in tumors generated using Panc02 cells that carry a wildtype Kras and a Smad4 mutation [30]. Oncogenic Kras mutation occurs early during PDAC pathogenesis; whereas, mutations of the tumor suppressors are often late events [6]. This observation could suggest a temporal context for the beneficial or adverse outcomes of CXCR2 inhibition, in which inhibiting CXCR2 in early PDAC could render accelerated disease and inhibiting CXCR2 in late stages could tame the disease.

In conclusion, we report that CXCR2 signaling plays a role in regulating the CAFs of PDAC; thus, affecting the tumor outcome. Further studies are required to characterize CAFs subsets and identify better markers than currently available. Furthermore, there is a need for a better understating of the temporal and mutation context of CXCR2 roles in PDAC. We have demonstrated that both targeting CAFs and targeting CXCR2 could have context-dependent outcomes. Both could still be good potential targets for treating PDAC, pending better understanding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by grants R01CA228524, and Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA036727) from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Mohammad Awaji, as a graduate student was supported by a scholarship from King Fahad Specialist Hospital-Dammam and the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission in the USA, and a pre-doctoral fellowship from the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

GLOSSARY

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- CD10

Cluster of differentiation 10

- CXCR2

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2

- ECM

Extra-cellular Matrix

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FAP

Fibroblast activation protein α

- GPR77

G protein-coupled receptor 77

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IL-

Interleukin-

- Kras

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- P53

Tumor protein p53

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PDGFR

Platelet-derived growth factor receptors

- Smad4

Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4

- αSMA

α-smooth muscle actin

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD & Jemal A (2018) Cancer statistics, 2018, CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hidalgo M (2010) Pancreatic Cancer, New England Journal of Medicine. 362, 1605–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH & Theise ND (2010) WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fesinmeyer MD (2005) Differences in Survival by Histologic Type of Pancreatic Cancer, Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 14, 1766–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hruban RH, Maitra A, Kern SE & Goggins M (2007) Precursors to Pancreatic Cancer, Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 36, 831–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hruban RH & Fukushima N (2007) Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: update on the surgical pathology of carcinomas of ductal origin and PanINs, Modern Pathology. 20, S61–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgart S, Chen NM, Siveke JT, Konig A, Zhang JS, Singh SK, Wolf E, Bartkuhn M, Esposito I, Hessmann E, Reinecke J, Nikorowitsch J, Brunner M, Singh G, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Smyrk T, Bamlet WR, Eilers M, Neesse A, Gress TM, Billadeau DD, Tuveson D, Urrutia R & Ellenrieder V (2014) Inflammation-Induced NFATc1-STAT3 Transcription Complex Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Initiation by KrasG12D, Cancer Discovery. 4, 688–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purohit A, Varney M, Rachagani S, Ouellette MM, Batra SK & Singh RK (2016) CXCR2 signaling regulates KRAS(G(1)(2)D)-induced autocrine growth of pancreatic cancer, Oncotarget. 7, 7280–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bizzarri C, Beccari AR, Bertini R, Cavicchia MR, Giorgini S & Allegretti M (2006) ELR+ CXC chemokines and their receptors (CXC chemokine receptor 1 and CXC chemokine receptor 2) as new therapeutic targets, Pharmacol Ther. 112, 139–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Mestas J, Gomperts B, Keane MP & Belperio JA (2006) Cancer CXC chemokine networks and tumour angiogenesis, Eur J Cancer. 42, 768–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Highfill SL, Cui Y, Giles AJ, Smith JP, Zhang H, Morse E, Kaplan RN & Mackall CL (2014) Disruption of CXCR2-Mediated MDSC Tumor Trafficking Enhances Anti-PD1 Efficacy, Science translational medicine. 6, 237ra67–237ra67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar V, Donthireddy L, Marvel D, Condamine T, Wang F, Lavilla-Alonso S, Hashimoto A, Vonteddu P, Behera R, Goins MA, Mulligan C, Nam B, Hockstein N, Denstman F, Shakamuri S, Speicher DW, Weeraratna AT, Chao T, Vonderheide RH, Languino LR, Ordentlich P, Liu Q, Xu X, Lo A, Pure E, Zhang C, Loboda A, Sepulveda MA, Snyder LA & Gabrilovich DI (2017) Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Neutralize the Anti-tumor Effect of CSF1 Receptor Blockade by Inducing PMN-MDSC Infiltration of Tumors, Cancer Cell. 32, 654–668.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waugh DJ & Wilson C (2008) The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer, Clin Cancer Res. 14, 6735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S, Varney M & Singh RK (2009) Host CXCR2-Dependent Regulation of Melanoma Growth, Angiogenesis, and Experimental Lung Metastasis, Cancer Research. 69, 411–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purohit A (2015) The Role of CXCR2 in Pancreatic Cancer Development and Progression. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu GC, Kimmelman AC, Hezel AF & DePinho RA (2007) Stromal biology of pancreatic cancer, Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 101, 887–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleeff J, Beckhove P, Esposito I, Herzig S, Huber PE, Lohr JM & Friess H (2007) Pancreatic cancer microenvironment, Int J Cancer. 121, 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Öhlund D, Elyada E & Tuveson D (2014) Fibroblast heterogeneity in the cancer wound, The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 211, 1503–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moir JA, Mann J & White SA (2015) The role of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic cancer, Surg Oncol. 24, 232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apte MV, Wilson JS, Lugea A & Pandol SJ (2013) A starring role for stellate cells in the pancreatic cancer microenvironment, Gastroenterology. 144, 1210–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omary MB, Lugea A, Lowe AW & Pandol SJ (2007) The pancreatic stellate cell: a star on the rise in pancreatic diseases, J Clin Invest. 117, 50–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M, Corbo V, Oni TE, Hearn SA, Lee EJ, Chio II, Hwang CI, Tiriac H, Baker LA, Engle DD, Feig C, Kultti A, Egeblad M, Fearon DT, Crawford JM, Clevers H, Park Y & Tuveson DA (2017) Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer, J Exp Med. 214, 579–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su S, Chen J, Yao H, Liu J, Yu S, Lao L, Wang M, Luo M, Xing Y, Chen F, Huang D, Zhao J, Yang L, Liao D, Su F, Li M, Liu Q & Song E (2018) CD10(+)GPR77(+) Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote Cancer Formation and Chemoresistance by Sustaining Cancer Stemness, Cell. 172, 841–856.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Özdemir Berna C., Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens Julienne L., Zheng X, Wu C-C, Simpson Tyler R., Laklai H, Sugimoto H, Kahlert C, Novitskiy Sergey V., De Jesus-Acosta, Sharma A, Heidari P, Mahmood P, Chin U, Moses L, Harold L, Weaver Valerie M., Maitra A., Allison, James P, Le Bleu, Valerie S & Kalluri R (2014) Depletion of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis Induces Immunosuppression and Accelerates Pancreas Cancer with Reduced Survival, Cancer Cell. 25, 719–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhim Andrew D., Oberstein Paul E., Thomas Dafydd H., Mirek Emily T., Palermo Carmine F., Sastra Stephen A., Dekleva Erin N., Saunders T, Becerra Claudia P., Tattersall Ian W., Westphalen CB, Kitajewski J, Fernandez-Barrena, Fernandez-Zapico Maite G., Iacobuzio-Donahue Martin E., Olive C, Kenneth P & Stanger Ben Z. (2014) Stromal Elements Act to Restrain, Rather Than Support, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Cancer Cell. 25, 735–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres MP, Rachagani S, Souchek JJ, Mallya K, Johansson SL & Batra SK (2013) Novel pancreatic cancer cell lines derived from genetically engineered mouse models of spontaneous pancreatic adenocarcinoma: applications in diagnosis and therapy, PLoSONE. 8, e80580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathison A, Liebl A, Bharucha J, Mukhopadhyay D, Lomberk G, Shah V & Urrutia R (2010) Pancreatic Stellate Cell Models for Transcriptional Studies of Desmoplasia-Associated Genes, Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) [et al. ]. 10, 505–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell PM, Groehler AL, Lee KM, Ouellette MM, Khazak V & Der CJ (2007) K-Ras promotes growth transformation and invasion of immortalized human pancreatic cells by Raf and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling, Cancer Res. 67, 2098–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rachagani S, Senapati S, Chakraborty S, Ponnusamy MP, Kumar S, Smith LM, Jain M & Batra SK (2011) Activated KrasG(1)(2)D is associated with invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells through inhibition of E-cadherin, Br J Cancer. 104, 1038–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Zhang Y, Yang J, Ni X, Liu S, Li Z, Hodges SE, Fisher WE, Brunicardi FC, Gibbs RA, Gingras MC & Li M (2012) Genomic sequencing of key genes in mouse pancreatic cancer cells, Curr Mol Med. 12, 331–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML & Singh RK (2002) Interleukin-8-induced proliferation, survival, and MMP production in CXCR1 and CXCR2 expressing human umbilical vein endothelial cells, Microvasc Res. 64, 476–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuo Y, Takeyama H & Guha S (2012) Cytokine network: new targeted therapy for pancreatic cancer, Curr Pharm Des. 18, 2416–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki A, Leland P, Joshi BH & Puri RK (2015) Targeting of IL-4 and IL-13 receptors for cancer therapy, Cytokine. 75, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiDonato JA, Mercurio F & Karin M (2012) NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer, Immunol Rev. 246, 379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richmond A (2002) NF-κB, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth, Nature Reviews Immunology. 2, 664–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling J, Kang Y. a., Zhao R, Xia Q, Lee D-F, Chang Z, Li J, Peng B, Fleming, Wang Jason B., Liu H, Lemischka J, Ihor R, Hung M-C & Chiao Paul J. (2012) KrasG12D-Induced IKK2/β/NF-κB Activation by IL-1α and p62 Feedforward Loops Is Required for Development of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Cancer Cell. 21, 105–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walana W, Wang J-J, Yabasin IB, Ntim M, Kampo S, Al-Azab M, Elkhider A, Dogkotenge Kuugbee E, Cheng J. w., Gordon JR & Li F (2018) IL-8 analogue CXCL8 (3–72) K11R/G31P, modulates LPS-induced inflammation via AKT1-NF-kβ and ERK1/2-AP-1 pathways in THP-1 monocytes, Human Immunology. 79, 809–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres MP, Rachagani S, Souchek JJ, Mallya K, Johansson SL & Batra SK (2013) Novel pancreatic cancer cell lines derived from genetically engineered mouse models of spontaneous pancreatic adenocarcinoma: applications in diagnosis and therapy, PLoS One. 8, e80580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamada S, Masamune A & Shimosegawa T (2014) Inflammation and pancreatic cancer: disease promoter and new therapeutic target, Journal of gastroenterology. 49, 605–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR & Karin M (2010) Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer, Cell. 140, 883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan TS, Hsu CC, Pai VC, Liao WY, Huang SS, Tan KT, Yen CJ, Hsu SC, Chen WY, Shan YS, Li CR, Lee MT, Jiang KY, Chu JM, Lien GS, Weaver VM & Tsai KK (2016) Metronomic chemotherapy prevents therapy-induced stromal activation and induction of tumor-initiating cells, J Exp Med. 213, 2967–2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wente MN, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Friess H, Büchler MW, Ceyhan GO, Reber HA, Strieter RM & Hines OJ (2006) Blockade of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell-induced angiogenesis, Cancer Letters. 241, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCarthy JB, El-Ashry D & Turley EA (2018) Hyaluronan, Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and the Tumor Microenvironment in Malignant Progression, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 6, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, Madhu B, Goldgraben MA, Caldwell ME, Allard D, Frese KK, DeNicola G, Feig C, Combs C, Winter SP, Ireland-Zecchini H, Reichelt S, Howat WJ, Chang A, Dhara M, Wang L, Ruckert F, Grutzmann R, Pilarsky C, Izeradjene K, Hingorani SR, Huang P, Davies SE, Plunkett W, Egorin M, Hruban RH, Whitebread N, McGovern K, Adams J, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Griffiths J & Tuveson DA (2009) Inhibition of Hedgehog Signaling Enhances Delivery of Chemotherapy in a Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer, Science. 324, 1457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steele CW, Karim SA, Leach JD, Bailey P, Upstill-Goddard R, Rishi L, Foth M, Bryson S, McDaid K, Wilson Z, Eberlein C, Candido JB, Clarke M, Nixon C, Connelly J, Jamieson N, Carter CR, Balkwill F, Chang DK, Evans TR, Strathdee D, Biankin AV, Nibbs RJ, Barry ST, Sansom OJ & Morton JP (2016) CXCR2 Inhibition Profoundly Suppresses Metastases and Augments Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Cancer Cell. 29, 832–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ijichi H, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre ME, Bierie B, Tada M, Mohri D, Miyabayashi K, Asaoka Y, Maeda S, Ikenoue T, Tateishi K, Wright CV, Koike K, Omata M & Moses HL (2011) Inhibiting Cxcr2 disrupts tumor-stromal interactions and improves survival in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, J Clin Invest. 121, 4106–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang T, Notta F, Navab R, Joseph J, Ibrahimov E, Xu J, Zhu CQ, Borgida A, Gallinger S & Tsao MS (2017) Senescent Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts Upregulate IL8 to Enhance Prometastatic Phenotypes, Molecular cancer research: MCR. 15, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawrenson K, Grun B, Benjamin E, Jacobs IJ, Dafou D & Gayther SA (2010) Senescent Fibroblasts Promote Neoplastic Transformation of Partially Transformed Ovarian Epithelial Cells in a Three-dimensional Model of Early Stage Ovarian Cancer, Neoplasia (New York, NY). 12, 317–IN3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parrinello S (2005) Stromal-epithelial interactions in aging and cancer: senescent fibroblasts alter epithelial cell differentiation, Journal of Cell Science. 118, 485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lesina M, Wormann SM, Morton J, Diakopoulos KN, Korneeva O, Wimmer M, Einwachter H, Sperveslage J, Demir IE, Kehl T, Saur D, Sipos B, Heikenwalder M, Steiner JM, Wang TC, Sansom OJ, Schmid RM & Algul H (2016) RelA regulates CXCL1/CXCR2-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in murine Kras-driven pancreatic carcinogenesis, J Clin Invest. 126, 2919–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maguer-Satta V, Besancon R & Bachelard-Cascales E (2011) Concise review: neutral endopeptidase (CD10): a multifaceted environment actor in stem cells, physiological mechanisms, and cancer, Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio). 29, 389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ikenaga N, Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Cui L, Kayashima T, Morimatsu K, Moriyama T, Nakata K, Fujita H & Tanaka M (2010) CD10+ Pancreatic Stellate Cells Enhance the Progression of Pancreatic Cancer, Gastroenterology. 139, 1041–1051.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.