Abstract

Although the literature is growing regarding large-scale, system-wide implementation programs, the broader political and social contexts, including race and ethnicity, are frequently ignored. Using the Policy Ecology of Implementation framework (Raghavan, Bright, & Shadoin, 2008), Minnesota’s CEMIG is examined to investigate the role of social and political contexts in the implementation process and the barriers they create. Data from 22 interview transcripts from DHS administrators, agency grant managers, university educators, advocacy group representatives, and mental health board members, along with more than 1,000 grant documents were qualitatively analyzed using content analysis to reveal three themes concerning how the participants experienced program implementation: invisibility, isolation, and inequity. Findings demonstrate the participants perceived that the grant program perpetuated inequities by neglecting to promote the program, advocate for clinicians of color, and coordinate isolated policy ecology systems. Strategies for future large-scale, system-wide mental health program implementation are provided.

Keywords: Case study, Policy Ecology, race and ethnicity

Introduction

In the last few years, several large-scale, system-wide implementation initiatives in community mental health have been the subject of research inquiry. Often these studies focus on the individual clinician (Olin et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2017) or organizational characteristics that support adoption of EBPs (Skriner et al., 2017) within a large-scale, system-wide program. Recent literature has expanded the focus of inquiry to include social and policy levers within system-wide initiatives that can augment or hinder implementation (Stone, Daumit, Kennedy-Hendricks & McGinty, 2019; Walker et al., 2019). One potential analytic tool that helps uncover social and political factors, the Policy Ecology of Implementation (PEI) framework, was created to emphasize the role of the broader ecology in the implementation process (Raghavan et al., 2008). Using an ecological model, PEI views implementation in context with all of the systems that interact with an initiative (Raghavan et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2019) such as: the individual clinical encounter, provider agency, government regulatory agency, graduate training programs, political institutions (e.g., mental health boards and legislation), and social issues (e.g., stigma and cultural factors).

As large-scale, system-wide implementation efforts occur within racially and ethnically diverse jurisdictions across the country, such Los Angeles County (Brookmann-Frazee et al., 2016; Southam-Gerow et al., 2014); Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Beidas et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2017; Skriner et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2017); Illinois (Starin et al., 2014); Maryland (Stone et al., 2019); New York state (Nadeem et al., 2016; Olin et al., 2016); and Washington state (Walker et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2019), future programs would benefit from investigations of social and political factors, such as consumer advocacy, cultural competence, racial disparities, competing legislative priorities, and workforce development initiatives (Raghavan, Bright, & Shadoin, 2008; So, McCord, & Kaminski, 2019). Omitting larger social issues ignores long-standing concerns from cultural and ethnic minority groups regarding systemic racism (Wangari Walter et al., 2017), hidden bias amongst clinicians, “clinical colonization” (Willging et al., 2012), and historical oppression and cultural trauma (Walker, Whitener, Trumpin, & Migliarni, 2015). Additionally, social and political contexts relevant to the implementation process can perpetuate hidden bias within large systems by assuming that the needs of all clients and clinicians are the same (Wangari Walter et al., 2017) and that social structures (e.g., clinical licensure, education systems, and Medicaid regulations) apply equally across populations (Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010). Further, unaddressed structural racism is not only a potential implementation barrier, it also contributes to on-going oppression of cultural and ethnic populations (Wangari Walter et al., 2017).

Using the PEI as a theoretical framework, this current study, nested within a larger mixed-method multi-case study (Stake, 2005), seeks to develop nuanced explanations of how external forces influence implementation at the state government, grant-making agency, and individual clinician levels. The research questions that guided this case analysis include:

How do social and political contexts (Raghavan et al., 2008; e.g., race and ethnicity, disproportionality, and mental health board regulations) influence or create barriers in the implementation process of a large-scale, system-wide program?

What are strategies within the policy ecology (social, political, agency, organizational, and clinical encounter levels) that help improve the implementation process of a large-scale, system-wide program?

Given the aforementioned knowledge gaps, this study examines Minnesota’s Cultural and Ethnic Minority Infrastructure Grant (CEMIG) program to understand better how political and social contexts promote and limit policy implementation at the state level. The CEMIG program is a component of a larger infrastructure development initiative focused on access, quality, innovation, and accountability within Minnesota’s public mental health system (Department of Human Services [DHS], 2006). The state of Minnesota allocated $8.86 million from 2008 through 2016 to fund 21 agencies in workforce development efforts, clinical and ancillary services, and EBP training for cultural and ethnic minority populations.

This study examines the perspectives and experiences of DHS grant administrators, agency grant managers, mental health board representatives, faculty in graduate clinical training programs, and cultural minority clinician advocacy group leaders regarding the social and political contexts of statewide program implementation. A greater understanding of how social and political factors are experienced at each level of the policy ecology is crucial, as these perspectives are rarely discussed within implementation literature. Addressing systemic racism and hidden biases within implementation processes are needed and can assist in future large-scale, system-wide projects with multicultural populations. After a brief overview of the PEI framework, methods (including the study context) will be described, followed by the research methodology, findings, and implications for future practice.

Policy Ecology of Implementation Framework

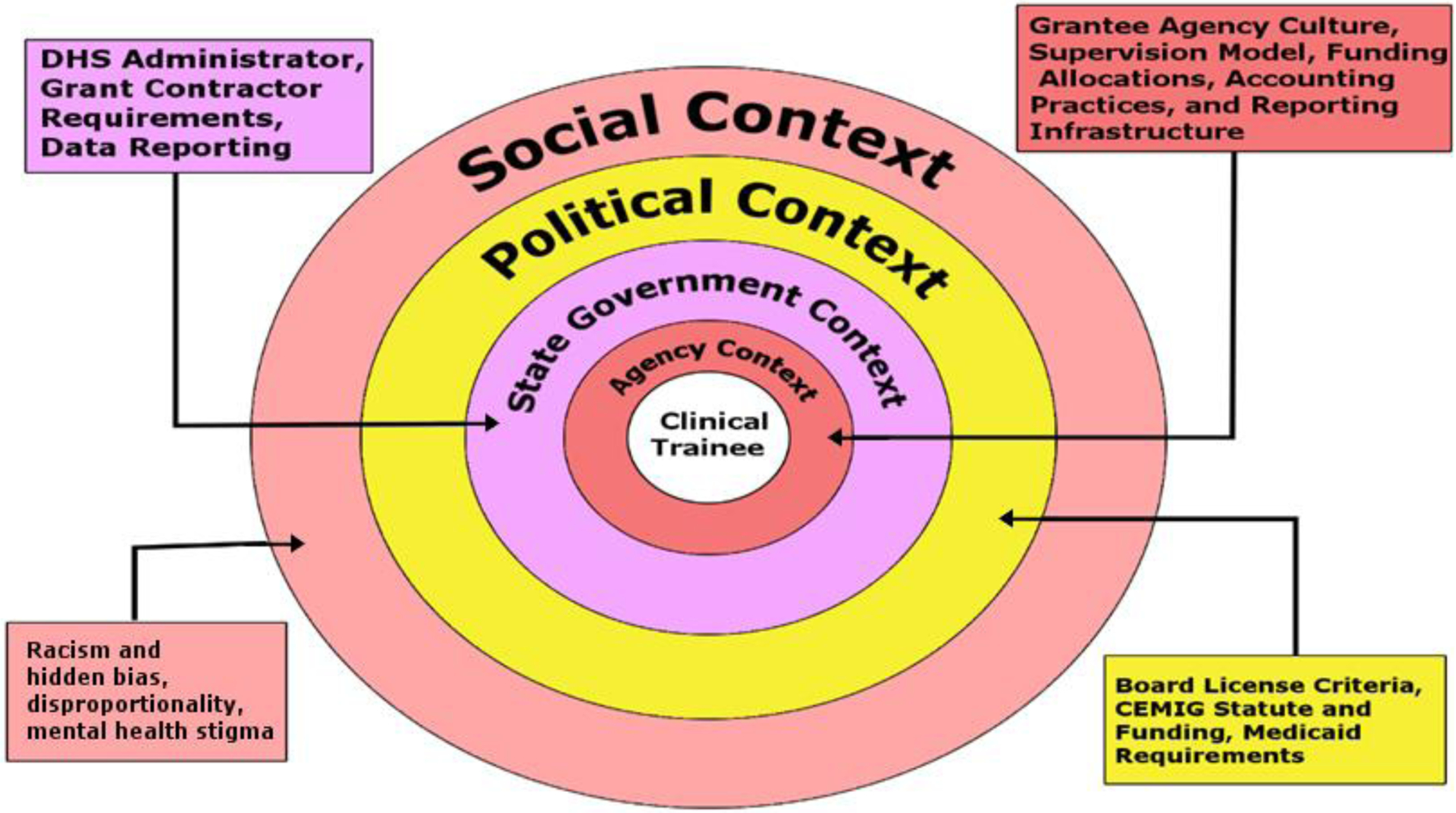

The PEI framework focuses on the ecology surrounding the individual clinical encounter using an EBP (Raghavan et al., 2008). While this framework was written in regards to EBP implementation (Raghavan et al., 2008), it is also helpful in analyzing the implementation of promising practices or statewide policy implementation (Stone, Daumit, Kennedy-Hendricks, & McGinty, 2019). PEI addresses the multiple contexts that influence therapy provision: the organizational (enhanced reimbursement, training and continuing education units), agency (contracts and bids, insurance payment systems, outcome assessments), political (legislation, parity laws, loan forgiveness, elimination of structural stigma, consumer involvement), and social (stigma; Raghavan et al., 2008). The PEI framework focuses on policy levers, strategies that policymakers use at different levels to affect clinical encounters through provider agencies, regulatory or purchaser agencies (such as DHS), state and federal legislation, and mental health stigma or racial bias (Raghavan et al., 2008). The framework is often cited for bringing payment strategies (e.g., enhanced reimbursement rates), professional organizational factors (e.g., EBP continuing education requirements), and regulation congruence (e.g., group psychotherapy requirements matching EBP fidelity standards) to the forefront when implementing EBPs (Wiltsey Stirman, Gutner, Langdon, & Graham, 2016). Because this conceptual framework is structured to look at implementation within an ecological context, it is well suited for addressing system interactions and competing factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Policy Ecology of Implementation for the CEMIG program.

Adapted from “Toward a Policy Ecology of Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices in Public Mental Health Settings,” by R. Raghavan, C. L. Bright, & A. Shadoin, 2008, Implementation Science, 3, p. 26. doi:10.1186/748-5908-3-26

The PEI framework has been often mentioned in the literature to reference critical ingredients that are beneficial for successful implementation, but it has sparingly been applied. PEI was used to describe the transformation of Philadelphia’s behavioral health system (Powell et al., 2016), the proliferation of EBP usage in Washington state (Walker et al., 2019), and policy congruence surrounding Maryland’s Medicaid Health Home Program (Stone et al., 2019). Authors described intervention strategies utilized by implementers that addressed potential barriers at the social, political, agency, organizational, and clinical-encounter levels (Powell et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2019) and needed policy modifications to support implementation (Stone et al., 2019). This study’s qualitative approach was informed by the PEI framework, highlighting the social and political levels of the program’s ecology.

Implementation literature rarely focuses on how policies, systems, and social problems interact with one another in the implementation and sustainment process. The information gathered within this study is unique because it probes how external factors (e.g., race and ethnicity, disproportionality, mental health stigma, along with legislative, professional discipline, and educational policies) are perceived to affect the program’s implementation and sustainability. Further, it addresses various policy levers that policymakers can utilize during planning to enhance systemic adoption and utilization of a new intervention, workforce development program, or policy change. Using qualitative methods, CEMIG as a platform for inquiry, and the PEI framework in combination allows for insight into how race, culture, and systematic biases are experienced within the implementation process.

Methods

A case study design was used to highlight how race, ethnicity, and systematic bias are experienced within the implementation process. This design allows for in-depth, comprehensive, and systematic investigation of social and political factors from the perspectives of key stakeholders during the CEMIG implementation (Yin, 2014). Case studies are used to examine sustainability and implementation factors within public health programs (Scheirer & Dearing, 2011) and how a phenomenon occurs within a real-life context (Baskarada, 2014; Yin, 2014). Multiple data sources were used in this case study to facilitate triangulation (Palinkas et al., 2015).

Study Context

By the end of the 1990s, Minnesota was shifting from mental health services that were grant-funded and contracted to those that were reimbursed via health insurance. This switch required infrastructure changes at many levels: promoting mental health licensure, increasing the number of individuals on health insurance throughout the state, and revising psychotherapy regulations to standardize services. Although these processes were undertaken for the whole state, the effects of trauma in various ethnic communities (e.g., the school shooting in the Red Lake Nation, young Somali immigrants returning to Africa to join Al Shabaab, multiple police shootings, and a second wave of Hmong refugees who had spent more than 20 years living in camps in Thailand) highlighted the need to target specific efforts within the cultural and ethnic minority populations in Minnesota. It was in this vein that the CEMIG program was added to the broader 2007 Governor’s Mental Health Initiative, which aims to increase access, quality, and positive health outcomes of mental health services across the state (DHS, 2006).

The CEMIG legislation (Minnesota Session Laws, 2007) funds a combined mission: to both increase the number of mental health practitioners and professionals from cultural and ethnic minority communities and require that grant recipients meet third-party insurance billing practices. From the PEI Framework perspective, DHS (state government context) implemented legislation (political context) by funding mental health provider agencies (agency context) to supervise, train, and financially support licensure activities for clinical trainees of color (clinical trainee context), including but not limited to clinical supervision, mental health services, EBP training and implementation, and licensure support services (e.g., paying for preparation courses, licensure fees, and exam fees). The 2- to 5-year agency contracts varied widely by the agency in amount, allowable expenses, and outcome reporting requirements.

From 2008 through 2016, the CEMIG program contracted with 21 agencies and allocated $8.86 million to support the training of 281 clinical trainees from cultural and ethnic minority backgrounds (Aby, 2018). Grants covered a wide range of activities (e.g., supervision, paying licensure fees, direct and ancillary mental health services, EBP trainings), which changed during each grant cycle (2–5 years) based on DHS administration priorities (Aby, 2018). CEMIG had 9 different DHS administrators over the 10 years of implementation and each administration required different outcome measures from subcontractors (Aby, 2018).

Sample and Data Collection

The CEMIG program was selected as a critical case (Cresswell, 2014; Palinkas et al., 2015) to demonstrate issues of race and ethnicity within a large-scale, systemwide implementation project. Critical cases are information rich and can generate knowledge development (Patton, 2002); items that are observed in this case can occur in similar settings, (e.g., other large-scale, systemwide implementation programs) which lends itself to demonstrating a potential pattern (Palinkas et al., 2105). For this case study, the data sources are varied to develop ideas of replication and convergence (Gilgun, 1994; Palinkas et al., 2015).

Data sources are a mixture of documents and interview transcripts. All available CEMIG documents were collected from DHS archives in the summer of 2017; the more than 1,000 documents include requests for proposals (RFPs), RFP responses, grant contracts, grant renewal proposals, grantee reporting data submitted to DHS, and proposed and reported budget information. Twenty-eight (N=28) key informants were interviewed for this case study, yielding 22 interview transcripts; multiple interviews included several participants and one interview was located in a poor audio setting and although no recording was collected, copious simultaneous notes were taken. Participant recruitment took place in two phases, fall 2017 and summer 2018. Current and former DHS grant program administrators, agency grant managers (e.g., agency directors and supervisors), Minnesota behavioral health board representatives, university professors, and cultural community professional advocates were contacted to participate in the implementation study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sampling Table and Participant Demographics

| Participant Demographics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | DHS Administrator | Agency Grant Manager | University Educator | Advocacy Group Representative | Government Representative (including Boards) |

| African or African | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| American | |||||

| European | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| American Native | 1 | ||||

| American Latino | 2 | ||||

| Asian American | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

One participant held both an advocacy group representative role and another role in the process

Forty-two potential participants were contacted via workplace email or social media (LinkedIn or Facebook) messaging services. When possible, follow-up phone calls to solicit study participation were made a week after the initial invitation email. While no one directly declined participation, at least half of the contacted potential participants did not respond to the request. Interviews were scheduled at the time of the participants’ choosing, with several occurring over the telephone due to geographic limitations of the researcher. Original recruitment resulted in 22 participants in 17 interview sessions (two grant-making agency interviews included multiple participants). Two board representatives, 13 grant managers, and 7 DHS administrators participated in the interviews. Five of the individuals interviewed had been clinical trainees within the grant program in addition to their status as a grant manager or DHS administrator. Theoretical purposive sampling for the second phase of interviews was conducted through an inductively derived process to explore themes generated during the secondary data analysis process necessary to answer these research questions (Padgett, 2008). Six additional interviews exploring social and political contexts surrounding the CEMIG implementation were conducted in late summer 2018. This group of participants included DHS management, a representative from the Minnesota governor’s office, an agency grant manager, three graduate education professors, and a cultural community professional advocate (Table 2).

Table 2.

Job Roles

| Personnel | Function | |

|---|---|---|

| DHS Administrator | Mental health division staff, employed by DHS | Administered, monitored, or supervised CEMIG grant activity |

| Agency Grant Manager | Supervisors and contract managers from agencies that received CEMIG grant contracts | Monitored agency contracts, collected data for DHS, developed and implemented CEMIG programming at the agency level |

| University Educator | Current or former professors within graduate clinical training programs | Teach and conduct research within graduate programs within Minnesota |

| Advocacy Group Representative | Representative of an advocacy group | To promote the interests and grow the workforce of mental health clinicians of color |

| Government Representative (including Boards) | Government employees within the administrative branch of the state | To enforce and regulate mental health board statutes, or to provide political consult to the governor’s office |

Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes. Each participant signed an informed consent form before the interview. The interviews were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed, and then checked for accuracy by the author. The transcripts were indexed with the grant documents within Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2018) and coded within that system. The interview questions were based on implementation literature (Aarons et al., 2011; Raghavan et al., 2008) and focused on the implementation and delivery of the CEMIG program (Table 3). For the second phase of interviewing, additional theoretical purposive sampling (Padgett, 2008) was conducted, along with further development of the interview guide. This additional step allowed for inductive, analytic expansion (Padgett, 2008) to follow themes developed in the initial round of coding and analysis. The Human Subjects Division within the University of Washington determined this study did not meet the federal criteria for research and thus did not require an Institutional Review Board review.

Table 3.

Sample Interview Questions

| Sample Interview Questions | What were the environmental factors that influenced the implementation process (e.g., state and federal policies, inter-agency collaboration, and other funding influences)? |

| What were the other system changing initiatives occurring at the time of your grant proposal and implementation (e.g., Great Recession, ACA, Medicaid changes)? | |

| Are you aware of other initiatives in the State that are working towards increasing the number of mental health professionals from cultural and ethnic minorities? | |

| What might be other policies that contribute to an individual’s ability to get a license? Have there been any substantial changes in the past 10 years to those requirements that could influence licensure obtainment? | |

| Please describe conversations you have engaged in as an advocacy organization surrounding the licensure application and exam process. | |

| What do you consider to be the barriers clinicians of color experience in the licensure process? |

Data Analysis

This paper incorporates interview transcripts and grant document analysis including the RFP responses, progress statements, and proposals to extend funding that highlight implementation processes and infrastructure development throughout the grant period. The first cycle of coding included provisional and process methods simultaneously (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014; Saldaña, 2016). The case study data were coded using provisional codes (Miles et al., 2014; Saldaña, 2016) that were taken from the PEI framework (Raghavan et al., 2008). Also, the transcripts and study documents were coded using the process method of coding (Miles et al., 2014; Saldaña, 2016). Process coding allows the researcher to document the action and actual experiences of the participants that contribute to routines and consequences for behavior (Saldaña, 2016). Provisional and process coding during the first cycle of coding separated actions and experiences into ecological levels of the PEI. After the first cycle of coding, code mapping was used to reorganize the codes into categories and condense them into central themes or concepts (Miles et al., 2014; Saldaña, 2016). The second cycle of coding used pattern coding, which allowed for explanatory or inferential codes that arose and generated emergent themes (Miles et al., 2014; Saldaña, 2016).

To enhance and secure credibility, transferability, auditability, and confirmability the following steps were taken: peer debriefing, memoing, negative case analysis, data triangulation, and member checking, which contributed to the rigor of this study (Morse, 2015). Peer debriefing, as well as consultation with a supervisory committee (Wu, Wyant, & Fraser, 2016), assisted in thinking through research strategies and theme generation. Memoing throughout the process created an audit trail of analytical steps and processes utilized to collect and analyze data and afforded the opportunity to be reflective about positionality and bias and how that might have influenced the data collection and analysis (Gilgun, 2015; Wu et al., 2016). Negative case analysis, the process of actively searching for information that contributes to or contradicts the developing analysis, was used during the theory-building process to expand the original theoretical framework (Gilgun, 2015); in this process, concepts were tested, discussed with the supervisory committee, and the veracity of the emerging analysis was checked against the provisional codes and theoretical framework (Gilgun, 2015). Data triangulation was employed throughout the process (Wu et al., 2016). The additional theoretical sampling allowed for member checking and theme generation (Wu et al., 2016).

Findings

In this study, the analysis identified several social and political system factors (e.g., siloed systems, experiences of racism, and cultural bias) that influenced and created barriers in the CEMIG implementation process. The themes derived from the analysis, invisibility, isolation, and inequity, help to illuminate how social and political factors influenced the implementation process. Further descriptions of the themes along with quotations from participants are in the following section. Some of the participants’ words were modified to enhance readability by eliminating repeated phrases, qualifiers such as “you know,” and habitual phrases such as “um” or “like.” Because many of the participants are first-generation immigrants, slight modifications have occasionally been made to adhere to English grammar and disguise dialects.

Invisibility

The theme invisibility points to how the struggles of clinical trainees of color were unrecognized, the program was unknown in the community, and the outcomes of CEMIG were untallied. While there was little awareness of the CEMIG program amongst non-program participants (e.g., graduate program faculty, advocacy group representatives, and mental health board representatives), all participants acknowledged that there were not enough mental health professionals from cultural and minority groups in the state and that there were substantial social and political barriers to decreasing the disparate representation of people of color in the mental health professions.

The first marker of invisibility was the clinical trainees themselves. Concerning the number of clinical trainees of color and their experience in the licensure process, the boards repeatedly stated that “85 to 90% of all of our licensees report being Caucasian” and that “it is still a very highly dominated Caucasian profession in Minnesota, so this topic of conversation [racial bias in the licensure process]…is usually in response to conversation happening elsewhere.” Additionally, the exams are run by national organizations that either do not request demographic data of the applicants or do not share that information with the state board. The licensure system does not ask for racial and ethnic information, making it possible for disparities to remain unknown.

Further, graduate training programs stated that they were not informed by their graduates of color about difficulties passing the exams. One social work program professor stated that although their program does not keep track of the passing rates, “we are able to, the only feedback we get is we can call [the Association for Social Work Boards] and ask for our pass rates for our school.” Another university professor discussed how there used to be a survey that followed graduates to learn about jobs, salary information, and licensure, but this ended years ago. Neither the boards nor the graduate training programs were following success and failure in the licensure process by race, nor were they made aware of programs in the community designed for clinical trainees of color by DHS. The lack of communication created a system of invisibility where both cultural and ethnic minority clinicians issues and supports were hidden.

The second major issue was that individuals within the universities, mental health boards, governor’s office, and advocacy organizations had either not heard about the CEMIG program or had only tangential involvement in years past. While sometimes participants from universities or advocacy groups knew about an individual grant agency’s program, especially those focused on interns within graduate training programs, they were unaware of the larger DHS program. Last, a few agency grant managers lamented that the CEMIG program was not better advertised or promoted by DHS:

…I wish that the grant was probably a little more well known in the community or who are the recipients of these grants and if they’re doing something that other organizations can participate in or learn more about it. I feel like maybe sometimes grantees have these grants and they’re doing things that are specific for their organization but we don’t really know what these outcomes are.

With the lack of program visibility, it was difficult for agencies to share what they had learned with each other and create a learning community. DHS granted dollars to agencies to develop programs but did not share that information with the greater community. The CEMIG program was not a secret for DHS, nor was it a primary area of focus. There was no information on the DHS website about CEMIG. There were limited group meetings amongst CEMIG grantees. These practices were in stark contrast to early childhood mental health and EBP training programs that were also a part of the 2007 Governor’s Mental Health Initiative. The lack of program visibility allowed for pockets of innovation without a public discussion of the grant or the problem the grant was trying to fix. While social factors such as racism and hidden bias were not identified by participants as the reasons that kept DHS quiet about the grant program, there was an acknowledgment that the lack of conversation kept the program from being promoted at the legislature, with the mental health boards, and in the provider community.

The last marker of invisibility is with the grant outcomes themselves. Nine DHS employees administered this grant program over the 10-year grant period. Each grant manager created their own data reporting requirements: narrative, surveys, service counts, and individual psychometric data. During data collection, substantial effort was taken to retrieve items on personal DHS servers for employees who had changed positions or to comb through shared server folders. DHS’s accounting system changed during this grant program period, making it impossible to get the earliest financial data. During grant program administration, grantees started emailing their grant administrator with outcome reports, invoices, and program renewal requests. There was no standard practice or expectation for how grant administrators would transfer information from individual email accounts to shared servers or grant management accounts.

CEMIG’s invisibility as a grant program in the state paralleled the invisibility of clinical trainees of color in the mental health professional licensure system. It is unclear if the grant program was muted because the financial allocation was dwarfed by other initiatives, the high amount of turnover in DHS administrators, or the elusiveness of the program’s mission. In the end, CEMIG was overlooked, much like the 10–15% of applicants of color to the behavioral health boards.

Isolation

Participants expressed feelings of isolation between the grant program, DHS, mental health boards, the mental health community, and graduate training programs. This isolation manifested in conversations of professional roles and lack of collaboration. Within this policy ecology, each system within the state government and political contexts seemed to be self-contained. The mental health boards, DHS, graduate training programs, state workforce initiatives all function within their individual sphere of influence and have unique roles.

For instance, mental health boards firmly believe their primary purpose is to protect the public as a regulatory body and while others are emphatic that the boards could take a leading role in changing mental health professional demographics, a DHS administrator stated that she witnessed a board representative question during a meeting:

“…well, where’s the proof that our tests aren’t culturally competent?” … the fact that you don’t even keep demographics, like isn’t that convenient that you don’t even keep demographics to be able to show who’s passing your tests and who’s not? … what blows my mind is how closed they are to looking at their role in what they could be doing differently to try to address this.

However, mental health board representatives, focusing on public protections and their legislative mandate, are hesitant to engage in outside conversations about barriers and disparities in the licensure process, especially those pertaining to reducing requirements. For instance, one representative expressed:

I think regulatory entities really have to be cautious, and I think, there’s the risk of, when you’re looking at barriers to address concerns, if you reduce standards on the face of it, I think that has the potential to open up risks, and so, there has to be a real strategy and there has to be real sound rationale.

The separation between the mental health board view of their role and the DHS Administrator’s view is stark. The isolated work between the two systems keeps conversations about public protections and a lack of diversity within the mental health workforce as being two separate issues, rather than aspects of the same problem.

Additionally, even though there are areas of overlap between graduate training and mental health boards (e.g., professors teach students who will take board exams or social work professors are required to be licensed in the state of Minnesota), there is a lack of coordination between the two entities. Besides not being aware of licensure rates after graduation, there is isolation between educational training and demonstration of competence within the licensure process; a graduate professor explained how their role is to:

…prepare [students] for the lessons and exam [but] I think even our own professors are removed from that exam process. No one really knows what is in the exam unless you order an exam sample booklet and you look through the questions or you’re an exam writer. Things like that. Our professors are not involved at that level. We don’t specifically prepare students for the exam. But we do have workshops, seminars, and information sessions about the licensing process.

While the student or licensure applicant may see education and licensure as components of the same process, the systems that are in charge of each step are separate and isolated from each other. Instead of strategically targeting interventions to assist each silo in this process to better attend to clinical trainees from cultural and ethnic minority groups, CEMIG funded mental health agencies to retroactively fill in the gaps. The legislative and institutional norms within the education and mental health licensure system that perpetuated the current siloed system influenced CEMIG implementation and placed an undue burden on the grantee agency to retroactively fix knowledge gaps.

These feelings of isolation prompted both the boards and the agency grant managers to call for cross-system collaboration. A mental health board representative emphasized that a one-size-fits-all solution, like a grant program, could not make a substantial difference in changing the demographics of the workforce:

…it really has to be a statewide, a systems, a regulatory professional… all the pieces of the system have a potential opportunity and responsibility to shore it all up… it’s got to be a multifaceted approach, and it’s not just the examination.

Noting issues of long perpetuated disparities, participants voiced concern that interceding at the point of licensure application was insufficient to change the effects of poverty and racism that often translated to difficulty with exams and access to employment and mentoring opportunities. Taking a more grant-specific focus, the agency grant managers, looked more to DHS to provide leadership to dismantle the isolating systems. Charging DHS with ownership of the grant program and grant data, this agency grant manager chastised DHS with the consequences of not coordinating between systems to create change:

DHS is sitting in the middle between the boards and the clinical training sites… If DHS has the data that says, even with all of this, even with people getting trained as well as we possibly get them trained, something seems to be happening at the board side of things.… [DHS] has the ability to go to the boards and say—on a policy side not an advocacy side—is there anything we can do to make the whole system work better?

By focusing on the agency context level alone, DHS perpetuated the self-contained systems. Without an organization to coordinate between the multiple systems within this policy ecology, the graduate programs, mental health boards, and DHS were able to continue business as usual that perpetuated the knowledge gaps in both education and issues of systemic racism within the field. The grant managers continued their plea to have a louder voice speaking to the separate ecosystems. One grant manager explained:

I think that in order to be more successful, [DHS] needs to be able to work with the licensing board. Having some kind of strategies or support from the state, whether it is to the Department of Behavioral Health to have a louder voice as a community, to provide—to advocate for our participants…to be able to have a voice in talking about some of these challenges out there.

The lack of a unifying cross-system voice, according to the grant managers, limited the effects of their post-graduate clinical training programs. There was considerable frustration that clinical training sites were being tasked with shouldering the burden of teaching concepts that were not covered during graduate training, such as test taking skills, how to navigate culturally-based ethics questions, and English fluency. Grantee agencies were seeking a policy voice to challenge the systemic issues, feeling hopeless because small grants of $50,000 to $100,000 were not sufficient to attenuate years of disparities and bias.

Each aspect of the state government had socially sanctioned roles for monitoring the process by which individuals learn, practice, and competently provide mental health services which perpetuated racial disparities and a lack of accountability. As no particular level or context was uniquely responsible for the disparate rate of licensure for clinicians of color, trends were missed. Lastly, the grant focus on the agency context highlighted the disproportionate allocation of responsibility to the supervising agency creating feelings of isolation amongst grantees.

Inequity

Along with issues of invisibility and isolation, concepts of inequity materialized during the interviews and grant documents. Participants described inequity in workforce development programs, in the licensure exam process, and within the mental health community. From feeling tokenized to unwelcome, participants, especially agency grant managers and advocacy group representatives, described an unfriendly environment for mental health professionals of color.

During the grant period, there were many workforce development initiatives, sponsored by the federal and state governments that attempted to address the shortage in the mental health workforce overall. Loan forgiveness was a primary topic of conversation in the legislature and committee meetings. It was also mentioned that issues of people of color were never the focus of the workforce initiatives but instead were popular add-ons to the more significant issue, an issue that might be addressed when there were more legislators of color or political support.

The loan forgiveness programs were also seen as a shining star that could help all individuals, regardless of race or ethnicity, on the path toward mental health licensure. One individual explained, “[this] was one of the most exciting investments that the legislature and the state put forward to really put some money out there to make a difference.” These programs are run through the MDH and often sought board representatives to serve as reviewers; there was broad community support for the task forces to support these programs. The task forces were able to increase the eligible licensure type of mental health professionals (expanding beyond psychologists and psychiatrists) but were not able to increase the total number of individuals who could participate within the state; as recounted by the governor’s office representative:

…loan forgiveness, that costs money. I think some of the loan forgiveness stuff that expanded to social workers was in there, and they didn’t put more money towards it; they just added another profession to the pool, which is budget neutral but expands the number of people in the pool. So, things like that. And fewer dollars available.

Although the Mental Health Summit called for 50% of the increase of loan forgiveness funds to go to clinicians of color, this ignored that most of the positions are in rural Minnesota, which is predominantely White. Prioritizing clinicians of color, according to an advocacy group representative, is much more needed “because so many practitioners of color don’t have rich parents who can pay for part – or all – of their education, and so they end up with these crazy, massive student loans; they need some way of just living.” The general philosophy on most of the committees, per the governor’s office representative, was that there needed to be “more cultural awareness and sensitivity [when working with] people from different cultural communities,” rather than promoting culturally specific providers, which according to her was perhaps a result of the current demographics of the legislature:

…at the legislature, it’s a bunch of white people. There are very few legislatures of color, and the more left-wing members are more likely to bring it up and try to make sure that legislation is inclusive, but it takes a lot of effort, and it’s not a default. It hasn’t risen to the level where actual real action and more than lip service.

The lack of diversity allowed committees and the legislature to focus on general shortages rather than issues of disparities. Even though, perhaps, the financial needs were more significant for practitioners of color, the hesitancy to add more financial resources and cultural requirements to the loan forgiveness program, perpetuated the inequities within workforce development conversations.

The next inequity discussed by the participants was cultural bias within the exams themselves. Grantee agency representatives, DHS administrators, university professors, and advocacy representatives made statements that flatly asserted that the exams were cultural tests “based on White middle-class culture and White academics.” Conversations with the boards on whether exams could be altered to be more culturally diverse in perspectives were received with great resistance, with responses, as described by an agency grant manager, such as “Well, this is the national test. This is what we’re going with.” Agency managers of all backgrounds described how they were coached by national test exam instructors teach practitioners of color to “think like a White man” to pass the test. Another participant, a university professor, described how her students had been advised to “imagine you’re a 40-year-old White woman from Nebraska,” which is a great challenge to “imagine yourself through a world view that is foreign to you.” The professor pondered: “why are these folks not making it through the licensure process? …It goes back to things like issues around barriers and oppression. Not accommodating for differences. Do it our way.” She furthered posited that if the exam was structured in a more culturally diverse way, it “might actually challenge students from the dominant culture. They might be challenged too, in a good way, to think about these case scenarios in a different way.” While individual agencies created trainings to attend to the cultural bias within the exams, other agencies focused on English language courses or test taking skills. However, there was a sentiment expressed by numerous agency grant managers, that they were being tasked to fix a problem that was beyond their scope and questionable to their morals. Teaching clinicians of color how to “think like a white man” for the sake of an exam, often ran counter to their own values of social justice, even if it was just a means to an end. The foundation of the exams in a White/dominant culture framework, according to the professors, agency grant managers, DHS administrators, and advocacy representatives created a biased test that served as a gatekeeper for individuals who were unable or unwilling to think like a White person during the exam period.

The issues of inequities were also reported at the clinical trainee level as well. An advocacy group representative described how when he entered the profession “people were not inviting.… [I]t was an awful experience, because you were treated like you shouldn’t be there, and you didn’t enjoy it.” Although according to him, this has evolved, the memories of having “White people, who would laugh [when] I would come out in the waiting room.… I would have White professionals who would refuse to see me” parallel with current examples of clinicians being rejected for being Muslims. Further, an African American grantee representative described her experience of a role play during a trauma focused EBP training as Eurocentric:

So, the white clinician who was supervising our training and trying to play the therapist, she says, “Well, you shouldn’t be afraid. There are the Police over there.” And, so the little boy said, “I’m afraid of him, too.” So, that’s what we are finding in the culture-based models – I mean, the lack of culture-based models and the evidence-based models, that there’s a lack of knowledge and a big gap between what we need to know as our everyday way and experience and what is being taught to us.

Trainings that discount the experience of both providers and clients of color, forgetting how certain social roles, such as those of the police, immigration officials, or the educational system are not safe or nurturing for individuals from cultural and minority backgrounds. The grantee stated that this was one of many constant reminders of being trained in a “Eurocentric model” that perpetuates the “systemic racism and biases [that] continue to create barriers for us to run the race,” and feel like an unequal member of the mental health community.

While there were efforts to include people of color in larger workforce development programs, the participants described feelings of being add-on’s or tokens rather than the focus. Larger system programs, such as EBP trainings and the licensure exams themselves, were experienced as Eurocentric and culturally biased. These experiences of inequity began with the legislation and continued through their everyday practice.

Discussion

This study adds to the growing literature investigating large-scale, system-wide projects by examining how social and political factors influence and create barriers in the implementation processes (Beidas et al., 2016; Brookmann-Frazee et al., 2016; Nadeem et al., 2016; Olin et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2017; Skriner et al., 2017; Southam-Gerow et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2016). This study’s findings can be useful for both policy makers and implementation researchers. For policymakers, the results herein may assist them in applying this conceptual framework when developing a comprehensive, multifaceted policy intervention. For implementation researchers, this case study may be used to identify community and policy-maker partners while developing implementation plans for EBP models and other clinical intervention techniques.

This study’s findings that (a) invisibility, (b) isolation, and (c) inequity demonstrate that policy levers at one level are insufficient for greater adoption and sustainability. The participants described feeling like the CEMIG program was unknown, isolated from other systems, and perpetuated larger social inequities. As the PEI framework describes (Raghavan et al., 2008), a multisystem approach is needed to implement an initiative successfully. The CEMIG program targeted their policy levers at the agency context level, hoping that it would be sufficient within this workforce development initiative. Often when the PEI framework is invoked, it is to remind policymakers that unfunded mandates are difficult to sustain (Rubin et al., 2016; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2016); this case study demonstrates that money alone is also insufficient. Based on the participants’ experiences, the following policy levers are suggested to enhance implementation within an ecological context (Table 4): enhanced data collection, innovation cross-fertilization, and stakeholder advocacy involvement.

Table 4.

Potential Policy Levers

| Level | Potential policy levers | Barrier addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Agency context |

|

|

| State government context |

|

|

| Political context |

|

|

| Social context |

|

|

Enhanced Data Collection

Unfortunately, due to the lack of data collection by the boards on issues of race and ethnicity, the CEMIG program began with no baseline data. The invisibility of the target problem the grant was trying to alleviate was only heightened with the grant’s difficulty with their data reporting. Because the grant program was targeted at the agency/organizational level, DHS did not have frequent direct communication with the clinical trainees enrolled in the program or throughout the state. Using agencies as a conduit is simpler for grant management but limits feedback from the recipient to the funder of the program. By not communicating directly with the clinical trainees, DHS continues the cycle of not knowing how many times each trainee takes the exam, how much preparation is required, and which strategies are utilized to maximize outcomes. The lack of data, both quantitative and qualitative, forces DHS administrators to use secondhand data from the agency, which hinders DHS from being able to advocate for the clinical trainees with other systems. Future infrastructure programs might therefore include consistent data collection regarding the outcomes and experiences of the recipient. These data can assist in legislative and stakeholder efforts as well as in monitoring contract outcomes and program efficacy (Walker et al., 2019). Hearing directly from the constituent is essential for program management, advocacy, and ongoing funding, especially when working with an invisible population within a colorblind system.

Innovation and Cross-Fertilization

Given that most of DHS’s attention was spent at the agency/organizational level. DHS sought proposals, created contracts, and requested outcome reports from the 21 agencies with which it had contracts. The provider agency level is known as being the central role for implementing policy and EBPs (Aarons et al., 2011; Raghavan et al., 2008; Southam-Gerow et al., 2014) because culture and climate are vital components when working with individual clinicians to change practices (Aarons et al., 2011). However, the provider agency is the least likely level to be able to make the system-wide change, because it is dependent on larger collaborative networks and funding (Aarons et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2016; Raghavan et al., 2008). Within this case study, the provider agencies specifically voiced concern that they were shouldering the burden of ending workforce disparities without enough support from state institutions which added to their isolation. The literature discusses how important it is for agencies to have access to “cross-fertilization” and institutional learning with other providers engaging in similar practices (Aarons et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2016). Although the CEMIG program occasionally had grantee meetings for agencies to come together, learn about DHS requirements, and share success or struggle stories, there was no infrastructure created for agencies to generalize insights (Powell et al., 2016). Other successful large infrastructure programs have found that creating an innovation center or consulting position for the implementation process has helped share ideas and dismantle implementation barriers across provider agencies (Powell et al., 2016). Adding in this infrastructure at the organizational level would assist in institutional learning and create building blocks for provider sustainability (Powell et al., 2016; Raghavan et al., 2008). Further, especially when implementing programming for populations experiencing health or workforce disparities, community building is particularly compelling in addressing hidden biases and systemic barriers (Chin et al., 2012; Crary, 2017).

Stakeholder Advocacy Involvement

At the state regulatory or DHS level, there were many concerns within this case study: lack of advocacy, lack of data management, a lack of creating collaboration and engaging stakeholders. The lack of these activities seems to partly result from the DHS administrator functioning as a grant manager instead of as a consultant/hub of an innovation center as described above. Whereas sustainability for implementation projects requires an institutionalization with funding, contracting, and systems improvement (Aarons et al., 2016; Raghavan et al., 2008), it also requires fostering of ongoing collaborations among different levels of government, advocacy groups, provider agencies, constituents, and related systems (e.g., clinical training programs; Aarons et al., 2016). With DHS focusing on contracting and grant management, there was little time to market to stakeholders (Aarons et al., 2016) or create a stakeholder advisory council (Starin et al., 2014), both of which have been shown to enhance program sustainability and success. Without marketing or stakeholder engagement, the clinical training programs, mental health boards, and advocacy programs—all key institutions that could support legislative and policy work—were unaware of the CEMIG program. The grant program existed in isolation that prohibited collaborative efforts and buy-in from key stakeholders. Future infrastructure development programs might therefore expand the role of the governmental administrator to include community engagement with stakeholders and provider agencies to create institutionalized learning and promote cross-system connections. This is particularly important for programming addressing complex social issues that contribute to racial, as strong leadership is needed to help systems uncover and attend to hidden biases and structural racism disparities (Wangari Walter et al., 2017).

As noted above, the difficulty of the CEMIG program was the lack of exposure to the mental health boards, clinical training programs, and even mental health provider advocacy groups. At the political level, this isolated grantee agencies and clinical trainees from potential strategic partners because there was a lack of understanding that clinical trainees of color were having trouble passing licensure exams. With the mental health boards not recognizing this as an issue and the governor’s office not conducting oversight of the boards, the invisibility of the grant program and the needs of the clinical trainees continued. Beyond the lack of communication with the state mental health boards, there was minimal interaction among the grant program, the mental health workforce initiative, and tuition forgiveness programs run through MDH. Here again, having a stakeholder advisory council (Starin et al., 2014) and fostering ongoing collaboration among levels of government, advocacy groups, clinical training programs, and provider agencies (Aarons et al., 2016; Raghavan et al., 2008) would have been beneficial to help push for simple policy changes that could lead to greater change, such as requiring mental health boards to keep demographic data of applicants and licensed clinicians. This stakeholder body could also serve as a conduit for collaborative practices among the systems and help the potential for discriminatory practices toward clinicians of color to become a first-tier issue and focus of system-wide policy change.

Last, at the social level of the PEI framework, it is essential to look at how stigma and racial disparities interact with implementation. There were multiple ways that the participants voiced the effects of stigma and racial disparities, in both the lives of the clinical trainees and mental health professionals of color but also in the lack of visibility of the program itself. As discussed by both representatives from culturally specific mental health professional development/advocacy organizations, they had not been included in the development, outreach, or implementation of the CEMIG program. There are at least four or five state-based, culturally specific, mental health professional development organizations that could be included in the stakeholder advisory council to disperse the information gained from the grantee agency programs and reach a broader base of cultural and ethnic minority clinical trainees. These mental health professional development organizations include pipeline programming to foster interest in the profession, academic and career mentoring, and professional learning communities (Moua, Vang, & Yang, in press). Given that these organizations are engaging in similar processes within specific cultural communities, they would be essential voices to include in more substantial policy discussions and a fundamental way to transition the issue of barriers to licensure for clinicians of color to the forefront.

These findings demonstrate that the implementation of any policy or intervention requires an ecological approach. Several areas are identified that would promote success for the CEMIG program and other similar large-scale implementation programs: including consistent data collection methods that explore financial, historical, and logistical experiences in the licensing process; creating an innovation center that allows for cross-fertilization and technical assistance for provider agencies; crafting legislation that requires mental health boards to collect demographic data on applicants; and developing a multisystem stakeholder advisory council that includes multiple state agencies, culturally specific professional development organizations, grantee agencies, clinical trainees, and the innovation center. External issues such as disparities, racial bias, mental health stigma, competing or complementary programs, and other regulatory bodies affect and create the experience of implementation in a way that can perpetuate greater social problems, such as systemic racism. Adding these policy levers to large-scale implementation projects is important because creating policy at only one level of the PEI framework impedes implementation and sustainability (Raghavan et al., 2008).

Limitations

The information for this study is limited to the perspectives of key stakeholders in one state with one infrastructure program. Implementation methods used in this case study are unique to this type of infrastructure development program and may not be as applicable to other statewide policy programs. Participant recruitment, though ethnically diverse, was not all-inclusive, and there were limits due to time frame, retirements, and availability. My being a former DHS administrator might have skewed some of the responses, either by participants assuming I understood peripheral facts or by previous relationships inhibiting responses. These items may limit generalizability; however, the descriptive results given here correspond with information provided in other large-scale implementation programs (Aarons et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2016) and demonstrate the need for examining the role of race and ethnicity in implementation literature. Further research is warranted to describe differences in implementation based on culture and ethnicity within mental health settings, as well as examining institutional norms, such as licensing exams that clinicians of color may experience in discriminatory ways.

Conclusion

This study adds to the literature in two primary ways by addressing underlying social (e.g., race and ethnicity, disproportionality, and stigma) and political (e.g., legislative, professional discipline, and educational policies) factors that influence and create barriers to the implementation of large-scale, system-wide policy initiatives. There are several tangible strategies that future large-scale, system-wide implementation projects could use to address potential social and political context barriers. Beyond having baseline data at the beginning of the implementation project, there needs to be a secure, on-going plan for collecting outcome and demographic data during the lifetime of the project. Future infrastructure development programs might, therefore, expand the role of the governmental administrator to include community engagement with stakeholders and provider agencies to create institutionalized learning and promote cross-system connections. This is particularly important for programming addressing complex social issues that contribute to racial inequities, as strong leadership is needed to help systems uncover and attend to hidden biases and structural racism disparities (Wangari Walter et al., 2017). If the governmental administrator cannot accomplish this role, the technical assistance and cross-fertilization functions could be attended to through a private, separately funded innovation center (Powell et al., 2016). Last, future large-scale, system-wide implementation projects could create stakeholder advisory boards that cross systems and contain a variety of perspectives, including but not limited to: consumer groups, cultural and minority clinician advocacy groups, other state departments, graduate training programs, provider agencies, and mental health board representatives.

Increasing the number of mental professionals from cultural and ethnic minorities will continue to be of high importance in the coming years. The Department of Health and Human Services (2016) projects that there will be shortfalls for psychologists, clinical social workers, and marriage and family therapists by 2025. Addressing issues of disparities within the licensure process is of crucial importance for both states and professional disciplines, especially for social work that holds social justice as a critical ethical principle (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], n.d.). Using the PEI lens, it was found that efforts to implement a culturally-focused workforce development initiative largely failed due to issues of invisibility, isolation and inequity; it is crucial for policy makers to include race and ethnicity as factors within the political and social contexts when implementing large-scale, system-wide programs.

Funding:

Minnesota’s DHS funded data collection, and data analysis was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1TR000422. The methods, observations, and interpretations put forth in this article do not necessarily represent those of the funding agency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: I do not have any conflicts of interest

Ethical approval: The Human Subjects Division within the University of Washington declined oversight of this study, stating that it did not meet the federal definition of research.

Informed consent: All participants were informed of their rights prior to consenting to participate in this study.

References

- Aarons G, Green A, Trott E, Williging C, Torres E, Ehrhart M, & Roesch S (2016). The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-method study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 991–1008. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0751-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aby MJ (2018). All over the map: A case study of Minnesota’s Cultural and Ethnic Minority Infrastructure Grant. St. Paul, MN: Department of Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Baskarada S (2014). Qualitative case study guidelines. The Qualitative Report, 19(24), 1–18. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2559424 [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R, Stewart R, Adams D, Fernandez T, Lustbader S, Powell B,…Barg F (2016) A multi-level examination of stakeholder perspectives of implementation of evidence-based practices in a large urban publicly-funded mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 893–908. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0705-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Stadnick N, Roesch S, Regan J, Barnett M, Bando L,…Lau A (2016). Measuring sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 1009–1022. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0731-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin M, Clarke A, Noncon R, Casey A, Goddu A, Keesecker N, & Cook S (2012). A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(8), 992–1000. 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary M (2017). Working from dominant identity positions: Reflections from “Diversity-Aware” white people about their cross-race work relationships. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(2), 290–316. doi. 10.1177/0021886317702607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). National projections of supply and demand for selected behavioral health practitioners: 2013–2025. Retrieved from https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5063776-National-Projections-of-Supply-and-Demand-for.html

- Department of Human Services (DHS). (2006). Governor’s Mental Health Initiative: Questions and Answers. Retrieved from http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/disabilities/documents/pub/dhs_id_056863~4.pdf

- Ford C, & Airhihenbuwa C (2010). Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: Toward Antiracism Praxis. American Journal of Public Health, 100(S1), S30–S35. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilgun J (1994). A case for case studies in social work research. Social Work, 39(4), 371–380. 10.1093/sw/39.4.371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilgun J (2015). Beyond description to interpretation and theory in qualitative social work research. Qualitative Social Work, 14, 741–752. 10.1177/1473325015606513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Healthforce Minnesota. (2015a). Gearing Up for Action: Mental Health Workforce Plan for Minnesota: Report to the Minnesota Legislature. Executive Summary. Retrieved from https://www.lcc.leg.mn/lhcwc/meetings/161004/Exectuive%20Summary%20Finalweb.pdf

- Healthforce Minnesota. (2015b). Gearing Up for Action: Mental Health Workforce Plan for Minnesota: Report to the Minnesota Legislature. Retrieved from http://stmedia.startribune.com/documents/Mental+Health+Workforce+Plan.pdf

- Miles M, Huberman AM, & Saldaña J (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Session Laws. (2007). Chapter 147, Article 8, Section 8. Retrieved from Minnesota Legislature website, Office of the Revisor of Statutes: https://www.revisor.mn.gov/laws/?id=147&year=2007

- Morse J (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. doi: 10.1177/1049732315588501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moua KN, Vang PD, & Yang MA (unpublished). The Minnesota Hmong Social Workers’ Coalition: A model for recruiting, supporting, and mentoring Hmong social work students, professionals, and community leaders.

- Nadeem E, Weiss D, Olin SS, Hoagwood K, & Horwitz S (2016). Using a theory-guided learning collaborative model to improve implementation of EBPs in a state children’s mental health system: A pilot study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 978–990. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0735-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (n.d.). Code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

- Olin SS, Nadeem E, Gleacher A, Weaver J, Weiss D, Hoagwood K, & Horwitz SM (2016). What predicts clinician dropout from state-sponsored managing and adapting practice training. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 945–956. doi: 10.1004/s10488-015-0709-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D (2008). Qualitative methods in social work research. New York, NY: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz S, Green C, Wisdom J, Duan N, & Hoagwood K (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Mandell D, Hadley T, Rubin R, Evans A, Hurford M, & Beidas R (2017). Are general and strategic measures of organizational content and leadership associated with knowledge and attitudes toward evidence-based practices in public behavioral health settings? A cross-sectional observational study. Implementation Science, 12(64), 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0593-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Powell BJ, & McMillen JC (2013). Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science, 8(139), 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan R, Bright CL, & Shadoin A (2008). Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence-based practices in public mental health settings. Implementation Science, 3, 26. doi: 10.1186/748-5908-3-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R, Hurford M, Hadley T, Matlin S, Weaver S, & Evans A (2016). Synchronizing watches: The challenge of aligning implementation science and public systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0759-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MA, & Dearing J (2011). An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 101(11), 2059–2067. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skriner L, Wolk CB, Adams D, Rubin R, Evans A, & Beidas R (2017). Therapist and organizational factors associated with participation in evidence-based practice initiatives in a large urban publicly-funded mental health system. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 45, 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s11414-017-9552-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So M, McCord R, & Kaminski J (2019). Policy levers to promote access to and utilization of children’s mental health services: a systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. Online. 10.1007/s10488-018-00916-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants. (2018). Dedoose Version 8.0.35, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow M, Daleiden E, Chorpita B, Bae C, Mitchell C, Faye M, & Alba M (2014). MAPping Los Angeles county: Taking an evidence-informed model of mental health care to scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 190–200. 10.1080/15374416.2013.833098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stake R (2005). Multiple case study analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stone EM, Daumit G, Kennedy-Hendricks A, & McGinty E (2019). The policy ecology of behavioral health homes: Case study of Maryland’s Medicaid health home program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. Online. doi: 10.1007/s10488-019-00973-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starin A, Atkins M, Wehrmann K, Mehta T, Hesson-McInnis M, Marinez-Lora A, & Mehlinger R (2014). Moving science into state child and adolescent mental health systems: Illinois’ evidence-informed practice initiative. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 169–178. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.848772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Adams D, Mandell G, Nangia G, Shaffer L, Evans A, …Beidas R (2017). Non-participants in policy efforts to promote evidence-based practices in a large behavioral health system. Implementation Science, 12(70), 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0598-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Hurvitz P, Leith J, Rodriguez F, & Endler G (2016). Evidence-based program service deserts: A geographic information systems (GIS) approach to identifying service gaps for state-level implementation planning. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43, 850–860. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0743-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Sedlar G, Berliner L, Rodriguez F, Davis P, Johnson S, & Leith J (2019). Advancing the state-level tracking of evidence-based practices: a case study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. Online. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0280-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SC, Whitener R, Trupin EW & Migliarini M (2015). American Indian perspectives on evidence-based practice implementation: Results from a statewide tribal mental health gathering, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(1), 29–39. 10.1007/s10488-013-0530-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangari Walter A, Ruiz Y, Tourse R, Kress H, Morningstar B, MacArthur B, & Daniels A (2017). Leadership matters: How hidden biases perpetuate institutional racism in organizations. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership, & Governance, 41(3), 213–221. doi. 10.1080/23303131.2016.1249584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willging CE, Goodkind J, Lamphere L, Saul G, Fluder S, & Seanez P (2012). The impact of state behavioral health reform on Native American individuals, families, and communities. Qualitative Health Research, 22(7), 880–896. doi: 10.1177/1049732312440329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltsey Stirman S, Gutner C, Langdon K, & Graham J (2016). Bridging the gap between research and practice in mental health service settings: An overview of developments in implementation theory and research. Behavior Therapy, 47, 920–936. 10.1016/j.beth.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Wyant D, & Fraser M (2016). Author guidelines for manuscripts reporting on qualitative research. Journal for the Society of Social Work & Research, 7(2), 405–425. doi: 2334-2315/2016/0702-0012 [Google Scholar]

- Yin R (2014). Case study research design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]