Abstract

Sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) crop is vulnerable to many abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, waterlogging, cold and high temperature due to climate change. Over the past few decades new breeding and genomic approaches have been used to enhance the genotypic performance under abiotic stress conditions. In sugarcane, introgression of genes from wild species and allied genera for abiotic stress tolerance traits plays a significant role in the development of several stress-tolerant varieties. Moreover, the genomics and transcriptomics approaches have helped to elucidate the key genes/TFs and pathways involved in abiotic stress tolerance in sugarcane. Several novel miRNAs families /proteins or regulatory elements that are responsible for drought, salinity, and cold tolerance have been identified through high-throughput sequencing. The existing sugarcane monoploid genome sequence information opens new gateways and opportunities for researchers to improve the desired traits through efficient genome editing tools, such as the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-Cas (CRISPR/Cas) system. TALEN mediated mutations in a highly conserved region of the caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) of sugarcane significantly reduces the lignin content in the cell wall which is amenable for biofuel production from lignocellulosic biomass. In this review, we focus on current breeding with genomic approaches and their substantial role in enhancing cane production under the abiotic stress conditions, which is expected to provide new insights to plant breeders and biotechnologists to modify their strategy in developing stress-tolerant sugarcane varieties, which can highlight the future demand of cane, bio-energy, and viability of sugar industries.

Keywords: Abiotic stresses, Sugarcane, Genomic strategies, microRNA and genome editing

Introduction

Sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) is one of the most important industrial crops across the world, which is predominantly grown for sugar and bioenergy in both tropical and sub-tropical regions. It occupies over 24.9 million hectares of area over 80 countries worldwide with a production capacity of 174 million tons (OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2019–2028). Global sugar demand is estimated to grow to 255 million tons from the present level of 174 million tons, as the population is expected to cross over 9 billion by 2050 (FAO 2017). India, Brazil, the EU, Thailand, China, USA, Pakistan, Russia, Mexico, and Australia are the major sugar-producing countries, accounting for nearly 70% of the global output. While, India, the EU, China, Brazil, USA, Indonesia, Russia, Pakistan, Mexico, and Egypt are major sugar-consuming markets. As per International Sugar Organization (ISO) estimates, India overtook Brazil and became the largest producer of the sugar in the world with 33.30 million tons (2018–19) as compared to Brazil’s 29.29 million tons (www.isosugar.org/sugarsector/sugar). India has added 10 million tons of surplus sugar in addition to the domestic consumption of 25 million tons as per the Indian Sugar Mills Association estimate, 2018–19. The fall in Brazil’s sugar output in the year 2018–19 (nearly 22–30%) was mainly due to the diversion of cane for ethanol production. However, as per (USDA 2020) global market analysis report- 2020, Brazil would regain its position as the largest (39.4 mt) producer of sugar. The decline in India’s sugar output is attributed to many factors which include change in climatic conditions, poor & erratic rainfall in many states, drought and diversion of cane juice and B-molasses into ethanol production. Like the other crops, the impact of climate change has significant implications on the global sugarcane productivity and sustainability. Looking into future climate scenarios, the crop will be vulnerable to severe biotic and abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, waterlogging, high temperature, and low temperature. The magnitude of abiotic stresses has significant economic and ecological impacts on sugarcane production, leading to annual losses of billions of dollars worldwide. Although, farmers have adopted new varieties of the crop, and modified crop practices in accordance with climate changes, the pace of environmental changes is likely to be unprecedented with rising global temperature. A significant change in temperature due to climate change will exert an ampule impact in terms of the emergence of the new diseases, insects, pests, and weeds in the sugarcane production system. Considering the Indian scenario, sub-tropical states, despite having 55% of the sugarcane area of the country (2017–18), contribute only 48% of sugarcane and 38% of white sugar production. The best climate for sugarcane production lies between 10° and 20° north and south latitudes of the country, respectively. The ideal temperature for sugarcane crop germination is 26–32 °C and the optimum temperature for crop growth is 30–33 °C. Owing to climatic vagaries many stresses such as high-temperature, salinity, cold temperature, flooding, and toxicity of elements during the crop growth period in the subtropical regions, restrict the active growth period of the crop up to 8–9 months. During the peak winter period (December and January), the temperature falls below 5 °C, whereas, during the month of May–June, the average temperature reaches more than 43 °C. Temperature more than 38 °C affects photosynthesis in sugarcane and increases the respiration rate, which ultimately affects the cane productivity and juice quality in the region.

Various abiotic stresses such as salt stress, high temperature, cold stress, submergence conditions, heavy metal toxicity, low and high nutrient contents of soil, and high radiations affect the crop production as a consequence of the rapidly changing climate in the region. Hence, the development of multi-stress tolerant sugarcane cultivars becomes a focus in the present era of climate change. In view of the above, this article emphasizes an integrated approach consisting of current breeding and genomic strategies to enhance sugarcane productivity under climatic vagaries conditions. Taken together, the information provided in the article will increase the current understanding towards the molecular basis of crop adaptation to abiotic stresses, future modified breeding, and genomic strategies to manipulate the target genes/traits for improving the ability of the plants to withstand abiotic stress conditions and result in better crop yield.

Strategies to enhance the abiotic stress tolerance

Conventional breeding strategies and current programs

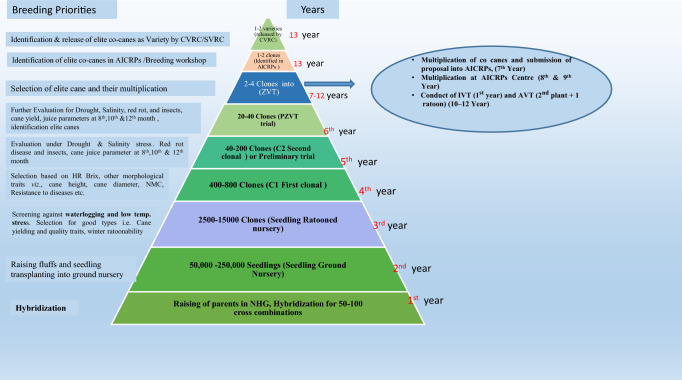

Contemporary sugarcane cultivars are generated as a result of interspecific hybridization between Saccharum officinarum (a species with high sugar content having a chromosome number of 2n = 80 and basic chromosome number of × = 10) and Saccharum spontaneum (a wild species tolerant to various abiotic and biotic stresses with chromosome number (2n = 5× = 40 to 16× = 128; × = 8) (D’Hont et al. 1998; Grivet and Arruda 2001). Saccharum complex, a term coined by Mukherjee (1957), is a close interbreeding group comprising six species of Saccharum (i.e. S. officinarum, S. robustum, S. spontaneum, S. barbari, S. sinense, S. edule) and allied genera (i.e. Erianthus, Sclerostachya, Miscanthus, and Narenga). Hybridization techniques are mainly used to generate new recombinants in the sugarcane breeding program, followed by a selection of superior clones with high sucrose and cane yield. Under the changing climatic conditions, the main criteria for the selection of good parental lines should depend upon the response of clones to various biotic and abiotic stresses in addition to the cane yield and sucrose content. Selection of desired clones should be done at different stages of selection (in the ground nursery stage, first clonal stage (C1), second clonal stage (C2), and pre-zonal varietal trial (PZVT) stage), before these clones enter into zonal evaluation trials. To identify the good ratoonability potential of newly developed sugarcane clones, ratooning of the ground nursery during the peak winter season (December or January) followed by selection in the early stage of the crop (8th month) should be performed. Similarly, to screen the drought, waterlogging, and salinity tolerant clones, these stresses can be imposed during the C2 and PZVT stages. By following these approaches, it can be easy to identify the early maturity, high vigorous, and better-performing entries ideal to particular climates. Modified breeding strategies are suggested, and the same is depicted in Fig. 1, that should be used to select the desired sugarcane clones/ varieties under abiotic stress situations.

Fig. 1.

Basic steps involved in the selection process for release of a variety under abiotic stress conditions

Sugarcane improvement through conventional breeding approaches has been successfully implemented throughout the world. The existing methods and revised criteria for the selection of desired clones for abiotic stresses are suggested in Table 1. Sugarcane breeding involves mainly two approaches for selection: (i) Individual selection, and (ii) Family selection. The selection of individual clones with a high heritability of desirable traits (high sugar, disease resistance, cane yield) is essential, whereas the family selection is more efficient and effective only when heritability based on family means is higher than that of the individual plant (Falconer and Mackay 1996). In sugarcane, the association of family selection with individual selection is more productive than based on family only. Besides this, sugarcane breeding programs require specific regional strategies for the development of locally adapted varieties. Under this, cane seedlings have to be screened in local environmental conditions to facilitate the selection of location-specific sugarcane varieties. In addition, it would also provide precise information regarding genotypes and environment interaction (G × E), which is essential to select the desired clones in a specifically adapted environment. G × E interactions play an important role in the determination of stability and identification of favorable environments for different sugarcane genotypes (Meena et al. 2017). When a variety shows high cane yield and stability under particular environmental conditions, it could be promising for selection into that specific environment.

Table 1.

Basic and revised criteria under abiotic stress conditions to identify the desirable sugarcane clones

| Breeding activity | Present criteria | aRevised criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Selection of parents | Based on parent value, and their potential to generate good progenies | Use of the existing cultivars with ISH and IGH species to introgress biotic and abiotic stress tolerance traits |

| Hybridization | Bi-parental crossing (where, both male and female parents are known) | Bi-parental crosses, general cross (where male parents are unknown) and poly crosses (more than one males are involved) to generate segregating populations and better combining ability |

| Selection of genotypes | Morphologically superior genotypes in terms of stalk population, cane diameter, spines, cane height etc | High sucrose, major diseases ( RR, smut, wilt) and insects (top borer, root borer and ESB) resistance, abiotic stress tolerance; stay green, high biomass, no. of stalk, leave architecture, plant canopy and plant growth habit, adherence of leave sheath, absence of pithiness etc |

|

Selection stage Ground nursery |

Selection of traits of high heritability (brix, flowering habit, few disease resistance) at initial stage | Selection of traits of high heritability at initial stage and low heritability traits (no. of stalks, stalk diameter, cane weight) at later stage, increase the genetic gain |

| C1 stage | C1 stage selection was performed in a particular location with red rot (RR) rating, without screening for abiotic stresses from the multiplication plot | Selection need to perform with screening of C1 clones against the abiotic stresses prevailing in specific location, RR rating and the experimental trial should be planted in ABD design with commercial checks to identify the superior performing varieties |

aRevised criteria to identify the suitable clones for abiotic stress conditions; ISH Interspecific hybrids, IGH Intergeneric hybrids, ESB Early shoot borer, ABD Augmented block design, C1 First clonal evaluation stage, RR Red rot

Current breeding approaches for abiotic stress tolerance

Sugarcane productivity is hampered to a great extent by various environmental stresses, which further depend upon an increase in intensity and frequency of extreme environmental conditions. The negative impact of climate change on sugarcane is associated with its geographic location and adaptive capacity of the cane genotypes. However, ample research has been conducted so far to document these effects on crop productivity (Kumudini et al. 2014). The main aim of sugarcane breeding programs is to enhance sugar yield either by increasing sugarcane yield per unit area or through the selection of desired climate-resilient early-maturity clones with high sugar and yield. Various breeding approaches should be used for the selection of elite sugarcane clones under prevailing abiotic stress conditions that are being discussed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morphological traits considered for drought tolerance in sugarcane

| Morphological traits | Age (DAP) | Stress applied | Time of stress (Days) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers of tillers | 60 | Withholding water | 90 | Silva et al. (2008) |

| Stalk diameter and stalk length |

55 60 90 |

Withholding water; water supply at first day followed by 3 days withholding | 12;28;90 | Hemaprabha et al. (2013); Zhao et al. (2013) |

| Single cane stalk | 60 | Withholding water | 90 | Hemaprabha et al. (2013) |

| Numbers of internodes and Internode length | 60 | Withholding water | 90 | Silva et al. (2008), Hemaprabha et al. (2013) |

| Shoot dry mass |

60 83 |

Withholding water | 4;25 |

Medeiros et al. (2013) Ribeiro et al. (2013) |

| Root dry mass |

60 100 |

Withholding water | 4;10 | Jangpromma et al. (2012), Medeiros et al. (2013) |

|

Leaf parameters (length, width, numbers of green leaves) |

90 | Water supplied at first day followed by 3 days of water withholding | 28 | Wang et al. (2003) |

| Root parameters (length, surface area and volume) | 100 | Withholding water | 10 | Jangpromma et al. (2012) |

(Sources: Ferreira et al. 2017)

Selection for drought-tolerant clones

Drought is one of the most important constraints for sugarcane production. According to an FAO estimate (https://www.fao.org/3/n-i7378e.pdf), 80% of losses in the agriculture sector of the developing countries are caused by the drought. Under drought stress, sugarcane survival will be at stake as a result of reduction in its growth and production potential. Sugarcane being a C4 plant is considered a highly photosynthetic and water-uptake efficient crop. During day time, it can close leaf stomata partially to minimize water losses and continue its carbon assimilation process. Broadly, sugarcane crop has four distinctive crop growth phases (a) germination phase at 45 days after planting (DAP), (b) tillering phase (60–120 DAP), (c) grand growth phase (120–240 DAP) and (d) maturation phase (300–360 DAP). For the desired crop yield, tillering and grand growth are very important phases and water stress during these stages significantly limits the development of stem and leaf (Machado et al. 2009; Lakshmanan and Robinson 2014). Cane formation and elongation occurs very actively during the grand growth phase (Jaiphong et al. 2016), and water stress during this stage leads to losses of crop production up to 60% (Basnayake et al. 2012). However, moderate stress during the maturity stage exerts a positive effect on sucrose yield. In sugarcane, one of the effective approaches to screen the abiotic stresses tolerance clones is to impose the stresses at a specific crop stage for a certain duration and recording the observation on physio-biochemical parameters during various crop intervals (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of important physio–biochemical parameters for various abiotic stresses in sugarcane

| S. no | Abiotic stress | Level of stress | Crop stage at which stress is imposed | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Drought and water deficit | Drought plots were irrigated at 80% depletion of available moisture | Grand growth phase (150–240 days after planting) | Chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm), SPAD index, RWC (Silva et al. (2011)) |

| 10 days of withholding irrigation resulting leaf water potential up to − 2 MPa | Germination phase | Membrane stability index (MSI), Nitrate reductase (NR) and lipid peroxidation (Venkataramana et al. (1987)) | ||

| No irrigation during 60–150 days after planting | Formative phase (days 60–150 days) | Leaf area index (Venkataramana et al. (1984, 1986)) | ||

| Withholding of irrigation for few days | Formative phase (days 60–150 days) | Stomatal resistance and leaf water potential (Naidu et al. (1983)) | ||

| Soil moisture 12.8% | Grand growth phase (150–240 days after planting) | Canopy temperature depression (CTD), Chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm), SPAD index (Arun et al. (2020)) | ||

| 2 | Salinity | Salinity 8 dSm−1 electrical conductivity | Grand growth phase (150–240 days after planting) | Better root biomass with live rope roots, Lipid peroxidation, K+/Na+ ratio, Membrane stability index (MSI) (Vasantha and Gomathi (2012)) |

| Salinity 8 dSm−1 electrical conductivity | Formative phase and grand growth phase | Leaf area index (LAI). SPAD, Chlorophyll fluorescence (Vasantha et al. (2017)) | ||

| 3 | Waterlogging/sub-mergence | 15 days of submergence | Germination phase | Lipid peroxidation, Antioxidant enzymes and MSI (Gomathi et al. (2012)) |

| 4 | High temperature | High-temperature stress (47 °C) | Formative stage | Phytepsin, Ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase, and stress protein DDR-48 expression increased threefold (Raju et al. (2020)) |

| 4 | Cold/Low Temp | Two months of cold under natural field condition | During sprouting phase after harvest & during 240–300 days |

Winter sprouting index (Ram et al. (2017)) Winter growth during peak winter period |

| 5 | UV rays | UV B rays (280–315 nm) 5 kJ/m | Germination phase | Ion leakage (Li et al. (2006)) |

aFv/Fm is a normalize ratio created by dividing variable fluorescence by maximum fluorescence, RWC Relative water content, SPAD soil plant analysis development index, DDR-48 (responsive for defense regulation)

Several studies demonstrated the effects of water stress on physiological processes of the plant life (Sah et al. 2016; Ferreira et al. 2017) and on plant canopy development (Smith et al. 2005). Cell division and elongation patterns for leaf extension and leaf appearance were restricted relatively. Water stress under severe conditions affects the entire plant and its morphological and physiological behavior, which varies from one genotype to another genotype. The variation in genotypic response for different cane parameters depends upon the duration and intensity of stress. The response of highly exploitable genetic variation for cane and sugar yield was observed under water stress (Hemaprabha et al. 2004, 2006; Vasantha et al. 2005; Basnayake et al. 2012; Meena et al. 2013, 2014). Among various morphological traits, shoot parameters such as stalk height, tiller population, stalk diameter, stalk weight, number of millable canes; leaf parameters such as length and width of leaves and number of green leaves; and root parameters such as root length, root surface area, and volume are most affected under drought stress (Table 4). However, these traits are more variable and their expression depends more upon the genotypes. Therefore, the selection of these desired traits is important under a prevailing drought stress environment. As noticed by many researchers, high sugarcane yield is associated with traits such as higher stalk numbers, cane height, and single cane weight (Silva et al. 2007). On the other hand, many associated physiological traits (leaf chlorophyll content, photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, leaf and canopy temperature, and transpiration rate) are used as indirect selection criteria for selection of genotypes tolerant to drought stress (Silva et al. 2012; Basnayake et al. 2015). Drought tolerance can be increased in plants by previous exposure to water deficit conditions (Fernanda et al. 2018). In addition, the stay-green phenotype of sugarcane leaf is also considered as an important trait for sustaining high yield under drought (Blum 2005). Among root traits, the depth and volume of roots are regarded as a selection criterion in sugarcane for water stress tolerance (Smith et al. 2005). The exploitation of wild species S. spontaneum and allied genera such as Narenga spp. and Erianthus spp. in sugarcane breeding could be the best strategy to incorporate drought tolerance in sugarcane. Allied genera of Erianthus spp. has many desirable agronomic traits such as tolerance to drought, waterlogging, good ratooning ability, disease resistance, and high vigor; it could serve as a potential source to introgress many useful traits into sugarcane cultivars. Efforts are on to generate hybrids from Saccharum spp. and E. arundinaceus crosses. A hybrid between E. arundinaceus and S. spontaneum L. is repeatedly crossed as a female parent with commercial varieties of sugarcane to generate near commercial sugarcane genotypes. One near commercial sugarcane hybrid Co 15015, (2n = 106) was confirmed with E. arundinaceus chromosomes through genomic in situ hybridization (GISH). It was the first report of a sugarcane hybrid containing both alien cytoplasm and chromosome from E. arundinaceus (Lekshmi et al. 2017). The volume of roots and polyphenol content of the roots were found to influence the extent of drought tolerance in the intergeneric hybrids (Sugarcane × Erianthus) (Fukuhara et al. 2013). A recent approach of transcriptome sequencing of sugarcane against abiotic stress factor such as drought can give insight into molecular mechanism and strategy for developing tolerant cultivars. Research on transcriptome profiling of drought-tolerant and sensitive varieties under water deficit conditions was reported by Belesini et al. (2017). They investigated DGEs for drought- tolerant and sensitive varieties, and found that diverse genes such as MYB, E3, SUMO-protein ligase, SIZ2, and aquaporin involve drought stress tolerance in sugarcane. These genes/TFs could play an important role in imparting drought tolerance in sugarcane crops.

Table 4.

Saccharum species clone reported to be high saline tolerant

| Species | Name of clones |

|---|---|

| S. barberi | Katha, Kewai-14-G, Khatuia-124, Kuswar, Lalri, Nargori, Pathari |

| S. robustum | IJ 76-422, NG 77–55, NG 77–160, NG 77-167, 57 NG201, NG77- 237,28NG251 |

| S. sinense | Khakai, Panshahi, Reha, Uba |

Selection for salinity-tolerant clones

Salinity is one of the major environmental stresses that adversely affects soil health, environmental quality, and agricultural production. It is a major problem affecting crop production all over the world; about 20% of cultivated land and 33% of irrigated land being salt-affected and degraded in the world (Almeida et al. 2017). Furthermore, the salinized area is increasing at a faster rate annually for various regions, due to factors such as low precipitation, excessive evaporation, irrigation with saline water, and poor agricultural practices. On the other hand, the twin problems of waterlogging and soil salinity are threatening the sustainability of agricultural production at a larger scale. Sugarcane being a glycophyte plant exhibits moderate tolerance to salinity and high sensitivity to high salt concentration at various growth stages, resulting in significant losses (Patade et al. 2008). Salinity-tolerant clones accumulate fewer Na+ and higher K+ in plant tissues compared to susceptible clones, and therefore a tolerant clone shows a higher K+: Na+ ratio (Wahid and Ghazabfar 2006). Similarly, tolerant sugarcane clones show a higher level of flavonoids accumulation, which is an important antioxidant that protects the sugarcane against ion-induced oxidative stress caused due to salinity. Moreover, seedling priming which is an important practice adopted for sugarcane to improve germination and tillering, is now gaining importance. Priming of seedling with NaCl treatment improves seedlings tolerance against salt stress (Patade et al. 2009). The early stages of the crop, such as germination, tillering and cane formation, are more sensitive to salinity than the later stages. It has also been noticed that the ratoon crop is more sensitive than the plant crop of sugarcane, and characteristics such as good germination, high tillering, stem color, pink and waxy stem, number of green leaves and leaf area index (LAI), root-and-shoot ratio, and ratooning potential have a positive correlation with salinity tolerance.

Most of the existing and potential waterlogged saline soil occurs in the arid and semi-arid regions in the central inland depression basin of the world and technologies such as subsurface drainage, use of chemical amendments, irrigation management, and agroforestry have made it possible to grow a wide range of crops even in the highly deteriorated saline and sodic soils. Nevertheless, many of these techniques have inherent limitations that have thwarted their large scale adoption by the farmers in salinity-affected regions. The use of salt-tolerant cultivars represents an innovative and cost-effective strategy to sustain crop production in saline environments. Identification and development of crops and their cultivars with improved salt tolerance have been the key to improve productivity. Sugarcane genotypes, due to their divergent genetic background, significantly differ with respect to salinity response. Several Saccharum spp. and allied genera such as Erianthus spp., S. barberi, S. sinense, and S. robustum are considered as a good source for imparting salinity tolerance in commercial cultivars (Table 5; Rao et al. 1985). The extensive genetic diversity in allied genera could be exploited to identify the important salt tolerance genes in sugarcane. Several miRNAs can play an important role in response to salinity in sugarcane. High-throughput sequencing of sugarcane clones exposed to salt stress revealed that salt stress in the sugarcane is regulated by many miRNAs, which can be used to develop molecular markers to be used in sugarcane breeding (Mariana et al. 2013).

Table 5.

Wild species and allied genera used to impart tolerance to major abiotic stresses in sugarcane

| S. no | Major traits | Genera/species | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tolerance to cold |

Miscanthus spp. Miscanthus nepalensis S. spontaneum S. barberi Erianthus fulvus |

Earle et al. (1928) Krishnamurthi et al. (1989) Anonymous (1987) Nair et al. (2006) Sreenivasan et al. (2001) |

| 2 | Tolerance to drought |

S. spontaneum Erianthus spp. Narenga spp. |

Krishnamurthi et al. (1989) Roach et al. (1987) Sreenivasan et al. (2001) |

| 3 | Tolerance to salinity | S. robustum, Erianthus spp., S. barberi, S. sinense |

Ramana et al. (1985) Sreenivasan et al. (2001) |

| 4 |

Tolerance to Water logging |

S. robustum, S. spontaneum | Krishnamurthi et al. (1989) |

Selection for cold-tolerant clones

Sugarcane is considered as a cold-sensitive crop. Cold stress can be categorized broadly into two groups: chilling stress (15–0°) and freezing stress (< 0°), which are important environmental stresses affecting plant growth and development, and ultimately crop productivity (Xin and Browse 2000). Chilling and low-temperature stresses restrict the plant growth, affect biomass production, shorten the internodes, and finally, decrease the crop yield. Sucrose content in cane juice is less affected by low temperatures (Clements 1980). Freezing stress causes disruption of cell membrane function, denatures many regulatory proteins, and generates ROS (reactive oxygen species) (Shao et al. 2007). The optimum temperature for sugarcane crop ranges from 25° to 35o C to produce highest sugar yield (Clements 1980). Although, frost is not a usual phenomenon in subtropical areas when it occurs, there are crop failures accompanied with reduced capacity for sucrose accumulation in the cane stalks (D’Hont et al. 2008). Cold damage of mature plants can kill the re-growth of young plants and result in poor ratoon crops. Under chilling temperatures, the photosynthetic activity of the plant becomes severely reduced (Inman-Bamber et al. 2010).

Hybridization of Erianthus with sugarcane has resulted in introgression of genes for cold tolerance and red rot resistance (Ram et al. 2001). Crosses between cold-tolerant species of Saccharum, especially S. spontaneum, and commercial sugarcane (S. officinarum) have generated new ‘hybrids’ cultivars that are tolerant of the contingent chilling present in warm climates (Khan et al. 2013). Crosses between cold-tolerant species of Saccharum, especially S. spontaneum, and commercial sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) have generated new ‘hybrids’ cultivars which promise to be tolerant of the contingent chilling present in warm temperate climates (Khan et al. 2013). Several cold-tolerant genes were introgressed from wild species into commercial cultivars of sugarcane through conventional and molecular breeding approaches (Table 5). In addition, attempts were also made to cross sugarcane with allied genera of Miscanthus (grows in a temperate region, identified as high cold tolerant) to generate novel chill-tolerant sugarcane hybrids (Heaton et al. 2010). For cold tolerance, sugarcane breeding strategy includes the following: (i) evaluation of parents under low temperature and identification of the tolerant ones, (ii) use of tolerant clones in hybridization programs, (iii) progeny evaluation and identification for cold tolerance, and (iv) use of back-crossing and recurrent selection in a systematic manner for getting the desired recombinant. In addition, many genomic approaches are used to identify cold-tolerant genes in sugarcane. Recently, the use of the NGS approach in sugarcane has opened a new vista to decipher key pathways/genes regulating cold tolerance. In our experiment, transcriptome profiling of the low-temperature-tolerant (10 °C) S. spontaneum clone IND 00–1037 collected from high-altitude Northern Eastern region of Himalayas through Illumina Nextseq500 was performed and it was identified that a total of 2580 genes up-regulated and 3302 genes down-regulated in leaves. It was also shown that cold-responsive genes (COR), low temperature, dehydrins, LEA proteins, heat shock proteins (HSP), aquaporins and osmolytes play a very significant role in cold acclimatization in S. spontaneum after 24 h of low-temperature (LT) stress (Dharshini et al. 2016, 2018). The transcriptome profiling of S. spontaneum under cold stress confirmed that the SspNIP2 gene is involved in cold tolerance (Park et al. 2015). In our experiment, transcription profiling of roots during LT stress revealed cold stress sensors (i.e. proline, malate dehydrogenase (MDA), calcium-dependent kinase, G-coupled proteins, and histidine kinase) that trigger and activate signal transduction through transcription factors (i.e. MYB, ERF, ARF2, DREB, CAMTA, and C2H2), resulting in up-regulation of LT stress-responsive genes (i.e. annexin, LEA, germins, LT dehydrins, osmotins, and COR), thereby enhancing cold tolerance (Dharshini et al. 2018, 2020).

Selection for waterlogging-tolerant clones

Waterlogging is one of the major abiotic stresses that remain a significant constraint for crop production in low-laying rainfed areas of the world. Global climate change causes waterlogging events to be more frequent, severe, and unpredictable [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2014]. At the global level, two-thirds of damages and losses to agricultural crops were caused by floods between 2006 and 2016, with an estimated value of billions of dollars (FAO 2017). Under the waterlogging (WL), water covers only the root portion, whereas in the submergence part of the plant is completely covered with water. Both types of flooding disrupt the movement of oxygen from the air to the plant and create hypoxic conditions (< 21% O2) (Sasidharan et al. 2017). Oxygen-deprived conditions at the root zone forces plant to shift its metabolism from aerobic mode to anaerobic, which hampers nutrient and water uptake and restricts its growth; as a result, the stressed plant shows wilting symptoms and ultimately dies. Low relative growth rate, higher stalk mortality, reduced cane yield, and quality losses are major effects of WL on sugarcane crops. Many factors such as, location of the trial duration of WL, the flow of water and its depth, presence of aerial roots, the growth stage of the crop and kinds of genotypes, etc. are deciding factors in sugarcane production (Fukao et al. 2019). Waterlogging during the formative stage of cane did cause a13% reduction in plant height, 21.63% reduction in tiller population, 26.52% reduction in leaf area, and 42.5% reduction in biomass production (Gomati et al. 2015). Waterlogging stress significantly reduces leaf, stem inter-nodal length, and total dry matter as a result of reduction in biomass production (Gomati and Chandran 2010). Cane yield losses range from 15 to 45% and further depend upon the factors such as genotypes, duration of stress, and developmental stage of the crop. Therefore, identification of tolerant sugarcane clones to waterlogging is an immediate need of the hour under the present adverse climatic scenario.

During waterlogging conditions (6 months of flooding), clones of S. officinarum did not survive whereas those of S. barbari, S. sinense, Erianthus spp. and Sclerostachya have survived, however they were observed to be susceptible. However, wild species such as S. spontaneum and S. robustum showed good tolerance to waterlogging conditions and they could withstand standing water for a longer duration (Krishnamurthi et al. 1989). Even S. spontaneum derived accessions had good ratoonability after flooding conditions. Mullins and Roach (1985) evaluated five of Saccharum and several hybrids in an Australian breeding program and found that the clones of S. spontaneum had good waterlogging tolerance and ability to ratoon after flooding. However, the use of this germplasm into a sugarcane breeding program requires many years of effort. Hence, our major focus should be on the screening of commercial clones/newly developed sugarcane varieties (having S. spontaneum and S. robustum in their genome) and identifying the desired clones suitable for WL tolerance. Furthermore, to widen the genetic base and to impart greater tolerance to flooding, sugarcane is being hybridized with allied genera Miscanthus spp. (Glowacka et al. 2016) and a flood- and chilling-tolerant grass (Mann et al. 2013).

Clones which have increased aerenchyma formation, more active glycolytic cycle, increased availability of soluble sugars, and the formation of antioxidants for a defence mechanism to cope oxidative stress (induced by WL; Yeung et al. 2018; You et al. 2015), are tolerant to WL and can withstand under flooding conditions for a longer duration (Table 6). The genetic potential of sugarcane was demonstrated for flooding tolerance in a multi-harvest field test, where clones valued for their sugar or biomass yields were able to retain productivity (Viator et al. 2012). The WL stress during formative stage (90–170 DAP) caused 21.63% reduction in tiller population and 26.52% reduction in leaf area, whereas the least reduction have been observed in WL-tolerant clones such as 91WL 552, 91WL 629, 92WL 1390, 92WL 1029, 97WL 633, 99WL 379 and 98WL 1357. It was also noticed that clones having profuse development of fibrous negative geotropic root with aerenchyma are tolerant to WL stress.

Table 6.

Differential response of sugarcane crop under waterlogging conditions

| Physiological changes | Biochemical changes | Molecular changes |

|---|---|---|

|

Retardation of growth and cane height Reduced tillering Inhibition of stem elongation (shortening of internodes) Formation of aerial root (adventitious) Negative geotropism of aerenchyma Early senescence of plant leaves Decrease in total biomass production |

Quality of cane (sucrose) down Decrease in protein and RNA synthesis Increase in ethylene production in root of cane Increase in ROS, SOD and ADH activity Reduction of NRase activity |

Up regulation of candidate genes: ACC Oxidase, ALDH5F1, Submergence induce proteins (ANP’s), G box binding factor |

ROS reactive oxygen species, SOD Superoxide dismutase, ADH Alcohol dehydrogenase, ACC Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

The function of miRNAs in WL stress is estimated by the identity and function of their target and consequent downstream effects. Therefore, an integrated approach, including transcriptome data, degradome data, ARGONAUTE immunoprecipitation and translational analyses (Zhai et al. 2013; Juntawong et al. 2014; Franke et al. 2018), is more appropriate for identifying the miRNAs target and downstream regulation. In certain situations, novel non-conserved miRNAs that are responsive to flooding were identified. In addition, the identification of such miRNAs involved in tolerance to flooding could be facilitated by analysis of the natural variation using different ecotypes with contrasting traits (Liu et al. 2012) and using flooding-tolerant models such as Sesbania (Ren et al. 2017). Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with agronomical traits such as root architecture (aerenchyma and adventitious root), inter-nodal length, cane diameter, cane height, and number of millable canes, can be used for identifying miRNAs involved in waterlogging tolerance.

Selection for high temperature stress-tolerant clones

High-temperature stress is one major environmental factor that impacts the cane productivity significantly. The rise in temperature beyond the threshold level for a sufficient time causes irreversible damage to plant development. Any rise in temperature by a single degree above the threshold level is considered as heat stress (Hasanuzzaman et al. 2013). With the rise in temperature, plant metabolic activities increase. It may significantly impact upon leaf photosynthesis, water balance, membrane stability, and respiration activities (Kaushal et al. 2016). A decrease in leaf photosynthesis limits the required photosynthates to keep pace with normal plant growth (Camejo et al. 2005). As a result, leaf numbers, tillering, cane height, inter-nodal length, and single cane weight were markedly reduced. Heat stress condition dis-balances many enzymatic pathways, causing denaturation and dysfunction in many proteins, and disturbs cellular homeostasis, leading to severe retardation in cane growth, development, and even plant death. Sunburns of leaves and scorching of twigs, branches and stems, leaf senescence, and abscission are some other morphological losses associated with heat stress (Vollenweider et al. 2005). Heat stress causes many physiological and biochemical changes such as reduction in plant chlorophyll content, chlorophyll stability index, chlorophylls value, nitrate reductase (which play an important role in amino acid biosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism, and the protein synthesis), sucrose mobilizing enzymes such as sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS), sucrose synthase (SS), acid invertase (AI) and neutral invertase (NI).

Changes that occur during a stress period reduces the partitioning of photosynthates, which is morphologically expressed as retarded growth and reduced economic yield, harvest index, and cane productivity. However, proline concentration, total phenol accumulation, antioxidant enzyme activity (superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POX)), lipid peroxidase, membrane injury index, and soluble sugar content get enhanced under heat stress (Kohila and Gomati 2018). Proline and soluble sugar contents are essential for regulating osmotic cell activities, maintaining the water balance of the cell and membrane stability, and buffering the cellular redox potential (Farooq et al. 2008). Enhanced synthesis of secondary metabolites under heat stress situations also protects against oxidative stress. Phenol, a secondary metabolite with an important role in environmental stress, is associated with heat stress tolerance in plants. Glycinebetaine plays an important role in plant tolerance to high temperatures. Glycinebetaine accumulation in chloroplasts maintains activation of the Rubisco enzyme by sequestering Rubisco activase enzyme near thylakoids, thereby preventing its thermal inactivation (Allakhverdiev et al. 2008). Increased levels of glycinebetaine (GB) were reported in sugarcane under high temperatures (Wahid and Close 2007).

If a genotype shows a higher photosynthetic rate, increased membrane stability, higher proline and phenols, and glycine betaine accumulation, it is considered as heat-tolerant. Heat-resistant sugarcane genotypes show less reduction in SS and SPS activities under elevated temperature (42 °C). S. spontaneum and Erianthus are the main sources of heat tolerance in sugarcane varieties. Hence, the selection of cane genotypes with these genetic backgrounds could contribute to heat tolerance under field conditions. Many genotypes tolerant to high- temperature stress were identified through intensive measurement of physiological and biochemical traits (Zhao and Li 2015).

Selection of clones for multiple abiotic stress tolerance

Sugarcane being a long-duration crop (10–12 months in North and 14–16 months in South India) experiences various abiotic stresses (salinity, drought, cold stress, heat stress, high nutritional toxicity, pollution, etc.) at various stages of the crop cycle. Sometimes multiple stresses occur together in nature or the occurrence of one stress aggravates another type of abiotic stress. The prolonged waterlogging condition leads to salinity, alkalinity, and Fe toxicity. Similarly, drought situations may lead to salinity and high/low temperature may lead to drought conditions (Srivastava et al. 2016). To augment these stress challenges, an integrated approach consisting of physiological, and molecular approaches are important (Table 7). Hence, identification of multi-stress-tolerant sugarcane genotypes becomes more relevant under changing climatic scenarios. Among the several physiological and biochemical traits identified, many show association with more than one abiotic stress, viz., trehalose, and betaine contents in sugarcane. Further, the genotypes identified for abiotic stress tolerance within a particular sugarcane-growing zone need to be evaluated in other sugarcane-growing zones as well for observing the performance of these adapted clones to various abiotic stresses.

Table 7.

Characteristics of sugarcane varieties having tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses

| Center | Name of variety (s) | Tolerance to abiotic stress |

|---|---|---|

| Pusa, Bihar | BO 34, BO 70, BO 128 | Drought and water logging |

| BO 106 | Drought and salinity | |

| BO 99, BO 128 (Pramod) | Waterlogging and salt | |

| ICAR-IISR | CoLk 94,184 (Birendra), CoLk 8102, CoLk 8001 | Water logging and drought |

| ICAR-SBI | Co 210, Co 285, Co 6907, Co 7717, Co 8371, Co 86011, Co 87268, Co 89029, Co 98014, Co 0124, Co 0232 (Kamal), Co 0233 (Kosi), Co 0238 | Drought and water logging |

| Co 8145, Co 88019, Co 94008, Co 99004, Co 2001–13, Co 2001–15, Co 0238, Co 0118 and Co 05011, Co 09004 | Drought and salinity | |

| Co 285, Co 312, Co 421 | Low temperature and drought | |

| Co 395, Co 453, Co 87263 | Waterlogging and salt | |

| Co 05009 | Waterlogging and Low temperature | |

| SRS, Padegoon | CoM 0265, CoM 7125 | Drought and salinity |

| UPCSR | CoS 797, CoS 510 | Drought and salinity |

| GBPUAT | CoPant 97222, 93227, | Waterlogging and salt |

| CoPant 90223 | Drought, waterlogging and low temperature | |

| ARS, Kota | CoPk 05191 (Pratap Ganna-1) | Tolerant to drought & water logging, good ratooner |

| ARS, Sankeshwar | CoSnk 05103, CoSnk 05104 | Tolerant to salinity, water logged, complex stresses. Excellent ratooning ability |

| SRS, Nayagarh | CoOr 03151 (Sabita) | Tolerant to drought & water logging |

aICAR Indian Council of Agricultural Research, IISR Indian Institute of Sugarcane Research, SBI Sugarcane Breeding Institute, SRS Sugarcane Research Station, GBPUAT Govind Vallab Pant University of Agricultural Technology, UPCSR Uttar Pradesh Council of Sugarcane Research

Genome-assisted breeding strategies

Global climate change causes biotic and abiotic stresses, resulting in a significant reduction in crop yield and productivity. Even though carbon enrichment due to climate change was found to be beneficial for C4 crops such as sugarcane (Zhao and Li 2015). Favorable interacting environmental factors and abiotic stresses such as drought, extreme temperatures, soil, and water alkalinity affect sustainable sugarcane production. Many of the emerging infectious diseases are of significant concern under changing environmental weather parameters (Anderson et al. 2004). For example, the incidence of sugarcane smut disease has increased due to hot and dry environmental conditions (Bhuiyan et al. 2013), indicating increased epidemics of sugarcane diseases as a result of global climate changes. Owing to the complex and polyploidy nature of the sugarcane genome, the use of new molecular techniques such as genome selection, NGS, and genome editing are indeed a few advantages to achieve improved stress tolerance and productivity. Hence, evaluation, characterization, and utilization of sugarcane germplasm using modern tools such as genomic selection (GS), genome-wide association study (GWAS), marker-assisted selection (MAS) and linkage mapping are important in sugarcane breeding programs to evolve a new strategy to mitigate the impact of changing climate (Zhao et al. 2015).

Now, it is a well-known fact that stress tolerance is regulated by many genes/transcription factors (TFs) which enable plants to withstand unfavorable conditions. TFs are predominantly the key molecular switches that make them potential genomic candidates for application in stress tolerance engineering. Advancements in sugarcane genome sequencing and genetic mapping assists in pinpointing the locations of genes or markers for abiotic stress tolerance. miRNAs play an important regulatory role in sugarcane abiotic stress tolerance. Many target genes have been discovered for multiple stress tolerance in sugarcane (Table 8). Novel miRNAs for drought and salinity tolerance were identified in past works (Ferreira et al. 2012; Thiebaut et al. 2012; Jin-long et al. 2012). The genome editing and short tandem target mimic technologies could be exploited for the efficient use of miRNAs for trait improvement in sugarcane. Besides the classical pathways, novel loci of miRNAs origin and their role in abiotic stresses need to be deciphered for their effective use. Different proteins expressed in response to various abiotic stresses allow the exploitation of many molecular pathways involved in stress responses. Proteome analysis at differential conditions allows for the production of new cultivars via their use in breeding programs. Millions of plant germplasm accessions lying in gene banks are largely underutilized due to various resource constraints. However, with the advent of next-generation sequencing, it is not only easy to discover the new variability prevailing in the core germplasm but possible to identify the genomic regions associated with agronomically important traits. Identification of many novel genes/alleles becomes easy through genotyping by a sequencing approach. Genes associated with important plant traits were isolated through the strategies detailed by Peng-fei et al. (2017) and Andrade et al. (2014). Novel stress-induced sugarcane genes confer tolerance for drought, salinity, and oxidative stress in tobacco, as reported by Begcy et al. (2012, 2016). The prediction through various models could enable use of valuable markers in the crop improvement programs through genomic-assisted selection (Yu et al. 2016). In view of this, GWAS and genomic-assisted selection are gaining significance in sugarcane breeding due to the following advantages over MAS. Firstly, germplasm accessions are preferred mapping population because it does not affect the GWAS and GS, whereas bi-parental mapping population is required for the identification of QTLs in MAS. Secondly, optimal germplasm accession is sufficient for GWAS compared to a larger population in polyploid species for MAS. Thirdly, many models are available for genomic prediction for polyploid species. Therefore, GWAS, genomic prediction, and further refining of the genome prediction models certainly help breeders in the accurate selection of an ideal plant type and parental lines in complex polyploidy crops like sugarcane. Therefore, GWAS by genotyping-by-sequencing, marker-trait association, genomic prediction, and remodeling help breeders to locate the linked markers for important traits for various biotic and abiotic stresses. Till now association mapping (AM) and GS were slow due to the need of very high marker density coverage of the genome. However, with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, development of large numbers of molecular markers in the genome such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), insertion deletions (InDels), single sequence repeat (SSR) and other useful genes even in complex polyploidy crop such as sugarcane has become possible. Hence, NGS along with GWAS has increased the mapping resolution of the genome for the precise location of alleles/genes/QTLs (Varshney et al. 2014). It has allowed easy selection and rapid identification of novel genes from the germplasm and their incorporation into the desired breeding lines.

Table 8.

List of genes for abiotic stress tolerance in sugarcane crop

| Name of gene | Abiotic stress | Methodology | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs responsive to stress (ssp-miR164, ssp-miR394, ssp-miR397, ssp-miR399-seq 1 and miR528) | Drought | Transcriptomics | Ferreira et al. (2012), Gentile et al. (2013), Lin et al. (2014), Thiebaut et al. (2012) |

| Sugarcane drought-responsive (Scdr 1) | Drought, salinity and oxidative | Transcriptomics | Begcy et al. (2012) |

| miR159- MYB protein | Salinity | Transcriptomics | Carnavale-Bottino et al. (2013) |

| miR169-HAP12-CAAT-Box TFs | |||

| Sugarcane dirigent protein gene (ScDir) | Drought, salinity and oxidative | Transcriptomics | Jin-long et al. (2012) |

| SspNIP2 | Cold stress | Transcriptome analysis | Park et al. (2015) |

| P5CS |

Osmotic adjustment and Oxidative stress |

Transgenic | Hugo et al. (2007) |

| Trehalose synthase | Drought and salinity | Transgenic | Zhang et al. (2006) |

| Ethylene responsive factor | Drought | Transgenic | Trujillo et al. (2009) |

| Drought-responsive factor | Drought | Transgenic | Begcy et al. (2012) |

| Arabidopsis Vacuolar Pyrophosphatase (AVP 1) | Drought and salinity | Transgenic | Kumar et al. (2014) |

| Erianthus arundinaceus DREB2 (EaDREB2), pea DNA helicase 45 (PDH45) and HSP 70 | Drought and salinity | Transgenic | Augustine et.al. (2015a, b, c) |

| Sugarcane MYB | Drought | Transgenic | Shingote et al. (2015) |

| Arabidopsis vacuolar H + -pyro-phosphatase (H + PPase) | Drought | Transgenic | Raza et al. (2016) |

| Sugarcane ethylene responsive factor(SodERF3) | Drought and salt | Transgenic | Trujillo et al. (2009) |

| Ss NAC23 (up regulated) | Cold stress | cDNA arrays | Nogueira et al. (2003) |

| BcZAT12 | Drought and Salinity | Transgenic | Saravanan et al. (2018) |

| Lipoxygenase (ScLoX), Dehydrin | Drought stress | Microarrays and RNA sequencing | Andrade et al. (2014) |

| Sugarcane MYB (SoMYB18) | Salt and dehydration | Transcription factor | Shingote et al. (2015) |

| ScAPX6,ScNsLTP | Methyl jasmonate (MeJA), copper (Cu) and abscisic acid (ABA); drought and chilling | CRISPR/Cas9 | Chen et al. (2017), Liu et al. (2018) |

| PYL 1 | Water logging | CRISPR/Cas9 | Miao et al. (2018) |

aHSP Heat Sock Protein, DREB2 Dehydration responsive element binding protein, MYB transcription factors are defined by a highly conserved MYB DNA-binding domain (DBD) at the N-terminus, SspNIP2 = a S. spontaneum homolog of a NOD26-like major intrinsic protein gene, P5CS = Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase, is the rate-limiting enzyme in proline (Pro) biosynthesis, PYL1 = pyrabactin resistance 1, BcZAT12 = gene isolated form Brassica, confers salinity and drought tolerance

The advanced tools and techniques in plant biotechnology not only facilitates the study of genetic diversity, germplasm characterization and management, but also further enhances the sugarcane germplasm and its use. Furthermore, these tools enable the identification of useful molecular markers linked to genes and QTLs, using various techniques such as bulked segregant analysis, fine genetic mapping, or AM. New markers will be used for MAS, including marker-assisted backcrossing, ‘breeding by design’, or new strategies such as allelic selection/GS. In brief, advances in genomics are providing breeders with new tools and methodologies that allow a great leap forward in plant breeding, including the ‘super-domestication’ of crops and genetic dissection for complex traits.

NGS-based transcriptome sequencing (RNAseq) made the identification of thousands of SNPs from coding regions of the genomes easy (Dharshini et al. 2016, 2018; Cardoso-Silva et al. 2014). The development of SNP markers involves the discovery of SNPs, through whole-genome/transcriptome sequencing, sequencing of the targeted genomic region, or in silico SNP mining, and validation of the discovered SNPs through various genotyping techniques. The advent of NGS technologies has revolutionized the way crop genomes are sequenced by drastically cutting down the costs, mainly by bypassing tedious traditional cloning techniques and by their ability to perform several sequencing reactions in parallel. Second-generation sequencing platforms such as the 454 and Illumina (Illumina, https://www.illumina.com) have been commonly used for sequencing whereas Solid (Applied Biosystems, https://www.appliedbiosystems.com/technologies) has been less exploited in plants. More recently, the third-generation sequencing platforms such as Pac Bio RS (Pacific Biosciences, https://www.pacificbiosciences.com), Helicos (Helicos, https://www.helicosbio.com), and Ion Torrent (Life Technologies, https://www.iontorrent.com) are being extensively used. With the help of these sequencing platforms, several genomics-based databases are now available to identify gene sequences that would help in the development of molecular markers for useful traits.

Transgenic approach to enhance the abiotic stress tolerance in sugarcane

Sugarcane cultivation is affected by both biotic stresses (pathogen and insect pests) and abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, waterlogging, high/low temperature, nutrient deficiencies, heavy metals, etc. These stresses not only widen the gap between the mean yield and the potential yield, but also cause yield instability in agriculturally important crops. Of the many factors affecting sugarcane production, drought is one of the main factors that restrict sustained sugarcane production. It is a rainfed crop, which depends heavily on the amount and duration of precipitation, humidity, moisture content, temperature, and soil condition (Gawander 2007). During its 360 days of growth, the water demand is high (1000–1500 mm). Development of sugarcane plant is divided into four distinct phases i.e. germination, tillering, grand growth, and maturity. Tillering and grand growth phases are most susceptible to water stress. Ironically, these phases are also critical for sugarcane productivity. During these critical phases, water stress directly affects the final yield through the reduction of growth, dry matter accumulation, cane yield, and juice quality. Due to this, the shortage of water adversely affects the crop yield. Climate change is also predicted to affect most severely where agricultural systems are most vulnerable to climatic conditions. Water stress will be seriously aggravated if global warming, as predicted, exerts in the near future, resulting in a negative effect on sugarcane production in the tropical and subtropical regions. Under these situations, the genetic engineering technique was used to develop transgenes for different traits. Many studies have shown that transfer of stress-responsive genes to susceptible genotype could increase tolerance in host to various abiotic stresses (Table 7). The encouraging results of imparting tolerance through transferring stress tolerance genes for management of various abiotic stresses in various agricultural crops, shows that there is a lot of scope to explore and tap the potential of those novel genes to manage biotic and abiotic stresses, and enhance the yield of sugarcane.

Role of microRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs of usually 20–24 nucleotides length, which act as regulators of genes at post-transcriptional levels in the number of plant species. The function of some of the miRNAs which are regulated by different stresses is functionally conserved across plant species. These miRNAs mediate the responses by modulating the amount of themselves, the number of mRNA targets, or the activity/mode of action of miRNA–protein complexes (Ferdous et al. 2015; Swapna and Kumar 2017). In plants, the drought responsiveness of miRNAs is species dependent. It has also been studied that even members of the same family respond differently to drought stress. Zhou and Hong (2014) reported that in bentgrass, drought stress down- and up- regulates members of the miR319 family. The same miRNA in the same plant species can show different responses to drought depending on the real-time conditions. Until today, in sugarcane, of all the reports that analyzed miRNA expression in response to stresses, only a few have implicated miRNAs that are related to abiotic stress (Ferreira et al. 2012; Thiebaut et al. 2012; Gentile et al. 2013). Ferreira et al. (2012) identified 18 miRNAs families by deep sequencing of small RNAs. Seven of the miRNAs were differentially expressed during drought. Six of these miRNAs were differentially expressed at two days of stress, and five miRNAs were differentially expressed at four days. The expression levels of five miRNAs were validated by RT-qPCR. Also, six precursors and the targets of the differentially expressed miRNAs were identified using an in silico approach. miRNA expression under drought stress in sugarcane suggests that plants miRNA expression may adjust their micro-transcriptome in different ways to overcome different phases and intensity of drought stress and these responses may vary in different genetic backgrounds (Gentile et al. 2013). Differential miRNA mediated regulation in sugarcane for salinity and response to pathogens have been reported by some researchers (Patade and Suprasanna 2010; Carnavale-Bottino et al. 2013). There were more than 240 miRNAs that influenced the Acidovorex avenae ssp avenae infections in sugarcane (Thiebaut et al. 2012). Viswanathan et al. (2014) identified the miRNA of Sugarcane Streak Mosaic Virus (SCSMV) and its potential target gene in the sugarcane host plant. Several miRNAs have been identified in sugarcane crop and they are presumed to have a role in regulating the various metabolic processes (Swapna and Kumar 2017).

Sugarcane monoploid reference genome: a tool for abiotic stress management at the genome level

Sugarcane cultivars over the world are interspecific derivatives and highly polyploid with 100–130 chromosomes. About 70–80% of the genome is derived from S. officinarum, 10–20% from the wild species of S. spontaneum, and ~ 10% from interspecific recombinants (D’Hont et al. 1998; Piperidis et al. 2010). This polyploidy results in a total genome size of about 10 Gb for sugarcane cultivars, while the monoploid genome size is about 800–900 Mb (750 Mb) (D’Hont and Glaszmann 2001). Eventhough sugarcane is being considered as an economically important plant, not much genome-based research has been carried out by the scientists due to its large and complex genome. More recently, a mosaic monoploid reference sequence for the highly complex genome of sugarcane has been successfully generated (Garsmeur et al. 2018). This whole‐genome resequencing (WGR) is expected to address fundamental evolutionary biology questions that have not been fully resolved using traditional methods. Moreover, WGR offers an unprecedented marker density and surveys a wide diversity of genetic variations not limited to single nucleotide polymorphisms (e.g., structural variants and mutations in regulatory elements), but increasing their power for the detection of signatures of selection and local adaptation as well as for the identification of the genetic basis of phenotypic traits and diseases (Fuentes‐Pardo and Ruzzante 2017).

Genome editing: a new tool for sugarcane improvement

Genome editing is a new editing tool in which sequence-specific double-strand breaks (DSB) are created by nuclease to insert, delete, or replace the DNA at the desired location in the genome. These breaks are repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology recombination (HR), resulting in targeted mutations. Out of four category nucleases—mega nucleases, ZFNs, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas9, the latest one viz., CRISPR/Cas9 technology has emerged as a new tool to modify the sugarcane genome, due to its effectiveness and ability to overcome the transgene-silencing problem in sugarcane. Using this system, several useful genes for many important agronomical traits can be manipulated easily even at several sites. Recently, a TALEN (transcription activator-like effector nuclease) mediated genome editing was successfully employed in sugarcane by Jung and Altpeter (2016). TALEN mediated mutations in a highly conserved region of the caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) of sugarcane significantly reduces the lignin content in the cell wall which significantly improves the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass of sugarcane into ethanol. However, due to the complex genome, large genome size, highly polyploid and aneuploid nature, still possesses many challenges that need to be addressed to gain the complete usefulness of this technology. This could be a very effective system in a country where a complete indefinite moratorium on GM crop trials and their uses is focused. It would inevitably increase the interest of research to generate news, and desired traits modification in crops in the coming future.

Conclusion

Global climate change is predicted to pose a severe threat to agricultural productivity and challenge food and nutritional security worldwide. The technological advances in plant breeding particularly in molecular breeding, genomic-assisted breeding alongside transgene-based approach have undoubtedly facilitated the development of the cultivars tolerance to multiple stresses. Identification and characterization of miRNA/genes associated with a plant’s response to stress are crucial to the development of new cultivars with improved tolerance. The miRNAs associated with abiotic stresses such as salinity, drought, cold and waterlogging tolerance have been identified in sugarcane crop, even though to a much lesser extent due to non-availability of genome sequence information. However, the recent progress in monoploid genome sequencing in sugarcane makes it easy to decipher the genes and molecular markers associated with agronomic important traits, which is crucial for successful sugarcane breeding programs. The advent of the NGS along with advanced bioinformatics tools have expedited the discovery of novel genes and regulatory pathways involved in stress tolerance, undoubtedly leading to create an opportunity to evolve an invincible strategy for the improvement of sugarcane with durable resistance to abiotic stresses. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9 technology has emerged as a new tool to alter the sugarcane genome due to its effectiveness and precise editing of the genome to generate new varieties with specific desirable traits. Using this system, several genes, useful or harmful for many important agronomical traits can be manipulated easily. Although the impact of climate change on sugarcane is difficult to predict and is likely to be variable depending on the crop and environmental conditions, the overall view is that the genomic-assisted breeding could contribute significantly to reduce the impact of abiotic stresses on future scenarios of sugarcane cropping.

Acknowledgement

We thanks to Department of Science and Technology (DST-SERB, F.No EEQ/2018/000967), Indian Council of Agricultural Research and the Director, ICAR-Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, India for facilitating the required inputs. We also acknowledge the competent assistance of staff from ICAR-SBIRC, Karnal for helping in manuscript drafting.

Author contributions

Conceptualization of research article (BR, RK, MRM); Preparation of manuscript (MRM, BR, RK, CA, NK); and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical statements

The manuscript has not been submitted to any other journal for consideration.

References

- Almeida MRM, Serralheiro RP. Soil salinity: effect on vegetable crop growth management practices to prevent and mitigate soil salinization. Horticulturae. 2017;3:30. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae3020030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allakhverdiev SI, Kreslavski VD, Klimov VV, Los DA, Carpentier R, Mohanty P. Heat stress: an overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2008;98:541–550. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LM, Benatti TR, Nobile PM, Goldman MH, Figueira A (2014) Characterization, isolation and cloning of sugarcane genes related to drought stress. BMC Proc 8:110. https://www.biomedcentral.com/17536561/8/S4/P110

- Anderson PK, Cunningham AA, Patel NG, Morales FJ, Epstein PR, Daszak P. Emerging infectious diseases of plants: pathogen pollution, climate change and agro technology drivers. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous . Research achievements: 1912–1987. In: David H, editor. Platinum jubilee profile. Coimbatore, India: Sugarcane Breeding Institute; 1987. p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Arun KR, Vasantha S, Tayade AS, Anusha S, Geetha P, Hemprabha G. Physiological efficiency of sugarcane clones under water-limited conditions. Trans ASABE. 2020;63:133–140. doi: 10.13031/trans.13550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine SM, Ashwin NJ, Syamaladevi DP, et al. Overexpression of EaDREB2 and pyramiding of EaDREB2 with the pea DNA helicase gene (PDH45) enhance drought and salinity tolerance in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:247–263. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1704-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine SM, Ashwin NJ, Syamaladevi DP. Introduction of pea DNA helicase 45 into sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid) enhances cell membrane thermostability and upregulation of stress-responsive genes leads to abiotic stress tolerance. Mol Biotechnol. 2015;57:475–488. doi: 10.1007/s12033-015-9841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine SM, Ashwin NJ, Syamaladevi DP. Erianthus arundinaceus HSP70 (EaHSP70) overexpression increases drought and salinity tolerance in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid) Plant Sci. 2015;232:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basnayake J, Jackson PAN, Inman-Bamber G, Lakshmanan P. Sugarcane for water-limited environments. Genetic variation in cane yield and sugar content in response to water stress. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:6023–6033. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basnayake J, Jackson PA, Inman-Bamber NG, Lakshmanan P. Sugarcane for water-limited environments Variation in stomatal conductance and its genetic correlation with crop productivity. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:3945–3958. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begcy K, Mariano ED, Gentile A, Lembke CG, Zingaretti SM, Souza GM. A novel stress-induced sugarcane gene confers tolerance to drought, salt and oxidative stress in transgenic tobacco plants. PLoS ONE. 2012;79:44697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begcy K, Mariano ED, Gentile A, Lembke CG, Zingaretti SM, Souza GM, Menossi M. A novel stress-induced sugarcane gene confers tolerance to drought, salt and oxidative stress in transgenic tobacco plant. PLoS ONE. 2016;12:25698. doi: 10.1038/srep25698PMCID:PMC4864372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belesini A, Carvalho F, Telles B, De Castro G, Giachetto P, Vantini J, Carlin S, Cazetta J, Pinheiro D, Ferro M. De novo transcriptome assembly of sugarcane leaves submitted to prolonged water-deficit stress. Mol Res Genet. 2017 doi: 10.4238/gmr16028845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan SA, Croft BJ, Deomano EC, James RS, Stringer JK. Mechanism of resistance in Australian sugarcane parent clones to smut and the effect of hot water treatment. Crop Pasture Sci. 2013;64:892–900. [Google Scholar]

- Blum A. Drought resistance, water-use efficiency, and yield potential—are they compatible, dissonant, or mutually exclusive? Crop Pasture Sci. 2005;56:1159–1168. doi: 10.1071/AR05069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo D, Rodriguez P, Morales MA, Dell’amico JM, Torrecillas A, Alarcon JJ. High temperature effects on photosynthetic activity of two tomato cultivars with different heat susceptibility. J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnavale-Bottino M, Rosario S, Grativol C, Thiebaut F, Rojas CA, Farrineli L, et al. High-throughput sequencing of small RNA transcriptome reveals salt stress regulated microRNAs in sugarcane. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Silva CB, Costa EA, Mancini MC, Balsalobre TWA, Costa-Canesin LE, Pinto LR. De novo assembly and transcriptome analysis of contrasting sugarcane varieties. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e88462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wang Z, Ni H, Xu Y, Chen Q, Jiang L. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base-editing system efficiently generates gain-of-function mutations in Arabidopsis. Sci China Life Sci. 2017;60:520–523. doi: 10.1007/S11427-017-9021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements HF (1980) Sugarcane crop logging and crop control: Principles and practices, University Press Hawaii, Honolulu pp. 540, Cab Direct, ISBN: 0824805089 https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19806734631

- D’Hont A, Ison D, Alix K, Roux C, Glaszmann JC. Determination of basic chromosome numbers in the genus Saccharum by physical mapping of ribosomal RNA genes. Genome. 1998;41:221–225. doi: 10.1139/g98-023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hont A, Glaszmann JC. Sugarcane genome analysis with molecular markers, a first decade of research. Proc Int Soc Sugarcane Technol. 2001;24:556–559. [Google Scholar]

- D’Hont A, Souza A, Menossi GM, Vincentz M, Van M, Sluys MA, Glaszmann JC, Ulian E. Sugarcane: A major source of sweetness, alcohol, and bio-energy. In: Moore PH, Ming R, editors. Genomics tropical crop plants. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 483–513. [Google Scholar]

- Dharshini S, Chakravarthi M, Ashwin Narayan J, Manoj VM, Naveenarani M, Kumar R, Meena MR, Ram B, Appunu C. De novo sequencing and transcriptome analysis of a low temperature tolerant Saccharum spontaneum clone IND 00–1037. J Biotech. 2016;231:280–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharshini S, Chakravarthi M, Dhandapani V, Nerkar Gauri, Narayan JA, Mohanan VM, Naveenarani M, Lovejot K, Mahadevaiah C, Kumar R, Meena MR, Ram B, Appunu C. Differential gene expression profiling through transcriptome approach of Saccharum spontaneum L. under low temperature stress reveals genes potentially involved in cold acclimation. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:195. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1194-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharshini S, Hoang NV, Mahadevaiaha C, Sarath Padmanabhana TS, Alagarasanc G, Sureshad GS, Ravinder K, Meena MR, Bakshi R, Appunua C. Root transcriptome analysis of Saccharum spontaneum uncovers key genes and pathways in response to low-temperature stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2020;171:103935. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.103935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Earle FS. Sugarcane and its Culture. New York: John Wiley; 1928. pp. 1–355. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer D S, Mackay TFC (1996) Introduction to Quantitative Genetics (4th ed.), Longman, ISBN 9780582243026, London

- Farooq M, Basra S, Wahid A, Cheema Z, Cheema M, Khaliq A. Physiological role of exogenously applied glycinebetaine to improve drought tolerance in fine grain aromatic rice (Oryza sativa L.) J Agron Crop Sci. 2008;194:325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2008.00323.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernanda CC, Marcos NM, SilveiraJoão B, Alexandra MCHF, SawayaPaulo ER, MarchioriEduardo C, MachadoGustavo M, SouzaMarcos GA, Landell Rafael V, RibeiroChaves, Drought tolerance of sugarcane is improved by previous exposure to water deficit. J Plant Phyisol. 2018;223:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous J, Hussain SS, Bu-Jun S. Role of microRNA s in plant drought tolerance. Plant Biotech J. 2015;13:293–305. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira TH, Gentile A, Vilela RD, Costa GG, Dias LI, Endres L, et al. microRNAs associated with drought response in the bioenergy crop sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira THS, Tsunada MS, Bassi D, Araújo P, Matiello L, Guidelli GV. Sugarcane water stress tolerance mechanisms and its implications on developing biotechnology solutions. Front Plant Sci. 2017;18:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01077/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO] The Impact of Disasters and Crises on Agriculture and Food Security. Rome: FAO; 2017. p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Franke KR, Schmidt SA, Park S, Jeong DH, Accerbi M, Green PJ. Analysis of Brachypodium miRNA targets: evidence for diverse control during stress and conservation in bioenergy crops. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):547. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4911-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara S, Terajima Y, Irei S. Identification and characterization of intergeneric hybrid of commercial sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid) and Erianthus arundinaceus (Retz) Euphytica. 2013;189:321. [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Barrera-Figueroa BE, Juntawong P, Peña-Castro JM. Submergence and waterlogging stress in plants: a review highlighting research opportunities and understudied aspects. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:340. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Pardo AP, Ruzzante DE. Whole-genome sequencing approaches for conservation biology: Advantages, limitations and practical recommendations. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:5369–5406. doi: 10.1111/mec.14264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsmeur O, Droc G, Antonise R, et al. A mosaic monoploid reference sequence for the highly complex genome of sugarcane. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2638. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawander J. Impact of climate change on sugar-cane production in Fiji. World Meteorol Organiz Bull. 2007;56:34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile A, Ferreira TH, Mattos RS, Dias LI, Hoshino AA, Carneiro MS, et al. Effects of drought on the microtranscriptome of field-grown sugarcane plants. Planta. 2013;237:783–798. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1795-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowacka K, Ahmed A, Sharma S, Abbott T, Comstock JC, Long SP. Can chilling tolerance of C4 photosynthesis in Miscanthus be transferred to sugarcane? Glob. Change Biol Bioenergy. 2016;8:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Gomathi R, Chandran K, Rao PG, Rakkiyappan P. Effect of waterlogging in sugarcane and its management. Extension Pub: Published by The Director, Sugarcane Breeding Institute (SBI-ICAR), Coimbatore; 2010. p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Gomathi R, Gowri Manohari N, Rakkiyappan P. Antioxidant enzymes on cell membrane integrity of sugarcane varieties differing in flooding Tolerance. Sugar Tech. 2012;14:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Gomathi R, Gururaja Rao PN, Chandran K, et al. Adaptive responses of sugarcane to waterlogging stress: an over view. sugar Tech. 2015;17:325–338. doi: 10.1007/s12355-014-0319-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grivet L, Arruda P. Sugarcane genomes: depicting the complex genome of an important tropical crop. Curr Op Plant Bio. 2001;5:122–127. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M, Nahar K, Alam MM, Roychowdhury R, Fujita M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:9643–9684. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemaprabha G, Nagarajan R, Alarmelu S. Response of sugarcane genotypes to water deficit stress. Sugar Tech. 2004;6:165–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02942718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemaprabha G, Nagarajan R, Alarmelu S, Natarajan US. Parental potential of sugarcane clones for drought resistance breeding. Sugar Tech. 2006;8:59–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02943743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]