Abstract

Objectives

People increasingly search for health information through the media and make decisions about their health based on these health stories. The mainstream media, including newspapers, are often the first source for the public to obtain health information. This study aims to assess the health stories reported in the health edition of People’s Daily in 2019 with four tools of the Media Doctor Toolkit (MDT), which can be an effective tool to evaluate the quality of public health stories. Based on the results, we attempt to address the gap in media coverage in terms of reporting on public health issues, and promote media to display the image of medical staff objectively, both of which can improve relationship of doctors, nurses and patients.

Methods

A prospective quantitative analysis of the quality of health stories reported in the health edition of People’s Daily from 1 February to September 31, 2019 was conducted. Forty-eight articles were collected and divided into four groups according to the MDT standards. Four rating tools were adapted from the MDT to assess the quality of the groups with corresponding criteria.

Results

Forty-eight unique health stories were assessed with four MDT rating tools. The mean total satisfactory score was 80%. Health advice had the highest average satisfactory score, 84%, compared with health policy group and public health problems and their solutions, at 80% and 77%, respectively. Health news group had the lowest score at 73%.

Conclusion

This study provides a description of the quality of health stories on People’s Daily. The overall quality of People’s Daily was fairly good, although there was a wide range of quality between groups. The health edition of People’s Daily covers a wide range of health topics such as new medical methods, doctor-patient relationship, advanced nursing practice, lifestyle change of health promotion etc. which promote excellence in providing the latest health information, representing medical staff image, resolve the disharmonious factors in the relationship between doctors and patients, and creating a good medical environment for the public. The findings of this study also provide insight into problems in health reporting of People’s Daily.

Keywords: Communication, Health policy, Newspaper article, Public health, Physician-patient relations, Media doctor toolkit

What is known?

-

•

The media are a key civil society stakeholder in efforts to address the challenges of public health across the globe. The definitive role that the media play at different levels in shaping public sentiment, mobilizing positive public participation and creating awareness is well known.

-

•

The media play an important role in health issues since people search for health information to make decisions. Health stories reported in the media influence the public and even policy makers.

-

•

There are skill/knowledge gaps among journalists and doctors in understanding public health and health information. Moreover, very little literature or tools are available for the public in terms of health story assessments in China.

What is new?

-

•

Effort should be made to increase the accuracy and completeness of health stories and, subsequently, health literacy among journalists and media consumers.

-

•

In China, there are many health stories in the mainstream media, and they are subjected to formal evaluation. The Media Doctor Toolkit provides four useful tools to address these subjects. Although two of these tools have yet to be formally evaluated and will undoubtedly be modified, in the process of being refined, they will provide insight into the overall quality of health stories in Chinese media.

-

•

The findings show that there are some knowledge gaps among health reporters, doctors and the public. It would be helpful to improve health literacy among journalists and media consumers.

1. Introduction

Most people obtain health information through the media and make decisions about their health based on these health stories. It is important that media coverage of public health stories is comprehensive and accurate. The media play a vital role in public health as information providers, health promoters and problem solvers. It is therefore unsurprising that there is a general expectation for the media to provide accurate and comprehensive information. Advocating a “conservative, careful approach to health and medical reports” is an important ethical obligation of media outlets.[1].

However, the media do not always perform as well as they should. Until recently, the quality of health reporting in most media has remained poor. In recent years, many scholars have noted this issue and attempted to identify possible ways to assess health stories and improve the quality of health reporting. To some extent, this situation is changing with the efforts of scholars, reporters and even media consumers. Western scholars started earlier in the quality evaluation of media health stories and formed a series of relatively complete evaluation standards that were successfully used in the United States, Canada, Australia, Britain, Japan, Iran and other countries. In 2000, Ray Moynihan and Lisa Biro analyzed 180 newspaper articles and 27 TV reports on three drugs in the American media from 1994 to 1998. These reports demonstrate some problems in quantifying the efficacy, potential hazards and relationship of interest.[2] Alan Cassels and Merrilee A. Hughes [2] evaluated how reporters reported medical information by selecting five prescription drug stories in 24 Canadian daily newspapers. David E Smith and Amanda J Wilson [4] accessed health stories on cancer intervention from June 2004 to June 2009 on the websites of Australian doctors using 10 criteria of MDT. This was the first practical application of MDT, which has spread to half a dozen countries over the past several years.

The Media Doctor website (mediadoctor.org.au) was launched in 2004 with the aim of providing an objective analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the health stories that appeared in the Australian mainstream media. Media Doctor Australia has reviewed more than 1300 stories and provided feedback to journalists. Similar sites have been launched in Canada (www.mediadoctor.ca), the US (www.healthnewsreview.org) and Hong Kong of China (www.mediadoctor.hk/). This is a helpful tool to assess the quality of health stories. Wilson and Bonevski [5] analyzed more than 1200 stories in the Australian media, compared different types of media outlets and examined reporting trends over time. Two years later, Ashorkhani and Gholami [6] assessed Iranian media health reporting with the same method.

In China, there are many stories about public health problems and policies in the mainstream media, and this information has been subjected to formal assessment. In October 2017, Han Qide, a professor at Peking University and a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, gave a lecture on “Strengthening the Science of Health Communication” at Peking University. He proposed five basic characteristics of modern science: 1) fact-based; 2) falsifiable; 3) rational; 4) logical; 5) quantifiable. These five characteristics apply equally to health reporting in mainstream media, which should be complete and accurate. In his lecture, Han noted some problems in Chinese health stories, particularly in health reports in the Chinese mainstream media. He appealed to health reporters to improve their skills, including enhancing the scientific spirit, learning basic scientific methods, and understanding medicine and health, when reporting health news. Many studies have been conducted by Chinese scholars to assess the accuracy of health stories from multiple perspectives; however, there are still no effective tools to assess Chinese health stories.

Improving the overall health of society is the ultimate goal of the Healthy China Strategy, and the Chinese government has made great efforts to promote this process. The media have provided many health stories. With the development of communication technology, health information has become more accessible; however, mainstream media, including newspapers, are by far a more believable source. As one of the most authoritative newspapers in China, People’s Daily has reported health stories for many decades. Although publication sales of the newspaper are falling, it remains a trusted channel for health information for most Chinese people.

Health stories can be found on People’s Daily since its establishment, but the special issue on health news was launched only 20 years ago. On January 7, 2000, 10 health stories were reported in the 12th edition, and People’s Daily began a health edition. Constant changes have been made to this special edition, including the name, layout and content. In the first five years, the health stories reported in the health edition mainly focused on spreading health knowledge, sharing health stories and analyzing important health topics. In 2006, Chinese health care reform began to draw people’s attention, and the health edition changed its name to Medicine and Health to highlight health care reform issues. Currently, the health edition of People’s Daily is updated every two weeks in four main parts: 1) health focus, 2) doctor lectures, 3) shadowless lamp, and 4) medical news.

The media has not performed as well as expected because there are two major skill and knowledge gaps between health reporters and the public: 1) basic knowledge and understanding of health issues, health programs and concepts and 2) the skills required to present health stories that are credible, informational and easy to understand. Assessing the quality of health stories is important to address these gaps. The health edition of People’s Daily dedicates significant space to health stories, including articles written by medical doctors, dietitians, herbalists, psychologists and journalists. Assessing health stories on People’s Daily with MDT is helpful to obtain an understanding of the quality of health stories in mainstream Chinese media. Our findings provide insight into the quality of this medium and offer an initial step toward improving quality and raising awareness. In addition, this information can provide the public with skills to better assess a particular public health issue and to objectively weigh the pros and cons of media information.

In China, there are many stories about public health problems and policies in the media, but formal evaluations of these stories are lacking. The exploration of MDT practice in China allows information related to public health programming to be assessed and evaluated.[7] In addition, these findings can be used as a recommendation of MDT to health reporters to provide reporters with skills to better assess the available information on a particular public health issue and to make accurate reports. This information can help Chinese media consumers objectively weigh the pros and cons of media reporting on public health issues by eliminating skill/knowledge gaps. This article aims to promote media excellence in health information nursing and health care, through assessing quality of health reports. This study takes People’s Daily as a case study, which covers a wide range of topics such as nursing practice, doctor stories, latest health information, health advice and policy, seeking to enrich insight into health information provision, medical situation and practice, media image of medical staff, relationship of doctors, nurses and patients (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Historical process of People’s Daily health edition.

| Stage | Column name | Years | Publication time and frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging | Health Space-Time | 2000–2005 | Friday, biweekly |

| Growth | Science and Education | 2006–2007 | Thursday, weekly |

| Medicine & Health | 2008–2009 | Thursday, biweekly | |

| Maturation | Health space-time | 2010–2012 | Thursday, weekly |

| 2012–2018 | Friday, weekly | ||

| Health | 2018–2019 | Friday, biweekly |

2. Methods

2.1. Instrument and measurements

The Media Doctor Toolkit (MDT) is used to help people assess the quality of health stories appearing in the media and to provide feedback through a joint review by journalists and public health professionals. The original Media Doctor tool was designed by a group of Australian academics and clinicians to evaluate health news about new treatments. With improvements by scholars in Canada, America and India in the following years, the MDT used today has 4 evaluation tools for 1) health news, 2) health advice, 3) health policy, and 4) public health problems and solutions (Table 2). Criteria ranging from 6 to 10 are included in each of the MDT tools. For each health article, the criterium are scored as “satisfactory”, “not satisfactory” or “not applicable” if a criterium is not relevant. Scores are assigned by each reviewer based on a scoring guide (Appendix A).

Table 2.

Four evaluation tools of the MDT.

| Tool No. | Category | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Tool 1 | Health news | Stories in the mainstream media about the treatment, prevention or diagnosis of disease in humans that have been the subject of recent research and that have the potential to influence behavior. |

| Tool 2 | Health advice | Stories providing advice about the treatment or prevention of specific illnesses for individuals as opposed to populations. |

| Tool 3 | Health policy | New policies or changes to old policies in the provision of services for the prevention or treatment of illness |

| Tool 4 | Public health problems and their solutions | Stories about what is actually happening in the field of public health, including stories about the social determinants of health |

It should be noted that the MDT does not include story headlines in the assessment because these are usually written by subeditors rather than by the journalists who wrote the stories. However, because the feedback aims to improve both editorial practice and the practices of journalists, it is appropriate for MDT raters to include a comment on the accuracy and appropriateness of story headlines, if indicated. In addition, it is important to remember when rating that it is the news story that is being evaluated, not the policy, the advice, or the research itself.

Tool 1 is for assessing health news stories about the treatment, prevention or diagnosis of disease in humans that have been the subject of recent research and that have the potential to influence behavior. This tool is the original MDT tool. It has been validated in Australia and widely used internationally for more than 10 years. Stories are eligible for review if they are published in the mainstream print or electronic media and report on the treatment, prevention or diagnosis of disease in humans. We used tool 1 to assess health news in the health edition of People’s Daily.

Tool 2 is used to assess health stories providing advice about the treatment or prevention of specific illnesses for individuals as opposed to populations. It was used by Amanda Wilson and David Smith [7] in 2017 to evaluate the health advice published in popular Australian lifestyle magazines.

Tool 3 is to evaluate stories about new health policies or changes to old policies. The tool we used has only 6 items, which is a simplification of John Lister’s 10-point tool. Furthermore, it is not suitable for assessing stories that merely recount that a policy is being developed or considered. Notably, this tool should not be used to evaluate commentaries on health policy authored by stakeholders or professional policy makers. The stories must be written by a journalist to critically evaluate the actual health policy.

Tool 4 is for the evaluation of stories about public health problems and their solutions, which are about what is actually happening in the field of public health, including stories about the social determinants of health. It has not been formally validated in Australia or in India but has been used successfully in workshops in India with respect to stories about aspects of immunization.

Both tool 1 and 2 have been validated in Australia and India, widely used internationally. Tool 3 and 4 have not been formally validated, but have been used successfully in workshops in India. We used tool 3 and tool 4 to assess health policy and health problems and solutions reported on People’s Daily, for trying to verify them in China.

2.2. Data collection

Fifty-one news stories were reported in the health edition of People’s Daily between 1 February and September 31, 2019, which covered a variety of health information including health advice, new drugs, health policies and doctor stories. For this section, all these health stories were collected and reviewed (since 3 health stories that did not meet any standards of MDT were eliminated, our total sample was 48). These 48 health stories were divided into four groups according to the classification standards of the MDT. Among these, 6 health stories were categorized as health news, 9 health stories were categorized as health advice, 14 health stories were categorized as health policy, and 19 health stories were categorized as public health problems and their solutions. The four tools were applied to assess these four groups correspondingly.

2.3. Data analysis

Individual health stories were assessed by two raters. The raters rated stories independently of each other using validated rating tools with criteria. Stories were rated as “satisfactory” (S), “unsatisfactory” (US), or “not applicable” (NA) in each criterium. Scores were expressed as percentages of the total assessable items deemed satisfactory according to a coding guide. Regular face-to-face meetings were arranged so that all differences between raters in scores were resolved. We determined several types of scores in the study: an individual satisfactory score, an average satisfactory score, a group satisfactory score and a criterium satisfactory score. Agreement was achieved between raters regarding how the evaluation would be interpreted.

3. Results

Between 1 January and December 31, 2019, 48 health stories posted on the health edition of People’s Daily were assessed. Of these, 12.5% were about health news, 18.8% were about health advice, 29.2% were about health policy, and 39.6% were about public health problems and their solutions.

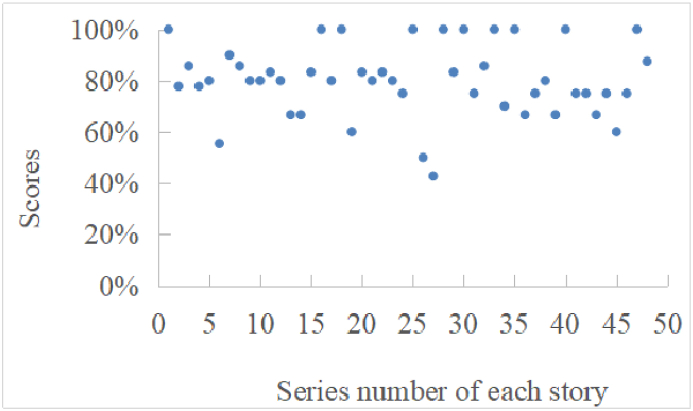

In particular, the average satisfactory score of health stories was 80%, which is relatively high. The satisfactory scores of individual health stories were distributed evenly on both sides of the mean line; the highest satisfactory score was 100%, and the lowest was 43%(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of scores for health stories.

3.1. Scores of the health news group

The health news group was assessed by Tool 1 and scored well on most items with average score of 74%. Specifically, it obtained full marks in criterium 2, 5 and 10 with 100% satisfaction. The satisfactory score of criterium 3 was the lowest at 20%, which was slightly lower than that of criterium 9 (40%). The satisfactory scores for three criteria, criterium 2, 5, and 10, ranged from 50% to 80% (Table 3, Table 4).

Table 3.

Satisfactory scores of health news group.

| Criteria | Scores (%) |

|---|---|

| Criterium 1: Is this treatment really new? | 83 |

| Criterium 2: Is the treatment available in China? | 100 |

| Criterium 3: Are alternative treatments mentioned? | 20 |

| Criterium 4: Is there evidence of disease mongering? | 50 |

| Criterium 5: Is objective evidence provided to support claims made? | 100 |

| Criterium 6: Are benefits expressed in absolute rather than relative terms? | 80 |

| Criterium 7: Are potential harms of the treatment mentioned? | 67 |

| Criterium 8: Are the costs of the treatment mentioned? | 60 |

| Criterium 9: Are the sources of information and potential conflicts of interest noted? | 40 |

| Criterium 10: Is the information in the headline consistent with that in the story? | 100 |

| Average score | 74 |

Table 4.

Satisfactory scores of health advice group.

| Criteria | Scores (%) |

|---|---|

| Criterium 1: The story recommended seeing a doctor (if applicable) | 75 |

| Criterium 2:The story was based on reliable evidence or on accepted medical practice | 78 |

| Criterium 3: The advice was clear and easily applied | 89 |

| Criterium 4: Benefits were presented in a meaningful way | 57 |

| Criterium 5: Potential harms were presented in a meaningful way | 33 |

| Criterium 6: The availability and costs of the intervention were noted | 78 |

| Criterium 7: The author had no apparent vested interests | 100 |

| Criterium 8:There was no obvious advertising | 100 |

| Criterium 9: Anecdotal evidence was used appropriately | 100 |

| Criterium 10: There was no evidence of disease mongering | 100 |

| Average score | 81 |

3.2. Satisfactory scores of the health advice group

The health advice group was assessed by Tool 2. The average score of this group was 81%. Four criteria received full marks. The satisfactory scores of four criteria ranged from 70% to 80%; the lowest was criterium 5, at 33%(Table 4).

3.3. Satisfactory scores of the health policy group

Fourteen health stories of the health policy group were assessed by Tool 3 for this group. Tool 3 is special because it has only 6 criteria. The difference in this group was not large. Specifically, criterium 2 and 6 obtained the highest score with a satisfactory score of 86%. criterium 5 was the lowest (75%), while the others were between them(Table 5).

Table 5.

Satisfactory scores of health policy group.

| Criteria | Scores (%) |

|---|---|

| Criterium 1: Is the story overly dependent on a press release? | 77 |

| Criterium 2: Does the story clearly state the objectives of this policy and what it is trying to achieve? | 86 |

| Criterium 3: Does the story clearly describe the evidence that this policy will achieve these objectives/has been used successfully elsewhere? | 82 |

| Criterium 4: Does the story clearly state how the outcomes will be measured? | 77 |

| Criterium 5: Does the story clearly state the potential unwanted outcomes? | 75 |

| Criterium 6: Does the story clearly state whether there are other ways of achieving these objectives/are alternative policies discussed? | 86 |

| Average score | 80 |

3.4. Satisfactory scores of public health problems and their solutions group

The Public health problems and their solutions group was assessed by Tool 4. There were no full marks in this group, in which the highest satisfactory score was 89% for criterium 10. The remaining satisfactory scores were approximately 80%, except for criterium 7 and criterium 9, both of which were 67%(Table 6).

Table 6.

Satisfactory scores of public health problems and their solutions group.

| Criteria | Scores (%) |

|---|---|

| Criterium 1: Is this a new problem or a new solution? | 79 |

| Criterium 2: Is a solution to this problem discussed? | 82 |

| Criterium 3: Have alternative solutions been suggested? | 71 |

| Criterium 4: Is there evidence of disease mongering? | 78 |

| Criterium 5: Is objective evidence provided to support claims made? | 81 |

| Criterium 6: Are risks, benefits and solutions expressed in absolute rather than in relative terms? | 85 |

| Criterium 7: Are potential costs of the problem mentioned? | 67 |

| Criterium 8: Are the costs of the solution to the problem mentioned? | 71 |

| Criterium 9: Are the sources of information and potential conflicts of interest noted? | 67 |

| Criterium 10: Is the headline consistent with the content of the story? | 89 |

| Average score | 77 |

4. Discussion

Of the results from 48 articles, 80% were assessed as “satisfactory”. However, there was a small range of quality between the groups, with the highest group of health advice at 83.75% and the lowest group of health news at 73%. The findings from this study show that the quality of health stories of People’s Daily was fairly high in 2019, although there were some poor scores for individual items.

Based on the results of this study, we identified some specific pros of People’s Daily reporting on health stories. For health news stories, 1) the treatment reported was always available in China, 2) the sources of information and potential conflicts of interest were noted, and 3) the information in the headlines was consistent with that in the stories. For health advice stories, 1) most were based on reliable evidence or on accepted medical practice, 2) advice was clear and easily applied, 3) there was no obvious advertising in all stories, 4) anecdotal evidence was used appropriately, and 5) there was no evidence of disease mongering. For health policy stories, 1) most stories clearly stated the objectives of the policies and clearly described the evidence suggesting that these policies would achieve these objectives or had been used successfully elsewhere, and 2) most stories clearly stated whether there were other ways of achieving these objectives. For public health problems and solutions, 1) most solutions to problems were discussed, 2) risks, benefits and solutions were expressed in absolute rather than in relative terms, and 3) most sources of information and potential conflicts of interest were noted.

On the other hand, this study showed that there are still some problems in People’s Daily health reporting. 1) The distribution of health stories in the four groups was uneven. Only 12.5% reports were health news, and approximately 40% reports were about public health problems and their solutions. 2) Alternative treatments, potential harms and costs of the treatments were not mentioned in many health news items. 3) Potential harms were not presented in a meaningful way in health advice. 4) Many stories did not clearly state potential unwanted outcomes, specifically for the group of health news items.

People’s Daily is not a professional health media for Chinese people; its reporters have limited skills to sift through the available information on a particular public health issue to tell health stories completely and accurately. However, People’s Daily is supported by the Chinese government, and there was no obvious advertising on most health stories, which is an important requirement of good health stories. Most reporters of health edition are doctors or professionals who are experienced in both treatment and reporting skills, so the nature and quality of evidence were stated correctly, and objective evidence was provided to support the claims made. In brief, People’s Daily did well in providing health advice and reporting health policy, while it performed poorly in terms of health news or public health problems and solutions. In addition, People’s Daily was generally successful in providing the public with complete and accurate information on public health issues.

Limitations of the study: Several limitations exist in the current study. First, a perfect evaluation tool does not exist. For MDT, tool 3 and tool 4 have yet to be formally validated and will undoubtedly be modified. Second, in this study, only health stories reported in People’s Daily in 2019 were analyzed, so the present samples were primarily limited to one newspaper and one year. Thus, our results cannot be extended to all the health stories in China, and improvements in story quality cannot be observed. Further studies are needed to evaluate more health reports from various media with diverse samples. Finally, there is no comparison between People’s Daily and other Chinese media, especially social media, which is increasing rapidly and is used by a growing number of people as a regular way to obtain health information. The next step should be to explore the possibility of analyzing health stories on social media with MDT.

5. Conclusions

The Media Doctor Toolkit provides an objective analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the health stories appearing in the mainstream media. This study mapped the overall quality of health reporting in People’s Daily in 2019. The findings are of great value for both reporters and media consumers since they can guide health reporters to consider the scientific factors of health stories and help the public to obtain a clearer picture of health stories with good quality. People’s Daily readers can be informed that the health information provided by this newspaper is relatively well presented and reliable.

The conclusions of this study were categorized into three main themes: 1) the findings are important features for the health stories reported in the health edition of People’s Daily; 2) accuracy and completeness were reflected very well in People’s Daily, especially in the groups of health news and public health problems and their solutions; 3) for health reporters of People’s Daily, the skills required to present health knowledge and information in a way that makes stories comprehensive, balanced and accurate still need to be improved.

The findings presented in this study present only a relatively brief picture of a limited media landscape in China. This study raises questions regarding the social responsibility of the media, including newspapers. Most journalists and public health providers believe that health is a special commodity that gives rise to particular social responsibilities.[8, 9] If the public has a right to know, it also has a right to be provided with information that is accurate and complete.[10] The findings presented here are important because newspapers, especially the government’s official newspapers such as People’s Daily, which is the organ of the Chinese Communist Party, are likely to be influenced by companies’ advertisements. This type of health information appearing in mainstream media should be presented as evidence based and current. At the same time, it is important to raise awareness and promote critical thinking among health consumers.

Many studies have examined the quality of health stories in mainstream media, but few, if any, have examined the quality of health information provided on social media or on the internet. This issue should be considered in future research because the number of people who use social media to obtain health information is increasing rapidly. However, the quality of many health stories presented on social media and the internet is poor because these sources lack information gatekeepers. In addition, future studies should attempt to formally evaluate tool 3 and tool 4 in China to provide insight into the overall quality of health policy and public health problems and their solutions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shiyu Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Linjie Dai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Jing Xu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association and MHM Committee.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.005.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Australian Press Council . Australian Press Council; 2001. Reporting guidelines. General press release No. 245. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moynihan R, Bero L, Ross-Degnan D, Henry D, Lee K, Watkins J. Coverage by the news media of the benefits and risks of medications. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(22):1645–1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006013422206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson A, Bonevski B, Jones A, Henry D. Media reporting of health interventions: signs of improvement, but major problems persist. PloS One. 2009;4(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson A.J., Bonevski B, Jones A.L., Henry D.A. Deconstructing cancer: what makes a good-quality news story? Med J Aust. 2010;193(11–12):702–706. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashorkhani M., Gholami J., Maleki K., Nedjat S., Mortazavi J., Majdzadeh R. Quality of health news disseminated in the print media in developing countries: a case study in Iran. BMC Publ Health. 2012;12(1):627. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson A., Smith D., Peel R., Robertson J., Kypri K. A quantitative analysis of the quality and content of the health advice in popular Australian magazine. Aust N Z J Publ Health. 2017;41(3):256–258. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vlassov V.V. Is content of medical journals related to advertisements? Case-control Study. Croat Med J. 2007;48(6):786–790. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2007.6.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moynihan R., Heath I., Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ. 2002;324(7342):886–891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordens C.F., Lipworth W.L., Kerridge I.H. The quality of Australian health journalism is important for public health. Med J Aust. 2013;199(7):448–449. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.