Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication and host immune response determine coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but studies evaluating viral evasion of immune response are lacking. Here, we use unbiased screening to identify SARS-CoV-2 proteins that antagonize type I interferon (IFN-I) response. We found three proteins that antagonize IFN-I production via distinct mechanisms: nonstructural protein 6 (nsp6) binds TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) to suppress interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) phosphorylation, nsp13 binds and blocks TBK1 phosphorylation, and open reading frame 6 (ORF6) binds importin Karyopherin α 2 (KPNA2) to inhibit IRF3 nuclear translocation. We identify two sets of viral proteins that antagonize IFN-I signaling through blocking signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)/STAT2 phosphorylation or nuclear translocation. Remarkably, SARS-CoV-2 nsp1 and nsp6 suppress IFN-I signaling more efficiently than SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Thus, when treated with IFN-I, a SARS-CoV-2 replicon replicates to a higher level than chimeric replicons containing nsp1 or nsp6 from SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV. Altogether, the study provides insights on SARS-CoV-2 evasion of IFN-I response and its potential impact on viral transmission and pathogenesis.

Keywords: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19, interferon, immune evasion, replicon

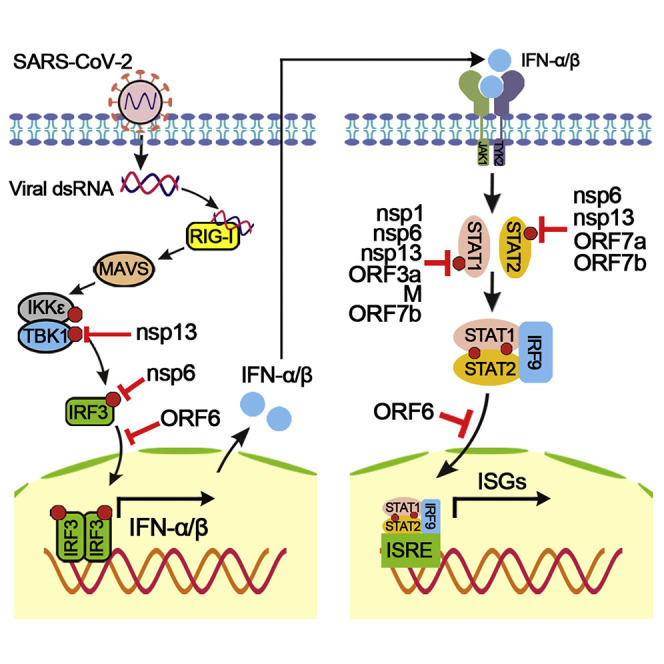

Graphical Abstract

Xia et al. perform an unbiased screening to identify SARS-CoV-2 proteins that antagonize the IFN-I response. The identified viral proteins inhibit IFN-I production and signaling through distinct mechanisms. Compared with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the IFN-I signaling is more efficiently suppressed by the SARS-CoV-2 nsp1 and nsp6 proteins.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and has led to a global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Zhou et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). As of July 4, 2020, there have been more than 11 million confirmed cases and more than 525,000 deaths in 6 months (Database: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/). Typical clinical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection range from mild-to-severe respiratory illness, including fever, dry cough, breathing difficulties, and acute respiratory distress, which may lead to long-term reduction in lung function and death (Wu and McGoogan, 2020). Before SARS-CoV-2, two other highly pathogenic coronaviruses emerged in the past two decades, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Assiri et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2020). In addition, four endemic human coronaviruses (i.e., OC43, 229E, NL63, and HKU1) cause common cold respiratory diseases. SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped β-coronavirus from the Coronaviridae family. It has a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA (Figure 1 A) that encodes 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1–16), 4 structural proteins (S [spike], E [envelop], M [membrane], and N [nucleocapsid]), and 7 accessory proteins (ORF3a, ORF3b, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF7b, ORF8, and ORF10). The nonstructural proteins make up the replicase, the structural proteins form the virion, and the accessory proteins modulate the host response to facilitate infection and pathogenesis. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of the virus and its host interactions is key to comprehending COVID-19 pathogenesis and transmission as well as developing diagnosis and countermeasures against these coronaviruses.

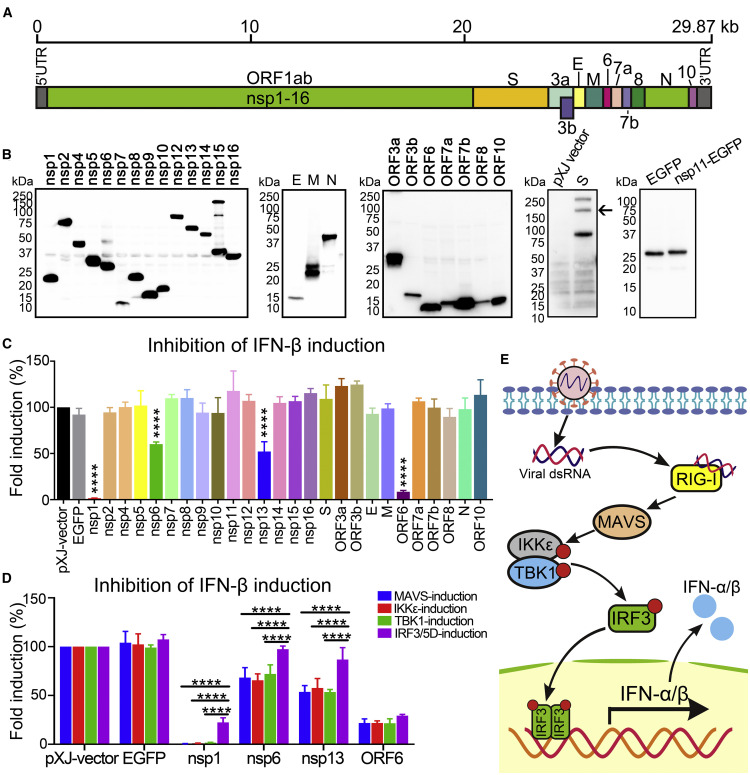

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Inhibit IFN-I Production

(A) Genome structure of SARS-CoV-2.

(B) Expression of SARS-CoV-2 proteins. C-Terminally FLAG-tagged viral proteins were expressed in HEK293T cells and analyzed by western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody. S protein was probed by anti-S antibody and is indicated by an arrow; an empty pXJ-plasmid-transfected cell lysate was included as a negative control. EGFP was fused to the C terminus of nsp11 and probed by anti-GFP antibody. All viral proteins were cloned from SARS-CoV-2 strain 2019-nCoV/USA_WA1/2020.

(C) IFN-β promoter luciferase assay. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with Firefly luciferase reporter plasmid pIFN-β-luc, Renilla luciferase control plasmid phRluc-TK, viral protein expressing plasmid, and stimulator plasmid RIG-I (2CARD). Empty plasmid and EGFP-encoding plasmid were used as controls. Cells were assayed for luciferase activity at 24 hpt. The data were analyzed by normalizing the Firefly luciferase activity to the Renilla luciferase (Rluc) activity and then normalized by non-stimulated samples to obtain fold induction. Empty vector control was set to 100%. Statistics were determined by comparing with EGFP control and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(D) MAVS-, IKKε-, TBK1-, or IRF3/5D-activated IFN-β promoter luciferase assay. The experiments were performed as in (C) except that the assay was activated by MAVS, IKKε, TBK1, or IRF3/5D. Data were from three independent experiments in triplicate (mean ± SD). Statistics were determined by comparing each respective IRF3/5D-induction group using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(E) Scheme of RIG-I-mediated IFN-I production pathway.

The innate interferon (IFN) response constitutes one of the first lines of host defense against viral infections. Upon infection, viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are first recognized by multiple host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), cytoplasmic DNA receptors, and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) (Acharya et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Meylan et al., 2006; Park and Iwasaki, 2020). Recognition of cognate ligands, such as viral RNA, triggers RIG-I to expose the caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD), and the CARD domain of RIG-I interacts with the CARD domain of the mitochondrial antiviral adaptor protein (MAVS). The activation of MAVS recruits multiple downstream signaling components to the mitochondria, leading to activation of the inhibitor of κ-B kinase ε (IKKε) and TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which in turn phosphorylate the interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). The phosphorylated IRF3 forms a dimer and translocates to the nucleus, activating the transcription of type I IFN (IFN-I) genes (Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2015). IFN-I induces antiviral activity in cells to eliminate viral replication, by inducing double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-activated kinase (Protein kinase R, PKR), 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), and RNase L (Balachandran et al., 2000; Malathi et al., 2007; Samuel, 2001). The secreted IFN-I (IFN-α and IFN-β) binds to the IFN receptors (IFNARs) and activates Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which phosphorylate signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STAT1 and STAT2) (Levy and Darnell, 2002). Phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2 form a heterodimer, which associates with IRF9 to form the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). ISGF3 translocates to the nucleus and binds to IFN-I-stimulated response elements (ISREs), triggering the expression of hundreds of ISGs with antiviral functions (Schneider et al., 2014; Schoggins et al., 2015).

Coronaviruses use various approaches to evade the host immune response, including antagonizing IFN production, inhibiting IFN signaling, and enhancing IFN resistance (Channappanavar and Perlman, 2017; Kindler et al., 2016; Totura and Baric, 2012). SARS-CoV nsp1, papain-like protease (PLpro), nsp7, nsp15, ORF3b, M, ORF6, and N proteins were documented to antagonize the IFN response (Frieman et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2017; Kamitani et al., 2006; Kopecky-Bromberg et al., 2007; Niemeyer et al., 2018; Siu et al., 2009). Mutant SARS-CoVs with a bat coronavirus PLpro substitution or ORF6 deletion were attenuated in IFN antagonism (Frieman et al., 2007; Niemeyer et al., 2018). SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a delayed IFN-I response (Lei et al., 2020). Indeed, a number of SARS-CoV-2 proteins were recently reported to antagonize the IFN response (Yuen et al., 2020). However, the antagonistic mechanisms of these viral proteins and their contributions to COVID-19 development and transmission are poorly understood. To address these important questions, we screened individual SARS-CoV-2 proteins for suppressors of IFN-I production and signaling. Individual suppressors were mapped to their inhibitory steps in the IFN-I production/signaling pathways. Importantly, we found that suppressors from MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 exhibited different IFN-I inhibitory activities, leading to different levels of viral replication. The results suggest that SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 use distinct antagonisms of IFN-I production and signaling to affect disease course and transmission efficiency.

Results

SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Antagonize IFN-β Production

We cloned all 27 genes of SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1A) to a mammalian expression plasmid pXJ. Individual viral proteins were expressed with a C-terminal FLAG tag to facilitate the detection of their expression (Figure 1B). Because of the small size of nsp11 (1.5 kDa), an EGFP tag was fused to the C terminus of nsp11. After being transfected into HEK293T cells, the plasmids expressed viral proteins of expected sizes (Figure 1B). Nsp3 was not sufficiently expressed and thus not included in the study (data not shown). To screen for SARS-CoV-2 proteins that could inhibit IFN-β production, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with four plasmids: (1) a plasmid expressing an individual viral protein, (2) a plasmid encoding a luciferase gene driven by the IFN-β promoter (pIFN-β-luc), (3) a plasmid expressing RIG-I-CARD (a constitutively active form of RIG-I and a well-established inducer of IFN production), and (4) a control plasmid pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] (phRluc-TK) for normalizing transfection efficiency. Empty pXJ-plasmid and pXJ-plasmid expressing EGFP were included as controls. At 24 h post-transfection (hpt), luciferase signals from the transfected cells were measured to quantify the IFN-β promoter activity (Figure 1C). Among the 26 viral proteins tested, 3 nonstructural proteins (nsp1, nsp6, and nsp13) and 1 accessory protein (ORF6) significantly inhibited luciferase activities (Figure 1C). Nsp1 and ORF6 were more potent and suppressed the luciferase activity by 98% and 91%, while nsp6 and nsp13 were weaker and suppressed the luciferase activity by 40% and 48%, respectively (Figure 1C).

To identify which steps of IFN-β production are inhibited by these four proteins, we screened distinct components of the RIG-I pathway (Figure 1E). The experimental approach was the same as described above, except that a plasmid expressing MAVS, TBK1, IKKε, or IRF3/5D (a phosphor-mimic of the activated IRF3) was transfected to activate a particular step of the RIG-I pathway. The results showed that nsp6 and nsp13 significantly suppressed luciferase activity when IFN-β promoter was activated by MAVS, TBK1, or IKKε (Figure 1D). By contrast, IRF3/5D led to significantly less suppression of luciferase expression, restoring luciferase activity from 60% to 98% for nsp6 and from 52% to 87% for nsp13. These results suggest that nsp6 and nsp13 antagonize IFN-β production by targeting IRF3 (before IRF3 activation) or another component upstream of IRF3 (between TBK1/IKKε and IRF3).

When nsp1 was tested, the luciferase suppression trend was similar to those observed with nsp6 and nsp13, except that IRF3/5D only restored the luciferase activity from <2% to 23% when MAVS, TBK1, or IKKε was used to activate the IFN promoter (Figure 1D). The results suggest that nsp1 may inhibit IFN-β production through multiple targets that are both upstream and downstream of IRF3. ORF6 inhibited luciferase activity to similar extents (∼30%) regardless of which activator was used (Figures 1D and 1E), suggesting that ORF6 suppresses IFN-β production through IRF3 or a component downstream of IRF3.

nsp6 and nsp13 Inhibit TBK1 and IRF3 Activation

The above-mentioned results prompted us to test whether nsp6, nsp13, and ORF6 modulate TBK1 phosphorylation and IRF3 phosphorylation, which are two key steps in the IFN-β induction pathway (Kato et al., 2006). We did not include nsp1 in this set of experiments because it has been well documented that SARS-CoV nsp1 suppresses host gene expression (including IFN-I) through mRNA degradation and translation inhibition (Huang et al., 2011; Kamitani et al., 2006, 2009; Narayanan et al., 2008). For analyzing IRF3 phosphorylation, HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing nsp6, nsp13, or ORF6. At 24 hpt, cells were treated with poly(I:C) (a dsRNA mimic) and analyzed for IRF3 phosphorylation (Figure 2 A). Nsp6 and nsp13 inhibited 57% and 75% of the IRF3 phosphorylation, respectively. By contrast, ORF6 did not significantly suppress the IRF3 phosphorylation (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Inhibit TBK1 and IRF3 Activation

(A) Analysis of IRF3 phosphorylation. HEK293T cells were transfected with viral protein-encoding plasmid (1 μg); treated with poly(I:C) (10 μg); and analyzed for phosphorylated IRF3 (anti-pIRF3 at S396), total IRF3 (anti-IRF3), viral protein (anti-FLAG), and GAPDH (anti-GAPDH) by western blot.

(B) Analysis of TBK1 phosphorylation. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with TBK1-expressing plasmid and varying amounts of nsp6- or nsp13-encoding plasmids. At 24 hpt, western blot was used to analyze the cell lysates for phosphorylated TBK1 (anti-pTBK1 at S172), total TBK1 (anti-TBK1), phosphorylated IRF3 (S396; anti-pIRF3), total IRF3 (anti-IRF3), viral nsp 6 or nsp13 (anti-FLAG), and GAPDH (anti-GAPDH). Protein band intensity was quantitated using Image Lab software.

(C) Co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) of TBK1 and nsp6 or nsp13. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing TBK1 and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged nsp6 or nsp13. At 24 hpt, whole-cell lysate (WCL) was incubated with anti-HA beads for immunoprecipitation and TBK1 was detected by western blot.

(D) Nuclear translocation of IRF3. A549 cells were transfected with ORF6-expressing plasmid. At 24 hpt, cells were treated with poly(I:C) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. After blocking with PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1% Tween 20, the cells were probed with primary antibodies (anti-FLAG and anti-IRF3) and secondary antibodies (anti-Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-Alexa Fluor 568). Images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope and analyzed by ImageJ. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) coIP of ORF6 and KPNA1–6. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with FLAG-tagged ORF6-expressing plasmid and HA-tagged KPNA1–6 plasmid or empty plasmid. At 24 hpt, coIP was performed by incubating anti-HA antibody overnight, followed by addition of magnetic beads. After extensively washing, the eluate was analyzed by western blot with indicated antibodies.

(F) Summary of antagonism of IFN-I production. The inhibitory steps are indicated for individual viral proteins.

Next, we examined the effect of nsp6 and nsp13 on TBK1 phosphorylation. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with one plasmid expressing TBK1 and another plasmid encoding either nsp6 or nsp13. At 24 hpt, cells were analyzed for TBK1 phosphorylation. Nsp13, but not nsp6, inhibited TBK1 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B). In agreement with the results from Figure 2A, both nsp6 and nsp13 suppressed IRF3 phosphorylation (Figure 2B). Furthermore, we examined whether nsp6 or nsp13 interacts with TBK1. Co-immunoprecipitation showed that both nsp6 and nsp13 could pull down TBK1 (Figure 2C). Collectively, the results indicate that (1) nsp6 binds to TBK1 without affecting TBK1 phosphorylation, but the nsp6/TBK1 interaction decreases IRF3 phosphorylation, which leads to reduced IFN-β production; and (2) nsp13 binds and inhibits TBK1 phosphorylation, resulting in decreased IRF3 activation and IFN-β production (Figure 2F).

ORF6 Inhibits Nuclear Translocation of IRF3

The results from Figure 1C suggest that ORF6 inhibits IFN-β production through IRF3 or a component downstream of IRF3. Thus, we examined the effect of ORF6 on IRF3 nuclear translocation. Upon poly(I:C) treatment, IRF3 translocated to the cell nucleus in the absence of ORF6, whereas the expression of ORF6 blocked its nuclear translocation (Figure 2D). Karyopherin α 1–6 (KPNA1–6) are importing factors for nuclear translocation of cargos, including IRF3, IRF7, and STAT1 (Chook and Blobel, 2001). Co-immunoprecipitation showed that ORF6 selectively interacted with KPNA2, but not the other KPNAs (Figure 2E), suggesting that ORF6 inhibits IFN-β production by binding to KPNA2 to block IRF3 nuclear translocation (Figure 2F).

SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Antagonize IFN-I Signaling

Although SARS-CoV-2 was reported to be highly sensitive to IFN-I inhibition (Xie et al., 2020a), it remains to be determined which viral proteins antagonize IFN-I signaling. We screened SARS-CoV-2 proteins in an IFN-I signaling assay using a plasmid (pISRE-luc) that contains a luciferase reporter driven by an ISRE promoter. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with three plasmids: (1) a reporter plasmid pISRE-luc, (2) a plasmid encoding an individual SARS-CoV-2 protein, and (3) a plasmid phRluc-TK for normalizing transfection efficiency. An empty plasmid or an EGFP-expressing plasmid was included as a negative control. At 24 hpt, cells were treated with IFN-α for 8 h and assayed for luciferase signals to quantify the activation of ISRE. Ten proteins significantly suppressed IFN-α signaling: nsp1, nsp6, nsp7, nsp13, nsp14, ORF3a, M, ORF6, ORF7a, and ORF7b (Figure 3 A).

Figure 3.

SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Block IFN-I Signaling

(A) ISRE promoter luciferase assay. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with an ISRE promoter-driven Firefly luciferase reporter plasmid pISRE-luc, Renilla luciferase control plasmid phRluc-TK, and viral protein expressing plasmid. At 24 hpt, cells were treated 1,000 U/mL IFN-α for 8 h, followed by dual-luciferase reporter assays. Data processing was the same as described in Figure 1. Error bars indicate SDs from three independent experiments. Statistical values were determined by comparing with EGFP control and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(B) Inhibition of STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation. HEK293T cells were transfected with viral protein expressing plasmids. At 24 hpt, cells were treated with 1,000 U/mL IFN-α for 30 min and analyzed by western blot using anti-phosphorylated STAT1 at Y701, anti-total STAT1, anti-phosphorylated STAT2 at Y690, and anti-total STAT2 antibodies. Protein band intensity was quantitated using Image Lab software.

(C) Nuclear translocation of STAT1. Vero cells were transfected with ORF6 expressing plasmids for 24 h, treated with 1,000 U/mL IFN-α for 30 min, fixed and permeabilized, and probed with anti-STAT1 and anti-FLAG as primary antibodies and anti-Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-Alexa Fluor 568 as secondary antibodies. Images were obtained through fluorescence microscope and analyzed using ImageJ. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Summary of antagonism of IFN-I signaling. The inhibitory steps are indicated for individual viral proteins.

We examined viral suppression of STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation. We analyzed nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, ORF3a, M, ORF6, ORF7a, and ORF7b because these proteins suppressed >40% of ISRE promoter activity (Figure 3A). HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding each respective SARS-CoV-2 protein, treated with IFN-α, and then analyzed for STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation (Figure 3B). The results indicate that (1) nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, ORF3a, ORF7b, and M inhibited STAT1 phosphorylation by 33%–46%, whereas ORF6 and ORF7a only marginally suppressed STAT1 phosphorylation; and (2) nsp6, nsp13, ORF7a, and ORF7b inhibited STAT2 phosphorylation by 33%–50%, whereas nsp1, ORF6, ORF3a, and M marginally suppressed STAT2 phosphorylation (Figure 3B). The collective data indicate that nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, ORF3a, M, ORF7a, and ORF7b suppress STAT1 and/or STAT2 phosphorylation, whereas ORF6 may inhibit a step downstream of STAT1/STAT2 phosphorylation.

Once phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2 form a heterodimer that interacts with IRF9, the STAT1/STAT2/IRF9 complex (i.e., ISGF3) translocates to the nucleus and activates the transcription of ISGs (Au-Yeung et al., 2013). Since SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 could bind to nuclear import KPNA2 (Figure 2E), we tested the hypothesis that ORF6 inhibits IFN-I signaling through blocking ISGF3 nuclear translocation. Vero cells were transfected with ORF6-expressing plasmid, treated with IFN-α, and analyzed by immunofluorescence. With neither ORF6 expression nor IFN-α treatment, STAT1 resided in the cytoplasm (Figure 3C, top panels); without ORF6 but with IFN-α treatment, STAT1 translocated to nucleus (middle panels); and with both ORF6 expression and IFN-α treatment, STAT1 remained in the cytoplasm (bottom panels). These results suggest that ORF6 inhibits IFN-I signaling by suppressing STAT1 nuclear translocation through ORF6/KPNA2 interaction.

Other than ORF6, we also tested nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, ORF3a, M, ORF7a, and ORF7b for STAT1 nuclear translocation. Consistent with their suppression of STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation, all these viral proteins suppressed nuclear translocation of STAT1 during IFN-I signaling (Figure S1). Taken together, SARS-CoV-2 inhibits IFN-I signaling through three approaches (Figure 3D): (1) nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, ORF3a, M, and ORF7b suppress STAT1 phosphorylation; (2) nsp6, nsp13, ORF7a, and ORF7b inhibit STAT2 phosphorylation; and (3) ORF6 blocks STAT1 nuclear translocation.

Comparison of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV Proteins in Antagonizing IFN-I Response

We compared the ability of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV proteins to antagonize IFN-I production and signaling. We focused on the corresponding antagonizing proteins (identified from SARS-CoV-2) in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. For IFN-I production, nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, and ORF6 from all three viruses (Figure S2; note that MERS-CoV does not encode ORF6) inhibited IFN-β promoter activation to comparable levels, except that MERS-CoV nsp6 did not show any inhibition (Figure 4 A).

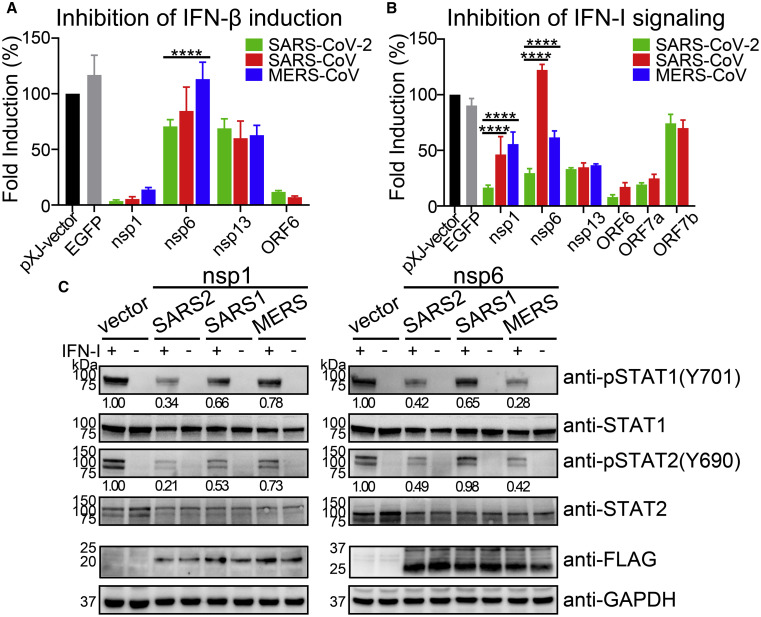

Figure 4.

Comparison of IFN-I Inhibition by Different Coronaviruses

(A) IFN-β promoter luciferase assay. Viral proteins from SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV/USA_WA1/2020, GenBank: MN985325), SARS-CoV (SARS MA15 strain, GenBank: DQ497008), and MERS-CoV (MERS EMC/2012 strain, GenBank: JX869059) were compared for their inhibition of IFN-I production. RIG-I-induced IFN-β promoter luciferase assay was performed by co-transfection of HEK293T cells as described in Figure 1.

(B) ISRE promoter luciferase assay. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pISRE-luc luciferase reporter plasmid, phRluc-TK control plasmid, and viral protein expressing plasmid. At 24 hpt, the cells were treated with 1,000 U/mL IFN-α and assayed for luciferase activities after 8 h. Error bars represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by comparing with SARS-CoV-2 and two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(C) Western blot of phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2. HEK293T cells were transfected with viral protein expressing plasmid and then treated with 1,000 U/mL IFN-α at 24 hpt for 30 min. Western blot was performed to analyze the cell lysates using anti-phosphorylated STAT1 (Y701) and STAT2 (Y690), and anti-total STAT1 and STAT2 antibodies. Protein band intensities were quantitated by Image Lab software.

For IFN-I signaling, we compared the inhibition by nsp1, nsp6, nap13, ORF6, ORF7a, and ORF7b among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV (Figure 4B). These proteins were chosen because they suppressed >50% of the IFN-α signaling in SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 3A). Compared with nsp1 and nsp6 of SARS-CoV-2, those of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV were significantly weaker in inhibiting IFN-α signaling, whereas comparable inhibition was observed for the other viral proteins among the three viruses (Figure 4B). Notably, SARS-CoV nsp6 did not suppress IFN-I signaling (Figure 4B). To confirm these results, we compared the effects of nsp1 and nsp6 from the three viruses on STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation (Figure 4C). The nsp1 of SARS-COV-2 was more efficient in suppressing STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation than that of SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV, whereas the nsp6 of SARS-CoV was less efficient in suppressing STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation than that of SARS-CoV-2 or MERS-CoV.

Altogether, the results suggest that (1) SARS-CoV-2 nsp6 inhibits IFN-I production more efficiently than MERS-CoV nsp6; (2) SARS-CoV-2 nsp1 is more efficient than those of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV to inhibit IFN-I signaling by blocking STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation; and (3) SARS-CoV nsp6 does not efficiently inhibit IFN-I signaling.

A Transient Luciferase Replicon for SARS-CoV-2

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) pathogen, we developed a luciferase replicon to facilitate studies of viral replication in BSL-2 laboratories. The replicon deleted nucleotides 21,563–28,259 from the viral genome, which was replaced with a gene cassette of Renilla luciferase (Rluc), foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A (FMDV 2A), and neomycin phosphotransferase (Neo; Figure 5 A). The deleted region includes S, E, M, and accessory genes ORF3a, ORF3b, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF7b, and ORF8. The engineered Rluc/FMDV 2A/Neo reporter was under the control of transcription regulatory sequence (TRS) of the deleted S gene (Figure 5A). Six sequential cDNA fragments were ligated to assemble the replicon DNA. A T7 promoter was engineered to transcribe the Rluc replicon (RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2) RNA in vitro. The sequence of RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 is shown in Figure S3. After electroporating the RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 RNA into Huh-7 cells, luciferase activity exponentially increased up to 12 hpt (Figure 5B), indicating robust viral replication. The luciferase signals plateaued at ∼8 × 103-fold above the background from 12 to 24 hpt and decreased after 24 hpt due to replicon-mediated cytotoxicity.

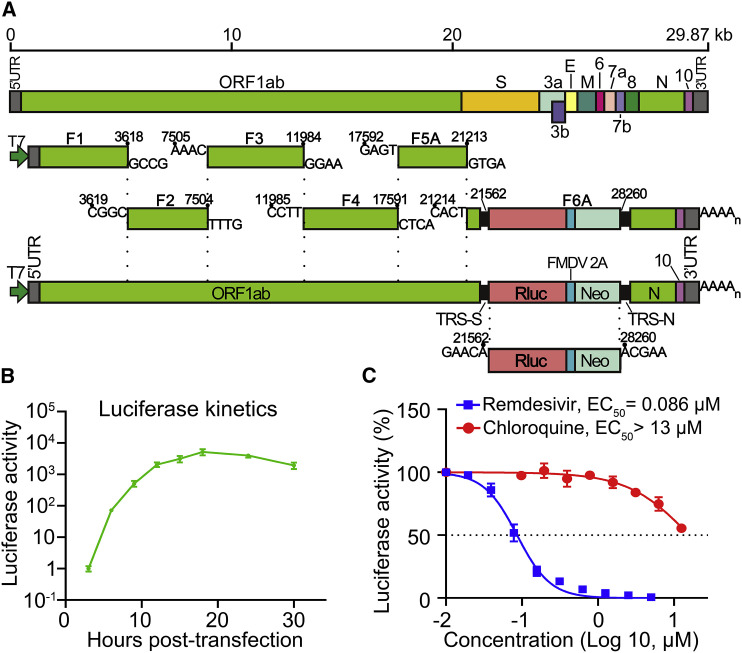

Figure 5.

A SARS-CoV-2 Luciferase Replicon

(A) Construction of SARS-CoV-2 luciferase replicon. The replicon was constructed by deleting nucleotides 21,563–28,259 from the SARS-CoV-2 genome. The deleted viral segment was replaced by a Rluc, a foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A (FMDV 2A), and a neomycin phosphotransferase (Neo). The Rluc/FMDV 2A/Neo reporter is under the control of transcription regulatory sequence (TRS) of the deleted S gene. Replicon cDNA was assembled by six contiguous cDNA fragments through in vitro ligation. Replicon RNA was in vitro transcribed.

(B) Replicon luciferase assay. Huh-7 cells were co-electroporated with replicon RNA and N-encoding mRNA (20 μg), seeded into a 48-well plate, and assayed for Rluc activities at indicated time points.

(C) Antiviral testing of remdesivir and chloroquine. Huh-7 cells, electroporated with replicon RNA from (B), were seeded into a 96-well plate (50 μL per well), treated with compounds (50 μL per well) for 24 h, and quantified for Rluc activities. The DMSO control treatment was set to 100%. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments. EC50 values were calculated by nonlinear regression.

To demonstrate the utility of the replicon, we treated replicon-electroporated Huh-7 cells with remdesivir or chloroquine, two known inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture (Wang et al., 2020). Remdesivir inhibited Rluc activities in a dose-dependent manner, with a 50% effective concentration (EC50) value of 0.086 μM (Figure 5C). This EC50 value is within the range of a previously reported EC50 value of 0.115 μM when testing A549 lung carcinoma cells that express human ACE2 receptor (Xie et al., 2020b) and 0.01 μM when using human airway epithelial culture (Pruijssers et al., 2020). Since the replicon does not contain viral proteins used for entry or assembly, the result confirms that remdesivir inhibits viral RNA synthesis. By contrast, chloroquine exhibited an EC50 > 13 μM in the replicon assay (Figure 5C), which contrasts with the EC50 value of 1.3 μM when tested in a luciferase reporter virus infection assay (Xie et al., 2020b). The results suggest that chloroquine does not exert its antiviral activity through suppression of viral RNA synthesis. Altogether, the data suggest that RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 could be used as a tool to study viral replication and drug discovery at a BSL-2 facility.

Inhibition of IFN-I Signaling Affects Coronavirus Replication

To examine the biological relevance of the differences of nsp1 and nsp6 in inhibiting IFN-I signaling among three coronaviruses (Figures 4B and 4C), we prepared four chimeric RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 constructs in which either nsp1 or nsp6 was replaced by that of SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV (Figure 6 A). For the chimeric nsp1 replicons, RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-SARS-nsp1 (containing SARS-CoV nsp1) produced a Rluc profile similar to that of RlucRep-SARS-CoV (Figure 6B), indicating that the chimeric replicon is fully replicative. However, only background levels of Rluc were detected from cells electroporated with RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-MERS-nsp1 (containing MERS-CoV nsp1; Figure 6B), indicating that MERS-CoV nsp1 cannot support SARS-CoV-2 replication. This is not surprising because only 26% amino acid homology exits between SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV nsp1 (Figure S4). Next, we examined the effect of chimeric nsp1 on viral replication when treated with IFN-α. After baby hamster kidney strain 21 (BHK-21) cells were electroporated with replicon RNA, cells were immediately treated with IFN-α and assayed for Rluc activity at 24 hpt. RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 produced significantly higher Rluc activity than RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-SARS-nsp1 (Figure 6C), consistent with the finding that the former inhibited IFN-I signaling more efficiently than the latter (Figure 4B).

Figure 6.

Effects of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV nsp1 and nsp6 on SARS-CoV-2 Replication

(A) SARS-CoV-2 replicon (RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2) and chimeric replicons containing SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV nsp1 or nsp6.

(B–E) Transient replicon assay and IFN-α inhibition. BHK-21 cells were co-electroporated with different replicon RNAs and N-encoding mRNA (20 μg), seeded into 48-well plates, and harvested at different time points to indicate viral replication. Data were normalized by luciferase activities at 3 hpt. (B and D) Alternatively, the electroporated cells in the 48-well plates were treated with IFN-α for 24 h and assayed for luciferase activities. The data were normalized by non-treated group. (C and E) Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical values were analyzed by comparing with RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 and two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

For the chimeric nsp6 replicons, RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2, RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-SARS-nsp6, and RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-MERS-nsp6 produced similar Rluc profiles in BHK-21 cells (Figure 6D), indicating that heterologous nsp6 proteins did not affect viral replication. After treating the replicon-electroporated cells with IFN-α, different levels of Rluc activity were observed at 24 hpt, with RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2 having the highest activity, followed by RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-MERS-nsp6 and RlucRep-SARS-CoV-2-SARS-nsp6 (Figure 6E). The Rluc signals are inversely correlated to the relative potency of the nsp6 of each respective virus to inhibit IFN-I signaling (Figure 4B).

Collectively, the results show that nsp1 and nsp6 from three coronaviruses inhibit IFN-I signaling at different efficiency. In SARS-CoV-2, the potent inhibition of IFN-I signaling by nsp1 and nsp6 leads to higher viral replication than for SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV.

Discussion

The goals of this study are (1) to identify SARS-CoV-2 proteins that suppress IFN-I response; (2) to determine at which step inhibition occurs in the IFN-I production and signaling pathways; (3) to compare the inhibitory activity among MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 of IFN-I production and signaling; and (4) to evaluate the biological relevance of these coronavirus differences in the context of SARS-CoV-2 replication. These studies are important because IFN-I is being considered as a COVID-19 treatment (Mantlo et al., 2020; Sallard et al., 2020). Our results indicate that SARS-CoV-2 proteins antagonize distinct steps in IFN-I production and signaling. Figure 2F summarizes the antagonism of IFN-I production: nsp6 and nsp13 binds to TBK1 to suppress IRF3 and TBK1 phosphorylation, respectively; and OFR6 blocks IRF3 nuclear translocation. Figure 3D summarizes the suppression of IFN-I signaling: nsp1, nsp6, nsp13, ORF3a, M, and ORF7b block STAT1 phosphorylation; nsp6, nsp13, ORF7a, and ORF7b suppress STAT2 phosphorylation; and ORF6 inhibits nuclear translocation of STAT1. Consistent with our results, Yuen et al. (2020) recently reported that nsp13 and ORF6 of SARS-CoV-2 antagonize IFN-I response. In addition, they found that nsp14 and nsp15 also suppressed IFN-β production, which was not observed in our study. After submission of our study, Lei et al. (2020) reported SARS-CoV-2 nsp1, nsp3, nsp12, nsp14, ORF3, ORF6, and M protein inhibited >50% IFN-I induction when activated through RIG-I. These discrepancies could be due to different experimental systems. We transfected a low amount of protein expression plasmid (20–80 ng) in our screen assay. In the screen assay, a viral protein is expressed in isolation and its expression level could differ from that in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. It is therefore important to validate the screen findings in the context of viral replication. Future effort could first focus on the common proteins (e.g., ORF6) that have been consistently identified from different studies.

Several SARS-CoV-2 proteins antagonize multiple steps in the IFN-I production/signaling pathways, including nsp6, nsp13, and ORF6. Further studies are needed to define the regions of each protein that are responsible for distinct functions of IFN-I production and/or signaling. SARS-CoV nsp6 is a transmembrane protein that rearranges the cellular membrane to form double-membrane vesicles for viral replication (Angelini et al., 2013). Nsp13 is an RNA helicase that is conserved among coronaviruses. Similarly, hepatitis C virus (HCV) helicase was also shown to bind TBK1 and block TBK1/IRF3 interaction (Otsuka et al., 2005). Experiments are underway to examine whether the helicase activity of SARS-CoV-2 nsp13 is required for IFN-I antagonism. For nsp6 and nsp13, the molecular mechanisms of their dual activities to bind TBK1 and to suppress STAT1/STAT2 phosphorylation remain to be determined. Our results, together with a recent study (Cai et al., 2020), indicate that ORF6 binds to importin KPNA2 to block nuclear translocation of IRF3 and ISGF3, leading to suppression of both IFN-I production and signaling, respectively. Our SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 results are consistent with those of previous studies showing that SARS-CoV ORF6 inhibits both IFN production and STAT1 signaling by interacting with KPNA2 and altering nuclear import (Frieman et al., 2007; Kopecky-Bromberg et al., 2007).

Nsp1 and nsp6 of SARS-CoV-2 suppress IFN-I signaling more efficiently than those of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. The biological relevance of this finding was evaluated through a reporter replicon of SARS-CoV-2. Consistent with the greater inhibition of IFN-I signaling by SARS-CoV-2 nsp1 and nsp6, chimeric replicons containing SARS-CoV nsp1 or nsp6 or MERS-CoV nsp6 were more sensitive to IFN-α inhibition. Without IFN-α treatment, the chimeric replicons replicated to the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 replicon level; however, chimeric replicon containing MERS-CoV nsp1 was lethal (Figures 6B and 6C). The replication capability of chimeric replicons correlated with the relative degree of protein sequence homology of nsp1 or nsp6 among the three viruses (Figure S4).

In contrast to our results, Lokugamage et al. (2020) found that complete SARS-CoV-2 was more sensitive to IFN-I inhibition than SARS-CoV. This discrepancy may result from two sources: (1) differences in IFN-I antagonism from other viral proteins among different coronaviruses (which remain to be determined) and (2) lack of viral structural and accessory proteins in the replicon system. Regarding the latter source, ORF7a and ORF7b, located at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi intermediate compartment, are assembled into SARS-CoV virions (Dedeurwaerder et al., 2014); the antagonistic activities of those accessory proteins may facilitate viral replication at the early stage of viral infection. The collective effect from all modulating proteins determines the final antagonism for each virus (Totura and Baric, 2012). Different levels of viral replication and immune antagonism could dictate viral transmission and disease development. In support of this notion, when infecting human lung tissues, SARS-CoV-2 produced significantly more virus but less IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines than SARS-CoV, providing an explanation for asymptomatic transmission and delayed disease onset of COVID-19 (Chu et al., 2020). Besides innate immunity, pre-existing cross-protective T cell immunity (derived from previous exposures with closely related β-coronaviruses) may also protect disease development (Le Bert et al., 2020).

We have developed a reporter replicon of SARS-CoV-2 suitable for studying viral replication at BSL-2 laboratories. The replicon system is particularly useful when studying factors that could lead to gain of function in the complete virus. We demonstrated the utility of replicon for drug discovery by testing two known SARS-COV-2 inhibitors, remdesivir and chloroquine (Wang et al., 2020). Only remdesivir, not chloroquine, inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replicon replication. This result supports distinct antiviral mechanisms of the two inhibitors: remdesivir inhibits viral replication through RNA chain termination (Pruijssers et al., 2020), whereas chloroquine blocks virus entry/fusion through increasing endosomal pH (Vincent et al., 2005).

In summary, we have identified SARS-CoV-2 proteins that antagonize IFN-I production and signaling. The antagonizing steps for each identified protein have been mapped to distinct components in the IFN-I production/signaling pathways. The collective activity from these proteins determines the overall antagonism against IFN-I restriction in infected hosts. The inhibitory potencies of the antagonizing proteins may differ among different coronaviruses, which could account for the outcome of viral replication, transmission, and pathogenesis. Additionally, we have developed a reporter replicon for studying SARS-CoV-2 replication and antiviral discovery.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit IgG anti-HA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#H6908; RRID: AB_260070 |

| Rabbit IgG anti-Flag | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F7425; RRID: AB_439687 |

| Rabbit IgG anti-GAPDH | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G9545; RRID: AB_796208 |

| Mouse IgG anti-HA | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2367S; RRID: AB_10691311 |

| Mouse IgG anti-Flag | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#8146S; RRID: AB_10950495 |

| Mouse IgG anti-IRF3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#10949; RRID: AB_2797733 |

| Rabbit IgG anti-pIRF3 (S396) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#29047; RRID: AB_2773013 |

| anti-pTBK1 (S172) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5483; RRID: AB_10693472 |

| Rabbit IgG anti-TBK1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3504; RRID: AB_2255663 |

| anti-STAT1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#14994S; RRID: AB_2737027 |

| pSTAT1 (Y701) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7649S; RRID: AB_10950970 |

| anti-STAT2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#72604S; RRID: AB_2799824 |

| anti-pSTAT2 (Y690) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#88410S; RRID: AB_2800123 |

| Mouse IgG anti-GFP | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2955; RRID: AB_1196614 |

| Mouse IgG1 anti- SARS-CoV-2 spike | GeneTex | Cat#GTX632604; RRID: AB_2864418 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with HRP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A5278; RRID: AB_258232 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with HRP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#AP307P; RRID: AB_11212848 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgGs conjugated with Alexa 488 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#A-11001; RRID: AB_2534069 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgGs conjugated with Alexa 568 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#A-11004; RRID: AB_2534072 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgGs conjugated with Alexa 488 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#A-11008; RRID: AB_143165 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgGs conjugated with Alexa 568 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#A-11011; RRID: AB_143157 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli strain Top10 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C404006 |

| SARS-CoV strain 2019-nCoV/USA_WA1/2020 (WA1) | Xie et al., 2020a | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Recombinant human α-interferon | Millipore | Cat#IF007 |

| Interferon-αA/D human | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#I4401 |

| poly (I:C) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P9582 |

| Pierce Anti-HA Magnetic Beads | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#88837; RRID: AB_2861399 |

| Renilla Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat#E2810 |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System | Promega | Cat#E1980 |

| T7 mMessage mMachine kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#AM1344 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Unprocessed western blot and original IFA images | Mendeley Data | https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/324cs9ymc2/draft?a=5ce749f3-2e33-4a3b-892f-2f9eb2dc60de |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK293T cell | ATCC | Cat#CRL-3216; RRID: CVCL_0063 |

| Vero cell | ATCC | Cat#CCL-81; RRID: CVCL_0059 |

| BHK-21 cell | ATCC | Cat#CCL-10; RRID: CVCL_1915 |

| Huh-7 cell | Giraldo et al., 2020 | RRID: CVCL_0336 |

| A549 cell | Giraldo et al., 2020 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for plasmid construction | This paper | Table S1 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp1 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp2 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp3 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp4 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp5 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp6 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp7 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp8 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp9 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp10 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp11-EGFP | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp12 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp13 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp14 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp15 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-nsp16 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-E | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-M | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-N | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF3a | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF3b | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF6 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF7a | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF7b | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF8 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-2-ORF10 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-nsp1 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-MERS-CoV-nsp1 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-nsp6 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-MERS-CoV-nsp6 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-nsp13 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-MERSS-CoV-nsp13 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-ORF6 | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-ORF7a | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-SARS-CoV-ORF7b | This paper | N/A |

| pUC57-CoV2-F1 | Xie et al., 2020a | N/A |

| pUC57-CoV2-F2 | Xie et al., 2020a | N/A |

| pUC57-CoV2-F3 | Xie et al., 2020a | N/A |

| pUC57-CoV2-F4 | Xie et al., 2020a | N/A |

| pUC57-CoV2-F5A | This paper | N/A |

| pUC57-CoV2-F6A | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-empty-vector | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| pXJ-EGFP | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| pIFN-β-luc | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| phRluc-TK | Promega | Cat#E6921 |

| pISRE-luc | Agilent Technologies | Cat#219089-51 |

| RIG-I (2CARD) | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| MAVS | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| TBK1 | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| IRF3/5D | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| IRF3 | Xia et al., 2018 | N/A |

| pXJ-KPNA1-HA | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-KPNA2-HA | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-KPNA3-HA | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-KPNA4-HA | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-KPNA5-HA | This paper | N/A |

| pXJ-KPNA6-HA | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Prism 8.0 software | GraphPad | N/A |

| ImageJ | NIH | N/A |

| Photoshop | Adobe | N/A |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Pei-Yong Shi (peshi@UTMB.edu).

Materials Availability

The cDNA plasmids for making the SARS-CoV-2 reporter replicon have been deposited to the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (https://www.utmb.edu/wrceva) at UTMB for distribution. Plasmids generated in this study are available upon request from the Lead Contact.

Data and Code Availability

The results presented in the study are available upon request from the corresponding authors. Original data have been deposited to Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/324cs9ymc2.1

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Cell lines

HEK293T, Vero, BHK-21 and Huh-7 cells were purchased from the America Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Bethesda, MD), and maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C with 5% CO2. A549 cells were grown in minimum essential medium, supplemented with 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. All culture medium and antibiotics were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). All cell lines were tested negative for mycoplasma.

Plasmids and Reagents

CMV promoter-driven expression vector, pXJ, was used to express individual viral proteins by cloning corresponding SARS-CoV-2 genes (Xia et al., 2018). Each gene was derived from PCR using infectious cDNA clone plasmids (Xie et al., 2020a), and fused with a Flag-tag at C-terminal. The reporter plasmid pIFN-β-luc and expression plasmids for RIG-I (2CARD), MAVS, TBK1, IKKε, and IRF3 were reported previously (Bharaj et al., 2016; Xia et al., 2018). The reporter plasmid pISRE-luc was purchased from Agilent Technologies (Cat: 219089-51, Santa Clara, CA) and pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] (phRluc-TK) was purchased from Promega (Cat: E6921, Madison, WI). KPNA1-6 genes were amplified from mRNA of HEK293T cells, and fragments were constructed to pXJ vector with an HA-tag at C-terminal. All primers used for plasmid construction are listed in Table S1.

Recombinant human α-interferon (Cat: IF007) was purchased from Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). Interferon-αA/D human (Cat: I4401), and poly (I:C) (Cat: P9582) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The following antibodies were used in this study: rabbit anti-HA (Cat: H6908, 1:1000), rabbit anti-Flag (Cat: F7425, 1:1000),and anti-GAPDH (Cat: G9545, 1:1000) antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich; mouse anti-HA (Cat: 2367S, 1:1000), mouse anti-Flag (Cat: 8146S, 1:1000), anti-IRF3 (Cat: 10949, 1:1000), anti-pIRF3 at Ser-396 (Cat: 29047, 1:1000), anti-TBK1 (Cat: 3504, 1:1000), anti-pTBK1 (S172) (Cat: 5483, 1:1000), anti-STAT1 (Cat: 14994S, 1:1000), anti-pSTAT1 (Y701) (Cat: 7649S, 1:1000), anti-STAT2 (Cat: 72604S, 1:1000), anti-pSTAT2 (Y690) (Cat: 88410S, 1:1000) and anti-GFP (CST: 2955, 1:1000) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody (Cat: GTX632604, 1:1000) was from GeneTex (Irvine, CA); anti-mouse IgG conjugated Alexa 488, anti-mouse IgG conjugated Alexa 568, anti-rabbit IgG conjugated Alexa 488, and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated Alexa 568 antibodies in goat were from ThermoFisher Scientific.

Method Details

Expression of individual SARS-CoV-2 proteins

HEK293T cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates for overnight incubation. Cells were transfected with 0.5-2 μg of viral protein expression plasmid using X-treme-GENE™ 9 transfection reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 36 hpt, the cells were harvested and lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.05% n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (Anatrace, Maumee, OH), and EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] with rotation at 4°C for 1 h. After clarification, samples were analyzed by western blot.

IFN-I production and signaling luciferase reporter assays

The IFN-I production assay was performed as described previously (Xia et al., 2018). Briefly, HEK293T cells (1 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well plate) were co-transfected with 10 ng of IFN-β promoter reporter plasmid, 4 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmid, 20-80 ng of viral protein expression plasmid using X-treme-GENE™ 9 transfection reagent with a ratio 1:2. Empty pXJ vector was used to ensure the same total amount (100 ng) of plasmids in each well. Cells were induced by co-transfection with 4 ng/well of stimulator expressing plasmids [(RIG-I (2CARD), MAVS, TBK1, IKKε, or IRF3)], same amount of empty pXJ vector was used as non-stimulated control. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were assayed for dual-luciferase activities according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). For the IFN-I signaling, HEK293T cells (1 × 105 cells/well, 24-well plate) were co-transfected with 250 ng of ISRE promoter reporter plasmid, 20 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmid, and 230 ng of viral protein expression plasmid. At 16 h post-transfection, the transfected cells were treated with 1,000 units/ml of human IFN-α (Millipore). After another 8 h incubation, the cells were lysed and performed dual-luciferase reporter assays according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Luciferase signals were read by Cytation 5 (Bio Tek, Winooski, VT).

Co-immunoprecipitation and western blot

Transfected HEK293T cells were harvested and lysed in IP lysis buffer (250 μl) with rotation at 4°C for 1 h and the lysates were clarified by centrifugation (20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C). Clarified lysates (25 μl) was mixed with 4 × lithium dodecyl sulfate buffer (LDS, ThermoFisher Scientific) containing 100 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol, samples were heated at 70°C for 10 min, and stored at −20°C or analyzed by western blot as input whole cell lysis (WCL). For the rests of the lysates, immunoprecipitation was performed by using specific antibodies, extra NaCl was added to a final concentration of 300 mM. Subsequently, the immune complexes were captured by protein G-conjugated magnetic beads (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After extensively washing, beads were eluted by denaturation in 2 × LDS buffer at 70°C for 10 min.

Protein samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), followed by blocking for 1 h and probing with an indicated primary antibody and an anti-Rabbit/Mouse IgG-Peroxidase antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:20,000). The proteins were visualized using SuperSignal Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) and ChemiDoc Imaging Systems (Bio-Rad).

Indirect immunofluorescence assays

Cells were seeded in a 4-well Lab-Tek Chamber slide (ThermoFisher Scientific). At given time points, transfected cells (with or without treatment) were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 20 min, and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. After three washes, cells were treated with PBS containing 2% FBS for blocking at room temperature for 1 h, followed by 1 h incubation with primary antibody and secondary antibody (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 568). Cells were washed for three times, and counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were obtained by using Eclipse Ti2 inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

DNA assembly and RNA transcription of a luciferase replicon for SARS-CoV-2

A full-length SARS-CoV-2 cDNA infectious clone has been engineered by our lab recently (Xie et al., 2020a). The transient luciferase replicon for SARS-CoV-2 was designed through replacing the nucleotides 21,563 to 28,259 from the viral genome, including S, E, M, and accessory genes (ORF3a, 3b, 6, 7a, 7b and 8), with a gene cassette encoding the Renilla luciferase, an FMDV 2A and a neomycin phosphotransferase (Neo). The engineered Rluc/FMDV-2A/Neo reporter was under the control of transcription regulatory sequence (TRS) of the S gene, and genes N were driven by the TRS-N. The SARS-CoV-2 transient luciferase replicon was assembled through in vitro ligation of six contiguous fragments (F1, F2, F3, F4, F5A and F6A; Figure 5A). F1-4 were obtained by digesting the corresponding plasmids with enzyme BsaI as previously described (Xie et al., 2020a). An Esp3I restriction cleavage site was engineered at nucleotide 21,213 in F5A and F6A was constructed by overlap PCR. Therefore, both of F5A and F6A could be obtained by Esp3I digestion. To assemble the SARS-CoV-2 transient luciferase replicon DNA, equimolar amounts of six contiguous cDNA fragments (totally 5 μg) were in vitro ligated in a 100-μl reaction with T4 ligase (NEB, Ipswich, MA). The ligated production was identified by agarose gel, followed by purification using phenol/chloroform, isopropanol precipitation, and resuspended in nuclease-free water.

SARS-CoV-2 luciferase replicon RNA was in vitro synthesized using mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After incubation 6 h at 37°C, DNA template (2 μg) was removed by DNase, the RNA was purified through phenol/chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. The N gene mRNA was obtained through T7 RNA in vitro transcription as previously described (Xie et al., 2020a).

Replicon RNA electroporation and luciferase reporter assay

SARS-CoV-2 luciferase replicon antiviral compound test was performed in Huh-7 cells, and replicon IFN-α inhibition assay was performed in BHK-21 cells. RNA transcripts were electroporated into Huh-7 cells or BHK-21 cells using protocols previously reported (Xie et al., 2020a). Briefly, 20 μg of SARS-CoV-2 luciferase replicon RNA and 20 μg of N gene transcripts were mixed in to a 4-mm corvette containing 0.8 mL cells (1 × 107 cells/ml) in Ingenio Electroporation Solution (Mirus, Madison, WI). For antiviral drug test, replicon RNA and N mRNA were co-electroporated into Huh-7 cells, single electrical pulse was given with GenePulser apparatus (Bio-Rad) at setting of 270 V at 950 μF. After 10 min recovery at room temperature, electroporated cells were resuspended in DMEM without phenol red. Fifty microliters of cell suspension seeded into each well of a white opaque 96-well plate (Corning, Corning, NY). Antiviral drugs were two-fold diluted from 2 mM in DMSO, and the same amount of compound dilutions (50 μl) were mixed with electroporated cells aliquots. At 24 hpt, luciferase activity was quantified using ViviRen Live Cell Substrate (Promega). For interferon inhibition test, the replicon RNA and N mRNA were co-electroporated into BHK-21 cells, GenePulser apparatus (Bio-Rad) was used with setting at 850 V at 25 μF and pulsing three times, with 3 s intervals. After 10 min recovery, electroporated cells were resuspended in DMEM and seeded in to 48-well plate. Cells were immediately treated with serial dilutions of antiviral compounds or IFN-α. Cells were harvested at various time points or at 24 h post treatment for measuring luciferase signals using Renilla luciferase assay system (Promega). The luciferase signal was read by Cytation 5 (Bio Tek) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 software. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of groups were performed using one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) was determined by nonlinear regression curve using GraphPad Prism 8 software, the bottom and top were constrained to 0% and 100%, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank lab members and UTMB colleagues for helpful discussions during the course of this project. P.-Y.S. was supported by NIH grants AI142759, AI134907, AI145617, and UL1TR001439 and awards from the Sealy & Smith Foundation, Kleberg Foundation, John S. Dunn Foundation, Amon G. Carter Foundation, Gillson Longenbaugh Foundation, and Summerfield Robert Foundation. R.R. was supported by NIH grants R01AI134907, R21AI132479-01, and R21AI126012-01A1. V.D.M. was supported by NIH grants U19AI100625, R00AG049092, R24AI120942, and STARs Award from the University of Texas System.

Author Contributions

H.X., Z.C., X.X., X.Z., H.W., and P.-Y.S. designed experiments, analyzed data, and interpreted results. H.X., Z.C., X.X., X.Z., and J.Y.-C.C. performed experiments. V.D.M. and R.R. provided critical reagents and advice on experimental approaches. H.X., Z.C., and P.-Y.S. wrote the paper. All authors read and edited the paper.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: September 19, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108234.

Supplemental Information

References

- Acharya D., Liu G., Gack M.U. Dysregulation of type I interferon responses in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:397–398. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0346-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelini M.M., Akhlaghpour M., Neuman B.W., Buchmeier M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural proteins 3, 4, and 6 induce double-membrane vesicles. MBio. 2013;4:e00524-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00524-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., Flemban H., Al-Nassir W.N., Balkhy H.H., Al-Hakeem R.F., et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au-Yeung N., Mandhana R., Horvath C.M. Transcriptional regulation by STAT1 and STAT2 in the interferon JAK-STAT pathway. JAK-STAT. 2013;2:e23931. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran S., Roberts P.C., Brown L.E., Truong H., Pattnaik A.K., Archer D.R., Barber G.N. Essential role for the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase PKR in innate immunity to viral infection. Immunity. 2000;13:129–141. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharaj P., Wang Y.E., Dawes B.E., Yun T.E., Park A., Yen B., Basler C.F., Freiberg A.N., Lee B., Rajsbaum R. The Matrix Protein of Nipah Virus Targets the E3-Ubiquitin Ligase TRIM6 to Inhibit the IKKε Kinase-Mediated Type-I IFN Antiviral Response. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005880. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Zhang M.X., Tang Z., Zhang Q., Ye J., Xiong T.C., Zhang Z.D., Zhong B. USP22 promotes IRF3 nuclear translocation and antiviral responses by deubiquitinating the importin protein KPNA2. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217:e20191174. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chook Y.M., Blobel G. Karyopherins and nuclear import. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:703–715. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Chan J.F., Wang Y., Yuen T.T., Chai Y., Hou Y., Shuai H., Yang D., Hu B., Huang X., et al. Comparative replication and immune activation profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in human lungs: an ex vivo study with implications for the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:1400–1409. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedeurwaerder A., Olyslaegers D.A.J., Desmarets L.M.B., Roukaerts I.D.M., Theuns S., Nauwynck H.J. ORF7-encoded accessory protein 7a of feline infectious peritonitis virus as a counteragent against IFN-α-induced antiviral response. J. Gen. Virol. 2014;95:393–402. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.058743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald K.A., McWhirter S.M., Faia K.L., Rowe D.C., Latz E., Golenbock D.T., Coyle A.J., Liao S.M., Maniatis T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieman M., Yount B., Heise M., Kopecky-Bromberg S.A., Palese P., Baric R.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF6 antagonizes STAT1 function by sequestering nuclear import factors on the rough endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi membrane. J. Virol. 2007;81:9812–9824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieman M., Ratia K., Johnston R.E., Mesecar A.D., Baric R.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease ubiquitin-like domain and catalytic domain regulate antagonism of IRF3 and NF-kappaB signaling. J. Virol. 2009;83:6689–6705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02220-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo M.I., Xia H., Aguilera-Aguirre L., Hage A., van Tol S., Shan C., Xie X., Sturdevant G.L., Robertson S.J., McNally K.L., et al. Envelope protein ubiquitination drives entry and pathogenesis of Zika virus. Nature. 2020;585:414–419. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2457-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Li W., Gao T., Cui Y., Jin Y., Li P., Ma Q., Liu X., Cao C. The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Nucleocapsid Inhibits Type I Interferon Production by Interfering with TRIM25-Mediated RIG-I Ubiquitination. J. Virol. 2017;91:e02143-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02143-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Lokugamage K.G., Rozovics J.M., Narayanan K., Semler B.L., Makino S. SARS coronavirus nsp1 protein induces template-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNAs: viral mRNAs are resistant to nsp1-induced RNA cleavage. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002433. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani W., Narayanan K., Huang C., Lokugamage K., Ikegami T., Ito N., Kubo H., Makino S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 protein suppresses host gene expression by promoting host mRNA degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12885–12890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603144103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani W., Huang C., Narayanan K., Lokugamage K.G., Makino S. A two-pronged strategy to suppress host protein synthesis by SARS coronavirus Nsp1 protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H., Takeuchi O., Sato S., Yoneyama M., Yamamoto M., Matsui K., Uematsu S., Jung A., Kawai T., Ishii K.J., et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler E., Thiel V., Weber F. Interaction of SARS and MERS Coronaviruses with the Antiviral Interferon Response. Adv. Virus Res. 2016;96:219–243. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky-Bromberg S.A., Martínez-Sobrido L., Frieman M., Baric R.A., Palese P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and nucleocapsid proteins function as interferon antagonists. J. Virol. 2007;81:548–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bert N., Tan A.T., Kunasegaran K., Tham C.Y.L., Hafezi M., Chia A., Chng M.H.Y., Lin M., Tan N., Linster M., et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020;584:457–462. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei X., Dong X., Ma R., Wang W., Xiao X., Tian Z., Wang C., Wang Y., Li L., Ren L., et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3810. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17665-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D.E., Darnell J.E., Jr. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Fan Y., Lai Y., Han T., Li Z., Zhou P., Pan P., Wang W., Hu D., Liu X., et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:424–432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Cai X., Wu J., Cong Q., Chen X., Li T., Du F., Ren J., Wu Y.T., Grishin N.V., Chen Z.J. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science. 2015;347:aaa2630. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokugamage K.G., Hage A., Schindewolf C., Rajsbaum R., Menachery V.D. SARS-CoV-2 is sensitive to type I interferon pretreatment. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.07.982264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malathi K., Dong B., Gale M., Jr., Silverman R.H. Small self-RNA generated by RNase L amplifies antiviral innate immunity. Nature. 2007;448:816–819. doi: 10.1038/nature06042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantlo E., Bukreyeva N., Maruyama J., Paessler S., Huang C. Antiviral activities of type I interferons to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antiviral Res. 2020;179:104811. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E., Tschopp J., Karin M. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature. 2006;442:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K., Huang C., Lokugamage K., Kamitani W., Ikegami T., Tseng C.T., Makino S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 suppresses host gene expression, including that of type I interferon, in infected cells. J. Virol. 2008;82:4471–4479. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02472-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer D., Mösbauer K., Klein E.M., Sieberg A., Mettelman R.C., Mielech A.M., Dijkman R., Baker S.C., Drosten C., Müller M.A. The papain-like protease determines a virulence trait that varies among members of the SARS-coronavirus species. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007296. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka M., Kato N., Moriyama M., Taniguchi H., Wang Y., Dharel N., Kawabe T., Omata M. Interaction between the HCV NS3 protein and the host TBK1 protein leads to inhibition of cellular antiviral responses. Hepatology. 2005;41:1004–1012. doi: 10.1002/hep.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A., Iwasaki A. Type I and Type III Interferons - Induction, Signaling, Evasion, and Application to Combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruijssers A.J., George A.S., Schafer A., Leist S.R., Gralinksi L.E., Dinnon K.H., Yount B.L., Agostini M.L., Stevens L.J., Chappell J.D., et al. Remdesivir potently inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in human lung cells and chimeric SARS-CoV expressing the SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase in mice. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.27.064279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallard E., Lescure F.X., Yazdanpanah Y., Mentre F., Peiffer-Smadja N. Type 1 interferons as a potential treatment against COVID-19. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104791. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel C.E. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W.M., Chevillotte M.D., Rice C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014;32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoggins J.W., Wilson S.J., Panis M., Murphy M.Y., Jones C.T., Bieniasz P., Rice C.M. Corrigendum: A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2015;525:144. doi: 10.1038/nature14554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu K.L., Kok K.H., Ng M.H., Poon V.K., Yuen K.Y., Zheng B.J., Jin D.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus M protein inhibits type I interferon production by impeding the formation of TRAF3.TANK.TBK1/IKKepsilon complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:16202–16209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totura A.L., Baric R.S. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent M.J., Bergeron E., Benjannet S., Erickson B.R., Rollin P.E., Ksiazek T.G., Seidah N.G., Nichol S.T. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol. J. 2005;2:69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H., Luo H., Shan C., Muruato A.E., Nunes B.T.D., Medeiros D.B.A., Zou J., Xie X., Giraldo M.I., Vasconcelos P.F.C., et al. An evolutionary NS1 mutation enhances Zika virus evasion of host interferon induction. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:414. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02816-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Muruato A., Lokugamage K.G., Narayanan K., Zhang X., Zou J., Liu J., Schindewolf C., Bopp N.E., Aguilar P.V., et al. An Infectious cDNA Clone of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:841–848. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Muruato A.E., Zhang X., Lokugamage K.G., Fontes-Garfias C.R., Zou J., Liu J., Ren P., Balakrishnan M., Cihlar T., et al. A nanoluciferase SARS-CoV-2 for rapid neutralization testing and screening of anti-infective drugs for COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.22.165712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen C.K., Lam J.Y., Wong W.M., Mak L.F., Wang X., Chu H., Cai J.P., Jin D.Y., To K.K., Chan J.F., et al. SARS-CoV-2 nsp13, nsp14, nsp15 and orf6 function as potent interferon antagonists. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1418–1428. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1780953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The results presented in the study are available upon request from the corresponding authors. Original data have been deposited to Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/324cs9ymc2.1