Abstract

Potentially toxic metals (PTEs) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) present in bio-wastes were the major environmental and health risks for soil use. If pyrolyzing bio-wastes into biochar could minimize such risks had not been elucidated. This study evaluated PTE pools, microbial and ARGs abundances of wheat straw (WS), swine manure (SM) and sewage sludge (SS) before and after pyrolysis, which were again tested for soil amendment at a 2% dosage in a pot experiment with a vegetable crop of pak choi (Brassica campestris L.). Pyrolysis led to PTEs concentration in biochars but reduced greatly their mobility, availability and migration potential, as revealed respectively by leaching, CaCl2 extraction and risk assessment coding. In SM and SS after pyrolysis, gene abundance was removed by 4–5 orders for bacterial, by 2–3 orders for fungi and by 3–5 orders for total ARGs. With these material amended, PTEs available pool decreased by 25%–85% while all ARGs eliminated to background in the pot soil. Unlike a >50% yield decrease and a >30% quality decline with unpyrolyzed SM and SS, their biochars significantly increased biomass production and overall quality of pak choi grown in the amended soil. Comparatively, amendment of the biochars decreased plant PTEs content by 23–57% and greatly reduced health risk of pak choi, with total target hazard quotient values well below the guideline limit for subsistence diet by adult. Furthermore, biochar soil amendment enabled a synergic improvement on soil fertility, product quality, and biomass production as well as metal stabilization in the soil-plant system. Thus, biowastes pyrolysis and reuse in vegetable production could help build up a closed loop of production-waste-biochar-production, addressing not only circular economy but healthy food and climate nexus also and contributing to achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals.

Keywords: Bio-waste, Biochar, Potentially toxic metals, Antibiotic resistant genes, Vegetable production, Soil amendment, Clean production

Graphical abstract

Nomenclature and abbreviation

Parameter and variables

- ARG

Antibiotic resistance gene

- PTE

Potential toxic element

- Plant availability

Portion of CaCl2 extractable pool to the total

- Chemical mobility

Portion of soluble and exchangeable pools to the total

- Environment migration risk

Overall migration potential of based on TCLP pools

- Soil fertility

Overall quality with nutrients and metal availability of soil

- Plant quality

Overall quality with nutrition value and metal concentration

- Plant yield

Plant biomass of edible parts

- BCF

Bio-concentration factor

- THQ

Target hazard quotient

Material/protocol

- WS

Wheat crop residue

- SM

Swine manure

- MSS

Municipal sewage sludge

- UWS

Wheat residue before pyrolysis

- USM

Swine manure before pyrolysis

- USS

Sewage sludge before pyrolysis

- WSB

Wheat residue after pyrolysis

- SMB

Swine manure after pyrolysis

- SSB

Sewage sludge after pyrolysis

- RAC

Metal risk assessment coding

- TCLP

Toxicity characteristic leaching protocol

1. Introduction

Managing solid municipal wastes had been a cross-cutting issue for human well-being, directly linked to 12 out of 17 United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs), including SGD 3 on good health and well-being, SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation, SDG7 on affordable and clean energy, SDG 11 on sustainable cities, SDG 12 on responsible consumption and production and SGD 13 on life on land as well as SGD 8 on decent work and economic growth (Rodit and Wilson, 2017). Biowastes, the solid wastes generated with the supply chain and crop production, meat consumption and municipal sewage treatment, consisted of the primary crop residue from croplands, secondary manure from livestock consuming crop food and tertiary (processed) biosolids from municipal waste treatment (Pan et al., 2017). With the rapid agricultural intensification of crop and poultry production, and fast urbanization, the increasingly enormous amount of these biowastes had extensively posed environmental risks, seriously challenging the sustainability of global society and thus demanding a shifting paradigm of circular economy or bioeconomy (Cherubin et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2017). Global crop residues amounted to 4 billion tons (Lal, 2005), of which hundreds million tons wasted (Kim and Dale, 2004). Global municipal solid waste, with sewage sludge biosolids as a major component, was 1.5 billion tons in 2015, of which 85% unrecycled (Zaman, 2015). Meanwhile, global total livestock manure production, mostly applied to soil, reached over 55 billion tons per annum including 1.5 billion tons from pig production (Girotto and Cossu, 2017). In China particularly, solid waste production of crop residue, livestock manure and municipal sewage sludge were generated respectively by 900, 3000 and 600 million metric tons per annum by 2013 (NDRC, 2012, 2013a; CUWA, 2013). Therefore, clean and safe treatment before recycling of these biowastes had been urged with green supply chain management of global economy for human well-being (de Oliveira et al., 2018).

The strategy of Green Supply Chain Management, with its ‘environmental’ core, required minimizing wastes and thus pollutants release with the production and consumption (de Oliveira et al., 2018). The significant presence of hazardous materials such as potentially toxic heavy metals (PTEs), pathogens, antibiotic residues, and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), particularly in livestock manure and sewage sludge (Bloem et al., 2017), could restrict their recycled use concerned with potentially serious environment and health risks with soil application. In a recent FAO report (Rodríguez-Eugenio et al., 2018), livestock and municipal solid waste were identified as the key sources of soil contamination of PTEs and antibiotics found in a wide range of agricultural soils. Among the conventional practices, direct combustion of crop residue and livestock manure as well as incineration of sewage sludge could kill pathogens (Bloem et al., 2017), but led to emissions of potentially toxic gases and particulate pollutants (PM2.5 and PM10) into the atmosphere (Andreae and Merlet, 2001). Direct land disposal or incorporation into soil of bio-wastes, on the other hand, could cause soil contamination of pathogens, crop pests and diseases, PTEs, pesticides and antibiotics, as well as ARGs (Zhu et al., 2013; Bloem et al., 2017; Cherubin et al., 2018). Yet, direct land disposal or field burning of biowastes had been strictly banned in China (NDRC, 2013) and other countries (Lohri et al., 2017). Composting, as a routine approach for recycling bio-wastes, could help to reduce bioavailability of PTEs (Fischer and Glaser, 2012) and abundance levels of antibiotics and ARGs (Zhu et al., 2013). This technology had been constrained with land occupation and time-consuming, and with significant presence of obnoxious odors and of hazardous residues post treatment (Sweeten and Auvermann, 2008). Further, significant increases in PTEs mobility (Bloem et al., 2017) and in ARGs abundance both in soil and water (Gaze et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013) were often observed following biowaste compost application. Significant concentrations of ARGs were detected even in the root tissue and rhizosphere soil of vegetable crops (Rahube et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019) following their application. Anaerobic digestion used to be a rational treatment of organic wastes for biogas production (Koten et al., 2014; Koten, 2017) though often constrained with high cost for maintenance and the need for processing the solid residues (Pham et al., 2006). As such, major environmental concerns raised in recent years in managing the disposal of the wastes and the processed materials in a safe way (Paes et al., 2019).

Soil health had been increasingly concerned for human well-being (Lehmann et al., 2015), particularly post-COVID-19 (DGRI-EI, 2020). Increase in soil organic matter, often recognized as soil carbon sequestration practically through recycling of organic wastes (Lal, 2004), had been a focus in improving soil health (Maharjan et al., 2020). Hence, novel cost-effective technologies had been urged to eliminate or stabilize the metal and biological pollutants present in biowastes before they could be recycled as soil input of organic matter and mineral nutrients. The pollutants in biowastes could be taken up by plant and soil food web, and further accumulate through food chain, causing potential health risks for ecosystem and human (Kumar et al., 2005). In particular, ARGs migration through soil-water-food system (Kistemann et al., 2002) had been increasingly concerned as an emerging biological pollutant with serious human health risks, potentially causing 10 million deaths by 2050 (de Kraker et al., 2016). Guidelines or standards with established threshold values had been set up for controlling the presence of the inorganic, biological and microbial pollutants in treated biowaste before application (MOAC, 2012; SAC, 2018). Recently, detection and control of antibiotics and resistant gens had been proposed for manure use in China’s agriculture (SAC, 2017). While traditional primary and secondary treatment processes were considered insufficient to remove the substantial amounts of pollutants and other contaminants causing water/soil-borne diseases, conversion of biowastes into biochar had been recently recommended as a sustainable solution for solid waste (Dahal et al., 2018). Unfortunately, this was often considered with energy recovery (Dahal et al., 2018; Lam and Chase, 2015) but few with co-stabilization of potential toxic metals and anti-microbial genes before safe application to soil.

Pyrolysis, the thermal conversion of biomass into biochar, had been increasingly advocated as a multiple-win strategy to safely recycle biowastes (Kwapinski et al., 2010; Navia and Crowley, 2010; Frišták et al., 2018). Following pyrolysis, mineral nutrients such as P and K were largely retained, heavy metals stabilized, organic pollutants and biological residues degraded as well as mass volume largely reduced in the solid biochar over the feedstock (Lehmann and Joseph, 2015; Pan et al., 2017). In agriculture, multiple benefits provided with biochars on carbon emission abatement, metal stabilization, soil nutrient availability, and microbial growth and activity, depletion of soil-borne plant pathogens, and crop productivity had been widely reported (Gul et al., 2015; Qambrani et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2020). Particularly, such biochar had been found a great potential for use in waste water treatment (Mohan et al., 2014). In agriculture, whereas, livestock manure and municipal sewage sludge had been treated with pyrolysis into biochar and tested for plant growth (Khan et al., 2017; Shao et al., 2019), waste composting (Chowdhury et al., 2014) and environmental sorbents (Ahmad et al., 2014). While information on the removal of ARGs in biowastes by pyrolysis were very limited (Cui et al., 2017), it could be a critical issue if pyrolysis could concurrently stabilize PTEs and ARGs in biowaste and thus ensure safe application for plant growth (Chen et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2019). Yet, changes in environmental and health risks following application of such biochars to vegetable production had been poorly addressed (Zhang et al., 2017; Dahal et al., 2018). Thus, the changes before and after pyrolysis in presence and mobility of PTEs and ARGs, and their potential environmental and health risks as well as crop production effects should be evaluated.

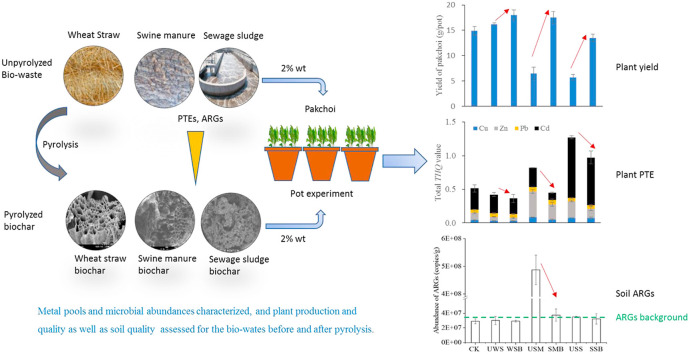

In this study, it is hypothesized that conversion via pyrolysis could greatly stabilize heavy metals and eliminate ARGs of biomass wastes generated in crop production, animal breeding and municipal waste water treatment, thus largely minimizing the potential environmental and health risks. We further hypothesize that soil health and safe production of vegetable crop for diet consumption could be ensured through improving soil fertility, enhancing soil immobilization of PTEs while avoiding input of AGRs following soil application of the pyrolyzed biowastes. As demonstrated in a step-wise systematic approach (Fig. 1 ), metal mobility and environmental risks assessed by sequential extraction, microbial and AGRs with specific gene target molecular assay for the wastes and the biochars, and soil and plant quality associated with health risks assessed in terms of soil fertility, PTEs toxicity and nutrition values for pot growth of a vegetable crop. This study is to provide robust but quantitative evidence on how conversion of biowastes into biochar via pyrolysis could help eliminate antibiotic resistant genes and deactivate potentially toxic metals so as to ensure soil health and safe production of vegetable crops. This could be crucial for recommending pyrolysis as a treatment tool to recycle safely these nutrient-rich organic material in agricultural soils, through improving soil fertility and plant production while minimizing the environmental and human health risks as demanded by the UN SDGs.

Fig. 1.

Research flows of the study, focusing on changes in environmental and health risks of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Biowaste feedstock collection and biochar preparation

In this study, three major types of solid biowastes were compared, using respectively wheat straw (WS) as primary crop residue, swine manure (SM) as secondary animal residue and sewage sludge (SS) as microbial residues of processed municipal waste. Feedstock of WS was collected after harvest in a household farm nearby Nanjing (32°04′04″ N, 118°58̍′09″ E), Jiangsu Province, China. Feedstocks of SM and SS were collected respectively in Yongxin Eco-farm of pig breeding (29°10′03″ N, 119°44′55″ E) and in Qiubin municipal wastewater treatment plant (29°04′32″ N, 119°36′24″ E), both located in Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, China. In the pig farm, 5000 heads as a stock of indigenous two-ends-black local genotype were bred using a commercial mixed feed pellets of Dabeinong and manure was produced following dewatering of the collected pig excretes with a screw machine. The swine manure used to be directly transported and land applied by local farmers. In the waste water treatment plant, 70 thousands of municipal waste water were biologically digested each day and the sewage sludge was landfilled after dewatering and condensation. Post-collection, the feedstocks were respectively air-dried in the local sites. After shipping to laboratory, WS was chopped into pieces in a diameter of 2–3 cm while SM and SS sieved to pass through a 2-mm sieve before further use.

Pyrolysis was operated with residence time of approximately 1 h in an oxygen-limited condition as per protocols depending on the types of the biowastes varying in chemical and organic matter composition as well as heat values (Pan et al., 2015, 2017). Briefly, WS was pyrolyzed in a bench pyrolyzer (Bian et al., 2016) at a maximum temperature of 450 °C, with energy surplus as syngas. Whereas, SM and SS were pyrolyzed in a vertical kiln at 650 °C and 800 °C (Shao et al., 2019), heating was assisted by biogas generated from waste anaerobic digestion. The conversion rate (dry base) of feedstock to biochar was 35%, 45% and 65%, respectively for WS, SM and SS. After cooling, the biochars were milled to pass a 2-mm sieve before analysis and experiment. Hereafter, the wheat straw, swine manure and sewage sludge before and after pyrolysis are referred as UWS, USM and USS, and WSB, SWB and SSB respectively.

2.2. Pot experiment

A pot experiment with a vegetable crop of pak choi (Brassica chinensis L., also known as pakchoi) was conducted in 2017. Being high in metal affinity (Khan et al., 2016), the plant was widely cropped for diet consumption in China and the world. The pot soil was from the topsoil of a clay loam Alfisol collected in a vegetable farm in suburb Nanjing (32°04′04″ N, 118°58′09″ E). After air-drying and removal of any gravel and plant debris, the collected soil was ground to pass a 2-mm sieve and homogenized before use. Soil basic properties were: pH (H2O) of 4.99, organic carbon of 11.36 g kg−1, total N of 1.52 g kg−1, available P of 42.36 mg kg−1 and available K of 140.0 mg kg−1, and total content (mg kg−1) of Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd of 26.25, 64.07, 19.49 and 0.20, respectively.

In a plastic pot in a diameter of 25 cm and height of 18 cm, 2.0 kg of the processed soil was amended at 2.0% (w/w) with a biowaste before or after pyrolysis, with a control without amendment. Then, chemical fertilizers of urea, mono-ammonium phosphate, and potassium sulfate were added in an amount respectively of 0.4 g N, 0.3 g P2O5 and 0.4 g K2O. After homogenizing, the treated soils were thoroughly wetted to field capacity. One day later, 20 pak choi seeds were sown on the soil surface in each pot. One week after germination, 5 seedlings with similar size and color were retained per pot. Pak choi were allowed to grow at a daily temperature between 20 °C and 30 °C in a greenhouse within the campus of the authors’ university, from August 14, 2017 to September 24, 2017. No additional fertilizer was added but water to maintain soil moisture of 70% field holding capacity, by weight balance every day, over the whole growing period (Liu et al., 2018). Each treatment was performed in four replicates and all the treatment pots arranged in a completely randomized block design. Other performances including weed control were consistent across the treatments.

2.3. Sampling of plant and soil

Following growth for 40 days, all the aboveground biomass of pak choi of each pot was collected and weighed for fresh biomass yield, and subsequently cut into pieces, homogenized and divided into two random portions. One portion was refrigerated at 4 °C before being pulverized with a vegetable crusher for nutrition quality analysis. Another portion was dried in an air-convection oven firstly at 105 °C for 30 min then at 60 °C for another 48 h (Lu, 2000), and subsequently ground to pass through a 0.5-mm sieve and homogenized for chemical analysis of major nutrients and PTEs.

At plant harvest, all the soil in a pot was removed, from which plant roots and visible debris were all carefully picked out. The soil mass was then homogenized and quartered into portions. One random portion was freeze-dried and stored at −80 °C for DNA extraction while the others pooled and air-dried prior to chemical analysis. Analysis of soil basic physico-chemical properties, and total and fractions of heavy metals were all performed as per the methods outlined in Section 2.4.

2.4. Analysis of the biowastes, plant and soil

In this study, chemical analysis of the samples of biowastes before and after pyrolysis, and of soil and plant was performed basically following the methods described in detail by Lu (2000). The pH and electrical conductivity (EC) (for biowastes only) were measured in a suspension with a pH conductivity meter (Seven Easy Metter Toledo, China). Thereby, the ratio of a test material to water in the suspension was 1:20 (w/v) except 1:5 (w/v) for USS and SSB. Soil organic carbon (SOC) content was determined using wet digestion with potassium dichromate oxidation. Total contents of N, P and K were determined respectively with semi-Kjeldahl method, colorimetry and flame spectrometer following digestion with H2O2–H2SO4. For USS and SSB, however, total contents of P and K were determined following NaOH digestion.

Total concentration of PTEs including Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd was determined for the biowastes and soil as well as plant samples. For this, a sample was digested with mixed solution of HNO3–HClO4–HF for biowaste and soil, but with a mixed solution of HNO3–HClO4 for plant (Lu, 2000). Available pool of a PTE was determined for the biowastes and pot soil samples following extraction with 0.01 M CaCl2 solution by shaking for 2 h and subsequent filtering through a 90 mm filter paper.

Based on Ure et al. (1993), a modified BCR sequential extraction protocol was used for chemical fractionation of a PTE in the biowastes before and after pyrolysis, outlined as follows. A portion of a sample (0.5 g dry weight equivalent) was placed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, extracted firstly by 20 mL of 0.1 mol L−1 acetic acid to obtain the exchangeable fraction (F1) as the supernatant after shaking for 16 h at 25 °C. The residual in the tube was then extracted with 20 mL hydroxylamine (0.1 M, pH 2.0) for 16 h at 25 °C and the supernatant collected as the reducible fraction (F2) for metals with Fe/Mn oxyhydroxides. To obtain the oxidizable fraction (F3) of metals bound to organic matter and/or sulfides, the residual after F2 was firstly reacted with 5 mL hydrogen peroxide (30%, v/v) by shaking for 1 h at 25 °C, followed by reaction with another 5 mL hydrogen peroxide (30%, v/v) by shaking for 1 h at 85 °C, subsequently dried in a water bath before another reaction with 25 mL ammonium acetate (1 M, pH 2.0) by shaking for 1 h at 25 °C. Finally, the residue was extracted with 10 mL HNO3–HClO4 (4:1, v/v) for UWS, WSN, USM and SMB, or with 15 mL HF– HNO3– HClO4 (4:1:1, v/v) for USS and SSB, to obtain the residual fraction (F4) of metals existed in mineral phase.

The solubility products of PTEs were measured of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis, with the modified toxicity characteristic leaching procedure (TCLP) based on USEPA1311 method (Halim et al., 2003). Briefly, a portion of a sample (1.00 g of dry weight equivalent) was soaked in 20 mL unbuffered glacial acetic acid solution (pH 2.88) for 18 h, and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. After filtering through a 0.45 μm membrane, the solution was collected for metal content determination.

For metal contents of the digestions/extractions obtained above, Cu and Zn, and Pb and Cd were determined respectively with flame and graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS/GFAAS, A3, Persee, Analytical Instruments, China). Analytical quality was guaranteed using certified reference materials GSS-1 for USS, SSB and soil samples, and GBW(E) 080684 for other biowastes and plant samples. These reference materials were provided by the Chinese National Research Center for Standards. Recovery of the analyzed metals was in a range of 89%–109%. For samples of plant collected at harvest in the pot experiment, content of soluble sugar, total protein and nitrate was determined with colorimetry respectively using the anthrone method, Coomassie brilliant blue method and salicylic acid method. Content of vitamin C (Vc) was determined using the titration method.

In addition, the biowaste samples were examined for surface morphology with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (S3400, Hitachi, Japan) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). For the biochars after pyrolysis, surface area (SA) was determined using N2 sorption isotherm run on NOVA 1200 and the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method with Flow Sorb II 2300 (Micromeritics, Aachen, Germany). Meanwhile, cation exchange capacity was measured with a modified ammonium-acetate compulsory displacement method (Gaskin et al., 2008).

2.5. DNA extraction and quantification of bio-waste and soil

Samples of SM and SS before and after pyrolysis, and the amended pot soils were analyzed for abundance of microbial genes and ARGs. For this, 0.25 g of a sample was extracted with a FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After qualitative detection using standard PCR described in the Supporting Information (Table S1), bacterial 16s rDNA, fungal 18s rDNA, five tetracycline genes (tetC, tetG, tetM, tetO, tetW), two sulfonamide genes (sul1 and sul 2) and one class 1 integron-integrase gene (intI1) with bright target bands were analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using QuantStudio ® 5 Real-Time PCR systems (Thermo Fisher) (Panda et al., 2017). The reaction mixture consisted of 0.4 μL of 20 pM of each primer, 10 μL of SYBR Green II master mix and 2 μL of template DNA in a total volume of 20 μL. And the conditions as following: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min and 40 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, annealing for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Absolute copy numbers of the genes in the samples were calculated using the external standard curve method, which was generated by a 10-fold serial dilution of plasmid DNA (R2 ≥ 0.990). The amplification efficiency of each pair of primer was between 87 and 110%.

2.6. Data processing and statistical analysis

For assessing the environmental and health risks of soil and plant treated with the biowastes, a number of dimensionless indices were estimated as follows.

The risk assessment code (RAC) was estimated with the portion of exchangeable fraction to the total of a heavy metal (Singh et al., 2005):

| (1) |

where, C F1 and C t is respectively the content of extractable fraction with acetic acid and the total content of a metal in a material, obtained as per BCR procedure in Section 2.4. A PTE in a material is concerned as no, low, medium, high and very high risk with a RAC value of <1, 1–10, 11–30, 31–50 and > 50, respectively.

A biological concentration factor (BCF) for plant metal accumulation over soil was calculated following Alloway et al. (1990), as follows:

| (2) |

where, Cp and Cs represents the metal concentration respectively of fresh aboveground plant and of dry soil.

For characterizing the overall soil quality or plant quality, a value of normalized quality index (NQI) was estimated following the estimation of overall soil extracellular enzyme activities (Jin et al., 2012), calculated using the equation as:

| (3) |

where, is the value of a quality parameter measured of a sample i, N is the number of total treatments, is the normalized (dimensionless) value of the analyzed parameter of the sample. Subsequently, all the values individually obtained for the measured parameters (for example, 4 parameters of plant concentration of Vc, soluble sugar, soluble protein and nitrate for plant nutrition quality and other 4 parameters of total plant concentration of Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd) were added up for an overall quality of each sample. Hereby, a parameter was assigned positive or negative regarded with nutrition or health effect and weighted by factors as per their general importance.

Lastly, a dimensionless parameter of target hazard quotient (THQ) (US EPA, 2002) was used to assess a potential health risk for adult via food exposure to pak choi, calculated with the equation:

| (4) |

where, E D and E F is the vegetable exposure duration and frequency respectively of 70 years in life and 365 days of a year; F IR is the ingestion rate of 242.0 g day−1 (Yu et al., 2016); C M represents the measured concentration (mg kg−1) of a PTE in vegetable; W AB is the average body weight of 56.8 kg (MEPC, 2014); ATn is the average exposure time for non-carcinogens; R fD is the oral reference dose of 0.04, 0.30, 0.004 and 0.001 mg kg−1 day−1 respectively for Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd (US EPA, 2007). A potential health risk is denoted unlikely at THQ < 1 but significant at THQ ≥1 (Wang et al., 2005).

Finally, the calculated THQ values individually of Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd were added up to give an overall potential health risk (THQ total) via food exposure to pak choi.

All the data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and processed with Excel 2016. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 22. Data means of biowaste between before and after pyrolysis, and among the amendment treatments were tested for difference with one-way ANOVA. Multiple comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s test to determine the significance of difference between the biowaste types or among amendment treatments. Pearson’s correlation was also performed for relationships between/among the analyzed parameters. A difference or a correlation was considered significant at p < 0.05, as per the relevant statistical protocols.

3. Results

3.1. Physico-chemical properties of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis

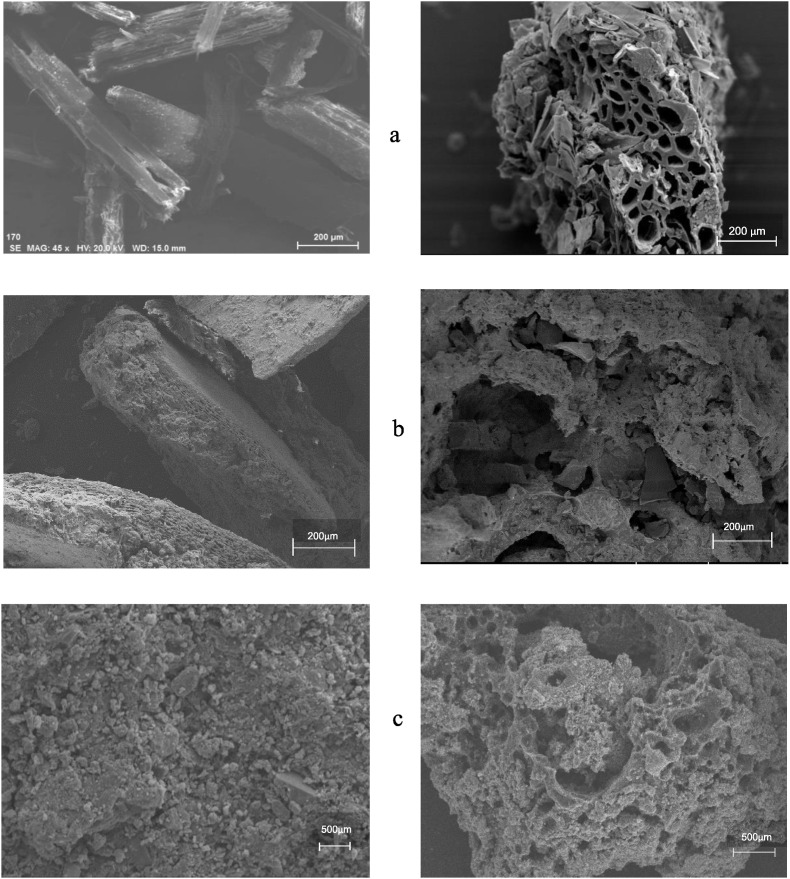

The basic properties are presented in Table 1 and the SEM images in Fig. 2 , of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis. UWS and USM seemed soft and more or less porous. After pyrolysis, their biochars had markedly higher porosity of nano-pores, with a surface area in a range of 6–20 m2 g−1. In comparison to before pyrolysis, the pH of biochars was all significantly (p < 0.05) higher by 2.6–3.9 units while EC was significantly (p < 0.05) higher by almost 80% for WSB but lower by 30% and 90% for SMB and SSB, respectively. Total OC was significantly (p < 0.05) increased by 27% for WSB but decreased for SMB by 14% and SSB by 12%. Being different, total N was insignificantly (p > 0.05) increased for WSB but significantly (p < 0.05) decreased by almost 50% for SMB and SSB, respectively compared to their feedstock. Whereas, total K after pyrolysis was almost doubled (p < 0.01) as before pyrolysis. Moreover, total P was unchanged (p > 0.05) in WSB but significantly (p < 0.05) increased by almost 40% in SMB and by 20% in SSB over their feedstock. In contrast, ash content was seen very significantly (p < 0.01) increased by 2–3 folds in WSB and SMB and by 80% in SSB, respectively compared to the feedstocks. As per the EDS spectra coupled with SEM provided in Fig. S1, more elements were detectable in high intensity in the biowastes after pyrolysis than before, including Mg, Cu and Zn from wheat residue, and Ti and Cu from swine manure.

Table 1.

Basic physico-chemical properties of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis used in this study.

| Sample | pH (H2O) | EC (us cm−1) | SA (m2 g−1) | Total OC (g kg−1) | Total N (g kg−1) | Total K (g kg−1) | Total P (g kg−1) | CEC (coml kg−1) | Ash (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UWS | 7.66 ± 0.01 b | 1999 ± 1.41 b | n.d. | 447.48 ± 10.57 b | 6.12 ± 0.98a | 7.93 ± 0.07 b | 3.25 ± 0.76a | n.d. | 7.53 ± 0.04 b |

| WSB | 10.30 ± 0.01a | 3575 ± 7.07a | 21.64 | 670.09 ± 3.02a | 7.51 ± 0.5a | 20.4 ± 1.34a | 2.16 ± 0.61a | 92.75 ± 15.71 | 27.81 ± 0.53a |

| USM | 7.17 ± 0.02 b | 4215 ± 35.36a | n.d. | 425.15 ± 9.41a | 41.17 ± 2.26a | 9.6 ± 0.54 b | 31.02 ± 2.74 b | n.d. | 14.01 ± 0.55 b |

| SMB | 10.54 ± 0.23a | 2720 ± 28.28 b | 5.87 | 364.04 ± 4.89 b | 18.74 ± 0.08 b | 20.89 ± 0.44a | 42.91 ± 1.42a | 34.56 ± 2.63 | 52.93 ± 0.18a |

| USS | 5.2 ± 0.05 b | 8325 ± 21.21a | n.d. | 153.64 ± 8.85a | 23.75 ± 0.55a | 3.67 ± 0.27 b | 26.17 ± 0.28 b | 29.80 ± 2.37a | 53.62 ± 0.09 b |

| SSB | 9.06 ± 0.04a | 366.5 ± 3.54 b | 19.66 | 135.59 ± 2.98 b | 12.35 ± 0.08 b | 5.92 ± 0.02a | 31.03 ± 1.95a | 10.65 ± 1.57 b | 83.38 ± 0.23a |

Data as mean ± standard deviation. UWS, USM and USS, and WSB, SMB and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis; EC, electric conductivity; SA, surface area; OC, organic carbon; CEC, cation exchange capacity. n.d., not determined. Different lowercase letters in a pair of biowaste in a single column represent a significant difference at p < 0.05 between before and after pyrolysis (One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test).

Fig. 2.

SEM images of wheat residue (a), swine manure (b) and sewage sludge (c) respectively before (left) and after (right) pyrolysis.

3.2. Total and fractions of heavy metals in biowastes before and after pyrolysis

Data of total, CaCl2 −extractable and TCLP leachable pool of the analyzed PTEs in the biowastes before and after pyrolysis are exhibited in Table 2 . The biowastes before pyrolysis were found very high level of Cu up to 649 mg kg−1 and Zn up to 4136 mg kg−1 in USM, and of Cu up to 1353 mg kg−1 and Zn up to 1161 mg kg−1 in USS, despite of a very small (<15 mg kg−1) amount in UWS. Levels of Pb and Cd, whereas, were relatively low in UWS (<1 mg kg−1 for Pb and <0.1 mg kg−1 for Cd) and USM (<1 mg kg−1 for Pb and <0.5 mg kg−1 for Cd) but reached 390 mg kg−1 for Pb and 25 mg kg−1 for Cd in USS. All the biowastes before pyrolysis contained significant amounts of CaCl2-extractable pool of Cu and Zn, ranging from about 1 mg kg−1 with wheat residue to over 150 mg kg−1 with swine manure. Comparatively, the CaCl2-extractable pool of both Pb and Cd was generally smaller than 0.1 mg kg−1 despite of 0.43 for Pb in USM only. However, there was a much greater variation of the portion of CaCl2 −extractable pool to total of the PTEs in the biowastes before pyrolysis. The portion was under 3% for all the PTEs in USS and in a range of 5%–45% for Cu, Zn and Pb in UWS and USM though nearly 70% for Cd in UWS. The TCLP mobility pool was small (0.01–4.02 mg kg−1) again for all the PTEs in UWS while USM and USS exerted a high mobility pool for Cu and Zn (79–1032 mg kg−1) though small or insignificant for Pb and Cd (up to 2.4 mg kg−1 in USS). Unlike the CaCl2 extractable portion, the portion of TCLP mobility pool to the total was 20%–35% for Cu and Zn, 5%–10% for Pb and Cd in UWS and USM. In USS, however, this portion was small (0–10%) for Cu, Pb and Cd except over 25% for Zn.

Table 2.

Pool (mg kg−1) of total, CaCl2 extractable and TCLP leachable heavy metals of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis.

| Pool | Material | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | UWS | 4.02 ± 0.09 b | 14.83 ± 0.31 b | 0.95 ± 0.05 b | 0.07 ± 0.02 b |

| WSB | 13.63 ± 0.00a | 48.67 ± 3.91a | 3.19 ± 0.38a | 0.17 ± 0.00a | |

| USM | 649.4 ± 40.13 b | 4136.3 ± 9.09 b | 0.95 ± 0.04 b | 0.34 ± 0.01 b | |

| SMB | 1434.0 ± 31.6a | 6881.3 ± 89.3a | 4.23 ± 0.42a | 0.43 ± 0.02a | |

| USS | 1353.0 ± 74.1 b | 1161.4 ± 38.1 b | 389.6 ± 12.6 b | 24.69 ± 2.34a | |

| SSB | 1857.0 ± 29.8a | 2069.9 ± 46.7a | 518.7 ± 4.34a | 16.67 ± 0.31 b | |

| CaCl2 | UWS | 0.61 ± 0.04a | 1.16 ± 0.00a | 0.08 ± 0.00a | 0.05 ± 0.00a |

| WSB | 0.05 ± 0.00 b | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 0.07 ± 0.00a | 0.03 ± 0.00 b | |

| USM | 165.2 ± 3.54a | 222.5 ± 6.01a | 0.43 ± 0.00a | 0.09 ± 0.00a | |

| SMB | 0.76 ± 0.08 b | 2.03 ± 0.03 b | 0.26 ± 0.02 b | 0.09 ± 0.00 b | |

| USS | 5.13 ± 0.00a | 40.25 ± 0.42a | 0.03 ± 0.00a | 0.27 ± 0.02a | |

| SSB | 0.05 ± 0.00 b | 0.08 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 0.09 ± 0.00 b | |

| TCLP | UWS | 0.83 ± 0.03a | 4.02 ± 0.04a | 0.07 ± 0.01a | 0.01 ± 0.00a |

| WSB | 0.46 ± 0.04 b | 2.69 ± 0.49 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | |

| USM | 232.9 ± 5.01a | 1032.5 ± 37.9a | 0.04 ± 0.00a | 0.02 ± 0.00a | |

| SMB | 7.77 ± 0.26 b | 131.7 ± 1.80 b | 0.01 ± 0.001 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 b | |

| USS | 78.95 ± 1.99a | 297.0 ± 4.24a | 1.08 ± 0.02a | 2.36 ± 0.01a | |

| SSB | 4.34 ± 0.15 b | 53.86 ± 1.23 b | 0.69 ± 0.03 b | 2.07 ± 0.01 b |

Data as mean ± standard deviation. UWS, USM and USS, and WSB, SMB and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis; Different lowercase letters in a single biowaste pair represent a significant difference at p < 0.05 between before and after pyrolysis (One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test).

Compared to before pyrolysis, the PTEs were all highly (p < 0.01) concentrated in the biochars after biowaste pyrolysis, except for Cd reduction in SSB. In contrast, in a small portion (<6%) to total, CaCl2-extractable pool was small (<1 mg kg−1) for the PTEs in the biochars except 2.0 mg kg−1 for Zn in SMB. After pyrolysis, CaCl2-extractable pool of Cu and Zn was very significantly (p < 0.01) reduced, by >90% in WS, by >99% in the SM and SS. Relatively, this pool of Pb and Cd was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced by 10–67% in the biochars though that of Cd unchanged (p > 0.05) in SMB.

Comparatively, the TCLP mobility pool of Cu and Zn, both in significant amount, was reduced by 30% in WS (p < 0.05), and by >80% (p < 0.01) in SM and SS, after pyrolysis. Similarly, this pool of Pb was very significantly (p < 0.01) and of Cd significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in the biochars. Moreover, the portion of the CaCl2-extractable pool to the total was <0.5% for Cu and Zn, 0–6% for Pb and 0.5–21% for Cd, while that of TCLP pool was 0.2–5.5% for Cu and Zn, 0.1–0.6% for Pb and 1.2–12% for Cd, in the bicohars. After pyrolysis, PTEs’ availability (the portion of CaCl2 portion to total) was very significantly (p < 0.01) but greatly reduced by over 97% for Cu and Zn, by 74–86% for Pb but by 21% (in SMB) −75% for Cd. Coincidently, the leaching potential, the portion of TCLP pool to total, was very significantly (p < 0.01) but greatly reduced by 80–98% for Cu, Zn and Pb in all biochars except by 50% for Pb in SSB. That of Cd, however, was significantly (p < 0.01) lowered by 59% in WSB and 80% in SMB despite of a significant (p < 0.05) 25% increase in SSB.

The proportions of PTEs chemical fractions for the biowastes before and after pyrolysis are plotted in Fig. 3 , with the original measurement data presented in Table S2. The speciation procedure yielded a recovery between 95.55 and 108.7% for Cu, 84.5–113.2% for Zn, 99.7–112.9% for Pb and 88.1–108.3% for Cd, respectively. Proportions of the different fractions to the total varied divergently either with metals or with biowaste types. Before pyrolysis, total Cu composed mainly of F1, F2 and F3, in proportions varying from 10% to 50%, with a small F4 fraction increasing from zero in UWS to 10% in USS. Total Zn, whereas, composed mainly F1, F2 and F4 with a small proportion of F2 though 2% of F3 and F4 in USM. Differently, total Pb in UWS and USM was comprised predominantly of F3 and F4 (30–60%) with a small proportion of F1 and F2 but of F4 (95%) in USS. In contrast, total Cd was substantially contributed by F2 (44–54%) and F4 (27–47%) with a small (<15%) proportion of F1, in the bio-wastes before pyrolysis. Across the PTEs, proportion of F1 was higher in USM except Cd while that of F4 lower in UWS except Zn, among the unpyrolyzed biowastes.

Fig. 3.

Metal speciation of Cu (a), Zn (b), Pb (c) and Cd (d) of wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge before (left) and after (right) pyrolysis. F1, exchangeable fraction; F2, reducible fraction; F3, OM bound fraction; F4, (mineral) residual fraction. UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue; swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis.

After pyrolysis, proportion of F1, F2, F3 and F4 was respectively 8.4%, 21.8%, 28.2% and 41.7%, on average of all the PTEs. In detail, the F1 proportion of the PTEs in the biochars became significantly low (mostly 0.1–8.3%) except Zn in WSB and SMB, and Cd in SSB (16%–40%), which existed mostly as salt as per the high ECs (Table 1). Meanwhile, the F2 proportion was divergent, being as low as 0.8% for Cu in SSB but as high as 59% for Cd in SMB. Whereas, the F3 fraction generally had a proportion of 10%–20% though this fraction was in a high range of 48%–68% for Cu in SMB and SSB, and for Pb in WSB. Being less variable, the proportion of F4 was high up to 50%–86% for Cu in WSB, Zn in WSB and SSB, and Pb in SMB and SSB, with the others in a range of 17%–35%. Overall, the proportions of F1 and F2 were more variable but reduced (p < 0.05) both by 9% while those of F3 and F4 less variable but increased (p < 0.05) respectively by 7% and 11%, in biochars compared to the bio-wastes before pyrolysis.

RAC values calculated with Eq. (1) are provided in Fig. S2. For the biowastes before pyrolysis, no potential environment risk (RAC <1) was assigned to Pb in SS only while a low risk (RAC 1–10) to Pb and Cd in UWS and USM, and to Cu in UWS. Whereas, a medium risk (RAC 11–30) was seen both of Cu and Cd in USS and of Zn in UWS but a high risk (RAC 31–50) of Cu in USM and of Zn in USS. Yet, a very high (RAC >50) risk was observed of Zn in USM only. In all the biochars, differently, Pb showed no risks and Cu a low risk but Zn exerted a low risk in SSB, a medium risk in WSB and a high risk only in SMB. Lastly, Cd was shown generally no risk or low risk in the biochars except a medium risk in SSB only. Accounting for all the RAC values by the individual PTEs, the biochars of WSB and SSB exerted an overall low environmental risk (RAC of 5–7) though SMB a medium risk compared to an overall medium risk (RAC of 10–30) for all the biowastes before pyrolysis. Thus, the overall PTEs environmental risk by the biowastes declined very significantly (p < 0.01) and moderately to greatly following pyrolysis (Fig. S2).

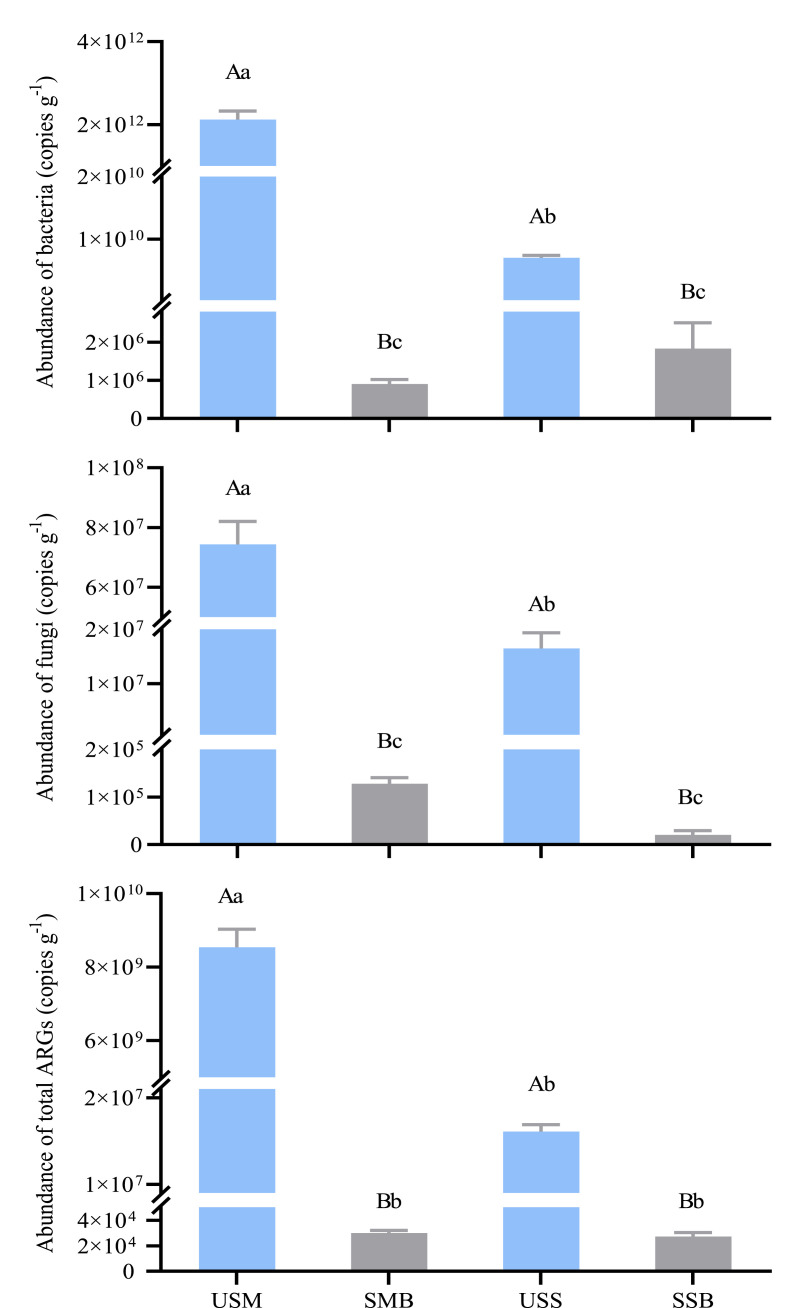

3.3. Abundance of microbial genes and ARGs

For the biowastes of SM and SS, data of gene abundance of microbial communities and total ARGs are shown in Fig. 4 . Before pyrolysis, gene abundance (copies g−1) of bacterial was 2.1 × 1012 and 7.0 × 109 and that of fungi 7.4 × 107 and 1.6 × 107, respectively in SM and SS. With individual genes varied in a wide range of 103 -109 copies g−1 (Table S3), total ARGs was 8.5 × 109 in SM and 1.6 × 107 in SS. Overall, bacterial and ARGs gene abundance as well as bacterial to fungal ratio was higher by almost 2 orders in SM than in SS.

Fig. 4.

Abundances of microbial genes and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) detected in the biowastes. a, Bacteria; b, Fungi; c, genes related to antibiotic resistance (ARGs and intI1). USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis. Different uppercase letters above the bars in a single pair of amendment and different lowercase letters above all the bars, represents a significant difference at p < 0.05 (One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test) between before and after pyrolysis, and among all the treatments, respectively.

After pyrolysis, whereas, gene abundance (copies g−1) of bacterial was 9.0 × 105 in SMB and 1.8 × 106 in SSB while that of fungal was 2.0 × 104 in SMB and 1.3 × 105 in SSB. Both in SSB and SMB, gene abundance (copies g−1) of individual ARGs was all very low (Table S3), at levels of 2.3 × 102 to 6.8 × 103 while sul1 gene undetected. Unlike the biowastes before pyrolysis, there was no difference in microbial and total ARG abundance between SMB and SSB though bacterial to fungal ratio was relatively higher in SSB than in SMB. After pyrolysis, abundances of microbial and ARGs in the biowastes declined by over 99.8% and bacterial to fungal ratio by over 80%.

3.4. Nutrients, heavy metals and microbial genes in biowaste amended pot soil

Data of soil fertility changes following amendment of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis are organized in Table 3 . Under biowaste amendment compared to no amendment (CK), significantly (p < 0.05) positive changes were found for soil pH, SOC, and C/N ratio, at varying extents with different parameters and the biowaste types. Whereas, total N and available P were insignificantly (p > 0.05) or slightly increased under WS and SS regardless of pyrolysis. Differently, total N, available K and P were all moderately to greatly enhanced (p < 0.05) under SM regardless of pyrolysis. Comparing the biowastes before and after pyrolysis, soil pH was increased by 0.2–0.3 units under all the biochars than the biowastes unpyrolyzed. But increases in SOC, available K and P were significantly (p < 0.05) higher by 20–40% under SWB and SMB respectively compared to UWS and USM though similar between USS and SSB. No differences (p > 0.05) in these parameters were observed between USS and SSB. Also, total N was 12% lower (p < 0.05) under SMB and SSB compared to USM and USS, respectively.

Table 3.

Soil properties at pak choi harvest under amendment treatments of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis in pot experiment.

| Treat-ment | pH (H2O) | SOC (g kg−1) | Total N (g kg−1) | Available K (mg kg−1) | Available P (mg kg−1) | C/N ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 4.81 ± 0.03e | 10.96 ± 0.68 d | 1.51 ± 0.06 d | 148.5 ± 9.22 d | 75.5 ± 6.05 d | 7.28 ± 0.36 d |

| UWS | 5.03 ± 0.03Bd | 14.96 ± 0.36Bc | 1.55 ± 0.03Acd | 236.8 ± 10.7Bc | 73.0 ± 2.93Bd | 9.63 ± 0.36Bbc |

| WSB | 5.19 ± 0.04Ac | 21.00 ± 0.82Aa | 1.55 ± 0.02Acd | 326.3 ± 13.1Aa | 97.1 ± 9.84Ac | 13.58 ± 0.56Aa |

| UMS | 5.25 ± 0.02Bc | 14.09 ± 0.29Bc | 1.95 ± 0.09Aa | 268.0 ± 6.82Bb | 154.1 ± 12.7Bb | 7.24 ± 0.42Bd |

| SMB | 5.49 ± 0.06Aa | 17.37 ± 0.39Ab | 1.72 ± 0.13Bbc | 320.0 ± 11.8Aa | 186.9 ± 15.3Aa | 10.17 ± 0.95Ab |

| USS | 5.02 ± 0.04Bd | 14.86 ± 0.34Ac | 1.74 ± 0.07Ab | 155.6 ± 4.26Ad | 87.0 ± 8.08Acd | 8.53 ± 0.16Acd |

| SSB | 5.35 ± 0.04Ab | 13.68 ± 0.77Ac | 1.53 ± 0.10Bd | 144.6 ± 14.8Ad | 73.7 ± 4.48Bd | 9.00 ± 0.86 Abc |

Data of the mean ± standard deviation. CK, control; UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge, respectively before and after pyrolysis. Different uppercase letters following a single pair of amendment in a single column represents a significant difference of the bio-waste between before and after pyrolysis while different lowercase letters in a single column represent a significant difference among all the treatments, respectively at p < 0.05(One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test).

In Table 4 are presented the data of total and extractable heavy metals in the pot soil following amendment with the biowastes before or after pyrolysis. Compared to CK, soil total content of the PTEs was significantly (p < 0.05) increased at varying extents under all amendments despite unchanged (p > 0.05) under UWS. The increases of Cu, Zn and Pb contents under the biochars were significantly (p < 0.05) higher by 16–53% than under unpyrolyzed biowastes, corresponding generally to the metal contents of an amended biowaste. In detail, total Cu was increased significantly (p < 0.05) by 50–70% under USM and USS, but very significantly (p < 0.01) by 123% and 170% under SMB and SSB, respectively. Differently, total Cd was very significantly (p < 0.01) increased by 105% under USS and 137% under SSB.

Table 4.

Total and CaCl2-extractable heavy metals of pot soil collected at pak choi harvest under amendment of biowastes before and after pyrolysis.

| Amend-ment | Total (mg kg−1) |

CaCl2-extractable (mg kg−1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | Cu | Zn | Pb | Cd | |

| CK | 21.90 ± 0.79e | 66.50 ± 6.85cd | 19.69 ± 1.76bc | 0.19 ± 0.02 d | 0.07 ± 0.02c | 1.01 ± 0.02 d | 0.01 ± 0.01bc | 0.04 ± 0.00c |

| UWS | 21.30 ± 1.14Ae | 60.15 ± 8.78Bd | 18.16 ± 0.83Bc | 0.17 ± 0.01Ad | 0.11 ± 0.01Ab | 0.52 ± 0.17Ae | 0.02 ± 0.00Ab | 0.02 ± 0.01Ad |

| WSB | 22.28 ± 1.44Ae | 79.05 ± 7.18Ac | 22.23 ± 1.74Ab | 0.18 ± 0.01Ad | 0.11 ± 0.01Ab | 0.41 ± 0.08Ae | 0.02 ± 0.01Ab | 0.02 ± 0.00Ad |

| USM | 32.69 ± 1.16Bd | 126.6 ± 14.11Bb | 21.03 ± 2.26Ab | 0.18 ± 0.01Bd | 0.80 ± 0.06Aa | 6.26 ± 0.14Aa | 0.04 ± 0.00Aa | 0.01 ± 0.00Ae |

| SMB | 48.80 ± 2.50Ab | 206.5 ± 15.10Aa | 22.69 ± 0.97Ab | 0.23 ± 0.01Ac | 0.12 ± 0.05Bb | 2.99 ± 0.15Bb | 0.01 ± 0.00Bc | 0.01 ± 0.00Ae |

| USS | 39.38 ± 2.31Bc | 104.75 ± 7.92Ab | 24.84 ± 2.51 Bab | 0.39 ± 0.03Bb | 0.14 ± 0.05Ab | 3.19 ± 0.21Ab | 0.01 ± 0.00Ac | 0.08 ± 0.00Aa |

| SSB | 58.56 ± 4.31Aa | 109.6 ± 8.69Ab | 30.14 ± 3.94Aa | 0.45 ± 0.01Aa | 0.09 ± 0.03 Abc | 1.13 ± 0.05Bc | 0.01 ± 0.00Ac | 0.06 ± 0.00Bb |

Data as mean ± standard deviation of four replicates of a treatment. CK, control; UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis. In a single column, different uppercase letters following a single pair of amendment and different lowercase letters across the column represents a significant difference at p < 0.05 between before and after pyrolysis, and among all the treatments, respectively(One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test).

However, changes in available pool of the metals did not follow a similar trend. Firstly, available pool of Pb in the amended soil was very small, in a range of 0.01–0.04 mg kg−1, regardless of the pyrolysis treatments. Being also small, available pool of Cd was significantly (p < 0.05) increased under USS but reduced under UWS and USM, Meanwhile, available Cu and Zn was unchanged (p > 0.05) or reduced (p < 0.05) under UWS but greatly (p < 0.01) increased (by folds) under both USM and USS, relevant to their high available pool (Table 2). However, these available pools were all significantly (p < 0.05) lower under the biochars than under unpyrolyzed biowastes. Moreover, the portion of available pool of these metals was found either unchanged (p > 0.05) or reduced significantly (p < 0.05) under the biochar amendments despite of a significant increase for Zn under SMB and for Cd under SSB, respectively over amendment of the biowastes before pyrolysis.

3.5. Abundance of microbial genes and ARGs in amended pot soil

Abundances of the microbial genes and total ARGs in pot soil following amendment are shown in Fig. 5 , with original data of the individual ARGs given in Table S4. Gene abundances (copies g−1) of both bacteria and fungi were significantly (p < 0.05) increased by 3–10 folds under UWS (3.3 × 1012 and 6.6 × 109), and under USM (3.70 × 1012 and 4.20 × 109) but insignificantly (p > 0.05) changed under other amendments, compared to CK without amendment (7.6 × 1011 and 2.6 × 108). While no difference between USS and SSB, a great reduction (p < 0.05) of gene abundance was observed by >60% for bacterial and by >90% for fungal under WSB and SMB respectively compared to under UWS and USM. Moreover, gene abundance ratio of fungi to bacteria (F/B) was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced under the biochar amendments while increased under UWS and USM with no change (p > 0.05) under USS, over the control. Accordingly, B/F ratio was significantly (p < 0.05) higher under WSB and SWB but lower under SSB, compared to the relevant biowaste before pyrolysis.

Fig. 5.

Abundances of bacterial (a), fungal (b) genes and total antibiotics resistance genes (ARGs and intI1) (c) in pot soil under amendment treatments. CK, control; UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis. Different uppercase letters above the bars in a single pair of amendment and different lowercase letters above all the bars, represents a significant difference at p < 0.05 (One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test) between before and after pyrolysis, and among all the treatments, respectively.

Also shown in Fig. 5, total abundance (copies g−1) of ARGs in the pot soil after amendment was in a range of 2.9 × 107 to 4.9 × 107. Over CK, the total ARGs gene abundance was unchanged (p > 0.05) with all the amendments other than USM. Notably, soil total abundance of ARGs was found as low as 3.8 × 107 under SMB compared to 4.9 × 108 under USM with high abundance (up to 109 copies g−1) in the material. Specifically, the intI1 gene abundance (copies g−1) was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced by 80% under SMB (7.1 × 106) over USM (3.5 × 107) (Table S4).

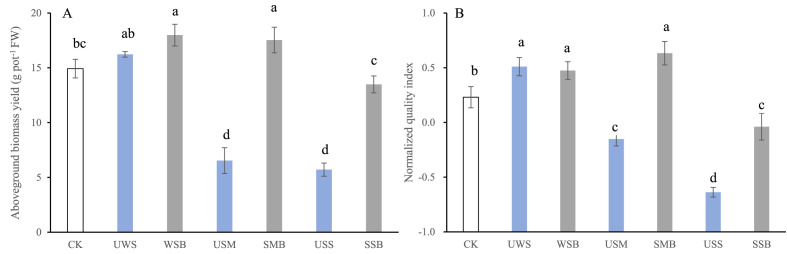

3.6. Plant growth, yield and health-related quality

The biomass yield and overall quality of pak choi grown in the soil amended with the unpyrolyzed and pyrolyzed biowastes are organized in Fig. 6 , with the original nutrition quality in Table 5 . Respectively compared to CK, aboveground biomass yield was significantly (p < 0.05) decreased by 56.2% and 61.7% under USM and USS while increased by 20.6% and 17.5% under WSB and SMB though unchanged (p > 0.05) under UWS and SSB. Vc content was unchanged (p > 0.05) or significantly (p < 0.05) increased under the amendments despite of a decrease (p < 0.05) under USS only, compared to CK. However, contents of soluble sugar, protein and nitrate were divergent among the treatments. Overall, SM and SS after pyrolysis moderately (p < 0.05) increased though pyrolyzed WS unchanged (p > 0.05) the normalized nutrition quality index, respectively compared to before pyrolysis.

Fig. 6.

Aboveground biomass yield (a) and overall quality index (b) of harvested pak choi grown 40 days in pot soil under amendment of bio-wastes before (green) and after (gray) pyrolysis, compared to control (blank); CK, control; UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis. Different uppercase letters above the bars in a single pair of amendment and different lowercase letters above all the bars, represents a significant difference at p < 0.05 (One-way ANOVA) between before and after pyrolysis, and among all the treatments, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 5.

Properties of nutrition quality and metal contents of fresh pak choi at harvest under amendment of the biowastes before and after pyrolysis.

| Treat-ment | Vitamin C (mg 100g−1) | Sugar (g kg−1) | Protein (g kg−1) | Nitrate (mg kg−1) | Cu (mg kg−1) | Zn (mg kg−1) | Pb (mg kg−1) | Cd (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 78.15 ± 4.23c | 1.39 ± 0.17a | 15.27 ± 0.56 bc | 1336.0 ± 128.1a | 0.38 ± 0.06 b | 7.45 ± 0.88 c | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.07 ± 0.01 c |

| UWS | 101.9 ± 3.36 Ab | 1.47 ± 0.25Aa | 16.38 ± 1.17Aab | 1117.5 ± 165.4Aa | 0.26 ± 0.03 Ac | 4.34 ± 0.30 Ad | 0.05 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.07 ± 0.01Ac |

| WSB | 89.30 ± 7.21Bbc | 1.63 ± 0.16 Aa | 16.13 ± 1.79Aabc | 1331.7 ± 129.5Aa | 0.25 ± 0.03 Ac | 3.74 ± 0.64 Ad | 0.05 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.05 ± 0.01Bd |

| USM | 75.57 ± 3.14Bc | 1.49 ± 0.12Aa | 15.64 ± 0.44 Abc | 1380.6 ± 38.01Aa | 0.81 ± 0.04Aa | 26.76 ± 2.32 Aa | 0.06 ± 0.00 Aa | 0.07 ± 0.00Ac |

| SMB | 139.8 ± 11.62Aa | 1.49 ± 0.14Aa | 16.04 ± 0.43Aabc | 1310.7 ± 119.7Aa | 0.47 ± 0.06Bb | 15.83 ± 2.04 Bb | 0.06 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.03 ± 0.00Be |

| USS | 42.22 ± 1.19Bd | 1.50 ± 0.06Aa | 13.99 ± 0.55Bc | 1398.2 ± 41.25Aa | 0.70 ± 0.02Aa | 17.68 ± 1.04 Ab | 0.04 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.21 ± 0.01Aa |

| SSB | 88.12 ± 6.60 Abc | 1.47 ± 0.13Aa | 18.07 ± 1.33Aa | 1236.4 ± 15.56Ba | 0.69 ± 0.13Aa | 9.68 ± 2.07 Bc | 0.05 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.16 ± 0.02Bb |

Data as mean ± standard deviation of four replicates of a treatment. Sugar and protein both tested in soluble form. CK, control; UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis. In a single column, different uppercase letters following a single pair of amendment and different lowercase letters across the column represent a significant difference at p < 0.05 between before and after pyrolysis, and among all the treatments, respectively(One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test).

Also in Table 5 are the data of PTEs concentration in the aboveground pak choi. Firstly, plant Pb was all unchanged (p < 0.05) with the amendments. Compared to CK, plant Cd was unchanged (p > 0.05) under UWS and USM but significantly (p < 0.05) reduced by 40–60% under WSB and SMB although increased (p < 0.01) by folds under USS and SSB. Whereas, compared to control, the Cu content was unchanged (p > 0.05) under WS but increased (p < 0.05) by over 25% under SM and SS, generally regardless of pyrolysis. In contrast, the Zn content was greatly (p < 0.01) increased under USM, USS and SMB by folds but significantly (p < 0.05) reduced by over 40% under UWS and WSB. As shown in Table S5, BCF values were lower (p < 0.05) under biochar amendments compared to their unpyrolyzed counterparts except Pb unchanged (p > 0.05). Furthermore, total uptake of the PTEs by the aboveground pak choi estimated with biomass yield and plant concentration was significantly (p < 0.05) lower under USS than under SSB, under USM than under SMB though similar (p > 0.05) between UWS and WSB (Table S5).

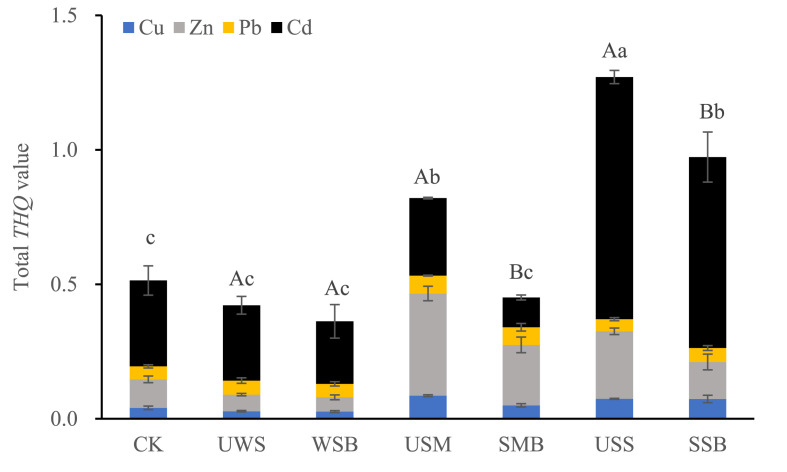

The target hazard quotients (THQ) of the PTEs in pak choi estimated for adults is plotted in Fig. 7 , assuming the pak choi grown under the treatments for vegetable daily consumption. While the individual THQ values of Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd were all under 1 across the amendments, total THQ was as small as 0.35 under WSB but as high as 1.27 under USS. Nevertheless, a total THQ value was significantly (p < 0.05) lower under a biowaste pyrolyzed than unpyrolyzed. For example, total THQ was 0.82 under USM and 1.27 under USS, compared to 0.45 under SMB and 0.97 under SSB respectively.

Fig. 7.

Total THQ values of potentially toxic metals by adding up the individual values of Cu (blue), Zn (gray), Pb (yellow) and Cd (black) in the pak choi via diet consumption by adult. CK, control; UWS and WSB, USM and SMB, and USS and SSB, wheat residue, swine manure and sewage sludge respectively before and after pyrolysis. Different uppercase letters above the bars in a single pair of amendment and different lowercase letters above all the bars, represents a significant difference at p < 0.05(One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey test) between before and after pyrolysis, and among all the treatments, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussions

4.1. Mobility and availability of PTEs greatly reduced in pyrolyzed biowastes

In this study, pyrolysis conversion of the biowastes generally led to increase in total contents of PTEs in the biochars (Table 2), which appeared more or less beyond the guideline thresholds (1000, 2500, 750 and 20 mg kg−1 respectively for Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd) for sewage sludge established by EU legislation (Fuentes et al., 2004). Fortunately, the almost complete removal (over 97%) of CaCl2 portion for Cu and Zn, the great reduction of this portion by 74–86% for Pb and by 21–75% for Cd confirmed a great immobilization of PTEs in the biochars after the biowastes pyrolyzed. Conversion of biowastes into biochar could be effective in heavy metal immobilization, thereby reducing their bioavailability (Cantrell et al., 2012; Park et al., 2011). As addressed by Bian et al. (2018), Cu, Zn and Pb were highly accumulated in the biochar products after pyrolysis though total Cd declined in SSB, relative to before pyrolysis (Table 2). This was resulted from thermal decomposition of organic tissues in the feedstock containing metals and volatilization of carbon molecules during pyrolysis at high temperature (Kistler et al., 1987), particularly when sewage sludge pyrolyzed (He et al., 2010). In this study, there were no significant (p < 0.05) correlations of extractable and leachable pool to total contents of the studied PTEs, for their divergent variation with the different biowaste types. In terms of the pool portion to total burden, chemical mobility with CaCl2 extraction and leaching potential with TCLP of the PTES in the biowates, including swine manure and sewage sludge, were shown mostly largely or even completely reduced following pyrolysis (Table 2, Section 3.1). Although leaching potential of Cd was unexpectedly increased in pyrolyzed sewage sludge, the study could confirm a general but sharp deactivation of available or leachable PTEs present in the biowaste through pyrolysis at temperatures over 400–500 °C in engineered production system (He et al., 2010; Bian et al., 2018).

Such deactivation of PTEs in the pyrolyzed biowastes could be further evidenced with the BCR fractionation analysis (Fig. 3; Table S2). Thereby, lower proportion of F1 but higher proportion of F3 and F4 in the biochars referred to stabilization into stable OM- and mineral-bound forms of the PTEs (He et al., 2010; Cui et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2018), existed originally as soluble salts in SM and SS before pyrolysis. Across the PTEs, the proportion of exchangeable pool decreased while OM (and/or sulfides) -bound fraction increased in the biochars after pyrolysis of the biowastes (Fig. 3). This seemed in agreement with the finding by Zeng et al. (2018) that following pyrolysis, metals became increasingly associated with or bound to stable OM and by Wang et al. (2016) that pyrolysis enhanced transformation of the mobile and easily available PTEs into relatively stable forms. As already clearly known, organic matter exerted a pivotal role in controlling metal mobility (Sauve et al., 2000) in epigenic environment. For Pb however, reducible fraction was relatively increased while mineral bound fraction decreased after pyrolysis for its prompt susceptibility to be bound with amorphous minerals of (oxy) hydrates (Janssen et al., 1997). The other PTEs were largely immobilized after pyrolysis as OM bound F3 fraction and mineral bound F4 fraction, with a net 17% increase relative to before pyrolysis (Table S2; Fig. 3). Particularly, Cu and Zn in swine manure and sewage sludge were present largely as soluble salts (Zeng et al., 2018) but in the biochars became co-precipitated into minerals, partly with phosphorus (Bashir et al., 2018) and other mineral components following reaction with functional groups on the particle surfaces (Bian et al., 2014). This was supported in part with the EDS spectra showing more mineral element peaks (Ti, Mg, Al etc) in the biochars (Fig. S1). Following pyrolysis, heavy metals more or less in soluble salts in the biowastes became increasingly bound to insoluble minerals with thermal stability including sulfides, and (hydrooxy)oxides and complicate phosphates during pyrolysis at high temperature (Inyang et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Overall, the PTEs in the biowaste were effectively deactivated in the pyrolzyed biochars through significant shift in chemical forms with which the metals were originally associated.

With the changes in extractability and in chemical fractionation, potential mobility as per leaching test was seen concurrently reduced and thus environmental risks of the PTEs greatly lowered. For all the materials (Fig. S2), an environmental risk as per the RAC value was mainly contributed by Zn and Cu with small contribution by Pb and Cd. Following pyrolysis, the environmental risk by individual PTEs was reduced by 1–2 folds (except for Zn in SMB by 30% and Cd in SSB unchanged), with an overall medium risk in the biowastes to an overall low risk in the biochars. Of course, these smaller effects for Zn and Cd was similarly reported by Zeng et al. (2018) and Wang et al. (2016) respectively treating sewage sludge and swine manure with pyrolysis. Generally, solid-solution partitioning of metals in environment conditions was mainly controlled by the total burden, OC and pH of the material (Janssen et al., 1997; Sauve et al., 2000; Pan et al., 2017). While N and P were seriously considered with migration potential across soil-water system for environment risk (Bouwman et al., 2013), dependence of TCLP mobility of Cu and Zn on total N or P in the materials was noted, both becoming significantly (p < 0.05) weaker after pyrolysis of the biowastes (Fig. S3). Of course, the high contents of Cu and Zn were already beyond the potential sorption of all these metals in the biochar, but the biochars in high pH, pore structure and high surface area could help immobilize these heavy metals from release into solution (He et al., 2010; Agrafioti et al., 2013; Ahmad et al., 2014). With the changes in fraction/speciation and further in surface reactivity (Fig. 2) related to pH, porosity, and surface area and functional groups (Joseph et al., 2013; Bian et al., 2016), pyrolysis greatly reduced the mobility of the PTEs in the biowastes (Park et al., 2011; Bian et al., 2018) and could thus minimize their potential release into water and in turn translocation through soil-root and plant-food system, as observed by Fagnano et al. (2011) and by Gu and Bai (2018).

Consequently, availability and plant uptake of the PTEs were significantly reduced in pot soil amended with the biochars compared to unpyrolyzed biowastes. Application at a 2% dose led to a general increase in soil total concentration of the PTEs with the swine manure and sewage sludge after pyrolysis compared to before pyrolysis (Table 4), with the total Cu and Cd under sewage sludge biochar approaching the recently upgraded Chinese standard (MEEC, 2018). Use of quality compost from sewage sludge could even elevate soil availability of PTEs though soil total content almost unchanged (Fagnano et al., 2011). Hereby, under biochar over the relevant unpyrolyzed biowaste, PTEs availability as the portion by CaCl2 extractable pool to the total was found significantly (p < 0.05) reduced, so was often the pool itself (Table 4), in the pot soil originally low in pH and SOC. This was particularly important for Cu and Zn in swine manure, and Cd in sewage sludge originally highly toxic (Guo et al., 2018). As a result, plant concentration (Table 6) and bio-accumulation (Table S5) of Cu, Zn and Cd were significantly (p < 0.05) lower with pyrolzyed swine manure and sewage sludge than the unpyrolyzed ones. There was a very significant (p < 0.01) but strong correlation (Fig. S4) of plant concentration to soil available pool for Zn (r2 = 0.97, n = 7) and Cd (r2 = 0.89, n = 7) though not valid (p > 0.05) for Cu and Pb (data not shown). This highlighted a strong link of reduced plant accumulation (bioavailability) to the reduced availability in amended soil with the biochars even high in total metal burden. Such soil immobilization could be induced via promoted binding of PTEs to biochar surfaces rich in organic functional groups in line with elevated soil pH (Uchimiya et al., 2011; Bian et al., 2014), provided with the amended biochars higher in pH and porosity (Table 1, Fig. 2). However, the extent by which soil available pool and plant accumulation of Zn and Cd were reduced under the biochars was similar between SMB amended and SSB amended soils. This was not coincident with their difference in surface area, pH and ash content of the biochar between SMB and SSB (Table 1; Fig. S1). The high ash content together with the largely reduced EC of sewage sludge after pyrolysis could suggest a potential metal adsorption to and co-precipitation into ash minerals (Ahmad et al., 2014) and/or potential further sequestration into biochar pores (Bian et al., 2014) in SSB, thus minimizing metal release and plant uptake.

4.2. Microbial and ARGs abundance minimized in pyrolyzed biowastes

In this study, pyrolysis almost completely (>99.99%) removed the microbes in swine manure and sewage sludge originally in high abundance (Fig. 4). This, of course, was caused by the direct sterilization with high temperature pyrolysis (Lehmann and Joseph, 2015). Resultantly, all the biochars (and USS high in Cd) unchanged microbial abundance of the amended soil (Fig. 5 a,b). Of course, the significant increase compared to CK in bacterial and fungal abundance under UWS and USM could be attributed to a sharp microbial response to addition of fresh organic matter with nutrients (Table 1). Whereas, the relatively lower microbial abundance under WSB than UWS and under SMB than USM could be explained with the addition (Table 1) of relatively recalcitrant OM high in C/N ratio (Cayuela et al., 2014). In addition, no significant change in microbial abundance under amendment of sewage sludge regardless of pyrolysis could be related to their high metal toxicity particularly of Cd (Bååth, 1989) for microbes in soil (Giller et al., 1998; Marschner et al., 2003). This tended not coincident with the general promotion of microbial growth (Zhou et al., 2017) or with the recovery of microbial biomass and activity in metal contaminated soil (Zhou et al., 2018), under biochar amendment. In the amended soils, moreover, gene abundance ratio of bacterial to fungi (B/F ratio) was seen higher under the biochars compared to unpyrolyzed bio-wastes and to the control, for biochar could shift soil microbial community and activity towards bacterial domination (Gul et al., 2015). Biochar amendment tended to increase gene abundance likely of bacterial but unlikely of fungi (Chen et al., 2015). Thus, pyrolyzed biowastes did not affect overall microbial abundance but increased bacterial prevalence in the amended soil.

Furthermore, pyrolysis effectively eliminated the ARGs existed in the biowastes, with sul1 even undetected in SMB and SSB and other ARGs eliminated by an order of 102 to 105 though by one order for tetW in SSB (Table S3). When amended at 2%, abundance of total ARGs in pot soil was at the background level of CK under all the biowaste materials other than under USM, in which total abundance of ARGs was increased by 10-fold over CK (Fig. 4c). Also, the total ARGs abundance in amended pot soil tended lower under the biochars than their unpyrolyzed counterparts. As generally carried on Gram-negative bacteria (Wellington et al., 2013), the ARGs in the biowastes, particularly in swine manure with highly concentrated ARGs (Fig. 4), were eliminated through the direct sterilization during high temperature pyrolysis under limited oxygen (Lehmann and Joseph, 2015). Among the individual ARGs, intI1 could represent genes resistant to a variety of antibiotics (Partridge et al., 2009) and thus concerned for environment risk with potential soil-water migration (Zhu et al., 2013). Kimbell et al. (2018) observed an effective removal of intI1 gene along with other ARGs in municipal waste-water biosolids following pyrolysis at temperatures between 300 and 700 °C. In this study, the gene abundance of intI1 was lowered in the SMB by an order of 102 and in SSB by an order of 104 over the unpyrolyzed counterparts (Table S3). Further in the amended soil, the abundance of this gene was reduced by 80% and 40% in SMB and SSB respectively over USM and USS, though already close to the background level in the control.

Manure had been considered as a major source of ARGs migration in environment (Zhu et al., 2013), often in association with bacterial communities (Chen et al., 2018; Su et al., 2015). Increasing studies had shown soil accumulation of ARGs in agricultural soils due to direct addition of untreated animal manure (Agerso and Sandvang, 2005; Zhu et al., 2013) or sewage sludge (Chen et al., 2016). Hereby, the reduction to the background level under SMB was evidently greater than the relative decline in abundance of ARGs and intI1 reported by Zhou et al. (2019) in a similar study with pyrolyzed manure than manure compost. An elimination and thus minimization of soil spread of ARGs along with inherent microbes from biowastes particularly of swine manure, was achieved with high temperature pyrolysis for agricultural application.

4.3. Soil quality, plant growth and safety improved with pyrolyzed biowastes

Compared to the unpyrolyzed biowaste, pak choi biomass production in the amended pot soil was higher by folds with SMB and SSB but unchanged with WSB (Table 5). Over control, pak choi biomass yield greatly (p < 0.01) declined (by almost 60%) under USM and USS, probably owing to the constraints by high salinity (high EC, Table 1) and high availability and mobility of PTEs (Shao et al., 2019), particularly of Zn and Cd. Following pyrolysis, Zn in swine manure and salt in sewage sludge were largely immobilized (Table 2), plant growth in the biochar added soil was further promoted with the improvement of soil nutrients and reaction (compared to original soil pH 4.99). High yield of pak choi under SMB could be also related to the high P and N level in the amended soil (Table 3), which had been often reported for pak choi with manure biochar (Khan et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2012). Whereas, insignificant (p > 0.05) yield increase under SSB over CK was similar to the finding for spinach by Yachigo and Sato (2013), possibly due to the remarkable Cd mobility still found in the amended soil (Table 4). This could be true also for that the yield change between USW and SWB, and between USS and SSB was relevant to difference in RAC (mobility) values of Cu and Zn between them (Fig. S2). Toxicity of Cu and Zn for vegetables were often reported in manure and sewage sludge applied soils (Påhlsson, 1989; Tandi et al., 2004). While variable changes with biochar in biomass production had been noted (Liu et al., 2013), this study confirmed that pyrolyzed sewage sludge maintained but pyrolyzed swine manure promoted vegetable production, as a recycling solution for the biowastes with concentration of total PTEs.

As for the pak choi nutrition quality, the contents of individual nutrition components were not changed markedly with the amendment treatments including nitrate content, which was high but below the guideline limit of 2500 mg kg−1 (EC, 2006). Vc content, however, was greatly higher (by >80%) under pyrolyzed than under unpyrolyzed swine manure and sewage sludge, in corresponding to the yield change mentioned above. In a pot experiment, Liu et al. (2018) reported a >70% increase in Vc content of pak choi under wheat biochar compared to no biochar, either in high or in low fertility soils. Hereby, the increase over CK in Vc content was 12% under WSB and SSB but >70% under SMB. Over unpyrolyzed, comparatively, pyrolysis caused a >80% increase in pak choi Vc content following application of the swine manure and sewage sludge. Though serious potential environment risks concerned for these biowastes, pyrolysis of them shifted their quality effect with a parallel improvement of biomass production.

Furthermore, estimated overall nutrition quality of pak choi was improved significantly (p < 0.05) under SMB and SSB but insignificantly (p > 0.05) under WSB, compared to their unpyrolyzed counterpart (Table S6). Notably, a very significant (p < 0.01) correlation (Fig. S5) between biomass yield and nutrition quality index of pak choi grown in the amended soils indicated a synergic effect by the pyrolyzed biowastes on vegetable production. This could be of particular significance in farming management practices to ensure food safety, in terms both of food quantity and quality, in agriculture seriously challenged by global environmental change (Tirado et al., 2010). Although swine manure and sewage sludge unpyrolyzed could lead to yield and quality decline, amendment of them after pyrolysis indeed sustained biomass production and even improved nutrition quality in the acid OC-poor soil.

Furthermore, changes in plant concentration of PTEs of pak choi grown in the amended soil could further evidence the plant health improvement with biowaste pyrolysis. Despite of a general negative linear correlation of plant Cu, Zn and Cd except for Pb respectively to plant biomass, concentration of Cu, Zn and Cd was more or less reduced under the biochars compared to the unpyrolyzed biowastes (Table 5), being not ascribed for yield change (Fig. 6). Pak choi was a leafy crop with high affinity for Zn and Cd, its plant concentration and total uptake of Cd and Zn as well as Cu was significantly (p < 0.05) but positively correlated to the soil CaCl2 extractable pool (Fig. S4). Like in the work by Chen et al. (2018), values of BCF as a plant accumulation factor (Table S5) was significantly (p < 0.05) lowered in pot soil amended with a biowaste biochar. Thus, pyrolysis of the biowastes, particularly of swine manure and sewage sludge, could play a soil-plant system barrier for PTEs plant uptake and accumulation (Basta et al., 2005) through the alleviated “salt effect” (CF: EC of the bio-wastes before and after pyrolysis, Table 2), elevated pH as well as enhancement of stable OC as organic binders (Table 3) (Bian et al., 2014). Taking into account of PTEs content as a negative component of plant quality, the estimated overall plant quality was again observed to greatly improved under pyrolyzed swine manure and sewage sludge compared to unpyrolyzed (see Fig. 6). As swine manure and sewage sludge often caused yield decline and metal accumulation in vegetables (Berti and Jacobs, 1996; Bolan et al., 2004), pyrolysis of them could provide a synergetic improvement of crop production and overall quality (Fig. S5 a,b), minimizing PTE accumulation in produced food in amended soil.

More interestingly, soil quality improvement with carbon increase was prominent in this study. With the microbial abundance preserved or even enhanced, soil reaction and SOC storage in the acid OC poor soil was much improved together with nutrient enrichment of N, P and K, following amendment of the biowaste biochars (Table 3). Following one season of pak choi production, SOC loss was much smaller under the biochars than under the unpyrlyzed biowastes. Likewise, there were higher increases in soil P and K storage under pyrolyzed than unpyrolyzed biowastes. It should be noted that pak choi biomass production was very well (p < 0.01) correlated to soil organic carbon (Fig. S5c). This could add value to soil organic carbon sequestration, concerned mainly for climate change mitigation (Rumpel et al., 2018). The higher storage of available P and K through the amendment input (Table 1, Table 3), as potential contributor of biochar-assisted soil fertility improvement (Jeffery et al., 2011), could indicate better circularity of nutrients. As these were originally provided with agrochemical input in primary crop production, using pyrolyzed biowastes could potentially contribute to a more sustainable world in the context of bioeconomy (Zilberman et al., 2018) or circular economy (Korhonen et al., 2018).

In addition, soil CaCl2 extracted pool for all PTEs analyzed was significantly smaller and thus the availability greatly lower under biochar than under pyrolyzed biowastes (Table 4). Enhancement of SOC and soil available nutrient pool together with declined metal availability could likely bring about improvement of soil fertility quality (Table 3). This could benefit not only plant growth for less metal uptake mentioned above but also for nutrient efficiency improvement. The agronomic use efficiency of applied urea and total N input were both increased by 2–3 folds under SMB and SSB though unchanged under WSB compared to the biowaste before pyrolysis. A very significant (p < 0.01) correlation of overall quality index between of soil and of plant (Fig. S6) supported a concurrent improvement of soil-plant system under the biochars than their unpyrolyzed biowastes. Reasonably, use of the pyrolyzed biowaste as a potential tool to increase soil carbon while to improve soil-plant health, as demanded recently by the “C 4 per mille” initiative (Rumpel et al., 2018).