Abstract

Algal seaweeds have abundant amounts of active substances and can be used as pharmaceuticals and biomedicals in aquafeeds. In this context, the powder of red macroalgae Gracilaria persica was included in the diets of Persian sturgeon at the rate of 0, 2.5, 5, and 10 g/kg to investigate its role on the growth rate, fillet colouration, haemato-biochemical indices, serum, and skin mucus immunity. The weight gain, SGR, and FCR displayed no significant changes in fish fed varying levels of G. persica (P > 0.05). The level of total carotenoids was significantly higher in the blood and fillet of fish fed 5 and 10 g G. persica/kg diet (P < 0.05). Dietary G. persica significantly altered RBCs, WBCs, and HCT at 5, and 10 g/kg, whereas the Hb was increased in fish fed 5 g/kg (P < 0.05). The blood total protein and albumin were significantly increased in fish fed 5 and 10 g/kg (P < 0.05). No significant alterations were observed on ALT, AST, ALP, and glucose levels of fish fed varying levels of G. persica (P > 0.05). Serum Ig, lysozyme, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and respiratory burst activities were increased in fish fed 5, and 10 g/kg than fish fed 0 and 2.5 g/kg diet (P < 0.05). The level of total protein and lysozyme activity in the skin mucus were significantly higher in the blood and fillet of fish fed 5, and 10 g G. persica/kg diet than fish fed 0 and 2.5 g/kg (P < 0.05). Based on the obtained results, G. persica can be used as a feasible feed additive in the diets of Persian sturgeon at 5–10 g/kg diet.

Keywords: Gracilaria persica, Persian sturgeon, Immunity, Coloration, Growth

Highlights

-

•

Persian sturgeon showed enhancement of fillet coloration after fed G. persica addition at 5–10 mg/kg diets.

-

•

Dietary G. persica improved the haemato-biochemical indices of Persian sturgeon.

-

•

Persian sturgeon fed G. persica enriched diets showed enhancement of serum immunity.

-

•

G. persica -supplemented diets enhanced the skin mucus immunity of Persian sturgeon.

1. Introduction

The new world challenges, including COVID-19, obligates researchers to ensure the production of the healthy and secure food chain. The aquaculture sector is growing to support the increasing population with a nutritious and cheap animal protein source (Magouz et al., 2020). Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus) originally exist in the southern division of the Caspian Sea and has a high demand due to its pleasant flavours (Aramli et al., 2015). In the modern aquaculture systems, fish suffering from stressful environmental conditions that adversely affect the fish's immune system and increases its susceptibility to infectious agents (Adel et al., 2020; Dawood et al., 2020b). Fish farmers frequently use a broad range of antibiotics and chemotherapeutics to combat these pathogens; however, it leads to the spread of resistant strains and environmental threats, posing a significant problem in aquaculture (Dawood, 2020; Sutili et al., 2018). Correspondingly, the vision of using alternative friendly approaches to replace antibiotics is of interest to guarantee health and sustainable aquaculture sector (Abdel-Latif et al., 2020; Dawood et al., 2018).

Seaweeds have been increasingly applied in seeking new drugs as a primary source of bioactive natural compounds and biomaterials (Ashour et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2018). The red macroalgae Gracilaria gracilis has a potential role as pharmaceutical and biomedical additives, which associated with its abundant amounts of vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, proteins, phycobiliproteins, and carbohydrates as well as phenolic content, antioxidants, and radical scavenging substances (Francavilla et al., 2013). In this sense, when the powder of G. gracilis was included in zebrafish diets, the results displayed enhanced antioxidative capacity, humoral immunity, and skin mucus immunity (Hoseinifar et al., 2018). In the same line, Gracilaria sp. showed positive impacts on the growth rate, digestive enzyme activity, immunity, antioxidative capacity, and stress resistance in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) (Peixoto et al., 2016), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Araújo et al., 2016), black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) (Xuan et al., 2013), Siganus canaliculatus (Xu et al., 2011), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) (Younis et al., 2018), barramundi (Lates calcarifer) (Morshedi et al., 2018), and yellow cichlid (Labidochromis caeruleus) (Pezeshk et al., 2019).

No detailed research work is available on dietary G. gracilis effects on the performances of Persian sturgeon. Hence, the present research was first attempted to test diet containing G. gracilis on the growth rate, feed efficiency, haemato-biochemical indices, and innate-adaptive immunity in Persian sturgeon.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental fish

Healthy Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus) (n = 400) with the mean weight of 18.1 ± 0.9 g were obtained from a commercial fish farm at Gilan province, Iran. They were aseptically transported to Ahmadabad-e Mostofi farm (Tehran province, Iran) and acclimatized for two weeks in fiber glass tanks (5000 L). Fishes were fed with basal diets for two weeks (Table 1 ). Then, fish were distributed randomly into 12 fibreglass tanks (4 groups), each with 30 fish before fed with four prepared diets for eight weeks. The water quality was monitored daily at the temperature of 18.2 ± 1.0 °C, dissolved oxygen of 6.8 ± 0.2 mg/l, pH of 7.8 ± 0.21, ammonia of 0.02 ± 0.01 mg/l and electrical conductivity of 5836.2 ± 414.3 MM/cm. The photoperiod was maintained of 14 h light and 10 h dark cycle.

Table 1.

Dietary formulation and proximate composition of basal diet.

| Ingredient | Composition (g/kg) | Proximate composition | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kilka fish meal | 445 | Crude protein | 40.1 |

| Wheat flour | 221.5 | Crude lipid | 15.3 |

| Wheat gluten | 60 | Ash | 18.2 |

| Starch corn | 50 | Fiber | 2.7 |

| Soybean oil | 100 | Moisture | 8.1 |

| Fish oil | 80 | NFEe | 18.1 |

| Mineral premixa | 10 | Gross energy (MJ/kg)f | 21.3 |

| Vitamin premixa | 15 | ||

| Cellulose | 10 | ||

| Binderb | 2 | ||

| Antifungic | 3 | ||

| Antioxidantd | 3.5 |

Premix detailed by Adel et al. (2020).

AmetbinderTM, MehrTaban-e-Yazd, Iran.

ToxiBan antifungal (Vet-A-Mix, Shenan- doah, IA).

Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) (Merck, Germany).

Nitrogen-free extracts (NFE) = dry matter - (crude protein + crude lipid + ash + fiber).

Gross energy (MJ/kg) calculated according to 23.6 kJ/g for protein, 39.5 kJ/g for lipid and 17.0 kJ/g for NFE.

2.2. Preparations of Gracilaria persica powder and experimental diets

The red macroalgae, G. persica, were collected from the Oman Sea, the coast of Chabahar, Iran. G. persica were rinsed with tap water and washed three times with distilled water to remove extraneous materials. Then, the biomass was sun-dried for two weeks (Jafari et al., 2020) and then finely ground through 60 mesh. Proximate composition of G. persica including crude protein of 34.8 ± 0.2 (% d.w.), crude lipid of 8.3 ± 0.1 (% d.w.), ash of 26.1 ± 0.4 (% d.w.), crud fiber of 7.1 ± 0.08 (% d.w.) and carotenoid of 0.82 ± 0.06 (mg/g). Components of the basal diet (Table 1) were mixed with the obtained G. persica powder in an appropriate concentration (Mohseni et al., 2007), to get four different experimental diets with 0 (control), 2.5, 5, 10 g/kg of G. persica powder (Hoseinifar et al., 2020). The diets were made into pellets, allowed to dry, and stored at 4 °C until use. During this experimental period, fish groups were fed three times a day at 3–4% of body weight for eight weeks. The water quality was maintained throughout the experimental period, and partial water exchange was done daily to remove waste feed and fecal materials.

2.3. Growth performance

All fish in each tank were deprived of food for 24 h before weighing and sampling, and the following parameters were measured at the end of feeding trial after eight weeks.

Weight gain = W2 (g) – W1 (g).

Specific growth rate (SGR) = 100 (ln W2 – ln W1)/T.

Feed conversion ratio (FCR) = feed intake (g)/weight gain (g).

Survival rate (%SR) = (final amount of fish/initial amount of fish) × 100.

Where W1 is the initial weight, W2 is the final weight and T is the number of days in the feeding period.

2.4. Blood sampling and hematological analysis

At the end of the feeding trial, 3 fishes were selected from each tank and anesthetized with clove oil (75 mg/l) (Darafsh et al., 2020). Blood samples (2 ml) were collected from the caudal vein of individual fish and immediately divided into two half parts. One half was transferred to a tube containing an anticoagulant (heparin) for studying the respiratory burst assay and make the hematological analysis, while the other half was assigned to non-heparinized tubes for biochemical and immunological studies. Sera samples were obtained by blood centrifugation (3000 × g, 10 min) and stored at −80 °C until use.

The total red blood cells (RBC: 106/mm3) and white blood cells (WBC: 103/mm3) were enumerated in an improved Neubauer hemocytometer using Hayem and Turck diluting fluids (Blaxhall and Daisley, 1973). Hematocrit (Ht %) was determined by the standard microhematocrit method and expressed as a percentage. The haemoglobin (Hb, g/dl) level was determined according to cyanomethemoglobin procedure. Furthermore, differential leukocyte cells were measured by preparing Giemsa stained smears. Blood smears were studied by light microscopy to make blood cell counts.

2.5. Biochemical analysis and antioxidative status

Glucose, albumin, total protein (TP) level, and enzymatic activities of liver including; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were estimated on fish sera by using commercial kits (Pars Azmoon Company, Tehran, Iran) and a biochemical auto analyzer (Eurolyser, Belgium).

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in serum samples was estimated using the Nitro blue tetrazolium chloride dye reduction test (NBT) (Mohebbi et al., 2012). Briefly, 100 μL aliquots of serum were added to 2 mL of reaction mixture (containing 0.20 mM xanthine, 0.12 mM NBT, 0.049 IU xanthine oxidase (Sigma Company, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. Then, the absorbance was read at 560 nm. SOD activity was expressed as the percentage inhibition of reduction of NBT.

The serum catalase (CAT) activity was determined according to the method described by Mohebbi et al. (2012). Briefly, 100 μL of serum was incubated for 1 min with 1 mL reaction mixture consisting of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 10.6 mM H2O2 (Merck, Germany) freshly prepared at 37 °C. The reaction was terminated by adding 0.5 mL of 32.4 mM ammonium molybdate solution (Merck, Germany). A yellow complex of ammonium molybdate and hydrogen peroxide was created. The absorbance of the complex was measured at 405 nm with a spectrophotometer and compared with a blank (distilled water). One unit of CAT activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyses the decomposition of 1 μmol of H2O2 per minute.

2.6. Blood and fillet carotenoid concentration

The blood carotenoid concentration was measured according to the assay described by Barbosa et al. (1999). Briefly, 200 μl of serum sample was mixed with 400 μl of ethanol (95%) and 1 ml of hexane. The mixture was vortexed for 1 min, and hexane was collected following centrifugation at 4500 rpm for 10 min. The carotenoid absorption was read using Tean F-200 multiwell plate reader (Tecan Mannedorf; Zurich, Switzerland) at 450 nm in n-hexane. Carotenoid concentration was calculated using a specific extinction coefficient (E1%, 1 cm) 2500 in n-hexane (Weber, 1988). Approximately 25 g of fish fillet of each Persian sturgeon (n = 5) were collected and stored in the freezer (−80 °C). The carotenoid content was extracted according to the method described by Teimouri et al. (2013). The carotenoid concentration of fillet was determined spectrophotometrically in acetone using extinction coefficients (E1%, 1 cm) 2500 for carotenoids at 450 nm.

2.7. Immunological parameters

Serum immunoglobulin (Ig) level was quantified by microprotein determination method (C-690; Sigma). Precipitation was carried out by 12% polyethylene glycol solution, and the difference in protein content before and after precipitation was considered as the Ig level (Siwicki and Anderson, 2000). The lysozyme activity in serum was determined using the method described by Ellis (1990) with more modifications. Briefly, 50 μl of sera were added to 2 ml of a suspension of Micrococcus lysodeikticus (0.2 mg/ml in a 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.2) and absorbance was measured at 450 nm after 0.5 min and 3 min by spectrophotometer (Biophotometer, Eppendorf). Respiratory burst activity of blood leukocytes was measured by chemiluminescent assay (LUMI Skan Ascent T392, Finland) employing the strategy of Binaii et al. (2014). Finally, the alternative complement activity (ACH50) was determined by methods described by Yano (1992) by using 50% hemolysis of the rabbit red blood cells (RaRBC).

2.8. Collection of mucus

The mucus samples were scraped from the anterior to posterior direction on dorsal body surface from 3 fish per tank using a sterile spatula following the method described by Balasubramanian et al. (2013). The collected mucus was thoroughly mixed with equal quantity of sterilized Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) and centrifuged at 30,000 ×g at 4 °C for 15 min (Beckman coulter, Avanti J-26 XPI, Brea, CA, USA). The supernatant was then collected and filtered with Whatman no.1 filter paper. The filtrate was then collected and kept frozen at −80 °C to avoid bacterial growth and degradation until used.

The skin mucus protein levels (mg/ml), total immunoglobulin, and lysozyme activity.

The total protein concentration of mucus was measured according to the method that was described by Lowry et al. (1951). Total immunoglobulin (Ig) level was determined according to the method described by Siwicki and Anderson (2000) by using a micro protein determination method (C-690; Sigma). The activity of mucus lysozyme was measured similarly to the protocol used for serum lysozyme activity as described above.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to statistical analysis using the SPSS software version no. 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical analysis was done by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's multiple range tests. P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All the tests were performed in triplicate.

3. Results

3.1. Growth performance and carotenoid content

The weight gain, SGR, and FCR of Persian sturgeon fed varying levels of G. persica displayed no significant changes among the fish (P > 0.05) (Table 2 ). The survival rate of fish during the trial is 100% without mortality in all groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Growth performance of Persian sturgeon fed with diets supplemented with different levels of Gracilaria persica powder (g/kg) for 8 weeks.

| Index | Control | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial weight (g) | 18.02 ± 0.05 | 18.12 ± 0.04 | 18.06 ± 0.07 | 18.11 ± 0.08 |

| Final weight (g) | 41.52 ± 0.62 | 40.82 ± 0.39 | 41.36 ± 0.8 | 40.91 ± 0.9 |

| WG (g) | 23.5 ± 0.8 | 22.7 ± 0.5 | 23.3 ± 0.4 | 22.8 ± 0.7 |

| SGR (%/day) | 1.54 ± 0.06 | 1.46 ± 0.03 | 1.51 ± 0.05 | 1.45 ± 0.03 |

| FCR | 1.46 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 1.49 ± 0.02 | 1.55 ± 0.03 |

| SR (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. Data in the same row without superscript are not significantly different (P > 0.05). WG, weight gain; SGR, specific growth rate; FCR, fed conversion ratio; SR, Survival rate.

The level of total carotenoids was significantly higher in the blood and fillet of fish fed 5, and 10 g G. persica/kg diet than fish fed 0 and 2.5 g/kg (P < 0.05) (Table 3 ). Additionally, fish fed 10 g/kg had higher total blood carotenoids than fish fed 5 g/kg (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Total carotenoids levels in blood and fillet of Acipenser persicus fed with diets supplemented with different levels of Gracilaria persica powder (g/kg) for 8 weeks.

| Index | Control | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total carotenoids levels in blood (μg/g) | 11.3 ± 1.04c | 12.62 ± 0.92c | 15.83 ± 1.1b | 17.62 ± 1.2a |

| Total carotenoids levels in fillet (μg/g) | 0.69 ± 0.01b | 0.75 ± 0.01b | 0.83 ± 0.02a | 0.89 ± 0.01a |

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 5). Data in the same row with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

3.2. Haemato-biochemical indices

Dietary G. persica significantly altered RBCs, WBCs, and HCT at 5, and 10 g/kg whereas the Hb was increased in fish fed 5 g/kg (P < 0.05) (Table 4 ). No significant differences were reported between fish fed 5 and 10 g/kg in terms of Hb and fish fed 2.5, 5, and 10 g/kg in terms of WBCs (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Hematological indices of Acipenser persicus fed diets enriched with different levels (g/kg) of Gracilaria persica powder for 8 weeks.

| Parameter | Control | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC (106/ mm3) | 0.89 ± 0.03b | 0.92 ± 0.04b | 1.09 ± 0.05a | 1.12 ± 0.06a |

| WBC (103/ mm3) | 7.5 ± 0.1b | 7.9 ± 0.08 ab | 8.5 ± 0.09a | 8.7 ± 0.08a |

| HCT (%) | 25.9 ± 0.9b | 26.7 ± 0.5b | 28.2 ± 0.6a | 29.1 ± 0.6a |

| Hb (g/dL) | 8.72 ± 1.17b | 9.02 ± 1.10b | 9.42 ± 1.0ab | 9.61 ± 0.87a |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 77.3 ± 1.5 | 77.34 ± 1.1 | 77.6 ± 1.2 | 75.0 ± 1.5 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 16.77 ± 0.7 | 17.1 ± 0.5 | 17.8 ± 1.0 | 18.1 ± 0.7 |

| Monocyte (%) | 5.11 ± 0.18 | 5.62 ± 0.11 | 5.98 ± 0.15 | 6.14 ± 0.19 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 0.76 ± 0.02 |

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 9). Data in the same row with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05). RBC, red blood cells; WBC, white blood cells; HCT, hematocrit; Hb, haemoglobin concentration.

The blood total protein was significantly increased in fish fed 5 and 10 g/kg, when compared with fish, provided the control diet without significant differences with fish fed 2.5 g/kg diet (P < 0.05) (Table 5 ). Albumin level was increased in fish provided 5, and 10 g/kg than fish fed 0 and 2.5 g/kg diet (P < 0.05) (Table 5). Further, fish fed 10 g G. persica/kg had higher albumin level than fish fed 5 g G. persica/kg. Fish fed 10 g G. persica/kg had higher globulin level than fish fed the other diets (Table 5).

Table 5.

Biochemical parameters of Acipenser persicus after feeding with different levels of Gracilaria persica powder incorporated diet (g/kg).

| Parameter | Control | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP (IU/dl) | 363.1 ± 17.3 | 368.3 ± 18.2 | 351.6 ± 17.0 | 345.2 ± 15.4 |

| AST (IU/dl) | 245.6 ± 10.8 | 232.8 ± 11.6 | 229.0 ± 10.9 | 231.8 ± 7.5 |

| ALT (IU/dl) | 13.2 ± 1.1 | 13.2 ± 1.0 | 12.7 ± 1.1 | 12.8 ± 0.8 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 75.4 ± 2.1 | 76.3 ± 3.3 | 77.2 ± 2.9 | 76.8 ± 2.4 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 0.87 ± 0.05b | 0.91 ± 0.08b | 1.14 ± 0.06ab | 1.51 ± 0.1a |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 0.50 ± 0.03c | 0.55 ± 0.06c | 0.77 ± 0.04b | 1.10 ± 0.05a |

| Globulin (g/dl) | 0.37 ± 0.02b | 0.36 ± 0.02b | 0.37 ± 0.01b | 0.41 ± 0.03a |

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 9). Data in the same row with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

No significant alterations were observed on ALT, AST, ALP, and glucose levels of fish fed varying levels of G. persica (P > 0.05).

3.3. Antioxidative status

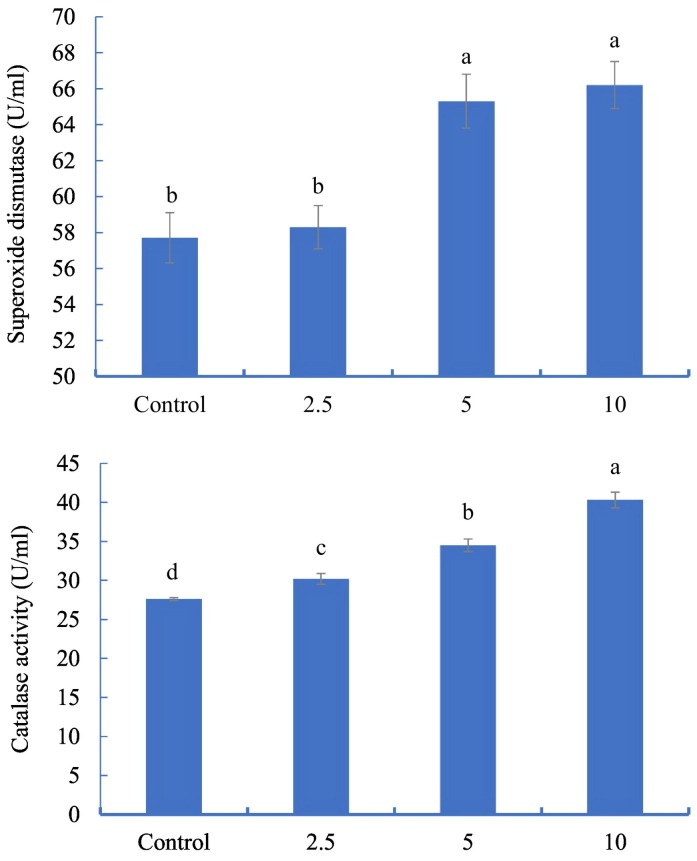

The serum superoxide dismutase was significantly increased in fish fed 5 and 10 g/kg, when compared with fish, provided the control and 2.5 g/kg diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1 ). The catalase activity (CAT) also increased significantly in fish fed G. persica when compared to the control and fish fed 10 g G. persica/kg had higher CAT than fish fed the other diets (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Superoxide dismutase and catalase activities in Acipenser persicus fed diets enriched with different levels of Gracilaria persica powder for 8 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 5). Bars with different superscript are significantly different (P < 0.05).

3.4. Serum and skin mucus immunity

Serum lysozyme and respiratory burst activities were higher in fish fed 5, and 10 g/kg than fish fed 0 and 2.5 g/kg diet (P < 0.05) (Table 6 ). Further, fish fed 10 g G. persica/kg had higher serum lysozyme and respiratory burst activities than fish fed 5 g G. persica/kg. The blood total Ig was significantly increased in fish fed 5 and 10 g/kg, when compared with fish, provided the control diet without significant differences with fish fed 2.5 g/kg diet (P < 0.05) (Table 6). The ACH50 has significantly differed among the fish provided varying levels of G. persica with the highest level in fish fed 10 g/kg and the lowest level in fish fed the control diet (P < 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Immune parameters in sera of Acipenser persicus fed diets enriched with different levels of Gracilaria persica powder for 8 weeks.

| Parameter | Control | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme activity (μ/ml/min) | 12.2 ± 0.8c | 12.9 ± 1.0c | 15.3 ± 1.1b | 18.6 ± 1.2a |

| IgM (μg/dl) | 3.52 ± 0.1b | 3.66 ± 0.21 b | 3.81 ± 0.15ab | 4.03 ± 0.07a |

| Respiratory burst activity (RLU/S) | 852.1 ± 43c | 873.0 ± 48c | 921.5 ± 52b | 1143.2 ± 71a |

| ACH50 (u/ml) | 61.2 ± 1.0d | 64.2 ± 1.2c | 73.8 ± 1.6b | 77.3 ± 1.1a |

Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 9). Values in each row with different superscripts shows significant difference (P < 0.05). Serum immunoglobulin (IgM) and the alternative complement activity (ACH50).

The level of total protein and lysozyme activity in the skin mucus were significantly higher in the blood and fillet of fish fed 5, and 10 g G. persica/kg diet than fish fed 0 and 2.5 g/kg (P < 0.05) (Table 7 ). Additionally, fish fed 10 g/kg had higher total protein and lysozyme activity than fish fed 5 g/kg (P < 0.05).

Table 7.

Total protein level, total Ig, and lysozyme activity in mucus of Acipenser persicus fed diet containing different levels of Gracilaria persica powder.

| Parameter | Control | 2.5 | 5 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The protein levels (mg/ml) | 1.10 ± 0.06c | 1.18 ± 0.1c | 1.37 ± 0.07b | 1.58 ± 0.10a |

| Lysozyme activity (IU/ml) | 5.84 ± 0.3c | 6.12 ± 0.2c | 7.92 ± 0.3b | 9.82 ± 0.4a |

| Total Ig (mg/dl) | 2.15 ± 0.07b | 2.31 ± 0.06b | 3.84 ± 0.05a | 3.78 ± 0.08a |

Data presented as mean ± S.D. of individual fish (n = 9). Values in a row with different superscripts show significant difference (P < 0.05). Serum immunoglobulin (Ig).

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth performance

G. persica appears to be one of the functional additives which have long obtained noticeable responsiveness in fish nutrition (Francavilla et al., 2013). The supplementation of G. persica can improve the efficacy of aquafeed with friendly and effective feed additives (Mohammadi et al., 2020b). In the current study, dietary G. persica had no significant impact on Persian sturgeon's growth performance and FCR, which agrees with previous studies that investigated the influence of seaweed belongs to the Gracilaria genus. Longitudinal studies concluded that dietary G. persica powder did not affect the growth performance of zebrafish (Hoseinifar et al., 2018) and European seabass (Peixoto et al., 2016). Interestingly, the results also showed that the survival rate was not impaired with dietary G. persica, which explains the safe use of G. persica in the diets of Persian sturgeon. In this context, Xu et al. (2011) reported that dietary Gracilaria lemaneiformis enhanced the growth performance of rabbitfish (Siganus canaliculatu). Conversely, dietary Gracilaria arcuate reduced the growth performance in Nile tilapia (Younis et al., 2018) and dietary G. lemaneiformis lowered the growth performance in black sea bream (Xuan et al., 2013). This contradiction refers to the species-specific effect of Gracilaria sp. on the growth performances of aquatic animals.

4.2. Carotenoid content and fillet colouration

The colouration of the fish fillet is highly requested by consumers and affected by the level of deposited carotenoids in tissue (Baghel et al., 2014). Fishes are incapable of synthesizing the carotenoids and pigments responsible for colouration and should be included through the diet (Ebeneezar et al., 2020). It is well documented that fish cannot produce carotenoids entirely, and it must be obtained from external sources such as red and green algae (Araújo et al., 2016; Ramamoorthy et al., 2010). The results of the present study indicated that the level of carotenoids was increased in the blood and fillet of Persian sturgeon fed G. persica with regards to the control. Similarly, Pezeshk et al. (2019) reported that the skin colouration of yellow cichlid was improved by dietary red macroalga (G. persica). These results confirm the possibility of using G. persica as a natural pigment for skin colouration in fish. The intensity of colouration in Persian sturgeon was probably enhanced through carotenoids ingested and assimilated in blood and fillet (Yeşilayer et al., 2020).

4.3. Haemato-biochemical indices

The evaluation of the haemato-biochemical indices is a reliable tool in the diagnosis of the physiological and health condition of fish (Fazio, 2019; Mohammadi et al., 2020c). It indicates the impact of different feed additives and feeds formulations on fish performances (Dawood et al., 2017). The results showed that fish fed G. persica powder at 5–10 g/kg had enhanced RBCs, WBCs, Hb, and Hct values. The effect of G. persica on the RBCs, WBCs, Hb, and Hct indices is probably attributed to the influence of vitamin C, polyphenols, and carotenoids which act as natural immunostimulants that compromised with the lack of anemic and outbreaks in Persian sturgeon under the current trial conditions (Francavilla et al., 2013). Concurrent with the hematological indices, the blood total protein, albumin, and globulin were increased in fish fed G. persica at 10 g/kg diet for eight weeks. The total protein is also a critical compound involved in the immune system (Dawood et al., 2020c). The enhanced total protein, albumins, and globulin are also associated with the improved immune system in Persian sturgeon due to dietary G. persica. Interestingly, G. persica mediated total protein, albumin, and globulin levels, which related to the role of G. persica in regulating the metabolism of the nutrients in fish reared under optimal conditions (Adegbeye et al., 2019). These results also confirm the balanced metabolic rate of proteins and amino acids as well as the sufficient protein content in the experimental diets. Notably, the liver function related enzymes (ALT, AST, and ALP) and glucose level showed no differences among the groups of fish fed varying levels of G. persica, which confirms the safe influence of G. persica on the liver of Persian sturgeon.

4.4. Antioxidative status

The main purpose of including medicinal herbals and their extracts in aquafeed is to maintain the antioxidative capacity (Dawood, 2020; Dawood et al., 2018). The stressful conditions impair the cell function by deteriorating the redox of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which increase the oxidative stress and harm the cell structure and damage DNA (Al-Deriny et al., 2020; Harsij et al., 2020). Several enzymes are synthesized to breakdown the high concentration of ROS and keep the antioxidative balance (Dawood et al., 2020a; Lee et al., 2004). These enzymes include CAT and SOD, which displayed enhanced values in fish, fed G. persica. Similar results were obtained by zebrafish (Danio rerio) fed on Gracilaria gracilis powder (Hoseinifar et al., 2018). The enhanced antioxidative condition is probably attributed to the high content of G. persica powder from phenols and polyphenols which has natural antioxidative activity by the degeneration of over ROS (Ahmadifar et al., 2020).

4.5. Serum and skin mucus immunity

Skin mucus is the first line of defence that protects the fish body from external and environmental stressors and invaders (Dawood et al., 2017). Medicinal herbs, seaweeds, and their extracts are potent immunostimulant factors and can enhance the serum and skin mucus immunity (Srichaiyo et al., 2020). Lysozyme is a lysis enzyme produce by granulocytes during non-specific oxygen-independent pathways that play an essential role in innate immunity (Grinde et al., 1988). In fish, the lysozyme is a very imperative humoral component in the systemic and mucosal immune system and further acts as a protective factor against pathogenic microorganisms (Saurabh and Sahoo, 2008). Persian sturgeon fed G. persica powder showed enhanced blood total protein compared to the other groups. Serum levels of Ig, ACH50, lysozyme and alternative burst activities were also enhanced by G. persica powder when compared with the control group. Consistent with our findings, Hoseinifar et al. (2018) reported that zebrafish fed on diets supplemented with Gracilaria gracilis powder had enhanced levels of total Ig and lysozyme activity. Additionally, Peixoto et al. (2016) reported that supplementation of diets of European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) with dietary Gracilaria spp. induced significant elevation of alternative complement (ACH50) and lysozyme activity when compared with control. Araújo et al. (2016) reported that dietary extract of Gracilaria vermiculophylla induced a significant enhancement of ACH50 and lysozyme activities in rainbow trout. In a similar sense, Xu et al. (2011) reported a significant elevation of serum ACH50 and lysozyme activity in Siganus canaliculatus fed on Gracilaria lemaneiformis-supplemented diets.

In fish, skin mucus has a physical structure (epithelial lining) and a chemical characters (skin mucus) which build a strong barrier between the fish and the surrounding environment (Mohammadi et al., 2020a). In our study, Persian sturgeon fed G. persica diets showed enhanced total protein, Ig, and lysozyme activity in the skin mucus when compared with the control group. Similarly, Hoseinifar et al. (2018) reported that zebrafish fed on diets supplemented with Gracilaria gracilis powder had enhanced levels of skin mucous total protein, total Ig, and lysozyme activity. Seaweeds contain abundant amounts of β-carotenes, polysaccharides, and vitamin C, which induce antioxidative and immunostimulatory influences on the organism (Francavilla et al., 2013).

5. Conclusion

The overall results indicate that G. persica can be included in the diets of Persian sturgeon at 5–10 g/kg without adverse features on the growth performances and wellbeing. Additionally, dietary G. persica enhanced the haemato-biochemical indices, serum, antioxidative capacity, and skin mucus immune responses. Attractively, G. persica increased the levels of carotenoids in the blood and fillet, which refers to its role in the colouration of Persian sturgeon.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants by any of the authors. All applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, for their financial support of this study.

References

- Abdel-Latif H.M.R., Abdel-Tawwab M., Dawood M.A.O., Menanteau-Ledouble S., El-Matbouli M. Benefits of dietary butyric acid, sodium butyrate, and their protected forms in Aquafeeds: a review. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2020:1–28. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2020.1758899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adegbeye M.J., Elghandour M.M.M.Y., Monroy J.C., Abegunde T.O., Salem A.Z.M., Barbabosa-Pliego A., Faniyi T.O. Potential influence of Yucca extract as feed additive on greenhouse gases emission for a cleaner livestock and aquaculture farming – a review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;239 [Google Scholar]

- Adel M., Dawood M.A.O., Shafiei S., Sakhaie F., Shekarabi S.P.H. Dietary Polygonum minus extract ameliorated the growth performance, humoral immune parameters, immune-related gene expression and resistance against Yersinia ruckeri in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquaculture. 2020;519 [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadifar E., Yousefi M., Karimi M., Fadaei Raieni R., Dadar M., Yilmaz S., Dawood M.A.O., Abdel-Latif H.M.R. Benefits of dietary polyphenols and polyphenol-rich additives to aquatic animal health: an overview. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2020:1–34. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2020.1818689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Deriny S.H., Dawood M.A.O., Elbialy Z.I., El-Tras W.F., Mohamed R.A. Selenium nanoparticles and spirulina alleviate growth performance, hemato-biochemical, immune-related genes, and heat shock protein in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02096-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramli M.S., Kamangar B., Nazari R.M. Effects of dietary β-glucan on the growth and innate immune response of juvenile Persian sturgeon, Acipenser persicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;47:606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo M., Rema P., Sousa-Pinto I., Cunha L.M., Peixoto M.J., Pires M.A., Seixas F., Brotas V., Beltrán C., Valente L.M.P. Dietary inclusion of IMTA-cultivated Gracilaria vermiculophylla in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) diets: effects on growth, intestinal morphology, tissue pigmentation, and immunological response. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016;28:679–689. [Google Scholar]

- Ashour M., Mabrouk M.M., Ayoub H.F., El-Feky M.M.M.M., Zaki S.Z., Hoseinifar S.H., Rossi W., Van Doan H., El-Haroun E., Goda A.M.A.S. Effect of dietary seaweed extract supplementation on growth, feed utilization, hematological indices, and non-specific immunity of Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus challenged with Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10811-020-02178-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baghel R.S., Kumari P., Reddy C.R.K., Jha B. Growth, pigments, and biochemical composition of marine red alga Gracilaria crassa. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014;26:2143–2150. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Gunasekaran G., Baby Rani P., Arul Prakash A., Prakash M., Senthil Raja J. A study on the antifungal properties of skin mucus from selected fresh water fishes. Gold. Res. Thoughts. 2013;2:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa M.J., Morais R., Choubert G. Effect of carotenoid source and dietary lipid content on blood astaxanthin concentration in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquaculture. 1999;176:331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Binaii M., Ghiasi M., Farabi S.M.V., Pourgholam R., Fazli H., Safari R., Alavi S.E., Taghavi M.J., Bankehsaz Z. Biochemical and hemato-immunological parameters in juvenile beluga (Huso huso) following the diet supplemented with nettle (Urtica dioica) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;36:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxhall P.C., Daisley K.W. Routine haematological methods for use with fish blood. J. Fish Biol. 1973;5:771–781. [Google Scholar]

- Darafsh F., Soltani M., Abdolhay H., Shamsaei Mehrejan M. Efficacy of dietary supplementation of Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis probiotics and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) on the hematological, immune response, and biochemical features of Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus) fingerlings. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2020;19:2024–2038. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M.A.O. 2020. Nutritional Immunity of Fish Intestines: Important Insights for Sustainable Aquaculture. (Reviews in Aquaculture. n/a) [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M.A.O., Koshio S., Ishikawa M., El-Sabagh M., Yokoyama S., Wang W.-L., Yukun Z., Olivier A. Physiological response, blood chemistry profile and mucus secretion of red sea bream (Pagrus major) fed diets supplemented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus under low salinity stress. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017;43:179–192. doi: 10.1007/s10695-016-0277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M.A.O., Koshio S., Esteban M.Á. Beneficial roles of feed additives as immunostimulants in aquaculture: a review. Rev. Aquac. 2018;10:950–974. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M.A.O., Abo-Al-Ela H.G., Hasan M.T. Modulation of transcriptomic profile in aquatic animals: probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics scenarios. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;97:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M.A.O., Metwally A.E.S., El-Sharawy M.E., Atta A.M., Elbialy Z.I., Abdel-Latif H.M.R., Paray B.A. The role of β-glucan in the growth, intestinal morphometry, and immune-related gene and heat shock protein expressions of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under different stocking densities. Aquaculture. 2020;523:735205. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M.A.O., El-Salam Metwally A., Elkomy A.H., Gewaily M.S., Abdo S.E., Abdel-Razek M.A.S., Soliman A.A., Amer A.A., Abdel-Razik N.I., Abdel-Latif H.M.R., Paray B.A. The impact of menthol essential oil against inflammation, immunosuppression, and histopathological alterations induced by chlorpyrifos in Nile tilapia. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;102:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeneezar S., Prabu D.L., Chandrasekar S., Tejpal C.S., Madhu K., Sayooj P., Vijayagopal P. Evaluation of dietary oleoresins on the enhancement of skin coloration and growth in the marine ornamental clown fish, Amphiprion ocellaris (Cuvier, 1830) Aquaculture. 2020;529 [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. Lysozyme activity. Tech. Fish Immunol. 1990:101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio F. Fish hematology analysis as an important tool of aquaculture: a review. Aquaculture. 2019;500:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla M., Franchi M., Monteleone M., Caroppo C. The red seaweed Gracilaria gracilis as a multi products source. Mar Drugs. 2013;11:3754–3776. doi: 10.3390/md11103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinde B., Lie Ø., Poppe T., Salte R. Species and individual variation in lysozyme activity in fish of interest in aquaculture. Aquaculture. 1988;68:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Harsij M., Gholipour Kanani H., Adineh H. Effects of antioxidant supplementation (nano-selenium, vitamin C and E) on growth performance, blood biochemistry, immune status and body composition of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) under sub-lethal ammonia exposure. Aquaculture. 2020;521 [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinifar S.H., Yousefi S., Capillo G., Paknejad H., Khalili M., Tabarraei A., Van Doan H., Spanò N., Faggio C. Mucosal immune parameters, immune and antioxidant defence related genes expression and growth performance of zebrafish (Danio rerio) fed on Gracilaria gracilis powder. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018;83:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinifar S.H., Shakouri M., Doan H.V., Shafiei S., Yousefi M., Raeisi M., Yousefi S., Harikrishnan R., Reverter M. Dietary supplementation of lemon verbena (Aloysia citrodora) improved immunity, immune-related genes expression and antioxidant enzymes in rainbow trout (Oncorrhyncus mykiss) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;99:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari A., Keramat Amirkolaie A., Oraji H., Kousha M. Bio-sorption of ammonium ions by dried red marine algae (Gracilaria persica): application of response surface methodology. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2020;19:1967–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Koo N., Min D.B. Reactive oxygen species, aging, and antioxidative nutraceuticals. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2004;3:21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2004.tb00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O.H., Rosebrough N.J., Farr A.L., Randall R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magouz F.I., Essa M., Mansour M., Dawood M.A.O. Supplementation of AQUAGEST® as a source of medium-chain fatty acids and taurine improved the growth performance, intestinal histomorphology, and immune response of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) fed low fish meal diets. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.2478/aoas-2020-0046. (000010247820200046) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi G., Rashidian G., Hoseinifar S.H., Naserabad S.S., Doan H.V. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) extract affects growth performance, body composition, haematology, serum and mucosal immune parameters in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;99:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi G., Rafiee G., El Basuini M.F., Abdel-Latif H.M.R., Dawood M.A.O. The growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunological responses, and the resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed Pistacia vera hulls derived polysaccharide. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;106:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi G., Rafiee G., El Basuini M.F., Van Doan H., Ahmed H.A., Dawood M.A.O., Abdel-Latif H.M.R. Oregano (Origanum vulgare), St John's-wort (Hypericum perforatum), and lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) extracts improved the growth rate, antioxidative, and immunological responses in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) infected with Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquac. Rep. 2020;18 [Google Scholar]

- Mohebbi A., Nematollahi A., Dorcheh E.E., Asad F.G. Influence of dietary garlic (Allium sativum) on the antioxidative status of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquac. Res. 2012;43:1184–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni M., Sajjadi M., Pourkazemi M. Growth performance and body composition of sub-yearling Persian sturgeon, (Acipenser persicus, Borodin, 1897), fed different dietary protein and lipid levels. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2007;23:204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Morshedi V., Nafisi Bahabadi M., Sotoudeh E., Azodi M., Hafezieh M. Nutritional evaluation of Gracilaria pulvinata as partial substitute with fish meal in practical diets of barramundi (Lates calcarifer) J. Appl. Phycol. 2018;30:619–628. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto M.J., Salas-Leitón E., Pereira L.F., Queiroz A., Magalhães F., Pereira R., Abreu H., Reis P.A., Gonçalves J.F.M., Ozório R.O.d.A. Role of dietary seaweed supplementation on growth performance, digestive capacity and immune and stress responsiveness in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) Aquac. Rep. 2016;3:189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Pezeshk F., Babaei S., Abedian Kenari A., Hedayati M., Naseri M. The effect of supplementing diets with extracts derived from three different species of macroalgae on growth, thermal stress resistance, antioxidant enzyme activities and skin colour of electric yellow cichlid (Labidochromis caeruleus) Aquac. Nutr. 2019;25:436–443. [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy K., Bhuvaneswari S., Sankar G., Sakkaravarthi K. Proximate composition and carotenoid content of natural carotenoid sources and its colour enhancement on marine ornamental fish Amphiprion ocellaris (Cuveir, 1880) World J. Fish Mar. Sci. 2010;2:545–550. [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh S., Sahoo P.K. Lysozyme: an important defence molecule of fish innate immune system. Aquac. Res. 2008;39:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Shah M.R., Lutzu G.A., Alam A., Sarker P., Kabir Chowdhury M.A., Parsaeimehr A., Liang Y., Daroch M. Microalgae in aquafeeds for a sustainable aquaculture industry. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018;30:197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Siwicki A., Anderson D. FAO project GCP/INT/JPA, IFI; Olsztyn, Poland: 2000. Nonspecific Defense Mechanisms Assay in Fish: II. Potential Killing Activity of Neutrophils and Macrophages, Lysozyme Activity in Serum and Organs and Total Immunoglobulin Level in Serum; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Srichaiyo N., Tongsiri S., Hoseinifar S.H., Dawood M.A.O., Esteban M.Á., Ringø E., Van Doan H. The effect of fishwort (Houttuynia cordata) on skin mucosal, serum immunities, and growth performance of Nile tilapia. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;98:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutili F.J., Gatlin D.M., Heinzmann B.M., Baldisserotto B. Plant essential oils as fish diet additives: benefits on fish health and stability in feed. Rev. Aquac. 2018;10:716–726. [Google Scholar]

- Teimouri M., Amirkolaie A.K., Yeganeh S. The effects of Spirulina platensis meal as a feed supplement on growth performance and pigmentation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquaculture. 2013;396-399:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Weber S. Determination of stabilized, added astaxanthin in fish feeds and premixes with HPLC. Anal. Methods Vitamins Caroten. 1988;1:273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Zhang L., Wu Q., Liu X., Wang S., You C., Li Y. Evaluation of dried seaweed Gracilaria lemaneiformis as an ingredient in diets for teleost fish Siganus canaliculatus. Aquac. Int. 2011;19:1007–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan X., Wen X., Li S., Zhu D., Li Y. Potential use of macro-algae Gracilaria lemaneiformis in diets for the black sea bream, Acanthopagrus schlegelii, juvenile. Aquaculture. 2013;412-413:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yano T. Assays of hemolytic complement activity. Tech. Fish Immunol. 1992:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yeşilayer N., Mutlu G., Yıldırım A. Effect of nettle (Urtica spp.), marigold (Tagetes erecta), alfalfa (Medicago sativa) extracts and synthetic xanthophyll (zeaxanthin) carotenoid supplementations into diets on skin pigmentation and growth parameters of electric yellow cichlid (Labidochromis caeruleus) Aquaculture. 2020;520 [Google Scholar]

- Younis E.-S.M., Al-Quffail A.S., Al-Asgah N.A., Abdel-Warith A.-W.A., Al-Hafedh Y.S. Effect of dietary fish meal replacement by red algae, Gracilaria arcuata, on growth performance and body composition of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018;25:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]