Abstract

Effective, sensitive, and reliable diagnostic reagents are of paramount importance for combating the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic when there is neither a preventive vaccine nor a specific drug available for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It will cause a large number of false-positive and false-negative tests if currently used diagnostic reagents are undermined. Based on genotyping of 31,421 SARS-CoV-2 genome samples collected up to July 23, 2020, we reveal that essentially all of the current COVID-19 diagnostic targets have undergone mutations. We further show that SARS-CoV-2 has the most mutations on the targets of various nucleocapsid (N) gene primers and probes, which have been widely used around the world to diagnose COVID-19. To understand whether SARS-CoV-2 genes have mutated unevenly, we have computed the mutation rate and mutation h-index of all SARS-CoV-2 genes, indicating that the N gene is one of the most non-conservative genes in the SARS-CoV-2 genome. We show that due to human immune response induced APOBEC mRNA (C > T) editing, diagnostic targets should also be selected to avoid cytidines. Our findings might enable optimally selecting the conservative SARS-CoV-2 genes and proteins for the design and development of COVID-19 diagnostic reagents, prophylactic vaccines, and therapeutic medicines.

Availability

Interactive real-time online Mutation Tracker.

Highlights

-

•

Essentially all of the current COVID-19 diagnostic targets have undergone mutations.

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) gene primers and probes have the most mutations.

-

•

It would be better to select diagnostic targets avoiding cytidines.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was first reported in Wuhan in December 2019, is an unsegmented positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the β-coronavirus genus and coronaviridae family. Coronaviruses are some of the most sophisticated viruses with their genome size ranging from 26 to 32 kilobases in length. Caused by SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak has spread to more than 200 countries and territories with more than 15,012,731 infection cases and 619,150 fatalities worldwide by July 23, 2020 [1]. Additionally, travel restrictions, quarantines, and social distancing measures have essentially put the global economy on hold. Furthermore, since there is neither specific medication nor vaccine for COVID-19 at this moment, economy reopening depends vitally on effective COVID-19 diagnostic testing, patient isolation, contact tracing, and quarantine. Reliable diagnostic testing kits are critical and essential for combating COVID-19.

There are three types of diagnostic tests for COVID-19, namely polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, antibody tests, and antigen tests. PCR tests detect the genetic material from the virus. Antibody tests, also called serological tests, examine the presence of antibodies produced from immune response to the virus infection. The antigen tests detect the presence of viral antigens, e.g., parts of the viral spike protein. The PCR tests are relatively more accurate but take time to show the test result. The protein tests based on antibody or antigen can display test results in minutes but are relatively insensitive and subject to host immune response limitations.

PCR diagnostic test reagents were designed based on early clinical specimens containing a full spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 [2], particularly the reference genome collected on January 5, 2020, in Wuhan (SARS-CoV-2, NC004718) [3]. Approved by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has detailed guidelines for COVID-19 diagnostic testing, called “CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel” (https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/download). The US CDC has designated two oligonucleotide primers from regions of the virus nucleocapsid (N) gene, i.e., N1 and N2, as probes for the specific detection of SARS-CoV-2. The panel has also selected an additional primer/probe set, the human RNase P gene (RP), as control samples. Many other diagnostic primers and probes based on RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), envelope (E), nonstructural protein 14 (NSP14), and nucleocapsid (N) genes have been designed [4] and/or designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as shown in Table S1 of the Supporting Material, which provides the details of 54 commonly used diagnostic primers and probes [5]. The diagnostic kits are often static over time, yet SARS-CoV-2 is undergoing fast mutations. Hence, it is reported that different primers and probes show nonuniform performance [[6], [7], [8]].

In this study, we genotype 31,421 SARS-CoV-2 genome isolates in the globe and reveal numerous mutations on the COVID-19 diagnostic targets commonly used around the world, including those designated by the US CDC. We identify and analyze the SARS-CoV-2 mutation positions, frequencies, and encoded proteins in the global setting. These mutations may impact the diagnostic sensitivity and specialty, and therefore, they should be considered in designing new testing kits as the current effort in COVID-19 testing, prevention, and control. We propose diagnostic target selection and optimization based on nucleotide-based and gene-based mutation-frequency analysis.

2. Results and analysis

2.1. Genotyping analysis

We first genotype 31,421 SARS-CoV-2 genome samples from the globe as of July 23, 2020. The genotyping results unravel 13,402 single mutations among these virus isolates. Typically, a SARS-CoV-2 isolate can have eight co-mutations on average. A large number of mutations may occur on all of the SARS-CoV-2 genes and have broad effects on diagnostic kits, vaccines, and drug developments. Moreover, we cluster these mutations by K-means methods, resulting in globally at least six distinct subtypes of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes, from Cluster I to Cluster VI. Table 1 shows the mutation distribution clusters with sample counts (SC) and total single mutation counts (MC) in 20 countries.

Table 1.

The mutation distribution clusters with sample counts (SC) and total single mutation counts (MC).

| Cluster I |

Cluster II |

Cluster III |

Cluster IV |

Cluster V |

Cluster VI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | SC | MC | SC | MC | SC | MC | SC | MC | SC | MC | SC | MC |

| US | 3252 | 24,846 | 2013 | 14,737 | 286 | 3686 | 2366 | 27,012 | 562 | 3798 | 304 | 2706 |

| CA | 113 | 835 | 80 | 561 | 9 | 106 | 42 | 417 | 84 | 525 | 33 | 290 |

| AU | 173 | 1204 | 587 | 5048 | 75 | 1010 | 195 | 2127 | 165 | 885 | 132 | 1076 |

| DE | 69 | 504 | 25 | 121 | 5 | 58 | 26 | 209 | 27 | 144 | 43 | 366 |

| FR | 100 | 718 | 14 | 55 | 2 | 22 | 48 | 523 | 74 | 465 | 10 | 83 |

| UK | 295 | 2328 | 1927 | 12,777 | 2171 | 27,636 | 1623 | 16,123 | 1890 | 11,835 | 2919 | 25,576 |

| IT | 1 | 8 | 8 | 104 | 33 | 561 | 24 | 308 | 57 | 283 | 24 | 192 |

| RU | 7 | 52 | 2 | 32 | 19 | 219 | 7 | 53 | 32 | 187 | 119 | 968 |

| CN | 3 | 22 | 287 | 1155 | 2 | 32 | 7 | 50 | 8 | 35 | 3 | 26 |

| JP | 18 | 134 | 243 | 1001 | 23 | 272 | 9 | 79 | 23 | 139 | 191 | 1676 |

| KR | 0 | 0 | 58 | 327 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IN | 29 | 212 | 268 | 3045 | 200 | 2703 | 399 | 4840 | 141 | 847 | 51 | 487 |

| IS | 66 | 446 | 103 | 595 | 30 | 345 | 10 | 89 | 152 | 924 | 59 | 525 |

| ES | 4 | 33 | 163 | 1198 | 3 | 33 | 37 | 365 | 170 | 1103 | 42 | 359 |

| BR | 3 | 26 | 7 | 51 | 78 | 1009 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 42 | 63 | 591 |

| BE | 56 | 411 | 85 | 400 | 66 | 783 | 115 | 1031 | 230 | 1381 | 141 | 1239 |

| SA | 16 | 110 | 9 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 126 | 17 | 133 | 1 | 7 |

| TR | 0 | 0 | 28 | 339 | 13 | 158 | 50 | 476 | 4 | 28 | 31 | 273 |

| PE | 2 | 12 | 5 | 36 | 10 | 124 | 5 | 48 | 9 | 58 | 2 | 17 |

| CL | 13 | 91 | 27 | 282 | 21 | 285 | 49 | 665 | 32 | 200 | 20 | 169 |

The listed countries are United States (US), Canada (CA), Australia (AU), Germany (DE), France (FR), United Kingdom (UK), Italy (IT), Russia (RU), China (CN), Japan (JP), Korean (KR), India (IN), Iceland (IS), Brazil (BR), Spain (ES), Belgium (BE), Saudi Arabia (SA), Turkey (TR), Peru(PE), and Chile (CL).

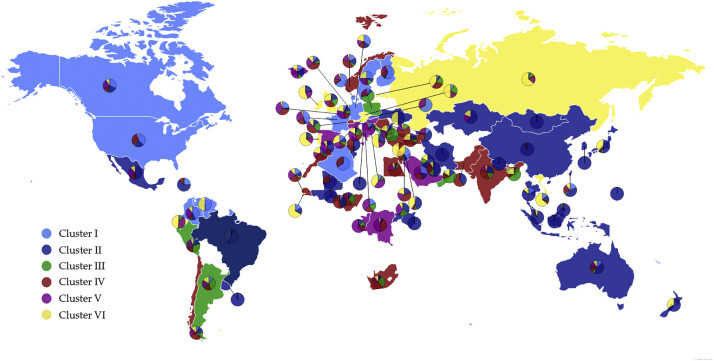

All of the countries are involved in six clusters except Korean (KR), Saudi Arabia (SA), and Turkey (TR). Among them, China initially had samples only in clusters II and its sample distributions reached to other Clusters after March 2020. Cluster I, II, and IV are dominated in the United States. Germany (DE) and France (FR) samples are mainly in Cluster I, IV, and VI. Italy (IT) samples are mainly in Clusters III, IV, V, and VI. Samples in Turkey (TR) are mainly in Cluster II, III, IV, and VI. Japan (JP) samples are dominated in Cluster II and VI, Korea (KR) samples belong to Cluster II only. Cluster II is common to all countries. Fig. 1 depicts the distribution of six distinct clusters in the world. The light blue, dark blue, green, red, pink, and yellow represent Cluster I, Cluster II, Cluster III, Cluster IV, Cluster V, and Cluster VI, respectively. The color of the dominated Cluster decides the base color of each country. To be noted, although some countries have a lot of confirmed sequences, a very limited number of complete genome sequences are deposited in the GISAID, which causes the geographical bias in the Table 1.

Fig. 1.

The scatter plot of six distinct clusters in the world. The light blue, dark blue, green, red, pink, and yellow represent Cluster I, Cluster II, Cluster III, Cluster IV, Cluster V, and Cluster VI, respectively. The base color of each country is decided by the color of the dominated Cluster. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

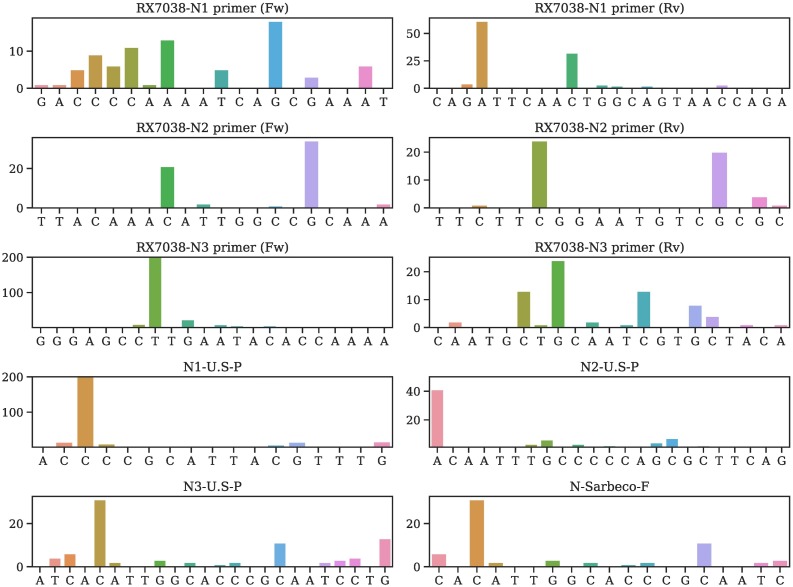

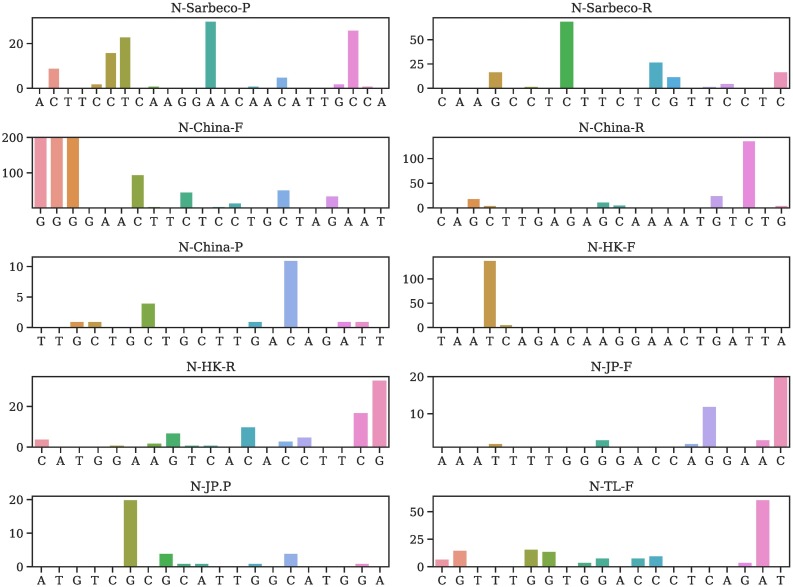

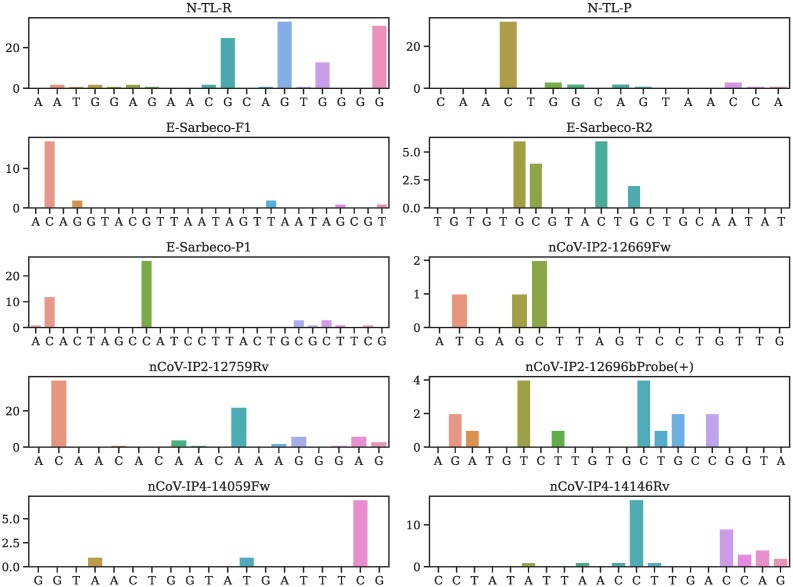

2.2. Mutations on diagnostic targets

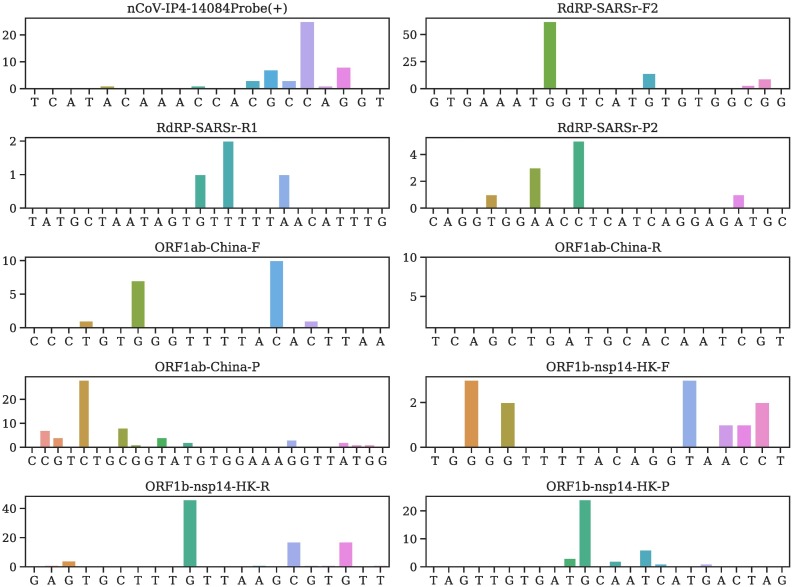

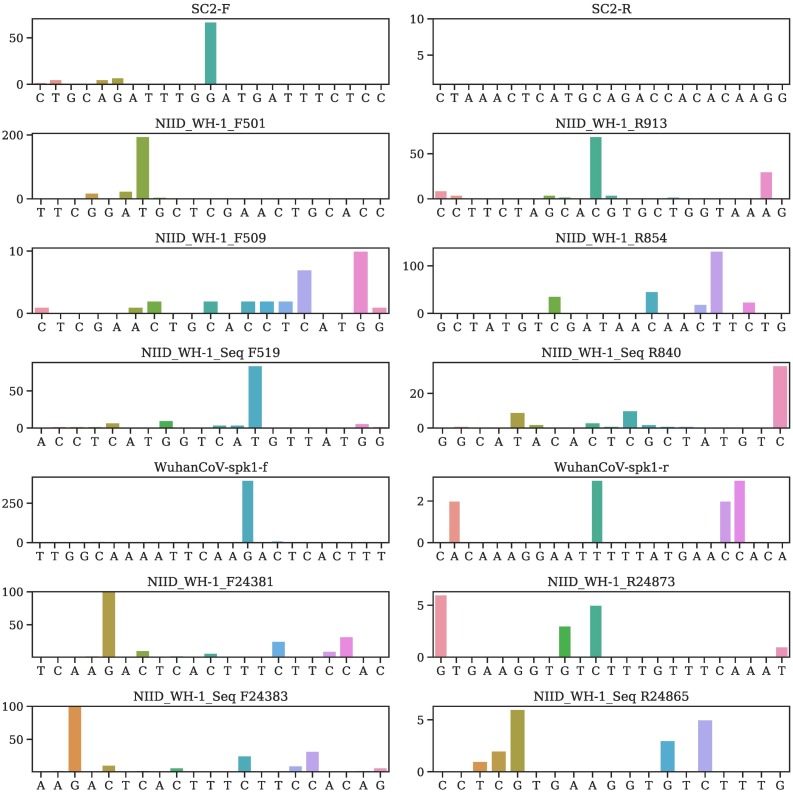

Table 2 provides all mutations on various primers and probes and their occurring frequencies in various clusters, where SC is the sample counts and MC is the mutation counts. More detailed mutation information is given in Tables S4–S56 of the Supporting Material. We plot the mutation position and frequency for 54 primers and probes in this work in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and Fig. 6 .

Table 2.

Summary of mutations on COVID-19 diagnostic primers and probes and their occurrence frequencies in clusters. Here, SC is the sample counts and MC is the mutation counts.

| Primer | MC | SC | Cluster I | Cluster II | Cluster III | Cluster IV | Cluster V | Cluster VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RX7038-N1 primer (Fw)a | 15 | 79 | 5 | 14 | 12 | 28 | 14 | 6 |

| RX7038-N1 primer (Rv)a | 17 | 113 | 1 | 66 | 14 | 9 | 2 | 21 |

| RX7038-N2 primer (Fw)a | 7 | 60 | 3 | 10 | 24 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| RX7038-N2 primer (Rv)a | 6 | 50 | 2 | 17 | 6 | 15 | 3 | 7 |

| RX7038-N3 primer (Fw) [9] | 13 | 287 | 4 | 224 | 13 | 26 | 14 | 6 |

| RX7038-N3 primer (Rv) [9] | 12 | 70 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 39 | 6 | 4 |

| N1-U.S.-P [5] | 15 | 856 | 4 | 782 | 20 | 31 | 15 | 4 |

| N2-U.S.-P [5] | 11 | 70 | 10 | 40 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| N3-U.S.-P [5] | 16 | 84 | 5 | 27 | 15 | 21 | 10 | 6 |

| N-Sarbeco-Fb [4] | 12 | 63 | 4 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 4 |

| N-Sarbeco-Pb [4] | 12 | 116 | 1 | 19 | 30 | 42 | 15 | 9 |

| N-Sarbeco-Rb [4] | 17 | 156 | 37 | 26 | 4 | 80 | 5 | 4 |

| N-China-F [5] | 23 | 26,280 | 38 | 226 | 10,873 | 139 | 17 | 14,987 |

| N-China-R [5] | 17 | 217 | 5 | 15 | 17 | 157 | 8 | 15 |

| N-China-P [5] | 7 | 20 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| N-HK-F [5] | 5 | 149 | 1 | 2 | 74 | 7 | 1 | 64 |

| N-HK-R [5] | 14 | 84 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 35 | 4 | 5 |

| N-JP-F [5] | 10 | 66 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 16 | 26 | 0 |

| N-JP-P [5] | 9 | 32 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 7 |

| N-TL-F [5] | 17 | 149 | 1 | 84 | 14 | 31 | 13 | 6 |

| N-TL-R [5] | 17 | 115 | 29 | 7 | 7 | 66 | 3 | 3 |

| N-TL-P [5] | 11 | 45 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 20 |

| E-Sarbeco-F1c | 5 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 2 |

| E-Sarbeco-R2c | 4 | 18 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| E-Sarbeco-P1c | 9 | 48 | 1 | 29 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| nCoV-IP2-12669Fwc | 3 | 50 | 0 | 17 | 12 | 11 | 0 | 10 |

| nCoV-IP2-12759Rvc | 11 | 739 | 123 | 244 | 77 | 168 | 127 | 0 |

| nCoV-IP2-12696bProbe(+)c | 8 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| nCoV-IP4-14059Fwc | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| nCoV-IP4-14146Rvc | 11 | 38 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 5 |

| nCoV-IP4-14084Probe(+)c | 11 | 49 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 19 | 5 | 4 |

| RdRP-SARSr-F2d | 5 | 89 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 37 | 44 | 0 |

| RdRP-SARSr-R1d [4] | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| RdRP-SARSr-P2d [4] | 4 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| ORF1ab-China-F [5] | 4 | 19 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 |

| ORF1ab-China-R [5] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ORF1ab-China-P [5] | 14 | 61 | 1 | 6 | 30 | 11 | 3 | 10 |

| ORF1b-nsp14-HK-F [5] | 6 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| ORF1b-nsp14-HK-R [5] | 9 | 89 | 3 | 9 | 52 | 14 | 6 | 5 |

| ORF1b-nsp14-HK-P [5] | 6 | 37 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 13 | 0 | 12 |

| SC2-Fe | 11 | 88 | 0 | 5 | 34 | 29 | 13 | 7 |

| SC2-Re | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NIID_WH-1_F501 [10] | 13 | 255 | 0 | 205 | 25 | 18 | 3 | 4 |

| NIID_WH-1_R913 [10] | 14 | 128 | 1 | 94 | 9 | 18 | 4 | 2 |

| NIID_WH-1_F509 [10] | 10 | 30 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| NIID_WH-1_R854 [10] | 9 | 261 | 63 | 25 | 33 | 117 | 5 | 18 |

| NIID_WH-1_Seq F519 [10] | 19 | 130 | 8 | 89 | 17 | 11 | 3 | 2 |

| NIID_WH-1_Seq R840 [10] | 12 | 66 | 6 | 9 | 21 | 8 | 3 | 19 |

| WuhanCoV-spk1-f [10] | 14 | 433 | 265 | 22 | 11 | 123 | 8 | 4 |

| WuhanCoV-spk1-r [10] | 4 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| NIID_WH-1_F24381 [10] | 20 | 494 | 275 | 30 | 16 | 153 | 13 | 7 |

| NIID_WH-1_R24873 [10] | 5 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| NIID_WH-1_Seq_F24383 [10] | 21 | 503 | 275 | 30 | 22 | 153 | 13 | 10 |

| NIID_WH-1_Seq_R24865 [10] | 6 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 2.

Illustration of mutation positions and frequencies on the primer and/or probes of RX7038-N1 primer (Fw), RX7038-N1 primer (Rv), RX7038-N2 primer (Fw), RX7038-N2 primer (Rv), RX7038-N3 primer (Fw), RX7038-N3 primer (Rv), N1-U.S.-P, N2-U.S.-P, N3-U.S.-P, N-Sarbeco-F.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of mutation positions and frequencies on the primer and/or probes of N-Sarbeco-P, N-Sarbeco-R, N-China-F, N-China-R, N-China-P, N-HK-F, N-HK-R, N-JP-F, N-JP-P, N-TL-F.

Fig. 4.

Illustration of mutation positions and frequencies on the primer and/or probes of N-TL-R, N-TL-P, E-Sarbeco-F1, E-Sarbeco-R2, E-Sarbeco-P1, nCoV-IP2-12669Fw, nCoV-IP2-12759Rv, nCoV-IP2-12696bProbe(+), nCoV-IP4-14059Fw, nCoV-IP4-14146Rv.

Fig. 5.

Illustration of mutation positions and frequencies on the primer and/or probes of nCoV-IP4-14084Probe(+), RdRP-SARSr-F2, RdRP-SARSr-R1, RdRP-SARSr-P2, ORF1ab-China-F, ORF1ab-China-R, ORF1ab-China-P, ORF1b-nsp14-HK-F, ORF1b-nsp14-HK-R, ORF1b-nsp14-HK-P.

Fig. 6.

Illustration of mutation positions and frequencies on the primer and/or probes of SC2-F, SC2-R,NIID_WH-1_F501,NIID_WH-1_R913, NIID_WH-1_F509, NIID_WH-1_R85, NIID_WH-1_Seq F519, NIID_WH-1_Seq R840, WuhanCoV-spk1-f, WuhanCoV-spk1-r, NIID_WH-1_F24381, NIID_WH-1_R24873, NIID_WH-1_Seq F24383, NIID_WH-1_Seq R24865.

It is noted that N-China-F [5] is the mostly-used reagent among all primers/probes, but the primer target gene of SARS-CoV-2 has 15 mutations involving thousands of samples, which may account for low efficacy of certain COVID-19 diagnostic kits in China [11]. Note that primers and probes typically have a small length of around 20 nucleotides.

Currently, most primers and probes used in the US target are the N gene [5]. However, Table 2 shows that a plurality of mutations has been found in all of the targets of the US CDC designated COVID-19 diagnostic primers. The targets of N gene primers and probes used in Japan, Thailand, and China, including Hong Kong, have undergone multiple mutations involving many clusters. Therefore, the N gene may not be an optimal target for diagnostic kits, and the current test kits targeting the N gene should be updated accordingly for testing accuracy.

It can be seen that so far, no mutation has been detected on ORF1ab-China-R and SC2-R, showing that they are two relatively reliable diagnostic primers.

Notably, the targets of four E gene primers and probes have only six mutations.Also, no mutation has been found on the targets of ORF1ab-China-R and SC2-R. However, the target of nCoV-IP2-12759R recommended by Institute Pasteur, Paris has six mutations. Overall, targets of the envelope and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase based primers and probes have fewer mutations than the N gene. This observation leads to an assumption that the N gene is particularly prone to mutations.

3. Discussion

3.1. Mechanisms of mutation and mutation impact on diagnostics

The accumulation of the frequency of virus mutations is due to the natural selection, polymerase fidelity, cellular environment, features of recent epidemiology, random genetic drift, host immune responses, gene editing [12], replication mechanism, etc. [13,14]. SARS-CoV-2 has a higher fidelity in its transcription and replication process than other single-stranded RNA viruses because it has a proofreading mechanism regulated by NSP14 [15]. However, 13,402 single mutations have been detected from 31,421 SARS-CoV-2 genome isolates.

Due to technical constraints, genome sequencing is subject to errors. Some “mutations” might result from sequencing errors, instead of actual mutations. Additionally, mRNA editing, such as APOBEC [12], in defending virus invasion in the human immune system can create fatal mutations. Both cases may lead to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) without a descendant. We report that among all of 31,421 genome isolates, 13,402 individual mutations have at least one descendant.

It is well known that the sensitivity of diagnostic primers and probes depends on their target positions. Specifically, the beginning part of a primer or probe is not as important as its ending part. A high-frequency mutation on the right end of a primer or probe position of a target would possibly produce more false-negatives in diagnostics. Also, importantly, for primers involving significant mutations, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) annealing temperatures are estimated based on correctly matched sequences [16]. Annealing temperatures for primers and probes involving mutations of are given in Tables S4–S56 of the Supporting Material.

3.2. Nucleotide-based diagnostic target optimization

Table 2 shows that the degree of mutations on various diagnostic targets vary dramatically. Therefore, it is of great importance to know how to select an optimal viral diagnostics target to avoid potential mutations. We discuss such a target optimization via both nucleotide-based analysis and gene-based mutation analysis.

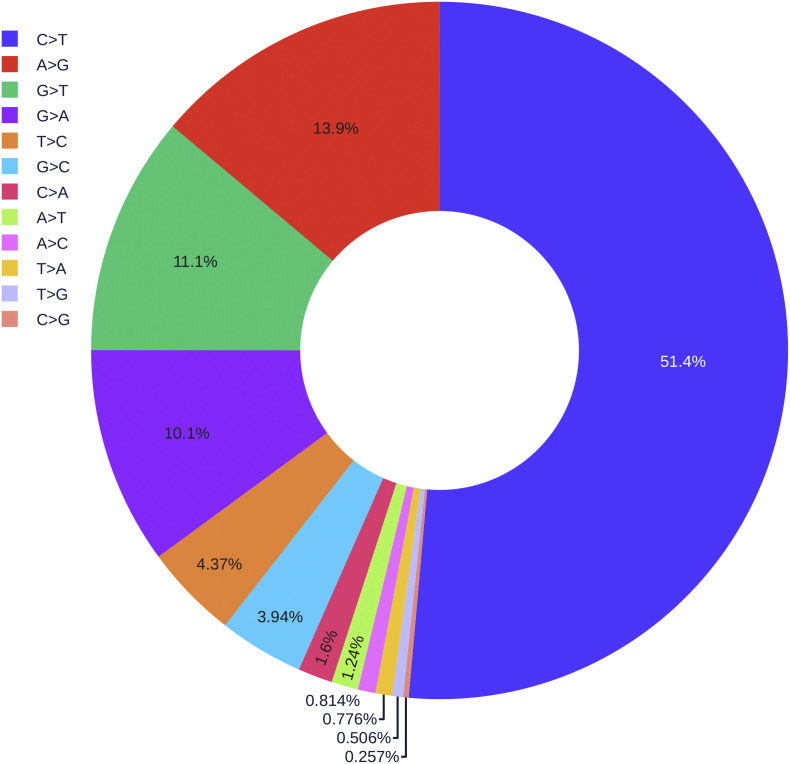

Fig. 7 illustrates the rates of 12 different types of mutations among 31,421 SNP variants. It is interesting to note that 51.4% mutations on the SARS-CoV-2 are of C>T type, due to strong host cell mRNA editing knows as APOBEC cytidine deaminase [12]. Therefore, researchers should avoid cytosine bases as much as possible when designing the diagnostic test kits.

Fig. 7.

The pie chart of the distribution of 12 different types of mutations.

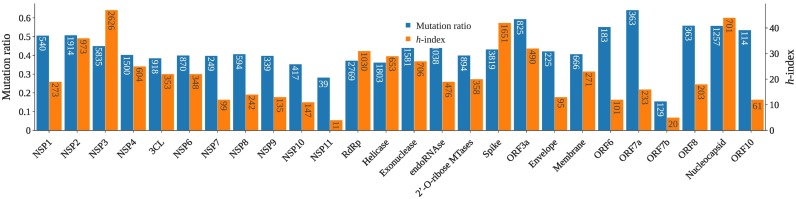

3.3. Gene-based diagnostic target optimization

To further understand how to design the most reliable SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic targets, we carry out gene-level mutation analysis. Fig. 8 and Table 3 present the mutation ratio, i.e., the number of unique single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) over the corresponding gene length, for each SARS-CoV-2 gene. A smaller mutation ratio for a given gene indicates a higher degree of conservativeness. Clearly, the ORF7b gene has the smallest mutation ratio of 0.155, while the ORF7a gene has the largest mutation ratio of 0.642. The N gene has the fourth-largest mutation rate of 0.558, which is very close to the largest ratio of 0.594 for the ORF3a gene and 0.559 for the ORF8 gene. Additionally, two ends of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, i.e., NSP1, NSP2, ORF10, N gene, ORF8, ORF7a, and ORF6, exception for ORF7b, have higher mutation ratios. Considering the mutation frequency, we introduce the mutation h-index, defined as the maximum value of h such that the given gene section has h single mutations that have each occurred at least h times. Normally, larger genes tend to have a higher h-index. Fig. 8 shows that, with a moderate length, the N gene has the second-largest h-index of 44, which is close to the largest h-index of 47 for NSP3. Therefore, selecting SARS-CoV-2 N gene primers and probes as diagnostic reagents for combating COVID-19 is not an optimal choice. Moreover, a few primers and probes used in Japan are designed on the spike and NSP2 gene. However, the high mutation ratio and h-index of spike and NSP2 gene indicate that these diagnostic reagents may not perform well. Furthermore, we design a website called Mutation Tracker to track the single mutations on 26 SARS-CoV-2 proteins, which will be an intuitive tool to inform other research on regions to be avoided in future diagnostic test development.

Fig. 8.

Illustration of SARS-CoV-2 mutation ratio and mutation h-index one various genes. For each gene, its length is given in the mutation ratio bar while the number of unique SNPs is given in the h-index bar.

Table 3.

Gene-specific statistics of SARS-CoV-2 single mutations on 26 proteins.

| Gene type | Gene site | Gene length | Unique SNPs | mutation ratio | h-index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP1 | 266:805 | 540 | 273 | 0.506 | 19 |

| NSP2 | 806:2719 | 1914 | 973 | 0.508 | 36 |

| NSP3 | 2720:8554 | 5835 | 2626 | 0.450 | 47 |

| NSP4 | 8555:10054 | 1500 | 604 | 0.403 | 25 |

| NSP5(3CL) | 10,055:10972 | 918 | 353 | 0.385 | 22 |

| NSP6 | 10,973:11842 | 870 | 348 | 0.400 | 22 |

| NSP7 | 11,843:12091 | 249 | 99 | 0.398 | 12 |

| NSP8 | 12,092:12685 | 594 | 242 | 0.407 | 14 |

| NSP9 | 12,686:13024 | 339 | 135 | 0.398 | 13 |

| NSP10 | 13,025:13441 | 417 | 147 | 0.353 | 11 |

| NSP11 | 13,442:13480 | 39 | 11 | 0.282 | 4 |

| RNA-dependent-polymerase | 13,442:16236 | 2796 | 1030 | 0.368 | 31 |

| Helicase | 16,237:18039 | 1803 | 653 | 0.362 | 29 |

| 3′-to-5′ exonuclease | 18,040:19620 | 1581 | 706 | 0.447 | 27 |

| endoRNAse | 19,621:20658 | 1038 | 476 | 0.459 | 19 |

| 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase | 20,659:21552 | 894 | 358 | 0.400 | 20 |

| Spike protein | 21,563:25384 | 3819 | 1651 | 0.432 | 42 |

| ORF3a protein | 25,393:26220 | 825 | 490 | 0.594 | 32 |

| Envelope protein | 26,245:26472 | 225 | 95 | 0.422 | 13 |

| Membrane glycoprotein | 26,523:27191 | 666 | 271 | 0.407 | 23 |

| ORF6 protein | 27,202:27387 | 183 | 101 | 0.552 | 12 |

| ORF7a protein | 27,394:27759 | 363 | 233 | 0.642 | 16 |

| ORF7b protein | 27,756:27887 | 129 | 20 | 0.155 | 5 |

| ORF8 protein | 27,894:28259 | 363 | 203 | 0.559 | 18 |

| Nucleocapsid protein | 28,274:29533 | 1257 | 701 | 0.558 | 44 |

| ORF10 protein | 29,558:29674 | 114 | 61 | 0.535 | 12 |

4. Conclusion

In summary, the targets of currently used COVID-19 diagnostic tests have numerous mutations that impact the diagnostic test accuracy in combating COVID-19. There is a need for continued surveillance of viral evolution and diagnostic test performance, as the emergence of viral variants that are no longer detectable by certain diagnostics tests is a real possibility. A cocktail test kit is needed to mitigate mutations. We propose nucleotide-based and gene-based diagnostic target optimizations to design the most reliable diagnostic targets. We analyze a full list of SNPs for all 31,421 genome isolates, including their positions and mutation types. This information, together with ranking of the degree of the conservativeness of SARS-CoV-2 genes or proteins given in Table 3, enables researchers to avoid non-conservative genes (or their proteins) and mutated nucleotide segments in designing COVID-19 diagnosis, vaccine, and drugs.

5. Methods and materials

SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences from infected individuals dated between January 5, 2020, and July 23, 2020, are downloaded from the GISAID database [17] (https://www.gisaid.org/). We only consider the records in GISAID with complete genomes (>29,000 bp) and submission dates. The resulting 31,421 complete genome sequences are rearranged according to the reference SARS-CoV-2 genome [3] by using the Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment with default parameters [18]. Gene variants are recorded as SNPs. The Jaccard distance [19] is employed to compute the similarities among genome samples. The resulting distance matrix is used in the k-means clustering of all genome samples.

5.1. Jaccard distance of SNP variants

The Jaccard distance measures the dissimilarity between SNP variants which is widely used in the phylogenetic analysis of human or bacterial genomes. Given two sets A, B, we first define the Jaccard similarity coefficient:

| (1) |

and the Jaccard distance is described as the difference between one and the Jaccard similarity coefficient

| (2) |

5.2. K-means clustering

As an unsupervised classification algorithm, the K-means clustering method partitions a given dataset X={x 1, x 2, ⋯, x n, ⋯, x N}, x n ∈ ℝd into k different clusters {C 1, C 2, ⋯, C k}, k ≤ N such that the specific clustering criteria are optimized. The standard procedure of k-means clustering method aims to obtain the optimal partition for a fixed number of clusters. First, we randomly pick k points as the cluster centers and then assign each data to its nearest cluster. Next, we calculate the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) defined below to update the cluster centers iteratively.

| (3) |

where μ k is the mean value of the points located in the k-th cluster C k. Here, ∥ ⋅ ∥2 denotes the L 2 distance. It is noted that the k-mean clustering method described above aims to find the optimal partition for a fixed number of clusters. However, seeking the best number of clusters for the SNP variants is essential as well. In this work, by varying the number of clusters k, a set of WCSS with its corresponding number of clusters can be plotted. The location of the elbow in this plot will be taken as the optimal number of clusters. Such a procedure is called the Elbow method which is frequently applied in the k-means clustering problem.

Specifically, in this work we apply the k-means clustering with the Elbow method for the analysis of the optimal number of the subtypes of SARS-CoV-2 SNP variants. The pairwise Jaccard distances between different SNP variants are considered as the input features for the k-means clustering method.

Note added in proof

During the review process of the manuscript, which was published in ArXiv [20], Khan et al. analyzed the presence of the mutations/mismatches on 27 diagnostics assays [21]. In this interesting work, the authors showed the geographical distribution and the mismatches for the N ‐ China ‐ F, N1 ‐ U. S ‐ P, and RX7038 ‐ N1 primer(Fw), revealing that the variants from Europe are more likely to have mutations on the N-China-F. Moreover, N1 ‐ U. S ‐ P and RX7038 ‐ N1 primer(Fw) are not suitable for the people from Asia and Oceania.

Data availability

The nucleotide sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes used in this analysis are available, upon free registration, from the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org/). Supporting Material presents a list of 54 commonly used diagnostic primers and probes and tables of mutation details on 54 diagnostic primers and probes. The acknowledgments of the SARS-COV-2 genomes are also given in the Supporting Material.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank The IBM TJ Watson Research Center, The COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium, and NVIDIA for computational assistance. GWW thanks Dr. Jeremy S Rossman for valuable comments. This work was supported in part by NIH grant GM126189, NSF Grants DMS-1721024, DMS-1761320, and IIS1900473, Michigan Economic Development Corporation, George Mason University award PD45722, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.09.028.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

References

- 1.WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-185 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan J.F.-W., Yip C.C.-Y., To K.K.W., Tang T.H.-C., Wong S.C.-Y., Leung K.-H., Fung A.Y.-F., Ng A.C.-K., Zou Z., Tsoi H.-W. Improved molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 by the novel, highly sensitive and specific COVID-19-rdrp/hel real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay validated in vitro and with clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(5) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00310-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., Hu Y., Tao Z.-W., Tian J.-H., Pei Y.-Y. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corman M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., Bleicker T., Brünink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Udugama B., Kadhiresan P., Kozlowski H.N., Malekjahani A., Osborne M., Li V.Y., Chen H., Mubareka S., Gubbay J., Chan W.C. Diagnosing COVID-19: the disease and tools for detection. ACS Nano. 2020;14(4):3822–3835. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung Y.J., Park G.-S., Moon J.H., Ku K., Beak S.-H., Kim S., Park E.C., Park D., Lee J.-H., Byeon C.W. Comparative analysis of primer-probe sets for the laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv. 2020;6(9):2513–2523. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfefferle S., Reucher S., Nörz D., Lütgehetmann M. Evaluation of a quantitative RT-PCR assay for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 using a high throughput system. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(9):2000152. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogels C.B., Brito A.F., Wyllie A.L., Fauver J.R., Ott I.M., Kalinich C.C., Petrone M.E., Landry M.-L., Foxman E.F., Grubaugh N.D. Analytical sensitivity and efficiency comparisons of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR assays. medRxiv. 2020;5:1299–1305. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0761-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nalla A.K., Casto A.M., Huang M.-L.W., Perchetti G.A., Sampoleo R., Shrestha L., Wei Y., Zhu H., Jerome K.R., Greninger A.L. Comparative performance of SARS-CoV-2 detection assays using seven different primer/probe sets and one assay kit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(6) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00557-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirato Kazuya, Nao Naganori, Katano Harutaka, Takayama Ikuyo, Saito Shinji, Kato Fumihiro, Katoh Hiroshi, Sakata Masafumi, Nakatsu Yuichiro, Mori Yoshio. Development of genetic diagnostic methods for novel coronavirus 2019 (nCoV-2019) in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;2020 doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.061. pages JJID. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinese Firm to Replace Clinical Laboratory Test Kits after Spanish Health Authorities Report Tests from Chinas Shenzen Bioeasy Were Only 30% Accurate. 2020. https://www.darkdaily.com/chinese-firm-to-replace-clinical-laboratory-test-kits-after-spanish-health-authorities-report-tests-from-chinas-shenzen-bioeasy-were-only-30-accurate/

- 12.Bishop Kate N., Holmes Rebecca K., Sheehy Ann M., Malim Michael H. APOBEC-mediated editing of viral RNA. Science. 2004;305(5684):645. doi: 10.1126/science.1100658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanjuán Rafael, Domingo-Calap Pilar. Mechanisms of viral mutation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73(23):4433–4448. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grubaugh Nathan D., Hanage William P., Rasmussen Angela L. Making sense of mutation: what D614G means for the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. Cell. 2020;182(4):794–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sevajol Marion, Subissi Lorenzo, Decroly Etienne, Canard Bruno, Imbert Isabelle. Insights into RNA synthesis, capping, and proofreading mechanisms of SARS-coronavirus. Virus Res. 2014;194:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allawi Hatim T., SantaLucia John. Thermodynamics and NMR of internal G.T mismatches in DNA. Biochemistry. 1997;36(34):10581–10594. doi: 10.1021/bi962590c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shu Y., McCauley J. Gisaid: global initiative on sharing all influenza data–from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22(13) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sievers F., Higgins D.G. Clustal omega. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2014;48(1):3–13. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0313s48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levandowsky M., Winter D. Distance between sets. Nature. 1971;234(5323):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Rui, Hozumi Yuta, Yin Changchuan, Wei Guo-Wei. Mutations on COVID-19 diagnostic targets. arXiv preprint. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.09.028. arXiv:2005.02188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan Kashif Aziz, Cheung Peter. Presence of mismatches between diagnostic PCR assays and coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 genome. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020;7(6) doi: 10.1098/rsos.200636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 genomes used in this analysis are available, upon free registration, from the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org/). Supporting Material presents a list of 54 commonly used diagnostic primers and probes and tables of mutation details on 54 diagnostic primers and probes. The acknowledgments of the SARS-COV-2 genomes are also given in the Supporting Material.