Abstract

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are routinely used for the delivery of macromolecules into live human cells. To enter the cytosolic space of cells, CPPs typically permeabilize the membrane of endosomes. In turn, several approaches have been developed to increase the endosomal membrane permeation activity of CPPs so as to improve delivery efficiencies. The endocytic pathway is however important in maintaining cellular homeostasis and understanding how endosomal permeation impacts cells is now critical to define the general utility of CPPs. Herein, we investigate how CPP-based delivery protocols affect the endocytic network. We detect that in some cases, cell penetration induces the activation of Chmp1b, Galectin-3, and TFEB, components of endosomal repair, organelle clearance, and biogenesis pathways, respectively. We also detect that cellular delivery modulates endocytosis and endocytic proteolysis. Remarkably, a multimeric analog of the prototypical CPP TAT permeabilizes endosomes efficiently without inducing membrane damage responses. These results challenge the notion that reagents that make endosomes leaky are generally toxic. Instead, our data indicates that it is possible to enter cells with minimal deleterious effects.

Keywords: membrane repair, endosomal escape, delivery agents, autophagy, biogenesis, cell recovery, TAT, cell-penetrating peptides

Introduction

Delivery vectors that transport macromolecules into live human cells are required for numerous applications in cell biology or biotechnologies. These reagents also have therapeutic potential as they may enable the development of biologics that modulate intracellular targets.1 Examples include cationic lipids or engineered viruses, both of which are optimized for the delivery of recombinant DNA.2, 3 The prospect of delivering a wider range of biomolecules with greater efficiencies or control has led to the development of new reagents, like cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs). CPPs can deliver DNA as well as peptides, proteins, and RNAs.4, 5 To enter cells, CPPs often accumulate inside endosomes after endocytic uptake and then escape from endosomes via processes that often remain unclear.6 Endosomal escape requires the disruption of endosomal membranes so as to allow the egress of delivered cargos into the cytosolic space of cells. In principle, the number of macromolecules that a delivery reagent can transport into the cytosol of a cell is proportional to the number of endosomal organelles permeabilized, and to the extent by which the membrane of these organelles is destabilized. Given that endocytic organelles are important to a variety of cellular processes, the disruption of the integrity of their membranes by delivery agents is expected to have various deleterious effects.7 This raises questions of whether efficient delivery reagents are necessarily harmful or toxic, and consequently, of whether there is a limit to how much material can be delivered into cells. Recently, several reports have highlighted how lysosomotropic agents, transfection reagents, particulate debris and pathogens induce membrane repair pathways upon disruption of endosomal membranes.8–13 These pathways can protect cells from the harmful consequences of membrane damage and help them reestablish homeostasis.14 Interestingly, by continually counteracting the damage performed by membrane-disrupting species, these responses may also inhibit the translocation of endocytosed toxins or pathogens.15

Herein, we investigate CPP-based delivery agents and establish their impact on the endocytic pathway. Our motivation for this study was three-fold. First, we aimed to examine whether membrane damage responses inhibit the cytosolic translocation of CPPs or mask some of their potentially deleterious effects. Second, the triggering of endosomal membrane damage responses is used as an assay to screen and identify endosomolytic delivery agents from chemical libraries.16 This type of proxy assay could in principle facilitate the development of improved CPPs. However, the correlation between membrane damage and cytosolic egress of cargos has not been clearly established, potentially leading to misleading results. Finally, understanding the impact that cell penetration has on cells is critically important to define the applications that are adequate when using delivery approaches. For example, the delivery of transcription factors for the reprogramming of stem cells, as well as the delivery of gene-editing complexes, is useful and controllable as long as the delivery process itself does not cause major transcriptional responses in manipulated cells.17–19 Similarly, using delivered probes to monitor cellular processes is only meaningful if cellular homeostasis is not disrupted by the delivery itself. In this context, our goal was to determine how cells respond to the disruption of endosomal membranes during CPP-based delivery protocols and establish how cells recover from this process. We exploit the fact that several CPP-based reagents have recently shown a broad range of endosomal escape activities, thereby giving for the first time the opportunity to establish a spectrum of possible responses.20–22

Results

Reagents used and experimental design.

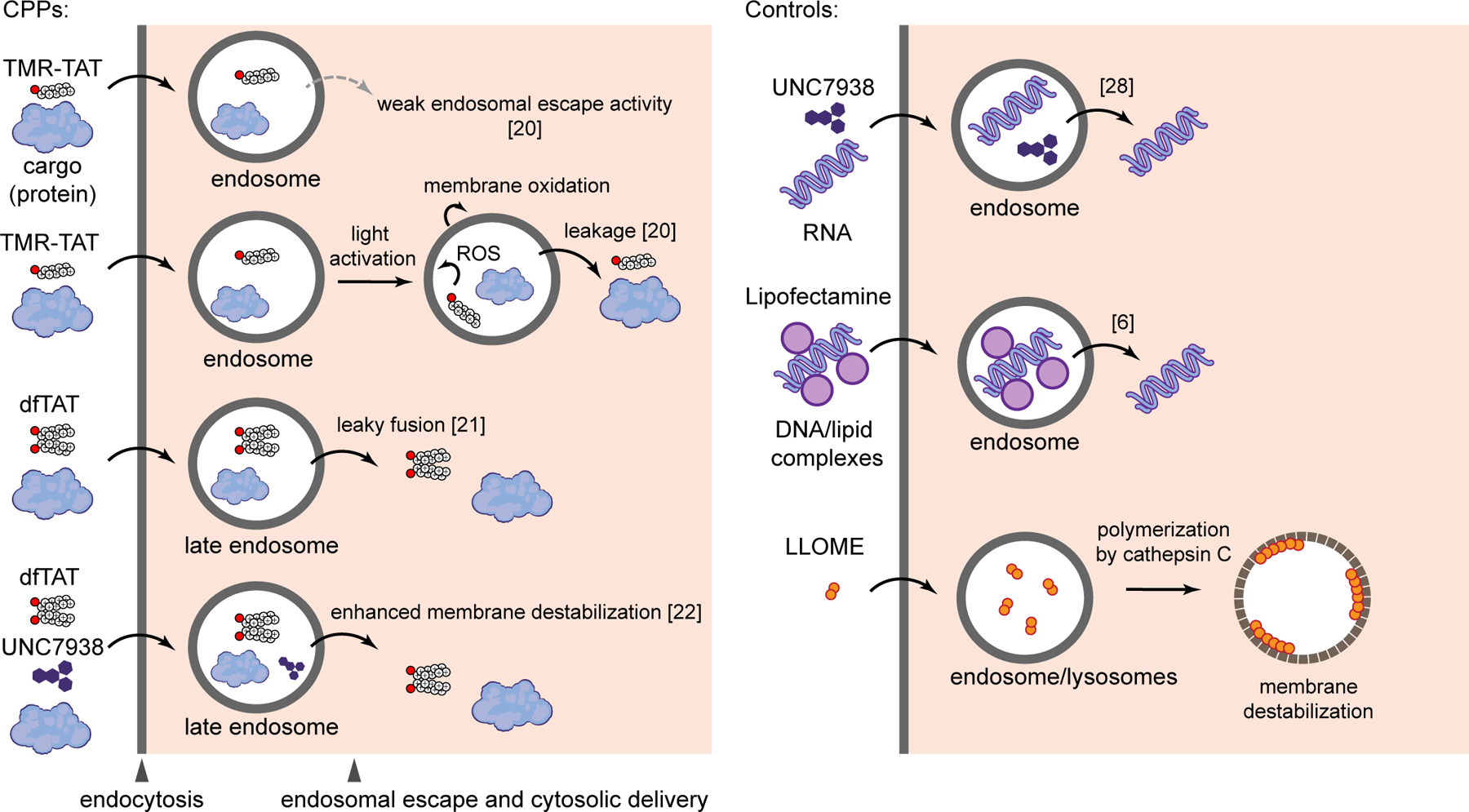

To establish the interplay between delivery efficiency, endosomal escape, and cellular responses to membrane damage, we chose a subset of delivery agents related to the prototypical CPP HIV TAT peptide (Figures 1 and S1). TAT is a commonly used CPP endocytosed by cells at low micromolar incubation concentrations.23 Due to its relatively poor endosomal escape activity, TAT remains mostly trapped inside endosomes.24 We therefore expect that this peptide would represent a CPP with low membrane damage activity. Labeling of TAT with the fluorophore tetramethylrhodamine permits microscopy visualization of the peptide but also confers the TMR-TAT conjugate with a photolytic activity.20 In particular, upon irradiation with high intensity visible light, the fluorophore moiety produces reactive oxygen species (ROS). In turn, the TAT moiety targets the TMR and the generated ROS to endosomal membranes. Lipids in endosomal membranes are oxidized and endosomes subsequently rupture, thereby releasing their content. This light-induced activity can be exploited to improve cellular delivery efficiencies, as described in the strategy known as Photo Chemical Internalization (PCI).25 In this study, we envisioned that light would provide a useful trigger to induce endosomal membrane damage in a time-controlled manner.

Figure 1.

CPP-based cytosolic delivery approaches and endosome-disrupting reagents used in this study.

An alternative way to enhance the endosomal escape of TAT consists of conjugating multiple copies of this peptide to create constructs presenting a high local concentration of arginine residues. A reagent that follows this strategy is the disulfide bonded dimer dfTAT.21 dfTAT escapes from endosomes efficiently and localizes in the cytosol and nucleus of cells.26 dfTAT promotes the cytosolic delivery of a wide variety of molecules, from small organic molecules and peptides to large proteins (25–150 kDa) and nanoparticles (100 nm in diameter).21, 27 The successful cytosolic delivery of large cargos implies that substantial membrane disruptions occur. In this study, we therefore expect dfTAT to serve as a model for CPPs that disrupt and modify endosomal membranes extensively.

UNC7938 is a small molecule that can deliver nucleic acid payloads into cells in vitro and in vivo.28 UNC7938 also enhances the endosomal escape and cytosolic delivery of TAT-like CPPs. For instance, while the effect of UNC7938 is not readily noticeable when dfTAT enters cells effectively on its own (e.g. at 5 μM incubation), the small molecule greatly improves the cell penetration of the peptide under conditions where the peptide alone would otherwise remain trapped inside endosomes (e.g. at 1 μM incubation). Overall, UNC7938 primes the endosomal membrane for CPP-mediated leakage and this can be exploited to achieve delivery of nucleic acid and protein cargos under conditions where CPPs alone fail.22 Given the boost in endosomal escape activity provided by UNC7938, we envision that this molecule may increase the damage of endosomal membranes and potentially trigger cellular responses that CPPs alone may not elicit. Finally, Lipofectamine and L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester (LLOME) were chosen as controls. Lipofectamine is a broadly used transfection agent that differs from CPPs in structure, charge, and type of cargo delivered. LLOME is endocytosed by cells and converted into a membranolytic polymer by hydrolases present in the endocytic pathway.29 LLOME is not a delivery agent but this molecule is generally used as a model for the study of endosomal membrane repair, and will be used herein as a positive control.8, 9 Cell incubation times and protocols, which vary based on the experimental design, are summarized for all assays in supplemental information (Figure S2).

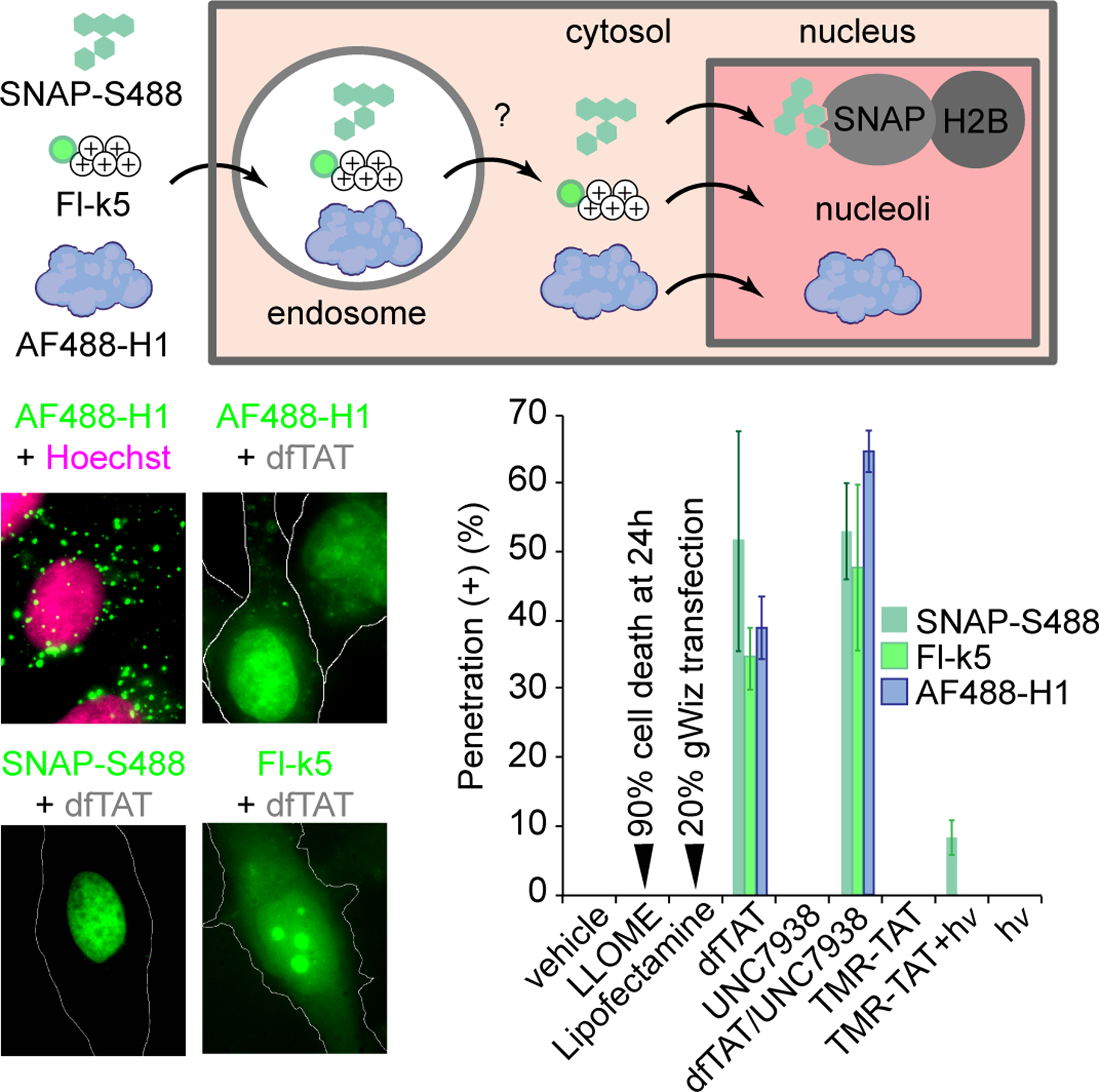

CPP-induced endosomal membrane leakage

Based on the literature, the delivery reagents chosen for this study are expected to induce endosomal membrane leakage with various efficiencies. However, the quantification of delivery efficiencies often uses a wide variety of cargos and indirect assays, making side-by-side comparisons difficult. In order to directly establish the endosomal membrane permeabilization activities of the reagents used herein, we chose several assays that measure the escape of molecules from the lumen of endosomes. We first focused on detecting the endosomal escape of H+ and Ca2+, as these ions are more concentrated inside endosomes than in the cytosol of cells. We found that dfTAT and dfTAT/UNC7938 may partially release both ions (Figure S3). However, slow release kinetics and transport mechanisms that reestablish homeostasis may mask some of these effects. To circumvent these issues, SNAP-S488, Fl-k5, and AF488-H1 were used as reporters of endosomal release. SNAP-S488 (842 Da) is a membrane impermeable small fluorophore, Fl-k5 (1016 Da) is a penta-lysine peptide that is protease-resistant, and AF488-H1 (21 kDa) is the labeled Histone 1 protein. These probes accumulate inside endosomes along with delivery agents, escape endosomes upon sufficient leakage, and accumulate within the nuclei of cells (Figure 2).21 Probes were co-incubated with delivery agents and the intracellular distribution of the probes was quantified based on the number of cells displaying nuclear fluorescence. In the case of LLOME, Lipofectamine, TMR-TAT, and UNC7938, fluorescence microscopy showed endosomal entrapment of probes, suggesting that, if endosomal leakage happens, it is below the detection limit of our assays. The photolytic activity of TMR-TAT in the presence of lights shows a redistribution of Fl-k5. The efficiency of this process is low because the power of the light source was limited to avoid cytotoxic effects. In contrast, dfTAT or the dfTAT/UNC7938 cocktail redistributes the three probes to the cytosol and nucleus in a majority of cells in a culture. This is also observed when endosomes are preloaded with probes, confirming that endosomal entrapment precedes endosomal escape (Figure S4). Notably, cell penetration of dfTAT or dfTAT/UNC7938 was non-toxic to cells (unlike LLOME which leads to a delayed loss of viability, Figure S5)

Figure 2.

Reagent-mediated leakage of fluorescent probes trapped in endosomes. SNAP-Surface 488, Fl-k5 and AF488-H1 were incubated with delivery reagents for 1h and their cytosolic egress was quantified by counting the number of cells displaying nuclear or nucleolar staining by the probes. For all experiments, the data provided are the mean of triplicate experiments (approximately 500 cells quantified per condition for each experiment).

Triggering of endosomal membrane damage and repair responses

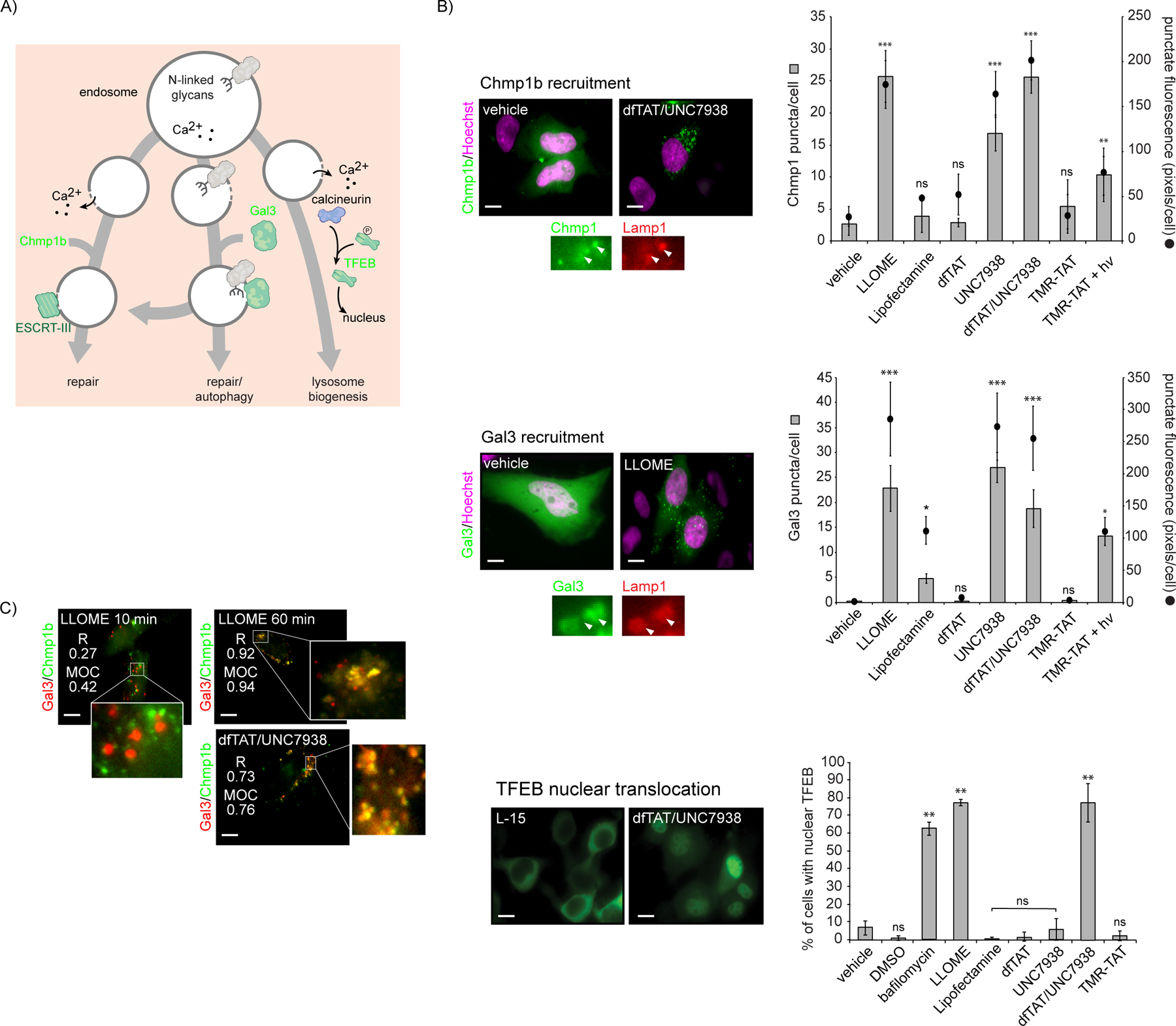

We next evaluated whether cells engage in endosomal membrane damage responses. These responses include repair of membrane defects, clearance of damaged organelles by autophagy, and replacement of organelles by de novo biogenesis (Figure 3A). Chmp proteins bind to permeabilized membranes following endosomal Ca2+ leakage into the cytosol, implicating the ESCRT III complex in membrane repair processes.9, 30 Therefore, we chose Chmp1b as a marker of endosomal membrane repair and as a probe for relatively small membrane disruptions.9 Upon organelle damage, luminal β-galactosides become exposed to cytosolic components (this presumably requires large membrane disruptions). Cytosolic Galectin-3 (Gal3) binds to these exposed β-galactosides, thereby initiating autophagy.31 Recruitment of Gal3 to endosomes is therefore a marker for the degradation of these organelles. Finally, the transcription factor EB (TFEB) regulates the induction of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy.32, 33 TFEB activation involves endosomal Ca2+ efflux, activation of the phosphatase calcineurin, dephosphorylation of TFEB, and subsequent translocation of the transcription factor to the nucleus.34 Overall, the endosomal recruitment of Chmp1b and Gal3 and the nuclear accumulation of TFEB upon cell treatment with delivery protocols were monitored by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3B).The average number of Chmp1b and Gal3 puncta per cell was counted. In addition, because puncta can potentially coalesce to form large aggregates, the total number of pixels from puncta was quantified.

Figure 3.

Triggering of endosomal membrane damage responses by CPPs. A) Scheme highlighting the activity of probes Chmp1b, Gal3, and TFEB as reporters of membrane repair, autophagy, and lysosomal biogenesis, respectively. B) Cells were incubated with delivery reagents, washed and imaged. Representative fluorescence of images treated and untreated cells are shown (scale bars: x100: 10 μm). Images are pseudocolored green for Chmp1b, Gal3 and TFEB, and magenta for Hoechst. To measure the recruitment of Chmp1b and Gal3 to damaged endosomes, the number of fluorescent puncta per cell, as well as the sum of pixels from fluorescent puncta were quantified. Colocalization with the late endosome/lysosome marker Lamp1 was used to establish that the puncta correspond to endocytic organelles. To assess whether lysosomal biogenesis is induced, the percentage of cells displaying TFEB nuclear accumulation was determined. The data shown represent means determined from biological duplicates. (C) Colocalization analysis of Gal3 and Chmp1b upon treatment with LLOME or dfTAT/UNC7938. Pearson’s colocalization coefficient (R) and Manders’ overlap coefficient (MOC) were determined for each condition. Fluorescence images are pseudocolored red for Gal3 and green for Chmp1b.

The number of Chmp1b puncta after Lipofectamine, dfTAT and TMR-TAT treatments was similar to that detected in untreated cells (Figure 3B). Similarly, the cytosolic distribution of Gal3 was maintained for these conditions, with only a moderate increase in puncta for Lipofectamine. In contrast, LLOME, UNC7938, dfTAT/UNC7938, and TMR-TAT + hv trigger the recruitment of Chmp1b and Gal3 to damaged membranes. These results were reproduced with Chmp4b and Gal8, additional markers of membrane repair and autophagy (Figure S6). Both Chmp1b and Gal3 colocalized with LAMP1, confirming that both proteins are recruited to damaged late endosomes/lysosomes (Figure 3B). The Chmp1b and Gal3 puncta are distinct after 10 min of LLOME treatment but tend to colocalize after 1h. This suggests an overlap between membrane repair and autophagy pathways, as previously suggested.35 Strikingly, only LLOME and dfTAT/UNC7938 triggered the nuclear translocation of TFEB (bafilomycin being a positive control).

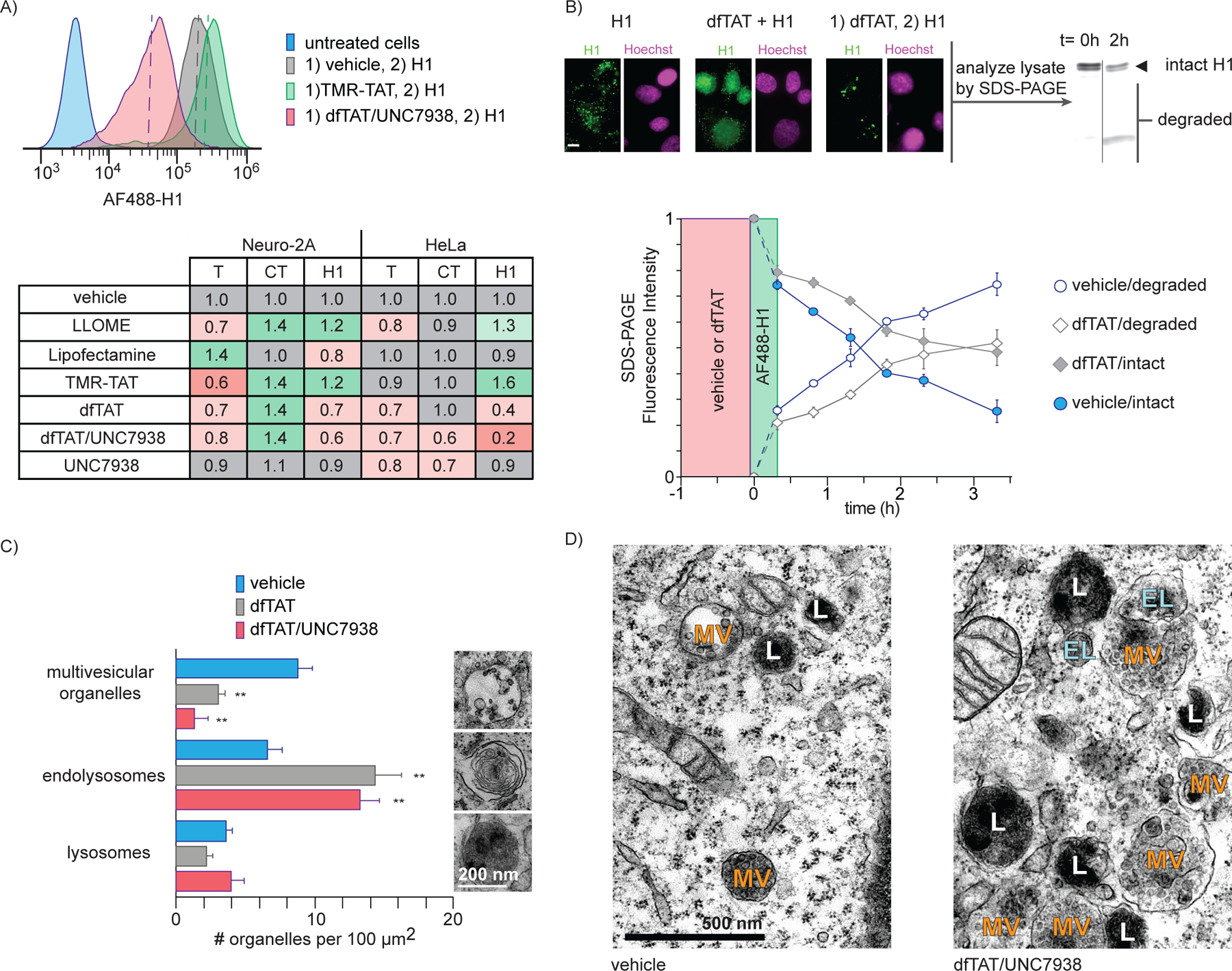

CPP-mediated disruption of endocytic uptake and endosomal degradation

If delivery agents disrupt the membrane of endosomes, one can envision how this may then alter the trafficking of these organelles, and as a result, alter the endocytic pathway as a whole. Based on this idea, we next examined how delivery agents impacted endocytic uptake, an initial step in the maturation of the pathway. In order to quantify endocytic uptake, cells were treated with transferrin (T), the cholera toxin (CT), and histone H1, each protein labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488). Our results indicated that these probes likely use multiple endocytic uptake mechanisms under the conditions used (Figure S7). We therefore use them in this study as overlapping yet distinct probes to survey the overall effect of CPPs on endocytic uptake. Cells were incubated with probes after treatment with delivery agents or vehicle. Localization of the probes within endosomes was confirmed by microscopy and colocalization with endosomal markers. Uptake was quantified by measuring the AF488 fluorescence intensity associated with each cell population by flow cytometry. In particular, the AF488 intensities that correspond to 50% population thresholds were used for comparison purposes (Figure 4A). With the exception of Lipofectamine, all reagents led to an inhibition of transferrin uptake in both Neuro-2a and HeLa cell lines. In contrast, the uptake of the cholera toxin was either unaffected or increased by most reagents. One exception is the cocktail dfTAT/UNC7938, which, surprisingly, caused an enhancement of uptake in one cell line, but a reduction in another. The uptake of H1 was stimulated by LLOME and TMR-TAT. In contrast, it is inhibited by dfTAT and dfTAT/UNC7938, the latter condition having the most severe effect. Interestingly, UNC7938 alone had a minimal impact on cellular uptake.

Figure 4.

Impact of CPPs on endocytic uptake and endosomal degradation post incubation. A) Cellular uptake of endocytic probes after treatment with delivery agents. Cells were treated with CPPs for their respective incubation times, washed, and incubated with AF488-labelled probes for endocytic uptake, namely transferrin (T), cholera toxin subunit B (CT), and Histone H1 (H1). The uptake of each probe was quantified by flow cytometry. Four representative flow cytometry traces of the uptake of AF488-H1 are shown. The AF488 intensities that corresponded to a 50% threshold (dotted lines) was determined for each condition. The fold change in uptake for each condition as compared to the vehicle/probe control is shown. The values reported represent the mean of biological duplicates. The standard deviations (not shown) are 0.2 or less. (B) Impact of dfTAT on endosomal proteolysis. The degradation of the probe AF488-H1 endocytosed by cells was monitored over time by quantifying the formation of fluorescent protein fragments by SDS-PAGE. The degradation rate of AF488-H1 endocytosed was compared for cells preincubated for 1h with either vehicle or dfTAT. Each plotted value represents the mean fluorescence intensity of intact or degraded AF488-H1 from biological duplicates. Fluorescence microscopy was used to compare the localization of H1 incubated with cells during or after incubation with dfTAT. Images are pseudocolored green for AF488-H1 and magenta for Hoechst (scale 10 μm). (C) Transmission electron microscopy imaging of cells treated with dfTAT or dfTAT/UNC7938. The number of multivesicular bodies/late endosomes, endolysosomes, and lysosomes were counted from the cross sections of 5 cells. (D) Representative TEM images of cells treated with vehicle (left) and dfTAT/UNC7938-treated (right). Organelles are designated as multivesicular bodies/late endosomes (MV), endolysosomes (EL), lysosomes (L) based on their morphologies.

Endolysosomal proteolytic degradation is a characteristic function of the endocytic pathway. To assess how it is impacted by the permeation of endosomes, cells were either pretreated with vehicle (L-15) or with dfTAT for one hour (Figure 4B). Cells were subsequently incubated with AF488-H1 and the presence of fluorescent degradation products in cell lysates was detected and quantified by SDS-PAGE. Fluorescence microscopy was used to establish that AF448-H1 is localized within endosomes during these experiments. Degradation may therefore originate from the extracellular milieu, prior to internalization, or from the endocytic pathway, after uptake. In cells treated with vehicle, approximately half of internalized H1 was degraded at the 2h time point. In contrast, the 50% degradation time point is reached at approximately 3.5h when cells are preincubated with dfTAT. Hence, dfTAT causes a delay in degradation kinetics but cells remain overall capable of degrading endocytosed proteins. This delay in degradation kinetics may be caused by a loss of endosomal proteases to the cytosol during dfTAT-mediated leakage. Additionally, dfTAT may render these pH-dependent proteases less active by possibly increasing the pH of endosomes (as noted in Figure S3).

In principle, the high membrane permeation activity of dfTAT and dfTAT/UNC7938 may deleteriously impact the endolysosomal network by changing the number of endocytic organelles present in a cell. To address this question, cells were examined by transmission electron microscopy. Endocytic organelles were counted as either multivesicular organelles (MV, e.g. early endosomes, late endosomes), endolysosomes (EL), or lysosomes (L) based on their distinct morphology.36 In both dfTAT and dfTAT/UNC7938 treated cells, the number of multivesicular organelles decreased while the number of endolysosomes increased (Figure 4C). These changes were approximately inversely proportional, indicating a possible conversion of multivesicular endosomes into endolysosomes upon cell penetration. Notably, dfTAT-treated cells were otherwise indistinguishable from untreated cells. In contrast, cells treated with dfTAT/UNC7938 displayed dense clusters of MV, EL, and L (Figure 4D).

Cellular recovery after endosomal escape and delivery.

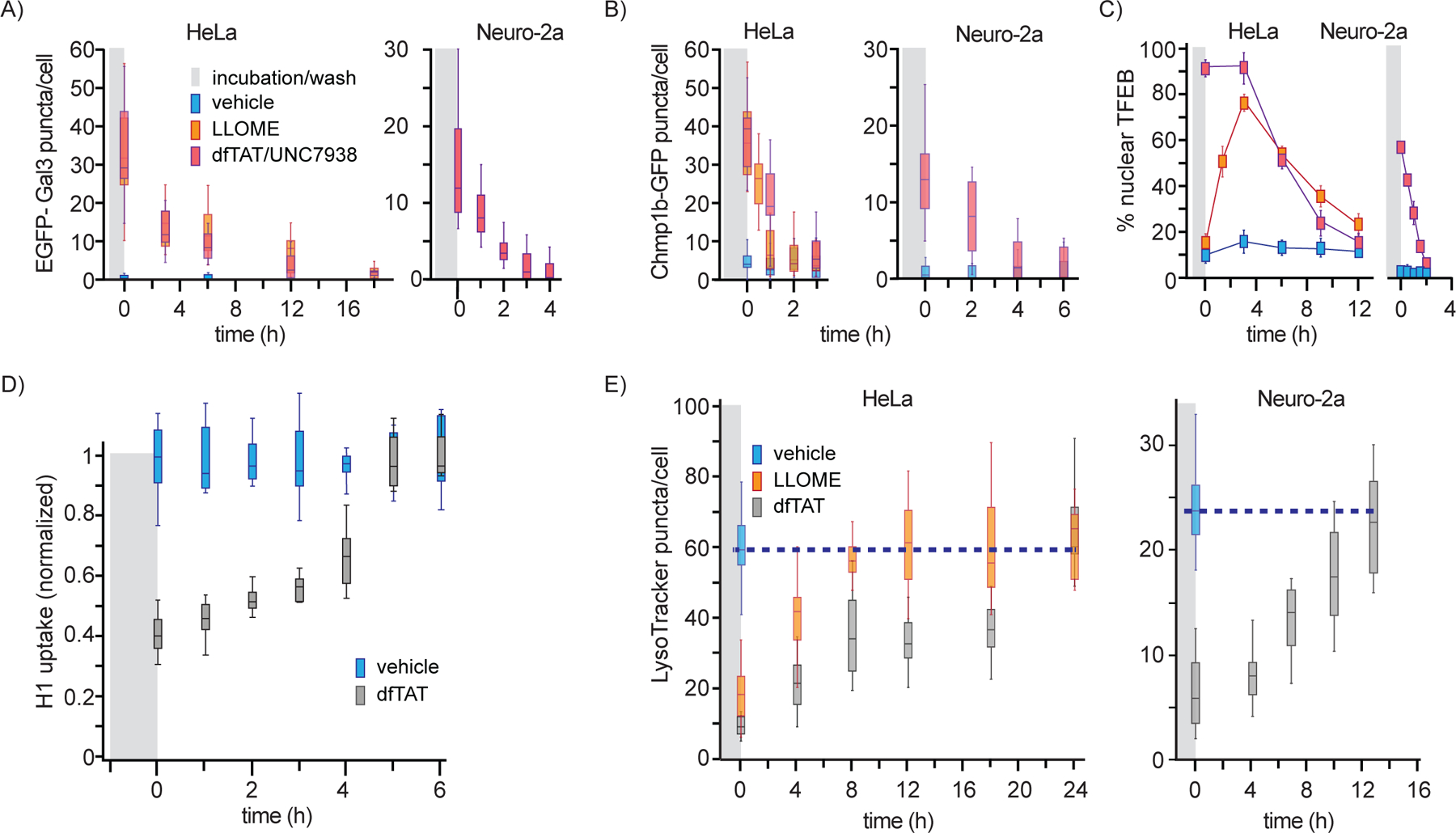

Once organelles are either repaired or targeted for degradation, Chmp1b, Gal3, and TFEB eventually return to their basal cytosolic distribution.9, 30, 37 Interested in establishing how quickly cells recover from a delivery protocol, we first chose to measure how rapidly Chmp1b and Gal3 puncta disappear from treated cells and how rapidly TFEB returns to a cytoplasmic localization (Figure 5A–C). Both HeLa and Neuro-2a cells were treated with dfTAT/UNC7938, the delivery protocol identified as the most disruptive in our previous experiments. LLOME was used as control when possible (LLOME did not trigger Chmp1b and Gal3 recruitment in Neuro-2a). Gal3 puncta were detected in HeLa cells for up to 18h while Chmp1b puncta were at basal levels in approximately 3h. Gal3 recovery was noticeably more rapid in Neuro-2a than in Hela. In contrast, Chmp1b recovery was comparatively delayed in Neuro-2a. The rates of recovery between LLOME and dfTAT/UNC7938 were similar, indicating that this process is relatively independent of the agent causing membrane damage. In the case of TFEB, the percentage of cells displaying a nuclear localization of the transcription factor first increased over time for LLOME while being already at its maximum for dfTAT/UNC7938 immediately after incubation. Notably, nuclear accumulation was steady or rising for 3h in both cases, indicative of a sustained signaling of membrane damage and activation of TFEB. Cells then returned to a cytoplasmic TFEB distribution after an additional 9h. As with Gal3 and Chmp1b, the rate of recovery was overall similar between LLOME and dfTAT/UNC7938, and slower in HeLa cells than in Neuro-2a. Of note, the recovery rates of Gal3 and TFEB were consistently similar, indicating a possible connection in how these responses are orchestrated.

Figure 5.

Recovery kinetics of membrane damage probes. (A) and (B) The number Gal3 or Chmp1b positive puncta per cell was quantified over time after LLOME or dfTAT/UNC7938 treatment. The data are represented as box and whiskers plots. (C) Percentage of cells displaying a nuclear localization of TFEB post LLOME or dfTAT/UNC7938 treatment. (D) Cellular recovery of AF488-H1 uptake after treatment with dfTAT for 1h. (E) Recovery of LysoTracker Green staining in cells were treated with LLOME or dfTAT. For all experiments, the data are obtained from biological triplicates.

We next monitored the recovery kinetics of endocytic uptake of H1 and LysoTracker staining of cells over time after dfTAT treatment (Figure 5D and E). In these experiments, cells were treated as in Figures S2 and 4. However, in this case, AF488-H1 or LysoTracker were added at increasing intervals after dfTAT treatment and cell washing. As observed before by flow cytometry, the uptake of H1 after dfTAT treatment was decreased by 60% when compared to untreated cells. Endocytic uptake increases progressively overtime, returning to normal levels in less than 5h. In comparison, the recovery of LysoTracker staining was substantially longer, requiring 8h for LLOME, and 12 to 24h for dfTAT in Neuro-2a and HeLa, respectively.

Discussion

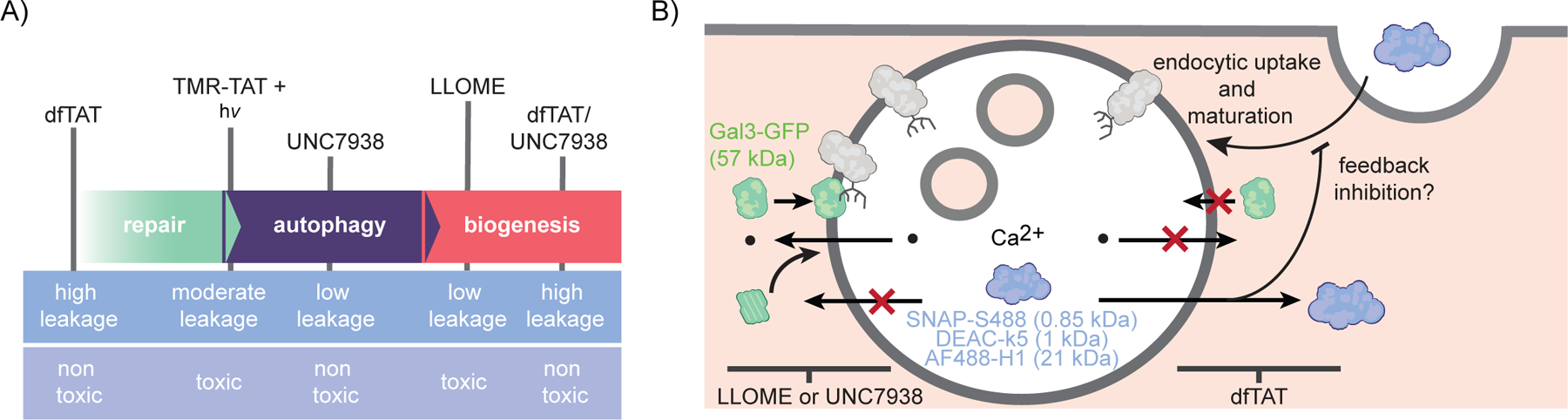

A necessary step in cellular delivery applications is the translocation of macromolecules across membranes. Our starting assumption was that, the higher the efficiency of translocation, the higher the membrane damage would be. The basic premise for this assumption lies in the fact that the translocation of macromolecules across a membrane barrier presumably requires a substantial disruption in the integrity of a bilayer. In particular, a reagent like dfTAT is capable of permeating the membrane of late endosomes very efficiently. It is efficient because the majority of macromolecules (>90%) initially entrapped in these organelles can reach the cytosol.21 Membrane permeation also appears to accommodate the translocation of large species, including nanoparticles that have a diameter of 50–100 nm.27 We can therefore imagine that dfTAT generates large pores or tears in the membrane and that these membrane disruptions should be detected by repair or degradation pathway. However, based on our results, it is not the case. In particular, dfTAT did not induce the recruitment of Chmp1b or Gal3, nor did it cause the activation of TFEB. Conversely, UNC7938, a reagent that yields endosomal escape with an efficiency below the detection level of our assays, causes Chmp1b and Gal3 responses similar to LLOME, a compound that permeabilizes lysosomes. Moreover, the combination of dfTAT/UNC7938 shows the high levels of endosomal permeation achieved with dfTAT, but displays the Chmp1b and Gal3 responses obtained with UNC7938 alone. These results indicate that, surprisingly, there is no correlation between endosomal escape and membrane repair or clearance responses (Figure 6). In turn, these results establish that high levels of endosomal membrane permeation and cytosolic release can be achieved without necessarily inducing membrane repair, organelle autophagy, or lysosomal biogenesis.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the membrane responses induced by CPPs in this study. (A) Endosomal leakage and toxicity associated with each condition are shown to highlight the lack or correlation between cell penetration by endosomal escape and endosomal membrane damage. Extent of membrane damage is indicated by arrows showing the progression of cellular responses in order of expected severity. B) LLOME and UNC7938 generate membrane disruptions that trigger recruitment of Gal3 and components of the ESCRT-III complex, but that fail to promote the endosomal escape of the SNAP-S488, DEAC-k5, and AF488-H1 probes. In contrast, dfTAT releases these probes into the cytosol of cells effectively without inducing Gal3/ESCRT-III membrane repair pathways.

In the absence of precise molecular details on how membrane permeation takes place, it is difficult to interpret how large macromolecular cargo can exit endosomes with the help of dfTAT without eliciting Chmp1b/Gal3 responses. A possible explanation for this phenomenon may relate to the rate at which permeation take place. For instance, as shown in Figure S3, dfTAT enters the cytosol of cells progressively over a period of 1h. This rate is in part consistent with the time that it may take for the CPP to reach late endosomes. Once in these organelles, it is however possible that dfTAT permeates membranes in transient bursts. Transient membrane leakage would let a small amount of cargo enter the cytosolic space at any given time and it may take several minutes before endosomes lose their content. Concomitantly, calcium could exit endosomes during these short permeation bursts. However, because of the presence of calcium exporters in the cell, the local influx of calcium could be rapidly dissipated before any downstream membrane damage responses are initiated. In contrast, UNC7938 could cause a sustained release of calcium. In particular, given that we were not able to detect cytosolic influx of calcium in neither the dfTAT or UNC7938 conditions, the concentration of calcium released by UNC7938 may not be higher than in the case of dfTAT. However, the continuous release of this ion could be sufficient to initiate calcium-dependent responses. Additionally, it is important to note the sites of membrane leakage attributed to dfTAT are late endosomes.38 These organelles contain intraluminal vesicles rich in the lipid bis(monoacylglycerol) phosphate (BMP) and BMP-containing bilayers are prone to the leakage induced by TAT-like CPPs.38, 39 It is therefore conceivable that membrane translocation events involve these vesicles. Macromolecular cargos delivered by dfTAT could for instance enter the lumen of these vesicles and reach the cytosol after back fusion of these vesicles to the limiting membrane of late endosomes. The bilayer permeation would however take place inside the organelle, hidden from membrane repair and degradation machinery contained in the cytoplasm. Alternatively, Pei and co-workers have proposed a vesicle budding and collapse mechanism for the endosomal escape of arginine-rich peptides.40 In this model, CPPs induce the formation of vesicles that bud from endosomes. These vesicles subsequently rupture and release their contents into the cytosol. Here again, it is possible that this process could evade membrane damage responses.

Regardless of the mechanistic reasons underlying why UNC7938 triggers membrane damage responses while dfTAT does not, it is clear that our results point to the fact that these delivery agents may be best adapted for different applications. For instance, we have already shown that dfTAT-induced endosomal permeation leads to a minor response in gene expression. Specifically, out of 47,000 mRNA transcript surveyed, dfTAT causes the dysregulation of 11 genes immediately following the delivery protocol and only 2 genes 24h after.21 In contrast, Lipofectamine induces the dysregulation of more than 1000 genes.41 dfTAT does affect LysoTracker staining, endocytic uptake and endosomal protein degradation. However, the relatively weak membrane damage responses detected with this reagent further suggest that dfTAT-mediated delivery is relatively benign to the cells. It may therefore be adequate for cell biology applications that involve investigating the function of a delivered cargo. This is because such studies could be performed in a cellular background that is not dramatically different from that of untreated cells. In contrast, the combination of dfTAT/UNC7938 allows successful delivery for cargos and culture conditions that do not work with dfTAT alone.22 This cocktail clearly induces more pronounced membrane damage responses. Based on the TFEB response and the nuclear retention of this transcription factor, it presumably also leads to a gene-expression response.33 This delivery protocol can therefore change the characteristics of a cell and using this approach may consequently be less amenable to cell biology studies. Notably, the membrane-damage responses detected dissipate and cells recover without loss of viability. We therefore propose that this delivery cocktail may be adequate for applications that are compatible with cell recovery, such as gene editing and cell reprogramming. It is important to note that our results however apply to delivery protocols using delivery reagents and payloads that are not covalently linked. It is possible that attaching large cargos to the CPPs used in this study may change their interactions with membranes and subsequently modulate membrane damage response pathways in different ways. Further work is needed to establish this relationship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by award R01GM110137 (J.-P.P.) from the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and grant RP190655 from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. We thank T. Yoshimori (Osaka University) for pEGFP-hGal3, F. Randow (University of Cambridge) for YFP-Gal8, J. Jaiswal (George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences) for Chmp1b-GFP and Chmp4b-YFP, J. Lippincott-Schwartz (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) for Cerulean-LAMP1, E. Dell’Angelica (University of California, Los Angeles) for LAMP1-mGFP, C. Rosenmund for pCMV-lyso-pHluorin (Berlin University of Medicine), S. Ferguson for pEGFP-N1-TFEB (Yale School of Medicine), and I.R. Correa (New England Biolabs) for pSNAP-H2B. We also thank S. Vitha and R. Littleton of the Microscopy and Imaging Center at Texas A&M University for transmission electron microscopy sample preparation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available:

This material includes the method section and supplementary figures and is available free of charge via the Internet.

References

- [1].Stewart MP, Langer R, and Jensen KF (2018) Intracellular Delivery by Membrane Disruption: Mechanisms, Strategies, and Concepts, Chem. Rev 118, 7409–7531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wasungu L, and Hoekstra D (2006) Cationic lipids, lipoplexes and intracellular delivery of genes, J. Controlled Release 116, 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Warnock JN, Daigre C, and Al-Rubeai M (2011) Introduction to viral vectors, Methods Mol. Biol 737, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lonn P, and Dowdy SF (2015) Cationic PTD/CPP-mediated macromolecular delivery: charging into the cell, Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 12, 1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Eguchi A, and Dowdy SF (2009) siRNA delivery using peptide transduction domains, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 30, 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brock DJ, Kondow-McConaghy HM, Hager EC, and Pellois JP (2019) Endosomal Escape and Cytosolic Penetration of Macromolecules Mediated by Synthetic Delivery Agents, Bioconjugate Chem. 30, 293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang F, Gomez-Sintes R, and Boya P (2018) Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death, Traffic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maejima I, Takahashi A, Omori H, Kimura T, Takabatake Y, Saitoh T, Yamamoto A, Hamasaki M, Noda T, Isaka Y, and Yoshimori T (2013) Autophagy sequesters damaged lysosomes to control lysosomal biogenesis and kidney injury, EMBO J. 32, 2336–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Skowyra ML, Schlesinger PH, Naismith TV, and Hanson PI (2018) Triggered recruitment of ESCRT machinery promotes endolysosomal repair, Science 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen X, Khambu B, Zhang H, Gao W, Li M, Chen X, Yoshimori T, and Yin XM (2014) Autophagy induced by calcium phosphate precipitates targets damaged endosomes, J. Biol. Chem 289, 11162–11174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wittrup A, Ai A, Liu X, Hamar P, Trifonova R, Charisse K, Manoharan M, Kirchhausen T, and Lieberman J (2015) Visualizing lipid-formulated siRNA release from endosomes and target gene knockdown, Nat. Biotechnol 33, 870–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Scharf B, Clement CC, Wu XX, Morozova K, Zanolini D, Follenzi A, Larocca JN, Levon K, Sutterwala FS, Rand J, Cobelli N, Purdue E, Hajjar KA, and Santambrogio L (2012) Annexin A2 binds to endosomes following organelle destabilization by particulate wear debris, Nat. Commun 3, 755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thurston TL, Wandel MP, von Muhlinen N, Foeglein A, and Randow F (2012) Galectin 8 targets damaged vesicles for autophagy to defend cells against bacterial invasion, Nature 482, 414–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Papadopoulos C, and Meyer H (2017) Detection and Clearance of Damaged Lysosomes by the Endo-Lysosomal Damage Response and Lysophagy, Curr. Biol 27, R1330–r1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huang J, and Brumell JH (2014) Bacteria-autophagy interplay: a battle for survival, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 12, 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kilchrist KV, Dimobi SC, Jackson MA, Evans BC, Werfel TA, Dailing EA, Bedingfield SK, Kelly IB, and Duvall CL (2019) Gal8 Visualization of Endosome Disruption Predicts Carrier-Mediated Biologic Drug Intracellular Bioavailability, ACS Nano 13, 1136–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zuris JA, Thompson DB, Shu Y, Guilinger JP, Bessen JL, Hu JH, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Chen ZY, and Liu DR (2015) Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo, Nat. Biotechnol 33, 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ramakrishna S, Kwaku Dad AB, Beloor J, Gopalappa R, Lee SK, and Kim H (2014) Gene disruption by cell-penetrating peptide-mediated delivery of Cas9 protein and guide RNA, Genome Res. 24, 1020–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, Ko S, Yang E, Cha KY, Lanza R, and Kim KS (2009) Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins, Cell Stem Cell 4, 472–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Muthukrishnan N, Johnson GA, Lim J, Simanek EE, and Pellois JP (2012) TAT-mediated photochemical internalization results in cell killing by causing the release of calcium into the cytosol of cells, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 1734–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Erazo-Oliveras A, Najjar K, Dayani L, Wang T-Y, Johnson GA, and Pellois J-P (2014) Protein delivery into live cells by incubation with an endosomolytic agent, Nat. Methods 11, 861–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Allen J, Najjar K, Erazo-Oliveras A, Kondow-McConaghy HM, Brock DJ, Graham K, Hager EC, Marschall ALJ, Dubel S, Juliano RL, and Pellois JP (2019) Cytosolic Delivery of Macromolecules in Live Human Cells Using the Combined Endosomal Escape Activities of a Small Molecule and Cell Penetrating Peptides, ACS Chem. Biol 14, 2641–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kaplan IM, Wadia JS, and Dowdy SF (2005) Cationic TAT peptide transduction domain enters cells by macropinocytosis, J. Controlled Release 102, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Erazo-Oliveras A, Muthukrishnan N, Baker R, Wang TY, and Pellois JP (2012) Improving the endosomal escape of cell-penetrating peptides and their cargos: strategies and challenges, Pharmaceuticals 5, 1177–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Berg K, Selbo PK, Prasmickaite L, Tjelle TE, Sandvig K, Moan J, Gaudernack G, Fodstad O, Kjolsrud S, Anholt H, Rodal GH, Rodal SK, and Hogset A (1999) Photochemical internalization: a novel technology for delivery of macromolecules into cytosol, Cancer Res. 59, 1180–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lee YJ, Erazo-Oliveras A, and Pellois JP (2010) Delivery of macromolecules into live cells by simple co-incubation with a peptide, Chembiochem 11, 325–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lian X, Erazo-Oliveras A, Pellois JP, and Zhou HC (2017) High efficiency and long-term intracellular activity of an enzymatic nanofactory based on metal-organic frameworks, Nat. Commun 8, 2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yang B, Ming X, Cao C, Laing B, Yuan A, Porter MA, Hull-Ryde EA, Maddry J, Suto M, Janzen WP, and Juliano RL (2015) High-throughput screening identifies small molecules that enhance the pharmacological effects of oligonucleotides, Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1987–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Thiele DL, and Lipsky PE (1990) Mechanism of L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester-mediated killing of cytotoxic lymphocytes: dependence on a lysosomal thiol protease, dipeptidyl peptidase I, that is enriched in these cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 87, 83–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Radulovic M, Schink KO, Wenzel EM, Nahse V, Bongiovanni A, Lafont F, and Stenmark H (2018) ESCRT-mediated lysosome repair precedes lysophagy and promotes cell survival, EMBO J. 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Paz I, Sachse M, Dupont N, Mounier J, Cederfur C, Enninga J, Leffler H, Poirier F, Prevost MC, Lafont F, and Sansonetti P (2010) Galectin-3, a marker for vacuole lysis by invasive pathogens, Cell. Microbiol 12, 530–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, Garcia Arencibia M, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Erdin SU, Huynh T, Medina D, Colella P, Sardiello M, Rubinsztein DC, and Ballabio A (2011) TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis, Science 332, 1429–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, Di Malta C, Donaudy F, Embrione V, Polishchuk RS, Banfi S, Parenti G, Cattaneo E, and Ballabio A (2009) A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function, Science 325, 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A, De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso C, Forrester A, Settembre C, Wang W, Gao Q, Xu H, Sandri M, Rizzuto R, De Matteis MA, and Ballabio A (2015) Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB, Nat. Cell Biol 17, 288–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jia J, Claude-Taupin A, Gu Y, Choi SW, Peters R, Bissa B, Mudd MH, Allers L, Pallikkuth S, Lidke KA, Salemi M, Phinney B, Mari M, Reggiori F, and Deretic V (2020) Galectin-3 Coordinates a Cellular System for Lysosomal Repair and Removal, Dev. Cell 52, 69–87.e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Huotari J, and Helenius A (2011) Endosome maturation, EMBO J. 30, 3481–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhitomirsky B, Yunaev A, Kreiserman R, Kaplan A, Stark M, and Assaraf YG (2018) Lysosomotropic drugs activate TFEB via lysosomal membrane fluidization and consequent inhibition of mTORC1 activity, Cell Death Discovery 9, 1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Erazo-Oliveras A, Najjar K, Truong D, Wang TY, Brock DJ, Prater AR, and Pellois JP (2016) The Late Endosome and Its Lipid BMP Act as Gateways for Efficient Cytosolic Access of the Delivery Agent dfTAT and Its Macromolecular Cargos, Cell Chem. Biol 23, 598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Brock DJ, Kustigian L, Jiang M, Graham K, Wang TY, Erazo-Oliveras A, Najjar K, Zhang J, Rye H, and Pellois JP (2018) Efficient cell delivery mediated by lipid-specific endosomal escape of supercharged branched peptides, Traffic 19, 421–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dougherty PG, Sahni A, and Pei D (2019) Understanding Cell Penetration of Cyclic Peptides, Chem. Rev 119, 10241–10287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jacobsen L, Calvin S, and Lobenhofer E (2009) Transcriptional effects of transfection: the potential for misinterpretation of gene expression data generated from transiently transfected cells, BioTechniques 47, 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.