Abstract

An epidemiological connection exists between Parkinson’s disease (PD) and melanoma. α-Synuclein (α-syn), the hallmark pathological amyloid observed in PD, is also elevated in melanoma, where its expression is inversely correlated with melanin content. We present a hypothesis that there is an amyloid link between α-syn and Pmel17 (premelanosomal protein), a functional amyloid that promotes melanogenesis. Using SK-MEL 28 human melanoma cells, we show that endogenous α-syn is present in melanosomes, the organelle where melanin polymerization occurs. Using in vitro cross-seeding experiments, we show that α-syn fibrils stimulate the aggregation of a Pmel17 fragment constituting the repeat domain (RPT), an amyloidogenic domain essential for fibril formation in melanosomes. The cross-seeded fibrils exhibited α-syn−like ultrastructural features that could be faithfully propagated over multiple generations. This cross-seeding was unidirectional, as RPT fibrils did not influence α-syn aggregation. These results support our hypothesis that α-syn, a pathogenic amyloid, modulates Pmel17 aggregation in the melanosome, defining a molecular link between PD and melanoma.

Keywords: functional amyloid, alpha-synuclein, aggregation, fibril

The primary pathological hallmark found in brains of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients is intracellular inclusions containing α-synuclein (α-syn) protein aggregates, formed by the conversion of intrinsically disordered α-syn monomers to β-sheet−rich fibrillar assemblies called amyloid (1). Compared to the general population, a significantly higher incidence of cancer of melanocytes (melanoma) is reported among PD patients (2–4). Biochemical analyses have detected α-syn in cultured melanoma cells and patient-derived tissues, suggesting that α-syn could be a molecular link between PD and melanoma (5–7). Notably, the levels of α-syn inversely correlate with the extent of pigmentation (i.e., melanin) (5, 8), leading to the prevailing hypothesis that α-syn disrupts the activities of enzymes involved in melanin biosynthesis (9). However, another crucial pigmentation gene is PMEL that expresses the premelanosomal protein (Pmel17), which forms amyloid fibrils that serve a functional role by sequestering toxic melanin intermediates and acting as a scaffold for melanin polymerization (10). We questioned whether an amyloid link exists between PD and melanoma, hypothesizing that α-syn modulates Pmel17 aggregation in the melanosome.

Results and Discussion

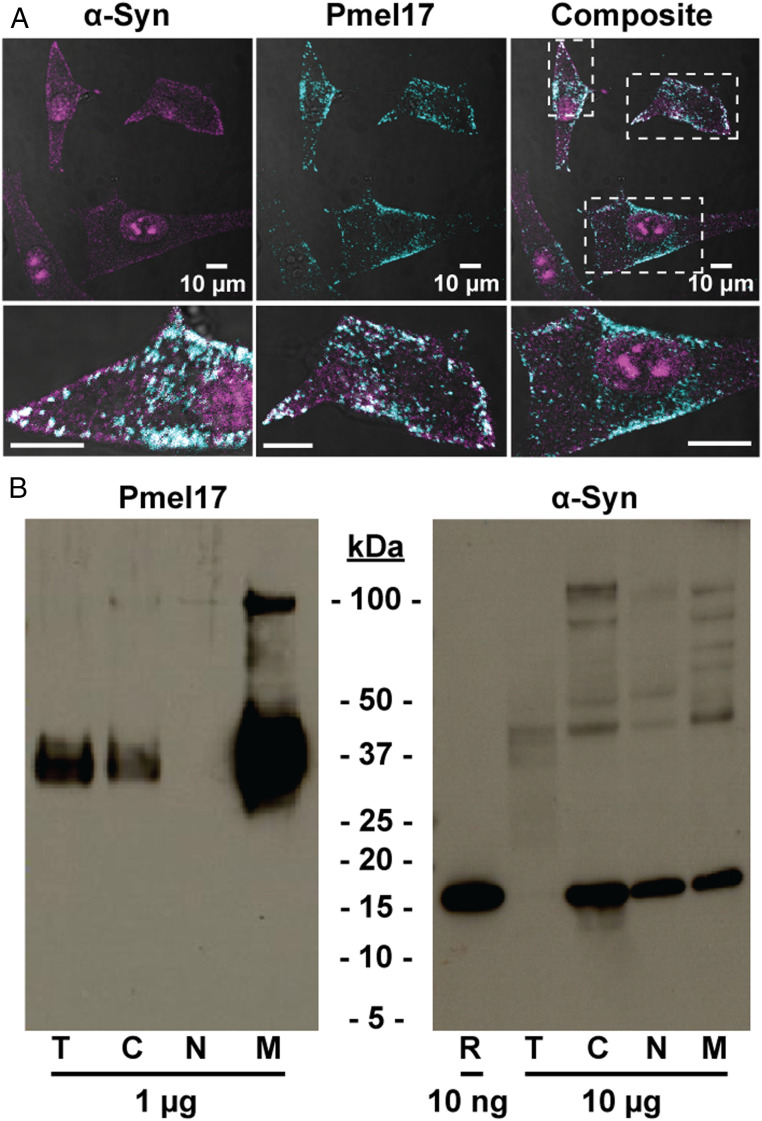

While several studies have shown the presence of α-syn in melanoma, it is not known whether α-syn localizes to the melanosome, the organelle where melanin biosynthesis occurs. Here, we assessed the localization of endogenous α-syn in hypopigmented SK-MEL 28 human melanoma cells. Using confocal immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1A), α-syn was detected in both the cytoplasm and nuclei of cells as previously reported (6). Using an antibody which recognizes an O-glycan within the repeat domain (RPT) (11), distinct puncta representing Pmel17 fibrils in melanosomes were observed (Fig. 1A). Colocalization was observed in cytoplasmic regions (Fig. 1A), where 47.2 ± 9.7% of Pmel17-positive pixels were also α-syn positive (n = 61 cells).

Fig. 1.

Endogenous α-syn is present in melanosomes of SK-MEL 28 human melanoma cells. (A) Confocal immunofluorescence images probed with anti−α-syn (magenta; EP1646Y) and anti-Pmel17 (cyan; HMB45) antibodies. Individual fluorescence channels were analyzed by defining a pixel threshold using the Otsu method, then using Boolean algebra to identify areas of cooccurrence (white). Dashed boxes represent areas shown below in the expanded views. (Scale bars, 10 µm.) (B) Immunoblots of total SK-MEL 28 cell lysate (T), or fractions enriched in C, N, M proteins probed with anti-Pmel17 (HMB45) or anti−α-syn (LB509) antibodies. Amount of protein loaded as indicated. Recombinant α-syn (R) is also shown for reference.

Next, subcellular fractionation and immunoblotting were performed as a complementary means of verifying compartmentalization in cellular extracts enriched in cytosolic (C), nuclear (N), or melanosomal (M) proteins (Fig. 1B). Enrichment of melanosomes was confirmed by strong immunodetection of Pmel17 in the melanosomal fraction (Fig. 1B), where the ∼37-kDa bands represent amyloidogenic Pmel17 fragments spanning RPT, produced by normal processing events (11). α-Syn was seen in cytoplasmic, nuclear, and melanosomal fractions as a ∼15-kDa band (Fig. 1B), consistent with the size of monomeric α-syn. Both immunofluorescence and immunoblotting experiments substantiated that α-syn is found in melanosomes, the organelle where melanin is synthesized.

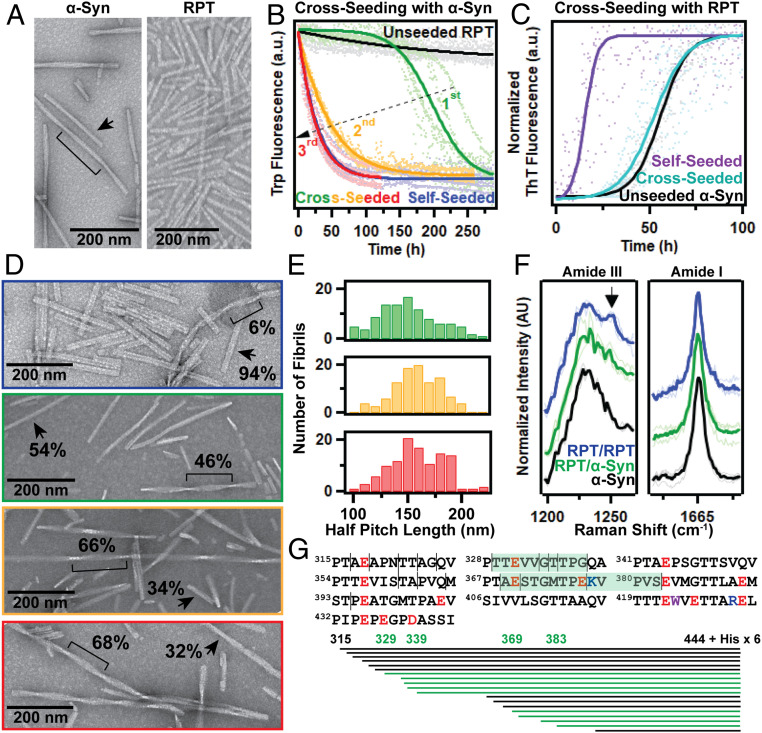

Upon establishing that α-syn is found alongside Pmel17 in the melanosome, we next evaluated whether α-syn modulated Pmel17 aggregation (Fig. 2). Given the epidemiological context of melanoma among PD patients, we chose cross-seeding experiments where preformed α-syn fibrils, which accumulate in PD, were added to soluble Pmel17 RPT (residues 315 to 444), an essential domain for fibril formation in melanosomes (11). α-Syn and RPT fibril seeds were generated by continuous agitation in pH 6 buffer, mimicking the acidic conditions of the melanosome as previously described (12). Visualization by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed a mixture of rod-like (arrows) and twisted (brackets) fibril morphologies for α-syn (Fig. 2A). In contrast, a homogeneous population of rod-like fibrils was formed by RPT under identical solution conditions.

Fig. 2.

α-Syn fibrils modulate RPT aggregation. (A) TEM images of unseeded α-syn and RPT fibrils, formed at pH 6 (20 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid, 100 mM NaCl) under shaking conditions. N-terminally acetylated α-syn was used in all experiments. Brackets and arrows represent twisted and rod-like filaments, respectively. (B and C) Aggregation of 30 µM RPT (black in B) and α-syn (black in C) alone, or with 3 µM preformed α-syn (green in B; purple in C) and RPT (blue in B; teal in C) seeds at pH 6, monitored by (B) Trp or (C) ThT fluorescence at 37 °C under quiescent conditions. In B, the blue and red curves overlay. First-generation cross-seeded fibrils (green in B) were propagated over two more generations, second (yellow in B) and third (red in B). Five replicates (dots) were averaged and fit to a sigmoidal curve (solid lines). (D) TEM images of fibrils from B. Brackets and arrows represent twisted and rod-like filaments, respectively, with the observed relative percentages (n ≥ 300). (E) Fibrils with a twisted morphology were analyzed to determine the half-pitch lengths, which averaged 150 ± 28, 158 ± 21, and 159 ± 25 nm for first-, second-, and third-generation cross-seeded fibrils, respectively (n ≥ 100). (F) Raman spectra of self-seeded RPT (blue), first-generation cross-seeded RPT (green), and unseeded α-syn (black) fibrils. Averaged spectra (thick lines) from three spatial locations (thin lines) were normalized to the amide-III (1,225 cm−1; Left) or amide-I (1,665 cm−1; Right) band. Data are offset for clarity. Arrow indicates a distinctive feature (1,250 cm−1) in self-seeded RPT fibrils, that is less prominent in cross-seeded and α-syn fibrils. Self-seeded RPT data are reproduced from previous work (12). (G) Schematic representation of cathepsin L limited digestion, where lines represent cleavage sites (Top) and peptide fragments (Bottom) observed in both self-seeded and cross-seeded RPT fibrils. Cleavage locations and fragments that were less abundant in cross-seeded relative to self-seeded fibrils are colored green.

Cross-seeding reaction kinetics of RPT were then monitored by the single native tryptophan (W423), a well-characterized fluorescent reporter of RPT aggregation (10). RPT aggregation was stimulated by the presence of α-syn seeds (green curve), although not as efficiently as self-seeded RPT (Fig. 2B, blue curve). The cross-seeding effect was unidirectional, as RPT fibrils did not influence α-syn aggregation (Fig. 2C). While 94% of self-seeded RPT fibrils displayed a rod-like morphology by TEM, an approximate 1:1 mixture of rod-like and twisted fibrils was observed for cross-seeded RPT (Fig. 2D). To exclude that the twisted fibrils are the original α-syn seeds (10% of the sample), sequential generations of fibrils were formed, decreasing the relative abundance of α-syn to 1% and 0.1%, respectively. Subsequent seeding enhanced RPT aggregation propensity (Fig. 2B, yellow and red curves) similar to that observed with self-seeding, and the population of α-syn−like twisted filaments increased (Fig. 2D). Further analysis found a similar half-pitch fibril length, with averages ranging from 150 nm to 160 nm (Fig. 2E). It is evident that α-syn fibrils can nucleate RPT aggregation, altering the ultrastructural features of the subsequent fibrils which can be faithfully propagated over multiple generations.

Validating that cross-seeded RPT fibrils have different structural features than self-seeded RPT fibrils, characterization by Raman microspectroscopy revealed subtle changes in the amide-III band shape akin to α-syn (Fig. 2 F, Left), while the overall β-sheet content remained comparable, as indicated by the amide-I band (Fig. 2 F, Right). Additionally, limited protease digestion with cathepsin L showed enhanced protection of RPT regions in cross-seeded vs. self-seeded fibrils, with reduced relative protease accessibility observed between residues 329 and 338 and between residues 369 and 382 (Fig. 2G). Together, the spectroscopic and biochemical data support that cross-seeded fibrils exhibit altered structure from those of unseeded/self-seeded RPT fibrils.

We propose that a molecular connection exists between α-syn and Pmel17 amyloid formation which links PD and melanoma, similar to other examples where amyloid interplay is implicated in disease pathology (13, 14). We hypothesize that α-syn, a pathogenic amyloid, infiltrates the process of functional amyloid formation of Pmel17, which alters melanogenesis, contributing to increased melanoma risk with loss of pigmentation. Future work will be dedicated to investigating this hypothesis.

Methods

Cell culture, confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, and immunoblotting were performed as previously reported (15). For subcellular fractionation, cells were grown in T-175 flasks, then fractionated using commercially available kits (Thermo Scientific). Published procedures were followed (12, 15) for recombinant protein expression, purification, aggregation assays, and fibril characterization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). We thank the NHLBI Protein Expression Facility, Electron Microscopy, and Biochemistry Cores.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article.

References

- 1.Goedert M., α-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 492–501 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen J. H.et al., Atypical cancer pattern in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Br. J. Cancer 92, 201–205 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen J. H., Friis S., Frederiksen K., Malignant melanoma and other types of cancer preceding Parkinson disease. Epidemiology 17, 582–587 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertoni J. M.et al.; North American Parkinson’s and Melanoma Survey Investigators , Increased melanoma risk in Parkinson disease: A prospective clinicopathological study. Arch. Neurol. 67, 347–352 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo Y., Kamitani T., Parkinson’s disease-related protein, α-synuclein, in malignant melanoma. PLoS One 5, e10481 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee B. R., Kamitani T., Improved immunodetection of endogenous α-synuclein. PLoS One 6, e23939 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turriani E.et al., Treatment with diphenyl−pyrazole compound anle138b/c reveals that α-synuclein protects melanoma cells from autophagic cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E4971–E4977 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan T., Zhu J., Hwu W. J., Jankovic J., The role of α-synuclein in melanin synthesis in melanoma and dopaminergic neuronal cells. PLoS One 7, e45183 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bose A., Petsko G. A., Eliezer D., Parkinson’s disease and melanoma: Co-occurrence and mechanisms. J. Parkinsons Dis. 8, 385–398 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGlinchey R. P., Lee J. C., Reversing the amyloid trend: Mechanism of fibril assembly and dissolution of the repeat domain from a human functional amyloid. Isr. J. Chem. 57, 613–621 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoashi T.et al., The repeat domain of the melanosomal matrix protein PMEL17/GP100 is required for the formation of organellar fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21198–21208 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean D. N., Lee J. C., Modulating functional amyloid formation via alternative splicing of the premelanosomal protein PMEL17. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 7544–7553 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson T. R.et al., A gut bacterial amyloid promotes α-synuclein aggregation and motor impairment in mice. eLife 9, e53111 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horvath I., Wittung-Stafshede P., Cross-talk between amyloidogenic proteins in type-2 diabetes and Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 12473–12477 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGlinchey R. P.et al., C-terminal α-synuclein truncations are linked to cysteine cathepsin activity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 9973–9984 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article.