The MCU holocomplex, MCUcx

Cytosolic calcium enters the mitochondrial matrix through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) where it acts as a signal that regulates ATP production (1), metabolic fuel selection (1–3), and if excessively high, triggers cell death (4). The complete complex of the MCU subunits is now referred to as the mitochondrial calcium uniporter holocomplex (MCUcx) (5). In PNAS, Vais et al. (6) focus on how the levels of Ca2+ inside the mitochondrial matrix ([Ca2+]m) can regulate the MCUcx itself. Here, the MCUcx was investigated by patch clamping a vesicular preparation made from the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) of a single mitochondrion, called a “mitoplast” (Fig. 1A). This approach was pioneered 17 y ago by Yuriy Kirichok, Grigory Krapivinsky, and David Clapham (7) and was a huge step toward our understanding of how mitochondria work. By patch clamping single mitoplasts from COS-7 cells or a region of the mitoplast membrane, they identified a femto-Siemens (fS) single-channel conductance under physiological conditions. It was highly selective for Ca2+ and had an open probability (Po) that was steeply voltage dependent. They suggested that this channel was a good candidate for the MCUcx (Fig. 1B). Two independent groups (8, 9) then showed that a molecular component of MCUcx was the likely pore-forming subunit, here called MCUpore but also frequently called “the MCU.” Elucidation of MCUcx structure and function also included the identification of key auxiliary subunits including MICU1-3 (mitochondrial calcium uptake 1-3) and EMRE (essential MCU regulator) (10, 11). Hugely important to our broad understanding of MCUcx was the follow-up work by the Kirichok laboratory. They suggested that there were critical differences in the multisubunit MCUcx in different tissues (12). For example, mitoplasts from different tissues had dramatically different MCUcx current densities! Mouse heart mitoplasts had a significantly lower IMCUcx density than did mitoplasts from skeletal muscle, liver, kidney, and brown fat in mouse. Drosophila flight muscle mitoplasts had barely detectable IMCUcx compared with all other types of mitoplasts. Furthermore, Williams et al. (13) showed that another specific tissue-dependent feature of IMCUcx density was that it appears to decrease as mitochondrial volume fraction within different types of cells increased. Thus, in heart muscle cells and in Drosophila flight muscle cells where mitochondria are more abundant than in any other cell type, the IMCUcx density was the lowest. These observations and others (14–16) all suggest that the regulation of the MCUcx and its function depends importantly on the tissues and organisms in which the mitochondria are located.

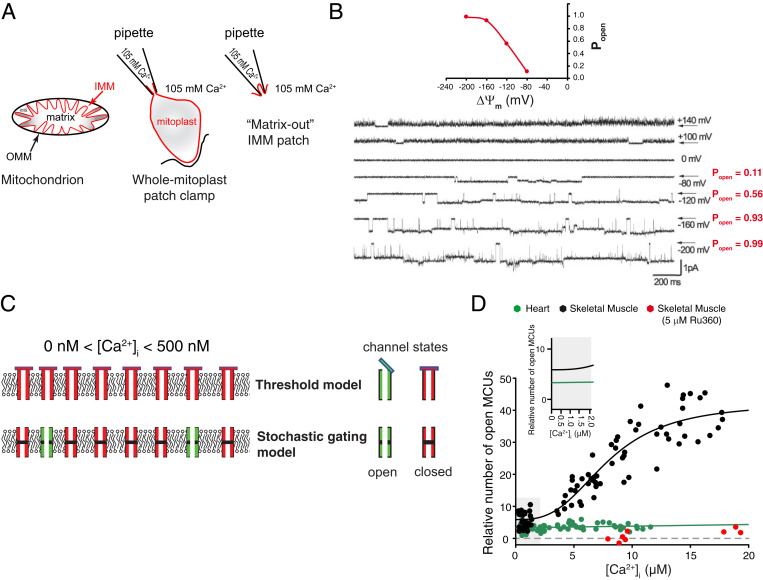

Fig. 1.

Ca2+ flux through MCUcx. (A) Diagram of the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM; black) and the IMM (red). Mechanical shearing is used to make the IMM vesicles and mitoplasts (red). (B) Matrix-out patch-clamp records of iMCUcx at potentials from –200 to +140 mV. Stochastic gating (openings and closures) and the voltage dependence of the open probability (Po) of MCUcx channels are shown. Modified by permission from ref. 7, Springer Nature: Nature, copyright (2004). (C) Illustration of the two models of MCUcx channel activity at or below threshold [Ca2+]i (0 to ∼500 nM), threshold [Vais et al. (6)], and “stochastic gating” models. (D) Measurements of the relative number of open MCUcx per mitochondrion and the dependence on [Ca2+]i for cardiac (green) and skeletal muscle (black) and Ru360-treated skeletal muscle (red). Zoomed-in view (Inset) of [Ca2+]i at 0 to 2 μM. No conduction threshold is observed in either cardiac or skeletal muscle MCUcx. Note that in skeletal muscle, the number of open MCUcx depends on [Ca2+]i (over the range from 3 to 20 μM) but not in heart. Skeletal muscle data are fit to a modified Hill equation with a K0.5 of 7.9 μM and a Hill coefficient of 2.95. Modified by permission from ref. 1, Springer Nature: Nature Metabolism, copyright (2019).

Game Changer

The paper by Vais et al. (6) in PNAS focuses on how [Ca2+]m may interact with the subunits in the MCUcx to control its current, IMCUcx [figure 1A in Vais et al. (6)]. Like Kirichok et al. (7), Vais et al. (6) used a mitoplast preparation to investigate IMCUcx. The mitoplasts in Vais et al. (6) are from a widely studied model cell preparation that originates with the human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293 cells, and further transformed to make the HEK293T cells. The “T” version of the HEK293 cells expresses a mutant version of the SV40 large T antigen oncoprotein. This constitutes the “wild-type” (WT) version of the cells used in the study by Vais et al. (6). Knockouts of specific MCUcx subunits were made in the WT HEK293T cells and verified. Molecular tools available provide advantages for the use of HEK293T cells. Disadvantages and concerns are discussed below. Importantly, however, using the present approach, Vais et al. (6) have measured and controlled matrix Ca2+, [Ca2+]m. This is a game changer in studying how the MCUcx works.

Results

The discoveries of Vais et al. (6) were possible because they actually measured [Ca2+]m. The primary finding of Vais et al. (6) is that [Ca2+]m regulates the MCUcx current (IMCUcx) in WT mitoplasts in a biphasic manner. In these experiments, extremely high extramitochondrial [Ca2+] was kept constant, and they tested how different levels of [Ca2+]m affected IMCUcx. At low [Ca2+]m (i.e., 1 to 10 nM), the Ca2+ current through the WT version of the MCUcx channel is large, and it decreases by fourfold to a minimum at around 400 nM and then increases again to the same “maximum” at around 2 µM [Ca2+]m. The second finding is that the Ca2+ current minimum of IMCUcx found in WT MCUcx around 400 nM [Ca2+]m, which constitutes the point of “maximal suppression,” appears to depend on specific molecular microdomains of the MCUpore. When two aspartic acids in the matrix-facing amino-terminal domain of MCUpore were individually mutated to alanines, the point of maximal suppression changed. The third finding is that the point of maximal suppression also changes by altering the subunit composition of the MCUcx. This was achieved by individually knocking out the auxiliary subunits of MCUcx (i.e., either MICU1 or MICU2) or by preventing their interaction with MCUcx using a mutated EMRE subunit. These findings are surprising because MICU1 and MICU2 have been shown to reside in the intermembrane space—not in the matrix. This raises the question of how could MCUcx sensitivity to Ca2+ in the matrix be altered by genetic elimination of subunits that reside in the intermembrane space and serve to sense Ca2+ in the intermembrane space. To resolve this seeming conundrum, Vais et al. (6) hypothesize that Ca2+-sensing microdomains of the MCUcx on both sides of the inner membrane are functionally interdependent—forming a coupled Ca2+-regulatory mechanism.

The Threshold Model

Vais et al. (6) suggest a very specific model of the MCUcx to explain how the MICUs work in the cell to manage the conductance of MCUcx [figure 4 in Vais et al. (6)]. They suggest that [Ca2+]m tunes how MICU1 works as a plug of the channel at the intermembrane surface of the IMM. Such a plug or bung is proposed by both Vais et al. (6) and other studies to block the channel sterically when [Ca2+]i is too low—below a putative “threshold” level of [Ca2+]i of about 500 nM or less (16–19). It is widely held that such an MCUcx threshold applies to physiological states. The threshold is defined to be the [Ca2+]i or “extramitochondrial” [Ca2+] level below which there is no Ca2+ conductance by MCUcx. Thus, at [Ca2+]i below the threshold, there should be no MCUcx Ca2+ flux into the mitochondrial matrix. This threshold model, shown in Fig. 1C, also involves a “gatekeeping” function that is largely attributed to the MICUs in the IMS (intermembrane space), but the details remain vague. Presumably, as we understand it, at [Ca2+]i levels above threshold a traditional stochastic gating model applies, and the threshold caps are open.

Model Complexities

Importantly, however, physiologically the MCUcx channel is a low conductance (fS), Ca2+-selective ion channel that can stochastically open and close as shown in mitoplast single-channel recordings (7, 20) (Fig. 1B). This figure also reveals a huge influence of voltage across the IMM on the open probability of the MCUcx. When the open probability (Po) of the MCUcx is zero, then all channels should be closed—as is thought to occur below the [Ca2+]i threshold level. This is the threshold model. However, such Ca2+ threshold feature of the MCUcx is exquisitely challenging to measure by electrophysiological approaches, particularly when [Ca2+]i is low and within the physiological range (100 nM to ∼3 µM). This difficulty arises because the signal to noise gets worse at low [Ca2+]i. To overcome these challenges, an approach has been developed and used in isolated mitochondria to estimate the number of open MCUcx channels in a mitochondrion and also measure the Ca2+ influx directly through the MCUcx channels in heart (1). This work uses optical tools with excellent signal to noise over the physiological [Ca2+]i range. In contrast to prior suggestions, this method indicates that there is no MCUcx threshold in either heart or skeletal muscle MCUcx. This difference could be due to signal-to-noise issues (for those observing a hard threshold [Ca2+]i) or likely could be due to the different tissues used in different studies. Therefore, perhaps a simpler model may suffice for those who find no threshold and should be considered as a possibility for those who do find a threshold. The pure stochastic model assumes no threshold nor an IMS plug. This model is labeled as the “stochastic gating model” in Fig. 1C.

Stochastic Gating Model?

A stochastic gating model as suggested by Kirichok et al. (7) and shown in Fig. 1 B and C is consistent with the recent electrophysiological findings by Garg et al. (20), who used a mitoplast preparation to examine the gating of IMCUcx. For these experiments, Garg et al. (20) used mouse embryonic fibroblast cells that were drp1 null. (Drp1 is a protein in the outer mitochondrial membrane mediating mitochondrial fission.) In the absence of Ca2+ (in 0 [Ca2+]i), the Na+ permeation through MCUcx was examined and showed a robust IMCUcx. Hence, under these conditions, there is no conduction occlusion, no gatekeeping, and no threshold. In addition, Garg et al. (20) also found that in the absence of MICU1, the open probability of the MCUcx was two- to threefold lower than in their WT MCUcx. This finding further supports the role of MICU1 as a critical component of the activation gate in the MCUpore itself. Thus, to date, there are multiple reports that support the simplistic model that includes a Ca2+-dependent activation gate. However, Ca2+ conduction threshold has not been shown or measured directly by any electrophysiological study of the MCUcx, nor under any condition when the conductance can be quantitatively assessed. Indeed, Vais et al. (6) did not find a conductance occlusion nor conductance threshold in either their figure 1B or 4A.

Conclusion

MCUcx features depend on the tissue. With the goal of reaching a broad and generalizing understanding of MCUcx, it may be important to reemphasize one of the major findings of the Kirichok group that different tissues appear to have unique MCUcx Ca2+ conductance properties. This conclusion is also consistent with the recent finding of Wescott et al. (1), who showed that the number of open MCUcx channels is regulated by [Ca2+]i in skeletal muscle but not in heart (Fig. 1D). Other studies have also reported critical differences between the MCUcx of the heart, skeletal, and liver mitochondria (15, 16). Thus, the current exciting findings of Vais et al. (6) provide us with an interesting and different model for how the MCUcx works in HEK293T cells. At the present time, it would appear, however, that because of the functional diversity of the MCUcx, it is still difficult to generalize from the findings in one cell type to create a single overarching model of how MCUcx works everywhere. Furthermore, it may also be difficult to assume that the molecular structure of the purified MCUcx from one cell type or one tissue (5) necessarily represents the structure of MCUcx in all other cell types and in all stages of life. This discussion raises the question again: “how does the MCUcx really work?” The practical answer at this point is that it depends on the tissue. Nevertheless, significant important progress is being made, and this is nicely illustrated in the paper by Vais et al. (6).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 15SDG22100002 (to L.B.) and by grants (to W.J.L.) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R01HL142290, U01HL116321, 1R01HL140934) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (1R01AR071618).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

See companion article, “Coupled transmembrane mechanisms control MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake,” 10.1073/pnas.2005976117.

References

- 1.Wescott A. P., Kao J. P. Y., Lederer W. J., Boyman L., Voltage-energized calcium-sensitive ATP production by mitochondria. Nat. Metab. 1, 975–984 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwong J. Q., et al., The mitochondrial calcium uniporter underlies metabolic fuel preference in skeletal muscle. JCI Insight 3, e121689 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altamimi T. R., et al., Cardiac-specific deficiency of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter augments fatty acid oxidation and functional reserve. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 127, 223–231 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carraro M., Carrer A., Urbani A., Bernardi P., Molecular nature and regulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore(s), drug target(s) in cardioprotection. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 144, 76–86 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan M., et al., Structure and mechanism of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter holocomplex. Nature 582, 129–133 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vais H., Payne R., Paudel U., Li C., Foskett J. K., Coupled transmembrane mechanisms control MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 21731–21739 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., Clapham D. E., The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427, 360–364 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baughman J. M., et al., Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476, 341–345 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Szabò I., Rizzuto R., A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476, 336–340 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamer K. J., Mootha V. K., The molecular era of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 545–553 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mammucari C., Gherardi G., Rizzuto R., Structure, activity regulation, and role of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in health and disease. Front. Oncol. 7, 139 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fieni F., Lee S. B., Jan Y. N., Kirichok Y., Activity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter varies greatly between tissues. Nat. Commun. 3, 1317 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams G. S., Boyman L., Chikando A. C., Khairallah R. J., Lederer W. J., Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10479–10486 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bick A. G., Calvo S. E., Mootha V. K., Evolutionary diversity of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Science 336, 886 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vecellio Reane D., et al., A MICU1 splice variant confers high sensitivity to the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake machinery of skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell 64, 760–773 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paillard M., et al., Tissue-specific mitochondrial decoding of cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals is controlled by the stoichiometry of MICU1/2 and MCU. Cell Rep. 18, 2291–2300 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallilankaraman K., et al., MICU1 is an essential gatekeeper for MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake that regulates cell survival. Cell 151, 630–644 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antony A. N., et al., MICU1 regulation of mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake dictates survival and tissue regeneration. Nat. Commun. 7, 10955 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paillard M., et al., MICU1 interacts with the D-ring of the MCU pore to control its Ca2+ flux and sensitivity to Ru360. Mol. Cell 72, 778–785.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garg V., et al., The mechanism of MICU-dependent gating of the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. 10.1101/2020.04.04.025833 (6 April 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]