Abstract

Objective:

Mental health (MH) care in remote areas is frequently scarce and fragmented and difficult to compare objectively with other areas even in the same country. This study aimed to analyze the adult MH service provision in 3 remote areas of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries in the world.

Methods:

We used an internationally agreed set of systems indicators, terminology, and classification of services (Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs for Long Term Care). This instrument provided a standard description of MH care provision in the Kimberley region (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland), areas characterized by an extremely low population density and high relative rates of Indigenous peoples.

Results:

All areas showed high rates of deprivation within their national contexts. MH services were mostly provided by the public sector supplemented by nonprofit organizations. This study found a higher provision per inhabitant of community residential care in Nunavik in relation to the other areas; higher provision of community outreach services in the Kimberley; and a lack of day services except in Lapland. Specific cultural-based services for the Indigenous population were identified only in the Kimberley. MH care in Lapland was self-sufficient, and its care pattern was similar to other Finnish areas, while the Kimberley and Nunavik differed from the standard pattern of care in their respective countries and relied partly on services located outside their boundaries for treating severe cases.

Conclusion:

We found common challenges in these remote areas but a huge diversity in the patterns of MH care. The implementation of care interventions should be locally tailored considering both the environmental characteristics and the existing pattern of service provision.

Keywords: service provision, DESDE-LTC, rural and remote mental health, service mapping, mental health care

Abstract

Objectif :

Les soins de santé mentale en région éloignée sont fréquemment rares, fragmentés et difficiles à comparer objectivement avec d’autres régions, même dans le même pays. La présente étude visait à analyser la prestation de services de santé mentale pour adultes dans trois régions éloignées de pays de l’Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE) dans le monde.

Méthodes :

Nous avons utilisé un ensemble internationalement reconnu d’indicateurs de systèmes, de terminologie et de classification des services (DESDE-LTC). Cet instrument a offert une description standard de la prestation des soins de santé mentale dans les régions de Kimberley (Australie), du Nunavik (Canada) et de la Laponie (Finlande), qui sont caractérisées par une densité de population extrêmement faible et des taux relativement élevés de populations autochtones1.

Résultats :

Toutes les régions affichaient des taux élevés de privation dans le cadre de leurs contextes nationaux. Les services de santé mentale étaient surtout prodigués par le secteur public assisté par des organisations sans but lucratif. Cette étude a constaté une prestation plus élevée par habitant de soins résidentiels communautaires au Nunavik, relativement aux autres régions; une prestation plus élevée de services d’approche communautaires au Kimberley; et une absence de services de jour excepté en Laponie. Des services spécifiques adaptés à la culture de la population autochtone ont été relevés seulement au Kimberley. Les soins de santé mentale en Laponie étaient auto-suffisants, et le modèle des soins était semblable à celui d’autres régions finlandaises, alors que le Kimberley et le Nunavik différaient du modèle de soins standard de leurs pays respectifs, et qu’ils utilisaient en partie les services situés hors de leurs limites pour traiter les cas graves.

Conclusion :

Nous avons observé des problèmes communs dans ces régions éloignées, mais une énorme diversité dans les modèles de soins de santé mentale. La mise en œuvre des interventions de soins devrait être personnalisée localement en tenant compte des caractéristiques environnementales et du modèle existant de prestation des soins.

Introduction

Rural and remote areas have specific local and structural conditions that affect the different dimensions of access to health care.1 Service availability is strongly affected by contextual factors such as geography, population characteristics, and service provision.2–4 Remote areas are characterized by low population densities, few local residents, geographical dispersion of population centers, and poor space–time accessibility.2,5 Remote populations live in different biomes and have distinct social and demographic characteristics such as age profile, social relations and structures, a higher proportions of Indigenous peoples, seasonal demographic variation, and specific patterns of morbidity.6–10 Moreover, health service provision has additional issues, like endemic in situ workforce shortages and/or turnover of clinical staff, high rates of out-of-area care, and lower population thresholds at which health services should be provided in comparison with other rural areas.3,11 In addition, the balance and mix of generalist health services versus specialized care differs from the standard models used for rural and urban areas.

The integrated nature of mental health (MH) care is especially hampered in rural areas where services are usually scarce and fragmented.5,12 Advances in health technologies may improve accessibility, but these interventions may also involve higher costs when intended for very small communities,13 and they cannot fully replace face-to-face care.14 Moreover, there is a need to design models of care, interventions, and services that are culturally specific, given the lower service utilization, disruptions in the continuum of care, poorer MH, and higher suicide rates of Indigenous peoples.15–17

In order to plan effectively integrated systems, it is first necessary to perform a comparative analysis of the current delivery system.18,19 The “Global Mental Health Atlas project” comprises a series of studies on the provision of services in health areas around the world that encompass a global perspective on common measurement for comparison and organizational learning, and a focus on the local characteristics and patterns of service provision.20 These comparisons are based on the standard description of services by using the Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs for Long Term Care (DESDE-LTC),21 in combination with analyses of socioeconomic context, health and service use, and geographical maps. So far over 25 atlases and standardized directories of services have been developed in different countries, including Australia,22–24 Chile,25 Finland,26,27 and Spain.28

This study aims to analyze the provision of MH care in the health areas of the Kimberley region (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland). These areas reflect the particular challenges of MH care delivery and planning in remote areas of high-income Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries in 3 different world areas.12,17,29–34 Moreover, these countries have recently been classified in different types of OECD health care systems.35

Methods

Study Areas

Kimberley

The Kimberley region is located in the far north of Western Australia (WA). The resident population is 34,279 inhabitants, 40% of whom live in Broome, whose total population increases 3-fold during the peak tourism season. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia are not separately recognized in the Australian constitution nor do they have self-government.36 Australia has a universal health system funded by the public Medicare system with uncapped co-payment for generalists including for general practitioners (GPs) and specialized nonhospital care. Private health care is common with around 66% of the West Australian population having some form of private insurance;37 however, Medicare co-payments are not insurable. Private insurance rates are lower among people outside urban centers. The WA Department of Health manages the public health services for the state. The Commonwealth Department of Health separately funds 143 Aboriginal community–controlled health services across Australia to provide co-payment-free primary health care for Indigenous communities.38 There are no WA data on private health insurance rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples nor national data for people living outside urban locations. For those living in urban centers (2012 to 2013), the rate of private insurance was around one-third of that found among non-Indigenous peoples.39 In Australia, access to MH care is through the referral of a GP; however, this care is not organized in catchment areas.40

Nunavik

The Nunavik area is located in the north of the Quebec province (Canada) and encompasses 2 catchment hospital areas (Ungava Bay and Hudson Bay) for a total population of 13,188 inhabitants. There are 14 villages scattered along the 2 coastlines and only connected to each other and to the outside world by plane. Nunavik is the homeland of the Inuit in Quebec. The Canadian Constitution recognizes Indigenous rights and self-government. The Inuit of Nunavik have their own regional government, albeit with limited executive capacity. Canada has a decentralized health system that is universal and mostly public financed. Health and social services are managed by the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services to ensure that services are fit for purpose for the Inuit. MH care in Nunavik is provided by specialized services in the regional hospitals. Patients are referred from the health centers located in each village. Health centers have a permanent doctor if the village has more than 1,000 inhabitants. Otherwise, doctors attend on a regular basis, once a month, and nurses provide MH first aid.

Lapland

Lapland hospital district (hereinafter Lapland) is located in the Lapland region (Finland) in the north of the Scandinavian Peninsula. It covers 15 municipalities, with a population of 117,447 inhabitants that increases during the holiday season. The district comprises a part of the cross-border cultural region of Lapland (Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Russia) traditionally inhabited by the Sámi, although nowadays they are a minority group. Sámi hold self-government, with their own Parliament, and they are acknowledged as the original inhabitants of Lapland in the Finnish Constitution.

Municipalities provide health services on their own in collaboration with other municipalities or buy them from private providers. Specialized health care services are mostly provided by hospital districts, owned, and governed by the municipalities. Municipal health centers fulfil a gatekeeping function to specialized care.27 Most of these centers have specialized MH staff. Psychiatric care at the secondary level is coordinated by hospital districts. Sámi have the right to services in their own languages in their native region. In the Sámi Homeland, the Social Affairs and Health Committee of the Sámi Parliament is an advisory body with the aim of advancing the rights and position of the Sámi in the social affairs and health care system.

Tools

The European Service Mapping Schedule (ESMS) and its latest validated version the DESDE-LTC constitute a unique approach for the classification and description of care services in selected health areas.21,41 The ESMS/DESDE system firstly identifies “Basic Stable Inputs of Care” (BSICs), which are defined as “the minimal organizational unit with temporal stability arranged for delivering care to a defined population in an area.”18,21 Then, the main meaningful activity provided by BSICs is described through the “Main Types of Care” (MTC). There are over 100 codes to describe MTC classified in 6 branches: residential, day, outpatient, information, accessibility and self-help, and voluntary care. Complementary to the ESMS/DESDE glossary published elsewhere,42 a glossary of terms, codes, and descriptions has been included in Online Annex 1 for a better understanding.

Inclusion criteria

Services (BSICs) included in the study fulfilled the following criteria:

Specialized, defined as targeting people with a lived experience of mental illness including any diagnosis of mental disorders (ICD-10, section F).

Universally accessible, defined as not having a significant out-of-pocket cost.

Stable, defined as having “temporal stability” (typically the service has received funding for more than 3 years), and “organizational stability” defined as having administrative support, its own space, finances, and documentation to track activity.

Care provision within the boundaries of study areas. Services out of the catchment area were coded when at least 10% of residential and day care users and 20% outpatient care users belonged to the catchment area.

Providing direct care or support to clients.

Services for adult population (≥18 years old).

Data collection and analysis

The data collection followed a health care ecosystem approach that intended to identify all services available from any sector for the same target population.43 Information on service provision was obtained following a bottom-up approach through interviews with managers of the local organizations between 2017 and 2019. The experience gathered through conducting atlases of MH care in several countries using ESMS/DESDE44 indicates that this approach has a higher validity than using the official listings or directories of services. Services were gathered from the Atlas of Mental Health Care of the Kimberley Region45 and from 2 service provision studies developed in Nunavik and Lapland. The surveys were conducted using the same method, and the coding was checked and supervised by the same expert in DESDE-LTC (MRGC).

MTC availability and placement capacity rates per 100,000 inhabitants and large care groups were calculated and depicted in spider graphs. Additionally, balance of health care versus other care46 and diversity of care were also described.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics at study area and country levels. The 3 areas showed extremely low population density, Lapland being the most populated. In brief, the Kimberley was the area with a greater overseas-born population and fewer single parent families and unemployed people. Nunavik had the highest rates of Indigenous peoples, single parent families, unemployment and suicide; and lower rates of aging, living alone, and university studies. Finally, Lapland was characterized by having the most aged population, the highest rate of people living alone and with higher educational attainment; and the lowest proportion of Indigenous peoples. In Lapland, Sámi had a higher suicide rate than the entire Finnish population, yet this difference was not marked. In Nunavik, the suicide rate of the Inuit was around 9 times higher than the Canadian rate, whereas the rate in Kimberley was 4 times higher than the Australian average.

Table 1.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Indicators of the Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland).

| Kimberley | Australia | Nunavik | Canada | Lapland | Finland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biome | Tropical savanna | — | Coastal tundra-taiga |

— | Inland tundra-taiga |

— |

| Area (km2) | 419,558 | 7,741,120 | 443,132 | 8,965,589 | 91,733 | 390,905 |

| Total population | 34,279 | 23,401,891 | 13,188 | 35,151,728 | 117,703 | 5,503,297 |

| Density ratio | 0.08 | 3.02 | 0.02 | 3.9 | 1,37 | 18.11 |

| Dependency ratio | 44.23 | 52.35 | 59.40 | 50.37 | 60.4 | 59.1 |

| Aging index | 25.38 | 84.24 | 11.20 | 101.65 | 154,0 | 128.6 |

| Indigenous status | 46.19% | 2.95% | 91.38% | 4.86% | 4.00%a | 0.18%a |

| Born overseas | 13.70% | 28.30% | 1.14% | 21.45% | 2.69% | 6.63% |

| Single parent families | 16,21% | 7.83% | 38.03% | 16.39% | 22.5% | 21.6% |

| Living alone | 8.09% | 8.65% | 5.73% | 11.29% | 43.5% | 42.6% |

| Persons with university studies (≥15) | 14.02% | 21.96% | 7.93% | 26.09% | 26.4% | 30.4% |

| Unemployment | 8.62% | 6.86% | 15.4% | 7.7% | 10.7% | 8.8% |

| Yearly suicide rate per 100,000 (general population) | 36b | 11.7 | 114.6c | 11.2c | 18.7d | 14.3d |

| Yearly suicide rates per 100,000 (Indigenous/non-Indigenous) | 74/11b | 23.8/11.4 | 98.1e/— | 24.3/8.0e | — | — |

| Sources | Australian Bureau of statistics, 201629 | Australian Bureau of statistics, 2016 | Statistics Canada, 201647 | Statistics Canada, 201647 | Statistics Finland, 2016 | Statistics Finland, 2016 |

a Personal communication with the Sámi Parliament, data for 2019.

b Data for 2005 to 2014.

c Statistics Canada, 2004 to 2008.

d Data for Lapland region, 2016.

e Data for 2011 to 2016.

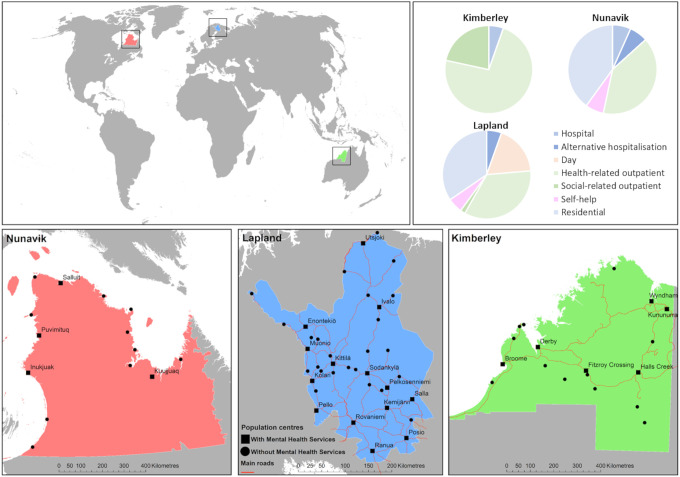

Figure 1 shows the location of population centers, MH services, and roads in the Kimberley, Nunavik, and Lapland, as well as the percentage of services by DESDE-LTC large branches. Additionally, Table 2 collects information on the MH service standard classification in the 3 areas.

Figure 1.

Location of the specialized mental health services and in the Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada) and Lapland (Finland), and proportion of mental health care by main branches of the DESDE-LTC classification of care services. DESDE-LTC = Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs for Long Term Care.

Table 2.

Mental Health Service Provision in the Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland).

| Kimberley | Nunavik | Lapland | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health service provision | |||

| Total Basic Stable Inputs of Care (BSIC) | 27 | 14 | 50 |

| Total Main Types of care (MTC) | 37 | 15 | 55 |

| Care diversity (different MTC) | 8 | 7 | 17 |

| Health care/social care (MTC) | 29/8 | 8/7 | 26/29 |

| Public/private (MTC) | 30/7 | 9/6 | 48/7 |

| Care classification (placement capacity in brackets) | |||

| Residential care | |||

| Hospital | |||

| Acute (e.g., acute ward) | 2 (13 beds) | 1 (1 bed) | 1 (14 beds) |

| Nonacute (e.g., subacute ward) | 0 | 0 | 2 (32 beds) |

| Alternative to hospital | |||

| Acute (e.g., acute crisis home) | 0 | 1 (6 bedsa) | 0 |

| Nonacute (e.g., nonacute crisis home) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Community residential | |||

| High intensity (e.g., hostel) | 0 | 3 | 6 (100 bedsa) |

| Medium and low intensity (e.g., supported accommodation, group home) | 0 | 3 (9 bedsa) | 13 (133 bedsa) |

| Day care | |||

| Acute health (e.g., day hospital) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonacute health (e.g., day health center) | 0 | 0 | 3 (6 placesa) |

| Work related (e.g., social firm) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other (e.g., social club) | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Outpatient care | |||

| Health | |||

| Acute mobile (e.g., crisis home teams) | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute nonmobile (e.g., emergency room) | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Nonacute Mobile (e.g., assertive community treatment) | 12 | 0 | 4 |

| Nonacute nonmobile (e.g., community mental health center) | 0 | 5 | 14 |

| Social | |||

| Nonacute nonmobile (e.g., social counselling) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonacute mobile (e.g., personal helpers and mentors service program) | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Acute nonmobile (e.g., social emergency room) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute mobile (e.g., crisis mobile teams) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Accessibility to care | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-help care | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Information for care | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a Incomplete data.

Kimberley

The Kimberley region had 27 BSICs (care teams), which were described through 37 MTCs (codes related to their main type of care). The care diversity measured by the range of different types of MTCs provided in the region was low with 8 different DESDE-LTC codes belonging only to the residential and outpatient branches. Most of the services were public (81.1% of the all the MTCs). The analysis of balance of care showed a predominantly health-oriented system with 29 services providing core health care (78.4%) and 8 services providing other types of MH care (21.6%).

There were 2 acute hospital services with 13 beds for consumers; however, community residential services were absent in the region. Regarding the 35 outpatient services identified, 68.6% were mobile, and 51.4% were nonacute. Moreover, there were 14 services specifically for Indigenous peoples, including 2 for suicide prevention. There were another 2 services specifically for suicide prevention and bereavement available to any population.

Nunavik

Nunavik included 14 BSICs that were described by 15 MTCs using 7 different codes. The balance between health and social care was similar (53.3% and 46.7% of the MTCs, respectively). Moreover, 60% of the services were publicly provided.

Only one of the 2 regional hospitals provided psychiatric acute care and emergency outpatient care (Ungava Bay hospital) with 1 bed specifically for MH care. Usually, general physicians collaborating with nurses were responsible for screening, evaluation, and admission of patients. In each hospital, a psychiatrist was available 1 week a month on site or otherwise available via call/video conference during the evaluation process. If needed, patients with severe mental disorders were referred for acute hospitalization to Montreal. Alternatively, there was a crisis residential facility in the community with 6 beds for short-term highly structured accommodation of psychiatric patients in crisis. On-site consultation with a psychiatrist was available 4 times a year at some of the local community service centers that depend on the 2 regional hospitals. The service provision was completed with 6 residential facilities in the community. Finally, there were many voluntary organizations outside the network aimed at prevention and promotion of health (sewing, cultural activities, rangers, etc.), but for the purpose of this study, only the Qajaq network for men with mental disorders was included. There were no specific services for suicide prevention for Indigenous peoples.

Lapland

The adult MH service provision in Lapland required 17 different DESDE-LTC codes and 55 MTCs to describe its 50 BSICs. This included residential, day, outpatient, and self-help care; 87.3% of services (MTCs) were publicly funded (MTCs). Care in this region was well balanced (47.3% health care, 52.7% other care).

The district hospital provided both acute (14 beds) and nonacute (32 beds in 2 wards) care. The residential care was completed with 19 community residences providing over 233 beds. In addition, there were 10-day services available, mostly without the provision of individual care plans (i.e., the number of places is not fixed). Moreover, 20 services were classified as outpatient and 3 as self-help care.

The care profile of the region was characterized by a greater weight of community residences (86.4% of residential services); a higher proportion of non-health-related day services (70% of day services); larger number of nonmobile outpatient services (76.2% of the outpatient services); and predominance of nonacute outpatient services (95.2% of the outpatient services). Finally, it is worth mentioning that there were no targeted services for the Sámi or suicide prevention (these activities are addressed through specialized programs within the core services).

Comparison of study areas

Specialized staff in MH were only available in some population centers of Lapland. Isolation in Nunavik generated issues in initial access to MH care since the local health centers only had access to a physician 1 week a month. Besides, the police station jail was being used to contain people with acute and severe MH problems until recently.

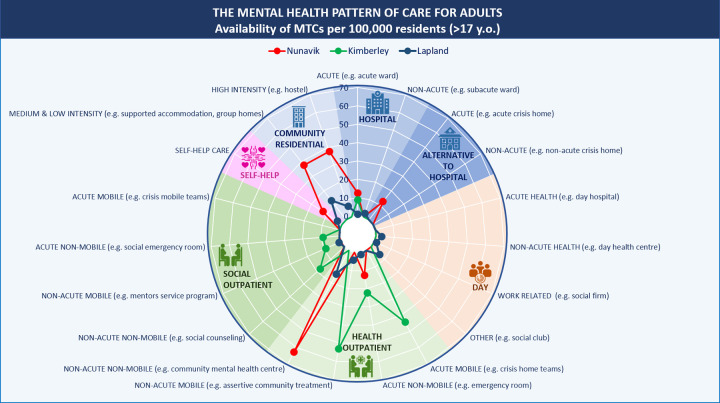

Figure 2 describes the pattern of MH services in the study areas. The availability rate per inhabitant was higher in Nunavik given its scarce population. Acute hospital care was higher in Nunavik, but the placement rate was higher in the Kimberley. Only Lapland had a couple of units for nonacute hospital care, while the Kimberley referred their patients to units outside the area. The Kimberley was the only area without community residential care, while the availability rate was very high in Nunavik. Only Lapland had day services. Finally, the availability of outpatient care services in the Kimberley was very high in comparison to the other 2 areas mainly related to mobile and to nonhealth related (e.g., community outreach services).

Figure 2.

Mental health service provision by main type of care group in the Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland). MTC = main type of care; R = residential care; D = day care; O = outpatient care; S = self-help care.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first standard description of the pattern of remote MH care across 3 OECD countries,35 using a health care ecosystem approach48 and a standard classification of services (DESDE-LTC).44 This study adds to the international comparisons carried out at the macrolevel (i.e., characteristics of the national system of government, legislation, governance, and financing, as well as national data on MH service provision).49,50 It is important to mention that the last OECD report on MH care provision was published more than a decade ago.51

The 3 areas showed substantially different service availability although they ascribed to the community MH model and shared comparable characteristics of remoteness. This may highlight the urban bias of the current model of community MH care and the lack of consensus on health care standards and indicators adapted to remote territories.14 Although Nunavik and the Kimberley had higher availability rates per inhabitant, real access is lower than in Lapland where most villages are connected by road, and the driving distances are smaller in favorable weather conditions. Transportation is hampered by climate conditions in Nunavik especially in winter and during the rainy season in the Kimberley. Thus, the availability rates should be completed with temporal accessibility analyses to be meaningful.

The absence of stable day services in the Kimberley is a characteristic of the Australian public MH system.22,23 Similarly, Nunavik also had no day care. The availability of day services in Lapland was identified in other remote areas in Norway and Russia.52 Even though day services are considered a key component of community MH care,53 their role in community care in remote areas requires further analysis. The sparse population and long distances between population centers may explain this gap in Nunavik as it could be difficult to reach a minimum of users to operate, but this is not the case of the Kimberley where the main center has over 14,000 inhabitants. Another common gap for all the areas was the accessibility to care and information to care services for people with a lived experience of mental illness.

Lapland had a higher flexibility and variety of care in comparison with the other areas, this might be related to population density, but further analysis is needed. Instead, the low diversity of care types in the Kimberley and Nunavik could indicate service duplication (i.e., many services deliver a similar MH care). Duplications could indicate more choice for consumers, especially in isolated areas, but also inefficiencies in the health system due to oversupply and missing opportunity costs.

Results from a previous study comparing remote areas in Russia and Norway using the previous version of the instrument ESMS identified a higher care diversity in both areas than in Nunavik and the Kimberley. Instead, the diversity was closely similar to Lapland.

There was no residential subacute or long-term bed-based MH care provision in the Kimberley. The nearest services were in Perth (2,200 km to the south), operated at capacity and were not routinely available to anyone from the Kimberley notwithstanding the logistics of supporting families with such an arrangement. Instead, patients who are unable to be discharged to community care remain in hospital, which means hospitals have lower capacity for people who need urgent access to care, reducing the availability of services overall.54 The development of small subacute units in regional hospitals should be considered in this context.

MH care for Indigenous peoples requires a different approach that recognizes it is they, not the provider who determines value. Relevant experts in the MH of Indigenous peoples claim that mainstream care is not working.55-57 Repeated studies have found Indigenous peoples perceive the MH system as too medicalized and remote from Indigenous health, social, and emotional well-being practices, so they are either not using them or using them as a last resort, preferring to seek help from traditional Healers, Elders, or Inummariks (Nunavik).12,15 Our study identified a lack of specific services in 2 areas with the highest populations of Indigenous peoples.

In all 3 areas, clinical and social professionals were mostly non-Indigenous. The Kimberley was the only area with specific services and Indigenous-controlled primary care provision. In Nunavik, despite Indigenous peoples comprising the vast majority of the population, transcultural MH care was lacking and there was a need for professionals to use language interpreters.32 In Lapland, Indigenous peoples were a minority and their specific needs have not been addressed either.

Indigenous cultural groups may be a key element to reach this at-risk population along with transcultural, multidisciplinary, and community-oriented services respectful of their framework of mental wellness.12,32,58 In the 3 regions, there were several community organizations excluded from the study because they were not specialized services for MH. However, they are an undervalued asset to promote mental well-being, prevent psychological distress, and provide social support in remote places with gaps in the MH care. Therefore, a greater collaboration between these organizations and MH care providers is recommended.32

This study has a series of limitations. First, there is not a standard definition of remoteness that can be used worldwide.59 This study selected areas below 1.5 inhabitants/km2. Second, these 3 areas do not reflect all the patterns of care in remote areas in Canada and in Australia. Third, this study is limited to the description of publicly funded specialized care for the adult population. In order to have a full pattern of service provision the description of general primary care, care for Indigenous peoples, private care, care for children and adolescents and older populations may be needed. Fourth, this study did not collect data on professionals in MH services for the 3 areas.

Conclusion

A better understanding how care is provided in remote regions could provide decision makers with useful organizational and contextual knowledge for future service planning. The disparate conditions found in this study encourages the design of a remote model of MH care, supported by comparative studies, to gather the best evidence-informed practices and define a minimum range of services in order to improve the MH of the population that resides in remote areas.

The collection of standardized information on service availability and capacity in remote areas, though very relevant, is just the first step toward a knowledge base for evidence-informed policy. In the case of rural MH, this should include specific system indicators as well as a specific model of rural MH care (Orange Declaration)14 based on local needs, local patterns of care, and benchmarking. In addition, next steps should include a complete analysis of health care access in remote areas, taking into account other domains apart from availability and capacity.1

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Supplement_material for Patterns of Mental Health Care in Remote Areas: Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland): Modèles de soins de santé mentale dans les régions éloignées: Kimberley (Australie), Nunavik (Canada) et Laponie (Finlande) by Jose A. Salinas-Perez, Mencia R. Gutierrez-Colosia, Mary Anne Furst, Petra Suontausta, Jacques Bertrand, Nerea Almeda PhD, John Mendoza, Daniel Rock, Minna Sadeniemi, Graça Cardoso and Luis Salvador-Carulla in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of Western Australia Primary Health Alliance (WAPHA), including Leigh Newman, and the assistance of Ms. Kirsty Snelgrove from WA Health. We are also grateful to the members of the Project Reference Group, to the Lapland Hospital District Psychiatric care division, and to all the service providers who participated in this study.

Authors’ Note: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Minna Sadeniemi is also affiliated with Department of Social Services and Health Care, City of Helsinki, Bipolar Disorder Research and Treatment Center, Helsinki, Finland and Mental Health Unit, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Helsinki, Finland.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jose A. Salinas-Perez, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8533-9342

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8533-9342

Mencia R. Gutierrez-Colosia, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2631-0205

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2631-0205

Petra Suontausta, MSSc/MHSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7555-1945

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7555-1945

Graça Cardoso, MD, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1756-0197

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1756-0197

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russell DJ, Humphreys JS, Ward B, et al. Helping policy-makers address rural health access problems. Aust J Rural Health. 2013;21(2):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas SL, Wakerman J, Humphreys JS. Ensuring equity of access to primary health care in rural and remote Australia—what core services should be locally available? Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bourke L, Humphreys JS, Wakerman J, Judy T. Understanding drivers of rural and remote health outcomes: a conceptual framework in action. Aust J Rural Health. 2012;20(6):318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzpatrick SJ, Perkins D, Luland T, Dale B, Eamonn C. The effect of context in rural mental health care: understanding integrated services in a small town. Health Place. 2017;45:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly BJ, Lewin TJ, Stain HJ, et al. Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(12):1331–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inder KJ, Berry H, Kelly BJ. Using cohort studies to investigate rural and remote mental health. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(4):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eckert KA, Taylor AW, Wilkinson DD, Graeme RT. How does mental health status relate to accessibility and remoteness? Med J Aust. 2004;181(10):540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enticott JC, Meadows GN, Shawyer F, Inder B, Patten S. Mental disorders and distress: Associations with demographics, remoteness and socioeconomic deprivation of area of residence across Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(12):1169–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butterworth P, Kelly BJ, Handley TE, Inder KJ, Lewin TJ. Does living in remote Australia lessen the impact of hardship on psychological distress? Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(5):500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wakerman J, Humphreys J, Russell D, et al. Remote health workforce turnover and retention: what are the policy and practice priorities? Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lessard L, Fournier L, Gauthier J, Diane M. Continuum of care for persons with common mental health disorders in Nunavik: a descriptive study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27186 2015 May 14 [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.3402/ijch.v74.27186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Productivity Commission. Mental Health Productivity Commission draft report. Canberra, Australia: Productivity Commission; 2019:1–602. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perkins D, Farmer J, Salvador CL, Dalton H, Georgina L. The orange declaration on rural and remote mental health. Aust J Rural Health 2019;27(5):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McIntyre C, Harris MG, Baxter AJ, et al. Assessing service use for mental health by Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America: a rapid review of population surveys. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boksa P, Joober R, Kirmayer LJ. Mental wellness in Canada’s Aboriginal communities: striving toward reconciliation. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(6):363–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sjölander P. What is known about the health and living conditions of the indigenous people of northern Scandinavia, the Sami? Glob Health Action 2011;4(1):8457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salvador-Carulla L, Amaddeo F, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, et al. Developing a tool for mapping adult mental health care provision in Europe: the REMAST research protocol and its contribution to better integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2015;15:e042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salvador-Carulla L, Canela J, Fernandez A, et al. Use of the European Classification of Services (DESDE-LTC) for integral mapping of mental health in Catalonia (Spain). Int J Integr Care. 2013;13(5):e15. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Research School of Population Health. Atlas of mental health care. [accessed 2020 Jun 3]. https://rsph.anu.edu.au/research/projects/atlas-mental-health-care.

- 21. Salvador-Carulla L, Alvarez-Galvez J, Romero C, et al. Evaluation of an integrated system for classification, assessment and comparison of services for long-term care in Europe: the eDESDE-LTC study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spijker BAV, Salinas-Perez JA, Mendoza J, et al. Service availability and capacity in rural mental health in Australia: analysing gaps using an integrated mental health Atlas. Aust New Zeal a J Psychiatry. 2019;53(10):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernandez A, Gillespie JA, Smith-Merry J, et al. Integrated mental health atlas of the Western Sydney Local Health District: gaps and recommendations. Aust Heal Rev. 2017;41(1):38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Furst MA, Salinas-Perez JA, Salvador-Carulla L. Organisational impact of the National Disability Insurance Scheme transition on mental health care providers: the experience in the Australian capital territory. Australas Psychiatry. 2018;26(6):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salinas-Perez JA, Salvador-Carulla L, Saldivia S, Pamela G, Alberto M, Cristina Romero LA. Integrated mapping of local mental health systems in Central Chile. Pan Am J Public Heal. 2018;42:e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ala-Nikkola T, Pirkola S, Kontio R, et al. Size matters—determinants of modern, community-oriented mental health services. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(12):8456–8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sadeniemi M, Almeda N, Salinas-Pérez JA, et al. A comparison of mental health care systems in Northern and Southern Europe: a service mapping study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fernandez A, Salinas-Perez JA, Gutierrez-Colosia MR, et al. Use of an integrated atlas of mental health care for evidence informed policy in Catalonia (Spain). Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(6):512–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McHugh C, Campbell A, Chapman M, Sivasankaran B. Increasing indigenous self-harm and suicide in the Kimberley: an audit of the 2005–2014 data. Med J Aust. 2016;205(1):33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campbell A, Chapman M, McHugh C, Adelln S, Sivasankaran B. Rising indigenous suicide rates in Kimberley and implications for suicide prevention. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24(6):561–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stanley SH, Laugharne JDE, Chapman M, Sivasankaran B. Kimberley Indigenous mental health: an examination of metabolic syndrome risk factors. Aust J Rural Health. 2016;24(5):300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Auclair G, Sappa M. Mental health in Inuit youth from Nunavik: clinical considerations on a transcultural, interdisciplinary, community-oriented approach. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(2):124–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boothroyd LJ, Kirmayer LJ, Spreng S, Malus M, Hodgins S. Completed suicides among the Inuit of northern Quebec, 1982–1996: a case–control study. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;165(6):749–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lessard L, Bergeron O, Fournier L, et al. Contextual study of mental health services in Nunavik. Québec, Canada: Institut national de santé publique du; 2008:34. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reibling N, Ariaans M, Wendt C. Worlds of healthcare: a healthcare system typology of OECD countries. Health Policy (New York). 2019;123(7):611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. Constitutional reform: creating a nation for all of us. Sydney, Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Radomiljac A, Davies C, Landrigan T. Health and wellbeing of adults in Western Australia 2014, overview and trends; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Organisations: online services report—key results 2016–17. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1071/PYv24n5-ED. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait ISLANDER Peoples 2015. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1071/nb99075. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farrer LM, Walker J, Harrison C, Banfield M. Primary care access for mental illness in Australia: patterns of access to general practice from 2006 to 2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salvador-Carulla L, Poole M, Gonzalez-Caballero JL, et al. Development and usefulness of an instrument for the standard description and comparison of services for disabilities (DESDE). Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(Suppl. 432):19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Montagni I, Salvador-Carulla L, Mcdaid D, et al. The refinement glossary of terms: an international terminology for mental health systems assessment. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2018;45(2):342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Furst MA, Bagheri N, Salvador-Carulla L. Forthcoming. 2020 An ecosystems approach to mental health services research. Br J Psychiatry Int. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Romero-López-Alberca C, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Salinas-Pérez JA, et al. Standardised description of health and social care: a systematic review of use of the ESMS/DESDE (European service mapping schedule/description and evaluation of services and directories). Eur Psychiatry. 2019:6197–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Furst MA, Reynolds J, Salinas-Perez J, et al. Atlas of mental health care of the Kimberley region (Western Australia). Kimberley, Western Australia: Australian National University and Western Australia Primary Health Alliance (WAPHA); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cetrano G, Salvador-Carulla L, Tedeschi F, et al. The balance of adult mental health care: provision of core health versus other types of care in eight European countries. Epidemiol Psych Sci. 2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kumar MB, Tjepkema M. Suicide among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit (2011-2016): findings from the 2011 Canadian Census health and environment cohort (CanCHEC); 2019:23. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Furst MA, Gandré C, Romero López-Alberca C, Salvador-Carulla L. Healthcare ecosystems research in mental health: a scoping review of methods to describe the context of local care delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. The Economist. Mental health and integration. Provision for supporting people with mental illness: a comparison of 30 European countries; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50. OECD. Health at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. Paris, France: OECD; 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1787/4dd50c09-en. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Garcia Armesto S, Medeiros H, Lihan W. Information availability for measuring and comparing quality of mental health care across OECD countries. Paris, France: OECD; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rezvyy G, Øiesvold T, Parniakov A, et al. The Barents project in psychiatry: a systematic comparative mental health services study between northern Norway and Archangelsk county. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(2):131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thornicroft G, Tansella M. The balanced care model for global mental health. Psychol Med. 2012;43(4):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Office of the Auditor General Western Australia. Western Australian Auditor General’s Report. Access to State- Managed Adult Mental Health Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sones R, Hopkins C, Manson S, et al. The Wharerata declaration—the development of indigenous leaders in mental health. Int J Leadersh Public Serv. 2010;6(1):53–63. [Google Scholar]

- 56. SANKS & Saami Council. Plan for suicide prevention among the Sámi people in Norway, Sweden and Finland. Karasjok, Norway: SANKS & Saami Council; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dudgeon P, Calma T, Brideson T, et al. The Gayaa Dhuwi (proud spirit) declaration—a call to action for aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership in the Australian mental health system. Adv Ment Health. 2016;14(2):126–139. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kirmayer LJ, Paul KW. Mental health, social support and community wellness. Québec, Canada; 2007:30. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Taylor A, Carson DB, Ensign PC, et al. (editors). Settlements at the edge: remote human settlements in developed nations. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2016:1–449. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.4337/9781784711962. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Supplement_material for Patterns of Mental Health Care in Remote Areas: Kimberley (Australia), Nunavik (Canada), and Lapland (Finland): Modèles de soins de santé mentale dans les régions éloignées: Kimberley (Australie), Nunavik (Canada) et Laponie (Finlande) by Jose A. Salinas-Perez, Mencia R. Gutierrez-Colosia, Mary Anne Furst, Petra Suontausta, Jacques Bertrand, Nerea Almeda PhD, John Mendoza, Daniel Rock, Minna Sadeniemi, Graça Cardoso and Luis Salvador-Carulla in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry