Abstract

Aims

To identify and categorise core components of effective stigma reduction interventions in the field of mental health in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and compare these components across cultural contexts and between intervention characteristics.

Methods

Seven databases were searched with a strategy including four categories of terms ('stigma’, ‘mental health’, ‘intervention’ and ‘low- and middle-income countries’). Additional methods included citation chaining of all papers identified for inclusion, consultation with experts and hand searching reference lists from other related reviews. Studies on interventions in LMICs aiming to reduce stigma related to mental health with a stigma-related outcome measure were included. All relevant intervention characteristics and components were extracted and a quality assessment was undertaken. A ‘best fit’ framework synthesis was used to organise data, followed by a narrative synthesis.

Results

Fifty-six studies were included in this review, of which four were ineffective and analysed separately. A framework was developed which presents a new categorisation of stigma intervention components based on the included studies. Most interventions utilised multiple methods and of the 52 effective studies educational methods were used most frequently (n = 83), and both social contact (n = 8) and therapeutic methods (n = 3) were used infrequently. Most interventions (n = 42) based their intervention on medical knowledge, but a variety of other themes were addressed. All regions with LMICs were represented, but every region was dominated by studies from one country. Components varied between regions for most categories indicating variation between cultures, but only a minority of studies were developed in the local setting or culturally adapted.

Conclusions

Our study suggests effective mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs have increased in quantity and quality over the past five years, and a wide variety of components have been utilised successfully – from creative methods to emphasis on recovery and strength of people with mental illness. Yet there is minimal mention of social contact, despite existing strong evidence for it. There is also a lack of robust research designs, a high number of short-term interventions and follow-up, nominal use of local expertise and the research is limited to a small number of LMICs. More research is needed to address these issues. Some congruity exists in components between cultures, but generally they vary widely. The review gives an in-depth overview of mental health stigma reduction core components, providing researchers in varied resource-poor settings additional knowledge to help with planning mental health stigma reduction interventions.

Key words: Discrimination, mental health, mental illness stigma, systematic reviews

Introduction

Mental health stigma: a global problem

The term ‘stigma’ encompasses people's knowledge, negative attitudes and behaviours toward (or by) a certain group or individual deemed ‘unacceptably different’ (Scambler, 1998; Thornicroft et al., 2009). This paradigm links knowledge, attitude and behaviour, and has also been defined as problems in three domains: ignorance, prejudice and discrimination (Thornicroft et al., 2008).

Mental health stigma has been shown to be widespread globally, regardless of region (Pescosolido et al., 2013). For example, a 2009 study found rates of experienced discrimination by people with schizophrenia were high and consistent across 27 countries (Thornicroft et al., 2009).

The far-reaching negative impact of mental health-related stigma and discrimination has been extensively documented and has even been described by those with mental illness as ‘worse than the illness itself’ (Henderson and Thornicroft, 2009). There is evidence of negative impacts of stigma across multiple domains of life – for example, stigma is associated with reduced employment opportunities and corresponding poverty, relationship difficulties, reduced help-seeking behaviour and poorer quality health care (Corrigan, 2004; Jones et al., 2008; Thornicroft et al., 2009; Knaak et al., 2017). Additionally, people with mental illness often experience severe human rights abuses and lack of freedoms, which act as barriers to social inclusion (Patel et al., 2018).

Mental health stigma and discrimination have been identified as major factors for low levels of investment and political will for reform in many countries, which in turn reduces access to care and contributes to excess morbidity and mortality for people with mental illness (Saraceno et al., 2007). Given its wide-ranging detrimental impact, it is important to address stigma urgently and effectively (Henderson and Thornicroft, 2009).

Stigma reduction interventions: state of the research

A substantial number of small-scale and short-term interventions have emerged in the past few decades focusing on reducing mental health stigma and several recent systematic reviews examine their effectiveness (Corrigan and Scott, 2012; Clement et al., 2013; Heim et al., 2018; Mehta et al., 2018; Mellor, 2018; Morgan et al., 2018).

Three overarching methods of reducing stigma have been conceptualised and tested in recent years: education (addressing myths and misconceptions), contact (direct or indirect interactions with people with the stigmatised condition) and protest (public demonstrations and campaigns against injustice) (Corrigan et al., 2001). The evidence indicates that there are a number of education and contact-based interventions which produce small to moderate effect sizes on stigma reduction, yet there is minimal evidence long-term and study quality is not always sufficient (Thornicroft et al., 2016; Gronholm et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2018). The protest method has not shown evidence of effectiveness (Corrigan et al., 2001).

A few studies have been conducted to identify key ingredients for very specific contexts or stigma types (Pinfold et al., 2005; Mittal et al., 2012; Corrigan et al., 2013, 2014; Knaak et al., 2014). While these studies have provided useful setting-specific evidence, there have been no systematic reviews which identify core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs or review their cultural variations. Similarly, there has been little research on how these components relate to other intervention factors – such as target population or type of stigma. A more detailed analysis would be helpful to understand what makes stigma reduction interventions effective in various contexts.

Investment by donor organisations for mental health has been noticeably increasing in high-income countries (HICs) over the past few years; for example, in January 2019 the Wellcome Trust announced £200 million in funding (Wellcome Trust, 2019). It is crucial that mental health researchers capitalise on this influx of support. In order to do so, they need to have sufficient evidence for how to design stigma reduction interventions both effectively and appropriately.

The scarcity of research into stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is consistent with the wider mental health research gap in resource-poor settings (Collins et al., 2011; Thornicroft et al., 2017; Alonso et al., 2018). For example, only four out of 62 studies included in a recent mental health stigma-related review were from LMICs (Morgan et al., 2018). Intervention transferability from HICs to LMICs is context-dependent and cannot be assumed; therefore, there still is a vast gap in knowledge surrounding what works in diverse cultural contexts and why (Mehta et al., 2018). Given this systematic review's wide scope, cultural differences will be examined between geographic regions as classified by the World Bank.

This systematic review aims to address the scarcity of stigma research in LMICs by identifying and categorising core components of effective mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs and comparing these components across cultures.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (ID 136008).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review included studies which contain interventions aiming to reduce any type of stigma related to mental health; this includes social/public stigma, self-stigma, anticipated, perceived, experienced stigma, or discrimination (see Table 1). Studies focusing on any other stigmatised condition were excluded, including HIV, neurological conditions, substance misuse and epilepsy. Interventions of all sizes, durations and effect sizes were included. There were no restrictions in terms of study participants. Inactive controls, treatment as usual controls and baseline assessments of intervention groups were all included, as long as outcome measures were taken before and after the intervention.

Table 1.

Definitions of types of stigma and discrimination

| Types of stigma | Definition |

|---|---|

| Social/public stigma | The prejudice and negative attitudes held by members of the public and/or society (Corrigan and Bink, 2005) |

| Self-stigma | Internalisation of prejudice and discrimination from social/public stigma (Corrigan and Bink, 2005) |

| Anticipated stigma | Expectations of bias from others (Stangl et al., 2019) |

| Perceived stigma | Perceptions of how the stigmatised group is treated by others (Stangl et al., 2019) |

| Experienced stigma | Experiences of being stigmatised by others (Stangl et al., 2019) |

| Discrimination | ‘The behavioural result of prejudice’ (Corrigan and Bink, 2005) |

All experimental designs were included, as long as they measured the effectiveness of stigma reduction interventions. To be included, interventions had to have been conducted in countries classified as LMIC by the World Bank (The World Bank, 2019). There were no publishing date restrictions. Following established frameworks on conceptualising stigma, studies had to include at least one measure of mental health-related stigma linked to knowledge, attitudes or behaviour (Corrigan and Scott, 2012; Thornicroft et al., 2016).

Search strategy

The database search strategy was developed using earlier stigma-related systematic reviews as a guide (Heim et al., 2018; Mehta et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2018; Kemp et al., 2019) and used both subject headings and keywords. Four categories of terms ('stigma’, ‘mental health’, ‘intervention’, ‘low- and middle-income countries’) were expanded with synonyms and related subject headings, connected within categories with ‘OR’ and between categories with ‘AND’. The full search strategy for MEDLINE, exemplifying this process, is provided within online Supplementary Material. Searches were restricted to English and Spanish, and to humans.

The following seven databases were searched on 13 May 2019: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Global Health, PsycINFO, EMBASE and Scopus.

Additional search methods comprised of citation checking, hand checking reference lists from other related systematic reviews on stigma, and experts in the field (NV, JE) were consulted to identify any missing papers or grey literature.

Study selection

All titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria by the lead author (JC), and 10% of titles and abstracts were screened by a second reviewer to establish consistency. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The study supervisor with knowledge of the review topic (NV) decided any on unresolved discrepancies.

Full-text versions of papers were retrieved for all potentially relevant studies and screened against the inclusion criteria. If the full text of a study was not available, the author was contacted. If there was no reply, the study was excluded. A third reviewer screened 10% of full-text papers.

Quality assessment

Assessment of quality and risk of bias across studies was conducted with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). This tool was chosen because multiple study designs were included in this review, and the MMAT has five unique criteria for each design in addition to two core criteria.

All studies marked for inclusion were assessed for quality and the third reviewer separately assessed 10% for consistency. For a study to be included, the two standardised core criteria had to be met. As recommended by the MMAT, studies of poor or very poor quality – two or less of five criteria met – were included in the main analysis but later separated out.

Data extraction

The framework for data extraction was developed a priori. Data was extracted on general study information (e.g. author, year), study characteristics (e.g. design, aims), study methods (e.g. methods of recruitment), intervention characteristics (e.g. intervention methods, dissemination medium), results (e.g. outcomes) and methodological quality. A full list of fields is provided in online Supplementary Material. Missing data was requested from authors where possible.

Data analysis

Only interventions which produced at least a partially positive effect for stigma-related outcomes were included in the main analysis. Ineffective interventions were described separately, to demonstrate how their components differed.

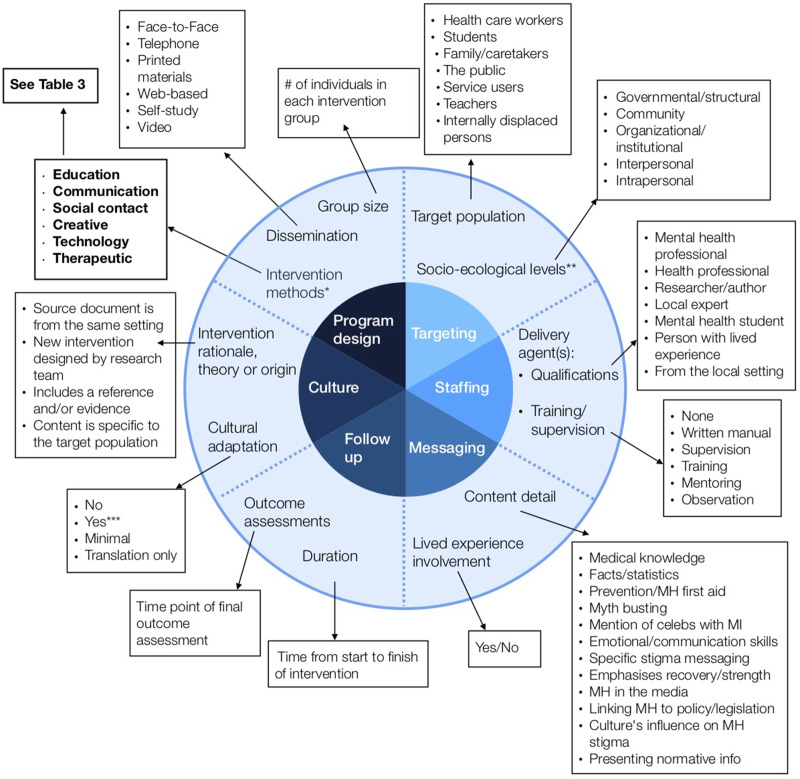

With previously conducted research and frameworks as a guide, a ‘best fit’ framework synthesis was chosen as the main method of analysis for this review (Carroll et al., 2013). As the most broadly encompassing framework, Corrigan's five categories of stigma reduction ingredients were the starting point for the synthesis: programme design, targeting, staffing, messaging and follow-up/evaluation. (Corrigan et al., 2013).

In order to address the cultural focus of this review, the sixth category of components was added: Culture. Data extraction fields related to this included: detail on the intervention rationale, theory or origin (where the content came from), as well as whether the publications mention any kind of cultural adaptation or taking account of local beliefs. This data helped determine the influence of culture on the intervention and provide detail on transferability. World Bank regions were also analysed individually, in order to describe differences in components by region.

Data was extracted from each study based on the authors' literal descriptions in the publications, without a priori labels. A codebook was then created for each data extraction worksheet field, grouping information within the categories using inductive thematic analysis grounded in the extracted data. The framework synthesis then allowed for the expansion of Corrigan's categories (Carroll et al., 2011) and the creation of a new framework (see Fig. 2). A narrative synthesis was used to explain the coded data. The final overview of components therefore only included those which the publication reported on.

Fig. 2.

Framework of core components of anti-stigma interventions in low- and middle- income countries. The inner circle represents six overarching ‘categories’; the outer circle represents ‘components’ within each category; the boxes represent ‘sub-components’ within each component. Intervention methods are further broken down into ‘elements’ in Table 3. This framework of core components of anti-stigma interventions was developed by the authors as a composite of other analysis frames (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, 2006; Corrigan et al., 2013). *Intervention methods: the six sub-components are further coded into 32 elements; see Table 3. **Socio-ecological levels: based on Heijnders' framework (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, 2006). ***Cultural adaptation: ‘yes’ = local beliefs/culture are taken into account; the intervention at least partially originated from the local context; or, the intervention was piloted/field-tested

Results

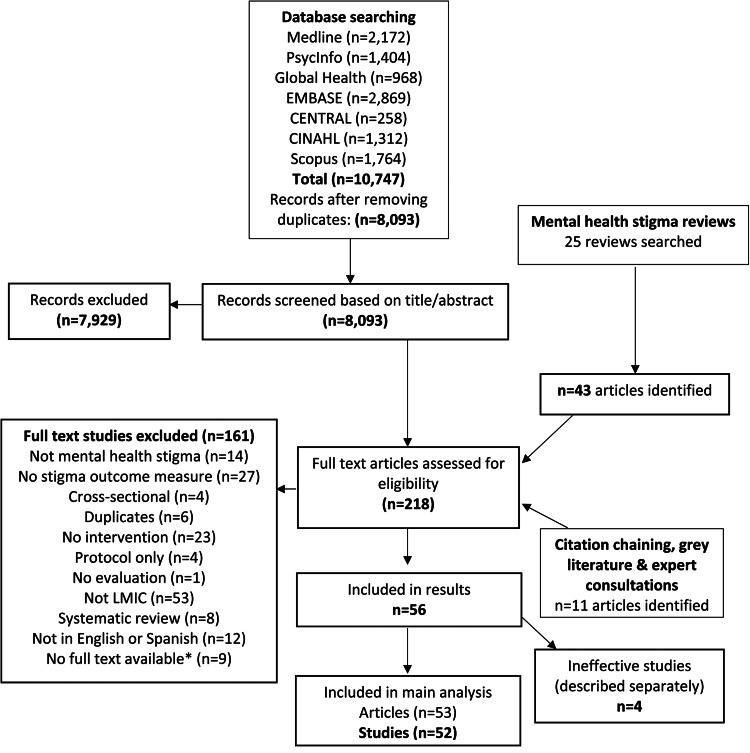

Search results

The final search produced 56 studies (57 articles) which were deemed eligible for inclusion (see Fig. 1). Four studies were ineffective and analysed separately, to demonstrate how their components differed.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of selection of articles and sources included in the review. *Authors contacted with no response

Study characteristics

See Table 2 for key characteristics of each study.

Table 2.

Key characteristics and components of included studies

| Author (year)a | Study design | Country | Target popb | Target condition (type)c | nd | % complete outcome data | Duration | Overall qualitye | Intervention methodsf | Content detail | Lived exp | Cultural adaptation | Follow-up time pointsg | Outcome measure(s) focal point(s) (validation)h | Overall effectiveness for stigma-related outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abayomi et al. (2013) | Pre/post | Nigeria | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 60 | 51% | 6 weeks | Moderate | L/P, Train | Medical | No | Translation only | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Adelekan et al. (2001) (–) | Pre/post | Nigeria | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 43 | 62% | No info | Poor | L/P, Train | Medical, Prevention | No | No | End only | Attitudes | No evidence of effectiveness |

| Ahuja et al. (2017) | Pre/post | India | Students | Mental health (SP) | 50 | 100% | 1 session | Moderate | L/P, T/D, Disc | Myths, Celebs, Strength | Yes | Yes | End; 1 week after | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Altindag et al. (2006) | Non-randomised trial | Turkey | Students | Schizophrenia (SP) | 60 | 77% | 1 day | High | L/P, Disc, DSC, Film | Medical, Myths, Strength | Yes | No | End; 1 month after | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Amaresha et al. (2018) | Non-randomised trial | India | F/C | Schizophrenia (SE) | 80 | 78% | Unclear | High | L/P, Disc | Medical, Emotional | Yes | Yes | End; 1 month; 3 months after | Knowledge(*); Self-stigma(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Amna et al. (2016) | Non-randomised trial | Indonesia | Students | PTSD (SP) | 121 | Unknown | No info | Poor | L/P, SS, Disc | Medical, Facts | No | No | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Armstrong et al. (2011) | Pre/post | India | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 70 | 94.30% | 4 days | High | L/P, Train, Role | Facts, Medical, MHFA, Stigma | No | No | End; 3 months after | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Very small positive effect; mixed results |

| Ayano et al. (2017) | Pre/post | Ethiopia | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 94 | 100% | 5 days | Moderate | L/P, Vid | Medical | No | No | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Ayonrinde et al. (1976) (–) | Pre/post | Nigeria | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 72 | Unknown | No info | Very poor | L/P, Disc | Medical | No | No | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | No evidence of effectiveness; had a negative effect |

| Bella-Awusah et al. (2014) | Non-randomised trial | Nigeria | Students | Mental health (SP) | 154 | 94% | 1 session | High | L/P, Disc, | Facts, Medical, Stigma, Media | No | Yes | End; 6 months after | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Significant effect for knowledge, but not attitudes/social distance |

| Berlim et al. (2007) | Pre/post | Brazil | HCW | Suicide (SP) | 142 | 100% | 1 session | Moderate | L/P, Train, Disc | Facts, Medical | No | No | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Bosoni et al. (2017) | Pre/post | Brazil | Public | Schizophrenia (SP) | 48 | 57% | 1 session | Poor | Vid | Facts, Medical, Stigma, Recovery | No | Yes | End; 1 month; 3 months after | Stereotyped views(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Botega et al. (2007) | Pre/post | Brazil | HCW | Suicide (SP) | 317 | 80% | 2 sessions (unclear) | Moderate | L/P, Disc, RA, Train | Stigma, Facts, Medical | No | Translation only | End; 3 months; 6 months after | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect for 2/3 subscales |

| Chinnayya et al. (1990) | Pre/post | India | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 150 | 100% | 1 week | High | L/P, Case, Role | No content detail | No | Translation only | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Cuhadar et al. (2014) | Individual RCT | Turkey | SU | Bipolar (SE) | 63 | 74% | 7 weeks | Moderate | L/P, Disc, Share | Medical, Facts, Stigma | Yes | No | End only | Self-stigma(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| da Silva et al. (2011) | Pre/post | Brazil | HCW | Suicide (SP) | 230 | 58% | Unclear | Poor | L/P, Disc, Case, Share | Medical, Facts, Stigma, Prevention | No | Minimal | End only | Attitudes(*); Knowledge | Yes, significant effect |

| Demiroren et al. (2016) (–) | Non-randomised trial | Turkey | Students | Mental health (SP) | 190 | 95% | 2 sessions (unclear) | High | Reflect | No additional content | No | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*) | No evidence of effectiveness |

| Dharitri et al. (2015) | Pre/post | India | Public, F/C | Mental health (SP) | 1112 | 94% | Unclear | High | L/P, Poster, Q&A, Print, T/D | Medical, Myths, Stigma | No | Yes | In 1st month of intervention; 3 months after | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Domínguez-Martinez et al. (2017) | Pre/post | Mexico | F/C | Mental health (SP) | 291 | 79% | 12 weeks | Moderate | L/P, Disc | Recovery, Medical, Emotional, Strength | Yes | Minimal | End only | Knowledge(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Duman et al. (2017) | Non-randomised trial | Turkey | Students | Mental health (SP) | 256 | 78% | 2-3 months | Poor | L/P, Disc, Film, Obs, DSC | Stigma | Yes | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| El-Nahas et al. (2018) | Individual RCT | Egypt | F/C | Schizophrenia (SP) | 60 | 83% | 6 months | High | L/P, Disc, Train | Medical, Emotional | No | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*); Knowledge(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Fernandez et al. (2016) | Individual RCT | Malaysia | Students | Mental health (SP) | 102 | 100% | 1 day | High | L/P, DSC, VSC | Medical, Facts, Stigma, Myths, Recovery | Yes | No | End; 1 month after | Attitudes & Behaviour(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Finkelstein et al. (2008) | Individual RCT | Russia | Students | Mental health (SP) | 193 | 79% | 1 session | Moderate | L/P, Quiz, SSC | Myths, Medical, Facts, Recovery, Strength | No | No | End; 6 months after | Attitudes(*); Attitudes(*); Knowledge(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Goyal et al. (2013) | Pre/post | India | Students | Depression (SP) | 100 | 95% | 1 session | Moderate | Facts, Medical, Myths | No | Yes | 1 week after baseline only | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Significant effect for knowledge, but not attitudes | |

| Hofmann-Broussard et al. (2017) | Pre/post | India | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 56 | 100% | 4 days | High | L/P, Disc, DSC | Facts, Medical, Recovery | Yes | No | End only | Knowledge(*); Attitudes(*) | Significant effect for psychosis, but not depression |

| Iheanacho et al. (2014) | Pre/post | Nigeria | Students | Mental health (SP) | 83 | 69% | 4 days | Poor | L/P, Disc, Role | Medical, Facts | No | No | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Keynejad et al. (2016) | Mixed methods pre/post | Somaliland (SL) | Students | Mental health (SP) | 20 SL (24 UK) | 39% | 20 weeks | High | Web, Forum, L/P, IM | Medical, Culture, Facts | No | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*); Attitudes(*) | Yes, for SL students (not UK students) |

| Kutcher et al. (2015) | Pre/post | Malawi | Teachers | Mental health (SP) | 218 | 88% | 3 days | Moderate | Train, Disc | Facts, Medical, Stigma | No | Yes | End only | Knowledge(*); Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Kutcher et al. (2016) | Pre/post | Tanzania | Teachers | Mental health (SP) | 61 | 62% | 3 days | Very poor | L/P, SS, Disc | Stigma, Medical, Facts, Recovery | No | Yes | End only | Knowledge(*); Attitudes(*); Knowledge(*) | Significant effect for knowledge and attitudes, but not comfort levels |

| Li et al. (2014) | Pre/post | China | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 99 | 90% | 1 day | Moderate | L/P, Train, Share | Medical, Stigma | No | No | End only | Knowledge; Behaviour(*); Attitudes(*) | Significant effect for discrimination and attitudes, but not for knowledge |

| Li et al. (2018) | Cluster RCT | China | SU | Schizophrenia (SE) | 384 | 84% | 9 months | Moderate | L/P, Train, Disc, CBT | Medical, Facts, Emotional, Stigma | Yes | Yes | 6 months into intervention; at end | Internalised stigma(*); experienced stigma(*) | Significant effect for anticipated discrimination and overcoming stigma, but not self-stigma |

| Li et al. (2019) | Cluster RCT | China | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 384 | 76% | 1 session | Poor | L/P, Train | Stigma, Recovery | No | No | End only | Perceived discrimination(*); Attitudes(*); Knowledge(*) | Significant effect for perceived discrimination and attitudes, but not knowledge |

| Makanjuola et al. (2012) | Pre/post | Nigeria | Teachers | Mental health (SP) | 24 | Unknown | 5 days | Very poor | L/P, Train, Disc, Role, Vid | Medical, Facts, Emotional, Policy | No | No | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes | Yes, significant effect |

| Maulik et al. (2017, 2019) | Mixed methods pre/post | India | Public | Mental health (SP) | 1576 | 73% | 3 months | Moderate | Public, Print, DiscPub, Disc, VSC, Vid, T/D | Medical, Stigma | Yes | Yes | End; 2 years after baseline | Knowledge & Attitudes & Behaviour(*) | End: Significant effect for attitudes and behaviour, but not knowledge 2 years: Yes, significant effect |

| Mutiso et al. (2019) | Pre/post | Kenya | HCW, SU | Mental health (SE) | 2305 | 59% | 5 days | High | L/P, Train, Case, Disc, Role | Medical, Stigma | Yes | Yes | 6 months after | Experienced stigma(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Ng et al. (2017) | Pre/post | Malaysia | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 206 | 99% | 1 session | High | Vid | Stigma, Myths, Celebs, Strength, Recovery, Facts | Yes | Translation only | End only | Attitudes & Behaviour(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Ngoc et al. (2016) | Individual RCT | Vietnam | SU | Schizophrenia (SE) | 59 | 81% | 1-2 weeks | Moderate | L/P, Disc | Medical, Stigma, Recovery, Emotional | Yes | Yes | 6 months after enrolment only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Oduguwa et al. (2017) | Individual RCT | Nigeria | Students | Mental health (SP) | 205 | 66% | 3 days | Moderate | L/P, Disc, Role | Facts, Medical, Stigma | No | No | End; 3 weeks after | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Significant effect for knowledge, but not for attitudes or social distance |

| Pejovic-Milovancevic et al. (2009) | Pre/post | Serbia | Students | CAMH (SP) | 63 | 100% | 6 weeks | Poor | L/P, Disc, WS | Facts, Medical, Stigma, Myths | No | No | 6 months after | Attitudes | Yes, significant effect |

| Pereira et al. (2015) | Cluster RCT | Brazil | Teachers | CAMH (SP) | 176 | 65% | 3 weeks | Moderate | Web, L/P, Vid, Print, WC | Medical, Myths, Stigma | No | Yes | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes | Significant effect for knowledge and stigmatised concepts, but not attitudes |

| Rahayuni et al. (2013) | Non-randomised trial | Indonesia | F/C | Schizophrenia (SP) | 38 | 97% | 2.5 weeks | High | L/P, BS, Case, Role, Disc, Print, Vid | No content detail | No | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Rahman et al. (1998) | Cluster RCT | Pakistan | Students, Public | Mental health (SP) | 100 | 100% | 6 months | High | L/P, Disc, T/D | Facts | No | Yes | 4 months after baseline only | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Ran et al. (2003) | Cluster RCT | China | F/C | Schizophrenia (SP) | 357 | 91% | 9 months | High | L/P, Disc, WS, Share, Train | Facts, Emotional | Yes | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Ravindran et al. (2018) | Non-randomised trial | Nicaragua | Students | Mental health (SP) | 913 | 67% | 12 weeks | High | Web, Vid, Share, L/P, Disc | Stigma, Facts, Medical | No | Yes | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Rong et al. (2011) | Cluster RCT | China | Students | Depression (SP) | 205 | Unknown | 10 days | Moderate | L/P, Disc, BS, DiscPub, Art, Vid | Medical, Facts, Policy, Celebs, Strength | Yes | Yes | 2 weeks; 1 month; 6 months (after baseline) | Knowledge & Attitudes(*); Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Sadik et al. (2011) | Pre/post | Iraq | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 317 | 100% | 2 weeks | High | L/P, Disc, Train, Role, Vid, Visits, CD, Print | Medical, Policy | Yes | Yes | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes & Behaviour(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Sanhori et al. (2019) (-) | Pre/post | Sudan | IDP | Mental health (SP) | 1549 | 82% | 1 session | High | L/P, Q&A, Disc, T/D | Facts, Medical, Recovery, Stigma | No | No | 1 year after baseline only | Attitudes(*) | No evidence of effectiveness |

| Shah et al. (2015) | Pre/post | India | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 150 | Unknown | 2 years | Poor | Train, Disc, Role, DSC, Obs, Quiz | Facts, Medical | Yes | No | End only | Knowledge & Attitudes | Yes, significant effect |

| Shamsaei et al. (2018) | Pre/post | Iran | F/C | Mental health (SP) | 43 | 100% | 1 day | Poor | L/P, Print, Share, Disc | Stigma, Medical | No | No | 1 week after | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Sibeko et al. (2018) | Mixed methods pre/post | South Africa | HCW | Mental health (SP) | 58 | 69% | 8 sessions (unclear) | High | L/P, Disc, Reflect | Culture, Medical | No | Yes | End; 3 months after | Knowledge(*); Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Tong et al. (2019) | Individual RCT | China | SU | Depression (SE) | 90 | 97% | 8 weeks | High | GCBT | Facts, Emotional, Stigma | Yes | No | End only | Stigma- no further detail(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Ucok et al. (2006) | Pre/post | Turkey | HCW | Schizophrenia (SP) | 106 | 50% | 1 session | Very poor | L/P, Disc, Print | Medical, Stigma | No | No | 3 months after | Attitudes | Significant effect for 5/16 items; mixed results |

| Vaghee et al. (2015) | Cluster RCT | Iran | F/C | Schizophrenia (SE) | 90 | 93% | 4 days | High | Film, Disc, L/P, Q&A | Emotional, Recovery, Facts | Yes | No | 1 month after | Internalised stigma(*) | Yes, significant effect |

| Worakul et al. (2007) | Pre/post | Thailand | F/C | Schizophrenia (SP) | 91 | 100% | 1 day | Poor | L/P, Disc, Film | Medical, Emotional | No | Yes | End only | Knowledge; Attitudes | Yes, significant effect |

| Yan et al. (2018) | Individual RCT | China | Students | Anorexia nervosa (SP) | 76 | Unknown | 2 sessions (unclear) | Poor | Case, Web | In/Out-group | No | Yes | End only | Attitudes(*) | Yes, significant effect for in-group |

| Yılmaz et al. (2018) | Non-randomised trial | Turkey | SU | Schizophrenia (SE) | 80 | 86% | 6 weeks | High | Train, L/P, Role, Share | Emotional, Facts, Medical, Stigma | Yes | No | End only | Internalised stigma(*) | Yes, significant effect |

Note: Studies with a ‘(–)’ in the first column after the author's name were ineffective for stigma-related outcomes and excluded from the main analysis.

Year, year of publication.

Target population: HCW, health care worker; F/C, family/caregiver; Public, the general public; SU, service user; IDP, internally displaced persons.

Target condition (type): SP, stigma practices (expressed by those perpetuating stigma); SE, Stigma experiences (those felt by the stigmatised individual); CAMH, child and adolescent mental health; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

N, number of participants at baseline.

Study quality was based on the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Intervention methods: see Table 3 for component codes.

Follow-up time points: after baseline. End = immediately after intervention; after = after the end of the intervention.

Outcome measure focal points = what are study outcome measures looking at as a proxy for stigma. Validation: (*) = measure is validated in some way; no ‘(*)’ = measure was developed ad hoc by authors with no validation OR no info given. One measure which addresses more than one focal point connects with ‘&’; two separate measures are indicated with ‘;’. Full names/descriptions of measures available upon request.

The quality of studies varied, with 38 studies (73%) fulfilling at least three of five MMAT quality criteria (considered moderate and high-quality studies). Eleven studies (21%) were of poor quality with one to three of criteria fulfilled, and three (6%) were of very poor quality (i.e. no criteria fulfilled).

The majority of studies were conducted in East Asia and Pacific (n = 13, 25%) or Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 11, 21%), but all World Bank regions were represented apart from North America, due to the review's LMIC restriction. Studies took place in 24 countries overall. Only two studies were published prior to 2000, and about half (n = 26) have been published since 2016; 12 were published in 2018 or 2019. Almost a third of studies (n = 15, 29%) were individual or cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 11 of these (73%) were published since 2014. The majority of studies (n = 27, 52%) were pre/post studies.

Most studies (n = 29, 56%) targeted general mental health stigma. Twelve studies looked at schizophrenia, three studies focused on suicide, three on depression, two on child and adolescent mental health, and one each on bipolar disorder, anorexia nervosa and post-traumatic stress disorder.

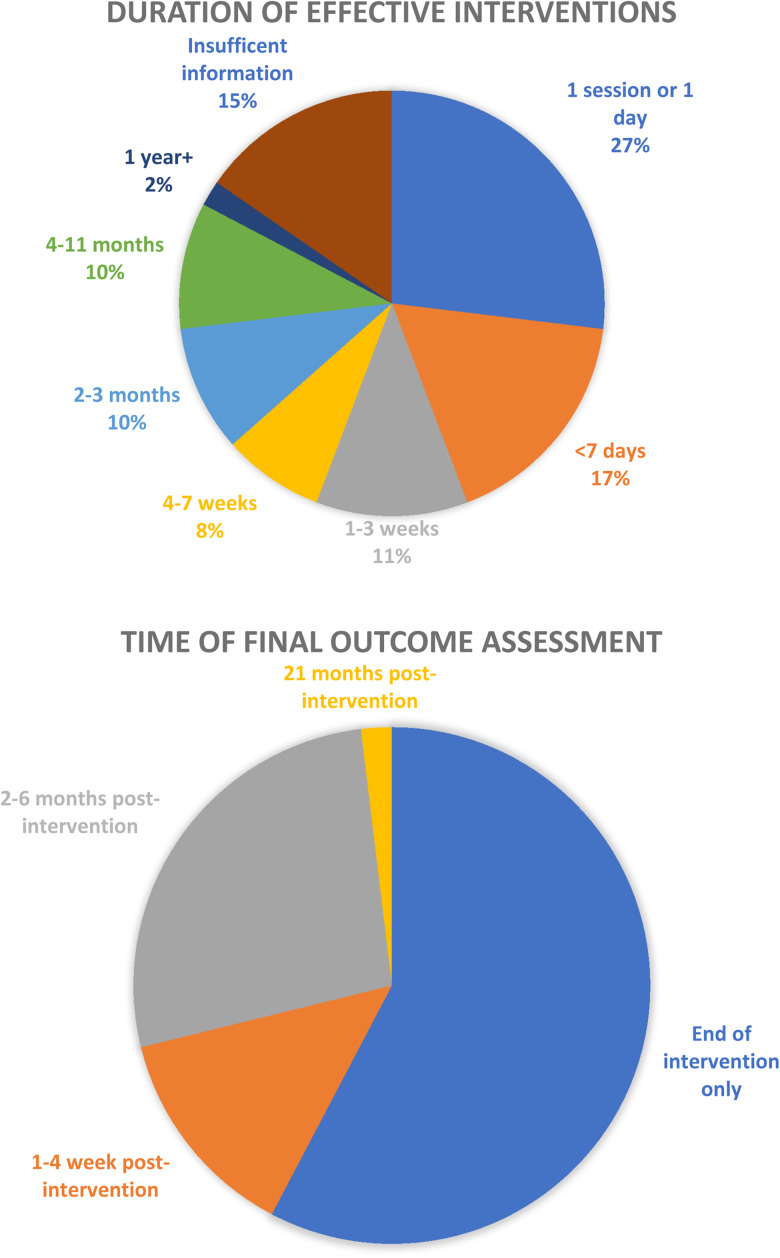

The majority of studies (n = 30, 58%) had their final outcome assessment directly at the end of the intervention, but 14 of these had an intervention duration of 4 weeks or longer. Fifteen (29%) followed up after 2 months or longer. Thirty-nine articles (74%) found a significant positive result for all main stigma outcomes and 13 (25%) found at least a small positive result for some but not all stigma outcomes. Of these 13, ten lasted less than a week.

Among the moderate or high-quality studies (n = 38), 14 (37%) followed up at least 1 month after the intervention finished and ten of these (71%) still found a significant positive effect on stigma outcomes at the later final assessment, indicating that it is possible to maintain stigma reduction over the medium term.

Intervention components and categorisation

From the best-fit framework synthesis, the categorisation of components was developed into a new framework (see Fig. 2) which was used to organise and analyse extracted data. This produced six categories of components: programme design, targeting, staffing, messaging, follow-up and culture, described in further detail below. Full data is available upon request.

Programme design

The programme design category captured group size, dissemination and intervention method components. As the quantity and variety of intervention method sub-components identified through thematic analysis was vast, these were further organised into ‘elements’ (see Table 3). Most studies (n = 49, 94%) utilised at least one educational component and only eight did not include the most common element, ‘lectures/presentations’. Almost all (n = 48, 92%) reported using more than one element and 20 studies (38%) used four or more intervention method elements.

Table 3.

‘Intervention methods’ sub-components and elements used in anti-stigma interventions in low-and middle-income countries

| Intervention methods sub-components | Elements | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Lectures/presentations | L/P |

| Training | Train | |

| Case studies | Case | |

| Printed material | ||

| Quiz | Quiz | |

| Self-study | SS | |

| Public campaign | Public | |

| Visits to mental health units | Visits | |

| Observation | Obs | |

| Communication | Discussion | Disc |

| Reflection | Reflect | |

| Sharing of experiences | Share | |

| Posters | Poster | |

| Q&A | Q&A | |

| Workshop | WS | |

| Discussions with the public | DiscPub | |

| Brainstorming strategies | BS | |

| Social contact | Direct social contact | DSC |

| Simulation of social contact | SSC | |

| Video of social contact | VSC | |

| Creative | Film screening | Film |

| Roleplay | Role | |

| Theatre/dance | T/D | |

| Art | Art | |

| Technology | Videos | Vid |

| CDs | CD | |

| Website | Web | |

| Web forum | Forum | |

| Web conference | WC | |

| Instant messaging | IM | |

| Therapeutic | CBT | CBT |

| Group CBT | GCBT |

Across all studies, as shown in Table 3, educational sub-components were documented most frequently as a method (n = 83), followed by communication (n = 58), technology (n = 21), creative (n = 19), social contact (n = 8) and therapeutic (n = 3). As for group size, the majority were between 11 and 29 (n = 15, 29%) and between 30 and 99 (n = 8, 15%) or it was unclear/unreported (n = 21, 40%). Of the 39 interventions effective for all stigma outcomes, only one described using educational methods only, and just 14 (36%) used solely education and communication methods.

Targeting

The most frequent target populations were health care workers and students (both n = 16, 31%), although some studies focused on more than one group.

Staffing

The most common delivery agents were mental health professionals (MHP) (n = 23, 44%). Of these, only six explicitly mentioned that the MHP came from inside the setting where the research took place. Two (4%) defined at least one of their delivery agents as someone with lived experience. Of the total, 54% of studies (n = 28) did not mention any delivery agent training or supervision.

Messaging

The content of messaging did vary, but most interventions (n = 42, 81%) described their intervention as being based on medical knowledge, and only half of the studies (n = 26) explicitly mentioned stigma or discrimination in their description. While this does not necessarily indicate that a discussion of stigma was excluded from the other 26 interventions, it was not reported. A variety of other themes were addressed in smaller numbers including teaching emotional/communication skills (n = 11); myth-busting (n = 9); emphasising recovery and strength of people with mental illness (n = 13); and discussing the media's impact on stigma (n = 4).

Twenty-one studies (40%) involved someone with lived experience in the intervention development or delivery. This is in contrast to educational methods, which were used in almost all interventions (94%). No interventions reported using the protest as a method.

Of the 21 studies which involved someone with lived experience in intervention development or delivery, 86% were effective for all stigma-related outcomes compared to only 74% of studies which did not involve someone with lived experience. Of these 21, 15 incorporated emotional skills or emphasised recovery/strength of people with mental illness. In comparison, only five of the 31 studies which did not involve someone with lived experience incorporated emotional skills or emphasised recovery/strength.

Follow-up

Approximately a quarter of interventions (n = 14) lasted for one session or 1 day only. Nine (16%) lasted for less than a week, six (10%) lasted between 1 and 3 weeks, and fifteen (29%) lasted 4 weeks or longer. The majority of studies (n = 30, 58%) had their final outcome assessment directly at the end of the intervention. However, of these 30, 14 interventions lasted 4 weeks or longer (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Duration of effective interventions and length of follow-up.

Culture

Only 11 studies (21%) originated from ‘inside’ the setting (the source document for the intervention originated from the same setting it was used in) and were referenced (meaning the publication provided a cited resource for the intervention). Twelve studies (23%) were either ‘outside’ or new, had no reference and were not targeted/provided no targeting information. Thirty-five studies (67%) included a reference or evidence for their intervention. Thirty-two studies (62%) used interventions which originated ‘outside’ the country (such as source documents from the World Health Organisation) or did not provide information. Twenty-five studies (48%) were culturally adapted.

Only four of 52 studies (8%) took place in low-income countries; 21 (40%) took place in lower-middle-income countries and the remaining 27 (52%) took place in upper-middle-income countries. Given the geographic variety of results and as most regions were dominated by one country, analysis of components between World Bank regions was deemed an appropriate perspective on whether components vary between cultures.

Key intervention components did vary across regions (see Table 4). East Asia and Pacific had the highest number and percentage of: RCTs (n = 8, 62% of 13 studies) and interventions using emotional skills or emphasising recovery (n = 10, 76%). The region only utilised social contact in one study, however.

Table 4.

Study components by geographical region

| Region | na | Study design | Target population | Average sample size at baseline | Intervention duration (where known) | Overall quality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre/postb | RCT | Non-randomised trial | Mixed methods | Health care workers | Students/ teachers | Family, caregivers, service users | The public | <1 week | 1–4 weeks | >4 weeks | Poor/very poor | Moderate/high | |||

| East Asia and Pacific | 13 | 3 (23%) | 8 (62%) | 2 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (23%) | 4 (31%) | 6 (46%) | 0 (0%) | 170 | 5 (38%) | 3 (23%) | 3 (23%) | 4 (31%) | 9 (69%) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 11 | 7 (64%) | 1 (9%) | 1 (9%) | 2 (18%) | 4 (36%) | 6 (55%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 298 | 8 (73%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) | 3 (27%) | 8 (73%) |

| South Asia | 10 | 7 (70%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (20%) | 344 | 4 (40%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (30%) | 1 (10%) | 9 (90%) |

| Europe and Central Asia | 7 | 2 (29%) | 2 (29%) | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14%) | 4 (57%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 117 | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (57%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 7 | 5 (71%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (43%) | 2 (28%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) | 302 | 2 (29%) | 1 (14%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) |

| Middle East and North Africa | 4 | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 0 (0%) | 128 | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) |

Number of studies per region.

Percentages are out of total studies in each region.

Lived exp = involving someone with lived experience in intervention development/delivery.

Reference/evidence of source = the origin of the intervention is referenced/evidence.

Sub-Saharan Africa had the lowest number and percentage of RCTs (n = 1, 9% of 11 studies), of interventions lasting longer than a week (n = 2, 18%), of interventions using emotional skills or emphasising recovery (n = 2, 18%), or involving someone with lived experience (n = 1, 9%). This region did have a good number of moderate and high-quality studies (n = 8, 73%), but no interventions featured social contact. This region also had the highest number of interventions whose source was referenced or evidenced (n = 9, 82%).

South Asia had the highest percentage of moderate or high-quality studies, at 90%. Europe and Central Asia had the most interventions lasting more than 1 month (n = 4, 57%). All regions were dominated by studies from one country: China (n = 7), India (n = 9), Nigeria (n = 5), Turkey (n = 5), Iran (n = 2) and Brazil (n = 5); combined they made up 63% (n = 33) of all effective studies.

Ineffective studies

Only four (7%) of the 56 studies reported in Table 2 did not find any evidence of effectiveness and two were of poor or very poor methodological quality. These ineffective interventions did not use any social contact, technological or therapeutic methods. Two of the four provided no information on either delivery agents or their training/supervision and only one included explicit messaging on stigma or recovery. None involved someone with lived experience and only one was culturally adapted.

Discussion

Overall, the vast majority of included studies were effective in reducing mental health stigma to some degree, at least in the short term, which is consistent with previous findings (Gronholm et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2018).

There is some congruity in components between cultures, but generally, they vary widely and may reflect various cultural differences within the local setting. The generalisability of regional results to the wider World Bank regions is limited, as results were dominated by studies from one country in each region (China, India, Nigeria, Turkey, Iran and Brazil). Few studies originated from the local setting and were referenced and less than half met the criteria to be considered culturally adapted. This assumption of transferability between settings by some studies disregards the importance of cultural relevance (Drake et al., 2014; Rathod and Kingdon, 2014) and evidence that local concepts of stigma are complex (Weiss et al., 2001).

Despite evidence of the effectiveness of social contact (Corrigan and Scott, 2012), no region overtly described using social contact in more than half of studies and almost no studies defined any of their delivery agents as someone with lived experience. Nonetheless, it is possible that social contact was more frequently used and included in other intervention components, such as through lectures and presentations. However, if not explicitly mentioned, it was unable to be reported here.

The results of this review also indicate that more complex interventions (i.e. interventions including more unique individual methodological sub-components and elements) are not necessarily more effective. Almost all studies used self-report measures and had limited length of follow-up, which reflects the complexity of measuring real-life discrimination experience, hence use of, for example, intended behaviour as proxies.

The results of this systematic review reiterate some main findings from other recent stigma-related reviews (Thornicroft et al., 2016; Heim et al., 2018; Mehta et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2018; Heim et al., 2019). However, these reviews also found minimal research in LMICs, limited cultural adaptation, short intervention duration, poor study quality and mostly only short-term follow-up. Yet in comparison, this review found a higher number of effective studies with more than a 4-week follow-up, the majority of which were of moderate or high quality and more studies which originated from inside the local setting. The majority of papers included here have been published since 2014. This indicates that the overall quantity and quality of stigma reduction studies has increased over the past several years.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review providing an in-depth analysis of core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs.

The relatively large number of included studies provides a thorough analysis of intervention components and the use of an explicit evidence-based framework allows for more definitive conclusions on the makeup and distribution of various intervention components in LMICs and within specific regions. This review also includes an emphasis on interrogating culture and adaptation, which is valuable given the importance of cultural understanding. Although there were a large number of non-randomised trials and pre/post studies, this review included a higher percentage of RCTs than previous reviews in LMICs, improving the overall quality of results.

One limitation was only including studies with full-texts in English or Spanish, the languages spoken of the author. The components reported here were selected based on criteria established through the framework synthesis, but detailed analysis of additional study characteristics would be useful and interesting. Additionally, studies without full-texts available were excluded and only two authors replied to full-text requests.

Core components were extracted and included only if they were explicitly reported in the publication and although authors were contacted whenever possible for further detail most did not reply. Additionally, more than half the studies were pre/post studies without a control group, increasing the possibility of bias and a quarter of studies were of poor or very poor quality. Regarding stigma reduction measures, although evidence surrounding knowledge gain as a proxy for stigma is mixed (Stuart, 2016), interventions solely measuring knowledge gain were included (n = 1) as per a reflection of the existing stigma literature. Further research is needed to understand what aspects of knowledge-based interventions impact stigma and how. The generalisability of the region-specific analysis was reduced by the fact that each region's studies were dominated by a single country. Finally, the small number of ineffective studies suggests that there may be publication bias in this area of research.

Implications and recommendations

The vast amount of extracted data for this review, organised into 106 detailed components, sub-components and elements, should provide other researchers with a useful starting point for designing and analysing mental health stigma reduction interventions.

Given that the majority of stigma research focuses on HICs, understanding what has worked in varied low-resource settings would be essential when developing effective stigma reduction interventions in LMICs, for example when using creative methods such as theatre, dance and web-based interventions.

More research needs to be conducted in a wider variety of countries, and interventions need to be developed using local expertise and be culturally adapted. Due to its proven effectiveness (Gronholm et al., 2017), social contact should be actively incorporated into stigma reduction interventions.

Conclusion

This systematic review found many and varied stigma reduction programmes with effective intervention components in LMICs. Most included studies described interventions based on educational methods, along with themes of medical knowledge surrounding mental health, teaching emotional/communication skills, myth-busting, emphasising recovery and discussing the media's impact on stigma. Yet there are minimal descriptions of social contact, despite the fact that it has been shown to be the most impactful single component of stigma reduction work (Thornicroft et al., 2016). This may be due to lack of knowledge about the state of evidence around contact interventions, lack of influence and opportunity for groups of people affected to be included, or stigma itself.

Although to date only a minority of studies were developed, evidenced or culturally adapted in the local setting, the overall quantity and quality of studies has increased over the past several years. If the best evidence was available to groups working to combat stigma globally, it is likely that the important benefits of these efforts to promote inclusion and reduce stigma and discrimination would be amplified, and more people in need would seek and get access to mental health care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sarah Devos and Thomas Elsmore for their help reviewing the data during the study selection phase.

Financial support

N.V. is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (grant number ES/J500057/1) and the INDIGO Medical Research Council (MRC) Partnership Grant (grant number MR/R023697/1). The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. PCG is funded by the INDIGO Medical Research Council (MRC) Partnership Grant (grant number MR/R023697/1). MS is funded through the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Neglected Tropical Diseases at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, using Official Development Assistance (ODA) funding.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review, as confirmed in a letter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Governance & Integrity Office dated 24 April 2019.

Availability of Data and Materials

For access to all data supporting this study, please email Jennifer Clay: jeclay3@gmail.com.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000797.

click here to view supplementary material

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Abayomi O, Adelufosi A and Olajide A (2013) Changing attitude to mental illness among community mental health volunteers in south-western Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry 59, 609–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelekan ML, Makanjuola AB and Ndom, RJ (2001) Traditional mental health practitioners in Kwara State, Nigeria. East African Medical Journal 78, 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja KKD, Dhillon M, Juneja A and Sharma B (2017) Breaking barriers: An education and contact intervention to reduce mental illness stigma among Indian college students. Psychosocial Intervention 26, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Altindag A, Yanik M, Ucok A, Alptekin K and Ozkan M (2006) Effects of an antistigma program on medical students' attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 60, 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J, Liu Z, Evans-Lacko S, Sadikova E, Sampson N, Chatterji S, Abdulmalik J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade LH, Bruffaerts R, Cardoso G, Cia A, Florescu S, De Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, He Y, De Jonge P, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Navarro-Mateu F, Pennell BE, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Ten Have M, Zarkov Z, Kessler RC and Thornicroft G (2018) Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depression and Anxiety 35, 195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaresha AC, Kalmady SV, Joseph B, Agarwal SM, Narayanaswamy JC, Venkatasubramanian G, Muralidhar D and Subbakrishna DK (2018) Short term effects of brief need based psychoeducation on knowledge, self-stigma, and burden among siblings of persons with schizophrenia: A prospective controlled trial. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 32, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amna Z and Lin HC (2016). The effects of psycho-education methods on college students' attitudes toward PTSD. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun 4, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong G, Kermode M, Raja S, Suja S, Chandra P and Jorm AF (2011) A mental health training program for community health workers in India: impact on knowledge and attitudes. International journal of mental health systems 5, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayano G, Assefa D, Haile K, Chaka A, Haile K, Solomon M, Yohannis K, Awoke A and Jemal K (2017) Mental health training for primary health care workers and implication for success of integration of mental health into primary care: evaluation of effect on knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP). International journal of mental health systems 11, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayonrinde AE and Olayiwola A (1976) Mental health education and attitudes to psychiatric disorder at a rural health centre in Nigeria. Psychopathologie Africaine 12, 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bella-Awusah T, Adedokun B, Dogra N and Omigbodun O (2014) The impact of a mental health teaching programme on rural and urban secondary school students' perceptions of mental illness in southwest Nigeria. Journal of child and adolescent mental health 26, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlim MT, Perizzolo J, Lejderman F, Fleck MP and Joiner TE (2007) Does a brief training on suicide prevention among general hospital personnel impact their baseline attitudes towards suicidal behavior? Journal of affective disorders 100, 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosoni NO, Busatto Filho G and de Barros DM (2017) The impact of a TV report in schizophrenia stigma reduction: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 63, 275–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botega NJ, Silva SV, Reginato DG, Rapeli CB, Cais CF, Mauro ML, Stefanello S and Cecconi JP (2007) Maintained attitudinal changes in nursing personnel after a brief training on suicide prevention. Suicide & life-threatening behavior 37, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Booth A and Cooper K (2011) A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology 11, 29–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J and Rick J (2013) “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnayya HP, Chandrashekar CR, Moily S, Raghuram A, Subramanya KR, Shanmugham V and Udaykumar GS (1990) Training Primary Care Health Workers in Mental Health Evaluation of Attitudes towards Mental Illness before and after Training. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 36, 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Lassman F, Barley E, Evans-Lacko S, Williams P, Yamaguchi S, Slade M, Rusch N and Thornicroft G (2013) Mass media interventions for reducing mental health-related stigma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7, CD009453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, Bordin IA, Costello EJ, Durkin M, Fairburn C, Glass RI, Hall W, Huang Y, Hyman SE, Jamison K, Kaaya S, Kapur S, Kleinman A, Ogunniyi A, Otero-Ojeda A, Poo M-M, Ravindranath V, Sahakian BJ, Saxena S, Singer PA, Stein DJ, Anderson W, Dhansay MA, Ewart W, Phillips A, Shurin S and Walport M (2011) Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature 475, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PM (2004) How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist 59, 614–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P and Bink A (2005) On the Stigma of Mental Illness. US: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PM and Scott B (2012) Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services 10, 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Penn DL, Uphoff-Wasowski K, Campion J, Mathisen J, Gagnon C, Bergman M, Goldstein H and Kubiak MA (2001) Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27, 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Vega E, Larson J, Michaels PJ, Mcclintock G, Krzyzanowski R, Gause M and Buchholz B (2013) The California schedule of key ingredients for contact-based antistigma programs. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 36, 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Michaels PJ, Vega E, Gause M, Larson J, Krzyzanowski R and Botcheva L (2014) Key ingredients to contact-based stigma change: a cross-validation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 37, 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çuhadar D and Çam MO (2014) Effectiveness of psychoeducation in reducing internalized stigmatization in patients with bipolar disorder. Archives of psychiatric nursing 28, 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Cais CF, da Silveira IU, Stefanello S and Botega NJ (2011) Suicide Prevention Training for Professionals in the Public Health Network in a Large Brazilian City. Archives of Suicide Research 15, 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiroren MS, Saka MC, Senol Y, Senturk V, Baysal O and Oztuna D (2016) The impact of reflective practices on medical students' attitudes towards mental illness. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi 17, 466–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dharitri R, Rao SN and Kalyanasundaram S (2015) Stigma of mental illness: An interventional study to reduce its impact in the community. Indian journal of psychiatry 57, 165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Martinez T, Rascon-Gasca ML, Alcántara-Chabelas H, Garcia-Silberman S, Casanova-Rodas L and Lopez-Jimenez JL (2017) Effects of family-to-family psychoeducation among relatives of patients with severe mental disorders in Mexico City. Psychiatric services 68, 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman ZÇ, Günüşen NP, İnan FŞ, Ince SÇ and Sari A (2017) Effects of two different psychiatric nursing courses on nursing students' attitudes towards mental illness, perceptions of psychiatric nursing, and career choices. Journal of Professional Nursing 33, 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Binagwaho A, Martell HC and Mulley AG (2014) Mental healthcare in low and middle income countries. The BMJ 349, g7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Nahas GM, Ramy H, Hussein H, El-Gabry D, Sultan MA, Bassim RE and El-Ghamry R (2018) Effectiveness of a culturally adapted behavioural family psychoeducational programme on the attitude of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: an Egyptian study. Middle East current psychiatry 25, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A, Tan KA, Knaak S, Chew BH and Ghazali SS (2016) Effects of brief psychoeducational program on stigma in Malaysian pre-clinical medical students: a randomized controlled trial. Academic Psychiatry 40, 905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein J, Lapshin O and Wasserman E (2008) Randomized study of different anti-stigma media. Patient Education and Counseling 71, 204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronholm PC, Henderson C, Deb T and Thornicroft G (2017) Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: the state of the art. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52, 249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal M, Kohli C, Kishore J and Jiloha RC (2013) Effect of an Educational Booklet on Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Major Depressive Disorder in Medical Students in Delhi. International Journal of Medical Students 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Heijnders M and Van Der Meij S (2006) The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine 11, 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim E, Kohrt BA, Koschorke M, Milenova M and Thronicroft G (2018) Reducing mental health-related stigma in primary health care settings in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 29, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim E, Henderson C, Kohrt BA, Koschorke M, Milenova M and Thornicroft G (2019) Reducing mental health-related stigma among medical and nursing students in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 29, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C and Thornicroft G (2009) Stigma and discrimination in mental illness: time to change. The Lancet 373, 1928–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann-Broussard C, Armstrong G, Boschen MJ and Somasundaram KV (2017) A mental health training program for community health workers in India: impact on recognition of mental disorders, stigmatizing attitudes and confidence. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 10, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hong QN, Fabregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O'Cathain A, Rousseau MC, Vedel I and Pluye P (2018) Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. Available at http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (Accessed May 2019).

- Iheanacho T, Marienfeld C, Stefanovics E and Rosenheck RA (2014) Attitudes toward mental illness and changes associated with a brief educational intervention for medical and nursing students in Nigeria. Academic Psychiatry 38, 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Howard L and Thornicroft G (2008) ‘Diagnostic overshadowing’: worse physical health care for people with mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 118, 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CG, Jarrett BA, Kwon C-S, Song L, Jetté N, Sapag J C, Bass J, Murray L, Rao D and Baral S (2019) Implementation science and stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Medicine 17, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keynejad R, Garratt E, Adem G, Finlayson A, Whitwell S and Sheriff RS (2016) Improved attitudes to psychiatry: a global mental health peer-to-peer e-learning partnership. Academic Psychiatry 40, 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaak S, Modgill G and Patten SB (2014) Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: a data synthesis of evaluative studies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 59, 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaak S, Mantler E and Szeto A (2017) Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthcare Management Forum 30, 111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutcher S, Gilberds H, Morgan C, Greene R, Hamwaka K and Perkins K (2015) Improving Malawian teachers' mental health knowledge and attitudes: an integrated school mental health literacy approach. Global Mental Health, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutcher S, Wei Y, Gilberds H, Ubuguyu O, Njau T, Brown A, Sabuni N, Magimba A and Perkins K (2016) A school mental health literacy curriculum resource training approach: effects on Tanzanian teachers’ mental health knowledge, stigma and help-seeking efficacy. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 10, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Li J, Huang Y and Thornicroft G (2014) Mental health training program for community mental health staff in Guangzhou, China: effects on knowledge of mental illness and stigma. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 8, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Huang YG, Ran MS, Fan Y, Chen W, Evans-Lacko S and Thornicroft G (2018) Community-based comprehensive intervention for people with schizophrenia in Guangzhou, China: effects on clinical symptoms, social functioning, internalized stigma and discrimination. Asian journal of psychiatry 34, 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Fan Y, Zhong HQ, Duan XL, Chen W, Evans-Lacko S and Thornicroft G (2019) Effectiveness of an anti-stigma training on improving attitudes and decreasing discrimination towards people with mental disorders among care assistant workers in Guangzhou, China. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 13, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makanjuola V, Doku V, Jenkins R and Gureje O (2012) Impact of a one-week intensive ‘training of trainers’ workshop for community health workers in south-west Nigeria. Mental health in family medicine 9, 33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik PK, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, Tewari A, Chilappagari S, Koschorke M and Thornicroft G (2017) Evaluation of an anti-stigma campaign related to common mental disorders in rural India: a mixed methods approach. Psychological medicine 47, 565–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik PK, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, Tripathi AP, Koschorke M and Thornicroft G (2019) Longitudinal assessment of an anti-stigma campaign related to common mental disorders in rural India. The British Journal of Psychiatry 214, 90–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E, Stona AC, Bezborodovs N, Evans-Lacko S, Palacios J, Docherty M, Barley E, Rose D, Koschorke M, Shidhaye R, Henderson C and Thornicroft G (2018) Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry 207, 377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor C (2018) School-based interventions targeting stigma of mental illness: systematic review. The Psychiatric Bulletin 38, 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D, Sullivan G, Chekuri L, Allee E and Corrigan PW (2012) Empirical studies of self-stigma reduction strategies: a critical review of the literature. Psychiatric Services 63, 974–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A J, Reavley NJ, Ross A, Too LS and Jorm AF (2018) Interventions to reduce stigma towards people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research 103, 120–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutiso VN, Pike K, Musyimi CW, Rebello TJ, Tele A, Gitonga I, Thornicroft G and Ndetei DM (2019) Feasibility of WHO mhGAP-intervention guide in reducing experienced discrimination in people with mental disorders: a pilot study in a rural Kenyan setting. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences 28, 156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng YP, Rashid A and O'Brien F (2017) Determining the effectiveness of a video-based contact intervention in improving attitudes of Penang primary care nurses towards people with mental illness. PloS one 12, e0187861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc TN, Weiss B and Trung LT (2016) Effects of the family schizophrenia psychoeducation program for individuals with recent onset schizophrenia in Viet Nam. Asian journal of psychiatry 22, 162–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oduguwa AO, Adedokun B and Omigbodun OO (2017) Effect of a mental health training programme on Nigerian school pupils’ perceptions of mental illness. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 11, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, Chisholm D, Collins PY, Cooper J L, Eaton J, Herrman H, Herzallah M M, Huang Y, Jordans MJD, Kleinman A, Medina-Mora ME, Morgan E, Niaz U, Omigbodun O, Prince M, Rahman A, Saraceno B, Sarkar BK, De Silva M, Singh I, Stein DJ, Sunkel C and Unützer J (2018) The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet 392, 1553–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B, Medina T, Martin J and Long JS (2013) The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 103, 853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejović-Milovančević M, Lečić-Toševski D, Tenjović L, Popović-Deušić S and Draganić-Gajić S (2009) Changing attitudes of high school students towards peers with mental health problems. Psychiatria Danubina 21, 213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira CA, Wen CL, Miguel EC and Polanczyk GV (2015) A randomised controlled trial of a web-based educational program in child mental health for schoolteachers. European child & adolescent psychiatry 24, 931–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinfold V, Thornicroft G, Huxley P and Farmer P (2005) Active ingredients in anti-stigma programmes in mental health. International Review of Psychiatry 17, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S and Kingdon D (2014) Case for cultural adaptation of psychological interventions for mental healthcare in low and middle income countries. The BMJ 349, g7636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahayuni IG, Wichaikull S and Charoensuk S (2013, November) The Effect of a Family Psycho-Education Program on Family Caregivers’ Attitude to Care for Patients with Schizophrenia. In ASEAN/Asian Academic Society International Conference Proceeding Series.

- Rahman A, Mubbashar MH, Gater R and Goldberg D (1998) Randomised trial of impact of school mental-health programme in rural Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The Lancet 352, 1022–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran MS, Xiang MZ, Chan CL, Leff J, Simpson P, Huang MS, Shan YH and Li SG (2003) Effectiveness of psychoeducational intervention for rural Chinese families experiencing schizophrenia. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 38, 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran AV, Herrera A, da Silva TL, Henderson J, Castrillo ME and Kutcher S (2018) Evaluating the benefits of a youth mental health curriculum for students in Nicaragua: a parallel-group, controlled pilot investigation. Global Mental Health 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Y, Glozier N, Luscombe GM, Davenport TA, Huang Y and Hickie IB (2011) Improving knowledge and attitudes towards depression: a controlled trial among Chinese medical students. BMC psychiatry 11, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraceno B, Van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, Sridhar D and Underhill C (2007) Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 370, 1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G (1998) Stigma and disease: changing paradigms. The Lancet 352, 1054–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, Van Brakel WC, Simbayi L, Barré I and Dovidio JF (2019) The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine 17, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart H (2016) Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Global Mental Health 3, e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadik S, Abdulrahman S, Bradley M and Jenkins R (2011) Integrating mental health into primary health care in Iraq. Mental Health in Family Medicine 8, 39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhori Z, Eide AH, Ayazi T, Mdala I and Lien L (2019) Change in mental health stigma after a brief intervention among internally displaced persons in Central Sudan. Community Mental Health Journal 55, 534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah ND, Mehta RY and Dave KR (2015) The Impact Of Mental Health Education On The Knowledge And Attitude Of The Peripheral Health Workers Of Dang. National Journal of Integrated Research in Medicine 6. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsaei F, Nazari F and Sadeghian E (2018) The effect of training interventions of stigma associated with mental illness on family caregivers: a quasi-experimental study. Annals of general psychiatry 17, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibeko G, Milligan PD, Roelofse M, Molefe L, Jonker D, Ipser J, Lund C and Stein DJ (2018) Piloting a mental health training programme for community health workers in South Africa: an exploration of changes in knowledge, confidence and attitudes. BMC psychiatry 18, 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong P, Bu P, Yang Y, Dong L, Sun T and Shi Y (2019) Group cognitive behavioural therapy can reduce stigma and improve treatment compliance in major depressive disorder patients. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 14, 172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (2019) World Bank Country and Lending Groups- Country Classification. Available at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (Accessed 4 May 2019).

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Kassam A and Lewis-Holmes E (2008) Reducing stigma and discrimination: candidate interventions. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2, 3–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N and Leese M (2009) Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. The Lancet 373, 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, Koschorke M, Shidhaye R, O'Reilly C and Henderson C (2016) Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. The Lancet 387, 1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, Gruber M, Sampson N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Andrade L, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Bunting B, De Almeida J M, Florescu S, De Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, He Y, Hinkov H, Karam E, Kawakami N, Lee S, Navarro-Mateu F, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, De Galvis YT and Kessler R C (2017) Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. British Journal of Psychiatry 210, 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ucok A, Soyguer H, Atakli C, Kuşcu K, Sartorius N, Duman ZC, Polat A and Erkoç Ş (2006) The impact of antistigma education on the attitudes of general practitioners regarding schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 60, 439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghee S, Salarhaji A and Vaghei N (2015) Comparing the effect of in our own voice-family with psychoeducation on stigma in families of schizophrenia patients. Nursing Practice Today 2, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MG, Jadhav S, Raguram R, Vounatsou P and Littlewood R (2001) Psychiatric stigma across cultures: local validation in Bangalore and London. Anthropology & Medicine 8, 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Trust (2019) Wellcome boosts mental health research with extra £200 million. Wellcome Trust. Available at https://wellcome.ac.uk/press-release/wellcome-boosts-mental-health-research-extra-£200-million (Accessed 8 May 2019).

- Worakul P, Thavichachart N and Lueboonthavatchai P (2007) Effects of psycho-educational program on knowledge and attitude upon schizophrenia of schizophrenic patients’ caregivers. J Med Assoc Thai 90, 1199–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Rieger E and Shou Y (2018) Reducing the stigma associated with anorexia nervosa: An evaluation of a social consensus intervention among Australian and Chinese young women. International Journal of Eating Disorders 51, 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]