Abstract

The plant Chloranthus japonicus Sieb is known for its anticancer properties and mainly distributed in China, Japan, and Korea. In this study, we firstly investigated the diversity and antimicrobial activity of the culturable endophytic fungi from C. japonicus. A total of 332 fungal colonies were successfully isolated from 555 tissue segments of the medicinal plant C. japonicus collected from Qinling Mountains, China. One hundred and thirty representative morphotype strains were identified according to ITS rDNA sequence analyses and were grouped into three phyla (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mucoromycota), five classes (Dothideomycetes, Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Agaricomycetes, Mucoromycetes), and at least 30 genera. Colletotrichum (RA, 60.54%) was the most abundant genus, followed by Aspergillus (RA, 11.75%) and Diaporthe (RA, 9.34%). The Species Richness Index (S, 56) and the Shannon-Wiener Index (H′, 2.7076) indicated that C. japonicus harbored abundant fungal resources. Thirteen out of 130 endophytic fungal ethyl acetate extracts exhibited inhibitory activities against at least one pathogenic bacterium or fungus. Among of these, F8158, which was identified as Trichoderma cf. harzianum, exhibited good antagonistic capacities (the percent inhibition of mycelial growth ranged from 47.72~88.18) for different pathogens and has a potential application in biological control. In addition, it is noteworthy that the strain F8157 (Thanatephorus cucumeris, an opportunistic pathogen) showed antibacterial and antifungal activity, which is reported firstly in this study, and should be investigated further. Taken together, these results indicated that the endophytic fungi from C. japonicus may be of potential interest in screening bio-control agents and discovering of new bioactive compounds.

Keywords: endophytic fungi, diversity, antimicrobial activity, Chloranthus japonicus, Qinling Mountains

1. Introduction

The Qinling Mountains (32°30′−34°45′ N, 104°30′−112°45′ E), which are mainly located in the south of Shaanxi province in central China, are the most important natural climatic boundary between the subtropical and warm temperate zones of China, and support an astonishingly high biodiversity [1,2,3,4]. In particular, the Qinling Mountains are extremely rich in medicinal plants, including Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) Ying, Rohdea chinensis (Baker) N.Tanaka, Bergenia scopulosa TP Wang, Aconitum taipeicum Hand-Mazz, etc. Chloranthus japonicus Sieb. (Chloranthaceae, “yin-xian-cao” in Chinese), which is a perennial herb mainly distributed in eastern Asia such as the mainland of China, Korea, and Japan [5], is also a typical medicine resource in Qingling Mountains. Its whole plants have long been a Chinese folk medicine to treat traumatic injuries, rheumatic arthralgia, fractures, pulmonary tuberculosis, and neurasthenia in China [6]. It was reported that the sesquiterpenoids were its mainly active compounds in this plant [5,6,7].

Endophytic fungi, which inhabit the interiors various plant tissues without causing disease or injury to the host, have a very complex relationship with their host plants [8]. The endophytic fungi not only produce hormones that promote plant growth and help the host resist abiotic stress but also produce bioactive secondary metabolites, including those originated from the host plants [9,10]. For instance, all the endophytic fungi taxa isolated from the Glycyrrhiza glabra have been reported to produce the plant growth promoting hormone indole acetic acid (IAA) [11]. Taxol, a widely employed anticancer drug, was originally isolated from the bark of Taxus brevifolia, and have also been produced by a series of endophytic fungi from different plants [12,13]. Tan et al. isolated two endophytic fungi producing the podophyllotoxin, a main active compound from the host plant Dysosma versipellis [14].

Due to the increase in antibiotic resistance among pathogens, discovering novel antimicrobials is urgent [15]. Endophytic fungi represent abundant species resources and secondary metabolites diversity [16]. Nevertheless, the resources of endophytic fungi remain underexplored. In this study, our main purpose is to investigate the diversity of these endophytic fungi from C. japonicus and to obtain endophytic fungi resources with antibacterial activities, so as to provide a basis for further screening for biocontrol agents or mining natural products with new structures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the diversity and antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi isolated from C. japonicus.

2. Results

2.1. Isolation, Sequencing, Identification, and Diversity Analyses of the Endophytic Fungi from C. japonicus

In this study, a total of 332 fungal colonies were successfully isolated from 555 tissue segments of C. japonicus with a potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium. The 332 isolates initially were assigned to 130 representative morphotypes according to their culture characteristics on PDA. ITS rDNA sequences subsequently were generated for a representative of each morphotype (Supplementary Information Files (1)). Based on the sequence similarity threshold (SSA, 97%~100%) 124 isolates were categorized at the genus level while the other six isolates remained unidentified. The phylogenetic trees were constructed by using the maximum likelihood method (Supplementary Information Files (2)). Some species were still not well categorized. For example, although the isolates F8210, F8235, F8210, F8176, F8170, F8135, F8110, F8115, and Colletotrichum sp. SL10 (KP689235) were in the same branch, the support rating was only 60%. These isolates may be different taxa though we classified them into one taxon (Colletotrichum sp. SL10) in this study. In total, these isolates were grouped into at least 56 taxa (Table 1) based on the results of sequence BLAST and phylogenetic trees analysis. The isolate F4146 was only assigned to the phylum Ascomycota, and the isolates F8184, F8209, F8233, F8241, and F8245 were only categorized as the class Sordariomycetes. Ultimately, the Species Richness Index (S) and Shannon-Wiener Index (H′), which are two important parameters for diversity analysis, were at least 56 and 2.7076 for C. japonicus, respectively. As presented in Table 2, these isolates have been further grouped into three phyla (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mucoromycota), five classes (Dothideomycetes, Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Agaricomycetes, Mucoromycetes), 12 orders, 21 families, and at least 30 fungal genera.

Table 1.

Identification of endophytic fungi from C. japonicus by the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) in the GenBank.

| No. | Closest Species | Isolates Numbers | Identity (%) | N | IF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arthrinium hydei CBS 114.990 (KF144890) | F8164 | 95.42 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 2 | Aspergillus flavipes AfH14F02 (MK952227) | F8142, F8204, F8225 | 98.73 | 3 | 0.90 |

| 3 | Aspergillus terreus MD32_7 (JQ697508) | F8121, F8159, F8172, F8191 | 99.46 | 20 | 6.02 |

| 4 | Aspergillus pseudoglaucus ALE-85 (MF380824) | F8123 | 99.24 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 5 | Aspergillus niger strain H1 (KJ778683) | F8143, F8150, F8186 | 99.30 | 6 | 1.81 |

| 6 | Aspergillus oryzae isolate 118 (MH345958) | F8160, F8161, F8224 | 99.82 | 4 | 1.20 |

| 7 | Aspergillus sp. isolate SW511 (MH509427) | F8190, F8243, F8238 | 99.47 | 3 | 0.90 |

| 8 | Aspergillus tubingensis BSZ-6(2) (KJ190960) | F8208 | 99.81 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 9 | Aspergillus flavus strain S2599 (MG575474) | F8111 | 99.64 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 10 | Clonostachys rosea QLF2 (FJ025204) | F8195 | 99.26 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 11 | Thanatephorus cucumeris AG-7 (AY154305) | F8154, F8157 | 98.71 | 6 | 1.80 |

| 12 | Podospora nannopodalis CBS 113.680 (MH862937) | F8109 | 99.02 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 13 | Podospora setosa CBS 613.84 (MH861787) | F8117, F8156 | 99.21 | 3 | 0.90 |

| 14 | Cladosporium tenuissimum 7P6 (KY400093) | F8144 | 99.81 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 15 | Diaporthe eres HUTA286 (KU377286) | F8107, F8205 | 99.26 | 7 | 2.11 |

| 16 | Diaporthe longicolla ALE-196 (MF380785) | F8124 | 97.95 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 17 | Diaporthe nobilis ZZDN1 (MG736062) | F8128, F8196, F8207 | 99.28 | 5 | 1.51 |

| 18 | Diaporthe gulyae SJC3-2 (KX077244) | F8116, F8179, F8192 | 99.63 | 11 | 3.31 |

| 19 | Diaporthe longicolla ALE-196 (MF380785) | F8124 | 97.95 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 20 | Diaporthe vaccinii Lan1 (KC488258) | F8137, F8180, F8206 | 99.11 | 3 | 0.90 |

| 21 | Diaporthe citrichinensis ZJUD034B (KJ210539) | F8193, F8194, F8237 | 97.32 | 3 | 0.90 |

| 22 | Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum D49 (MF401570) | F8151 | 99.06 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 23 | Didymella bellidis YS24 (MN443603) | F8165 | 100.00 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 24 | Dothiorella gregaria hz-S8 (FJ517548) | F8178 | 100.00 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 25 | Paraconiothyrium brasiliense 1-53 (JF502455) | F8181 | 99.62 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 26 | Colletotrichum boninense JL7 (KM513575) | F8108 | 99.82 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 27 | Colletotrichum sp. SL10 (KP689235) | F8110, F8135, F8129, F8170, F8176, F8201, F8210, F8213, F8235, F8115, F8120 | 99.10 | 31 | 9.34 |

| 28 | Colletotrichum acutatum JS4 (KM513609) | F8114, F8118, F8129, F8134, F8140, F8152, F8162, F8167, F8188, F8190, F8198, F8231 | 100.00 | 55 | 16.57 |

| 29 | Colletotrichum truncatum SL3-CJL17 (KP900265) | F8119, F8141, F8171, F8174, F8175, F8177, F8187, F8202, F8211, F8212, F8221, F8244 | 99.81 | 109 | 32.83 |

| 30 | Colletotrichum fructicola JXNC-7 (MK041519) | F8136, F8155 | 99.81 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 31 | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides HBxn-3 (HQ645077) | F8203 | 99.26 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 32 | Colletotrichum higginsianum XN4-5 (JF830783) | F8239, F8240 | 99.63 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 33 | Trichoderma cf. harzianum PDAN04-1 (MF108878) | F8158 | 99.66 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 34 | Trichoderma sp. SDAS203699 (MK870422) | F8166, F8182, F8197, F8220, F8223, F8226 | 98.99 | 6 | 1.81 |

| 35 | Hypoxylon fragiforme RY-3 (MK429859) | F8218 | 98.97 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 36 | Ceriporia alachuana CEAL72 (MF358878) | F8112 | 99.36 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 37 | Mucor fragilis BC3 (MK910073) | F8199 | 99.50 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 38 | Muyocopron lithocarpi MFLUCC:17-1500 (MT137781) | F8248 | 99.82 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 39 | Septoria arundinacea LHH10-8 (JX077003) | F8125, F8185, F8219, F8246 | 100.00 | 4 | 1.20 |

| 40 | Fusarium sambucinum CBS 146.95 (KM231813) | F8126, F8132 | 98.79 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 41 | Fusarium verticillioides G4 (MK264336) | F8200 | 100.00 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 42 | Calonectria eucalypti (KM357290) | F8168 | 99.03 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 43 | Ilyonectria robusta (MN121555) | F8145 | 99.40 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 44 | Dactylonectria alcacerensis JZB3310013 (MN944923) | F8217 | 99.42 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 45 | Nectria pseudotrichia (MN121548) | F8131 | 98.58 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 46 | Neonectria sp. nc_gw_9967b (KF428559) | F8153 | 98.82 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 47 | Plectosphaerella sp. GZUIFR-QL9.9.1 (MK880441) | F8247 | 98.86 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 48 | Alternaria alternata Acf-4 (MK795217) | F8214, F8215 | 99.63 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 49 | Talaromyces funiculosus S01324 (MG744693) | F8138, F8149 | 99.46 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 50 | Talaromyces pinophilus KR9 (MF153381) | F8230 | 99.83 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 51 | Talaromyces purpureogenus NFML_CH66 (KM458841) | F8222 | 98.73 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 52 | Nemania sp. 1 XS-2016 VD026 (KT588467) | F8183, F8229, F8113 | 99.26 | 3 | 0.90 |

| 53 | Biscogniauxia sp. strain LPS-70 (MF379340) | F8130, F8147 | 99.63 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 54 | Leptospora rubella strain ZLVG 319 (HE774478) | F8127 | 96.38 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 55 | Ascomycota sp. isolate FL15 (MK370697 | F8146 | 90.00 | 1 | 0.30 |

| 56 | Sordariomycetes sp. 329 isolate FL0587 (JQ760299) | F8184, F8209, F8233, F8241, F8245 | 86.76 | 5 | 1.51 |

| Total | 130 | 130 | 332 | 100 | |

| Species Richness (S) | 56 | ||||

| Shannon-Wiener index (H′) | 2.7076 | ||||

Table 2.

Taxa of all endophytic fungi isolates from C. japonicus.

| No. | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Number (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ascomycota | Sordariomycetes | Xylariales | Apiosporaceae | Arthrinium | 1 |

| 2 | Hypocreales | Xylariaceae | Nemania | 3 | ||

| 3 | Biscogniauxia | 4 | ||||

| 4 | Hypoxylaceae | Hypoxylon | 1 | |||

| 5 | Bionectriaceae | Clonostachys | 1 | |||

| 6 | Nectriaceae | Fusarium | 3 | |||

| 7 | Calonectria | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Ilyonectria | 1 | ||||

| 9 | Dactylonectria | 1 | ||||

| 10 | Nectria | 1 | ||||

| 11 | Neonectria | 1 | ||||

| 12 | Hypocreaceae | Trichoderma | 8 | |||

| 13 | Sordariales | Chaetomiaceae | Podospora | 4 | ||

| 14 | Diaporthales | Diaporthaceae | Diaporthe | 31 | ||

| 15 | Glomerellales | Glomerellaceae | Colletotrichum | 201 | ||

| 16 | Plectosphaerellaceae | Plectosphaerella | 1 | |||

| 17 | Eurotiomycetes | Eurotiales | Aspergillaceae | Aspergillus | 39 | |

| 18 | Trichocomaceae | Talaromyces | 4 | |||

| 19 | Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | Cladosporiaceae | Cladosporium | 1 | |

| 20 | Leptospora | 1 | ||||

| 21 | Pleosporales | Mycosphaerellaceae | Septoria | 4 | ||

| 22 | Didymellaceae | Stagonosporopsis | 1 | |||

| 23 | Didymella | 1 | ||||

| 24 | Dothiorella | 1 | ||||

| 25 | Pleosporaceae | Alternaria | 2 | |||

| 26 | Didymosphaeriaceae | Paraconiothyrium | 1 | |||

| 27 | Muyocopronales | Muyocopronaceae | Muyocopron | 1 | ||

| 28 | Basidiomycota | Agaricomycetes | Cantharellales | Ceratobasidiaceae | Thanatephorus | 6 |

| 29 | Polyporales | Irpicaceae | Ceriporia | 1 | ||

| 30 | Mucoromycota | Mucoromycetes | Mucorales | Mucoraceae | Mucor | 1 |

| Total | 3 | 5 | 12 | 21 | 30 | 325 |

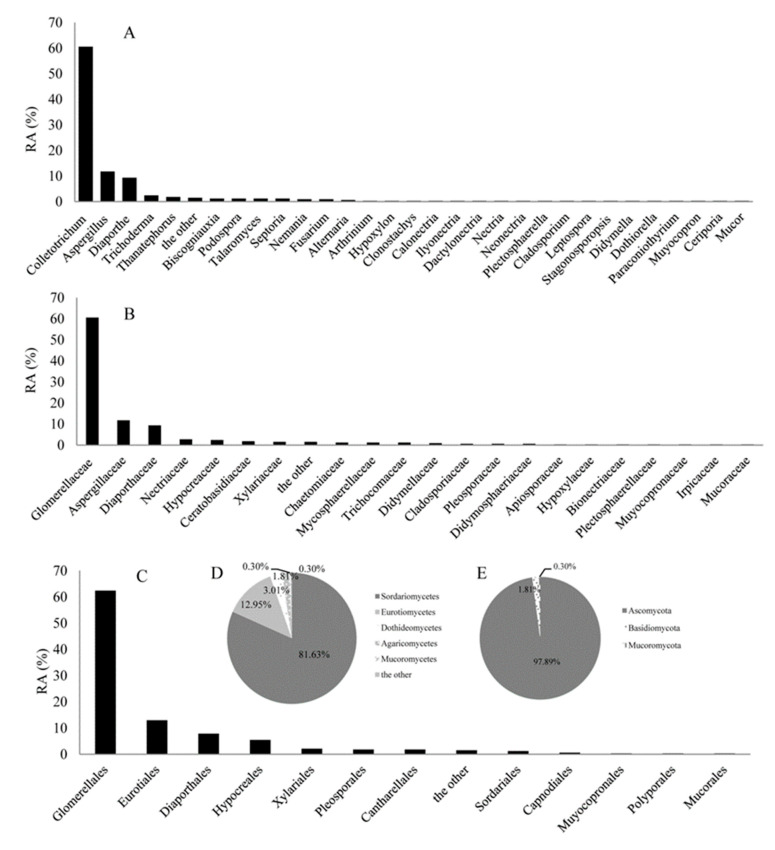

2.2. The Relative Abundance (RA) Analyses of Endophytic fungi from C. japonicus

As shown in Table 1, Colletotrichum truncatum, Colletotrichum acutatum, and Colletotrichum sp. were dominant species and their IF were 32.83%, 16.57%, and 9.34%, respectively. The RA of these isolates at genus, family, order, class, and phylum levels were shown in Figure 1A–E, respectively. At the genus level, Colletotrichum (RA, 60.54%) was most abundant, followed by the Aspergillus (RA, 11.75%) and Diaporthe (RA, 9.34%). Aspergillus included at least eight species (Aspergillus flavipes, Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus pseudoglaucus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, Aspergillus sp., Aspergillus tubingensis, Aspergillus flavus); Diaporthe included at least seven species (Diaporthe eres, Diaporthe longicolla, Diaporthe nobilis, Diaporthe gulyae, Diaporthe longicolla, Diaporthe vaccinii, Diaporthe citrichinensis); Colletotrichum included at least seven species (Colletotrichum boninense, Colletotrichum sp., Colletotrichum acutatum, Colletotrichum truncatum, Colletotrichum fructicola, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Colletotrichum higginsianum). At the family level, Glomerellaceae (RA, 60.54%), Aspergillaceae (RA, 11.75%), and Diaporthaceae (RA, 9.34%) were the three most abundant groups in this study. At the phylum level, the majority of fungi isolated from C. japonicus were identified as Ascomycota (RA, 97.89%), which represented three classes (Sordariomycetes (RA, 81.63%), Eurotiomycetes (RA, 12.95%), and Dothideomycetes (RA, 3.01%)). In addition, one class (Agaricomycetes, RA, 1.81%) belonged to Basidiomycota (RA, 1.81%), and one class (Mucoromycetes, RA, 0.31%) belonged to Mucoromycota (RA, 0.31%).

Figure 1.

The relative abundance (RA, %) of endophytic fungi at the level of genus (A). Family (B), order (C), class (D), and phylum (E).

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity Screening of the Ethyl Acetate Extracts from Endophytic Fungal Culture Filtrates

As shown in Table 3, 13 out of 130 endophytic fungal ethyl acetate extracts showed inhibitory activity against at least one pathogenic bacterium or fungus (Supplementary Information Files (3)). The other 117 extracts did not show inhibitory activities. These 13 strains belonged to genera of Diaporthe, Trichoderma, Aspergillus, Leptospora, Thanatephorus, Colletotrichum, Septoria, respectively (Table 2). Among these strains, F8158 (Trichoderma cf. harzianum (GenBank Accession number: MN429210), commonly used as biocontrol agents in the agricultural production process), also exhibited a broad spectrum antimicrobial activity and has potential application in the biological control. Further experiments showed that the strain F8158 exhibited a plant promoting effect by producing siderophore (data not shown). In addition, it is noteworthy that the strain F8157 (Thanatephorus cucumeris, an opportunistic pathogen), showed antibacterial and antifungal activity, which is reported firstly in this study, and has the potential research value.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activities of culturable endophytic fungi from C. japonicus.

| Isolates No. | Taxa (Accession Number) | Inhibition Zone in Diameter on Petri Plate (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. cereus | E. coli | B. subtilis | S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | R. solanacearum | C. albicans | ||

| F8107 | Diaporthe eres (MN429162) | 12.02 ± 0.11 | 10.44 ± 0.04 | 10.93 ± 0.05 | 13.27 ± 0.16 | - | 10.10 ± 0.07 | - |

| F8121 | Aspergillus terreus (MN429176) | 17.14 ± 0.13 | 10.08 ± 0.14 | 20.65 ± 0.40 | 16.12 ± 0.08 | - | - | 9.09 ± 0.04 |

| F8127 | Leptospora rubella (MN429181) | 11.34 ± 0.12 | - | 14.26 ± 0.09 | 12.58 ± 0.15 | - | 8.96 ± 0.08 | - |

| F8157 | Thanatephorus cucumeris (MN429209) | - | - | 12.14 ± 0.14 | - | 10.32 ± 0.20 | 8.27 ± 0.18 | 8.94 ± 0.05 |

| F8158 | Trichoderma cf. harzianum (MN429210) | 19.15 ± 0.13 | 10.81 ± 0.28 | 19.12 ± 0.15 | 19.36 ± 0.14 | 10.21 ± 0.12 | 12.02 ± 0.03 | 10.81 ± 0.16 |

| F8159 | Aspergillus terreus (MN429211) | 15.33 ± 0.13 | 10.76 ± 0.25 | 21.15 ± 0.27 | 17.37 ± 0.11 | - | 16.48 ± 0.13 | 9.75 ± 0.17 |

| F8160 | Aspergillus oryzae (MN429212) | 11.21 ± 0.14 | - | 12.13 ± 0.10 | 12.12 ± 0.08 | - | 11.02 ± 0.03 | - |

| F8172 | Aspergillus terreus (MN429223) | 17.31 ± 0.19 | 10.84 ± 0.03 | 20.82 ± 0.17 | 16.39 ± 0.09 | - | 12.46 ± 0.10 | 10.21 ± 0.12 |

| F8189 | Colletotrichum acutatum (MN429239) | 12.30 ± 0.17 | - | 16.04 ± 0.13 | 13.17 ± 0.18 | - | 11.05 ± 0.09 | 9.14 ± 0.07 |

| F8191 | Aspergillus terreus (MN429241) | 20.56 ± 0.30 | - | 20.62 ± 0.41 | 15.38 ± 0.08 | - | 11.28 ± 0.15 | 9.34 ± 0.12 |

| F8204 | Aspergillus flavipes (MN429254) | 12.29 ± 0.18 | - | 10.27 ± 0.18 | - | - | 8.33 ± 0.13 | - |

| F8219 | Septoria arundinacea (MN429268) | 10.21 ± 0.13 | - | 10.98 ± 0.08 | 11.29 ± 0.15 | - | 10.85 ± 0.12 | |

| F8225 | Aspergillus flavipes (MN429274) | 11.13 ± 0.12 | - | 15.31 ± 0.24 | 16.23 ± 0.12 | - | 13.94 ± 0.08 | - |

| Positive control-1 | Ampicillin sodium | 20.48 ± 0.53 | 15.46 ± 0.22 | 23.34 ± 0.38 | 21.49 ± 0.27 | 17.34 ± 0.26 | 19.55 ± 0.21 | - |

| Positive control-2 | Actidione | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21.15 ± 0.84 |

| Negative control | Methanol | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

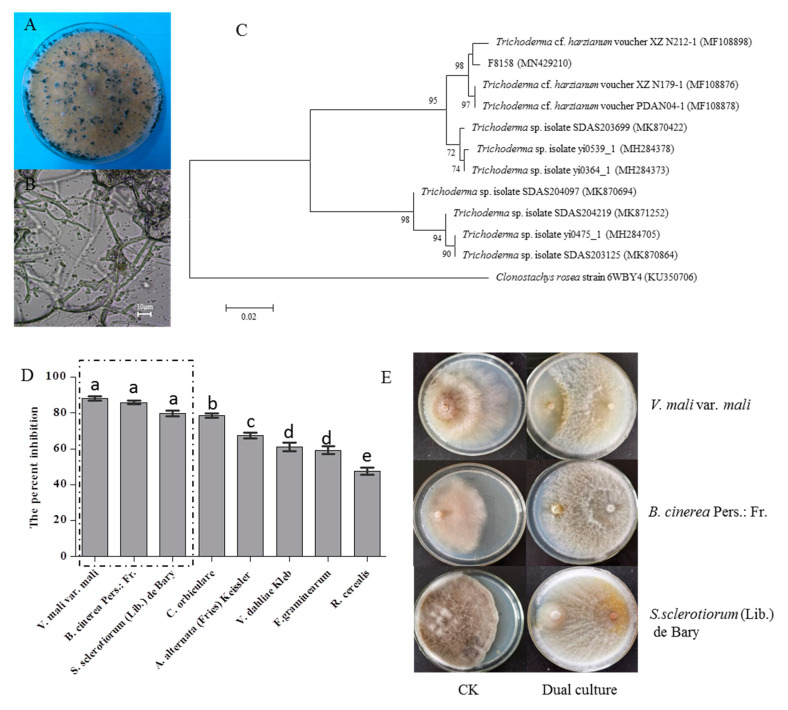

2.4. Identification of the Strain F8158 and Analysis of Its Antagonistic Effect for Different Pathogens

The colonial and microscopic morphology of the strain F8158 on PDA were shown in Figure 2A,B and were similar to those of Trichoderma spp. [17,18]. The isolated fungal culture F8158 was observed as fast growing with a scanty mycelial growth on PDA. During the growth process, mycelia of the strain F8158 spread out in all directions and the colony color turned from white to green. The fungal hyphae of F8158 were hyaline and smooth-walled and the conidiophores are highly branched. A subsequent sequence analysis showed that the isolate F8158 shared 99.66% identity with Trichoderma cf. harzianum voucher PDAN04-1 (MF108878) in the NCBI database (Figure 2C). The strain F8158 exhibited good antagonistic capacities (the percent inhibition of mycelial growth ranged from 47.72–88.18) against different pathogens (Figure 2D). In particular, the average growth percent inhibition of F8158 against V. mali var. mali was the highest and reached 88.17 ± 1.51, followed by B. cinerea Pers.: Fr. with a percent inhibition of 85.97 ± 1.27 and the percent inhibition of S. sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary was 79.87 ± 1.84 (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

The characteristics of the strain F8158. The morphology of the colony (A) and microscopic morphology (B) on a potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium; phylogenetic identification based on ITS1 and ITS4 using the maximum-likelihood methods (C); the percent inhibition against different pathogens (D) and the good antagonistic activity against three pathogens (E) in the dual culture assays.

3. Discussion

Endophytic fungi have a high level of taxonomic diversity [19]. These fungi exist in nearly every tissue type studied and are promising as biological control agents against phytopathogens and bioactive substances [10]. Despite these characteristics, endophytic fungi remain poorly studied. The Qinling Mountains are rich in medicinal plant resources, many of which have been used as traditional Chinese medicines by the local people. In recent years, increasing attention has focused on biodiversity and pharmacological properties of medicinal plants of the Qinling Mountains; however, as far as we know, few studies have attempted to evaluate the diversity of endophytes associated with these valuable plants [20]. In this study, we investigated the diversity of the culturable endophytic fungi from C. japonicus (one of the most popular medicinal plants in Qinling Mountains) and obtained abundant endophytic fungal isolates, which was conducive for screening the active strains and laying a foundation for their application.

At present, the discovery of new compounds was urgent but very difficult from common environments (e.g., soils) [21,22,23]. Researchers have focused on the selection of antimicrobial substances from microorganisms in other ecosystems, particularly those in special habitats, such as marine microorganisms and endophytes [24]. In our research, ethyl acetate extracts of 13 endophytic fungi (10% of total screened strains) showed inhibitory activity against pathogenic microorganisms. Most of the 13 isolates represent fungal genera, including Aspergillus, Diaporthe, and Trichoderma, previously reported to produce antimicrobial compounds [25,26,27]. However, new bioactive compounds are constantly being discovered from plant endophytes. For instance, a new cadinene-sesquiterpenes and seven of its analogues were isolated from an endophytic fungus, Aspergillus flavus, which was isolated from a toxic medicinal plant, Tylophora ovate [28]. Guo et al. isolated a new antibacterial secondary metabolite (Diaporone A) from the plant endophytic fungus Diaporthe sp. [29]. Seven previously unreported cyclonerane derivatives were isolated from the culture of Trichoderma asperellum A-YMD-9-2, an endophytic fungus obtained from the marine red alga Gracilaria verrucosa [30]. In addition, it is noteworthy that the strain F8157 (Thanatephorus cucumeris, an opportunistic pathogen) showed antibacterial and antifungal activity, which is reported firstly in this study, and has the potential research value.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the diversity and antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi isolated from C. japonicus. Thus, the fungi with antimicrobial activity obtained in this study still have the potential to produce new structures natural products. In addition, F8158 exhibited higher antagonistic activity against V. mali var. mali, B. cinerea Pers.: Fr., and S. sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary compared with previous studies and have a potential application in biological control [31,32,33].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Source of Plant Samples

In April 2018, a total of thirty wild plants of C. japonicus were collected from Yingpan town, Shaanxi province of China (33°49′30′′ N, 109°6′15′′ E, elevation, 1340 m). The land we accessed was publicly owned and undeveloped. These plants were carefully dug up, placed in a sterile sampling bag, labeled, immediately transported to the laboratory, and then placed into a refrigerator (4 °C), as described previously [34]. All of the samples were used to isolate endophytic fungi within 48 h after collection.

4.2. Fungal Isolation and Cultivation

The plant tissues were processed with the method described by Qin et al. [35]. In brief, the samples were thoroughly washed in running water for 30 min, followed by an ultrasonic cleaning (200 W, 10 min), and then air-dried for 2 h at room temperature. After drying, the plant samples were surface-sterilized with the protocol described by Tan et al. with minor modifications [36]. Air-dried plant samples were surface-sterilized using sequential washes in 70% ethanol for 1 min, 2.5% NaClO2 for 2 min, and 70% ethanol for 1 min. Following sterilization, leaves were rinsed three times in sterile distilled water. All the samples were then excised into 555 segments of 1–2 mm length. Segments were placed on a PDA medium (house-made, containing (g/L): Agar power 16, potato 200 (peel potatoes, cut into 1 cm pieces, boiled for 20 min, filtered to obtain filtrate), and dextrose 20, pH 6.0) using 90 mm petri plates. The medium was supplemented with amikacin sulfate (100 U/mL) to prevent the growth of bacteria. Seven tissue segments were placed on each petri dish (90 mm), which were then sealed with parafilm and incubated at 28 °C for one week. Emergent fungal colonies were isolated and purified in a PDA medium for further identification and bioactive assays (see below). Pure isolates growing on the PDA medium were photographed and the agar piece plugs with pure isolates were stored at −80 °C in a 20% glycerol solution in the engineering center of QinLing Mountains natural products, Shaanxi provincial institute of microbiology.

4.3. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analyses

To obtain fungal mycelia, each pure isolate was cultivated on plates containing the PDA medium at 28 °C for seven days. Mycelia were removed from media using sterile pipette tips and then ground in liquid nitrogen for DNA extraction using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Bacteria Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Dalian, China). Genomic DNA was then used as the template for PCR amplification of the nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) using the universal primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) according to the description by White et al. with minor modifications [37]. The final reaction volume was 50 μL, containing 5.0 μL of 10×Taq buffers, 4.0 μL of 200 mmol/L dNTPs, 2.0 μL of each primer at 10 μM, 0.5 μL of Ex Taq enzyme (TaKaRa, Dalian), and 5.0 μL of genomic DNA. PCR amplification was performed using TProfessional Standard 96 Gradient (Biometra, Jena, Germany) using the following cycling parameters: 1 min 95 °C; followed by 35 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C; and a final 10 m extension at 72 °C. Five μL of each PCR product was analyzed electrophoretically in 1% (w/v) agarose gels stained with GelRed (Shanghai Generay Biotech Co., Ltd., China). The PCR products were subsequently purified and sequenced by BGI Biotechnology (Shenzheng, China). The raw obtained sequences were aligned using MEGA 5.05 (Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA), edited manually, and then BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) (NCBI, Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to search for the best match in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to identify endophytic fungi. Sequences with similarity over 97% belonged to the same genus. The sequences obtained in this study were submitted to the GenBank database with accession numbers from MK367469 to MK367568. The evolutionary history was inferred as described by Wei et al. and Felsenstein [38,39]. All sequences were aligned by MEGA 5.05 using the alignment prepared with Clustal W (Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA) and all positions containing gaps and missing date were deleted. Finally, the maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed for each of the families using MEGA software 5.05 [40].

4.4. Crude Extract Preparation of Fungal Fermentation Broth

Each isolate was cultured on the PDA for seven days, after which the plugs of each fungus were used to inoculate liquid cultures containing a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing a 50 mL potato dextrose broth (PDB) culture medium (house-made) containing (g/L): 200 potato (peel potatoes, cut into 1 cm pieces, boiled for 20 min, filtered to obtain filtrate), 20 dextrose, pH 6.0. All isolates were incubated on a rotary shaker at 28 °C and 230 rpm for 14 days. The fermentation broth was collected by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 8 min. Fifty mL of fermentation filtrate was extracted with 50 mL ethyl acetate (three extractions total) and the organic phase was concentrated using a rotary evaporator on 50 °C water bath to remove organic solvent as described by Xing et al. with minor modifications [41]. The crude extracts were diluted with pure methanol to 10 mg/mL and sterilized by filtration using an organic filter (0.22 μm, Shanyu Co., Ltd., Shanyu, China).

4.5. Antimicrobial Activity

Using the agar diffusion method described by Wang et al. [42], we screened the ethyl acetate crude extracts from fermentation filtrates of 130 fungal strains for antimicrobial activities against seven pathogens, including Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, and Candida albicans. The detailed operation procedure were as follows: 10 mL culture of the C. albicans grown two days in a Sabouraud liquid medium at 28 °C was added to the 200 mL of the Sabouraud agar medium, while 10 mL cultures of pathogenic bacteria grown 12 h in the Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium (containing (g/L): 5 Yeast extracts, 10 peptone, 10 NaCl, pH 7.0) at 28 °C was added to the 100 mL of the LB agar medium, mixed gently, and then poured slowly on the petri dish (90 mm) used as the test plate. Six mm sterilized straws were used for perforating the plate, and the agar blocks were removed with a sterilized toothpick. The 100 μL fermentation filtrate EtOAc extracts (10 mg/mL) were added to the hole of the test plate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for the pathogenic bacteria or at 28 °C for 48 h for C. albicans. Ampicillin sodium (1 mg/mL) and Actidione (1 mg/mL) were prepared using deionized water and used as a positive antimicrobial control and pure methanol was used as a negative control. Antimicrobial activities were evaluated by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones. All experiments were replicated three times.

4.6. Dual Culture Assay to Detect the Antagonistic Potential of Endophytic Fungi against Different Pathogenic Fungi

The dual culture technique was used to conduct the antagonistic test. The endophytic fungi and pathogen species to be tested were cultured separately on the PDA for seven days. After seven days, 5 mm mycelial plugs (taken from the edge of fungal colonies) of each species were transferred to PDA plates using a borer. The mycelial plugs of endophytic fungi and pathogens were placed on opposite sides to each other on a PDA surface. PDA plates inoculated with the pathogens were included as negative controls. The antagonistic tests were conducted in duplicate. The controls consisted of pure Botrytis cinerea Pers.: Fr., Rhizoctonia cerealis, Valsa mali var. mali, Colletotrichum orbiculare, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary, Fusarium graminearum, Verticillium dahliae Kleb, and Alternaria alternata (Fries) Keissler cultures. All culture plates were incubated at 28 °C and observations were made after five days of incubations. The percent inhibition of mycelia growth over the control was calculated by the following equation:

| I = (C − T)/C × 100 | (1) |

where I is the percent inhibition of mycelial growth, C is the radius of pathogens mycelium with the growth in control, and T is the radius of pathogens mycelia in the treatment.

4.7. Diversity Analyses of the Endophytic Fungi

The isolation frequency (IF) represented the frequency of the occurrence of certain endophytic fungi in total isolates based on the number of isolates (N). The relative abundance (RA) was calculated based on the number of all isolates number (N). The diversity of fungal species from C. japonicus was evaluated using the Species Richness Index (S) and Shannon-Weiner Index (H′) with the procedure described by Fedor and Spellerberg. [43]. The Species Richness Index (S) was obtained by counting the number of endophytic fungal species in the corresponding plant tissues. A total of 130 isolates were participated in the antimicrobial activities assessment in this study.

4.8. Statistical Analyses

All results were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Graphs were prepared using GraphPad Prism 5.0. (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) Significant differences between treatments were evaluated by the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05 using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Conclusions

In this study, the diversity and antimicrobial activities of the endophytic fungi from C. japonicus were investigated for the first time. Our results illustrated that C. japonicus harbored abundant fungal endophytes representing a high level taxonomic diversity. It was found that 13 out of 130 endophytic fungal ethyl acetate extracts exhibited inhibitory activities against at least one of the pathogenic microorganisms. Specifically, the strain F8158, which was identified as Trichoderma cf. harzianum (commonly used as a biocontrol strain in the agricultural production process), exhibited good antagonistic activity against different plant pathogenic fungi and has a potential application in the biological control. In addition, it is noteworthy that the strain F8157 (Thanatephorus cucumeris, an opportunistic pathogen) showed antibacterial and antifungal activity firstly and has the potential research value. Overall, it was indicated that the endophytic fungi from C. japonicus may be of potential interest in screening bio-control agents and discovery of new bioactive compounds.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21576160), the Science and Technology Research Project of Shaanxi Province Academy of Sciences (2018nk-01, 2018k-09), and the Shaanxi Science and Technology Project (2017NY-192; 2018NY-152; 2019NY-209; 2020JM-708), Yulin Science and Technology Project (2019-186). We are also thankful to all our laboratory colleagues especially Xinwei Shi for their experimental help.

Abbreviations

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| IF | Isolation frequency |

| ITS | Internal transcribed spacer |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| RA | Relative abundance |

| SSA | Similarity threshold |

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/17/5958/s1, can be found at the supplementary files. Supplemental files 1. Thanatephorus cucumeris AG-7 (AY154305). Supplemental files 2. Maximum-likelihood phylogenic analyses by internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence alignment for the endophytic fungi from Chloranthus japonicus Sieb belonging to Apiosporaceae (A); Aspergillaceae (B); Bionectriaceae (C); Ceratobasidiaceae (D); Chaetomiaceae (E); Cladosporiaceae (F); Didymellaceae (G); Diaporthaceae (H); Glomerellaceaee (I); Hypocreaceae (J); Didymosphaeriaceae (K); Hypoxylaceae (L); Irpicaceae (M); Mucoraceae (N); Muyocopronaceae (O); Mycosphaerellaceae (P); Nectriaceae (Q); Plectosphaerellaceae (R); Pleosporaceae (S); Trichocomaceae(T); Xylariaceae (U). Supplemental files 3. The raw data for antimicrobial activity.

Author Contributions

C.A., S.M., C.L., and H.D. performed the experiments; C.A. and W.X. designed and supervised the project; X.S. and C.A. collected plant materials for the experiment; C.A. and W.X. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21576160), Science and Technology Research Project of Shaanxi Province Academy of Sciences (2018nk-01, 2018k-09), Shaanxi Science and Technology Project (2017NY-192; 2018NY-152; 2019NY-209; 2020JM-708), Yulin Science and Technology Project (2019-186). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ma T., Hu Y., Russo I.R.M., Nie Y., Yang T., Xiong L., Ma S., Meng T., Han H., Zhang X., et al. Walking in a heterogeneous landscape: Dispersal, gene flow and conservation implications for the giant panda in the Qinling Mountains. Evol. Appl. 2018;11:1859–1872. doi: 10.1111/eva.12686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan J., Zheng X., Cheng F., Zhu X., Hou L., Li J., Zhang S. Fungal community structure of fallen pine and oak wood at different stages of ecomposition in the Qinling Mountains. China. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13866. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14425-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang M., Duan R., Wang S., Wang Z., Fan W. Species presence frequency and diversity in different patch types along an altitudinal gradient: Larix chinensis Beissn in Qinling Mountains (China) PeerJ. 2016;4 doi: 10.7717/peerj.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H.H., Chu H.L., Dou Q., Xie Q.Z., Tang M., Sung C.K., Wang C.Y. Phosphorus and nitrogen drive the seasonal dynamics of bacterial communities in Pinus forest fhizospheric soil of the Qinling Mountains. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1930. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang P.L., Cao Y.L., Yan H., Pan L.L., Liu S.C., Gong N.B., Lu Y., Chen C.X., Zhong H.M., Guo Y., et al. Lindenane Disesquiterpenoids with Anti-HIV-1 Activity from Chloranthus japonicus. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:1408–1413. doi: 10.1021/np200087d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan H., Qin X.J., Li X.H., Yu Q., Ni W., He L., Liu H.Y. Japonicones A-C: Three lindenane sesquiterpenoid dimers with a 12-membered ring core from Chloranthus japonicus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019;60:713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.01.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim S.Y., Nagashima H., Tanaka N., Kashiwada Y., Kobayashi J., Kojoma M. Hitorins A and B, Hexacyclic C25 Terpenoids from Chloranthus japonicus. Org. Lett. 2016;18:5420–5423. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du W., Yao Z., Li J., Sun C., Xia J., Wang B., Shi D., Ren L. Diversity and antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi isolated from Securinega suffruticosa in the Yellow River Delta. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0229589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan A.L., Hussain J., Al-Harrasi A., Al-Rawahi A., Lee I.J. Endophytic fungi: Resource for gibberellins and crop abiotic stress resistance. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2013;35:62–74. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2013.800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta S., Chaturvedi P., Kulkarni M.G., Van Staden J. A critical review on exploiting the pharmaceutical potential of plant endophytic fungi. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020;39:107462. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.107462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora P., Wani Z.A., Ahmad T., Sultan P., Gupta S., Riyaz-Ul-Hassan S. Community structure, spatial distribution, diversity and functional characterization of culturable endophytic fungi associated with Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Fungal Boil. 2019;123:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasaei A., Dehkordi M.M., Mahjoubi F., Saffar B. Isolation of Taxol-Producing Endophytic Fungi from Iranian Yew Through Novel Molecular Approach and Their Effects on Human Breast Cancer Cell Line. Curr. Microbiol. 2017;62:164–709. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gill H., Vasundhara M. Isolation of taxol producing endophytic fungus Alternaria brassicicola from non-Taxus medicinal plant Terminalia arjuna. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;35:74. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan X.M., Zhou Y.Q., Zhou X.L., Xia X.H., Wei Y., He L.L., Tang H.Z., Yu L.Y. Diversity and bioactive potential of culturable fungal endophytes of Dysosma versipellis; a rare medicinal plant endemic to China. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5929. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24313-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payne D.J., Gwynn M.N., Holmes D.J., Pompliano D.L. Drugs for bad bugs: Confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunil K.D., Manish K.G., Ved P., Sanjai S. Endophytic fungi: A source of potential antifungal compounds. J. Fungi. 2018;4:77–119. doi: 10.3390/jof4030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinu K., Sati P., Pandey A. Trichoderma gamsii(NFCCI 2177): A newly isolated endophytic, psychrotolerant, plant growth promoting, and antagonistic fungal strain. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013;54:408–417. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201200579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redda E.T., Ma J., Mei J., Li M., Wu B., Jiang X. Antagonistic Potential of Different Isolates of Trichoderma against Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, and Botrytis cinerea. Eur. J. Exp. Boil. 2018;8 doi: 10.21767/2248-9215.100053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toghueo R.M.K., Boyom F.F. Endophytic Fungi from Terminalia Species: A Comprehensive Review. J. Fungi. 2019;5:43. doi: 10.3390/jof5020043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P., Wu Z., Liu T., Wang Y. Biodiversity, Phylogeny, and Antifungal Functions of Endophytic Fungi Associated with Zanthoxylum bungeanum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1541. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang Z.K., Tuo L., Huang D.L., Osterman I.A., Tyurin A.P., Liu S.W., Lukyanov D.A., Sergiev P.V., Dontsova O.A., Korshun V.A., et al. Diversity, Novelty, and Antimicrobial Activity of Endophytic Actinobacteria From Mangrove Plants in Beilun Estuary National Nature Reserve of Guangxi, China. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:868–879. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X., Li S.J., Li J.J., Liang Z., Zhao C.Q. Novel Natural Products from Extremophilic Fungi. Mar. Drugs. 2018;16:194. doi: 10.3390/md16060194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes A., Rodrigues M.J., Pereira C.G., Oliveira M., Barreira L., Varela J., Trampetti F., Custódio L. Natural products from extreme marine environments: Searching for potential industrial uses within extremophile plants. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016;94:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.08.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayed A.M., Hassan M.H., Alhadrami H.A., Hassan H.M., Goodfellow M., Rateb M.E. Extreme environments: Microbiology leading to specialized metabolites. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;128:630–657. doi: 10.1111/jam.14386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Hawary S.S., Moawad A.S., Bahr H.S., Abdelmohsen U.R., Mohammed R. Natural product diversity from the endophytic fungi of the genus Aspergillus. RSC Adv. 2020;10:22058–22079. doi: 10.1039/D0RA04290K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicoletti R., Vinale F. Bioactive Compounds from Marine-Derived Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and Trichoderma Species. Mar. Drugs. 2018;16:408. doi: 10.3390/md16110408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chepkirui C., Stadler M. The genus Diaporthe: A rich source of diverse and bioactive metabolites. Mycol. Prog. 2017;16:477–494. doi: 10.1007/s11557-017-1288-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z., Zhao J.Y., Sun S.-F., Li Y., Qu J., Liu H.T., Liu Y. Sesquiterpenes from an Endophytic Aspergillus flavus. J. Nat. Prod. 2019;82:1063–1071. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo L., Niu S., Chen S., Liu L. Diaporone A, a new antibacterial secondary metabolite from the plant endophytic fungus Diaporthe sp. J. Antibiot. 2019;73:116–119. doi: 10.1038/s41429-019-0251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song Y.P., Miao F.P., Liu X.H., Yin X., Ji N. Cyclonerane Derivatives from the Algicolous Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma asperellum A-YMD-9-2. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:252. doi: 10.3390/md17050252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva J.A.T., de Medeiros E.V., da Silva J.M., Tenório D.d.A., Moreira K.A., da Silva Nascimento T.C.E., Souza-Motta C. Antagonistic activity of Trichoderma spp. against Scytalidium lignicola CMM 1098 and antioxidant enzymatic activity in cassava. Phytoparasitica. 2017;45:219–225. doi: 10.1007/s12600-017-0578-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wonglom P., Daengsuwan W., Ito S.I., Sunpapao A. Biological control of Sclerotium fruit rot of snake fruit and stem rot of lettuce by Trichoderma sp. T76-12/2 and the mechanisms involved. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019;107:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan S., Li M., Fang Z., Liu Y., Shi W., Pan B., Wu K., Shi J., Shen B., Shen Q. Biological control of tobacco bacterial wilt using Trichoderma harzianum amended bioorganic fertilizer and the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi Glomus mosseae. Boil. Control. 2016;92:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2015.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan X.M., Wang C.L., Chen X.M., Zhou Y.Q., Wang Y.Q., Luo A.X., Liu Z.H., Guo S.X. In vitro seed germination and seedling growth of an endangered epiphytic orchid, Dendrobium officinale, endemic to China using mycorrhizal fungi (Tulasnella sp.) Sci. Hortic. 2014;165:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin S., Li J., Chen H.H., Zhao G.Z., Zhu W.Y., Jiang C.L., Xu L.H., Li W.J. Isolation, Diversity, and Antimicrobial Activity of Rare Actinobacteria from Medicinal Plants of Tropical Rain Forests in Xishuangbanna, China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6176–6186. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01034-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan X.M., Chen X.M., Wang C.L., Jin X.H., Cui J.L., Chen J., Guo S.X., Zhao L.F. Isolation and Identification of Endophytic Fungi in Roots of Nine Holcoglossum Plants (Orchidaceae) Collected from Yunnan, Guangxi, and Hainan Provinces of China. Curr. Microbiol. 2011;64:140–147. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-0045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press; Berkeley, CA, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei W., Zhou Y., Chen F., Yan X., Lai Y., Wei C., Chen X., Xu J., Wang X. Isolation, Diversity, and Antimicrobial and Immunomodulatory Activities of Endophytic Actinobacteria From Tea Cultivars Zijuan and Yunkang-10 (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) Front. Microbiol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing Y.-M., Chen J., Cui J.L., Chen X.M., Guo S.X. Antimicrobial Activity and Biodiversity of Endophytic Fungi in Dendrobium devonianum and Dendrobium thyrsiflorum from Vietman. Curr. Microbiol. 2010;62:1218–1224. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S.S., Liu J., Sun J., Sun Y.-F., Liu J.N., Jia N., Fan B., Dai X.-F. Diversity of culture-independent bacteria and antimicrobial activity of culturable endophytic bacteria isolated from different Dendrobium stems. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10389. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46863-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fedor P.J., Spellerberg I.F. Shannon-Wiener Index. Reference Module. Earth Syst. Environ. Sci. 2013;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.