Abstract

The immune system plays a multifunctional role throughout the regenerative process, regulating both pro-/anti-inflammatory phases and progenitor cell function. In the present study, we identify the myokine/cytokine Meteorin-like (Metrnl) as a critical regulator of muscle regeneration. Mice genetically lacking Metrnl have impaired muscle regeneration associated with a reduction in immune cell infiltration and an inability to transition towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Isochronic parabiosis, joining wild-type and whole-body Metrnl knock-out (KO) mice, returns Metrnl expression in the injured muscle and improves muscle repair, providing supportive evidence for Metrnl secretion from infiltrating immune cells. Macrophage-specific Metrnl KO mice are also deficient in muscle repair. During muscle regeneration, Metrnl works, in part, through Stat3 activation in macrophages, resulting in differentiation to an anti-inflammatory phenotype. With regard to myogenesis, Metrnl induces macrophage-dependent insulin-like growth factor 1 production, which has a direct effect on primary muscle satellite cell proliferation. Perturbations in this pathway inhibit efficacy of Metrnl in the regenerative process. Together, these studies identify Metrnl as an important regulator of muscle regeneration and a potential therapeutic target to enhance tissue repair.

Skeletal muscle has extensive regenerative capabilities due to resident progenitor cells (satellite cells) and a highly coordinated interaction with haematopoietic/immune cells during the repair process. This complex yet efficient process can result in complete restoration of normal morphology and function in healthy muscle. Due to the temporal nature of tissue repair, there are still gaps in the understanding of the interplay between immune and satellite cell functions during the regenerative process. Further understanding of such events could identify therapeutic targets to enhance regeneration and muscle resilience with ageing and in a number of important diseases.

The haematopoietic component of muscle repair has recently received a great deal of investigation. Several cell types have been suggested as key regulators of repair, including innate immune cells, such as eosinophils1 and macrophages2–5, and adaptive immune cells, such as regulatory T cells6–8. The role of macrophages in muscle regeneration is particularly complex due to the phenotypical changes occurring during the initial inflammatory phase and the subsequent anti-inflammatory/regenerative phase9,10. Currently, there is limited understanding of what factor(s) coordinate the transition between pro- and anti-inflammatory phenotypes throughout the regenerative process. Furthermore, there is a limited understanding of how these environments cue satellite cell expansion to help myogenesis and tissue repair.

Metrnl has been recently identified as a myokine that acts as an immune/metabolic regulator in adipose tissue11. It has since been implicated in regulating activity of various cell types, including alternatively activated macrophages12, osteocytes13 and adipocytes14. Moreover, increased Metrnl gene expression has been reported with damage-inducing downhill running11 and other modes of exercise15. The induction of Metrnl during tissue damage and its role in immune regulation suggests the hypothesis that Metrnl plays a broad role in muscle tissue repair. We investigated this question in the specific context of skeletal muscle injury in mice and humans.

In the present study, we describe a role for Metrnl in coordinating skeletal muscle repair through macrophage accretion and phenotypical switch. Our results suggest that Metrnl secretion occurs predominantly from macrophages in response to local injury. Furthermore, we show that Metrnl also works directly on macrophages through a Stat3-dependent auto-/paracrine mechanism. This promotes an anti-inflammatory function and induction of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which activates muscle progenitors to help myogenesis.

Results

Metrnl is necessary for successful muscle regeneration

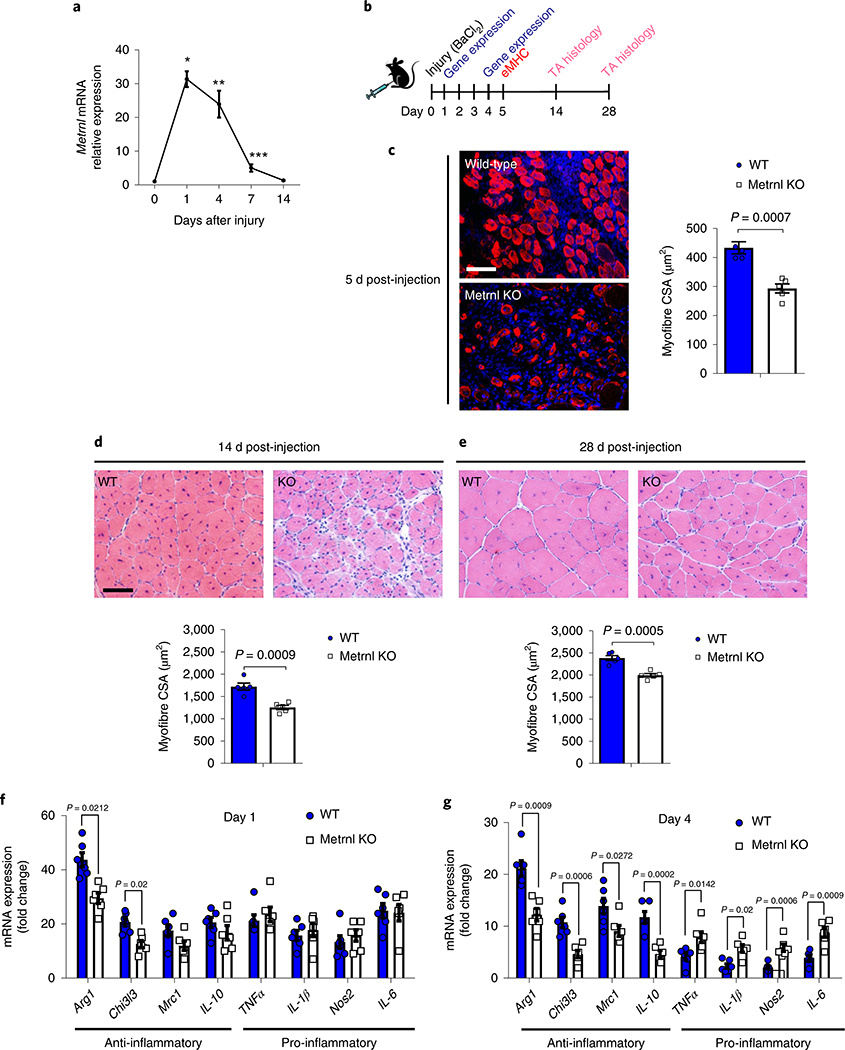

We first determined a time course of Metrnl messenger RNA expression in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle before and throughout 14 d of recovery from an injection of barium chloride (BaCl2). This injectable myotoxin is used in a well-established murine model of muscle regeneration16,17. A robust increase in Metrnl mRNA expression (~30-fold) was observed by 24 h after injury, with sustained elevation for the initial 7 d of recovery (Fig. 1a). The potential physiological relevance to humans was evidenced by an increase in Metrnl mRNA expression in human muscle 18 h after unaccustomed resistance training, which can be highly damaging to muscle18 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). To investigate the importance of Metrnl in muscle regeneration, we injured muscle of whole-body Metrnl KO mice with BaCl2 and compared recovery with that in wild-type controls (Fig. 1b). The Metrnl KO has no evident morphological phenotype in a sedentary, uninjured state (Extended Data Fig. 1b). In the context of muscle injury, the genetic loss of Metrnl resulted in a reduction in cross-sectional area of myofibres expressing embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC), a marker for early myofibre regeneration (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the myofibre cross-sectional area was reduced at 14 d (Fig. 1d) and 28 d (Fig. 1e) of recovery when compared with that in wild-type muscle.

Fig. 1 |. Metrnl is necessary for successful muscle regeneration.

a, Metrnl mRNA expression in the TA throughout 14 d of recovery from BaCl2 injury (n = 5 per group). Asterisks indicate the means that are significantly different from controls: *P = 0.0002, **P = 0.0045, ***P = 0.0211. b, Experimental design showing the time scale of BaCl2 injection and tissue analysis at 5 d (eMHC), 14 d (H&E stain) and 28 d (H&E stain) post-injection. c, The eMHC staining (left) and quantification of eMHC+ fibres’ cross-sectional area (right) in WT and Metrnl KO TA muscle (n = 5 per group). CSA, cross-sectional area. Scale bar, 100 μm. d, TA muscle H&E staining (upper) at 14 d after injury and related myofibre cross-sectional area (lower) (n = 5 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. e, TA muscle H&E staining (upper) and related myofibre cross-sectional area (lower) 28 d after injury (n = 5 per group). f,g, Whole-muscle mRNA expression of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory macrophage makers at 1 d post-injury (f) and 4 d post-injury (g) (n = 6 for both groups). Two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test (a,c–g). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

We previously observed Metrnl regulating the immune milieu in murine adipose tissue11. We investigated changes in muscle inflammatory profiles at 1 and 4 d after BaCl2-induced injury. Compared with that in wild-type muscle, at 1 d post-injury, gene expression was reduced 32% and 37% for anti-inflammatory genes Arg1 and Chil3l3, respectively, whereas the expression of pro-inflammatory genes did not change (Fig. 1f). At 4 d post-injury, the induction of mRNA for anti-inflammatory macrophage genes Arg1, Chi3l3 and Mrc1 decreased by 40%, 64% and 36%, respectively, compared with that in wild-type muscle (Fig. 1g). Moreover, at 4 d post-injury there was an approximately twofold increase in expression of pro-inflammatory marker RNAs TNFα, IL-1β, Nos2 and IL-6 in the Metrnl KO muscle, compared with wild type. These effects were not due to differences in the baseline inflammatory environment because, before injury, there were no differences in gene expression between uninjured wild-type muscle and Metrnl KO muscle (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

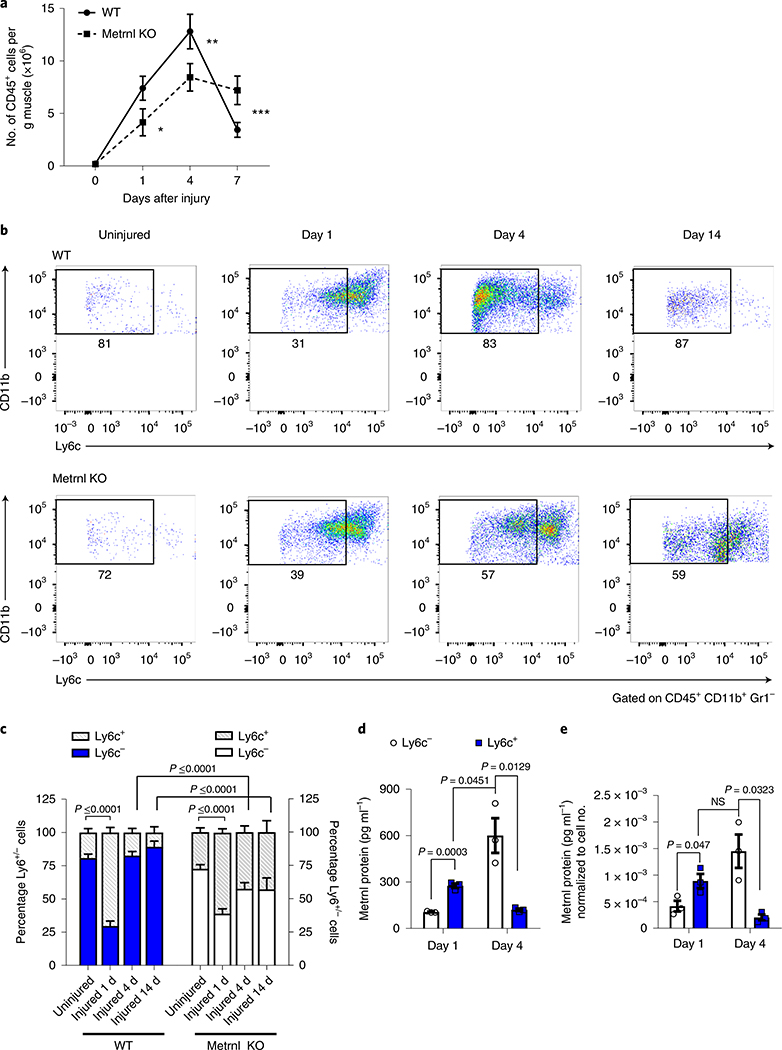

In addition to altered gene expression, compared with wild-type muscle, the Metrnl KO muscle also showed a 36% reduction in total numbers of CD45+ cells infiltrating injured muscle 1 d after injury, a 32% reduction at 4 d and a 110% increase in cells at 7 d (Fig. 2a). We further quantified inflammatory cell phenotype in injured muscle with the monocytic Ly6c marker (Supplementary Fig. 1). Injured wild-type muscle was characterized by an abundance of pro-inflammatory cells (high numbers of Ly6c+ cells) at 1 d after injury, followed by a shift to a less inflammatory state (low numbers of Ly6c+ cells) at 4 and 14 d after injury, consistent with marking entry into the anti-inflammatory or regenerative phase of tissue repair (Fig. 2b,c). Although the Metrnl KO mouse showed a high percentage of Ly6c+ cells 1 d after injury, there was no subsequent decline in the Ly6c+ cell numbers at 4 or 14 d after injury. Thus, the loss of Metrnl results in altered immune cell accretion and phenotype in injured muscle. In terms of protein expression, we measured Metrnl protein in the media of both Ly6c+ and Ly6c− cell groups at both time points after injury. Then, 1 d after injury, the Ly6c− cells increased Metrnl protein secretion; Metrnl secretion was further increased by the Ly6c+ cells 4 d after injury (Fig. 2d). Similar trends were observed when protein expression was normalized to cell number (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2 |. Metrnl deletion alters immune cell migration and phenotype in injured muscle.

a, Total counts of CD45+ cells in muscle throughout 7 d of recovery (n = 5 per group). Asterisks indicate the means that are significantly different from controls: *P = 0.0029, **P = 0.0016, ***P = 0.006. b, Immune inflammatory profile showing CD45+, CD11b+, Gr1− cells stained with Ly6c to show pro- and anti-inflammatory status (n = 5 biologically independent samples). c, Quantification of percentage Ly6c+/− cells in uninjured and 1, 4 and 14 d post-injury, wild-type and Metrnl KO muscle (n = 4 or 5 per group). d, Metrnl protein expression in medium from cultured Ly6c+/− cells sorted 1 and 4 d after injury (n = 3 per group). e, Metrnl protein expression in the medium normalized to cell number (n = 3 per group). NS, not significant. Two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test (a); one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (c); and multiple, two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-tests (d,e). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

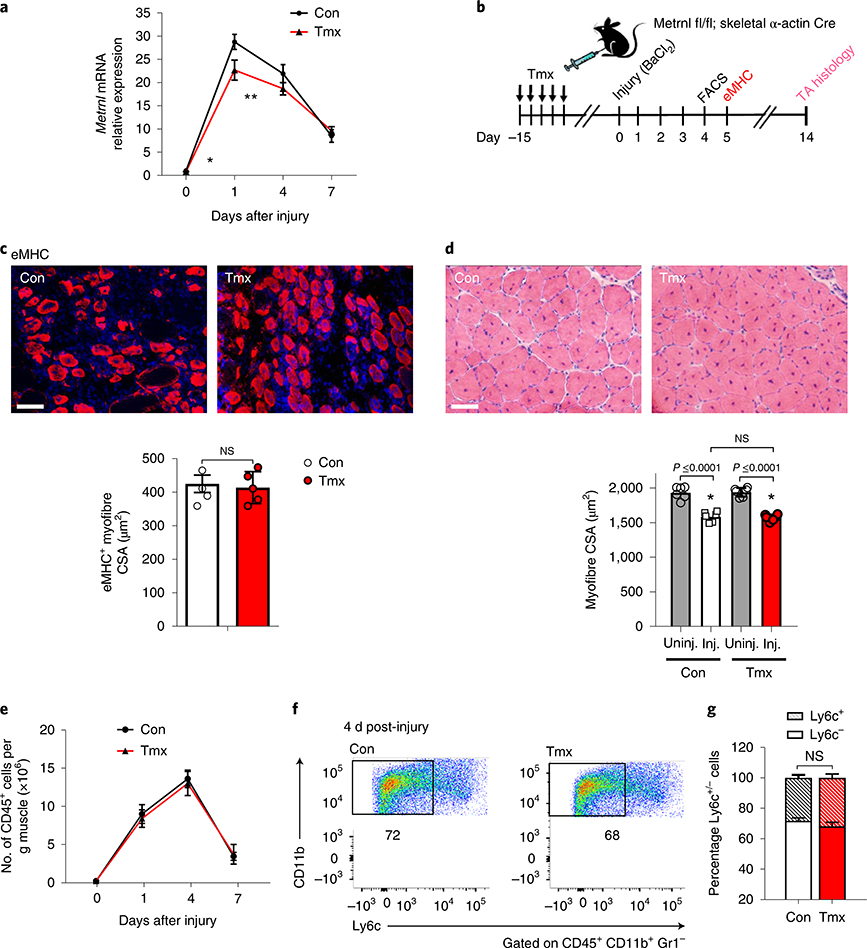

Myofibre-specific Metrnl expression is dispensable for muscle regeneration

We have previously shown Metrnl to be secreted from whole muscle and cultured myotubes11. Therefore, we used a Metrnl floxed mouse crossed with an inducible skeletal muscle-specific (skeletal α-actin) Cre mouse to generate a myofibre-specific Metrnl KO. The cross was effective in reducing ~90% of Metrnl gene expression in uninjured muscle after tamoxifen treatment. Furthermore, we confirmed that the Metrnl KO was specific to skeletal muscle (Extended Data Fig. 2a). In response to injury, the loss of muscle Metrnl reduced mRNA expression in muscle only 20% after 1 d of recovery, and was not different at 4 or 7 d after injury when compared with that in control (corn oil-treated) mice (Fig. 3a). We then assessed muscle regenerative potential using eMHC staining and histology after BaCl2 injury (Fig. 3b); eMHC staining and histology appeared similar in both tamoxifen-treated and control groups at 5 and 14 d, respectively (Fig. 3c,d). Consistent with histological measurements, the number of CD45+ cells infiltrating injured muscle throughout 7 d of recovery was similar for muscle-specific Metrnl KO and control mice (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, the Ly6c staining pattern 4 d after injury was similar between groups (Fig. 3f,g). These data support the premise that an exogenous (outside muscle cells themselves) source of Metrnl may regulate muscle regeneration.

Fig. 3 |. Myofibre-specific Metrnl mRNA expression is not required for successful muscle regeneration.

a, Metrnl mRNA expression through 7 d of recovery in Metrnl fl/fl × skeletal α-actin Cre mice treated with control or tamoxifen (n = 6 per group). Asterisks indicate the means that are significantly different from controls: *P = 0.0004, **P = 0.0475. Con, control; Tmx, tamoxifen. b, Experimental design to induce Cre recombinase in an inducible skeletal muscle Cre line, followed by BaCl2-induced muscle injury and subsequent cellular and histological measurements. c, The eMHC staining 5 d after injury in the TA muscle from Metrnl fl/fl × skeletal α-actin Cre mice (n = 5 per group). CSA, cross-sectional area. d, TA myofibre cross-sections stained for H&E after 14 d of recovery from BaCl2 injury (n = 6 per group). Inj., injured; Uninj., uninjured. Scale bars, 100 μm. e, Quantification of TA muscle CD45+ immune cells throughout 7 d of recovery from injury (n = 5 per group). f, Ly6c staining after 4 d of recovery (n = 5 biologically independent samples). g, Quantification of percentage of Ly6c+ cells within the CD45+, CD11b+, Gr1− population (n = 5 per group). Multiple, two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test (a,e); two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test (c,g); ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (d). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

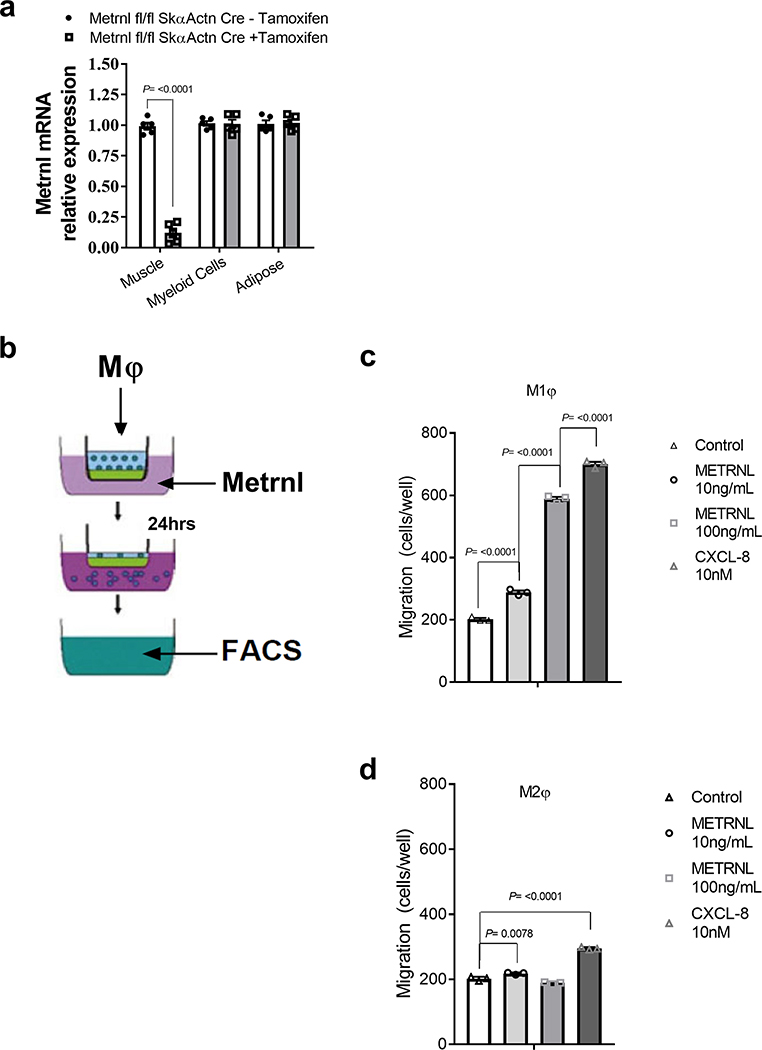

As the Metrnl KO muscle showed fewer immune cells on injury, we next evaluated potential chemokine properties of Metrnl for attracting macrophages. Pro-inflammatory/M1 and anti-inflammatory/M2 macrophages were generated by treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; M1) or interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13 (M2). An in vitro migration assay (Extended Data Fig. 2b) showed selective affinity of M1 macrophages to migrate to Metrnl, especially at the 100 ng ml−1 Metrnl dose that yielded similar chemotactic activity to the positive control, chemokine CXCL-8 treatment (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Migration of M2 macrophages increased at the lower Metrnl dose, but to a much lesser extent (Extended Data Fig. 2d).

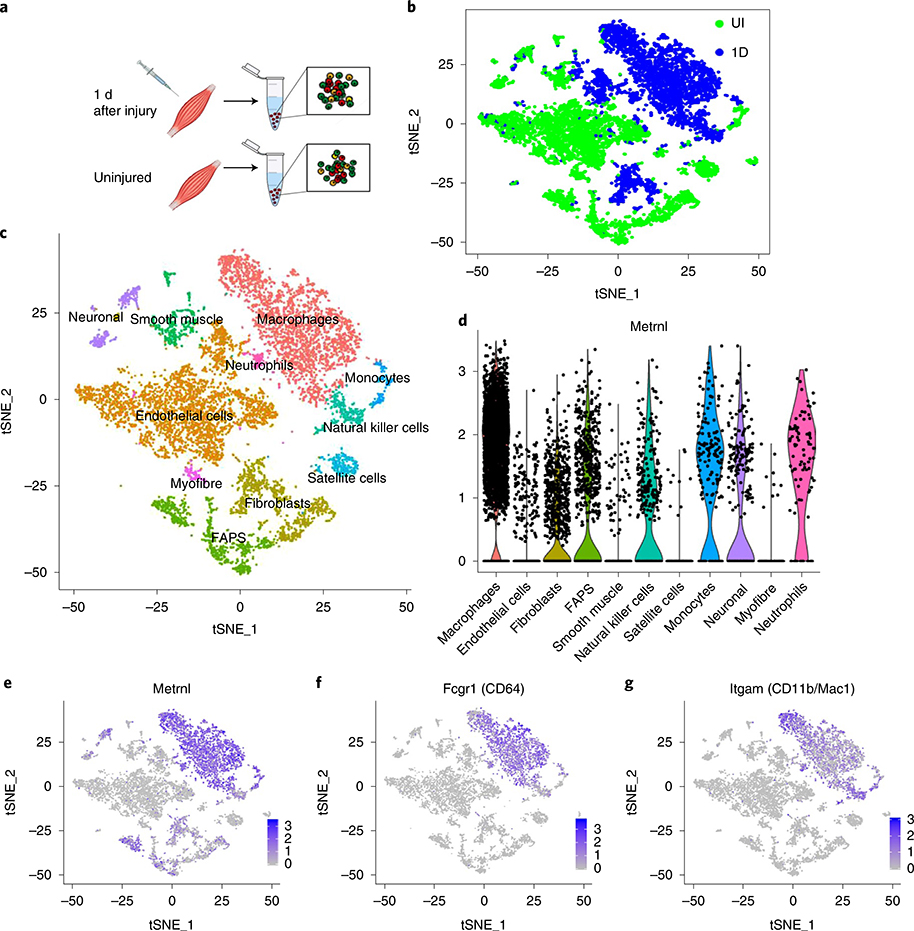

Injury-induced Metrnl expression is largely due to an influx of immune cells

To determine the source of Metrnl in muscle injury, we performed single-cell RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on TA muscle 1 d after injury and on the uninjured control (Fig. 4a). Cluster analysis of these data showed distinct cellular phenotypes between injured and uninjured muscle (Fig. 4b,c), predominantly due to the influx of immune cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). Violin and gene cluster plots revealed that Metrnl expression among the cell populations was prominent in the post-injury macrophage cluster (Fig. 4d,e). This population highly expressed the macrophage markers CD64 (Fig. 4f) and CD11b/Mac1 (Fig. 4g). We hypothesized that a macrophage source of Metrnl should result in rescue of dysfunctional recovery after injury in the whole-body, Metrnl KO mouse. Therefore, we anastomosed two mouse pairs (KO–KO and wild-type (WT)–KO) for 3 weeks, then injured the TA muscle of the KO mouse (Fig. 5a). At 14 d after injury in the Metrnl KO host of the WT–KO pair, there was improved muscle morphology (Fig. 5b), including increased myofibre cross-sectional area (Fig. 5c). Parabiosis yielded the return of Metrnl mRNA expression after injury in the Metrnl KO host of the WT–KO pair (Fig. 5d), confirming the necessity for peripheral immune cells to express Metrnl and help regeneration. To test the role of macrophage-secreted Metrnl in muscle regeneration, we crossed the Metrnl floxed mouse with a constitutive macrophage-specific (LysM) Cre mouse. The Metrnl floxed mouse without the LysM Cre allele served as a control. After injury, the deletion of Metrnl from macrophages reduced total muscle Metrnl mRNA by ~80% at day 1 and 55% at day 4 after injury (Fig. 5e). We next assessed regenerative consequences of macrophage-specific Metrnl KO (Fig. 5f). CD45+ immune cell accretion was reduced 4 and 7 d after injury in the Cre+ mice (Fig. 5g). At 5 d after injury, there was a reduction in the cross-sectional area of eMHC+ fibres (Fig. 5h,i). At 14 d after injury, the myofibre cross-sectional area was reduced together with a robust immune cell presence (Fig. 5j,k) when compared with those in Metrnl fl/fl Cre− muscle. We included the Metrnl KO muscle in the experiment to show similar perturbations in gross histology between the macrophage-specific and whole-body KOs. Moreover, we observed a high percentage of pro-inflammatory Ly6c+ cells at day 4, similar to what is observed in the whole-body KO (Fig. 5l,m). These data support the hypothesis that macrophage-mediated Metrnl expression is critical for successful muscle regeneration.

Fig. 4 |. Metrnl gene expression after injury is identified in macrophage populations.

a, Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of uninjured and injured muscle (1 d after injury). b, Batch plot showing cell populations present in uninjured (green) and injured (blue) groups (n = 1 per group). c, The t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (tSNE) plots showing various cell populations in the uninjured and injured muscle (n = 1 per group). d, Violin plot of Metrnl expression throughout the identified cell clusters. Each dot represents individual cells and their relative gene expression. FAPS, fibro-/adipogenic progenitors. e–g, Gene expression plots of Metrnl (e), CD64 (f) and CD11b (g) (n = 1 per group).

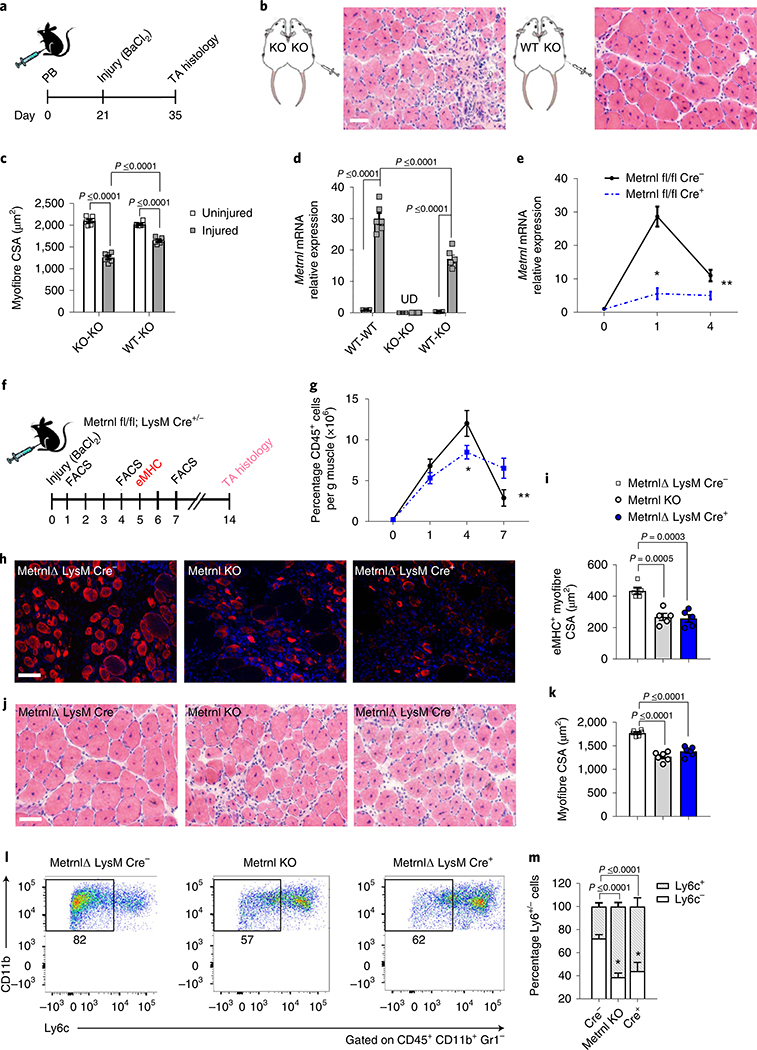

Fig. 5 |. Macrophage-mediated Metrnl expression is necessary for successful muscle regeneration.

a, Experimental design of parabiosis, BaCl2-induced muscle injury and the time course of recovery. b, TA cross-sections of injured Metrnl KO mice anastomosed to Metrnl KO or WT donor mice (n = 6 biologically independent samples). Muscles were harvested 14 d after injury. c, Myofibre cross-sectional area from uninjured and injured Metrnl KO muscle during anastomosis with WT or Metrnl KO mice (n = 6 per group). d, Metrnl mRNA expression in uninjured and injured host muscle. Pairs include WT–WT, KO–KO and WT–KO (n = 5 per group). e, Whole-muscle Metrnl mRNA expression through 4 d of recovery from injury in Metrnl fl/fl × LysM Cre+/− mice (n = 5 per group). Asterisks indicate the means that are significantly different from controls: *P = 0.0025, **P = 0.0449. f, Experimental design of BaCl2-induced muscle injury and the time course of assays used to assess regeneration in the Metrnl fl/fl × LysM Cre mice. g, Quantification of CD45+ cells in the TA muscle throughout a 7-d recovery period (n = 5 per group). Asterisks indicate the means that are significantly different from controls: *P = 0.0022, **P = 0.0009. h, The eMHC staining after 5 d of recovery in Metrnl KO and Metrnl fl/fl × LysM Cre+/− mice (n = 5 biologically independent samples). i, Quantification of eMHC+ myofibre cross-sectional area 5 d after injury (n = 5 per group). j, Myofibre cross-sections stained with H&E 14 d after injury in Metrnl KO and Metrnl fl/fl × LysM Cre+/− (n = 6 biologically independent samples). k, Quantification of TA muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) (n = 6 per group). l, LysM staining in the TA muscle after 4 d of recovery from injury in Metrnl KO and Metrnl fl/fl × LysM Cre+/− mice (n = 5 biologically independent samples). m, Quantification of percentage LysM+/− populations (n = 5 per group). Scale bars, 100 μm. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (c,d); multiple, two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-tests (e,g); one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (i,k,m). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

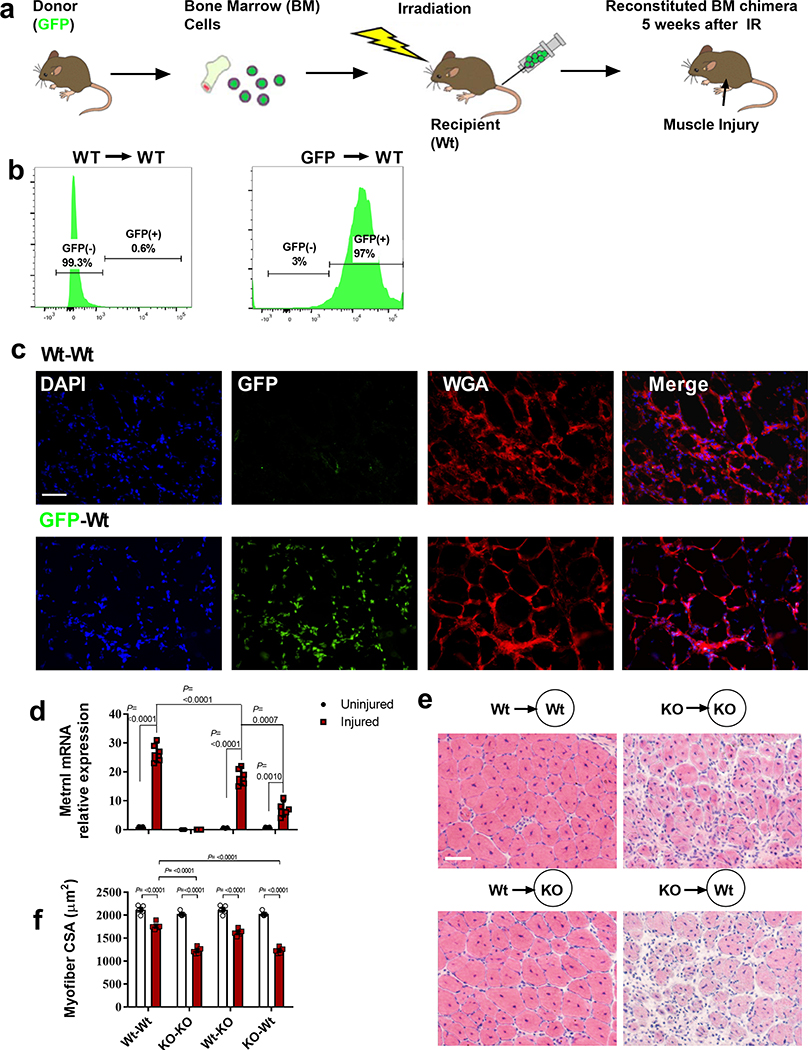

To confirm the role of peripheral macrophages contributing to Metrnl mRNA expression and subsequent promotion of muscle repair, bone marrow transplantation was performed to determine whether the WT haematopoietic compartment could rescue muscle repair in the Metrnl KO mouse (and the reciprocal experiment of KO marrow into the WT mouse) (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Bone marrow transplantation resulted in a near-complete renewal of the recipient haematopoietic compartment. When marrow from a green fluorescent protein (GFP) donor mouse was transplanted into a WT mouse we observed >98% GFP+ peripheral blood cells in the WT recipient (Extended Data Fig. 3b). We also observed the repopulated GFP+ cells migrating into the injured muscle (Extended Data Fig. 3c). The WT donor cells could induce robust Metrnl mRNA expression in both WT and KO recipient muscle after injury. When Metrnl KO marrow was transplanted into a WT recipient, there was a marked reduction in Metrnl expression after injury (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Myofibre cross-sectional area was highest in all conditions where WT marrow was transplanted into a host, regardless of host genotype (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f).

Metrnl signals directly to macrophages through Stat3 and indirectly to satellite cells by IGF-1 production

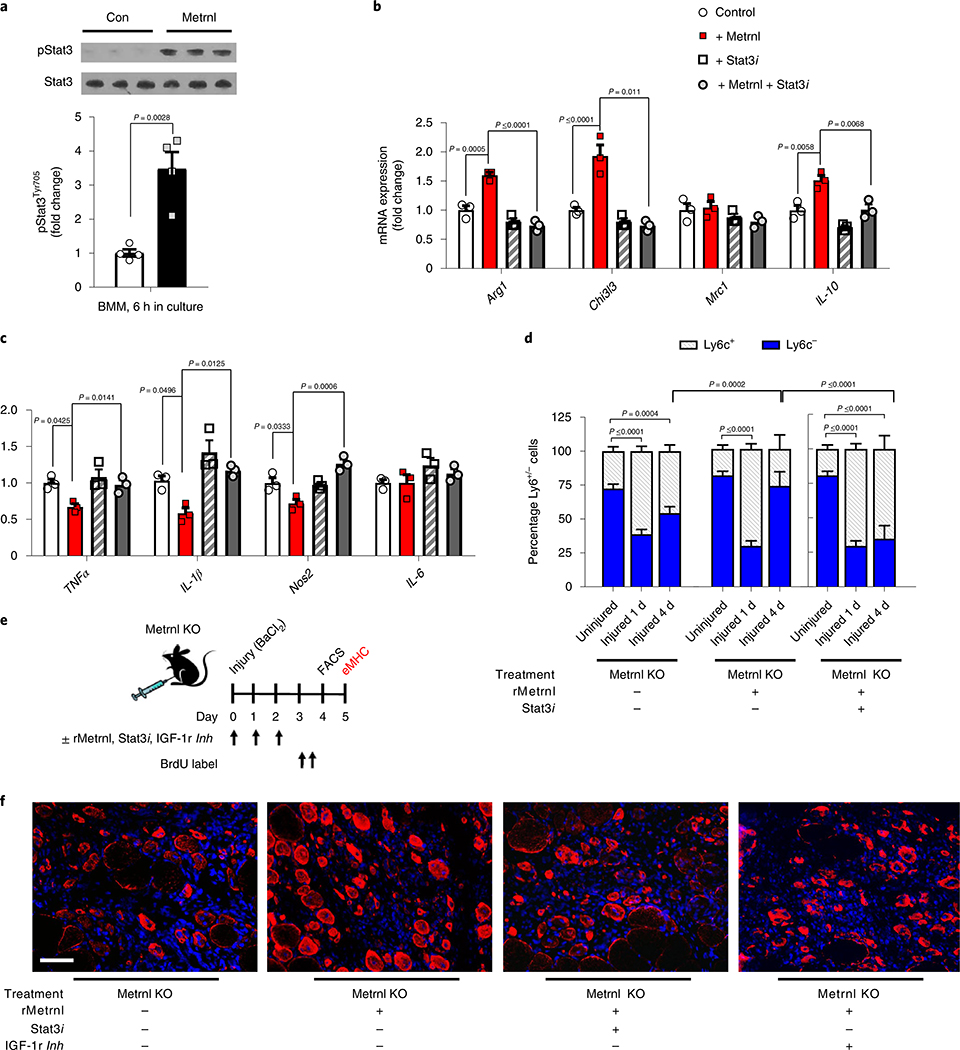

To determine whether Metrnl has a direct effect on macrophages, we treated naive/M0-like bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) with or without Metrnl and measured canonical immune signalling pathways. Phosphorylation of Stat3 was increased after 6 h of Metrnl treatment (Fig. 6a). As Metrnl can directly signal to macrophages through Stat3, we tested the effects of Metrnl ± Stat3 inhibitor on pro-inflammatory BMMs. After 24 h of Metrnl treatment there was an induction of anti-inflammatory markers including Arg1, Chi3l3 and IL-10, which were ablated by the addition of the Stat3 inhibitor (Fig. 6b). In contrast, Metrnl suppressed several pro-inflammatory genes, which, again were prevented by the Stat3 inhibitor (Fig. 6c). Next, we wanted to test the Metrnl/Stat3 pathway in vivo using a treatment combination of recombinant Metrnl and the Stat3 inhibitor. We show that Metrnl KO muscle treated with recombinant Metrnl results in an anti-inflammatory cell phenotype 4 d after injury. This effect was inhibited with concomitant treatment with a Stat3 inhibitor (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6 |. Metrnl signals directly to macrophages through Stat3 and indirectly to satellite cells through IGF-1.

a, Stat3 phosphorylation in BMMs with or without treatment (6 h) of recombinant Metrnl (100 ng ml−1) (n = 4 per group). Pro-inflammatory macrophages were treated with Metrnl and/or a Stat3 inhibitor for 24 h. b,c, Macrophage mRNA expression of anti-inflammatory (b) and pro-inflammatory (c) genes after treatment (n = 3 per group). d, Quantification of percentage Ly6c+/− populations in the TA muscle 1 and 4 d after injury with or without recombinant Metrnl (rMetrnl) and/or a Stat3 inhibitor (Stat3i) (n = 5 per group). e, Experimental design of f and Supplementary Fig. 6f. TA muscle of Metrnl KO mice was treated with a combination of recombinant Metrnl, Stat3 inhibitor and IGF-1 receptor inhibitor during and after injury, and assessed for satellite cell proliferation and muscle regeneration. f, The eMHC staining 5 d after injury with or without recombinant Metrnl or Stat3 inhibitor (n = 6 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. Two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test (a) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (b,c,d). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

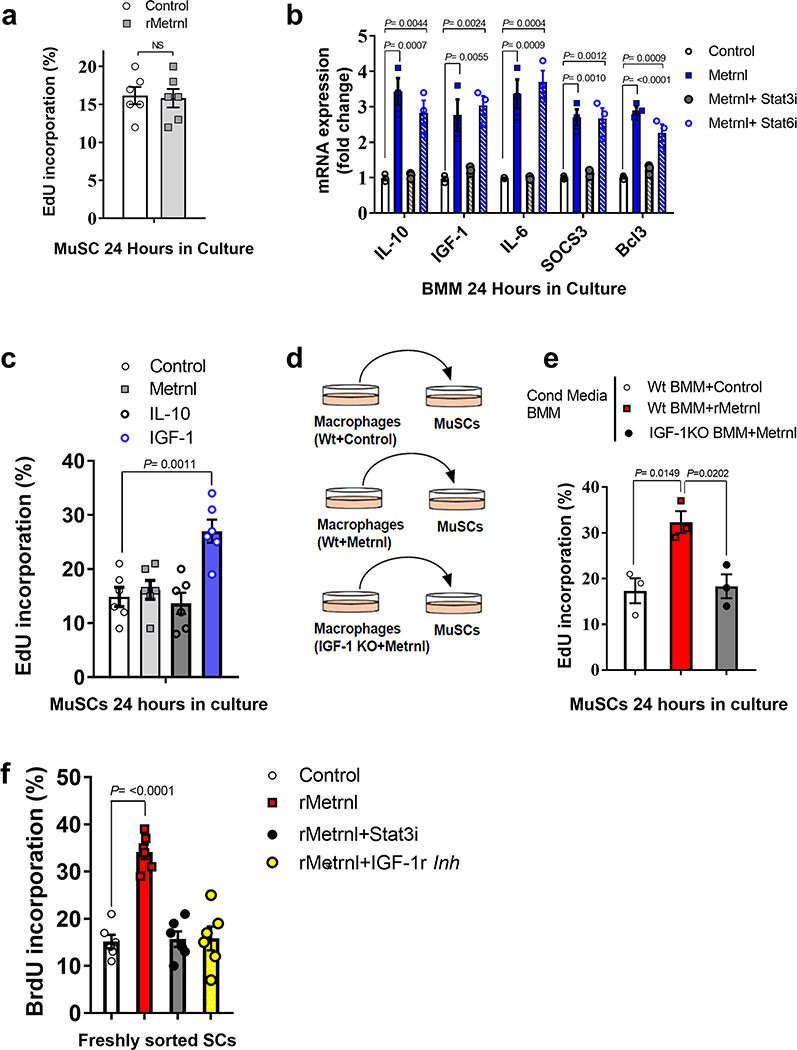

Although Metrnl appears to signal directly to macrophages by Stat3, there is no effect of Metrnl treatment on muscle stem cells (MuSCs) (Extended Data Fig. 4a). This leaves an open question with regard to the mechanism by which Metrnl promotes satellite cell proliferation during regeneration. We treated BMMs with Metrnl for 24 h and measured mRNA of known myogenic factors that could signal to the satellite cell. After 24 h of treatment, we observed increased mRNA expression of known Stat3 gene targets, including Socs3 and Bcl3, but also saw an increase in IGF-1, IL-10 and IL-6 (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Interestingly, these genes were dependent on Stat3 signalling, because treatment with a Stat3 inhibitor blocked expression. We also treated BMMs with a Stat6 inhibitor to determine whether IL-4-related signalling was involved in the Metrnl-induced gene expression. Inhibition of Stat6 did not alter gene expression in the BMMs treated with Metrnl (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Next, we treated cultured MuSCs with recombinant IGF-1 and IL-10, two known factors induced by Metrnl that are involved in myogenesis4,5. Only IGF-1 increased MuSC proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 4c). We then used conditioned medium from BMMs as a treatment for MuSCs (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Metrnl-treated BMMs resulted in an increase in satellite cell proliferation compared with that in control treated BMMs (Extended Data Fig. 4e). As IGF-1 was the only Metrnl-induced BMM factor that directly increased MuSC proliferation, we repeated the experiment in IGF-1 KO BMMs and observed no increase in satellite cell proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 4e), suggesting IGF-1 as a potential myogenic mechanism within the Metrnl pathway. We tested this hypothesis in vivo using the Metrnl KO muscle treated with a combination of recombinant Metrnl, Stat3 inhibitor and IGF-1 receptor inhibitor (Fig. 6e). Treatment with recombinant Metrnl to injured Metrnl KO muscle resulted in an increase in satellite cell proliferation 4 d after injury, as indicated by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (Extended Data Fig. 4f). This effect was blocked by cotreatment with either the Stat3 inhibitor or the IGF-1 receptor inhibitor (Extended Data Fig. 4f). At 5 d after injury, the cross-sectional area of eMHC+ myofibres increased with recombinant Metrnl, which was also negated with both Stat3 and IGF-1 receptor inhibition (Fig. 6f).

Discussion

The immune–muscle interaction during muscle repair has emerged as a critical process for successful regeneration. In the present study, we identify Metrnl, a macrophage-secreted factor, as a crucial factor regulating muscle regeneration through immune cell recruitment and promotion of the anti-inflammatory/regenerative immune environment. We show Metrnl signals directly to macrophages through a Stat3-dependent mechanism, while activating satellite cells indirectly through macrophage-induced IGF-1 secretion (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Metrnl has previously been shown to modulate the immune environment in adipose tissue by promoting an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype11. We have extended this mechanism in the context of skeletal muscle repair. The robust Metrnl expression (increased 30-fold) in the initial days after injury suggested a role in muscle repair. The hypothesis was confirmed on observations of perturbed regeneration in the whole-body Metrnl KO mouse. Importantly, we also observed increased expression in human skeletal muscle after unaccustomed resistance exercise, an established model of muscle damage18. Although muscle-selective Metrnl deletion had minimal impact on total muscle mRNA in the initial days after injury, it was clear that most Metrnl expression comes from infiltrating immune cells.

The work of Ushach et al.12 led us to explore the possibility that most Metrnl expression originated from infiltrating macrophages. The importance of macrophages in muscle regeneration is well known10,19, although the diverse function of macrophages during the repair process makes it difficult to ascertain an exact mechanism. Serving in both pro- and anti-inflammatory roles, the macrophage has equally important roles in phagocytosis of injury-related debris, paracrine immune cell regulation, and promotion of myofibre and extracellular matrix expansion. A growing list of macrophage-derived factors promoting muscle regeneration has been identified. This list, although not comprehensive, includes IL-10 (ref. 5), CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2)20, IGF-1 (ref. 4) and a disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS1)2. Our data suggest that Metrnl can be included in this list of immune factors regulating muscle regeneration.

Single-cell RNA-seq confirmed the high expression of Metrnl in macrophage populations in the injured muscle. Although macrophage clusters expressed most of the Metrnl, we detected expression in other immune cell populations, including neutrophils, monocytes and natural killer cells. These cells could also contribute to the induction of Metrnl during the initial days after injury. Other non-immune populations such as fibro-/adipogenic progenitors had high levels of Metrnl expression. These cell populations will be considered in future experiments. Together, our single-cell RNA-seq data and in vivo mouse models provide strong evidence that, soon after injury, Metrnl originates predominantly from macrophages.

In the present study, we show that Metrnl signals to macrophages through Stat3 and induces gene expression of several growth factors with known functions in muscle regeneration, including IL-10, IGF-1 and IL-6 (refs. 4,5,21). Metrnl-induced expression of these factors was dependent on Stat3 signalling rather than the canonical IL-4/Stat6 mechanism commonly associated with differentiation of alternatively activated/M2 macrophages. Stat3 signalling in the macrophage is paradoxical because both the pro-inflammatory IL-6 and the anti-inflammatory IL-10 pathways converge on Stat3. Still, Stat3 signalling has been shown to promote macrophage differentiation into the M2/anti-inflammatory phenotype22,23 and appears to be a mechanism for Metrnl to promote the anti-inflammatory/regenerative potential of muscle regeneration. Moreover, Metrnl induces macrophage gene expression of both pro- (IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IGF-1/IL-10) genes24 which could default to the anti-inflammatory side of Stat3 signalling; this is observed during dual treatment of IL-10 and IL-6 (ref. 25). Moreover, macrophage-derived IGF-1 secretion is intriguing due to its phenotypical effects on macrophages and stimulation of satellite cell proliferation4. Lu et al.26 showed that IGF-1 mRNA expression increased in both Ly6c− and Ly6c+ macrophages 3 d after injury. These observations could be interpreted as a transition point between the 1- and 4-d time points shown in the present study. In congruence, we observed an increase in Metrnl protein secretion from Ly6c+ macrophages 1 d after injury and Ly6c− macrophages 4 d after injury, when each respective cell population is predominant in injured muscle.

Proliferation of muscle satellite cells is critical for successful regeneration. Although Metrnl does not directly activate satellite cells, it promotes macrophage-mediated IGF-1 expression, which serves to activate satellite cells. Although IL-10 has been implicated in promotion of myogenesis during regeneration and other models of muscle hypertrophy5, it failed to directly activate MuSCs in culture. This is in agreement with the work of Deng et al.5. In addition, Castiglioni et al.7 previously observed low expression of the IL-10 receptor on the satellite cell. In contrast, based on our own single-cell data, the IGF-1 receptor is highly expressed on the satellite cell. Inhibition of IGF-1 and Stat3 signalling neutralized the myogenic effects of Metrnl in vivo, suggesting a Stat3/IGF-1 myogenic pathway for Metrnl to promote muscle regeneration. Limitations of those experiments are the use of the small-molecule IGF-1 receptor inhibitor AG1024 and the Stat3 inhibitor. Although both are often used to block IGF-1 (refs. 27–29) and Stat3 (ref. 30) signalling, respectively, they may be non-specific and inhibit off-target kinases in the various cell types present during muscle regeneration. Genetic targeting blockage of IGF-1 and Stat3 signalling will be considered in future experiments.

Together these results show that Metrnl is a critical regulator of muscle regeneration acting directly on immune cells to promote an anti-inflammatory/pro-regenerative environment and myogenesis. The efficacy of recombinant Metrnl in rescuing the regenerative perturbations of the Metrnl KO muscle suggests potential therapeutic approaches to enhance regeneration with ageing or other inflammatory myopathies including Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J (WT) mice were used at age 3–5 months. All animal care followed the guidelines and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Duke Medical Center. The Metrnl KO mouse has been previously described by Rao et al.11. The skeletal α-actin Cre was purchased from Jackson Laboratories. The Cre recombinase was induced with intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen 100 mg kg−1 d−1 for 5 consecutive days. The Metrnl floxed and LysM Cre mice were generously given to us by Benjamin Alman.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and MuSCs

Skeletal muscle was dissected (roughly 2 g per mouse) and isolated using the methods previously described31. Briefly, dissected muscle was distributed evenly to gentleMACS C tubes (Miltenyi Biotec) containing 15 ml of a collagenase–dispase solution (2.4 U ml−1 of dispase, Gibco; 2 mg ml−1, Sigma). The muscle was incubated at 37 °C in a water bath for 45 min and subjected to dissociation using a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) every 15 min. Heat-inactivated horse serum, 1 ml (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), was added to each tube to halt the digestion reaction. All solutions were brought up to 40 ml by adding phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), passed through 70-μm mesh filters (BD Biosciences), and centrifuged for 10 min at 1,600g and 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the remaining pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of staining solution (2% heat-inactivated horse serum in Hanks’ balanced salt solution), which was transferred to a 5-ml FACS tube. This solution was again centrifuged for 10 min at 1,600g and 4 °C. This was repeated twice to obtain a clean pellet containing mononuclear cells. This pellet was resuspended in staining solution and stained with the respective monoclonal antibodies.

Protein and mRNA expression

RNA isolation, complementary DNA synthesis and mRNA expression were performed as previously described32. All primers used in this manuscript can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Concentrations of mouse Metrnl in tissue culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems, catalogue no. DY6679) at a fivefold dilution. The mean intra-assay coefficient of variation was 2.1%. All antibodies used in this study can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Muscle injury

Skeletal muscle injury was performed by injection of BaCl2 into the TA muscle as previously described33. Then 30 μl of 1.2% BaCl2 (Sigma) was injected. A small (1-cm) incision was made in the skin overlying the distal third of the TA muscle. A 25-G, 5/8 (0.5 × 16 mm2) needle was inserted along the longitudinal axis of the muscle and the BaCl2 injected slowly as the needle was withdrawn. A second injection was performed approximately 3 mm and at a 15° angle from the first injection. After the injection the skin was bound with Vet-bond adhesive.

Histology and immunofluorescence in muscle cryosection

Immediately after dissection, the whole muscle was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 8 h, then cut at the mid-belly and placed in OCT buffer for later use; 10-μm sections were cut on the cryostat and evaluated microscopically.

BrdU labeling

Two pulses of 4 mg ml−1 of BrdU (Sigma) in 250 μl PBS were administered at 24 and 12 h before tissue harvest via intraperitoneal injection. Satellite cells were isolated as previously described34. Fixed cells were processed and stained with PE-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sorted cells were identified as DAPI positive and BrdU incorporation was defined by comparing unstained controls.

EdU labeling

Quantification of MuSC proliferation was assayed with Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594 Imaging kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of ethynyl deoxyuridine (EdU)-positive cells was performed on the automated Cellomics ArrayScan as previously described34.

Myofibre cross-sectional analysis

Myofibre cross-sectional analysis was performed as previously described32,33. In brief, four distinct digital images from haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained muscle sections (10 μm) from the mid-belly of the TA muscle at a ×20 magnification were taken and analysed for fibre cross-sectional area using National Institutes of Health (NIH) imaging software (Image J). Each fibre was traced with a handheld mouse and the number of pixels traced was calibrated to a defined area in micrometres squared. The researcher, blinded to the treatment groups, traced approximately 150 fibres per sample. All fibres in the cross-sectional images were quantified unless the sarcolemma was not intact.

Parabiosis

Parabiosis methods were performed as previously described35–38. In brief, anastomosis surgery was carried out using 3- to 4-month-old female mice, 3 weeks before TA muscle injury. Experimental groups included WT–WT, WT–Metrnl KO (WT–KO), KO–KO or KO–WT. A shared blood supply was ensured 3 weeks after surgery using flow cytometry35.

Bone marrow transplantation

Mice (aged ~12 weeks) were irradiated (900 cGy) and the tail vein injected with bone marrow isolated from age-matched donors (1 × 106 cells in 200 ml PBS). Engraftment into the bone marrow was allowed to occur for 2 months and verified using flow cytometry as previously described36.

10× Single-cell analysis

Generation of Drop-seq data

Single-cell RNA-seq was performed on single-cell isolates of young muscle 24 h after BaCl2 injury. Then 10,000 cells were used to generate cDNA. After size selection (<40-μm filter), the cells were washed to remove cell debris, counted and normalized to 1 × 106 cells ml−1. On the 10X Genomics Chromium Drop-seq platform, cells were resuspended in a master mix containing reverse transcription (RT) reagents. This suspension was partitioned with a unique gel-bead that carries immobilized oligonucleotides containing an Illumina P5 adaptor, a read 1 oligonucleotide, a cell-defining ×10 barcode, a unique molecular identifier for transcript counting and a poly(dT) primer. Oil was used to form nanolitre-scale gel beads in emulsion (GEMs) within which an individual cell was lysed, the oligos were released from the gel bead and the RT reaction started. A unique, cell-defining, ×10 barcode is shared by all cDNAs generated from the individual cell within each GEM.

After the RT reaction, the GEMs were broken and the full-length cDNAs cleaned and quantified. The cDNA was sheared to ~200 basepairs and sequencing libraries constructed by end-repair and A-tailing, adaptor ligation, SPRI bead clean-up, sample index PCR (for sample multiplexing), and Illumina P7 and read 2 primer addition. The final libraries contained P5 and P7 primers used in Illumina bridge amplification. The 125-bp paired-end sequencing was generated for 10,000 cells per single-cell expression (SCE) library on 1.5 lanes on an Illumina 2500 sequencing platform, at 50,000 reads per cell.

Analysis of SCE data

Our analysis pipeline of SCE sequence data began with 10X Genomics Cell Ranger software v.1.3 to demultiplex the raw FASTQ reads and align them to the mouse genome. We used Seurat39 to perform quality control and analysis by normalizing data on a log scale after filtering for minimum gene and cell observance frequency cut-offs40. We then filtered to identify and exclude possible multiplets (that is, more than one cell was present and sequenced in a GEM)40. To further reduce noise we removed technical artefacts using regression methods40. After completing the quality control, we calculated the principal components (PCs) using the most variably expressed genes in our dataset40.

Genes underlying the resulting PCs were examined to confirm whether they were not enriched in genes involved in cell division or other standard cellular processes. Significant PCs for downstream analyses were determined using methods implemented by Macosko et al. and carried forward to perform cell clustering and enhance visualization41. Cells were grouped into clusters using Seurat’s FindClusters function40, which uses the smart local moving algorithm42 with visualization of cells through the use of t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding43; this reduces the information captured in the selected significant PCs to two dimensions39,43. Additional downstream analyses included examining the distribution of an assumed list of genes of interest, closer examination of genes associated with cell clusters and then refining the clustering of cells to identify or further resolve the cell types39.

Macrophage migration assay

THP-1 (American Type Culture Collection) cells were grown in a complete medium containing RPMI-1640 (Sigma Aldrich), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma). THP-1 cells (1 × 106) were added to the top chamber of a 3-μm polyester transwell migration chamber and differentiated into M0 macrophages by 24 h of treatment with 10 ng ml−1 of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma). After differentiation, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate was removed by gentle washing with PBS. Cells were then differentiated into either M1 macrophages with 15 ng ml−1 of LPS (Sigma) or M2 macrophages with 25 ng ml−1 of IL-4 and 25 ng/ml−1 of IL-13 (both from R&D Systems) in complete medium. After differentiation, cells were gently washed and incubated in migration medium (Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium + 1% penicillin–streptomycin), with the bottom chamber containing no chemoattractant (negative control), 10 ng ml−1 of (low) recombinant human Metrnl (Aviscera Bioscience), 100 ng ml−1 of (high) recombinant human Metrnl or 10 nM (positive control) recombinant human CXCL-8 (R&D Systems). After a 24-h incubation at 37 °C/5% CO2, transwell inserts were removed. Non-migrated cells were gently removed from the top layer of the insert using cottonwool tips before the transwell and migrated cells were fixed for 15 min in 4% formaldehyde. After fixation, cells were allowed to dry before being stained for 10 min in 0.25% crystal violet. Cells were then rinsed in ultra-pure and sterile water (ddH2O) and allowed to dry before quantification using light microscopy. Experiments were completed in triplicate, with each well having cells counted in five different viewing areas. The results are the mean ± s.d. of total cells per well per experiment.

Human RT protocol

A cohort of subjects used in Lalia et al.44 was used to quantify Metrnl mRNA expression after a bout of unaccustomed resistance training. In brief, muscle biopsies were obtained from the right vastus lateralis before and 18 h after unaccustomed, seated, unilateral leg extensions.

Macrophage culture

Primary murine BMM cultures were established by flushing marrow from mouse tibia and femurs using a 27-G syringe filled with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Life Technologies); the marrow was then dispersed by drawing through the syringe a few times, and red cells were lysed with ammonium chloride. Adherent cells were cultured in BMM medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (v:v) fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 30% (v:v) L929 cell-conditioned medium) for 5 d. The cells were lifted using Cell Dissociation Medium (Life Technologies), replated at equal densities and cultured for an additional 2 d to yield confluent plates of cells. The macrophages were then untreated (M0) or stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of Salmonella LPS (Sigma) to stimulate a pro-inflammatory/M1 activation. After 6 or 24 h, conditioned medium from the cells was saved and subsequently used for protein determination by ELISA; the plates of cells were washed twice with cold PBS and used for RNA preparation and gene expression analysis by quantitative RT–PCR.

Satellite cell/MuSC culture

Satellite cells were isolated as described above and seeded in plates coated with collagen I (1 μg ml−1, BD Biosciences) and laminin (10 μg ml−1, BD Biosciences) in myogenic growth medium (20% heat-inactivated horse serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin and 5 ng ml−1 of β-fibroblast growth factor in F10). Then, 384-well plates were used for all EdU proliferation assays using ~2,000 cells per well.

Chemical reagents

Metrnl (R&D Biosystems) in vitro 100 ng ml−1, in vivo (2 μg per muscle), Stat3 inhibitor (Calbiochem) in vitro 50 μM and in vivo (intramuscularly) 50 μg per muscle45, IGF-1 100 nM (R&D Biosystems)46, IL-10 (R&D Biosystems) 10 ng ml−1 (ref. 5), IGF-1 receptor inhibitor AG1024 (Cayman Chemical) in vivo 30 μg 100 μl−1 (ref. 47) and Stat6 inhibitor AS1517499 (Sigma) 50 nM as shown in ref. 48.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s post hoc analysis or two-tailed, unpaired, Student’s t-test. All data are reported as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v.7 software.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All transcriptomic data generated or analysed during the present study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files). Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and in GSE145236. Source data for Fig. 6 are available online.

Extended Data

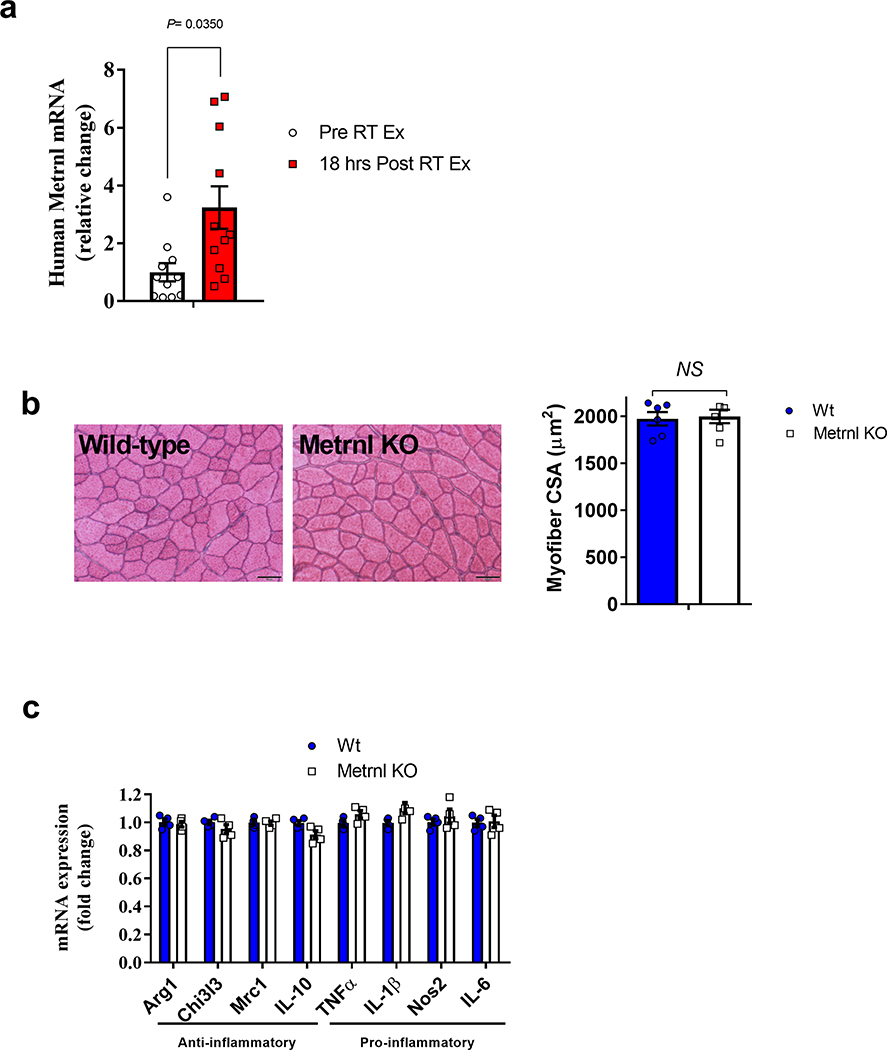

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Metrnl mRNA expression with human muscle damage and CSA analysis of uninjured Metrnl Ko muscle.

a, Human muscle Metrnl mRNA expression before and after unaccustomed resistance training (N=11/group). b, left Myofiber cross-sections from uninjured wild-type and Metrnl KO mice and right corresponding myofiber cross-sectional area (N=6/group). c, Whole muscle mRNA expression of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory macrophage makers in uninjured muscle (N=4 for both groups). Scale bar is 50μm; Two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test (a–c). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Skeletal muscle specific deletion of Metrnl and the chemotaxis ability of Metrnl.

a, Metrnl mRNA across tissues with or without tamoxifen treatment. Samples were harvested two weeks after tamoxifen IP injections (N=5/group). b, Migration assays using LPS and IL-4-treated macrophages. c, FACS analysis of migrating M1 or (d) M2 differentiated macrophages to recombinant Metrnl protein (N=3/group). Two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test (a) and ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (c, d). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Hematopoietic-derived Metrnl expression is necessary and sufficient for successful muscle regeneration.

a, Experimental design for the bone marrow transplant. Wild-type or Metrnl KO mice served as donor mice to wild-type or Metrnl KO recipient mice. Mice received BaCL2 injection five weeks after irradiation and recovered for 14 days before harvest. b, left GFP+ cells in circulating blood from a wild-type donor into a wild-type recipient 5 weeks after transplant. right GFP+ cells in circulating blood from a GFP donor into a wild-type recipient 5 weeks after transplant. N=5 biologically independent samples. c, GFP+ cells infiltrating muscle 1 day after injury in the respective transplant groups. N=5 biologically independent samples. Scale bar 100 μm. d, Metrnl mRNA expression. (N=5/group). e, Representative images of the respective transplantation groups 14 days after injury. N=5 biologically independent samples. f, Quantification of myofiber cross sectional area of the respective transplantation groups. (N=5/group). Scale bar 100 μm. ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (d, f). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Metrnl signals directly to macrophages through Stat3 and indirectly to satellite cells through IGF-1.

a, EdU incorporation in MuSCs treated with recombinant Metrnl or control 24 h in culture (N=6/group). b, untreated/M0 BMM mRNA expression of IL-10, IGF-1 and IL-6 with or without recombinant Metrnl and/or Stat inhibitors, N=3/group. c, EdU incorporation in MuSCs treated with recombinant Metrnl, IL-10 and IGF-1 for 24 h in culture. (N=6/group). d, Experimental design of BMM-conditional media treatment to MuSCs. e, EdU incorporation in media-treated MuSCs in culture for 24 h. (N=3/group). f, BrdU incorporation in satellite cells 4 days after injury with or without recombinant Metrnl or Stat3 inhibitor. (N=6/group) Two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test (a). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison (b–f). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Duke’s Cancer Center Flow Cytometry, Histology and Molecular Genomics Cores for support on this project. J.P.W. was supported by funds from the Duke Aging Center/Pepper Center (grant no. P30-AG028716), Borden Scholar Award through Duke University and NIH/NIA grant no. K01AG056664. V.B.K. and J.L.H. were also supported by NIH/NIA grant no. P30-AG028716. D.E.L is supported by the NIH training grant (no. T32HL007057). B.M.S. was supported by an NIH grant (no. R01DK119117).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-020-0184-y.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-020-0184-y.

Peer review information Primary Handling Editor: Elena Bellafante.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Heredia JE et al. Type 2 innate signals stimulate fibro/adipogenic progenitors to facilitate muscle regeneration. Cell 153, 376–388 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du H et al. Macrophage-released ADAMTS1 promotes muscle stem cell activation. Nat. Commun 8, 669 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mounier R & Chazaud B PPARgamma transcription factor controls in anti-inflammatory macrophages the expression of GDF3 that stimulates myogenic cell fusion during skeletal muscle regeneration. Med. Sci 33, 466–469 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonkin J et al. Monocyte/Macrophage-derived IGF-1 orchestrates murine skeletal muscle regeneration and modulates autocrine polarization. Mol. Ther 23, 1189–1200 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng B et al. IL-10 triggers changes in macrophage phenotype that promote muscle growth and regeneration. J. Immunol 189, 3669–3680 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burzyn D et al. A special population of regulatory T cells potentiates muscle repair. Cell 155, 1282–1295 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castiglioni A et al. FOXP3+ T cells recruited to sites of sterile skeletal muscle injury regulate the fate of satellite cells and guide effective tissue regeneration. PLoS ONE 10, e0128094 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuswanto W et al. Poor repair of skeletal muscle in aging mice reflects a defect in local, interleukin-33-dependent accumulation of regulatory T cells. Immunity 44, 355–367 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munoz-Canoves P & Serrano AL Macrophages decide between regeneration and fibrosis in muscle. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 26, 449–450 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kharraz Y et al. Macrophage plasticity and the role of inflammation in skeletal muscle repair. Mediators Inflamm 2013, 491497 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao RR et al. Meteorin-like is a hormone that regulates immune-adipose interactions to increase beige fat thermogenesis. Cell 157, 1279–1291 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ushach I et al. METEORIN-LIKE is a cytokine associated with barrier tissues and alternatively activated macrophages. Clin. Immunol 156, 119–127 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong W et al. Meteorin-like shows unique expression pattern in bone and its overexpression inhibits osteoblast differentiation. PLoS ONE 11, e0164446 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loffler D et al. METRNL decreases during adipogenesis and inhibits adipocyte differentiation leading to adipocyte hypertrophy in humans. Int. J. Obes 41, 112–119 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bae JY et al. Effects of detraining and retraining on muscle energy-sensing network and meteorin-like levels in obese mice. Lipids Health Dis 17, 97 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisconti A et al. Loss of niche-satellite cell interactions in syndecan-3 null mice alters muscle progenitor cell homeostasis improving muscle regeneration. Skelet. Muscle 6, 34 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy D et al. Comparative study of injury models for studying muscle regeneration in mice. PLoS ONE 11, e0147198 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White JP et al. Effect of carbohydrate-protein supplement timing on acute exercise-induced muscle damage. J Int. Soc. Sports Nutr 5, 5 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigamonti E et al. Macrophage plasticity in skeletal muscle repair. Biomed. Res. Int 2014, 560629 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu H et al. Acute skeletal muscle injury: CCL2 expression by both monocytes and injured muscle is required for repair. FASEB J 25, 3344–3355 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano AL et al. Interleukin-6 is an essential regulator of satellite cell-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Metab 7, 33–44 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu XL et al. Interleukin 6 induces M2 macrophage differentiation by STAT3 activation that correlates with gastric cancer progression. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 66, 1597–1608 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Z et al. IL-6/STAT3 pathway intermediates M1/M2 macrophage polarization during the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell Biochem 119, 9419–9432 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ushach I et al. Meteorin-like/meteorin-beta Is a novel immunoregulatory cytokine associated with inflammation. J. Immunol 201, 3669–3676 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemand C et al. Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary human macrophages is differentially modulated by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J. Immunol 170, 3263–3272 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu H et al. Macrophages recruited via CCR2 produce insulin-like growth factor-1 to repair acute skeletal muscle injury. FASEB J 25, 358–369 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kisielewska J, Ligeza J & Klein A The effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, tyrphostins: AG1024 and SU1498, on autocrine growth of prostate cancer cells (DU145). Folia Histochem. Cytobiol 46, 185–191 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen B et al. Tyrphostin AG 1024 modulates radiosensitivity in human breast cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 85, 2017–2021 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parrizas M et al. Specific inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity and biological function by tyrphostins. Endocrinology 138, 1427–1433 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiquee K et al. Selective chemical probe inhibitor of Stat3, identified through structure-based virtual screening, induces antitumor activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7391–7396 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bareja A et al. Human and mouse skeletal muscle stem cells: convergent and divergent mechanisms of myogenesis. PLoS ONE 9, e90398 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White JP et al. G protein-coupled receptor 56 regulates mechanical overload-induced muscle hypertrophy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15756–15761 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White JP et al. Effect of nandrolone decanoate administration on recovery from bupivacaine-induced muscle injury. J. Appl. Physiol 107, 1420–1430 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White JP et al. The AMPK/p27(Kip1) axis regulates autophagy/apoptosis decisions in aged skeletal muscle stem cells. Stem Cell Rep 11, 425–439 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baht GS et al. Exposure to a youthful circulaton rejuvenates bone repair through modulation of beta-catenin. Nat. Commun 6, 7131 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vi L et al. Macrophage cells secrete factors including LRP1 that orchestrate the rejuvenation of bone repair. Nat. Commun 9, 5191 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang R et al. Lowering circulating apolipoprotein E levels improves aged bone fracture healing. JCI Insight 4, e129144 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong C et al. A mouse model of orthopedic surgery to study postoperative cognitive dysfunction and tissue regeneration. J. Vis. Exp 132, e56701 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satija R et al. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 495–502 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seurat—Guided Clustering Tutorial. Satija Lab https://satijalab.org/seurat/v1.4/pbmc3k_tutorial.html (2017).

- 41.Macosko EZ et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subelj L & Bajec M Unfolding communities in large complex networks: combining defensive and offensive label propagation for core extraction. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys 83(3 Pt 2), 036103 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Maarten LH & Hinton G Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Machine Learn. Res 1, 1–48 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lalia AZ et al. Influence of omega-3 fatty acids on skeletal muscle protein metabolism and mitochondrial bioenergetics in older adults. Aging 9, 1096–1129 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tierney MT et al. STAT3 signaling controls satellite cell expansion and skeletal muscle repair. Nat. Med 20, 1182–1186 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fornaro M et al. Mechano-growth factor peptide, the COOH terminus of unprocessed insulin-like growth factor 1, has no apparent effect on myoblasts or primary muscle stem cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 306, E150–E156 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang HC et al. The neuroprotective effects of intramuscular insulin-like growth factor-I treatment in brain ischemic rats. PLoS ONE 8, e64015 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quail DF et al. The tumor microenvironment underlies acquired resistance to CSF-1R inhibition in gliomas. Science 352, aad3018 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All transcriptomic data generated or analysed during the present study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files). Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and in GSE145236. Source data for Fig. 6 are available online.