Abstract

Background

The novel human coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has claimed more than 600,000 lives worldwide, causing tremendous public health, social, and economic damages. Although the risk factors of COVID-19 are still under investigation, environmental factors, such as urban air pollution, may play an important role in increasing population susceptibility to COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional nationwide study using zero-inflated negative binomial models to estimate the association between long-term (2010–2016) county-level exposures to NO2, PM2.5, and O3 and county-level COVID-19 case-fatality and mortality rates in the United States. We used both single- and multi-pollutant models and controlled for spatial trends and a comprehensive set of potential confounders, including state-level test positive rate, county-level health care capacity, phase of epidemic, population mobility, population density, sociodemographics, socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, behavioral risk factors, and meteorology.

Results

From January 22, 2020, to July 17, 2020, 3,659,828 COVID-19 cases and 138,552 deaths were reported in 3,076 US counties, with an overall observed case-fatality rate of 3.8%. County-level average NO2 concentrations were positively associated with both COVID-19 case-fatality rate and mortality rate in single-, bi-, and tri-pollutant models. When adjusted for co-pollutants, per interquartile-range (IQR) increase in NO2 (4.6 ppb), COVID-19 case-fatality rate and mortality rate were associated with an increase of 11.3% (95% CI 4.9%–18.2%) and 16.2% (95% CI 8.7%–24.0%), respectively. We did not observe significant associations between COVID-19 case-fatality rate and long-term exposure to PM2.5 or O3, although per IQR increase in PM2.5 (2.6 μg/m3) was marginally associated, with a 14.9% (95% CI 0.0%–31.9%) increase in COVID-19 mortality rate when adjusted for co-pollutants.

Discussion

Long-term exposure to NO2, which largely arises from urban combustion sources such as traffic, may enhance susceptibility to severe COVID-19 outcomes, independent of long-term PM2.5 and O3 exposure. The results support targeted public health actions to protect residents from COVID-19 in heavily polluted regions with historically high NO2 levels. Continuation of current efforts to lower traffic emissions and ambient air pollution may be an important component of reducing population-level risk of COVID-19 case fatality and mortality.

Keywords: air pollution, nitrogen dioxide, COVID-19, case-fatality rate, mortality

Graphical Abstract

Public Summary

-

•

One of the first US studies on air pollution exposures and COVID-19 death outcomes

-

•

Urban air pollutants, especially NO2, may enhance population susceptibility to death fromCOVID-19

-

•

Reduction in air pollution would have avoided over 14,000 COVID-19 deaths in the US as of July 17, 2020

-

•

Public health actions needed to protect populations from COVID-19 in areas with historically high NO2 exposure

-

•

Expansion of efforts to lower air pollution may reduce population-level risk of COVID-19

Introduction

The novel human coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus 2.1 First identified in 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province, China, the COVID-19 pandemic has since rapidly spread throughout the world. As of July 17, 2020, there have been 3,659,828 cases and 138,552 deaths confirmed in the United States.2, 3, 4 Despite substantial public health efforts, the observed COVID-19 case-fatality rate (i.e., the ratio of the number of COVID-19 deaths over the number of cases) in the United States is estimated to be 3.8%.2, 3, 4 Although knowledge concerning the etiology of COVID-19-related disease has grown since the outbreak was first identified, there is still considerable uncertainty concerning its pathogenesis, as well as factors contributing to heterogeneity in disease severity around the globe.

Environmental factors,5, 6, 7, 8 such as urban air pollution, may play an important role in increasing susceptibility to severe outcomes of COVID-19. The impact of ambient air pollution on excess morbidity and mortality has been well established over several decades.9, 10, 11 In particular, major ubiquitous ambient air pollutants, including fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3), may have both a direct and an indirect systemic impact on the human body by enhancing oxidative stress, inflammation, and respiratory infection risk, eventually leading to respiratory, cardiovascular, and immune system dysfunction and deterioration.12, 13, 14, 15, 16

Whereas the epidemiologic evidence is limited, previous findings on the outbreak of SARS, the most closely related human coronavirus disease to COVID-19, revealed a crude positive correlation between air pollution and the SARS case-fatality rate in the Chinese population without adjustment for confounders.17 An analysis of 213 cities in China recently demonstrated that temporal increases in COVID-19 cases were associated with short-term variations in ambient air pollution.18 Hence, it is plausible that prolonged exposure to air pollution may have a detrimental effect on the prognosis of patients affected by COVID-19.19 As is usual in the early literature on emerging hazards, questions remain concerning the generalizability and reproducibility of these findings, due to the lack of control for the epidemic stage of disease, population mobility, residual spatial correlation, and potential confounding by co-pollutants.

To address these analytical gaps and contribute toward a more complete understanding of the impact of long-term exposure to ambient air pollution on COVID-19-related health consequences, we conducted a nationwide study in the United States (3,122 counties) examining associations between multiple key ambient air pollutants, NO2, PM2.5, and O3, and COVID-19 case-fatality and mortality rates in both single- and multi-pollutant models, with comprehensive covariate adjustment. We hypothesized that residents living in counties with higher long-term ambient air pollution levels may be more susceptible to COVID-19 severe outcomes, thus resulting in higher COVID-19 case-fatality rates and mortality rates.

Results

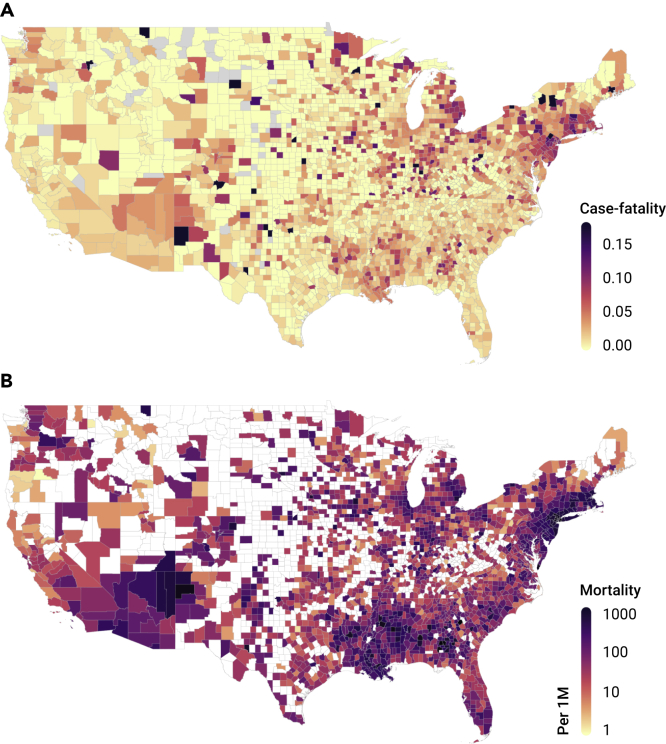

A total of 3,122 US counties were considered in the current analysis, with confirmed cases reported in 3,076 (98.5%) and deaths in 2,088 (66.9%). By July 17, 2020, 3,659,828 COVID-19 cases and 138,552 deaths were reported nationwide (Table 1). Among the counties with at least one reported COVID-19 case, the average county-level case-fatality rate was 2.4 ± 3.2% (mean ± standard deviation), and the average mortality rate was 298.0 ± 412.8 per 1 million people. Spatial variations were observed on COVID-19 case-fatality and mortality rates, where Connecticut had the highest case-fatality rate of 9.2% and New Jersey had the highest mortality rate of 1,767.5 deaths per 1 million people. The lowest case-fatality rate and mortality rate were observed in Utah (0.7%) and Hawaii (16.2 deaths per million people), respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on County-Level COVID-19 Fatality Rate and Long-Term Air Pollution Level in 3,122 US Counties

| State | Counties with Cases (n) | Total Cases (n) | Total Deaths (n) | COVID-19 Fatality Rate (%) | Mean NO2 Level (ppb) | Mean PM2.5 Level (μg/m3) | Mean Ozone Level (ppb) | ICU Beds (n/1,000 people) | Hospital Beds (n/1,000 people) | Medical Doctors (n/1,000 people) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3,076 | 3,659,828 | 138,552 | 2.4 ± 3.2 | 11.1 ± 4.4 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 42.7 ± 3.6 | 0.13 ± 0.55 | 3.0 ± 4.9 | 1.2 ± 1.6 |

| Alabama | 67 | 65,234 | 1,286 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 8.8 ± 2.1 | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 41.0 ± 1.5 | 0.18 ± 0.18 | 2.8 ± 2.7 | 1.0 ± 1.0 |

| Alaska | 19 | 1,795 | 17 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 11.8 ± 1.8 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 51.7 ± 2.9 | 0.06 ± 0.10 | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 1.3 ± 1.2 |

| Arizona | 15 | 141,265 | 2,730 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 15.5 ± 5.3 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 51.3 ± 1.7 | 0.14 ± 0.12 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.9 |

| Arkansas | 75 | 31,410 | 357 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 9.7 ± 2.7 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 42.3 ± 1.2 | 0.12 ± 0.18 | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 0.9 ± 1.0 |

| California | 57 | 379,093 | 7,702 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 12.5 ± 5.6 | 6.6 ± 2.7 | 46.2 ± 6.9 | 0.14 ± 0.09 | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 1.4 |

| Colorado | 63 | 39,770 | 1,752 | 2.7 ± 3.5 | 14.7 ± 9.4 | 4.2 ± 1.7 | 50.6 ± 1.5 | 0.52 ± 3.48 | 2.8 ± 5.3 | 1.4 ± 1.1 |

| Connecticut | 8 | 47,665 | 4,396 | 8.5 ± 3.5 | 17.2 ± 4.9 | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 42.3 ± 0.7 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.6 |

| Delaware | 3 | 13,287 | 523 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 15.7 ± 5.6 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 45.1 ± 0.7 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 0.9 |

| District of Columbia | 1 | 11,261 | 578 | 5.1 | 25.1 | 9.2 | 45.3 | 0.44 | 6.2 | 7.8 |

| Florida | 67 | 337,168 | 4,895 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 35.8 ± 2.5 | 0.17 ± 0.16 | 2.3 ± 2.9 | 1.5 ± 1.4 |

| Georgia | 159 | 126,713 | 3,099 | 2.8 ± 2.6 | 10.1 ± 3.3 | 9.4 ± 1.0 | 41.5 ± 2.1 | 0.13 ± 0.22 | 2.6 ± 4.1 | 1.0 ± 1.1 |

| Hawaii | 4 | 1,329 | 23 | 1.5 ± 2.1 | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 30.7 ± 0.8 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| Idaho | 41 | 14,302 | 119 | 0.8 ± 2.6 | 10.8 ± 3.7 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 45.8 ± 2.3 | 0.06 ± 0.11 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 0.9 ± 0.8 |

| Illinois | 102 | 160,576 | 7,290 | 2.7 ± 3.2 | 14.3 ± 4.7 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 43.1 ± 1.3 | 0.12 ± 0.16 | 2.1 ± 2.1 | 1.1 ± 1.1 |

| Indiana | 92 | 55,654 | 2,627 | 4.3 ± 3.6 | 14.5 ± 3.8 | 10.3 ± 0.6 | 42.5 ± 1.4 | 0.15 ± 0.19 | 1.9 ± 2.2 | 1.1 ± 1.2 |

| Iowa | 99 | 37,870 | 787 | 2.2 ± 2.9 | 11.4 ± 2.2 | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 41.0 ± 0.5 | 0.08 ± 0.15 | 2.9 ± 2.3 | 0.8 ± 1.4 |

| Kansas | 102 | 22,104 | 305 | 1.1 ± 3.7 | 11.6 ± 3.1 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 46.3 ± 1.9 | 0.09 ± 0.19 | 8.2 ± 11.2 | 0.9 ± 0.8 |

| Kentucky | 120 | 22,178 | 667 | 2.3 ± 3.1 | 9.9 ± 2.7 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 43.1 ± 1.3 | 0.15 ± 0.25 | 2.3 ± 2.7 | 1.0 ± 1.0 |

| Louisiana | 64 | 88,586 | 3,399 | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 11.2 ± 3.6 | 8.9 ± 0.6 | 40.8 ± 1.7 | 0.16 ± 0.19 | 3.4 ± 5.2 | 1.2 ± 1.5 |

| Maine | 16 | 3,661 | 117 | 3.5 ± 5.7 | 10.4 ± 2.3 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 35.2 ± 2.1 | 0.15 ± 0.13 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 1.2 |

| Maryland | 24 | 78,131 | 3,361 | 4.6 ± 2.4 | 16.2 ± 5.1 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 45.4 ± 0.6 | 0.15 ± 0.19 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 2.3 |

| Massachusetts | 14 | 112,919 | 8,413 | 7.8 ± 3.5 | 16.0 ± 4.6 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 40.6 ± 1.1 | 0.15 ± 0.14 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 3.1 |

| Michigan | 83 | 76,939 | 6,291 | 4.3 ± 3.7 | 11.0 ± 4.8 | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 40.8 ± 1.3 | 0.15 ± 0.24 | 2.3 ± 2.2 | 1.3 ± 1.6 |

| Minnesota | 86 | 45,381 | 1,538 | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 11.1 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 39.0 ± 1.6 | 0.10 ± 0.20 | 3.7 ± 4.9 | 1.4 ± 2.6 |

| Mississippi | 82 | 41,846 | 1,346 | 3.6 ± 2.4 | 8.7 ± 2.2 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 40.9 ± 1.8 | 0.14 ± 0.22 | 5.5 ± 14.2 | 1.0 ± 1.2 |

| Missouri | 115 | 32,246 | 1,130 | 1.6 ± 2.6 | 9.9 ± 3.7 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 43.2 ± 1.0 | 0.10 ± 0.18 | 2.0 ± 2.4 | 0.8 ± 1.4 |

| Montana | 45 | 2,471 | 37 | 1.0 ± 3.1 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 43.2 ± 2.1 | 0.07 ± 0.12 | 6.5 ± 7.5 | 1.2 ± 0.9 |

| Nebraska | 83 | 22,366 | 299 | 1.2 ± 2.8 | 10.4 ± 3.0 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 44.2 ± 2.8 | 0.05 ± 0.16 | 4.5 ± 5.9 | 0.9 ± 0.8 |

| Nevada | 16 | 34,477 | 646 | 1.7 ± 2.6 | 13.3 ± 5.6 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 50.4 ± 1.6 | 0.10 ± 0.20 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 0.9 ± 0.9 |

| New Hampshire | 10 | 6,188 | 396 | 3.2 ± 2.5 | 11.9 ± 0.8 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 38.6 ± 1.1 | 0.19 ± 0.17 | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 3.2 ± 3.8 |

| New Jersey | 21 | 176,148 | 15,699 | 9.4 ± 2.5 | 22.9 ± 6.2 | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 43.2 ± 1.1 | 0.19 ± 0.09 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.4 |

| New Mexico | 32 | 15,781 | 569 | 2.9 ± 5.0 | 11.4 ± 3.6 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 50.0 ± 1.3 | 0.12 ± 0.12 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.2 ± 1.0 |

| New York | 62 | 406,305 | 32,031 | 5.3 ± 4.2 | 15.1 ± 7.8 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 41.2 ± 1.3 | 0.15 ± 0.11 | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 2.0 |

| North Carolina | 100 | 97,958 | 1,629 | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 2.7 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 42.3 ± 1.3 | 0.15 ± 0.16 | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.9 |

| North Dakota | 52 | 5,019 | 90 | 0.7 ± 2.2 | 7.1 ± 1.9 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 40.4 ± 1.0 | 0.05 ± 0.15 | 5.9 ± 8.4 | 0.7 ± 1.0 |

| Ohio | 88 | 73,821 | 3,132 | 4.0 ± 3.8 | 15.4 ± 3.7 | 10.2 ± 0.6 | 43.3 ± 1.1 | 0.17 ± 0.15 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 1.2 |

| Oklahoma | 77 | 25,056 | 451 | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 10.5 ± 2.3 | 8.2 ± 1.0 | 46.0 ± 1.9 | 0.09 ± 0.15 | 3.0 ± 3.2 | 0.6 ± 0.6 |

| Oregon | 35 | 14,149 | 257 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 9.8 ± 2.5 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 39.8 ± 3.7 | 0.11 ± 0.13 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 1.2 |

| Pennsylvania | 67 | 100,241 | 7,007 | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 13.9 ± 4.4 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 43.0 ± 0.9 | 0.21 ± 0.29 | 3.3 ± 5.1 | 2.2 ± 4.6 |

| Rhode Island | 5 | 15,503 | 979 | 6.6 ± 3.8 | 15.5 ± 3.5 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 42.2 ± 0.2 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 1.8 |

| South Carolina | 46 | 67,396 | 1,117 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 10.1 ± 2.2 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 39.7 ± 2.0 | 0.17 ± 0.15 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 1.3 |

| South Dakota | 63 | 7,736 | 115 | 1.1 ± 3.2 | 7.6 ± 2.6 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 42.9 ± 1.2 | 0.06 ± 0.14 | 5.0 ± 6.2 | 1.0 ± 1.2 |

| Tennessee | 95 | 73,186 | 827 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 8.7 ± 3.0 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 43.0 ± 1.1 | 0.13 ± 0.19 | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 1.0 ± 1.2 |

| Texas | 250 | 322,724 | 3,865 | 1.6 ± 3.9 | 10.0 ± 2.8 | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 43.6 ± 4.6 | 0.12 ± 0.51 | 2.2 ± 4.0 | 0.8 ± 0.8 |

| Utah | 27 | 33,247 | 232 | 0.5 ± 1.2 | 12.5 ± 6.6 | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 50.3 ± 1.0 | 0.07 ± 0.09 | 2.0 ± 1.8 | 1.1 ± 1.1 |

| Vermont | 14 | 1,332 | 56 | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 11.1 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 38.8 ± 0.8 | 0.10 ± 0.12 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 2.6 ± 1.8 |

| Virginia | 122 | 75,822 | 1,959 | 2.3 ± 2.4 | 12.1 ± 4.0 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 42.9 ± 1.1 | 0.15 ± 0.28 | 2.9 ± 5.8 | 1.9 ± 3.0 |

| Washington | 39 | 45,943 | 1,444 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 10.6 ± 2.9 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 38.6 ± 4.2 | 0.09 ± 0.11 | 2.5 ± 3.6 | 1.4 ± 1.0 |

| West Virginia | 54 | 4,983 | 100 | 1.7 ± 2.7 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.3 | 42.3 ± 1.6 | 0.18 ± 0.28 | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 1.2 ± 1.8 |

| Wisconsin | 72 | 41,485 | 843 | 2.3 ± 4.0 | 11.1 ± 3.9 | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 39.5 ± 1.6 | 0.12 ± 0.15 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.3 |

| Wyoming | 23 | 2,108 | 24 | 1.1 ± 2.6 | 7.0 ± 2.9 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 46.6 ± 2.3 | 0.12 ± 0.14 | 4.7 ± 3.3 | 1.4 ± 0.9 |

Descriptive statistics was conducted on 3,122 US counties using data reported as of July 17, 2020. COVID-19 case fatality rate was calculated by the number of deaths divided by the number of cases, reported as of July 17, 2020.

Figure 1.

County-Level COVID-19 Case-Fatality and Mortality Rates

County-level COVID-19 case-fatality rate (A) and mortality rate per 1 million people (B) as of July 17, 2020.

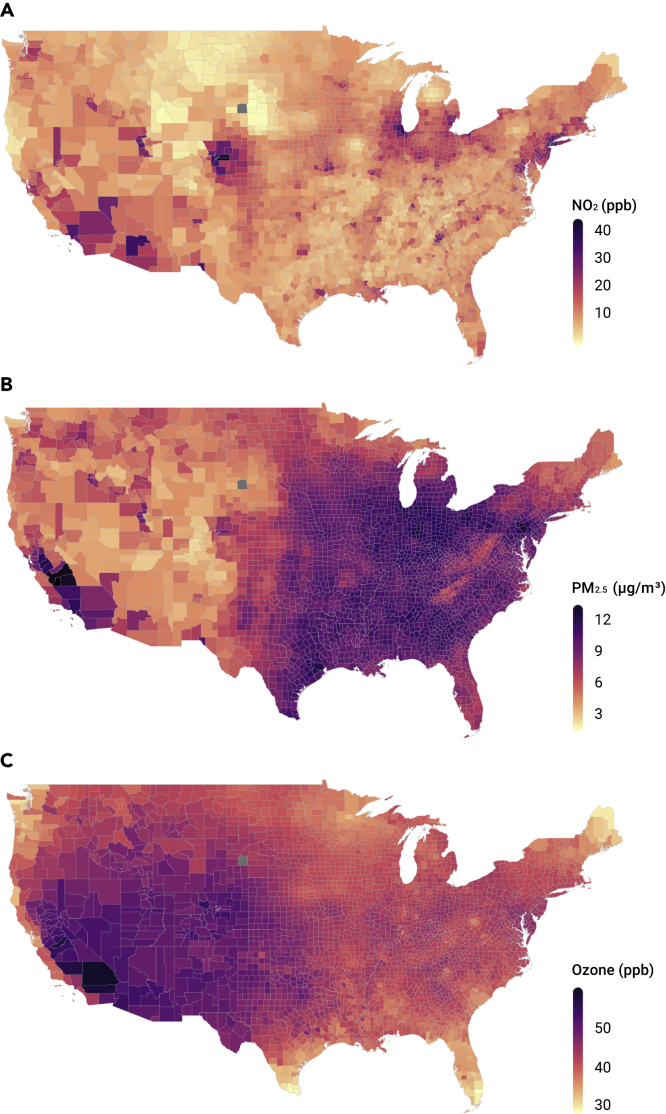

Long-term (2010–2016) average concentrations across the contiguous United States ranged from 5.8 to 19.3 ppb (5th and 95th percentiles, respectively) for NO2, 3.8 to 10.4 μg/m3 for PM2.5, and 37.2 to 49.7 ppb for warm-season average ozone concentrations, respectively (Figure 2). The highest NO2 levels were in New York, New Jersey, and Colorado, and the lowest in Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota. California and Pennsylvania had the highest PM2.5 concentrations, and the highest O3 levels were in Colorado, Utah, and California.

Figure 2.

County-Level Annual Average Concentrations of Nitrogen Dioxide, Fine Particulate Matter, and Ozone

County-level annual average concentrations of NO2 (A), PM2.5 (B), and ozone (C) for the period 2010–2016.

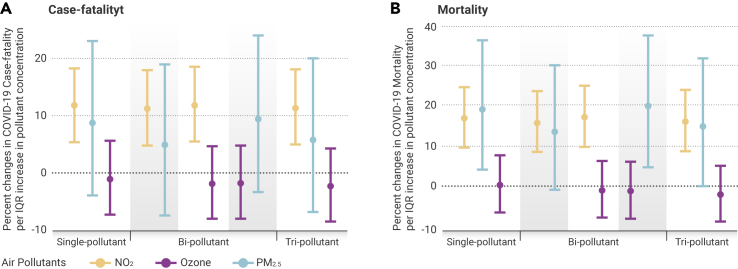

We observed significant positive associations between NO2 levels and both county-level COVID-19 case-fatality rate and county-level COVID-19 mortality rate (Table 2 and Figure 3), when controlling for covariates. In tri-pollutant models, COVID-19 case-fatality and mortality rates were associated with increases of 11.3% (95% CI 4.9%–18.2%) and 16.2% (95% CI 8.7%–24.0%), respectively, per IQR (∼4.6 ppb) increase in NO2 (Table 2). These results imply that one IQR reduction in long-term exposure to NO2 level would have avoided 14,672 deaths (95% CI 6,721 to 22,143) among those who tested positive for the virus and 44.7 deaths (95% CI 20.5 to 67.5) per million people in the general population, as of July 17, 2020. The strength and magnitude of the associations between NO2 and both COVID-19 case-fatality rate and COVID-19 mortality rate persisted across single-, bi-, and tri-pollutant models (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Model Effect Estimates on Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Mixed Models to Examine the Associations between Long-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate or Mortality

| COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate |

COVID-19 Mortality Rate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollutant | Main Effect Estimatea | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value | Main Effect Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | p Value |

| Single-Pollutant Model—Non-zero Components | ||||||

| NO2 | 1.12 | 1.05 to 1.18 | 0.0003 | 1.17 | 1.10 to 1.25 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 1.09 | 0.96 to 1.23 | 0.19 | 1.19 | 1.04 to 1.37 | 0.012 |

| O3 | 0.99 | 0.93 to 1.06 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 0.93 to 1.08 | 0.95 |

| Tri-pollutant Model—Non-zero Components | ||||||

| NO2 | 1.11 | 1.05 to 1.18 | 0.0005 | 1.16 | 1.09 to 1.24 | <0.0001 |

| PM2.5 | 1.06 | 0.93 to 1.20 | 0.39 | 1.15 | 1.00 to 1.32 | 0.051 |

| O3 | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.04 | 0.48 | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.05 | 0.55 |

| Single-Pollutant Model—Zero Components | ||||||

| NO2 | 0.96 | 0.82 to 1.12 | 0.61 | 1.02 | 0.88 to 1.18 | 0.82 |

| PM2.5 | 0.99 | 0.75 to 1.31 | 0.96 | 0.75 | 0.58 to 0.98 | 0.036 |

| O3 | 0.86 | 0.73 to 1.01 | 0.068 | 0.71 | 0.61 to 0.83 | <0.0001 |

| Tri-pollutant Model—Zero Components | ||||||

| NO2 | 0.95 | 0.80 to 1.12 | 0.53 | 1.04 | 0.89 to 1.21 | 0.67 |

| PM2.5 | 1.14 | 0.85 to 1.53 | 0.38 | 0.92 | 0.71 to 1.20 | 0.55 |

| O3 | 0.83 | 0.70 to 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.63 to 0.87 | 0.0001 |

The zero-inflated negative binomial mixed model comprises a negative binomial log-linear count model and a logit model for predicting excess zeros. The former was used to describe the associations between air pollutants and COVID-19 case-fatality rate among counties with at least one reported COVID-19 case. The latter can account for excess zeros in counties that had not observed a COVID-19 death as of July 17, 2020.

Effect estimate based on per interquartile range (IQR) increase in air pollutants. IQRs of NO2, PM2.5, and O3 averaged between 2010 and 2016 were 4.6 ppb, 2.6 μg/m3, and 3.3 ppb, respectively.

Figure 3.

Percentage Change in County-Level COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate and Mortality Rate

Percentage change in county-level COVID-19 case-fatality rate (A) and mortality rate (B) per interquartile range (IQR) increase in long-term air pollutant concentrations. Effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using county-level concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2, orange), ozone (purple), and fine particulate matter (PM2.5, blue) averaged between 2010 and 2016, controlling for covariates including county-level number of cases per 1,000 people, social deprivation index, population density, percentage of residents over 60 years of age, percentage of males, race and ethnicity, body mass index, smoking rate, number of regular hospital beds per 1,000 people, number of intensive unit beds per 1,000 people, number of medical doctors per 1,000 people, average mobility index assessed between March and July 17, 2020, average temperature and humidity between January 22 and July 17, 2020, state-level COVID-19 test positive rate as of July 17, 2020, and spatial smoother with 5 degrees of freedom for both latitude and longitude. IQRs of NO2, PM2.5, and O3 averaged between 2010 and 2016 were 4.6 ppb, 2.6 μg/m3, and 3.3 ppb, respectively.

In contrast, PM2.5 was not associated with COVID-19 case-fatality rate (95% CI −6.9% to 20.0%) but was marginally associated with higher COVID-19 mortality rate in tri-pollutant models, where one IQR (2.6 μg/m3) increase in PM2.5 was associated with a 14.9% (95% CI 0.0%–31.9%) increase in COVID-19 mortality rate (Table 2). Null associations were found between long-term exposure to O3 and both COVID-19 case-fatality and COVID-19 mortality rates (95% CI −8.6% to 4.2% and −8.9% to 5.1%, respectively). Similar trends persisted across single-, bi-, and tri-pollutant models (Figure 3). The Moran's I and p values (Table S1) from these models suggested that most spatial correlations in the data have been accounted for.

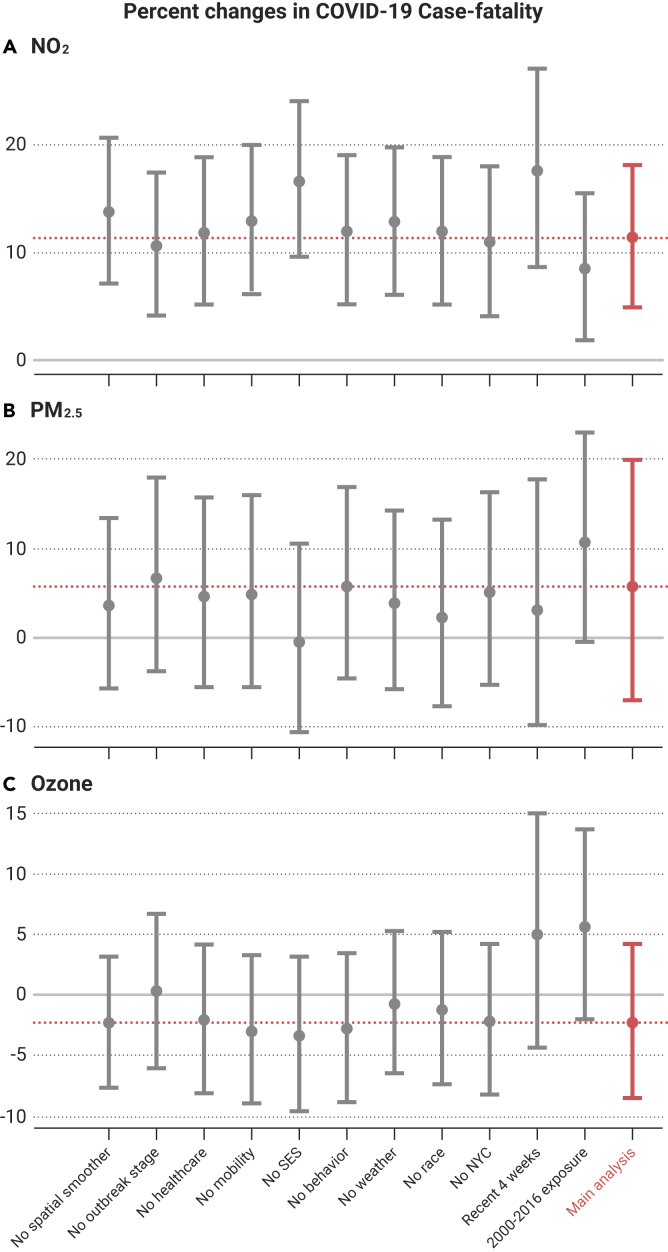

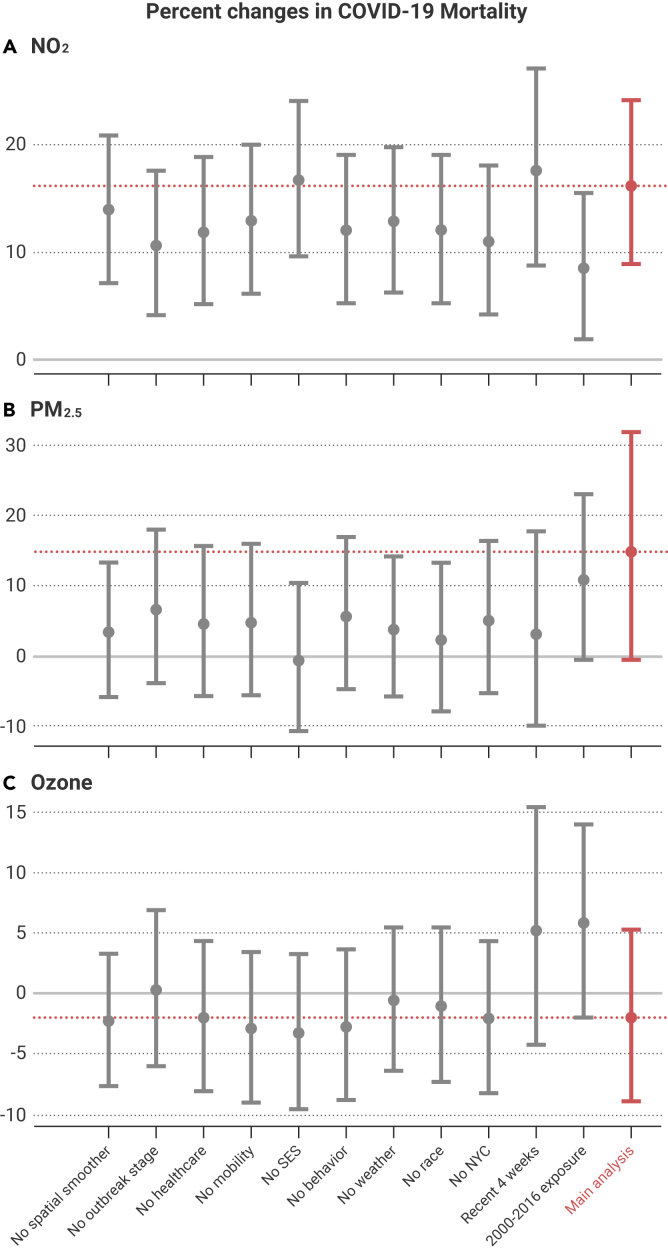

Results remained robust and consistent across 66 sets of sensitivity analyses (Figures 4 and 5). When we restricted the analyses to data reported between June 20 and July 17, when COVID-19 tests were more readily available, significant associations remained between NO2 and COVID-19 case-fatality and mortality rates, and no consistent associations were found with PM2.5 or O3. We also observed similar trends pointing to associations with NO2 when excluding New York City. In addition, we found similar results when omitting the 679 counties (21.7%) with missing behavioral risk data.

Figure 4.

Percentage Change in COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate in the Sensitivity Analysis

Percentage change in COVID-19 case-fatality rate per interquartile range increase in NO2 (A), PM2.5 (B), and ozone (C) concentrations in the sensitivity analysis. The red line denotes the estimated effects in the main analysis. All results were derived from the tri-pollutant models. Recent 4 weeks refers to June 20 to July 17.

Figure 5.

Percentage Change in COVID-19 Mortality Rate in the Sensitivity Analysis

Percentage change in COVID-19 mortality rate per interquartile range increase in NO2 (A), PM2.5 (B), and ozone (C) concentrations in the sensitivity analysis. The red line denotes the estimated effects in the main analysis. All results were derived from the tri-pollutant models. Recent 4 weeks refers to June 20 to July 17.

Discussion

In this nationwide study, we used county-level information on long-term air pollution and corresponding health, behavioral, and demographic data to examine associations between long-term exposure to key ambient air pollutants and COVID-19 death outcomes in both single- and multi-pollutant models. We observed significant positive associations between NO2 levels and both county-level COVID-19 case-fatality rate and county-level COVID-19 mortality rate, a marginal association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and COVID-19 mortality rate, and null associations for long-term O3 exposure in multi-pollutant models. These results provide additional initial support for the interpretation that long-term exposure to air pollution, especially NO2—a component of urban air pollution related to traffic—may enhance susceptibility to severe COVID-19 outcomes. These findings may help identify susceptible and high-risk populations, especially those living in areas with historically high NO2 pollution, including the metropolitan areas in New York, New Jersey, California, and Arizona. Given the rapid escalation of COVID-19 spread and associated mortality in the United States, swift and coordinated public health actions, including strengthened enforcement on social distancing and expanding health care capacity, are needed to protect these and other vulnerable populations. Although average NO2 concentrations have decreased gradually over the past decades, it is critical to continue enforcing air pollution regulations to protect public health, given that health effects occur even at very low concentrations.20

Currently, there are few existing studies investigating the link between air pollution and COVID-19, the majority of which are correlation-only studies without adjustment for confounders. Among these sparse studies, our findings are consistent with a recent European study that reported that 78% of the COVID-19 deaths across 66 administrative regions in Italy, Spain, France, and Germany occurred in the five most polluted regions with the highest NO2 levels.21 Another recent paper reported correlations between high levels of air pollution and high death rates seen in northern Italy.22 However, major questions remain concerning the robustness and generalizability of these early findings, due to the lack of control for population mobility, multi-pollutant exposures, and, most importantly, potential residual spatial autocorrelation.

The current analysis addresses several of these limitations. We examined two major COVID-19 death outcomes, the county-level case-fatality rate and the mortality rate. The case-fatality rate can indicate biological susceptibility to severe COVID-19 outcomes (i.e., death), while the mortality rate can offer information on the severity of COVID-19 deaths in the general population. Our study also included an assessment of three major air pollutants using high-spatial-resolution maps, used recent county-level data, considered both single- and multi-pollutant models, and controlled for county-level mobility. Given that the stage of the COVID-19 epidemic might depend on the size and urbanicity of the county, we included the times of the first and the 100th case for each county in the models as covariates to minimize the possibility that the observed associations were confounded by epidemic timing due to unmeasured location and population-level characteristics. Due to the cross-sectional design, we controlled for potential spatial trends by including flexible spatial trends in the main analysis, and evaluated residual autocorrelation using Moran's I statistic. Our analyses indicated that the presence of spatial confounding was substantial, necessitating the use of spatial smoothing (Figures 4 and 5). We performed both stratified analyses and effect modification analyses by adding interaction terms in the model to examine the effects of potential confounders, including SES. None of these potential modifying effects were significant and none were included in the final analytical modeling approach. Finally, we conducted a total of 66 sets of sensitivity analyses and observed robust and consistent results.

Although social distancing measures around the United States have reduced vehicle traffic and urban air pollution in the short term, it is plausible that long-term exposure to urban air pollutants like NO2 may have sustained direct and indirect effects within the human body, making people more biologically susceptible to severe COVID-19 outcomes. NO2 can be emitted directly from combustion sources or produced from the titration of nitric oxide (NO) with O3. NO2 and NO have relatively short atmospheric lifetimes, thus having larger spatial heterogeneity compared with more regionally distributed pollutants such as PM2.5 and O3. As a result, the spatial distribution of NO2 represents the intensity of anthropogenic activity, especially emissions from traffic and power plants. As a reactive free radical, NO2 plays a key role in photochemical reactions that produce other secondary pollutants, including ozone and secondary particulate matter. In our analysis of three major air pollutants, however, NO2 showed strong and independent effects on COVID-19 case-fatality rate and mortality, meaning that the effects of NO2 may not be mediated by PM2.5 and O3. Even so, we cannot rule out the possibility that NO2 is serving as a proxy for other traffic-related air pollutants, such as soot, trace metals, or ultrafine particles. Long-term exposures to NO2 have been associated with acute and chronic respiratory diseases, including increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness, decreased lung function, and increased risk of respiratory infection and mortality.23, 24, 25 In addition, as a highly reactive exogeneous oxidant, NO2 can induce inflammation and enhance oxidative stress, generating reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which may eventually deteriorate the cardiovascular and immune systems.13,26 The impact of long-term exposure to PM2.5 on excess morbidity and mortality has also been well established.9, 10, 11,20 An early unpublished report that explored the impacts of air pollution on mortality found that 1 μg/m3 PM2.5 was associated with 8% increase in COVID-19 mortality rates in the United States.27 The study was conducted in a single-pollutant model and did not investigate COVID-19 case-fatality rates. Similarly, we found marginally significant associations between COVID-19 mortality rates and PM2.5, when controlling for co-pollutants and covariates, although the magnitude and strength of this association observed in the current analysis were weaker, mainly due to our control of the spatial trends, co-pollutants, and residual autocorrelation, which may have confounded the previous study findings. In addition, PM2.5 was not associated with COVID-19 case-fatality rate across all single- and multi-pollutant models, indicating that it may have less impact on biological susceptibility to severe COVID-19 outcomes compared with NO2.

We acknowledge that our study is limited in several key areas. First, the cross-sectional study design reduced our ability to exploit temporal variation and trends in COVID-19 deaths, an important determinant in establishing causal inference. However, an ecological (area-level) analysis may offer valuable information as part of initial public health investigations for hypothesis generation, particularly where individual-level studies may not be possible for some time until fine-scale exposure data become available. Toward this end, future time-series analyses of air pollution and COVID-19 case-fatality rates and corresponding mortality rates will be important. Second, there may be complex case ascertainment biases in the county-level COVID-19 data, particularly during the early stages of the outbreak due to lack of reliable testing, which may greatly underestimate the actual COVID-19 case number. However, with the case data quality gradually improved over the past 3 months due to enhanced testing capacity, we repeated the analysis using the COVID data reported at several time points (by April 1, by May 1, by June 2, and by July 17), and the results still hold. Third, actual death counts are likely biased, with highly dynamic reported fatality rates, increasing from 1.8% to 5.8% and then decreasing to 3.8% in the past 3 months.2, 3, 4 However, results using data from only the most recent 4 weeks were largely unchanged, suggesting that differential errors in reporting or testing for COVID-19 may not have exerted much influence on these findings. In this analysis, the air pollution levels were modeled between 2010 and 2016, which may introduce bias into the exposure assessment. Specifically, given that the average air pollution levels in United States have gradually decreased over the years, when using the exposure data between 2010 and 2016 rather than more recent data, we may have overestimated the exposure levels, leading to underestimated health effects. Although more recent exposure data were not available, county-specific mean concentrations of air pollutants across years are highly correlated.28 Moreover, we have conducted a sensitivity analysis by using the exposure data between 2000 and 2016, and the results remained robust and consistent. In addition, although we controlled for many potential confounders such as population density, we cannot rule out the possibility that NO2 might be a proxy of urbanicity. The exclusion of climate meteorological variables and SES—two factors that have received substantial attention regarding the outbreak—did not alter the main results. Due to the lack of county-level data, we could not account for the percentage of hospitalized cases or ICU use among cases or deaths, the number of available ventilators, and the underlying health conditions of cases likely to increase death risk (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Also, as a classical traffic-related air pollutant, NO2 can exhibit spatial variation within a county,28 which may not be captured in our analysis. Identification of NO2 pollution hotspots within a county may be warranted.

Conclusions

We found statistically significant, positive associations between long-term exposure to NO2 and COVID-19 case-fatality rate and mortality rate, independent of PM2.5 and O3. Prolonged exposure to this urban traffic-related air pollutant may be an important risk factor of severe COVID-19 outcomes. The results support targeted public health actions to protect residents from COVID-19 in heavily polluted regions with historically high NO2 levels. Moreover, continuation of current efforts to lower traffic emissions and ambient air pollution levels may be an important component of reducing population-level risk of COVID-19 case fatality and mortality.

Material and Methods

We obtained the number of daily county-level COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths that occurred from January 22, 2020, the day of the first confirmed case in the United States, through July 17, 2020, in the United States from three databases: the New York Times,2 USAFacts,3 and 1Point3Acres.com.4 Briefly, data on county-level COVID-19 cases and deaths were confirmed by referencing state and local health agencies directly. COVID-19 confirmed case counts include both laboratory-confirmed cases and presumptive positive cases (i.e., cases diagnosed by doctors based on signs and symptoms without a test), which is in line with how the US Centers for Disease Control report data. In these databases, cases were assigned to where the person was diagnosed as that information became available. If a state reported both location of death and location of residency, the case was attributed to the location of residency.3 COVID-19 death counts include both confirmed (i.e., by meeting confirmatory laboratory evidence for COVID-19) and probable deaths (i.e., meeting clinical criteria AND epidemiologic evidence with no confirmatory laboratory testing performed for COVID-19, meeting presumptive laboratory evidence AND either clinical criteria OR epidemiologic evidence, meeting vital records criteria with no confirmatory laboratory testing performed for COVID-19). After data acquisition from these sources, we compared the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in each US county (identified by the Federal Information Processing Standards, FIPS code) across all databases for accuracy and consistency. In case of discrepancy, county-level case and death number were corrected by manually checking the data reported from the corresponding state and local health department websites.

In this analysis, the main COVID-19 death outcomes included two county-level measures, the COVID-19 case-fatality rate and the COVID-19 mortality rate. The COVID-19 case-fatality rate was calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the number of people diagnosed in each US county with at least one confirmed case, which can imply the biological susceptibility to severe COVID-19 outcome (i.e., death). The COVID-19 mortality rate was the number of COVID-19 deaths per million population, and can reflect the severity of the COVID-19 outcomes in the general population.

Three major ambient air pollutants were included in the analysis, including NO2, a traffic-related air pollutant and a major component of urban smog; PM2.5, a heterogeneous mixture of fine particles in the air; and O3, a common secondary air pollutant.28 We recently estimated daily ambient NO2, PM2.5, and O3 levels at 1 km2 spatial resolution across the contiguous United States using an ensemble machine learning model.29, 30, 31 We calculated the daily average for each county based on all covered 1 km2 grid cells (i.e., we calculated the arithmetic mean of daily air pollutant concentrations at 1 km2 grid cells whose centroids fall within the boundary of that county). We then further calculated the annual mean (2010–2016) for NO2 and PM2.5 and the warm-season mean (2010–2016) for O3, defined as May 1 to October 31, which is a standard time window for examining the association between ozone and mortality.31 Although more recent exposure data were not available, county-specific mean concentrations of air pollutants across years are highly correlated.28

Statistical Methods

We fit zero-inflated negative binomial mixed (ZINB) models to estimate the associations between long-term exposure to NO2, PM2.5, and O3 and COVID-19 case-fatality rates and mortality rates. The ZINB model comprises a negative binomial log-linear count model and a logit model for predicting excess zeros.32 The former was used to describe the associations between air pollutants and COVID-19 case-fatality rate among counties with at least one reported COVID-19 case. The latter can account for excess zeros in counties that had not observed a COVID-19 death as of July 17, 2020. We fit single-pollutant, bi-pollutant, and tri-pollutant models to estimate the effects of each pollutant without and with control for co-pollutants. All analyses were conducted at the county level. For the negative binomial count component, results are presented as percentage change in case-fatality rate or mortality rate per interquartile range (IQR) increase in each air pollutant concentration. IQRs were calculated based on mean air pollutant levels across all 3,122 counties. Similar results are presented as odds ratios for the excess zero component. We included a random intercept for each state because observations within the same state tended to be correlated, potentially due to similar COVID-19 responses, quarantine and testing policies, health care capacity, sociodemographics, and meteorological conditions.

As different testing practices may bias outcome ascertainment, we adjusted for state-level COVID-19 test positive rate4 (i.e., a high positive rate could imply that the confirmed case numbers were limited by the ability of testing, thus upward biasing the case-fatality rate). To model how different counties may be at different time points on the epidemic curve (i.e., phase of epidemic), we adjusted for days both since the first case and since the 100th case within a county through July 17. In addition, we adjusted for potential confounders and covariates that may also contribute to heterogeneity in the observed COVID-19 rates and thus may confound associations with long-term air pollution exposure. These include county-level health care capacity, population mobility, population density, sociodemographics, socioeconomic status (SES), race and ethnicity, behavior risk factors, and meteorological factors. Specifically, health care capacity was measured by the number of intensive care unit (ICU) beds, hospital beds, and active medical doctors per 1,000 people.33 Population travel mobility index, based on anonymized location data from smartphones, was used to account for changes in travel distance in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic.34 SES was measured by social deprivation index,35 a commonly used measure of area-level SES, composed of income, education, employment, housing, household characteristics, transportation, and demographics. Sociodemographic covariates included population density, percentage of elderly (age ≥60), and percentage of male. Race and ethnicity included percentage of Black and percentage of Hispanic in each county. We also obtained behavioral risk factors, including population mean body mass index and smoking rate, and meteorological variables,36 including air temperature and relative humidity. Additional information about these covariates, including data sources, is given in the Supplemental Information.

To control for potential residual spatial trends and confounding, we included spatial smoothers within the model using natural cubic splines with 5 degrees of freedom for both county centroid latitude and longitude. To examine the presence of spatial autocorrelation in the residuals, we calculated Moran's I of the standardized residuals of tri-pollutant main models among counties within each state. Statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance and confidence intervals were calculated with an alpha of 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.4.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted a series of 66 sets of sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results to outliers, confounding adjustment, and epidemic timing (Figures 4 and 5). Given that New York City has had far more COVID-19 cases and deaths than any other region, we excluded all five counties within New York City in one sensitivity analysis. In another, we restricted the study to the most recent 4 weeks (June 20 to July 17), when the case count and death count may be more reliable and accurate compared with earlier periods. We also conducted sensitivity analysis by using air pollution data averaged between 2000 and 2016. To assess the importance of individual confounders or covariates, we fit models by omitting a different set of covariates for each model iteration and compared effect estimates.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Emory HERCULES Exposome Research Center through the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant P30ES019776). S.G. acknowledges funding support provided by the National Science Foundation (award BCS-2027375). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. The authors would like to thank Qian Di, Weeberb J. Requia, and Yagung Wei for contributions to the generation of air pollution data. Data will be made available upon request.

Author Contributions

D.L., L.S., and H.C. designed the research and directed its implementation; D.L., L.S., J.Z., P.L., J.S., and S.G. prepared datasets; D.L., H.C., and L.S. analyzed data; D.L., L.S., and J.Z. wrote the paper and made the tables; L.S. made the figures; and all authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Published: October 8, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100047.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The New York times. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html

- 3.USAFACTS. 2020. https://usafacts.org/articles/detailed-methodology-covid-19-data/

- 4.1Point3Acres.com. 2020. https://coronavirus.1point3acres.com/

- 5.Weiss R.A., McMichael A.J. Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nat. Med. 2004 Dec;10:S70–S76. doi: 10.1038/nm1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin K., Fong D.Y., Zhu B., et al. Environmental factors on the SARS epidemic: air temperature, passage of time and multiplicative effect of hospital infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 2006;134:223–230. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heymann D.L. Social, behavioural and environmental factors and their impact on infectious disease outbreaks. J. Publ. Health Pol. 2005;26:133–139. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu G., Li X., Hu L., et al. An imperative need for research on the role of environmental factors in transmission of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:3730–3732. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C., Chen R., Sera F., et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:705–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anenberg S.C., Henze D.K., Tinney V., et al. Estimates of the global burden of ambient PM 2.5, ozone, and NO2 on asthma incidence and emergency room visits. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018;126:107004. doi: 10.1289/EHP3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhanti B.A., Chang H.H., Winquist A., et al. Ambient air pollution and emergency department visits for asthma: a multi-city assessment of effect modification by age. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2016;26:180–188. doi: 10.1038/jes.2015.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciencewicki J., Jaspers I. Air pollution and respiratory viral infection. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007;19:1135–1146. doi: 10.1080/08958370701665434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayyagari V.N., Januszkiewicz A., Nath J. Effects of nitrogen dioxide on the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1, neutrophil adhesion, and cytotoxicity: studies in human bronchial epithelial cells. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007;19:181–194. doi: 10.1080/08958370601052121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang D., Moutinho J.L., Golan R., et al. Use of high-resolution metabolomics for the identification of metabolic signals associated with traffic-related air pollution. Environ. Int. 2018;120:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang D., Ladva C.N., Golan R., et al. Perturbations of the arginine metabolome following exposures to traffic-related air pollution in a panel of commuters with and without asthma. Environ. Int. 2019;127:503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golan R., Ladva C., Greenwald R., et al. Acute pulmonary and inflammatory response in young adults following a scripted car commute. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2018;11:123–136. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui Y., Zhang Z.-F., Froines J., et al. Air pollution and case fatality of SARS in the People’s Republic of China: an ecologic study. Environ. Health. 2003;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yongjian Z., Jingu X., Fengming H., et al. Association between short-term exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 infection: evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;727:138704. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contini D., Costabile F. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020. Does Air Pollution Influence COVID-19 Outbreaks? [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi L., Zanobetti A., Kloog I., et al. Low-concentration PM2. 5 and mortality: estimating acute and chronic effects in a population-based study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016;124:46–52. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogen Y. Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to the coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality rate. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:138605. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conticini E., Frediani B., Caro D. Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy? Environ. Pollut. 2020;261:114465. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbey D., Colome S., Mills P., et al. Chronic disease associated with long-term concentrations of nitrogen dioxide. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 1993;3:181–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faustini A., Rapp R., Forastiere F. Nitrogen dioxide and mortality: review and meta-analysis of long-term studies. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44:744–753. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gan W.Q., Davies H.W., Koehoorn M., et al. Association of long-term exposure to community noise and traffic-related air pollution with coronary heart disease mortality. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012;175:898–906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bevelander M., Mayette J., Whittaker L.A., et al. Nitrogen dioxide promotes allergic sensitization to inhaled antigen. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3680–3688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu X., Nethery R.C., Sabath B.M., et al. Exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20054502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health Effect Institute Panel on the Health Effects of Traffic-Related Air Pollution. Traffic-related air pollution: a critical review of the literature on emissions, exposure, and health effects. Health Effects Institute; 2010.

- 29.Di Q., Amini H., Shi L., et al. An ensemble-based model of PM2.5 concentration across the contiguous United States with high spatiotemporal resolution. Environ. Int. 2019;130:104909. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.104909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Q., Amini H., Shi L., et al. Assessing NO2 concentration and model uncertainty with high spatiotemporal resolution across the contiguous United States using ensemble model averaging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;54:1372–1384. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Requia W.J., Di Q., Silvern R.F., et al. An ensemble learning approach for estimating high spatiotemporal resolution of ground-level ozone in the contiguous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:11037–11047. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garay A.M., Hashimoto E.M., Ortega E.M., et al. On estimation and influence diagnostics for zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2011;55:1304–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Area health Resources Files. 2019. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf

- 34.Gao S., Rao J., Kang Y., Liang Y., et al. Mapping county-level mobility pattern changes in the United States in response to COVID-19. arXiv:2004.04544, Available at SSRN 3570145. 2020.

- 35.Butler D.C., Petterson S., Phillips R.L., et al. Measures of social deprivation that predict health care access and need within a rational area of primary care service delivery. Health Serv. Res. 2013;48:539–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia Y., Mitchell K., Ek M., et al. Continental-scale water and energy flux analysis and validation for the North American Land Data Assimilation System project phase 2 (NLDAS-2): 1. Intercomparison and application of model products. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012;117 doi: 10.1029/2011JD016048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.