Summary

The Ras/PI3K/ERK signaling network plays fundamental roles in cell growth, survival, and migration and is frequently activated in cancer. Here we show that the activities of the signaling network propagate as coordinated waves, biased by growth factor, which drive actin-based protrusions in human epithelial cells. The network exhibits hallmarks of biochemical excitability: annihilation of oppositely directed waves, all-or-none responsiveness, and refractoriness. Abrupt perturbations to Ras, PI(4,5)P2, PI(3,4)P2, ERK, and TORC2 alter the threshold, observations which define positive and negative feedback loops within the network. Oncogenic transformation dramatically increases the wave activity, the frequency of ERK pulses, and the sensitivity to EGF stimuli. Wave activity was progressively enhanced across a series of increasingly metastatic breast cancer cell lines. The view that oncogenic transformation is a shift to a lower threshold of excitable Ras/PI3K/ERK network, caused by various combinations of genetic insults, can facilitate assessment of cancer severity and effectiveness of interventions.

In Brief

Zhan et al. investigate excitability of the Ras/PI3K/ERK signaling network. They demonstrate that activities propagate as coordinated waves on the cell cortex and delineate the molecular feedbacks that cause excitability. Transformed cells display more waves suggesting that cancer can be viewed as a low threshold state of the network.

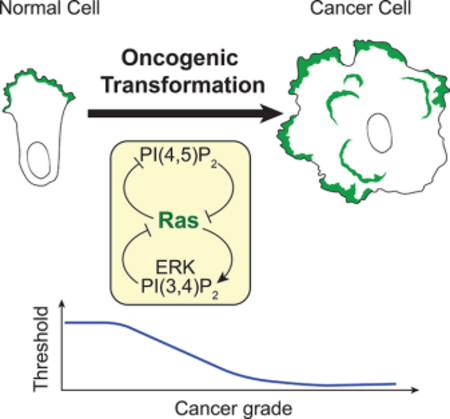

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Studies of the signal transduction and cytoskeletal events involved in rapid morphological changes primarily in Dictyostelium cells have led to the “excitable network hypothesis”. It proposes that self-organizing excitable signal transduction activities at the cell cortex provide global control of acto-myosin based protrusions that underlie cell dynamics. External chemical and biomechanical stimuli can guide cells and be integrated by influencing the overall threshold of the network (Gerisch et al., 2004; Weiner et al., 2007; Arai et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2013; Taniguchi et al., 2013; Nishikawa et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2014; Miao et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). The generality of this hypothesis and its ability to explain transitions of cell behavior such as oncogenic transformation remains to be tested.

Among the patterns that excitable systems can display are propagating waves on two-dimensional surfaces and waves of cytoskeletal events have indeed been observed in a variety of cells. Travelling actin waves were initially discovered and have been extensively investigated in Dictyostelium cells (Vicker et al., 2002; Inagaki et al., 2017). Waves of SCAR/WAVE and F-actin steer the movement of neutrophils (Weiner et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2016). Additional examples include F-actin waves in mast cells (Wu et al., 2018), in spreading lymphocytes and macrophages (Lam Hui et al., 2014), in breast cancer cells (Marchesin et al., 2015), in Xenopus oocytes (Bement et al., 2015), in fish keratocytes (Barnhart et al., 2017), and in extending neuronal axons (Winans et al., 2016) and integrin waves in osteosarcoma cells (Case et al., 2011).

Studies in Dictyostelium cells suggest the waves of cytoskeletal activity are driven by a signal transduction excitable network (STEN) which involves Ras family proteins (Ras) and PI 3-kinases (PI3K). These signal transduction responses display features of biochemical excitability namely “all-or-nothing” behavior to suprathreshold stimuli and refractory period to repeated stimuli (Huang et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2014). Lowering or raising the threshold of the excitable network can alter the cellular protrusions and cell migration modes (Miao et al., 2017, 2019). However, the extent to which the excitability of signaling transduction network controls cytoskeletal activities in mammalian cells and whether the molecular interactions in these networks are conserved throughout evolution is unknown.

Elucidating the quantitative properties of the signaling networks controlling cell morphology is critical for understanding and treating cancer. The Ras/PI3K/ERK signaling network is frequently mutated in cancer and leads to oncogenic transformation (Basolo et al., 1991; Imbalzano et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009). It is known that the excess activation of a single oncogene such as Kras is able to trigger hundreds of protein interactions and signaling feedbacks during transformation (Ye et al., 2016; Martinko et al., 2018). However, there is a lack of systems-level understanding of how these interactions and feedbacks are intrinsically regulated, which largely explains the poor outcome of clinical practices that target various single components of the signaling networks.

These considerations prompted us to investigate the excitable properties of the Ras/PI3K/ERK network in human epithelial cells, and the role of excitability in oncogenic transformation. We surveyed a series of mammalian cell lines and found that MDA-MB-231 cancer-derived cells displayed traveling Ras-PI3K-F-actin waves on the basal surface. We examined MDA-MB-231 cells and non-tumorigenic mammary cell line MCF-10A for evidence of biochemical excitability and the capacity of perturbations to alter these events and cellular protrusions. Both cell lines displayed all-or-nothing responsiveness and refractory periods. External stimuli and acute synthetic perturbations altered wave and/or protrusion behaviors as well as ERK pulse frequency. These observations allowed us to delineate the feedback loops that bring about excitability. Furthermore, activation of Ras enhanced wave activity in MDA-MB-231 cells, triggered de novo wave activity in MCF-10A cells, and increased protrusions in both. The invasive behavior across a series of increasingly metastatic breast cancer cell lines strongly correlates with elevated wave activity. Taken together, these studies suggest that excitable Ras/PI3K/ERK network as driver of cellular protrusions is a general property of migrating cells and that cellular transformation can be considered as a shift to a lower threshold or set point of these networks.

Results

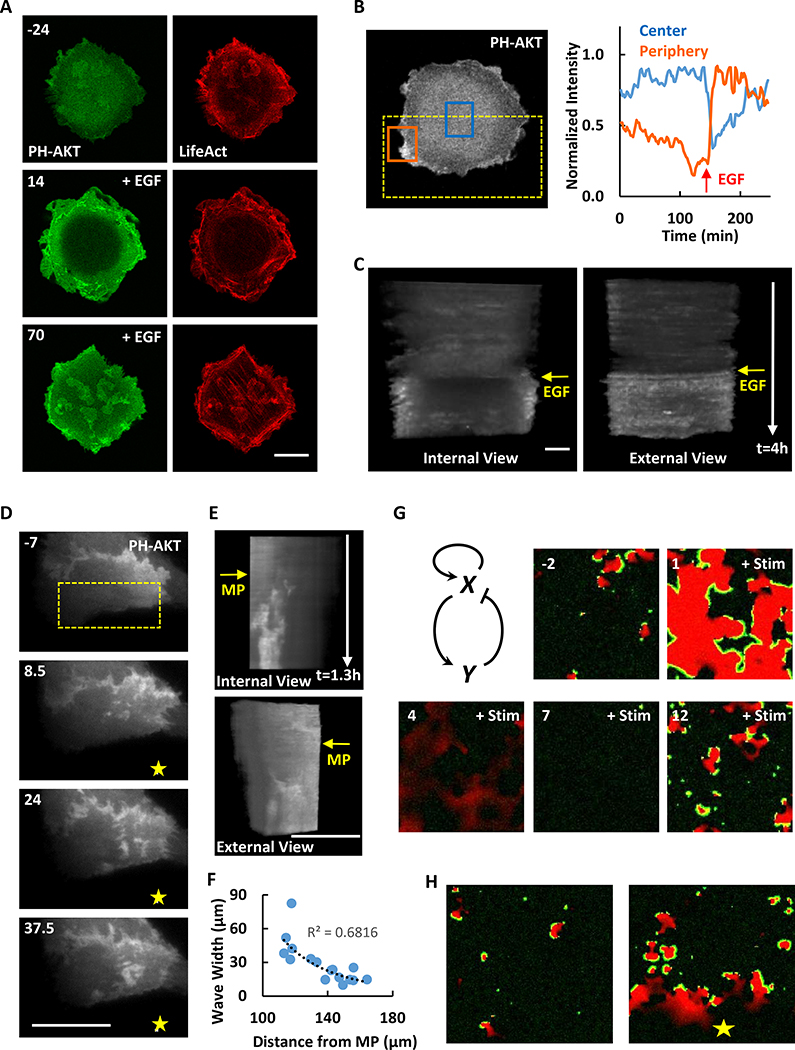

Coupled Signal Transduction and Cytoskeleton Waves Drive Protrusions

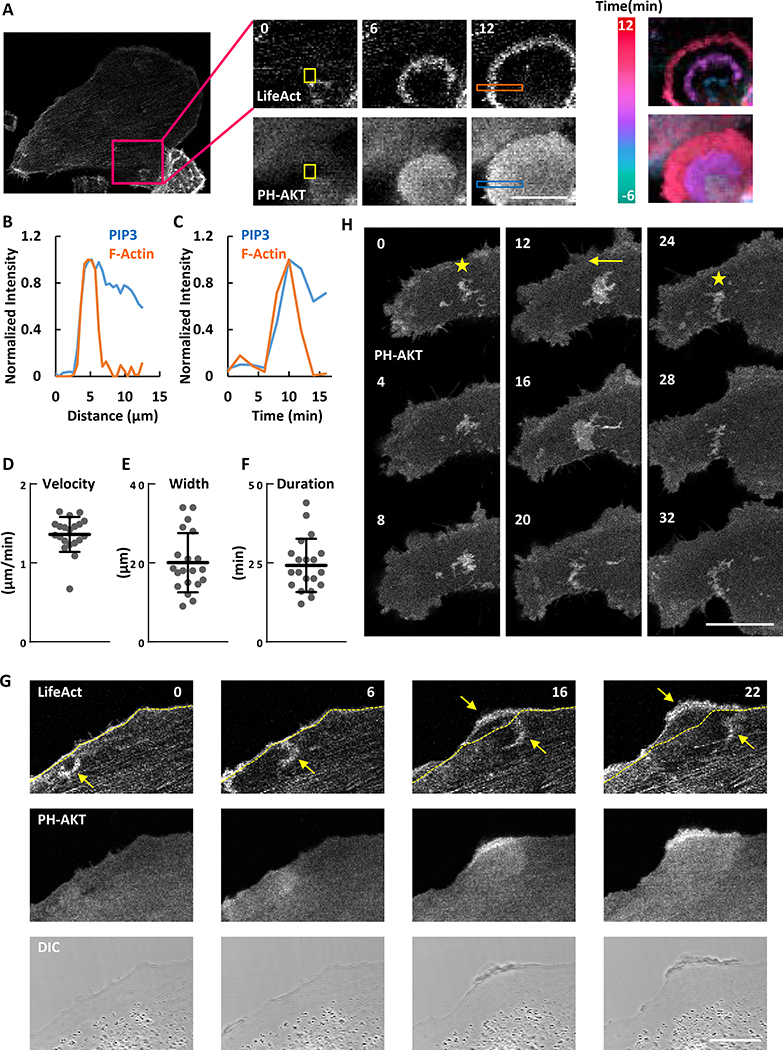

To monitor signal transduction and cytoskeleton activities at the ventral surface of MDA-MB-231 cells, we co-expressed biosensors for F-actin (Lifeact) and PIP3 (PH-AKT). As shown in Figure 1A and Movie S1, the signal transduction and cytoskeleton activities initiated spontaneously and propagated as waves along the basal membrane. The activities were highly coordinated; the leading edge and peak of the actin and PIP3 waves coincided. Whereas the cytoskeletal wave was confined to 5 μm, the lagging edge of the signal transduction wave was broader (Figure 1B). Similarly, as the waves passed, the signal transduction and cytoskeleton activities initially increased in parallel and peaked at about 5 min. The cytoskeletal activity returned to basal within about 5 min while signal transduction activity lasted longer (Figure 1C). The velocity of the travelling waves was 1.36 +/− 0.22 μm/min (mean +/− SD, n=20) (Figure 1D). Many of the coupled F-actin and PIP3 waves started within the ventral surface and died out before reaching the edge of these large cells. The maximal lateral expansion of the waves was 20.05 +/− 7.51 μm (mean +/− SD, n=20) with a duration of 24.20 +/− 8.43 min (mean +/− SD, n=20) (Figure 1E and 1F). When a wave reached the edge of the cell, a ruffle strongly labeled with LifeAct and PH-AKT formed. This suggests that protrusions in epithelial cells are driven by coordinated PIP3/F-actin waves (Figure 1G and Movie S1).

Figure 1. Cytoskeletal and signaling activities propagate as waves on the basal surface of the MDA-MB-231 cell.

(A) Confocal images focusing at the ventral surface of the MDA-MB-231 cell expressing biosensors for F-actin (LifeAct-RFP) and PIP3 (PH-AKT-GFP) (also see Movie S1). Color-coded overlays show progression of waves as a function of time.

(B) Relative amount of F-actin and PIP3 across the orange and blue boxes scan in (A).

(C) Temporal change of F-actin and PIP3 in the yellow boxes in (A).

(D-F) Distribution of the velocity (D), maximum width (E) and duration (F) among waves (mean ± S.D. of N = 20 waves in one cell). </p/>(G) Example of a circular wave with one edge propagating outwards to drive the formation of a protrusion upon reaching the cell perimeter (arrow indicates wave and dashed line indicates initial cell perimeter) (also see Movie S1).

(H) Time-lapse confocal images of PH-AKT showing transitions between standing (marked with star) and travelling (marked with arrow) waves (also see Movie S1).

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

In some instances, travelling waves stopped their forward progression and “hovered” in place. Figure 1H and Movie S1 show an example of a PIP3 wave which displayed some dynamic changes but did not propagate laterally for about 12 min. Then the wave began to propagate and continued for about 12 min before it stopped again. After about 8 min, it started to propagate again.

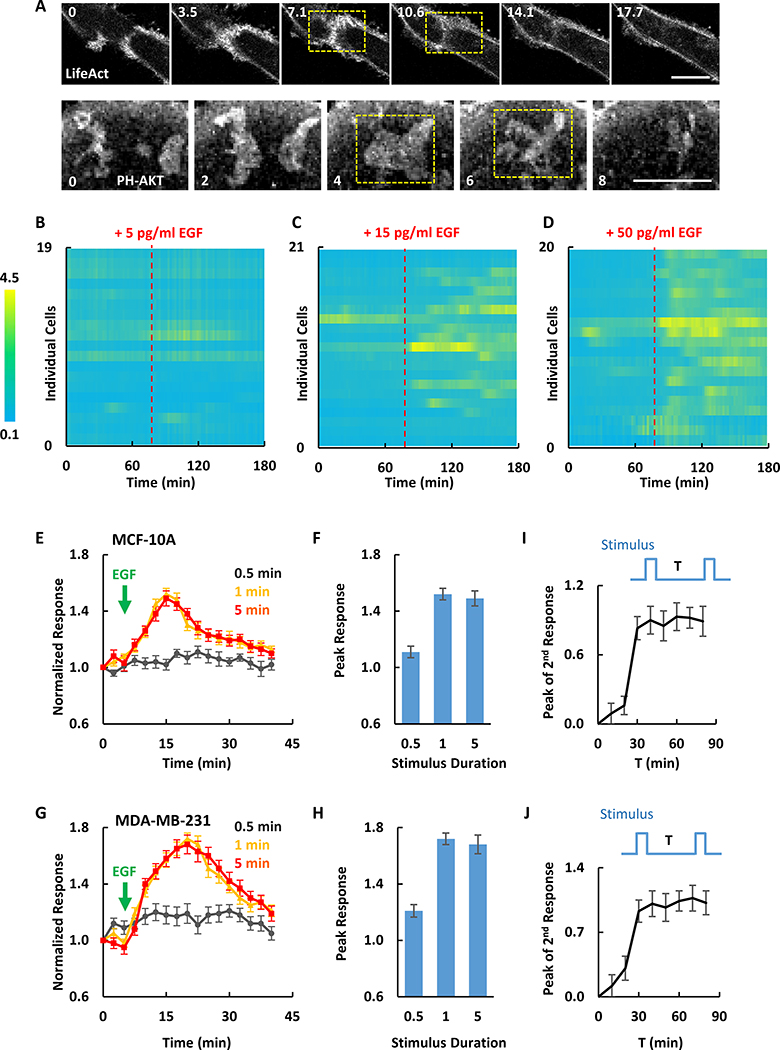

Signal Transduction and Cytoskeletal Networks are Excitable

Previous studies in migrating Dictyostelium amoebae demonstrated that signal transduction and cytoskeletal activities display features of excitable systems including mutually annihilating waves, all-or-none responses, and the existence of a refractory period (Gerisch et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2013). The following results indicate that an excitable system underlies the signaling and cytoskeletal waves in MDA-MB-231. First, when two oppositely propagating waves of Lifeact merged (3.5 min in Figure 2A upper panel), they did not cross, but instead merged and disappeared (7.1 and 10.6 min in Figure 2A upper panel; Movie S2). Similar annihilation was also observed for colliding waves of PH-AKT (Figure 2A lower panel).

Figure 2. The signaling network is excitable.

(A) Two colliding actin or PIP3 waves in MDA-MB-231 cells annihilated (dashed yellow boxes) (also see Movie S2).

(B-D) Responses of ERK-KTR to EGF stimulation of different concentrations in MCF-10A cells. Ratios of cytosolic to nucleus ERK-KTR signal were plotted over time for 19, 21 and 20 cells in one experiment as shown in (B), (C) and (D). EGF stimulations were applied at 78 min.

(E-H) Quantification of PIP3 responses to 0.5, 1 and 5 min saturated EGF stimuli in MCF-10A (E and F) and MDA-MB-231 (G and H) cells (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 10 cells of 3 experiments).

(I and J) Peak responses to the second of two 1 min stimuli separated by interval T in MCF-10A (I) and MDA-MB-231 (J) cells (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 10 cells of 3 experiments). Example of individual cell response is shown in Figure S1A.

Cells were starved in pure DMEM/F-12 (MCF-10A) or DMEM (MDA-MB-231) medium for 24 hours before EGF stimulation. The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Second, we examined ERK activation and PIP3 production, two downstream effectors of Ras, in response to EGF stimuli of increasing dose and duration. We detected ERK activation by the nuclear exit of its biosensor ERK-KTR (Regot et al., 2014) in response to EGF. Stimuli of 5, 15, and 50 pg/ml induced ~15%, ~70%, ~90% of cells to start intermittent ERK activation (showing at least 50% increase) (Figure 2B–D), similar to previously reported (Albeck et al., 2013). In addition, MCF10A cells had elevated PIP3 in response to 1 and 5 min, but rarely to 30 sec, saturating EGF stimuli (Figure 2E). Notably, the response started after removal of 1 min stimulus and proceeded to completion (Figure 2E). Moreover, the magnitude and kinetics of the average responses to 1- or 5-min stimuli were nearly identical (Figure 2E and 2F). A similar duration threshold was obtained in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 2G and 2H). The behavior was very “cooperative”: fitting the peak response versus the duration to sigmoidal curve yielded Hill coefficients over 30 for both MCF10A and MDA-MB-231. These observations suggested that stimuli crossing a threshold can trigger full responses.

Third, we applied paired 1 min stimuli separated by various intervals. The second stimulus failed to trigger a full response unless a sufficient recovery time was allowed, suggesting the existence of a refractory period (Figure 2I, 2J and S1A). In both cell types, the kinetics of the recovery showed an initial lag of about 10 min, and the magnitude of the second response was half maximal after 25 min of recovery. Taken together, these observations indicate that cytoskeletal and signaling activities in MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells indeed display salient features of excitable systems.

Exogenous EGF Perturbs Signal Transduction and Cytoskeletal Waves

We examined the effects of uniform and gradient EGF stimuli on wave behavior. When a MDA-MB-231 cell was given a uniform EGF stimulus, the coupled F-actin and PIP3 waves initially disappeared and were replaced by a bright ring of signal around the cell perimeter. After about 50 min, waves began to reappear in the central region as the edge signal decreased (Figure 3A and 3B; Movie S3). Eventually they were more prevalent than those in cell prior to stimulation. The temporal evolution of the responses over the peripheral and interior regions was evident in kymographs of cropped images (Huang et al., 2013) (Figure 3C). We next used an EGF-filled micropipette to generate a spatial gradient of stimulation. At the steady state, PH-AKT waves that formed toward the high side of the EGF gradient were wider, more intense, and longer-lasting than those closer to the low side of the gradient (Figure 3D–F and Movie S3).

Figure 3. Global and local stimuli change the activity of cytoskeletal and signaling waves.

(A) Confocal images of the MDA-MB-231 cell showing the response of PIP3 and actin waves to global EGF stimulation (2 ng/ml, added at 0 min) (also see Movie S3). Cells were starved in pure DMEM medium for 2 hours before EGF stimulation.

(B) Quantification of PIP3 change at the center (blue box) or periphery (orange box) of the cell ventral surface in (A).

(C) Internal and external views of stacked frames of ROI (dashed yellow box) in (B).

(D) Response of PIP3 wave to local EGF stimulation. Yellow star indicates the position of micropipette (filled with 10 μg/ml EGF, applied at 0 min). Also see Movie S3. Cells were starved in pure DMEM medium for 2 hours before EGF stimulation.

(E) Internal and external views of stacked frames of ROI (dashed yellow box) in (D).

(F) Wave maximum width versus distance to the micropipette in (D). The dashed black line is the power trend line.

(G) Computational simulation of waves response to global stimulus based on an activator-inhibitor scheme. Green is activator (X) while red is inhibitor (Y). Global stimulus was added at time 0 (a.u.) (also see Movie S4).

(H) Computational simulation of waves response to local stimulus. Green is activator while red is inhibitor. Yellow star indicates the position of stimulus (also see Movie S4).

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Building on a previously published mathematical model of the excitable signaling network (Xiong et al., 2010), we were able to simulate the responses of cells to uniform and gradient stimuli. In the two-dimensional simulation, prior to stimulation, spontaneous waves were triggered by noise. A uniform stimulus induced a global response followed by a brief period of inactivity before the waves were reinitiated (Figure 3G and Movie S4). These results are generally in agreement with the observed responses in MDA-MB-231 cells except that the global response in live cells was primarily seen at the perimeter rather than across the basal surface (Figure 3A). With a gradient stimulus, more abundant and wider waves were generated close to the high side of the gradient (Figure 3H and Movie S4), consistent with the observations in Figure 3D.

A Small Decrease in PI(4,5)P2 Activates the Signal Transduction Network and Lowers the Threshold of the Network

PI(4,5)P2, as the substrate of the reaction, is reduced during the production of PI(3,4,5)P3 by activated Ras-PI3K network. We therefore tested how acute perturbations to PI(4,5)P2 reduction affect excitability in MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells. To rapidly lower the level of PI(4,5)P2, we recruited the 5-phosphatase, Inp54p, using chemically induced dimerization (CID) (Figure S1B). Membrane recruitment of Inp54p caused an immediate reduction of PI(4,5)P2, detected by the translocation of the PI(4,5)P2-binding domain PH-PLCΔ, from the membrane to the cytoplasm (Figure S1C). Recruitment of a catalytically inactive mutant Inp54p (D281A) did not affect PH-PLCΔ localization (Figure S1D).

In MCF-10A cells, PI(4,5)P2 reduction triggered two distinct types of responses: spreading or retraction (Figure S2A). Spreading cells increased their basal surface area and showed ruffles, whereas retracting cells formed blebs around cell perimeter. We noticed that, compared to retracting cells, the spreading cells had lower expression levels of Inp54p (Figure S2B), suggesting that the type of response depends on the extent of PI(4,5)P2 reduction. To test this possibility, we observed individual cells exposed to increasing doses of rapamycin. Whereas a low dose (5 nM) rapamycin caused a slight increase in cytosolic PH-PLCΔ and strong cell spreading, a subsequent higher dose (1 μM) of rapamycin caused a further increase in cytosolic PH-PLCΔ which led to contraction (Figure S2C and S2D). Moreover, when cells were sorted according to the intensity of Inp54p fluorescence, most of the low or high expressers, respectively, spread or retracted (Figure S2E and S2F). Cells expressing a catalytically inactive Inp54p mutant did not respond to rapamycin addition (Figure S2F).

The morphological changes induced by modest lowering of PI(4,5)P2 in MCF-10A cells were dynamic and associated with biochemical responses. Within minutes of addition of rapamycin, peripheral regions of the cell began to spread rhythmically (Figure 4A and Movie S5). Kymographs of the length of the lamellipodia revealed that the protrusions propagated around the perimeter with a period of about 20 min, suggesting they are driven by scroll waves (Figure 4B). The protrusions were labeled with RBD (biosensor for active Ras) (Figure 4C, S3A and 4D; Movie S5) and PH-AKT (Figure S3B), indicating locally elevated Ras and PI3K activity at protrusions drove the oscillatory spreading. The overall activity of Ras also increased when PI(4,5)P2 was lowered (Figure 4E and 4F). Elevated PIP3 production on cell protrusions by PI(4,5)P2 lowering was also detected in cells treated with JLY (Figure S4A–D), a cocktail of cytoskeletal inhibitors used to block the cell shape changes (Peng et al., 2011), suggesting that cytoskeletal activity is not required for the activation of signaling. We next examined the downstream effectors of these activities. Immunofluorescence staining revealed a wide band of S473-AKT phosphorylation (Figure S3C), indicating the activation of mTORC2 at the protrusions (Manning et al., 2017). We also noticed that lowering of PI(4,5)P2 triggered ERK activation (Figure 4G and 4H; Movie S5). The extent of ERK activation within the cell population was heterogeneous (Figure 4I). Furthermore, during continuous stimulation, the elevated steady-state level fluctuated (Figure 4H and 4I). Together the results indicate that PI(4,5)P2 lowering activates the Ras signaling network, which leads to activation of multiple downstream events.

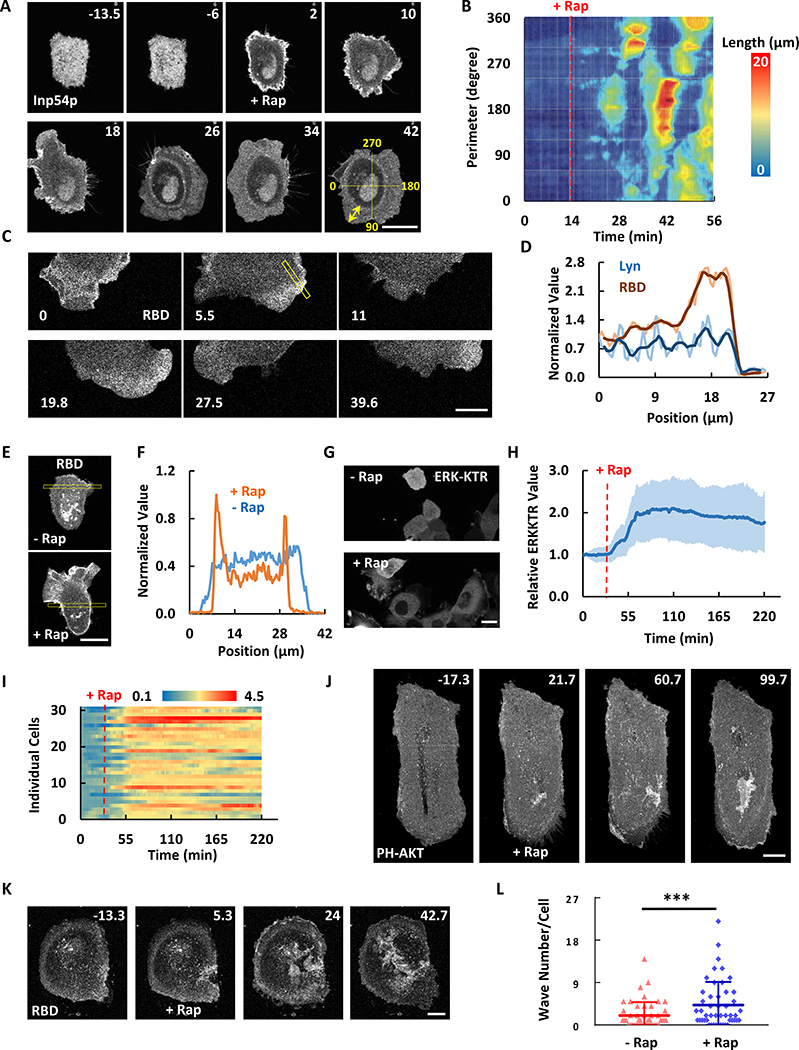

Figure 4. PI(4,5)P2 reduction changes cell morphology and signaling responses.

(A) Time-lapse confocal images of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Inp54p (channel shown). 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min (also see Movie S5).

(B) Kymograph of lamellipodia length around the perimeter of the cell in (A). Quantification of cell area change is shown in Figure S2F.

(C) Time-lapse confocal images of the bottom surface of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB (shown in Figure S3A), FKBP-Inp54p, and RBD (channel shown) after 1μM rapamycin indicate active Ras enriched at the oscillatory protrusions. Also see Movie S5.

(D) Quantification of the boxes scan in (C) and Figure S3A. The bold are the smoothed lines.

(E) Confocal images of the middle plane of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB, FKBP-Inp54p, and RBD (channel shown) before and after 1μM rapamycin.

(F) Quantification of the boxes scan in (E).

(G) Confocal images of MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB, FKBP-Inp54p, and ERK-KTR (channel shown) before and after 1μM rapamycin (also see Movie S5).

(H and I) Ratios of cytosolic to nucleus ERK-KTR signal in population average (H, mean ± S.D. of N = 31 cells in one experiment) and individual (I) MCF-10A cells.

(J and K) Time-lapse confocal images showing increased PIP3 waves (J, also see Movie S6) or Ras waves (K, also see Movie S6) formation after lowering PI(4,5)P2 in MDA-MB-231 cells. 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min. T-stack analysis of (J) is presented in Figure S3D.

(L) Quantification of wave number change in (J and K). Individual waves were followed from origin to end in videos. The total wave number for each cell was quantified during 1 h imaging windows before and after 1μM rapamycin (mean ± S.D. of N = 48 cells, 5 experiments). Paired t test, P = 0.0004.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

In MDA-MB-231 cells, slight PI(4,5)P2 lowering led to more PH-AKT and RBD waves in the interior regions of the basal cell surface and more ruffles at the cell edge. The increase in waves covering the basal surface was due to both de novo initiation as well as growth in pre-existing waves (Figure 4J–L; Movie S6). The temporal evolution of these waves is demonstrated by the t-stack of a section through the images (Figure S3D). Patches of PIP3 or RBD appeared in the interior upon rapamycin addition, indicating new wave formation. PIP3 or RBD enriched oscillatory protrusions also appeared on the perimeter. As in MCF-10A cells, slight decrease of PI(4,5)P2 mostly caused spreading while large depletion of PI(4,5)P2 caused retraction and blebbing in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S3E).

Theoretically in excitable systems, the amount of spontaneous activity depends on the set point or threshold of the system. The generation of dynamic protrusions in MCF-10A cells and traveling waves in MDA-MB-231 cells suggested that PI(4,5)P2 lowering decreased the threshold of the excitable signaling network. To test this idea, we compared EGF-triggered ERK responses of MCF-10A cells in the presence or absence of PI(4,5)P2 lowering. PI(4,5)P2 lowering led to a greater percentage of cells responding to sub-saturating EGF stimulation (Figure 5A–E). When stimulated with increasing levels of EGF, the dose-response curve of PI(4,5)P2-reduced cells was left-shifted relative to that of the control cells (Figure 5F). Together these results suggested that slight PI(4,5)P2 reduction lowers the threshold of the Ras-PI3K excitable signaling network and this is reflected in a greater sensitivity of ERK in EGF stimulation.

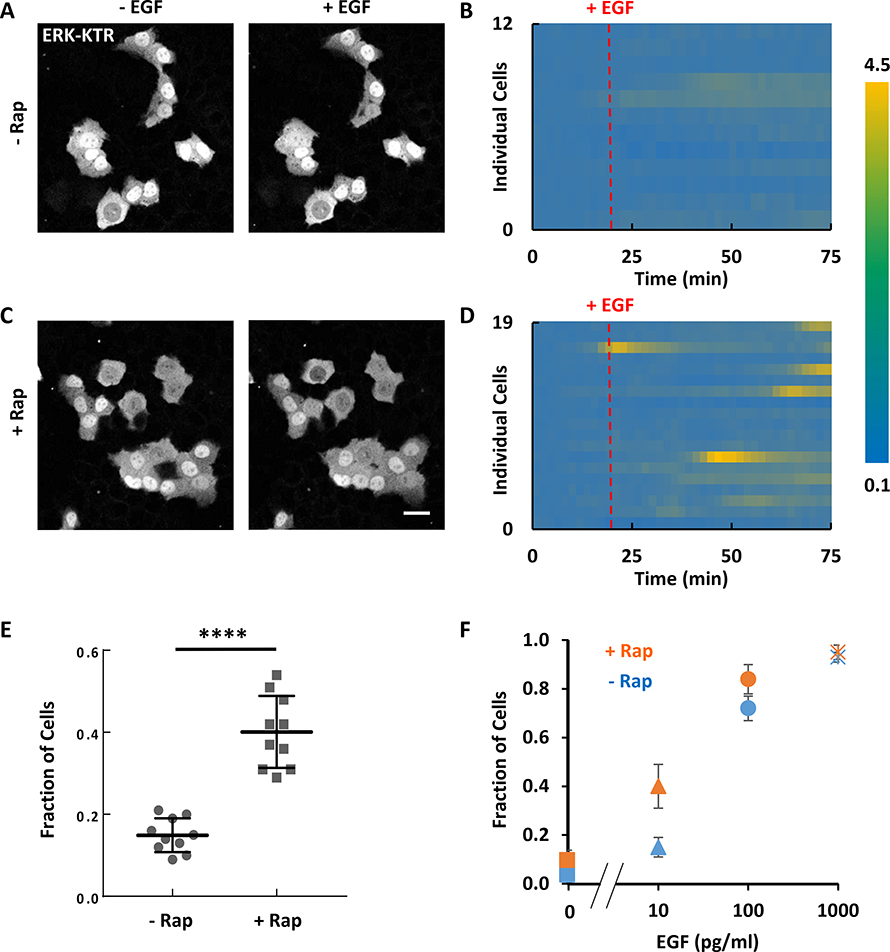

Figure 5. PI(4,5)P2 reduction lowers the threshold of ERK activation in MCF-10A cells.

(A-D) Responses of ERK-KTR to 10 pg/ml EGF stimulation in MCF-10A cells without (A and B) and with (C and D) PIP2 reduction by rapamycin-induced recruitment of Inp54p. Ratios of cytosolic to nucleus ERK-KTR signal over time for 12 and 19 individual cells are plotted in (B) and (D).

(E) Fraction of cells showing at least 50% increase in the ratio of cytosolic to nucleus intensity of ERK-KTR in response to 10 pg/ml EGF global stimulation without or with PIP2 reduction by rapamycin-induced recruitment of Inp54p (mean ± S.D. of N = 10 experiments). Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P < 0.0001.

(F) Fraction of cells responding to global stimulation of various concentrations of EGF in cells without or with PIP2 reduction by rapamycin-induced recruitment of Inp54p (mean ± S.D. of N = 10 experiments).

Cells were starved in pure DMEM/F-12 medium for 24 hours before stimulation. Scale bar labeled on images is 20 μm.

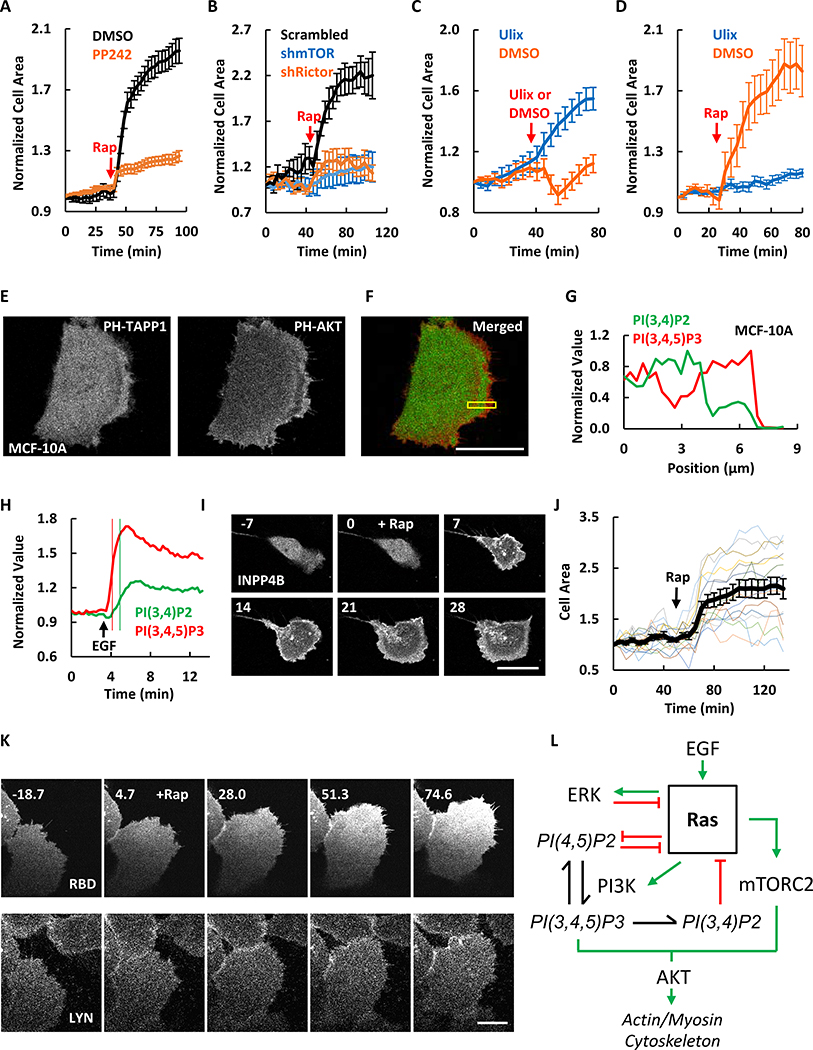

mTORC2 Links Signal Transduction and Cytoskeletal Activities

To further define the mediators of the morphological changes induced by PI(4,5)P2 reduction, we blocked key pathways downstream of Ras using small molecule inhibitors. PI3K inhibitor ZSTK474 caused retraction of protrusions and reduced the wave activities in unstimulated MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S4 E–I). The morphological changes induced by PI(4,5)P2 reduction still occurred in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor. In contrast, MCF-10A cells treated with PP242, which had abolished S473-AKT phosphorylation (Figure S5A), the PI(4,5)P2 lowering-induced cell spreading response was blocked (Figure S5C, S5D, and 6A). Consistently, the response was also blocked by knocking down of mTOR with shRNA (Figure S5E, S5G, S5H, and 6B). We do not believe that this effect is due to inhibition of mTORC1 since as noted above mTORC1 specific inhibitor rapamycin did not alter cell spreading behavior. It was further confirmed by the result that shRictor also blocked the cell spreading response induced by decreasing PI(4,5)P2 (Figure S5F, S5G, S5I, and 6B). Together these results suggest that effects of PI(4,5)P2 reduction on cytoskeletal activity act through a pathway involving mTORC2.

Figure 6. Molecular mechanisms that bring about excitability.

(A) Quantification of area changes of MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Inp54 (images shown in Figure S5C and S5D) before and after 1μM rapamycin (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 15 cells of 5 experiments). Cells were either pre-treated with DMSO or 10 μM mTOR inhibitor PP242 for 2h before imaging.

(B) Quantification of area changes of MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Inp54p (images shown in Figure S5G–I) transfected with scrambled, mTOR, or Rictor shRNAs before and after 1μM rapamycin (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 20 cells of 5 experiments).

(C) Quantification of area changes of MCF-10A cells before and after treated with DMSO or 10 μM Ulixertinib (ERK inhibitor) (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 20 cells for Ulix and 22 for DMSO of 3 experiments).

(D) Quantification of area changes of MCF-10A cells before and after rapamycin-induced PIP2 reduction (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 18 cells for Ulix and 17 for DMSO of 3 experiments). Cells were either pre-treated with DMSO or 10 μM Ulixertinib for 2h before imaging.

(E) Confocal images of MCF-10A cells expressing PH-TAPP1-GFP and PH-AKT-RFP.

(F) Merged images of both fluorescence channels in (E). Green is PH-TAPP1 and red is PH-AKT.

(G) Quantification of the boxes scan in (F). Similar results for MDA-MB-231 cells are shown in Figure S6A–C.

(H) PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 responses to global EGF (2 ng/ml) stimulation in MCF-10A cell. Thin vertical lines mark 50% values. Cells were starved in pure DMEM/F-12 medium for 24 hours before EGF stimulation.

(I) Time-lapse confocal images of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-INPP4B (channel shown). 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min.

(J) Quantification of the cell area changes of individual MCF-10A cells (colored lines) or population average (black line, mean ± S.E.M. of N = 15 cells of 3 experiments) before and after rapamycin-induced PI(3,4)P2 reduction. The phosphatase inactive control is shown in Figure S6D.

(K) Time-lapse confocal images of the ventral surface of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB (channel shown), FKBP-INPP4B, and RBD (channel shown). 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min. Quantification is shown in Figure S6E and S6F.

(L) Diagram of the working model. Green arrows indicate activating interactions while red bars indicate inhibitory interactions.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

ERK and PI(3,4)P2 are Negative Regulators in the Excitable Network

Since ERK is activated by PI(4,5)P2 lowering (Figure 4G–I), we tested the role of ERK in mediating the spreading response. Surprisingly the ERK inhibitor Ulixertinib alone caused more cell spreading (Figure 6C). Subsequent lowering of PI(4,5)P2 after ERK inhibition caused no further increase in cell spreading (Figure 6D). This suggests that the major role of ERK is a negative regulator of the system (Figure 6L).

Recent evidence suggests that PI(3,4)P2 has physiological roles in addition to being a product of PI(3,4,5)P3 degradation (Gewinner et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2016; Malek et al., 2017; Goulden et al., 2019). We compared the dynamic levels of PIP3 and PI(3,4)P2 using biosensors PH-AKT and PH-TAPP1. While PIP3 and PI(3,4)P2 both localized on cell protrusions, they were spatially separated. PIP3 formed a band at the perimeter and PI(3,4)P2 formed a trailing band back from the perimeter in both MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 6E–G, S6A–C).

We next measured the kinetics of PIP3 and PI(3,4)P2 changes in response to 2 ng/ml EGF in MCF-10A cells. Upon stimulation, PIP3 and PI(3,4)P2 increased globally on the membrane. PIP3 reached a peak within 2 min, while PI(3,4)P2 rose more slowly and peaked 1 min later (Figure 6H). The difference in the kinetics is consistent with the spatial relationship seen in propagating waves and protrusions.

To determine the role of PI(3,4)P2 in the excitable network, we assessed the effects of acute reduction of PI(3,4)P2. We used CID to recruit INPP4B to hydrolyze PI(3,4)P2. Upon the addition of rapamycin, MCF-10A cells begin to carry out oscillatory spreading, consistent with an increase in wave activity (Figure 6I, 6J and S6D). This contrasted strikingly to the effects of PIP3 depletion which caused cell retraction (Figure S4E and S4I). Furthermore, the morphological changes caused by PI(3,4)P2 reduction were accompanied by Ras activation as detected by its biosensor RBD (Figure 6K, S6E, and S6F). Together, these results suggests that PI(3,4)P2, activated following Ras and PI3K activation, provides a negative feedback loop to Ras activity (Figure 6L).

Oncogenic Transformation Causes Enhanced Excitability of the Signal Transduction Network

We examined the effect of Ras activation on network excitability and cell morphology. If the network outlined in Figure 6L is correct, an increase in Ras activity would be expected to lower the threshold and lead to increased excitability. To acutely activate Ras, we used chemically induced dimerization (CID) to rapidly recruit the CAAX-deleted constitutively active Kras_G12V to membrane-anchored Lyn-FRB upon rapamycin addition. In MCF-10A cells, Kras_G12V recruitment led to oscillatory cell spreading, similar to the effects of PI(4,5)P2 reduction (Figure 7A). The effects of recruiting Ras-GEF, CDC25, were similar to those induced by Kras_G12V (Figure 7B). In order to examine the effect of Ras activation on existing wave activities, we recruited CDC25 in MDA-MB-231 cells. As indicated by the PIP3 biosensor PH-AKT, activation of Ras led to an increase in the number of travelling waves on the basal surface of the cells (Figure 7C and Movie S7). As we have shown earlier, these changes are indicative of a lowered threshold of the signal transduction excitable network.

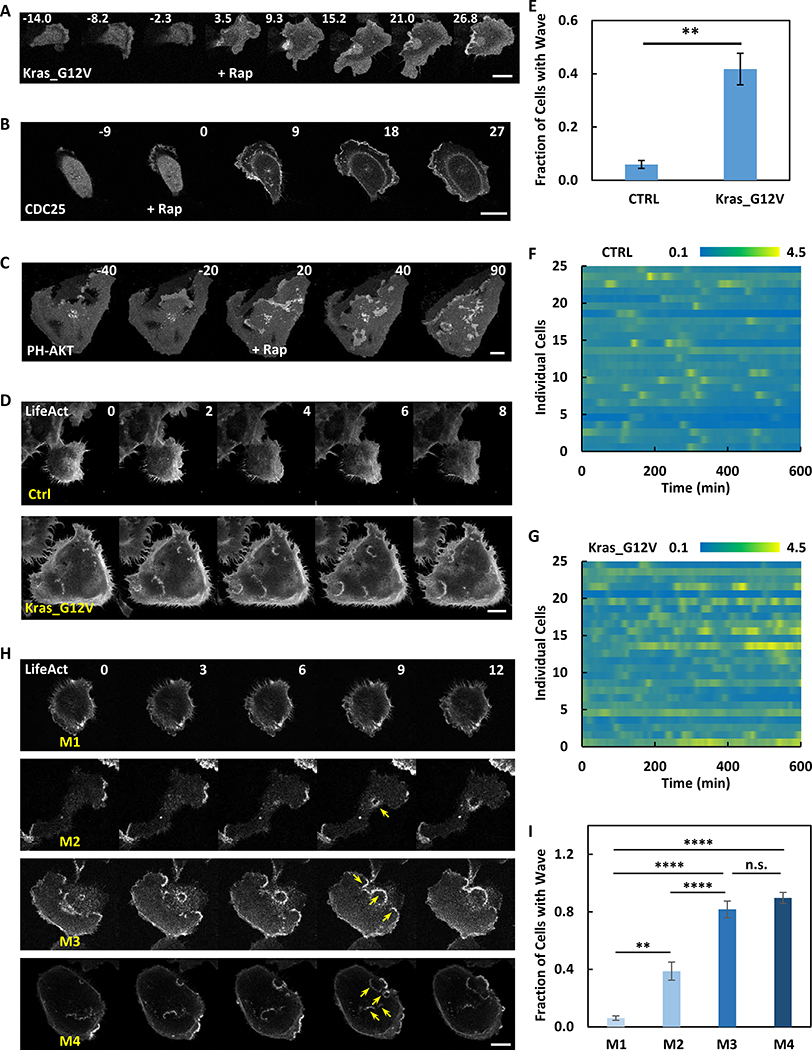

Figure 7. Oncogenic transformation causes enhanced excitability of the signal transduction network.

(A) Time-lapse confocal images of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Kras_G12V (channel shown). 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min.

(B) Time-lapse confocal images of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-CDC25 (channel shown). 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min.

(C) Time-lapse confocal images of MDA-MB-231 cell expressing Lyn-FRB, FKBP-CDC25, and PH-AKT (channel shown). 1μM rapamycin was added at 0 min. Also see Movie S7.

(D) Time-lapse confocal images of control or Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cells expressing LifeAct. Also see Figure S7C–F, and Movie S7 for additional examples.

(E) Quantification of fraction of cells with wave in control or Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cells during a 2-hour imaging window (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 4 independent experiments, 306 control cells and 347 Kras transformed cells). Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.0071.

(F and G) Heat map of ratios of cytosolic to nucleus ERK-KTR signal of control (F) or Kras_G12V transformed (G) MCF-10A cells. N = 25 cells of 2 experiments for each group.

(H) Time-lapse confocal images of M1~M4 MCF-10A cells expressing LifeAct. Also see Movie S7 for more examples. Yellow arrows indicate example waves.

(I) Quantification of fraction of cells with wave in M1~M4 MCF-10A cells during a 2-hour imaging window (mean ± S.D. of N = 4 independent experiments, 501 M1 cells, 608 M2 cells, 234 M3 cells, and 302 M4 cells). M2 VS M1: Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.0013; M3 VS M1: Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001; M4 VS M1: Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001; M3 VS M2: Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001; M4 VS M3: Unpaired t test, P = 0.0639.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

To directly correlate the excitability of the signaling network with cell oncogenic transformation, we examined MCF-10A cells expressing Hras, Kras or C-MYC oncogenes. These cells have been shown to display features of cell transformation including growth on soft agar (Basolo et al., 1991), epithelial to mesenchymal transition (Liu et al., 2009), and tumor formation in mouse xenografts (Imbalzano et al., 2009). In our hands, similar to PI(4,5)P2 lowering, the transformed cells were larger and more spread (Figure 7D) and showed lower resistance to hypotonic shock (Figure S7B). Expression of LifeAct, PH-AKT, and RBD revealed travelling actin, PIP3, and Ras waves moving across the basal surface of the transformed cells as seen in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 7D, S7C–F; Movie S7). As noted earlier, basal waves within the cell perimeter were rarely detected in the control MCF-10A cells (Figure 7D). Transformed cells displayed a variety of concentric or spiral waves as well as intermittent standing/traveling waves. Some waves initiated at the perimeter with one side of the wave propagating inward and the other pushing the cell edge outwards (Figure S7E). Other waves started interiorly, traveled to the edge, and pushed out. In four experiments, 41.8 +/− 5.9 % (mean +/− SEM) of transformed cells and 5.9 +/− 1.5 % (mean +/− SEM) of control cells displayed these internal waves (Figure 7E). The transformed cell population had more spread cells than control MCF-10A cells; however, both small and large transformed cells displayed more waves and there was only a moderate correlation with cell size (R2=0.4443) (Figure S7G and S7H). Furthermore, compared to control, spontaneous ERK activity increased and showed more frequent oscillations in Ras_G12V transformed cells (Figure 7F and 7G). Since the increase in wave activity suggested that the threshold of the network is lowered, we examined the response of ERK to EGF stimulation of different doses in control and Kras_G12V cells. As shown in Figure S7I, the baseline activity of ERK was higher and the EC50 concentration of EGF needed to trigger responses was lower in the transformed cells. These results are consistent with the lowering of the threshold of signal transduction excitable network in PI(4,5)P2-reduced cells.

We next examined wave activity in a series of cells derived from MCF-10A with increased metastatic potential, designated M1~M4 cells. Whereas M1 and M2 correspond to be wildtype and Ras transformed cells, M3 and M4 cells are selected for higher metastatic index (Dawson et al., 1996; Santner et al., 2001; Weiger et al., 2013). We found wave activities of M1 and M2 were similar to our findings with wildtype and Ras transformed cells. In contrast, M3 and M4 displayed even more internal basal waves than M2 cell (Figure 7H and Movie S7). Up to ~80% of M3 and ~90% of M4 cells displayed waves (Figure 7I). This observation suggested a strong correlation between wave activities on the basal surface of cells and metastatic potential.

Discussion

Our studies provide systems-level mechanisms for migratory transitions and oncogenic transformation in human epithelial cells. We found that, first, these cells display propagating waves of Ras and PI3K activation and that waves reaching the cell perimeter drive protrusions. External stimulation with growth factors can influence the wave behavior. Second, oppositely directed waves merge and display mutual annihilation and responses to growth factor display all-or-none responsiveness and refractory periods. Third, abrupt perturbations of Ras activity and phosphoinositide levels change the number and character of traveling waves and protrusions as well as the sensitivity to growth factor stimulation. These observations show that cellular protrusions are controlled by an excitable Ras/PI3K/ERK network and that growth factors guide cells by locally altering excitability. They also delineate the feedback loops that contribute to excitability. Finally, we discovered that Ras transformation leads to de novo or increased wave activity, consistent with the increased protrusive activity displayed by transformed cells.

Multiple different criteria demonstrated that the downstream effectors of Ras such as ERK and PI3K display properties of excitability in human epithelial cells. First, we repeated the observation that oscillation of ERK activity can be promoted by EGF as previously described in MCF-10A cell (Albeck et al., 2013). Second, there was no production of PIP3 to 30 sec growth factor stimulation while the responses to 1 min and 5 min were quite similar. The responses to 1- and 5-min stimuli continued to increase after the stimuli were removed, suggesting that the system responds in an all-or-none fashion after crossing a threshold. Third, paired stimuli demonstrated the existence of refractory period; cells required about 30 min to regain full responsiveness. The refractory period explains why oppositely directed waves annihilate and the duration of the refractory period is consistent with the period of ERK oscillations.

The studies presented here show that actin waves in epithelial cells are regulated by a mechanism similar to that delineated in Dictyostelium (Vicker et al., 2002; Gerisch et al., 2004; Wozniak et al., 2005; Miao et al., 2017). In Dictyostelium, the slower kinetics of the signal transduction network lead to broad bands of Rap, Ras, and PI3K activity that move coordinately with leading and trailing peaks of F-actin polymerization/depolymerization. This behavior was attributed to the coupling of a slow signaling transduction excitable network (STEN) to a rapid cytoskeletal excitable network (CEN). These characteristics are apparently conserved in human epithelial cells reported here. We found previously reported actin “rosettes” (Marchesin et al., 2015) consisted of a narrow actin band accompanied by broader bands of Ras activation and PIP3. The duration of the responses is about 30 times longer, and the velocity of the waves is about 6-fold smaller, in epithelial versus amoeboid cells. The different kinetics are consistent with the frequency and extension rate of protrusions as well as the speed of movements in the two different cells (Albeck et al., 2013; Aoki et al., 2013; Miao et al., 2019).

We also observed novel wave characteristics that had not been previously reported. First, we observed switching between travelling and standing waves, a recently predicted feature of excitable systems (Bhattacharya, et al, submitted). Second, we found that uniform growth factor triggered a global response, temporarily overwhelming wave activity, and that local gradients provided a directional bias to the waves in MDA-MB-231 cells. Our observations in MDA-MB-231 were closely simulated by manipulating the threshold in the STEN-CEN computational model. In Dictyostelium, the extent to which STEN activity can be biased by external stimuli appears to be context dependent and has been debated (Huang et al., 2013; Gerisch et al., 2016). Our observations provide clear evidence to support the excitable network hypothesis with respect to cell guidance.

Our observations lead to a schematic view of the molecular identity of some of the feedback loops that bring about excitability (see Figure 6L). Ras is activated by EGF and in turn activates ERK. ERK negatively regulates Ras activity. It has been reported that Ras activation reduces PI(4,5)P2 (Van Rheenen et al., 2007). We found PI(4,5)P2 is a negative regulator of Ras activity, which would complete a mutually inhibitory positive feedback loop. PI(3,4)P2 as a product of PI(3,4,5)P3 provides negative feedback to Ras. Finally PI(3,4,5)P3 together with mTORC2 provides a link through AKT to the cytoskeleton. Similar observations were previously made in Dictyostelium except that in amoebae resting PI(3,4)P2 levels are high and AKT can serve as a negative regulator of Ras activation. The consistent role of PI(3,4)P2 as a negative regulator in both systems is surprising since PI(3,4)P2 is at the leading edge of the cell and generally considered as a positive regulator (Bae et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2015). However, our studies (Figure 6E–G, S6A–C) and those in Dictyostelium indicate PI(3,4)P2 at the leading edge lags behind PIP3. Other studies have pointed to additional feedback loops not assessed here. For instance, Ras, PI3K, the actin cytoskeleton and cellular adhesion can form a positive feedback loop (Huang et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2018). Negative feedback involving myosin and AKT, as well as membrane tension and mTORC2 have been reported (Sasaki et al., 2007; Houk et al., 2012; Diz-Muñoz et al., 2016; Riggi et al., 2018).

Excitability of the Ras-PI3K network has important consequences in physiology and cancer. First, the excitable network can generate patterns such as travelling waves of different dimensions or standing waves (Xiong et al., 2010; Bhattacharya, et al, submitted). These patterns can generate a large repertoire of protrusions such as pseudopodia, filopodia, lamellipodia, or invadopodia and consequently explain a wide range of migratory behaviors (Huang et al, 2013; Taniguchi et al, 2013; Miao et al., 2017; Miao et al., 2019). Second, we found in Kras transformed cells, as well as in cells where Ras was acutely activated, an increase in the wave and ERK activity. Furthermore, the increased wave activity was strongly correlated with metastatic potential across a series of increasingly aggressive breast cancer cell lines (M1~M4 MCF10A cells). These suggest that the enhanced wave and ERK activities may control cell proliferation and cancer progression (Roberts et al., 2007; Mebratu et al., 2009; Mendoza et al., 2011; Serra et al., 2011; Samatar et al., 2014; Tanimura et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). Taken together, our studies suggest a novel view of oncogenic transformation as a shift to a lower threshold or set point of the Ras/PI3K/ERK excitable network. This change in threshold is manifested by an increase in stochastic noise driven activities such as the number and the range of propagating waves and the frequency of ERK pulses. The lowering of threshold most likely leads to the increased migration, macropinocytosis, and proliferation of cancer cells and it possibly can be used to assess cancer severity as well as a target for intervention.

STAR Methods text

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Peter N. Devreotes (pnd@jhmi.edu).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact without restriction.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate any unique datasets. The computational simulation codes supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository but are available from the corresponding author on request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

MCF-10A cells, acquired from Iijima Lab (Johns Hopkins University), were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 using DMEM/F-12 medium (Gibco, #10565042) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Gibco, #26050088), 20 ng/ml EGF (Sigma, #E9644), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma, #C-8052), 0.5 mg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma, #H-0888) and 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma #I-1882). MDA-MB-231 cells, acquired from Liu Lab (JHU), were maintained in DMEM medium (Gibco, #10566024) containing 10% FBS (Gibco, #16140071) at 37°C in 5% CO2. M1 (MCF-10A), M2 (MCF-10AT1k.cl2), M3 (MCF-10CA1h), and M4 (MCF-10CA1a.cl1) cells, purchased from the Animal Model and Therapeutic Evaluation Core (AMTEC) of Karmanos Cancer Institute of Wayne State University, were cultured in the same conditions as MCF-10A cells.

METHOD DETAILS

Cell transfection and preparation

Transient transfections of the cells were performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, #L3000008) following manufacturer’s instructions. Stable transfected cell lines were selected and/or maintained in culture media containing drugs (2 ug/ml Puromycin, ThermoFisher, #A1113803 and/or 2 mg/ml Zeocin, ThermoFisher, #R25001). Some stable cell lines were sorted by fluorescence tags.

Cells were transferred to 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (Mattek, #P35G-0.170–14-C) or chambered coverglass (Lab-Tek, #155409PK) and allowed to attach overnight prior to imaging. Cells were seeded and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 overnight before harvest for immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, or live cell imaging.

For EGF stimulation assays, MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells were usually starved in pure DMEM/F-12, or DMEM medium respectively for 24 hours before stimulation.

Plasmids sub-cloning

Constructs of CFP-Lyn-FRB, mCherry-FKBP-Inp54p, mCherry-FKBP-Inp54p (D281A), YFP-FKBP-CDC25, YFP-PH-PLCΔ, and RFP-PH-TAPP1 were obtained from Inoue Lab (JHU). GFP/RFP-PH-AKT, RFP-LifeAct, pFUW2, pMDL, pRSV, and pCMV were obtained from Desiderio Lab (JHU). Raf-RBD (51–220)-GFP was obtained from Balla Lab (NIH). pLenti-GFP-ERKKTR (#59150), mCherry-FKBP-INPP4B (#116864), mCherry-FKBP-INPP4B (C842A) (#116865), pBABE-KrasG12V (#9052), pBABE-C-MYC (#17758), pBABE-HrasG12V (#9051), pUMVC (#8449), pCMV-VSV-G (#8454), psPAX2 (#12260) and pMD2.G (#12259) constructs were obtained from AddGene. Lyn-FRB, FKBP-Inp54p, FKBP-Inp54p (D281A), PH-PLCΔ, PH-AKT, LifeAct, and RBD were subcloned to lenti-viral expression plasmid pFUW2. The pLKO.1 knock-down plasmids scramble shRNA (#1864), Rictor_#1 shRNA (#1853), Rictor_#2 shRNA (#1854), mTOR_#1 shRNA (#1855), and mTOR_#2 shRNA (#1856) were obtained from AddGene.

Drugs preparation

Stocks of 10 mM PP242 (Sigma, #P0037), 25 mM Latrunculin A (Enzo, #BML-T119–0100), 10 mM Ulixertinib (MedChemExpress, #HY-15816), 50 mM LY294002 (Invitrogen, #PHZ1144), 10 mM ZSTK474 (Cell Signaling, #13213), 10 mM Y27632 (Enzo, #ALX-270–333-M001), 25 mM Latrunculin B (Enzo, #BML-T110–0001), 1 mM Jasplakinolide (Enzo, #ALX-350–275-C050) and 10 mM Rapamycin (Cayman, #13346) were prepared by dissolving the chemicals in DMSO. The stocks were diluted to the indicated final concentrations in culture medium or live cell imaging medium. The EGF stock solution was prepared by dissolving EGF (Sigma, #E9644) in 10 mM acetic acid to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. Insulin (Sigma #I-1882) was resuspended at 10 mg/ml in sterile ddH2O containing 1% glacial acetic acid. Hydrocortisone (Sigma #H-0888) was resuspended at 1 mg/ml in 200 proof ethanol. Cholera toxin (Sigma #C-8052) was resuspended at 1 mg/ml in sterile ddH2O and stored at 4°C. All drug stocks except cholera toxin were stored at −20°C.

Virus generation

25 ml of 293T cells were seeded at 6×10^5/ml to 15 cm cell culture dishes on day 1. Conventional calcium phosphate transfection was performed on day 2 to deliver expressing and packaging plasmids into 293T cells. 20 ug pFUW2, 9.375 ug pMDL, 9.375 ug pRSV, 9.375 ug pCMV plasmids (or 10 ug pBABE, 9 ug pUMVC, 1 ug pCMV-VSV-G; or 10 ug pLenti/pLKO.1, 8 ug psPAX2, 2 ug pMD2.G), 250 ul CaCl2 and ddH2O in a total volume of 2.5 ml were mixed with 2.5 ml 2xHEPES (PH=7.05) and incubated for 5 min. The transfection mix was added to the plated cells and shaken gently. Media was changed after 4–6 hours. For virus collection, the medium from infected cells was collected on day 5 and spun at 1000 rpm for 3 min to remove the debris and filtered through 0.45 μm filter followed by ultracentrifugation at 25,000 rpm for 90 min at 4°C in a Beckman ultracentrifuge. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was dissolved in 70 ul PBS overnight at 4°C to obtain concentrated virus, which was stored as 25 ul aliquots at −80°C.

Immunoblotting

Cells were seeded at 4×10^5 per well in 6-well plates with appropriate growth medium and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight, or treated with drugs for indicated period of time before harvesting. Cell lysates were prepared by cell lysis on ice with 3X RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche, #11836170001) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, #P5726). Immunoblotting of individual protein bands was performed by overnight incubating the PVDF membranes with the following primary antibodies (all purchased from Cell Signaling) diluted in 1X Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, #927–50000): rabbit anti-phospho-ERK (#9101), mouse anti-ERK1/2 (#9107), rabbit anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473) (#4060), mouse anti-AKT (#2920), anti-mTor (#2972), anti-Rictor (#2140), anti-GAPDH (#2118) and rabbit anti-β-Actin (#4970). Fluorescent dyes-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (LI-COR, #925–68071 or #925–32210) were used as secondary antibodies to visualize the protein bands with the Odyssey CLx - LI-COR Imaging System.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded on glass bottom imaging dishes or chambers with appropriate growth medium and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight before fixation. 1μM rapamycin was added 1 hour before fixation. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde diluted in warm PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Immunostaining was performed by incubating specimen in appropriate primary antibody in dilution buffer (1X PBS/1% BSA/0.3% Triton X-100) overnight at 4°C and in fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody in dilution buffer for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark after 3 PBS rinses. Cells were covered with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Cell Signaling, #9071) and TIRF imaging was done within 24 hours. Primary antibodies for AKT and p-AKT S473 are described in immunoblotting session. Secondary antibodies are anti-rabbit IgG_Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate (Cell Signaling, #4412) and anti-mouse IgG_Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate (Cell Signaling, #4408). Alexa Fluor® 647 Phalloidin was purchased from Cell Signaling (#8940).

Microscopy

Total internal reflection fluorescence, wide-field epifluorescence, and confocal microscopy have been described previously (Huang et al., 2013). Briefly, epifluorescence and TIRF microscopy experiments were carried out on a Nikon Eclipse TiE microscope illuminated by an Ar laser (GFP) and a diode laser (RFP). Images were acquired by a photometrics Evolve electron Multiplying Charge-Coupled Device camera (EMCCD) camera controlled by Nikon NIS-Elements. Confocal microscopy was carried out on Zeiss AxioObserver inverted microscope with either LSM780-Quasar (34-channel spectral, high-sensitivity gallium arsenide phosphide detectors, GaAsP) or LSM800 confocal module controlled by the Zen software. All live cell imaging was carried out in a temperature/humidity/CO2-regulated chamber.

Computational modeling

The wave simulations were based on excitable system with global and local perturbations. The excitable waves were modeled through reaction-diffusion equations (Xiong et al., 2010). The signal transduction excitable network (STEN) was set up as an activator (X)-inhibitor (Y) system as shown below:

The non-linear term in the first equation contributes to positive feedback while the epsilon (ε) in the second equation creates a delay in the response of the inhibitor. When the activator receives a supra-threshold stochastic input, the autocatalytic feedback leads to a sharp rise in activity, creating the wave front (green in Figure 3G and 3H). The inhibitor, albeit slowly, accumulates to ultimately subdue the activator concentration – creating the wave back (red in Figure 3G and 3H). After the inhibitor subdues the activator response, it then decays back to resting concentration, resulting in a refractory period. When coupled with diffusion across adjacent excitable elements, this creates a propagating wave.

Simulations were done using a two-dimensional 200×200 array in MATLAB, using stochastic differential equations (Picchini, 2007). The term UN incorporates the stochastic input to the system which is modeled as a zero-mean Gaussian white noise process (σ). The parameter values used are: a1 = 0.167, a2 = 16.67, a3 = 167, a4 = 1.2, a5 = 1.47, ε = 0.12, c1 = 39, DX = 2.2, and DY = 1.2.

External stimulus to the excitable system is provided through the term Sin in the activator equation. In the absence of a stimulus, this term was set to zero. For a global stimulus, the term was set to 0.2 for the whole 200×200 system. For a gradient simulation, a gaussian profile was used for Sin, with mean at the bottom edge of the spatial array, and a standard deviation of 60 – with the amplitude rising from 0 to 0.5.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Imaging quantifications

Cell area quantification

Single cells were first manually tracked and cropped out from a pool of cells in the movies, and converted into binary images using normal ImageJ procedures (despeckle, threshold, and fill-holes). The relative value of cell area for each frame of the movie was obtained basing on the processed binary images.

Wave quantification

First, we only quantified the waves which initiate and travel in the internal region of the cell basal surface. We did not define the protrusion events seen in cells as our travelling waves, thus we did not count protrusion events for our wave quantification. Second, we quantified travelling but not standing waves. Third, the duration of wave was defined as the lifetime of the wave from its appearance to its disappearance. When a wave splits, the clock keeps going until the longest lasting portion disappears. When a wave merges with another one, the time of the origin of that wave to the disappearance of the merged wave is counted as its duration. The (maximum) width is the maximum length of the lateral span of a wave during its lifetime. The velocity is the average velocity of all parts of a specific wave.

Lamellipodia kymograph

In Figure 4B, the lamellipod was defined as the higher intensity of signal of FKBP channel after rapamycin-induced recruitment. This signal was much lower in the cytosol region, because lamellipodia has two layers of membrane where FKBP has been recruited. For frames before the addition of rapamycin, the profile of the ring in the first frame after the recruitment is used since the cell shape has not changed before the recruitment. A line perpendicular to the tangent of the cytosol boundary is drawn at each angle from 0 to 360 degree. The length of lamellipodia at each angle is measured along this line. The kymograph was generated by aligning these values versus time.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7 software was used for all statistical analyses. All quantifications are displayed as mean ± SD or SEM. Two-tailed P-values were calculated using parametric t test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Further details of statistical parameters and methods are reported in the corresponding figure legends.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

No additional resources.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1. (Related to Figure 1) Signaling and cytoskeletal activities propagate as waves in the MDA-MB-231 cell

PH-AKT, LifeAct, and/or DIC channels are shown. Time unit is hh:mm:ss, and cells were kept in phenol-red free culture medium at 37°C, 5% CO2 during the live cell imaging. (The same time stamp and imaging conditions are used for the later movies unless specified. Scale bars are indicated.)

Movie S2. (Related to Figure 2) Colliding actin waves annihilate

Cell #1 is the MDA-MB-231 cell, and cell #2 is Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cell. LifeAct channel is shown for both cells. Stars indicate when and where the annihilation events happen.

Movie S3. (Related to Figure 3) Response of PIP3 and/or actin waves to global and local EGF stimuli in the MDA-MB-231 cell

Cells were starved in DMEM medium for 2 hours before imaging and kept in DMEM medium during imaging. One cell expressed with PH-AKT and LifeAct is shown for global stimulation. Global EGF stimulus was added at 02:12:00 to a final concentration of 2 ng/ml. Three representative MDA-MB-231 cells expressed with PH-AKT show responses of PIP3 waves to local EGF stimulus. Time is showed at the upper left corner of each cell. Star indicates when and where the local stimulus was applied.

Movie S4. (Related to Figure 3) Computational simulation of waves in response to global and local stimuli

Simulation of waves was based on activator-inhibitor model. Green is activator while red is inhibitor. Global stimulus was added at time 85 (a.u.). “N” indicates when and where the local stimulus was added.

Movie S5. (Related to Figure 4) Cell spreading and signaling activities are increased when PI(4,5)P2 is lowered in MCF-10A cells

All cells were expressed with Lyn-FRB, FKBP-Inp54p and/or biosensor (RBD or ERK-KTR). FKBP-Inp54p and DIC channels are shown for the cell which starts oscillatory spreading after rapamycin addition at 00:13:30. Lyn-FRB and RBD channels are shown for the cell which has enriched Ras activity at the oscillatory protrusions caused by PI(4,5)P2 lowering (1 μM rapamycin was added 10 min before the start of the movie for this cell). FKBP-Inp54p and ERK-KTR channels are shown for the cells which show increased ERK activity after rapamycin addition at 00:30:48).

Movie S6. (Related to Figure 4) Increased PIP3 or Ras wave formation in the MDA-MB-231 cell after PI(4,5)P2 lowering

The MDA-MB-231 cells were expressed with Lyn-FRB, FKBP-Inp54p and biosensor (PH-AKT or RBD). 1 μM rapamycin was added at 01:20:10 for the cell with PH-AKT, while 1 μM rapamycin was added at 01:25:20 for the cell with RBD.

Movie S7. (Related to Figure 7) Wave activity was increased in Ras-GEF recruited MDA-MB-231 cell, in Kras transformed MCF-10A cell, and in M2-M4 cancer cell lines.

For the Ras-GEF recruited MDA-MB-231 cell, Lyn-FRB, FKBP-CDC25 and PH-AKT (channel shown) were expressed and 1 μM rapamycin was added at 01:12:00. For the control and Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cells, LifeAct and/or PH-AKT channels are shown. For M1~M4 MCF-10A cells, LifeAct channel is shown.

Figure S1. (Related to Figure 2 and Figure 4) Cell response to EGF stimuli and recruitment of Inp54p by chemically-induced dimerization

(A) One example of individual cell response of Figure 2I. Two 1 min EGF stimuli were added at 28 min and 78 min (T = 50 min). The response of PIP3 production of MCF-10A cell was shown in blue and the smoothed line was marked in pink.

(B and C) MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB, FKBP-Inp54p, and PH-PLCΔ was exposed to 1μM rapamycin. Images of single cell before and after the stimulation show diffusion of PH-PLCΔ from membrane to cytosol.

(D) The Inp54p inactive version (D281A) did not cause PI(4,5)P2 reduction.

Scale bar labeled on images is 20 μm.

Figure S2. (Related to Figure 4) Low degree of PI(4,5)P2 reduction leads to cell spreading while high degree of PI(4,5)P2 reduction leads to cell shrinking

(A) Response to 1μM rapamycin (added at 0 min) of a population of MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB and various levels of FKBP-Inp54p (channel shown).

(B) Quantification of cytosolic Inp54p intensity in shrinking or spreading cells. Cells with at least a 50% decrease in cell area are defined as shrinking while those with at least a 50% increase are defined as spreading (mean ± S.D. of N = 19 cells of 5 experiments). Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P<0.0001.

(C) Different responses of single cell expressing Lyn-FRB, PH-PLCΔ, and high FKBP-Inp54p to low (5nM) and subsequently high (1 μM) rapamycin at 20 and 70 min, respectively.

(D) Quantification of cell area and cytosolic intensity of PH-PLCΔ, FKBP-Inp54p, and Lyn-FRB in (C) (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 14 cells of 4 experiments).

(E) MCF-10A cells were sorted into two groups (high Lyn-FRB/high FKBP-Inp54p and high Lyn-FRB/low FKBP-Inp54p) and cells responded uniformly in each group to 1μM rapamycin. The fluorescence intensity (FI) of low FKBP-Inp54p group was multiplied by 3.

(F) Quantification of cell area change in (E) (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 24 cells for low FKBP-Inp54p, 15 cells for low FKBP-Inp54p_D281A, 32 cells for high FKBP-Inp54p and 14 cells for high FKBP-Inp54p_D281A of 5 experiments).

The thin, colored lines represent the individual low Inp54p cells.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Figure S3. (Related to Figure 4) PI(4,5)P2 lowering activates PI3K and mTORC2

(A) Lyn-FRB channel of cell in Figure 4C.

(B) Left panel: representative images of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB (channel shown), FKBP-Inp54p, and PH-AKT (channel shown) after 1μM rapamycin. Right panel: quantification of the yellow boxes scan.

(C) Left panel: representative immunofluorescence staining images captured on TIRF of MCF-10A cell expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Inp54p after 1μM rapamycin. Right panel: quantification of the yellow boxes scan.

(D) Internal and external views of stacked frames of ROI (dashed red box) of the cell in Figure 4J. The scale bar of time is 1 hour.

(E) MDA-MB-231 cells expressing Lyn-FRB, PH-AKT and different levels of FKBP-Inp54p (channel shown) before and after 1μM rapamycin. The fluorescence intensity (FI) of low FKBP-Inp54p cell was multiplied by 8.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Figure S4. (Related to Figure 4) PIP3 is still activated by PI(4,5)P2 lowering when cytoskeletal activity is inhibited, and inhibition of PIP3 reduces the wave and protrusion activities in MDA-MB-231 cells

(A) MDA-MB-231 Cell was expressed with Lyn-FRB, INP54P-FKBP, and PH-AKT (channel showed). Cell was pretreated with JLY (10 μM Y27632 was firstly added to cells, and 5 μM Latrunculin B and 8 μM Jasplakinolide were added 10 min later) 1 hour before imaging. 1 μM rapamycin was added at 0 min.

(B) Quantification of the yellow boxes scan in (A).

(C) Experimental setting was same to (A).

(D) Left graph is the quantification of the yellow boxes scan in (C), and right graph is the quantification of the orange boxes scan in (C).

(E) Time-lapse confocal images of MDA-MB-231 cell expressing PH-AKT to show the signaling of PIP3 at the bottom surface of the living cell. 10 μM PI3K inhibitor ZSTK474 was added at 0 min.

(F) Quantification of wave number change in (E). Individual waves were followed from origin to end in videos. The total wave number for each cell was quantified during 55 min imaging windows before and after ZSTK474 (mean ± S.D. of N = 16 cells of 4 experiments). Paired t test, P = 0.001.

(G) Quantification of mean PIP3 intensity at the ventral surface of cells in (E). The PIP3 value on the left column is the average of all frames before the addition of ZSTK474 during the 65 min imaging window, while the PIP3 value on the right column is the average of all frames after the addition of ZSTK474 during the following 55 min imaging window (mean ± S.D. of N = 10 cells of 3 experiments). Paired t test, P < 0.0001.

(H) Quantification of the dynamic change of the mean PIP3 intensity at the ventral surface of cells in (E). ZSTK474 was added at 65 min. The bold dark blue line is the average while the two light blue lines are the mean ± S.D. of N = 10 cells of 3 experiments.

(I) Quantification of the dynamic change of the size of cells in (E). ZSTK474 was added at 65 min. The bold dark orange line is the average while the two light orange lines are the mean ± S.D. of N = 10 cells of 3 experiments.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Figure S5. (Related to Figure 6) mTORC2 activity is required for the MCF-10A cell spreading caused by PI(4,5)P2 lowering

(A) Western-blot indicated the activity of mTORC2 was inhibited by PP242.

(B) Time-lapse confocal images of MDA-MB-231 cell expressing PH-AKT to show the signaling of PIP3 at the bottom surface of the living cell. 10 μM mTOR inhibitor PP242 was added at 0 min.

(C and D) Confocal images of MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Inp54p (channel shown) pre-treated with DMSO (C) or 10 μM mTOR inhibitor PP242 (D) before and after rapamycin.

(E and F) Western-blot indicated the expression levels of mTOR or Rictor were lowered by their shRNAs respectively. Control was the scrambled shRNA.

(G-I) Confocal images of MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB and FKBP-Inp54p (channel shown) transfected with scrambled (G), mTOR (H), or Rictor (I) shRNAs before and after rapamycin.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Figure S6. (Related to Figure 6) PI(3,4)P2 is a negative regulator of the excitable network

(A) Confocal images of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing PH-TAPP1-GFP and PH-AKT-RFP.

(B) Merged images of both fluorescence channels in (A). Green is PH-TAPP1 and red is PH-AKT.

(C) Quantification of the box scan in (B).

(D) Quantification of the area changes of individual MCF-10A cells (colored lines) or population verage (black line, mean ± S.E.M. of N = 24 cells of 3 experiments) before and after rapamycin. Cells were expressed with Lyn-FRB and FKBP-INPP4B(C842A) (an inactive form).

(E) Quantification of the yellow boxes scan of images shown in Figure 6K.

(F) Quantification of changes of average fluorescence intensity of RBD (red line) and Lyn (blue line) at the ventral surface of MCF-10A cells before and after rapamycin-induced PI(3,4)P2 reduction (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 11 cells of 3 experiments). 1 μM rapamycin was added at 100 min.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

Figure S7. (Related to Figure 7) Oncogenic transformation causes higher sensitivity to hypotonic shock and enhanced excitability of the signal transduction network

(A) DIC images showed more cell death with PI(4,5)P2 lowered when given hypotonic shock. For hypotonic shock, MCF-10A cells were incubated in 1 volume hypotonic buffer (ddH2O + 1 mM MgCl2 + 1.2 mM CaCl2) : 4 volume growth media for 24 hours before imaging. DMSO or 1μM rapamycin were given 2 hours before hypotonic shock.

(B) DIC images showed hypotonic shock caused more cell death in Ras_G12V or/and C-MYC transformed MCF-10A cells.

(C) Time-lapse confocal images of Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cells expressing Lyn-FRB-CFP, RBD-GFP and LifeAct-RFP.

(D) Quantification of the boxes scan in (C).

(E) Time-lapse confocal images of Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cell expressing LifeAct and PH-AKT (both channels shown). Additional examples in Movie S7.

(F) Time-lapse confocal images of Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cell expressing LifeAct and PH-AKT (both channels shown). Star indicates standing wave and arrow indicates traveling wave. Additional examples in Movie S7.

(G) Wave number (y-axis) in each individual cell was plotted by cell area (x-axis) during a 2 hour imaging window of control (green circles) and Kras_G12V transformed (pink circles) MCF-10A cells (N = 28 control and 61 transformed cells of 4 experiments). The linear regression line is shown for transformed cells.

(H) Quantification of cell area and wave number per cell in control and Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cells (mean ± S.E.M. of N = 28 control and 61 transformed cells of 4 experiments). Unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.0166 for area and < 0.0001 for wave number.

(I) Western Blot to show the shifted dose response of ERK to EGF stimulation in Kras_G12V transformed MCF-10A cells. Cells were starved in pure DMEM/F-12 medium for 24 hours before EGF stimulation.

The unit of time labeled on images is min and scale bar is 20 μm.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-phospho-ERK | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9101 |

| Mouse anti-ERK1/2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9107 |

| Rabbit anti-phospho-AKT (Ser473) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4060 |

| Mouse anti-AKT | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2920 |

| Anti-mTor | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2972 |

| Anti-Rictor | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2140 |

| Anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2118 |

| Rabbit anti-β-Actin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4970 |

| Fluorescent dyes-conjugated goat anti-rabbit | LI-COR | Cat#925–68071 |

| Fluorescent dyes-conjugated goat anti-mouse | LI-COR | Cat#925–32210 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG_Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4412 |

| Anti-mouse IgG_Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4408 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| DMEM/F-12 medium | Gibco | Cat#10565042 |

| Horse serum | Gibco | Cat#26050088 |

| EGF | Sigma | Cat#E9644 |

| Cholera toxin | Sigma | Cat#C-8052 |

| Hydrocortisone | Sigma | Cat#H-0888 |

| Insulin | Sigma | Cat#I-1882 |

| DMEM medium | Gibco | Cat#10566024 |

| FBS | Gibco | Cat#16140071 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Invitrogen | Cat#L3000008 |

| Puromycin | ThermoFisher | Cat#A1113803 |

| Zeocin | ThermoFisher | Cat#R25001 |

| PP242 | Sigma | Cat#P0037 |

| Latrunculin A | Enzo | Cat#BML-T119–0100 |

| Ulixertinib | MedChemExpress | Cat#HY-15816 |

| LY294002 | Invitrogen | Cat#PHZ1144 |

| ZSTK474 | Cell Signaling | Cat#13213 |

| Y27632 | Enzo | Cat#ALX-270–333-M001 |

| Latrunculin B | Enzo | Cat#BML-T110–0001 |

| Jasplakinolide | Enzo | Cat#ALX-350–275-C050 |

| Rapamycin | Cayman | Cat#13346 |

| Protease inhibitors | Roche | Cat#11836170001 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail | Sigma | Cat#P5726 |

| Odyssey Blocking Buffer | LI-COR | Cat#927–50000 |

| Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9071 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 Phalloidin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#8940 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| MCF-10A | M. Iijima Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| MDA-MB-231 | J. Liu Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| M1 (MCF-10A) | Animal Model and Therapeutic Evaluation Core (AMTEC) of Karmanos Cancer Institute of Wayne State University | N/A |

| M2 (MCF-10AT1k.cl2) | Same as above | N/A |

| M3 (MCF-10CA1h) | Same as above | N/A |

| M4 (MCF-10CA1a.cl1) | Same as above | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pFUW2-CFP-Lyn-FRB | This study | N/A |

| pFUW2-mCherry-FKBP-Inp54p | This study | N/A |

| pFUW2-mCherry-FKBP-Inp54p (D281A) | This study | N/A |

| pFUW2-YFP-PH-PLCΔ | This study | N/A |

| pFUW2-GFP-PH-AKT | This study | N/A |

| pFUW2-RFP-PH-AKT | This study | N/A |

| pFUW2-RFP-LifeAct | Lab stock | N/A |

| pFUW2-Raf-RBD (51–220)-GFP | Lab stock | N/A |

| YFP-FKBP-CDC25 | T. Inoue Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| RFP-PH-TAPP1 | T. Inoue Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| pFUW2 | S. Desiderio Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| pMDL | S. Desiderio Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| pRSV | S. Desiderio Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| pCMV | S. Desiderio Lab (JHU) | N/A |

| pLenti-GFP-ERKKTR | Regot et al., 2014 | Addgene Plasmid #59150 |

| mCherry-FKBP-INPP4B | Goulden et al., 2019 | Addgene Plasmid #116864 |

| mCherry-FKBP-INPP4B (C842A) | Goulden et al., 2019 | Addgene Plasmid #116865 |

| pBABE-KrasG12V | William Hahn Lab (Dana-Farber) (unpublished) | Addgene Plasmid #9052 |

| pBABE-HrasG12V | William Hahn Lab (Dana-Farber) (unpublished) | Addgene Plasmid #9051 |

| pBABE-C-MYC | Dai et al., 2007 | Addgene Plasmid #17758 |

| pUMVC | Stewart, et al., 2003 | Addgene Plasmid #8449 |

| pCMV-VSV-G | Stewart, et al., 2003 | Addgene Plasmid #8454 |

| psPAX2 | Didier Trono Lab (EPFL) (unpublished) | Addgene Plasmid #12260 |

| pMD2.G | Didier Trono Lab (EPFL) (unpublished) | Addgene Plasmid #12259 |

| pLKO.1 scramble shRNA | Sarbassov et al., 2005 | Addgene Plasmid #1864 |

| pLKO.1 Rictor_#1 shRNA | Sarbassov et al., 2005 | Addgene Plasmid #1853 |

| pLKO.1 Rictor_#2 shRNA | Sarbassov et al., 2005 | Addgene Plasmid #1854 |

| pLKO.1 mTOR_#1 shRNA | Sarbassov et al., 2005 | Addgene Plasmid #1855 |

| pLKO.1 mTOR_#2 shRNA | Sarbassov et al., 2005 | Addgene Plasmid #1856 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Fiji (ImageJ) | http://imagej.nih.gov/ij | Ver 1.52n |

| MATLB | https://mathworks.com | Ver R2017a |

| Graphpad Prism | https://graphpad.com | Ver 7.00 |

| Other | ||

| 35 mm glass-bottom dishes | Mattek | Cat#P35G-0.170–14-C |

| Chambered coverglass | Lab-Tek | Cat#155409PK |

Highlights.

The Ras/PI3K/ERK network displays features of excitable systems in epithelial cells

Network perturbations can increase the wave activity and the frequency of ERK pulses

Wave activity is increased in transformed cells and increasingly metastatic cancer cells

Cancer progression is a shift to a lower threshold of the excitable signaling network

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the Devreotes and Iglesias laboratories as well as members of the Robinson and Iijima laboratories (Johns Hopkins University) and Dr. C. Janetopoulos (University of the Sciences) for helpful suggestions. We thank Dr. S. Schmidt of Losert laboratory (University of Maryland) for writing the MatLab script for analysis of ERK-KTR changes. We thank Inoue (JHU), Desiderio (JHU) and Balla (NIH) laboratories and Addgene for generous provision of plasmids. We thank D. Biswas of Iglesias laboratory and K. Tian (University for the Creative Arts) for helping the graphical abstract. This work was supported by NIH grant R35 GM118177 (to P.N.D.), AFOSR MURI FA95501610052 (to P.N.D.), DARPA HR0011-16-C-0139 (to P.N.D. and P.A.I.), K22CA212060 (to C.H.H.), a Cervical Cancer SPORE P50CA098252 Career Development and Pilot Project Awards (to C.H.H.), R01GM136711 (to C.H.H.), W. W. Smith Cancer Research Grant (to C.H.H.), NIH Grant S10 OD016374 (to S. Kuo of the JHU Microscope Facility), Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology 2016YFA0500202 and National Natural Science Foundation of China 31770894 (to H.C.).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Albeck JG, Mills GB, and Brugge JS (2013). Frequency-modulated pulses of ERK activity transmit quantitative proliferation signals. Mol. Cell 49, 249–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K, Kumagai Y, Sakurai A, Komatsu N, Fujita Y, Shionyu C, and Matsuda M (2013). Stochastic ERK activation induced by noise and cell-to-cell propagation regulates cell density-dependent proliferation. Mol. Cell 52, 529–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y, Shibata T, Matsuoka S, Sato MJ, Yanagida T, and Ueda M (2010). Self-organization of the phosphatidylinositol lipids signaling system for random cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 12399–12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YH, Ding Z, Das T, Wells A, Gertler F, and Roy P (2010). Profilin1 regulates PI (3, 4) P2 and lamellipodin accumulation at the leading edge thus influencing motility of MDA-MB-231 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 21547–21552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart EL, Allard J, Lou SS, Theriot JA, and Mogilner A (2017). Adhesion-Dependent Wave Generation in Crawling Cells. Curr. Biol 27, 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basolo F, Elliott J, Tait L, Chen XQ, Maloney T, Russo IH, Pauley R, Momiki S, Caamano J, Klein-Szanto AJP, et al. (1991). Transformation of human breast epithelial cells by c-Ha-ras oncogene. Mol. Carcinog 4, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bement WM, Leda M, Moe AM, Kita AM, Larson ME, Golding AE, Pfeuti C, Su K-C, Miller AL, Goryachev AB, et al. (2015). Activator-inhibitor coupling between Rho signalling and actin assembly makes the cell cortex an excitable medium. Nat. Cell Biol 17, 1471–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case LB, and Waterman CM (2011). Adhesive F-actin waves: a novel integrin-mediated adhesion complex coupled to ventral actin polymerization. PLoS One 6, e26631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, and Lindquist S (2007). Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell 130, 1005–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PJ, Wolman SR, Tait L, Heppner GH, and Miller FR (1996). MCF10AT: a model for the evolution of cancer from proliferative breast disease. Am. J. Pathol. 148, 313–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diz-Muñoz A, Thurley K, Chintamen S, Altschuler SJ, Wu LF, Fletcher DA, and Weiner OD (2016). Membrane Tension Acts Through PLD2 and mTORC2 to Limit Actin Network Assembly During Neutrophil Migration. PLOS Biology 14, e1002474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch G, Bretschneider T, Müller-Taubenberger A, Simmeth E, Ecke M, Diez S, and Anderson K (2004). Mobile actin clusters and traveling waves in cells recovering from actin depolymerization. Biophys. J 87, 3493–3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch G, and Ecke M (2016). Wave Patterns in Cell Membrane and Actin Cortex Uncoupled from Chemotactic Signals. Methods Mol. Biol 1407, 79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]