Abstract

Frailty is increasingly recognized as a better predictor of adverse postoperative events than chronological age. The objective of this review was to systematically evaluate the effect of frailty on postoperative morbidity and mortality. Studies were included if patients underwent non-cardiac surgery and if frailty was measured by a validated instrument using physical, cognitive and functional domains. A systematic search was performed using EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, CENTRAL and PubMed from 1990 - 2017. Methodological quality was assessed using an assessment tool for prognosis studies. Outcomes were 30-day mortality and complications, one-year mortality, postoperative delirium and discharge location. Meta-analyses using random effect models were performed and presented as pooled risk ratios with confidence intervals and prediction intervals. We included 56 studies involving 1.106.653 patients. Eleven frailty assessment tools were used. Frailty increases risk of 30-day mortality (31 studies, 673.387 patients, risk ratio 3.71 [95% CI 2.89-4.77] (PI 1.38-9.97; I2=95%) and 30-day complications (37 studies, 627.991 patients, RR 2.39 [95% CI 2.02-2.83). Risk of 1-year mortality was threefold higher (six studies, 341.769 patients, RR 3.40 [95% CI 2.42-4.77]). Four studies (N=438) reported on postoperative delirium. Meta-analysis showed a significant increased risk (RR 2.13 [95% CI 1.23-3.67). Finally, frail patients had a higher risk of institutionalization (10 studies, RR 2.30 [95% CI 1.81- 2.92]). Frailty is strongly associated with risk of postoperative complications, delirium, institutionalization and mortality. Preoperative assessment of frailty can be used as a tool for patients and doctors to decide who benefits from surgery and who doesn’t.

Keywords: frailty, surgery, outcome, older patients, non-cardiac surgery

Life expectancy has increased with the focus on the quality of added life-years [1]. This prolonged life expectancy has created an increased demand for surgical care of the elderly [2, 3].

Several studies have described age as an independent risk factor for postoperative morbidity and mortality in both cardiac and non-cardiac surgery [4-7]. Advantages in operative techniques and perioperative management seem to improve outcome and multiple studies have even demonstrated an improved quality of life and enhancement of functional status after cardiac surgery in octogenarians [8-10]. Despite these improvements in perioperative care, postoperative adverse effects still remain more common in older patients when compared to the younger ones [5, 11]. Adequate risk assessment integrates surgical factors and factors that describe the biological status of the patient, rather than age alone, as age per se seems to be responsible for only a small increase in adverse events [3, 12].

Recently the concept of frailty has come into view [2]. Frailty can be defined as a clinically recognizable state of increased vulnerability resulting from aging-associated lack of physiological reserve and decline in function across multiple physiologic systems [13]. Focus on and optimization of frail patients can contribute to a reduced postoperative morbidity and thereby to better outcome in the older surgical population [2]. Globally, the World Health Organisation has recently developed recommendations on integrated care for older patients in order to maintain their physical and cognitive functions [14].

In order to adequately inform our patients of significant perioperative risks, additional information on frailty as a risk factor influencing postoperative outcome is essential. During the preoperative assessment, this information can guide the clinician in shared decision making on whether the older patient benefits from surgery or not. The aim of this study was to evaluate the predictive role of frailty on postoperative outcomes after non-cardiac surgery by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature.

METHODS

Search Strategy

A search of literature was performed and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and MOOSE criteria [15]. The objective was to find all studies on frail patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery, correlating their age and its subsequent risk factors to postoperative morbidity and mortality. The systematic Internet based search was performed using EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and PubMed. Full electronic searches can be found in Supplementary Table. 1. In addition, we screened the reference section of all articles included in this review. The search was limited to original articles, human subjects and articles published from January 1990 - December 2017.

Publication selection

Two reviewers independently (EKMT and JMKvF) screened potentially relevant articles from the initial search, first by title and abstract and later on by full text. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third reviewer (SH). Studies were found eligible for inclusion if their subjects underwent non-cardiac surgery and if frailty was measured by a frailty instrument using at least physical, cognitive and functional domains. Also, the relationship between frailty and primary outcomes of 30-day mortality, or 30-day complications should be evaluated, with stratification of the outcome (frail versus non-frail). Studies were excluded if they were review articles, case reports, editorials or comments, or if full text was not available. Duplicate articles were removed during the initial search.

Data Extraction

The following data were gathered from eligible publications: publication date, study design, sample size, type of surgery, proportion of females, mean age, the frailty score and outcome. Outcome was measured by the following adverse events: 30-day mortality, 30-day complications, one-year mortality, manifestation of postoperative delirium (POD) and discharge to a specialized facility. 30-day complications are generally defined as suggested by the Clavien-Dindo classification system[16]; otherwise the authors should have predefined this outcome. Postoperative delirium was defined as a temporary state of confusion and diagnosis made with validated delirium screening tools or by a geriatric expert team [17]. Discharge destination was defined as “home”, or “not able to return home”. Furthermore, surgical procedures were categorised according to the ESC/ESA Guidelines [18] and divided into low-, intermediate- and high-risk procedures. Occasionally, the surgical risk category was documented as “mixed surgical population”. A subanalysis per surgery type was performed to better understand the effect of frailty according to the surgical risk category. Where absolute data were not presented in table or text and authors could not be reached, when possible, data were extracted from figures using WebPlotDigitizer (version, 2.6.8).

Assessment of quality and possible biases

Two reviewers performed assessment of quality. In case of disagreement a third reviewer was consulted. The quality assessment tool for prognosis studies as proposed by Hayden et al. was used for the appraisal of all included studies [19]. This tool focuses on six areas of potential bias; first study participation (i.e. the study sample represents the population of interest on key characteristics), second study attrition (i.e. whether the study was able to obtain a complete follow up), third prognostic factor measurement (i.e. a clear definition or description of the prognostic factor measured is provided), fourth outcome measurement(i.e. a clear definition of the outcome of interest), fifth confounding measurement and account (i.e. important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for) and sixth analysis(i.e. the statistical analysis is appropriate for the design of the study). After the evaluation of these six areas of potential bias, all studies were subsequently divided According to the Quality in Prognosis Study Tool into good (11 or 12 points), fair (9 or 10 points) and poor (< 9 points) quality.

Statistical methods

Numerical values reported by the studies were used for analysis. In some cases, further calculation was required for ascertaining outcomes. In the studies using the modified frailty index (mFI) patients were categorized into two groups: “not frail” (mFI < 0.27), or “frail” (mFI ≥ 0.27). The decision to divide patients into those categories was based on thresholds most commonly used to indicate the presence of frailty and was made before analysis. In the remaining studies, using ten different frailty instruments, outcome was also dichotomized according to predefined criteria as “not frail” or “frail”. Random effects models for meta-analysis were used because of the large expected heterogeneity in determinant and other study characteristics. The primary outcome measures 30-day mortality and 30-day complications were stratified by frailty score. Furthermore, a subanalysis per surgery type was performed to better understand the effect of frailty according to the surgical risk category. Effect estimates are presented as pooled risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI’s). Robust meta-analytic conclusions of prognosis studies will be more appropriately signaled when prediction intervals are provided [20]. Thus, to further account for between-study heterogeneity, 95% prediction interval (PI) were also estimated, which evaluates the uncertainty of the effect that would be expected in a new study addressing the same association [21]. I2 statistic was calculated, which is the percentage of variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than random error. Since all reported outcomes were adverse events, a positive relative risk indicates that frailty is associated with worse patient outcome. A meta-regression analysis was carried out to assess the influence of the patient’s mean age (using mean or median age of the study populations as a proxy) on 30-day mortality. Finally, an additional sensitivity analysis was performed (excluding studies using ACS-NSQIP database) to circumvent the issue of possible duplicate cases and demonstrate the effect of frailty on postoperative outcome.

Data gathering and data analysis was performed using Excel (version 14.7.2) and Rstudio (version 1.1.463) respectively.

RESULTS

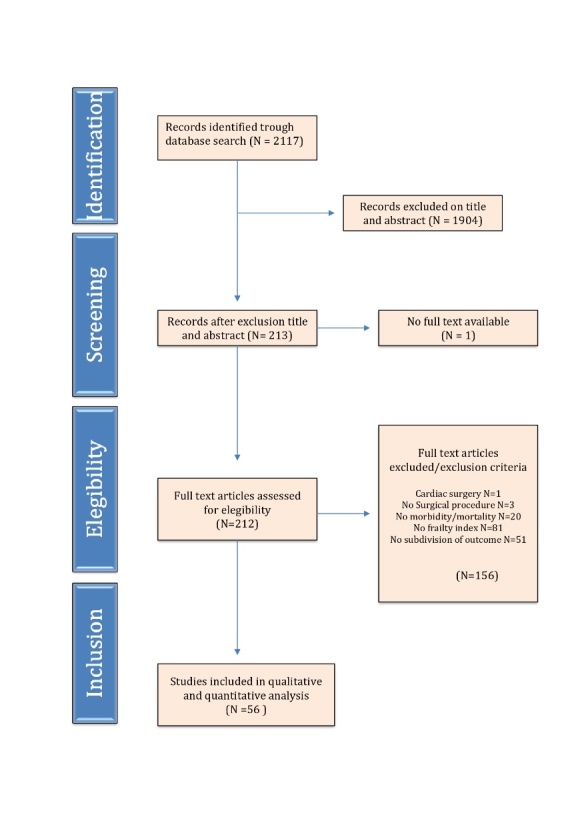

Initial literature search identified 2117 manuscripts as potentially relevant. Of these, 1904 were excluded due to unrelated research questions or study type. Full text was not available in one study; therefore 212 full text articles were thoroughly screened for eligibility. A total of 56 studies were found suitable for this systematic review. Figure 1 shows the search strategy flow chart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for study selection. This flowchart depicts the flow of information trough different phases of the systematic research.

Frailty assessment tools

A total of eleven different frailty assessment tools were used. The majority of studies (twenty-four) used the Modified Frailty Index (mFI), created by Saxton and Velanovich [22]. The mFI consists of eleven variables present in the Canadian Study on Health and Aging Frailty Index, as well as in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) dataset [23, 24]. Variations on the Fried Frailty Criteria [25] were used in eleven studies, where frailty was defined by identifying unintentional weight loss, exhaustion, low energy expenditure, low grip strength and slow walking speed. Frailty assessment tools were often based on comprehensive geriatric assessments, which can be derived from questionnaires or patient files, including the Frailty Index and the Groningen Frailty Indicator. Supplementary Fig. 2 provides a detailed description of all frailty assessment tools used in this review.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the included studies is provided in Supplementary Fig. 3 and table 1 provides a summary of our appraisal. Study participation was adequately described in 37 studies. The study attrition - referring to the response rate and attempts to collect information on patients who were lost to follow up - was adequately defined in 40 studies. Prognostic factors were clearly defined or described in most studies (86%). Ninety-one percent of studies provided a clear definition of the outcome of interest. When summarizing, 95% of all studies included were of at least fair quality, with more than half assessed as good quality.

Postoperative outcome predicted by frailty

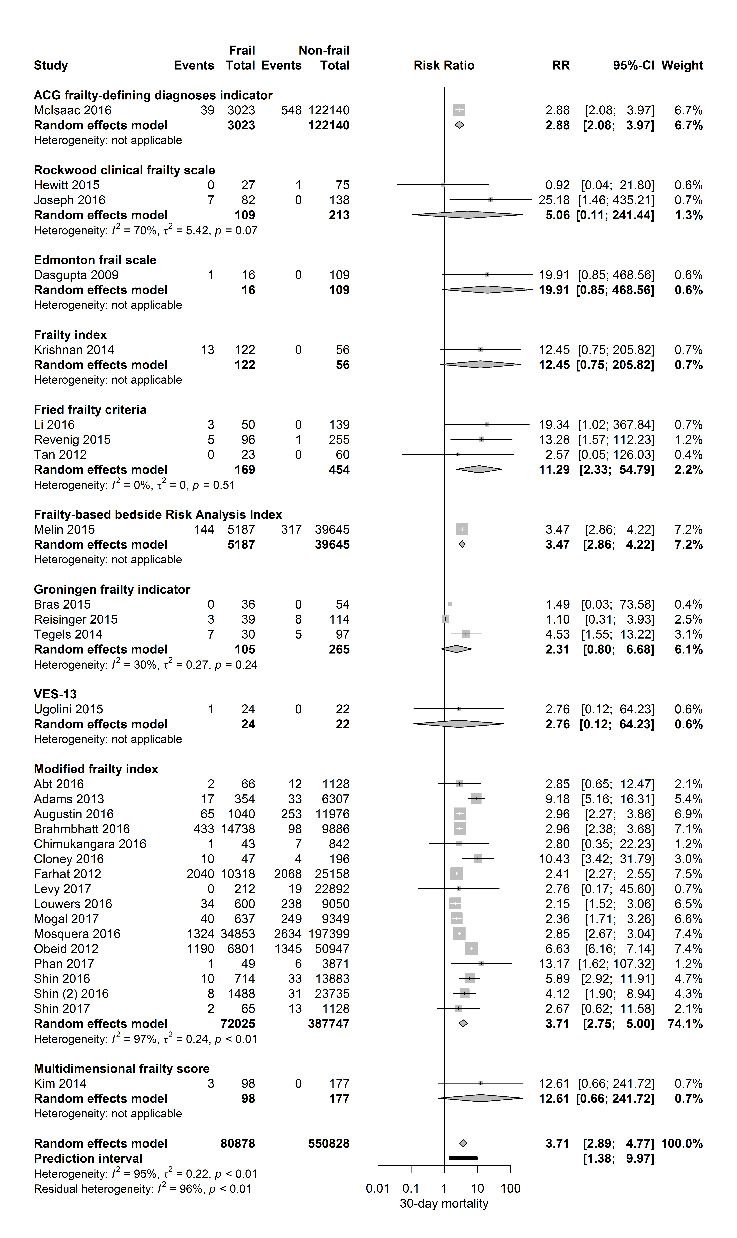

Table 1 shows the details of study demographics and methods of frailty measurement. In the selected studies, fifty-one were of prospective design and sample size ranged from 37 - 232 352 patients. Gender distribution was reported in 93% of the studies with a proportion of females ranging from 0% in the study of Levy et al, describing a male population undergoing robot assisted radical prostatectomies, until 100% in the study of Courtney-Brooks et al, describing complications in elderly women undergoing gynecologic oncology surgery. Twenty-seven studies investigated the effect of frailty in oncological surgery (predominantly abdominal cancer surgery), four studies in vascular surgery, nine in orthopedic surgery, eleven in elective general surgery (predominantly intermediate - and high-risk surgery), four in emergency surgery and one study in transplant surgery. Thirty-one studies investigated the influence of frailty on 30-day mortality. Figure 2 shows a forest plot of this primary outcome with a pooled RR of 3.71 [95% CI 2.89-4.77] (PI 1.38-9.97; I2=95%) for frail patients compared to those who were not frail. The 95% prediction interval also showed exclusion of the null value.

Table 1.

Study demographics and method of determining frailty.

| Author | N | Setting | Period | Design | Type of surgery | Frailty score | Definition of complication | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abt | 1193 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2006-2013 | Prospective | Head and neck cancer surgery | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Adams | 6727 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2010 | Prospective | Head and neck cancer surgery | Modified frailty index | CD 4 or 5 | Good |

| Arya | 23027 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2012 | Prospective | Vascular surgery (Open or EVAR) | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Augustin | 13020 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2010 | Prospective | Pancreatic resections | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Brahmbhatt | 24645 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2012 | Prospective | Infrainguinal vascular surgery | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Bras | 90 | Single-center cohort study | 2008-2013 | Retrospective | Surgery for head and neck cancer | Groningen frailty indicator | CD ≥ 2 | Fair |

| Chappidi | 2679 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2011-2013 | Prospective | Radical cystectomy | Modified frailty index | CD 4 or 5 | Good |

| Chimukangara | 885 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2011-2013 | Prospective | Paraesofageal hernia repair | Modified frailty index | CD ≥ 3 | Fair |

| Cloney | 243 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2000-2012 | Prospective | Glioblastoma surgery | Modified frailty index | Complications (Glioma Outcomes Project System) | Fair |

| Cooper | 415 | Multicenter cohort study | 2010-2013 | Prospective | General and orthopedic surgery | Frailty phenotype; frailty index | Major complications | Fair |

| Courtney-Brooks | 37 | Single-center cohort study | 2011 | Prospective | Surgery for gynecologic cancer | Fried frailty criteria | Surgical complications (NSQIP) | Fair |

| Dale | 76 | Single-center cohort study | 2007-2011 | Prospective | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 4 (of 5) components of Fried frailty criteria; VES-13 | CD ≥ 3 | Fair |

| Dasgupta | 125 | Single-center cohort study | 2002-2003 | Prospective | Elective noncardiac surgery (82%) orthopedic) | Edmonton frail scale | Cardiac - / pulmonary comlications, POD | Fair |

| Farhat | 35334 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2009 | Prospective | Emergency general surgery | Modified frailty index | Any complication (not mortality) | Fair |

| Flexman | 52671 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2006-2012 | Prospective | Spine surgery | Modified frailty index | Major complications | Good |

| Hewitt | 102 | Multicenter cohort study | 2013 | Prospective | Emergency general surgery | Rockwood clinical frailty scale | Not reported | Fair |

| Huisman | 328 | Multicenter cohort study | 2008-2012 | Prospective | Surgery for solid tumors | Groningen frailty indicator; VES-13 | CD ≥ 3 | Good |

| Joseph | 220 | Single-center cohort study | 2012-2014 | Prospective | Emergency general surgery | Rockwood clinical frailty scale | Surgical complications (NSQIP) | Fair |

| Kenig | 184 | Single-center cohort study | 2013-2014 | Prospective | Emergency abdominal surgery | VES-13, GFI; Rockwood; Balducci; TRST; Geriatric-8 | Any complication (CD) | Fair |

| Kim | 197 | Single-center cohort study | 2012-2014 | Prospective | Elective noncardiac surgery | Fried frailty criteria | Surgical complications (NSQIP) | Good |

| Kim | 275 | Single-center cohort study | 2011-2012 | Prospective | Elective intermediate-risk or high-risk surgery | Multidimensional frailty score | Surgical complications (NSQIP) | Good |

| Krishnan | 178 | Single-center cohort study | 2011 | Prospective | Low trauma hip fracture surgery | Frailty index | Not reported | Poor |

| Kristjansson | 178 | Multicenter cohort study | 2008-2011 | Prospective | Elective surgery for colorectal cancer | Comprehensive geriatric assessment | CD ≥ 2 | Good |

| Kua | 82 | Single-center cohort study | 2013 | Prospective | Hip fracture surgery | Edmonton frail scale; (modified) Fried frailty criteria | Any complication | Fair |

| Lascano | 41681 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2013 | Prospective | Surgery for urologic cancer | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Lasithiotakis | 57 | Single-center cohort study | 2008-2011 | Prospective | Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Comprehensive geriatric assessment | Any complication | Poor |

| Leung | 63 | Single-center cohort study | 2007 | Prospective | Noncardiac surgery | Fried frailty criteria | Not reported | Fair |

| Levy | 23104 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2008 to 2014 | Prospective | Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Li | 189 | Single-center cohort study | Not reported | Prospective | Major intra-abdominal surgery | Fried frailty criteria | CD | Fair |

| Louwers | 10300 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2011 | Prospective | Hepatectomy | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Makary | 594 | Single-center cohort study | 2005-2006 | Prospective | Elective surgery | Fried frailty criteria | Surgical complications (NSQIP) | Good |

| McAdams-DeMarco | 537 | Single-center cohort study | 2008-2013 | Prospective | Kidney transplant surgery | Fried frailty criteria | Not reported | Fair |

| McIsaac | 202811 | Single-center cohort study | 2002-2012 | Retrospective | Major elective noncardiac surgery | ACG frailty-defining diagnoses indicator | Not reported | Good |

| McIsaac | 125163 | Single-center cohort study | 2003-2012 | Retrospective | Total joint arthroplasty | ACG frailty-defining diagnoses indicator | ICU-admission | Good |

| Melin | 44832 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2011 | Prospective | Carotid endarterectomy | Frailty-based bedside Risk Analysis Index | Not reported | Fair |

| Mogal | 9986 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2012 | Prospective | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | Modified frailty index | CD 3 or 4 | Good |

| Mosquera | 232352 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2012 | Prospective | elective high-risk surgery | Modified frailty index | Major and minor complications | Fair |

| Neuman | 12979 | Single-center cohort study | 1992-2005 | Retrospective | Elective colorectal cancer surgery | ACG frailty-defining diagnoses indicator | Readmission within 30 days | Fair |

| Obeid | 58448 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2009 | Prospective | Laparoscopic and open colectomy | Modified frailty index | CD 4 or 5 | Fair |

| Partridge | 125 | Single-center cohort study | 2011 | Prospective | Arterial vascular surgery | Edmonton frail scale | Composite postoperative complications | Fair |

| Pearl | 4330 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2011-2014 | Prospective | Radical cystectomy | Modified frailty index | Major in-hospital complications | Good |

| Phan | 3920 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2010-2014 | Prospective | Elective anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) surgery | Modified frailty index | Any complication | Good |

| Reisinger | 159 | Single-center cohort study | 2010-2012 | Prospective | Colorectal surgery | Groningen frailty indicator | Sepsis | Good |

| Revenig | 351 | Single-center cohort study | Not reported | Prospective | Major intra-abdominal surgery | Fried frailty criteria | CD 1-4 | Fair |

| Revenig | 80 | Single-center cohort study | Not reported | Prospective | Intra-abdominal minimally invasive surgery | Fried frailty criteria | CD 1-4 | Fair |

| Revenig | 189 | Single-center cohort study | Not reported | Prospective | Major intra-abdominal surgery | Fried frailty criteria | Any complication | Good |

| Robinson | 72 | Single-center cohort study | 2007-2010 | Prospective | Colorectal surgery | Rockwood clinical frailty scale | Any postoperative complication (VASQIP) | Fair |

| Shin | 6148 ACDF; 817 PCF | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2012 | Prospective | Cervical spine fusion; anterior cervical discectomy and fusion or posterior cervical fusion | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Shin | 14583 THA; 25223 TKA | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2012 | Prospective | Total hip and knee arthroplasty | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Suskind | 95108 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2007-2013 | Prospective | Common urological surgery | Modified frailty index | Major and minor complications | Good |

| Suskind | 20794 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2011-2013 | Prospective | Inpatient urological surgery | Modified frailty index | Not reported | Good |

| Tan | 83 | Multicenter cohort study | 2008-2010 | Prospective | Colorectal surgery | Fried frailty criteria | CD ≥ 2 | Fair |

| Tegels | 127 | Single-center cohort study | 2005-2012 | Retrospective | Surgery for gastric cancer | Groningen frailty indicator | CD ≥ 3 | Fair |

| Tsiouris | 1940 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2005-2010 | Prospective | Open lobectomy | Modified frailty index | CD 4 | Good |

| Ugolini | 46 | Single-center cohort study | 2009-2012 | Prospective | Elective colorectal cancer surgery | Groningen frailty indicator; VES-13 | Not reported | Poor |

| Uppal | 6551 | Multicenter cohort study (NSQIP) | 2008-2011 | Prospective | Surgery for gynecologic cancer | Modified frailty index | CD 4 and 5 | Good |

Abbreviations: CD = Cavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications; NSQIP = National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

Figure 2.

Forest plot 30-day mortality per frailty score. The number of events (deaths) and the total number of patients are shown for both frail and non-frail patients, stratified per frailty assessment tool.

Stratified for frailty assessment tool, the association of frailty and 30-day mortality was observed according to the ACG frailty-defining diagnosis indicator, Fried frailty criteria, Frailty-based Risk Analysis Index and the Modified Frailty Index.

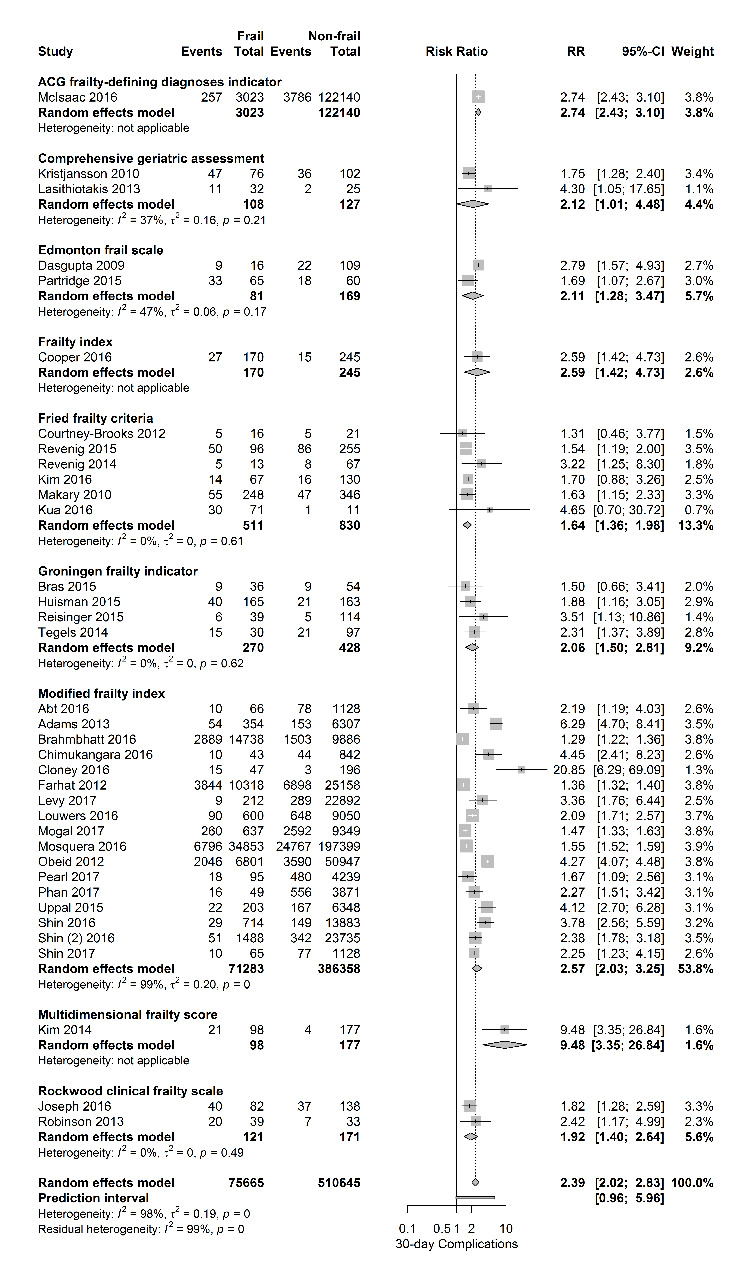

Figure 3 shows the relationship between frailty and the occurrence of postoperative complications, stratified for frailty assessment tool. This adverse outcome was evaluated in 37 papers. Table 1 shows the predefined 30-day complications reported by the authors, in most cases defined as suggested by the Clavien-Dindo classification system. Overall, a positive relationship between frailty and 30-day complications with a pooled RR of 2.39 [95% CI 2.02-3.07] was observed (PI 0.96-5.69; I2=98%), regardless of the frailty score used.

Figure 3.

Forest plot postoperative complications per frailty score. The number of events (complications) and the total number of patients are shown for both frail and non-frail patients, stratified per frailty assessment tool.

Stratified per surgical risk category, pooled RR’s for 30-day mortality were 2.75 [95% CI 2.48-3.05] for high-risk surgery (4 studies), RR 4.79 [95% CI 3.42-6.70] for intermediate-risk surgery (18 studies) and RR 3.06 [95% CI 2.35-3.97] for mixed surgical population (8 studies). The association of frailty and the primary outcome 30-day complications was also stratified per surgical risk category and again a positive relationship was observed with pooled RR’s of 1.62 [95% CI 1.43 -1.82] for high-risk surgery (3 studies) and RR 2.94 [95% CI 2.44-3.54] for intermediate-risk surgery (24 studies).

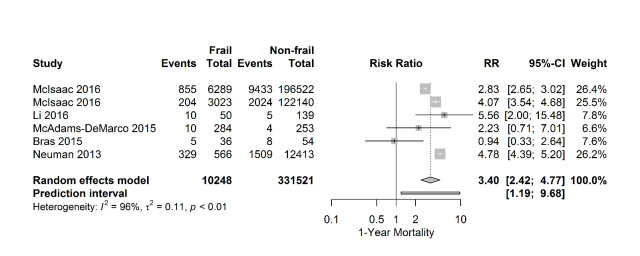

Six studies investigated the association between frailty and one-year mortality (Fig. 4). In most of these studies, frailty increases the risk of one-year mortality with a pooled consequent risk ratio of 3.40 [95% CI 2.42-4.77], (PI 1.19- 9.68; I2=96%).

Figure 4.

Forest plot 1-year mortality. The number of events (one-year mortality) and the total number of patients are depicted for frail and non-frail patients.

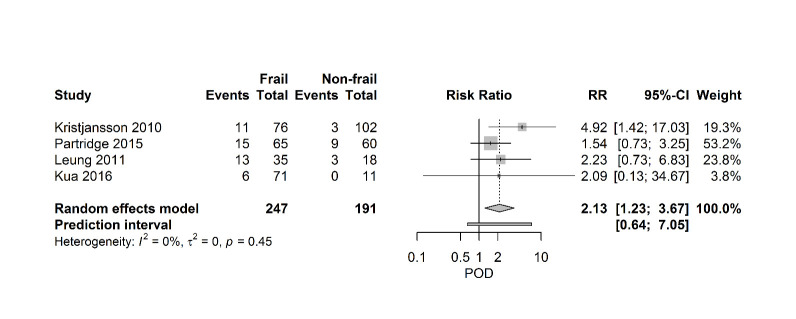

Figure 5 shows a forest plot, which summarizes the relationship between frailty and postoperative delirium. Four studies (438 patients) describe a positive relationship between frailty and POD with a pooled RR of 2.13 [95% CI 1.23-3.67], (PI 0.64- 7.05; I2=0%).

Figure 5.

Forest plot postoperative delirium. The number of events (delirium) and the total number of patients are depicted for frail and non-frail patients.

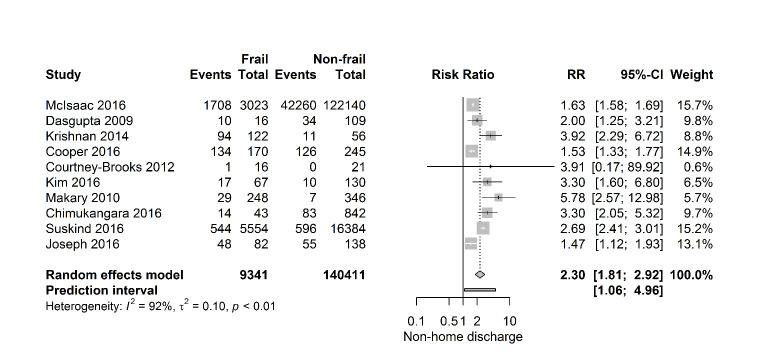

Figure 6 shows that frail patients seem to struggle to return to their own home, as these patients, described in ten studies (149 752 patients), have a twofold higher risk of being discharged to a specialized facility after surgery (RR 2.30 [95% CI 1.81-2.92]), (PI 1.06- 4.96; I2=92%). Just like in 30-day mortality and one-year mortality, the 95% prediction interval for postoperative discharge location showed exclusion of the null value.

Figure 6.

Forest plot discharge to specialized facility. The number of events (discharge to a specialized facility) and the total number of patients are depicted for frail and non-frail patients.

A meta-regression analysis investigating showed no influence of age on primary outcome. Finally, to circumvent the issue of possible duplicate cases, the additional sensitivity analysis excluding studies using ACS-NSQIP database, showed an overall pooled RR of 3.62 [CI 95% 2.21-5.92] (PI 1.46-8.98; I2=14%) for 30-day mortality

DISCUSSION

Since life expectancy keeps rising, the number of frail patients being offered for surgical treatment will dramatically increase. Frail patients are vulnerable and may excessively decompensate after stressors such as surgery, because of their lack of physiological reserve [13].

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found frailty to be a strong predictor of post surgical complications, delirium, institutionalization and all-cause mortality. After reviewing fifty-six articles, 30-day mortality shows the strongest association with preoperative frailty with almost 4 times increased risk.

Our results are congruent with several other reviews investigating the effect of frailty on postoperative outcome. [26-30] However, most of the previous studies focused on specific age groups, specific types of surgery, or specific frailty assessment tool. Therefore, extrapolations to a heterogeneous group of elderly and multimorbid patients should be limited.

The strength of the present study is the extensiveness of the search, the inclusion of different validated frailty scores and the inclusion of different types of non-cardiac surgery, both elective and acute. The quality of this meta-analysis is dependent on the quality of the studies reviewed. Of all studies included 95% were of at least fair quality, with more than half assessed as good quality. Ninety-one percent of all studies were prospectively designed.

Recently, relevant developments have been made towards methodological frameworks, in order to improve the reliability and applicability of prediction studies [31]. Although the authors found improved reporting standards in the last decade, poor reporting and poor methods are still a topic of concern and likely to limit the reliability in this type of clinical research.

The studies in this review and meta-analysis describe eleven different frailty assessment tools. Moreover, the surgical procedures included could basically be divided into six different groups, which will have contributed to the heterogeneity. Heterogeneity, as assessed with I2, t2, Cochran’s Q and prediction intervals, was estimated as a high degree of statistical heterogeneity. Importantly, the association between frailty and outcome seems robust throughout the reviewed articles regardless of the frailty assessment tool used. Furthermore, prediction intervals of 30-day mortality, one-year mortality and postoperative discharge location showed exclusion of the null value, which strengthens our findings.

A plausible explanation may be the fact that frailty was consistently measured by instruments using physical, cognitive and functional domains. Studies using only measurements of body composition or patients’ phenotype, such as sarcopenia, hypoalbuminemia or cachexia were not included, as these studies did not use an established frailty assessment tool. The frailty instrument used in most studies was the modified frailty index (mFI), which has been validated as a reliable assessment tool in several studies [32-36]. It should be recommended that future studies focus on using a standardized, robust and validated frailty assessment tool, which is time-efficient and suitable for the medical staff to be conducted at patient’s bedside.

Limitations of this study are those commonly seen with systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Hence, the results of this review and meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. Besides the heterogeneity, another possible limitation is a variation among studies in the definition of discharge location. Despite these small differences, ten studies confirm that frail patients, when compared to healthier counterparts, struggle to return to their own home. Unfortunately, in many countries, availability of beds and nursing staff in specialized facilities are a topic of current concern. To overcome this limitation the need for rehabilitation or nursing home placement was defined as “not able to return home”. Comparable heterogeneity was found within the definition of postoperative complications. Although most authors defined 30-day complications as suggested by the Clavien-Dindo classification system, others used the American College of Surgery National Surgical Quality Improvement Program definition, or other standardized complication definitions. It should be recommended that future studies in the area of frailty use a standardized postoperative complication definition as this might create a more accurate comparison. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) recently developed the first global standard set of outcome measures in older persons. Their effort towards standardization of outcome measures can possibly improve care pathways and quality of care [37].

Although we have performed an exhaustive literature search, the broad scope of our research question could have resulted in the omission of some studies.

Many studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis are observational registry studies, but several studies have derived their outcomes from clinical trials. Since many studies have used the ACS NSQIP database, there may be studies, which are double counted from the same cohort of patients. However, table 1 shows that most of these studies observed different subgroups of patients, as well as different timeframes and kinds of surgical specialisms. Additionally, the sensitivity analysis we have performed, excluding studies using ACS-NSQIP database, demonstrated a positive relationship between frailty and primary outcomes. Finally, subgroup analyses gave insight in the heterogeneity among the types of surgery and different frailty assessment tools, but this stratification has the drawback of small groups.

In a previous study we have found that the occurrence of postoperative complications is an important prognostic factor of late mortality [38]. Efforts to improve postoperative outcome have predominantly focused on enhanced recovery protocols and the improvement of surgical and anesthetic techniques [39, 40]. The concept of prehabilitation is a modern and proactive approach, based on the principle that structured exercise over a period of weeks leads to a better cardiovascular, respiratory and muscular condition. Optimization of patients’ functional capacity may provide a physiological buffer and enables the patient to better withstand the stress of surgery [39, 41, 42].

Preoperative identification of frail patients provides an opportunity for prehabilitation, which subsequently may lead to reduced postoperative morbidity. Besides prehabilitation, regionalization in health care might improve surgical outcome in complex oncological surgery. Regionalization is about enabling appropriate allocation and integration of health resources, focusing on the local populations needs. Frail patients may benefit from high-volume hospitals with high-volume surgeons in so called centers of excellence [43].

This study demonstrates that the presence of preoperative frailty increases the risk of adverse outcome after non-cardiac surgery. It should be noted that heterogeneity of the frailty scores is high, but associations with postoperative outcome are robust. Frailty status should be considered to be part of the preoperative screening, at least in patients who seem to have a lack of physiological reserve. Identification of potentially reversible health deficits is important, as may provide an opportunity to optimize patients’ clinical condition prior to surgery. Conversely, irreversible frailty should be taken most seriously, as it can guide both clinician and patient in their decision making on whether the patient benefits from surgery or not.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplemenantry data can be found online at: www.aginganddisease.org/EN/10.14336/AD.2019.1024.

Acknowledgements

Wichor M. Bramer, biomedical information specialist, Information Department University Library, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam.

References

- [1].Mangano DT (2004). Perioperative medicine: NHLBI working group deliberations and recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 18:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Partridge JS, Harari D, Dhesi JK (2012). Frailty in the older surgical patient: a review. Age Ageing, 41:142-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, Anker S, Botker HE, De Hert S, et al. (2014). 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur J Anaesthesiol, 31:517-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, Yip AM, Hirsch GM (2010). Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation, 121:973-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Polanczyk CA, Marcantonio E, Goldman L, Rohde LE, Orav J, Mangione CM, et al. (2001). Impact of age on perioperative complications and length of stay in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med, 134:637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Browner WS, Li J, Mangano DT (1992). In-hospital and long-term mortality in male veterans following noncardiac surgery. The Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. JAMA, 268:228-232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Arozullah AM, Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Daley J, Participants in the National Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement P (2001). Development and validation of a multifactorial risk index for predicting postoperative pneumonia after major noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med, 135:847-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Huber CH, Goeber V, Berdat P, Carrel T, Eckstein F (2007). Benefits of cardiac surgery in octogenarians--a postoperative quality of life assessment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 31:1099-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fruitman DS, MacDougall CE, Ross DB (1999). Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: can elderly patients benefit? Quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg, 68:2129-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Filsoufi F, Rahmanian PB, Castillo JG, Chikwe J, Silvay G, Adams DH (2007). Results and predictors of early and late outcomes of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, 21:784-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Baskett R, Buth K, Ghali W, Norris C, Maas T, Maitland A, et al. (2005). Outcomes in octogenarians undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. CMAJ, 172:1183-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sundermann S, Dademasch A, Rastan A, Praetorius J, Rodriguez H, Walther T, et al. (2011). One-year follow-up of patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery assessed with the Comprehensive Assessment of Frailty test and its simplified form. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg, 13:119-123; discussion 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Xue QL (2011). The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med, 27:1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].2017. In Integrated Care for Older People: Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity. Geneva. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004). Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg, 240:205-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].De J, Wand AP (2015). Delirium Screening: A Systematic Review of Delirium Screening Tools in Hospitalized Patients. Gerontologist, 55:1079-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kristensen SD, Knuuti J (2014). New ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management. Eur Heart J, 35:2344-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C (2006). Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med, 144:427-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Graham PL, Moran JL (2012). Robust meta-analytic conclusions mandate the provision of prediction intervals in meta-analysis summaries. J Clin Epidemiol, 65:503-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Rovers MM, Goeman JJ (2016). Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 6:e010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D, Rubinfeld I (2013). Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: Its application to a national database. J Surg Res, 183:104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K (2008). A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr, 8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fuchshuber PR, Greif W, Tidwell CR, Klemm MS, Frydel C, Wali A, et al. (2012). The power of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program--achieving a zero pneumonia rate in general surgery patients. Perm J, 16:39-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. (2001). Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 56:M146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hewitt J, Long S, Carter B, Bach S, McCarthy K, Clegg A (2018). The prevalence of frailty and its association with clinical outcomes in general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing, 47:793-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Oakland K, Nadler R, Cresswell L, Jackson D, Coughlin PA (2016). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between frailty and outcome in surgical patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl, 98:80-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE (2016). Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr, 16:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Panayi AC, Orkaby AR, Sakthivel D, Endo Y, Varon D, Roh D, et al. (2018). Impact of frailty on outcomes in surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang J, Zou Y, Zhao J, Schneider DB, Yang Y, Ma Y, et al. (2018). The Impact of Frailty on Outcomes of Elderly Patients After Major Vascular Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 56:591-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bouwmeester W, Zuithoff NP, Mallett S, Geerlings MI, Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, et al. (2012). Reporting and methods in clinical prediction research: a systematic review. PLoS Med, 9:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ehlert BA, Najafian A, Orion KC, Malas MB, Black JH, Abularrage CJ (2016). Validation of a modified Frailty Index to predict mortality in vascular surgery patients. J Vasc Surg, 63:1595e1592-1601e1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Abt NB, Richmon JD, Koch WM, Eisele DW, Agrawal N (2016). Assessment of the predictive value of the modified frailty index for Clavien-Dindo grade IV critical care complications in major head and neck cancer operations. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 142:658-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ali R, Schwalb JM, Nerenz DR, Antoine HJ, Rubinfeld I (2016). Use of the modified frailty index to predict 30-day morbidity and mortality from spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine, 25:537-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tsiouris A, Hammoud ZT, Velanovich V, Hodari A, Borgi J, Rubinfeld I (2013). A modified frailty index to assess morbidity and mortality after lobectomy. J Surg Res, 183:40-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Uppal S, Igwe E, Rice LW, Spencer RJ, Rose SL (2015). Frailty index predicts severe complications in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol, 137:98-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Akpan A, Roberts C, Bandeen-Roche K, Batty B, Bausewein C, Bell D, et al. (2018). Standard set of health outcome measures for older persons. BMC Geriatr, 18:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tjeertes EK, Ultee KH, Stolker RJ, Verhagen HJ, Bastos Goncalves FM, Hoofwijk AG, et al. (2016). Perioperative Complications are Associated With Adverse Long-Term Prognosis and Affect the Cause of Death After General Surgery. World J Surg, 40:2581-2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wynter-Blyth V, Moorthy K (2017). Prehabilitation: preparing patients for surgery. BMJ, 358:j3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Adamina M, Kehlet H, Tomlinson GA, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP (2011). Enhanced recovery pathways optimize health outcomes and resource utilization: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in colorectal surgery. Surgery, 149:830-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Moorthy K, Wynter-Blyth V (2017). Prehabilitation in perioperative care. Br J Surg, 104:802-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Carli F, Scheede-Bergdahl C (2015). Prehabilitation to enhance perioperative care. Anesthesiol Clin, 33:17-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lumpkin S, Stitzenberg K (2018). Regionalization and Its Alternatives. Surg Oncol Clin N Am, 27:685-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Krishnan M, Beck S, Havelock W, Eeles E, Hubbard RE, Johansen A (2014). Predicting outcome after hip fracture: Using a frailty index to integrate comprehensive geriatric assessment results. Age Ageing, 43:122-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Cooper Z, Rogers SO, Ngo L, Guess J, Schmitt E, Jones RN, et al. (2016). Comparison of Frailty Measures as Predictors of Outcomes After Orthopedic Surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc, 64:2464-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Slaets JP (2006). Vulnerability in the elderly: frailty. Med Clin North Am, 90:593-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bras L, Peters TTA, Wedman J, Plaat BEC, Witjes MJH, van Leeuwen BL, et al. (2015). Predictive value of the Groningen Frailty Indicator for treatment outcomes in elderly patients after head and neck, or skin cancer surgery in a retrospective cohort. Clin Otolaryngol, 40:474-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huisman MG, Audisio RA, Ugolini G, Montroni I, Vigano A, Spiliotis J, et al. (2015). Screening for predictors of adverse outcome in onco-geriatric surgical patients: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol, 41:844-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Reisinger KW, Van Vugt JLA, Tegels JJW, Snijders C, Hulsewé KWE, Hoofwijk AGM, et al. (2015). Functional compromise reflected by sarcopenia, frailty, and nutritional depletion predicts adverse postoperative outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg, 261:345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tegels JJW, de Maat MFG, Hulsewé KWE, Hoofwijk AGM, Stoot JHMB (2014). Value of Geriatric Frailty and Nutritional Status Assessment in Predicting Postoperative Mortality in Gastric Cancer Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg, 18:439-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ugolini G, Pasini F, Ghignone F, Zattoni D, Reggiani MLB, Parlanti D, et al. (2015). How to select elderly colorectal cancer patients for surgery: a pilot study in an Italian academic medical center. Cancer Biol Med, 12:302-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kenig J, Zychiewicz B, Olszewska U, Barczynski M, Nowak W (2015). Six screening instruments for frailty in older patients qualified for emergency abdominal surgery. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 61:437-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kua J, Ramason R, Rajamoney G, Chong MS (2016). Which frailty measure is a good predictor of early post-operative complications in elderly hip fracture patients? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 136:639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Li JL, Henderson MA, Revenig LM, Sweeney JF, Kooby DA, Maithel SK, et al. (2016). Frailty and one-year mortality in major intra-abdominal operations This study was presented at the World Congress of Endourology in London in October 2015. J Surg Res, 203:507.e501-512.e501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Kim S, Liu Y, Sweeney JF, Sarmiento JM, et al. (2015). Report of a simplified frailty score predictive of short-term postoperative morbidity and mortality. J Am Coll Surg, 220:904-911.e901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Master VA, Maithel SK, Kooby DA, Pattaras JG, et al. (2014). A prospective study examining the association between preoperative frailty and postoperative complications in patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery. J Endourol, 28:476-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Tan KY, Kawamura YJ, Tokomitsu A, Tang T (2012). Assessment for frailty is useful for predicting morbidity in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection whose comorbidities are already optimized. Am J Surg, 204:139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kim S, Marsh AP, Rustowicz L, Roach C, Leng XI, Kritchevsky SB, et al. (2016). Self-reported mobility in older patients predicts early postoperative outcomes after elective noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology, 124:815-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Leung JM, Tsai TL, Sands LP (2011). Preoperative frailty in older surgical patients is associated with early postoperative delirium. Anesth Analg, 112:1199-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, et al. (2010). Frailty as a Predictor of Surgical Outcomes in Older Patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg., 210:901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A, King E, Orandi B, Salter M, Gupta N, et al. (2015). Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant, 15:149-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Taylor MD, Tai C, Sweeney JF, Sarmiento JM, et al. (2013). Too frail for surgery? Initial results of a large multidisciplinary prospective study examining preoperative variables predictive of poor surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg, 217:665-670.e661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Courtney-Brooks M, Tellawi AR, Scalici J, Duska LR, Jazaeri AA, Modesitt SC, et al. (2012). Frailty: An outcome predictor for elderly gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol, 126:20-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Adams P, Ghanem T, Stachler R, Hall F, Velanovich V, Rubinfeld I (2013). Frailty as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in inpatient head and neck surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 139:783-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Arya S, Kim SI, Duwayri Y, Brewster LP, Veeraswamy R, Salam A, et al. (2015). Frailty increases the risk of 30-day mortality, morbidity, and failure to rescue after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair independent of age and comorbidities. J Vasc Surg, 61:324-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Augustin T, Burstein MD, Schneider EB, Morris-Stiff G, Wey J, Chalikonda S, et al. (2016). Frailty predicts risk of life-threatening complications and mortality after pancreatic resections. Surgery, 160:987-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Brahmbhatt R, Brewster LP, Shafii S, Rajani RR, Veeraswamy R, Salam A, et al. (2016). Gender and frailty predict poor outcomes in infrainguinal vascular surgery. J Surg Res, 201:156-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chappidi MR, Kates M, Patel HD, Tosoian JJ, Kaye DR, Sopko NA, et al. (2016). Frailty as a marker of adverse outcomes in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chimukangara M, Frelich MJ, Bosler ME, Rein LE, Szabo A, Gould JC (2016). The impact of frailty on outcomes of paraesophageal hernia repair. J Surg Res, 202:259-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cloney M, D'Amico R, Lebovic J, Nazarian M, Zacharia BE, Sisti MB, et al. (2016). Frailty in Geriatric Glioblastoma Patients: A Predictor of Operative Morbidity and Outcome. World Neurosurg, 89:362-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton JH Jr, et al. (2012). Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 72:1526-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Flexman AM, Charest-Morin R, Stobart L, Street J, Ryerson CJ (2016). Frailty and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spine disease. Spine J, 16:1315-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lascano D, Pak JS, Kates M, Finkelstein JB, Silva M, Hagen E, et al. (2015). Validation of a frailty index in patients undergoing curative surgery for urologic malignancy and comparison with other risk stratification tools. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Invest, 33:426.e421-426.e412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Levy I, Finkelstein M, Bilal KH, Palese M (2017). Modified frailty index associated with Clavien-Dindo IV complications in robot-assisted radical prostatectomies: A retrospective study. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Invest. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Louwers L, Schnickel G, Rubinfeld I (2016). Use of a simplified frailty index to predict Clavien 4 complications and mortality after hepatectomy: Analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project database. Am J Surg, 211:1071-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Mogal H, Vermilion SA, Dodson R, Hsu FC, Howerton R, Shen P, et al. (2017). Modified Frailty Index Predicts Morbidity and Mortality After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Mosquera C, Spaniolas K, Fitzgerald TL (2016). Impact of frailty on surgical outcomes: The right patient for the right procedure. Surgery, 160:272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Obeid NM, Azuh O, Reddy S, Webb S, Reickert C, Velanovich V, et al. (2012). Predictors of critical care-related complications in colectomy patients using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: Exploring frailty and aggressive laparoscopic approaches. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 72:878-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pearl JA, Patil D, Filson CP, Arya S, Alemozaffar M, Master VA, et al. (2017). Patient Frailty and Discharge Disposition Following Radical Cystectomy. Clin Genitourin Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Phan K, Kim JS, Lee NJ, Somani S, Di Capua J, Kothari P, et al. (2017). Frailty is associated with morbidity in adults undergoing elective anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) surgery. Spine J, 17:538-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Suskind AM, Jin C, Cooperberg MR, Finlayson E, Boscardin WJ, Sen S, et al. (2016). Preoperative Frailty Is Associated With Discharge to Skilled or Assisted Living Facilities After Urologic Procedures of Varying Complexity. Urology, 97:25-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Suskind AM, Walter LC, Jin C, Boscardin J, Sen S, Cooperberg MR, et al. (2016). Impact of frailty on complications in patients undergoing common urological procedures: A study from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement database. BJU Int. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Shin JI, Keswani A, Lovy AJ, Moucha CS (2016). Simplified Frailty Index as a Predictor of Adverse Outcomes in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 31:2389-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Shin JI, Kothari P, Phan K, Kim JS, Leven D, Lee NJ, et al. (2017). Frailty Index as a Predictor of Adverse Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Cervical Spinal Fusion. Spine, 42:304-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Tahir A, Rockwood K (2006). Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing, 35:526-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Dasgupta M, Rolfson DB, Stolee P, Borrie MJ, Speechley M (2009). Frailty is associated with postoperative complications in older adults with medical problems. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 48:78-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Partridge JSL, Fuller M, Harari D, Taylor PR, Martin FC, Dhesi JK (2015). Frailty and poor functional status are common in arterial vascular surgical patients and affect postoperative outcomes. Int J Surg, 18:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. (2005). A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ, 173:489-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Hewitt J, Moug SJ, Middleton M, Chakrabarti M, Stechman MJ, McCarthy K (2015). Prevalence of frailty and its association with mortality in general surgery. Am J Surg, 209:254-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Joseph B, Zangbar B, Pandit V, Fain M, Mohler MJ, Kulvatunyou N, et al. (2016). Emergency General Surgery in the Elderly: Too Old or Too Frail? Presented orally at the Surgical Forum of the American College of Surgeons 100th Annual Clinical Congress, San Francisco, CA, October 2014. J Am Coll Surg, 222:805-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L, Dunn CL, Cleveland JC Jr, Moss M (2013). Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg, 206:544-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, et al. (2001). The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc, 49:1691-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Dale W, Hemmerich J, Kamm A, Posner MC, Matthews JB, Rothman R, et al. (2014). Geriatric assessment improves prediction of surgical outcomes in older adults undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: A prospective cohort study. Ann Surg, 259:960-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Lieberman R AC, Weiner JP 2003. Development and Evaluation of the Johns Hopkins University Risk Adjustment Models for Medicare ? Choice Plan Payment.: Baltimore, MD; Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- [95].Neuman HB, Weiss JM, Leverson G, O’Connor ES, Greenblatt DY, Loconte NK, et al. (2013). Predictors of Short-Term Postoperative Survival after Elective Colectomy in Colon Cancer Patients ≥80 Years of Age. Ann Surg Oncol, 20:1427-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C (2016). Association of Frailty and 1-Year Postoperative Mortality Following Major Elective Noncardiac Surgery: A Population-Based Cohort Study. JAMA Surg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].McIsaac DI, Beaule PE, Bryson GL, Van Walraven C (2016). The impact of frailty on outcomes and healthcare resource usage after total joint arthroplasty: a population-based cohort study. Bone Joint J, 98-B:799-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, et al. (2010). Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg, 210:901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Melin AA, Schmid KK, Lynch TG, Pipinos II, Kappes S, Longo GM, et al. (2015). Preoperative frailty risk analysis index to stratify patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg, 61:683-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Balducci L, Beghe C (2000). The application of the principles of geriatrics to the management of the older person with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 35:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhøy MS, Skovlund E, Audisio RA, Johannessen HO, et al. (2010). Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: A prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 76:208-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Lasithiotakis K, Petrakis J, Venianaki M, Georgiades G, Koutsomanolis D, Andreou A, et al. (2013). Frailty predicts outcome of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in geriatric patients. Surg Endosc Interv Tech, 27:1144-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, Kim KI, Hwang DW, Kang SB, et al. (2014). Multidimensional Frailty Score for the Prediction of Postoperative Mortality Risk. JAMA Surg., 149:633-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplemenantry data can be found online at: www.aginganddisease.org/EN/10.14336/AD.2019.1024.