Abstract

The underlying cell types mediating predisposition to obesity remain largely obscure. Here, we integrated recently published single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from 727 peripheral and nervous system cell types spanning 17 mouse organs with body mass index (BMI) genome-wide association study (GWAS) data from >457,000 individuals. Developing a novel strategy for integrating scRNA-seq data with GWAS data, we identified 26, exclusively neuronal, cell types from the hypothalamus, subthalamus, midbrain, hippocampus, thalamus, cortex, pons, medulla, pallidum that were significantly enriched for BMI heritability (p<1.6×10−4). Using genes harboring coding mutations associated with obesity, we replicated midbrain cell types from the anterior pretectal nucleus and periaqueductal gray (p<1.2×10−4). Together, our results suggest that brain nuclei regulating integration of sensory stimuli, learning and memory are likely to play a key role in obesity and provide testable hypotheses for mechanistic follow-up studies.

Research organism: Human, Mouse

Introduction

Identification of genes and cell types underlying susceptibility to human obesity remains a critically important step toward a better understanding of mechanisms causing the disease (Hekselman and Yeger-Lotem, 2020). Studies of monogenic obesity syndromes and rodent models of obesity have identified melanocortin signaling circuits in the mediobasal and paraventricular hypothalamus as key components in energy homeostasis and obesity (Morton et al., 2014; Farooqi and O'Rahilly, 2006; Betley et al., 2013). Yet growing evidence suggests that susceptibility to obesity is distributed across numerous brain areas that receive signals emanating from internal sources (e.g. viscerosensory input from the gastrointestinal tract) or external stimuli (e.g. the sight or smell of food) that act in concert to regulate feeding behavior and energy stores (Grill, 2006; Zeltser, 2018; Grill and Hayes, 2012). However, despite an increasing number of genes, cell types and neuronal circuits being implicated in murine energy homeostasis, the identity of brain cell types that drive susceptibility to human obesity remains largely unknown and a systematic assessment of cell types’ relevance in obesity is currently lacking.

In recent years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified about a thousand common (minor allele frequency, MAF ≥0.1) single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that associate with body mass index (BMI, defined as weight in kilogram divided by height in meters squared), a heritable and commonly used proxy phenotype for obesity (Locke et al., 2015; Yengo et al., 2018). In general, the far majority of trait-associated SNPs are located in regulatory regions and hence, unlike coding variants, tagging genetic intervals (or loci) rather than implicating specific genes. Importantly, these loci represent an unbiased set of biological sign posts to genes and biological mechanisms underlying susceptibility to obesity (Hirschhorn, 2009).

Genetic variants with rare frequencies (MAF <0.1) that are typically too low to be captured in GWAS are thought to contribute ~50% to the heritability of BMI (Wainschtein et al., 2019). Many such variants are coding mutations (Wainschtein et al., 2019) and hence well-suited to identify causal genes underlying obesity. Lately, rare variant association studies have identified 14 coding variants across 13 genes in an exome chip analysis across >750,000 individuals (Turcot et al., 2018). Interestingly, these genes, with the exception of MC4R, KSR2 and GIPR, have not previously been implicated in obesity, suggesting that key biologic mechanisms underlying obesity have yet to be identified.

Given that a majority of obesity-associated gene variants likely regulate gene expression rather than impact protein function, gene expression data provide an effective scaffold to inform GWAS data for obesity and other traits (Finucane et al., 2015; Calderon et al., 2017; Pers et al., 2015; Hao et al., 2018). In 2016, we used microarray-based gene expression data to show that genes in BMI GWAS loci are predominantly expressed in the brain (Locke et al., 2015) and we recently leveraged mouse; single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) to implicate mediobasal hypothalamic cell types in obesity (Campbell et al., 2017). The growing number of BMI GWAS loci and genes implicated through rare-variant association studies of common and syndromic forms of obesity, in conjunction with the growing number of large-scale scRNA-seq atlases, provide a unique opportunity to systematically uncover genes and cell types underlying biological circuits regulating susceptibility to human obesity.

Here, we developed two computational toolkits for human genetics-driven identification of cell types underlying disease and leveraged them to systematically identify cell types enriching for obesity susceptibility by combining publicly available BMI GWAS summary statistics from >457,000 individuals with scRNA-seq data spanning 380 cell types representing adult mouse organs especially the nervous system and 347 cell types from the adult mouse hypothalamus.

Results

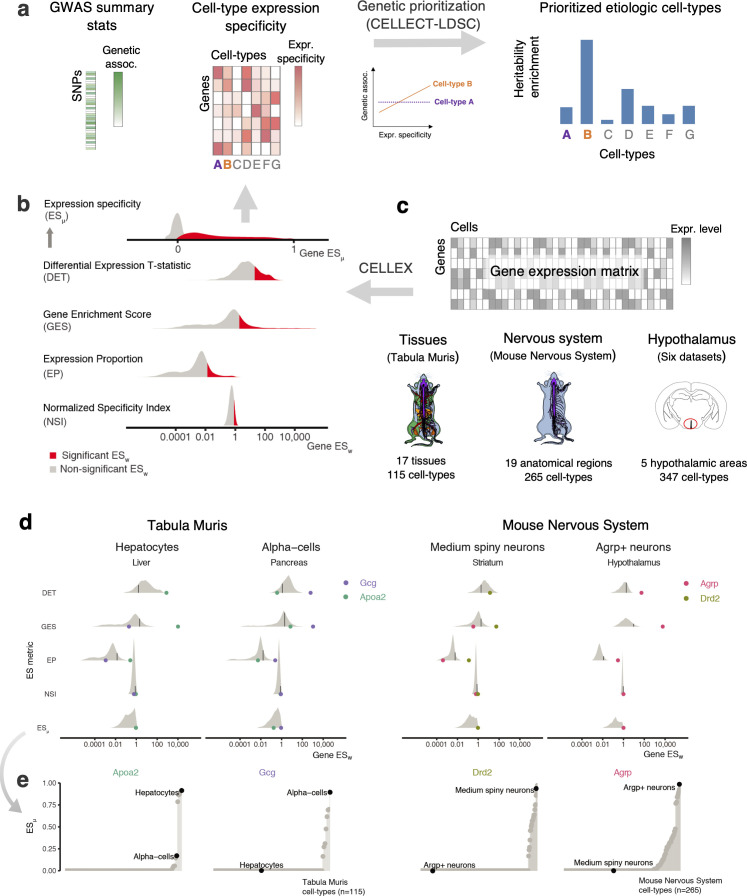

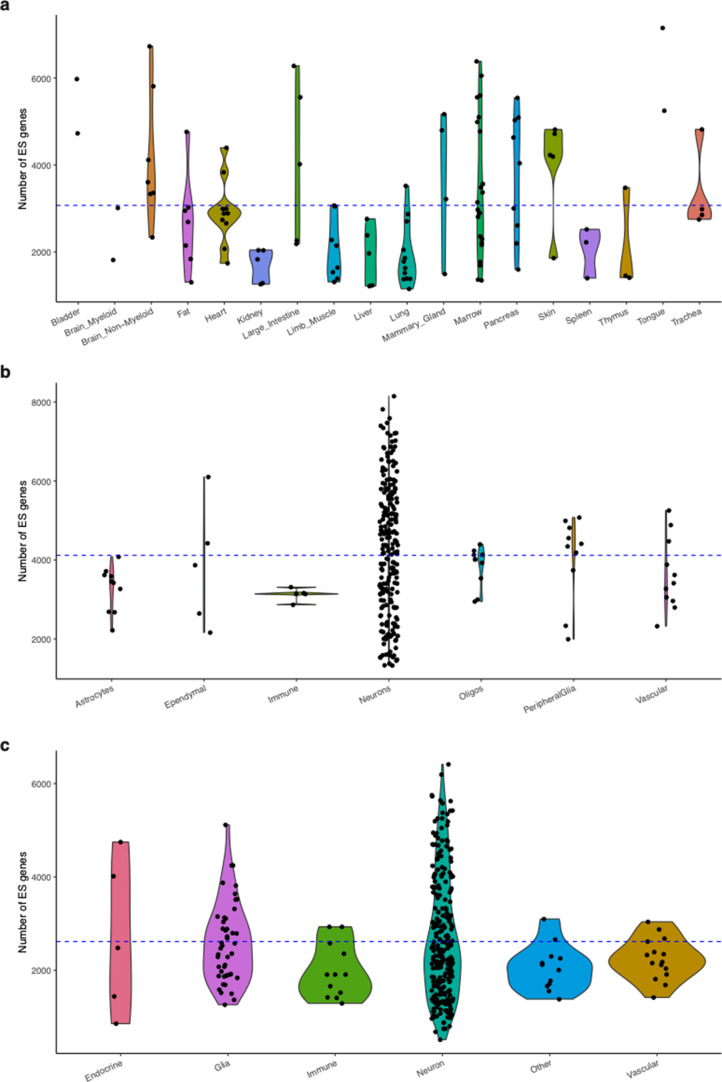

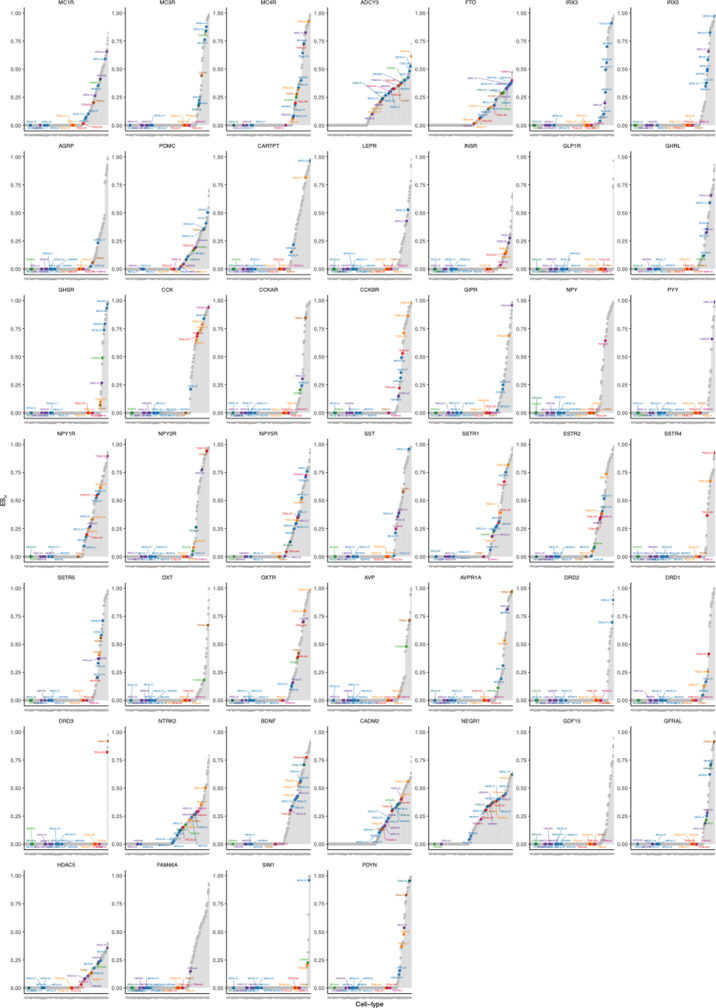

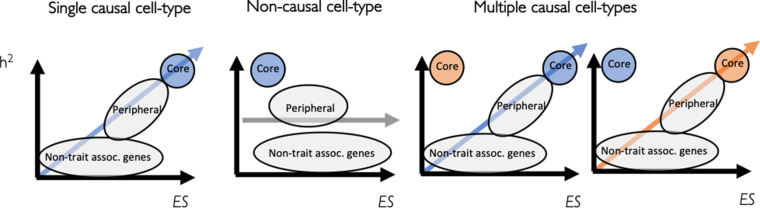

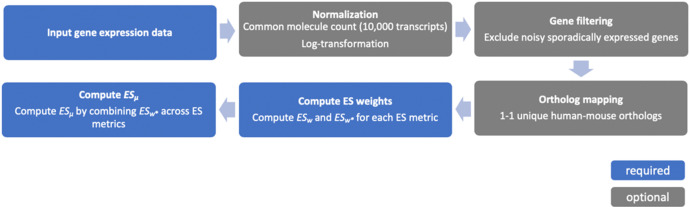

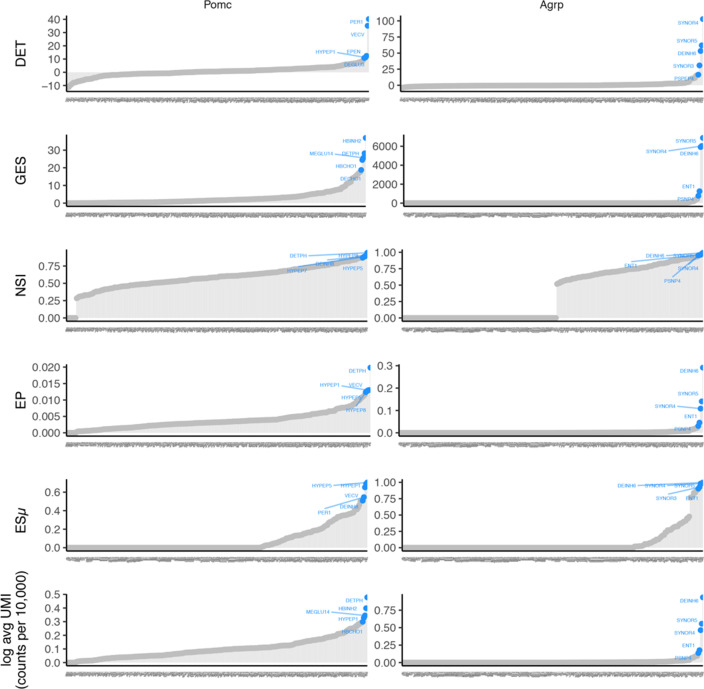

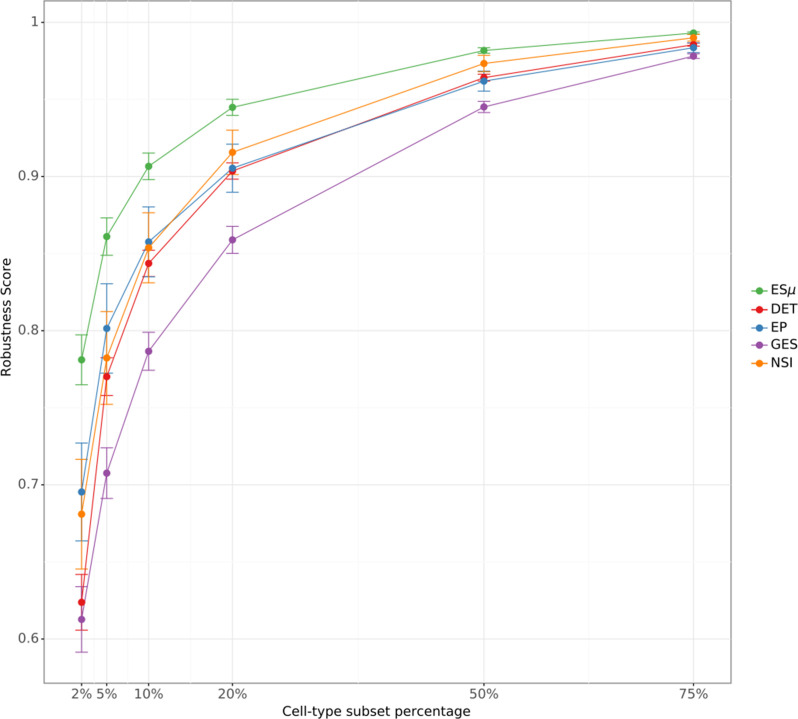

Devising a robust cell type expression specificity metric and prioritization framework

Similar to previous approaches (Campbell et al., 2017; Skene et al., 2018; Watanabe et al., 2019; Bryois et al., 2020), we hypothesized that cell types exhibiting detectable expression of genes colocalizing with BMI GWAS loci are more likely to underlie obesity than cell types in which these genes are not expressed. Based on this reasoning, we developed CELLECT (CELL type Expression-specific integration for Complex Traits) and CELLEX (CELL type EXpression-specificity), two toolkits for genetic identification of likely etiologic cell types. Given GWAS summary statistics and scRNA-seq data, CELLECT can quantify the enrichment of heritability in or near genes specifically expressed in a given cell type using established genetic prioritization models, such as S-LDSC (Finucane et al., 2015), RolyPoly (Calderon et al., 2017), DEPICT (Pers et al., 2015) or MAGMA covariate analysis (Skene et al., 2018) (Materials and methods; Figure 1a). Importantly, whereas previous frameworks for genetic prioritization of cell types have either relied on non-polygenic models (Campbell et al., 2017), used binary or discrete representations of cell type expression (Finucane et al., 2015; Skene et al., 2018) or used average expression profiles (Watanabe et al., 2019), CELLECT uses a robust continuous representation of cell type expression. In Appendix 1, we provide a discussion of our model, its assumptions and relationship to the ‘omnigenic’ model hypothesis (Liu et al., 2019; Boyle et al., 2017). Conjointly, CELLEX was built on the observation that different measures of gene expression specificity (ES) provide complementary information and it therefore combines four ES metrics (see Materials and methods) into a single measure (ESμ) representing the score that a gene is specifically expressed in the given cell type (Materials and methods; Figure 1b). We first tested and validated the ES approach on the Tabula Muris dataset (Tabula Muris Consortium et al., 2018), a Smart-Seq2 scRNA-seq dataset derived from 17 organs from adult male and female mice, and on the Mouse Nervous System dataset (Zeisel et al., 2018), a droplet-based scRNA-seq dataset derived from 19 central and peripheral nervous system regions from late-postnatal male and female mice. For both datasets, we computed gene expression specificities for the four metrics and combined them into ESμ across four cell types with known marker genes and found that ESμ correctly identified them as being among the most specifically expressed genes (Figure 1d,e). We respectively identified a median of 2810 and 4020 specifically expressed genes per cell type and hierarchical clustering of cell types based on the ESμ estimates largely reproduced the cell type dendrograms from the respective original publications (Tabula Muris Consortium et al., 2018; Zeisel et al., 2018), confirming that our ES approach enables cell types profiles to be compared across studies and single-cell protocols (Figure 1—figure supplements 1 and 2). In Appendix 2, we provide a detailed description of the CELLEX workflow, its assumptions and we use re-sampling to demonstrate the robustness of ESμ compared to individual ES metrics. We implemented and released CELLECT and CELLEX as open-source Python packages (see URLs). Here, we – due to its polygenic nature and well-controlled type I error rate – used CELLECT with S-LDSC as the genetic prioritization model to quantify the effects of cell type ES on BMI heritability. For each cell type, we reported the P-value for the one-tailed test for positive contribution of the cell type ES to trait heritability (conditional on a ‘baseline model’ that accounted for the non-random distribution of heritability across the genome, see Materials and methods).

Figure 1. Overview of CELLECT and CELLEX and main datasets used (a) CELLECT quantifies the association between common polygenetic GWAS signal (heritability) and cell type expression specificity (ES) to prioritize relevant etiological cell types.

As input to CELLECT, we used BMI GWAS summary statistics derived from analysis of UK Biobank data (N > 457,000 individuals) and ES was calculated using CELLEX. (b) CELLEX uses a ‘wisdom of the crowd’ approach by averaging multiple ES metrics into ESμ, a robust ES measure that captures multiple aspects of expression specificity. Prior to averaging ES metrics, CELLEX determines the significance of individual ES metric estimates (ESw), indicated by the red and gray colored areas. (c) scRNA-seq datasets analyzed in this study. In total, the associations between 727 cell types and BMI heritability were analyzed. Anatograms modified from gganatogram (Maag, 2018). (d) Example of the CELLEX approach for selected cell types and relevant marker genes. The log-scale distribution plot of ESw illustrate differences of ES metrics. For each ES metric distribution, a black line is shown to indicate the cut-off value for ESw significance. In most cases, the ES metrics identified the relevant marker gene as having a significant ESw. In all cases, the marker gene was correctly estimated as having ESμ~1. We note that the majority of genes have ESμ=0 and were omitted from the log-scale plot. (e) ESμ plots showing the specificity and sensitivity of our approach. The plots depict ESμ for the genes shown in panel (d) across all cell types in the respective datasets. For each marker gene, the relevant cell type has the highest ESμ estimate (high sensitivity) and cell types in which the given gene is likely to have a lesser role have near zero ESμ estimates (high specificity). BMI, body mass index; ES, expression specificity; GWAS, genome-wide association study; UK, United Kingdom; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA-sequencing.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Number of ES genes.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Hierarchical clustering of cell types using ESμ.

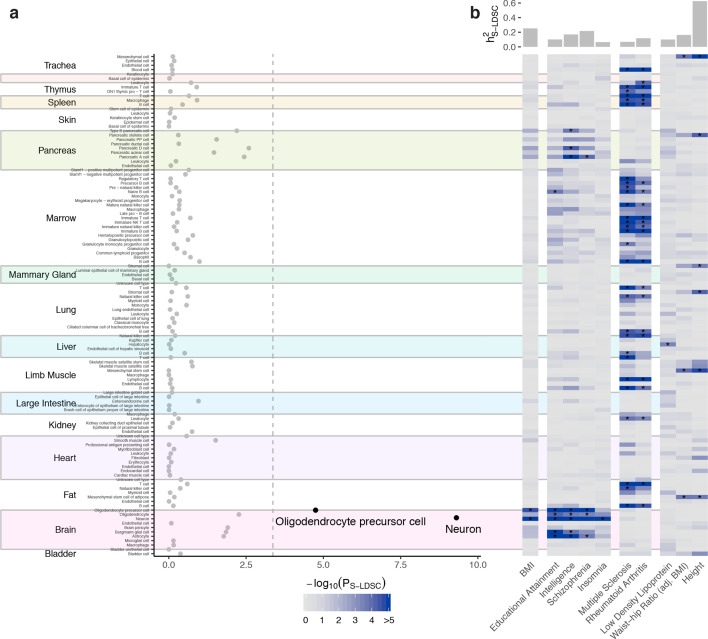

BMI variants enrich for central nervous system rather than peripheral cell types

Using BMI GWAS summary statistics from a GWAS analysis of the UK Biobank (Bycroft et al., 2018) comprising >457,000 individuals (Loh et al., 2018) and the Tabula Muris cell types, we first assessed whether we could replicate the exclusive enrichment of BMI GWAS variants in brain tissues as reported by Locke et al., 2015. Applying CELLECT to the 115 – mostly peripheral – cell types, we identified two significantly enriched cell types, namely neurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Bonferroni correction-based false-discovery rate, FDR < 0.05; Figure 2a). When rerunning CELLECT conditioning on the neuron cell type, the oligodendrocyte precursor cell type was no longer significant, suggesting that we primarily observed a neuronal signal for the BMI GWAS variants. In order to verify that our approach, in general, could identify relevant cell types for complex traits, we computed enrichments for nine GWAS including cognitive, psychiatric, neurological, immunological, lipid and anthropometric traits and disorders, and found that CELLECT prioritized etiologically relevant cell types across all six categories (Figure 2b). Cortical neurons were prioritized for cognitive traits and psychiatric disorders (educational attainment, intelligence, schizophrenia), neuronal cell types for insomnia, immune cells for multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, growth-related cell types for waist-to-hip ratio (adjusted for BMI) and height, and hepatocytes for low-density lipoprotein levels (see Figure 2—source data 3 for results across additional 29 traits). Finally, using 1000 ‘null GWAS’ constructed based simulated Gaussian phenotypes with no genetic basis, we found that CELLECT had a properly controlled type I error and that results were not confounded by the median number of genes and transcripts per cell (there was a negligible correlation with the number of cells for a given cell type [Pearson’s rho = 0.01, p=4.0×10−4], which disappeared when we adjusted for the number of ESμ genes for a given cell population [Figure 2—figure supplement 1]). These data establish the ability of this approach to validate previous evidence (Locke et al., 2015) that BMI variants tend to colocalize with genes specifically expressed in neurons, while also demonstrating that CELLECT is able to prioritize relevant cell types across a number of complex traits.

Figure 2. Cell type prioritization across 17 tissues highlights a key role of the brain in obesity.

(a) Prioritization of 115 Tabula Muris cell types identified two cell types from the brain as significantly associated with BMI, namely oligodendrocyte precursor cells and neurons (shown in black; Bonferroni significance threshold, PS-LDSC <0.05/115). (b) Heatmap of cell type prioritization for multiple GWAS traits. BMI results (first column) are the same as in panel (a) and projected onto the heatmap. The four brain-related traits (second column) were associated with cell types in the brain, the two immune traits (third column) were associated with immune cells, and anthropometric traits (fourth column) were associated with mesenchymal stem cells, which are progenitor cells for muscle, bone and fat. Asterisks (*) mark cell types passing the per-trait Bonferroni significance threshold. The top bar plot shows the estimated trait heritability. An overview of the GWAS files used in this work are available in the Figure 2—source data 1, metadata for the Tabula Muris dataset are available in Figure 2—source data 2 and the CELLECT results for the Tabula Muris dataset are available in Figure 2—source data 3. S-LDSC, stratified-linkage disequilibrium score regression; h2S-LDSC, trait SNP-heritability.

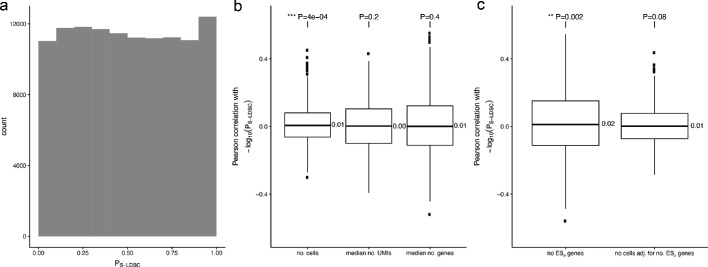

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Tests for confounding factors.

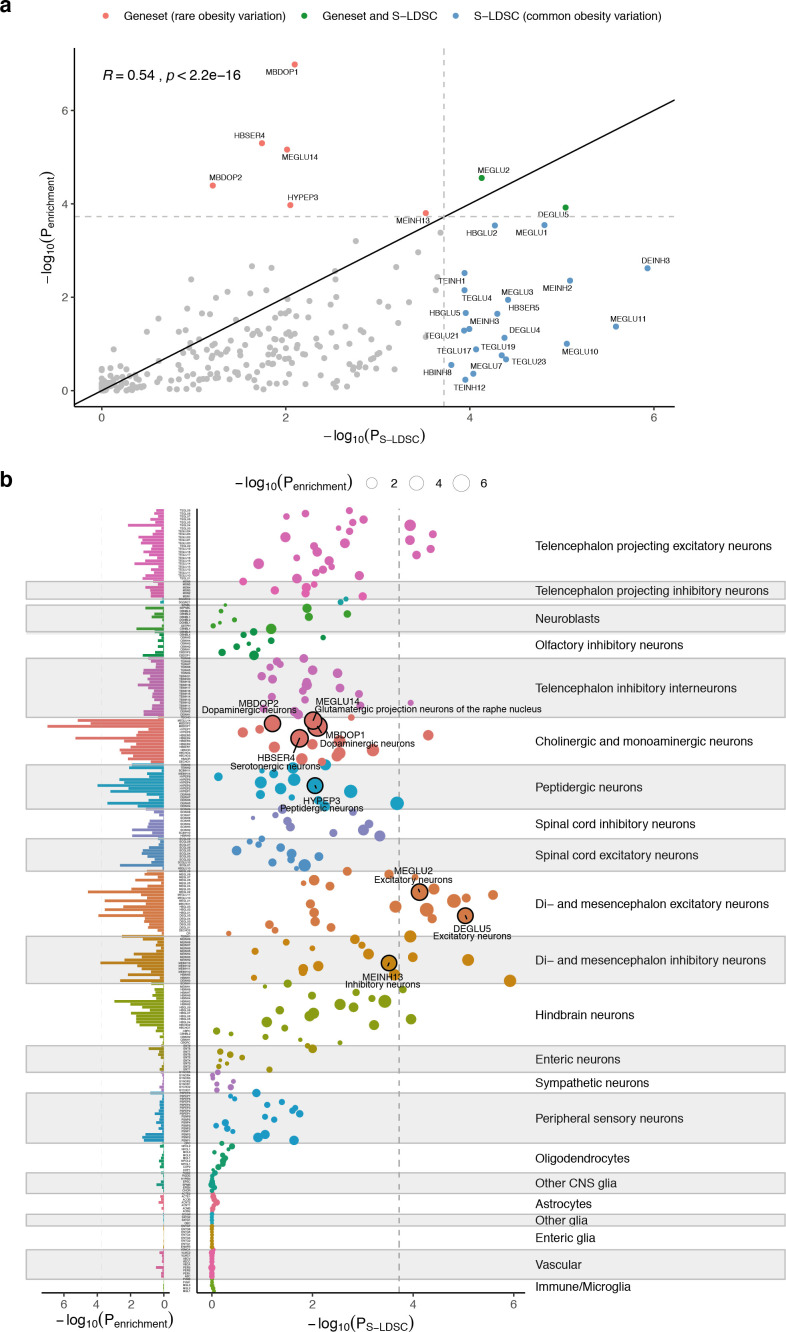

A distributed set of neuronal cell types enrich for obesity susceptibility

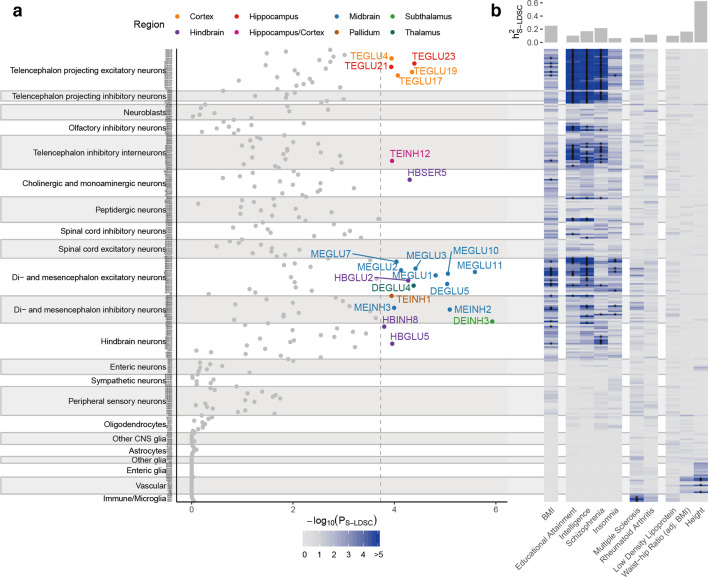

We next assessed whether we could identify specific CNS cell types enriching for BMI-associated variants. Applying CELLEX and CELLECT on 265 cell types from the across the Mouse Nervous System dataset, we identified 22 enriched cell types annotated to eight brain regions (Figure 3a). To assess the specificity of the BMI GWAS signal in these 22 cell types, we computed enrichments for the panel of nine other well-powered traits. As expected, none of the five traits primarily caused by peripheral etiologies enriched for any nervous system cell type and several of 22 BMI GWAS-enriched cell types also enriched for cognitive traits and psychiatric disorders (Figure 3b). Sixteen of the 22 cell types were also enriched ‘intelligence’ and ‘worry’, two traits genetically anticorrelated with obesity (overlapping sets of associated loci with opposite effect sizes) (Marioni et al., 2016; Nagel et al., 2018).

Figure 3. Cell type prioritization of mouse nervous system cell types highlights cell types outside canonical energy homeostasis circuits.

(a) Prioritization of 265 mouse nervous system cell types identified 22 cell types from eight distinct brain regions as significantly associated with BMI. The highlighted cell types passed the Bonferroni significance threshold, PS-LDSC <0.05/265. Cell types are grouped by the taxonomy described in Zeisel et al., 2018. (b) Heatmap of cell type prioritization for multiple GWAS traits. The four brain-related traits (second column) were primarily associated with cortical neurons (telencephalon projecting and interneuron cell types) and did not overlap with the BMI-associated cell types. The two immune traits (third column) were associated with microglia, and anthropometric traits (fourth column) were predominantly associated with vascular cell types. Asterisks (*) mark cell types passing the per-trait Bonferroni significance threshold. The top bar plot shows the estimated trait heritability. Metadata for the Mouse Nervous System dataset are available in Figure 3—source data 1, CELLECT results for the Mouse Nervous System dataset are available in Figure 3—source data 2, CELLEX expression specificity values for the BMI GWAS-enriched cell types are available in Figure 3—source data 3 and cognitive traits and psychiatric disorders CELLECT results limited to the 22 BMI GWAS-enriched cell types are available in Figure 3—source data 4.

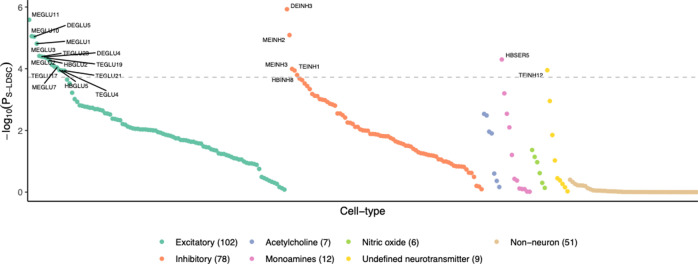

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. BMI-prioritized Mouse Nervous System cell type neurotransmitter classes BMI GWAS prioritized cell types prioritization enriched for neurons.

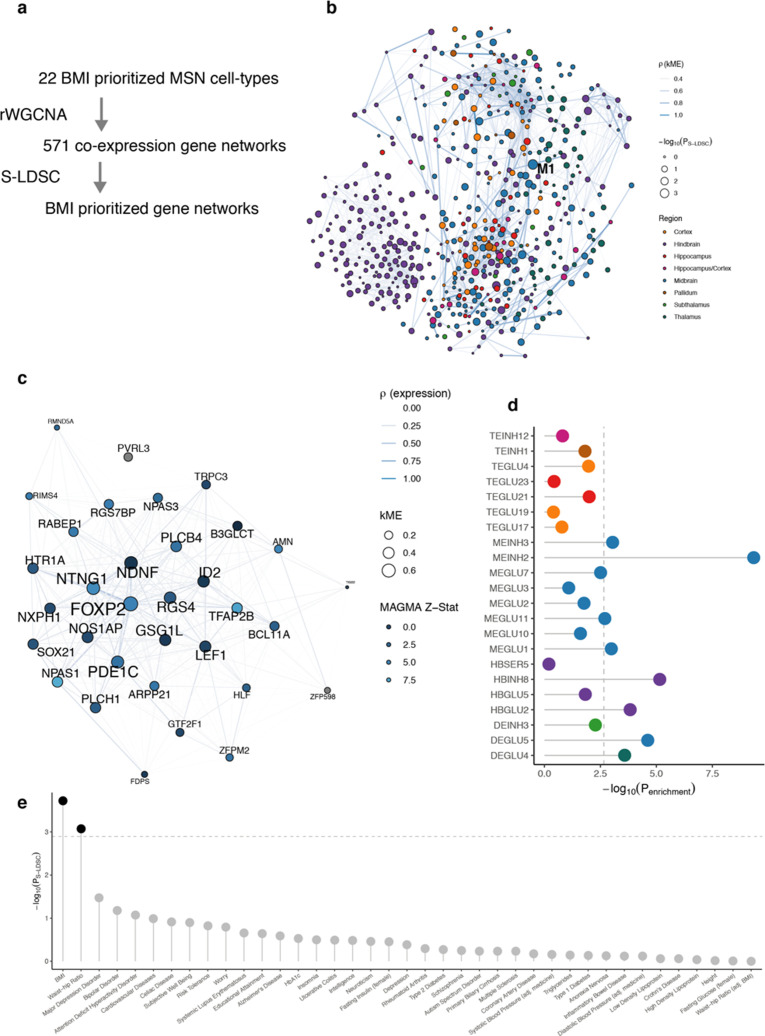

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Genetic prioritization of cell type gene co-expression networks.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Robustness of cell type prioritization results.

Similar to previous work, we did not find any enrichment of genetic variants associated with BMI in non-neuronal cell types (Campbell et al., 2017; Watanabe et al., 2019) nor did we detect enrichment for a particular type of neurotransmitter type (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA [Langfelder and Horvath, 2008]) on expression data from each of the 22 BMI-enriched cell types identified no significant modules (Figure 3—figure supplement 2; top associated module, p=1.88×10−4; FDR ≤ 0.1). These findings emphasize that the BMI-associated variants most likely are distributed across hundreds of genes rather than the relatively limited number of genes captured in cell-type-specific WGCNA modules (see Appendix 3 for a discussion on limitations of identifying gene co-expression networks from cell type scRNA-seq data).

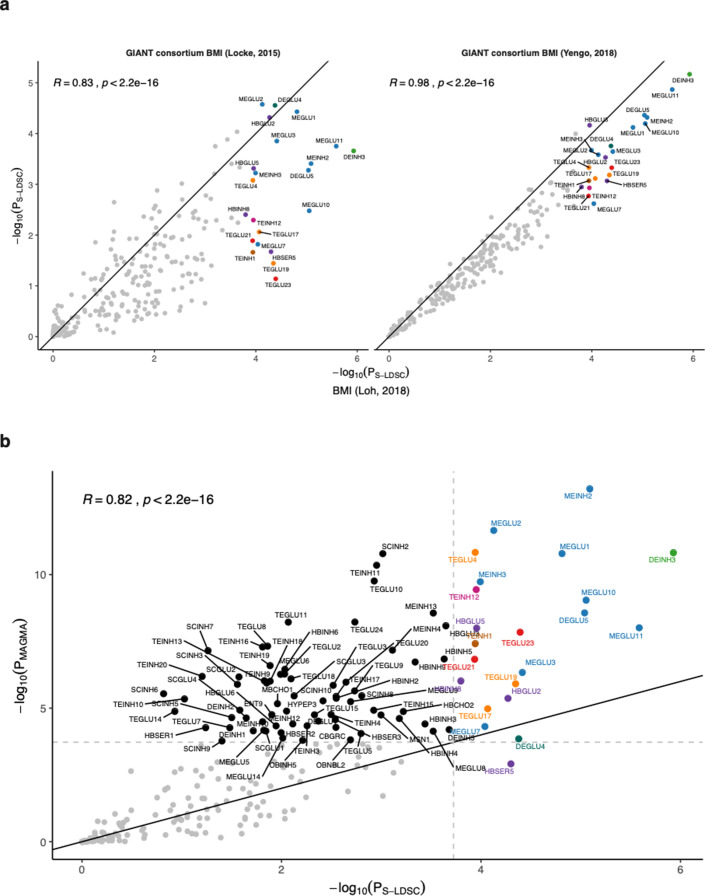

To assess the dependence of the results on a given enrichment methodology and BMI GWAS, we re-computed enrichments using the Yengo et al., 2018 and Locke et al., 2015 BMI GWAS summary statistics and the MAGMA tool (de Leeuw et al., 2015). We observed that the results were robust to different GWAS sample sizes and inclusion of Metabochip array-based association data (Yengo et al. and Locke et al. GWAS Pearson’s R = 0.98 and R = 0.83, respectively), and largely invariant to the enrichment methodology used (Pearson’s R = 0.82; Figure 3—figure supplement 3). Finally, during finalizing this work another study focused on Parkinson’s disease, reported BMI GWAS enrichments for the same mouse nervous system cell types (overlap; 6/10) (Bryois et al., 2020). Together, these results demonstrate that BMI-associated variants are likely to exert their effect across multiple, predominantly neuronal cell types, several of which enrich for cognitive traits and psychiatric disorders genetically correlated with obesity.

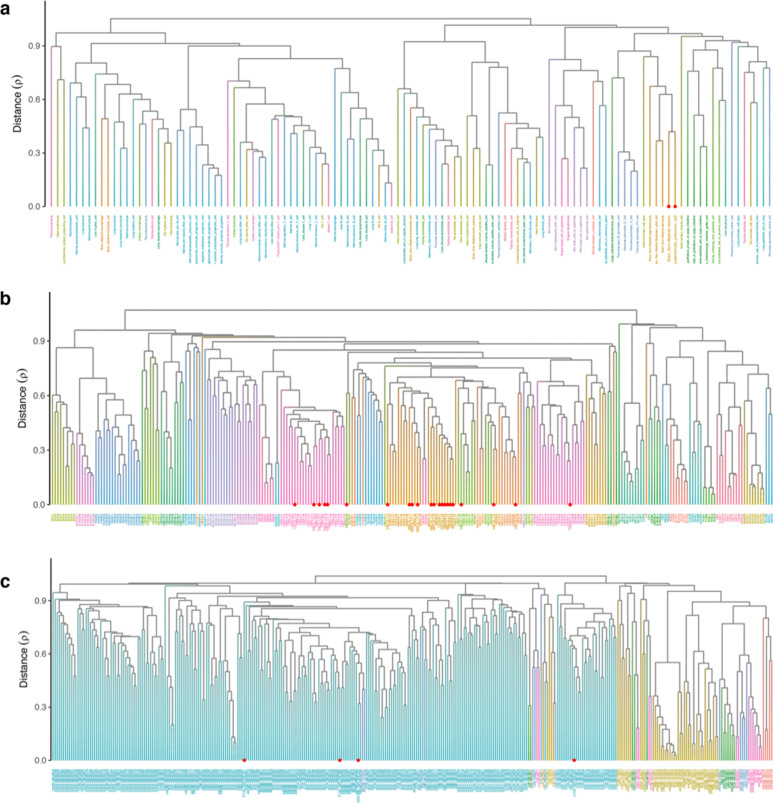

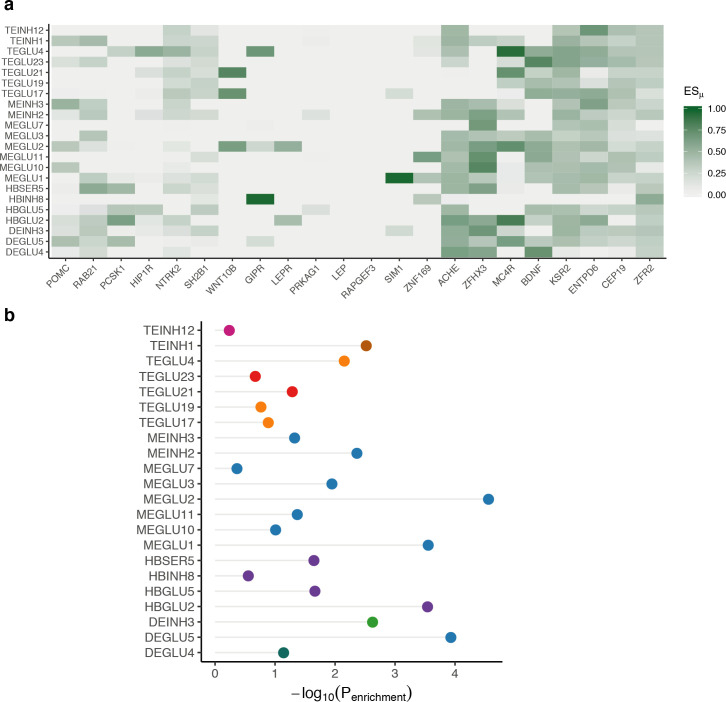

The enriched neuronal cell types share transcriptional similarities

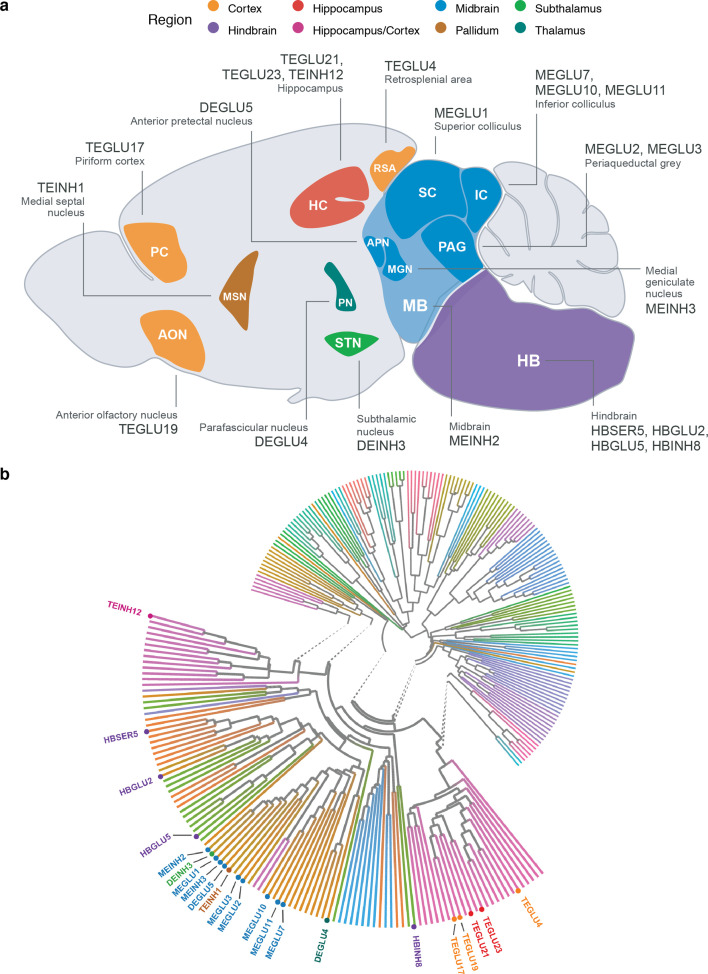

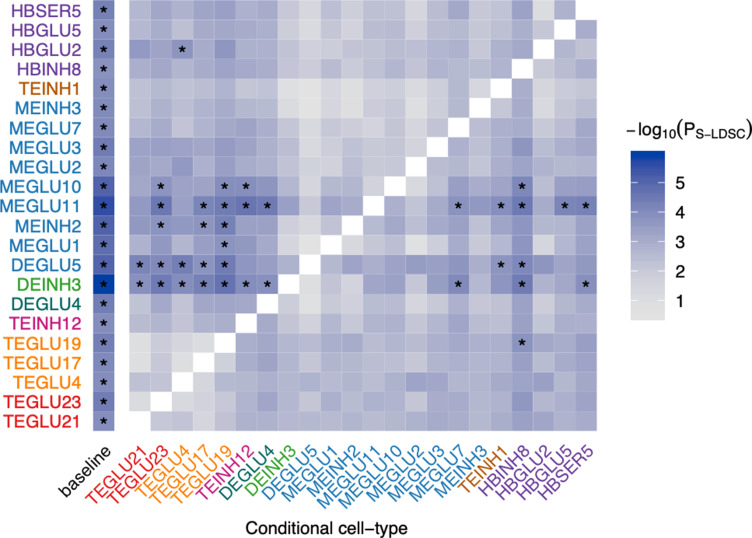

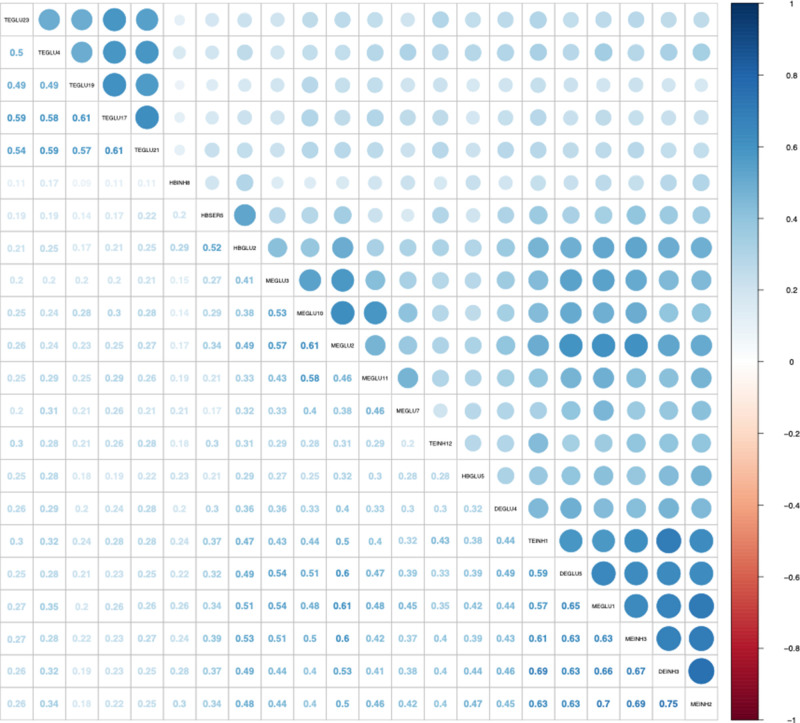

The 22 BMI GWAS-enriched cell types mapped to eight brain regions, namely the subthalamus, midbrain, hippocampus, thalamus, cortex, pons, medulla and pallidum (Figure 4a). To assess the extent to which shared transcriptional signatures could explain the enrichments across the 22 cell types, we clustered all cell types based on their genes’ ESμ values. Expectedly, midbrain cell types overall grouped by their neuroanatomical proximities and neurotransmitter types by midbrain, hindbrain, hippocampus/cortex clusters (Figure 4b). A notable exception was the DEINH3 cell type (isolated from the hypothalamus region and subsequently remapped to the subthalamic nucleus by Zeisel et al.) which grouped with the midbrain cell types. To further assess the transcriptional similarity between the enriched cell types, we computed enrichments conditioned on each prioritized cell type individually (Materials and methods). Contrary to our expectations, we found that none of the other cell types remained significant when conditioning on the top-ranked subthalamic cell type DEINH3 (Figure 4—figure supplements 1 and 2). Together these results indicate the brain cell types enriching for BMI GWAS signal, despite their neuroanatomical differences, share transcriptional signatures related to obesity, which current methods are not able to disentangle.

Figure 4. Neuroanatomical location and transcriptional similarity of brain cell types enriching for BMI GWAS variants.

(a) Sagittal mouse brain view showing the 22 BMI GWAS-enriched cell types. The first two letters in each cell type label denote the developmental compartment (ME, mesencephalon; DE, diencephalon; TE, telencephalon), letters three to five denote the neurotransmitter type (INH, inhibitory; GLU, glutamatergic) and the numerical suffix represents an arbitrary number assigned to the given cell type. (b) Circular dendrogram showing the similarity of all Mouse Nervous System dataset cell type expression specificity (ESμ) values. Dendrogram edges colored by taxonomy described in Zeisel et al., 2018. Expectedly, the cell types clustered according to their neuroanatomical origin. For clarity, only the labels of the 22 BMI GWAS enriched cell types are shown.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Conditional analysis of BMI GWAS-enriched mouse nervous system cell types conditional genetic prioritization analysis of BMI-prioritized cell types.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Correlation of mouse nervous system BMI GWAS-enriched cell types correlogram of cell type ESμ Pearson’s correlations.

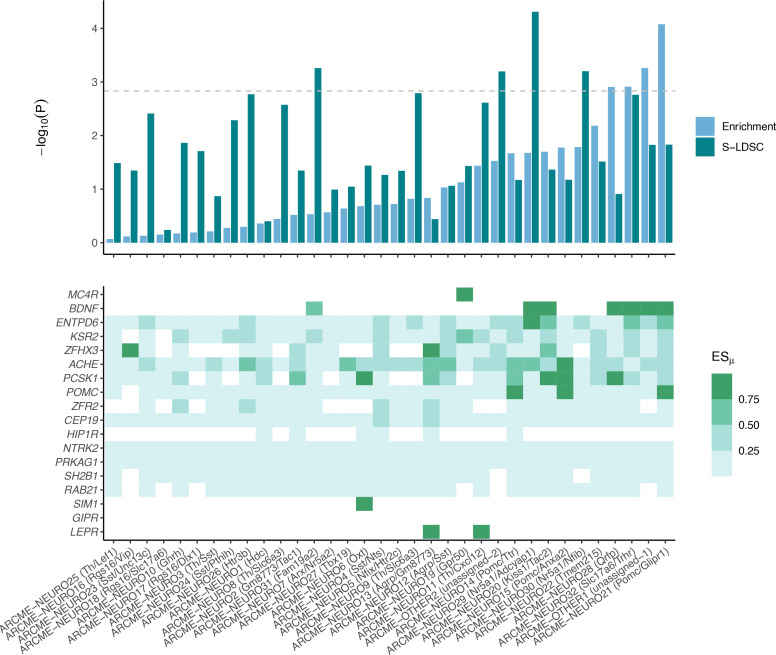

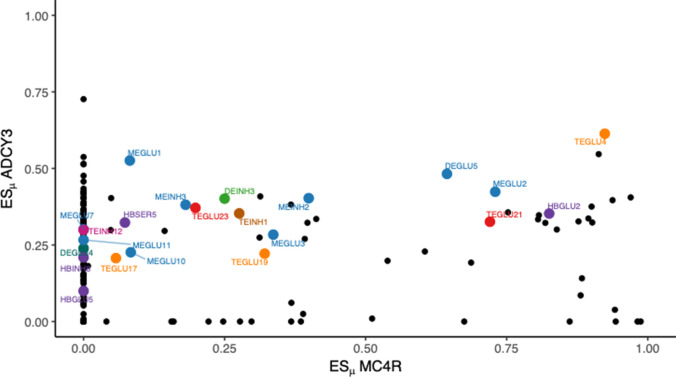

Ventromedial hypothalamic Sf1- and Cckbr-expressing cells enrich for BMI GWAS

The total number of cell types in the hypothalamus has been significantly underestimated (Kim et al., 2019a), therefore to assess whether the lack of enrichment for hypothalamic cell types was due to sparse sampling of hypothalamic cells in the Mouse Nervous System dataset, we computed enrichments for an additional set of 347 cell types sampled from the mediobasal hypothalamus (Campbell et al., 2017), the ventromedial hypothalamus (Kim et al., 2019a), the lateral hypothalamus (Mickelsen et al., 2019), the preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus (Moffitt et al., 2018) and the entire hypothalamus (Chen et al., 2017; Romanov et al., 2017). We identified four non-overlapping significantly enriched cell populations, namely a ventromedial hypothalamic glutamatergic cell type (ARCME−NEURO29; p=4.9×10−5) expressing Sf1 (ESμ=0.98 and ESμ=0.99) and Cckbr (cholecystokinin B receptor; ESμ=0.98, ESμ=0.95); a glutamatergic cell type from the lateral hypothalamus (LHA-NEURO20; p=4.9×10−5); and two cell types from the preoptic area of the hypothalamus (POA-NEURO21 and POA-NEURO66; p<1.0×10−4; Figure 5). Interestingly, ventromedial hypothalamic neurons have previously been implicated in control of both body fat mass and blood glucose levels; disrupted leptin signaling in Sf1-expressing ventromedial hypothalamic neurons renders mice more susceptible to diet-induced weight gain (Kim et al., 2011) and activation of ventromedial hypothalamic Sf1 neurons causes hyperglycemia (Meek et al., 2016). The two cell types also expressed Bdnf (ESμ=0.91, ESμ=0.99); mutations in BDNF and its receptor, NTRK2, is a known cause of monogenic obesity in humans and, in mice, BDNF signaling is required for normal energy homeostasis and glucoregulatory control (Kamitakahara et al., 2016). (Bdnf and Ntrk2 were also specifically expressed in TEINH12 cell type, a cholecystokinin (Cck)-expressing interneuron, enriched in the mouse nervous system analysis.) Noteworthy, clustering of the 347 hypothalamic cell populations based on their ESμ values resulted in clusters predominantly separating by cell type rather than by study or single-cell technique, indicating that CELLEX is relatively robust to batch effects (Figure 1—figure supplement 2).

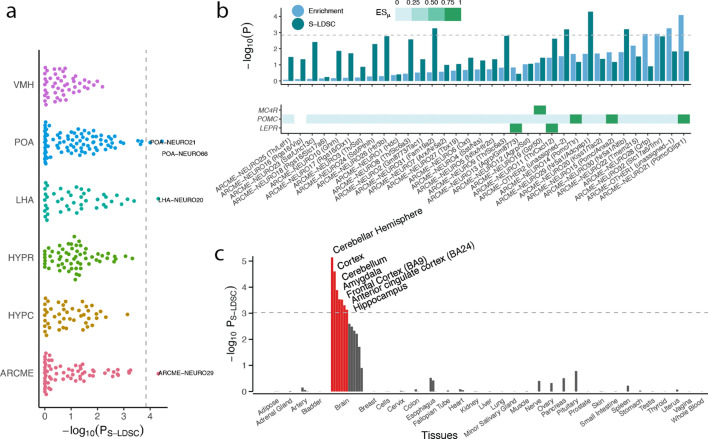

Figure 5. BMI GWAS enrichment across hypothalamic cells and human tissues.

(a) BMI GWAS enrichments across 347 hypothalamic cell types derived from studies of the Arc-ME (ARCME), the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), the lateral hypothalamus (LHA), the preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus (POA) and the entire hypothalamus (HYPR and HYPC). For each study, CELLEX and CELLECT were run individually, and subsequently all cell types were pooled and significance was determine based on Bonferroni correction (p<0.05/347). Four cell types were significantly enriched, namely POA-NEURO66 (Reln+; Moffitt et al., 2018) and POA-NEURO21 (Cck+/Ebf3+; Moffitt et al., 2018) from the preoptic area of the hypothalamus, ARCME-NEURO29 (Sf1+/Adcyap1+; Campbell et al., 2017) from the Arc-ME, and LHA-NEURO20 (Ebf3/Otb+; Mickelsen et al., 2019) from the lateral hypothalamus. (b) CELLECT and high-confidence obesity genes enrichments for neuronal cell populations in the Arc-ME (upper panel). Expression of Mc4r, Pomc and Lepr across Arc-ME neuronal populations, white squares means that the given gene is not expressed in at least 10% of the cells in the given cell population, non-white squares denote increasingly specific gene expression (lower panel). (c) CELLECT enrichment analysis of Genotype-Tissue Expression Consortium (GTEx) RNA-seq data. Orange bars denote significantly enriched tissues. The hypothalamus datasets’ metadata, CELLECT results and expression specificity values for the enriched cell types are available in Figure 5—source datas 1–3. The GTEx tissue annotations, CELLECT and high-confidence obesity genes enrichment results are available in Figure 5—source datas 10–12. POA, preoptic area of the hypothalamus; LHA, lateral hypothalamus; ARCME, arcuate nucleus and median eminence complex; S-LDSC, stratified-linkage disequilibrium score regression.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Arc-ME neuronal cell population enrichments and expression levels across obesity genes CELLECT and high-confidence obesity genes enrichments for neuronal cell populations in the Arc-ME (upper panel).

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Convergence of cell type prioritization based on common and rare variants.

Figure 5—figure supplement 3. High-confidence obesity genes enrichment in mouse nervous system cell types.

There was no significant enrichment in neurons expressing the Pomc gene, a neuropeptide-encoding gene with known coding mutations causing monogenic obesity in humans (4/5 of Pomc+ cell populations were nominally enriched; HYPR-NEURO24 (Pomc/Ttr), p=0.002; ARCME-NEURO21 (Pomc/Glipr1), p=0.01; HYPC-NEURO23 (Pomc/Cartp), p=0.03; HYPR-NEURO24 (Pomc), p=3.0×10−3). We next tested whether the paucity of significant enrichments across hypothalamic populations could be explained by either a limited ability of current hypothalamus scRNA-seq datasets to capture expression of relevant obesity genes or by a limited ability of CELLEX to correctly detect these genes as being specifically expressed in relevant cell types. Towards that end, we first compiled a set of 23 high-confidence obesity genes by merging a set of genes harboring protein-altering variants associated with obesity and with a set of genes implicated in monogenic forms of early-onset extreme obesity (both sets were obtained from Turcot et al., 2018; Figure 5—source data 4). We then assessed whether these high-confidence obesity genes were robustly- (expressed in ≥10% of the cells in a given population) and specifically (ESμ>0) expressed within relevant mediobasal hypothalamic arcuate-median eminence complex (Arc-ME) cell populations. By design, Pomc expression was detected in each of the three Pomc+ cell populations; the leptin receptor was detected in agouti-related peptide- and Trh/Cxcl12+ cell populations, two known leptin-sensing cell populations; and, finally, Mc4r was only detected and specifically expressed in the Gpr50+ cell population, which expressed several genes encoding receptors previously related to energy homeostasis (Campbell et al., 2017) (Materials and methods; Figure 5b, lower panel). CELLEX correctly identified these three genes as specifically expressed in these six cell types. Among the 23 high-confidence obesity genes, 20 were part of the Arc-ME dataset and 17 of them robustly and specifically expressed in at least one neuronal Arc-ME cell population (Figure 5—figure supplement 1; Figure 5—source data 5). Moreover, four cell populations were enriched for the high-confidence obesity genes ARCME-NEURO21 (Pomc/Glipr1+), ARCME-OTHER1 (a population of non-Arc-ME neurons potentially from the retrochiasmatic area), ARCME-NEURO32 (Slc17a6/Trhr+; neurons shown to be necessary and sufficient to induce satiety [Fenselau et al., 2017]) and ARCME-NEURO28 (Qrfp+; an orexigenic neuropeptide involved in energy homeostasis [Chartrel et al., 2016]; Bonferroni threshold p<0.05/34; Figure 5b, upper panel). We observed a high correlation between the high-confidence obesity gene set- and CELLECT results across the hypothalamus cell types (Pearson's rho = 0.50, p=1.1×10−5; Figure 5—source data 7). Moreover, we observed that ES values increased with increasing cell population heterogeneity; 16 out of the 18 ARCME-detected high-confidence obesity genes increased expression specificity when running CELLEX on all Arc-ME cells compared to ARCME neurons-only (Figure 5—source data 8). Finally, we found that across the Tabula Muris, Mouse Nervous System and Arc-ME datasets, 22 of the 23 high-confidence obesity genes were among the 25% most specifically expressed genes in at least one cell type (Figure 5—source data 9). Together these results indicate (a) that current hypothalamic single-cell data and our CELLEX methodology are of a sufficient quality to detect relevant cell populations, that (b) upcoming regional atlases with increased cellular heterogeneity will drive discovery of additional relevant cell populations and cell states for complex traits, and that (c) the BMI GWAS and high-confidence obesity genes’ approaches yield comparable results with a few notable exceptions (such as the Pomc/Glipr1+ population).

Finally, to assess whether hypothalamic transcriptional patterns may explain less genetic heritability compared to other brain areas in humans, we applied CELLEX and CELLECT on RNA-seq data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression Consortium and found that the hippocampus and several other brain areas exhibited stronger genetic enrichment signal than the hypothalamus (Figure 5c). In contrast, the high-confidence obesity genes enriched most strongly for the hypothalamus (p=3.9×10−4, FDR < 0.05; Figure 5—source data 12). These results support our previous observation that despite overlaps, obesity risk genes identified through rare-variant studies and genes near associated BMI GWAS signals may point to slightly different regions of the brain, an observation highlighting the importance of leveraging polygenic methodologies to identify cell types regulating susceptibility to common obesity.

Genes with known links to human obesity genes implicate the dorsal midbrain

As the high-confidence obesity genes have been identified independently of the BMI GWAS, we reasoned that we could use them to validate the cell types exhibiting the polygenic BMI GWAS signal. We computed the enrichment of the high-confidence obesity genes within all 265 mouse nervous system cell types and identified eight significantly enriched cell types (one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test, FDR < 0.05) of which two replicated cell types from the BMI GWAS analysis DEGLU5 and MEGLU2 from the anterior pretectal nucleus and the periaqueductal grey, respectively; p<1.2×10−4. The six remaining cell populations originated from areas implicated by the CELLECT analysis, namely the midbrain (MBDOP1, periaqueductal grey; MBDOP2, ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra; MEINH13, ventral/caudal midbrain; MEGLU14, the dorsal raphe nucleus), the hypothalamus (HYPEP3, ventromedial hypothalamus), and the medulla (HBSER4, nucleus raphe medulla). We observed a significant correlation between the high-confidence obesity genes enrichment- and CELLECT enrichment results (Pearson‘s R = 0.54, p=3.0×10−21; Figure 5—figure supplement 2a), further underscoring the validity of our findings, besides emphasizing that genes implicated in monogenic obesity or implicated by obesity-associated protein-altering variants tend to colocalize with BMI-associated GWAS loci (Figure 5—figure supplement 2b; Locke et al., 2015).

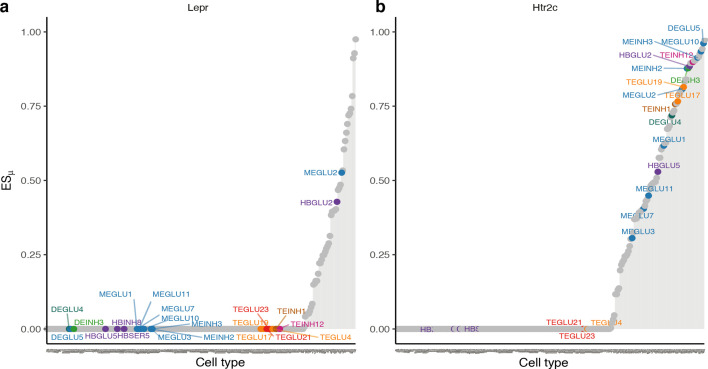

Interestingly, the leptin receptor, which regulates key energy homeostatic processes in the hypothalamus and when defective may cause syndromic obesity (Choquet and Meyre, 2011) was only specifically expressed in two out of the 22 BMI GWAS-enriched in the Mouse Nervous System dataset cell types, namely glutamatergic cells from the periaqueductal grey and anterior nucleus of the solitary tract (Figure 6a). By contrast, 17 of the enriched cell types expressed the serotonin receptor 5-Htr2c (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2C), a known regulator of energy and glucose homeostasis (Berglund et al., 2013) and a target for anti-obesity pharmacotherapy (Halford et al., 2011; Figure 6b). 5-Htr2c was most specifically expressed in the anterior pretectal nucleus (DEGLU5, ESμ=0.96), the cell type among our results which most specifically expressed Pomc (ESμ=0.41). Mice lacking the Htr2c in Pomc neurons are resistant to 5-Htr2c agonist Lorcaserin-induced weight loss (Berglund et al., 2013) (for ESμ plots of other selected genes, please refer to Figure 6—figure supplement 1).

Figure 6. Expression specificity of the leptin- and serotonin receptors across BMI GWAS enriched cell types.

(a) In the lipostatic model of obesity originally defined by Kennedy, 1953, circulating concentrations of the leptin hormone signal the amount of energy stored in fat cells to the brain. The plot shows gene ESμ (y-axis) for each cell type (x-axis, ordered by increasing values of expression specificity, ESμ) with BMI-prioritized cell types from the Mouse Nervous System dataset highlighted. In our analysis, only two of the 22 BMI GWAS enriched cell types specifically expressed the leptin receptor (MEGLU2, periaqueductal grey; and HBGLU2, nucleus of the solitary tract). (b) Seventeen of the 22 BMI GWAS enriched cell types specifically expressed the serotonin (5-htr2c) receptor. The strongest enrichment was observed for DEGLU5, a glutamatergic cell type from the anterior pretectal nucleus. ESμ, expression specificity.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. ESμ plot for selected genes ESμ plots for genes selected based on their suggested role in appetite regulation, energy homeostasis or obesity.

Together our results indicate that susceptibility to obesity conferred by common variants, while enriching for some hypothalamic cell types such as VMH Sf1-expressing neurons, is distributed across a mosaic of neuronal cell types of which a majority is involved in regulating integration of sensory stimuli, learning and memory.

Discussion

Here, we developed two scRNA-seq computational toolkits called CELLEX and CELLECT and applied them to scRNA-seq data from a total of 727 mouse cell types, from late postnatal and adult mice, to derive an unbiased map of cell types enriching for human genetic variants associated with obesity. In total, we identified 26 BMI GWAS-enriched neuronal cell types, which, in line with previous considerations (Grill, 2006), demonstrates that susceptibility to human obesity is likely to be distributed across multiple, mainly neuronal, cell types across the brain, rather than being restricted to a limited number of canonical energy homeostasis- and reward-related brain areas in the hypothalamus, midbrain and hindbrain. Among the enriched hypothalamic cell types, we identified VMH Sf1- and Cckbr-expressing neurons, which previously have been implicated in glucose and energy homeostasis. We show that while the polygenic enrichment signal is highly correlated with enrichment of high-confidence obesity genes, this alignment diverges for hypothalamic neuron populations (including Pomc-positive neurons) suggesting that common genetic susceptibility to obesity acts on a more broadly distributed set of neuronal circuits across the brain.

Processing of sensory stimuli and feeding behavior

Several of the enriched cell types localized to nuclei integrating sensory input and directed behavior. The inferior colliculus (implicated by MEGLU7, MEGLU10 and MEGLU11) and medial geniculate nucleus (MEINH3) process auditory input, the superior colliculus for translation of visual input into directed behavior (MEGLU1 and MEGLU6), the anterior pretectal nucleus processes somatosensory input (DEGLU5 and MEINH4), and the piriform cortex (TEGLU17) and anterior olfactory nucleus (TEGLU19) processing odor perception. The superior colliculus and anterior pretectal nucleus have both been implicated in predatory behavior (Shang et al., 2019; Antinucci et al., 2019) and project to the zona incerta, a less well-described brain area situated between the thalamus and hypothalamus that receives direct input from mediobasal hypothalamic Pomc neurons (Wei et al., 2018). In rats, lesioning of the zona incerta impairs feeding responses (Stamoutsos et al., 1979) while, conversely, in mouse models, optogenetic stimulation of GABAergic neurons in the zona incerta leads to rapid, binge-like eating and body weight gain (Zhang and van den Pol, 2017). Activation of projections from the hypothalamic preoptic nucleus (DEINH5; POA-NEURO21, POA-NEURO66) to the ventral periaqueductal gray (MEGLU2 and MBDOP1) induce object craving (Park et al., 2018), whereas pharmacological inactivation of the periaqueductal gray decreases food consumption (Tryon and Mizumori, 2018). Together, these findings suggest that susceptibility to obesity is enriched in cell types processing sensory stimuli and directing actions related to feeding behavior and opportunity.

Evidence supporting a key role of the learning and memory in obesity

Feeding is not an unconditioned response to an energy deficiency but rather reflecting behavior conditioned by learning and experience (Woods and Begg, 2015). We previously showed that genes in BMI GWAS loci enrich for genes specifically expressed in hippocampal postmortem gene expression data (Locke et al., 2015). In this work, we identified specific brain cell types supporting a role of memory in obesity. First, the parafascicular nucleus (DEGLU4), when lesioned in mice, reduces object recognition memory (Castiblanco-Piñeros et al., 2011). Second, the retrosplenial cortex (TEGLU4) is responsible for decisions made on past experiences (Hattori et al., 2019). Third, among the two enriched glutamatergic hippocampal cell types (TEGLU21 and TEGLU23), the latter expresses lipoprotein lipase as one of its top marker genes, an enzyme that causes weight gain when pharmacological or genetically attenuated in mice (Picard et al., 2014). Similarly, fasting inhibits activation of hippocampal CA3 cells (based on c-fos levels) in mice (Azevedo et al., 2019) and activation of glutamatergic hippocampal pyramidal neurons increases future food intake in rats most likely by perturbing memory consolidation related to the previous meal (Holahan and Routtenberg, 2011). In sum, our results provide further evidence that processes related to learning and memory play a key role in human obesity, and provide insights into specific cell types underlying hippocampal-centric susceptibility to obesity.

Limitations of our approach

Our results should be interpreted in the light of the underlying data and methodologies used to prioritize the cell types. First, the scRNA-seq data analyzed here were derived from late postnatal, adult and predominantly wild-type mice; future work is needed to assess the role of Pomc+, Agrp+ and Mc4r+ and other hypothalamic cell types during developmental stages and relevant obesogenic perturbations in human obesity (Zeltser, 2018). Second, the datasets used in this work should not be regarded as complete atlases because they are likely to miss relevant cell types such as Mc4r-positive neurons, which are known to play a key role in obesity. Third, one should keep in mind the overall assumption behind our approach, namely that in order for a given gene to confer genetic susceptibility for a given disease it needs to be expressed in the given cell type or tissue, where increasing expression is associated with increasing relevance. Thus, our approach is not designed to detect cell types in which reduced expression of a specific gene predisposes to obesity. Fourth, while studies have shown that the largest amount of variation is explained by organ rather than species differences (Brawand et al., 2011), that the majority of neuronal genes showed similar laminal patterning between human and mouse cortical samples (Zeng et al., 2012), and that broadly defined cell types were conserved between mouse and human (Hodge et al., 2019), analyses of human tissues may identify additional cell types critical to obesity development. Finally, given the dependence of CELLECT results on other cell types in the given datasets, we, generally, recommend running a ‘tiered’ prioritization strategy for CELLECT, where one preferably starts with analyzing body-wide or organ-wide transcriptional atlases and then turns to more tissue-centric datasets. While the high polygenicity of obesity and the inaccessibility of the human brain complicate approaches to further establish the enriched cell types’ relevance in human obesity, we believe that combinations of functional imaging techniques, postmortem single-nucleus analyses, enhancers to gene maps and fine-mapping of BMI GWAS loci will be crucial to better understand their role in human obesity.

Strategies for follow-up

Having identified GWAS-enriched cell populations only marks the start of the journey towards understanding how genetic variants render us susceptible to obesity. Two key questions marking the outset of this journey are; What is the subset of associated GWAS variants acting through the enriched cell populations and what are the regulatory elements and effector genes (candidate causal genes) through which these variants exert their effects? And, how is the given cell population affecting physiology and downstream risk of obesity? Given that CELLECT is not specifically designed to identify effector genes but rather intended to identify cell populations enriching for GWAS signal, we suggest to address these questions by focusing on (a) identifying the set of candidate causal variants and effector genes conferring risk through the focal cell population, and (b) directly validating the relevance of the focal cell population under relevant physiological and pharmacological conditions.

Fulco et al. recently proposed an elegant model to map enhancers to effector genes in a given cell type (Fulco et al., 2019). Their so-called activity-by-contact model leverages single-cell chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity data to identify cell type-specific enhancers and their target genes. For the focal cell population, such an enhancer-gene map, when integrated with credible sets of fine-mapped GWAS variants, would bring forward a set of testable hypotheses on how a set of candidate causal variants act through a set of specific enhancers and effector genes to impact obesity (or any other disease of interest). Additional confidence could be gained by adding in computational gene prioritization approaches such as DEPICT or MAGMA, for example by up-weighing effector genes that are predicted to be functionally similar to candidate effector genes in the other relevant cell populations. Given species-specific differences in gene regulation, these analyses would need to be performed in animal models with at least partly conserved gene regulatory architectures, human postmortem brain samples (ideally obtained from relevant cases and controls) and/or in induced pluripotent stem cells models (ideally selected from individuals with relevant polygenic backgrounds).

Given the challenges typically encountered in the journey aimed at identifying causal variants and effector genes underlying obesity (for successful examples see Claussnitzer et al., 2015; Smemo et al., 2014), we suggest in parallel to leverage transgenic animal models to directly assess the relevance of the focal cell in obesity. Given that CELLEX provides marker genes specifically marking the focal cell population and that all enriched cell populations were of neuronal origin, transgenic animal model techniques such as designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD)-based chemogenetic tools for activation or inhibition of neurons, transgenic techniques for cell ablation, and fiber photometry techniques for real-time monitoring the impact of relevant physiological environments or pharmacological treatments on the focal cell population, are well-positioned to provide relevant insights into the role of the given cell type in the control of energy homeostasis.

Relevance to human obesity

Despite these limitations, several lines of evidence suggest that the cell types identified herein to be enriched for BMI GWAS signal are relevant to human obesity. First, weight gain is the most pronounced side effect of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation used to treat Parkinson patients (Limousin and Foltynie, 2019), an adverse side effect that may involve the DEINH3 cell type mapping to the subthalamic nucleus. Second, lorcaserin (Belviq), an anti-obesity drug, acts on the 5-HTR2C receptor to enhance serotonin signaling. Third, at the genetic level BMI is significantly correlated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Demontis et al., 2019), and growing evidence points to links between ADHD and eating disorders. For example, lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse), a medication used to treat ADHD, is also used to treat binge eating (McElroy et al., 2016), while the ADHD medication methylphenidate (Ritalin) is known to reduce appetite (Faraone et al., 2008). These pharmacological observations suggest that the shared heritability of BMI and ADHD may involve pleiotropic gene variants acting through dorsal midbrain pathways. Fourth, genetic predisposition to obesity is protective to feelings of worry (Millard et al., 2019), supporting our findings that these two traits are potentially acting through overlapping cell types in the dorsal midbrain. Finally, BMI variants associated with BMI in a GWAS conducted in Japanese individuals enriched most highly for enhancers active in the hippocampus (Akiyama et al., 2017) and maternal obesity is associated with reduced total hippocampal volume in reduced CA3 volume in children (Page et al., 2018). Together these observations support a model in which integration of sensory signals, the dopamine system and memory are likely to play key roles in regulating susceptibility to obesity.

In conclusion, our results implicate specific brain nuclei regulating integration of sensory stimuli, learning and memory in human obesity and provide testable hypotheses for mechanistic follow-up studies. Our methodological framework provides a salient example of how human genetics data can be integrated with murine scRNA-data to identify and map components of brain circuits underlying obesity. We provide easy to use computational toolkits, CELLECT and CELLEX, which we envision will greatly facilitate future functional interpretation of genetic association data.

Materials and methods

GWAS

For our primary analysis we obtained BMI GWAS summary statistics performed in UK Biobank participants (Nmax = 457,824) (Loh et al., 2018). To examine the robustness of our results to changes in GWAS cohort size, we performed secondary analyses on BMI GWAS summary statistics from two meta-analyses described in Yengo et al., 2018 Nmax = 795,640, UK Biobank and GIANT cohorts and Locke et al., 2015 (Nmax = 322,154; European subset). We note that these two studies include individuals genotyped on custom array chips (Illumina Metabochip), which violate certain assumptions of S-LDSC, however, we show that this has a negligible effect on our results. Figure 2—source data 1 provides the full list of GWAS summary statistics analyzed here. We used the script ‘munge_sumstats.py’ (LDSC v1.0.0, see URLs) to prepare all GWAS summary statistics. All prepared statistics were restricted to HapMap3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), excluding SNPs in the major histocompatibility complex region (chr6:25Mb-34Mb).

Single-cell RNA-seq datasets

For the Tabula Muris dataset (Tabula Muris Consortium et al., 2018; SmartSeq2 protocol) cell types were defined as unique combinations of cell ontology and organ annotation (for example, ‘Lung-Endothelial_cell’) resulting in n = 115 cell type annotations (of which one was defined as neuronal). For the Mouse Nervous System dataset (Zeisel et al., 2018; 10x Genomics protocol), we used the ‘ClusterName’ option as cell type annotations (n = 265, of which 214 were defined as neuronal). For the hypothalamus, we leveraged datasets from six studies:

Arc-ME: Arcuate nucleus and median eminence complex (Campbell et al., 2017 DropSeq protocol). We used the ‘Subcluster’ annotations (n = 65, of which 34 were defined as neuronal).

POA: Preoptic area (Moffitt et al., 2018 10x Genomics protocol) dataset. We used the ‘Non-neuronal.cluster.(determined.from.clustering.of.all.cells)’ annotations for non-neuronal cell types (n = 21) and the ‘Neuronal.cluster.(determined.from.clustering.of.inhibitory.or.excitatory.neurons)’ annotation for neuronal cell types (n = 66).

LHA: Lateral Hypothalamic Area (Mickelsen et al., 2019, 10x Genomics protocol). We used the ‘dbCluster’ annotations (n = 43, 30 neuronal).

VMH: Ventromedial Hypothalamus (Kim et al., 2019a SMART-seq and 10x Genomics protocols). We used the ‘smart_seq_cluster_label’ annotations for the SMART-seq dataset (n = 48, of which 40 were defined as neuronal) and the ‘tv_cluster_label’ annotation for the 10x Genomics dataset (n = 29, all neuronal).

HYPC: Pan hypothalamus (Chen et al., 2017, DropSeq protocol). We used the ‘SVM_clusterID’ annotations (n = 45, 34 neuronal).

HYPR: Pan hypothalamus (Romanov et al., 2017, Fluidigm C1 protocol) dataset, we used the ‘level1 class’ annotation for non-neuronal populations (n = 6) and the ‘level2 class (neurons only)’ annotation for neurons (n = 54).

Code to download and reproduce preprocessing of all datasets are available via GitHub (see URLs). Figure 2—source data 2, Figure 3—source data 1 and Figure 5—source data 1 list cell type annotations, the number of cells per cell type and relevant metadata for the Tabula Muris, Mouse Nervous System and hypothalamus datasets (for each hypothalamus dataset we list the cell type labels used in this study as well as the cell type labels used in the original studies).

Single-cell RNA-seq data pre-processing

For each dataset, we began with a matrix of gene expression values. We normalized expression values to a common transcript count (with n = 10,000 transcripts as a scaling factor) and applied log-transformation (). Next we excluded ‘sporadically’ expressed genes following the approach described in Skene et al., 2018 using a one-way ANOVA with cell type annotations as the grouping factor and excluding all genes with p>10−5. We mapped mouse genes to orthologous human genes using Ensembl (v. 91), keeping only 1–1 mapping orthologs.

Cell type labels

For the Mouse Nervous System dataset, we used (Zeisel et al., 2018) cell type annotations: the first two letters in each cell type abbreviation denote the developmental compartment (ME, mesencephalon; DE, diencephalon; TE, telencephalon), letters three to five denote the neurotransmitter type (INH, inhibitory; GLU, glutamatergic) and the numerical suffix represents an arbitrary number assigned to the given cell type. Likewise, for the Tabular Muris dataset, we used the cell type labels as reported in their paper. For the six hypothalamic datasets, we added a label to allow the reader to more easily understand, from which part of the hypothalamus a given cell type was sampled in the original study (‘ARCME’, arcuate nucleus median eminence complex; ‘HYPC’, hypothalamus Chen et al., 2017; ‘HYPR’, hypothalamus Romanov et al., 2017; ‘LHA’, lateral hypothalamus; ‘POA’, preoptic area; ‘VMH’, ventromedial nucleus) and the cell type it was annotated to in the original work.

Mouse nervous system neurotransmitter annotation

We used the ‘Neurotransmitter’ column of the cell type metadata (from the mousebrain.org website) to group neuronal cell types into six neurotransmitter classes (transmitter listed in parenthesis): ‘excitatory’ (glutamate), ‘inhibitory’ (GABA or glycine), ‘monoamines’ (adrenaline, noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin), ‘acetylcholine’ (acetylcholine), ‘nitric oxide’ (nitric oxide) and ‘undefined’ for neurons not matching these classes or without neurotransmitter data. When cell types were annotated with multiple transmitter classes in the ‘Neurotransmitter’ column (e.g. glutamate and adrenaline), excitatory or inhibitory class took precedence in our assignment.

CELLEX expression specificity

See Appendix 2 for a discussion on ES calculations, assumptions and limitations. CELLEX version 1.0.0 was used to produce all results reported in this manuscript. See URLs for a ready-to-use Python implementation of CELLEX. We calculated expression specificity separately for the Tabula Muris, the Mouse Nervous System and each of the hypothalamus datasets. Cell type expression specificity weights (ESw) were calculated using four ES metrics her referred to us as Gene Enrichment Score (GES) (Zeisel et al., 2018), Expression Proportion (EP) (Skene et al., 2018), Normalized Specificity Index (NSI) (Dougherty et al., 2010) and Differential Expression T-statistic (DET). The mathematical formulas for the ES metrics can be found in Appendix 2. For each ES metric, we separately computed gene-specific ESw values before averaging them into a single ES estimate (ESμ) using the following steps:

For each cell type we determined the set of specifically expressed genes, , by testing the null hypothesis that a gene is no more specific to a given cell type than to cells selected at random. We computed empirical P-values of ES weights by comparing observed weights for cell type c to ‘null’ weights obtained by sampling the dataset’s cell type annotations (including annotations from cell type c without replacement).

-

For each cell type we calculated ESw* representing the genes’ score of being specifically expressed in a given cell type. We assumed that each cell type has a set of specifically expressed genes exhibiting a linearly increasing score reflecting its expression specificity. We modeled this linearity assumption by rank normalizing ESw for genes, g, in :

Note that ESw* are scaled such that .

For each cell type, we calculated ESμ, representing a gene’s score of being specifically expressed in a given cell type, by taking the mean ESw* across all ES metrics (we here assume equal weighing of ES metrics).

We use ‘ES genes’ to denote the set of genes with ESμ>0 for a given cell type. Hence, all genes being part of at least one for a specific cell type will be included in the set of ES genes for this cell type. Figure 3—source data 3 and Figure 5—source data 3 show the number of ES genes for the BMI GWAS-enriched Mouse Nervous System and hypothalamus cell types. We note that ES genes include genes that were not only strictly specifically expressed (only expressed in the cell type) but also those that were loosely specifically expressed (i.e. have higher expression in the cell type). All cell type enrichment results were computed based on the ESμ estimates. CELLEX can take count data as well as transcripts per million-normalized data as input.

Expression specificity of known marker genes

First, to validate that our ES approach was able to delineate cell type-specific genes, we, for each of the four ES metrics, computed ESw estimates across four cell types with genes known to be specifically expressed in these cell types, namely hepatocytes (Apoa2), pancreatic alpha-cells (Gcg), striatum medium spiny neurons (Drd2) and mediobasal hypothalamic agouti related peptide (Agrp)-expressing neurons (Agrp). The four ESw metrics and the combined ESμ metric correctly ranked the relevant genes at the top (Figure 1d). Conversely, plotting ESμ values for these four genes across all cell types revealed that hepatocytes and alpha-cells exhibited the highest ESμ for Apoa2 and Gcg, respectively, and that medium spiny neurons and Agrp-positive neurons exhibited the highest ESμ for Drd2 and Agrp, respectively (Figure 1e).

CELLECT genetic prioritization of trait-relevant cell types

See Appendix 1 for adiscussion on assumptions and limitations. CELLECT version 1.0.0 was used to produce all results reported in this manuscript. See URLs for a ready-to-use Python implementation of CELLECT. Throughout this paper, we report CELLECT cell type prioritization results using S-LDSC, as this model has been shown to produce robust results with properly controlled type I error (Finucane et al., 2018). Cell type prioritization results using MAGMA (de Leeuw et al., 2015) can be found in Figure 3—figure supplement 3b and Figure 3—source data 7.

Stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression

We used stratified S-LDSC (v. 1.0.0, URLs) to prioritize cell types after transforming cell type ESμ vectors into S-LDSC annotations. Running S-LDSC with custom annotations follows three steps: generation of annotation files, computation of annotation LD scores and fitting of annotation model coefficients. We created annotations for each cell type by assigning genes’ ESμ values to genetic variants utilizing a 100 kilobase (kb) window of the genes’ transcribed regions. Fulco et al. showed that most enhancers are located within 100 kb of their target promoters (Fulco et al., 2019). When a variant overlapped with multiple genes within the 100 kb window, we assigned the maximum ESμ value. The relatively large window size was chosen to capture effects of nearby regulatory variants, as the majority of trait-associated variants have been shown to be located in non-coding regions (Gusev et al., 2014). Our results were robust to changes in window size (data not shown), consistent with previous work (Skene et al., 2018; Finucane et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019b). Following the recommendation in Finucane et al., 2018, we constructed an ‘all genes’ annotation for each expression dataset, by assigning the value 1 to variants within 100 kb windows of all genes in the dataset. We used hg19 (Ensembl v. 91) as the reference genome for genetic variant and gene chromosomal positions. When constructing annotations, we used same 1000 Genomes Project SNPs (Abecasis et al., 2012) as in the default baseline model used in S-LDSC. Next, we computed LD Scores for HapMap3 SNPs (Altshuler et al., 2010) for each annotation using the recommended settings.

For the primary cell type prioritization analysis, we jointly fit the following annotations: (i) the cell type annotation; (ii) all genes annotation (iii) the baseline model (v1.1). For cell type conditional analysis (Figure 4—figure supplement 1) we added (iv) the cell type annotation conditioned on when fitting the model.

We ran S-LDSC with default settings and the workflow recommended by the authors. We reported p-values for the one-tailed test of positive association between for trait heritability and cell type annotation ESμ. We note that the correlation structure among ESμ for cell type annotations can lead to a distribution of p-values that is highly non-uniform (Finucane et al., 2018). Highly significant p-values occur due to correlated cell types with true signal, whereas cell types negatively correlated with the true signal have p-values near 1. For all results, we used Bonferroni correction within a trait and dataset to control the FWER. We report the regression effect size estimate for each cell type (source data: ‘Coefficient’ column), which represents the change in per-SNP heritability due to the given cell type annotation, beyond what is explained by the set of all genes and baseline model. We also report standard errors of effect sizes (‘Coefficient std error’ column), computed using a block jackknife (Finucane et al., 2015). Finally, we report the ‘annotation size’ for each cell type, that measures the proportion of SNPs covered by the cell type annotation (0 means no SNPs were covered by the annotation; 1 means all SNPs were covered). Annotation size was computed as the mean of the cell type annotation.

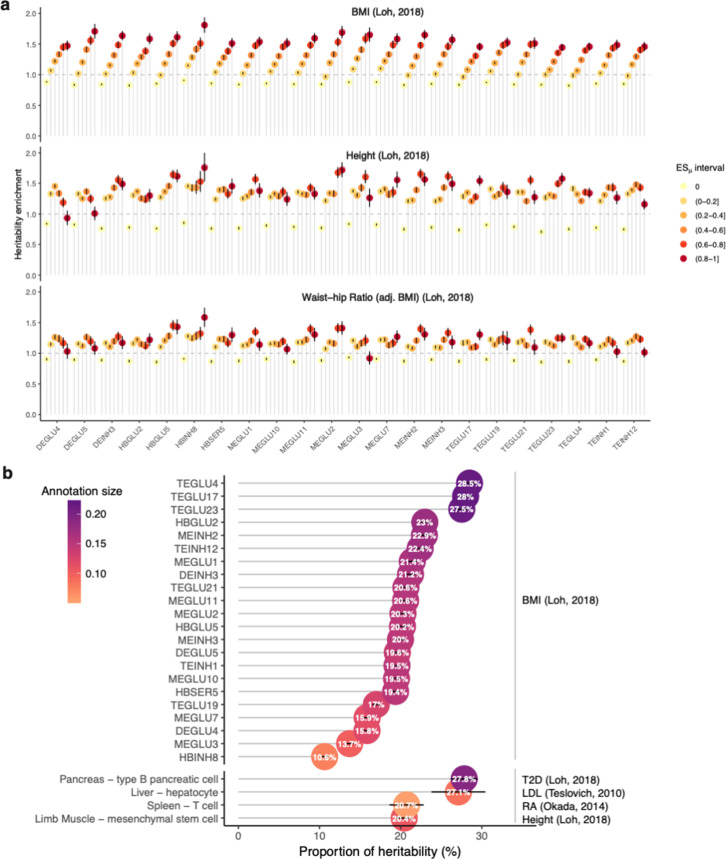

S-LDSC heritability analysis

All S-LDSC heritability analyses and reported effect size estimates were obtained on the observed heritability scale, with the exception of heritability estimates for case-control traits shown in the barplots of Figure 2a and Figure 3b. Here, we report heritability estimates on the liability scale using population prevalences listed in Figure 2—source data 1. (The liability scale is needed when the aim of heritability analysis is to compare heritability estimates across traits. On a liability scale the case-control trait is treated as if it has an underlying continuous liability, and then the heritability of that continuous liability is quantified.) To interpret the heritability explained by our continuous-valued ESμ cell type annotations, we estimated the heritability of each ESμ quintile. We modified the script ‘quantile_M.pl’ (from the LDSC package) to compute heritability enrichment for five equally spaced intervals of the cell types ESμ annotations: (0–0.2), (0.2–0.4), (0.4–0.6), (0.6–0.8), (0.8–1), as well as the interval including zero values only ([0–0]).

MAGMA cell type prioritization

To assess the robustness of the SNP-level S-LDSC cell type prioritization, we used an alternative gene-level approach inspired by Skene et al., 2018 and tested the association of gene-level BMI association statistics with cell type ESμ using MAGMA (v1.07a) (de Leeuw et al., 2015). MAGMA was run with default settings to obtain gene-level association statistics calculated by combining SNP association p-values within genes and their flanking 100 kb windows into gene-level Z-statistics, while accounting for LD (computed using the 1000 Genomes Project phase 3 European panel; Abecasis et al., 2012). Gene-level Z-statistic were corrected for the default MAGMA covariates: gene size, gene density (a measure of within-gene LD) and inverse mean minor allele count, as well the log value of these variables. Next, we used the R statistical language to fit a linear regression model using MAGMA gene-level Z-statistics as the dependent variable and cell type ESμ as the independent variable. We report cell type prioritization p-values (from the linear regression model) as the positive contribution of cell type ESμ regression coefficient to BMI gene-level Z-statistics (one-sided test).

Cell type geneset enrichment analaysis

To assess cell type enrichment of genesets associated with obesity, we tested if members of the obesity geneset exhibited higher expression specificity (ESμ) in a given cell type than non-members of the geneset (all other genes in the dataset). Specifically, we used a Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction to obtain one-sided geneset enrichment p-values. We controlled the FWER using the Bonferroni method calculated over all cell types and the rare variant obesity geneset tested. As a precaution against unknown confounders, we also computed empirical p-values by permuting the expression specificity gene labels 10,000 times to obtain ‘null genesets’ of identical size, and obtained near-identical results (data not shown). We obtained genes with rare coding variants associated with obesity (n = 13 genes) and genes implicated in early onset- and extreme obesity from Turcot et al. Table 1 and Supplementary Table 21, respectively. We combined these genes into a single set of 23 high-confidence obesity genes.

Cell type gene co-expression networks

We identified cell type gene co-expression networks using robust weighted gene correlation network analysis (rWGCNA) framework proposed by Langfelder and Horvath, 2008. To identify gene co-expression networks (or gene modules) operating within a cell type, the input to WGCNA is expression data for individual cell types. Briefly our framework consisted of the following steps:

We normalized the raw expression values to a common transcript count (with n = 10,000 transcripts as a scaling factor), log-transformed the normalized counts (log(x+1)), and centered and scaled each gene’s expression to Z-scores. Cell clusters with fewer than 50 cells were omitted, and genes expressed in fewer than 20 cells were removed. We then used PCA to select the top 5000 highly loading genes on the first 120 principal components. We mapped mouse genes to orthologous human genes using Ensembl (v. 91), keeping only 1–1 mapping orthologs.

We then used hierarchical clustering and hybrid tree cutting algorithms to identify gene modules. Module eigengenes, which summarize module expression in a single vector, were computed and used to identify and merge highly correlated modules.

Finally, we computed gene-module correlations (kMEs), a measure of gene-module membership, filtering out any genes which were not significantly associated with their allocated module after correcting for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Genetic prioritization of cell type co-expression networks

Genetic prioritization of WGCNA gene modules followed the same framework as for prioritizing cell types. That is, we used S-LDSC controlling for the baseline and ‘all genes’ annotations. Gene modules annotations were constructed by assigning the module genes’ kME values to variants within a 100 kb window of the genes’ transcribed regions. We restricted modules to contain at least 10 genes and at most 500 genes (removing 8 out of 571 modules), because S-LDSC is not well-equipped for prioritizing annotations that span very small proportion of the genome, and unspecific modules with a large number of weakly connected genes may have limited biological relevance.

Co-expression network visualizations

To create the network visualization of the cell type rWGCNA gene modules (Figure 3—figure supplement 2b), we computed the Pearson’s correlation between module kME values (a measure of gene-module membership) and generate a weighted graph between modules using the positive correlation coefficients only. To create the network visualization of the M1 gene module (Figure 3—figure supplement 2c), we computed the Pearson’s correlation between genes within the module, using expression data from the cell type in which the module was identified (MEINH2). We then generate a weighted graph between genes using the positive correlation coefficients only. We then mapped MAGMA BMI gene-level Z-statistics (calculated using 100 kb windows, as described above) onto the network as node sizes. All networks were visualized using the R package ‘ggraph’ with weighted Fruchterman-Reingold force-directed layout.

Cell type enrichment of co-expressed gene networks

To assess if gene modules were enriched in the expression specific genes of specific cell types, we tested if module gene members exhibited higher expression specificity (ESμ) in the given cell type than non-members of the module (all other genes in the dataset). We obtained one-sided enrichment p-values using the Mann-Whitney U test. We controlled the FDR by using the Bonferroni method calculated over gene modules tested.

Tests for confounding factors and null GWAS construction

In order to test for technical bias in CELLECT genetic enrichment scores, we prioritized cell types using GWAS based on randomly distributed phenotypes ('null GWAS'). We computed 1000 GWAS based on 1000 Genomes Project Phase three genotyping data and simulated Gaussian phenotypes randomly drawn from a N(0,1) distribution with no genetic bias. We then performed genetic prioritization across 115 cell types in the Tabula Muris dataset using CELLECT with S-LDSC for each null GWAS.

S-LDSC prioritization p-values, which for null GWAS tend toward a uniform distribution, showed a slight enrichment for P-values closer to 1, and a slight depletion close to 0. To verify that CELLECT genetic prioritization p-values were not correlated with technical factors, we computed the Pearson correlation between the -log10(S-LDSC p-value) for a cell type and the number of cells, median number of genes expressed, and median number of UMIs, respectively for each null GWAS. We used a two-sided t-test to identify significant deviations from the expected mean correlation of zero.

The genotype-tissue expression consortium data and analysis

The genotype-tissue expression version eight gene expression read counts were obtained from their portal (download date 6 May 2020). An initial set of 17,382 RNA-seq samples were filtered on quality indicators using the same cutoffs as in GTEx Consortium et al., 2017. Next, to identify and remove outliers, we used an approach similar to that of Wright et al., 2014: within each tissue-type (SMTSD annotation), we computed the mean Pearson correlations of each sample to the others. We then removed any samples whose expression profile had a mean correlation falling below the first quartile by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range within that tissue-type, leaving 16,027 samples from 946 donors. Genes were then filtered, again using the cutoff from GTEx Consortium et al., 2017, that is keeping genes with at least six reads in at least 10 samples. To ensure positive expression values as required by CELLEX, and given that common batch-correction techniques typically incur partly negative expression values, we did not perform batch correction. The filtered gene read counts were normalized within each broad tissue-type (SMTS annotation) using the DESeqDataSetFromMatrix(), estimateSizeFactors() and counts() commands from the DESeq2 R package (v1.22.2) (Love et al., 2014). Finally, normalized counts were log-transformed (log2(x+1)), gene version number suffixes were removed from the GENCODE gene names, and samples were grouped by SMTSD annotations for downstream analysis with CELLEX and CELLECT.

Code availability

CELLECT toolkit is available at Timshel, 2020; https://github.com/perslab/CELLECT (copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/timshel-2020). CELLEX is available at https://github.com/perslab/CELLEX. Open source software implementations of CELLECT and CELLEX will be made available upon publication. Code to reproduce analyses, figures and tables for this manuscript is available at https://github.com/perslab/timshel-2020.

URLs

Robust WGCNA pipeline: https://github.com/perslab/wgcna-toolbox

Genotype-Tissue Expression Consortium portal: https://gtexportal.org/home/datasets

Acknowledgements

Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is an independent Research Center, based at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark and partially funded by an unconditional donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (www.cbmr.ku.dk) (Grant number NNF18CC0034900). THP acknowledges the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant number NNF16OC0021496) and the Lundbeck Foundation (Grant number R19020143904). PNT acknowledges the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science for the Elite Research PhD scholarship.

We gratefully acknowledge Diego Calderon for helpful discussions on genetic prioritization models; Steven Gazal for support with LDSC heritability enrichment; Christiaan de Leeuw for support on MAGMA; Stephen Quake, Spyros Darmanis and the Biohub team for providing pre-publication access to the Tabula Muris dataset; Michael W Schwartz, Thorkild IA Sørensen, Lars Ängquist and Dylan M Rausch for helpful inputs on neuroendocrinology and obesity; Tobias Stannius, Ben Nielsen, Tobi Alegbe, Petar V Todorov and Liubov Pashkova for improving the CELLECT and CELLEX software.

Appendix 1

CELLECT cell type prioritization

Introduction

Here we discuss the detailed methods and limitations of the CELLECT framework.

The relevance of using mouse scRNA-seq datasets

Our BMI cell type prioritization analysis was performed using mouse scRNA-seq atlases. We here discuss the relevance of using mouse scRNA-seq datasets to define cell types for genetic prioritization for complex human traits.

Previous studies have compared the conservation of tissue gene expression. Brawand et al., 2011 used RNA-seq expression data across multiple organs (cortex, cerebellum, heart, kidney, liver, and testis) and 10 mammalian species (incl. human) and found the largest amount of variation was explained by organ rather than species differences.

Previous studies have assessed the convergence of mouse and human central nervous system (CNS) gene expression using gene co-expression analysis (Hawrylycz et al., 2015; Kelley et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2010) and found weaker conservation of glial co-expression modules than neuronal co-expression modules. In situ hybridization studies have reported that the majority of genes (79%) showed similar cortical laminar patterning (Zeng et al., 2012). Along those lines, recent scRNA-seq data from mouse and human midbrain found that cell types and gene expression levels were generally conserved across species (La Manno et al., 2016).

The current most extensive study of CNS cell type conservation compared single-nucleus expression data from human and mouse cerebral cortex (Hodge et al., 2019) and found that broadly defined cell types were conserved between mouse and human. However, they identified important differences between cell type proportions and expression of specific genes, including cell type marker genes exhibiting up to 10-fold expression differences.

In conclusion, although critical differences between mouse and human CNS gene expression data have been identified, the broad expression patterns are likely to be conserved. Moreover, glial cell types are more likely to exhibit weaker conservation compared to neuronal cell types. We believe our genetic prioritization of likely etiologic cell types is more likely to suffer from false negatives (cell types not prioritized because of lack of relevant human expression data) rather than false positives (spuriously enriched cell types among our positive results).

Choice of window size and position for connecting SNPs and genes

An important step in the CELLECT pipeline is assigning gene ESμ values to SNPs. As the majority of trait-associated SNPs are located in non-coding regions (Gusev et al., 2014), it is desirable to select a window size that maps the majority of regulatory GWAS variants to their proximal genes. Although our results were largely robust to changes in window size and consistent with previous work (Finucane et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019a; Skene et al., 2018), we note that the SNP-to-gene mapping remains a critically important step that should be updated in subsequent versions of CELLECT.

In this work, we used the same window size as used in Finucane et al., 2018, that is, assigning genes’ ESμ values to SNPs within a 100 kb window on either side of a gene’s transcribed regions. A recent large eQTL analysis in blood from >31,000 individuals found that 92% of the lead cis-expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) SNPs mapped within 100 kb of the gene (Võsa et al., 2018), suggesting that our mapping is likely to capture the majority of cis-regulatory variants. Consistent with this, Gasperini et al., 2018 used CRISPR/Cas9 followed by scRNA-seq to identify CRISPR/Cas9-induced eQTLs from >47,000 human cell line cells and found that regulatory variants were separated from the TSS of their target genes by a median distance of 34.3 kb. Finally, work by Fulco et al. reports that most enhancers are located within 100 kb of the target promoters (Fulco et al., 2019).

Limitations of CELLECT

Linear relationship between expression specificity and trait heritability

The overall assumption behind our approach is that in order for a disease to manifest in a given cell type the set of disease causal genes must be active and expressed in the given cell type. In other words, we assume that high/increased expression and not decreased/lack-of expression of a gene results in disease. This is a strong assumption to make about complex traits and it does not hold for all diseases (e.g. cancer).

Our model assumes a linear effect of cell type expression specificity and trait heritability. Although this assumption may not always hold, it appears to be reasonable in the continuous annotations that we analyzed (Appendix 4—figure 1).

We leave it for future work to explore non-linear relationships between expression specificity and trait heritability, and to investigate the effects of specificity for decreased or lack-of gene expression.

Genetic architecture

The approach assumes that a cell type is etiologic for a particular disease if and only if genetic variants near genes with high expression specificity in the cell type are enriched for heritability. Moreover, the CELLECT cell type prioritization assumes a polygenic trait architecture. Consequently, our approach is unlikely to yield relevant results for traits driven by rare genetic mutations (not covered by GWAS) or traits where the heritability is not mediated by transcriptional differences (i.e. changes related to other molecular modalities such as proteins, posttranslational modifications or the microbiome).

Common variation