Abstract

COVID-19 is continuing as a big challenge for the globe and several types of research are continued to find safe and effective treatment and preventive options. Although there is a lack of conclusive evidence of their benefit, there is worldwide controversy to use anti-malarial drugs, hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, for the treatment of COVID-19. FDA issued an emergency use authorization to the use of these drugs for the treatment of COVID-19. On the contrary to the FDA, the European Medicines Agency has warned against the widespread use of these drugs to treat COVID-19. Finally, the WHO declared that clinical trials on these drugs are halted after the devastating findings of the study published in the medical journal called The Lancet. Against this fact, there are several rumors about the irresponsible use of these drugs in Africa for the treatment of COVID-19. This work aimed to review the off-label use of these drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 in African countries against WHO recommendation. Data on the use of these drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 in African countries were searched from credible sources including Scopus, PubMed, Hindawi, Google Scholar, and from local and international media. The study showed that many African countries have already approved at the national level to use these drugs to treat COVID-19 by opposing WHO warnings. In addition to this, falsified and substandard chloroquine products started to emerge in some African countries. The health sectors of the African government should critically compare the risks and benefits before using these drugs. The WHO and African drug regulatory organizations should intervene to stop the off-label use practice of these drugs against the licensed purpose and distribution of falsified and substandard products in the continent.

Keywords: COVID-19, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, off-label, Africa

Introduction

Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine

Chloroquine and its derivative hydroxychloroquine are old drugs used for the treatment of malaria and inflammatory diseases, and even have potential chemosensitization and radiosensitization activities. Chloroquine was discovered in 1934 by a German scientist called Bayer.1 Although the mechanism continues to be not well understood, it has shown to inhibit the parasitic enzyme heme polymerase that converts the toxic heme into non-toxic hemozoin, thereby leading to the buildup of toxic heme within the parasite. These drugs may also interfere with the biosynthesis of parasitic nucleic acids. Hydroxychloroquine was first synthesized in 1945 by introducing a hydroxyl group into chloroquine. Animal studies showed that hydroxychloroquine is much less (around 40%) toxic than chloroquine.2 Hydroxychloroquine was approved for use in 1955 for the treatment of malaria and other several diseases including arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.3

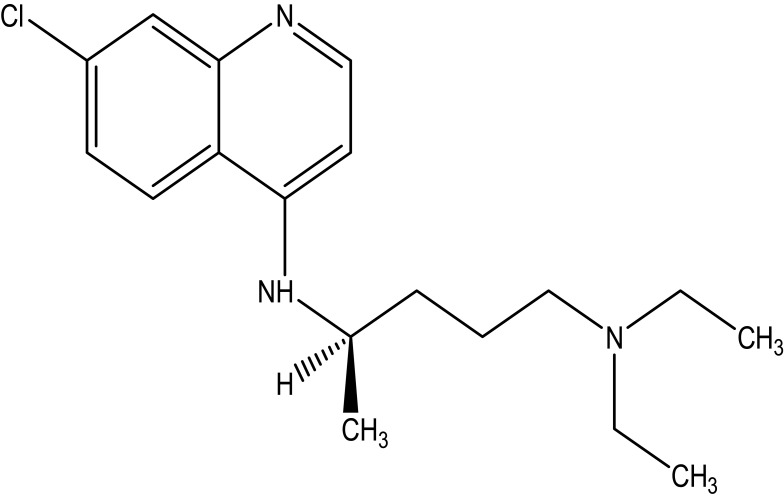

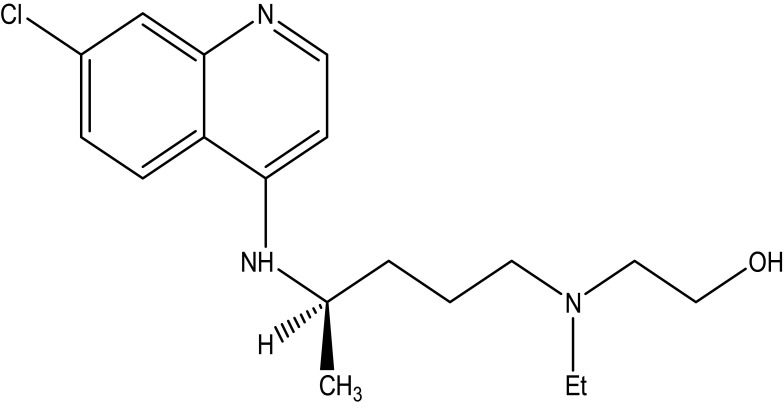

Chloroquine is a white or slightly yellow, odorless, and crystalline powder with a bitter taste substance. The melting point of this drug is between 87 to 92°C. It is very slightly soluble in water, but very soluble in chloroform, ether and dilutes acids. Chemically, it is 7-chloro-4-(4-diethylamino-1-methyl butyl amino) quinoline, or N4-(7-chloro-4-quinolinyl)-N1-N1-diethyl-1,4-pentanediamine as shown in Figure 1. The chemical structure of hydroxychloroquine is drawn by introducing a hydroxyl group into chloroquine as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of chloroquine.

Figure 2.

The chemical structure of hydroxychloroquine.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have serious adverse events. They potentially cause heart rhythm problems, and this could be exacerbated if the treatment is combined with other medicines, such as the antibiotic azithromycin, that have similar effects on the heart. Also, hypoglycemia, neuropsychiatric effects (such as agitation, confusion, hallucinations, and paranoia), interactions with other drugs, metabolic variability are some of the problems related to these drugs. The overdose of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are highly toxic and can cause seizures, coma, and cardiac arrest.4

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, alone or in combination with azithromycin, have been highly advertised as possible therapies for COVID-19.5 Chloroquine phosphate stood out among possible personalized pharmacological therapies for COVID‐19 due to the antiviral effect confirmed in preclinical studies and its high specificity towards the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor: angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE‐2). Large dissemination within lung tissue (the major organ affected in COVID‐19), and the consequences described in case series of severely ill COVID‐19 patients with promising clinical outcomes after being treated with chloroquine have recommended its possible use as an appropriate pharmacological option.6

Controversy About the Use of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 Treatment

The pandemic coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) has pushed the global healthcare system to a crisis and the world continues to search out safe and effective treatment options for COVID-19.7,8 Although there’s no conclusive evidence of their benefit, the globe continues the utilization of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, often together with a second-generation macrolide for the treatment on COVID-19.9 Since in vitro studies and a preliminary clinical report suggested the efficacy of chloroquine for COVID-19-associated pneumonia, there is increasing interest in this old antimalarial drug.10

Although generally safe when used for officially approved indications like autoimmune disorders or malaria, the risk and benefit of these drugs are poorly assessed in COVID-19. A multinational, observational world study on hospitalized patients with COVID-19 found that the employment of a regimen containing hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine (with or without a macrolide) was related to no evidence of benefit but instead was related to a rise in the risk of ventricular arrhythmias and death of patients in the hospital. This study recommended that these drug regimens should not be used unless urgent confirmatory findings from randomized clinical trials are obtained.11,12 Stronger evidence from well-designed robust randomized clinical trials is required before conclusively determining the role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19.13

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also struggles to play a critical role to seek out a solution for the COVID-19 pandemic. President Trump has directed the FDA to continue its effort to make sure the supply of probably safe and effective life-saving drugs to COVID-19 patients. The FDA has been working in collaboration with other government agencies and academic centers that are investigating the utilization of the drug chloroquine to see whether it is accustomed to treating patients with mild-to-severe COVID-19. FDA has investigated if the drug potentially reduces the duration of symptoms further as viral shedding, which might help prevent the spread of disease. FDA researches are continuing to work out the efficacy of using chloroquine to treat COVID-19.14

Although large-scale clinical and basic researches are still required to clarify its specific mechanism and to optimize the treatment plan, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization to use chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. According to the FDA, these drugs have shown good activity in laboratory studies and anecdotal reports suggest they may offer some benefit to hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Since there is no other better option currently, it is a hopeful practice to use these drugs to COVID-19. FDA also allowed hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products to be distributed and used for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. The FDA has warned that these drugs should only be used in hospitals or for clinical trials because they have been connected to a risk of heart rhythm problems, especially when paired with the antibiotic azithromycin.15,16 Most of the evidence to support the use of either of the drugs against the COVID-19 disease comes from a small trial in France.12,17 President Donald Trump has been also tweeting consistently that hydroxychloroquine and the antibiotic azithromycin could be one of the biggest game-changers in the history of medicine. The president has said he has been taking hydroxychloroquine to protect against the virus.18

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has warned against the widespread use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine to treat COVID-19. The EMA noted that there are no studies with strong evidence about the efficacy of these two medicines in treating COVID-19. The agency stressed that patients and healthcare professionals only use chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for their authorized use or as part of clinical trials or national emergency use programs for the treatment of COVID-19.17 According to the COVID-19 EMA pandemic task force, both drugs have been shown to cause heart rhythm problems due to electrical activity disruption. It could be highly fatal if the medication is taken at high doses or combined with other drugs, such as the antibiotic azithromycin, that have similar effects on the heart. The drugs have also toxic effects including liver and kidney problems, nerve cell damage that can lead to seizures, and hypoglycemia.19

The first randomized controlled clinical trial that tested chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in Brazil, Spain, and Mozambique also concluded that these drugs are not safe when used in high doses to treat patients with severe symptoms of COVID-19.20 This clinical trial was prematurely halted as the higher dosage of chloroquine diphosphate for 10 days was associated with more toxic effects and lethality. The study recommended that the higher chloroquine dosage should not be suggested for critically ill patients with COVID-19 because of its potential safety hazards, especially when taken concomitantly with azithromycin and oseltamivir.21

After all, the World Health Organization (WHO) temporarily stopped any clinical trials that use chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients after the shocking result of one study which is published in the most famous medical journal known as The Lancet. This study reported that these drugs have much more harm than good as patients getting hydroxychloroquine were dying at higher rates than other coronavirus infected patients.17 Finally, on May 22, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared that the clinical trials, as well as the clinical use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without macrolide, are halted internationally as they did not conclusively show in-hospital outcome benefits.16

Although WHO and other international organizations recommend to do not use these drugs, both hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine with or without macrolide are frequently used in several African countries for the treatment of COVID-19. Many African countries have already permitted at the government level to use these drugs to treat COVID-19 patients by opposing WHO warnings. Even the regional organization such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has officially approved for the use of chloroquine to treat coronavirus infected patients.22 This improper use of anti-malarial-drugs may highly complicate the COVID-19 case management in Africa. In addition to the toxic effects, shortages and increased market prices of these drugs lead African countries vulnerable to substandard and falsified medical products due to their poor healthcare system.23,24 The objective of the study was to review the off-label use practice of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment and prevention of COVID-19 in African countries against WHO recommendations.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

The countries in the continent of Africa were chosen for this review. For this study purpose, the countries were classified as East Africa, North Africa, West Africa, Central Africa, and South Africa.

Study Design

The study aimed to include all published studies without limitations, which focused on the off-label use practice of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 in African countries against WHO recommendation. The study also looked for commentaries, reviews, viewpoints, opinions, local and international news, and interviews. Clinical trials, medical case reports, and media reports that do not contain information about the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to treat or prevent COVID-19 were excluded. Studies that evaluated the prophylactic effects of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine were also excluded. Also, studies that are published in predator journals are excluded from the study.

Search Strategy

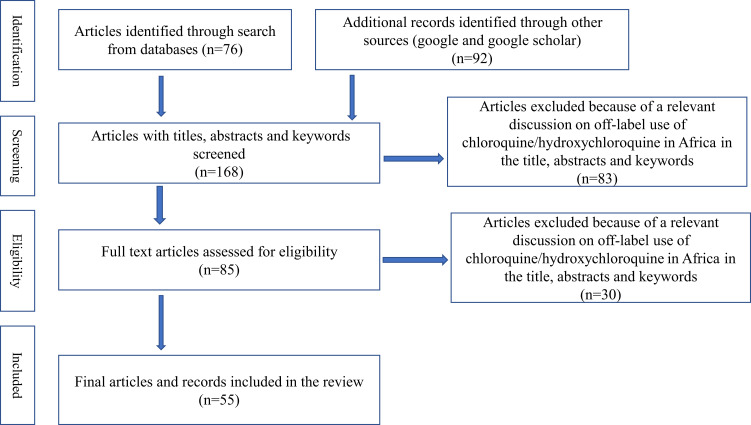

Data on the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment and prevention of COVID-19 disease in African countries were sourced from online electronic databases of published scientific literature. The clinical case reports and clinical trials of these drugs related to COVID-19 were searched from credible sources including Scopus, PubMed, Hindawi, OVID, Google Scholar, EMBASE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL], and Cochrane Methodology Register) from the beginning of COVID-19 until 15 June 2020. Some studies were also identified with a manual Google search. The utilization pattern of these drugs in African countries was also sourced from different local and international media. Primary search terms were “COVID-19”, “Chloroquine”, “Hydroxychloroquine” “Off-label”, “Africa” and “WHO recommendation”. These search terms were adapted for use with different bibliographic databases in combination with database-specific filters for studies, if available. The search strategy was used to obtain the titles and the abstracts of the relevant studies in English, and they were independently screened and subsequently retrieved abstracts, and if necessary, the full text of articles to determine the suitability. A flowchart of the literature search present in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of literature search.

Appraisal of the Selected Articles

The papers were critically appraised to identify and select following the checklist of PRESS 2015.25 No assumptions or simplifications were made during the process.

Off-Label Use Practice of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine in African Countries

Like that of other countries of the world, COVID-19 is becoming highly pandemic in most African countries. According to the latest data of John Hopkins University and Africa Center for Disease Control, there are more than 200,000 confirmed cases and 6000 deaths due to coronavirus in Africa until June 13, 2020. Despite the relatively lower number of COVID-19 cases in Africa, the pandemic remains a major threat to the continent’s poor health systems.26,27 As Africa News reported that five African countries (Egypt, Zambia, Nigeria, Tunisia, and South Africa) are doing different clinical trials by the support of Africa Centres for Disease Control (ACDC) as part of the continent’s step for treatment and prevention of the COVID-19. Egypt has 13 trials ongoing which specifically focus on COVID-19 therapeutics and around two trials on vaccines. Egyptian scientists are also doing nutritional support especially with honey and some immunotherapy trials. Zambia has one trial ongoing with hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug, which advertised as a potent remedy for coronavirus. South Africa is also looking at the efficacy of chloroquine, interferon, and remdesivir. Like in the case of Egypt, Nigeria has a trial in progress for different therapeutic agents. There are also two trials ongoing in Tunisia.28

Although there are several ongoing hopeful clinical trials for antiviral and immune-based therapies, there are no scientifically confirmed, clinically effective pharmacological treatments for COVID-19. The commonly used old antimalarial drugs, chloroquine, and hydroxychloroquine have become the attention of global scientific media and political focus regardless of a lack of randomized clinical trials supporting the drug’s efficacy and safety. The efficacy, as well as the safety of both of these drugs, is still not defined by clinical trials as well as WHO for the treatment and prevention of COVID-19.23 The irrelevant and controversial promotions even by higher public officials, mainly by Trump, lead to the widespread use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, mainly for African peoples. It leads to self-treatment, fatal overdoses, and extensive shortages of these drugs on the continent. For instance, Nigeria records several chloroquine poisonings cases after using it for COVID-19 treatment. As CNN reported from Lagos, Nigeria showed that three Nigerians in the country are critically ill in the hospital due to these drugs.29

The worldwide controversial reports that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine may be effective against COVID-19 have received great attention, increasing the risk of the introduction of falsified versions of these medicines mainly in African countries due to their poor health system. For instance, five different types of falsified chloroquine tablets were discovered between March 31, 2020, and April 4, 2020, in Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo by liquid chromatographic and mass spectrometric analysis. Such products represent a serious risk to patients. These events exemplify that once new medicines, regimens or vaccines against COVID-19 developed, its falsified product forms will enter the market immediately, especially in low- and middle-income countries.30

Off-Label Use of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine in East Africa

There are around 3305 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 96 Deaths in Kenya until June 13, 2020. South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) reported that Kenya approved the use of chloroquine to treat critical cases of patients with coronavirus. However, it is given only to critical patients as noted by Patrick Amoth, Kenyan Health Director-General. He, however, said that the sale of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine over the counter at pharmacies is not allowed. The country’s Pharmacy and Poisons Board has also banned over the counter sale of both hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in pharmacies. On the contrary to this, Kenyan medical experts warn to do not use these drugs since they require further clinical study and might not be the cure of COVID-19.22,31

Djibouti is one of the African countries which is extremely infected with COVID-19. There are around 4207 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people until June 13. However, as health officials of the country said that a death rate is just 0.5%. The top official of Djibouti’s main COVID-19 response center said that giving the anti-malarial drug, chloroquine, for COVID-19 patients is the main reason for the country’s low death rate. The government approved to treat all COVID-19 patients with chloroquine by ignoring WHO caution. Ahmed Zouiten, the WHO representative for the Djibouti country office, told via VOA that while the WHO has no scientific evidence to support the utilization of antimalarial drugs to treat COVID-19, observationally their use alongside antibiotics does seem to be working to Djibouti’s case. He believed that treating all COVID cases with antibiotics (azithromycin) and antimalarial drugs (chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine) has shown a positive impact. Dr. Maad Nasser Mohammed, a specialist in tropical infections who is chargeable for Djibouti’s main COVID-19 response center at the Arta Regional Hospital, also confirmed that the Djiboutian approach of treating all positive COVID cases with antibiotics and anti-malarial drugs provides a positive result.32

Another VOA report by interviewing one of Djibouti’s higher health officials showed that except for suffering from the loss of taste, cough, and fever, most of the patients did not experience any breathing problems after chloroquine treatment. He noted that chloroquine acts positively on COVID-19 treatment.33 The Global Times report also showed that both Ethiopia and Djibouti use an anti-malarial drug, chloroquine, and an antibiotic, azithromycin, to treat COVID-19 patients against WHO recommendations.34

Uganda recorded good results by treating COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine. The Uganda Ministry of Health told The Independent that they got good results by using hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in managing COVID-19 patients even though the drugs did not treat the disease. Uganda has used either of the two drugs in combination with azithromycin to manage COVID-19 patients at Entebbe General Hospital. Until June 13, 2020, 53 patients treated by these drugs are fully recovered. In addition to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, the patients have been given Vitamin C. Dr. Diana Atwine, secretary of the Ministry of Health, said that despite the recent findings, Uganda has scored good results from using these drugs. He also added that these drugs are not new for them and they know well about the side effects.35

Off-Label Use of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine in North Africa

Egypt is the leading African country with COVID cases as well as deaths. Like many African countries, Egypt uses chloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients. As Egypt Today report by mentioning the Egyptian Minister of Health, Hala Zayed, showed that Egypt is using anti-malarial and HIV drugs in the treatment of coronavirus (Covid-19) disease. As he said that they use these medications because they get positive results in treating more cases. Zayed cautioned that these drugs should not be used haphazardly by people, and physicians are those only who have the authority to prescribe them. He finally reminded citizens to not use these medications without consulting a doctor.36

On the contrary to Hala Zayed, the Health Ministry spokesman, Khaled Megahed, told to Egypt Today that the country denies producing chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients. He denied the news that a pharmaceutical company in the Egyptian capital, Cairo, started producing chloroquine phosphate medication primarily used to treat malaria patients. He said that the World Health Organization has not yet adopted any effective treatment for the novel coronavirus. Despite being seen as a good treatment for coronavirus by many people around the world, including US President Donald Trump, many clinical trials declared that both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are not yet confirmed to be effective for the treating of COVID-19 patients. According to the unproven announcement, the Arab Company for Drug Industry and Medical Appliances (ACDIMA) aims to produce around 200,000 doses of chloroquine by last May.37

According to the AFP report, Algeria is also one of the North African countries which use the anti-malarial drug (hydroxychloroquine) for COVID-19 treatment despite WHO dropping trials. One of the members of the scientific committee on the north African country’s Covid-19 outbreak, Mohamed Bekkat, said that they have treated thousands of cases with this hydroxychloroquine very successfully in Algeria. He also said that they have not noted any undesirable reactions. The Health Minister, Abderrahmane Benbouzid, also said that Algeria had great success in using hydroxychloroquine in combination with azithromycin. He also noted that there are no adverse reactions among several thousand patients who have taken these drugs. Several Algerian doctors have also claimed the treatment is very effective.24

Morocco also continues the use of chloroquine for COVID-19 treatment despite the controversy and warnings raised by the WHO. They were treating Covid-19 patients with chloroquine since April 8 and appear to have no intention of stopping. As the Minister of Health of Morocco, Khalid Ait Taleb has confirmed to AFP that though the WHO has decided to momentarily suspend clinical trials with hydroxychloroquine, Morocco maintains its use. He was explaining and defending the effectiveness of chloroquine by involving viral inactivation. According to his statement, the use of chloroquine provides good results and everyone can see it from the ground. The Minister told that 4841 COVID-19 patients out of the 7584 cases recorded in Morocco have recovered from the virus after following chloroquine treatment. According to Ait Tayeb, this treatment can reduce the viral load very quickly. Moroccan Health authorities also started safeguarding a satisfactory stock of chloroquine by purchasing from an international pharmaceutical company just two weeks after the declaration of the first COVID-19 case in the country. In addition to this, the Health Ministry initiated chloroquine therapy along with complementary medicine to enhance efficacy.38

Another North African country, Tunisia, was initially excited to and even started manufacturing its hydroxychloroquine. However, Tunisia declared that the treatment with hydroxychloroquine has been stopped in all the country’s hospitals following the statement from WHO.39

Off-Label Use of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine in West Africa

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has approved the use of chloroquine to treat coronavirus patients. ECOWAS supports the supplementary anti-viral treatment of coronavirus with hydroxychloroquine should be for mild forms of the virus. Meanwhile, Ghana’s health minister, Kweku Agyeman-Manu, said that he has approved for the anti-malarial drug to be used for treating COVID-19 patients. He told journalists in Accra that the chloroquine tests at Ridge Hospital are still positive and the tests are continued against WHO caution. The health minister also noted that the country has enough stock to treat all COVID-patients on admission.22

The Ghanaian Times also reported that the government of Ghana decided to use hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 case management. However, Ghana’s COVID-19 case management team is thinking about whether to continue or stop using for COVID-19 in the country after WHO halting the clinical trials of hydroxychloroquine as a possible treatment for coronavirus. The Director-General of the Ghana Health Service (GHS), Dr. Patrick Aboagye, said to Accra that the case management team of Ghana has decided to stop using hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19.40 The Ghana News Agency reported that Ghana denies chloroquine phosphate to cure coronavirus. The Director-General said that there is no strong evidence that chloroquine phosphate 250 mg is an effective treatment of COVID-19. They could therefore not make any recommendation for the use of the drug to treat the virus.41 The Ghana Medical Association (GMA) is also cautioning Ghanaians against the use and abuse of drugs such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and azithromycin in the treatment of Covid-19. According to GMA, these drugs can affect the function of the heart by causing abnormal heartbeat, making it deadly to patients with COVID-19.44

The report of the Anadolu Agency showed that Nigeria goes into clinical trials with hydroxychloroquine. The director of Nigeria’s National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) said that they believe in hydroxychloroquine and they will continue clinical trials of this drug on COVID-19 patients, despite the WHO warning. The director told that they are confused by the data of WHO reports to chloroquine whether it has from the Caucasian population or the African population. The director was also quoted by Nigerian local media as saying

If the information they’re gazing and also the reason for suspending the trials is from the Caucasian population, then it’s going to be justified. However, we do not think they got data from the African population yet because our genetic make-up is different.

She believed that if medical doctors, research scientists, pharmacists, and herbal experts work together, the clinical trials for this drug will be finished in 3–4 months. “The narrative might change later, but for now, we believe in hydroxychloroquine” she added.43 However, the NAFDAC has warned Nigerians against taking self-medication of chloroquine for treatment for coronavirus (COVID-19). Nobody should buy chloroquine and use it. Taking of chloroquine requires guidance and supervision to protect patients from damage and death related to its overdose.44

The Director-General of the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) warning to do not use chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment as well as for the prevention of coronavirus disease. The director noted that the use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for the management of COVID-19 disease has not been validated and approved by the WHO. Furthermore, Nigerians should know that self-medication and misuse of these drugs can cause harm and may lead to death. As the Lagos state officials told CNN, three people were hospitalized in the city after taking chloroquine. One witness also told CNN that in a pharmacy near his home in Lagos, the price of chloroquine rises by more than 400% in a matter of hours after Trump endorses it for coronavirus treatment. Finally, the Director-General of NCDC concluded that there have been promising results by researchers, but until now both drugs have not been licensed to treat COVID-19 related symptoms or prevent infection.29,45

African news reported that the Senegal government also continues treating COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine despite the ineffective and potentially harmful results of the recent study. They believed that the antimalarial drugs, chloroquine, and its derivative hydroxychloroquine, have been considered cheap and safe when used correctly for COVID-19 treatment. The head of Senegal’s Centre for Health Emergency Operations, Abdoulaye Bousso, told the AFP that the country’s hydroxychloroquine treatment program would nonetheless continue, without offering further details about the drug toxicities as well as warnings of WHO. Seydi, the Senegalese infectious-diseases doctor, also believed that hydroxychloroquine can be taken only after offered consent to patients and after performing a cardiogram by the medical staff.46

The senior health official of Senegal also told the Jakarta Post that Senegal is continuing to administer hydroxychloroquine to COVID-19 patients. The official said that the results of the treatments by this drug are still very encouraging. The televised statement of Moussa, the doctor in charge of treating Senegalese COVID-19 patients, said there is hopeful evidence that people treated with hydroxychloroquine recovered faster. He told AFP that about 50% of Senegal’s COVID-19 patients were being treated with hydroxychloroquine. However, he did not offer for the media any further details about the drug dosage, the exact number of patients under treatment, the age-range of the patients, or whether they had any underlying medical conditions. He said that patients under his care had exhibited “no side effects” and that he and his team are trying by combining hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin to achieve better results.47

Off-Label Use of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine in Central Africa

In Cameroon, chloroquine therapy for COVID-19 patients becomes the state protocol after the French expert, Professor Didier Raoult’s recommendation. A mixture of chloroquine (an antimalarial) combined with azithromycin (an antibiotic) to avoid the risks of secondary infections and to treat patients with Covid-19 has taken very seriously for Cameron. AFP and France 24 report showed the country’s scientific council and Cameroon’s Ministry of Health proposed the widespread use of chloroquine treatment. Although scientists lack conclusive data for their clinical trials, Cameron believes that the treatment is essential to reduce the viral load as well as the contagiousness nature of the disease. The council wished to combine the treatment, as recommended by Raoult, with azithromycin to avoid the risks of secondary infections. As the council said that the treatment protocol was validated for the management of all types of patients with positive Covid-19 tests, from asymptomatic cases to patients suffering from severe infections.48

Beyond a public health resolution, the choice of dual therapy represents a logistical challenge in Cameroon. Chloroquine was massively used in the country at one time and stocks were exhausted. Dr. Etoundi, director of the fight against diseases, epidemics, and pandemics of Cameroon’s Ministry of Health, explained that they had to place large orders from abroad and restart the wide national industrial production of chloroquine. Cameroon’s minister of scientific research and innovation, Madeleine Tchuente, said that the government has ordered the production of chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients and they are started producing 6000 tablets per day. As she said, the President, Paul Biya, has ordered them to produce at least eight million tablets of chloroquine each day as the situation is getting worse. The black market for drugs in normal times in Cameroon is rising with the Covid-19 crisis. Several fake chloroquine products are circulated within the Cameroon health network.49

Off-Label Use of Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine in South Africa

South Africa is one of the highly infected African countries by COVID-19 and they join a clinical trial on COVID-19 under WHO supervision. The South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) has warned health professionals to stop prescribing the medication chloroquine to prevent infection or to treat the disease, COVID-19 outside the hospitals. This warning comes after several pharmacies in South African cities have run out of chloroquine. The national health department of the country released a new guideline that allows using chloroquine only in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 and for consented clinical trials. This new guideline also noted that chloroquine should be distributed to all hospitals at affordable prices.50

The Katharine Child report to CNN also showed that chloroquine is made available and affordable for every corner of South Africa. However, science still does not know enough to back the antimalarial drug chloroquine into widespread use against the new coronavirus. A local pharmaceutical company in Johannesburg, South Africa, has received permission from the medical regulator of the country to import half a million chloroquine phosphate tablets for use in severely ill Covid-19 patients. The largest private pharmaceutical company in the country said that they donated more than 50,000 boxes of 10 tablets to the department of health for state use in a week.51

The health minister of Mozambique is also considering the possibility of using chloroquine to treat severe cases of coronavirus disease. The National Director of Public Health of Mozambique, Rosa Marlene, told the African press agency (APA) that the country allowed to use chloroquine for severely affected patients and the experiment of the consented clinical trial. She told that the worldwide trends of chloroquine use showed excellent results.52

Covid-19 complicates the tracing and treatment of malaria and compromise the wider public health programs in Zimbabwe. World Health Organization said that Zimbabwe reported that mosquito-borne diseases are significantly spiked in the country. WHO’s Global Malaria Programme said that in malaria-endemic countries, COVID-19 could make malaria more deadly. Zimbabwe’s ministry of health has already reported that there are three times more malaria cases than last year. As the ministry of health told that the occurrence of these elevated malarial cases is due to the similarity of symptoms, their main symptom, fever, between COVID-19 and malaria. This makes the country’s malarial management very complicated. The malaria cases are much higher than current Covid-19 cases in the country. Like other African countries, anti-malarial drugs, chloroquine, and hydroxychloroquine are being used to treat Covid-19 in Zimbabwe. However, Zimbabwe’s doctors advised their population to do not use chloroquine as there is insufficient data on their use for that purpose and high doses of the drugs can be life-threatening.53,54

Generally, many African countries use chloroquine in an off-label manner for the treatment as well as for the prevention of COVID-19 against WHO recommendation as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

African Countries Who Use Chloroquine or Hydroxychloroquine in an Off-Label Manner for the Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19 Against WHO Recommendation

| African Region | Countries That Use Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine for Treatment and Prevention of COVID-19 Against WHO Recommendation | References |

|---|---|---|

| East Africa | Djibouti, Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia | 22,31-35 |

| North Africa | Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria | 24,36-39 |

| West Africa | Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal | 22,29,40-47 |

| Central Africa | Cameroon | 48,49 |

| South Africa | South Africa, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe | 50–52,54 |

Conclusion and Recommendations

According to this review, many African countries use chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as both a preventive measure and for treating patients with COVID-19 regardless of WHO caution and toxicity findings of several clinical trials. Falsified and substandard chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine drugs are started to emerge in some African countries by considering the COVID-19 pandemic as a good opportunity. The health branches of the African government should assess the risks and benefits before providing these drugs to their people to treat COVID-19. African countries should strongly consider implementing prescription monitoring outlines to ensure that any off-label chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine use is appropriate and beneficial during this pandemic. The World Health Organization should intervene in this off-label use practices of antimalarial drugs in many African countries against their licensed purpose. If the existing global efforts worthful, much work is needed in Africa by the continental collaborated and coordinated production, distribution, and post-marketing surveillance aligned to the low-cost distribution of any approved COVID-19 drug to prevent use off-label and falsified drugs.

Healthcare professionals are recommended to closely monitor patients with COVID-19 receiving chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine and to consider patients with pre-existing heart problems that may make them more susceptible to heart rhythm issues. They should carefully consider the likelihood of cardiac arrhythmia, particularly with higher doses, and exercise extra caution when combining treatment with other medicines like azithromycin, which will cause similar side effects on the heart. African national drug regulatory organizations and other health authorities are advised to instantly notify WHO if falsified and substandard products are discovered in their country.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Author Contributions

The author conceived, designed, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The author has declared that they have no competing interests for this work.

References

- 1.Andersag H, Breitner S, Jung H. Quinoline compound, and process of making the same. US Patent. 1941;23(2):233–970. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattson K, Nolen RS; Iowa State University Student Government Senate, Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Statistical Atlas, Statistical Atlas, et al. Animal toxicity and pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine sulfate. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2020;256(12):1317–1320.32459591 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanenbaum L, Tuffanelli DL. Antimalarial agents: chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116(5):587–591. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1980.01640290097026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juurlink DN. Safety considerations with chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and azithromycin in the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection. CMAJ. 2020;192(17):450–453. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin EJ, Harrington DP, Hogan JW, Gatsonis C, Baden LR, Hamel MB The urgency of care during the Covid-19 pandemic—learning as we go. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Teherán AA, Camero G, Hernández C, et al. Potential negative effects of the free use of chloroquine to manage COVID‐19 in Colombia. J Med Virol. 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah S, Das S, Jain A, Misra DP, Negi VS. A systematic review of the prophylactic role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19). Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23(5):613–619. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1824–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCreary EK, Pogue JM. Coronavirus disease 2019 treatment: a review of early and emerging options. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(4):105. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smit C, Peeters MY, van den Anker JN, Knibbe CA. Chloroquine for SARS-CoV-2: implications of its unique pharmacokinetic and safety properties. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2020;18:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehra MR, Desai SS, Ruschitzka F, Patel AN. Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis. The Lancet. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Jaffe S. Regulators split on antimalarials for COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30817-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das S, Bhowmick S, Tiwari S, Sen S. An updated systematic review of the therapeutic role of hydroxychloroquine in Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19). Clin Drug Investig. 2020;28:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Continues to Facilitate Development of Treatments.2020.

- 15.American Medical Association. FDA warns against chloroquine for COVID-19 outside hospitals.2020. Available from https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/fda-warns-against-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospitals. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 16.Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO halts hydroxychloroquine trial to review links with increased mortality risk. BMJ. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The European Medicines Agency. COVID19: no Approval for Chloroquine from EMA. 2020. Available from: https://healthmanagement.org/c/hospital/news/covid-19-no-approval-for-chloroquine-from-ema. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 18.Eric S. Unlike FDA, European regulators refuse to clear chloroquine for COVID-19 without data. 2020. Available from https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/europe-locks-down-chloroquine-scripts-as-researchers-china-report-positive-controlled-covid. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 19.Hannah B. EMA warns about side effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 treatment.2020. Available from https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/117760/ema-warns-about-side-effects-of-chloroquine-and-hydroxychloroquine-for-covid-19-treatment/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 20.Ektorp E. Death threats after a trial on chloroquine for COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):661. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30383-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Africa CDC. COVID-19 Scientific and Public Health Policy Update. 2020. Available from https://africacdc.org/download/covid-19-scientific-and-public-health-policy-update-28-april–2020/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 22.Isaac K. Ghana, Kenya approve the use of Chloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients. Taylor and Francis group. 2020. Available from: https://africafeeds.com/2020/04/01/ghana-kenya-approve-use-of-chloroquine-to-treat-covid-19-patients/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 23.Abena PM, Decloedt EH, Bottieau E, et al. Hydroxychloroquine for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 in Africa: caution for inappropriate off-label use in healthcare settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1184–1188. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryad K. Algeria backs the use of the malaria drug despite WHO dropping trials. AFP. 2020. Available from https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/news/africa/Algeria-backs-hydroxychloroquine-use/4552902-5564930-duphp6/index.html. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 25.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdur R, Alfa S. Coronavirus in Africa: 216,775 cases; 5,852 deaths; 98,686 recoveries. africanews. 2020. Available from https://www.africanews.com/2020/06/11/coronavirus-in-africa-breakdown-of-infected-virus-free-countries/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 27.WHO Africa. Africa COVID-19 cases top 100 000.2020. Available from https://www.afro.who.int/news/africa-covid-19-cases-top–100–000. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 28.Abdur R, Alfa S. Five African countries with ongoing coronavirus trials. Africanews. 2020. Available from https://www.africanews.com/2020/05/01/fiveafricancountries-with-ongoing-coronavirus-trials//. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 29.Stephanie B, Bukola A. Nigeria records chloroquine poisoning after Trump endorses it for coronavirus treatment. CNN. 2020. Available from https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/23/Africa/chloroquine-trump-Nigeria-intl/index.html. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 30.Gnegel G, Hauk C, Neci R, et al. Identification of falsified chloroquine tablets in Africa at the Time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(1):73–76. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chinyanja N, Zochitika M Kenya to use chloroquine on critical cases of coronavirus. BBC. 2020. Available from http://www.channelafrica.co.za/sabc/home/channelafrica/news/details?id=fa515c2f-d19a-4779-8675 ff9af2771001&title=Kenya%20to%20use%20chloroquine%20on%20critical%20cases%20of%20coronavirus.. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 32.Simon M Djibouti is treating all COVID patients with chloroquine, but scientists urge caution. VOA. 2020. Available from https://www.voanews.com/covid-19-pandemic/djibouti-treating-all-covid-patients-chloroquine-scientists-urge-caution. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 33.Nii N Djibouti, others warned about chloroquine despite big COVID-19 recoveries. VOA. 2020. Available from https://face2faceafrica.com/article/djibouti-others-warned-about-chloroquine-despite-big-covid-19-recoveries. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 34.Li Q Chinese medical expert decorated by Djibouti for COVID-19 prevention. Global Times. 2020. Available from: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1189839.shtml. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 35.Museveni P Uganda records good results in treating COVID with hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine. The Independent. 2020. Available from https://www.independent.co.ug/uganda-records-good-results-treating-COVID-with-hydroxychloroquine-chloroquine/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 36.Mohhamad D Egypt uses chloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients: minister. Egypt Today. 2020. Available from https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/83104/Egypt-uses-chloroquine-in-treating-COVID-19-patients-Minister. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 37.Alex B. Egypt uses chloroquine in treating COVID-19 patients: minister. Egypt Today. 2020. Available from https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/84462/Health-Ministry-denies-producing-chloroquine-to-treat-COVID-19-patients. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 38.Mussa K. Morocco continues the use of Chloroquine despite controversy. The North Africa Post. 2020. Available from https://northafricapost.com/41247-morocco-continues-use-of-chloroquine-despite-controversy.html. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 39.Brian W. Covid-19: algeria and Morocco continue using chloroquine despite concerns. al-bab.com. 2020. Available from https://al-bab.com/blog/2020/05/covid-19-algeria-and-morocco-continue-using-chloroquine-despite-concerns. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 40.Jonathan D. Ghana: govt to decide on hydroxy chloroquine for COVID-19 case management. all African news. 2020. Available from https://allafrica.com/stories/202005270578.html. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 41.Alfonson L. Ghana denies Chloroquine Phosphate can cure coronavirus. African Press Agency. 2020. Available from http://apanews.net/en/news/ghana-denies-chloroquine-phosphate-can-cure-coronavirus. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 42.Felicia O. Ghana Medical Association cautions against the use of Chloroquine, others in the treatment of Covid-19. Health. 2020. Available from https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/health/ghana-medical-association-cautions-against-use-of-chloroquine-others-in-the-treatment-of-COVID–19/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 43.Felix T. Nigeria goes on with hydroxychloroquine clinical trials. Anadolu Agency. 2020. Available from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/nigeria-goes-on-withhydroxychloroquine-clinical-trials/1854814. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 44.Kano K. Nigeria: COVID-19 - again, NAFDAC warns against use of chloroquine. AllAfrica news. 2020. Available from https://allafrica.com/stories/202005150035.html. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 45.Chike O. NCDC warns Nigerians against the use of chloroquine for COVID-19. Nairametrics. 2020. Available from https://nairametrics.com/2020/03/26/ncdc-warns-nigerians-against-use-of-chloroquine-for-covid–19. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 46.Dangon T. Senegal to continue treating COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine. Africanews. 2020. Available from https://www.africanews.com/2020/05/28/senegal-to-continue-treating-COVID-19-patients-with-hydroxychloroquine//. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 47.Zohra B. Senegal says hydroxychloroquine virus treatment is promising. AFP. 2020. Available from https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2020/04/02/senegal-sayshydroxychloroquine-virus-treatment-is-promising-.html. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 48.David R. Covid-19: in Cameroon, chloroquine therapy hailed by French experts becomes state protocol. AFP. 2020. Available from https://www.france24.com/en/20200503-covid-19-in-cameroon-a-chloroquine-therapy-hailed-by-french-expert-becomes-state-protocol. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 49.Moki EK. Cameroon begins large-scale chloroquine production. VOA. 2020. Available from https://www.voanews.com/science-health/coronavirus-outbreak/cameroon-begins-large-scale-chloroquine-production. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 50.Aisha AK. Doctors warned against prescribing unproven medication for COVID-19. Bhekisisa.org. 2020. Available from https://bhekisisa.org/health-news-south-africa/2020-04-01-doctors-warned-against-prescribing-unproven-medication-for-covid–19/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 51.Katharine C. EXCLUSIVE: SA to roll out chloroquine to tackle coronavirus. South African Broadcasting Corporation. 2020. Available from https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/features/2020-03-27-sa-to-roll-out-chloroquine-to-tackle-coronavirus/. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 52.Wakando G. Mozambique: considering chloroquine to tackle COVID-19. APA. Available from http://apanews.net/en/news/covid-19-mozambique-to-experiment-chloroquine-against-severe-cases. Accessed August19, 2020.

- 53.Ahmed AE. Incidence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and countries affected by malarial infections. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101693. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryan T. Covid-19 could complicate tracing and treatment of malaria and compromise wider public health programs, new guidance from the World Health Organisation says, as Zimbabwe reported its significant spike in the mosquito-borne disease. APA. 2020. Available from http://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20200411-covid-19-will-make-malaria-tracing-and-treatment-much-harder-who. Accessed August19, 2020.