Abstract

Many animal species remain separate not because their individuals fail to produce viable hybrids but because they “choose” not to mate. However, we still know very little of the genetic mechanisms underlying changes in these mate preference behaviours. Heliconius butterflies display bright warning patterns, which they also use to recognize conspecifics. Here, we couple QTL for divergence in visual preference behaviours with population genomic and gene expression analyses of neural tissue (central brain, optic lobes and ommatidia) across development in two sympatric Heliconius species. Within a region containing 200 genes, we identify five genes that are strongly associated with divergent visual preferences. Three of these have previously been implicated in key components of neural signalling (specifically an ionotropic glutamate receptor and two regucalcins), and overall our candidates suggest shifts in behaviour involve changes in visual integration or processing. This would allow preference evolution without altering perception of the wider environment.

Subject terms: Behavioural ecology, Evolutionary genetics, Speciation, Behavioural genetics

The genetic mechanisms underlying mate choice decisions can inform our understanding of speciation. A study on Heliconius butterflies identifies 5 candidate genes that would allow sympatric species to evolve distinct preferences without altering their visual perception of the wider environment.

Introduction

The evolution and maintenance of new animal species often relies on the emergence of divergent mating preferences1,2. Changes in sensory perception or other neural systems must underlie differences in innate behaviours between species, and will ultimately have a genetic basis. Although the significance of behavioural barriers for speciation has been recognized since the Modern Synthesis3, we know little of the genes underlying changes in mating preferences, or variation in behaviours across natural populations more broadly4. Identifying these genes will provide an important route towards understanding how behavioural differences are generated, both during development and across evolutionary time.

Previous studies of isolating preference behaviours have largely been limited to the identification of causal genomic regions, which almost invariably contain many genes5–7. Only a handful of studies have identified likely candidate genes that contribute to species behavioural preferences. These are largely limited to chemosensory-guided mating preferences8–10, but see11, and have identified changes at chemoreceptor genes. To our knowledge, only two studies—in incipient fish species—have identified candidates for visual preference evolution, albeit indirectly, both suggesting a role for sensory perception mediated by changes in the peripheral visual system (e.g., opsins)12,13. Whether or not visual preference evolution generally involves shifts at the sensory periphery, or in downstream processing, remains unknown.

The closely related species Heliconius melpomene and Heliconius cydno differ in warning patterns, which are both under disruptive selection due to mimicry14 and are important mating cues15. As a result, these divergent patterns couple ecological and behavioural components of reproductive isolation, which (as predicted by so-called “magic trait” models16) is expected to facilitate speciation in the face of gene flow. In central Panama, H. melpomene shares the black, red and yellow pattern of its local Heliconius erato co-mimic, whereas H. cydno shares the black and white patterns of Heliconius sapho. H. melpomene and H. cydno remain separate largely due to strong assortative mating17. Visual preferences for divergent patterns are particularly apparent in males, which strongly prefer to court conspecific females15,18,19. Differences in warning pattern between H. melpomene and H. cydno are largely due to expression differences in just three genes, specifically optix20, WntA21 and cortex22.

Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping of H. melpomene and H. cydno has revealed three genomic regions of major effect that influence the relative time males spend courting red H. melpomene or white H. cydno females19. Notably, the best supported QTL was in the same genomic region as optix, the gene responsible for presence and absence of red colour pattern elements in Heliconius20. Genetic linkage is expected to facilitate speciation by impeding the breakdown of genetic associations between ecological and mating traits22,23. Nevertheless, this QTL, and its associated candidate region, contain hundreds of genes, and the exact genes responsible for differences in preference behaviour are not known.

Here, we first confirm that the behavioural QTLs identified previously are associated with variation in male courtship initiation. We then identify genes within the major QTL, which were differentially expressed in the neural tissue (central brain, optic lobes and ommatidia) of H. melpomene and H. cydno, or have protein-coding changes predicted to alter protein function. Out of 200 genes within the QTL region, we identify just five candidates likely to underlie assortative mating behaviours.

Results

Chromosome 18 is associated with courtship initiation

Our previous results reveal that QTLs on chromosomes 1, 17 and 18 influence the relative time hybrid males spend courting red H. melpomene or white H. cydno females19. However, the time males spend courting a particular female might depend not only on male attraction, but on the female’s response (and in turn his response to her behaviour). To confirm that these previously reported QTLs influence male approach behaviours (as opposed to other traits that may influence courtship, for example male morphology24), we reanalyzed our previous data, explicitly considering whether males initiated courtship towards H. melpomene, H. cydno or both types of female during choice trials.

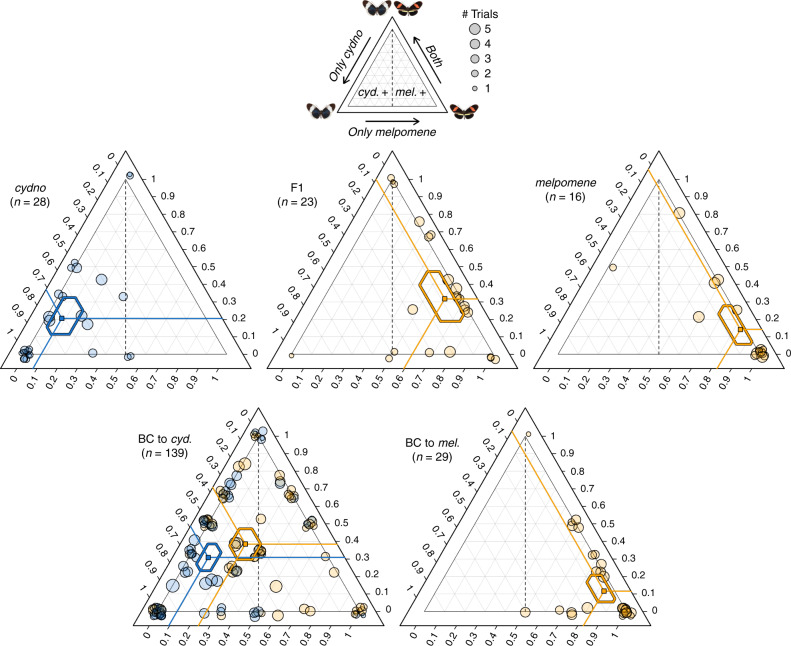

Consistent with our previous analyses19, we found that males of both species, and in particular H. melpomene males, show a strong preference for females of their own phenotype. F1 and backcross-to-melpomene prefer to court melpomene females, whereas courtship initiation behaviours segregate in the backcrosses to cydno (Fig. 1). The QTL on chromosome 1 was retained in our model of initiation behaviours (Supplementary Fig. 1; n = 139, ΔELPD = −13.6 (SE ± 5.7), i.e., a change of 2.34 SE units). In contrast, the QTL on chromosome 17 was not retained (n = 139, ΔELPD = −2.1 (SE ± 3.0)). Notably, backcrosses-to-cydno males heterozygous (i.e., with a H. melpomene allele derived from the F1 father) at the best supported QTL from our previous analysis19 (on chromosome 18) initiated courtship towards H. melpomene females more frequently than males homozygous for the H. cydno allele (Fig. 1, bottom left; n = 139, ΔELPD: −10.9 (S.E. ± 5.1), i.e., a change of 2.14 SE units). As in our previous analyses of relative courtship time19, we found little evidence for an interaction between the QTLs on chromosome 1 and 18 (including the interaction led to a worse fit compared to a model excluding the interaction: ΔELPD: −1.7 (SE ± 0.9), i.e., a change of 1.89 SE units), suggesting additive effects. Together with previous evidence that male hybrids bearing H. melpomene alleles at optix prefer to court the artificial models of H. melpomene females over those of H. cydno25, these results suggest that the QTL on chromosome 18 harbours genes for visual attraction behaviours towards females with the red pattern (and that the H. melpomene alleles are dominant). As a result, we focused our subsequent analyses on this QTL on chromosome 18 (and also because tight linkage of optix allowed us to track the alleles at the preference locus in hybrid crosses). A recent study26 also reports no candidate chemosensory genes for reproductive isolation at this QTL region on chromosome 18 (or at any other QTL).

Fig. 1. Genotype at the QTL on chromosome 18 influences courtship initiation.

Ternary plots showing the proportion of 15-min choice trials in which single male individuals initiated courtship towards H. melpomene, H. cydno or both females. Left ternary axis shows the proportion of trials where courtship was initiated towards H. cydno female only, bottom axis towards H. melpomene female only, and right axis towards both female species. Trials without male response were removed from the dataset. Each point represents a single individual and the location of the point in the triangle is a way of representing these three proportions at once. Lines project the three predicted proportions to corresponding values on the three axes and 95% credibility intervals (CrIs) for these proportions are shown as hexagons. Orange points represent individuals that have inherited at least one H. melpomene derived allele at the preference QTL on chromosome 18 (i.e., either melp/melp or cyd/melp); and blue points represent individuals that are homozygous for H. cydno alleles at the preference QTL on chromosome 18 (i.e. cyd/cyd). Point size is scaled to the number of trials in which the male showed a response and a ‘jitter’ function has been applied (leading to some dots being jittered to outside the triangle).

27 genes within the major QTL are differentially expressed

We hypothesized that changes in gene regulation that determine differences in visual mate preference behaviours might occur during pupal development (for instance, during visual circuit assembly) or at the adult stage, and must involve changes in the peripheral and/or central nervous system27. Therefore, we generated RNA-seq libraries for combined eye and brain tissue, across two pupal stages (around the time of ommochrome pigment deposit and halfway through pupal development) and one adult stage, for H. melpomene and H. cydno and compared their gene-expression levels. Across the QTL region on chromosome 18 (which spans 2.75 Mb and contains 200 genes), we identified 27 genes that show differential expression between H. melpomene and H. cydno, in at least one of the three developmental stages. These were mostly located within the QTL peak (i.e., the genomic region with strongest statistical association with male preference) or in close proximity to optix (Fig. 2). The same genes were frequently differentially expressed across development (Supplementary Table 1), with 11 genes being differentially expressed in more than one stage.

Fig. 2. Differential expression at the preference QTL region on chromosome 18.

Left: Summary of the comparative transcriptomic analyses with stage, number of samples and chromosome 18 composition. Right: the corresponding results, zooming in on the QTL region on chromosome 18. The x-axis represents physical position. The QTL peak, and the rest of the QTL 1.5 LOD candidate region (from ref. 19) are shown in green and purple, respectively. Points correspond to individual genes, with the y-axis indicating the log2(fold change) for each comparison. The two horizontal dashed lines (at y-values of 1 and -1) indicate a twofold change in expression. Genes showing a significant twofold+ change in expression level between groups are highlighted in orange and blue, where orange indicates higher levels in H. melpomene or in the hybrids cyd/melp (blue if in H. cydno—hybrids cyd/cyd). Vertical dashed lines highlight those genes that are differentially expressed between H. melpomene and H. cydno AND between cyd/melp vs cyd/cyd individuals, at the same stage (Grik2 and regucalcin2 at the adult stage, Grik2 at 60 h APF). Two genes highlighted by dashed fuchsia vertical lines were excluded because they did not show differential expression, or showed reversal of the fold change when mapping RNA-seq reads to the H. cydno genome. Note that Heliconius brain (reconstruction) images, added for reference, do not include the eyes (ommatidia and retinal membrane).

The genomic region between the start of chromosome 18 and optix (comprising the QTL peak) is highly divergent between H. melpomene and H. cydno28, and divergent gene sequences within this region could also introduce mapping biases of RNA-seq reads. To account for this, we repeated the analysis having mapped to both the H. melpomene reference genome29 and to a H. cydno genome30. Generally, we found similar patterns of differential expression when mapping to the H. cydno genome (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2A). Nevertheless, in subsequent analyses we excluded two genes, HMEL034187g1 and HMEL034229g1, which showed reversal of the fold change or did not show differential expression when mapping to the H. cydno genome, respectively.

Although our focus was primarily on chromosome 18, two genes within the QTL region on chromosome 1 were also differentially expressed for at least one developmental stage (Supplementary Table 1), when mapping to the H. melpomene and H. cydno genomes. Of these, one (HMEL003796g1), associated with the regulation of enolase, was also upregulated in F1 hybrids (see below).

Regucalcin2 and Grik2 are upregulated in hybrid males

Our previous behavioural experiments suggest that the alleles for the H. melpomene behaviour are dominant over the H. cydno alleles19,25 (Fig. 1). Given this pattern of dominance, we predicted that genes underlying variation in male preference to be up- or downregulated in the brains of both H. melpomene and first generation (F1) hybrid males, with respect to H. cydno. Of the putative genes differentially expressed between H. cydno and H. melpomene reported above, only four, within the QTL candidate region, were differentially expressed between the F1 hybrids and H. cydno (Fig. 2). These included two regucalcins (also called senescence marker proteins-30: HMEL013552g1, HMEL034199g1), an ionotropic glutamate receptor (HMEL009992g4), which is a putative ortholog of Grik2, and one gene with no annotated function (HMEL009992g1). We obtained the same results regardless of whether we considered both males and females together, or males alone. Further inspection of spliced mRNA-reads indicated that the two annotated regucalcins were in fact a single gene (from now on referred to as regucalcin2). This was also the case for the ionotropic glutamate receptor and the gene with no annotated function (from now on referred to as Grik2).

To ensure that the apparent fragmentation of a few gene models in the H. melpomene (Hmel2.5) annotation31 did not introduce inaccuracies in estimates of differential gene expression, we produced a new transcript-based annotation of the melpomene genome using Cufflinks’s RABT32. Repeating all comparative transcriptomic analyses using this new annotation (where exons previously considered to be distinct genes are now assigned correctly to single genes), we confirmed that both regucalcin2 and Grik2 were differentially expressed in both species and hybrids comparisons. Finally, to determine whether differential expression of these genes was repeatable across sequencing experiments, we generated RNA-seq libraries for additional H. melpomene, H. cydno and F1 hybrids adult brains, sampled 5 years after our initial tissue collection and sequenced independently. Differential expression of Grik2 and regucalcin2 is consistently detected both between H. melpomene and H. cydno and between F1 hybrids and H. cydno, both when these datasets are analysed separately, and when combined.

Regucalcin2 and Grik2 show cis-regulatory effects

Causal changes in gene regulation underlying phenotypic variation associated with the QTL must result from cis- rather than trans-regulation. In other words, if changes in expression of Grik2 and regucalcin2 account for the observed shifts in behaviour associated with the QTL these must be due to changes within the cis-regulatory regions of the genes themselves (as opposed to of other trans-acting genes elsewhere in the genome); and these causal mutations should be within the QTL region on chromosome 18. To determine whether differences in gene-expression levels between parental species were due to cis- or trans-regulatory changes, we conducted allele-specific expression (ASE) analyses in adult F1 hybrids (from both sequencing batches). In F1 hybrids, both parental alleles are exposed to the same trans-environment, and consequently trans-acting factors will act on alleles derived from each species equally (unless there is a change in the cis-regulatory regions of the respective alleles). Therefore, differences in ASE indicate changes in cis-regulatory regions33. For both candidate genes (Grik2 and regucalcin2) the H. melpomene allele was significantly more highly expressed relative to the H. cydno allele (p < 0.001, Wald test), suggesting cis-regulatory effects (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Grik2 and regucalcin2 show evidence of allele-specific expression.

Points indicate the mean value, and bars the standard error, of the (base 2) logarithmic fold change in expression between parental species (vertical) (n = 23 biologically independent samples) and the alleles in F1 hybrids (horizontal) (n = 10 biologically independent samples), for candidate genes (as defined in the transcript-guided annotation). Dashed lines indicate the threshold for a twofold change in expression for the genes in the species (horizontal), and for the alleles in the hybrids (vertical). Both genes seem to be regulated by a combination of cis- and trans-acting factors, rather than cis-acting factors alone (which would be indicated by y = x).

Gene-expression differences in backcross hybrids

In order to study the specific effects that H. melpomene derived alleles at the QTL on chromosome 18 had on gene-expression, we introgressed this region into a H. cydno background through multiple backcrosses (crossing design in Supplementary Fig. 3). We wanted to investigate whether differences at this QTL regulated expression of any specific genetic pathway during development, and more generally what changes in genome-wide transcription were observed in hybrids differing (mostly) just at this QTL region. We compared six cyd/melp vs. ten cyd/cyd (at the QTL region on chromosome 18) BC3 hybrids sampled at 156 h after pupal formation (APF) (Supplementary Fig. 5A), and eight cyd/melp vs. nine cyd/cyd for those at 60 h APF.

Across the entire genome, only 23 genes at 156 h APF and 29 genes at 60 h APF were differentially expressed between third-generation backcross hybrids with cyd/cyd and cyd/melp genotypes at the QTL. Within the QTL candidate region, Grik2 was the only gene detected as differentially expressed between species and hybrids at these pupal stages (at 60 h APF, Supplementary Fig. 4). Of the remaining ten genes that were differentially expressed between both species and backcross hybrids at either stage, seven were located within the introgressed region (0–6.3 Mb, Supplementary Table S3), and it seems likely that these are regulated by introgressed H. melpomene cis-acting elements. We discuss the possibility of a cis-regulatory element within the QTL candidate region acting on a gene outside the QTL in the Supplementary information.

It is possible that causative loci (e.g. expressed RNA or protein factors) within the QTL could act on other genes in trans (both on chromosome 18 and elsewhere in the genome), and identifying these could provide insight into the mode of action of causative genetic elements. Three genes differentially expressed both in species and backcross hybrid comparisons, and located outside of introgressed regions, including HMEL014795g1 and HMEL015842g1 (at 10.2 Mb and 13.5 Mb on chromosome 18, respectively) and HMEL030024g1 (on chromosome 1) might be considered good candidates for trans-regulation. However, in our backcrosses, the region on chromosome 18 introgressed from H. melpomene into a H. cydno background extends ~3.6 Mb beyond the QTL candidate region, making it difficult to determine whether these genes are regulated by loci associated with variation in behaviour. Furthermore, no genetic pathway was enriched for gene-expression differences between these hybrids at either pupal stage (PANTHER enrichment test34), suggesting that overall this QTL harbours a few, modular changes in gene regulation in the developing brain/eyes of H. cydno and H. melpomene, or at least not impacting on other genes in trans with a clear mode of action.

To verify that differential expression of candidate genes within the QTL region is driven by H. melpomene alleles on chromosome 18 and not by other H. melpomene alleles at trans-acting genes on other chromosomes, we compared gene-expression levels between hybrids carrying cyd/melp vs. cyd/cyd regions on chromosomes chr1, chr4 and chr15, chr20 (Supplementary Fig. 5A). In these comparisons, there was no signal of differential expression on chromosome 18. This supports the cis-regulatory activity of the melpomene allele of candidate genes on chromosome 18. To test this further, we conducted another ASE study in the BC3 hybrids, which suggested trans-only regulatory effects for Grik2 at these pupal stages, and cis-regulatory effects for regucalcin2 at 60 h APF (p < 0.038, Wald test) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Since causal gene/s might exert an effect on behaviour due to their action during development or in adult form, and this action might in turn be differently (cis- vs trans-) regulated, we still considered both genes as strong candidates.

Four candidate genes have protein-coding substitutions

Because shifts in behavioural phenotypes could be due to changes in protein-coding regions, we additionally considered protein-coding substitutions between H. melpomene and H. cydno. Overall, we found 152 protein-coding substitutions, spanning 54 of the 200 genes across the entire QTL candidate region. We then studied whether these variants were predicted to have non-neutral effects on protein function with PROVEAN35. The PROVEAN algorithm predicts the functional effect of protein sequence variations based on how they affect alignments to different homologous protein sequences. We found four genes with such predicted effects (PROVEAN score < −2.5): Specifically, a WD40-repeat domain containing protein (HMEL013551g3), a cysteine protease (HMEL009684g2), a MORN motif containing protein (HMEL006660g1), and another regucalcin (HMEL013551g4) adjacent to, but distinct from, that found to be differentially expressed above (from now on referred to as regucalcin1).

Candidate genes occur in regions with reduced gene flow

Of our six candidate genes for preference behaviours that contribute to reproductive isolation between H. cydno and H. melpomene (regucalcin2, Grik2 and the four genes with protein-coding modifications), five are found within the QTL peak (Fig. 4). Genetic changes causing reproductive isolation between populations are expected to reduce localized gene flow in their genomes. Therefore, we compared the position of our candidate genes to estimated levels of admixture proportions (fd)36 between H. melpomene and H. cydno across the QTL candidate region37. We found that candidate genes were located in genomic regions with low fd values (Fig. 4), suggesting localized resistance to gene flow between H. melpomene and H. cydno at these genes and their putative cis-regulatory regions.

Fig. 4. Gene flow at the QTL region for behaviour.

Admixture proportion (fd) values estimated in overlapping 100 kb (top) and 20 kb (bottom) windows for chromosome 18 (top) and the QTL region (bottom) between H. melpomene rosina and H. cydno chioneus, with candidate genes positions highlighted by a vertical dashed line, and optix location displayed for reference. The x-axis represents physical position, the y-axis indicates the fd value. fd values close to zero indicate that the proportion of shared derived alleles, and consequently gene flow, between H. melpomene and H. cydno is small (or zero), implying localized selection against foreign alleles that introgress between the two species. 5 and 25% quantile of the fd distribution are indicated by horizontal grey dotted lines.

Discussion

Behavioural isolation is frequently implicated in the formation of new species1,38, and often involves the correlated evolution of both mating cues and mating preferences. Here we have analysed a genomic region in a pair of closely related sympatric butterflies, H. cydno and H. melpomene, that contains genes for divergence in both an ecologically relevant mating cue and the corresponding preference. Physical linkage between ecological and mating traits is expected to facilitate speciation by allowing different barriers to act in concert to restrict gene flow39,40. Although the genes underlying changes in the warning pattern cue in Heliconius are well characterized20–22,41 (e.g., optix), those underlying the corresponding shift in behaviour have not previously been identified19,42,43. We have pinpointed a small number of genes that fall within the peak of the best supported QTL (on chromosome 18), which show either expression (regucalcin2 and Grik2) or protein-coding differences (HMEL013551g3, HMEL009684g2, and regucalcin1) and fall within a region of reduced admixture, that are strong candidates for modulating mating behaviour.

Two broad neural mechanisms could underlie the evolution of divergent visual preferences, involving changes in either (1) detection at the sensory periphery or (2) the processing and/or integration of visual information. Although H. melpomene and H. cydno have the same retinal mosaics/class of photoreceptors44, spectral sensitivity in the Heliconius eyes could be altered by filtering pigments45, or other physiological processes taking place at the photoreceptors/sensory periphery, eventually shifting sensitivity towards different wavelengths (and possibly colour patterns). It has previously been hypothesized that the gene regulatory networks for ommochrome deposition in the Heliconius eyes might have been co-opted in the wings46, where optix plays a central role, and therefore that optix might play a role in eye pigmentation in Heliconius. However, the protein product of optix has not been detected in pupal or adult retinas of various Heliconius species tested47, and therefore has no obvious link to ommochrome deposition in the eyes. More generally, the underlying evolutionary mechanism is unlikely to involve detection at photoreceptors, as this would probably have a broad effect on downstream processing2 and alter the visual perception of the animal’s wider environment.

The second mechanism, involving changes in the processing, and/or integration, of visual information, could act through an alteration of neuronal activity or connectivity. For instance, different levels of gene expression in conserved neural circuits between H. melpomene and H. cydno may affect overall synaptic weighting and determine whether a signal (e.g., colour and motion) elicits a motor pattern (response towards a female) or not. Consistent with this scenario, the composition of ionotropic receptors at post-synapses is a key modulator of synaptic transmission48, implicating Grik2. Differential expression of ionotropic receptors is also associated with variation in female preference behaviours in fish49–51, raising the possibility that ion channels might provide a likely route to modulate mate preferences across taxa more broadly. Regucalcins are involved in calcium signalling52, which regulates synaptic excitability and plasticity53, and has an important role in axon guidance54 (albeit alongside additional roles across a broad range of biological processes), making the two regucalcins we identify strong candidates for behaviour.

Changes in the regulation of genes with pleiotropic effects are likely to be less detrimental compared to changes in their protein-coding sequences55 (although emerging evidence has begun to suggest that enhancer/repressor elements may be more pleiotropic than previously thought56,57). Furthermore, there is considerable evolutionary potential in the co-option of transcription factors/networks55 that regulate neural patterning or neuron-type activity, possibly resulting in novel adaptive expression patterns. In line with this, regucalcin2 and Grik2, which are differentially expressed in the eyes and brain in both our species and hybrid comparisons, are likely to be involved in multi-functional processes, such as calcium signalling and ion transport, and likely have pleiotropic alleles. We also found evidence of cis-regulatory effects for both genes, which would be required of the causal genetic change within the QTL, if it were to affect gene regulation.

Neither regucalcin2 nor Grik2 shows male-biased gene expression, which might be expected of candidate genes for a behaviour that is evident only in males. It is possible that the lack of sex-biased expression indicates that visual cues are similarly important in female mating preference in this species pair. Indeed, Chouteau et al.58 report that female preferences contribute to disassortative mating between colour pattern morphs of Heliconius numata, and it is possible that in H. cydno and H. melpomene females share the same genetic basis for colour pattern-based discrimination as males. Alternatively, if visual preference behaviour is restricted to males, changes in gene expression may be integrated differently in the female and male nervous systems. The role of female preference in Heliconius mate choice remains poorly understood. Although emerging data suggests that female choice does contribute to reproductive isolation between melpomene-cydno clade taxa59,60, it remains to be tested if there is a strong visual component to this preference similar to that observed in males.

Despite expectations that non-coding, regulatory loci may provide a flexible route to divergent mating preferences, we also found substitutions in coding regions at the QTL, which are predicted to have an effect on protein functioning and therefore remain strong candidates. These genes include regucalcin1, which is distinct from, but located next to, regucalcin2 (which is differentially expressed). Notably, the eye transcript of regucalcin1 was recently characterized as fast-evolving across Heliconius species61. Other candidates include a cysteine protease, which functions in protein degradation, and might be linked to behaviour for example through degradation of neurotransmitters, a MORN motif containing protein (function unknown), and a WD40 containing protein. WD-repeat containing proteins have been implicated in a wide array of functions ranging from signal transduction to apoptosis (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro).

Although preference for red colouration and the optix gene are tightly linked, we find no evidence that optix is differentially expressed in the eyes or brains of our two species. It is also not located within the QTL peak (and it contains no non-synonymous changes in protein-coding regions20). It seems unlikely therefore that changes in cue and preference are pleiotropic effects of the same allele. More generally, although we have pinpointed the strongest candidates yet identified for assortative mating behaviours in Heliconius, it is possible that actual causal changes in gene regulation are restricted to developmental stages other those sampled, or restricted to a few neuronal populations not detected with transcriptomic data from eyes and whole brain tissue. Nonetheless, by sampling at two pupal stages (around the time of optix expression/ommochrome pigment deposit in the wing/eye and halfway through pupal development) and at the adult stage, we should have captured important transitions for the behavioural programming of the two species.

Work in the past decade has shown that complex innate behavioural differences between species can be encoded in relatively few genetic modules62,63, but very few studies64–67 have identified specific genes underlying behavioural evolution. Traditional laboratory organisms continue to provide important insights into the evolution and genetics of behaviour27,65,67; however, comparative approaches are required to determine if developmental principles can be broadly applied, and also to incorporate a wider range of phenotypic variation and sensory modalities. The challenge now is to increase the resolution of studies in non-traditional systems, in order to link individual genetic elements to behaviours, and the sensory and/or neurological structures through which they are mediated. In this light, and focussing on a genomic region that also contains a major gene for variation in warning pattern, we have identified a small handful of strong candidate genes associated with the evolution of visual mate preference behaviours in Heliconius. Because these genes are in tight physical linkage with the locus for the corresponding shifts in an ecologically relevant mating cue, they provide an important opportunity to investigate the build-up of genetic barriers crucial to speciation. A second QTL (on chromosome 1), not tightly linked to any known wing patterning genes, additionally influences courtship initiation in these species; although beyond the scope of the current study, it would nevertheless be interesting to investigate this region more thoroughly in future work. The candidate genes identified here seem more likely to alter visual processing or integration, rather than detection at photoreceptors, consistent with permitting changes in mate preference without altering perception of the animal’s wider environment.

Methods

Courtship initiation analyses

Butterfly rearing, crossing design and genotyping are described in detail elsewhere19. In brief, we assayed male preference behaviours for H. melpomene, H. cydno, their first generation (F1) hybrids and backcross hybrids to both parental species in standardized choice trials. Males were introduced into outdoor experimental cages (1 × 1 × 2 m) with a virgin female of each species and courtship behaviours recorded. Whenever possible, trials were repeated for each male (median = 5 trials). To determine whether previously identified QTLs for courtship time contribute to variation in courtship initiation behaviours, we performed a post-hoc analysis using categorical models in a Bayesian framework with a multinomial error structure, using the R package brms. All models were run under default priors (non- or very weakly informative). In contrast to our previous analysis19, in which we considered the number of minutes (i.e., time) for which courtship was directed towards H. cydno or H. melpomene females, here the response variable was the number of trials in which male courtship was initiated towards H. cydno females only, H. melpomene females only, or both female types (hereafter referred to as “initiation”). Across males the median number of trials with a response was 3. Using backcross-to-cydno males only, we fitted initiation as a response variable to genotype (cyd/cyd or cyd/melp) at each QTL, which were included as separate fixed effects. Individual ID was fitted as random factor. To test the effect of each QTL on male initiation, we compared the saturated model incorporating all three QTL with reduced models excluding each QTL in turn, using approximate leave-one-out cross-validation68 as implemented in brms, and based on expected log pointwise predictive density (ELPD). Normal distribution of ELPD can be a straightforward approximation given our large samples sizes (n = 139)68. Therefore, we considered an absolute value of ELPD greater than 1.96 units of its standard error as indicative of the reduced model being less-informative than the saturated model (95% confidence). Males that did not initiate courtship to any female across trials were excluded from the analyses, resulting in a dataset of 139 males, from a total of 146 backcross males for which we had genotype data. Finally, we extracted predictors and credibility intervals for backcross males with differing genotypes from the minimum adequate model. Credibility intervals for H. melpomene, H. cydno, F1 hybrid and backcross to melpomene males displayed in Fig. 1 were generated following the same procedures. Raw data and analysis code are available in the following github repository: https://github.com/SpeciationBehaviour/neural_genes_heliconius.git.

Butterfly collection, rearing and crossing design for expression analyses

Wild H. melpomene rosina and H. cydno chioneus individuals were caught along Pipeline Road near Gamboa, Panama, in the Soberania National Park, and used to establish stocks at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute insectaries in Gamboa. Butterflies were reared in common garden conditions, in 2 × 2 × 2 m cages, and provided with fresh Psiguria flowers and 10% sugar solution. Larvae were reared on fresh Passiflora shoots/leaves until pupation. H. cydno, H. melpomene and hybrid individuals used for RNA-seq (see below) were reared concurrently and under the same conditions. F1 hybrids were obtained by crossing a wild-caught H. m. rosina male to an insectary-bred virgin H. c. chioneus female.

Third-generation backcross hybrids (BC3) were generated by outcrossing a hybrid male with a red forewing band (crossing design shown in Supplementary Fig. 3) to virgin H. cydno females, over three generations. The peak of the behavioural QTL reported previously19 on chromosome 18 (at 0 cM) is in very tight linkage with the optix colour pattern locus (at 1.2 cM), which controls for the presence and absence of the red forewing band seen in H. melpomene rosina. The presence of the red forewing band is dominant over its absence so that segregation of the red band can be used to infer genotype at the optix locus. Specifically, hybrid individuals with a red forewing band are heterozygotes for H. melpomene/H. cydno alleles at the optix locus, whereas individuals lacking the red band are homozygous for the H. cydno allele. Due to the tight linkage we expected little recombination between optix and QTL peak even after three generations of introgression, allowing us to infer genotype at the preference-optix locus (which we confirmed with genetic data, see below).

Tissue dissection, RNA extraction and mRNA sequencing

Eye (ommatidia and retinal membrane) and brain tissues (central brain and optic lobes) were dissected out of the head capsule (as a single combined tissue) in cold (4 °C) 0.01 M PBS solution, at two pupal stages: 60 h APF and 156 h APF; and in adults aged 9–13 days in 2013. We sampled adults at around 10 days of age because by this stage males are mature and frequently court females69. Adult males and females sampled were sexually naive. We decided to sample at 60 h APF because this is the developmental stage at which optix is expressed in the wing, so we hypothesized that it might had also been when optix is expressed in the brain. We sampled at 156 h APF as a putative stage halfway through pupal development, and at this stage most of the major neural connections have just been established in the Heliconius brain (Stephen Montgomery, unpublished data).

Tissues were stored in RNAlater at 4 °C for 24 h, and subsequently at −20 °C, until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and a RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Samples were treated with DNase I (Ambion, Darmstadt, Germany). Integrity of total RNA was checked either on an agarose gel or using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA concentration was measured on a Nanodrop spectrophotomer. Illumina TruSeq RNA-seq libraries were prepared and sequenced at Edinburgh Genomics (Edinburgh, UK) with 100 bp paired-end reads (in 2014). To avoid lane effects the distribution of the species samples was randomized on the sequencing platform. More detailed information about individuals and sequencing yields can be found in Supplementary Data 1. In 2019, we independently sampled a further five H. melpomene, five H. cydno, and six F1 hybrids males, of 10 days of age. These F1 hybrids were generated by crossing a wild-caught H. c. chioneus male to an insectary-bred virgin H. m. rosina female. Briefly, for these, RNA was extracted similarly with Trizol Reagent and a PureLink RNA Mini Kit, with PureLink DNase digestion on column (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Illumina 150 bp paired-end RNA-seq libraries were prepared and sequenced at Novogene (Hong Kong, China).

RNA-seq read mapping and differential gene-expression analyses

After a quality control of RNA-seq reads with FastQC, we trimmed adaptor and low-quality bases using TrimGalore v.0.4.4 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/). RNA-seq reads were mapped to the H. melpomene 2.5 genome assembly29/annotation31 using STAR v.2.4.2a70 in two-pass mode. We only kept reads that mapped in ‘proper pairs’ using Samtools71. The number of reads mapping to each gene was estimated with HTseq v. 0.9.172 with model “union”, thus excluding ambiguously mapped reads. Differential gene-expression analyses between species/hybrids were conducted in DESeq273, including sequencing batch as random factor when comparing species samples from both datasets. We considered only those genes showing a twofold change in expression level, and at adjusted (false discovery rate 5%) p values < 0.05, to be differentially expressed, to exclude expression differences caused by known differences in brain morphology74, that in this species pair are clustered in the visual system75, although there is no evidence that visual mate preference is linked to these divergent brain morphologies.

Sexing pupae

In all DESeq2 analyses, sex was included as a random factor. To sex pupae, we first marked duplicate RNA mapped reads with Picard (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), and used GATK 3.876 to split uniquely mapped reads into exon segments and trim sequences overhanging the intronic regions. We then used HaplotypeCaller on each individual, using calling and filtering parameters according to the GATK Best Practices for variant calling on RNA-seq data. The sex of pupal samples was inferred from the proportion of heterozygous (biallelic) SNPs using the R package SNPstats. Males (ZZ) were expected to have ⪢ 0% heterozygous sites, whereas females (ZW) to have 0%. Z-linked heterozygosity of the pupal samples (Supplementary table 4) were in line with expectations (either ~0 for females or an order of magnitude higher for males), and matched heterozygosity of either adult males or females, for which the sex was determined from external morphology.

Inference of gene function and transcript-based annotation

Biological functions of annotated genes were inferred with InterProScan v577, using the corresponding Hmel2.5 predicted protein sequences. InterProScan uses different databases like InterPro, Pfam, PANTHER, and others, to infer functional protein domains and motifs (based on homology). To study whether specific biological functions were enriched among genes showing differential expression among hybrid types, we conducted the PANTHER enrichment test34 (with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing) using Drosophila melanogaster as the reference gene function database.

Upon detailed inspection of the mapping coverage of spliced RNA-seq reads to the Hmel2.5 gene annotation, we noticed that some gene models were fragmented, namely, a few exons that appeared to be spliced together were incorrectly considered distinct genes. To check that this did not introduced inaccuracies in our differential gene-expression analyses, we re-annotated the melpomene genome using the Cufflinks reference annotation-based transcript (RABT) assembly tool32 We used the transcriptomic data from both H. melpomene and H. cydno to reannotate the melpomene genome, separately for every developmental stage, and reconducted the differential gene-expression analyses in DESeq2 as described above. Repeating all comparative transcriptomic analyses using these new annotations (where exons were correctly considered as part of single genes), we confirmed that both regucalcin2 and Grik2 were differentially expressed in both species and hybrids comparisons.

Inference of BC3 hybrids genome composition

In order to perform comparative transcriptomic analyses between third-generation backcross hybrids (BC3) segregating at the QTL on chromosome 18 (crossing design in Supplementary Fig. 3), we first determined which genomic regions in these hybrids were heterozygous (cyd/melp) or homozygous (cyd/cyd). For this, we inferred variants from RNA-seq reads for each BC3 hybrid (individually as above), and from the combined H. melpomene and H. cydno samples. For the species, we used HaplotypeCaller76 on RNA-seq samples from all developmental stages of either species, to produce individual genomic records (gVCF), and then jointly genotyped H. melpomene and H. cydno gVCFs (separately for the two species) using genotypeGVCFs with default parameters. Genotype calls were filtered for quality by depth (QD) > 2, strand bias (FS) < 30 and allele depth (DP) > 4. For further analyses we kept biallelic genotypes only. We then used the intersect function of bcftools71 to infer variants exclusive to the H. cydno and to the H. melpomene samples.

We calculated the fraction of variants that each BC3 hybrid individual shared with the H. melpomene and with the H. cydno samples, in non-overlapping 100 kb windows. We compared these to the fraction of variants that a F1 hybrid and a H. cydno individual (not included in the combined genotyping of the H. cydno samples), shared with the same species samples, and found that they matched either one of them, indicating heterozygous (cyd/melp) or homozygous (cyd/cyd) regions (Supplementary Fig. 5B). In this analysis, we considered only those 100 kb windows where BC3 hybrids/F1 hybrid/H. cydno individuals shared more than 30 variants with the melpomene/cydno samples.

To corroborate our findings, we repeated the same type of analysis, this time inferring species-specific variants for H. melpomene and H. cydno using 10 H. melpomene rosina and 10 H. cydno chioneus genome resequencing samples. Variant calling files (vcf) were retrieved from Martin et al.37 We considered only biallelic genotype calls that had 10 < DP < 100 and genotype quality >30. With this analysis we found the same heterozygous and homozygous regions in BC3 hybrids.

The size and number of the introgressed regions were in line with expectations about 3rd generation backcross hybrids following our crossing design: segregating at the level of chromosome 18 and at four other chromosomes. For the BC3 hybrids sampled at 156 h APF we had 6 cyd/melp and 10 cyd/cyd at the QTL region on chromosome 18 (Supplementary Fig. 5A), for those at 60 h APF, 8 cyd/melp and 9 cyd/cyd hybrids at the same region. The average percentage of the genome that is heterozygous (cyd/melp) as opposed to homozygous (cyd/cyd) outside of chromosome 18 was ~6% (close to the expectation that a 3rd generation backcross genome should be 1/16 heterozygous (cyd/melp)).

Allele specific expression in hybrids

In order to conduct allele specific expression analyses we first identified species-specific variants, fixed in either H. melpomene and H. cydno. For this, we took the quality filtered variants inferred from the species genome resequencing data, and assigned those genotype calls in H. cydno and H. melpomene for which allele frequency (AF) was >0.9 as homozygous (we did not consider indels in this analysis). We then used bcftools intersect71 to get only those variants for which H. cydno and H. melpomene had opposite alleles.

At the same time, we called variants from RNA-seq reads of F1 hybrid individuals (using F1 hybrids from both datasets), again according to the GATK Best Practices (with the exception of parameters -window 35 -cluster 3, to increase SNPs density), and selected only heterozygous SNPs in F1s that matched the species-specific variants. Finally, we used GATK’s ASEReadCounter76, with option “-drf DuplicateRead” (without deduplicating RNA reads), to count RNA reads in the F1 hybrids (and later on in BC3 hybrids) that mapped to either the H. cydno or the H. melpomene allele. We summed all reads mapping to either the H. cydno or H. melpomene allele/variant within the same gene (both for gene models of the Hmel2.5 gene annotation and for the Cufflinks annotation we assembled previously). To test for allele-specific expression (diffASE) we fitted the model “~0 + individual + allele” in DESeq273, setting library size factors to 1 (thus not normalizing between samples, as the test for diffASE is conducted within individuals). We only considered those alleles showing at least a twofold change in expression and p < 0.05, as differentially expressed.

In order to check that there were no biases in alleles assignment to one of the two species, we analyzed the ratios of the species alleles, for every gene, and checked that they were not systematically biased to either one of the two species. The log2 fold changes of the species alleles were centred around 0, suggesting no obvious bias in alleles assignment78 (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Protein-coding substitutions and predicted effects on protein-function

We inferred fixed variants in protein-coding regions from the combined H. melpomene and H. cydno RNA samples in order to include variants from genes for which we detected expression in the brain/eyes across the 3 stages. We took the quality filtered variants called from the joint genotyping of RNA-seq data of H. cydno and H. melpomene (from all stages, these did not include adult samples from the more recent sequencing batch), and selected those genotype calls for which AF >0.8, and where the allelic variant was present in at least 7 individuals of the ~30 samples (for each species). We retained those substitutions/indels validated with the genome resequencing data. For this, of the genotype calls found in RNA reads from brain/eyes of different stages, we kept only those that were also called in at least 8 of the 10 genome resequencing samples of each species. We considered this overlapping set of variants as being fixed in H. melpomene rosina or H. cydno chioneus. Following a similar approach to Bendesky et al.66, we then restricted this set of substitutions between H. cydno and H. melpomene to protein-coding regions, and selected those non-synonymous substitutions that were considered to have moderate or high effect on protein function with SNPEff79. Finally, we used the PROVEAN algorithm35, to further study the functional effects of these substitutions on protein function. The PROVEAN algorithm predicts the functional effect of protein sequence variations based on how they affect alignments to homologous protein sequences (for this we used the PROVEAN protein database online). We selected those amino acid changes with the suggested PROVEAN score <−2.5, indicating non-neutral effect on protein function.

Admixture analyses

We retrieved estimated admixture proportions between H. melpomene rosina and H. cydno chioneus, for 100 kb and 20 kb windows, from Martin et al.37.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Chi-Yun Kuo, Liz Evans, Adriana Tapia, Moises Abanto and Morgan Oberweiser for help and assistance in the insectaries. We are grateful to Ana Pinharanda for sharing the H. cydno genome assembly and annotation and to Simon Martin for sharing admixture proportions and comments on the manuscript. We thank the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute for providing research infrastructure, the Ministerio del Ambiente for permission to collect butterflies in Panama, Edinburgh Genomics and Novogene for sequencing support and Jochen Wolf who kindly provided computational resources. M.R., A.E.H. and R.M.M. are supported by an Emmy Noether fellowship and research grant awarded to R.M.M. by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeischaft (DFG) (Grant Number: GZ: ME 4845/1-1). R.M.M. was also supported by a Junior Research Fellowship from King’s College Cambridge, an Ernst Mayr fellowship from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, a Varley-Gradwell fellowship from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and the Balfour-Browne Fund, University of Cambridge. This project was also supported by the Puerto Rico Science, Technology and Research Trust (ARG 2020-00138), the Institutional Development Award (IdeA) INBRE NIH/NIGMS (award number P20 GM103475) and a National Science Foundation EPSCoR RII Track-2 FEC (award number OIA-1736026) to RP, and a European Research Council (ERC) awarded to CDJ (Grant number: 339873).

Author contributions

R.M.M. and M.R. conceived the study and designed the experiments, with input from W.O.M. and C.D.J.; M.R. analysed expression and sequence data; A.E.H. analysed the behavioural data; M.R., T.J.T., S.H.M. and R.M.M. reared butterflies, dissected neural tissue and extracted RNA; R.M.M., C.D.J. and W.O.M. secured funding, contributed resources and provided supervision; R.P. additionally secured funding and contributed resources; M.R. and R.M.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

RNA-seq data (raw reads) have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (accession number: PRJEB39935). Individual samples’ accession numbers and detailed metadata are reported in Supplementary Data 1. Previously published genomic data are available at: [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB1749] and at [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJEB11772].

Code availability

Analysis scripts and behavioural data are available at: https://github.com/SpeciationBehaviour/neural_genes_heliconius.git

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Molly Cummings, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Matteo Rossi, Email: rossi@bio.lmu.de.

Richard M. Merrill, Email: merrill@bio.lmu.de

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18609-z.

References

- 1.Coyne, J. A., Orr, H. A. Speciation (Sinauer, Sunderland, MA, 2004).

- 2.Rosenthal, G. G. Mate Choice (Princeton University Press, 2017).

- 3.Mayr, E. Animal Species and Evolution (Harvard University Press, 1963).

- 4.Arguello JR, Benton R. Open questions: tackling Darwin’s “instincts”: the genetic basis of behavioural evolution. BMC Biol. 2017;15:8–10. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0369-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bay RA, et al. Genetic coupling of female mate choice with polygenic ecological divergence facilitates stickleback speciation. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:3344–3349. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahandeh MP, Pischedda A, Rodriguez JM, Turner TL. The genetics of male pheromone preference difference between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020;10:401–415. doi: 10.1534/g3.119.400780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gould F, et al. Sexual isolation of male moths explained by a single pheromone response QTL containing four receptor genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:8660–8665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910945107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leary GP, et al. Single mutation to a sex pheromone receptor provides adaptive specificity between closely related moth species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:14081–14086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204661109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan P, et al. Genetic and neural mechanisms that inhibit Drosophila from mating with other species. Cell. 2013;154:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand P, et al. The evolution of sexual signaling is linked to odorant receptor tuning in perfume-collecting orchid bees. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu M, Shaw KL. Genetic coupling of signal and preference facilitates sexual isolation during rapid speciation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2019;286:20191607. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seehausen O, et al. Speciation through sensory drive in cichlid fish. Nature. 2008;455:620–626. doi: 10.1038/nature07285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hench K, Vargas M, Höppner MP, McMillan WO, Puebla O. Inter-chromosomal coupling between vision and pigmentation genes during genomic divergence. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:657–667. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merrill RM, et al. Disruptive ecological selection on a mating cue. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012;279:4907–4913. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiggins CD, Naisbit RE, Coe RL, Mallet J. Reproductive isolation caused by colour pattern mimicry. Nature. 2001;411:302–305. doi: 10.1038/35077075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Servedio MR, Van Doorn GS, Kopp M, Frame AM, Nosil P. Magic traits in speciation: ‘magic’ but not rare? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011;26:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiggins CD. Ecological speciation in mimetic butterflies. Bioscience. 2008;58:541–548. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiggins CD, Estrada C, Rodrigues A. Mimicry and the evolution of premating isolation in Heliconius melpomene Linnaeus. J. Evol. Biol. 2004;17:680–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merrill RM, et al. Genetic dissection of assortative mating behaviour. PLoS Biol. 2018;17:e2005902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed RD, et al. Optix drives the repeated convergent evolution of butterfly wing pattern mimicry. Science. 2011;333:1137–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.1208227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin A, et al. Diversification of complex butterfly wing patterns by repeated regulatory evolution of a Wnt ligand. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12632–12637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204800109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadeau NJ, et al. The gene cortex controls mimicry and crypsis in butterflies and moths. Nature. 2016;534:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature17961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felsenstein J. Skepticism Towards Santa Rosalia, or why are there so few kinds of animals? Evolution. 1981;35:124–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1981.tb04864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massey JH, Chung D, Siwanowicz I, Stern DL, Wittkopp PJ. The yellow gene influences Drosophila male mating success through sex comb melanization. Elife. 2019;8:1–20. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merrill RM, Van Schooten B, Scott JA, Jiggins CD. Pervasive genetic associations between traits causing reproductive isolation in Heliconius butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011;278:511–518. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Schooten B, et al. Divergence of chemosensing during the early stages of speciation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:16348–16447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921318117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seeholzer LF, Seppo M, Stern DL, Ruta V. Evolution of a central neural circuit underlies Drosophila mate preferences. Nature. 2018;559:564–569. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin SH, et al. Genome-wide evidence for speciation with gene flow in Heliconius butterflies. Genome Res. 2013;23:1817–1828. doi: 10.1101/gr.159426.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davey J, et al. Major improvements to the Heliconius melpomene genome assembly used to confirm 10 chromosome fusion events in 6 million years of butterfly evolution. G3. 2015;6:695–708. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.023655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darragh, K. et al. A novel terpene synthase produces an anti-aphrodisiac pheromone in the butterfly Heliconius melpomene. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/779678v1 (2019).

- 31.Pinharanda A, et al. Sexually dimorphic gene expression and transcriptome evolution provide mixed evidence for a fast-Z effect in Heliconius. J. Evol. Biol. 2019;32:194–204. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-seq. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2325–2329. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittkopp PJ, Haerum BK, Clark AG. Evolutionary changes in cis and trans gene regulation. Nature. 2004;430:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature02698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas PD, et al. Applications for protein sequence-function evolution data: mRNA/protein expression analysis and coding SNP scoring tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:645–650. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin SH, Davey JW, Jiggins CD. Evaluating the use of ABBA-BABA statistics to locate introgressed loci. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:244–257. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin SH, Davey JW, Salazar C, Jiggins CD. Recombination rate variation shapes barriers to introgression across butterfly genomes. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:1–28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nosil, P. Ecological Speciation (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- 39.Kopp M, et al. Mechanisms of assortative mating in speciation with gene flow: connecting theory and empirical research. Am. Nat. 2018;191:1–20. doi: 10.1086/694889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butlin RK, Smadja CM. Coupling, reinforcement, and speciation. Am. Nat. 2018;191:155–172. doi: 10.1086/695136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westerman EL, et al. Aristaless controls butterfly wing color variation used in mimicry and mate choice. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:3469–3474. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kronfrost MR, et al. Linkage of butterfly mate preference and wing color preference cue at the genomic location of wingless. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6575–6580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509685103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamberlain NL, Hill RI, Kapan DD, Gilbert LE, Kronforst MR. Polymorphic butterfly reveals the missing link in ecological speciation. Science. 2009;326:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1179141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCulloch KJ, et al. Sexual dimorphism and retinal mosaic diversification following the evolution of a violet receptor in butterflies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:2271–2284. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaccardi G, Kelber A, Sison-Mangus MP, Briscoe AD. Colour discrimination in the red range with only one long-wavelength sensitive opsin. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:1944–1955. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monteiro A. Gene regulatory networks reused to build novel traits. BioEssays. 2012;34:181–186. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin A, et al. Multiple recent co-options of optix associated with novel traits in adaptive butterfly wing radiations. Evodevo. 2014;5:7. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H., Jessell, T. M., Siegelbaum, S. A. & Hudspeth. A. J. Principles of Neural Science, 2012th edn. (McGraw Hill, New York, 2000).

- 49.Ramsey ME, Vu W, Cummings ME. Testing synaptic plasticity in dynamic mate choice decisions: N-methyl d-aspartate receptor blockade disrupts female preference. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20140047. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloch NI, et al. Early neurogenomic response associated with variation in guppy female mate preference. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:1772–1781. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0682-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delclos, P. J., Forero, S. A. & Rosenthal, G. G. Divergent neurogenomic responses shape social learning of both personality and mate preference. J. Evol. Biol. 223 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Yamaguchi M. Role of regucalcin in brain calcium signaling. Integr. Biol. 2012;4:825–837. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20042b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berridge MJ. Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron. 1998;21:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bashaw GJ, Klein R. Signaling from axon guidance receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:1–17. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prud’homme B, Gompel N, Carroll SB. Emerging principles of regulatory evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8605–8612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700488104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preger-Ben Noon E, et al. Comprehensive analysis of a cis-regulatory region reveals pleiotropy in enhancer function. Cell Rep. 2018;22:3021–3031. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis J, et al. Parallel evolution of ancient, pleiotropic enhancers underlies butterfly wing pattern mimicry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:24174–24183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907068116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chouteau M, Llaurens V, Piron-Prunier F, Joron M. Polymorphism at a mimicry supergene maintained by opposing frequency-dependent selection pressures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:8325–8329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702482114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Southcott L, Kronforst MR. Female mate choice is a reproductive isolating barrier in Heliconius butterflies. Ethology. 2018;124:862–869. doi: 10.1111/eth.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.González-Rojas MF, et al. Chemical signals act as the main reproductive barrier between sister and mimetic Heliconius butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. 2020;287:20200587. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W, et al. Comparative transcriptomics provides insights into reticulate and adaptive evolution of a butterfly radiation. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019;11:2963–2975. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weber JN, Peterson BK, Hoekstra HE. Discrete genetic modules are responsible for complex burrow evolution in Peromyscus mice. Nature. 2013;493:402–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cande J, Andolfatto P, Prud’homme B, Stern DL, Gompel N. Evolution of multiple additive loci caused divergence between Drosophila yakuba and D. santomea in wing rowing during male courtship. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McBride CS, et al. Evolution of mosquito preference for humans linked to an odorant receptor. Nature. 2014;515:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature13964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ding Y, Berrocal A, Morita T, Longden KD, Stern DL. Natural courtship song variation caused by an intronic retroelement in an ion channel gene. Nature. 2016;536:329–332. doi: 10.1038/nature19093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bendesky A, et al. The genetic basis of parental care evolution in monogamous mice. Nature. 2017;544:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nature22074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Auer TO, et al. Olfactory receptor and circuit evolution promote host specialization. Nature. 2020;579:402–408. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vehtari A, Gelman A, Gabry J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 2017;27:1413–1432. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiggins, C. D. The Ecology and Evolution of Heliconius Butterflies (Oxford University Press, 2016).

- 70.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq- a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Montgomery SH, Mank JE. Inferring regulatory change from gene expression: the confounding effects of tissue scaling. Mol. Ecol. 2016;25:5114–5128. doi: 10.1111/mec.13824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Montgomery, S. H., Rossi, M., McMillan, W. O. & Merrill, R. Neural divergence and hybrid disruption between ecologically isolated Heliconius butterflies. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.01.182337v1 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.McKenna A, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Finn RD, et al. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D190–D199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.York RA, et al. Behaviour-dependent cis regulation reveals genes and pathways associated with bower building in cichlid fishes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:1081–1090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810140115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cingolani P, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly. 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data (raw reads) have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (accession number: PRJEB39935). Individual samples’ accession numbers and detailed metadata are reported in Supplementary Data 1. Previously published genomic data are available at: [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB1749] and at [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJEB11772].

Analysis scripts and behavioural data are available at: https://github.com/SpeciationBehaviour/neural_genes_heliconius.git