Abstract

Background

The present study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib and verify the possibility of lenvatinib for the expanded indication from the REFLECT trial in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in real-world practice, primarily focusing on the population that was excluded in the REFLECT trial.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data on patients with advanced HCC who were administered lenvatinib in 7 institutions in Japan.

Results

Of 152 advanced HCC patients, 95 and 57 patients received lenvatinib in first-line and second- or later-line systemic therapies, respectively. The median progression-free survival in Child-Pugh class A patients was nearly equal between first- and second- or later-line therapies (5.2 months; 95% CI 3.7–6.9 for first line, 4.8 months; 95% CI 3.8–5.9 for second or later line, p = 0.933). According to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, the objective response rate of 27 patients (18%) who showed a high burden of intrahepatic lesions (i.e., main portal vein and/or bile duct invasion or 50% or higher liver occupation) at baseline radiological assessment was 41% and similar with that of other population. The present study included 20 patients (13%) with Child-Pugh class B. These patients observed high frequency rates of liver function-related adverse events due to lenvatinib. The 8-week dose intensity of lenvatinib had a strong correlation with liver function according to both the Child-Pugh and albumin − bilirubin scores.

Conclusion

Lenvatinib had potential benefits for patients with advanced HCC with second- or later-line therapies and a high burden of intrahepatic lesions. Dose modification should be paid increased attention among patients with poor liver function, such as Child-Pugh class B patients.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Lenvatinib, REFLECT trial

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third-most frequent cause of cancer deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Until the early 2000s, treatment for HCC primarily focused on removing or controlling intrahepatic lesions. Hepatic resection, local ablation, and transarterial chemoembolization have made remarkable progress during this period [3, 4, 5, 6]. On the contrary, developments of systemic therapies for patients with advanced HCC who were not indicated for hepatic resection or locoregional therapies, as mentioned above, have not shown adequate advancement. In 2007, the Sorafenib HCC Assessment Randomized Protocol trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, demonstrated that sorafenib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) versus placebo in patients with advanced HCC in the Western population [7]. Similarly, an Asia Pacific trial duplicated the finding that sorafenib administration showed a survival benefit in Eastern patients with advanced HCC [8]. On the basis of these 2 randomized controlled trials, sorafenib has been recommended as the only first-line oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor for advanced HCC worldwide for nearly a decade. Although several novel compounds had been developed as both first- and second-line treatments, to the best of our knowledge, none have shown significant survival benefits in phase III studies until regorafenib administration demonstrated a survival benefit in the second-line setting in 2016 [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

In 2017, lenvatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1 through 3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 through 4, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β, and the RET and KIT oncogenes, demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with HCC in a phase III trial (REFLECT trial), which confirmed the noninferiority of lenvatinib to sorafenib for OS [17]. In accordance with the results of the REFLECT trial, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in Japan approved lenvatinib for patients with advanced HCC, and it has been available for use in clinical practice since March 23, 2018.

Generally, clinical trials set strict enrollment criteria that include patients who are most likely to benefit from the testing drug, and trials are not designed to include all representative populations who may be eligible to use the agents in real-world practice. The REFLECT trial included only Child-Pugh class A patients and excluded patients with a high burden of intrahepatic lesions. In clinical practice, a large number of patients who have a high burden of intrahepatic lesions or worse liver functioning (Child-Pugh class B) require systemic therapy in advanced HCC. In this retrospective study, we investigated the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in Japanese patients with advanced HCC after lenvatinib approval and primarily focused on populations that were excluded from the REFLECT trial, which complemented the results of other clinical trials of lenvatinib in patients with advanced HCC.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively collected data of patients with advanced HCC who received lenvatinib in 7 institutions in Japan between March 23, 2018 (date of lenvatinib approval in Japan) and January 31, 2019. Data were locked on June 30, 2019. The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University (no 2896). We had access to information that could identify individual patients during or after data collection. Patient data were anonymized and de-identified before analysis.

Treatment with Lenvatinib

Patients were administered lenvatinib at the dose required to maintain performance status, adequate bone marrow, and both liver and renal functioning. Confirmation of Child-Pugh class A at the time of initiating lenvatinib administration was recommended. However, limited Child-Pugh class B patients were allowed to use by the decision of specialists concerning HCC treatment. In Child-Pugh class A patients, a standard starting dose of lenvatinib consists of 12 and 8 mg orally once per day for patients weighing 60 kg or more and <60 kg, respectively. A starting dose of lenvatinib in Child-Pugh class B patients was 8 mg orally once per day on the basis of a previous early-phase clinical trial [18]. We applied dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at baseline and every 1–2 months after starting treatment for the evaluation of tumor response.

Clinical Parameters

Clinical parameters of this study were retrospectively retrieved from 7 institutions in Japan as follows: baseline demographic data of lenvatinib (e.g., sex, age, etiology, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, Child-Pugh class, radiological assessment, alpha-fetoprotein [AFP], treatment before lenvatinib initiation, and initial and final lenvatinib doses), adverse events (AE) after the initiation of lenvatinib, date of radiological progression, date of death or last follow-up, and dose intensity of lenvatinib.

Radiological assessments were evaluated according to both Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and modified RECIST (mRECIST) [19, 20]. Separately, the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 protocol was used for the assessment of AE. In the present study, we focused on an incidence rate of hepatic encephalopathy during treatments with lenvatinib. Hepatic encephalopathy was evaluated by a term of “encephalopathy” according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0, which was modified based on the Inuyama classification of hepatic encephalopathy (online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000507022) [21].

We also retrospectively evaluated the presence or absence of a portosystemic shunt (P-S shunt) at the baseline examinations. In the present study, a P-S shunt was defined as any of the following findings: (1) esophageal and/or gastric varices according to upper endoscopy or dynamic contrast CT or MRI or (2) a paraumbilical vein, gastrorenal shunt, or any other apparent findings of collateral circulation from the portal system to the systemic circulation according to dynamic contrast CT or MRI.

Statistical Analysis

Kaplan-Meier plots of medians with 95% CIs were used for estimating OS. The censoring date was defined as the date of the last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) after lenvatinib was estimated using Kaplan-Meier plots of medians with 95% CIs, with the progression date defined according to mRECIST and the censoring date defined as the date of last radiological assessment without progression. Logistic regression analysis was performed for assessing the factors for hepatic encephalopathy occurrence. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25 statistical software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics, Efficacy, and Safety of the Whole Population of the Present Study

Between March 23, 2018, and January 31, 2019, 152 patients were identified as candidates for receiving lenvatinib administration at 7 Japanese institutions. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the present study. The median age of patients in the present study was 73 years old. The most common etiology was hepatitis C virus (45%), followed by alcohol abuse (25%) and hepatitis B virus (13%). The majority of the patients were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status grade 0 or 1 (93%) and Child-Pugh class A (87%). At the baseline radiological assessments, 23 and 38% of patients were found to have macrovascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis, respectively. Of the 152 patients, 95 patients (62%) and 57 patients (38%) started lenvatinib as first-line and second- or later-line therapies, respectively. According to the baseline radiological assessments, 27 patients (18%) had main portal vein and/or bile duct invasion or 50% or higher liver occupation by an intrahepatic tumor and conflicted with the radiological exclusion criteria of the REFLECT trial. We defined this population as the “high burden of intrahepatic lesions” group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 152 patients with HCC treated with lenvatinib

| Demographics/characteristics | Any patients (n = 152) | Child-Pugh class |

Prior systemic therapy |

High burden of intrahepatic lesion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 132) | B (n = 20) | absent (1st line) (n = 95) | present (2nd or later line) (n = 57) | absent (n = 125) | present (n = 27) | ||

| Gender, male | 128 (84) | 112 (85) | 16 (80) | 75 (79) | 53 (93) | 104 (83) | 24 (90) |

| Age, years, >73 | 74 (49) | 65 (50) | 9 (45) | 48 (51) | 26 (46) | 66 (53) | 8 (30) |

| HBV positive | 20 (13) | 18 (14) | 2 (10) | 13 (14) | 7 (12) | 15 (12) | 5 (19) |

| HCV positive | 69 (45) | 61 (46) | 8 (40) | 41 (43) | 28 (49) | 63 (50) | 6 (22) |

| Alcohol abuse | 38 (25) | 32 (24) | 6 (30) | 28 (30) | 10 (18) | 29 (23) | 9 (33) |

| Body weight, <60 kg | 74 (49) | 66 (50) | 8 (40) | 45 (47) | 29 (51) | 58 (46) | 16 (59) |

| ECOG-PS, ≤1 | 142 (93) | 123 (93) | 19 (95) | 90 (95) | 52 (91) | 118 (94) | 23 (89) |

| Child-Pugh score | |||||||

| <5 | 70 (46) | 70 (53) | 0 | 47 (49) | 23 (40) | 63 (50) | 7 (26) |

| 6 | 62 (41) | 62 (47) | 0 | 37 (39) | 25 (44) | 46 (37) | 16 (59) |

| >7 | 20 (13) | 0 | 20 (100) | 11 (12) | 9 (16) | 16 (13) | 4 (15) |

| Number of intrahepatic lesions, >7 | 70 (46) | 62 (47) | 8 (40) | 44 (46) | 26 (46) | 57 (46) | 13 (48) |

| Maximum size of intrahepatic lesions, >50 mm | 51 (34) | 43 (33) | 8 (40) | 33 (35) | 18 (32) | 35 (28) | 16 (59) |

| Intrahepatic tumor occupation, ≥50% | 11 (7) | 8 (6) | 3 (15) | 7 (7) | 4 (7) | 0 | 11 (100) |

| MVI | 35 (23) | 31 (24) | 4 (20) | 25 (26) | 10 (18) | 14 (11) | 21 (78) |

| Main portal invasion | 12 (8) | 10 (7) | 2 (10) | 9 (10) | 3 (5) | 0 | 12 (44) |

| Bile duct invasion | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 | 4 (15) |

| EHM | 57 (38) | 48 (36) | 9 (45) | 33 (35) | 24 (42) | 50 (40) | 87 (26) |

| BCLC stage C | 99 (65) | 85 (64) | 14 (70) | 64 (67) | 35 (61) | 73 (36) | 11 (41) |

| AFP, >400 ng/mL | 56 (37) | 48 (36) | 8 (40) | 36 (38) | 20 (35) | 45 (36) | 11 (41) |

| Pretreatment | 132 (87) | 115 (87) | 17 (85) | 75 (79) | 57 (100) | 115 (92) | 17 (63) |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; MVI, macrovascular invasion; EHM, extrahepatic metastasis; BCLC, Barcelona clinic liver cancer; AFP, alfa-fetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Regarding the cutoff date, the median observation period was 6.7 months (95% CI 6.2–7.3 months) and 95 patients (62%) had discontinued lenvatinib. Discontinued rates due to disease progression and AE were 38% (58 patients) and 21% (32 patients), respectively. The median duration of treatment with lenvatinib was 5.3 months (95% CI 4.5–6.1 months). The median PFS and OS were 5.1 months (95% CI 4.4–5.9 months) and 13.3 months (95% CI 9.9–16.7 months), respectively. According to RECIST and mRECIST, 16% and 41% patients achieved objective response during lenvatinib therapy (Table 2). Among the 113 patients with AFP levels of >20 ng/mL at baseline, 61 patients (54%) experienced a decrease in AFP level by >20%.

Table 2.

Best response, objective response rate, and disease control rate during lenvatinib treatments

| Any patients (n = 152) |

Child-Pugh class |

Prior systemic therapy |

High burden of intrahepatic lesion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 132) | B (n = 20) | absent (1st line) (n = 95) | present (2nd line or later) (n = 57) | absent (n = 125) | present (n = 27) | ||

| RECIST | |||||||

| Complete response | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (4) |

| Partial response | 22 (15) | 21 (16) | 1 (5) | 14 (15) | 8 (14) | 17 (14) | 5 (19) |

| Stable disease | 78 (51) | 67 (51) | 11 (55) | 47 (50) | 31 (54) | 69 (56) | 9 (33) |

| Progressive disease | 29 (19) | 24 (18) | 5 (25) | 17 (18) | 12 (21) | 21 (17) | 8 (30) |

| Objective response rate | 24 (16) | 23 (18) | 1 (5) | 16 (17) | 8 (14) | 18 (15) | 6 (23) |

| Disease control rate | 102 (67) | 90 (68) | 12 (60) | 63 (66) | 39 (68) | 87 (70) | 15 (56) |

| mRECIST | |||||||

| Complete response | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Partial response | 59 (39) | 49 (37) | 10 (50) | 40 (42) | 19 (33) | 48 (38) | 11 (41) |

| Stable disease | 42 (27) | 39 (30) | 3 (15) | 23 (24) | 19 (32) | 34 (27) | 8 (30) |

| Progressive disease | 27 (18) | 24 (18) | 3 (15) | 14 (15) | 13 (23) | 22 (18) | 5 (19) |

| Objective response rate | 62 (41) | 52 (39) | 10 (50) | 42 (44) | 20 (35) | 51 (41) | 11 (41) |

| Disease control rate | 104 (68) | 91 (60) | 13 (65) | 65 (68) | 39 (68) | 85 (68) | 24 (70) |

RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; mRECIST, modified RECIST.

Figure 1 presents the timing of response and duration for the individual responders among patients with advanced HCC who were administered lenvatinib. The median duration from lenvatinib administration to confirming radiological response was 8.0 weeks (95% CI 7.0–9.0 weeks). Of the 62 patients who achieved a response, 17 and 13 patients discontinued lenvatinib due to radiological progression and AE, respectively. The median duration of a continued response was not reached, and 14 patients (23%) had a continued response for >6 months.

Fig. 1.

Response and duration for responders with a best objective response of confirmed complete or partial responses. The discontinuation rate due to AE in responder patients was 11% (3 patients), 16% (4 patients), and 60% (6 patients) according to Child-Pugh scores of 5, 6, and 7 or more points, respectively. AE, adverse events.

Table 3 shows lenvatinib-related AE in our population. The most frequently occurring AE were hypothyroidism (63 patients, 41%), anorexia (63 patients, 41%), fatigue (58 patients, 38%), hypertension (43 patients, 28%), and loss of body weight (41 patients, 27%). The most common grade 3 or higher AE were hypertension (11 patients, 7%), elevated aspartate transaminase (AST; 11 patients, 7%), and proteinuria (10 patients, 6%). During the follow-up period, 120 patients (79%) required a dose modification of lenvatinib due to AE. The most common causes of dose modification were anorexia (33 patients, 22%), fatigue (24 patients, 16%), encephalopathy (18 patients, 12%), elevated AST (11 patients, 7%), palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (11 patients, 7%), and proteinuria (11 patients, 7%). The rates of dose modifications within 2 weeks, 2–4 weeks, and after 4 weeks from starting lenvatinib were 33% (50 patients), 15% (23 patients), and 31% (47 patients), respectively. The most common causes of treatment discontinuation due to AE were bleeding (6 patients, 4%), anorexia (5 patients, 3%), and fatigue (4 patients, 3%).

Table 3.

AE during lenvatinib treatment (>10%)

| Any patients (n = 152) | Child-Pugh class |

Prior systemic therapy |

High burden of intrahepatic lesion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 132) | B (n = 20) | absent (1st line) (n = 95) | present (2nd or later line) (n = 57) | absent (n = 125) | present (n = 27) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | |||||||

| Any grade | 63 (41) | 58 (44) | 5 (25) | 44 (37) | 19 (33) | 53 (42) | 10 (37) |

| Grade ≥3 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Anorexia | |||||||

| Any grade | 63 (41) | 52 (39) | 11 (55) | 37 (39) | 26 (46) | 52 (42) | 11 (41) |

| Grade ≥3 | 7 (5) | 6 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (3) | 4 (7) | 7 (6) | 0 |

| Fatigue | |||||||

| Any grade | 58 (38) | 47 (36) | 11 (55) | 39 (41) | 19 (33) | 50 (41) | 8 (30) |

| Grade ≥3 | 8 (5) | 6 (5) | 2 (10) | 6 (6) | 2 (4) | 7 (6) | 1 (4) |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| Any grade | 43 (28) | 38 (29) | 5 (25) | 25 (26) | 18 (32) | 32 (26) | 11 (41) |

| Grade ≥3 | 11 (7) | 9 (7) | 2 (10) | 6 (6) | 5 (9) | 9 (7) | 2 (7) |

| Bodyweight loss | |||||||

| Any grade | 41 (27) | 34 (26) | 7 (35) | 27 (28) | 14 (25) | 31 (25) | 10 (37) |

| Grade ≥3 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase | |||||||

| Any grade | 37 (24) | 28 (21) | 9 (45) | 22 (23) | 15 (26) | 30 (24) | 7 (26) |

| Grade >3 | 11 (7) | 8 (6) | 4 (20) | 7 (7) | 4 (7) | 6 (5) | 5 (19) |

| Proteinuria | |||||||

| Any grade | 37 (24) | 32 (24) | 5 (25) | 25 (26) | 12 (21) | 32 (26) | 5 (19) |

| Grade ≥3 | 10 (7) | 8 (6) | 2 (10) | 9 (9) | 1 (2) | 9 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia | |||||||

| Any grade | 35 (23) | 34 (26) | 1 (5) | 19 (20) | 16 (28) | 32 (26) | 3 (11) |

| Grade ≥3 | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | |||||||

| Any grade | 33 (22) | 32 (24) | 1 (5) | 21 (22) | 12 (21) | 31 (25) | 2 (7) |

| Grade ≥3 | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 0 | 7 (7) | 0 | 6 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Diarrhea | |||||||

| Any grade | 33 (22) | 24 (18) | 9 (45) | 19 (20) | 14 (25) | 25 (20) | 8 (30) |

| Grade ≥3 | 7 (5) | 5 (4) | 2 (10) | 3 (3) | 4 (7) | 5 (4) | 2 (7) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |||||||

| Any grade | 20 (13) | 14 (11) | 6 (30) | 12 (13) | 8 (14) | 16 (13) | 4 (15) |

| Grade ≥3 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Bilirubin elevation | |||||||

| Any grade | 20 (13) | 15 (11) | 5 (25) | 12 (13) | 8 (14) | 16 (13) | 4 (15) |

| Grade ≥3 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Hoarseness | |||||||

| Any grade | 19 (13) | 19 (14) | 0 | 8 (8) | 11 (19) | 16 (13) | 3 (11) |

| Grade ≥3 | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 |

AE, adverse events.

Efficacy and Safety of Lenvatinib Focusing on Patients Who Had a Previous History of Systemic Therapy and a “High Burden of Intrahepatic Lesions”

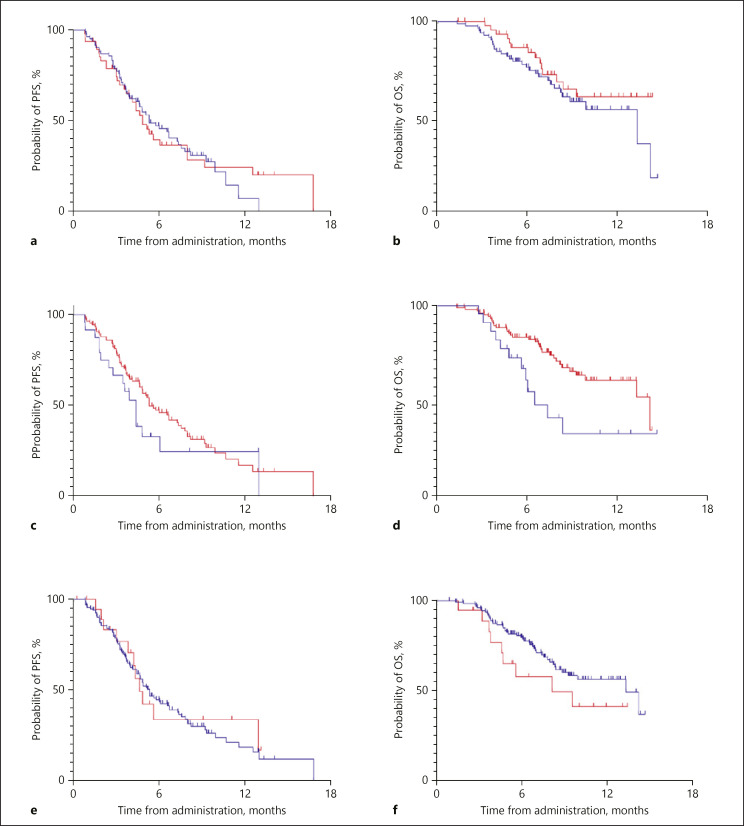

The median PFSs of Child-Pugh class A patients who received lenvatinib as first- and second- or later-line therapies were 5.2 months (95% CI 3.7–6.9 months) and 4.8 months (95% CI 3.8–5.9 months), respectively (p = 0.933; Fig. 2a). The median OSs of first- and second- or later-line patient with Child-Pugh class A were 13.3 months (95% CI 7.2–19.4 months) and not reached, respectively (p = 0.241; Fig. 2b). The median PFSs and OSs of first- and second- or later-line patients with the whole population in our cohort are also demonstrated in online supplementary Figure 1a and b, respectively (PFS, first line: 5.1, 95% CI 3.9–6.2 months, second or later line: 5.1, 95% CI 4.2–6.1 months, p = 0.448; OS, first line: 13.3, 95% CI 7.1–19.6 months, second or later line: not reached, p = 0.233). The objective response rate (ORR) in patients with first- and second- or later-line therapies were 44 and 35%, respectively (Table 2). We also compared efficacy of lenvatinib in Child-Pugh class A patients between the high burden of intrahepatic lesions group and the others; PFSs of both were 4.4 months (95% CI 3.3–5.5 months) and 5.3 months (95% CI 3.8–6.8 months), respectively (p = 0.249; Fig. 2c). Similarly, OSs of groups were 6.5 months (95% CI 4.8–8.3 months) and 14.2 months (95% CI 9.2–19.2 months), respectively (p = 0.014; Fig. 2d). The median PFSs and OSs of the high burden of intrahepatic lesions group and the others with the whole population in our cohort are also demonstrated in online supplementary Figure 1c and d, respectively (PFS, high burden of intrahepatic lesions: 3.9, 95% CI 3.1–4.8 months, others: 5.3, 95% CI 4.3–6.2 months, p = 0.169; OS, high burden of intrahepatic lesions: 6.0, 95% CI 4.9–7.2 months, others: 14.2, 95% CI 9.0–19.4 months, p = 0.002). Lastly, the ORRs of the high burden of intrahepatic lesions group and others were 41 and 41%, respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

PFS and OS in patients with advanced HCC who received lenvatinib. a Comparing PFS in first- and second- or later-line Child-Pugh class A patients (blue line: first line, red line: second or later-line). b Comparing OS in first- and second- or later-line Child-Pugh class A patients (blue line: first line, red line: second or later line). c Comparing PFS in a high burden of intrahepatic lesions and other Child-Pugh class A patients (blue line: high burden of intrahepatic lesions, red line: others). d Comparing OS in a high burden of intrahepatic lesions and other Child-Pugh class A patients (blue line: high burden of intrahepatic lesions, red line: others). e Comparing PFS in Child-Pugh classes A and B patients (blue line: Child-Pugh class A, red line: Child-Pugh class B). f Comparing OS in Child-Pugh classes A and B patients (blue line: Child-Pugh class A, red line: Child-Pugh class B). PFS, progression-free survival.

We compared AE between the presence and absence of both previous systemic therapies (first vs. second or later line) and a high burden of intrahepatic lesions (online suppl. Table 2). No remarkable differences were found in these analyses (Table 3).

Efficacy and Safety of Lenvatinib Focusing on Patients with Poor Liver Function

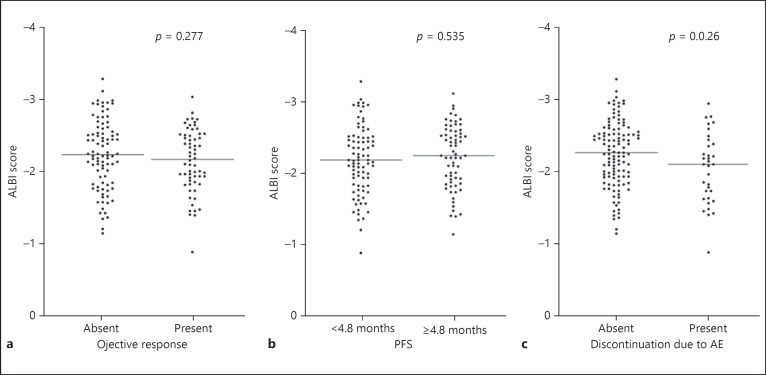

The median PFSs of Child-Pugh classes A and B were 5.1 months (95% CI 4.3–6.0 months) and 4.3 months (95% CI 3.5–5.0 months), respectively (p = 0.795; Fig. 2e). According to Child-Pugh classes of A, and B, ORRs were 39 and 50%, respectively (Table 2). The median OSs of Child-Pugh classes A and B were 13.3 months (95% CI 9.8–16.9 months) and 8.1 months (95% CI 2.0–14.3 months), respectively (p = 0.167; Fig. 2f). Figure 3a indicates a correlation between albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score and objective response. The median scores of ALBI did not significantly differ between patients with the absence and presence of achieving objective response (absent: −2.157, present: −2.241, p = 0.277). Similarly, the median scores of ALBI did not significantly differ between patients with PFS of <4.8 and 4.8 months or more (PFS <4.8 months: −2.186, ≥4.8 months: −2.233; p = 0.535; Fig. 3b). In contrast, the discontinuation rate of lenvatinib due to AE was higher in patients with Child-Pugh scores of 7 points or more when compared with those with Child-Pugh scores of 5 and 6 points (Child-Pugh score 5: 9 patients [13%], score 6: 15 patients [24%], score ≥7: 10 patients [50%]). Similarly, when using ALBI score, patients who discontinued lenvatinib administration due to AE showed significantly worse outcomes (absent: −2.252, present: −2.051; p = 0.026; Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Correlations of ALBI score and objective response (a), PFS (b), and discontinuation due to AE (c) in patients with advanced HCC. PFS, progression-free survival; AE, adverse events; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin.

Table 3 indicates correlations of AE due to lenvatinib and liver function according to Child-Pugh classes. The rates of liver function-related AE due to lenvatinib (e.g., elevated AST, hepatic encephalopathy, and bilirubin elevation) were higher in Child-Pugh class B patients. Online supplementary Figure 2 shows the correlation of the common lenvatinib-related AE and ALBI score. We noted a strong correlation between liver function-related AE due to lenvatinib and ALBI score (online suppl. Fig. 2f, k, l).

Online supplementary Table 2 shows the list of patients who observed hepatic encephalopathy during lenvatinib treatments. Of the 49 patients in whom P-S shunt was detected at the baseline examinations, 16 patients (33%) found hepatic encephalopathy. A multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that P-S shunt at the baseline radiological assessment and a serum NH3 level higher than upper normal limitation at the time of baseline were independent risk factors of hepatic encephalopathy during treatment with lenvatinib (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of the risk factors for hepatic encephalopathy during lenvatinib treatment in patients with advanced HCC

| Variables | Univariate analysis |

p value | Multivariate analysis |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Age, >73 years | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.843 | 0.328–2.169 | 0.724 | |||

| Body weight, <60 kg | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.843 | 0.328–2.169 | 0.724 | |||

| ECOG-PS >1 | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.761 | 0.086–6.003 | 0.761 | |||

| Child-Pugh score | ||||||

| 5 | Reference | |||||

| 6 | 8.160 | 1.748–38.095 | 0.008 | |||

| >6 | 14.571 | 2.661–79.807 | 0.002 | |||

| Baseline NH3 level, >UNL | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Present | 15.000 | 5.127–43.885 | <0.001 | 5.575 | 1.676–18.542 | 0.005 |

| Liver tumor volume, >50% | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.642 | 0.078–5.305 | 0.681 | |||

| MVI | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Presence of MVI without both main portal | 1.962 | 0.570–6.754 | 0.285 | |||

| invasion and bile duct invasion | ||||||

| Main portal invasion and/or | 1.051 | 0.216–5.119 | 0.951 | |||

| bile duct invasion | ||||||

| EHM | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.883 | 0.330–2.362 | 0.804 | |||

| Baseline AFP, >400 ng/mL | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.703 | 0.254–1.947 | 0.498 | |||

| Detection of P-S shunt at the baseline radiological assessment | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Present | 10.568 | 3.273–34.127 | <0.001 | 7.043 | 2.057–24.114 | 0.002 |

| Pretreatment | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 3.195 | 0.404–25.286 | 0.271 | |||

| Starting doses of lenvatinib, 12 mg | ||||||

| Absent | Reference | |||||

| Present | 0.255 | 0.071–0.913 | 0.036 | |||

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; UNL, upper normal limitation; MVI, macrovascular invasion; EHM, extrahepatic metastasis; AFP, alfa-fetoprotein; P-S shunt, portosystemic shunt; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

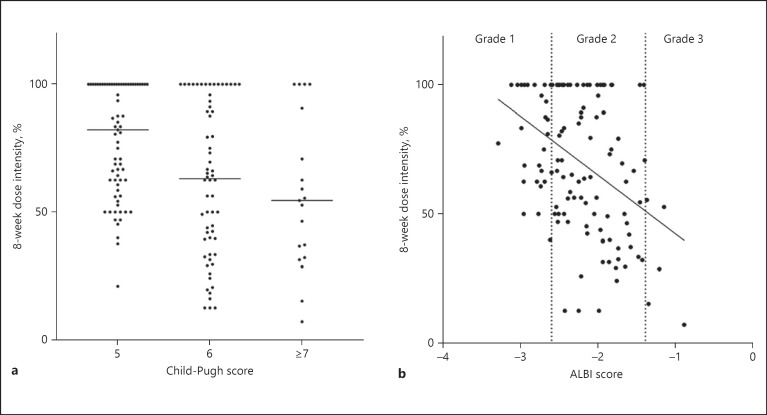

In the present study, 127 patients continued lenvatinib for >8 weeks. We investigated the correlations of 8-week dose intensity of lenvatinib and liver function in this population (Fig. 4). Patients with a Child-Pugh score of 5 points had remarkable higher dose intensity relative to patients with a Child-Pugh score of 6 points or higher (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b indicates correlations between ALBI score and 8-week dose intensity in patients with advanced HCC who received lenvatinib.

Fig. 4.

Correlations of Child-Pugh (a), ALBI scores (b), and 8-week dose intensity of lenvatinib in patients with advanced HCC. ALBI, albumin-bilirubin.

Discussion

The present study confirmed the safety and efficacy of lenvatinib administration in patients with advanced HCC on the basis of Japanese real-world data. Our results demonstrated that lenvatinib has the potential to achieve a broader indication in patients with advanced HCC requiring second- or later-line therapy and having a high burden of intrahepatic lesions. On the contrary, the dose intensity of lenvatinib administration had a strong correlation with liver function according to both the Child-Pugh and ALBI scores. Taken together with the safety profile of lenvatinib in a poor liver function population, we should consider more careful management of lenvatinib in patients with advanced HCC depending on the liver function.

In Japanese field practice, lenvatinib has been administered to patients with advanced HCC with no previous history of systemic therapy or to those who have failed or are refractory to one or more agents [22]. The ORR and PFS of lenvatinib in patients with advanced HCC in our cohort compared favorably with those of the REFLECT trial. We also found that ORR and PFS of the front-line population were nearly equal to those of the second- or later-line population. These results were in concordance with the first report of lenvatinib administration in real-world practice by Hiraoka et al. [22]. Several recent articles have noted that more than half of patients who were administered sorafenib as first-line systemic therapy had the potential of converting to the following agent at the time of sorafenib failure or when they were refractory [23, 24, 25, 26]. To date, 3 molecular target agents (i.e., regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab) have improved OS in placebo-controlled phase III studies in a second- or later-line setting after sorafenib administration in patients with advanced HCC [15, 27, 28]. However, 2 of the 3 phase III trials (RESORCE trial: regorafenib vs. placebo, REACH-2 trial: ramucirumab vs. placebo) included only a limited beneficial population of second-line candidates and patients with advanced HCC (i.e., RESORCE trial included only patients who confirmed progression and had tolerability of sorafenib, while REACH-2 trial included patients with AFP ≥400 mg/mL) [27, 28]. In practice, the candidate rates of regorafenib and ramucirumab appeared to be <50% of patients who received sorafenib [23, 24, 25, 26]. Namely, additional second-line agents after sorafenib administration have still been required. The PFS of the present study in second- or later-line patients stood in comparison with the results of 3 phase III studies of a second-line setting. Taken together, lenvatinib has a strong potential to be a second- or later-line agent after sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC.

We also investigated the efficacy of lenvatinib administration in patients with advanced HCC with a high burden of intrahepatic lesions. In the REFLECT trial, this population was excluded from the study [17]. In the present cohort, the ORR of the high burden of intrahepatic lesions group was almost similar to that of the other study population. Although the PFS and the OS of the high burden of intrahepatic lesions group were shorter than those of others, we considered that patients with advanced HCC with a high burden of intrahepatic lesions should not be excluded from lenvatinib administration. Several studies have already reported that clinical outcomes of sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC with a high burden of intrahepatic lesions such as either macrovascular invasion and/or 50% or higher liver occupation were worse than in the “other” population. We indicated that the OS of lenvatinib administration in this high burden of intrahepatic lesions population withstood comparison with that of sorafenib administration [29, 30, 31]. For the next few decades, the incidence of HCC is expected to dramatically increase, primarily in East and South Asia [32, 33]. In those regions, several cases of HCC are diagnosed at highly advanced stages [33]. Lenvatinib, which has a high expectation rate of ORR, may be a promising agent for use in patients with advanced HCC with a high burden of intrahepatic lesions. Although our study included a less number of patients with advanced HCC with a high burden of intrahepatic lesions, further prospective or large cohort retrospective studies should be required to confirm the safety and efficacy of lenvatinib in this group.

The present study supported the safety of lenvatinib, including among both Child-Pugh classes A and B patients with advanced HCC. The most frequently occurring AE due to lenvatinib administration were hypothyroidism (41%), anorexia (41%), and fatigue (38%), and the occurrence rates of these AE in the present research were higher than those in the REFLECT trial. Our results could not find a relationship between these AE and baseline liver function according to ALBI score (online suppl. Fig. 2). On the contrary, patients who were observed to have liver function-related AE had significantly worse baseline liver function according to their ALBI scores relative to patients who did not have any liver function-related AE. More importantly, we demonstrated that the 8-week dose intensity of lenvatinib administration had a strong correlation with liver function according to both Child-Pugh and ALBI scores. An early-phase clinical trial of lenvatinib showed that the drug was mainly eliminated by hepatic metabolism, while a dose-finding study on lenvatinib for advanced HCC defined different recommended doses between Child-Pugh classes A and B patients [18, 34]. Our results also indicated that the 8-week dose intensity of patients with a Child-Pugh score of 6 points was significantly lower than that of patients with a Child-Pugh score of 5 points. On the basis of these findings, an increase in exposure to lenvatinib in patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment is expected.

Since both the PFS and ORR of Child-Pugh class B patients in our cohort were concordant with that of Child-Pugh class A patients, it may be better to explore the possibility of using lenvatinib in poor liver function populations. Looking back at sorafenib for Child-Pugh class B patients, several reports published since sorafenib was approved have supported the safety and effectiveness of sorafenib in Child-Pugh class B patients [35, 36]. Nowadays, sorafenib is administered to Child-Pugh class B patients in real-world practice. However, our results suggested that Child-Pugh class B patients had high frequency rates of liver-related AE relative to Child-Pugh class A patients. Thus far, lenvatinib was not recommended for Child-Pugh class B patients under the existent circumstances. It is speculated that the doses of lenvatinib should be adjusted more delicately according to liver function. Further investigations for developing a model of adjusting the dose of lenvatinib to liver function are required for using lenvatinib in Child-Pugh class B patients. ALBI score seems to be useful for developing this model since it is a score based on a continuous variable [37].

In conclusion, lenvatinib is expected to be promising and beneficial for patients with advanced HCC requiring second- or later-line therapy and who have a high burden of intrahepatic lesions. On the contrary, we cannot recommend lenvatinib for Child-Pugh class B patients on the basis of the results of the present study. Since lenvatinib may be an unexpectedly sensitive drug affected by liver function, more attentive management of lenvatinib dose modification should be considered. Further research is required for confirming the effectiveness of the expanded indication of lenvatinib and to establish a methodology of safe lenvatinib administration in this patient population with poor liver function.

Statement of Ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent was not required.

Disclosure Statement

S.O. and N.K.: received grant support, advisory fee and honoraria from Eisai. Y.O. received honoraria from Eisai. The other authors who took part in this study indicated that they did not have anything to declare regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this study.

Funding Sources

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

Sadahisa Ogasawara: conceptualization. Sadahisa Ogasawara: methodology. S.M. and Sadahisa Ogasawara: formal analysis. S.M., Sadahisa Ogasawara, Y.O., M.O., M.I., N.I., Y.H., A.S., Shinichiro Okabe, R.A., E.I., Masanori Atsukawa., N.S., Hideaki Mizumoto, Keisuke Koroki, Kengo Kanayama, H.K., Kazufumi Kobayashi, S.K., M.N., Naoya Kanogawa, T.S., Takayuki Kondo., E.S., S.N., A.T., T.C., Makoto Arai. A., Tatsuo. Kanda., and Hitoshi Maruyama.: investigation. S.M.: data curation. S.M.: writing − original draft preparation. Sadahisa Ogasawara and Y.O.: writing − review and editing. Naoya Kato: supervision. Naoya Kato: project administration.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Mar;65((2)):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016 Apr;2((1)):16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kudo M, Izumi N, Sakamoto M, Matsuyama Y, Ichida T, Nakashima O, et al. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan Survival Analysis over 28 Years of 173,378 Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Japan. Liver Cancer. 2016 Jul;5((3)):190–7. doi: 10.1159/000367775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shindoh J, Makuuchi M, Matsuyama Y, Mise Y, Arita J, Sakamoto Y, et al. Complete removal of the tumor-bearing portal territory decreases local tumor recurrence and improves disease-specific survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016 Mar;64((3)):594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiina S, Tateishi R, Arano T, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Apr;107((4)):569–77. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003 Feb;37((2)):429–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. SHARP Investigators Study Group Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul;359((4)):378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Jan;10((1)):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson PJ, Qin S, Park JW, Poon RT, Raoul JL, Philip PA, et al. Brivanib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the randomized phase III BRISK-FL study. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Oct;31((28)):3517–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cainap C, Qin S, Huang WT, Chung IJ, Pan H, Cheng Y, et al. Linifanib versus Sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jan;33((2)):172–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llovet JM, Decaens T, Raoul JL, Boucher E, Kudo M, Chang C, et al. Brivanib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who were intolerant to sorafenib or for whom sorafenib failed: results from the randomized phase III BRISK-PS study. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Oct;31((28)):3509–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu AX, Park JO, Ryoo BY, Yen CJ, Poon R, Pastorelli D, et al. REACH Trial Investigators Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Jul;16((7)):859–70. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu AX, Kudo M, Assenat E, Cattan S, Kang YK, Lim HY, et al. Effect of everolimus on survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after failure of sorafenib: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 Jul;312((1)):57–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudo M, Moriguchi M, Numata K, Hidaka H, Tanaka H, Ikeda M, et al. S-1 versus placebo in patients with sorafenib-refractory advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (S-CUBE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jun;2((6)):407–17. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. RESORCE Investigators Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017 Jan;389((10064)):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda M, Morizane C, Ueno M, Okusaka T, Ishii H, Furuse J. Chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future perspectives. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018 Feb;48((2)):103–14. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018 Mar;391((10126)):1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamai T, Hayato S, Hojo S, Suzuki T, Okusaka T, Ikeda K, et al. Dose Finding of Lenvatinib in Subjects With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Based on Population Pharmacokinetic and Exposure-Response Analyses. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017 Sep;57((9)):1138–47. doi: 10.1002/jcph.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009 Jan;45((2)):228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010 Feb;30((1)):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugawara K, Nakayama N, Mochida S. Acute liver failure in Japan: definition, classification, and prediction of the outcome. J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug;47((8)):849–61. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Atsukawa M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Ishikawa T, et al. Real-life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group, HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics in Japan) Prognostic factor of lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world conditions-Multicenter analysis. Cancer Med. 2019 Jul;8((8)):3719–28. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Suzuki E, Maeda T, Yokoyama M, et al. Characteristics of patients with sorafenib-treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma eligible for second-line treatment. Invest New Drugs. 2018 Apr;36((2)):332–9. doi: 10.1007/s10637-017-0507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terashima T, Yamashita T, Sunagozaka H, Arai K, Kawaguchi K, Kitamura K, et al. Analysis of the liver functional reserve of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing sorafenib treatment: prospects for regorafenib therapy. Hepatol Res. 2018 Nov;48((12)):956–66. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchikawa S, Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Kodama K, Nishida Y, Inagaki Y, et al. Clinical outcomes of sorafenib treatment failure for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and candidates for regorafenib treatment in real-world practice. Hepatol Res. 2018 Sep;48((10)):814–20. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzuya T, Ishigami M, Ito T, Ishizu Y, Honda T, Ishikawa T, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of candidates for second-line therapy, including regorafenib and ramucirumab, for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after sorafenib treatment. Hepatol Res. 2019 Sep;49((9)):1054–65. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13358. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul;379((1)):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, et al. REACH-2 study investigators Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Feb;20((2)):282–96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017 Nov;67((5)):999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda H, Nishikawa H, Osaki Y, Tsuchiya K, Joko K, Ogawa C, et al. Japanese Red Cross Liver Study Group Proposal of Japan Red Cross score for sorafenib therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2015 Oct;45((10)):E130–40. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriguchi M, Aramaki T, Nishiofuku H, Sato R, Asakura K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Sorafenib versus Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy as Initial Treatment for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Advanced Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis. Liver Cancer. 2017 Nov;6((4)):275–86. doi: 10.1159/000473887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr;380((15)):1450–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omata M, Cheng AL, Kokudo N, Kudo M, Lee JM, Jia J, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol Int. 2017 Jul;11((4)):317–70. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubbelman AC, Rosing H, Nijenhuis C, Huitema AD, Mergui-Roelvink M, Gupta A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and excretion of (14)C-lenvatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors or lymphomas. Invest New Drugs. 2015 Feb;33((1)):233–40. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marrero JA, Kudo M, Venook AP, Ye SL, Bronowicki JP, Chen XP, et al. Observational registry of sorafenib use in clinical practice across Child-Pugh subgroups: the GIDEON study. J Hepatol. 2016 Dec;65((6)):1140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Kanogawa N, Saito T, Motoyama T, et al. Sorafenib treatment in Child-Pugh A and B patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: safety, efficacy and prognostic factors. Invest New Drugs. 2015 Jun;33((3)):729–39. doi: 10.1007/s10637-015-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Feb;33((6)):550–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data