Abstract

Introduction

Tandem lesions involving a large vessel occlusion intracranially with concomitant cervical carotid critical stenosis or occlusion are a common presentation of acute ischemic stroke. These lesions are both challenging and time-consuming but can be extremely beneficial for patients when successful. We present a technique utilizing the pusher wire of the stent retriever used for intracranial thrombectomy as the workhorse wire for carotid intervention using a monorail system to perform cervical carotid angioplasty.

Methods

We reviewed four successive patients who presented with a tandem occlusion and underwent thrombectomy and simultaneous carotid artery intervention using this technique.

Results

All four patients had radiographically successful intracranial thrombectomy and cervical carotid revascularization. Time from groin puncture to intracranial stent retriever deployment was 63 min on average. Then, using the pusher wire as a monorail workhorse, time from stent retriever deployment to carotid angioplasty was on average 6 min.

Discussion

This technique allows for cervical carotid revascularization to begin during the recommended 5-min wait time after stent retriever deployment, allowing for rapid near-simultaneous revascularization across both lesions. This technique has been reported briefly in the past for management of a cervical dissection. There is continued debate regarding the management of tandem occlusions, as to which lesion should be managed first.

Conclusion

As the management paradigms of tandem occlusions continue to evolve, this technique may improve outcomes by expediting endovascular intervention. Using the stent retriever wire provides a method of expediting the management of the proximal lesion after addressing the more distal intracranial occlusion first.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, neuroendovascular, occlusion, Solitaire, stent retriever, tandem lesions, thrombectomy

Introduction

Roughly one-sixth of patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke symptoms are found to have high-grade stenosis or occlusion of the cervical internal carotid artery (ICA) in conjunction with an intracranial large vessel occlusion (LVO).1 These tandem or skip occlusions of the ICA do not respond well to recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and are a frequently encountered challenge during acute stroke intervention.2–6 Historically, patients with extracranial ICA stenosis and/or occlusion were excluded from many clinical trials including SWIFT-PRIME, TREVO 2, and EXTEND IA.7–10 Conversely, other trials namely, ESCAPE, MR CLEAN, and REVASCAT, did allow enrolment of patients with concurrent extracranial carotid disease. In these trials, patients with an LVO and concomitant tandem occlusion in the cervical ICA did demonstrate a benefit in subgroup analyses.10–12

Significant debate exists as to the best way to manage patients with this radiographic presentation, which often carries a poor prognosis, and for which there are no standardized recommendations for the order of treatment.4,13,14 Many feel that the intracranial occlusion should be treated first while others feel it is easier to treat the cervical occlusion before proceeding intracranially. Maus et al.15 recently published an article which demonstrated that patients treated retrograde, e.g. thrombectomy followed by carotid artery stenting (CAS), had a higher favorable clinical outcome.

Neuroendovascular technique

We have started to use what we believe to be a contemporary technique for carotid angioplasty during stent retriever thrombectomy, described in recent literature by our colleagues internationally as well.16 In brief, we deploy the stent retriever in the usual fashion across the occluded intracranial segment. We then pull the microcatheter off the back of the microcatheter during the 5-min deployment period and use the pusher wire was a workhorse wire to perform a cervical ICA angioplasty to simultaneously revascularize both lesions. While certainly simple in theory, there are some technical nuances in using a stent retriever as a workhorse wire that warrant discussion.

Selection of the common carotid artery with either a 6 French or larger balloon guide catheter or guide sheath is performed using a coaxially loaded selection catheter over a 0.035″ guide wire.

The cervical and ICA occlusions is crossed using an 0.021″ or larger microcatheter and a microwire. Of note, an intermediate catheter—often an aspiration catheter—is helpful in case the balloon guide catheter or guide sheath will not pass.

Next, the occluded intracranial branch is selected with the same system, confirmed by microcatheter digital subtraction angiography run.

A stent retriever is deployed across the occluded segment of the intracranial LVO.

Using the deployed stent retriever as an anchor, we feel comfortable removing the microcatheter with temporary loss of proximal wire control as described in previous reports.17 From here, the stent-retriever pusher wire was used as a monorail to perform carotid interventions.

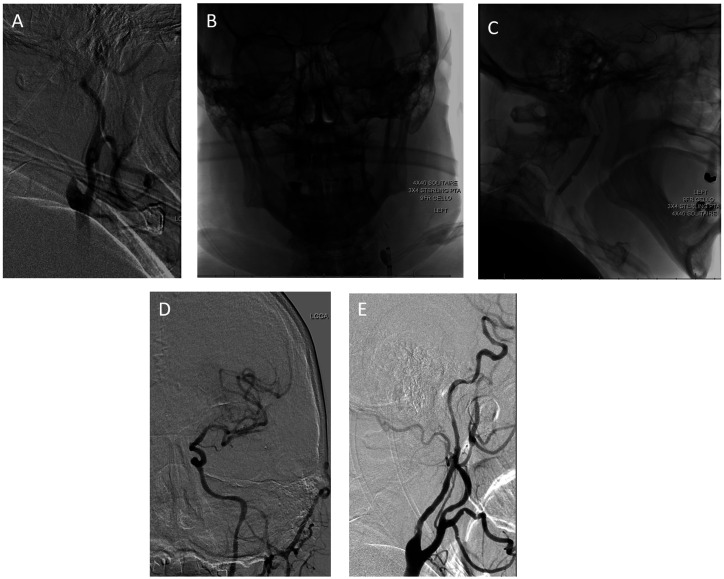

Here, we evaluate for reperfusion after deployment of the stent retriever through the aspiration catheter in the cervical carotid. If required, angioplasty of the cervical carotid artery is done using a monorail balloon that could go over the stent-retriever pusher wire. The balloon inflated is to its nominal pressure and subsequently deflated with careful attention to the location of the “waist” within the balloon (Figure 1).

The intracranial thrombectomy is then performed by removing the stent retriever under balloon occlusion or with the assistance of a suction catheter using the SAVE technique. Advancing the guide catheter or intermediate catheter across the high-grade stenosis is possible during balloon deflation of the cervical carotid stenosis. This allows for the intracranial intervention to proceed in the usual manner for mechanical thrombectomy.

In cases where there is high-grade residual stenosis (>90%), a distal protection device is deployed and completion of the cervical carotid stenting and angioplasty is performed in the usual fashion.

Figure 1.

(a) Lateral view of the left cervical carotid artery demonstrating occlusion at the proximal origin of the internal carotid artery; (b and c) single-frame AP and lateral shots, which demonstrate a solitaire stent retriever deployed in the M1 segment with a Sterling balloon inflated across the cervical carotid occlusion. The cello guide catheter is also inflated during inflation of the cervical balloon to provide some proximal embolic protection; (d) final AP cranial view from the left common carotid artery which demonstrates complete recanalization of the MCA candelabra; (e) final lateral cervical view, which demonstrates recanalization of the origin of the internal carotid artery.

Online supplementary Appendix A discusses the nuances of which catheters our center has employed for the purposes of this technique.

Methods

Consecutive patients from July 2018 to December 2018 with stroke symptoms due to tandem extracranial-intracranial lesions treated in one simultaneous emergent intervention were retrospectively reviewed in a prospectively maintained database. Patients were evaluated by the Neuroendovascular and Neurology teams on presentation. Baseline information including modified Rankin scale (mRS) and National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) were recorded at admission and discharge. All patients underwent expedited radiographic evaluation with computed tomography (CT) head, CT angiography and CT perfusion imaging. RAPID software was utilized in evaluating perfusion scans. Intravenous tPA was given if patient met traditional treatment criteria.

Other data collected include baseline medical history, history of anticoagulation or antiplatelet use, time to groin puncture, time to stent retriever deployment intracranially, time from stent retriever deployment to completion of carotid intervention, final modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (mTICI) score, and complications.

For comparison purposes, patients who presented with similar tandem lesions from January 2014 to December 2018 were reviewed who underwent revascularization without the use of this technique. Time from intracranial revascularization to completion of carotid intervention was calculated in a similar way.

Results

A total of four patients underwent the combined recanalization approach by three different operators, all of whom are neuroendovascular-trained neurosurgeons. All were managed at a Comprehensive Stroke Center, using the aforementioned technique. All four patients were male, ages 57, 62, 68, and 89. The patients commonly had at least two medical comorbidities associate with ischemic stroke including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and diabetes.

NIHSS on admission were 3, 18, 7, and 17, with pre-stroke mRS of 0, 0, 0, and 2 respectively (Table 1). Intravenous tPA was given in one patient. Time from groin puncture to intracranial stent retriever deployment across the LVO was on average 63 min, and from stent retriever deployment to completion of carotid intervention using the pusher wire as the workhorse wire was an average of only 6 min. Two patients required a cervical carotid stent for continued high-grade (>90%) stenosis, while the remaining two patients were treated with angioplasty alone. The cause of proximal occlusion was due to atherosclerotic disease in three patients, and for occlusion after a carotid endarterectomy in the fourth.

Table 1.

Patients who have undergone simultaneous revascularization of tandem lesions using the described technique.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57 | 62 | 68 | 89 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Pre-hospital mRS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Admission NIHSS | 3 | 18 | 7 | 17 |

| tPA given | No | No | Yes | No |

| Groin puncture to stent retriever | 26 min | 58 min | 62 min | 105 min |

| Stent retriever to carotid angioplasty | 6 min | 9 min | 6 min | 2 min |

| TICI score | 3 | 2b | 2b | 3 |

| Carotid stent | None | Wallstent | XACT | None |

| Complications | None | Hemorrhagic conversion | Hemorrhagic conversion | Death |

| Discharge mRS | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Post-rehab mRS | 0 | 1 | 1 | – |

mTICI: thrombolysis in cerebral infarction; mRS: modified Rankin scale; NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; tPA: tissue plasminogen activator.

Regarding complications, one patient suffered a minor reperfusion hemorrhage that was asymptomatic, with an improvement in his NIHSS post-procedure. Symptomatic reperfusion hemorrhage was seen in the patient with an NIHSS of 18 at presentation, with improvement prior to discharge to rehab. Of note post-thrombectomy systolic blood pressures were maintained below 140 mm Hg. One patient, aged 89 who was last seen normal roughly 10 h prior to neuroendovascular intervention, was placed on hospice due to the extent of neurological impairment he suffered from the core infarct and subsequent cardiopulmonary complications, despite the preservation of the penumbra seen on RAPID perfusion imaging. The other three patients were discharged to rehab, with mRS 1, 3, and 3 on discharge. Patients were seen in six-week follow-up, with mRS 0, 1, and 1 after discharge from rehab.

For comparison purposes, six patients were identified between January 2014 and December 2018 who underwent revascularization of similar tandem lesions, without the use of this technique. All six patients were revascularized in retrograde fashion (intracranial LVO first, then carotid intervention). The average time from intracranial revascularization to completion of carotid intervention was found to be 52 min (p-value 0.0077 with a 95% confidence interval).

Discussion

We have presented a technique using the pusher wire from a stent retriever deployed intracranially as a workhorse wire to perform a simultaneous carotid angioplasty. In patients who require cervical carotid revascularization at the time of thrombectomy, this technique helps to quickly address the intracranial occlusion, maintain true lumen access throughout the procedure, and rapidly revascularize the cervical carotid lesion. In practice, this technique can essentially be used to angioplasty the cervical carotid artery during the 5-min recommended wait time after stent retriever deployment. Although the concept is fairly straightforward, there are some technical factors to consider as noted in online supplementary Appendix A.

While one patient suffered a mortality, the remaining three patients had a significant neurological improvement and minimal, if any, long-term deficit. Of note, despite tight blood pressure control, reperfusion hemorrhages were seen in two of the patients, further alluding to the risks associated with post-thrombectomy care. While these difficulties reflect the continued challenge of treating tandem occlusions, the speed of angiographic reperfusion (average 63 min) is comparable to previous studies. The benefit appears to be the speed of carotid intervention when using the Solitaire wire as the scaffold, averaging 6 minutes with this technique.

Using the stent retriever wire as a monorail device has been reported in the literature previously initially for a different pathology. In 2017, Behme et al.18 reported a treatment using the 0.014″ pusher wire of a pRESET device (Phenox; Bochum, Germany) to stent the ICA during an intracranial thrombectomy in the setting of dissection. Further investigation confirmed this technique with a series of patients at three German centers with similar success.16 We have used a similar technique for carotid artery angioplasty using devices currently available for use in the United States (online supplementary Appendix A). We report the speed of revascularization—which was found to be much faster than with our traditional method of retrograde intervention—and hope that our patient cohort will help confirm this as a viable technique for this difficult pathology.

Maus et al.15 recently published their experience with patients who had greater than 70% stenosis of the ipsilateral carotid and an associated LVO. They found that proceeding with the intracranial mechanical thrombectomy first followed by treatment of the cervical carotid led to higher recanalization rates as well as a trend towards improved clinical outcomes, as measured by an mRS ≤ 2 in 44% versus 30%.

Some argue that the benefits of restoring intracranial flow—and therefore collateral circulation—favor the anterograde approach.19–22 The argument to treat the extracranial disease first (anterograde revascularization) further stems from the belief that the technical component of the mechanical thrombectomy would be made easier if the guide catheter could be advanced through the extracranial disease component (e.g. following an angioplasty and/or stent), allowing for better visualization of the intracranial vessels.23 There are also case reports of distal LVOs recanalizing following carotid stenting alone.19 Of note, practitioners utilizing the anterograde approach must be cautious as cases of stent retrievers catching on the cervical ICA stent are reported.24

Conversely, the argument in favor of treating the LVO first is focused on the time-saving that occurs when the focus is turned to the intracranial circulation.15,25 In the study by Maus et al.,15 the time from groin puncture to reperfusion was improved by treating the lesions retrogradely. Our time from groin puncture to intracranial stent retriever deployment was similar, and using the Solitaire pusher wire as the workhorse wire we were able to complete the carotid artery interventions quickly. Thus, by utilizing the Solitaire as both the stent retriever for thrombectomy and as the monorail wire for carotid intervention, the extra- and intracranial lesions can be treated quickly. Given the push to improve time to reperfusion and streamline the treatment process for acute ischemic events, this technique may be a favorable option for tandem occlusions.26

Conclusions

This technical description is designed to highlight a contemporary, expedited method of treating symptomatic tandem intracranial and carotid occlusions, utilizing the stent retriever wire as the workhorse wire. Whether or not treating intracranial LVOs with associated cervical lesions is best managed via an anterograde versus retrograde approach requires further investigation, nevertheless using this method may help accelerate treatment and hopefully improve patient outcomes for this dangerous presentation. Further investigation into outcomes with a larger number of patients is required to better assess this technique, possibly in the form of a randomized control trial comparing anterograde versus retrograde treatment of extra- and intra-cranial lesions causing acute cerebral ischemia.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, INE885253 Supplemetal Material for Simultaneous revascularization of the occluded internal carotid artery using the Solitaire as a workhorse wire during acute ischemic stroke intervention by Alexandra R Paul, Pouya Entezami, Emad Nourollahzadeh, John Dalfino and Alan S Boulos in Interventional Neuroradiology

Authors’ contribution

All authors were involved in the care of these patients. All authors contributed to the writing and review of this article. AP finalized imaging and PE coordinated between authors and managed formatting of the article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Zoppo GJ, Poeck K, Pessin MS, et al. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute thrombotic and embolic stroke. Ann Neurol 1992; 32: 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mpotsaris A, Kabbasch C, Borggrefe J, et al. Stenting of the cervical internal carotid artery in acute stroke management: the Karolinska experience. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahed R, Redjem H, Blanc R, et al. Endovascular management of acute ischemic strokes with tandem occlusions. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016; 41: 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akpinar CK, Gurkas E, Aytac E. Carotid angioplasty-assisted mechanical thrombectomy without urgent stenting may be a better option in acute tandem occlusions. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puri AS, Kuhn AL, Kwon HJ, et al. Endovascular treatment of tandem vascular occlusions in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Churilov L, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for ischemic stroke increases disability-free survival, quality of life, and life expectancy and reduces cost. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nogueira RG, Lutsep HL, Gupta R, et al. Trevo versus Merci retrievers for thrombectomy revascularisation of large vessel occlusions in acute ischaemic stroke (TREVO 2): a randomised trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Solitaire with the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke (SWIFT PRIME) trial: protocol for a randomized, controlled, multicenter study comparing the Solitaire revascularization device with IV tPA with IV tPA alone in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigoryan M, Haussen DC, Hassan AE, et al. Endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke due to tandem occlusions: large multicenter series and systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016; 41: 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assis Z, Menon BK, Goyal M, et al. Acute ischemic stroke with tandem lesions: technical endovascular management and clinical outcomes from the ESCAPE trial. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkhemer OA, Borst J, Kappelhof M, et al. Extracranial carotid disease and effect of intra-arterial treatment in patients with proximal anterior circulation stroke in MR CLEAN. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166: 867–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson MP, Murad MH, Krings T, et al. Management of tandem occlusions in acute ischemic stroke - intracranial versus extracranial first and extracranial stenting versus angioplasty alone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rangel-Castilla L, Rajah GB, Shakir HJ, et al. Management of acute ischemic stroke due to tandem occlusion: should endovascular recanalization of the extracranial or intracranial occlusive lesion be done first? Neurosurg Focus 2017; 42: E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maus V, Borggrefe J, Behme D, et al. Order of treatment matters in ischemic stroke: mechanical thrombectomy first, then carotid artery stenting for tandem lesions of the anterior circulation. Cerebrovasc Dis 2018; 46: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maus V, Behme D, Maurer C, et al. The ReWiSed CARe technique : simultaneous treatment of atherosclerotic tandem occlusions in acute ischemic stroke. Clin Neuroradiol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Maus V, Henkel S, Riabikin A, et al. The SAVE technique: large-scale experience for treatment of intracranial large vessel occlusions. Clin Neuroradiol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Behme D, Knauth M, Psychogios MN. Retriever wire supported carotid artery revascularization (ReWiSed CARe) in acute ischemic stroke with underlying tandem occlusion caused by an internal carotid artery dissection: technical note. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 289–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiotta AM, Lena J, Vargas J, et al. Proximal to distal approach in the treatment of tandem occlusions causing an acute stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papanagiotou P, Roth C, Walter S, et al. Carotid artery stenting in acute stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 2363–2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik AM, Vora NA, Lin R, et al. Endovascular treatment of tandem extracranial/intracranial anterior circulation occlusions: preliminary single-center experience. Stroke 2011; 42: 1653–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao F, Joyce, Lo W, et al. Combined use of stent angioplasty and mechanical thrombectomy for acute tandem internal carotid and middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuroradiol J 2015; 28: 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubiera M, Ribo M, Delgado-Mederos R, et al. Tandem internal carotid artery/middle cerebral artery occlusion: an independent predictor of poor outcome after systemic thrombolysis. Stroke 2006; 37: 2301–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rho HW, Yoon WK, Kim JH, et al. How to escape stentriever wedging in an open-cell carotid stent during mechanical thrombectomy for tandem cervical internal carotid artery and middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2017; 19: 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behme D, Knauth M, Psychogios MN. Retriever first embolectomy (ReFirE): an alternative approach for challenging cervical access. Interv Neuroradiol 2017; 23: 412–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schregel K, Behme D, Tsogkas I, et al. Optimized management of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. J Vis Exp 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, INE885253 Supplemetal Material for Simultaneous revascularization of the occluded internal carotid artery using the Solitaire as a workhorse wire during acute ischemic stroke intervention by Alexandra R Paul, Pouya Entezami, Emad Nourollahzadeh, John Dalfino and Alan S Boulos in Interventional Neuroradiology