Abstract

Intracranial high-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging is an imaging paradigm that complements conventional imaging modalities used in the evaluation of neurovascular pathology. This review focuses on the emerging utility of vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging in the characterization of intracranial aneurysms. We first discuss the technical principles of vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging highlighting methods to determine aneurysm wall enhancement and how to avoid common interpretive pitfalls. We then review its clinical application in the characterization of ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms, in particular, the emergence of aneurysm wall enhancement as a biomarker of aneurysm instability. We offer our perspective from a high-volume neurovascular center where vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging is in routine clinical use.

Keywords: Intracranial aneurysm, magnetic resonance imaging, vessel wall imaging

Introduction

Intracranial saccular aneurysms have a high prevalence (3–4%) and their rupture is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.1 However, the incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is low (3–50 per 100,000 population per year)2,3 suggesting that a majority of unruptured aneurysms remains asymptomatic. Risk factors for aneurysmal rupture have been identified including aneurysm-specific (size, location, and morphology) and patient-specific (age, race, history of prior aneurysmal SAH, and hypertension) factors. Some of these are included in predictive models of rupture, e.g. PHASES score.4 However, their clinical application is not widespread. This likely represents concern that while a majority of unruptured aneurysms are small (and have the lowest predicted risk of rupture),5 a majority of ruptured aneurysms are also small. This observation is referred to as the “aneurysm paradox” and highlights the need for a biomarker of aneurysm instability, especially in the evaluation of prevalent, small, unruptured aneurysms. The scope of this problem is exacerbated by the increased rate of incidental aneurysm detection due to the widespread availability of non-invasive, neurovascular imaging.6

Conventional imaging techniques for evaluating intracranial arteries include computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), digital subtraction angiography, and Doppler ultrasonography (DUS). With the exception of DUS, these imaging tools can be considered “lumenography” and focus the clinician’s attention on the inside of the blood vessel. In contrast, DUS is a vessel wall imaging modality, but is limited in its exploration of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and high operator dependence.7,8 High-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging (VW-MRI) is different and valuable because it allows an operator-independent evaluation of the intracranial vessel wall. This technique provides a unique and complementary perspective on neurovascular pathologies including aneurysms.

VW-MRI: Principles, limitations, avoidance of pitfalls, and methods for determining aneurysm wall enhancement (AWE)

In this section we discuss the theoretical and technical principles behind VW-MRI for the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms. For a more detailed description of sequence parameters, excellent and highly technical reviews are available in the published literature.7,8

Theoretical principles for studying VW-MRI AWE

Multiple lines of evidence suggested that AWE on VW-MRI may represent a biomarker of aneurysm instability.

The evaluation of human aneurysm tissue collected at the time of surgical clipping demonstrated a higher degree of inflammatory cell infiltrates in ruptured compared to unruptured aneurysms.9,10

In a post-hoc analysis of the ISUIA natural history study of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, habitual aspirin use was associated with a reduced likelihood of aneurysmal SAH.11 Similarly, in the more recent UCAS natural history study, the presence of a daughter sac was a strong predictor of future hemorrhage.12 Aneurysm dysmorphism is likely correlated with the severity of underlying vessel wall disease.

Advanced MR imaging techniques, e.g. ferumoxytol-enhanced MRI (to assess macrophage uptake in the aneurysm wall)13 and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (to assess aneurysm wall permeability), associated an inflammatory phenotype with aneurysm instability.14

Prior evaluation of inflammatory vasculopathies, specifically, cerebral vasculitis15–17 and symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis,15,18,19 demonstrated avid wall enhancement on VW-MRI.

These observations set the stage for an exploration of the utility of AWE on VW-MRI in the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms.

Technical principles and limitations

Conceptually, the vessel (and aneurysm) wall is a thin structure sandwiched between blood inside the vessel and CSF outside the vessel; all three of these components (blood, vessel wall, and CSF) produce signal on MRI sequences, but have different properties. If the signal from the blood and the CSF can be suppressed sufficiently, the remaining signal belongs to the vessel wall. If then imaged with small enough voxels in this manner, the vessel wall can be visualized. The result is so-called black-blood imaging with a focus on the vessel wall, not its lumen. Properties of the vessel wall can then be assessed by repeating this imaging after the administration of contrast resulting in “vessel wall enhancement.”

Technically, VW-MRI requires both high contrast resolution (the ability to distinguish differences in signal intensity from two structures) and high spatial resolution (the ability to distinguish between two adjacent structures) to visualize the very small intracranial vessel wall.7,8 High contrast resolution is achieved by suppressing the signal from intraluminal arterial blood and extraluminal CSF. The black-blood sequences take advantage of inherent differences in the magnetic relaxation properties and the flowing nature of blood and CSF to suppress their signal leaving only the signal of the vessel wall itself. However, slowed or turbulent flow can hamper proper suppression creating artifactual signal which may be misinterpreted. Slow flow can occur in the periphery of even normal arterial vessels due to the normal parabolic velocity profile of its laminar flow. Turbulent flow can often occur within aneurysms due to their complex morphology. Veins also have slow flow and do not suppress well. These suppression artifacts are visible on pre-contrast acquisitions and can be even more pronounced on post-contrast sequences. Free induction decay artifact due to the repeated refocusing radiofrequency pulses within the short echo time of the acquisition can also impair visualization of the vessel wall especially in cases of mild wall enhancement. It appears as a dashed, “zigzag” pattern on the image. In its current implementation, the smallest in-plane spatial resolution of VW-MRI sequences is 0.4 × 0.4 mm2; unfortunately this is greater than the thickness of the vessel wall itself (e.g. histopathological studies show that the wall thickness of a normal proximal vessel of the circle of Willis, e.g. proximal MCA or basilar trunk, is 0.2–0.3 mm20). Because at least two voxels are needed within an object to measure its size, then the thickness of the normal intracranial vessel wall cannot be reliably measured.7 Because of this, a single voxel will contain vessel wall in addition to intraluminal blood and or extraluminal CSF. This makes suppression of those signals even more important. Other surrounding structures (i.e. brain parenchyma, dura, etc.) can also be contained within a single voxel. In this manner, the vessel wall on non-contrast images may blend in at points adjacent to parenchyma or lack the signal strength to be readily visualized. In these cases, post-contrast images may increase contrast resolution and improve visualization of the vessel wall.

In practice, a high-resolution VW-MRI with a field strength of 3 T or higher is necessary to achieve both high contrast and high spatial resolution within a reasonable acquisition time.7,8,21 The protocol generally includes a T1-weighted sequence before and after contrast administration to detect spontaneously hyper-intense blood products and wall enhancement, respectively. The 2D acquisitions (using at least two orthogonal acquisitions in both the long and short axis of the vessel) offer the best image quality, but focus on a small region of interest. The 3D acquisitions can be reformatted in any plane and allow for whole brain coverage, thus providing greater flexibility.8 Finally, the interpretation of VW-MRI is facilitated by inclusion of a conventional MRA (either 3D time-of-flight or contrast-enhanced).7

Interpretation of AWE—Avoidance of pitfalls

A number of pitfalls can frustrate interpretation of AWE, even amongst experienced readers. The most common pitfalls are categorized below (Figures 1 and 2).

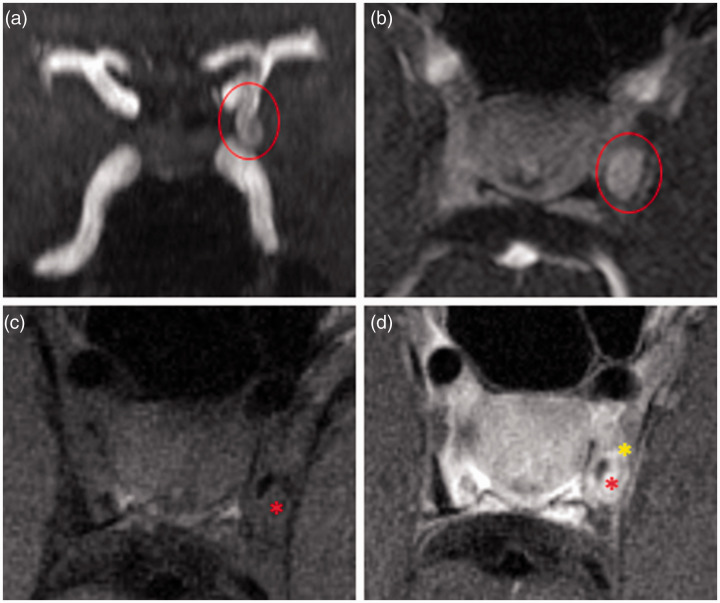

Figure 1.

Pitfalls of vessel wall interpretation. (a) 3D TOF-MRA with left PCOM aneurysm (circle); (b) axial contrast-enhanced 3D MRA showing complete filling of the aneurysm showing the extent of the true lumen; (c) axial pre-contrast VW-MRI showing incomplete intraluminal suppression likely due to slow or turbulent flow asterisk, compared to (b); and (d) axial post-contrast VW-MRI with intraluminal enhancement due to incomplete suppression of blood signal (red asterisk) and normal enhancement of the surrounding cavernous dura which complicates interpretation (yellow asterisk).

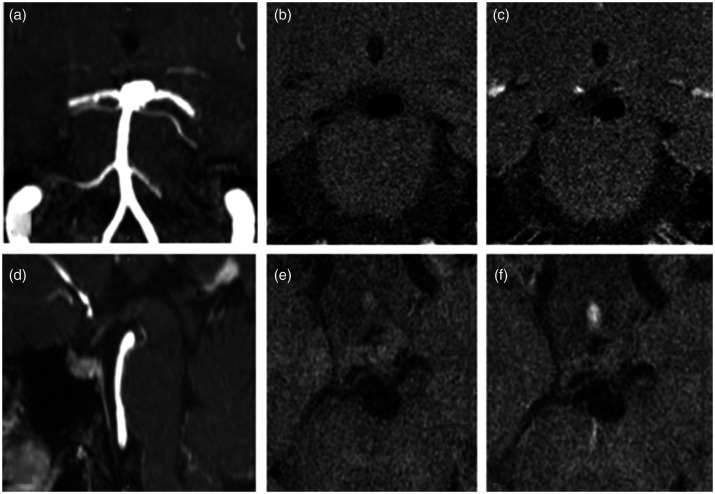

Figure 2.

Enhancement from adjacent veins. An incidental basilar aneurysm underwent VW-MRI. (a) and (d) Coronal and sagittal MRA MIP showing basilar tip aneurysm, (b) and (c) coronal VW-MRI images pre- and post-contrast demonstrate a focal area of “enhancement”, (e) and (f) adjacent axial VW-MRI sequences more clearly demonstrating the linear nature of this enhancing structure adjacent to the aneurysm (a vein).

Proximity to dura or adjacent veins. The dura normally enhances avidly after contrast administration and can significantly obscure the assessment of AWE. This is further complicated by a tendency of normal vascular structures to enhance as they cross the dura, a phenomenon most often ascribed to vasa vasorum.22 Great care must therefore be taken when assessing AWE of cavernous and transitional aneurysms. Similarly, venous structures typically demonstrate avid enhancement. An adjacent vein can easily result in misinterpretation of AWE. This pitfall is best avoided by identifying the linear morphology of veins on VW-MRI in multiples planes.8

Intraluminal enhancement due to insufficient suppression of blood. As discussed above, current implementations of intracranial VW-MRI are very dependent on high contrast resolution achieved using blood suppression techniques. Insufficient suppression of blood, typically due to intra-aneurysmal “slow flow,” will result in luminal enhancement precluding a reliable determination of AWE.

Tangential planes through the aneurysm sac. The importance of making determinations of AWE based on orthogonal views through the aneurysm sac cannot be overstated. Tangential planes can result in an overestimation of AWE. This is true whether considering 2D or 3D acquisitions.

Recognizing dissecting and thrombosed aneurysms. Wall enhancement has been associated with structural pathological vessel alterations such as dissection and macroscopic intraluminal thrombus.23,24 Conventional luminal imaging modalities and pre-contrast high-resolution VW-MRI show distinct morphological and signal anomalies which allow discrimination of an enhancing dissecting aneurysm or partially thrombosed aneurysm from enhancing, saccular, non-thrombosed aneurysms. Specifically, dissecting aneurysms form in non-branch locations and are defined by the presence of an intimal flap or an intramural hemorrhage resulting in a crescent shaped region of spontaneous high T1 signal.25 Thrombosed saccular aneurysms instead present an eccentric filling defect on post-contrast luminal imaging modalities corresponding to a T1 iso- or hyper-intense structure on the pre-contrast VW-MRI. This distinction is important as the underlying pathogenesis is not the same and the wall enhancement in these groups may have different histological correlates and clinical implications.

Pseudo-enhancement. An important point regarding AWE deserves special mention; specifically, the concept of pseudo-enhancement. Larger aneurysms demonstrate slow flow around their perimeter. This can result in incomplete suppression of blood along the aneurysm wall resulting in pseudo-enhancement. However, it must be recognized that this type of enhancement is not distinguishable from “true” enhancement of the aneurysm wall in current implementations of intracranial VW-MRI.26,27 Because nearly all intracranial aneurysm VW-MRI studies have not distinguished between pseudo- and true enhancement, the conclusions of these studies are related to “total” enhancement, or to observed AWE. In this review, as in most clinical papers to date, AWE refers to the observed enhancement on conventional VW-MRI. To what degree the enhancement is due to “true” enhancement versus pseudo-enhancement is not known.

Qualitative and quantitative methods for determining AWE

There is large variability in the methodology used to assess AWE. Qualitative and quantitative methods have been described. The first studies simply established the absence versus presence of AWE. Subsequent studies further characterized the enhancement with different classification systems (faint/strong, focal/circumferential, thin/thick enhancement).28–32 For example, Edjlali et al.32 used a grading system distinguishing between focal enhancement, thin circumferential enhancement, and thick circumferential enhancement, and showed that the thick circumferential pattern demonstrated the highest specificity for differentiating between stable and unstable aneurysms (Figure 3).

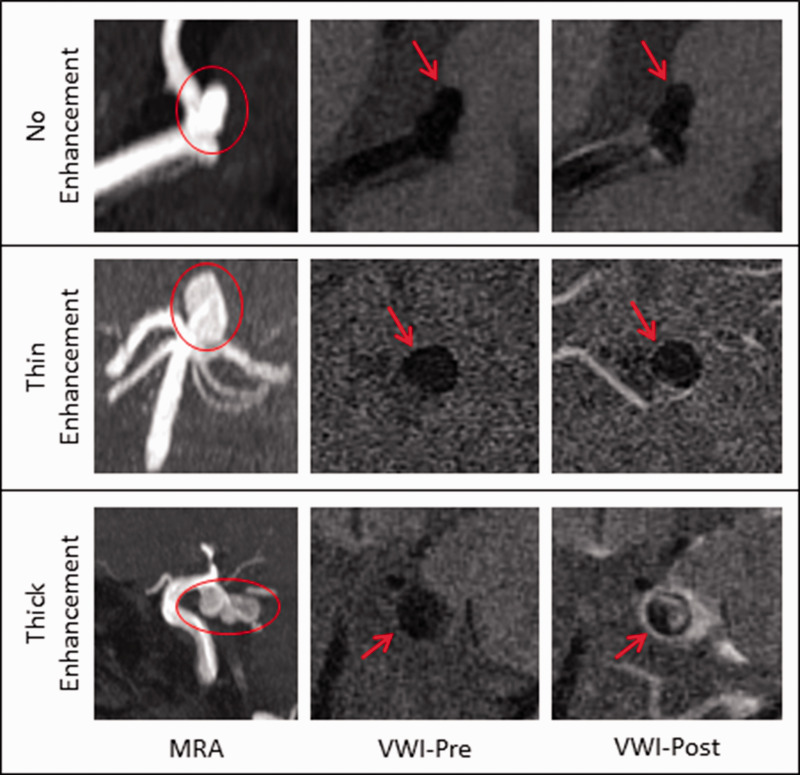

Figure 3.

Qualitative grading of vessel wall enhancement. Upper panel: MCA aneurysm with no enhancement. Middle panel: Basilar aneurysm with thin enhancement. Lower panel: PCOM aneurysm with thick enhancement. MIP 3D TOF MRA (first column), pre-contrast (second column), and post-contrast T1-weighted HR-MRA (third column). Aneurysm is denoted by circle or arrow. MRA: magnetic resonance angiography; VWI: vessel wall imaging.

AWE can also be assessed quantitatively. One metric is the wall enhancement index which is a standardized measure of the change in signal intensity of the aneurysm wall between pre- and the post-contrast T1 images. Another quantitative metric is the contrast ratio of the aneurysm wall to the pituitary stalk, which only requires a post-contrast T1 sequence to calculate.33 To date no study has performed a comparison between qualitative or quantitative assessments of AWE with regard to reproducibility and diagnostic accuracy as a marker of aneurysm instability (Figure 4).

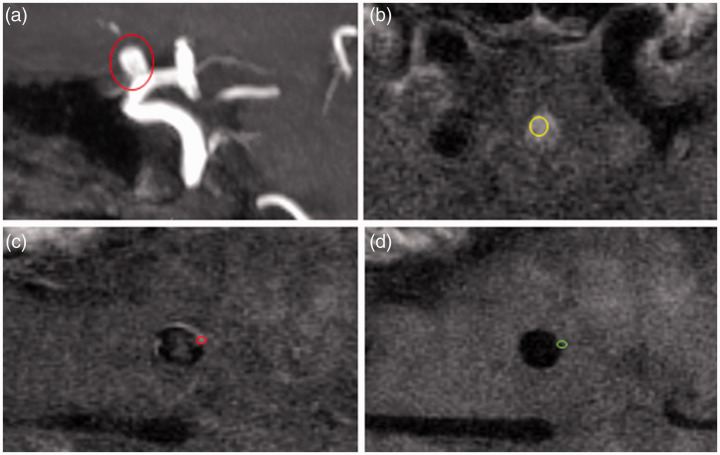

Figure 4.

Quantitative grading of vessel wall enhancement. (a) MIP 3D TOF MRA with right ophthalmic aneurysm (circle), (b) axial VW-MRI post-contrast T1 slice through the pituitary stalk with ROI (yellow circle), (c) axial VW-MRI post-contrast T1 slice through the body of the aneurysm with ROI on the aneurysm wall, and (d) corresponding axial VW-MRI pre-contrast T1 slice with matching ROI (green circle). Conceptually, the signal intensity of the wall is calculated by measuring the brightest part of the aneurysm wall on post-contrast sequences and subtracting the correlating measure from the wall on pre-contrast sequences. Normalization occurs by dividing this number by the highest intensity of the wall on pre-contrast images. Additional metrics can be derived by using brain parenchyma (not shown) or the pituitary stalk as additional normalizing factors.

Histopathologic correlates of AWE

Examination of post-mortem or surgical specimens of tissue imaged with VW-MRI provides insight into its uses and limitations. Most of these specimens are obtained at the time of surgical clipping and resection of the aneurysm dome. These specimens undergo some degree of manipulation prior to fixing, and only a part of the aneurysm can be removed (the neck and normal vessel cannot be obtained).

Histopathological examination confirms that clinical VW-MRI does not yet have enough spatial resolution to measure vessel wall thickness. Measurements of post-mortem specimens of the circle of Willis imaged with clinical VW-MRI acquisitions showed that wall thickness measurements are neither accurate nor precise for walls thinner than 1.0 mm.34

The vast majority of ruptured aneurysms show wall enhancement on imaging. This enhancement is hypothesized to result from inflammation within the wall preceding and leading to the rupture, from a hemostatic thrombus at the rupture site, or from physical leakage of contrast medium from the aneurysm lumen secondary to endothelial disruption. Histological evidence favors the first two mechanisms, though a contribution from the latter cannot be excluded. Hu et al.30 found significant lymphocyte and phagocyte invasion in the wall of a ruptured middle cerebral aneurysm. Matsushige et al.35 analyzed three ruptured aneurysms with focal enhancement and one ruptured aneurysm with circumferential enhancement. Interestingly, circumferential wall enhancement was associated with wall thickening, neovascularization, and inflammatory infiltration while focal wall enhancement correlated with a fresh intraluminal thrombus at the rupture site in aneurysms with otherwise thin walls.

Unruptured aneurysms dichotomize into those with and those without wall enhancement. Amongst those with wall enhancement, there are varying degrees of enhancement. Larsen et al.36 showed that a variable degree of granulocyte infiltration, neovascularization, and vasa vasorum were exclusively present in the five aneurysms with strong wall enhancement out of a sample of 13 unruptured aneurysms. The other eight aneurysms with no or faint enhancement did not show histological signs of inflammation. Similarly, Shimonaga et al.37 and Hudson et al.38 analyzing 9 and 10 unruptured aneurysms, respectively, found an association between AWE on VW-MRI and thickening and atherosclerosis of the aneurysm wall, macrophage infiltration, neovascularization, and deficiency in elastin. Quan et al.39 analyzed nine unruptured aneurysms after clipping and made a further distinction between uniform and focal AWE: they observed that while both enhancement patterns are associated with the same histological markers of wall inflammation, the latter indicate more the presence of an atherosclerotic plaque within the aneurysm.

Overall these histological findings support the hypothesis that contrast-enhanced VW-MRI might be able to directly image the inflammatory and degenerative changes which play a fundamental role in aneurysm progression and eventual rupture. However, it must be noted that some ruptured aneurysms actually have a thin hypocellular wall with no inflammatory cells, showing a phenotype that is at the opposite end of the spectrum compared with inflammatory, thick-walled, atherosclerotic aneurysms.10,40,41 To account for this phenotypical difference, it has been hypothesized that aneurysm growth can result from two biologic mechanisms related to different hemodynamic conditions. The first is associated with a slow recirculation of blood and a low wall shear stress that triggers an inflammatory cell-mediated remodeling and causes a thickening of the aneurysm wall. The other is associated with an impinging flow pattern and a high wall shear stress triggering a mural cell mediated remodeling and causing a thinning of the aneurysm wall.42 Wall enhancement on VW-MRI may predict aneurysm instability due to the first mechanism. It can be speculated that aneurysm instability resulting from the second mechanism may not be predicted by using VW-MRI, as presumably those aneurysms with thin walls do not enhance; nor can the thinning of their wall be reliably appreciated with the current limitations in spatial resolution. Whether a complementary imaging modality like DCE, which can detect an increase in wall permeability independent from wall contrast enhancement, has a role in those unstable, thin walled aneurysms has not been investigated.43

Clinical application of VW-MRI in intracranial aneurysms

In 2009 Park et al. were the first to image an intracranial aneurysm wall using a black-blood MRI protocol (1.5 T). Although contrast was not administered in this case, it opened a new line of imaging research.21 Since then, many groups have investigated the potential value of AWE as a biomarker of aneurysm instability using (mostly) 3 T VW-MRI protocols. Several themes are clearly emerging. These are summarized below. In addition, we offer our perspective from a high-volume neurovascular center where VW-MRI is in routine clinical use.

Ruptured intracranial aneurysms

The initial report using VW-MRI to evaluate intracranial aneurysms was in a small cohort of patients with aneurysmal SAH.44 In each of these five patients, the ruptured aneurysm demonstrated thick, circumferential AWE. Notably, three of these patients harbored additional aneurysms which did not show any enhancement. This striking first characterization of ruptured aneurysms using contrast-enhanced VW-MRI led many to postulate that it could be used clinically to help define the site of rupture, especially in patients with multiple aneurysms.

Since this time, numerous studies have confirmed that the vast majority (85–100%) of patients with aneurysmal SAH harbor an aneurysm with vessel wall enhancement.28,30–32,45,46 Furthermore, when the degree of enhancement was qualitatively or quantitatively graded, most ruptured aneurysms (50–75%) had more prominent enhancement compared to unruptured aneurysms.31,32,46,47 In some cases, conspicuous focal enhancement can be seen which correlates with aneurysm substructures, e.g. apical blebs, confirmed to be the site of rupture during surgical exploration.30,31 The enhancement patterns seen in ruptured aneurysms contrast sharply with those seen in unruptured aneurysms; however, overlap does exist. Most small, incidental aneurysms do not enhance (typically 70%).28,31,48,49 When enhancement is seen in incidental aneurysms, it is more often mild.31,32 While marked variability exists in the manner of assessing and grading “enhancement,” i.e. measures of thickness, intensity, location/homogeneity, all studies have been able to use enhancement characteristics to segregate “stable” and “unstable” aneurysms in a statistically significant manner. Two separate meta-analyses of approximately 500 aneurysms show that enhancement is associated with unstable or ruptured status with an OR of 20–34.50,51

At our institution, VW-MRI is a routine part of ruptured aneurysm evaluation. Most patients with spontaneous SAH have a single aneurysm and clinical decision making is relatively straightforward. The ruptured aneurysm should have some degree of enhancement, with thick, circumferential enhancement most commonly observed. In patients with SAH and multiple intracranial aneurysms, differential AWE is strongly weighed in deciding which aneurysm is given treatment priority. Infrequently, patients with aneurysmal SAH present with multiple, avidly enhancing aneurysms (Figure 5).

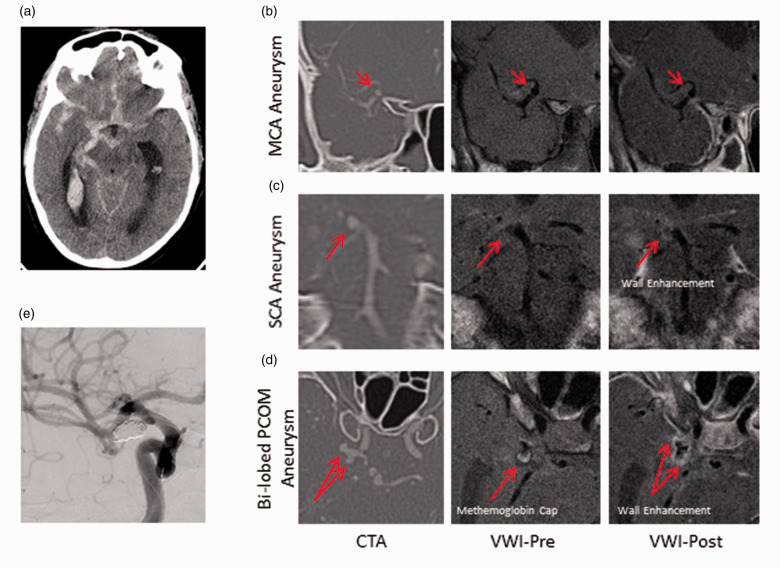

Figure 5.

Multiple enhancing aneurysms in a patient with SAH. A 58yF smoker presented with worst headache of life. (a) CT head with R > L basal cistern SAH and IVH. (b) to (d) CTA, VW-MRI pre/post-contrast images of a non-enhancing right MCA aneurysm (b), an enhancing right SCA aneurysm (c), and an enhancing, bi-lobed right PCOM aneurysm (d). Arrows denote the aneurysm in each slice. Note the presence of T1 bright signal at the tip of the posteriorly oriented lobe of the PCOM aneurysm which may represent methemoglobin. (e) Only the PCOM aneurysm was coiled as this was judged to be the site of rupture. CTA: computed tomography angiography; MCA: middle cerebral artery; PCOM: posterior communicating artery; SCA: superior cerebellar artery; VWI: vessel wall imaging.

What about a patient who presents with spontaneous SAH and a single, non-enhancing intracranial aneurysm? If high-quality imaging is obtained, can a ruptured aneurysm fail to demonstrate wall enhancement? Perhaps surprisingly, less than 200 ruptured aneurysms evaluated with VW-MRI have been reported in the literature. Of this cohort, there are no more than eight possible cases in which suspected, ruptured aneurysms failed to demonstrate wall enhancement. Unfortunately, there is inadequate imaging and clinical details to fully scrutinize these cases. Indeed, in the absence of surgical exploration, the ability to truly establish with certainty the rupture status of an aneurysm is questioned.28,31,32,45 Regardless, best available evidence of the negative predictive value of non-enhancement for rupture status is approximately 96%. Therefore, when faced with a patient with spontaneous SAH and a non-enhancing aneurysm, the clinician should give pause (Figure 6). Alternative sources of rupture should be considered. Overwhelmingly, these aneurysms will continue to be treated. However, until larger, prospective series are collected with intra-operative confirmation of rupture status, the answer to these questions remains unknown.

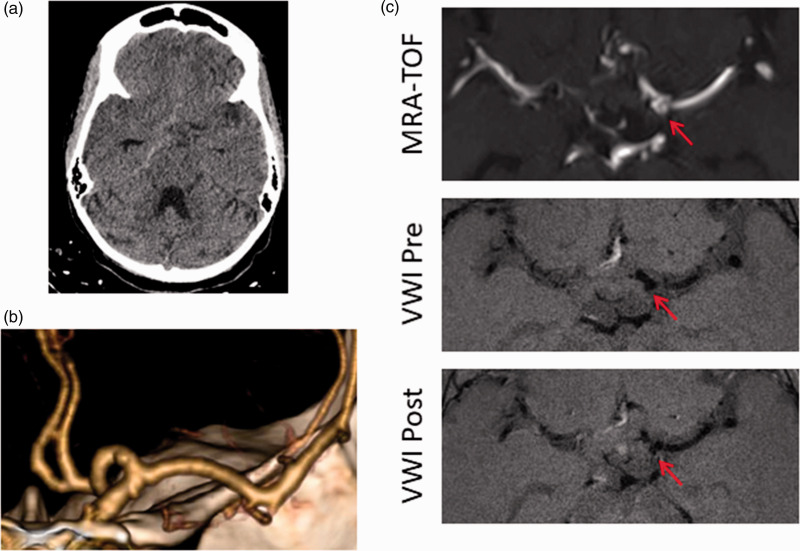

Figure 6.

Spontaneous SAH in a patient with an incidental, non-enhancing aneurysm. 22yF with sickle cell disease admitted in sickle crisis has sudden onset headache. (a) CT with right basal cistern SAH; (b) CTA reconstruction demonstrates a small left A1 aneurysm; and (c) Axial MRA (top), VW-MRI pre-contrast (middle), and VW-MRI post-contrast (bottom) images demonstrate no enhancement of the aneurysm. Arrow denotes aneurysm. This aneurysm was judged not to have ruptured and was not treated (incorrect hemorrhage pattern, non-enhancement of the aneurysm, alternative explanation). Patient has been followed for four years with aneurysm stability and no recurrent hemorrhage. MRA: magnetic resonance angiography; TOF: time of flight; VWI: vessel wall imaging.

Unruptured intracranial aneurysms

Given the strong correlation of AWE and ruptured aneurysms, and a growing body of evidence that wall inflammation may be a biologic driver for aneurysm formation and rupture,52–54 several groups hypothesized that AWE in unruptured aneurysms was associated with an unstable phenotype. To date, most of these studies are retrospective in nature.

The definition of an “unstable” aneurysm varies widely between studies. In earlier studies, “unstable” often included aneurysms that were growing or changing morphologically, and patients with cranial nerve palsies, sentinel headaches, or aneurysmal SAH. Edjlali et al.28 found enhancement in 27/31 unstable aneurysms versus 22/77 stable aneurysms. In another study, Hu et al.30 found 12/14 enhancing aneurysms were unstable. In both of these studies, wall enhancement was the only factor differentiating stable from unstable aneurysms. Nagahata et al.31 evaluated 61 ruptured aneurysms and 83 unruptured aneurysms. They showed that 99% of ruptured aneurysms enhanced in comparison to only 18% of unruptured aneurysms. Furthermore, the ratio of strong to faint enhancement was 3:1 versus 0.38:1, respectively. A meta-analysis of 6 studies and 505 aneurysms51 showed that enhancement carried a 20-fold OR for an “unstable” phenotype. Even when ruptured aneurysms were excluded, AWE still carried an 11-fold OR for instability, i.e. growing or “symptomatic.” More recently, Edjlali et al.’s32 expanded cohort study included a secondary analysis removing ruptured aneurysms that demonstrated enhancement was still able to predict “instability” albeit with lower sensitivity. Similarly, Omodaka et al.46 quantitatively demonstrated increasing degrees of enhancement in stable compared to evolving compared to ruptured aneurysms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of relevant studies investigating the association between wall enhancement and instability in saccular aneurysms.

| Study | Study design | Imaging sequence | Definition of unstable an. | Enh. pattern classification | No. of patients (an.) | No. of stable an. | No. of all unstable an. (ruptured an.) | Enhancement rate in stable an. | Enhancement rate in all unstable an. (only unruptured unstable an.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edjlali et al.28 | Retrospective case/control | 3 T, 3D T1w FSE | Ruptured, symptomatic, evolving | CAWE present /absent | 87 (108) | 77 | 31 (17) | 28.5% | 87% (78.5%) |

| Hu et al.30 | Retrospective case/control | 3 T, 3D T1w FSE | Ruptured, symptomatic, evolving | Enh. present /absent | 25 (30) | 19 | 11 (6) | 15.8% | 100% (100%) |

| Nagahata et al.31 | Retrospective case/control | 3 T, 3D MSDE T1w FSE | Ruptured | Strong /faint /no enh. | 117 (144) | 83 | 61 (61) | 4.8% strong, 13.2% faint | 73.8% (NAa) strong, 24.6% (NAa) faint |

| Fu et al.29 | Retrospective case/control | 3 T, 3D T1w and T2w | Symptomatic | CAWE present /absent | 37 (45) | 22 | 23 (0) | 27.3% | 69.6% (69.6%) |

| Wang et al.47 | Retrospective case/control | 3 T, 3D T1w FSE | Ruptured | Entire /partial /no enh. | 91 (106) | 87 | 19 (19) | 65.2% entire, 8.0% partial | 52.6% (NAa) entire, 47.4% (NAa) partial |

| Edjlali et al.32 | Retrospective case/control | 3 T, 3D T1w FSE | Ruptured, symptomatic, evolving | Thick CAWE /thin CAWE /focal enh. /no enh. | 263 (333) | 276 | 57 (26) | 15.6% thick CAWE, 16.3% thin CAWE, 6.5% focal | 57.9% (54.8%) thick CAWE, 17.5% (9.7%) thin CAWE, 3.5% (6.5%) focal |

| Vergouwen et al.19 | Retrospective longitudinal study | 3 T and 7 T, 3D T1w TSE | Ruptured, evolving | Enh. present /absent | 57 (65) | 61 | 4 (2) | 24.6% | 100% (NAb) |

| Matsushige et al.35 | Retrospective longitudinal study | 1.5 T, 3D T1w FSE | Evolving | Enh. present /absent | 60 (60) | 33 | 27 (0) | 15.1% | 48.1% (48.1%) |

An: aneurysm; CAWE: circumferential wall enhancement; Enh: enhancement; FSE: fast spin echo; MSDE: motion-sensitization driven equilibrium; TSE: turbo spin echo.

Not applicable as the study classified unstable = ruptured aneurysm.

Not applicable as VW-MRI was performed before rupture.

Other studies have explored the relationship between AWE and known risk factors of rupture. For example, several groups have shown that wall enhancement status is correlated with aneurysm size, location, morphology, and the PHASES score, a five-year rupture risk prediction tool dependent on patient- and aneurysm-specific parameters.48,55–57 Unfortunately, the findings are not concordant in all studies, but likely reflects small patient cohorts. In addition, Backes et al.49 showed that aneurysm size was a strong determinant of wall enhancement even in a group of predominantly small, unruptured aneurysms <7 mm. This has particular significance as an imaging biomarker of aneurysm instability would be most impactful in these patients.

Recently, the first retrospective, longitudinal series of AWE have been reported.19,58 Vergouwen et al.19 followed aneurysms evaluated by VW-MRI overtime (median follow-up = 27 months). Four of 19 enhancing aneurysms grew or ruptured and all of the 46 non-enhancing aneurysms were stable. Matsushige et al.58 performed VW-MRI on a cohort of 60 aneurysms that were previously followed over a two-year period. They showed that wall enhancement was significantly less frequent in stable aneurysms than in aneurysms with morphological change. Moreover, enhancing aneurysms were more likely to demonstrate an asymmetric growth pattern.

The pathophysiological underpinnings of inflammation and abnormal flow dynamics are increasingly well validated, and recently reviewed by Samaniego et al.59 The predictive power of AWE on VW-MRI remains to be determined in larger, multi-center, prospective registries.

Future directions

The biological basis of wall enhancement remains theoretical. While it is not explicitly necessary to know how or why wall enhancement works to use it as a biomarker for aneurysmal rupture risk, additional work to define what wall enhancement truly represents will help guide the context and applications for its clinical use. To this end, advances in technology and improvements in both the spatial and contrast resolution may improve its use.

The literature to date strongly suggests that VW-MRI in its current form (despite the limitations outlined above) may be sufficient to inform clinical decision making by identifying aneurysms with a higher risk of rupture. While perhaps less useful for larger aneurysms (>7 mm), this would be especially useful for small (<7 mm) unruptured aneurysms that are typically not treated. A large prospective trial to assess the natural history of small aneurysms with and without wall enhancement could prove transformative. Serial VW-MRI in this and other contexts would also be informative. Can AWE disappear over time? Does enhancement always pre-date rupture? These questions remain to be answered.

Conclusion

VW-MRI is an emerging modality which offers a fundamentally different perspective by focusing on the pathology within the vessel wall as opposed to traditional imaging paradigms that prioritize the vessel lumen. A growing body of evidence suggests that enhancement in an unruptured aneurysm may be a marker of an unstable phenotype, and that enhancement in the setting of SAH may be a marker of recent rupture. Importantly, the absence of aneurysm enhancement may reflect a stable, unruptured phenotype. The widespread implementation of VW-MRI in routine clinical practice will be facilitated by larger, multi-center prospective studies to validate wall enhancement as a biomarker of aneurysm instability.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Corrado Santarosa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5994-4477 Branden Cord https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9120-5989 Pervinder Bhogal https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5514-5237

References

- 1.Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, et al. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etminan N, Rinkel GJ. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: development, rupture and preventive management. Nat Rev Neurol 2016; 12: 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Rooij NK, Linn FH, van der Plas JA, et al. Incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review with emphasis on region, age, gender and time trends. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78: 1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bijlenga P, Gondar R, Schilling S, et al. PHASES score for the management of intracranial aneurysm: a cross-sectional population-based retrospective study. Stroke 2017; 48: 2105–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, 3rd, et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 2003; 362: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etminan N, Rinkel GJ. Cerebral aneurysms: cerebral aneurysm guidelines-more guidance needed. Nat Rev Neurol 2015; 11: 490–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindenholz A, van der Kolk AG, Zwanenburg JJM, et al. The use and pitfalls of intracranial vessel wall imaging: how we do it. Radiology 2018; 286: 12–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandell DM, Mossa-Basha M, Qiao Y, et al. Intracranial vessel wall MRI: principles and expert consensus recommendations of the American Society of Neuroradiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017; 38: 218–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frosen J, Piippo A, Paetau A, et al. Remodeling of saccular cerebral artery aneurysm wall is associated with rupture – histological analysis of 24 unruptured and 42 ruptured cases. Stroke 2004; 35: 2287–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kataoka K, Taneda M, Asai T, et al. Structural fragility and inflammatory response of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. A comparative study between ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Stroke 1999; 30: 1396–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan DM, Mahaney KB, Brown RD, Jr, et al. Aspirin as a promising agent for decreasing incidence of cerebral aneurysm rupture. Stroke 2011; 42: 3156–3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Investigators UJ, Morita A, Kirino T, et al. The natural course of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in a Japanese cohort. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2474–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasan D, Chalouhi N, Jabbour P, et al. Early change in ferumoxytol-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging signal suggests unstable human cerebral aneurysm: a pilot study. Stroke 2012; 43: 3258–3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vakil P, Ansari SA, Cantrell CG, et al. Quantifying intracranial aneurysm wall permeability for risk assessment using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI: a pilot study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 953–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mossa-Basha M, Hwang WD, De Havenon A, et al. Multicontrast high-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging and its value in differentiating intracranial vasculopathic processes. Stroke 2015; 46: 1567–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandell DM, Matouk CC, Farb RI, et al. Vessel wall MRI to differentiate between reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and central nervous system vasculitis: preliminary results. Stroke 2012; 43: 860–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obusez EC, Hui F, Hajj-Ali RA, et al. High-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging: spatial and temporal patterns of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and central nervous system vasculitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1527–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skarpathiotakis M, Mandell DM, Swartz RH, et al. Intracranial atherosclerotic plaque enhancement in patients with ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vergouwen MDI, Backes D, van der Schaaf IC, et al. Gadolinium enhancement of the aneurysm wall in unruptured intracranial aneurysms is associated with an increased risk of aneurysm instability: a follow-up study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 1112–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez J, Elkind MSV, Petito C, et al. The contribution of HIV infection to intracranial arterial remodeling: a pilot study. Neuropathology 2013; 33: 256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JK, Lee CS, Sim KB, et al. Imaging of the walls of saccular cerebral aneurysms with double inversion recovery black-blood sequence. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 30: 1179–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portanova A, Hakakian N, Mikulis DJ, et al. Intracranial vasa vasorum: insights and implications for imaging. Radiology 2013; 267: 667–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakurai K, Miura T, Sagisaka T, et al. Evaluation of luminal and vessel wall abnormalities in subacute and other stages of intracranial vertebrobasilar artery dissections using the volume isotropic turbo-spin-echo acquisition (VISTA) sequence: a preliminary study. J Neuroradiol 2013; 40: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato T, Matsushige T, Chen B, et al. Wall contrast enhancement of thrombosed intracranial aneurysms at 7T MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 1106–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Lou X, Li Y, et al. Imaging investigation of intracranial arterial dissecting aneurysms by using 3 T high-resolution MRI and DSA: from the interventional neuroradiologists’ view. Acta Neurochir 2014; 156: 515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalsoum E, Negrier AC, Tuilier T, et al. Blood flow mimicking aneurysmal wall enhancement: a diagnostic pitfall of vessel wall MRI using the postcontrast 3D turbo spin-echo MR imaging sequence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018; 39: 1065–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornelissen BMW, Leemans EL, Coolen BF, et al. Insufficient slow-flow suppression mimicking aneurysm wall enhancement in magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging: a phantom study. Neurosurg Focus 2019; 47: E19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edjlali M, Gentric JC, Regent-Rodriguez C, et al. Does aneurysmal wall enhancement on vessel wall MRI help to distinguish stable from unstable intracranial aneurysms? Stroke 2014; 45: 3704–3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fu QC, Guan S, Liu C, et al. Clinical significance of circumferential aneurysmal wall enhancement in symptomatic patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a high-resolution MRI study. Clin Neuroradiol 2018; 28: 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu P, Yang Q, Wang DD, et al. Wall enhancement on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging may predict an unsteady state of an intracranial saccular aneurysm. Neuroradiology 2016; 58: 979–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagahata S, Nagahata M, Obara M, et al. Wall enhancement of the intracranial aneurysms revealed by magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging using three-dimensional turbo spin-echo sequence with motion-sensitized driven-equilibrium: a sign of ruptured aneurysm? Clin Neuroradiol 2016; 26: 277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edjlali M, Guedon A, Ben Hassen W, et al. Circumferential thick enhancement at vessel wall MRI has high specificity for intracranial aneurysm instability. Radiology 2018; 289: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omodaka S, Endo H, Niizuma K, et al. Quantitative assessment of circumferential enhancement along the wall of cerebral aneurysms using MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1262–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Hespen KM, Zwanenburg JJM, Harteveld AA, et al. Intracranial vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging does not allow for accurate and precise wall thickness measurements: an ex vivo study. Stroke 2019; 50: e283–e284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsushige T, Shimonaga K, Mizoue T, et al. Focal aneurysm wall enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging indicates intraluminal thrombus and the rupture point. World Neurosurg 2019; 127: e578–e584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen N, von der Brelie C, Trick D, et al. Vessel wall enhancement in unruptured intracranial aneurysms: an indicator for higher risk of rupture? High-resolution MR imaging and correlated histologic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018; 39: 1617–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimonaga K, Matsushige T, Ishii D, et al. Clinicopathological insights from vessel wall imaging of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2018; 49: 2516–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudson JS, Zanaty M, Nakagawa D, et al. Magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging in human intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. Epub ahead of print 7 December 2018. DOI: STROKEAHA118023701. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Quan K, Song J, Yang Z, et al. Validation of wall enhancement as a new imaging biomarker of unruptured cerebral aneurysm. Stroke 2019; 50: 1570–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frosen J, Piippo A, Paetau A, et al. Remodeling of saccular cerebral artery aneurysm wall is associated with rupture: histological analysis of 24 unruptured and 42 ruptured cases. Stroke 2004; 35: 2287–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kataoka K, Taneda M, Asai T, et al. Difference in nature of ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Lancet 2000; 355: 203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, et al. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1254–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi H, Liu X, Liu P, et al. Complementary roles of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and postcontrast vessel wall imaging in detecting high-risk intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matouk CC, Mandell DM, Gunel M, et al. Vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging identifies the site of rupture in patients with multiple intracranial aneurysms: proof of principle. Neurosurgery 2013; 72: 492–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omodaka S, Endo H, Niizuma K, et al. Circumferential wall enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging is useful to identify rupture site in patients with multiple cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2018; 82: 638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omodaka S, Endo H, Niizuma K, et al. Circumferential wall enhancement in evolving intracranial aneurysms on magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging. J Neurosurg. Epub ahead of print 1 October 2019. DOI: 10.3171/2018.5.JNS18322. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Wang GX, Wen L, Lei S, et al. Wall enhancement ratio and partial wall enhancement on MRI associated with the rupture of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 566–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lv N, Karmonik C, Chen S, et al. Relationship between aneurysm wall enhancement in vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging and rupture risk of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2019; 84: E385–E391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Backes D, Hendrikse J, van der Schaaf I, et al. Determinants of gadolinium-enhancement of the aneurysm wall in unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2018; 83: 719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Zhu C, Leng Y, et al. Intracranial aneurysm wall enhancement associated with aneurysm rupture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Radiol 2019; 26: 664–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Texakalidis P, Hilditch CA, Lehman V, et al. Vessel wall imaging of intracranial aneurysms: systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2018; 117: 453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gounis MJ, Vedantham S, Weaver JP, et al. Myeloperoxidase in human intracranial aneurysms preliminary evidence. Stroke 2014; 45: 1474–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ollikainen E, Tulamo R, Frosen J, et al. Mast cells, neovascularization, and microhemorrhages are associated with saccular intracranial artery aneurysm wall remodeling. J Neuropath Exp Neur 2014; 73: 855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoh BL, Hosaka K, Downes DP, et al. Stromal cell derived factor-1 promoted angiogenesis and inflammatory cell infiltration in aneurysm walls. J Neurosurg 2014; 120: 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartman JB, Watase H, Sun J, et al. Intracranial aneurysms at higher clinical risk for rupture demonstrate increased wall enhancement and thinning on multicontrast 3D vessel wall MRI. Brit J Radiol 2019; 92: 20180950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang GX, Wen L, Lei S, et al. Relationships between aneurysmal wall enhancement and conventional risk factors in patients with intracranial aneurysm: a high-resolution MRI study. J Neuroradiology 2019; 46: 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu P, Qi H, Liu A, et al. Relationship between aneurysm wall enhancement and conventional risk factors in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a black-blood MRI study. Interv Neuroradiol 2016; 22: 501–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsushige T, Shimonaga K, Ishii D, et al. Vessel wall imaging of evolving unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2019; 50: 1891–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samaniego EA, Roa JA and Hasan D. Vessel wall imaging in intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019; 11: 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed]