Abstract

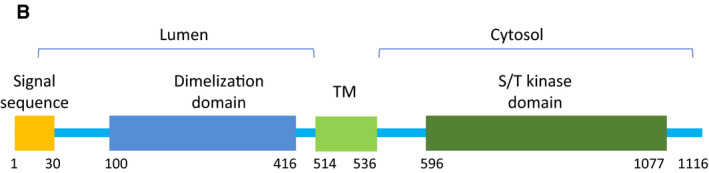

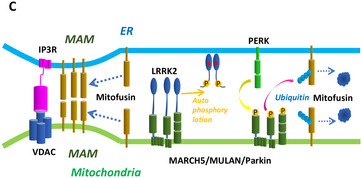

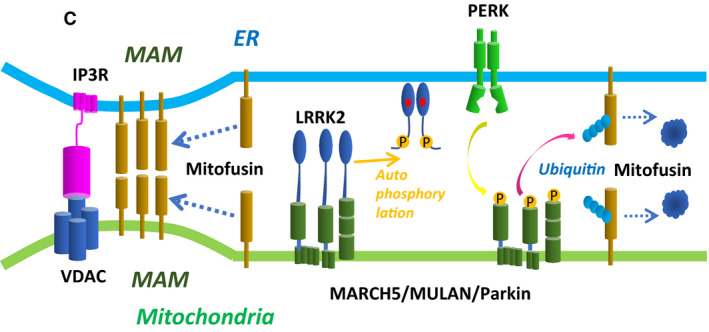

We acknowledge Marius Lemberg, Heidelberg, Germany, for his constructive criticism on the molecular structure representation of PERK in our article (Figs 5B and EV5) brought to our attention shortly after online publication. In this study, we found that ER‐located PERK phosphorylated the mitochondria‐located E3 ubiquitin ligases. To address the question how the kinase domain of PERK reaches its target sites, we speculated that PERK may be released from ER under tunicamycin‐mediated ER stress. To evaluate this possibility, we expressed double‐tagged PERK in MEF cells and detected PERK in cytosol and MAM. By immunoblot, N‐terminal shed (Myc‐negative) PERK, the molecular weight of which was similar to the wild‐PERK, was detected by C‐terminal FLAG (Fig 5B). Mis‐interpretation of the structural model of PERK led us to conclude erroneously that the N‐terminal hydrophobic segment of PERK as the transmembrane domain could be shed by S1P and released from ER. We agree with M. Lemberg that this segment is part of the signal sequence peptide and that the transmembrane domain is located between the dimerization and kinase domains in PERK (see corrected Fig 5B, https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9NZJ5). Therefore, shed PERK in the cytosol in Fig 5B was not the cytoplasmic part of PERK but PERK with a signal sequence defect, which may be not correctly incorporated into ER. Thus, the schematic model of PERK in Fig 5B, “transmembrane domain”, is herewith changed to “signal sequence peptide”. Further, we have adjusted the graphical representation of PERK in the cellular model overview (Fig 7C).

Figure 5B.

Original.

Figure 5B.

Corrected.

Figure 7C.

Original.

Figure 7C.

Corrected.

Given that a cytoplasmic form of PERK of the predicted molecular weight of 55kDa estimated based on the structure of PERK (as corrected in Fig 5B) was not detected (Fig 5B), the PERK cleavage‐release model, which was proposed in the original text, seems insufficiently supported. We have therefore corrected the graphical representation of PERK and removed the Western blot data in Fig 5B, as well as Fig. EV5, which served to illustrate the Western blot data in Fig 5B and contained the schematics on the structure of PERK and experimental design of the tagging experiment. We have changed the respective original text paragraphs in the results (Page 9, lines 4 in left column to lines 5 in right column) and discussion sections (Page 13, lines 38–52, in the left column) as detailed below.

The authors regret this error and any confusion it may have caused.

We have changed the respective original text in the results from:

“Considering the close proximity between PERK and E3 ubiquitin ligase at the MAM, it is possible that PERK directly phosphorylates E3 ubiquitin ligases under ER stress. Alternatively, PERK may be cleaved by site‐1 protease (S1P), an ER‐localized protease (Ye et al., 2000; Lichtenthaler et al., 2018), giving the soluble cytoplasmic domain of PERK access to E3 ubiquitin ligases. Indeed, PERK contains an RxxL motif, a known requirement for S1P processing (Espenshade et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2000), on both sites of its transmembrane domain (Fig EV5A). Consistent with this idea, under tunicamycin treatment, we detected the cytoplasmic domain of PERK in the cytosol in MEFs transfected with PERK, but not in MEFs transfected with PERK(R33A), which lacks the putative S1P recognition site (Figs 5B and EV5B)”.

to:

“Considering the close proximity between PERK and E3 ubiquitin ligase at the MAM, it is possible that PERK directly phosphorylates E3 ubiquitin ligases under ER stress. Alternatively, PERK may be cleaved by an ER‐localized protease (Ye et al., 2000; Lichtenthaler et al., 2018), giving the soluble cytoplasmic domain of PERK access to E3 ubiquitin ligases”.

We have changed the panel and respective text related to Fig 5B from:

“(Upper panel) Diagram showing full‐length PERK tagged with Myc at the N‐terminus and FLAG at the C‐terminus (M‐PERK‐F). The S1P recognition sequence R33SLL is mutated to A33SLL (M‐PERK(R33A)‐F).(Lower panel) Immunoblot of PERK and PERK(R33A) from transfected MEFs under tunicamycin. MAM fraction and cytosol were extracted from transfected MEFs by the Percoll gradient method. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody against the FLAG epitope. Precipitated proteins were subjected to SDS/PAGE, and blots were stained with antibody as indicated to the right”.

to:

“Schematic representation of PERK. Diagram showing full‐length PERK. TM, transmembrane domain; S/T kinase, serine/threonine kinase”.

We have changed the respective original text in the Discussion from:

“Alternatively, the cytoplasmic domain of PERK (a.a. 36–114) may need to be released from the ER membrane in order to gain access to its targets. Several proteases localized at the ER membrane cleave ER‐localized proteins (Ye et al., 2000; Lichtenthaler et al., 2018). Notably in this regard, ER membrane–bound ATF6, another ER stress sensor, is cleaved by S1P under ER stress, resulting in release of its cytoplasmic domain, which subsequently enters the nucleus (Ye et al., 2000). As with ATF6, PERK contains an RxxL motif, a known requirement for S1P processing (Espenshade et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2000), on both sites of its transmembrane domain (Fig EV5A). Under ER stress, the cytoplasmic domain of PERK was present in the cytosol, supporting the idea that the cytoplasmic domain of PERK is cleaved by ER stress, and then phosphorylates mitochondria‐bound E3 ubiquitin ligases”.

to:

“Alternatively, the cytoplasmic domain of PERK may be released from the ER membrane in order to gain access to its targets. Several proteases localized at the ER membrane cleave ER‐localized proteins (Espenshade et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2000; Lichtenthaler et al., 2018). Notably in this regard, ER membrane‐bound ATF6, another ER stress sensor, is cleaved by S1P under ER stress, resulting in release of its cytoplasmic domain, which subsequently enters the nucleus (Ye et al., 2000). However, it remains unclear whether the cytoplasmic domain of PERK is cleaved by ER stress and whether cleaved PERK released from ER phosphorylates mitochondria‐bound E3 ubiquitin ligases”.