Abstract

The social context and cultural meaning systems shape caregivers' perceptions about child growth and inform their attention to episodes of poor growth. Thus, understanding community members' beliefs about the aetiology of poor child growth is important for effective responses to child malnutrition. We present an analysis of caregivers' narratives on the risks surrounding child growth during postpartum period and highlight how the meanings attached to these risks shape child care practices. We collected data using 19 focus group discussions, 30 in‐depth interviews and five key informant interviews with caregivers of under‐five children in south‐eastern Tanzania. Parental non‐adherence to postpartum sexual abstinence norms was a dominant cultural explanation for poor growth and development in a child, including different forms of malnutrition. In case sexual abstinence is not maintained or when a mother conceives while still lactating, caregivers would wean their infants abruptly and completely to prevent poor growth. Mothers whose babies were growing poorly were often stigmatized for breaking sex taboos by the community and by health care workers. The stigma that mothers face reduced their self‐esteem and deterred them from taking their children to the child health clinics. Traditional rather than biomedical care was often sought to remedy growth problems in children, particularly when violation of sexual abstinence was suspected. When designing culturally sensitive interventions aimed at promoting healthy child growth and effective breastfeeding in the community, it is important to recognize and address people's existing misconceptions about early resumption of sexual intercourse and a new pregnancy during lactation period.

Keywords: cultural schema, poor child growth, postpartum, sexual abstinence, stigma, taboos, Tanzania

Key messages.

‘Kubemenda’ refers to causing growth faltering in a child as a result of violating the postpartum sex taboos. Parent's violation of postpartum sexual abstinence norms is the dominant cultural explanation for growth faltering among young children in Kilosa, Morogoro region, Tanzania.

Abrupt and complete weaning is a common practice to avoid poor child growth based on kubemenda

Health workers apply the same cultural schemas based on kubemenda as caregivers in providing medical services

To align health messages with local beliefs, health workers may want to integrate the concept of kubemenda into their educational and health promotion materials.

1. INTRODUCTION

The cultural and social context within which caregiving occurs has a large impact on the conceptualization of child growth, and it informs how caregivers regard the growth of their children. For instance, in south‐eastern Tanzania, height is culturally perceived as unrelated to nutrition or health but rather as a function of God's will and/or heredity. Thus, in this context, short stature in a child is considered a normal condition that should not worry the parents (Mchome, Bailey, Darak, & Haisma, 2019). Additionally, it has been shown that in Ethiopia (Belachew et al., 2018) and in Tanzania (Dietrich Leurer, Petrucka, & Msafiri, 2019), infants who are 6 months younger are not exclusively breastfed based on the cultural belief that mother's milk alone is not adequate to provide for an infant's growth needs. These findings suggest that understanding the sociocultural context of child growth and how it influences caregivers' actions is essential to efforts to prevent childhood malnutrition. In this study, we seek to identify the social context and the cultural schemas that underlie community members' beliefs about and perceptions of the aetiology of poor child growth. We also use cognitive anthropological cultural schema theory to present an analysis of caregivers' narratives on the risks surrounding child growth during the early postpartum period. Finally, we highlight how the meanings caregivers attach to these risks shape child care practices.

Mary Douglas (1966) has argued that each culture has its own ‘taboos’ associated with bodily pollution that represent a framework for social order. When such a framework is in place, society knows who is to blame when these taboos are violated. Thus, for every risk that exists, blame is placed on a particular person by the community/social group. Communities' concerns about the risks surrounding child health related to the sexual behaviour of the parents during the postpartum period have been documented in several studies for West African countries (Achana, Debpuur, Akweongo, & Cleland, 2010); Riordan & Wambach, 2010) and for East African countries, including Tanzania (Mabilia, 2000; Mbekenga, Lugina, Christensson, & Olsson, 2011; Mbekenga, Pembe, Darj, Christensson, & Olsson, 2013). Qualitative research conducted in Tanzania has shown that both men (Mbekenga, Lugina, et al., 2011) and women (Mbekenga, Christensson, Lugina, & Olsson, 2011) are concerned about the initiation of sex during the breastfeeding period, based on the belief that doing so negatively affects the health of the baby.

The custom of prolonged postpartum sexual abstinence is also associated with increased risks of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, as men may feel free to engage in extramarital sex while women are required to remain abstinent (Achana et al., 2010; Cleland, Mohamed, & Capo‐Chichi, 1999; Iliyasu et al., 2006). Concerns about the negative health implications and the risks associated with prolonged abstinence norms for parents and their children have also been voiced by Swazi women (Shabangu & Madiba, 2019) and Tanzanian parents (Mbekenga et al., 2013; Mbekenga, Christensson, et al., 2011). Additionally, it has been pointed out that these postpartum sex norms can perpetuate gender inequalities, as women are expected to strictly adhere to postpartum sexual abstinence norms, whereas men are not (Mbekenga et al., 2013).

In previous research in Tanzania, postpartum sex taboos have been discussed in relation to breastfeeding (Mabilia, 2000; Mabilia, 2005), gender inequalities and maternal and family health (Mbekenga et al., 2013). The current study contributes to the existing evidence on the beliefs around postpartum sexual activities by focusing on how these beliefs relate to child growth and how they affect caregiving practices that are relevant to child growth. This analysis is part of large ethnographic study that sought to shed light on the sociocultural context of child growth in south‐eastern Tanzania. It should be noted that the interviewers did not ask caregivers directly about their beliefs around postpartum taboos but that these views emerged inductively from caregivers' accounts of the sociocultural contexts that underlie healthy/poor growth in children. The results of the analysis deepen our understanding of how social context shapes beliefs and practices around (poor) child growth.

1.1. Cultural schemas theory

According to D'Andrade (1884), a community's cultural meaning systems are composed of shared cultural schemas—that is, knowledge structures—that allow people to identify objects and events. These schemas may include perceptions, beliefs, emotions, goals and values (D'Andrade, 1992; Hill & Cole, 1995). Moreover, these schemas are context‐specific and can function as powerful sources of knowledge and meanings (D'Andrade, 1992). Some schemas are specific to individuals, whereas others—that is, cultural schemas—are shared by a group of people and are highly internalized (D'Andrade, 1992; Fichter & Rokeach, 1972; Garro, 2000). These schemas develop throughout life, as individuals interact with the context in which they live. Because cultural schemas are not static, individuals may experience cultural change over time. Thus, people may internalize cultural schemas differently at different life stages (D'Andrade, 1992; Garro, 2000).

As Douglas (1966) has argued, when socioculturally shared values—which define what is good and bad behaviour—are internalized, they become a template for guiding individual behaviour, and for morally judging oneself and others (Rokeach, 1968). Due to their evocative function, adherence to cultural values, such as avoiding morally unacceptable sexual behaviour during the postpartum period, may elicit feelings of satisfaction, whereas violations of cultural values may provoke anxiety (Mathews, 2012) and blame (Douglas, 1966). People in different societies have different ways of conceptualizing and ascribing meaning to a particular health condition (e.g., poor child growth) depending on their community's cultural meaning systems (Bailey & Hutter, 2006; Metta et al., 2015). For this ethnographic study, we applied these insights from cultural schema theory to examine how local people construct the risks surrounding child growth during the early postpartum period (breastfeeding period) and how their perceptions of these risks influence caregivers' actions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Fieldwork setting

This study was conducted in a single rural village in the Kilosa district of the Morogoro region of Tanzania. Even though Morogoro has high levels of food production, the prevalence of stunting among under‐five children in this region is high, at 33%. The fieldwork setting has been described in detail elsewhere (Mchome et al., 2019), but in short, the study community consists of two main ethnic groups: (1) the native Bantu group, to which the majority of the population belong; and (2) the Maasai group, which is a Nilotic minority group of people who migrated to this area in the past two decades in search of pasture for their livestock. Because of the region's high prevalence of stunting and anaemia (66%), as well as its rural characteristics, we considered it an interesting location for our study on caregivers' beliefs about the aetiology of poor growth among young children and on how these beliefs shape caregivers' responses to growth faltering. In the study village, there is no health facility. Thus, the people in the village depend on health services from nearby health facilities (dispensaries) outside of the ward, which are approximately 3–6 km away. The staff working in the dispensaries includes clinical officers, nursing officers, assistant nurses and laboratory technicians. The local health system in the village is pluralistic, as caregivers have access to pharmaceuticals, traditional medicine and growth monitoring services.

2.2. Study participants and data collection

This study draws on an ethnography on child growth that engaged focus group discussions (FGDs), in‐depth interviews (IDIs), participant observations (POs), and key informant interviews (KIIs) with caregivers of under‐five children (who included biological mothers and fathers of under‐five children, regardless of the children's nutritional status), elderly women, traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and community health workers (CHWs). For the current paper, we drew from data collected through FGDs, IDIs and KIIs only.

We conducted FGDs in order to obtain a broad range of information on the cultural construction of ideal/poor child growth in the community. The IDIs were used to collect rich information on caregivers' personal experiences and their individual perspectives on the growth of under‐five children. The key informant interviews with the TBAs and CHWs enabled us to gather detailed contextual information relevant to the issue of child growth in the community from the perspective of health service providers. It should be noted that the CHWs referred to in this study were not professional health care providers. In the Tanzanian context, CHWs are individuals selected from the community and trained according to government standards to provide an integrated and comprehensive package of interventions, including child growth monitoring services—particularly in areas where there is no health facility (like in the study village).

The caregivers were selected for inclusion in the study using purposive sampling, which was performed with the support of local administrative leaders, CHWs and social networks the researchers developed during the fieldwork. Data collection was conducted in two phases: the first round of fieldwork (from July to September 2015) involved 19 FGDs, whereas the second round of fieldwork (August to September 2016) involved 30 IDIs and five KIIs. We conducted the FGDs first in order to gain a general understanding of the issues related to the growth of under‐five children in the community. We then transcribed and coded all of the FGDs before proceeding with the second phase of the fieldwork. The second phase of data collection was delayed not only by the time needed to process the FGD data and to adapt the interview guides but also by arrival of the rainy season, which runs from approximately November to July.

Two Tanzanian female researchers (the principal investigator (PI) and a research assistant) with a postgraduate social science background in sociology were involved in the data collection. Both researchers had advanced training and extensive experience in qualitative methods. All of the FGDs and IDIs were conducted in Swahili, digitally recorded, and fully transcribed verbatim by two transcribers, including the research assistant. Whereas most of the interviews were conducted in the participants' homes, the FGDs were conducted in different venues in the village, such as school classrooms (after school hours) and at the PI's or the participants' home compounds. Each FGD consisted of six–eight participants. Drawing on their research experience with sexual and reproductive health issues, the researchers were able to help shy participants to open up, particularly when discussing the sensitive topic on the link between sexual behaviour and child growth. The interview and the discussion topic guides were open‐ended and covered various topics, including perceptions of child growth, contextual factors that underlie child growth, child feeding practices and experiences with growth monitoring services (Please see Supporting Information). Most of the information on the link between postpartum sexual behaviour and child growth emerged as participants were sharing their conceptualizations of healthy and poor child growth and when they were providing their views on the socio‐cultural contexts that underlie poor growth among young children in the community. Data collection continued until the saturation point was reached.

2.3. Data analysis

Following completion of data transcription, the first author reviewed all of the transcripts and checked them for accuracy before importing them to NVivo 11 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Australia). All of the transcripts were analysed in their original Swahili language. The quotes presented in this article were translated during the writing of the paper. Through reading of the texts for general understanding, the researchers were able to identify the concepts and the statements of importance to participants that refer to a potential association between parental sexual behaviour during the postpartum period and child growth. The analysis process took place at two levels: (1) inductive and deductive codes were developed; (2) and these codes were categorized into groups of themes and family codes, as described in Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey (2011).

2.4. Ethical issues

Full ethics approval was obtained for the study from the University of Groningen Research Ethics Committee and the Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) through the Medical Research Coordinating Committee (MRCC) of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR). Additionally, permission was granted by the regional, district and village leaderships prior to the commencement of the research activities. Full information was provided to participants verbally and in written form in Swahili, and written/thumbprint consent was obtained. The participants' confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by conducting the discussions/interviews in private locations and removing all identifiers from the interview transcripts prior to data analysis. In the quotations that appear in this paper, pseudonyms are used to protect the participants' identities.

3. RESULTS

In data analysis, three themes emerged: (1) Construction of sex taboos and risks around child growth during postpartum period; (2) shame and/or honour as the outcomes of non‐/adherence to postpartum sex taboos; and (3) the influence of the cultural context on child care practices.

3.1. Construction of sex taboos and risks around child growth during postpartum period

3.1.1. The postpartum sex taboos

In the study community, the early postpartum period is culturally constructed as the ‘nurturing’ period (kipindi cha kulea) during which a mother is expected to dedicate herself to the task of breastfeeding to ensure that her baby grows well. It is widely believed that sexual relations between couples during the lactation period can endanger a child's health/growth. Thus, sexual abstinence is a dominant traditional practice that has been adopted to promote healthy child growth:

If you give your baby good care, s/he grows fast. S/he can even walk early if you do not spoil her/him. […]. On top of providing her/him with food, porridge, and protecting her/his body, you also do not sleep with your man. That is to enable her/him to grow fast. But if you crave that ‘thing’ (sex), the baby will be spoiled (ataharibika). S/he does not grow. (Older woman, FGD‐#06)

In the participants' cultural models, sexual abstinence had several meanings, ranging from total abstinence from sex for both parents to the mother having intermittent sex with the biological father (kulea na baba) and also to the mother abstaining while the father has sexual affairs with other women. There were variations in the length of postpartum sexual abstinence to enhance healthy growth, ranging from 40 days (arobaini) to two and a half years. Similarly, sex can be resumed when the child has been weaned or shows cultural markers of healthy growth, such as being able to walk or talk, being active or being able to comprehend the instructions of parents or caregivers.

The study found intergenerational differences in levels of adherence to these postpartum sexual norms. The older women in particular criticized younger couples for being more likely than preceding generations to rebel against postpartum sexual abstinence norms. The participants attributed the changes in levels of adherence to (1) globalization (utandawazi), which exposes young people to Western culture; (2) the availability of modern contraceptives; and (3) moral decay among younger couples. Some of the younger women described the postpartum sexual norms as an old‐fashioned way of nurturing children (imepitwa na wakati) and acknowledged that they were not following them:

Some stay (abstain from sex) for two years. But for many current youths, they usually stay for one year. I myself can't stay for two years (laughing). I stay for only three months and tell my man, ‘Hello sir, bring it’ (laughing). (Mother, FGD‐#05)

3.1.2. ‘Kubemenda’: Cultural explanation for poor child growth

The dominant cultural explanation for poor child growth during the early postpartum period is kubemenda, also referred as kubenanga/kukatikiza. According to the Swahili dictionary, the word kubemenda/bemenda (also chira) is a verb that means to harm the baby through the violation of cultural norms (BAKITA, 2016). Moreover, in the study context, the term kubemenda can mean that the parents are causing their baby to become ill or show symptoms of poor growth and development by failing to adhere to postpartum sexual norms.

Regardless of their ethnicity, age or sex, the study participants strongly believed that the main cause of poor growth among the children in the community was that parents were violating postpartum sex taboos:

The main thing that greatly spoils children here in our community is sex (tendo la ndoa). Whether you provide your kids with fruits or not, God helps them to grow well. It is that thing (sex) that mainly affects the baby. (Mother, FGD‐#01)

You find that a mother has a little child but keeps on doing sex with her husband. That is when they ruin a child's growth. Instead of giving the child an opportunity to grow, they interrupt it. (Father, IDI‐#04)

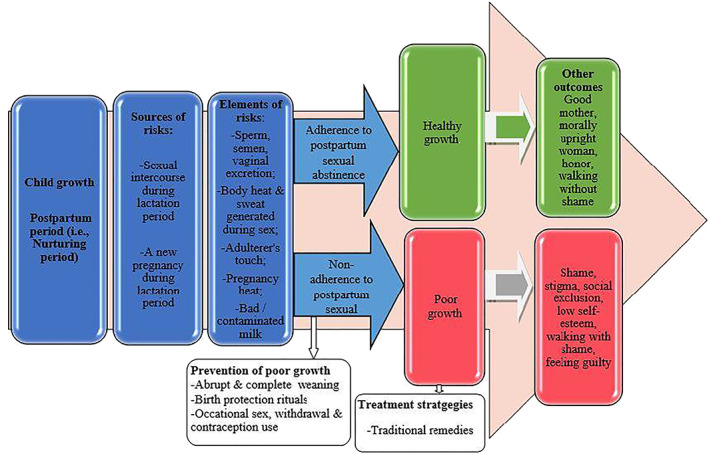

Most of the consequences attributed to kubemenda overlapped with the biomedical symptoms of malnutrition (utapiamlo; see Table 1 for a full list). The parents frequently used schemas that referred to kubemenda in interpreting the aetiology, the consequences and the markers of poor growth episodes in both their own children and in the children of others. The case of Jamila, a community health worker who was the mother of an under‐five child, is presented in Box 1. Her story shows that the belief that kubemenda is a cause of poor child growth was held not only by the local people but also by some elite community health professionals, such as traditional birth attendants and community health workers (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Growth and health outcomes resulting from non‐adherence to postpartum sex taboos

| Markers | Postpartum period |

|---|---|

| Physical outcomes |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Illnesses | frequent diarrhoea |

| loose, whitish stool | |

| whitish/milky vomits | |

| unhealthiness (hana afya) | |

| Fatal danger | death |

| Developmental milestones | unsteady and weak limbs |

| lack of strength to crawl, stand, or walk on schedule | |

| mental retardation | |

| lack of strength to cry loudly | |

| Play and physical activity | general body weakness (mdhaifu) |

| lack of energy | |

| not lively/lack of dynamism (hachangamki) | |

| not playful. | |

| abnormal calmness (kapooza kama zezeta) | |

| wretchedness (mnyongemnyonge) | |

| Body immunity | intermittent sickness (anaumwaumwa/magonjwa hayampitii mbali) |

| frequent fever (homa za mara kwa mara) | |

| Eating habits | eating too much. |

| food craving. | |

| Cognitive development | low intelligence (akili yake ndogo). |

Box 1. A new pregnancy during the lactation period—An aetiology of poor child growth.

|

"P: In the past, I myself happened to spoil the growth of my second child (nilimbemenda mtoto wangu) … [.] The problem was my pregnancy, as when you sleep with the baby, the warmth of my body hurts him. So, the baby became weak (akanyongea). I: What did he look like? P: He was getting frequent fever. And when we took him to the hospital (growth monitoring clinic), his weight was considerably dropping. As parents, we clearly knew that we had already ‘spoiled’ the growth of the baby (tumeshambemenda). The nurses asked, ‘Why does the weight of the child drop?’ We said, ‘We do not know’. They said, ‘Please prepare lishe (a local porridge made of a mixture of cereals, mainly sorghum, maize, and groundnuts) for the baby.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ But in reality, I knew that I was already pregnant … [.] As I am pregnant, my body heat might be the thing that was making him stunted (a general term used to refer to poor growth). Initially, the child was very active (alikuwa mchangamfu sana) and very playful. But there came a time when he could not run from here to there (about 30 meters). You see?!...[.] In the past, he could take a can, go to the bombani (a nearby water point) and play with other kids. But as a result of my pregnancy, he became weaker (alinyongea) and his growth faltered." |

FIGURE 1.

Cultural construction of the aetiology of poor child growth during the postpartum period

3.1.3. Behaviours that can endanger child growth

The participants identified two parental behaviours that can endanger a child's growth during the early postpartum period: (1) having sexual intercourse during the lactation period and (2) becoming pregnant with another child during the lactation period (kukatikiza/kumruka mtoto).

Risks arising from the parents engaging in sexual intercourse

The analysis showed that the caregivers' cognitive representations of the notion that parents having sex during the early postpartum period puts their child's growth at risk was influenced by their cultural schemas regarding impurities that are carried by bodily substances generated during sexual intercourse. Several of the participants depicted sexual intercourse during lactation as morally unacceptable behaviour, referring to it as, for example, a dirty or filthy game (mchezo mchafu), or stupidity (upuuzi/uwendawazimu). They expressed the belief that the bodily substances—particularly the father's sperm (mbegu za mwanamme) or semen (manii/shahawa) and the mother's vaginal excretions (uchafu wa mama)—the body heat (joto la mwili) and the sweat (jasho) generated during sex can endanger the growth of a baby. They also believed that genital excretions enter a woman's breasts through the blood vessels and pollute the milk. Thus, they posited, when the baby breastfeeds after the mother has had sex, he or she will contract diarrhoea, vomit and eventually lose weight. In the following, a traditional birth attendant explains the aetiology of such an infection:

When the dirties (semen) enter in your womb, they flow towards the breasts. If they can flow and make someone pregnant, do you think they cannot flow up to the breasts? That is when you affect the baby. As s/he sucks the milk, s/he also sucks the dirties. S/he then starts to vomit exactly same things as the man's dirties. Surprisingly, even when the breasts are pressed, plenty of the man's dirties come out. When you press, the milk is dirty. The milk that comes out is not the normal white or yellowish, no! The milk changes and become watery (maziwa ya maji). You then know that this one is causing poor growth in the baby. S/he does not care for the baby. S/he is continuing with her ‘things’ (sex). (Traditional Birth Attendant, KII‐#03)

The participants also explained that, when the baby sucks in the couple's ‘dirties’, these fluids flow and spread to the baby's limbs, weaken her/his joints and render her/him unable to stand or walk:

When a man ‘penetrates’ you (sex), the seeds (sperm) that he pours into you go to your breasts. So, when you breastfeed, the baby sucks those seeds of a man. The seeds then reach up to here (showing the knees). Then the baby's joints become weak (ananyong'onyea viungo). It is because of those seeds. (Older woman, FGD‐#05)

Additionally, the participants said they believe that engaging in sexual intercourse generates body heat [joto] or sweat [jasho] that is harmful to a baby's growth because it (1) makes the mother's breast milk hot and (2) it causes the child to become ill and weak overall, particularly if one of the parents was touching or carrying the baby before he or she had washed her/his body properly. The participants expressed the belief that like ingesting genital fluids, sucking in hot breast milk can cause a baby to experience vomiting, diarrhoea and weak limbs. Although occasional sex for the father of a breastfeeding baby is perceived as less harmful, sleeping with another man, not the biological father, was feared as a lethal danger as it was believed to expose the baby to a foreign body heat and semen/sperms which are incompatible with her/his blood.

Risks associated with a new pregnancy while lactating (kukatikiza)

According to the participants, another reason why the parents having sexual intercourse during the postnatal period endangers the growth of a breastfeeding baby is that it can expose the woman to an early pregnancy during lactation. Conception during the breastfeeding period—which is locally referred as kukatikiza or kumruka mtoto, that is, skipping over a child—was characterized not just as a threat to child growth but as a lethal danger. The participants said they believe that the unborn baby generates harmful heat (joto la mimba, literally, pregnancy heat) that alters the mother's body temperature, which, in turn, spoils her breast milk by making it hot, light (maziwa mepesi), yellowish or brownish. If a mother does not notice that her body temperature has changed and continues to breastfeed, her baby's growth or life can be endangered. Many participants believed that when the baby sucks ‘dirty milk’ (maziwa machafu), he or she will suffer from diarrhoea, vomiting and poor motor development. The breast milk of an expectant mother—which was culturally framed as ‘the milk of the baby in the womb’—was also described as toxic to the breastfeeding baby, based on the perception that the milk is then incompatible with the physiology of the baby who has already been born. Phrases like ‘s/he has sucked her fellow's milk’ were commonly used in the participants' explanations of the dangers associated with the breast milk of an expectant mother.

The participants warned that in addition to spoiling the mother's breast milk, the heat of a new baby (joto la mimba) can cause the breastfeeding baby to become ill (especially with fever), lose weight and experience overall body weakness (kunyongea), particularly when the mother holds, cuddles or sleeps with the baby. These dangers are said to exist regardless of whether the baby is still breastfeeding or has been weaned:

What affects the growth of the (breastfeeding) baby is joto (body heat). Let's say I become pregnant while I still have this little baby (pointing to her little baby). I must embrace her when we sleep. That joto is what spoils her. The joto of the pregnancy is very dangerous. It spoils the (breastfeeding) baby. That's why you are not allowed to sleep with her (breastfeeding baby), as when you sleep with her, the joto of her fellow in the womb affects her. (Mother, FGD‐#01)

3.2. POSITIONING OF MEN AND WOMEN IN THE CONTEXT OF POSTPARTUM SEXUAL ABSTINENCE

Although both parents should abstain from sex for a prolonged period of breastfeeding to avoid endangering their child's growth, abstinence was emphasized more for the mother than for the father. This appears to be because a woman is culturally constructed as mlezi (the one who nurtures) and as the parent who better understands the value of the baby because she experienced the labour pains (uchungu) of bringing the baby into the world. By contrast, as men are believed to be sexually weaker than women, and thus to have no ability to remain sexually abstinent for longer periods of time, male extramarital sexual relations during the postpartum period are culturally condoned. Many of the women upheld male sexual dominance by characterizing a father's extramarital affairs during the breastfeeding period as responsible acts, based on the premise that this behaviour protected the baby from poor growth. Additionally, most of the women said are tolerant of their partner having extramarital affairs for the sake of their child's healthy growth:

It is better for him [partner] to get out of wedlock [extramarital sex] provided that my child grows. Even when he comes back home late, I usually don't ask him anything. Even if I hear that he has a girl [lover] outside, I never ask him anything. (A mother of an under‐five child, unknown age)

Some of the women even reported that they are pleased when their partner has extramarital sex during the breastfeeding period, as it reduces the pressure on them to have sex and gives them the freedom to concentrate on nurturing their baby (kulea). Additionally, in a few of the FGDs with mothers, a man who had no extramarital relations during the breastfeeding period was described as msumbufu (a nuisance) and thus as a problem for a morally upright nursing mother:

P1: When he returns home at 12 midnight (12:00pm), that means that he has already fulfilled his sexual needs. When he reaches home, what he does is to take a bucket of water and have a bath. Then he sleeps.

I: As a mother, what do you think of that?

P1: I find it to be very good because I don't want any nuisance, I'm nurturing my baby. I know I am nurturing my baby well, so s/he grows well as s/he has good care (malezi bora).

P2: In terms of my freedom to nurture my baby, I also think it (men's extramarital affairs) is okay. I am the one who experiences the labor pains when my pelvis widens for the birth of the baby. So I just perceive it to be okay. The one that goes out (has sex with other women) is better. Let him go, as long as he provides for the family as usual. Let him go and do his work (sex) (laughing). No more trouble! My sister, giving birth is too tough (laughing). You take off all of your clothes (laughing). (Mothers, FGD‐#06)

Whereas the majority of the women said they are tolerant of their partner having extramarital sexual affairs during the postpartum period, a few of them said they feel compelled to resume sex early out of fear of contracting HIV:

It is hard to wait (abstain) for so long. A man cannot tolerate it. He goes out (having extramarital sex). That is when the diseases come. Imagine you are abstaining for two years, your fellow (partner) goes out, he gets HIV, when he comes and penetrates you (akikuingilia). That is when he infects you. (Mother, IDI‐#02)

According to the participants, marrying more than one wife is a strategy that men use to cope with these postpartum sexual restrictive norms; as when one wife is nursing, the husband can turn to another wife to fulfil his sexual needs:

I: What are men's coping strategies during the lactation period?

P1: Let me answer that question honestly (all participants laugh). Nowadays, most of us fathers see that it is better to add another woman so that when this one is nurturing (breastfeeding), I go to the other woman. I marry another wife, a legal wife (laughter).

P2: It works perfectly well when you have two wives. But if you only have one wife you need to use an extra IQ (akili ya ziada) to fool your wife with kind words so that she upholds abstinence while you secretly eat out (extramarital sex). (Fathers, FGD‐#05)

It was, however, acknowledged by fathers of under‐five children that having multiple wives would limit their ability to provide for their children, as maintaining multiple families would be difficult given their meagre resources.

3.3. SHAME OR HONOUR AS THE OUTCOMES OF NON‐/ADHERENCE TO POSTPARTUM SEX NORMS

3.3.1. Honour

Based on the community's gender role schemas, maintaining sexual abstinence during the breastfeeding period (kipindi cha kulea) was considered an important cultural quality of a strong, ‘morally upright woman’ and ‘a good mother’:

A good mother is one who nurtures her baby well (abstaining from sex during the lactation period). She is not sexually active; after giving birth, she knows that ‘I have one job, to nurture my baby’. She is never ‘sick’ [sexually aroused]. She can even fight with her husband to avoid sex. When her husband touches her, she tells him, ‘Stop it! Let me nurture my baby.’ Until the baby has grown older, that is when she meets with her husband. (Older woman, FGD‐#02)

Successful abstaining from sex during breastfeeding not only provides a mother with the satisfaction of knowing that she is helping her child grow; it ensures that the community, and particularly the older women who safeguard the postpartum sexual abstinence norms, will honour her for doing what is morally right:

After giving birth, if you do not involve yourself with sex, that is when we say that you nurture your child well. Your baby will eventually have healthy growth. Even elders will say ‘Ooh, she is indeed nurturing her baby well’. (Older woman, IDI‐#05)

3.3.2. Shame

In case of early pregnancy or when a breastfeeding baby portrays signs associated with non‐adherence to postpartum sexual abstinence norms, blame is laid on a mother for being unable to remain abstinent, or to resist pressure to have sex from her husband. A woman who becomes pregnant while still nursing or who has a baby who appears to be growing poorly was described using negative stereotypes such as ‘sexual maniac (ana kiranga)’, ‘dirty woman (mwanamke mchafu)’, ‘reckless’, ‘stupid’, ‘too lusty’ and ‘overly jealousy of her husband’. The violation of postpartum sexual norms was severely criticized by the female participants, and particularly by the older women, with comments such as ‘She has spoiled the growth of her baby (amemharibu mtoto)’; ‘She did not provide good care to her baby’; ‘She uses her baby (anamtumia mtoto)’ and ‘She has played with the health of her baby’.

Most of the mothers reported that they are very strict about remaining abstinent while breastfeeding, particularly during the first postnatal year, in order to meet social expectations for mothers, to ensure that their babies grow well and to avoid bringing shame on themselves and their families. Some said they waited to have sex until when their babies could walk, as walking is an important cultural marker of healthy growth and of the parents' adherence to abstinence:

Sex does not happen to me now. I'm afraid. My baby's growth will be spoiled (atabemendeka). […]. I would rather wait until my child starts to walk. (Mother, IDI‐#01)

The participants reported that mothers are often stigmatized if they have a child whose poor growth suggests that they have been violating sexual abstinence norms. For example, mothers may be subjected to judgmental attitudes, gossip, social exclusion and public shaming, usually in response to visible signs and symptoms perceived to result from the parents' sexual behaviour. Many of the participants said they see children with poor growth and their mothers as laughable; recounting that when these families appear in public, they are often ridiculed and gossiped about by others:

We Masai are used to holding the cattle. So, when s/he (the one with poor growth) holds it s/he trembles (lacks the energy to hold it). Even her fellow children know that this one has already been spoiled (amebemendwa). They laugh. You also laugh at her/him saying, ‘Aaah, I did a good job to nurture my baby, but my fellow has spoiled her child's growth’ (laughing). When she passes, the mother's eyes become less confident, s/he feels shy as her baby is falling down frequently (lacks strength to walk) […]. It is shameful even before men, as they will say, ‘Do you see that woman, she has spoiled her baby.’ They start to gossip. Is that not a shame? (Older woman, FGD‐#07)

A child whose poor growth was attributed to the violation of sexual norms was referred to by the participants as ‘spoiled’ (mtoto aliyeharibiwa) or ‘screwed’ (mtoto ali‐yechezewa/aliyefanyiwa matusi/ngono). Many of the participants described a child with that condition as socially unacceptable, noting that unlike a healthy‐looking child, the community members will avoid carrying her/him:

First of all, s/he is too weak and her/his skin is folded like that of an elderly person (ngozi imejikunga kama ya mzee). You never feel interested in carrying her/him. S/he becomes her/his ‘mama's baby’ [mtoto wa mama], and never the neighbors' baby. When a child is healthy, a neighbor usually caries her/him, the mother does not struggle to carry her/him alone. But when s/he shows signs that s/he has been spoiled (amebemendwa), s/he ends up being mtoto wa mama. (Father, FGD#‐02)

The participants reported that the stigmatization of ‘spoiled babies’ (ambao wamebemendwa) and the blame placed on their mothers caused these mothers to walk around with shame and low self‐esteem and limited their freedom to interact with others:

It is a big shame for a woman. You feel ashamed particularly when you are around other women whose children look healthy but yours do not. You then tend to stay alone at home; you never go out to chat with fellow women, as they will laugh at you. (Mother, IDI‐#10)

According to the participants, the stigma associated with poor growth ascribed to kubemenda was even apparent in interactions with health workers who were providing health services at child care clinics:

You find that your child has been spoiled (amebemendwa) but your fellows' children have not. Even when you go to the doctor (health worker) s/he must scold you. S/he tells you, ‘You have become ‘too dirty’ (having sex), and are spoiling your baby (mpaka umembemenda mtoto wako).’ S/he must scold you because when s/he looks at your colleagues' babies, s/he sees that they are healthy, but your baby has swollen cheeks, weak legs, and a swollen belly. (Older woman, FGD‐#02)

Although most of the participants said they consult health facilities and growth monitoring clinics primarily when a child is having frequent fevers or has insufficient weight, they added that the fear of being stigmatized may cause caregivers to avoid accessing and utilizing growth monitoring services and medical care for their children. For example, a mother who conceived prematurely (kukatikiza) may fear being chastised by health workers when she seeks medical care for her child, especially if her child's health suggests that she has violated sex taboos:

I: When a child is noted to have been spoiled, is there any treatment that people use to rectify her/his growth?

P: A big percent of them (mothers) hide themselves. You find that a mother is afraid to take the child to the hospital as she has two little children, so she decides to leave behind the older one and only take the newborn. That is what a big percent of women do. They are afraid that when they go there, they will be scolded (watachambwa) by nurses. That is why the child whose growth has been spoiled (aliyebemendwa) is left behind, and the new baby is taken to the dispensary (child care clinic). (Father, FGD‐#03)

A community health worker (CHW) remarked that kubemenda is a problem in the community. When he was asked whether, during growth monitoring clinics, he has ever identified a child whose poor growth was indicative of non‐adherence to postpartum sexual abstinence norms, he replied:

Yes, some of them have been spoiled (wamebemendwa). I can recognize it. You find that a mother has three little children at the ages for growth monitoring. This means that they are all under‐five. So I know that there is a dirty game that parents are playing on the baby. It is not acceptable to create three children within five years. (Community health worker, KII‐#01)

The above findings indicate how socioculturally shared values become a template for guiding individual behaviour and for morally judging oneself and others. They also show that kubemenda schemas have permeated the biomedical system in the study community, as even knowledgeable health workers apply them when providing medical services.

3.4. THE INFLUENCE OF THE CULTURAL CONTEXT ON CHILD CARE PRACTICES

It appears that caregivers' beliefs about the consequences of sexual pollution during the lactation period guided their actions, including their decisions about which preventive and curative child growth strategies to use. In this section, we show how caregivers' beliefs about the risks of having sex during the early postpartum period shape how they prevent and treat poor growth in their breastfeeding babies.

3.4.1. Strategies for preventing poor growth ascribed to kubemenda

As we noted earlier, the dominant traditional strategy for preventing a child's growth from being endangered by sexual activities is for the parents to abstain from sexual intercourse for the entire breastfeeding period. To avoid sexual temptation, couples are supposed to sleep in separate beds or rooms as soon as the baby is born. Alternatively, the mother and the infant may move into her parents' or her in‐laws' home for an extended period of time and return when the baby is able to walk. When the early resumption of sex between the partners becomes necessary, a number of strategies may be used to minimize a child's vulnerability to poor growth, including engaging in birth protection rituals, having only intermittent sexual relations with immediate bathing, using the withdrawal method, using condoms or other contraception and abruptly weaning the child.

In this analysis, abrupt weaning emerged as a common practice used by caregivers to avoid poor child growth. This is particularly likely to occur when (a) a mother conceives early (kukatikiza); (b) the partners feel the need to resume sex earlier; (c) it appears that the child has grown sufficiently, especially if he or she is able to walk independently; (d) the pressure on the partners to have sex becomes unbearable; or (e) the child shows signs of poor growth that are indicative of a parental violation of sex taboos. In most cases, when an immediate weaning is deemed necessary, the child relies on porridge to survive. Following the cessation of breastfeeding, the child is customarily taken to a grandmother to prevent her/him from being harmed by the expectant mother's body heat (the unborn baby's heat).

3.4.2. Seeking health care to treat poor growth attributed to kubemenda

Based on their cultural meaning systems, the caregivers in the study setting expressed a strong belief that Western medicine cannot treat a baby whose poor growth is the result of the violation of postpartum sexual abstinence norms. According to the participants, traditional remedies are more effective in such cases. Thus, the majority of the parents reported using such remedies when they noticed the signs of poor growth in a child ascribed to kubemenda, including bowel incontinence; diarrhoea with white‐coloured stools; insufficient strength to crawl, stand or walk on schedule; or a swollen stomach and swollen cheeks. As in the case of the prevention strategies, which types of therapists, herbal remedies, and procedures the participants turned to depended on the specific customs of their tribe. Among the health resources the parents reported consulting when a child's poor growth was indicative of kubemenda were traditional healers (waganga), elders (wazee), TBAs (wakunga) and people with appropriate knowledge about traditional herbs:

I: What do people in your community do when they notice that a child's growth has been spoiled?

R: We take them to the traditional healers for some cleansing so that they can regain their body strength and walk again. (Mother, FGD‐#01)

When you see that the baby has contracted excessive diarrhea, or has frequent fevers, you realize that the condition of this child has gone astray. You consult an older person (mzee), s/he then finds mtaalam (traditional expert) who comes and ‘ties a child with medicine’ (anamfunga mtoto dawa). We usually do not take the baby to the hospital. We use our local medicines (dawa za kienyeji). When given the medicine, the baby starts to walk again and gets well. (Older woman, IDI‐#2)

4. DISCUSSION

This ethnographic study aimed to provide a detailed analysis of cultural beliefs regarding the link between postpartum sex taboos and child growth and development and how these beliefs influence child care practices, in a low‐income rural setting in south‐eastern Tanzania. Parental non‐adherence to postpartum sexual abstinence norms emerged as the dominant cultural explanation for ill health/poor growth and development among the children in the study community. As a dominant discourse, this set of beliefs shaped parents' behaviour and decisions about the preventive and curative services they considered relevant to child growth. The current study extends previous research conducted in Tanzania on sex taboos as a dominant discourse situating maternal and child health during the postpartum period (Mabilia, 2000; Mbekenga et al., 2013) by providing important insights into how cultural norms influence childrearing practices and caregivers' attention to episodes of poor growth of their children on the basis of symptoms and perceived aetiology. At the policy level, this analysis points to the need to reconsider how health education and promotion messages about poor child growth are communicated to members of the community. In the following discussion, we explain how our findings may be relevant for public health policy.

4.1. Sexual intercourse and a new pregnancy as aetiology of poor child growth

In this study, the term kubemenda was used by participants to refer to an ‘act’ of causing poor growth to a child through parental non‐adherence to postpartum sexual abstinence. The postpartum sexual abstinence was observed mainly to prevent a child from ill‐health/poor growth. The relevance of postpartum sexual abstinence in promoting healthy child growth has also been highlighted in studies that have shown how this norm relates to HIV (Achana et al., 2010), breastfeeding and sexuality after delivery (Desgrées‐Du‐Loû & Brou, 2005; Mabilia, 2005) and parenting (Ntukula, 2004). The caregivers' belief that a child's poor growth and development can be attributed to the parents' failure to adhere to postpartum sexual abstinence norms clearly differs from biomedical explanations of the aetiology of childhood illnesses and poor growth. These findings imply that as biomedical experts, we need to understand how caregivers assign meaning to the growth of their children and take such meaning‐giving into account when designing and implementing interventions aimed at promoting child growth and development.

The observation that fathers are allowed to enjoy sex with other women whereas mothers are expected to remain abstinent is worth noting, as in addition to representing a source of emotional violence for wives (Desgrées‐Du‐Loû & Brou, 2005); this double standard could reproduce gender inequalities with negative health implications for families, including increasing their risk of HIV infection (Mbekenga et al., 2013). Couples should make decisions about postpartum sexual abstinence jointly and be knowledgeable about safe sex.

Our analysis found evidence that there have been some cultural changes regarding postpartum sexual norms in the younger generation, as younger couples appear to be observing shorter periods of sexual abstinence. Similar findings have been reported from other communities in East Africa (Mbekenga et al., 2013), West Africa (Achana et al., 2010) and Southern Africa (Flax, 2015). The older parents' criticisms of the younger generation's failure to adhere to these sexual rules reported in this study were expected, as ‘the pace of culture change can be overwhelming to individuals when the experienced culture change requires a fundamental shift in thinking’ (LaRossa, Harkness, & Super, 1997). However, even though we found signs that cultural changes have been occurring in the study setting, we also observed that mothers with a malnourished child were often stigmatized for not adhering to sexual norms. These findings suggest that whereas schemas and meanings within cultures change over time (Garro, 2000), some elements of a given culture are retained if they are deemed important (Popenoe, 2012). Thus, we would argue that postpartum sexual taboos are still powerful cultural explanations for poor child growth, even as the meanings of some concepts, such as perceptions regarding the appropriate duration of abstinence, change.

4.2. Abrupt cessation of breastfeeding as a strategy for preventing poor child growth

Whereas cultural schemas are a necessary part of individual actions, they are not always beneficial, as some turn out to have adverse effects (Bailey & Hutter, 2006; Strauss & Quinn, 1997). In this study, we found that the schema regarding the risks associated with having sexual intercourse and a new pregnancy during the postpartum period can lead to harmful behaviours, which, if left unaddressed, cannot only jeopardize ongoing efforts to promote infant breastfeeding but can endanger the lives of babies. The belief in kubemenda can cause caregivers to stop breastfeeding abruptly and prematurely. This practice is problematic, as breastfeeding has been shown to have benefits for the general health, growth and development of infants (Munblit et al., 2016; Picciano, 2001; United Nations Children's Fund, 2018; Vennemann et al., 2009; Victora et al., 2016). There is evidence that the premature weaning of infants is dangerous (WHO, 2003), particularly in the context of Tanzania, where rates of infectious disease are high (MoHCDGEC, 2016). The premature transition to mixed feeding increases the risk of diarrhoea, infection, malnutrition and slow development in infants (De Zoysa, Rea, & Martines, 1991; Grummer‐Strawn & Mei, 2004; Harder, Bergmann, Kallischnigg, & Plagemann, 2005; Howie, Forsyth, Ogston, Clark, & Du Florey, 1990; WHO, 2003), which in traditional lore could be attributed to kubemenda. In addition, the weaning regimens used in the context of kubemenda—that is, taking a recently weaned infant with poor growth to a grandmother's home for recovery—should be seen as especially problematic, as a change in caregivers may increase the infant's vulnerability (Howard & Millard, 1997).

4.3. Use of health care services in the context of kubemenda

As our analysis has shown, the cognitive representations of kubemenda are also structured to guide the choice of curative actions. In the participants' cultural model, the symptoms and signs of malnutrition in breastfeeding babies are erroneously attributed to the quality of the mother's milk, which is believed to have been ‘polluted’ by the couple's genital excretions and by the harmful body heat of the mother if she is newly pregnant. Similarly, episodes of child diarrhoea, which are particularly common when a child starts to crawl/walk and when supplementary food is firstly introduced into the child's diet (MoHCDGEC, 2016), are attributed to the resumption of intercourse. In most such cases, traditional rather than biomedical care is sought to remedy health or growth problems in children. Similar approaches to managing childhood diarrhoea that is perceived to result from the violation of sexual taboos have been reported elsewhere in rural Tanzania (Mabilia, 2000). In addition, the role of folk beliefs in caregivers' decisions to seek care for their children from traditional healers rather than from health professionals for other health issues has been reported elsewhere in Tanzania (Mchome et al., 2019; Metta et al., 2015; Muela, Ribera, & Tanner, 1998). The tendency to turn to traditional healers we observed in this study should be taken seriously, as it may lead to delays in the diagnosis and the treatment of childhood illness. This issue is particularly critical, as dehydration caused by severe diarrhoea is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among young children in Tanzania (MoHCDGEC, 2016). The findings for our study setting, as well as results for the Kondoa district (Mabilia, 2000), may explain why the parents of an infant in Tanzania who becomes ill, particularly in a rural setting, are far less likely to seek professional advice if the child has diarrhoea (43%) than if the child has an acute respiratory infection and fever (MoHCDGEC, 2016).

Although the participants' reliance on traditional remedies could be mainly rooted in their cultural models, it likely also reflects their limited access to health resources, as there is no health facility in the study village. Thus, to promote the early diagnosis and the treatment of the symptoms of poor growth in children and to decrease the likelihood that harmful traditional practices will be employed, health programmers should create synergies between medical health personnel and community resource persons (CORPs), such as older women, TBAs and traditional healers in challenging traditional norms and increasing access to medical care. Such an alliance should focus on improving the capacity of CORPs to educate community members on the aetiology of poor child growth and to refer children with ill health or poor growth to medical clinics. However, as Mchome et al. (2019) observed, more operational research is needed to determine how CORPs can be successfully integrated into interventions targeting poor growth in children.

4.4. Naming and shaming of mothers and their poorly growing babies

In our study, we found that mothers and their poorly growing babies were subjected to stereotypes and acts of stigmatization by community members. Similar behaviours have been reported elsewhere (Mabilia, 2000; Mbekenga et al., 2013). As Narayan, Chambers, Shah, and Petesch (2000) have pointed out, stigma and shame can result in increasing isolation, as people become less able to participate in the traditions that bring communities together. In this study, we found that when a baby showed signs of poor growth considered indicative of kubemenda, the baby was often stigmatized, and the mother was frequently blamed and shamed, which seems to have resulted in the mother having low self‐esteem, and less freedom to interact with others in the community. Sen (1993) has described ‘being ashamed to appear in public’ and ‘not being able to participate in the life of the community’ as absolute forms of deprivation equal to hunger. Our observation that shame and stigma were associated with child malnutrition in the study setting is worth noting, as such behaviour may lead to injustices being directed at mothers and their babies. Additionally, from a psychological point of view (Rigby, 1969), as asserted in (Mabilia, 2000), and from a capability perspective (Sen, 1993), placing blame on mothers can be detrimental to their mental well‐being and can negatively influence their ability to care for their children.

Furthermore, the current study noted some weaknesses at health facility level in relation to child care services. The participants reported that health workers have stigmatized and scolded mothers during child growth monitoring when their babies had poor growth outcomes, particularly if they suspected that kubemenda played a role. As Tangney and Dearing (2002) observed, ‘shame is a painful and devastating experience in which the self is painfully scrutinized and negatively evaluated. [it] is likely to be accompanied by a desire to hide or escape from the interpersonal situation in question’ (Quoted in Reyles (2007). Similarly, the current study found that the shaming and scolding of caregivers by health care providers when their children were not growing well disincentivized mothers from taking their newly weaned infants (as a result of another pregnancy) or their poorly growing children to the maternal and child health clinics. Despite their biomedical knowledge, health workers may have been influenced by the kubemenda schemas in their cultural context. The stigmatizing behaviour observed among health workers is worth noting, as (1) it may interfere with children's access to health care and could lead to worse health and development outcomes and (2) it violates the fundamental human rights of mothers and their children, including their rights to receive respectful, dignified and humane care during growth monitoring (United Nations General Assembly, 1948, 1993). An association between the stigma of malnutrition and children's access to health care has also been reported in different contexts (Bliss, Njenga, Stoltzfus, & Pelletier, 2016; Howard & Millard, 1997; Mull, 1991; Nayar, Stangl, De Zalduondo, & Brady, 2014). The attitudes of health workers that were reported in the current study highlight the need to insist that health care providers separate their preconceived schemas from their professional duties.

4.5. Strengths and limitations of the study

As this study was conducted with a small group of people in a specific setting, the results should be viewed as contextual and limited to this kind of setting. Nevertheless, because the study participants included caregivers from different ethnic backgrounds, and given that prolonged postpartum sexual abstinence has been reported as the dominant traditional discourse underlying child health in other settings in Tanzania (Howard, 1994; Mabilia, 2000; Mabilia, 2005; Mbekenga et al., 2013), it is likely that the practices reported in this study are also found elsewhere.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the study community, poor child growth is often attributed to the parents having violated sexual abstinence norms during the postpartum period. Thus, prolonged sexual abstinence is a culturally acceptable strategy for promoting healthy growth—and for preventing poor growth—in children. Although the intention of the traditional discourse is to support and encourage child growth by promoting effective breastfeeding, it turns out to be a belief that has adverse effects, as it often leads to premature weaning in response to the early resumption of sex and a new pregnancy. Thus, this practice interferes with the right of children to be breastfed, in line with the recommendations of UNICEF (2018) and the WHO (2019). It also has implications for mothers' and children's fundamental human rights, as it subjects them to stigmatization by community members, including by health workers. Moreover, the traditional discourse motivates caregivers' responses and choices of curative services, with traditional healers being preferred to biomedical practitioners in handling episodes of poor growth in children. Based on our findings, we argue that to promote effective breastfeeding and healthy child growth in our study community and in similar settings in Tanzania, policy‐makers and nutritionists should seek to understand the local knowledge of and the schemas regarding poor child growth people employ in their community context when designing and implementing interventions.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

ZM, HH, AB, FK, and SD conceived and designed the experiments. ZM and FK performed the fieldwork. ZM, HH, SD, and AB analysed the data. ZM, HH, AB, FK, and SD wrote the paper. FK, HH, and SD oversaw the data collection process.

Supporting information

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research of the ‘Towards multi‐dimensional indicators of child growth and development’ task force was supported by the International Union of Nutritional Sciences. We acknowledge the support we received from research assistant Dotto Kezakubi and transcribers Joyce Silas and Neema Ghambishi during data collection and transcription, respectively. The invaluable support from the local leaders and the Community Health Workers throughout the fieldwork in the study setting cannot be overemphasized. We recognize special support of the community members who participated in and contributed to the successful generation of the current study results. We are indebted to Mr. Florence Kayombo—the head of IT unit of NIMR Mwanza—for the valuable support he provided to the first author while writing this manuscript. The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, Grant/Award Number: (NWO/WOTRO/VIDI, W01.70.300.002) supported this study.

Mchome Z, Bailey A, Kessy F, Darak S, Haisma H. Postpartum sex taboos and child growth in Tanzania: Implications for child care. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16:e13048 10.1111/mcn.13048

REFERENCES

- Achana, F. S. , Debpuur, C. , Akweongo, P. , & Cleland, J. (2010). Postpartum abstinence and risk of HIV among young mothers in the Kassena‐Nankana district of Northern Ghana. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12, 569–581. 10.1080/13691051003783339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A. , & Hutter, I. (2006). Cultural heuristics in risk assessment of HIV/AIDS. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 8, 465–477. 10.1080/13691050600842209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKITA . (2016). Kamusi Kuu ya Kiswahili (Second edi ed.). Nairobi, Kampala, Dar es Salaam, & Kigali: BAKITA & Longhorn Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Belachew, A. , Tewabe, T. , Asmare, A. , Hirpo, D. , Zeleke, B. , & Muche, D. (2018). Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers having infants less than 6 months old, in Bahir Dar, Northwest, Ethiopia: A community based cross sectional study, 2017. BMC Research Notes, 11, 768 10.1186/s13104-018-3877-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, J. R. , Njenga, M. , Stoltzfus, R. J. , & Pelletier, D. L. (2016). Stigma as a barrier to treatment for child acute malnutrition in Marsabit County, Kenya. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12, 125–138. 10.1111/mcn.12198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J. G. , Mohamed, M. A. , & Capo‐Chichi, V. (1999). Post‐partum sexual abstinence in West Africa: Implications for AIDS‐control and family planning programmes. AIDS, 13, 125–131. 10.1097/00002030-199901140-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrade, R. G. (1884). Cultural meaning systems In Shweder R. A. & LeVine R. A. (Eds.), Culture theory: Essays on mind, self and emotion (pp. 88–119). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrade, R. G. (1992). Schemas and motivations In D'Andrade R. G. & Strauss C. (Eds.), Human motives and cultural models (pp. 23–44). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Zoysa, I. , Rea, M. , & Martines, J. (1991). Why promote breastfeeding in diarrhoeal disease control programmes? Health Policy and Planning, 6, 371–379. 10.1093/heapol/6.4.371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desgrées‐Du‐Loû, A. , & Brou, H. (2005). Resumption of sexual relations following childbirth: Norms, practices and reproductive health issues in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Reproductive Health Matters, 13, 155–163. 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)25167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich Leurer, M. , Petrucka, P. , & Msafiri, M. (2019). Maternal perceptions of breastfeeding and infant nutrition among a select group of Maasai women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19, 8 10.1186/s12884-018-2165-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. (1966). Purity‐danger—an analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo In Purity and danger: An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Ark. [Google Scholar]

- Fichter, J. H. , & Rokeach, M. (1972). Beliefs, attitudes and values: A theory of organization and change. Review of Religious Research, 13, 144 10.2307/3509738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flax, V. L. (2015). “It was caused by the carelessness of the parents”: Cultural models of child malnutrition in southern Malawi. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11, 104–118. 10.1111/mcn.12073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garro, L. C. (2000). Remembering what one knows and the construction of the past: A comparison of cultural consensus theory and cultural schema theory. Ethos, 28, 275–319. 10.1525/eth.2000.28.3.275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. , & Mei, Z. (2004). Does breastfeeding protect against pediatric overweight? Analysis of Longitudinal Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System. Pediatrics, 113, e81–e86. 10.1542/peds.113.2.e81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder, T. , Bergmann, R. , Kallischnigg, G. , & Plagemann, A. (2005). Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: A meta‐analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162, 397–403. 10.1093/aje/kwi222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M. , Hutter, I. , & Bailey, A. (2011). Qualitative research methods. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D. H. , & Cole, M. (1995). Between discourse and schema: Reformulating a cultural‐historical approach to culture and mind. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 26, 475–489. 10.1525/aeq.1995.26.4.05x1065y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M. (1994). Socio‐economic causes and cultural explanations of childhood malnutrition among the Chagga of Tanzania. Social Science & Medicine, 38, 239–251. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90394-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M. T. , & Millard, A. V. (1997). Hunger and shame: Child malnutrition and poverty on Mount Kilimanjaro. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Howie, P. W. , Forsyth, J. S. , Ogston, S. A. , Clark, A. , & Du Florey, V. C. (1990). Protective effect of breat feeding against infection. British Medical Journal, 300, 11–16. 10.1136/bmj.300.6716.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliyasu, Z. , Kabir, M. , Galadanci, H. S. , Abubakar, I. S. , Salihu, H. M. , & Aliyu, M. H. (2006). Postpartum beliefs and practices in Danbare village, Northern Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 26, 211–215. 10.1080/01443610500508345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRossa, R. , Harkness, S. , & Super, C. M. (1997). Parents' cultural belief systems: Their origins, expressions, and consequences. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 233 10.2307/353675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mabilia, M. (2000). The cultural context of childhood diarrhoea among Gogo infants. Anthropology & Medicine, 7, 191–208. 10.1080/713650590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mabilia, M. (2005). Breast feeding and sexuality: Behaviour, beliefs and taboos among the Gogo mothers in Tanzania In Breast Feeding and Sexuality: Behaviour, Beliefs and Taboos among the Gogo Mothers in Tanzania. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, H. F. (2012). The directive force of morality tales in a Mexican community In Human motives and cultural models. 10.1017/cbo9781139166515.007 [Google Scholar]

- Mbekenga, C. K. , Christensson, K. , Lugina, H. I. , & Olsson, P. (2011). Joy, struggle and support: Postpartum experiences of first‐time mothers in a Tanzanian suburb. Women and Birth, 24, 24–31. 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbekenga, C. K. , Lugina, H. I. , Christensson, K. , & Olsson, P. (2011). Postpartum experiences of first‐time fathers in a Tanzanian suburb: A qualitative interview study. Midwifery, 27, 174–180. 10.1016/j.midw.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbekenga, C. K. , Pembe, A. B. , Darj, E. , Christensson, K. , & Olsson, P. (2013). Prolonged sexual abstinence after childbirth: Gendered norms and perceived family health risks. Focus Group Discussions in a Tanzanian Suburb. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 13 10.1186/1472-698X-13-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mchome, Z. , Bailey, A. , Darak, S. , & Haisma, H. (2019). “A child may be tall but stunted.” Meanings attached to childhood height in Tanzania. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(3), e12769 10.1111/mcn.12769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metta, E. , Bailey, A. , Kessy, F. , Geubbels, E. , Hutter, I. , & Haisma, H. (2015). “In a situation of rescuing life”: Meanings given to diabetes symptoms and care‐seeking practices among adults in Southeastern Tanzania: A qualitative inquiry. BMC Public Health, 15, 224 10.1186/s12889-015-1504-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MoHCDGEC . (2016). Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS‐MIS) 2015‐16. In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland USA. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [DOI]

- Muela, S. H. , Ribera, J. M. , & Tanner, M. (1998). Fake malaria and hidden parasites—The ambiguity of malaria. Anthropology & Medicine, 5, 43–61. 10.1080/13648470.1998.9964548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mull, D. S. (1991). Traditional perceptions of marasmus in Pakistan. Social Science & Medicine, 32, 175–191. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90058-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munblit, D. , Treneva, M. , Peroni, D. G. , Colicino, S. , Chow, L. Y. , Dissanayeke, S. , … Warner, J. O. (2016). Colostrum and mature human milk of women from London, Moscow, and Verona: Determinants of immune composition. Nutrients, 8, 695 10.3390/nu8110695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, D. , Chambers, R. , Shah, M. K. , & Petesch, P. (2000). Voices of the poor: Crying out for change (vol 2). USA: OUP; In Bank New York [Google Scholar]

- Nayar, U. S. , Stangl, A. L. , De Zalduondo, B. , & Brady, L. M. (2014). Reducing stigma and discrimination to improve child health and survival in low‐and middle‐income countries: Promising approaches and implications for future research. Journal of Health Communication, 19, 142–163. 10.1080/10810730.2014.930213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntukula, M. (2004). In Ntukula M. (Ed.), Custodians of Custom. Umleavyo: The Dilemma of Parenting (L. R. Edited by. Uppsala, Sweden: The Nordic Africa Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Picciano, M. F. (2001). Nutrient composition of human milk. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 48, 53–67. 10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70285-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popenoe, R. (2012). Feeding desire: Fatness, beauty, and sexuality among a saharan people In Feeding Desire: Fatness, Beauty, and Sexuality among a Saharan People. [Google Scholar]

- Reyles, D. Z. (2007). The ability to go about without shame: A proposal for internationally comparable indicators of shame and humiliation. Oxford Development Studies, 35, 405–430. 10.1080/13600810701701905 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, P. (1969). Cattle and kinship among the Gogo. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riordan, J. , & Wambach, K. (2010). Breastfeeding and human lactation. (Jones & Bartlett Learning).

- Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, attitudes, and values: A theory of organization and change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Sen (1993). Capability and well‐being In Sen A. K. & Nussbaum M. (Eds.), The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon Press; DOI: 10.1093/0198287976.003.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shabangu, Z. , & Madiba, S. (2019). The role of culture in maintaining post‐partum sexual abstinence of Swazi women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 10.3390/ijerph16142590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, C. , & Quinn, N. (1997). Meeting AAA In A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J. P. , & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and Guilt (xvi). New York, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund . (2018). Breastfeeding: A Mother's Gift, for Every Child. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/UNICEF_Breastfeeding_A_Mothers_Gift_for_Every_Child.pdf

- United Nations General Assembly . (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. New York. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly . (1993). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. NewYork. [Google Scholar]

- Vennemann, M. M. , Bajanowski, T. , Brinkmann, B. , Jorch, G. , Yücesan, K. , Sauerland, C. , & Mitchell, E. A. (2009). Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics, 123, e406–e410. 10.1542/peds.2008-2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. D. , França, G. V. A. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Richter, L. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet., 387, 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2019). Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infants. Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.who.int/elena/titles/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/ (Accessed June 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item

Supporting item