Abstract

Background

It has been demonstrated that simultaneous resection of both primary colorectal lesion and metastatic hepatic lesion is a safe approach with low mortality and postoperative complication rates. However, there are some controversies over which kind of surgical approach is better. The aim of study was to compare the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic surgeries and open surgeries for simultaneous resection of colorectal cancer (CRC) and synchronous colorectal liver metastasis (SCRLM).

Methods

A systemic search of online database including PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Embase was performed until June 5, 2019. Intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, and long-term outcomes were synthesized by using STATA, version 15.0. Cumulative and single-arm meta-analyses were also conducted.

Results

It contained twelve studies with 616 patients (273 vs 343, laparoscopic surgery group and open surgery group, respectively) and manifested latest surgical results for the treatment of CRC and SCRLM. Among patients who underwent laparoscopic surgeries, they had lower rates of postoperative complications (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.96, P = 0.028), less intraoperative blood loss (weight mean difference (WMD) = − 113.31, 95% CI: − 189.03 to − 37.59, P = 0.003), less time in the hospital and recovering after surgeries (WMD = − 2.70, 95% CI: − 3.99 to − 1.40, P = 0.000; WMD = − 3.20, 95% CI: − 5.06 to − 1.34, P = 0.001), but more operating time (WMD = 36.57, 95% CI: 7.80 to 65.35, P = 0.013). Additionally, there were no statistical significance between two kinds of surgical approaches in disease-free survival and overall survival. Moreover, cumulative meta-analysis indicated statistical difference in favor of laparoscopic surgery in terms of morbidity was firstly detected in the 12th study in 2018 (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.96, P = 0.028) as the 95% CI narrowed.

Conclusion

Compared with open surgeries, laparoscopic surgeries are safer (postoperative complications and intraoperative blood loss) and more effective (length of hospital stay and postoperative stay), and it can be considered as the first option for management of SCRLM in high-volume laparoscopic centers.

Trial registration

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Synchronous liver metastasis, Laparoscopy, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a common and lethal disease. Globally, CRC is the third most common cancer in males and second in females, with 1.8 million new cases and almost 861,000 deaths in 2018 according to the World Health Organization GLOBOCAN database. In the USA, annually, approximately 145,600 new cases of large bowel cancer are diagnosed, of which 101,420 are colon and the remainder are rectal cancers [1, 2]. Although CRC mortality has been progressively declining since 1990, currently, 1.7 to 1.9% per year [1], it is still the third leading cause of cancer death in the USA in women and the second common cause of cancer death in men [3, 4]. More importantly, CRC is an extraordinary progressive cancer, and many patients have metastatic lesions at the time of initial diagnosis. Liver is the primary metastatic site for patients with CRC and 15–20% of those patients presenting with synchronous colorectal liver metastases (SCRLM) [5]. These can be resected in one operation or as staged approach, depending on the complexity of the hepatectomy and colectomy, comorbid diseases, and surgeon expertise [6, 7]. The classic approach to SCRLM is to resect the primary lesion, followed by chemotherapy, and subsequent hepatic resection is offered. However, recent studies have demonstrated that simultaneous resection of both primary colorectal lesion and metastatic hepatic lesion is a safe approach with low mortality and postoperative complication rates [8, 9]. Moreover, there are two kinds of surgical approaches to complete simultaneous resection, laparoscopic approach and open approach, respectively [10]. Despite the fact that some studies indicated laparoscopic surgeries had less operating time, intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative pain, most of the studies fail to demonstrate the superiority of laparoscopic surgeries [11]. Moreover, in that case, the outcomes of laparoscopic surgeries associated with current technology and proficiency of surgeons, we believe, will be different from previous studies after several years. Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to compare those two kinds of surgical approaches regarding intraoperative and postoperative complications and long-term outcomes on account of the current available literature.

Methods

Literature search and selection

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [12]. The protocol for the meta-analysis is registered at PROSPERO (CRD42020151176).

We performed a systemic search of online database including PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Embase to identify relevant studies about comparing open surgeries with laparoscopic surgeries for simultaneous resections of CRC and SCRLM until June 5, 2019. The search strategy was performed using the following terms: colorectal cancer, colorectal cancer liver metastases, synchronous, simultaneous, minimally invasive, laparoscopy, hepatectomy, laparotomy, and open. The detailed search strategy is shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. The references associated with those relevant reviews and meta-analyses were also searched to identify possible additional studies.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: study population (patients with proven or suspected SCRLM (liver metastasis was detected at the same time as detection of CRC)), intervention (laparoscopic vs open surgeries for simultaneous resections), study design (randomized controlled studies or observational studies including cohort and case–control studies), outcome measuring (studies reported at least 1 outcome of the perioperative results or long-term outcomes), the study population which included more than 20 patients (smaller studies were excluded for poor credibility), and studies published as full-length articles.

Some studies were excluded based on the following criteria: abstracts from conferences, case reports, non-comparative studies, review articles, and meta-analyses, and commentary articles were excluded. The study did not clearly distinguish between synchronous liver metastases and metachronous liver metastases. The study failed to distinguish between synchronous resection and staged resection, i.e., hepatectomy only.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were evaluated and extracted by 2 investigators independently (LP and CHT). All the important information were recorded in a Microsoft excel database, such as baseline details, postoperative complications, intraoperative complications (blood loss and operating time), and long-term outcomes (mortality, overall survival rate, and length of hospital stay and postoperative stay). In terms of postoperative complications, they are graded on the Clavien-Dindo Classification, and grade ≥ 3 represents severe complications requiring surgical intervention, the use of organ support, and fatality [13].

Regarding quality assessment of included studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) were used to evaluate the quality of those twelve studies [14]. The results of quality assessment of included studies are displayed in Additional file 1: Table S2. Disagreements were solved by mutual consensus.

Statistical analysis

For dichotomous outcomes and continuous outcomes, we used the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and weight mean difference (WMD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs to evaluate, respectively. Single-arm meta-analyses and cumulative meta-analyses were conducted for evaluating the postoperative complications between laparoscopic surgery and open surgery groups. Heterogeneities among studies were tested using Cochran Chi-square test and I2, in which I2 ≥ 50% suggested significant heterogeneity. A random effects model was used to pool the results when I2 ≥ 50%, while a fixed effects model was used when low heterogeneity (I2 < 50%). We also used the Funnel plots, Harbord tests, Peters tests, and Egger tests to detect any publication bias. Harbord tests and Peters tests were used to evaluate the binary data; on the other hand, enumeration variables were processed by Egger tests. P < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance (2-sided). All the statistical analyses were conducted by using STATA, version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Study selection and quality assessment

Based on the previous search strategy, there were 648 studies after searching from the online databases. Moreover, searching the reference lists and relevant reviews also included fifteen additional publications. Four hundred eleven records remained in all after eliminating duplicates. Next, by means of reading the titles and abstracts, we excluded 366 studies, and there were 45 records to read thoroughly to evaluate the eligibility. Among those 45 records, 33 articles were excluded due to several reasons. The specific reasons of why 33 articles were excluded are displayed in Additional file 1: Table S3. Eventually, we included 12 studies into this meta-analysis [15–26] (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics and quality evaluation of the included studies are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

A flow diagram of the inclusion criteria of studies eligible for meta-analysis

Table 1.

Demographics and quality assessments of included studies

| Study, year | Country | Study period |

Study design |

Criteria | Matched factorsb | No. of participants (MH, %) | Age, Mean (SD), y | Female, No. (%) | Quality score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusiona | ||||||||||||

| Lap | Open | Lap | Open | Lap | Open | ||||||||

| Ma et al. [23], 2018 | China | 2014–2017 | PSM (R, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 1–3 | 1–3, 5, 7, 11, 12, 15–17, 21, 22,24–26 | 12 (25) | 12 (33) | 3c (25) | 1c (8) | 3 (25) | 4 (33) | 8 |

| Ivanecz et al [20], .2018 | Slovenia | 2000–2016 | PSM (P, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 4–6 | 1–3, 5, 7, 10–12, 15, 20–27 | 10 (0) | 10 (0) | 62 (8) | 65 (8) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 8 |

| Xu et al. [26], 2017 | China | 2009–2014 | PSM (R, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 5, 7 | 1–3, 5–7, 9, 10, 12, 15–17, 20–22,24– 26, 28 | 20 (25) | 20 (20) | 58 (11) | 60 (11) | 7 (35) | 6 (30) | 8 |

| Chen et al [16], .2018 | Taiwan, China | 2009–2017 | NM (R, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 2, 6, 8–11 | 1, 2, 7, 11–13, 15, 17, 20, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29 | 16 (19) | 22 (14) | 66 (10) | 65 (13) | 6 (38) | 13 (59) | 6 |

| Gorgun et al [17], .2017 | USA | 2006–2015 | NM (P, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | NR | 1, 2, 3, 7, 9–12, 15, 16, 18, 21, 22,24– 26, 28, 29 | 14 (14) | 29 (14) | 56 (3) | 58 (3) | 8 (57) | 13 (45) | 6 |

| Ratti et al [24], .2016 | Italy | 2004–2015 | PSM (P, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 4, 12, 13 | 1–3, 5, 10, 12, 16– 18, 20–22, 24–26, 28, 29 | 25 (24) | 50 (20) | 60 (11) | 61 (10) | 11 (44) | 23 (46) | 8 |

| Tranchart et al [25], .2016 | France | 1997–2013 | PSM (R, M) | Liver lesions ≤ 5 cm with segments II– VI | 14 | 1, 2, 7, 10–12, 14, 16, 20, 21,24–26, 28,29 | 89 (8) | 89 (6) | 67 (11) | 65 (9) | 47 (53) | 49 (55) | 8 |

| Lin et al [22], .2015 | China | 2008–2012 | PSM (P, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 15–18 | 1–3, 5, 7–16, 20, 21, 24–26, 28 | 7 (0) | 36 (17) | 60 (3) | 57 (10) | 2 (29) | 15 (58) | 8 |

| Jung et al [21], .2013 | Korea | 2008–2012 | CM (P, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | 5, 19 | 1, 2, 7, 9–12, 16, 19– 21, 24, 25, 27, 28 | 24 (25) | 24 (25) | 60 (43–75) | 60 (37–80) | 11 (46) | 7 (29) | 6 |

| Hu et al. [18], 2012 | China | 2004–2008 | CM (R, M) | Metastasis restricted to the left lobe or a segment in the right lobe with size < 6 cm | 6, 20, 21, 22 | 1, 2, 7, 8, 10, 11, 15, 17–19, 28 | 13 (15) | 13 (15) | 54 (10) | 53 (11) | 3 (23) | 4 (31) | 8 |

| Huh et al [19], .2011 | Korea | 2003–2008 | CM (P, S) | Primary CRC and SCRLM | NR | 1–3, 5, 7, 9–16, 25, 28 | 20d (NR) | 20 (NR) | 63 (36– 71) | 62 (44–85) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) | 8 |

| Chen et al [15], .2011 | China | 1999–2005 | CM (R, S) | Rectal tumor fit for Dixon’s surgery and the number of liver lesions ≤ 2 | 21, 23, 24 | 1–10, 13–16 | 23 (26) | 18 (NR) | 55 (10) | 53 (9) | 5 (22) | 4 (22) | 8 |

CRC Colorectal cancer, SCRLM Synchronous liver metastases, CM Case-matched, PSM Propensity score matching, MH Major hepatectomy (≥ 3 segments), P prospectively collected data, R retrospectively collected data, M multicenters, S single center, NR not report

aExclusion criteria are defined as follows: (1) loss to follow-up; (2) with other malignant tumors; (3) combined multiple organ resection;(4) two stage approaches (colorectal first or liver first; (5) combined radiofrequency ablation; (6) extrahepatic metastases; (7) the application of mixed approaches, initially unresectable SCRLM; (8) with hepatic cellular cancer; (9) with neuroendocrine tumor; (10) with benign liver tumor; (11) with peritoneum seeding; (12) mixed approach (laparoscopic colorectal resection and open hepatectomy or vice versa); (13) follow-up< 12 months; (14) tumors close to the portal pedicle or hepatic veins; (15) incomplete material; (16) with obstructive colorectal cancer; (17) with cancer perforation; (18) with T4 colorectal cancer; (19) minor procedures performed by colorectal surgeon only(liver biopsy or wedge resection of synchronous liver metastases in the liver edge); (20) liver metastasis located in the right hemiliver at a size of > 6cm or requiring the resection of > 2 segments; (21) with a previous history of abdominal surgery or tuberculous peritonitis; (22) with serious cardiopulmonary insufficiency; (23)the rectal tumor fit for Mile’s surgery; (24) the number of liver lesions ≥ 3

bMatched factors means the covariate was matched or the difference of the covariate was not statistically significant between two groups and are defined as follows: (1) age; (2) sex; (3) carcinoembryonic antigen; (4) distance between rectal tumors and anus; (5) tumor differentiation; (6) child class; (7) liver metastases size; (8) location of liver metastases (segments 1, 2 ,3, 4b, 4a, 5 ,6, 7, 8); (9) primary tumor size; (10) location of primary tumor (colon/rectum); (11) body mass index; (12) American Society of Anesthesiologists; (13) lymphovascular invasion; (14) depth of primary tumor invasion; (15) postoperative chemotherapy; (16) distribution of metastases (unilobar/bilobar); (17) primary tumor stage; (18) comorbid disease; (19) previous abdomen surgery; (20) types of colorectal and hepatic surgery; (21) number of liver metastases; (22) preoperative chemotherapy; (23) location of liver metastases (anterolateral/posterosuperior); (24) primary tumor T stage; (25) primary nodal status; (26) neoadjuvant chemotherapy; (27) harvested lymph nodes; (28) the type of hepatoenterectomy; (29) recurrence

cThe number (%) of patients > 60 years

dSeven of the 20 patients underwent a total one-step laparoscopic procedure while 13 patients underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection and open liver resection

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics of included studies

| Study | Intervention | Location of primary tumor (colon/rectum) | Primary tumor size, mean (SD), cm |

No. of CRLM, mean (SD) | CRLM location (unilober/bilobar) |

CRLM size | R0 rate (liver/colorectum) |

Neoadjuvant therapy | Mortality | Conversions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma et al. [23] | Lap | 7/5 | NR | 1.6 (0.9) | 7/5 | 3.73 ± 2.91 | 100/100 | 3 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 7/5 | NR | 3.1 (1.8) | 5/2 | 3.02 ± 1.62 | 100/100 | 3 (25) | 0 | ||

| Ivanecz et al. [20] | Lap | 4/6 | NR | 1.4 (0.9) | 9/1 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 100/100 | 7 (70) | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 6/4 | NR | 1.4 (0.9) | 9/1 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 100/100 | 3 (30) | 0 | ||

| Xu et al. [26] | Lap | 15/5 | 3.2 (1.0) | 6a | 18/2 | 2.99 ± 1.55 | 100/100 | 6 (30) | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 15/5 | 3.8 (1.2) | 6 | 17/3 | 3.19 ± 1.53 | 100/100 | 4 (20) | 0 | ||

| Chen et al [16]. | Lap | NR/NR | 4.0 (2.0) | 4a | NR | 5.5 ± 4.2 | NR/NR | NR | 0 | 1 |

| Open | NR/NR | 5.0 (3.0) | 3 | NR | 4.7 ± 3.7 | NR/NR | NR | 0 | ||

| Gorgun et al. [17] | Lap | 6/8 | 3.7 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.3) | 12/2 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 86/NR | 6 (43) | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 14/15 | 3.7 (0.5) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 19/10 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 93/NR | 19 (66) | 1 | ||

| Ratti et al [24]. | Lap | 13/12 | NR | 2.40 ± 1.27 | 13/12 | 3.65 ± 2.67 | 96/100 | 20 (80) | 0 | 1 |

| Open | 27/23 | NR | 2.35 ± 1.34 | 27/23 | 3.94 ± 2.47 | 98/98 | 39 (78) | 0 | ||

| Tranchart et al. [25] | Lap | 48/41 | NR | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 78/11 | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 83/NR | 11 (12) | 2 | 6 |

| Open | 51/38 | NR | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 81/8 | 2.8 ± 2.0 | 90/NR | 20 (22) | 0 | ||

| Lin et al [22]. | Lap | 3/4 | 5.3 (1.1) | 1.9 ± 0.9 | NR | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 100/NR | 3 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 19/17 | 5.7 (1.9) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | NR | 4.2 ± 2.2 | 100/NR | 13 (36) | 0 | ||

| Jung et al [21]. | Lap | 18/6 | 5.23 (2.13) | NR | 23/1 | 2.81 ± 1.72 | 100/96 | NR | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 16/8 | 5.56 (1.93) | NR | 18/6 | 3.23 ± 2.21 | 100/100 | NR | 0 | ||

| Hu et al [18]. | Lap | 8/5 | NR | NR | NR | 3.2 ± 1.0 | NR/NR | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 8/5 | NR | NR | NR | 3.5 ± 0.9 | NR/NR | 0 (0) | 0 | ||

| Huh et al [19]. | Lap | 7/13 | 4 (2–10) | 2 (1–7) | 17/3 | 2 (0.9–5.5) | 100/NR | NR | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 11/9 | 4.7 (3–7) | 2 (1–8) | 16/4 | 2.4 (1–10) | 100/NR | NR | 0 | ||

| Chen et al [15]. | Lap | 0/23 | 2.5 (0.9) | NR | NR | 5.5 ± 1.2 | NR/NR | NR | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 0/18 | 2.3 (1.0) | NR | NR | 5.6 ± 1.4 | NR/NR | NR | 0 |

Lap Laparoscopic surgery, NR Not report

aThe number of patients with CRLM ≥ 3

Intraoperative outcomes

All the included studies reported the intraoperative blood loss and operating time. Patients who received laparoscopic surgeries had less intraoperative blood loss according to the results (WMD = − 113.31, 95% CI: − 189.03 to − 37.59, P = 0.003). This meta-analysis also indicates that the operating time surgeons spent on patients who underwent laparoscopic surgeries were much longer (WMD = 36.57, 95% CI: 7.80 to 65.35, P = 0.013). Detailed results of intraoperative outcomes were displayed in the Table 3 and Additional Figure S1.

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes in this meta-analysis

| Outcome of interest | No. of studies | WMD/OR | 95% CIs | P value | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time | 12 | 36.57 | 7.80 to 65.35 | 0.013 | 82.4 |

| Blood loss | 12 | − 113.31 | − 189.03 to − 37.59 | 0.003 | 91.4 |

| Hospital stay | 7 | − 2.70 | − 3.99 to − 1.40 | < 0.001 | 53.6 |

| Postoperative stay | 4 | − 3.20 | − 5.06 to − 1.34 | 0.001 | 55.2 |

| 1-year DFS | 4 | 1.05 | 0.59 to 1.86 | 0.86 | 0 |

| 3-year DFS | 4 | 0.66 | 0.41 to 1.08 | 0.097 | 7.5 |

| 1-year OS | 5 | 0.56 | 0.23 to 1.33 | 0.187 | 0 |

| 3-year OS | 6 | 0.94 | 0.53 to 1.65 | 0.822 | 0 |

| 5-year OS | 3 | 0.69 | 0.29 to 1.68 | 0.417 | 0 |

DFS Disease-free survival, OS Overall survival

Postoperative complications

The postoperative complications rate between laparoscopic surgeries and open surgeries was 0.208 (95% CI: 0.161 to 0.254) and 0.325 (95% CI: 0.275 to 0.375), respectively. This meta-analysis suggested that the postoperative complications were significantly lower among patients who underwent laparoscopic surgeries (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.96, P = 0.028) (Fig. 2a), without heterogeneity (I2 = 3.1%, P = 0.414). When it comes to the laparoscopic surgery, we assume that the results may be associated with current technology and proficiency of general surgeons. Hence, we did a cumulative meta-analysis, and it indicated statistical difference in favor of the laparoscopic surgery which was firstly detected in the 12th study in 2018 (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.96, P = 0.028) as the 95% CI narrowed (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis for primary outcomes. a Forest plot of meta-analysis in postoperative complications. b Cumulative meta-analysis of postoperative complications

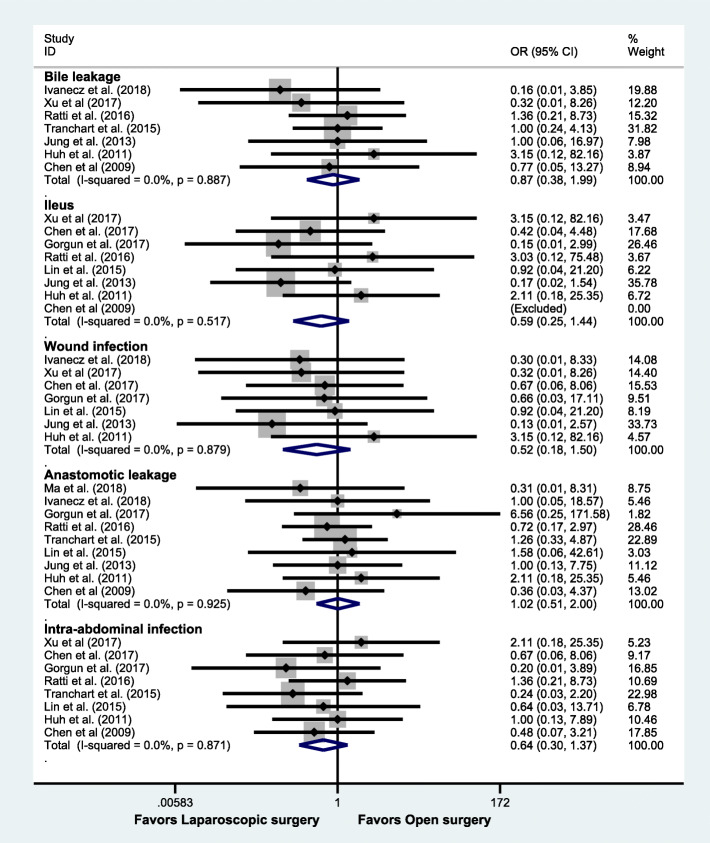

Subsequently, we did subgroup analyses according to the type of morbidity. Although there was no statistical significance in each subgroup (bile leakage: OR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.38 to 1.99, P = 0.74; ileus: OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.25 to 1.44, P = 0.248; wound infection: OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.18 to 1.50, P = 0.224; anastomotic leakage: OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.51 to 2.00, P = 0.965; intra-abdominal infection: OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.30 to 1.37, P = 0.250), the tendencies in the ileus, wound infection, and intra-abdominal infection were in favor of laparoscopic surgery (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis based on the types of morbidity

Additionally, these outcomes were also divided into 2 subgroups based on their study types (Propensity vs Non-propensity). Despite the fact that there was no statistical significance on postoperative complications in the Propensity group (OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.51 to 1.30, P = 0.388), the result in the Non-propensity group showed that those patients with laparoscopic surgeries were less likely to develop postoperative complications (OR = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.27 to 0.88, P = 0.016). However, the outcomes in each subgroup still showed consistency, compared with the overall outcomes. When we subdivided postoperative complications to 2 groups based on the Clavien classification, both grade ≥ III complications and grade < III complications showed no statistical significance between 2 kinds of surgeries (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.71, P = 0.835; OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.41 to 1.16, P = 0.159, respectively). Detailed results of subgroup analyses were displayed in the Additional Figure S1.

Other outcomes

Based on those twelve studies, this meta-analysis suggested that there was no statistical significance between laparoscopic surgery and open surgery in disease-free survival (1 year: OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.59 to 1.86, P = 0.86; 3 years: OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.41 to 1.08, P = 0.097) and overall survival (1 year: OR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.23 to 1.33, P = 0.187; 3 years: OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.53 to 1.65, P = 0.822; 5 years: OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.29 to 1.68, P = 0.417). Regarding to length of hospital stay and postoperative stay, the results indicated that patients who had laparoscopic surgeries spent less time in the hospital and recovering after surgeries (WMD = − 2.70, 95% CI: − 3.99 to − 1.40, P = 0.000; WMD = − 3.20, 95% CI: − 5.06 to − 1.34, P = 0.001). Detailed results of other outcomes were displayed in Table 3 and Additional file Figure S1.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

In consideration of the influence of adjuvant chemotherapy on the overall survival and disease-free survival, the administration of postoperative chemotherapy was comparable between the laparoscopic and open groups in nine studies, while the remaining three studies [21, 24, 25] did not report the details about postoperative chemotherapy. Therefore, we did a sensitivity analysis by removing those three studies, and the results were consistent with original outcomes (overall survival: 1 year, 0.54 (95% CI 0.16–1.59; 5 years, 0.66 (95% CI 0.16–2.69); disease-free survival: 1 year, 1.31 (95% CI 0.50–3.41); 3 years, 0.80 (95% CI 0.34–1.86)). Besides, general sensitivity analyses by omitting each study have confirmed this meta-analysis has good stability and strong robustness. Funnel plots of all those results showed a symmetric distribution. Harbord, Peters, and Egger tests were used to demonstrate that there was no publication bias among those studies of primary outcomes. Specifically, the funnel plot of postoperative complications is symmetric and none of the included studies was outside the 95% CI (Harbord test P = 0.524; Peter’s test P = 0.155). Detailed results of sensitivity analysis and publication bias are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2 and S3.

Discussion

This meta-analysis included studies from 2009 to 2018 to compare the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic surgeries and open surgeries in patients with CRC and SCRLM. It includes twelve studies with 616 patients (273 vs 343) and manifests latest surgical results for the treatment of CRC and SCRLM. All included studies were of relatively high quality, and the heterogeneity among primary outcomes was very low. Besides, sensitivity analyses indicated that the results were not affected by any individual study.

Recently, there is a meta-analysis about this issue published in June 2019 by Ye et al. [27]. Their study showed that the laparoscopic surgery group had less intraoperative blood loss and blood transfusions and quicker postoperative recovery. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in postoperative complications. Compared with their meta-analysis, our study has a positive result over the rate of overall postoperative complications. We found the fact that this presenting meta-analysis included 3 more studies, Xu et al. [26], Jung et al. [21], and Huh et al.’s [19] and excluded one of their studies, Takasu et al.’s [28], due to the small size of samples (7 vs 7). This meta-analysis indicated that postoperative complications were significantly less among patients who underwent laparoscopic surgeries (P = 0.028). Since the fact that laparoscopic surgery is a relatively newly developed surgical approach compared with laparotomy, and requires special equipment and skilled general surgeons who must have rich experience, the outcomes can be influenced by the time and the quality of medical care of each included study. Therefore, we conducted a cumulative meta-analysis to confirm our point. It indicated that statistical difference in favor of laparoscopic surgery was firstly detected in the 12th study in 2018 (the latest one) as the 95% CI narrowed. This result illustrated the reason why prior systemic reviews and meta-analyses did not have statistical significance of this variable. Then, in order to further explore the differences in different types of complications between laparoscopic procedure and open procedure, a subgroup meta-analysis was performed. We found that laparoscopic procedure can reduce ileus, wound infection, and intra-abdominal infection compared with open approach to a certain degree, although they did not reach statistical differences, which may provide useful value for clinical practice. We also conducted another subgroup analysis based on their study types (Propensity vs Non-propensity). Even though in the Propensity subgroup, there was no statistical significance (P = 0.388), it still showed consistency, compared with the overall outcomes. The result in the Non-propensity group showed that those patients with laparoscopic surgery were less likely to develop postoperative complications (P = 0.016). Besides, a randomized controlled trial is ongoing comparing robotic versus open surgery for simultaneous resection of CRC and CRLM (NCT02642978), and the mid-term outcomes (58 vs 57) indicated lower liver-related complication morbidity (10.3% vs 28.1%, P = 0.016) was observed in robotic group [29]. Hence, we believe that as more studies are included, the effect sizes will be stable, and 95% CI will become narrower.

We also analyzed the intraoperative outcomes, specifically intraoperative blood loss. As we expected, patients receiving laparoscopic surgeries had less intraoperative blood loss (P = 0.003). This result is quite convincing due to the fact that laparoscopic surgery is a less invasive intervention than laparotomy, and it has smaller incisions, less blood transfusions, and fewer chances to cause additional injuries. Subsequently, due to less intraoperative and postoperative complications, when it comes to the length of hospital stay and postoperative stay, patients with laparoscopic surgeries spent less time in the hospital and recovering after surgeries (P = 0.000; P = 0.001). Another important factor that should be considered is long-term outcomes. This meta-analysis suggested that the results were similar between laparoscopic surgeries and open surgeries in disease-free survival and overall survival. This result also demonstrated that the approaches of surgeries only affected intraoperative and postoperative complications but not long-term outcomes.

Certain limitations presenting in this meta-analysis have an impact on the outcomes. Firstly, none of the included studies were randomized controlled trials and the number of included studies was not large enough, which will both definitely increase selection and procedure bias. Secondly, one of the most important limitations is heterogeneity, and several situations may cause this. There are twelve different studies included and 616 patients with different conditions are treated by different surgeons with various experience. Even though all patients had SCRLM, their oncological conditions, different locations of liver metastasis, and underlying diseases may affect the outcomes. Although the primary outcomes showed low heterogeneity, other outcomes such as intraoperative bleeding, operating time, and postoperative and hospital stay demonstrated high heterogeneities.

Conclusion

Compared with open surgeries, laparoscopic surgeries are safer (postoperative complications and intraoperative blood loss) and more effective (length of hospital stay and postoperative stay). These findings suggest that laparoscopic surgeries should be considered the first option for the management of SCRLM, especially when confronted with eligible cases.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Forest plot of meta-analysis. (A) Blood loss. (B) Operating time. (C) Subgroup analysis of postoperative complications. (D) Clavien grade<III complications. (E) Clavien grade ≥III complications. (F) Hospital stay. (G) Postoperative stay. (H) One-year overall survival rate. (I) Three-year overall survival rate. (J) Five-year overall survival rate. Figure S2. Sensitivity of all the outcomes. (A) Blood loss. (B) Operating time. (C) Postoperative complications. (D) Clavien grade<III complications. (E) Clavien grade ≥III complications. (F) Hospital stay. (G) Postoperative stay. (H) One-year overall survival rate. (I) Three-year overall survival rate. (J) Five-year overall survival rate. Figure S3. Publication bias of all the outcomes. (A)-(J) Funnel plot of Blood loss, Operating time, Postoperative complications, Clavien grade<III complications, Clavien grade ≥III complications, Hospital stay, Postoperative stay, One-year overall survival rate, Three-year overall survival rate, Five-year overall survival rate. (K) Quantitative assessment for publication bias. Table S1. Search Strategy for Each Database. Table S2. Quality Assessment of Included Studies. Table S3. Excluded Articles and Reasons for Exclusion.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mintah Bright Darko for his linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal carcinoma

- SCRLM

Synchronous colorectal liver metastasis

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- OS

Overall survival

- ORs

Odds ratios

- CI

Confidence intervals

- WMD

Weight mean difference

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa scale

Authors’ contributions

LP, CT, and SF contributed equally to this work. XC and LP designed the study. CT and JF searched databases. SF and CT collected the data and performed the statistical analysis. LP and SF wrote the drafts. ZJ, SW, QG, and SJ revised the article critically. All the authors approved the final version to be submitted.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81772546) and the Key Research and Development Plan Projects of Zhejiang Province (No. 2017C01018).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Long Pan, Chenhao Tong and Siyuan Fu contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12957-020-02018-z.

References

- 1.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, Sherman RL, Noone AM, Howlader N, Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Firth AU, Ma J, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018;124:2785–2800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66:683–691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dendy MS, Ludwig JM, Kim HS. Predictors and prognosticators for survival with Yttrium-90 radioembolization therapy for unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:37912–37922. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moris D, Tsilimigras DI, Machairas N, Merath K, Cerullo M, Hasemaki N, Prodromidou A, Cloyd JM, Pawlik TM. Laparoscopic synchronous resection of colorectal cancer and liver metastases: a systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2018;119:30–39. doi: 10.1002/jso.25313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Cederquist L, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, et al. NCCN guidelines (R) insights colon cancer, version 2.2018 featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2018;16:359–369. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Cederquist L, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:874–901. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy SK, Pawlik TM, Zorzi D, Gleisner AL, Ribero D, Assumpcao L, Barbas AS, Abdalla EK, Choti MA, Vauthey J-N, et al. Simultaneous resections of colorectal cancer and synchronous liver metastases: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3481–3491. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9522-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings LC, Payes JD, Cooper GS. Survival after hepatic resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Cancer. 2007;109:718–726. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo Y, Gao Y, Chen G, Li C, Dong G. Minimally invasive versus open simultaneous resections of colorectal cancer and synchronous liver metastases: a meta-analysis. Am Surg. 2018;84:192–200. doi: 10.1177/000313481808400224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirnezami R, Mirnezami AH, Chandrakumaran K, Abu Hilal M, Pearce NW, Primrose JN, Sutcliffe RP. Short- and long-term outcomes after laparoscopic and open hepatic resection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hpb. 2011;13:295–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, Group P-P Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibanes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen KY, Xiang GA, Wang HN, Xiao FL. Simultaneous laparoscopic excision for rectal carcinoma and synchronous hepatic metastasis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124:2990–2992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YW, Huang MT, Chang TC. Long term outcomes of simultaneous laparoscopic versus open resection for colorectal cancer with synchronous liver metastases. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorgun E, Yazici P, Onder A, Benlice C, Yigitbas H, Kahramangil B, Tasci Y, Aksoy E, Aucejo F, Quintini C, et al. Laparoscopic versus open 1-stage resection of synchronous liver metastases and primary colorectal cancer. Gland Surg. 2017;6:324–329. doi: 10.21037/gs.2017.03.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu MG, Ou-Yang CG, Zhao GD, Xu DB, Liu R. Outcomes of open versus laparoscopic procedure for synchronous radical resection of liver metastatic colorectal cancer: a comparative study. Surg Laparoscopy Endoscopy Percutaneous Techniques. 2012;22:364–369. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31825af6b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huh JW, Koh YS, Kim HR, Cho CK, Kim YJ. Comparison of laparoscopic and open colorectal resections for patients undergoing simultaneous R0 resection for liver metastases. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:193–198. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanecz A, Krebs B, Stozer A, Jagric T, Plahuta I, Potrc S. Simultaneous pure laparoscopic resection of primary colorectal cancer and synchronous liver metastases: a single institution experience with propensity score matching analysis. Radiol Oncol. 2017;52:42–53. doi: 10.1515/raon-2017-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung KU, Kim HC, Cho YB, Kwon CHD, Yun SH, Heo JS, Lee WY, Chun HK. Outcomes of simultaneous laparoscopic colorectal and hepatic resection for patients with colorectal cancers: a comparative study. J Laparoendoscopic Adv Surg Techniques. 2014;24:229–235. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Q, Ye Q, Zhu D, Wei Y, Ren L, Zheng P, Xu P, Ye L, Lv M, Fan J, Xu J. Comparison of minimally invasive and open colorectal resections for patients undergoing simultaneous R0 resection for liver metastases: a propensity score analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:385–395. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma K, Wang XY, Chen JH. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for simultaneous resection of synchronous colorectal liver metastases. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;56:516–521. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratti F, Catena M, Di Palo S, Staudacher C, Aldrighetti L. Impact of totally laparoscopic combined management of colorectal cancer with synchronous hepatic metastases on severity of complications: a propensity-score-based analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4934–4945. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tranchart H, Fuks D, Vigano L, Ferretti S, Paye F, Wakabayashi G, Ferrero A, Gayet B, Dagher I. Laparoscopic simultaneous resection of colorectal primary tumor and liver metastases: a propensity score matching analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1853–1862. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu X, Guo Y, Chen G, Li C, Wang H, Dong G. Laparoscopic resections of colorectal cancer and synchronous liver metastases: a case controlled study. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2018;27:209–216. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2017.1378236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye SP, Qiu H, Liao SJ, Ai JH, Shi J. Mini-invasive vs open resection of colorectal cancer and liver metastases: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2819–2832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i22.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takasu C, Shimada M, Sato H, Miyatani T, Imura S, Morine Y, Ikemoto T, Kanamoto M, Kurita N, Eto S, Utsunomiya T. Benefits of simultaneous laparoscopic resection of primary colorectal cancer and liver metastases. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2014;7:31–37. doi: 10.1111/ases.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu JM, Wei Y, Wang XY, Fan H, Chang WJ, Ren L, Jiang W, Fan J, Qin XY. Robot-assisted one-stage resection of rectal cancer with liver and lung metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2848–2853. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Forest plot of meta-analysis. (A) Blood loss. (B) Operating time. (C) Subgroup analysis of postoperative complications. (D) Clavien grade<III complications. (E) Clavien grade ≥III complications. (F) Hospital stay. (G) Postoperative stay. (H) One-year overall survival rate. (I) Three-year overall survival rate. (J) Five-year overall survival rate. Figure S2. Sensitivity of all the outcomes. (A) Blood loss. (B) Operating time. (C) Postoperative complications. (D) Clavien grade<III complications. (E) Clavien grade ≥III complications. (F) Hospital stay. (G) Postoperative stay. (H) One-year overall survival rate. (I) Three-year overall survival rate. (J) Five-year overall survival rate. Figure S3. Publication bias of all the outcomes. (A)-(J) Funnel plot of Blood loss, Operating time, Postoperative complications, Clavien grade<III complications, Clavien grade ≥III complications, Hospital stay, Postoperative stay, One-year overall survival rate, Three-year overall survival rate, Five-year overall survival rate. (K) Quantitative assessment for publication bias. Table S1. Search Strategy for Each Database. Table S2. Quality Assessment of Included Studies. Table S3. Excluded Articles and Reasons for Exclusion.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.