Abstract

Background:

The OPUS study demonstrated that addition of cetuximab to 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) significantly improved objective response and progression-free survival (PFS) in the first-line treatment of patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). In patients with KRAS exon 2 mutations, a detrimental effect was seen upon addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4. The current study reports outcomes in subgroups defined by extended RAS testing.

Patients and methods:

Samples from OPUS study KRAS exon 2 wild-type tumours were reanalysed for other RAS mutations in four additional KRAS codons (exons 3–4) and six NRAS codons (exons 2–4) using BEAMing. A cutoff of ⩾ 5% mutant/wild-type sequences was selected to define RAS status; we also report an analysis using a cutoff based on the technical lower limit for mutation identification (0.1%).

Results:

Other RAS mutations were detected in 31/118 (26%) evaluable patients. In the extended analysis of RAS wild-type tumours (n = 87), objective response was significantly improved by addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4 (58% versus 29%; odds ratio 3.33 [95% confidence interval 1.36–8.17]; P = 0.0084); although limited by population size, there also appeared to be trends favouring the cetuximab arm in terms of PFS and overall survival in the RAS wild-type group compared with the RAS evaluable group. There was no evidence that patients with other RAS mutations benefited from cetuximab, but small numbers precluded precise estimations of treatment effects. In the combined population of patients with any RAS mutation (KRAS exon 2 or other RAS), a clear detrimental effect was associated with addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4.

Conclusion:

Patients with RAS-mutant mCRC, as defined by mutations in KRAS and NRAS exons 2–4, derive no benefit and may be harmed by the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4. Restricting cetuximab administration to patients with RAS wild-type tumours will further tailor therapy to maximise benefit.

Keywords: Cetuximab, FOLFOX4, KRAS, NRAS, OPUS, RAS

1. Introduction

The randomised phase II OPUS study demonstrated that objective response rate (the primary end-point) and progression-free survival (PFS) time were significantly improved upon the addition of cetuximab to 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) in patients with KRAS codon 12 and 13 (hereinafter exon 2) wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Patients with KRAS exon 2 tumour mutations showed no such benefit, with worse outcome in patients in the FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab arm compared with the FOLFOX4 alone arm [1,2]. Analogous conclusions were reached for another epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody (panitumumab) in the phase III PRIME study, including the observation of a detrimental effect when panitumumab was combined with FOLFOX4 in patients with KRAS exon 2 mutations [3].

Activating missense mutations of KRAS at particular codons other than 12 and 13 have been documented in a variety of tumour types, including colorectal cancer [4,5]. A similar spectrum of mutations has also been reported in the NRAS gene. A retrospective analysis exploring the rate and impact of other activating RAS mutations on treatment outcomes in the PRIME study indicated that 17% of patients previously determined to be wild-type for KRAS exon 2 had mutations at other RAS locus (KRAS codon 61, 117, 146; NRAS codons 12, 13, 61). These other RAS mutations were associated with detrimental outcome in patients treated with FOLFOX4 plus panitumumab [6]. An exploratory analysis further implicated mutations in RAS codon 59 as negative biomarkers in relation to the efficacy of FOLFOX4 plus panitumumab.

The primary objective of this post hoc investigation was to evaluate the treatment effect of FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab compared with FOLFOX4 alone in patients with tumours carrying mutations at RAS loci other than KRAS codon 12 or 13 (other RAS mutations). The treatment effect in patients with tumours wild-type at all RAS loci was also investigated. Outcome in patients wild-type for both RAS and BRAF (V600E; as previously defined [2]) was also considered. In line with prior clinical studies [6,12–15], a 5% cutoff was selected for defining mutant versus wild-type tumours, although we also report the results of an analysis conducted using a cutoff based on the technical lower limit for mutation identification (0.1%).

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design

The design of the randomised phase II OPUS study comparing 14-day cycles of FOLFOX4 plus weekly cetuximab with FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-expressing mCRC has been reported in detail [1]. A previous retrospective subgroup analysis investigated the association of tumour KRAS exon 2 mutation status and treatment outcome. Initial KRAS mutation testing was performed on genomic DNA samples that had been extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour tissue sections from OPUS study patients [2]. Prior to DNA extraction, stained slides had been reviewed by a pathologist to estimate overall neoplastic cell content; no lower limit precluding inclusion was defined. As the polymerase chain reaction clamping and melting curve technique used in this initial testing process was a highly sensitive method designed to enrich for mutant over wild-type sequences [1,7], micro- or macrodissection of the tissue sections had also not been carried out.

In the current extended RAS analysis, mutation testing was performed on those evaluable residual tumour genomic DNA samples (either tumour blocks or stained slides) from the initial investigation that had been categorised as wild-type at codons 12 and 13 of KRAS [2]; no restrictions were made based upon tumour content. Extended RAS testing was not carried out on those tumour DNA samples previously identified as having KRAS codon 12/13 mutations.

Due to the source and nature of the available tumour DNA, highly sensitive BEAMing technology was used (Appendix) [8]. This approach facilitates detection of mutant versus wild-type DNA sequences with mutant sequences present at ratios as low as 1:10,000 (0.01%) [9,10]. In the current analysis, a threshold of 0.1% mutant/wild-type sequence was prespecified as a technical lower limit for mutation identification. Extended RAS testing was undertaken by a contract research organisation, Sysmex Inostics GmbH (Hamburg, Germany).

26 mutations enumerated in the COSMIC and/or TCGA databases within KRAS exons 3 (codons 59, 61) and 4 (codons 117, 146) and NRAS exons 2 (codons 12, 13), 3 (codons 59, 61) and 4 (codons 117, 146) were assessed (Supplementary Table S1). Samples were not retested for KRAS exon 2 (codon 12/13) mutations.

2.2. Statistical methods and considerations

Analogous to the sensitivity of other approaches used to assign RAS mutation status clinically (including dideoxy sequencing, pyrosequencing and next generation sequencing [NGS]), tumours were classified as RAS mutant in the current study if the sum of the individual percentages of mutant over total amplified sequences was ⩾5% for the analysed loci, irrespective of whether all 26 loci were evaluable. Tumours were categorised as RAS wild-type only if all 26 mutation assays were evaluable, with a <5% summed mutation prevalence across all loci. This cutoff was selected after an initial evaluation of the impact of using different cutoff values.

With a clinical cutoff date of 30th November 2008, this retrospective analysis comparatively investigated efficacy in patient subgroups defined according to RAS and BRAF tumour mutation status. Hazard and odds ratios compared FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab versus FOLFOX4 alone. For tumour response, differences between treatment groups were assessed with Cochran-Mantel–Haenszel tests. For overall survival and PFS times, univariate Cox proportional hazards models were deployed to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Median survival was estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier method [11] (product limit estimates) and P values derived from log-rank tests. All analyses were stratified based on Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (determined via the interactive voice response system at randomisation).

3. Results

3.1. Patients and samples

Of 179 OPUS study patients in the KRAS population with tumours previously typed as KRAS exon 2 wild-type, RAS tumour mutation status was evaluable in 118 (66%) patients (for study profile, see Supplementary Figure S1). Using a ⩾5% mutant/wild-type sequence diagnostic cutoff, other RAS mutations were scored in 31/118 (26%) patients. Those with other RAS mutations in the current analysis were grouped with patients previously classified as having tumours with KRAS exon 2 mutations (n = 136) to comprise a combined population of patients with any RAS mutations (n = 167). Using as cutoff the technical lower limit for mutation identification of ⩾0.1% mutant/wild-type sequences, other RAS mutations were scored in 36/118 (31%) patients. The most common site of other RAS mutations was within KRAS exon 4 (Supplementary Table S2).

The tumours of eight of the 118 RAS evaluable patients were known to carry BRAF mutations; all eight tumours were RAS wild-type; 79/118 (67%) tumours were wild-type for both RAS and BRAF.

3.2. Comparability of evaluable populations

Baseline characteristics of the RAS evaluable population and RAS wild-type and other RAS mutant subgroups were broadly similar to those of the KRAS exon 2 wild-type subgroup of the intention-to-treat population (Supplementary Table S3). However, a smaller fraction of patients with a tumour RAS mutation (25/167; 15%) had received prior adjuvant therapy compared with those with RAS wild-type tumours (23/87; 26%).

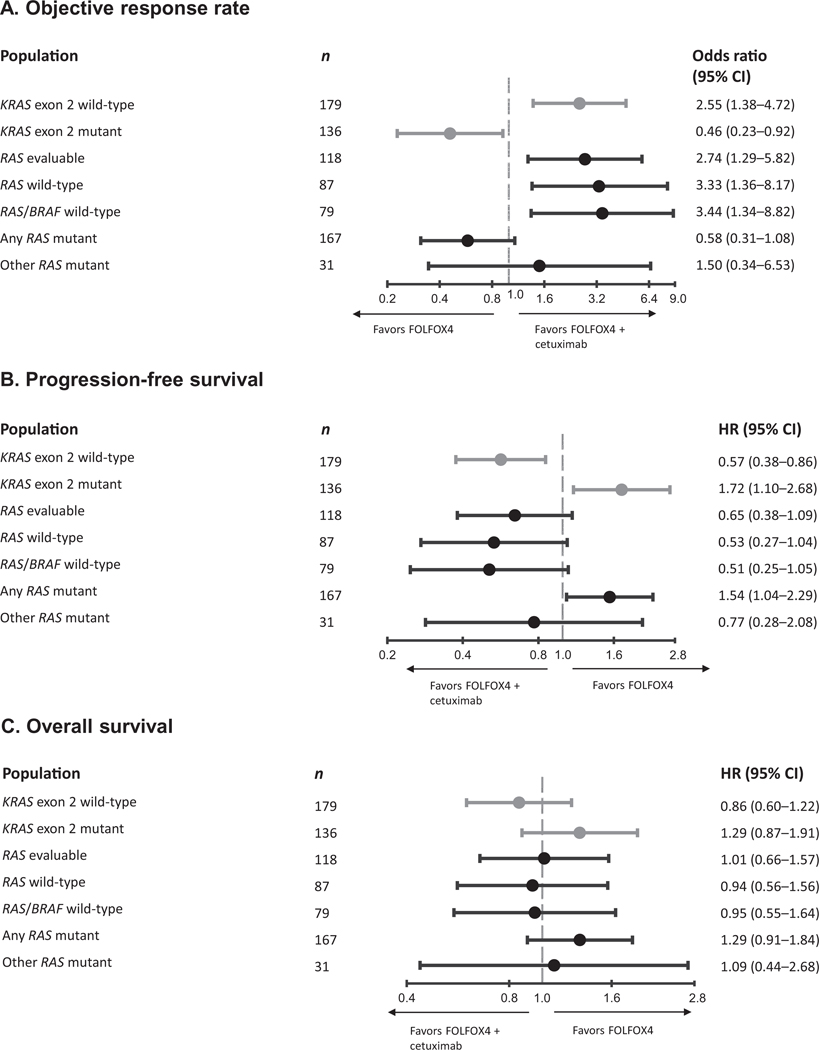

The outcomes in the RAS evaluable subpopulation were similar to the KRAS exon 2 wild-type population, although there was a trend for reduced benefit from the combination with respect to PFS and overall survival (Table 1; Fig. 1); definitive conclusions cannot be drawn due to the relatively modest number of available patients in the RAS evaluable subpopulation.

Table 1.

Efficacy data in the KRAS exon 2 wild-type subgroup of KRAS population and RAS subpopulations.

| Parameter | KRAS exon 2 wild-type | Any RAS mutant | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall n = 179 | RAS evaluable n = 118 | RAS wild-type n = 87 | Other RAS mutant n = 31 | n = 167 | ||||||

| FOLFOX4 + cetuximab | FOLFOX4 | FOLFOX4 + cetuximab | FOLFOX4 | FOLFOX4 + cetuximab | FOLFOX4 | FOLFOX4 + cetuximab | FOLFOX4 | FOLFOX4 + cetuximab | FOLFOX4 | |

| n = 82 | n = 97 | n = 53 | n = 65 | n = 38 | n = 49 | n = 15 | n = 16 | n = 92 | n = 75 | |

| Best overall response,a n (%) | ||||||||||

| Complete | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (7) | 1 (6) | 1 (1) | 3 (4) |

| Partial | 44 (54) | 32 (33) | 27 (51) | 20 (31) | 20 (53) | 14 (29) | 7 (47) | 6 (38) | 33 (36) | 35 (47) |

| Stable disease | 24 (29) | 42 (43) | 14 (26) | 28 (43) | 10 (26) | 21 (43) | 4 (27) | 7 (44) | 40 (43) | 28 (37) |

| Progressive disease | 5 (6) | 15 (15) | 4 (8) | 10 (15) | 4 (11) | 8 (16) | 0 | 2 (13) | 13 (14) | 7 (9) |

| Not evaluable | 6 (7) | 7 (7) | 5 (9) | 6 (9) | 2 (5) | 6 (12) | 3 (20) | 0 | 5 (5) | 2 (3) |

| Objective response rate, % | 57 | 34 | 57 | 32 | 58 | 29 | 53 | 44 | 37 | 51 |

| 95% CI | 46–68 | 25–44 | 42–70 | 21–45 | 41–74 | 17–43 | 27–79 | 20–70 | 27–48 | 39–62 |

| Odds ratio | 2.55 | 2.74 | 3.33 | 1.50 | 0.58 | |||||

| 95% CI | 1.38–4.72 | 1.29–5.82 | 1.36–8.17 | 0.34–6.53 | 0.31–1.08 | |||||

| P (CMH test) | 0.0027 | 0.0086 | 0.0084 | 0.59 | 0.0865 | |||||

| Progression-free survival time | ||||||||||

| Median, months | 8.3 | 7.2 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 12.0 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 5.6 | 7.8 |

| 95% CI | 7.2–12.0 | 5.6–7.4 | 7.3–12.7 | 5.5–7.5 | 5.8–NR | 4.7–7.9 | 3.6–12.7 | 6.2–10.3 | 4.4–7.5 | 6.7–9.3 |

| Hazard ratio | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.77 | 1.54 | |||||

| 95% CI | 0.38–0.86 | 0.38–1.09 | 0.27–1.04 | 0.28–2.08 | 1.04–2.29 | |||||

| P (log-rank test) | 0.0064 | 0.1003 | 0.0615 | 0.60 | 0.0309 | |||||

| Overall survival time | ||||||||||

| Median, months | 22.8 | 18.5 | 19.5 | 17.8 | 19.8 | 17.8 | 18.4 | 17.8 | 13.5 | 17.8 |

| 95% CI | 19.3–25.9 | 16.4–22.6 | 15.7–24.8 | 15.0–23.9 | 16.6–25.4 | 13.8–23.9 | 8.6–26.3 | 15.0–NR | 12.1–17.7 | 15.9–23.6 |

| Hazard ratio | 0.86 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.09 | 1.29 | |||||

| 95% CI | 0.60–1.22 | 0.66–1.57 | 0.56–1.56 | 0.44–2.68 | 0.91–1.84 | |||||

| P (log-rank test) | 0.39 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.1573 | |||||

Note: analyses were stratified according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

FOLFOX4, 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and oxaliplatin; CMH, Cochran-Mantel–Haenszel; NR, not reached; CI, confidence interval.

As assessed by independent review.

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios for objective response (A) and hazard ratios for disease progression or death from any cause (B) and death (C) according to tumour KRAS exon 2 and RAS mutation status. HR, hazard ratio.

3.3. Efficacy according to RAS mutation status

Because of the limited population size, formal assessment of biomarker treatment interactions was not possible and we limited ourselves to a description of the efficacy outcomes across end-points for evaluable patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type tumours harbouring other RAS mutations (n = 31). For objective response and PFS, we observed a possible cetuximab benefit. For overall survival, a possible disadvantage was observed (Table 1, Fig. 1). None of the differences in outcome between treatment groups were statistically significant and confidence intervals for odds and hazard ratios were wide.

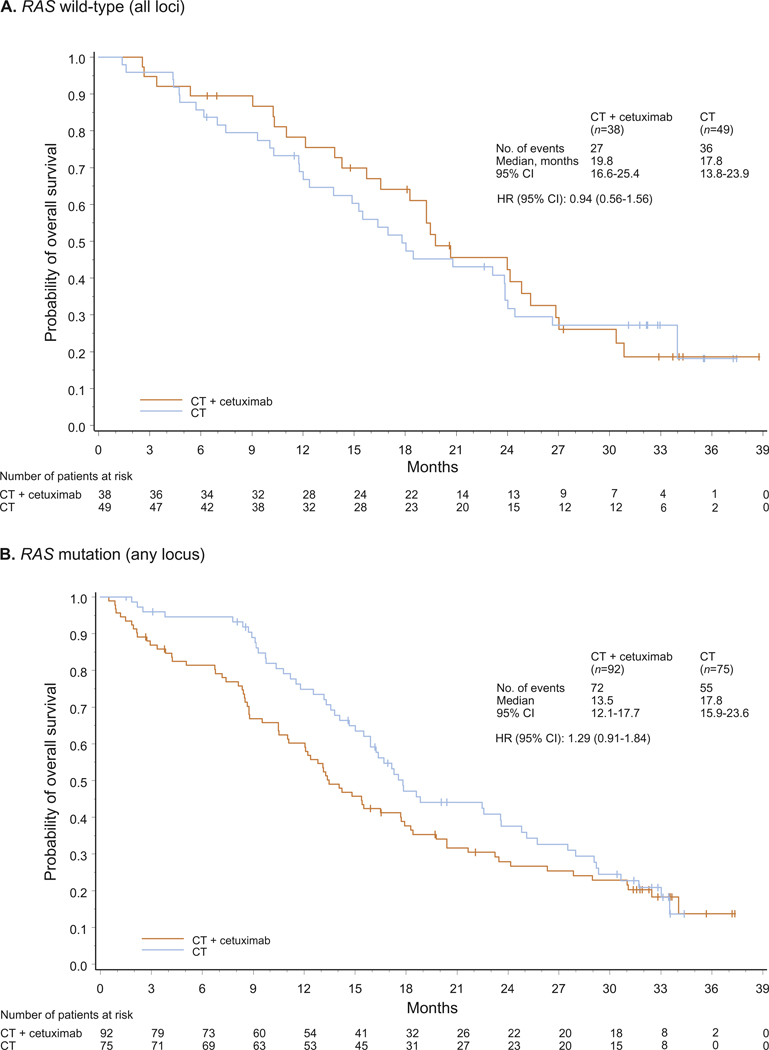

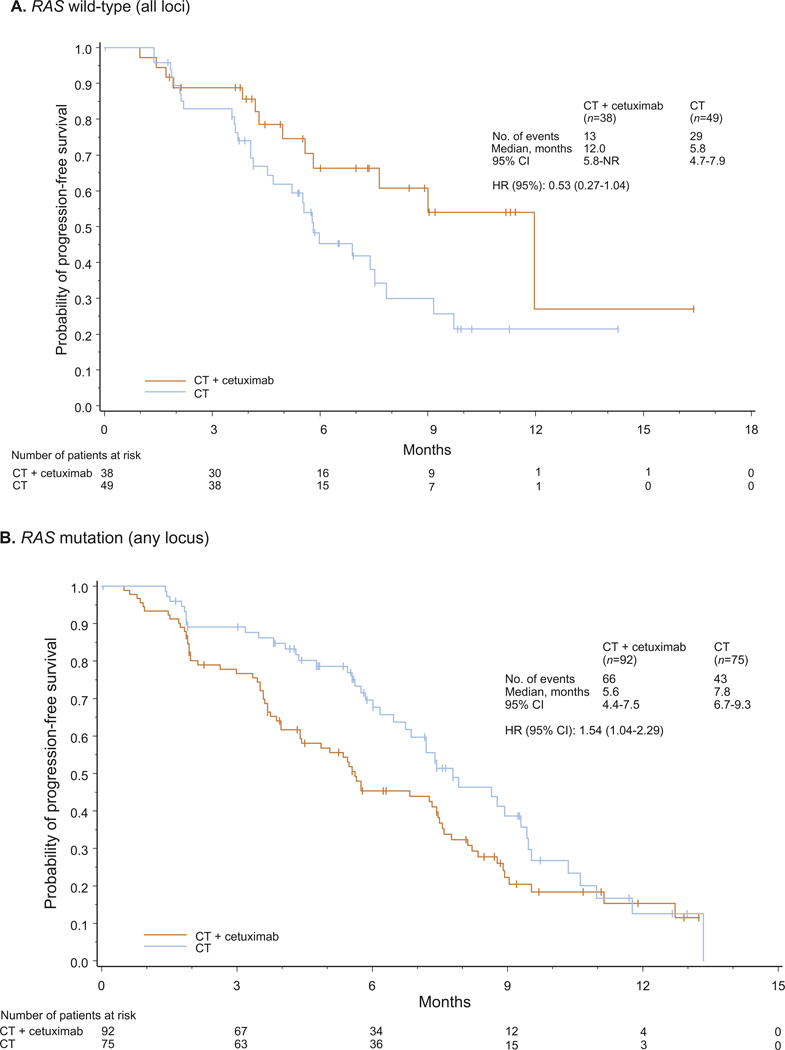

In patients with RAS wild-type tumours (n = 87), using a 5% cutoff to define mutation status, a clear and significant benefit in objective response rate (primary study end-point) was associated with the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4. The magnitude of benefit, as measured by the odds ratio, was more favourable towards FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab compared with the corresponding outcome in the RAS evaluable population. In addition, hazard ratios for progression-free and overall survival suggested trends towards greater cetuximab benefit in the RAS wild-type group compared with the RAS evaluable group (for efficacy outcome summaries, see Table 1, Figs. 1–3, and Figures S2–S3). Results for the RAS wild type/BRAF wild-type population were very similar to those of the RAS wild-type population (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure S4); the small number of available patients precludes the drawing of definitive conclusions. Outcome was also investigated for the group of patients with any RAS mutation (n = 167). Across efficacy end-points, a clear detrimental effect associated with the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4 was apparent in this population.

Fig. 3.

Overall survival for patients with RAS wild-type (A) and any RAS mutant (B) tumours. CT, chemotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached.

Using as threshold the technical lower limit for mutation identification of 0.1% mutant versus wild-type sequences to determine RAS status, 5/118 (4%) tumours classified as RAS wild-type when using a 5% cutoff were instead scored as RAS mutant. The treatment effect could not be reliably assessed in this group of five patients due to the small sample size. However, outcomes were investigated in RAS wild-type (n = 82), other RAS mutant (n = 36) and any RAS mutant (n = 172) populations, as defined according to the 0.1% cutoff (Supplementary Table S5). The effect of reclassifying these five tumours as RAS mutant was that the apparent cetuximab benefit in the RAS wild-type population was marginally improved. Conversely, in the redefined RAS mutant subgroups, the detrimental trends in relation to overall survival were marginally strengthened.

3.4. Safety

The overall incidence of adverse events according to treatment group was broadly similar across the KRAS and RAS population subgroups (Supplementary Table S6). In addition, the incidence of commonly reported adverse events in each treatment group was also generally similar across these populations and in line with expectations.

4. Discussion

Our analyses of the impact on treatment outcome of other tumour RAS mutations in OPUS study patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type mCRC mirrored a similar retrospective analysis of the PRIME study, which investigated the effect of adding panitumumab to FOLFOX4 in the same setting [6]. In the current analysis, a clear cetuximab benefit was apparent in relation to objective response rate, the primary study end-point, in patients with newly defined RAS wild-type tumours. The magnitude of this benefit appeared to be higher in the RAS wild-type group compared with the overall RAS evaluable group. In relation to progression-free and overall survival, although limited by population size, there again appeared to be trends towards greater cetuximab benefit in the RAS wild-type group compared with the RAS evaluable group. Relative treatment outcomes were essentially unchanged following the exclusion of patients with tumour BRAF mutations from the RAS wild-type population; definitive conclusions cannot be drawn due to the relatively modest number of available patients.

The number of patients with other tumour RAS mutations was small, making the drawing of definitive conclusions difficult. However, there was no evidence of a cetuximab benefit in this subgroup. In contrast to recently reported findings from the CRYSTAL study [15] – which demonstrated a lack of detrimental effects when cetuximab was added to FOLFIRI in patients with RAS mutations – a clear detrimental effect associated with the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4 was apparent across end-points in the combined group of OPUS patients with any RAS mutation. This is essentially in line with data from the corresponding analysis of the PRIME study [6], which showed detrimental treatment effects in terms of PFS and overall survival upon the addition of panitumumab to FOLFOX4 in patients with RAS mutations. Furthermore, our observations regarding beneficial treatment effects upon the addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy in patients with RAS wild-type tumours is consistent with prior data from CRYSTAL and PRIME [6,15]. Additionally, in the phase III CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial, patients in the RAS wild-type subgroup who received FOLFOX plus cetuximab (n = 198) had a long median overall survival time of 32.5 months (95% CI 26.1–40.4) [12]. Taken together with the survival data from the phase III FIRE-3 trial [13] and the phase II PEAK trial [14], the above observations indicate that in molecularly selected patients, EGFR antibody therapy in combination with first-line chemotherapy can now achieve median overall survival times in excess of 30 months.

RAS mutations were scored in 26% of evaluable OPUS study patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type tumours using the selected ⩾5% mutant to wild-type sequence cutoff. This mutation frequency is broadly in line with those reported in other first-line mCRC studies, which used pyrosequencing, or dideoxy sequencing/WAVE analysis [6,13,14]. In common with these studies, and also the parallel RAS analysis of the CRYSTAL study [15], the most common location of RAS mutations outside of KRAS exon 2 in OPUS study patients was KRAS exon 4. There is little understanding yet about the biology of these rarer mutations, and large meta-analyses will be needed in the future to reliably assess the effect of single mutations.

As the significance of low prevalence RAS mutations in relation to the effectiveness of EGFR antibody therapy in mCRC is not clear [16–19], we also explored treatment outcome in RAS subgroups defined according to a threshold of 0.1% mutant to wild-type sequences. The effect of using the lower cutoff was to move five patients previously classified as RAS wild-type to the mutant group. This resulted in marginally more favourable outcomes for FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab over FOLFOX4 alone in the revised RAS wild-type population and marginally worse outcomes for this treatment group in the revised other RAS mutant population. However, as the number of patients in the other RAS mutant treatment subgroups is small, analysis of outcome may be influenced by imbalances in prognostic variables. Therefore, whether this is a meaningful result cannot be determined, and the power of the current analysis, which was not set up to define an optimal cutoff, is not sufficient to provide the basis for a recommendation on the most appropriate RAS mutation detection cutoff for clinical use.

In summary, in line with the survival data from the PRIME study and the conclusions of a recent meta-analysis [5], our findings suggest that patients with other tumour RAS mutations did not benefit from the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4, and further, that there may be a detrimental effect on efficacy in this patient group. Therefore, exclusion of patients with other tumour RAS mutations from the KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type treatment population may improve the benefit associated with the addition of cetuximab to FOLFOX4. The optimal cutoff value of RAS mutant to wild-type alleles which might be used clinically to assign RAS status requires further clarification. Nevertheless, and consistent with the current revised European regulatory label, restricting cetuximab administration to patients with RAS wild-type tumours seems to enable the further tailoring of therapy to maximise patient benefit.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival for patients with RAS wild-type (A) and any RAS mutant (B) tumours. CT, chemotherapy; HR, hazard ratio.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing services were provided by Jim Heighway (Cancer Communications & Consultancy Ltd, Knutsford, UK; preparation of initial draft) and Scott Valastyan (ClinicalThinking, Hamilton, NJ, USA; revision of initial draft and subsequent resubmission) and funded by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Funding

This work was supported by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Appendix A. Methods

RAS mutation analysis

If a tumour-extracted sample had a total DNA amount of less than 100 genomic equivalents, it was deemed to be non-analysable. For potentially evaluable samples, an initial multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the relevant regions of KRAS and NRAS was carried out. Nested singleplex PCR reactions were then performed for each amplicon using primers containing universal adapters for the subsequent emulsion PCR. These pre-amplification products were quantified, normalised and subjected to a water-in-oil emulsion PCR step, in which single-molecule amplification was performed on magnetic beads linked to DNA sequences complimentary to the universal primer. The magnetic beads coated with PCR product were recovered from the emulsion and hybridised to fluorescently labelled oligonucleotide probes specific for wild-type or mutant sequences. The bead population was subsequently analysed using flow cytometry to detect beads that contained PCR products and further, to distinguish between beads coated with wild-type or mutant DNA.

For each tumour sample, the fraction of mutant RAS alleles was calculated by dividing the number of mutant beads by the total number of beads with PCR product (equal to the sum of mutant, wild-type and mutant/wild-type beads).

Efficacy assessments

Primary target variable was best overall confirmed tumour response to therapy of either CR or PR available 20 weeks after the last patient had been randomised. Confirmed tumour response was evaluated by an Independent Review Committee using modified World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria (and omitting improvement of response after surgery).

PFS time was defined as the time in months from randomisation until radiological confirmed PD was first observed, or death occurred due to any cause within 90 days after the last tumour assessment or randomisation. In patients without a progression date or death date more than 90 days after the last tumour assessment or randomisation, the PFS time was censored on the date of last tumour assessment before the end of the study or randomisation, whatever came later.

Overall survival time was defined as the time from the day of randomisation to death. For patients who were still alive at the time of study analysis or who were lost to follow up, survival time was censored at the last recorded date that the patient was known to be alive or at the date of data cutoff, whatever occurred earlier.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.007.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

CB has a consultancy/advisory relationship with, and has received honoraria from, Merck Serono; C-HK has received honoraria and research funding from Merck KGaA; FC has a consultancy/advisory relationship with, and has received honoraria and research funding from, Merck Serono; H-JL has a consultancy/advisory relationship with, and has received honoraria, research funding and travel/accommodation expenses from, Merck Serono; VH has a consultancy/advisory relationship with, has participated in satellite symposia for, has provided expert testimony for, and has receiving honoraria, research funding and travel/accommodation expenses from, Merck KGaA; FB and KD are compensated employees of Merck KGaA; UK was a compensated employee of Merck KGaA up until submission of the manuscript; JHvK has a consultancy/advisory relationship with, and has received honoraria, research funding and travel/accommodation expenses from, Merck Serono; ST has a consultancy/advisory role with, and has received honoraria, lecture fees and research funding from, Merck Serono.

References

- [1].Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Hartmann JT, et al. Efficacy according to biomarker status of cetuximab plus FOLFOX-4 as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the OPUS study. Ann Oncol 2011;22:1535–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D945–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, Rowland A, et al. Extended RAS mutations and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody survival benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Oncol 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1023–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen CY, Shiesh SC, Wu SJ. Rapid detection of K-ras mutations in bile by peptide nucleic acid-mediated PCR clamping and melting curve analysis: comparison with restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Clin Chem 2004;50:481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dressman D, Yan H, Traverso G, et al. Transforming single DNA molecules into fluorescent magnetic particles for detection and enumeration of genetic variations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:8817–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Diehl F, Li M, Dressman D, et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:16368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Diehl F, Schmidt K, Durkee KH, et al. Analysis of mutations in DNA isolated from plasma and stool of colorectal cancer patients. Gastroenterology 2008;135:489–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lenz H, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, et al. CALGB/SWOG 80405: Phase III trial of FOLFIRI or mFOLFOX6 with bevacizumab or cetuximab for patients with expanded RAS analyses in untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum. ESMO 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1065–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schwartzberg LS, Rivera F, Karthaus M, et al. PEAK: a randomized, multicenter phase II study of panitumumab plus modified fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Kohne CH, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Parsons BL, Myers MB. Personalized cancer treatment and the myth of KRAS wild-type colon tumors. Discov Med 2013;15:259–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Laurent-Puig P, Pekin D, Normand C, et al. Clinical relevance of KRAS-mutated sub-clones detected with picodroplet digital PCR in advanced colorectal cancer treated with anti-EGFR therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tougeron D, Lecomte T, Pages JC, et al. Effect of low-frequency KRAS mutations on the response to anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2013;24:1267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Taly V, Laurent-Puig P, Pekin D, Doe J. Clinical significance of low frequency KRAS and BRAF subclones for advanced colon cancer management. American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting San Diego, CA, April 5–9, 2014: Abstr 2820. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.