Abstract

Environmental temperatures are a major constraint on ectotherm abundance, influencing their distribution and natural history. Comparing thermal tolerances with environmental temperatures is a simple way to estimate thermal constraints on species distributions. We investigate the potential effects of behavioral thermal tolerance (i. e. Voluntary Thermal Maximum, VTMax) on anuran local (habitat) and regional distribution patterns and associated behavioral responses. We tested for differences in Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax) of two sympatric frog species of the genus Physalaemus in the Cerrado. We mapped the difference between VTMax and maximum daily temperature (VTMax—ETMax) and compared the abundance in open and non-open habitats for both species. Physalaemus nattereri had a significantly higher VTMax than P. cuvieri. For P. nattereri, the model including only period of day was chosen as the best to explain variation in the VTMax while for P. cuvieri, the null model was the best model. At the regional scale, VTMax—ETMax values were significantly different between species, with P. nattereri mostly found in localities with maximum temperatures below its VTMax and P. cuvieri showing the reverse pattern. Regarding habitat use, P. cuvieri was in general more abundant in open than in non-open habitats, whereas P. nattereri was similarly abundant in these habitats. This difference seems to reflect their distribution patterns: P. cuvieri is more abundant in open and warmer habitats and occurs mostly in warmer areas in relation to its VTMax, whereas P. nattereri tends to be abundant in both open and non-open (and cooler) areas and occurs mostly in cooler areas regarding its VTMax. Our study indicates that differences in behavioral thermal tolerance may be important in shaping local and regional distribution patterns. Furthermore, small-scale habitat use might reveal a link between behavioral thermal tolerance and natural history strategies.

Introduction

Environmental temperatures are a major constraint on ectotherm abundance and diversity, influencing their distribution and natural history [1–3]. Several studies have explored environmental constraints on ectothermic vertebrates at regional and global scales [1, 4]. The physiological performance of individuals can be negatively affected by high environmental temperatures [5], which can lead to declining populations and/or local extinctions [6, 7]. Thus, knowing species thermal tolerance and exploring how environmental temperatures might affect their physiology and restrict their distribution is of primary concern for long-term conservation, especially under current global warming crisis (e.g. [8, 9]), as well as habitat disturbance causing microclimate changes (e.g. habitat fragmentation; [10]).

However, thermal tolerances are rarely taken into account in studies that focus on local distribution and habitat use. For instance, many studies infer potential distribution of species using solely environmental temperatures from occurrence localities to model their niche [11–14]. While the broad geographical range of a species most likely reflects its thermal tolerance (e.g. [15, 16]), local factors might also play a role in shaping abundance and distribution. At a local scale, high environmental temperatures and its daily variation in the microhabitats of small ectotherms (e.g. anurans and lizards) impose physiological constraints on their activity patterns and habitat use [12]. For example, in habitats where direct sunlight is limited, the variation in temperatures is lower than in open habitats, suggesting a possible interplay between thermal tolerance and habitat use [17]. However, studies that relate how thermal tolerances affect habitat use and distribution are scarce.

Thermal tolerances can be behavioral, when an animal moves or adjusts its body posture to thermoregulate, or physiological if it does not move but uses other strategies such as increased respiration rates [3]. Behavioral and physiological thermal tolerances impact not only species ranges, but also the distribution and abundance patterns of their populations [3]. Identifying thermal tolerance thresholds (i.e. measurable thermal limits) outside the range of preferred body temperatures (PBT) for thermoregulation (see [18]) allows for the identification of temperatures that directly affect the behavioral and physiological thermal tolerance of ectothermic organisms. One of the thresholds related to PBT is the Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax), which represents a behavioral thermal tolerance measure. VTMax is the maximum temperature that an organism will endure before trying to move to a place with a lower temperature, thus trying to maintain its body temperature within its range of PBT [3, 18, 19]. If an individual fails to respond to its VTMax, an increase in body temperature will expose it to its physiological thermal limit (i.e. its Critical Thermal Maximum), which can lead to functional collapse and consequently death due to overheating [19, 20]. Therefore, the behavioral response to upper limits might represent a more informative ecological threshold to identify thermal constraints on habitat use and geographic distribution [3, 8, 13]. Contrary to the Critical Thermal Maximum, the exposure to the VTMax does not induce an immediate loss of locomotion [3, 21]. Therefore, VTMax can more realistically portray changes in species behavior associated with their natural history.

Behavioral thermal tolerances can be influenced by factors such as reproductive status, sex, photoperiod, and hydration state [18, 22]. Additionally, thermal tolerances such as the VTMax might decrease with body size: due to thermal inertia, larger animals might have slower heating and cooling rates than small animals, which increases the exposed time to stressful thermal conditions [23, 24]. Thus, understanding the effects of these variables on the VTMax might help to evaluate its impact on habitat use and geographic distribution.

Herein we address the question: Does VTMax determine habitat use and regional distribution patterns in a pair of congeneric frogs, Physalaemus cuvieri and P. nattereri, which are widely sympatric in the savannas of Central Brazil? Our hypothesis is that, for being a measure that reflects avoidance of stressful thermal conditions, VTMax determines both habitat use and geographic distribution in these species. If VTMax decreases with body size (see above; [23, 24]), we predict that VTMax is lower in the larger species (P. nattereri). Furthermore, if VTMax determines habitat use and geographic distribution, we predict that (i) the species with lower VTMax is less abundant in open habitats, with higher environmental temperatures, and that (ii), regarding geographic distribution, both species occur mostly in localities where the maximum environmental temperature is below their VTMax. We expect that our results can contribute to assess the vulnerability of Neotropical frogs to climate change by integrating their behavioral thermal tolerances with their habitat use and distribution patterns, in order to identify areas with potential stressful climatic conditions to their populations.

Materials and methods

Focal species

Most species of the genus Physalaemus have sympatric populations along extensive areas, such as Physalaemus nattereri [25] and Physalaemus cuvieri [26] (see [27]), which are widespread in central South America [25, 26]. These species belong to different clades within Physalaemus (P. signifer and P. cuvieri clades, respectively; [28]). Physalaemus nattereri has a stout body, a moderate to large size (adult snout-to-vent length of 29.8–50.6 mm) and is endemic to the Cerrado, whereas P. cuvieri has a slenderer body, a smaller size (snout-to-vent length of adults 28–30 mm) and occurs throughout the Cerrado, in southern portions of the Amazon Forest and in the Atlantic Forest [29]). Although the populations traditionally assigned to P. cuvieri (see [27]) may include more than one cryptic species (see [28]), most of the distribution of P. cuvieri in the Cerrado correspond to a single lineage (Lineage 2 in [28]). These two species also differ in their biology. While P. cuvieri uses several aquatic habitats for reproduction and seeks shelter during the day in previously-dug burrows, P. nattereri breeds mostly in temporary puddles and buries itself in the soil during the day aided by metatarsal tubercles (S1 Fig) on its hind feet [29–31].

Physiological parameters

Capture and maintenance of individuals

Fieldwork was carried out at Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara (22°49’2.43"S, 49°14’11.29"W; WGS84, 590 m elevation), one of the few remnants of Cerrado savannas in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, with a total area of 2,712 ha [32]. The climate is Humid subtropical [33], with temperatures averaging 24°C and 16°C during January and July, the hottest and coldest months, respectively. The average annual rainfall is 1100–1300 mm, with marked dry and wet seasons (approximately April to September and October to March, respectively; [32]). The landscape not only consists of open grassland and savanna-type formations, such as ‘campo sujo’ and ‘campo cerrado’, but also of non-open vegetation types such as ‘cerrado strictu sensu’ (dense savanna) and ‘cerradão’ (cerrado woodland). Between 24 and 28 September 2018, we captured 14 individuals of P. nattereri and 20 of P. cuvieri in pitfall traps with drift fences [34, 35] and these individuals were housed individually in plastic boxes at room temperature. This study was conducted under a permit by Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais (CEUA #2325141019) of Instituto Butantan. All animals were alive after the experiments described below and were released the following morning at the site of capture.

Measurements of the Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax)

To obtain the VTMax for each species, we measured each individual at 100% hydration level less than 24 hours after capture. To reach maximum hydration level, each individual was placed in a cup with water ad libitum one hour prior to the experiment. Then, its pelvic waist was pressed to expel the urine and to obtain its 100% hydration level in relation to its standard body mass. We heated each individual inside a metal box wrapped in a thermal resistance for heating. The box had a movable lid, allowing the animal to easily leave the box when needed. A thin thermocouple (type-T, Omega®) was located in the inguinal region of each individual to record its body temperature during the heating [22]. Another type-T thermocouple was placed inside (on the surface) of the box to record heating rate of individuals. A dimmer previously connected to the box allowed to control that its temperature not exceeded 5–6°C the temperature of the individual, allowing the thermoregulation of individuals, and avoided thermal shock and/or a premature exit of the box by the frog (i. e. before VTMax is reached; [22]). The thermocouples were calibrated and connected to a FieldLogger PicoLog TC-08 to record temperature data every 10 seconds. The VTMax of each individual was recorded as its last body temperature at the time of leaving the box. Once its final body mass was measured, it was taken to a container with water for recovery. Furthermore, to control for a potential effect of photoperiod on behavioral thermal tolerances, we tested if the VTMax differed between different times of the day by testing half of the individuals of each species in different periods: 10:00 to 17:00 (daytime) and 19:00 to 00:00 (nighttime).

Statistical analyzes

We used Mann-Whitney U tests to compare the VTMax, and experimental variables between species. Experimental variables were: period (day or night), duration of experiment, initial body mass, initial body temperature, and heating rate. To test for the effect of possible confounding experimental variables on the VTMax, we constructed generalized least squares models for each species. We used the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) to select the model that best represented the effects of factors and their interactions on the VTMax of each species. Differences of two units in AIC (ΔAICc) were not considered to be different [36]. We considered the model with weighted AIC (wAICc) values close or equal to 1 to represent the strongest model. All statistical analyzes and plotting were performed in R 3.5.0 [37], with the nlme [38], ggplot2 [39] and AICcmodavg [40] packages.

Distribution and habitat

We used vouchered occurrence data for P. cuvieri (N = 163) and P. nattereri (N = 164) in the Cerrado from a distribution database built for another study [41]. We calculated and mapped the difference between the VTMax and maximum environmental temperature (ETMax; Bio 5; 30 seconds or ~1 km resolution from WorldClim Vr. 2.0; [42]), for each occurrence point of each species in Cerrado; the VTMax was that obtained at Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara. We used a Mann-Whitney U test to compare VTMax—ETMax of species occurrence records. All maps and GIS procedures were made in QGIS 3.12 [43]. We tested for differences between species in habitat use by comparing abundances in open (‘campo cerrado’, ‘campo sujo’, and ‘campo limpo’) and non-open habitats (gallery forest, ‘cerradão’ and cerrado stricto sensu; [44]) for communities within Cerrado where both species occur in sympatry, available in the literature [45–50]. We used PAST [51] to test for differences between the proportion of each species in open and non-open habitats with chi-square and Fisher Exact tests, the latter when at least one cell was < 5.

Results

Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax) and experimental conditions

We found that VTMax was significantly lower for P. cuvieri than for P. nattereri (Table 1; U = 51, p = 0.0013). We also found significant differences in initial body mass (Table 1; U = 0, p < 0.0001) between species, with P. nattereri being heavier. We did not find significant differences in start body temperatures (Table 1; U = 112, p = 0.3359), period of day (Table 1; U = 0.12, df = 32, p = 0.9051), duration of the experiment (Table 1; U = 128, p = 0.6872) and heating rate (Table 1; U = 123.5, p = 0.5752) between species (see S1, S2 and S3 Tables).

Table 1. Variation of the VTMax and predictor variables for P. cuvieri and P. nattereri from Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara, state of São Paulo, Brazil.

| Variable | Physalaemus cuvieri | Physalaemus nattereri | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | |

| VTMax | 30.20 ± 1.69°C | 27.48–33.13°C | 32.74 ± 2.14°C | 29.59–36.71°C |

| Day | 29.62 ± 1.48°C | 27.48–31.94°C | 34.18 ± 1.62°C | 32.09–36.71°C |

| Night | 30.69 ± 1.76°C | 28.14–33.13°C | 31.74 ± 1.96°C | 29.59–34.97°C |

| DOE | 27.85 ± 18.17 min | 6–86 min | 26.72 ± 20.07 min | 6–81 min |

| ST | 25.79 ± 1.18°C | 22.95–27.0°C | 26.41 ± 2.30°C | 22.73–30.58°C |

| IBM | 2.15 ± 0.72 g | 1.19–3.82 g | 7.27 ± 7.52 g | 4.86–32.45 g |

| HRA | 0.07 ± 0.07°C/min | 0.01–0.38°C/min | 0.12 ± 0.21°C/min | 0.06–0.84°C/min |

Predictor variables are: period of day (day and night), initial body temperature (ST), duration of experiment (DOE), initial body mass (IBM), and heating rate (HRA).

We compared six models for both species using the AIC selection criteria. For P. nattereri, the model including only period (day or night) was chosen as a better explanation of variation in the VTMax (Table 2), with higher values attained during daytime. For P. cuvieri, we retained the simpler null model, which showed a higher wAICc, which indicates that no variable explains the variation of the VTMax of this species (Table 3).

Table 2. Effect of period, start body temperature, duration, initial body mass, and heating rate on the Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax) of P. nattereri from Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara, state of São Paulo, Brazil.

| Model | Variables | Value | Std.Error | t-value | AICc | wAICc | ΔAICc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VI | Intercept | 34.245 | 0.7844 | 43.66 | 63.1 | 0.66 | 0.000 |

| Period | -2.3937 | 1.0072 | -2.377 | ||||

| I | Intercept | 32.8771 | 0.5729 | 57.384 | 65.13 | 0.24 | 2.04 |

| V | Intercept | 33.48146 | 6.78518 | 4.934 | 67.13 | 0.09 | 4.03 |

| Period | -2.35356 | 1.09774 | -2.144 | ||||

| Start body temperature | 0.02784 | 0.24653 | 0.113 | ||||

| IV | Intercept | 33.402492 | 7.257777 | 4.602 | 72.18 | 0.01 | 9.08 |

| Period | -2.375403 | 1.192946 | -1.991 | ||||

| Start body temperature | 0.027744 | 0.258758 | 0.107 | ||||

| Duration | 0.002234 | 0.029308 | 0.076 | ||||

| III | Intercept | 34.11138 | 7.23078 | 4.718 | 77.08 | 0 | 13.98 |

| Period | -2.9531 | 1.29369 | -2.283 | ||||

| Start body temperature | -0.03477 | 0.2628 | -0.132 | ||||

| Duration | 0.01298 | 0.03072 | 0.422 | ||||

| Initial body mass | 0.0873 | 0.08377 | 1.042 | ||||

| II | Intercept | 40.97635 | 8.8114 | 4.65 | 83.03 | 0 | 19.94 |

| Period | -4.69461 | 1.85994 | -2.524 | ||||

| Start body temperature | -0.28142 | 0.31754 | -0.886 | ||||

| Duration | 0.04667 | 0.03908 | 1.194 | ||||

| Initial body mass | 0.13547 | 0.08914 | 1.52 | ||||

| Heating rate | -5.52697 | 4.19531 | -1.317 |

Table 3. Effect of period, start body temperature, duration, initial body mass, and heating rate on the Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax) of P. cuvieri from Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara, state of São Paulo, Brazil.

| Model | Variables | Value | Std.Error | t-value | AICc | wAICc | ΔAICc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Intercept | 30.293 | 0.3788 | 79.98 | 81.52 | 0.48 | 0 |

| VI | Intercept | 29.69 | 0.5352 | 55.478 | 81.89 | 0.400 | 0.370 |

| Period | 1.0964 | 0.7337 | 1.494 | ||||

| V | Intercept | 28.01163 | 8.54933 | 3.276 | 84.99 | 0.08 | 3.47 |

| Period | 1.0601 | 0.7799 | 1.359 | ||||

| Start body temperature | 0.06593 | 0.3355 | 0.196 | ||||

| IV | Intercept | 24.27443 | 8.89011 | 2.73 | 86.91 | 0.03 | 5.39 |

| Period | 1.35975 | 0.81681 | 1.665 | ||||

| Start body temperature | 0.15946 | 0.33822 | 0.471 | ||||

| Duration | 0.02977 | 0.02327 | 1.279 | ||||

| III | Intercept | 24.16542 | 9.23459 | 2.617 | 91.07 | 0 | 9.55 |

| Period | 1.4054 | 0.89665 | 1.567 | ||||

| Start body temperature | 0.16829 | 0.35657 | 0.472 | ||||

| Duration | 0.03163 | 0.02728 | 1.16 | ||||

| Initial body mass | -0.09116 | 0.62658 | -0.145 | ||||

| II | Intercept | 24.89384 | 9.69648 | 2.567 | 95.73 | 0 | 14.21 |

| Period | 1.38928 | 0.92409 | 1.503 | ||||

| Start body temperature | 0.14817 | 0.37081 | 0.4 | ||||

| Duration | 0.03157 | 0.02811 | 1.123 | ||||

| Initial body mass | -0.05353 | 0.65185 | -0.082 | ||||

| Heating rate | -2.10171 | 5.68863 | -0.369 |

Distribution and habitat

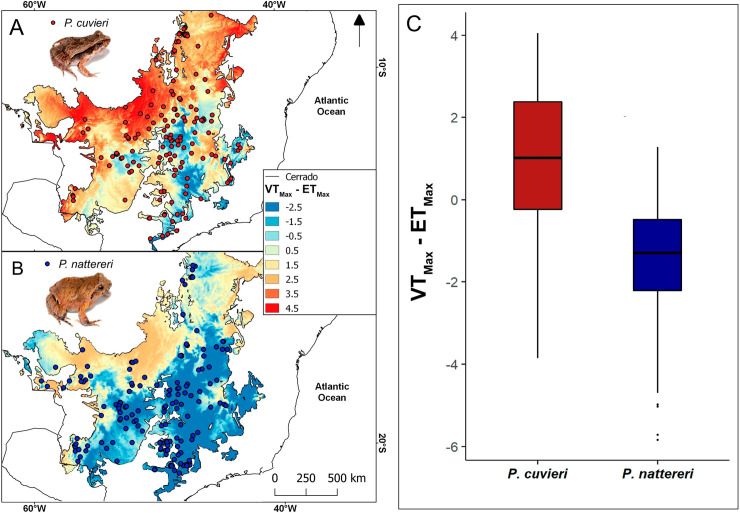

Overall distribution of occurrences was similar for the two species, occupying mainly the central and southern portions of the Cerrado (Fig 1; S4 Table). Thus, the distribution of environmental temperatures was similar for both species. However, because the VTMax was different between species, the resulting distribution of VTMax—ETMax values was markedly different (Fig 1A and 1B). The north central portion of the Cerrado showed much higher environmental temperatures than the VTMax of P. cuvieri (Fig 1A), while this region is mostly below the VTMax of P. nattereri (Fig 1B). Furthermore, VTMax—ETMax values were found to be significantly different between species (U = 2249, p < 0.001; Fig 1C). Physalaemus nattereri is mostly found (~ 80%) on localities that attain maximum temperatures equal to or lower than its VTMax, whereas P. cuvieri seems to be mostly distributed (~ 60%) in localities with temperatures higher than its VTMax (Fig 1C).

Fig 1. Geographical distribution of the studied species and VTMax—ETMax values throughout their distribution.

(A) Distribution of Physalaemus cuvieri; (B) distribution of Physalaemus nattereri; and (C) comparison of VTMax—ETMax values at occurrence points between these species in the Cerrado.

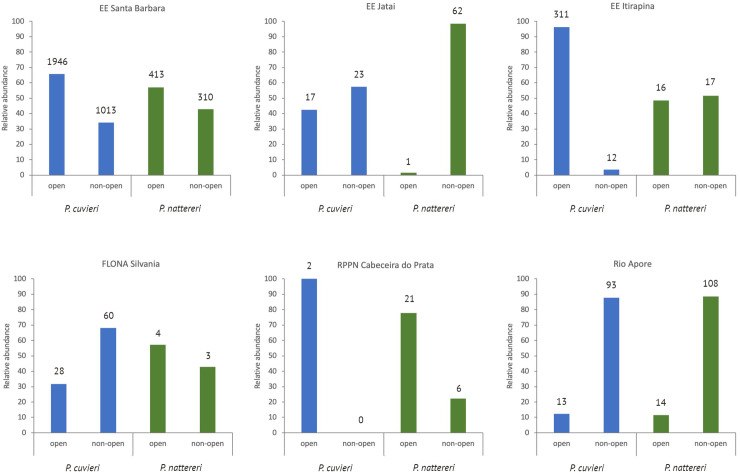

We obtained abundance data for five additional localities in southern Cerrado, most of them from protected areas (Fig 2; see also S2 Fig). In only two localities [49 and 50 + this study] we found significant differences between the proportion of each species in open and non-open habitats (S5 Table); in both cases, P. cuvieri was proportionally more abundant than P. nattereri in open areas. Considering the pooled abundances of these six studies, P. cuvieri was nearly twice more abundant in open (N = 2317 individuals) than in non-open areas (N = 1201), while P. nattereri was similarly abundant in open (N = 469) and non-open areas (N = 506; S5 Table). Furthermore, P. cuvieri was more abundant in open areas than in non-open areas in three localities and P. nattereri, in two localities, whereas both species were more abundant in non-open areas in two localities each (Fig 2; S5 Table).

Fig 2. Relative abundance (in %) of P. cuvieri (blue bars) and P. nattereri (green bars) in open and non-open areas in Cerrado (see S2 Fig).

Sources of data: [45–50]. Detailed data on the abundance of the frogs in different vegetation types are in S5 Table.

Discussion

Our results show that the Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax) is higher for P. nattereri than for P. cuvieri, contrary to our first prediction that larger body size (and an expected slower cooling rate) would reflect in a lower VTMax. Additionally, no difference in heating rate was found between species and only P. nattereri showed a significant difference on its VTMax between day and night. Regarding habitat use, in general, we found the species with lower VTMax, P. cuvieri, to be more abundant in open habitats than in non-open habitats, which does not support our prediction that the species with the lower thermal tolerance should be less abundant in habitats with higher environmental temperatures. Lastly, in spite of both species being widespread in Cerrado, they showed different patterns of VTMax—ETMax values throughout their ranges, with only P. nattereri having most of its records in localities with temperatures below its VTMax. Thus, only for P. nattereri did we confirm our prediction that regional distribution comprises mostly localities with environmental temperatures below the VTMax.

Regarding the lower VTMax values in the nocturnal period for P. nattereri, this result warrants future studies exploring variation in behavioral thermal tolerances in diurnal and nocturnal species in both periods of the day. Indeed, a higher VTMax during the day could reflect physiological adjustment of its thermal safety margin (see [22]), thus helping to protect the frog from extreme, potentially deleterious temperatures.

The difference in VTMax values between these two frog species might be related to their different body sizes [51, 52] but additionally might reflect their physiology and natural history. For instance, although there was no difference in heating rate between the species, P. nattereri might still cool slower when exposed to high temperatures because of its larger body size. As for differences in natural history, P. nattereri burrows in the soil [30, 31], which may allow it to quickly reduce its body temperature, since the soil is a good thermal insulant [53]. On the other hand, P. cuvieri uses pre-existing cavities as diurnal refuge (e. g. see [54]), which, in spite of also being below ground level (S3 Fig), are more exposed to variations in external environmental temperatures. Yet, despite having a lower VTMax, most of the localities of P. cuvieri in Cerrado have temperatures above its VTMax. This suggests that other aspects of its thermal ecology might be playing a role in avoiding thermal stress, such as a reduced daily activity time or physiological traits regulating hydration state.

As wet skin ectotherms, hydration level can also influence the temperatures tolerated and selected by individuals for thermoregulation in their habitats [55–58]. This has been observed for other frog species (e. g. Rana catesbeiana; [22]), with individuals decreasing their VTMax in response to dehydration, and some even losing their behavioral response to the VTMax. Even though we controlled for hydration when measuring VTMax, individuals in the wild rarely are at their optimal hydration level and thus desiccation might influence local frog distribution [59]. Desiccation has been shown to be correlated with substrate use [60] and with dispersal probability throughout the landscape [59]. Additionally, closely related frog species may vary in their response to desiccation along thermal gradients, with some species showing greater resistance to water loss at lower temperatures, and others at higher temperatures [61]. Therefore, knowing the interaction between VTMax and hydration state of individuals in their environments can help to understand patterns and/or limits in their distribution [59, 62–64].

We found that P. cuvieri, the species with the lower VTMax, was in general more abundant in open habitats, despite our second prediction that the species with the lower VTMax should be less abundant in warmer habitats (up to 35–37 ºC in open habitats versus 32–35 ºC in non-open habitats in our study area; pers. obs.). On the other hand, P. nattereri, which showed a higher VTMax, was in general similarly abundant in open and non-open habitats. These results may reflect clade-related physiological constraints and further studies on the relationship of VTMax with habitat use should include additional species from both clades within the genus Physalaemus to which these species belong [28]. Although competition could also lead to differences in habitat use, especially in closely related species, we found no evidence of competition between our focal species in cerrado habitats (e. g. extensive niche overlap associated with limited resources, negative correlations between abundances; [65]).

Even though we found a relatively high variation in the data on habitat use for both species, the difference in the use of open and non-open habitats between species seems to be reflected in the overall patterns of their distribution throughout the Cerrado regarding their VTMax. Indeed, P. cuvieri is in general more abundant in open and warmer habitats and occurs mostly in areas that attain maximum temperatures higher than its VTMax, whereas P. nattereri tends to be abundant in both open and non-open (and cooler) areas and occurs mostly in areas that attain maximum temperatures below its VTMax. Although geographic biases in sampling effort could affect these results, our study species are usually extremely abundant and conspicuous in localities where they occur, making them very easy to detect in inventories, by almost all frog sampling techniques. Thus, we are confident that the records in the maps of Fig 1 correspond to their overall actual distribution in the Cerrado. We highlight the importance of considering different spatial scales—geographic range and habitat use, as proposed by [66]—because these allow to quantify how species distribution may reflect different aspects of their niches.

Despite numerous ecophysiological studies comparing how environmental temperatures influence habitat use of species [11, 13], these rarely account for thermal tolerances. Using behavioral thermal tolerances, such as the VTMax, allows for the integration of thermoregulatory behavior, which usually happens before critical limits are reached [3, 67, 68]. Furthermore, integrating the VTMax with natural history and geographic distribution data can be critical to understand how future scenarios of global warming might impact distribution [69, 70], especially for amphibians which are already under a global decline worldwide [71, 72]. Our study indicates that differences in behavioral thermal tolerance may be important in shaping local and regional distribution patterns. Furthermore, small-scale habitat use might reveal a link between behavioral thermal tolerance and natural history strategies. Further studies using additional sympatric species of the genus Physalaemus (e. g. P. centralis, from the same clade of P. cuvieri, and P. marmoratus, from the same clade of P. nattereri) could help to elucidate if those differences are due to body size variation or if tolerances are phylogenetically conserved. We hope this study stimulates future mechanistic studies on amphibian thermal ecology and on the impact of global warming on species distribution.

Supporting information

P. nattereri (A–B) and P. cuvieri (C–D), showing the inner and outer metatarsal tubercles in the detail. Note the much larger and strongly keratinized tubercles in P. nattereri. Photos not to scale.

(PDF)

Relative abundance (in %) of P. cuvieri (blue circles) and P. nattereri (red circles) in open (brown) and non-open (green) areas in Cerrado (see S5 Table). The localities are: Floresta Nacional (FLONA) de Silvânia (GO), Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural (RPPN) Cabeceira do Prata (MS), Estação Ecológica (EE) Jataí (SP), Estação Ecológica de Itirapina (SP), Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara (SP), and Aporé River (GO and MS). Sources of data: [45–50]. Detailed data on the abundance of the frogs in different vegetation types are in S5 Table.

(PDF)

A) Temperature measured with sensors buried in the soil at superficial soil (green) and below ground level (red) and in a frog-sized plaster model (blue). B) Illustration of the measurement setup.

(PDF)

Data on each individual tested for Voluntary Thermal Maximum (VTMax) in this study.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data from a distribution database built for another study [41].

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Instituto Florestal for allowing our work at Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara (permit #260108–008.476/2014; ICMBio-SISBIO for the permit to collect frog specimens (permit #50658–3). Paula Valdujo kindly provided occurrence data for both species. The comments and suggestions from an anonymous reviewer resulted in changes that enhanced the scientific quality of our manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

MM thanks Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo for a grant (#2018/14091-8) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico for a research fellowship (# 306961/2015-6). JCDR and FCS thank Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Malcolm JR, Liu C, Neilson RP, Hansen L, Hannah LEE. Global warming and extinctions of endemic species from biodiversity hotspots. Conserv Biol. 2006; 20: 538–548. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post E, Pedersen C, Wilmers CC, Forchhammer MC. Warming, plant phenology and the spatial dimension of trophic mismatch for large herbivores. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2008; 275: 2005–2013. 10.1098/rspb.2008.0463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camacho A, Rusch T, Ray G, Telemeco RS, Rodrigues MT, Angilletta MJ. Measuring behavioral thermal tolerance to address hot topics in ecology, evolution, and conservation. J. Therm. Biol. 2018; 73: 71–79. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley LB, Rodda GH, Jetz W. Thermal and energetic constraints on ectotherm abundance: a global test using lizards. Ecology. 2008; 89: 48–55. 10.1890/07-0845.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie DJ, Fritz JT. Global patterns of animal abundance and species energy use. Oikos. 1993; 56–68. 10.2307/3545095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen AP, Brown JH, Gillooly JF. Global biodiversity, biochemical kinetics, and the energetic-equivalence rule. Science. 2002; 297: 1545–1548. 10.1126/science.1072380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pörtner HO, Farrell AP. Physiology and climate change. Science. 2008; 322: 690–692. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20145158 10.1126/science.1163156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinervo B, Mendez-De-La-Cruz F, Miles DB, Heulin B, Bastiaans E, Villagrán-Santa Cruz M, et al. Erosion of lizard diversity by climate change and altered thermal niches. Science. 2010; 328:894–899. 10.1126/science.1184695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stillman JH. Heat waves, the new normal: summertime temperature extremes will impact animals, ecosystems, and human communities. Physiology. 2019; 34(2): 86–100. 10.1152/physiol.00040.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urbina-Cardona JN, Olivares-Peres M, Reynoso VH. Herpetofauna diversity and microenvironment correlates across a pasture-edge-interior ecotone in tropical rainforest fragments in Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve of Veracruz, Mexico. Biol Conserv. 2006; 132: 61–75. 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman PE. Habitat specificity in three sympatric species of Ameiva (Reptilia: Teiidae). Ecology. 1969; 50:476–481. 10.2307/1933903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter WP, Mitchell JW, Beckman WA, DeWitt CB. Behavioral implications of mechanistic ecology. Oecologia. 1973. 13:1–54. 10.1007/BF00379617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes AD, Spey IK, Rohde L, Brose U, Dell AI. Individual behaviour mediates effects of warming on movement across a fragmented landscape. Funct Ecol. 2015; 29: 1543–1552. 10.1111/1365-2435.12474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freitas C, Olsen E, Knutsen H, Albretsen J, Moland E. Temperature-associated habitat selection in a cold-water marine fish. J Anim Ecol. 2015; 85(3): 628–637. 10.1111/1365-2656.12458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouveia SF, Hortal J, Tejedo M, Duarte H, Cassemiro FA, Navas CA, et al. Climatic niche at physiological and macroecological scales: the thermal tolerance–geographical range interface and niche dimensionality. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2014; 23(4): 446–456. 10.1111/geb.12114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunday JM, Bates AE, Kearney MR, Colwell RK, Dulvy NK, Longino JT, et al. Thermal-safety margins and the necessity of thermoregulatory behavior across latitude and elevation. PNAS. 2014; 111: 5610–5615. 10.1073/pnas.1316145111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Recoder RS, Magalhães-Júnior A, Rodrigues J, de Arruda Pinto HB, Rodrigues MT, Camacho A. Thermal constraints explain the distribution of the climate relict lizard Colobosauroides carvalhoi (Gymnophthalmidae) in the semiarid caatinga. S Am J Herpetol. 2018; 13(3): 248–259. 10.2994/SAJH-D-17-00072.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camacho A, Rusch TW. Methods and pitfalls of measuring thermal preference and tolerance in lizards. J Therm Biol. 2017; 68: 63–72. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowles RB, Bogert CM. A preliminary study of the thermal requirements of desert reptiles. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 1944; 83: 261–296. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezende EL, Castañeda LE, Santos M. Tolerance landscapes in thermal ecology. Funct Ecol. 2014; 28: 799–809. 10.1111/1365-2435.12268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lutterschmidt WI, Hutchison VH. The critical thermal maximum: history and critique. Can J Zool. 1997. a. 75: 1561–1574. 10.1139/z97-783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guevara-Molina EC, Camacho A, Gomes FR. Effects of dehydration on thermoregulatory behavior and thermal tolerance limits of Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802). J Therm Biol. 2020. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2020.102721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter WP, Gates DM. Thermodynamic equilibria of animals with environment. Ecol Monogr. 1969; 39: 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lunghi E, Manenti R, Canciani G, Scarì G, Pennati R, Ficetola GF. Thermal equilibrium and temperature differences among body regions in European plethodontid salamanders. J Therm Biol. 2016; 60: 79–85. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aquino L, Reichle S, Silvano D, Scott N. Physalaemus nattereri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2004: e.T57267A11597340. 2004. Available from: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2004.RLTS.T57267A11597340.en. Downloaded on 28 June 2020 [DOI]

- 26.Mijares A, Rodrigues MT, Baldo D. Physalaemus cuvieri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010: e.T57250A11609155. 2010. Available from: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-2.RLTS.T57250A11609155.en. Downloaded on 28 June 2020. [DOI]

- 27.Frost DR. Amphibian Species of the World [cited 14 March 2020]. Available from: http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html.

- 28.Lourenço LB, Cíntia PT, Baldo D, Nascimento J, Garcia PCA, Andrade GV, et al. Phylogeny of frogs from the genus Physalaemus (Anura, Leptodactylidae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015; 92: 204–216. 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nascimento LB, Caramaschi U, Cruz CAG. Taxonomic review of the species groups of the genus Physalaemus Fitzinger, 1826 with revalidation of the genera Engystomops Jiménez-de-la-Espada, 1872 and Eupemphix Steindachner, 1863 (Amphibia, Anura, Leptodactylidae). Arch Mus Nac. 2005; 63: 297–320. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brasileiro CA, Sawaya RJ, Kiefer MC, Martins M. Amphibians of an open Cerrado fragment in southeastern Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 2005; 5: 93–109. 10.1590/S1676-06032005000300006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giaretta AA, Facure KG. Terrestrial and communal nesting in Eupemphix nattereri (Anura, Leiuperidae): interactions with predators and pond structure. J Nat Hist. 2006; 40: 2577–2587. 10.1080/00222930601130685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo ACG, Durigan G. Plano de Manejo da Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara. São Paulo: Instituto Florestal; 2011. Available at: https://www.infraestruturameioambiente.sp.gov.br/institutoflorestal/wp-content/uploads/sites/234/2013/03/Plano_de_Manejo_EEc_Santa_Barbara.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Köppen W. Climatologia: con un estudio de los climas de la tierra. 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corn PS. Straight line drift fences and pitfall traps. In: Heyer WR, Donnelly MA, McDiarmid RW, Hayek LAC, Foster MS, editors; Measuring and monitoring biological diversity: standard methods for amphibians Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC, 1994. pp.109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cechin SZ, Martins M. Eficiência de armadilhas de queda (pitfall traps) em amostragens de anfíbios e répteis no Brasil. Rev Bras Zool. 2000; 17: 729–740. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Liu Q. Comparison of Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) in selection of stock-recruitment relationships. Fish Res. 2006; 77: 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- 37.R (Core Team). 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Linear mixed-effects models: basic concepts and examples. Mixed-effects models in S and S-Plus. 2000; 3–56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazerolle MJ, Mazerolle MMJ. Package ‘AICcmodavg’. R package version 2.2–2. 2019.

- 41.Valdujo PH, Silvano DL, Colli GR, Martins M. 2012. Anuran Species Composition and Distribution Patterns in Brazilian Cerrado, a Neotropical Hotspot. S Am J Herpetol. 2012; 7:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fick SE, Hijmans RJ. WorldClim 2: new 1‐km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2017; 37: 4302–4315. [Google Scholar]

- 43.QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.osgeo.org. 2020

- 44.Ribeiro JF, Walter BMT. Fitofisionomias do bioma Cerrado. Embrapa Cerrados-Capítulo em livro científico (ALICE). 1998. pp. 166. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Araujo CO, Almeida-Santos SM. Composição, riqueza e abundância de anuros em um remanescente de Cerrado e Mata Atlântica no estado de São Paulo. Biota Neotrop. 2013; 13: 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duleba S. Herpetofauna de serrapilheira da RPPN Cabeceira do Prata, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. M.Sc Thesis, Fundação Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul. 2013. Available from: https://repositorio.ufms.br:8443/jspui/bitstream/123456789/2084/1/Samuel%20Duleba.pdf

- 47.Ramalho W. Guerra Batista V. Passos Lozi LR. Anfíbios e répteis do médio rio Aporé, estados de Mato Grosso do Sul e Goiás, Brasil. Neotrop Bio Conserv. 2014: 9: 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliveira TALD. Anurofauna em uma área de ecótono entre Cerrado e Floresta Estacional: diversidade, distribuição e a influência de características ambientais. M.Sc Thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista. 2012. Available from: https://repositorio.unesp.br/bitstream/handle/11449/87577/oliveira_tal_me_sjrp_parcial.pdf?sequence=1

- 49.Motta J. A herpetofauna no cerrado: composição de espécies, sazonalidade e similaridade. M.Sc Thesis Universidade Federal de Goiás. 1999. Available from: https://repositorio.bc.ufg.br/tede/bitstream/tede/9953/5/Dissertação%20-%20José%20Augusto%20de%20Oliveira%20Motta%20-%201999.pdf

- 50.Thomé MTC. Diversidade de anuros e lagartos em fisionomias de Cerrado na região de Itirapina, sudeste do Brasil. Ph.D. Thesis, University of São Paulo. 2006. Available from: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/41/41134/tde-29092006-100104/en.php

- 51.Tracy CR. A model of the dynamic exchanges of water and energy between a terrestrial amphibian and its environment. Ecol Monogr. 1976; 46:293–326. 10.2307/1942256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tracy CR, Christian KA, Tracy CR. Not just small, wet, and cold: effects of body size and skin resistance on thermoregulation and arboreality of frogs. Ecology. 2010; 91: 1477–1484. 10.1890/09-0839.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pianka ER. Ecology and natural history of desert lizards: analyses of the ecological niche and community structure (Vol. 4887). Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bastos RP, Motta JDO, Lima LP, Guimarães LD. Anfíbios da floresta nacional de Silvânia, Estado de Goiás. Stylo gráfica e editora, Goiânia. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson RC, Andrade DV. Trading heat and hops for water: Dehydration effects on locomotor performance, thermal limits, and thermoregulatory behavior of a terrestrial toad. Ecol Evol. 2017; 7: 9066–9075. 10.1002/ece3.3219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Angilletta MJ, Wilson RS, Navas CA, James RS. Tradeoffs and the evolution of thermal reaction norms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003; 18: 234–240. 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00087-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Navas CA, Gomes FR, Carvalho JE. Thermal relationships and exercise physiology in anuran amphibians: Integration and evolutionary implications. Comp Biochem Phys A. 2008; 151: 344–362. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Artacho P, Saravia J, Ferrandière BD, Perret S, Galliard L. Quantification of correlational selection on thermal physiology, thermoregulatory behavior, and energy metabolism in lizards. Ecol Evol. 2015; 5: 3600–3609. 10.1002/ece3.1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watling JI, Braga L. Desiccation resistance explains amphibian distributions in a fragmented tropical forest landscape. Landsc Ecol. 2015; 30: 1449–1459. 10.1007/s10980-015-0198-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young JE, Christian KA, Donnellan S, Tracy CR, Parry D. Comparative analysis of cutaneous evaporative water loss in frogs demonstrates correlation with ecological habits. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2005; 78: 847–856. 10.1086/432152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beuchat CA, Pough FH, Stewart MM. Response to simultaneous dehydration and thermal stress in three species of Puerto Rican frogs. J. Comp Physiol B. 1984; 154: 579–585. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tingley R, Shine R. Desiccation risk drives the spatial ecology of an invasive anuran (Rhinella marina) in the Australian semi-desert. Plos One. 2011; 6: e25979 10.1371/journal.pone.0025979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown GP, Kelehear C, Shine R. Effects of seasonal aridity on the ecology and behaviour of invasive cane toads in the Australian wet-dry tropics. Funct Ecol. 2011; 25: 1339–1347. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01888.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Titon JB, Gomes FR. Associations of water balance and thermal sensitivity of toads with macroclimatic characteristics of geographical distribution. Comp Biochem Phys A. 2017; 208: 54–60. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morin PJ. Community ecology. 2nd ed Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Candolle AP. Essai élémentaire de géographie botanique. FS Laeraule. 1820. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams SE, Shoo LP, Isaac JL, Hoffmann AA, Langham G. Towards an integrated framework for assessing the vulnerability of species to climate change. Plos Biol. 2008; 6: e325 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinclair BJ, Marshall KE, Sewell MA, Levesque DL, Willett CS, Slotsbo S, et al. Can we predict ectotherm responses to climate change using thermal performance curves and body temperatures? Ecol Lett. 2016; 19: 1372–1385. 10.1111/ele.12686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carey C, Alexander MA. Climate change and amphibian declines: is there a link? Divers Distrib. 2003; 9: 111–121. 10.1046/j.1472-4642.2003.00011.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parmesan C. Influences of species, latitudes and methodologies on estimates of phenological response to global warming. Global Change Biol. 2007; 13(9): 1860–1872. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01404.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alford RA, Dixon PM, Pechmann JH. Global amphibian population declines. Nature. 2001; 412: 499–500. 10.1038/35087658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blaustein AR, Walls SC, Bancroft BA, Lawler JJ, Searle CL, Gervasi SS. Direct and indirect effects of climate change on amphibian populations. Diversity. 2010; 2: 281–313. 10.3390/d2020281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]