Abstract

The rarity of mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) has resulted in diffuse literature consisting of small case series, thus precluding a consensus treatment approach. We conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review to investigate the association of treatment type (acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL], acute myeloid leukemia [AML], or “hybrid” regimens), disease response, and survival. We searched seven databases from inception through June 2017 without age or language restriction. Included studies reported sufficient treatment detail for de novo MPAL classified according to the well-established European Group for Immunological Characterization of Acute Leukemias (EGIL) or World Health Organization (WHO2008) criteria. Meta-analyses and multivariable analyses of a patient-level compiled case series were performed for the endpoints of complete remission (CR) and overall survival (OS). We identified 97 reports from 33 countries meeting criteria, resulting in 1,499 unique patients with data, of whom 1,351 had sufficient detail for quantitative analysis of the study endpoints. Using either definition of MPAL, meta-analyses revealed that AML induction was less likely to achieve a CR as compared to ALL regimens, (WHO2008 odds ratio [OR] = 0.33, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.18–0.58; EGIL, OR = 0.18, 95% CI 0.08–0.40). Multivariable analysis of the patient-level data supported poorer efficacy for AML induction (versus ALL: OR = 0.45 95% CI 0.27–0.77). Meta-analyses similarly found better OS for those beginning with ALL versus AML therapy (WHO2008 OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.26–0.77; EGIL, OR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.24–0.78), but multivariable analysis of patient-level data showed only those starting with hybrid therapy fared worse (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.11, 95% CI 1.30–3.43). MPAL definition did not impact trends within each endpoint and were similarly predictive of outcome. Using either definition of MPAL, ALL-therapy is associated with higher initial remission rates for MPAL and is at least equivalent to more intensive AML therapy for long-term survival. Prospective trials are needed to establish a uniform approach to this heterogeneous disease.

Introduction

Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) is a rare diagnosis constituting 2–5% of acute leukemia [1]. The complex phenotype exhibited by this type of leukemia historically resulted in a myriad of treatment approaches utilizing therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or so-called “hybrid” therapy mixing elements of both. As a rare disease, current evidence for the treatment of MPAL is limited to small case series, often diffusely published across a variety of international pathology and oncology journals. Determining best therapy is further complicated by the lack of a uniform definition with two different classification systems for MPAL commonly used today: the European Group for Immunological Characterization of Acute Leukemias (EGIL) and the World Health Organization’s published iteration in 2008 (WHO2008) [2–5] with minimal changes in the WHO2016 update [6]. Interpretation of clinical outcomes across classification systems is confounded by important differences in the definition of MPAL resulting in overlapping but distinct patient populations. Both classifications remain in use internationally, with continued controversy whether one is more advantageous [1]. Few studies include classification of MPAL using both systems, and all represent small case series with fewer than 50 patients in total, thereby limiting comparisons of clinical outcomes between definitions. The dearth of prospective trials with such diverse, scattered retrospective data is a significant hurdle to developing an evidence-based treatment approach by clinicians currently caring for this rare disease. The objective of this meta-analysis and systematic review was to therefore answer the question: is AML-based or ALL-based therapy associated with greater rates of complete remission (CR) and/or overall survival (OS) in patients with MPAL? To our knowledge, this is the first systematic approach to quantitatively synthesize available evidence for MPAL addressing the association of therapy type with early disease response and survival.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted by a research librarian (L.K.) using a combination of controlled vocabulary when possible and keywords in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [7]. To ensure inclusion of all available data for this rare disease, a comprehensive search was undertaken using multiple databases (Medline/Pubmed, EMBASE (initially through OvidSP and later via Elsevier), Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, Clinicaltrials.gov). All seven databases were searched from their inception through June 2017 with no language restriction. As MPAL is often inconsistently labeled in the literature, the search strategy was intentionally broad to maximize the chances for identification of all published reports of patients with MPAL. Included terminology was representative of different descriptions of MPAL (e.g., “biphenotypic leukemia” OR “bilineal leukemia” OR “mixed leukemia”). The literature search was supplemented by review of cited references from included case series. All references were compiled into an Endnote (X7) library. Following removal of duplicates, title and abstract review was independently performed by two authors (E.O., M.M.); in case of disagreement, final decision was reached by consensus. The full search strategy inclusive of search terms is provided in the supplement (see Supplementary Methods).

Eligibility

Eligible studies had to meet the following criteria: a de novo acute leukemia (i.e., excluding secondary cancers, nor presentation at relapse as MPAL, nor relapsed MPAL), specifically state the classification system (EGIL or WHO2008) used to establish the diagnosis, describe sufficient treatment to determine therapy type, and include sufficient response data per therapy type to inform the study endpoints for CR and OS. Studies reporting MPAL using the WHO2016 definition (described albeit not yet formally published) were included within the WHO2008 category as only subtle distinctions are present in the updated definition [6]. Studies were excluded that reported only combined ALL/AML/MPAL or combined EGIL/WHO2008 data wherein the contribution of therapy to definition-specific outcomes could not be identified. Sufficient treatment data were defined as, at minimum, reporting of chemotherapy agents, protocols, or authors’ description of “therapy-directed” at ALL, AML, or hybrid (or similar verbiage). Studies reporting the use of non-cytotoxic chemotherapy alone (such as immune modulators, epigenetic therapy) or palliative chemotherapy only were excluded. Acute undifferentiated leukemia (AUL) was excluded as a distinct diagnosis [4, 6]. Due to the low prevalence of disease and the goal to quantitatively analyze all relevant information, studies of any design were incorporated including individual case reports and case series.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one author (M.M.) and independently verified by a second author (E.O.). Data of interest consisted of type of research (retrospective, prospective, clinical trial), treatment years (or publication year if not available), consortia where applicable, country of origin, and treatment regimen or chemotherapy agents. Patient characteristics included age, sex, ethnicity, and race. Age was classified as pediatric (≤18 years) or adult (>18 years) or as reported within the study as “adult,” “pediatric,” or “mixed” if not separated in the report. Disease presentation data included MPAL definition (EGIL or WHO2008), phenotype (B/Myeloid [B/My], T/Myeloid [T/My], B/T, B/T/Myeloid [B/T/My]), lineage (bi-lineage [Bi-L], biphenotypic [Bi-P]), and presenting features (white blood cell [WBC] count, central nervous system [CNS] involvement, and recurrent cytogenetic features (presence/absence of BCR-ABL, rearrangements in the KMT2A gene [KMT2Ar, formerly “MLLr”], or ETV6/RUNX1). Treatment characteristics included therapy type (ALL, AML, hybrid), use of stem cell transplant (SCT), and use of a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI). When therapy type was not classified by regimen or assigned by authors within the case report (i.e., only chemotherapy agents listed), induction therapy was considered to be ALL-based if it included steroids, vincristine, asparaginase, AML if it included anthracycline and cytarabine, and “hybrid” if it included all five of these agents. Outcomes of interest included post-induction CR (yes/no) and OS. CR was defined using traditional morphology criteria and/or as a reported CR. In addition to aggregate data, when available, detailed information was extracted from case reports and case series to enable patient-level analyses as a “compiled case-series.”

Statistical approach

The primary and secondary endpoints of interest were post-induction CR and OS, respectively. The proximal measure of CR was selected as the primary endpoint to best understand treatment sensitivity of MPAL. By focusing on induction, treatment heterogeneity was minimized, thus enabling a 1:1 relationship between therapy type and immediate disease response. Candidate predictors were type of induction, age (adult/pediatric), phenotype (B/My, T/My, B/T, B/T/My), lineage (Bi-P, Bi-L), and SCT. Summary measures were generated from case series reports for inclusion in the meta-analyses. Meta-analyses were conducted within each definition of MPAL to evaluate outcomes per MPAL definition and to enable comparisons between the two systems (EGIL versus WHO2008). Log odds ratios and log relative failure rates were pooled using the random effect method [8]. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the Q-statistic along with the proportion of variation (I2). Multivariable regression analyses for the meta-analyses were not possible as only marginal totals of patients for categories of independent variables were typically provided with inadequate information to describe the association between different variables. Analyses were performed on data from the patient-level compiled case series using multivariable logistic regression analysis for CR and multivariable Cox regression analysis for OS. Age, therapy type, phenotype, lineage, and MPAL definition were included as candidate predictors in each model. All models were performed with backward stepwise main effects analyses using p < 0.10 for retention. As a final step, removed variables were retested for improvement of the final model. Interactions between the MPAL definition variable and main effects were tested for plausible evidence that the observed effect might differ depending on definition. Examination of the impact of treatment era was limited by case series reporting only the range of years during which cases were treated instead of a patient-specific year. As described in detail in the Supplementary Methods, we explored this indirectly using a simulation approach to examine the impact of including treatment year in the regression models for CR and OS. Data for clinical features of MPAL presentation were analyzed for aggregate and patient-level data; aggregate data was synthesized by weighting each measure by patients included per report. Publication bias for aggregate data was assessed through visualization of funnel plots. Data quality was not formally assessed as all included studies were descriptive from retrospective cohorts. P-values of <0.05 were generally considered statistically significant. All statistical computations were performed on Stata, version 14 (Statacorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Additional detail for the statistical approach is provided in the supplement (Supplementary Methods).

Results

Search results

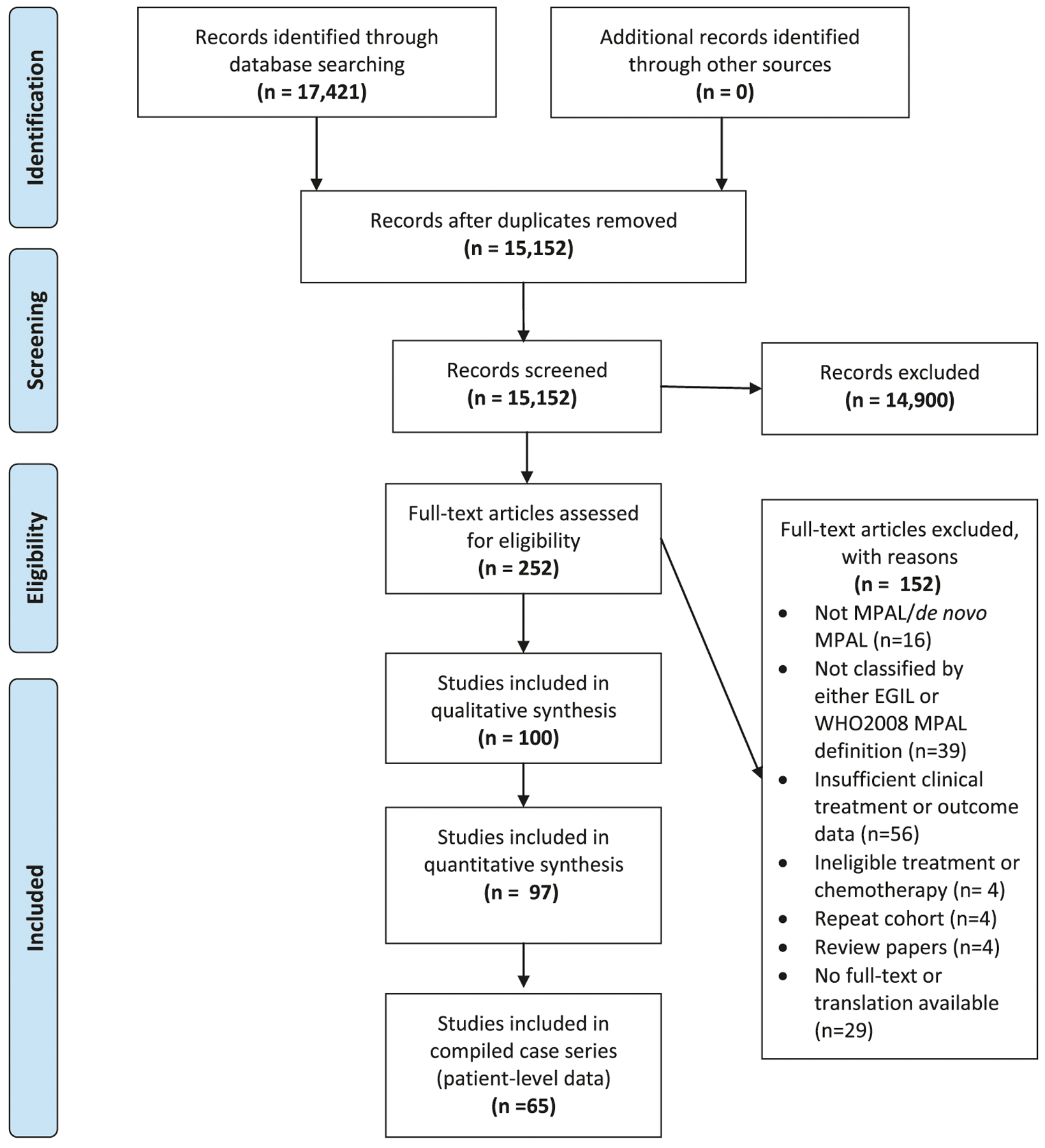

The search strategy yielded 17,421 reports fulfilling the intended search terms for this heterogeneous disease with no reports identified from other sources. Following assessment of title and abstract, 252 met criteria for full-text review (Fig. 1, PRISMA Flow Diagram). The final quantitative assessment included 97 studies whose characteristics are described in Supplementary Table 1 [9–106]. From these, data for 1,499 individual patients were extracted, 759 patients met the criteria for MPAL via EGIL, 740 via WHO2008, and 54 of these were reported to satisfy both definitions. From this cohort, 1,351 unique patients fulfilled the EGIL and/or WHO definition for MPAL and provided sufficient information for inclusion in at least one quantitative analysis for the study endpoints of CR or OS. The remaining 148 patients (three reports [15, 71, 77]) did not provide adequate information for either study endpoint and were included in the description of the presenting features of MPAL only. Thirty-two patients were treated with regimens not otherwise classified. These were defined during data extraction (AML therapy = daunorubicin–cytarabine [“DA,” n = 5], idarubicin–cytarabine [“IA,” n = 2], cytarabine–daunorubicin–etoposide [“ADE,” n = 1]; ALL therapy = cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxor-ubicin, and dexamethasone [“hyperCVAD,” n = 5], vincristine, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, prednisone, mitoxantrone [“VCEP-M,” n = 19]). Patient-level data for the compiled case series was drawn from 65 of the 97 reports and including detailed information for 342 patients for analysis of CR and 240 for analysis of OS. Three additional studies [107–109] did not meet eligibility criteria for inclusion in the quantitative analysis but are included in the discussion (no attributable definition [n = 2], inadequate treatment data [n = 1]). Reports were drawn from the international literature, with patients treated from 33 different countries.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Study cohort and presenting features of MPAL

Systematic review of the literature revealed 31 reports describing the prevalence of MPAL, with a mean prevalence of 2.8% of acute leukemia (range 0.3–9.0%). Presenting characteristics of MPAL are shown in Table 1 according to definition and report type with several trends apparent irrespective of definition. In general, MPAL did not present commonly with hyperleukocytosis, with a median peak WBC at diagnosis of 12–28 K/μL in the aggregate and patient-level data. Only approximately one in five patients in the compiled case series presented with a severe hyperleukocytosis of ≥100,000/μL. Recurrent leukemic cytogenetic abnormalities were relatively infrequent, with BCR-ABL present in <25%, and KMT2Ar and ETV6/RUNX1 in ≤10%. Only 17 of the 51 BCR-ABL+ patients within the compiled case series were actively reported as receiving a TKI during their frontline therapy. Detailed review of these 17 cases showed no added toxicity with the addition of the TKI. Involvement of the CNS was uncommon at the time of diagnosis, affecting <20% of patients. Where reported, Bi-P MPAL was far more common than Bi-L MPAL. B/My MPAL was the most prevalent phenotype followed by T/Myeloid with B/T and B/T/My MPAL relatively infrequent except within the WHO2008 compiled case series.

Table 1.

Presenting characteristics of patients with MPAL

| Variable | Category | Aggregate studiesa | Patient-level dataa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGIL, WHO n, nb | EGIL | WHO2008 | EGIL, WHO n/nb | EGIL | WHO2008 | ||

| Age, years | Median (range) | 376, 450 | 25.8 (9.2–49.2) | 31.2 (9.8–60.0) | 302, 82 | 17.0 (0.0–79.0) | 13.2 (0.5–81.0) |

| Adult (%) | 282, 244 | 28.7 | 48.8 | 302, 85 | 49.0 | 47.1 | |

| Pediatric (%) | 282, 244 | 71.3 | 51.2 | 302, 85 | 51.0 | 52.9 | |

| Sex | Male (%) | 462, 585 | 57.2 | 63.3 | 275, 82 | 60.7 | 64.6 |

| WBC (K/μL) | Median (range) | 199, 333 | 20.2 (1.0–665) | 18.1 (1.4–474) | 212, 74 | 12.3 (0.5–603) | 27.8 (1.0–403) |

| ≥50 (%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 212, 74 | 6.6 | 14.9 | |

| ≥100 (%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 212, 74 | 18.4 | 23.0 | |

| CNS diseasec | Positive (%) | 154, 316 | 17.8 | 12.5 | 91, 32 | 16.5 | 6.3 |

| Cytogenetics | BCRABL (%) | 318, 565 | 13.1 | 18.0 | 285, 77 | 13.0 | 19.5 |

| ETV6/RUNX1 (%) | 227, 263 | 8.7 | 3.2 | 204, 56 | 4.9 | 0.0 | |

| KMT2Ar (%) | 257, 513 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 269, 76 | 7.8 | 10.5 | |

| Lineage | Bi-P (%) | 84, 0 | 92.9 | n/a | 138, 62 | 89.9 | 74.2 |

| Bi-L (%) | 84, 0 | 7.1 | n/a | 138, 62 | 10.1 | 25.8 | |

| Phenotype | B/Myeloid (%) | 205, 343 | 68.8 | 69.4 | 302, 85 | 55.6 | 44.7 |

| T/Myeloid (%) | 205, 343 | 28.3 | 30.6 | 302, 85 | 35.4 | 38.8 | |

| B/T (%) | 205, 343 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 302, 85 | 4.3 | 14.1 | |

| B/T/Myeloid (%) | 205, 343 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 302, 85 | 4.6 | 2.4 | |

WBC presenting white blood cell count, CNS central nervous system, Bi-P Bi-phenotype, Bi-L Bi-lineal (more than one distinct blast population), n/a not applicable or not reported. KMT2Ar rearrangements in KMT2A gene (historically labeled MLL gene rearrangements [MLLr])

Summary statistics for studies reporting aggregate data versus case-series describing patient-level data

Number of patients with classifiable data by definition for each variable. For aggregate data, summary values are weighted per number of patients per report

CNS positive = any blasts present, reported as “CNS+” or “CNS2” or “CNS3”

Predictors of CR

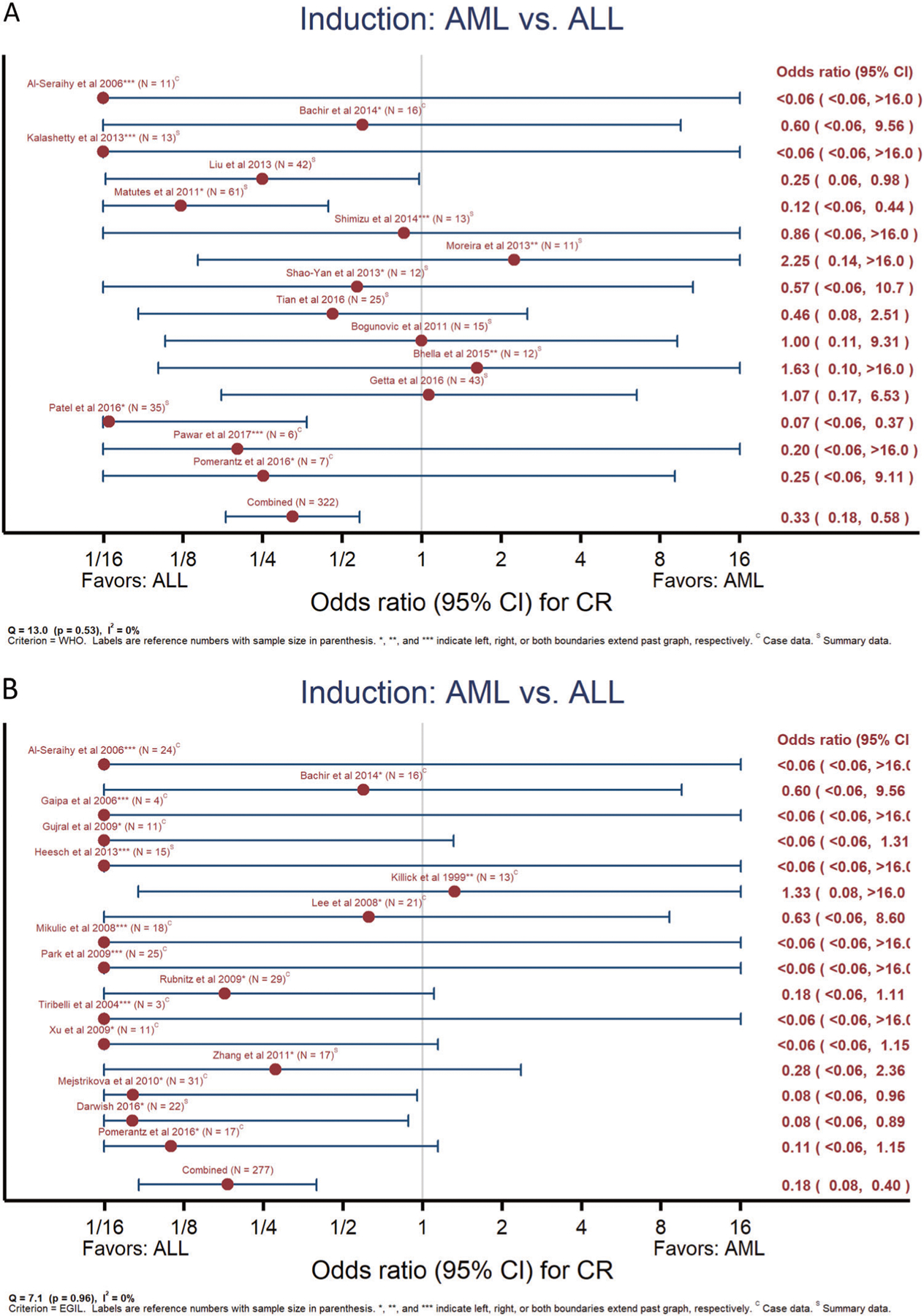

ALL induction therapy was associated with a more than three-fold greater CR rate than AML therapy irrespective of MPAL definition (Fig. 2a: WHO2008, n = 322, Odds ratio [OR] = 0.33, 95% Confidence interval [95% CI]0.18–0.58; Fig. 2b: EGIL, n = 277, OR = 0.18, 95% CI 0.08–0.40). Minimal and insignificant between-study heterogeneity was present (WHO2008 I2 = 0%, Q-statistic p = 0.53, EGIL I2 = 0%, Q-statistic p = 0.96). CR rates with hybrid induction therapy were not significantly different than those with ALL induction by either definition (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B) and were of borderline significance for higher CR rates compared to AML induction (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D). Meta-analyses of other candidate predictors for CR showed no effect of patient age or MPAL lineage, but in EGIL-defined MPAL, B/My phenotype was associated with greater chance for post-induction remission than T/My (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). In the compiled case series, the majority of patients receiving an ALL induction achieved a CR (n = 150/203, 73.9%). Pediatric patients were more likely than adult patients to begin with ALL therapy (OR = 2.67, 95% CI 1.64–4.35, p < 0.001). However, subsequent multivariable analysis inclusive of treatment type, MPAL definition, age, and lineage found only treatment type and phenotype were associated with a CR (Table 2). After accounting for the impact of phenotype, AML therapy was associated with a lower CR rate than ALL therapy (OR = 0.45 95% CI 0.27–0.77, p = 0.003). Hybrid induction was not significantly different from an ALL induction (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.42–2.17, p = 0.899). Examination of treatment era in the context of this final model suggested a possible increase in CR rate as a function of treatment year (Supplementary Data).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analyses of complete remission rate from ALL or AML induction therapy. Examination of likelihood for obtaining a complete remission when beginning treatment with either ALL or AML induction therapy for MPAL as defined by WHO2008 (a) or EGIL (b). Reference number and sample size as indicated. *, **, *** indicate left, right, or both boundaries extend past figure. C = data reported within detailed case series, S = data reported only as summary/aggregate data

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of patient-level data for complete remission Significance assessed via stepwise logistic regression, see statistical methods for additional detail

| Variable | Category | N | Complete remission | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||||||

| Induction type | ALL | 203 | 150 | 73.9 | Reference | - | - |

| AML | 99 | 53 | 53.5 | 0.45 | 0.27, 0.77 | 0.003 | |

| Hybrid | 40 | 30 | 75 | 0.95 | 0.42, 2.17 | 0.899 | |

| MPAL phenotype | B/My | 185 | 140 | 75.7 | Reference | - | - |

| T/My | 120 | 69 | 57.5 | 0.47 | 0.29, 0.79 | 0.004 | |

| B/T | 21 | 18 | 85.7 | 1.51 | 0.42, 5.53 | 0.525 | |

| B/T/My | 16 | 6 | 37.5 | 0.19 | 0.07, 0.57 | 0.003 | |

Phenotype describes represented lineages: B/My = B + Myeloid, T/My = T + Myeloid, B/T = B + T, B/T/My = B + T + Myeloid ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, hybrid inclusive of components of both ALL and AML therapy

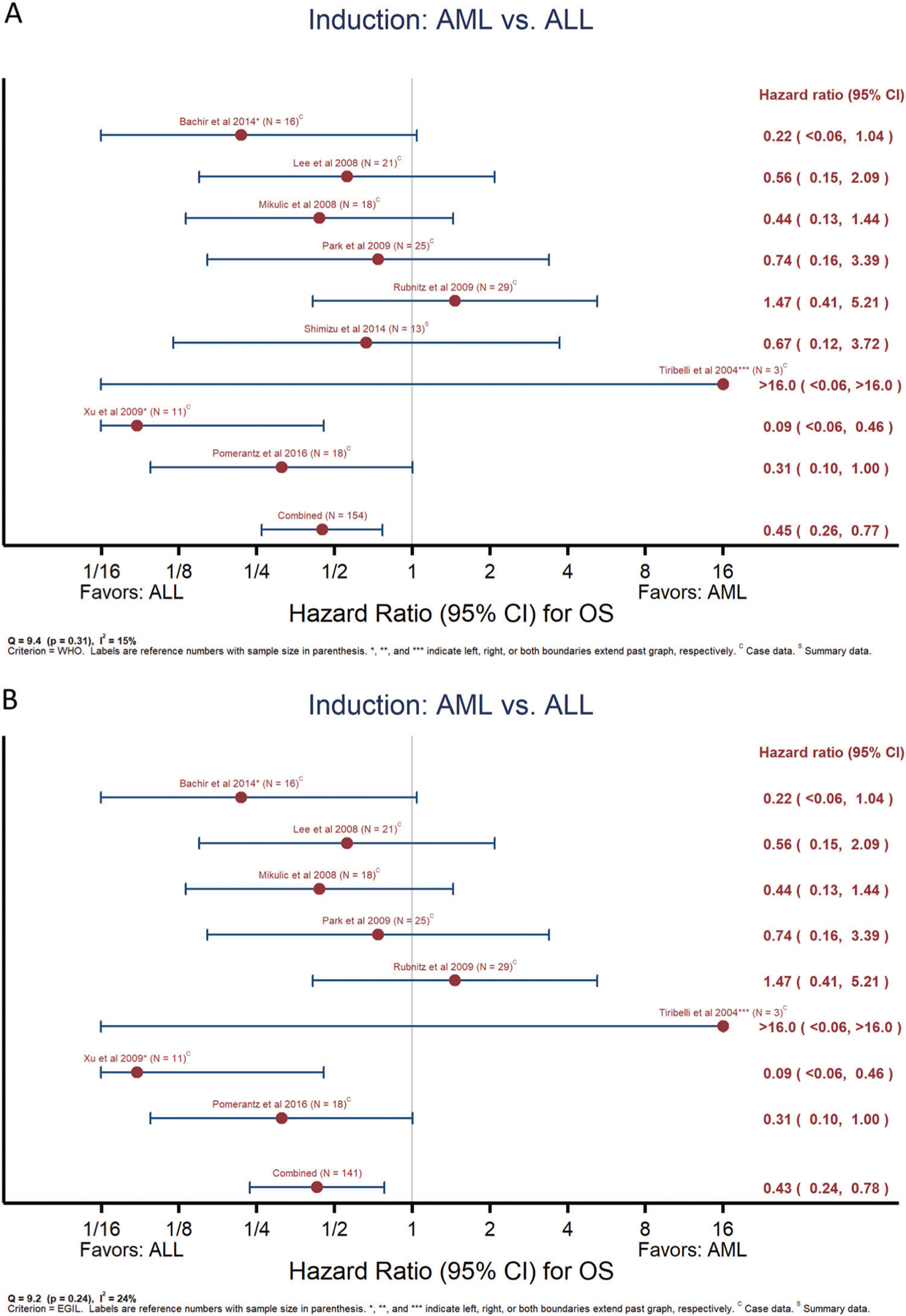

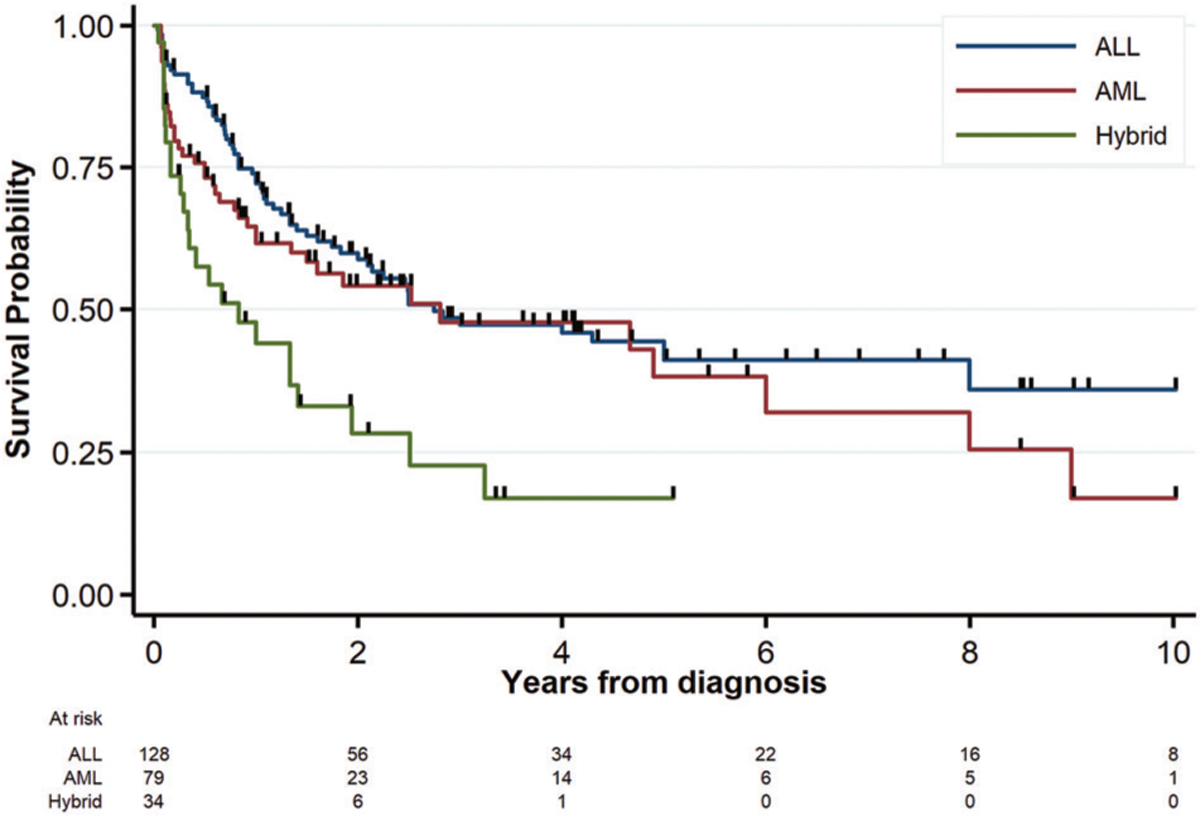

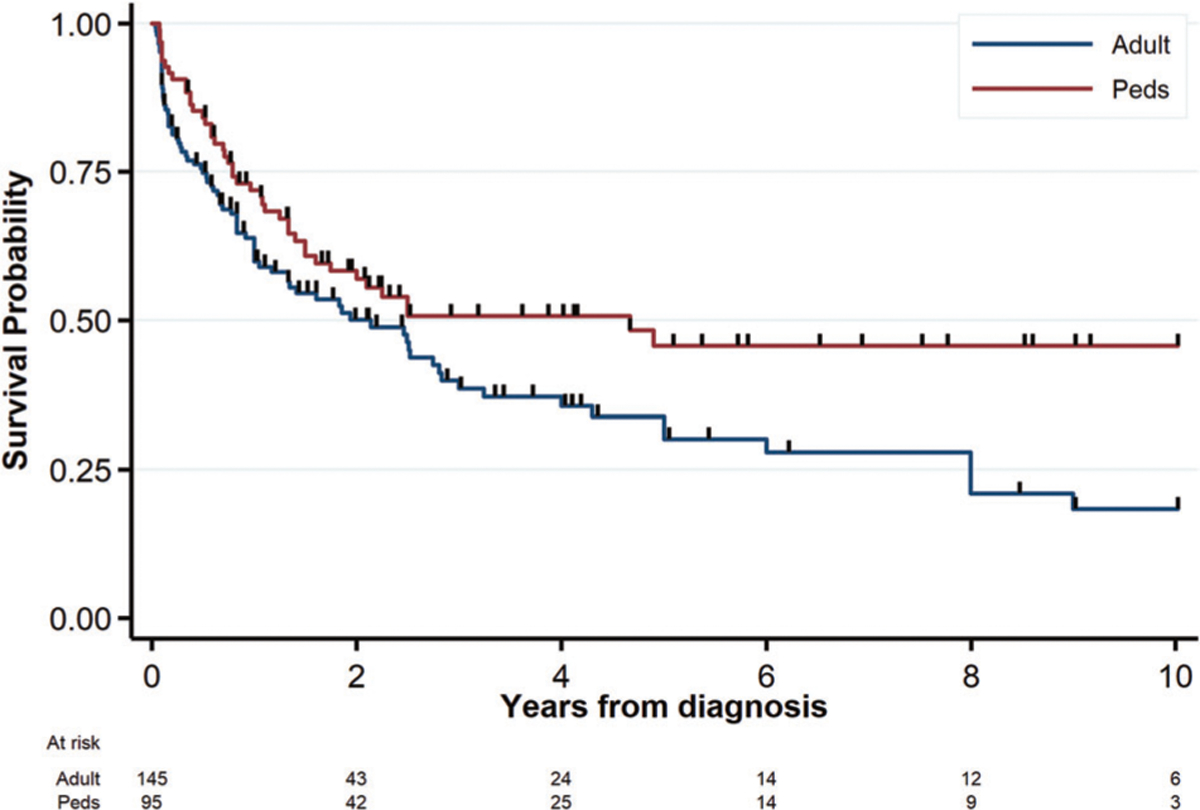

Predictors of OS

Meta-analyses of OS showed a significant survival benefit for starting with ALL therapy as compared to AML, irrespective of definition (Fig. 3a: WHO2008, n = 154, OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.26–0.77; Fig. 4b: EGIL, n = 141, OR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.24–0.78). There was similarly no significant between-study heterogeneity (I2, Q-statistic p-value = 15%, p = 0.31 and 24%, p = 0.24, respectively). Only 11 studies compared outcomes for SCT. The limited data for SCT showed a trend for an association with higher OS for WHO2008-defined MPAL but not EGIL (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). For the compiled case series, 3-year OS for the combined adult and pediatric cohort was 44 ± 3.7%. Examination of the data revealed a large amount of early censoring due to “early” publication; as a sensitivity analysis to determine an “upper boundary’ for potential OS, if publication-censored patients were presumed alive, the maximum 3-year OS would be 52 ± 3.2%. Nonetheless, starting with AML and ALL therapy resulted in similar 3-year OS (47 ± 5.0% and 48 ± 6.9%) as compared to worse survival for starting with hybrid therapy (23 ± 8.6%) (Fig. 4, logrank p = 0.001). On multivariable analysis (Table 3), two models were found to represent the data equally well, one with starting therapy (i.e., induction type) and age (model #1) and the other with starting therapy and lineage (model #2). In both of these multivariable models, starting with either AML or ALL therapy was associated with greater OS as compared to hybrid therapy. Irrespective of age, patients beginning therapy with AML regimens did not experience significantly poorer survival as compared to ALL (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.18, 95% CI 0.79–1.75, p = 0.413) while those receiving hybrid therapy fared worse (HR = 2.11, 95% CI 1.30–3.43, p = 0.003). This effect of starting therapy was also preserved after accounting for MPAL lineage (model #2). Age was predictive of OS on univariable analysis (Fig. 5, logrank p = 0.025) with continued borderline significance in the multivariable model inclusive of starting therapy (pediatric HR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.48–1.00, p = 0.051). Examination of treatment era in the context of the multivariable OS model did not suggest significant improvement as a function of treatment year (see Supplementary Data). SCT could not be included in the multivariable analysis as it is a time-dependent variable with insufficient information reported in most studies as to timing of transplant. However, in examining the patterns of transplant, ~38% of patients in the compiled case series received SCT (n = 101/265), with ~67% of those proceeding to SCT having achieved an early CR (n = 68/101). Patients who started with ALL therapy were less likely to proceed to SCT if they achieved an end of induction CR versus those without CR, while those starting with AML therapy were far more likely to proceed to a SCT with an end induction CR versus no initial CR (ratio of ORs = 4.80, 95% CI 1.49–15.45, p = 0.009).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analyses of overall survival according to starting therapy. Results of meta-analyses comparing overall survival for those beginning treatment with ALL versus AML therapy for MPAL defined by WHO2008 (a) or EGIL (b). Reference number and sample size as indicated. *, **, *** indicate left, right, or both boundaries extend past graph. C = data reported within detailed case series, S = data reported only as summary/aggregate data

Fig. 4.

Overall survival curves according to starting therapy. Comparison of overall survival from diagnosis for patients beginning treatment with ALL, AML, or hybrid therapy in the patient-level compiled case-series

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of patient-level data for overall survival Models developed with stepwise regression using Cox proportional hazards test, both models significant and predictive (p = 0.002 and p = 0.001, respectively); see statistical methods for additional detail

| Model/variable | Category | N | Patient deaths | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||||||

| Multivariable model #1 | |||||||

| Induction type | ALL | 127 | 69 | 54.3 | Reference | - | - |

| AML | 79 | 40 | 50.6 | 1.18 | 0.79, 1.75 | 0.413 | |

| Hybrid | 34 | 24 | 70.6 | 2.11 | 1.30, 3.43 | 0.003 | |

| Age group | Adult | 145 | 89 | 61.4 | Reference | - | - |

| Pediatric | 95 | 44 | 46.3 | 0.69 | 0.48, 1.00 | 0.051 | |

| Multivariable model #2 | |||||||

| Induction Type | ALL | 127 | 69 | 54.3 | Reference | - | - |

| AML | 79 | 40 | 50.6 | 1.41 | 0.93, 2.12 | 0.105 | |

| Hybrid | 34 | 24 | 70.6 | 2.2 | 1.36, 3.56 | 0.001 | |

| Lineage | Bi-P | 19 | 9 | 47.4 | Reference | - | - |

| Bi-L | 93 | 38 | 40.9 | 1.72 | 0.83, 3.56 | 0.148 | |

| Unknown | 128 | 86 | 67.2 | 1.71 | 1.14, 2.57 | 0.009 | |

ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, hybrid inclusive of components of both ALL and AML therapy, Bi-P = Biphenotype, Bi-L = Bi-lineal (more than one distinct blast population)

Fig. 5.

Overall survival curves according to age group. Comparison of overall survival from diagnosis for adult versus pediatric patients treated for MPAL in the patient-level compiled case-series

Discussion

To our knowledge, we present here the results of the first quantitative synthesis for MPAL with over a thousand unique patients with evaluable data included among the different analyses. Due to the relative rarity of MPAL, this represents the largest evaluation to date of therapeutic approaches to treating MPAL. Our principal finding supports the use of an ALL induction regimen as more likely to achieve an initial remission than more toxic AML regimens. Meta-analyses supported the benefit of starting with ALL therapy for OS, but this finding was not replicated in multivariable analysis of the smaller compiled case series. It is unclear if this discrepancy is due to differences in post-induction therapy, variable use of SCT, or other differences not minimized by the large number of patients in the aggregate meta-analyses. Beginning with hybrid therapy showed no consistent difference in the study endpoints across definitions when compared to ALL or AML therapy, but significantly worse survival than either within the compiled cases series. Pending future prospective trials, the consistent trends in the large number of both pediatric and adult patients included here support beginning therapy with less intensive ALL therapy [110]. By analyzing data for both the WHO2008 and EGIL definitions, this finding has broad relevance irrespective of preferred classification system.

The nature of the MPAL literature previously precluded a clear understanding of the presenting characteristics of MPAL. Analysis of this large cohort revealed no specific trends for age, sex, or presenting leukemia features. Of note, while not separated by age group, recurrent leukemia cytogenetic abnormalities were present at rates that were not clearly different from those in the general ALL population. As the first collated description of the prevalence of CNS involvement at diagnosis of MPAL, the relative infrequency of CNS disease is important to note for planning CNS prophylaxis even with the unknown incidence of CNS relapse in MPAL. The relatively low prevalence of BCR-ABL is reassuring, as is the lack of noted toxicity in patients treated with a TKI in support of current expert opinion [6, 110]. We found B/My and Bi-P MPAL to be the most common phenotype and lineage, similar to that reported in an earlier registry study [58]. Understanding the presenting characteristics for MPAL such as the prevalence of CNS involvement, hyperleukocytosis, and cytogenetic abnormalities may help providers guide initial care as well as future research efforts to determine optimal therapy for this population.

While the data supporting improved CR rates with ALL therapy is consistent across all aspects of this quantitative analysis, the impact of therapy type on OS is not as clear. We would note that the poor 3-year OS of <50% demonstrated for patients in the compiled case series may be adversely weighted by the inclusion of older patients (as demonstrated in the multivariable analysis). Two epide-miological studies included for qualitative review, one from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and one from United States Medicare data [107, 108], both support the effect of age on OS. Both studies were hampered by insufficient diagnosis and/or treatment data, but consistently showed elderly patients (≥60 or ≥65 years) diagnosed with MPAL resulted in 2-year OS of less than 20%; the SEER study also showed the highest survival in pediatric patients <20 years of age [107], similar to what we find here. This latter study supports a possible confounding effect of treatment era, with improving survival in MPAL in those treated since 2006, an effect we could not examine [107]. While a benefit for ALL therapy was not observed in the compiled case-series, even equivalent OS might support the use of ALL regimens with reduced treatment intensity and associated acute toxicity and long-term late effects. Comparison of treatment intensity is particularly relevant as the observed 3-year OS in our series included an undetermined effect of SCT, with patients receiving AML therapy far more likely to proceed to intensive SCT even with an early remission. The overall trends seen in our data are consistent with a recent abstract from the iBFM AMBI2012 registry [109]. While the AMBI2012 registry data could not be included in the meta-analyses due to its inclusion of either MPAL classification without specification, and of patients with acute undifferentiated leukemia (AUL), the study generally supported a survival benefit for ALL-based therapy to treat MPAL (5-year EFS ~70%) compared to AML or hybrid regimens (5-year EFS ~40% and ~50%, respectively). Available quantitative and qualitative data thus both support the use of ALL therapy for initial induction, with the preponderance of evidence supporting at least equivalency of long-term outcomes and OS, if not benefit as seen in the meta-analyses.

Conversely, the role of transplant remains a question yet unanswered for MPAL. The meta-analyses show that incorporation of SCT may favor OS, but our analysis is limited through inconsistent reporting for SCT including pre-transplant disease status. Moreover, this apparent association may be an artifact as patients receiving SCT had to survive sufficiently long to receive it. Differences in benefit for SCT between the WHO2008 and EGIL definition are similarly challenging to explain, although the WHO results were likely influenced by the smaller sample size. A recent retrospective study of patients with MPAL treated with SCT by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) [111] lacks data on frontline therapy but describes post-transplant survival for 95 WHO2008-defined MPAL patients. They concluded that transplant was of equal benefit for MPAL as for other acute leukemia. Within the CIBMTR data, transplant in first or second remission did not impact survival, albeit with the caveat this does not include those who did not survive to time of transplant. Preliminary data from the earlier AMBI2012 abstract also describes a potential benefit for SCT, although only in those receiving AML therapy [109]. As such, while SCT likely has utility for treatment of MPAL similar to other acute leukemia, its specific role in frontline versus salvage therapy has yet to be elucidated.

Although this constitutes the largest analysis of MPAL patients in the literature, several limitations inherent to meta-analyses are present in our study. Foremost, this systematic review highlights the absence of high quality prospective studies in MPAL to guide therapy selection. The possibility of a treatment bias from retrospective series cannot be excluded, although this concern is somewhat tempered by the sheer numbers of patients from a wide variety of countries. As is common to all retrospective studies, we cannot entirely exclude unknown interactions between therapy type and leukemia prognosis. While the inclusion of TKI therapy for BCR-ABL + MPAL is now common, we are unable to gauge the efficacy of this approach from the extant literature; it is nonetheless important to note we found no excessive toxicity reported from inclusion of a TKI. Individual recurrent cytogenetic findings were relatively uncommon in the MPAL literature, but beyond those revealed by routinely obtained cytogenetics, this is likely limited by the specific testing sent in each case. Prospective trials with uniform testing at time of diagnosis are necessary to determine the precise prevalence. Both BCR-ABL and KMT2Ar, while less prevalent in MPAL, likely adversely affect OS in MPAL similar to other acute leukemia. Limitations in the primary data precluded evaluating the extent of their influence on CR rates and survival in this study. As a rare disease, data for case series were often presented in abstract form only; we therefore limited inclusion criteria to reports specifically stating their usage of well-established criteria (EGIL or WHO) to mitigate the risk for added heterogeneity in the diagnosis of MPAL. We also acknowledge that the broad search strategy, including unavoidable overlap with terminology for leukemia with rearrangement of the “mixed lineage leukemia” gene, may have resulted in missed isolated case reports during our extensive title review. Nonetheless, we minimized the risk for missing data through independent review by two authors, and we would note our strategy resulted in the inclusion of a very large and international cohort for analysis of a rare leukemia, thereby greatly increasing wide relevance of these findings. Lastly, the aggregate data was too sparse to determine the impact of post-induction therapy with or without SCT on survival. While the meta-analyses of data for EGIL and WHO2008 MPAL are strongly suggestive of benefit for beginning treatment using ALL therapy, the lack of prospective trial data and the absence of clear improvement in treatment outcomes over the years highlight the need for prospective trials to validate these findings and to explore the role of response-based risk stratification and SCT to determine optimal therapy for MPAL.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0058-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Weinberg OK, Arber DA. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia: historical overview and a new definition. Leukemia. 2010;24 (11):1844–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bene MC, Castoldi G, Knapp W, Ludwig WD, Matutes E, Orfao A, et al. Proposals for the immunological classification of acute leukemias. European Group for the Immunological Characterization of Leukemias (EGIL). Leukemia. 1995;9 (10):1783–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matutes E, Morilla R, Farahat N, Carbonell F, Swansbury J, Dyer M, et al. Definition of acute biphenotypic leukemia. Haematologica. 1997;82(1):64–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. World Health Organization classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114 (5):937–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aasha B, Sharma S, Rai P, Chauhan R, Chandra J. A girl with mixed phenotype acute leukemia: B/T subtype-a rare variant. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2013;29(4):331. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdulwahab AS, AlJurf MD, Elkum NM, Almohareb FI, Owaidah TM. Clinical presentation, treatment response and survival in adult acute biphenotypic leukemia: single centre experience. Blood. 2007;110(11):150B–150B. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhuraiji A, Shad A, Owaidah T, Alzahrani H, Al Mhareb F, Chaudhri N et al. Efficacy and safety of VCEP-M for induction treatment of mixed phenotypic acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15_suppl):e18504. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Qurashi FH, Owaidah T, Iqbal MA, Aljurf M. Trisomy 4 as the sole karyotypic abnormality in a case of acute biphenotypic leukemia with T-lineage markers in minimally differentiated acute myelocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;150 (1):66–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Seraihy AS, Owaidah TM, Ayas M, El-Solh H, Al-Mahr M, Al-Ahmari A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with biphenotypic acute leukemia. Haematologica. 2009;94(12):1682–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarado Y, Welch MA, Swords R, Bruzzi J, Schlette E, Giles FJ. Nelarabine activity in acute biphenotypic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2007;31(11):1600–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atfy M, Al Azizi NMA, Elnaggar AM. Incidence of Philadelphia-chromosome in acute myelogenous leukemia and biphenotypic acute leukemia patients: and its role in their outcome. Leuk Res. 2011;35(10):1339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachir F, Zerrouk J, Howard SC, Graoui O, Lahjouji A, Hessissen L, et al. Outcomes in patients with mixed phenotype acute leukemia in Morocco. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;36(6): e392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhamidipati PK, Jabbour E, Konoplev S, Estrov Z, Cortes J, Daver N. Epstein-Barr Virus induced CD30-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a patient with mixed-phenotypic leukemia treated with Clofarabine. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13(3):342–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia P, Binota J, Varma N, Marwaha RK, Varma S. A study on the expression of BCR-ABL transcript in mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) cases using the reverse transcriptase polymerase reaction assay (RT-PCR) and its correlation with hematological remission status post induction. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2011;27(4):196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhella SD, Musani R, Porwit A, Tierens A, Gupta V, Schimmer AD, et al. Outcomes of mixed phenotype leukemia, not otherwise specified (NOS), in adults: a single centre retrospective review from 2000 to 2014. Blood. 2015;126(23):4865. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bleahu ID, Vladasel R, Gheorghe A. A special case of acute leukemia in childhood. J Med Life. 2012;4(3):297–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogunovic M, Kraguljac-Kurtovic N, Bogdanovic A, Perunicic M, Djordjevic V, Lazarevic V, et al. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) according to the who 2008 classification-report of 17 cases. Haematologica. 2011;96:240–1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butcher BW, Wilson KS, Kroft SH, Collins RH Jr, Bhushan V. Acute leukemia with B-lymphoid and myeloid differentiation associated with an inv(5)(q13q33) in an adult patient. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;157(1):62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colovic M, Colovic N, Jankovic G, Kurtovic NK, Vidovic A, Djordjevic V. et al. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia of T/myeloid type with a prominent cellular heterogeneity and unique karyotypic aberration 45,XY, dic(11;17). Int J Lab Hematol. 2012;34(3):290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Leeuw DC, van den Ancker W, Westers TM, Loonen AH, Bhola SL, Ossenkoppele GJ, et al. Challenging diagnosis in a patient with clear lymphoid immunohistochemical features and myeloid morphology: mixed phenotype acute leukemia with erythrophagocytosis. Leuk Res. 2011;35(5):693–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deffis-Court M, Alvarado-Ibarra M, Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Rosas-Lopez A, Barrera-Lumbreras G, Aguayo-Gonzalez A, et al. Diagnosing and treating mixed phenotype acute leukemia: a multicenter 10-year experience in Mexico. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(4):595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derwich K, Sedek L, Meyer C, Pieczonka A, Dawidowska M, Gaworczyk A, et al. Infant acute bilineal leukemia. Leuk Res. 2009;33(7):1005–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duployez N, Debarri H, Fouquet G. Mixed phenotype acute leukaemia with Burkitt-like cells and positive peroxidase cytochemistry. Br J Haematol. 2013;163(2):148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferla V, Vincenti D, Fracchiolla NS, Cro L, Cortelezzi A. A rare case of mixed phenotype acute leukemia, T/myeloid, nos: Diagnosis, therapy and clinical outcome. Haematologica. 2013;98:208.22875615 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaipa G, Leani V, Maglia O, Benetello A, Cantu-Rajnoldi A, Bugarin C, et al. Four pediatric acute biphenotypic leukemia cases: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Cytom Part A. 2006;69A(5):451–451. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao H, Liu Y, Zhang R, Xie J, Shi H, Wu M et al. Pediatric mixed phenotype acute leukemia-41 cases report. Blood. 2012; 120(21):4811. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerr H, Zimmermann M, Schrappe M, Dworzak M, Ludwig WD, Bradtke J, et al. Acute leukaemias of ambiguous lineage in children: characterization, prognosis and therapy recommendations. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(1):84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Getta BM, Zheng J, Tallman MS, Park JH, Stein EM, Roshal M et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant with ablative conditioning is associated with favorable outcomes in patients with mixed phenotype acute leukemia clinical allogeneic transplantation. Blood 2016;128(22):3487. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gozzetti A, Calabrese S, Raspadori D, Crupi R, Tassi M, Bocchia M, et al. Concomitant t(4;11) and t(1;19) in a patient with biphenotypic acute leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;177(1):81–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guariglia R, Guastafierro S, Annunziata S, Tirelli A. Development of a transient monoclonal gammopathy after chemotherapy in a patient with biphenotypic acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(2):441–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gujral S, Polampalli S, Badrinath Y, Kumar A, Subramanian PG, Raje G, et al. Clinico-hematological profile in biphenotypic acute leukemia. Indian J Cancer. 2009;46(2):160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He G, Zhou L, Wu D, Xue Y, Zhu M, Liang J, et al. Clinical research of biphenotypic acute leukemia with t(8;21)(q22; q22). Chin-Ger J Clin Oncol. 2007;6(4):389–92. [Google Scholar]

- 37.He G, Wu D, Sun A, Xue Y, Jin Z, Qiu H, et al. B-Lymphoid and myeloid lineages biphenotypic acute leukemia with t(8;21) (q22; q22). Int J Hematol. 2008;87(2):132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heesch S, Neumann M, Schwartz S, Bartram I, Schlee C, Burmeister T, et al. Acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage in adults: molecular and clinical characterization. Ann Hematol. 2013;92 (6):747–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaćanski N, Konstantinidis N, Kolarović J, Slavković B, Vujić D. Biphenotypic acute leukaemia: case reports of two paediatric patients. Med Pregl. 2010;63(11–12):867–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalashetty M, Dalal BI, Roland KJ, Abou Mourad Y, Barnett MJ, Broady R, et al. Improved survival in adults with mixed-phenotype acute leukemia following stem cell transplantation (SCT): a single centre experience. Blood. 2013;122(21):5540. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawajiri C, Tanaka H, Hashimoto S, Takeda Y, Sakai S, Takagi T, et al. Successful treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive mixed phenotype acute leukemia by appropriate alternation of second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors according to BCR-ABL1 mutation status. Int J Hematol. 2014;99(4):513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khodadoust MS, Luo B, Medeiros BC, Johnson RC, Ewalt MD, Schalkwyk AS, et al. Clinical activity of ponatinib in a patient with FGFR1-rearranged mixed-phenotype acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(4):947–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Killick S, Matutes E, Powles RL, Hamblin M, Swansbury J, Treleaven JG, et al. Outcome of biphenotypic acute leukemia. Haematologica. 1999;84(8):699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim HN, Hur M, Kim H, Ji M, Moon HW, Yun YM, et al. First case of biphenotypic/bilineal (B/myeloid, B/monocytic) mixed phenotype acute leukemia with t(9;22) (q34; q11.2);BCR-ABL1. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46(4):435–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohla SA, Sabbagh AA, Omri HE, Ibrahim FA, Otazu IB, Alhajri H, et al. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia with two immunophenotypically distinct B and T blasts populations, double Ph (+) chromosome and complex karyotype: report of an unusual case. Clin Med Insights Blood Disord. 2015;8: 25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnan AY, Chang KL, Fung HC, O’Donnell M, Bhatia R, Spielberger R, et al. Impact of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) on outcome of biphenotypic acute leukemia (BAL). Blood. 2004;104(11):370B [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JH, Min YH, Chung CW, Kim BK, Yoon HJ, Jo DY, et al. Prognostic implications of the immunophenotype in biphenotypic acute leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(4):700–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JY, Lee SM, Lee JY, Kim KH, Choi MY, Lee WS. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia treated with decitabine. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31(2):406–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S, Jung CW, Song SY, Park JO, Kim K, Kim WS, et al. The effect of ffigh dose cytarabine and idarubicin as an induction therapy in biphenotypic acute leukemia. Blood. 2002;100 (11):264B [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim F, Wong GC. Biphenotypic acute leukaemia: treatment with all-type regime may offer a better outcome. Haematolgica. 2010;95:273–273. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu QF, Fan ZP, Wu MQ, Sun J, Wu XL, Xu D, et al. Allo-HSCT for acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage in adults: the comparison between standard conditioning and intensified conditioning regimens. Ann Hematol. 2013;92(5):679–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopes GS, Leitao JP, Kaufman J, Duarte FB, Matos DM. T-cell/myeloid mixed-phenotype acute leukemia with monocytic differentiation and isolated 17p deletion. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2014;36(4):293–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lou ZJ, Zhang CC, Tirado CA, Slone T, Zheng J, Zaremba CM, et al. Infantile mixed phenotype acute leukemia (bilineal and biphenotypic) with t(10;11)(p12; q23);MLL-MLLT10. Leuk Res. 2010;34(8):1107–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu J, Ashwani N, Zhang M, He H, Wang Y, Zhao W, et al. Children diagnosed as mixed-phenotype acute leukemia didn’t benefit from the CCLG-2008 protocol, retrospective analysis from single center. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;31 (1):32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manola KN, Georgakakos VN, Marinakis T, Stavropoulou C, Paterakis G, Anagnostopoulos NI, et al. Translocation (X;12) (p11; p13) as a sole abnormality in biphenotypic acute leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;173(2):159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marques-Salles Tde J, Barros JE, Soares-Ventura EM, Cartaxo Muniz MT, Santos N, Ferreira da Silva E, et al. Unusual childhood biphenotypic acute leukemia with a yet unreported t(3;13) (p25.1; q13). Leuk Res. 2010;34(8):e206–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsumoto Y, Taki T, Fujimoto Y, Taniguchi K, Shimizu D, Shimura K, et al. Monosomies 7p and 12p and FLT3 internal tandem duplication: possible markers for diagnosis of T/myeloid biphenotypic acute leukemia and its clonal evolution. Int J Hematol. 2009;89(3):352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matutes E, Pickl WF, Van’t Veer M, Morilla R, Swansbury J, Strobl H, et al. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia: clinical and laboratory features and outcome in 100 patients defined according to the WHO 2008 classification. Blood. 2011;117 (11):3163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mejstrikova E, Volejnikova J, Fronkova E, Zdrahalova K, Kalina T, Sterba J, et al. Prognosis of children with mixed phenotype acute leukemia treated on the basis of consistent immunophenotypic criteria. Haematologica. 2010;95(6):928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mejstrikova E, Slamova L, Fronkova E, Volejnikova J, Muzikova K, Domansky J et al. Acute bilineal leukemia is a very rare entity in childhood. Blood 2011;118(21):4871. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mikulic M, Batinic D, Sucic M, Davidovic-Mrsic S, Dubravcic K, Nemet D, et al. Biological features and outcome of biphenotypic acute leukemia: a case series. Hematol Oncol stem Cell Ther. 2008;1(4):225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miyazawa Y, Irisawa H, Matsushima T, Mitsui T, Uchiumi H, Saitoh T, et al. Der(2)t(2; 11)(p21; q23), a variant form of t(2; 11), in biphenotypic acute leukemia with T lymphoid lineage and myeloid lineage differentiation. Kitakanto Med J. 2012;62 (3):287–90. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moraveji S, Torabi A, Nahleh Z, Farrag S, Gaur S. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage with trisomy 4 as the sole cytogenetic abnormality: a case report and literature review. Leuk Res Rep. 2014;3(2):33–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moreira C, Domingues N, Moreira I, Oliveira I, Martins A, Viterbo L, et al. Adult mixed-phenotype acute leukemia according to the who 2008 classification-a single center experience. Haematologica. 2013;98:267. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mori J, Ishiyama K, Yamaguchi T, Tanaka J, Uchida N, Kobayashi T, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with biphenotypic acute leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(2):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Munker R, Brazauskas R, Wang HL, de Lima M, Khoury HJ, Gale RP, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients with mixed phenotype acute leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(6):1024–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naghashpour M, Lancet J, Moscinski L, Zhang L. Mixed phenotype acute leukemia with t(11;19)(q23; p13.3)/ MLL-MLLT1 (ENL), B/T-lymphoid type: a first case report. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(6):451–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishiuchi T, Ohnishi H, Kamada R, Kikuchi F, Shintani T, Waki F, et al. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage, biphenotype, without CD34, TdT or TCR-rearrangement. Intern Med. 2009;48 (16):1437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oka S, Yokote T, Akioka T, Hara S, Kobayashi K, Hirata Y, et al. Trisomy 21 as the sole acquired karyotypic abnormality in biphenotypic acute leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2007;85(3): 270–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oliveira JL, Kumar R, Khan SP, Law ME, Erickson-Johnson M, Oliveira AM, et al. Successful treatment of a child with T/myeloid acute bilineal leukemia associated with TLX3/BCL11B fusion and 9q deletion. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(3):467–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orgel E, Oberley M, Li S, Malvar J, O’Gorman M. Predictive value of minimal residual disease in WHO2016-defined mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL). Blood. 2016;128(22):178.27106121 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Otsubo K, Yabe M, Yabe H, Fukumura A, Morimoto T, Kato M, et al. Successful acute lymphoblastic leukemia-type therapy in two children with mixed-phenotype acute leukemia. Pediatr Int: Off J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2016;58(10):1072–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park JA, Ghim TT, Bae K, Im HJ, Jang SS, Park CJ, et al. Stem cell transplant in the treatment of childhood biphenotypic acute leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(3):444–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park JA, Lee JM, Lee KS, Kim JY, Lim JY, Park ES, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for pediatric mixed phenotype acute leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51: S596–7. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Patel B, Saygin C, Przychodzen BP, Hirsch CM, Clemente MJ, Hamilton BK, et al. Molecular and immunophenotypic characteristics of adult acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage. Blood 2016;128(22). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rahman K, George S, Tewari A, Mehta A. Mixed phenotypic acute leukemia with two immunophenotypically distinct blast populations: report of an unusual case. Cytom B Clin Cytom. 2013;84(3):198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ratei R, Schabath R, Karawajew L, Zimmermann M, Moricke A, Schrappe M, et al. Lineage classification of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia according to the EGIL recommendations: results of the ALL-BFM 2000 trial. Klin Padiatr. 2013;225 (Suppl 1):S34–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rubio MT, Dhedin N, Boucheix C, Bourhis JH, Reman O, Boiron JM, et al. Adult T-biphenotypic acute leukaemia: clinical and biological features and outcome. Br J Haematol. 2003;123 (5):842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rubnitz JE, Onciu M, Pounds S, Shurtleff S, Cao X, Raimondi SC, et al. Acute mixed lineage leukemia in children: the experience of St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Blood. 2009;113(21):5083–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saito M, Izumiyama K, Mori A, Irie T, Tanaka M, Morioka M, et al. Biphenotypic acute leukemia with t(15;17) lacking promyelocytic-retinoid acid receptor α rearrangement. Hematol Rep. 2013;5(4):50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saitoh T, Matsushima T, Iriuchishima H, Yamane A, Irisawa H, Handa H, et al. Presentation of extramedullary Philadelphia chromosome-positive biphenotypic acute leukemia as testicular mass: response to imatinib-combined chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(12):2667–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scolnik MP, Aranguren PN, Cuello MT, Palacios MF, Sanjurjo J, Giunta M, et al. Biphenotypic acute leukemia with t(15;17). Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46(4):607–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Serefhanoglu S, Buyukasik Y, Goker H, Sayinalp N, Ozcebe OI. Biphenotypic acute leukemia treated with acute myeloid leukemia regimens: a case series. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101 (3):270–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shao-Yan H, Jing L, Zhenghua J, Yaxiang H, Yiping H. The clinical features and laboratory findings of mixedphenotype acute leukemia in 15 children-retrospective analysis from single center during 2008–12. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013; 60:75. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sharma P, Lall M, Jain P, Saraf A, Sachdeva A, Bhargava M. A bi-lineal acuteleukemia (T/Myeloid, NOS) with complex cytogenetic abnormalities. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;29 (2):119–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimizu H, Saitoh T, Machida S, Kako S, Doki N, Mori T, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult patients with mixed phenotype acute leukemia: results of a matched-pair analysis. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95(5):455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shimizu H, Yokohama A, Hatsumi N, Takada S, Handa H, Sakura T, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-positive mixed phenotype acute leukemia in the imatinib era. Eur J Haematol. 2014;93(4):297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steiner M, Attarbaschi A, Dworzak M, Strobl H, Pickl W, Kornmüller R, et al. Cytochemically myeloperoxidase positive childhood acute leukemia with lymphoblastic morphology treated as lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32(1):e4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takata H, Ikebe T, Sasaki H, Miyazaki Y, Ohtsuka E, Saburi Y, et al. Two elderly patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive mixed phenotype acute Leukemia who were successfully treated with Dasatinib and Prednisolone. Intern Med. 2016;55 (9):1177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tarsitano M, Leszl A, Parasole R, Cavaliere ML, Menna G, Di Meglio A, et al. Trisomy 7 and deletion of the 9p21 locus as novel acquired abnormalities in a case of pediatric biphenotypic acute leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(3): e126–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tassano E, Tavella E, Micalizzi C, Scuderi F, Cuoco C, Morerio C. Monosomal complex karyotype in pediatric mixed phenotype acute leukemia. Cancer Genet. 2011;204(9): 507–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tian H, Xu Y, Liu L, Yan L, Jin Z, Tang X, et al. Comparison of outcomes in mixed phenotype acute leukemia patients treated with chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation versus chemotherapy alone. Leuk Res. 2016;45:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tiribelli M, Damiani D, Masolini P, Candoni A, Calistri E, Fanin R. Biological and clinical features of T-biphenotypic acute leukaemia: report from a single centre. Br J Haematol. 2004;125 (6):814–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Udayakumar AM, Pathare AV, Alkindi S, Raeburn JA. Biphenotypic leukemia with interstitial del(9)(q22q32) as a sole abnormality. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;178(2):170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vardhan R, Kotwal J, Ganguli P, Ahmed R, Sharma A, Singh J. Mixed phenotypic acute leukemia presenting as mediastinal mass-2 cases. Indian J Hematol & Blood Transfus: Off J Indian Soc Hematol Blood Transfus. 2016;32(Suppl 1):72–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang Y, Gu M, Mi YC, Qiu LG, Bian SG, Wang JX. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of mixed phenotype acute leukemia with Philadelphia chromosome positive and/or bcr-abl positive in adult. Int J Hematol. 2011;94(6):552–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xu XQ, Wang JM, Lu SQ, Chen L, Yang JM, Zhang WP, et al. Clinical and biological characteristics of adult biphenotypic acute leukemia in comparison with that of acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case series of a Chinese population. Haematologica. 2009;94(7):919–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yan LZ, Ping NN, Zhu MQ, Sun AN, Xue YQ, Ruan CG, et al. Clinical, immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic features in 117 adult patients with mixed-phenotype acute leukemia defined by WHO-2008 classification. Haematol Hematol J. 2012;97(11):1708–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang YM, Wu DP, Sun AN, Qiu HY, He GS, Jin ZM, et al. Clinical characteristics, biological profile, and outcome of biphenotypic acute leukemia: a case series. Acta Haematol. 2011;125(4):210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zucchini A, Fattori PP, Lanza F, Ferrari L, Bagli L, Imola M, et al. Biphenotypic acute leukemia: a case report. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2004;18(3–4):387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Costa ES, Thiago LS, Otazu IB, Ornellas MH, Land MG, Orfao A. An uncommon case of childhood biphenotypic precursor-B/T acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50 (4):941–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Darwish A, Samra M, Alsharkawy N, Gaber O. Adult biphenotypic acute leukemia: The Egyptian National Cancer Institute experience. Haematologica. 2016;101:680–1.27252513 [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pawar RN, Banerjee S, Bramha S, Krishnan S, Bhattacharya A, Saha V, et al. Mixed-phenotypic acute leukemia series from tertiary care center. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2017;60(1): 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pomerantz A, Rodriguez-Rodriguez S, Demichelis-Gomez R, Barrera-Lumbreras G, Barrales-Benitez O, Lopez-Karpovitch X, et al. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia: suboptimal treatment when the 2008/2016 WHO classification is used. Blood Res. 2016;51(4):233–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dai H, Zhang W, Li X, Han Q, Guo Y, Zhang Y, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of autologous or donor-derived T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors in adult B-ALL with extramedullary leukemia. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(11): e1027469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yao L, Cen J, Pan J, Liu D, Wang Y, Chen Z, et al. TAF15–ZNF384 fusion gene in childhood mixed phenotype acute leukemia. Cancer Genet. 2017;211:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shi R, Munker R. Survival of patients with mixed phenotype acute leukemias: a large population-based study. Leuk Res. 2015;39(6):606–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guru Murthy GS, Dhakal I, Lee JY, Mehta P. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage in elderly patients—analysis of survival using surveillance epidemiology and end results-medicare database. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(2):100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hrusak O, Haas VD, Luks A, Janotova I, Mejstrikova E, Bleckmann K et al. Acute leukemia of ambiguous lineage: a comprehensive survival analysis enables designing new treatment strategies. Blood. 2016;128(22):584.27317792 [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wolach O, Stone RM. How I treat mixed-phenotype acute leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(16):2477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Munker R, Wang HL, Brazauskas R, Saber W, Weisdorf DJ. Allogeneic transplant for acute biphenotypic leukemia: characteristics and outcome in the CIBMTR database. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(2):S83 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.