The glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis inhibitor gepinacin demonstrates broad-spectrum antifungal activity and negligible mammalian toxicity in culture but is metabolically labile. The stability and bioactivity of 39 analogs were tested in vitro to identify LCUT-8, a stabilized lead with increased potency and promising single-dose pharmacokinetics. Unfortunately, no antifungal activity was seen at the maximum dosing achievable in a neutropenic rabbit model. Nevertheless, structure-activity relationships identified here suggest strategies to further improve compound potency, solubility, and stability.

KEYWORDS: glycosylphosphatidylinositol, Gwt1, candidiasis, microsome metabolism, structure-activity relationship

ABSTRACT

The glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis inhibitor gepinacin demonstrates broad-spectrum antifungal activity and negligible mammalian toxicity in culture but is metabolically labile. The stability and bioactivity of 39 analogs were tested in vitro to identify LCUT-8, a stabilized lead with increased potency and promising single-dose pharmacokinetics. Unfortunately, no antifungal activity was seen at the maximum dosing achievable in a neutropenic rabbit model. Nevertheless, structure-activity relationships identified here suggest strategies to further improve compound potency, solubility, and stability.

TEXT

Despite best-available treatments, invasive fungal infections have mortality rates of 30% to 90%, depending on host comorbidities and the specific fungal pathogen (1–3). Immunocompromised patients, who are at particular risk for these infections, include individuals receiving immunosuppressive chemotherapeutic agents and corticosteroids, as well as those infected with HIV or suffering from autoimmune or metabolic disorders (4–7). All current antifungal treatments are limited to varied degrees by systemic toxicity/tolerability, restricted spectrum of activity, and the emergence of drug resistance (8); this necessitates the development of new, more effective antifungal drugs.

Targeting glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchoring of cell surface proteins is emerging as a promising strategy to treat invasive fungal infections (9, 10). Addition of GPI anchors is a posttranslational modification of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of eukaryotes. GPI anchors mediate trafficking of proteins to the Golgi apparatus and eventually tether them to the plasma membrane (11). GPI anchor biosynthesis inhibitors are selectively toxic to fungi because GPI-anchored proteins are integral to the structure of the fungal cell wall (9, 11). Furthermore, it has proven possible to design compounds that target the fungal pathway with high selectivity due to evolutionary divergence between fungal and mammalian GPI anchor biosynthesis enzymes (9).

Within the GPI anchor synthesis pathway, the acyltransferase Gwt1 is the best-understood target of small-molecule inhibitors in development as antifungal drugs. Inhibition of Gwt1 results in the accumulation of immature GPI proteins in the ER, induces the unfolded protein stress response, and exposes immunogenic (1→3)-β-d-glucans at the fungal cell surface (12). The Gwt1 inhibitor fosmanogepix (formerly APX001, E1211; prodrug of manogepix, E1210) is showing promise in advanced clinical trials for the treatment of invasive mycoses (13–15). Gepinacin is a preclinical Gwt1 inhibitor that is structurally distinct from manogepix (12, 16). Neither manogepix nor gepinacin inhibits the orthologous mammalian acyltransferase PIG-W, and both have broad-spectrum activity against diverse fungal pathogens (12, 15).

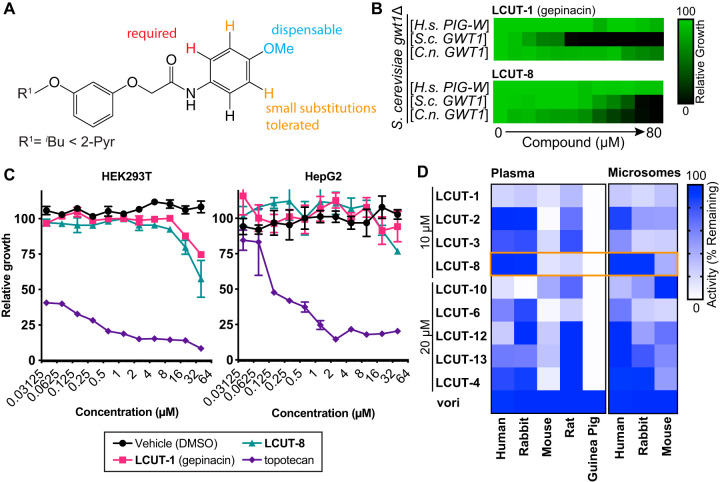

Unlike that of manogepix, the activity of gepinacin has been demonstrated only in vitro (12), because the compound is labile to serum and liver microsomal metabolism in vitro (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), including hydrolysis of its methoxy substituent and cleavage of the amide linkage (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To identify compounds with greater stability, we began by testing a collection of 39 structural analogs for antifungal activity. Eight of these compounds possessed MIC50 values of ≤20 μM for Candida albicans (SC5314/ATCC MYA-2876) (17) (Table 1), as determined by broth microdilution assay according to CLSI standards (18). These compounds also maintained broad-spectrum activity against the fungal pathogens Candida auris (Ci 6684) (19), Cryptococcus neoformans (H99/ATCC 208821) (20), Candida glabrata (BG2) (21), and the model fungus Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S288c) (22) (Table 1; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis suggested that the labile methoxy substituent is not required for antifungal activity and can be replaced with smaller (CH3, F, Cl, H) but not larger (CF3, OCF3, tBu) groups (Fig. 1A, Table 1). Replacement of the aryl group of the anilide by a pyridyl substituent increased potency for C. albicans, C. auris, and C. neoformans but resulted in loss of potency against C. glabrata and S. cerevisiae isolates (Fig. 1A, Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Structure-activity relationship for gepinacin analogs with antifungal activity

| Compound | R1 | R2 | ClogPa | MIC50 (μM)b against: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. auris | C. neoformans | C. glabrata | S. cerevisiae | ||||

| LCUT-1 (gepinacin) | A |  |

3.97 | 5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 |

| LCUT-2 | B |  |

3.20 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| LCUT-3 | A |  |

2.88 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 | 5 |

| LCUT-4 | B |  |

2.10 | 10 | 10 | 40 | 20 | >40 |

| LCUT-5 | A |  |

4.55 | 5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 40 | >40 |

| LCUT-6 | A |  |

4.20 | 5 | 0.625 | 2.5 | 10 | 20 |

| LCUT-7 | A |  |

4.77 | 10 | 0.625 | 2.5 | >40 | >40 |

| LCUT-8 | B |  |

1.78 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 40 | >40 |

| LCUT-9 | B |  |

3.28 | 40 | 20 | 20 | >40 | >40 |

| LCUT-10 | A |  |

4.30 | 2.5 | 0.625 | >40 | 2.5 | 5 |

| LCUT-11 | A |  |

4.55 | >40 | 10 | 10 | >40 | >40 |

| LCUT-12 | A |  |

3.85 | 20 | 1.25 | 5 | 20 | 10 |

| LCUT-13 | B |  |

3.07 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

ClogP, calculated logarithm of the partition coefficient between n-octanol and water log(coctanol/cwater) (BioByte).

Dose-response assays were performed by broth microdilution in RPMI 1640 medium, and MIC50s were determined by OD600 at 50% growth inhibition after 24 h of incubation at 30°C. Data were consistent in 3 independent experiments.

FIG 1.

Gepinacin analogs are selective for fungal Gwt1, nontoxic to mammalian cells, and have improved in vitro metabolic stability. (A) Summary of SAR for gepinacin scaffold based on activity of compounds in Table 1 and Table S1 against C. albicans. (B) Gepinacin analogs are specific inhibitors of fungal Gwt1. Gepinacin analogs did not inhibit growth of S. cerevisiae harboring a centromeric plasmid encoding the Homo sapiens ortholog of Gwt1, PIG-W. Relative to gepinacin, LCUT-8 had reduced potency against S. cerevisiae Gwt1 and improved potency against C. neoformans Gwt1. Growth was monitored by OD600 and normalized to drug-free control wells. Dose-response assays for 2-fold dilution series of LCUT-1 (gepinacin) and LCUT-8 in RPMI medium are shown. Data presented are means of 3 independent experiments performed in technical duplicate. (C) Gepinacin analogs had minimal impact on the growth/survival of mammalian cell lines HEK293T or HepG2. Relative viable cell number was monitored by alamarBlue reduction after 48 h of incubation in the presence of a 2-fold dilution series of compounds. Data are means ± SEM for triplicate cultures, normalized to drug-free controls. (D) LCUT-8 exhibits reduced susceptibility to metabolism by plasma and liver microsomes derived from humans and rabbits (highlighted in orange box). Compounds were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with plasma or microsomes (0.5 mg/ml protein) with an NADPH-regenerating system, then diluted 1:4 in RPMI medium previously inoculated with C. albicans. Labels indicate nominal compound concentrations present in cultures assuming no metabolism. Voriconazole (vori) was included as a stable antifungal control at 64 ng/ml. Cultures were incubated at 30°C for 24 h, then fungal growth was assessed by alamarBlue reduction. Data are means of remaining inhibitory activity for 3 independent experiments performed in technical quadruplicate.

Target specificity of all 13 active analogs was confirmed by dose-response assays using strains of S. cerevisiae where endogenous GWT1 was deleted and replaced with centromeric plasmid-encoded human PIG-W, S. cerevisiae GWT1, or C. neoformans GWT1 (12). Gepinacin and LCUT-8 did not inhibit growth of S. cerevisiae isolates expressing human PIG-W (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, LCUT-8 was less potent against S. cerevisiae Gwt1 but more potent against C. neoformans Gwt1 than gepinacin (Fig. 1B).

Importantly, the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for these compounds against both HepG2 and HEK293T human cell lines were >40 μM (Fig. 1C). This finding suggested low human toxicity potential at concentrations greatly exceeding those required for antifungal activity in vitro (e.g., C. albicans LUCT-8 MIC50, 1.25 μM) (Table 1). For IC50 tests, 96-well plates were seeded with 1.25 × 104 cells in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, and then 100 μl of fresh medium containing a dilution series of compound was added. The cytotoxic topoisomerase I inhibitor topotecan was included as a positive control. After 48 h, relative viable cell number was assessed by measuring alamarBlue (Invitrogen) fluorescence at 530/590 nm (excitation/emission).

Having confirmed their potent and selective antifungal activity, we evaluated compounds for antifungal activity after incubation in plasma and liver microsome preparations derived from humans and prospective animal models. Replacement of gepinacin’s isobutyl substituent with 2-pyridyl (LCUT-2) or replacement of the aryl group of the anilide by a pyridyl substituent (LCUT-3, LCUT-4) improved stability in human and rabbit plasma samples (Fig. 1D). LCUT-8 combines these alterations and further removes the labile methoxy substituent; activity of LCUT-8 was stable in plasma and microsome samples from both humans and rabbits (Fig. 1D). For these assays, compounds were incubated in citrated plasma (25% in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) or animal liver microsomes (0.5 mg/ml protein) and an NADPH-regenerating system (Xenotech L1500, lot 1010273; M5000, lot 1710080; M0620, lot 1610016; and K5100). Each compound was assayed at the concentration required for it to inhibit fungal growth by ∼90% before metabolism, relative to vehicle controls. Voriconazole 64 ng/ml was included as a metabolically stable antifungal control. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then stopped by addition of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride to 1 mM. After 30 min incubation, reactions were diluted 1:4 in MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-buffered RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% glucose and C. albicans isolates at a calculated optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.0005. Cultures were incubated at 30°C for 24 h, and then fungal growth was assessed by alamarBlue reduction. After screening by bioassay, microsomal metabolism was directly monitored by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), which confirmed an increased half-life of >30 min in rabbit microsomes for LCUT-8 (Table 2). For LC-MS, reaction aliquots were quenched 1:1 with ice-cold acetonitrile containing 0.5% formic acid. The deproteinized samples were analyzed by LC-MS using a Waters Xevo quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer, and peak areas were quantified using a 0.05 m/z window.

TABLE 2.

LCUT-8 is metabolized more slowly by rabbit liver microsomes

| Compound | Metabolism (mean ± SD) asa: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Half-life (min) | Intrinsic clearance (μl/min/mg) | |

| LCUT-2 | 4.3 ± 0.19 | 1,622 ± 73 |

| LCUT-3 | 2.6 ± 0.02 | 2,642 ± 15 |

| LCUT-5 | 2.7 ± 1.63 | 3,090 ± 1,849 |

| LCUT-6 | 1.5 ± 0.15 | 4,636 ± 453 |

| LCUT-8 | 34.8 ± 1.13 | 199 ± 6 |

| LCUT-10 | 3.3 ± 0.07 | 2,107 ± 44 |

| LCUT-12 | 2.1 ± 0.11 | 3,272 ± 174 |

| Verapamil (unstable control) | 22.6 ± 3.83 | 311 ± 53 |

| Antipyrine (stable control) | >30 | NA |

Reactions contained 1 μM compound, pooled female rabbit liver microsomes (0.1 mg/ml protein), and NADPH-regenerating system. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C on an orbital shaker at 175 rpm. At 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min, reaction aliquots were quenched, and soluble material was analyzed by LC-MS. Data are expressed as means of 2 independent experiments performed in technical duplicate. NA, not available.

Encouraged by the in vitro stability of LCUT-8, we performed a single-dose pharmacokinetic (PK) study in which four rabbits received 25 mg/kg LCUT-8 intravenously (i.v.), formulated in a Cremophor EL-based vehicle (7.5% Cremophor EL, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 87.5% PBS) (Fig. 2A). Based on a noncompartmental model over 24 h (R2 = 0.998), LCUT-8 achieved a near-maximum plasma concentration of 22.1 μg/ml (63 μM), with a calculated volume of distribution of 3.12 × 103 ml/kg and clearance rate of 1.48 × 103 ml/h/kg (Fig. 2A). However, the data demonstrate a probable two-compartment model with a first phase of redistribution from the central compartment followed by a prolonged half-life of 16 to 18 h from a large volume of distribution. Construction of a true compartmental model, however, would require repeated dosing to steady state.

FIG 2.

Pharmacokinetic and efficacy studies of LCUT-8 for treatment of disseminated candidiasis in a neutropenic rabbit model. (A) Single-dose PK study of LCUT-8. Four rabbits received LCUT-8 (25 mg/kg i.v.); serum concentration was quantified by LC-MS. Data are means ± SD for one experiment. ULOQ, upper limit of quantitation; LLOQ, lower limit of quantitation. (B) LCUT-8 did not alter tissue fungal burden. Rabbits (6/group) were treated with LCUT-8 (12.5 mg/kg i.v. twice daily) or DAMB (1 mg/kg i.v. once daily), and fungal burden in these groups were compared to that of an untreated control group. Data are expressed as mean fungal burden (CFU/g) ± SEM for liver, spleen, kidney, cerebrum, and lung. *, P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test. The lower limit of detection was 10 CFU/g. (C) LCUT-8 did not prolong survival. Results of Kaplan-Meier survival analysis are presented. *, P < 0.05, Mantel-Cox log-rank test.

With PK parameters suggesting the ability to achieve adequate systemic exposure, we pursued an efficacy study for LCUT-8 in a well-established model of subacute disseminated candidiasis in neutropenic rabbits (23–25). Healthy female New Zealand White rabbits (2.5 to 3.4 kg) were monitored according to National Research Council guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals, as approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rabbits were individually housed and given water and standard rabbit feed ad libitum. Atraumatic vascular access was established by surgical placement of a Silastic tunneled central venous catheter for fungal inoculation, compound administration, and serum sampling (26). Rabbits were euthanized at the end of the study or at prespecified humane endpoints using 65 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (Euthasol).

After pretreatment to establish a neutropenic state (26), rabbits were inoculated with 1 × 103 CFU C. albicans, then treated (6/group) with LCUT-8 (12.5 mg/kg twice daily) or deoxycholate amphotericin B (DAMB) (1 mg/kg once daily) i.v. for 10 days (Fig. 2B). As the primary study endpoint, quantitative C. albicans residual fungal burden was measured in the kidney, liver, spleen, cerebrum, and lung. For determination of fungal burden, representative sections of these tissues were homogenized for 30 s in 0.9% saline (Stomacher 80; Tekmar Corp.). CFUs were counted after specimens were serially diluted in 0.9% saline, plated on Sabouraud agar containing chloramphenicol, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Treatment with LCUT-8, at the maximal dose and schedule that could be tested given solubility constraints, resulted in no significant difference in fungal burden in liver, spleen, kidney, cerebrum, and lung compared with saline-treated controls (Fig. 2B). Cremophor EL vehicle alone did not alter fungal burden compared with saline-treated controls (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, treatment with DAMB significantly reduced fungal burden in all tissues analyzed (Fig. 2B).

In conclusion, we identified 13 structural analogs of gepinacin with broad-spectrum antifungal activity in vitro. The lead inhibitor, LCUT-8, was 4-fold more potent than gepinacin against C. albicans in vitro. Replacement of gepinacin’s isobutyl substituent with 2-pyridine and elimination of its metabolically labile methoxy substituent slowed microsomal metabolism in vitro. However, i.v. administration of LCUT-8 at the most intensive dose and schedule we were able to test due to solubility constraints did not alter fungal burden, suggesting inadequate systemic exposure. Despite this negative outcome, the valuable SAR insights gained in this study do enable further work to optimize pharmacokinetic properties of gepinacin-derived GPI inhibitors, especially exploration of prodrug strategies to improve aqueous solubility and deliver an effective second-in-class inhibitor of GPI anchor biosynthesis for the treatment of invasive fungal infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Mass spectrometry was performed by Taira Kiyota and Ahmed Aman at the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Toronto, Canada.

Funding for this work was provided by the Canadian Glycomics Network translational research grant AM-22.

S.D.L. was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council postdoctoral fellowship (516840-2018). T.J.W. was supported in part as a Scholar of the Henry Schueler Foundation and an Investigator of Emerging Infectious Diseases of the Save Our Sick Kids Foundation.

L.E.C. is a Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Microbial Genomics & Infectious Disease and codirector of the CIFAR Fungal Kingdom: Threats & Opportunities program. L.W. and L.E.C. are cofounders and shareholders in Bright Angel Therapeutics, a platform company for development of novel antifungal therapeutics. L.E.C. is a consultant for Boragen, a small-molecule development company focused on leveraging the unique chemical properties of boron chemistry for crop protection and animal health. T.J.W. has received grants for experimental and clinical antimicrobial pharmacology and therapeutics to his institution from Allergan, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Leadiant Biosciences, Medicines Company, Merck, Scynexis, Tetraphase, and Viosera Therapeutics and has served as consultant to Amplyx Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Allergan, ContraFect, Gilead, Leadiant Biosciences, Medicines Company, Merck, Methylgene, Pfizer, PurpleSun, and Scynexis.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson LS, Reyes CM, Stolpman M, Speckman J, Allen K, Beney J. 2002. The direct cost and incidence of systemic fungal infections. Value Health 5:26–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. 2012. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. 2017. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J Fungi (Basel) 3:57. doi: 10.3390/jof3040057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Low C-Y, Rotstein C. 2011. Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Med Rep 3:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. 2010. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol 36:1–53. doi: 10.3109/10408410903241444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enoch DA, Ludlam HA, Brown NM. 2006. Invasive fungal infections: a review of epidemiology and management options. J Med Microbiol 55:809–818. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues CF, Rodrigues ME, Henriques M. 2019. Candida sp. infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med 8:76. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy MW, Kontoyiannis DP, Cornely OA, Perfect J, Walsh TJ. 2017. Novel agents and drug targets to meet the challenges of resistant fungi. J Infect Dis 216(Suppl 3):S474–S483. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutz M, Roemer T. 2016. The GPI anchor pathway: a promising antifungal target? Future Med Chem 8:1387–1391. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2016-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yadav U, Khan MA. 2018. Targeting the GPI biosynthetic pathway. Pathog Glob Health 112:115–122. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2018.1442764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittet M, Conzelmann A. 2007. Biosynthesis and function of GPI proteins in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1771:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLellan CA, Whitesell L, King OD, Lancaster AK, Mazitschek R, Lindquist S. 2012. Inhibiting GPI anchor biosynthesis in fungi stresses the endoplasmic reticulum and enhances immunogenicity. ACS Chem Biol 7:1520–1528. doi: 10.1021/cb300235m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umemura M, Okamoto M, Nakayama K-I, Sagane K, Tsukahara K, Hata K, Jigami Y. 2003. GWT1 gene is required for inositol acylation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors in yeast. J Biol Chem 278:23639–23647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukahara K, Hata K, Nakamoto K, Sagane K, Watanabe N-A, Kuromitsu J, Kai J, Tsuchiya M, Ohba F, Jigami Y, Yoshimatsu K, Nagasu T. 2003. Medicinal genetics approach towards identifying the molecular target of a novel inhibitor of fungal cell wall assembly. Mol Microbiol 48:1029–1042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe N-A, Miyazaki M, Horii T, Sagane K, Tsukahara K, Hata K. 2012. E1210, a new broad-spectrum antifungal, suppresses Candida albicans hyphal growth through inhibition of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:960–971. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00731-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann PA, McLellan CA, Koseoglu S, Si Q, Kuzmin E, Flattery A, Harris G, Sher X, Murgolo N, Wang H, Devito K, de Pedro N, Genilloud O, Kahn JN, Jiang B, Costanzo M, Boone C, Garlisi CG, Lindquist S, Roemer T. 2015. Chemical genomics-based antifungal drug discovery: targeting glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) precursor biosynthesis. ACS Infect Dis 1:59–72. doi: 10.1021/id5000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman J, Muzzey D, Schwartz K, Weissman JS, Sherlock G. 2013. Assembly of a phased diploid Candida albicans genome facilitates allele-specific measurements and provides a simple model for repeat and indel structure. Genome Biol 14:R97. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-9-r97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard—3rd ed. CLSI document M27-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterjee S, Alampalli SV, Nageshan RK, Chettiar ST, Joshi S, Tatu US. 2015. Draft genome of a commonly misdiagnosed multidrug resistant pathogen Candida auris. BMC Genomics 16:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1863-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perfect JR, Lang SD, Durack DT. 1980. Chronic cryptococcal meningitis: a new experimental model in rabbits. Am J Pathol 101:177–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fidel PL, Cutright JL, Tait L, Sobel JD. 1996. A murine model of Candida glabrata vaginitis. J Infect Dis 173:425–431. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JB, Sirjusingh C, Parsons AB, Boone C, Wickens C, Cowen LE, Kohn LM. 2003. Mode of selection and experimental evolution of antifungal drug resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 163:1287–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh TJ, Aoki S, Mechinaud F, Bacher J, Lee J, Rubin M, Pizzo PA. 1990. Effects of preventive, early, and late antifungal chemotherapy with fluconazole in different granulocytopenic models of experimental disseminated candidiasis. J Infect Dis 161:755–760. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groll AH, Mickiene D, Petraitiene R, Petraitis V, Lyman CA, Bacher JS, Piscitelli SC, Walsh TJ. 2001. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of anidulafungin (LY303366): reappraisal of its efficacy in neutropenic animal models of opportunistic mycoses using optimal plasma sampling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2845–2855. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2845-2855.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petraitis V, Petraitiene R, Groll AH, Roussillon K, Hemmings M, Lyman CA, Sein T, Bacher J, Bekersky I, Walsh TJ. 2002. Comparative antifungal activities and plasma pharmacokinetics of micafungin (FK463) against disseminated candidiasis and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in persistently neutropenic rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1857–1869. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1857-1869.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh TJ, Bacher J, Pizzo PA. 1988. Chronic Silastic central venous catheterization for induction, maintenance and support of persistent granulocytopenia in rabbits. Lab Anim Sci 38:467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.