Doxycycline is regarded as an effective therapy for early syphilis, and there is increasing interest in using doxycycline for prophylaxis of this infection. However, the MIC of doxycycline for Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum has not been reported previously. In this study, an in vitro culture system was utilized to determine that the MIC of doxycycline is 0.06 to 0.10 μg/ml for four strains of T. pallidum subsp.

KEYWORDS: Treponema pallidum, antimicrobial susceptibility, doxycycline, spirochetal infections, syphilis

ABSTRACT

Doxycycline is regarded as an effective therapy for early syphilis, and there is increasing interest in using doxycycline for prophylaxis of this infection. However, the MIC of doxycycline for Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum has not been reported previously. In this study, an in vitro culture system was utilized to determine that the MIC of doxycycline is 0.06 to 0.10 μg/ml for four strains of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols, SS14, UW231B, and UW249B). The Nichols strain cultured in vitro with doxycycline was also tested for infectivity in rabbits, and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was found to be ≤0.1 μg/ml using this method. The low MIC and MBC values are consistent with the previously demonstrated clinical efficacy of doxycycline for the treatment of early syphilis. This study represents the first report of the in vitro susceptibility of T. pallidum to doxycycline, and the resulting information may be useful in the consideration of doxycycline for use in prevention of syphilis.

INTRODUCTION

Doxycycline is regarded as an effective treatment for early syphilis (1–10). There is increasing interest in using doxycycline for preexposure prophylaxis in individuals identified to be at risk for development of this infection, and the clinical efficacy of this approach is under active investigation (11–16). Doxycycline has also been used for postexposure prophylaxis. A recent clinical trial found that a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline administered within 72 h after a high-risk sexual exposure was 73% effective for prevention of syphilis (17, 18). Although a culture system to determine the activity of antibiotics against Treponema pallidum in vitro has been developed (19, 20), to date no study has evaluated the activity of doxycycline using this methodology. In this study, an in vitro culture system coupled with an experimental rabbit infection was used to provide the first evaluation of the minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentrations of doxycycline against T. pallidum subsp. pallidum.

RESULTS

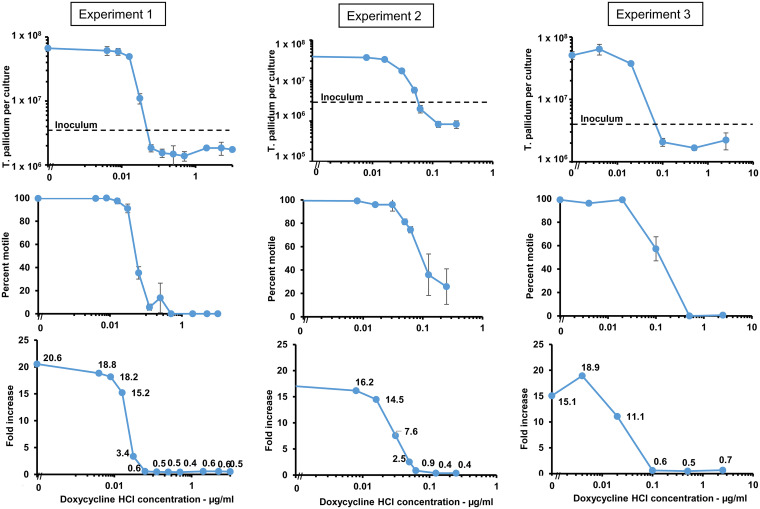

Susceptibility of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain) to doxycycline was tested using an in vitro cultivation system for T. pallidum (20). T. pallidum was cocultured with Sf1Ep cells in medium containing a range of concentrations of doxycycline HCl for 7 days; 5-fold and 2-fold dilutions of doxycycline were utilized in different experiments to provide broad and narrow resolution of inhibitory concentrations. Cultures were then examined for multiplication and motility (an indicator of treponemal viability). Three experiments were performed and yielded comparable results (Fig. 1; Table 1). In no antibiotic control cultures, T. pallidum multiplied 15- to 20-fold, with average generation times within the expected range of 32 to 43 h (mean, 36.7 ± 4.0 h) (Fig. 1). No increase in the number of T. pallidum organisms was obtained at any concentration of doxycycline of ≥0.0625 μg/ml. At doxycycline concentrations of 0.031 μg/ml to 0.05 μg/ml, we observed reduced growth of T. pallidum. Likewise, T. pallidum motility was high (96% to 100%) at doxycycline concentrations less than 0.031 μg/ml and in the control cultures but decreased at higher doxycycline concentrations. The MIC was estimated to be 0.06 μg/ml by interpolation of neighboring values (Fig. 1). The decrease in percent motile organisms closely paralleled the loss of multiplication, although a low (and highly variable) percentage of treponemes remained motile even at concentrations of doxycycline that resulted in complete loss of multiplication above the inoculum concentration.

FIG 1.

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum Nichols multiplication and viability is inhibited by concentrations of doxycycline greater than 0.06 μg/ml. Results of three independent experiments are shown. The top panels show the yield of T. pallidum per culture in the presence of various concentrations of doxycycline HCl for each of the three experiments; the inoculum is indicated by the dotted line. The middle panels portray the percent motility of T. pallidum in those cultures. The bottom panels indicate the fold increase at each concentration of doxycycline. T. pallidum per culture and percent motility values represent the means ± S.E. for three biologic replicates. The inoculum was 3.3 × 106 in experiment 1, 2.3 × 106 in experiment 2, and 3.4 × 106 in experiment 3.

TABLE 1.

Effects of in vitro exposure to doxycycline HCl on the multiplication and infectivity of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum Nicholsa

| Antibiotic concn (μg/ml) | Multiplication and motility |

Infectivityb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tp/culture (×106 ± SE) | Motility (% ± SE) | Fold increasec | T. pallidum dosage per sited | No. of lesions/no. of sites inoculated | Day of lesion development | Avg | |

| None | 50.9 ± 7.5 | 99 | 15.1 ± 2.2 | 1.9 × 106 | 4/4 | 4, 4, 4, 5 | 4.3 |

| 0.004 | 63.9 ± 12.6 | 96 | 18.9 ± 3.7 | 2.2 × 106 | 4/4 | 4, 4, 5, 5 | 4.5 |

| 0.02 | 37.4 ± 1.3 | 99 | 11.1 ± 0.4 | 1.4 × 106 | 4/4 | 4, 4, 5, 6 | 4.8 |

| 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 57 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 5.8 × 104 | 0/4 | ||

| 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 6.5 × 104 | 0/4 | ||

| 2.5 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 1 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 1.2 × 105 | 0/4 | ||

In vitro culture of T. pallidum in the presence of the concentrations of doxycycline shown was conducted as described in Materials and Methods and depicted in Fig. 1, experiment 3. The inoculum per culture in this study was 3.4 × 106 T. pallidum cells. After 7 days of culture, 0.1 ml of the pooled cultures from each antibiotic concentration were inoculated intradermally into the backs of two rabbits; 2 sites per rabbit, i.e., 4 sites in total for each antibiotic concentration tested. Inoculation sites were checked daily for lesion development.

Lesion development is defined as the occurrence of both erythema and induration at the site of infection.

Fold increase in T. pallidum harvested per culture/inoculum.

Total number of T. pallidum organisms (both motile and nonmotile).

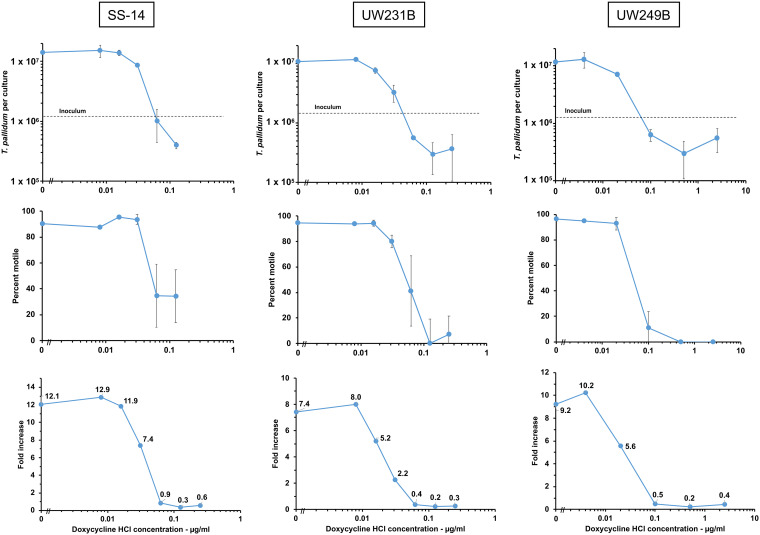

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum isolates can be subdivided into two highly related (but genetically distinct) clusters, which are generally described as being related to either the Nichols strain or the SS14 strain (21, 22). The SS14-related cluster is currently predominant in most areas of the world. Therefore, it was important to also examine the susceptibility of strains of the SS14 cluster to doxycycline. The results obtained with strains SS14, UW231B, and UW249B were very similar to those of the Nichols strain (Fig. 2). Multiplication of these strains was completely inhibited (as defined by a fold increase value of ≤1) by doxycycline concentrations in the range of 0.0625 μg/ml to 0.1 μg/ml (see Table 2). Interpolation of doxycycline concentration values to determine the concentration at which the fold increase value equaled one resulted in calculated MIC values of 0.045 μg/ml to 0.086 μg/ml (see Table 2). Based on these results, it is reasonable to consider the MIC for doxycycline to be ≤0.1 μg/ml for the four strains examined.

FIG 2.

Effect of doxycycline concentration on the multiplication, motility, and fold increase of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum strains SS14, UW231B, and UW249B. Results presented are from one of two experiments performed for each strain; highly similar results were obtained in the second experiment in each case.

TABLE 2.

MICs of doxycycline obtained against T. pallidum subsp. pallidum strainsa

| Strain | Minimum effective concn tested (μg/ml) | Interpolated MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Nichols | 0.0625 | 0.052 |

| Nichols | 0.0625 | 0.061 |

| Nichols | 0.100 | 0.086 |

| SS14 | 0.100 | 0.079 |

| SS14 | 0.0625 | 0.060 |

| UW231B | 0.100 | 0.066 |

| UW231B | 0.0625 | 0.045 |

| UW249B | 0.100 | 0.077 |

| UW249B | 0.100 | 0.053 |

Data are derived from three independent experiments for the Nichols strain and two independent experiments for each of the other three strains.

Examination of the infectivity of T. pallidum in rabbits following treatment of in vitro cultures with dilutions of antimicrobial agents provides a measure of their minimum bactericidal concentrations (19, 23). Therefore, we tested the ability of T. pallidum cultured in vitro with doxycycline to cause infection in rabbits. Infectivity of T. pallidum was assessed by injection into the shaved backs of rabbits. Lesions arise reproducibly from as few as 10 organisms, with the time of lesion development correlated with the number of infectious organisms injected at each site (19, 20, 24–26).

To assess the effects of doxycycline on the infectivity of T. pallidum Nichols, an experiment was performed using a wider range of doxycycline concentrations (0.004 μg/ml, 0.02 μg/ml, 0.1 μg/ml, 0.5 μg/ml, and 2.5 μg/ml) along with a no antibiotic control. After 1 week of incubation, the cultured spirochetes were assessed microscopically for multiplication and motility (Fig. 1, experiment 3) and injected intradermally into the shaved backs of rabbits to assess their virulence. As expected, no growth of T. pallidum occurred at concentrations of doxycycline equal to or greater than 0.1 μg/ml (Table 1). However, significant motility (57%) was retained in vitro at 0.1 μg/ml doxycycline, and occasional motile organisms could be detected at higher concentrations. However, no lesions developed from any in vitro culture with a concentration of doxycycline that inhibited T. pallidum multiplication. The results demonstrate that the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of T. pallidum cultured in vitro with doxycycline is ≤0.1 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

Based on in vitro culture of four strains of T. pallidum subsp. pallidum, a MIC value of ≤0.1 μg/ml doxycycline was demonstrated, implying that this antibiotic should be highly effective for both treatment and prevention of syphilis. Indeed, all experiments that included 0.0625 μg/ml doxycycline showed complete inhibition of growth at that concentration, indicating that the MIC actually is at, or below, that level (Table 2). Given the high degree of genome sequence identity among T. pallidum subspecies and strains, it is likely that all T. pallidum strains will have similar susceptibilities to doxycycline. In recent genetic studies, none of the T. pallidum-positive specimens from 108 syphilis patients in Spain (27) or 53 syphilis patients in Italy (28) exhibited the mutations in 16S rRNA genes (A965T and G1058A) that confer resistance to tetracyclines in other bacteria. In contrast, ∼94% of the specimens from both of these study populations had 23S rRNA gene mutations (A2058G or A2059G) associated with macrolide resistance. In addition, the doxycycline MIC was similar to the MIC of 0.2 μg/ml previously determined for tetracycline (19).

The in vitro culture method of T. pallidum antimicrobial susceptibility determination is similar to the broth dilution procedure commonly used with other bacteria (29–31). There are, however, some important differences. First, the presence of Sf1Ep cells is necessary to promote long-term survival and multiplication of T. pallidum. The spirochete multiplies extracellularly; thus, the inclusion of mammalian cells does not introduce a potential permeability barrier, as is the case for intracellular bacteria such as Chlamydia (32). Second, incubation for 7 days was used in the T. pallidum assay instead of the 16 to 20 h typically used in broth dilution testing for most bacteria. This extended incubation period was utilized to permit substantial multiplication of T. pallidum, which has a doubling time of approximately 40 to 60 h (compared to 20 to 30 min for Escherichia coli). Third, microscopic bacterial quantitation was utilized instead of visual inspection for turbidity or pellet formation, because T. pallidum must be at high concentrations (>109 per ml) to produce turbidity and does not achieve these levels during in vitro culture. Quantitation by microscopy is time-consuming but likely provides more accurate results than assessment of turbidity; future studies could use other quantitation procedures, such as quantitative PCR (32).

Prolonged incubation for antimicrobial susceptibility assessment is also needed for other slow-growing bacteria, most notably Mycobacterium tuberculosis (33). The long incubation period, as well as the presence of mammalian cells, may result in higher MIC and MBC values for an antimicrobial agent than the actual value due to degradation of the drug occurring over time. Doxycycline, however, is a highly stable compound in patients, with no significant metabolism, and is excreted intact (34, 35). Therefore, it is likely (although not explicitly proven) that the doxycycline concentrations were maintained at relatively constant levels during the 7-day incubation period in our experiments. For less stable antibiotics, drug levels should be assessed at the end of the incubation period by bioassay, mass spectroscopy, or another means.

As shown in this and in prior studies (19, 23), the in vitro culture method of T. pallidum yields highly reproducible results. We believe that this assay provides a much more accurate assessment of MIC and MBC values than prior methods, which included examining T. pallidum motility following overnight incubation in the presence of different antibiotic concentrations (reviewed in reference 23). Motility only requires preservation of membrane integrity, metabolic activity, and flagellar function; as such, it does not necessarily reflect the ability of the organism to multiply, which is required to cause infection. As shown in our studies, some of the spirochetes remained motile at concentrations of doxycycline that completely inhibited multiplication of T. pallidum (Table 1). However, these same cultures were noninfectious when inoculated into rabbits; this procedure is an extremely sensitive means of assessing the ability of T. pallidum to multiply, in that as few as 10 T. pallidum cells can consistently cause infection in the rabbit model (19, 20, 25, 26). Thus, the loss of infectivity is a better indication of the multiplication potential of the organism than is motility, and in our opinion it provides a valid measure of the MBC for antimicrobial agents against T. pallidum.

MBC is usually defined as the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that kills ≥99.9% of the test inoculum (30). In the infectivity experiment, the inoculum incubated with 0.1 μg/ml doxycycline contained 3.3 × 104 motile treponemes. Thus, a greater than 3-log decrease in viability of the inoculum was observed. Although doxycycline is usually considered bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal, our studies indicate that doxycycline deals a fatal blow to T. pallidum, and, thus, is bactericidal under the conditions used (Table 1).

In vitro susceptibility testing of other spirochetes to doxycycline, such as Borreliella (Lyme disease-related) and Leptospira species, has also been performed, albeit using different test conditions. In one study of 30 isolates of Borreliella species, the MIC values varied from 0.10 μg/ml to 0.80 μg/ml (36), with other studies finding MIC values as low as 0.03 μg/ml and as high as 4.0 μg/ml (37–41). Although failure of Lyme borreliosis treatment with doxycycline has been reported anecdotally (41), the finding that all strains tested have doxycycline MICs of ≤4 μg/ml indicates that high-level resistance against this agent has not developed in the Borreliella isolates tested. In addition, in a study of 13 human isolates of Leptospira species, the MICs of doxycycline varied from ≤0.016 μg/ml to 2.0 μg/ml (42). Thus, the spirochetes pathogenic for humans generally appear to be susceptible to doxycycline.

In the current study, doxycycline was found to be highly active in vitro against T. pallidum, an observation consistent with the previously demonstrated efficacy of doxycycline in humans both for the treatment of early syphilis using a 14-day course of treatment (1–4, 7–9) and for the prevention of syphilis when administered after a high-risk sexual exposure, using just a single 200-mg dose of the drug (17). Based on at least 6 studies in humans, the peak doxycycline blood level after a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline given orally is reached within 2 to 3 h and equals or exceeds 2.6 μg/ml, with a relatively long elimination half-life of 12 to 25 h (35). Therefore, after a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline taken orally, the blood level of doxycycline would be expected to exceed 0.1 μg/ml on the day of administration and remain above 0.1 μg/ml for at least 48 h following the time point when the peak blood level occurred (35).

In addition, in a bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) prophylaxis clinical trial using daily oral doxycycline hyclate doses of 100 mg, doxycycline plasma concentrations were determined at three office visits; those subjects adherent with self-administration of doxycycline on the day of the examination had doxycycline levels in excess of 1 μg/ml (12). Thus, plasma levels in human subjects after oral administration of doxycycline are far in excess of the MIC of ≤0.1 μg/ml determined in the present study.

Although penicillin continues to be an effective treatment for syphilis (8), most considerations of preexposure or postexposure treatments for prevention of bacterial STIs have favored the use of orally administered antimicrobial agents that have broad-spectrum activity against many STIs, potentially including gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and chancroid (12, 14, 15, 17, 18). The results of our analysis may be useful in a multifactorial assessment of prophylaxis with doxycycline for prevention of syphilis and other bacterial STIs (12–18, 43, 44).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum Nichols, initially isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of a neurosyphilis patient in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1912 (45), was provided by J. N. Miller at the UCLA Geffen School of Medicine. The SS14 strain, isolated from a patient with secondary syphilis in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1977 (46), was obtained from D. L. Cox at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strains UW231B and UW249B were isolated by inoculation of rabbits with blood from patients in the Seattle, Washington, region (47); these strains were kindly provided by L. C. Tantalo, S. K. Sahi, and C. M. Marra at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Animals.

Male New Zealand White rabbits (3 to 4 kg) were obtained from Charles River (www.criver.com). Rabbits were provided antibiotic-free food and water and housed at 17 to 19°C. T. pallidum strains were propagated in rabbits and stored at –80°C as described previously. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

In vitro cultivation of T. pallidum.

Procedures for the in vitro cultivation of T. pallidum were conducted as described previously (20). Briefly, T. pallidum cells were grown in coculture with Sf1Ep cottontail rabbit epithelial (NBL-11) cells (ATCC CCL-68). Stocks of Sf1Ep cells were maintained in Sf1Ep medium consisting of Eagle’s MEM with nonessential amino acids, l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C in air with 5% CO2. Sf1Ep cells were used between passage 41 and 58. One day prior to initiation of antibiotic testing, Sf1Ep cells were seeded into tissue culture-treated 12-well cluster plates at 4 × 104 cells per well.

T. pallidum cultivation medium (TpCM-2) was prepared as previously reported (20). The medium was prepared the day before experiment initiation and preequilibrated in a BBL GasPak jar in which a vacuum was drawn five times (house vacuum, ∼12 to 18 μm Hg). The jar was refilled with 5% CO2:95% N2 four times and a fifth and final time with 1.5% O2:5% CO2:93.5% N2. The medium was then incubated overnight in a trigas incubator (Forma model 3130; ThermoFisher) maintained at 34°C and 1.5% O2:5% CO2:93.5% N2 (here referred to as the low-oxygen incubator). All subsequent steps in the incubation of T. pallidum cultures were carried out under these conditions.

Three hours prior to the start of an experiment, the medium in the 12-well plates containing Sf1EP cells was removed, the plates were rinsed with 0.5 ml preequilibrated TpCM-2 to remove traces of Sf1Ep medium, and the medium was replaced with 2 ml of TpCM-2. Doxycycline HCl (D3447; Sigma) was dissolved in sterile distilled water at 10 mg/ml. Appropriate dilutions were made in water and added to each well to obtain the indicated antibiotic concentrations (ranging from 0.004 μg/ml to 10 μg/ml). A positive control with no antibiotic was also initiated. Triplicate wells were used for each condition. Plates were then preequilibrated in the GasPak jar as described above and transferred to the low-oxygen incubator.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was initiated by inoculation of cultures with T. pallidum strains freshly harvested from in vitro cultures. Sf1Ep cultures containing doxycycline were briefly removed from the incubator, inoculated with T. pallidum, reequilibrated, and then returned to the low-oxygen incubator. Following 7 days of incubation, the cultures were rinsed with 0.2 ml trypsin-EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and then treated for 5 min at 37°C with an additional 0.2 ml to dissociate the T. pallidum from the Sf1Ep cells (20). The medium, rinse, and trypsinized culture were combined, and the concentration of T. pallidum was quantitated by dark-field microscopy using Helber counting chambers with Thoma rulings (Hawksley, Lancing, Sussex, UK). Using this method, the bacterial counts for each culture were determined at least twice and the values averaged; the data shown represent the means ± standard errors (S.E.) obtained for three biologic replicates for each condition. The percentage ± S.E. of motile organisms was also determined for each culture. The MIC for each experiment was considered to be the lowest dilution at which the average number of T. pallidum per culture was less than or equal to the inoculum. Some experiments used 5-fold doxycycline concentration differences to generate the curve, whereas others had 2-fold differences. More precise MIC values were determined by interpolation of neighboring data points where the log2 fold increase values were >0 on one side and <0 on the other. The doxycycline concentration at the intercept between the points where log2 fold increase was 0 was considered the interpolated MIC value for that experiment.

Infectivity studies.

To assess the virulence of T. pallidum cultured in the presence of doxycycline, samples of 7-day cultures were used to infect New Zealand White rabbits as described previously (19, 24, 26). Aliquots of three biological replicates from each antibiotic concentration were prepared as described above, pooled, and injected intradermally into the shaved backs of rabbits (0.1 ml per site). Two rabbits were inoculated at duplicate sites with each sample, for a total of 4 sites per antibiotic concentration and 12 sites per animal; the 12 sites were based on the 6 different antibiotic concentrations shown in Table 1. The inoculum was quantitated by dark-field microscopy as described above and the motility of the spirochetes assessed. The backs of the rabbits were shaved as needed to fully expose the inoculation sites throughout the 45-day course of the experiment. The inoculation sites were examined daily for the development of erythema and induration, which together constitute lesion development. Needle aspirates of representative lesions were examined by dark-field microscopy for the presence of motile treponemes, indicating active treponemal infection. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration at which lesions did not develop.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bridget DeLay, Lindsay Kowis, Julia Singer, Elizabeth Flatley, and Lisa Giarratano for their assistance.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AI141958. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

G.P.W. reports receiving research grants from Immunetics, Inc., Institute for Systems Biology, Rarecyte, Inc., and Quidel Corporation. He owns equity in Abbott/AbbVie; has been an expert witness in malpractice cases involving Lyme disease; and is an unpaid board member of the American Lyme Disease Foundation. D.G.E. and S.J.N. report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harshan V, Jayakumar W. 1982. Doxycycline in early syphilis: a long term follow up. Indian J Dermatol 27:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ, Cheng WW, Rompalo AM. 2006. Doxycycline compared with benzathine penicillin for the treatment of early syphilis. Clin Infect Dis 42:e45. doi: 10.1086/500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong T, Singh AE, De P. 2008. Primary syphilis: serological treatment response to doxycycline/tetracycline versus benzathine penicillin. Am J Med 121:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psomas KC, Brun M, Causse A, Atoui N, Reynes J, Le Moing V. 2012. Efficacy of ceftriaxone and doxycycline in the treatment of early syphilis. Med Mal Infect 42:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Zheng HY. 2014. Early syphilis: serological treatment response to doxycycline/tetracycline versus benzathine penicillin. J Infect Dev Ctries 8:228–232. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai JC, Lin YH, Lu PL, Shen NJ, Yang CJ, Lee NY, Tang HJ, Liu YM, Huang WC, Lee CH, Ko WC, Chen YH, Lin HH, Chen TC, Hung CC. 2014. Comparison of serological response to doxycycline versus benzathine penicillin G in the treatment of early syphilis in HIV-infected patients: a multi-center observational study. PLoS One 9:e109813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanem KG. 2015. Management of adult syphilis: key questions to inform the 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 61(Suppl 8):S818–S836. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Workowski K, Bolan G. 2015. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64:1–137.25590678 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai T, Qu R, Liu J, Zhou P, Wang Q. 2017. Efficacy of doxycycline in the treatment of syphilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01092-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01092-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonio MB, Cuba GT, Vasconcelos RP, Alves A, da Silva BO, Avelino-Silva VI. 2019. Natural experiment of syphilis treatment with doxycycline or benzathine penicillin in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 33:77–81. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson DP, Prestage GP, Gray RT, Hoare A, McCann P, Down I, Guy RJ, Drummond F, Klausner JD, Donovan B, Kaldor JM. 2011. Chemoprophylaxis is likely to be acceptable and could mitigate syphilis epidemics among populations of gay men. Sex Transm Dis 38:573–579. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820e64fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolan RK, Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Flynn RP, Leibowitz AA, Klausner JD. 2015. Doxycycline prophylaxis to reduce incident syphilis among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who continue to engage in high-risk sex: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Sex Transm Dis 42:98–103. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fusca L, Hull M, Ross P, Grennan T, Burchell AN, Bayoumi AM, Tan DHS. 2020. High interest in syphilis pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Vancouver and Toronto. Sex Transm Dis 47:224–231. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant JS, Stafylis C, Celum C, Grennan T, Haire B, Kaldor J, Luetkemeyer AF, Saunders JM, Molina JM, Klausner JD. 2020. Doxycycline prophylaxis for bacterial sexually transmitted infections. Clin Infect Dis 70:1247–1253. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peyriere H, Makinson A, Marchandin H, Reynes J. 2018. Doxycycline in the management of sexually transmitted infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:553–563. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wormser GP. 2020. Doxycycline for prevention of spirochetal infections–status report. Clin Infect Dis 2020:ciaa240. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina JM, Charreau I, Chidiac C, Pialoux G, Cua E, Delaugerre C, Capitant C, Rojas-Castro D, Fonsart J, Bercot B, Bebear C, Cotte L, Robineau O, Raffi F, Charbonneau P, Aslan A, Chas J, Niedbalski L, Spire B, Sagaon-Teyssier L, Carette D, Mestre SL, Dore V, Meyer L, Group AIS, ANRS IPERGAY Study Group. 2018. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect Dis 18:308–317. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30725-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairley CK, Chow EPF. 2018. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis: let the debate begin. Lancet Infect Dis 18:233–234. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norris SJ, Edmondson DG. 1988. In vitro culture system to determine MICs and MBCs of antimicrobial agents against Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 32:68–74. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edmondson DG, Hu B, Norris SJ. 2018. Long-term in vitro culture of the syphilis spirochete Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum. mBio 9:e01153-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01153-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nechvátal L, Pětrošová H, Grillová L, Pospíšilová P, Mikalová L, Strnadel R, Kuklová I, Kojanová M, Kreidlová M, Vaňousová D, Procházka P, Zákoucká H, Krchňáková A, Smajs D. 2014. Syphilis-causing strains belong to separate SS14-like or Nichols-like groups as defined by multilocus analysis of 19 Treponema pallidum strains. Int J Med Microbiol 304:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora N, Schuenemann VJ, Jager G, Peltzer A, Seitz A, Herbig A, Strouhal M, Grillova L, Sanchez-Buso L, Kuhnert D, Bos KI, Davis LR, Mikalova L, Bruisten S, Komericki P, French P, Grant PR, Pando MA, Vaulet LG, Fermepin MR, Martinez A, Centurion Lara A, Giacani L, Norris SJ, Smajs D, Bosshard PP, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Nieselt K, Krause J, Bagheri HC. 2016. Origin of modern syphilis and emergence of a pandemic Treponema pallidum cluster. Nat Microbiol 2:16245. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norris SJ, Cox DL, Weinstock GM. 2001. Biology of Treponema pallidum: correlation of functional activities with genome sequence data. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 3:37–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris SJ, Miller JN, Sykes JA, Fitzgerald TJ. 1978. Influence of oxygen tension, sulfhydryl compounds, and serum on the motility and virulence of Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) in a cell- free system. Infect Immun 22:689–697. doi: 10.1128/IAI.22.3.689-697.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnuson HJ, Eagle H. 1948. The minimal infectious inoculum of Spirochaeta pallida (Nichols strain), and a consideration of its rate of multiplication in vivo. Am J Syph 32:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner TB, Hollander DH. 1957. Biology of the treponematoses. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernández-Naval C, Arando M, Espasa M, Antón A, Fernández-Huerta M, Silgado A, Jimenez I, Villatoro AM, González-López JJ, Serra-Pladevall J, Sulleiro E, Pumarola T, Vall-Mayans M, Esperalba J. 2019. Enhanced molecular typing and macrolide and tetracycline resistance mutations of Treponema pallidum in Barcelona. Future Microbiol 14:1099–1108. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2019-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giacani L, Ciccarese G, Puga-Salazar C, Dal Conte I, Colli L, Cusini M, Ramoni S, Delmonte S, D’antuono A, Gaspari V, Drago F. 2018. Enhanced molecular typing of Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum strains from 4 Italian hospitals shows geographical differences in strain type heterogeneity, widespread resistance to macrolides, and lack of mutations associated with doxycycline resistance. Sex Transm Dis 45:237–242. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorgensen JH, Turnidge JD. 2015. Susceptibility test methods: dilution and disk diffusion methods, p 1253–1273. Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia LS. 2010. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, 3rd ed, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 31.CLSI. 2018. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 11th ed Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meštrović T, Virok DP, Ljubin-Sternak S, Raffai T, Burián K, Vraneš J. 2019. Antimicrobial resistance screening in Chlamydia trachomatis by optimized McCoy cell culture system and direct qPCR-based monitoring of chlamydial growth, p 33–44. In Brown AC. (ed), Chlamydia trachomatis: methods and protocols. Humana Press, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simner PJ, Stenger S, Richter E, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJJ, Wengenack NL. 2015. Mycobacterium: laboratory characteristics of slowly growing mycobacteria, p 570–594. In Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saivin S, Houin G. 1988. Clinical pharmacokinetics of doxycycline and minocycline. Clin Pharmacokinet 15:355–366. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198815060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agwuh KN, MacGowan A. 2006. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the tetracyclines including glycylcyclines. J Antimicrob Chemother 58:256–265. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baradaran-Dilmaghani R, Stanek G. 1996. In vitro susceptibility of thirty Borrelia strains from various sources against eight antimicrobial chemotherapeutics. Infection 24:60–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01780660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bontemps-Gallo S, Lawrence KA, Richards CL, Gherardini FC. 2018. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of Borrelia afzelii BO23 and Borrelia garinii CIP 103362. PLoS One 13:e0199641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruzic-Sabljic E, Podreka T, Maraspin V, Strle F. 2005. Susceptibility of Borrelia afzelii strains to antimicrobial agents. Int J Antimicrob Agents 25:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sicklinger M, Wienecke R, Neubert U. 2003. In vitro susceptibility testing of four antibiotics against Borrelia burgdorferi: a comparison of results for the three genospecies Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. J Clin Microbiol 41:1791–1793. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1791-1793.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunfeld KP, Kraiczy P, Kekoukh E, Schafer V, Brade V. 2002. Standardised in vitro susceptibility testing of Borrelia burgdorferi against well-known and newly developed antimicrobial agents–possible implications for new therapeutic approaches to Lyme disease. Int J Med Microbiol 291(Suppl 33):125–137. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(02)80024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunfeld KP, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Norris DE, Kraiczy P, Strle F. 2005. In vitro susceptibility testing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates cultured from patients with erythema migrans before and after antimicrobial chemotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:1294–1301. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1294-1301.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ressner RA, Griffith ME, Beckius ML, Pimentel G, Miller RS, Mende K, Fraser SL, Galloway RL, Hospenthal DR, Murray CK. 2008. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of geographically diverse clinical human isolates of Leptospira. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2750–2754. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00044-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenyon C, Van Dijck C, Florence E. 2020. Facing increased sexually transmitted infection incidence in HIV preexposure prophylaxis cohorts: what are the underlying determinants and what can be done? Curr Opin Infect Dis 33:51–58. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunn RA, Klausner JD. 2019. Enhancing the control of syphilis among men who have sex with men by focusing on acute infectious primary syphilis and core transmission groups. Sex Transm Dis 46:629–636. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nichols HJ, Hough WH. 1913. Demonstration of Spirochaeta pallida in the cerebrospinal fluid from a patient with nervous relapse following the use of salvarsan. JAMA 60:108–110. doi: 10.1001/jama.1913.04340020016005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stamm LV, Kerner TC, Bankaitis VA, Bassford PJ. 1983. Identification and preliminary characterization of Treponema pallidum protein antigens expressed in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 41:709–721. doi: 10.1128/IAI.41.2.709-721.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giacani L, Chattopadhyay S, Centurion-Lara A, Jeffrey BM, Le HT, Molini BJ, Lukehart SA, Sokurenko EV, Rockey DD. 2012. Footprint of positive selection in Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum genome sequences suggests adaptive microevolution of the syphilis pathogen. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]