Abstract

Atherosclerosis is initiated by functional changes in the endothelium accompanied by accumulation, oxidation, and glycation of LDL-cholesterol in the inner layer of the arterial wall and continues with the expression of adhesion molecules and release of chemoattractants. PCSK9 is a proprotein convertase that increases circulating LDL levels by directing hepatic LDL receptors into lysosomes for degradation. The effects of PCSK9 on hepatic LDL receptors and contribution to atherosclerosis via the induction of hyperlipidemia are well defined. Monoclonal PCSK9 antibodies that block the effects of PCSK9 on LDL receptors demonstrated beneficial results in cardiovascular outcome trials. In recent years, extrahepatic functions of PCSK9, particularly its direct effects on atherosclerotic plaques have received increasing attention. Experimental trials have revealed that PCSK9 plays a significant role in every step of atherosclerotic plaque formation. It contributes to foam cell formation by increasing the uptake of LDL by macrophages via scavenger receptors and inhibiting cholesterol efflux from macrophages. It induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and chemoattractants, thereby increasing monocyte recruitment, inflammatory cell adhesion, and inflammation at the atherosclerotic vascular wall. Moreover, low shear stress is associated with increased PCSK9 expression. PCSK9 may induce endothelial cell apoptosis and autophagy and stimulate the differentiation of smooth muscle cells from the contractile phenotype to synthetic phenotype. Increasing evidence indicates that PCSK9 is a molecular target in the development of novel approaches toward the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis. This review focuses on the molecular roles of PCSK9 in atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Keywords: PCSK9, Atherosclerosis, Form cell, Inflammation, Vascular wall

Atherosclerosis is a chronic condition that starts early in life and then continues lifelong. Atherosclerotic process begins with functional changes in the endothelium accompanied by accumulation, oxidation, and glycation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in the inner layer of the arterial wall and continues with the expression of adhesion molecules and the release of chemoattractants1). Monocytes and T cells are recruited in the intimal space, where monocytes engulf the oxidized LDL and become foam cells2). Fatty streaks, the earliest lesions of atherosclerosis, can be visualized in the aorta from the first decade of life. They appear in the coronary arteries in the second decade and in the cerebral arteries from the third or fourth decades3). Fatty streaks develop into atherosclerotic plaques, which can lead to luminal narrowing of the arteries causing ischemic complaints or plaque may become unstable, leading to acute atherothrombotic events.

Among the various risk factors of atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia—particularly LDL cholesterol—plays the main role in the initiation and progression of the atherosclerotic process4). As confirmed by several experimental and clinical studies, there is a clear, log–linear relationship between the LDL cholesterol level and atherosclerosis5, 6) Circulating LDL cholesterol level is mainly determined by the number of hepatic LDL cholesterol receptors (LDLR) and the expression or the activity of proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) enzyme7).

Proprotein convertases are a family of proteins that are responsible for post-translational modifications of many functional proteins, including proteolytic cleavage, and activation of most polypeptide hormones such as proinsulin8). Hepatic PCSK9 is the circulating protein that regulates the half-life of LDLR in the liver. In the absence of PCSK9, LDLR binds to LDL on the hepatocyte surface, transfers it into endosomes inside the hepatocyte, and recycles back to the cell surface to bind and internalize new LDL particles. Binding with PCSK9 routes the LDLR to lysosomal degradation, and the recycling of the LDLR is blocked9). Endocytosis of PCSK9-mediated LDLRs occurs both via clathrin- and caveolae-dependent pathways, whereas recycling of LDLR and PCSK9 complex occurs in clathrin-dependent pathway and degradation occurs in caveolae-dependent pathway. LDLR and PCSK9 complex interaction with adenyl cyclase associated protein-1 (CAP1) leads to caveolaedependent endocytosis10).

PCSK9, synthesized as a 74 kDa zymogen with 692 amino acids, comprises four domains, namely, the N-terminal pro-domain, signal peptide, the catalytic domain, and a C-terminal domain. Autocatalysis occurs between its pro-domain and catalytic domain in endoplasmic reticulum11). After autocatalysis, the pro-domain remains non-covalently attached to its catalytic pocket, which is unique to this enzyme12). N-terminal of pro-domain inhibits convertase activity of PCSK9, preventing it from interacting with surrounding substrates. Therefore, the pro-domain acts to modulate the effect of PCSK9 by releasing the catalytic domain. A short segment of amino acids in the catalytic domain of PCSK9 (amino acids 367 to 380) interacts with the epidermal growth factor-like A domain of LDLR to divert it to endosomes and lysosomes for degradation13, 14). The catalytic domain activity of PCSK9 is not required for its effect on LDLR. PCSK9 also escorts very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR), apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2), and LDLR-related protein-1 (LRP1) to lysosomal degradation15, 16).

PCSK9's Role in Atherosclerotic Process

The atherogenic effects of PCSK9 were initially explained through its role in lipid metabolism; however, plasma PCSK9 level is only modestly correlated with the plasma lipid levels17). In recent years, it has been recognized that beyond its effects on lipid metabolism, PCSK9 also has direct atherosclerotic effects on the vascular wall. Several preclinical and clinical studies showed that the relation of PCSK9 with atherosclerosis can be partly independent of its hyperlipidemic effects. In Apo E knock-out mice, PCSK9 accelerated atherosclerosis without affecting plasma lipid levels, whereas PCSK9 overexpression did not cause an increase in plasma lipids but in atherosclerotic lesion size18, 19). The Atheroma IVUS study revealed that the necrotic core volume of the atherosclerotic plaque increases proportionately to serum PCSK9 level independent of LDL cholesterol20). A 10 year follow-up study showed that the carotid plaque area and the formation of new carotid plaques are related to LDL levels and also independent to increased PCSK9 levels17). Moreover, STAINLAS study cohort revealed that increased PCSK9 level is found to be related to carotid plaque formation21). These trials, showing the relation of PCSK9 with atherosclerosis, have drawn attention to direct effects of PCSK9 on atherosclerotic plaques.

Vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are the main PCSK9 secreting cells in the vascular wall. Despite conflicting reports, many studies have shown that endothelial cells also express PCSK9, albeit less than SMC22, 23). Macrophages and human atherosclerotic plaques are other sources of PCSK9 expression. The expression of PCSK9 in various components of the arterial wall contributes to its direct effects in the initiation and progression of the atherosclerotic process. This review summarizes current data on the role of PCSK9 in atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Effects of PCSK9 in Oxidized LDL Uptake and Cholesterol Efflux

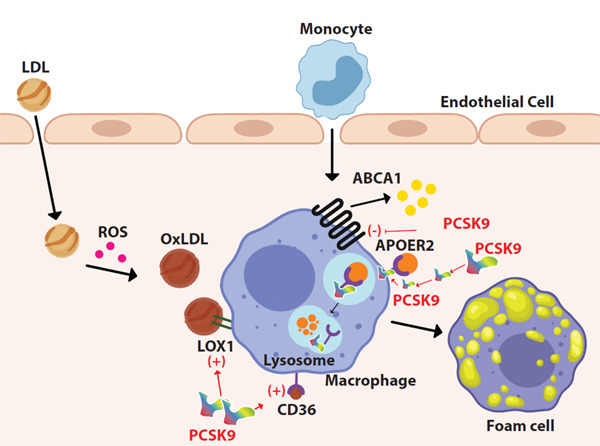

Atherosclerosis begins with the formation of foam cells, which are macrophages that engulf oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) (Fig. 1). Ox-LDL enters into the monocytes/macrophages and also SMCs and fibroblasts by scavenger receptors (SRs), including class A SR, class B SR type I, CD36, macrosialin (CD68), and lectin-like ox-LDL (LOX-1)24, 25). LOX-1 is the major receptor in the engulfment of ox-LDL by macrophages and also increases the production of cell surface adhesion molecules and is involved in the process of oxidative stress26–28). PCSK9 induces expression of all SRs, but mostly, LOX-1 on monocytes and SMCs24). In inflammatory milieu, PCSK9 and LOX1 induce each other, leading to an increased ox-LDL uptake29).

Fig. 1.

Foam cell formation. LDL enters into the intimal layer of the artery and oxidized by reactive oxygen species. Macrophages engulf oxidized LDL by scavenger receptors such as CD36 and LOX-1

ABCA1 receptor maintains cholesterol efflux from macrophage. PCSK9 contributes to the formation of foam cells by inducing scavenger receptors, inhibiting the ABCA1 receptor, and directing ApoEr2 to the lysosomes for degradation.

Excess intracellular free cholesterol is toxic for macrophages from which they protect themselves by cholesterol efflux to extracellular acceptors30). Inhibiting cholesterol efflux in macrophages causes an increase in foam cell formation. ATP Binding Cassette A1 (ABCA1), ATP Binding Cassette G1 (ABCG1), and Scavenger Receptor Class B Type I (SR-BI) are membrane transporters that provide most cholesterol efflux in macrophages. PCSK9 inhibits ABCA-1-dependent cholesterol efflux by downregulating the ABCA-1 gene and ABCA-1 protein expression; however, it does not inhibit ABCG1 expression and only slightly inhibits SIR-BI expression31).

Apolipoprotein (Apo E) is a lipid transport protein and major ligand for LDLR32). Parenchymal cells, differentiated macrophages, astrocytic glial cells, and SMCs synthesize and secrete Apo E, which take a role in the transport of cholesterol and other lipids between peripheral tissue and liver, mediating the clearance of chylomicrons and LDL in the liver. Apo E can reduce lipid accumulation in macrophages and inhibit foam cell formation and switching of macrophages from proinflammatory M1 phenotype to antiinflammatory M2 phenotype33). Effects of Apo E are exerted via apoE-receptor-2 (apoER2), which is expressed in platelets, endothelial cells, monocytes, and macrophages33, 34). The binding of apoE to apoER2 has protective effect from atherosclerosis by suppressing the inflammatory function of macrophages, reducing lipid accumulation and cell death35). ApoER2 is a member of the LDLR family, whose structure is similar to that of LDLR with 46% identity36). PCSK9 decreases apoER2 levels with a similar mechanism used for LDLR , namely without using its catalytic activity, by its coexpression or cell surface internalization.

Thereby, PCSK9 inhibits the atheroprotective effects of apoER2 resulting in increased inflammation and foam cell formation16).

PCSK9 in Vascular Inflammation

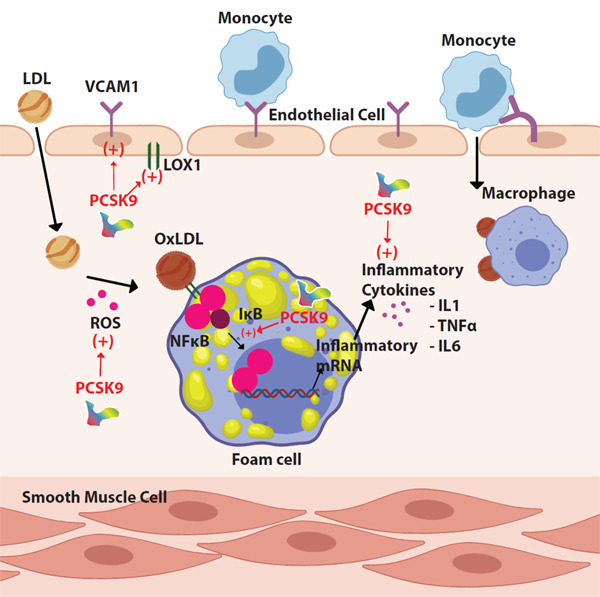

PCSK9 induces inflammation in atherosclerosis independently from its hyperlipidemic effect37). Disturbed ox-LDL uptake/cholesterol efflux balance and accumulation of ox-LDL stimulates the overlying endothelial cells to produce proinflammatory molecule (Fig. 2)1, 38). In addition to ox-LDL accumulation, PCSK9 can directly induce the expression of inflammatory cytokines. Ly6C(hi) monocytes, also called “inflammatory monocytes”, are associated with acute inflammation. They accumulate in inflammatory sites, promoting monocytosis and their local recruitment. In the early atherosclerotic plaques, Ly6C(hi) monocytes infiltrate atherosclerotic lesions and produce activated macrophages, responsible for the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines39). In Apo E knock-out mice (Apo E KO), PCSK9 increases Ly6C(hi) monocytes in spleen and enhance their recruitment in arterial wall40). It increases macrophage response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leading to excessive secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and decreases antiinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-10 (IL10) and arginase41, 42). Silencing PCSK9 decreases the expression of TNF-α, IL-1b, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) in the atherosclerotic aortas of Apo E KO mice43). MCP-1 and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 (CXCL2) are chemokines related to monocyte recruitment. PCSK9 can directly induce expression of these molecules in macrophages42). These proinflammatory effects of PCSK9 are independent of cholesterol but not observed in LDLR −/− mice, suggesting that PCSK9 inflammatory effects on macrophages are mostly via LDLRs40, 42).

Fig. 2.

Inflammation

PCSK9 induces the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules. NF-KB nuclear translocation is induced by PCSK9, leading to an increase in mRNA levels and secretion of inflammatory cytokines.

The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-KB) controls the transcription of many genes that have roles in inflammation and atherosclerosis, including cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, acute phase proteins, regulators of apoptosis, and cell proliferation44). NF-KB, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and damaged mitochondrial DNA have significant roles in PCSK9-mediated ox-LDL uptake29). NF-KB nuclear translocation is induced by PCSK9 overexpression in macrophages, increasing the mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression. Inversely, NF-KB inhibition decreases LPS, ox-LDL, and TNF-α induced PCSK9 expression43). Therefore, it is worth noting that NF-KB has an important signaling role in inflammatory stimulus mediated by PCSK9 expression and PCSK9 accelerates atherosclerotic plaque inflammation through the activation of TLR4/NF-KB pathway29, 43).

The vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) is a protein whose expression increases in inflammatory conditions, mediates the adhesion of lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils to the vascular wall. PCSK9 induces VCAM-1 expression in vascular SMCs, and PCSK9 inhibition in cultured vascular SMCs significantly decreases VCAM-1 expression29).

Dendritic cells that play a role in endothelial inflammation stimulate T cell proliferation and differentiation of naive CD4+T cells into Th1 and Th17 in the existence of ox-LDL. Ox-LDL induces the PCSK9 expression in dendritic cells and increases secretion of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, transforming growth factor beta and IL-10 from dendritic cells45). Differentiation and proliferation of T cells are reduced when PCSK9 is inhibited in dendritic cells45).

PCSK9-Induced Apoptosis

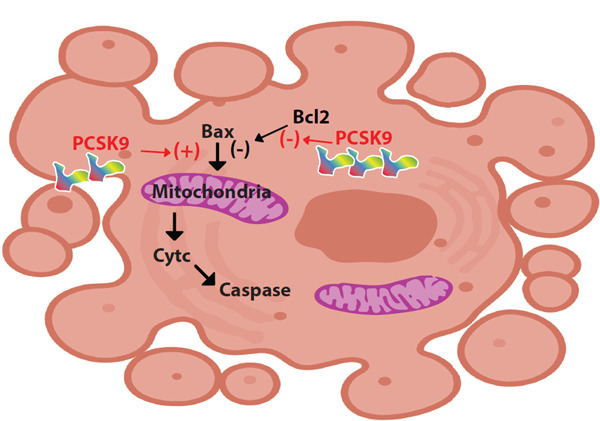

Endothelial cell apoptosis promotes endothelial dysfunction, which is a foundation in the atherosclerosis development. Intrinsic pathway of apoptosis is regulated by B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family proteins. Bax and Bcl2 proteins are members of this family with opposite roles: Bax induces apoptosis, whereas Bcl2 inhibits apoptosis. Ox-LDL induces apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and upregulates the expression of PCSK9 and LOX-1 concentration-dependently (Fig. 3)46). In ox-LDL treated HUVECs, expressions of proapoptotic protein Bax and the activity of caspase9 and caspase3 increase, whereas anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression decreases46). The silencing of PCSK9, with its siRNA, reverses the apoptotic effects of ox-LDL and inhibits apoptosis in endothelial cells46). Therefore, it is suggested that PCSK9 increases apoptosis of HUVECs by Bcl/Bax- caspase9-caspase3 pathway41, 46). PCSK9 inhibition also decreases the phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38, which play an important role in cell apoptosis that is induced by oxidative damage, IL1, TNF-α, and G protein-coupled receptors41).

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis

PCSK9 induces apoptosis of HUVECs by inducing Bax and inhibiting Bcl2.

Autophagy is a protective cellular process of self-digestion of the misfolded proteins and dysfunctional organelles. It aims to promote cell survival under unfavorable conditions such as inflammation and oxidative stress. In the early stages of atherosclerosis, autophagy is protective against macrophage engulfment and local inflammation. However, in late stages, it leads to macrophage death, accelerated inflammation, and thinning of fibrous cap by collagen degradation and can cause acute coronary events47). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an inhibitor of autophagy, whereas mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is the most commonly used introducer of autophagy, providing a possible anti-atherosclerotic effect48). PCSK9 upregulation induces mTOR expression in vascular SMC cultures dose-dependently, whereas inhibition of PCSK9 with its siRNA promotes autophagy and cellular vitality via decreasing mTOR phosphorylation49). Moreover, mTOR pathway is a regulator of LDLR pathway leading to upregulated LDLR expression and inhibited PCSK9 transcription when activated by various signals such as insulin and to decreased LDLR expression and increased PCSK9 expression when inhibited with rapamycin49).

Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced PCSK9 Expression

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are oxygen-containing reactive molecules and can be produced in oxidation reactions in mitochondria and other cellular locations. In inflammatory states, such as atherosclerosis, increase in mitochondrial ROS production provokes endothelial dysfunction, induces the infiltration and activation of inflammatory cells, and increases apoptosis of endothelial and vascular SMCs. Elevated ROS production increases PCSK9 levels23). Mitochondrial ROS leads to PCSK9 and LOX1 increase; the interrelationship of PCSK9 with ROS is strongly supported by the observation that shows a decrease in mtROS in response to LOX-1 or PCSK9 knockdown29). Although ROS inducers pyocyanin and superoxide inducer antimycin-A increase PCSK9 expression, ROS inhibitors such as diphenylene iodonium and apocynin decrease PCSK9 expression in macrophages24).Increased H2O2 production and Nox2 activation are seen in the platelets that are incubated with PCSK9 50).

Shear Stress-Induced PCSK9 Expression

Vascular tone and diameter are under the control of vascular SMCs through the mechanism of contraction51). Vascular SMCs are highly specialized cells of which principal functions are contraction and regulation of blood vessel tone, blood pressure, and blood flow. Local susceptibility to atherosclerosis is regulated by blood flow patterns. Endothelial shear stress is one of the mechanical factors that initiate atherosclerotic plaques. It is the tangential stress derived from the friction of the flowing blood on the endothelial surface of the arterial wall. Low shear stress, which typically occurs in regions of branching or bifurcation regions of the arteries, results in high EC turnover, increased accumulation of LDL, increased oxidative stress, increased DNA synthesis, and higher expression of proinflammatory adhesion molecules; therefore, low shear stress is related to atherosclerosis52). It has been shown that low shear stress (3–6 dyne/cm2) increases PCSK9 expression mostly in the SMCs, and lipid-induced increase in PCSK9 expression is higher at low shear stress23).

PCSK9's Effects on Vascular SMCs

Vascular SMCs within adult blood vessels exhibit a low rate of proliferation and low synthetic activity and express contractile proteins. SMCs in the media express contraction proteins such as alpha-smooth muscle actin, myosin heavy chain II, and calponin, whereas intimal SMCs synthesize extracellular matrix, proteases, and cytokines and have higher migratory and proliferative capacity53, 54). Contractile SMCs can differentiate to a synthetic phenotype with atherogenic stimuli such as shear stress, cytokines, and ROS55). Synthetic SMCs proliferate and migrate more rapidly, synthesize more collagen, increase lipid synthesis, and express higher levels of SRs; therefore, differentiation to synthetic SMC contributes to the formation of foam cells56). PCSK9, which can be induced by resistin, insulin, and hemodynamic shear stress in SMCs, induces SMC differentiation to synthetic phenotype and increases migration and proliferation of synthetic type SMCs23, 57, 58).

PCSK9 deficiency protects arteries partially from neointimal formation59). There is an increased number of the synthetic phenotype of SMCs and increased PCSK9 expression in acute aortic dissection samples60). In aortic dissection with medial aortic calcification (MAC), PCSK9 expression is higher than in aortic dissection without MAC60). Thus, it can be suggested that PCSK9 plays a role in aortic dissection by contributing to the loss of structural integrity of aorta60).

Micro-RNAs Targeting PCSK9 Expression

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs (18–22 nucleotides) that function in RNA silencing and controlling post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression61). They initiate the degradation or inhibit the translation of their target mRNA by binding to the recognition element on the 3′-UTR62). By affecting gene expression, they participate in the regulation of gene expression. Being specific for a given cell and tissue, they influence the phenotype of the cell in which they are expressed. They can be found free in the circulation, bound to proteins or high density lipoprotein (HDL), and in exosomes. By entering body fluids such as blood or urine, they relay signals from the producer cell to distant targets. Their expression has been correlated with various diseases, including coronary artery disease, and they have been reported to be involved in all phases of atherosclerosis, particularly immune cell recruitment and cytokine production63, 64).

Many miRNAs may affect PCSK9 expression65). MiR-17-5p, a potential biomarker for the diagnosis of coronary atherosclerosis, inhibits VLDLR expression in vascular SMCs via direct binding to its 3′-UTR66). Inhibition of miR-17-5p induces upregulation of VLDLR and downregulation of PCSK9 in atherosclerotic apoE −/− mice66). miR-191, miR-222, and miR-224 can bind the 3′ end of the PCSK9 mRNA and thus regulate PCSK9 expression67). When cells are transfected with vectors overexpressing miR-191, miR-222, and miR-224, significant downregulation of PCSK9 is observed67).

Hypomethylation and elevated expression of miR-191 promote epithelial to mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma68). EGR1 (early growth response protein 1) is a zinc finger transcription factor that has a binding site on the PCSK9 promoter. miR-191 targets EGR1 and can regulate PCSK9 expression in different physiological states69).

In a study by Vickers et al., miR-222 level in circulating HDL was found to be 8.2-fold higher in familial hypercholesterolemia patients compared with HDL from normal subjects64). miR-222 regulates insulin sensitivity, and miR-222 levels are higher in plasma of obese human patients70). It is an important regulator in lipid metabolic pathways and a negative regulator of adipocyte differentiation71). It has been reported that miR-222 plays important roles in many physiological and pathological processes in the cardiovascular system; it also plays a role in atherosclerosis and plaque formation72). Moreover, miR-222 has been reported to decrease the PCSK9 expression67).

miR-27a induces an increase in PCSK9 and consequently decreases LDLR levels by 40% via enhancing LDLR degradation73). Silencing PCSK9 repressed miR-27a and, to a lesser extent, let-7c 44).

Further studies are required to delineate the role of miRNAs in PCSK9 regulation.

Conclusion

After its discovery in 2003, knowledge on PCSK9 has gone from bench-to-bedside in less than 9 years, and PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies entered in dyslipidemia guidelines since 2016. Although the role of PCSK9 in LDL metabolism is well defined, recent studies have revealed that it has various effects on many metabolic pathways, including inflammation, sepsis, sodium metabolism, glucose metabolism, and atherosclerosis74–76). Signals of these metabolic pathways also affect PCSK9's level and function77).

It is now clear that PCSK9 contributes to every step of the molecular pathway of atherosclerosis. Despite the rapidly accumulating data on its atherogenic effects, much is still unknown, including its signaling pathways and receptors in atherosclerosis, its acting mechanisms on vascular cells in atherosclerosis, its role in vascular diseases such as aneurysms, its interaction and signal transduction through receptors other than LDLR, the extent of miRNA regulation of PCSK9, and its relevance. Furthermore, it should not be overlooked that, although PCSK9 is a member of the proprotein convertase family, its substrate for convertase activity and why it exists are still unknown. To clarify its role in atherosclerosis and its reason for existence, further research is required.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge use of the services and facilities of the Koç University Research Center for Translational Medicine (KUTTAM), funded by the Presidency of Turkey, Presidency of Strategy and Budget. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Presidency of Strategy and Budget.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1). Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, Tokgözoğlu L, Lewis EF: Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2019; 5: 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN: Mechanisms of foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. J Mol Med (Berl), 2017; 95: 1153-1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Lusis AJ: Atherosclerosis. Nature, 2000; 407: 233-241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L: Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTER-HEART study): case-control study. Lancet, 2004; 364: 937-952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Fernández-Friera L, Fuster V, López-Melgar B, Oliva B, García-Ruiz JM, Mendiguren J, Bueno H, Pocock S, Ibáñez B, Fernández-Ortiz A, Sanz J: Normal LDL-Cholesterol Levels Are Associated With Subclinical Atherosclerosis in the Absence of Risk Factors. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2017; 70: 2979-2991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, Ginsberg HN, Masana L, Descamps OS, Wiklund O, Hegele RA, Raal FJ, Defesche JC, Wiegman A, Santos RD, Watts GF, Parhofer KG, Hovingh GK, Kovanen PT, Boileau C, Averna M, Borén J, Bruckert E, Catapano AL, Kuivenhoven JA, Pajukanta P, Ray K, Stalenhoef AF, Stroes E, Taskinen MR, Tybjærg-Hansen A: Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J, 2013; 34: 3478-3490a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Schulz R, Schlüter KD: PCSK9 targets important for lipid metabolism. Clin Res Cardiol Suppl, 2017; 12: 2-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Seidah NG, Abifadel M, Prost S, Boileau C, Prat A: The Proprotein Convertases in Hypercholesterolemia and Cardiovascular Diseases: Emphasis on Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9. Pharmacol Rev, 2017; 69: 33-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Shapiro MD, Tavori H, Fazio S: PCSK9: From Basic Science Discoveries to Clinical Trials. Circ Res, 2018; 122: 1420-1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Jang HD, Lee SE, Yang J, Lee HC, Shin D, Lee H, Lee J, Jin S, Kim S, Lee SJ, You J, Park HW, Nam KY, Lee SH, Park SW, Kim JS, Kim SY, Kwon YW, Kwak SH, Yang HM, Kim HS: Cyclase-associated protein 1 is a binding partner of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type-9 and is required for the degradation of low-density lipoprotein receptors by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type-9. Eur Heart J, 2020; 41: 239-252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Naureckiene S, Ma L, Sreekumar K, Purandare U, Lo CF, Huang Y, Chiang LW, Grenier JM, Ozenberger BA, Jacobsen JS, Kennedy JD, DiStefano PS, Wood A, Bingham B: Functional characterization of Narc 1, a novel proteinase related to proteinase K. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2003; 420: 55-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Marcinkiewicz J, Jasmin SB, Stifani S, Basak A, Prat A, Chretien M: The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2003; 100: 928-933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Seidah NG, Awan Z, Chrétien M, Mbikay M: PCSK9: a key modulator of cardiovascular health. Circ Res, 2014; 114: 1022-1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Seidah NG, Prat A: The biology and therapeutic targeting of the proprotein convertases. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2012; 11: 367-383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Canuel M, Sun X, Asselin MC, Paramithiotis E, Prat A, Seidah NG: Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) can mediate degradation of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1). PLoS One, 2013; 8: e64145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Poirier S, Mayer G, Benjannet S, Bergeron E, Marcinkiewicz J, Nassoury N, Mayer H, Nimpf J, Prat A, Seidah NG: The proprotein convertase PCSK9 induces the degradation of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and its closest family members VLDLR and ApoER2. J Biol Chem, 2008; 283: 2363-2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Ridker PM, Rifai N, Bradwin G, Rose L: Plasma proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 levels and the risk of first cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J, 2016; 37: 554-560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Tavori H, Giunzioni I, Predazzi IM, Plubell D, Shivinsky A, Miles J, Devay RM, Liang H, Rashid S, Linton MF, Fazio S: Human PCSK9 promotes hepatic lipogenesis and atherosclerosis development via apoE- and LDLR-mediated mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res, 2016; 110: 268-278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Denis M, Marcinkiewicz J, Zaid A, Gauthier D, Poirier S, Lazure C, Seidah NG, Prat A: Gene inactivation of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation, 2012; 125: 894-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Cheng JM, Oemrawsingh RM, Garcia-Garcia HM, Boersma E, van Geuns RJ, Serruys PW, Kardys I, Akkerhuis KM: PCSK9 in relation to coronary plaque inflammation: Results of the ATHEROREMO-IVUS study. Atherosclerosis, 2016; 248: 117-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Ferreira JP, Xhaard C, Lamiral Z, Borges-Canha M, Neves JS, Dandine-Roulland C, LeFloch E, Deleuze JF, Bacq-Daian D, Bozec E, Girerd N, Boivin JM, Zannad F, Rossignol P: PCSK9 Protein and rs562556 Polymorphism Are Associated With Arterial Plaques in Healthy Middle-Aged Population: The STANISLAS Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc, 2020; 9: e014758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Ferri N, Tibolla G, Pirillo A, Cipollone F, Mezzetti A, Pacia S, Corsini A, Catapano AL: Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) secreted by cultured smooth muscle cells reduces macrophages LDLR levels. Atherosclerosis, 2012; 220: 381-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Ding Z, Liu S, Wang X, Deng X, Fan Y, Sun C, Wang Y, Mehta JL: Hemodynamic shear stress via ROS modulates PCSK9 expression in human vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells and along the mouse aorta. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2015; 22: 760-771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Ding Z, Liu S, Wang X, Theus S, Deng X, Fan Y, Zhou S, Mehta JL: PCSK9 regulates expression of scavenger receptors and ox-LDL uptake in macrophages. Cardiovasc Res, 2018; 114: 1145-1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Mehta JL, Sanada N, Hu CP, Chen J, Dandapat A, Sugawara F, Satoh H, Inoue K, Kawase Y, Jishage K, Suzuki H, Takeya M, Schnackenberg L, Beger R, Hermonat PL, Thomas M, Sawamura T: Deletion of LOX-1 reduces atherogenesis in LDLR knockout mice fed high cholesterol diet. Circ Res, 2007; 100: 1634-1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Kume N, Murase T, Moriwaki H, Aoyama T, Sawamura T, Masaki T, Kita T: Inducible expression of lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 in vascular endothelial cells. Circ Res, 1998; 83: 322-327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Ding Z, Liu S, Wang X, Khaidakov M, Dai Y, Mehta JL: Oxidant stress in mitochondrial DNA damage, autophagy and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Sci Rep, 2013; 3: 1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Sawamura T, Kume N, Aoyama T, Moriwaki H, Hoshikawa H, Aiba Y, Tanaka T, Miwa S, Katsura Y, Kita T, Masaki T: An endothelial receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Nature, 1997; 386: 73-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Ding Z, Liu S, Wang X, Deng X, Fan Y, Shahanawaz J, Shmookler Reis RJ, Varughese KI, Sawamura T, Mehta JL: Cross-talk between LOX-1 and PCSK9 in vascular tissues. Cardiovasc Res, 2015; 107: 556-567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Zanotti I, Favari E, Bernini F: Cellular cholesterol efflux pathways: impact on intracellular lipid trafficking and methodological considerations. Curr Pharm Biotechnol, 2012; 13: 292-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Adorni MP, Cipollari E, Favari E, Zanotti I, Zimetti F, Corsini A, Ricci C, Bernini F, Ferri N: Inhibitory effect of PCSK9 on Abca1 protein expression and cholesterol efflux in macrophages. Atherosclerosis, 2017; 256: 1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Mahley RW: Apolipoprotein E: from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders. J Mol Med (Berl), 2016; 94: 739-746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Bai XQ, Peng J, Wang MM, Xiao J, Xiang Q, Ren Z, Wen HY, Jiang ZS, Tang ZH, Liu LS: PCSK9: A potential regulator of apoE/apoER2 against inflammation in atherosclerosis? Clin Chim Acta, 2018; 483: 192-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Leeb C, Eresheim C, Nimpf J: Clusterin is a ligand for apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) and very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and signals via the Reelin-signaling pathway. J Biol Chem, 2014; 289: 4161-4172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Waltmann MD, Basford JE, Konaniah ES, Weintraub NL, Hui DY: Apolipoprotein E receptor-2 deficiency enhances macrophage susceptibility to lipid accumulation and cell death to augment atherosclerotic plaque progression and necrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014; 1842: 1395-1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Reddy SS, Connor TE, Weeber EJ, Rebeck W: Similarities and differences in structure, expression, and functions of VLDLR and ApoER2. Mol Neurodegener, 2011; 6: 3021554715 [Google Scholar]

- 37). Ruscica M, Tokgözoğlu L, Corsini A, Sirtori CR: PCSK9 inhibition and inflammation: A narrative review. Atherosclerosis, 2019; 288: 146-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Leiva E, Wehinger S, Guzmán L, Orrego R: Role of Oxidized LDL in Atherosclerosis. In: Hypercholesterolemia, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 39). Swirski FK, Libby P, Aikawa E, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ: Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. J Clin Invest, 2007; 117: 195-205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Giunzioni I, Tavori H, Covarrubias R, Major AS, Ding L, Zhang Y, DeVay RM, Hong L, Fan D, Predazzi IM, Rashid S, Linton MF, Fazio S: Local effects of human PCSK9 on the atherosclerotic lesion. J Pathol, 2016; 238: 52-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Li J, Liang X, Wang Y, Xu Z, Li G: Investigation of highly expressed PCSK9 in atherosclerotic plaques and ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell apoptosis. Mol Med Rep, 2017; 16: 1817-1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Ricci C, Ruscica M, Camera M, Rossetti L, Macchi C, Colciago A, Zanotti I, Lupo MG, Adorni MP, Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Corsini A, Ferri N: PCSK9 induces a pro-inflammatory response in macrophages. Sci Rep, 2018; 8: 2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Tang ZH, Peng J, Ren Z, Yang J, Li TT, Li TH, Wang Z, Wei DH, Liu LS, Zheng XL, Jiang ZS: New role of PCSK9 in atherosclerotic inflammation promotion involving the TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Atherosclerosis, 2017; 262: 113-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). De Winther MPJ, Kanters E, Kraal G, Hofker MH: Nuclear factor κB signaling in atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2005; 25(5): 904-914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Liu A, Frostegård J: PCSK9 plays a novel immunological role in oxidized LDL-induced dendritic cell maturation and activation of T cells from human blood and atherosclerotic plaque. J Intern Med, 2018; 284: 193-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Wu CY, Tang ZH, Jiang L, Li XF, Jiang ZS, Liu LS: PCSK9 siRNA inhibits HUVEC apoptosis induced by ox-LDL via Bcl/Bax-caspase9-caspase3 pathway. Mol Cell Biochem, 2012; 359: 347-358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Sun Y, Guan X-r: Autophagy: A new target for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Frontiers in Laboratory Medicine, 2018; 2: 68-71 [Google Scholar]

- 48). Cai Z, He Y, Chen Y: Role of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin in Atherosclerosis. Curr Mol Med, 2018; 18: 216-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Ding Z, Liu S, Wang X, Mathur P, Dai Y, Theus S, Deng X, Fan Y, Mehta JL: Cross-Talk Between PCSK9 and Damaged mtDNA in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: Role in Apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2016; 25: 997-1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50). Cammisotto V, Pastori D, Nocella C, Bartimoccia S, Castellani V, Marchese C, Scavalli AS, Ettorre E, Viceconte N, Violi F, Pignatelli P, Carnevale R: PCSK9 Regulates Nox2-Mediated Platelet Activation via CD36 Receptor in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants (Basel), 2020; 9: 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51). Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV: Vascular smooth muscle cell in atherosclerosis. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2015; 214: 33-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52). Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH: Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular, and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2007; 49: 2379-2393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53). Campbell JH, Campbell GR: The role of smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol, 1994; 5: 323-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54). Worth NF, Rolfe BE, Song J, Campbell GR: Vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation in culture is associated with reorganisation of contractile and cytoskeletal proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton, 2001; 49: 130-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55). Orr AW, Hastings NE, Blackman BR, Wamhoff BR: Complex regulation and function of the inflammatory smooth muscle cell phenotype in atherosclerosis. J Vasc Res, 2010; 47: 168-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56). Campbell JH, Popadynec L, Nestel PJ, Campbell GR: Lipid accumulation in arterial smooth muscle cells. Influence of phenotype. Atherosclerosis, 1983; 47: 279-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57). Melone M, Wilsie L, Palyha O, Strack A, Rashid S: Discovery of a new role of human resistin in hepatocyte low-density lipoprotein receptor suppression mediated in part by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2012; 59: 1697-1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58). Costet P, Cariou B, Lambert G, Lalanne F, Lardeux B, Jarnoux AL, Grefhorst A, Staels B, Krempf M: Hepatic PCSK9 expression is regulated by nutritional status via insulin and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c. J Biol Chem, 2006; 281: 6211-6218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59). Ferri N, Marchianò S, Tibolla G, Baetta R, Dhyani A, Ruscica M, Uboldi P, Catapano AL, Corsini A: PCSK9 knock-out mice are protected from neointimal formation in response to perivascular carotid collar placement. Atherosclerosis, 2016; 253: 214-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60). Iida Y, Tanaka H, Sano H, Suzuki Y, Shimizu H, Urano T: Ectopic Expression of PCSK9 by Smooth Muscle Cells Contributes to Aortic Dissection. Ann Vasc Surg, 2018; 48: 195-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61). Liu N, Olson EN: MicroRNA regulatory networks in cardiovascular development. Dev Cell, 2010; 18: 510-525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62). Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N: Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet, 2008; 9: 102-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63). Navickas R, Gal D, Laucevičius A, Taparauskaitė A, Zdanytė M, Holvoet P: Identifying circulating microRNAs as biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Cardiovasc Res, 2016; 111: 322-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64). Martens CR, Bansal SS, Accornero F: Cardiovascular inflammation: RNA takes the lead. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2019; 129: 247-256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65). Momtazi AA, Banach M, Pirro M, Stein EA, Sahebkar A: MicroRNAs: New Therapeutic Targets for Familial Hypercholesterolemia? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2018; 54: 224-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66). Tan L, Meng L, Shi X, Yu B: Knockdown of microRNA-17-5p ameliorates atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE(-/-) mice and restores the expression of very low density lipoprotein receptor. Biotechnol Lett, 2017; 39: 967-976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67). Naeli P, Mirzadeh Azad F, Malakootian M, Seidah NG, Mowla SJ: Post-transcriptional Regulation of PCSK9 by miR-191, miR-222, and miR-224. Front Genet, 2017; 8: 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68). He Y, Cui Y, Wang W, Gu J, Guo S, Ma K, Luo X: Hypomethylation of the hsa-miR-191 locus causes high expression of hsa-mir-191 and promotes the epithelial-tomesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia, 2011; 13: 841-853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69). Di Leva G, Piovan C, Gasparini P, Ngankeu A, Taccioli C, Briskin D, Cheung DG, Bolon B, Anderlucci L, Alder H, Nuovo G, Li M, Iorio MV, Galasso M, Santhanam R, Marcucci G, Perrotti D, Powell KA, Bratasz A, Garofalo M, Nephew KP, Croce CM: Estrogen mediated-activation of miR-191/425 cluster modulates tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells depending on estrogen receptor status. PLoS Genet, 2013; 9: e1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70). Ortega FJ, Mercader JM, Catalán V, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Pueyo N, Sabater M, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Anglada R, Fernández-Formoso JA, Ricart W, Frühbeck G, Fernández-Real JM: Targeting the circulating microRNA signature of obesity. Clin Chem, 2013; 59: 781-792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71). Price NL, Fernández-Hernando C: miRNA regulation of white and brown adipose tissue differentiation and function. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016; 1861: 2104-2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72). Bazan HA, Hatfield SA, O'Malley CB, Brooks AJ, Lightell D, Jr., Woods TC: Acute Loss of miR-221 and miR-222 in the Atherosclerotic Plaque Shoulder Accompanies Plaque Rupture. Stroke, 2015; 46: 3285-3287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73). Alvarez ML, Khosroheidari M, Eddy E, Done SC: MicroRNA-27a decreases the level and efficiency of the LDL receptor and contributes to the dysregulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Atherosclerosis, 2015; 242: 595-604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74). Walley KR, Thain KR, Russell JA, Reilly MP, Meyer NJ, Ferguson JF, Christie JD, Nakada TA, Fjell CD, Thair SA, Cirstea MS, Boyd JH: PCSK9 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and septic shock outcome. Sci Transl Med, 2014; 6: 258ra143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75). Sharotri V, Collier DM, Olson DR, Zhou R, Snyder PM: Regulation of epithelial sodium channel trafficking by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). J Biol Chem, 2012; 287: 19266-19274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76). Mbikay M, Sirois F, Mayne J, Wang GS, Chen A, Dewpura T, Prat A, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Scott FW: PCSK9-deficient mice exhibit impaired glucose tolerance and pancreatic islet abnormalities. FEBS Lett, 2010; 584: 701-706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77). Spolitu S, Okamoto H, Dai W, Zadroga JA, Wittchen ES, Gromada J, Ozcan L: Hepatic Glucagon Signaling Regulates PCSK9 and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol. Circ Res, 2019; 124: 38-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]