Abstract

Aim: Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is an independent predictor of stroke and dementia, in which subclinical cerebrovascular diseases (SCVDs) play a vital pathogenetic role. However, few studies have described the association between CAC and SCVDs. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the clinical relationship between CAC and SCVDs in a healthy Japanese male population.

Methods: In this observational study, 709 men, free of stroke, were sampled from a city in Japan from 2010 to 2014. CAC was scored using the Agatston method. The following SCVDs were assessed using magnetic resonance imaging: intracranial arterial stenosis (ICAS), lacunar infarction, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity (DSWMH), periventricular hyperintensity (PVH), and microbleeds. The participants were categorized according to CAC scores as follows: no CAC (0), mild CAC (1–100), and moderate-to-severe CAC (> 100). The adjusted odds ratios of prevalent SCVDs were computed in reference to the no-CAC group using logistic regression.

Results: The mean (standard deviation) age of the participants was 68 (8.4) years. Participants in the moderate-to-severe CAC category showed significantly higher odds of prevalent lacunar infarction, DSWMH, and ICAS in age-adjusted and risk-factor-adjusted models. Microbleeds and PVH, in contrast, did not show any significant associations. The trends for CAC with lacunar infarction, DSWMH, and ICAS were also significant (all P-values for trend ≤ 0.02).

Conclusions: Higher CAC scores were associated with higher odds of lacunar infarction, DSWMH, and ICAS. The presence and degree of CAC may be a useful indicator for SCVDs involving small and large vessels.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Coronary artery calcification, Subclinical cerebrovascular diseases

Introduction

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a wellestablished marker of atherosclerosis1) and is known to predict noncardiac diseases, including stroke2) and dementia3). Subclinical cerebrovascular diseases (SCVDs), involving both small and large vessels, are likely to play an important role in the pathogenesis of stroke and dementia4, 5). The speculated mechanism for CAC to predict stroke and dementia is the coexistence of SCVDs with CAC3). Yet, studies examining the magnitude and pattern of coexistence between SCVDs and CAC in the general population are scarce5–7). Furthermore, in the traditional view, CAC is considered a marker of atheromatous change (i.e., atherosclerosis)5, 8), whereas cerebral small-vessel diseases are associated with arteriolosclerosis4). Therefore, it remains uncertain whether CAC is a good marker for intracranial arteriolosclerosis in the general population. Moreover, examining and comparing the relationships of CAC and SCVDs with conventional cardiovascular risk factors may help better understand the pattern of association between CAC and each SCVD.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as compared to transcranial Doppler, is a suitable method for assessing SCVDs in a community-based sample given its noninvasive nature and its superiority in assessing intracranial arterial stenosis (ICAS)9). In MRI of the brain, cerebral small-vessel diseases often manifest as lacunar infarction, white matter lesions, and microbleeds7), whereas large-vessel diseases, such as ICAS, are detected as stenotic lesions of major cerebral arteries10).

We hypothesized that, in a population-based sample of men, CAC would be related not only to large-vessel but also to small-vessel diseases of the brain and, thus, would be a useful marker for SCVDs given the systemic nature of atherosclerosis and/or arteriolosclerosis. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the extent of association between CAC and SCVDs in a general Japanese male population. Secondarily, the aim of the study was also to describe the relationship of conventional vascular risk factors with CAC and SCVDs.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

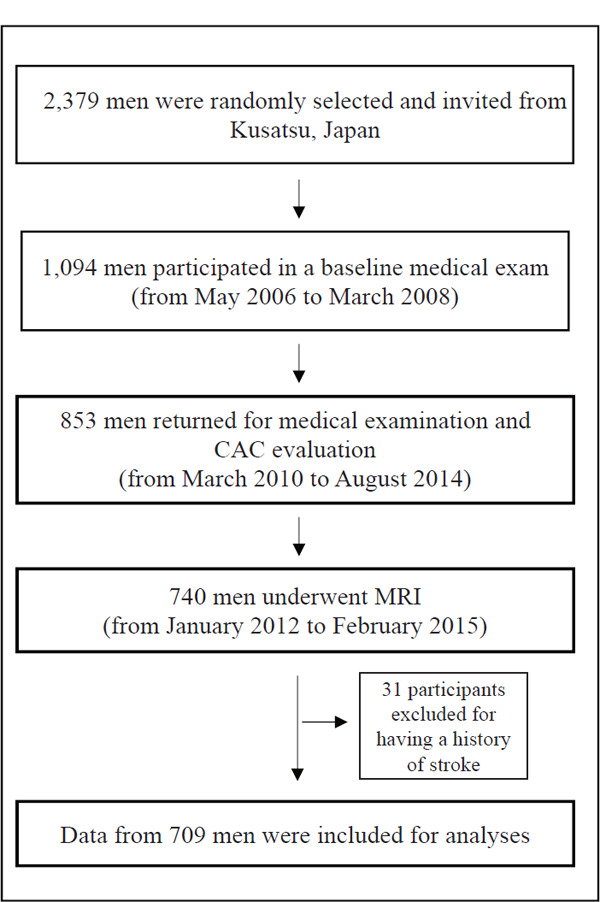

This was an observational study that included men who participated in the Shiga Epidemiological Study of Subclinical Atherosclerosis (SESSA). The enrollment methods have been reported previously9, 11). In brief, from May 2006 to March 2008, 2,379 Japanese men aged 40–79 were randomly selected and invited on the basis of the residents' registry of Kusatsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan. A total of 1,094 men agreed to participate and underwent a baseline medical exam. Of the 853 male residents who returned for a follow-up examination, which included a CAC assessment (from March 2010 to August 2014), 740 men underwent additional cerebral MRI and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) between January 2012 and February 2015. A total of 709 men were included in the present analyses after excluding 31 participants who had a history of stroke at the time of the CAC assessment (Fig. 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. This study was carried out following the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shiga University of Medical Science.

Fig. 1.

Participants' selection flow chart

CAC

CAC was assessed using 64-channel multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT) scans using an Aquilion scanner (Aquilion™ 64; Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired from the level of the root of the aorta through the heart at a slice thickness of 3.0 mm with a scan time of 250 ms. Images were obtained at 70% of the cardiac cycle using electrocardiogram triggering during a single breath-hold. A DICOM workstation and AccuImage software (AccuImage Diagnostics, South San Francisco, CA, USA) were used for the quantification of CAC. The presence of CAC was defined as a minimum of three contiguous pixels (area = 1 mm2) with a density of ≥ 130 Hounsfield units. A physician trained in CT reading at the Cardiovascular Institute of the University of Pittsburgh and blinded to the clinical information of the participants read all the CT images and calculated the CAC scores according to the Agatston method12).

Cerebral MRI/MRA

All MRI and MRA scans were performed using a 1.5-Tesla MR scanner (Signa HDxt 1.5T, ver. 16; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Three-dimensional T1-weighted spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR), T2- and T2*-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and time-of-flight (TOF) MRA scans were performed for diagnosing small-vessel diseases and cerebral artery stenosis. The T2- and T2*-weighted and FLAIR images were 4 mm thick with no interslice gaps. Two neurosurgeons (KN, AS), certified by the Japan Neurosurgical Society, independently assessed all MRI/MRA images in duplicate without knowledge of the participants' characteristics. Disagreement in assessment was resolved with adjudication by the neurosurgeons9).

Cerebral Small-Vessel Diseases

Lacunar infarction was defined as an area of low signal intensity on a T1-weighted image with a size of 3–15 mm and visible as a hyperintense lesion on a T2-weighted image. The irregular shape of the lacuna in SPGR and its surrounding gliosis in FLAIR images were considered when differentiating these lesions from an enlarged perivascular space. For each anatomical segment (basal ganglia, brainstem, thalamus, and white matter, among others), the lacunar infarctions were counted and graded as 0, 1–2, or ≥ 3.

White matter lesions were defined as hyperintense regions on FLAIR images. These were subgrouped into either deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity (DSWMH) or white matter periventricular hyperintensity (PVH). DSWMH and PVH were graded according to the classifications proposed by Shinohara and colleagues13), which were adopted by the Japanese Brain Dock Guidelines in 2014 14) and are similar to the ones proposed by Fazekas15). DSWMH was classified as follows: no lesion (grade 0), spotty clear boundary lesion with < 3 mm maximum diameter of enlarged perivascular cavity (grade 1), patchy and scattered lesion of subcortex to deep white matter with ≥ 3 mm maximum diameter (grade 2), deep fused white matter lesion with unclear boundary (grade 3), and largely fused white matter lesion (grade 4). PVH was graded as follows: no lesion or only a periventricular rim (grade 0), localized PVH such as on the periventricular cap (grade 1), slightly thick PVH covering the periventricular area (grade 2), diffused PVH expanding to a deep white matter lesion (grade 3), and large PVH expanding to a deep white matter or subcortex lesion (grade 4).

Microbleeds were defined as hypointense (or signal-void) lesions on T2*-weighted images. We counted the number of microbleeds for each of the following anatomical segments: white matter, basal ganglia, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, and thalamus.

ICAS

We evaluated 11 intracranial arteries for stenosis. These included the basilar artery plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery9). For each artery, the degree of narrowing was graded using criteria established in the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease trial16) as follows: no detectable stenosis, 1–49% stenosis, 50–99% stenosis, and complete occlusion (100%).

Covariates

Demographic data, medical history, use of medications, and lifestyle factors, including smoking and alcohol habits, were collected from each participant using a self-administered questionnaire. Trained research technicians confirmed the completed questionnaire with the participants. Smoking habits were categorized as either “current,” “past (those who quit and did not smoke for at least the last 30 days prior to the study),” or “never.” Similarly, drinking habits were categorized either as “current,” “past,” or “never.” Bodyweight and height were measured while the participant was wearing light clothing without shoes. Blood pressure was measured twice consecutively from the participants' right arms while seated after they emptied their bladders for a urinalysis and sat quietly for 5 min, using an automated sphygmomanometer (BP-8800; Colin Medical Technology, Komaki, Japan) with an appropriately sized cuff. The average of two measurements was used for analysis. A blood sample was obtained early in a clinical visit after a 12 h fast and used for laboratory testing, including lipids and glucose concentrations. The samples were centrifuged (3,000 rpm for 15 min) at 4 °C within 90 min of collection. Serum lipid concentrations were determined at a single laboratory (Shiga Laboratory; MEDIC, Shiga, Japan) that had been certified for standardized lipid measurements according to the protocols of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Cholesterol Reference Method Laboratory Network17). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-cholesterol) was calculated using the Friedewald equation18). When the concentration of triglycerides exceeded 400 mg/dL, the concentration of LDL-cholesterol was treated as missing. Fasting glucose concentration was measured from NaF-treated plasma using a hexokinase glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase enzymatic assay. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured by the latex agglutination immunoassay according to either the protocol of the Japan Diabetes Society (JDS) or that of the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP)19). We converted JDS values to NGSP values using the following formula: NGSP (%) = 1.02 × JDS (%) + 0.25%19). Body mass index (BMI) was defined as body weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg, or the use of any antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose of ≥ 126 mg/dL, or HbA1c (NGSP) of ≥ 6.5%19), or the use of any antidiabetic medication.

Statistical Analysis

We categorized the participants into three groups according to the CAC score as follows: 0 (no CAC), 1–100 (mild CAC), and > 100 (moderate-to-severe CAC). We dichotomized each of the four small-vessel diseases and ICAS as follows: lacunar infarction (defined as number of lesions ≥ 1), DSWMH (grade ≥ 3)20), PVH (grade ≥ 2)20), microbleeds (defined as number of lesions ≥ 1), and presence of ICAS (defined as stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in any of the arteries assessed)9).

Descriptive statistics of the participants are presented as the mean (standard deviations) for continuous variables and as number (percentage) for categorical variables. The distributions of clinical and laboratory variables in relation to the CAC category were also examined. Variable trends, according to CAC groups, were computed using the Mantel–Haenszel chi-squared test for the categorical variables and linear regression for the continuous variables.

For the primary aim (“main analyses”), crude and adjusted estimates of prevalent SCVDs (%) for each CAC group were calculated following standard analysis-of-covariance techniques and binary logistic regression models. For the secondary aim, we computed the odds ratios (ORs) of conventional cardiovascular risk factors associated with a CAC score of > 0, as well as with each prevalent SCVD (dichotomized as in the main analysis) using logistic regression. In this secondary analysis, conventional risk factors were treated in the following fashion: age (per five years), systolic blood pressure (per 10 mmHg), LDL-cholesterol (per 10 mg/dL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol) (per 5 mg/dL), triglycerides (per 10 mg/dL), use of antihypertensive or lipid-lowering medications (yes), diabetes (yes), and smoking and drinking habits (current/past versus never), all of which were simultaneously adjusted for in the model. In order to avoid overadjustment, the BMI was not included in the model because of its association with conventional risk factors, such as elevated blood pressure, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

In the main analyses, ORs and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for prevalent SCVDs according to the CAC category (reference: CAC score = 0). First, the model was unadjusted. Second, the model was adjusted for age in years (“age-adjusted model”). Third, we explored the model that was further adjusted for conventional cardiovascular risk factors: systolic blood pressure (mmHg), antihypertensive medication users (yes/no, two missing), LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL, 10 missing), HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL, three missing), triglycerides (mg/dL, three missing), lipid-lowering medication(s) (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no, three missing), and smoking and drinking habits (current, past, and never) (“risk-factor-adjusted model”). We considered the risk-factor-adjusted model as exploratory. The rationale behind conducting the risk-factor-adjusted model was to test the predictability of CAC for SCVDs independent of conventional cardiovascular risk factors. We did not consider those risk factors to be confounders because we think that the association between CAC and SCVDs, even if it exists, is not causal, whereas some of the risk factors are causally associated with both CAC and SCVDs to some extent. In the risk-factor-adjusted model, a total of 697 observations were analyzed, after excluding those with missing values used in the explanatory model. P-values for trend were calculated using the logistic regression model with the median value of the CAC score inserted for each CAC group. As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the analyses using natural-log-transformed CAC score + 1, that is, ln (CAC + 1), instead of the CAC groups.

We repeated the main analyses stratified by age (< 70 and ≥ 70 years) and hypertension status (absent and present) to examine potential differences. The risk-factor-adjusted model was not performed in those stratified analyses, as the model was exploratory. We determined the interaction by age group or hypertension status on the associations between CAC and SCVDs by inserting a product term (stratum-specific median CAC score×stratum) in the model.

All analyses were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The mean (standard deviation) age and median (interquartile range) CAC scores of all the participants were 68 (8.4) years and 30 (0, 185), respectively. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study participants (n = 709) according to the CAC category.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| CAC category (CAC scores) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Moderate to severe | P for trend§ | |||

| All participants | No (0) | Mild (1–100) | (> 100) | ||

| N = 709 | n = 233 | n = 236 | n = 240 | ||

| Age, years | 68.0 (8.4) | 64.8 (9.2) | 68.5 (8.1) | 70.7 (6.7) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.3 (2.9) | 23.0 (2.9) | 23.2 (2.7) | 23.7 (3.0) | 0.016 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 132 (17) | 128 (16) | 132 (15) | 135 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 77 (11) | 77 (11) | 77 (10) | 77 (11) | 0.605 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 202 (34) | 203 (33) | 204 (34) | 200 (35) | 0.494 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 122 (81) | 115 (68) | 120 (83) | 130 (90) | 0.052 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 60 (16) | 61 (16) | 60 (16) | 58 (17) | 0.041 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 119 (31) | 119 (32) | 121 (29) | 117 (31) | 0.551 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 102 (22) | 98 (18) | 103 (23) | 105 (24) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c | 5.9 (0.8) | 5.8 (0.6) | 6.0 (1.0) | 6.0 (0.8) | 0.004 |

| Antihypertensive medication users, n (%) | 269 (38) | 59 (26) | 92 (39) | 118 (49) | < 0.001 |

| Lipid lowering medication users, n (%) | 152 (21) | 30 (13) | 48 (20) | 74 (31) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 395 (56) | 100 (43) | 129 (55) | 166 (69) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 155 (22) | 22 (09) | 57 (24) | 76 (32) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.997 | ||||

| Current | 140 (20) | 53 (23) | 42 (18) | 45 (19) | |

| Past | 423 (60) | 131 (56) | 138 (58) | 154 (64) | |

| Never | 146 (21) | 49 (21) | 56 (24) | 41 (17) | |

| Drinking, n (%) | 0.967 | ||||

| Current | 573 (81) | 192 (82) | 184 (78) | 197 (82) | |

| Past | 33 (5) | 10 (4) | 12 (5) | 11 (5) | |

| Never | 103 (15) | 31 (13) | 40 (17) | 32 (13) | |

| Lacunar infarction, n (%) | 141 (20) | 22 (9) | 49 (21) | 70 (29) | < 0.001 |

| DSWMH, n (%) | 150 (21) | 34 (15) | 47 (20) | 69 (29) | < 0.001 |

| PVH, n (%) | 173 (24) | 41 (18) | 61 (26) | 71 (30) | 0.003 |

| Microbleeds, n (%) | 93 (13) | 21 (9) | 35 (15) | 37 (15) | 0.040 |

| ICAS, n (%) | 204 (29) | 35 (15) | 68 (29) | 101 (42) | < 0.001 |

| CAC scores, | |||||

| median value (IQR) | 30 (0, 185) | 0 (0, 0) | 27 (12, 57) | 348 (179, 774) | < 0.001 |

The numbers are means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

P-values for trend were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel chi-squared test for a categorical variable and linear regression for a continuous variable.

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; HDL-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; IQR, inter-quartile range; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity.

Definitions: Age, assessed at the examination for risk factor and CAC (2010–2014); hypertension, systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or use of any antihypertensive medication; diabetes, a fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (NGSP) ≥ 6.5% or use of any antidiabetic medication; lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

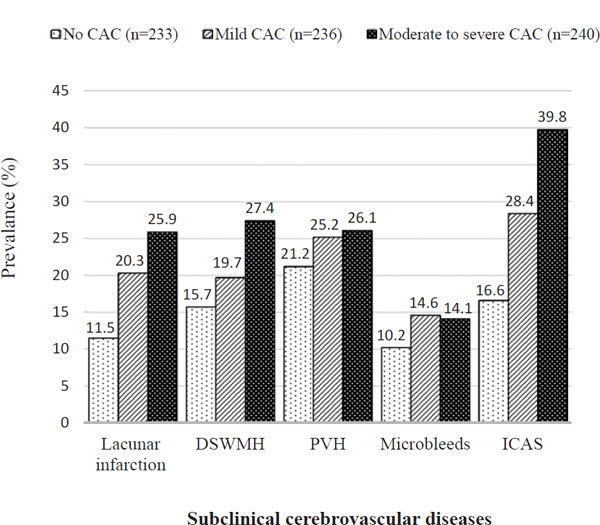

The number (percentage) of participants who had no CAC, mild CAC, or moderate-to-severe CAC was 233 (33), 236 (33), and 240 (34), respectively. Participants with higher CAC scores tended to be older and to have a higher BMI, systolic blood pressure, and fasting glucose and were more likely to use medication(s) for hypertension and dyslipidemia and to have hypertension and diabetes. The prevalence of SCVD components individually showed significant upward trends across the CAC categories. We compared the characteristics at baseline (from May 2006 to March 2008) between those who were analyzed (n = 709) and those who were not (n = 385). We found that older, more hypertensive, current smokers tended to be excluded (Supplementary Table 1). The ageadjusted prevalence of lacunar infarction, DSWMH, PVH, microbleeds, and ICAS were higher in the groups with higher CAC scores (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Supplementary Table 1. Differences in characteristics at baseline (2006–2008) between participants who were analyzed and those not analyzed in the study: Shiga Epidemiological Study of Subclinical Atherosclerosis (SESSA), Shiga.

| Participants analyzed | Participants not analyzed | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 709) | (n = 385) | ||

| Age, years | 63.5 (9.5) | 65.1 (10.7) | < 0.01 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 374 (53) | 239 (62) | < 0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 136 (18) | 138 (21) | 0.02 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.6 (2.8) | 23.6 (3.2) | 0.87 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 159 (19) | 82 (21) | 0.68 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.43 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 60 (17) | 57 (17) | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 126 (83) | 129 (76) | 0.49 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 126 (30) | 122 (33) | 0.05 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 210 (33) | 205 (35) | 0.01 |

| Antihypertensive medication use, no. (%) | 194 (27) | 122 (32) | 0.13 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, no. (%) | 75 (11) | 49 (13) | 0.28 |

| Diabetic medication use, no. (%) | 60 (9) | 31 (8) | 0.81 |

| Smoking habit, no. (%) | |||

| Never | 138 (20) | 48 (13) | < 0.01 |

| Past | 363 (51) | 195 (51) | |

| Current | 208 (29) | 142 (37) | |

| Drinking habit, no. (%) | |||

| Never | 109 (15) | 88 (23) | < 0.01 |

| Past | 37 (5) | 27 (7) | |

| Current | 563 (79) | 270 (70) |

The numbers are means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: HDL-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Definitions: Hypertension, systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or antihypertensive medication use; diabetes, a fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (NGSP) ≥ 6.5% or anti-diabetic medication use.

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Age-adjusted prevalence of subclinical cerebrovascular diseases according to coronary artery calcification category (N = 709 men aged 46–83 years)

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis.

Definitions: No CAC, CAC score 0; mild CAC, CAC scores 1 to 100; moderate to severe CAC, CAC scores > 100; lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

CAC showed a significant positive association with age, higher systolic blood pressure, diabetes, and the use of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication(s) (Table 2). ICAS was significantly positively associated with age, higher systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication(s), higher LDL-cholesterol, and lower HDL-cholesterol. In contrast, all the components of cerebral small-vessel diseases (i.e., lacunar infarction, DSWMH, PVH, and microbleeds) were positively associated with age and either systolic blood pressure or use of antihypertensive medication(s), or both, but not with other conventional risk factors, except PVH. Use of lipid lowering medication(s) was negatively associated with PVH.

Table 2. Multivariable-adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of prevalent subclinical cerebrovascular diseases for conventional cardiovascular risk factors (N = 697)§.

| CAC | Lacunar infarction | DSWMH | PVH | Microbleeds | ICAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors (interval/response) | ORs (95% CI) | ORs (95% CI) | ORs (95% CI) | ORs (95% CI) | ORs (95% CI) | ORs (95% CI) |

| Age (5 years) | 1.37 (1.23, 1.53)** | 1.55 (1.31, 1.83)** | 1.20 (1.05, 1.36)** | 1.52 (1.32, 1.76)** | 1.25 (1.06, 1.47)** | 1.23 (1.09, 1.39)** |

| Systolic blood pressure (10 mmHg) | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30)** | 1.23 (1.09, 1.38)** | 1.02 (0.91, 1.13) | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) | 1.24 (1.09, 1.42)** | 1.29 (1.16, 1.44)** |

| Antihypertensive medication (yes) | 1.53 (1.04, 2.26)* | 2.17 (1.43, 3.28)** | 1.65 (1.11, 2.44)* | 1.70 (1.16, 2.49)** | 1.05 (0.65, 1.70) | 1.75 (1.20, 2.53)** |

| LDL-cholesterol (10 mg/dL) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.10) | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | 1.11 (1.04, 1.18)** |

| HDL-cholesterol (5 mg/dL) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.10) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.09) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.86 (0.80, 0.92)** |

| Triglycerides (10 mg/dL) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.01) |

| Lipid lowering medication (yes) | 1.74 (1.07, 2.84)* | 0.98 (0.60, 1.59) | 0.80 (0.49, 1.29) | 0.60 (0.37, 0.98)* | 0.82 (0.45, 1.50) | 1.50 (0.97, 2.32) |

| Diabetes (yes) | 3.04 (1.81, 5.10)** | 1.35 (0.85, 2.12) | 1.15 (0.74, 1.80) | 1.11 (0.72, 1.71) | 0.82 (0.46, 1.45) | 1.23 (0.81, 1.87) |

| Smoking: | ||||||

| Current (vs never) | 0.99 (0.57, 1.72) | 1.14 (0.59, 2.22) | 1.01 (0.56, 1.83) | 1.16 (0.64, 2.13) | 0.97 (0.45, 2.11) | 1.31 (0.73, 2.35) |

| Past (vs never) | 1.09 (0.70, 1.71) | 0.96 (0.57, 1.60) | 0.77 (0.48, 1.23) | 0.99 (0.62, 1.59) | 1.12 (0.62, 2.03) | 1.38 (0.87, 2.20) |

| Drinking: | ||||||

| Current (vs never) | 0.95 (0.57, 1.57) | 1.11 (0.61, 2.01) | 1.37 (0.77, 2.44) | 1.07 (0.63, 1.85) | 2.07 (0.91, 4.71) | 0.72 (0.44, 1.17) |

| Past (vs never) | 0.90 (0.36, 2.25) | 1.57 (0.59, 4.21) | 1.37 (0.50, 3.73) | 2.17 (0.89, 5.28) | 1.06 (0.25, 4.49) | 0.97 (0.41, 2.31) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01.

All the risk factors listed in the table were simultaneously adjusted using logistic regression where CAC, lacunar infarction, DSWMH, PVH, microbleeds, and ICAS were used separately as dependent variables.

A total of 697 observations were analyzed, after excluding those with missing values of explanatory variables (antihypertensive medication, two missing; LDL-cholesterol, 10 missing; HDL-cholesterol, three missing; triglycerides, three missing; diabetes, three missing).

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; CI, confidence interval; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; HDL-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ORs, odds ratio; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity.

Definitions: Age, assessed at the examination for risk factor and CAC (2010–2014); diabetes, a fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (NGSP) ≥ 6.5% or use of any antidiabetic medication; CAC, CAC scores > 0; lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

Table 3 shows the ORs of prevalent SCVDs in the higher-CAC groups when referencing the no-CAC group. In the age-adjusted model, higher CAC was associated with higher odds of prevalent lacunar infarction, DSWMH, and ICAS in a graded manner (P-values for trend < 0.01), but not with prevalent PVH or microbleeds. In the risk-factor-adjusted model, the results were similar. In the sensitivity analyses using continuous CAC score [ln (CAC + 1)], the results were very similar quantitatively to the main ones (Supplementary Table 2). In age-stratified analyses, the associations were similar to those of the main analyses in both age groups (Table 4). Although the graded association across the CAC groups appeared to be stronger in the older group for lacunar infarction and ICAS and in the younger group for DSWMH and ICAS, there was no statistical evidence supporting the interaction by age group between CAC and prevalent SCVDs (P-values for interaction > 0.082). In hypertension-stratified analyses (Table 5), the hypertensive group showed associations similar to those in the main analyses. Even in the no-hypertension group, lacunar infarction and ICAS showed a significant positive association with higher CAC. There was no statistical evidence supporting the interaction by hypertension status on the association between CAC and prevalent SCVDs (P-values for interaction > 0.531).

Table 3. Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of prevalent subclinical cerebrovascular diseases according to coronary artery calcification category.

| CAC category (CAC scores) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Mild | Moderate to severe | P for trend§ | |

| (0) | (1–100) | (> 100) | ||

| n = 233 | n = 236 | n = 240 | ||

| Lacunar infarction | ||||

| N (%) | 22 (9) | 49 (21) | 70 (29) | |

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 2.51 (1.46, 4.31)** | 3.95 (2.35, 6.64)** | < 0.001 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 2.02 (1.16, 3.52)* | 2.83 (1.65, 4.83)** | 0.001 |

| Risk factor adjusted model‡ | Reference | 1.75 (0.98, 3.14) | 2.30 (1.29, 4.09)** | 0.020 |

| DSWMH | ||||

| N (%) | 34 (15) | 47 (20) | 69 (29) | |

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.46 (0.90, 2.36) | 2.36 (1.49, 3.74)** | < 0.001 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.32 (0.81, 2.16) | 2.03 (1.26, 3.27)** | 0.003 |

| Risk factor adjusted model‡ | Reference | 1.42 (0.85, 2.37) | 2.19 (1.32, 3.65)** | 0.004 |

| PVH | ||||

| N (%) | 41 (18) | 61 (26) | 71 (30) | |

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.63 (1.05, 2.55)* | 1.97 (1.27, 3.04)** | 0.015 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.27 (0.80, 2.03) | 1.34 (0.85, 2.12) | 0.384 |

| Risk factor adjusted model‡ | Reference | 1.31 (0.80, 2.12) | 1.38 (0.85, 2.26) | 0.379 |

| Microbleeds | ||||

| N (%) | 21 (9) | 35 (15) | 37 (15) | |

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.76 (0.99, 3.12) | 1.84 (1.04, 3.25)* | 0.156 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.51 (0.84, 2.70) | 1.45 (0.80, 2.60) | 0.533 |

| Risk factor adjusted model‡ | Reference | 1.61 (0.87, 2.96) | 1.32 (0.70, 2.51) | 0.972 |

| ICAS | ||||

| N (%) | 35 (15) | 68 (29) | 101 (42) | |

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 2.29 (1.45, 3.62)** | 4.11 (2.64, 6.39)** | < 0.001 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 2.03 (1.27, 3.22)** | 3.40 (2.16, 5.36)** | < 0.001 |

| Risk factor adjusted model‡ | Reference | 1.77 (1.08, 2.90)* | 2.63 (1.60, 4.31)** | < 0.001 |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01;

P-values for trend were calculated using the logistic regression applying the median value of the CAC score for each group.

In the risk factor adjusted model, a total of 697 observations were analyzed, after excluding those with missing values of explanatory variables.

Adjusting covariates for risk factor adjusted model: age (year), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), antihypertensive medication (two missing), LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL, 10 missing), HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL, three missing), triglycerides (mg/dL, three missing), lipid-lowering medication, diabetes (three missing), smoking, and drinking habits (current, past, never).

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; HDL-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity.

Definitions: Age, assessed at the examination for risk factor and CAC (2010–2014); hypertension, systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or use of any antihypertensive medication; diabetes, a fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (NGSP) ≥ 6.5% or use of any antidiabetic medication; lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

Supplementary Table 2. Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of prevalent subclinical cerebrovascular diseases according to per standard deviation (1.13) of coronary artery calcification scores in log scale (ln (CAC + 1)).

| ORs (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Lacunar infarction | ||

| Unadjusted model | 1.70 (1.40, 2.07) | < 0.001 |

| Age-adjusted model | 1.48 (1.21, 1.81) | < 0.001 |

| Risk factor adjusted model§ | 1.33 (1.07, 1.65) | 0.012 |

| DSWMH | ||

| Unadjusted model | 1.38 (1.17, 1.62) | < 0.001 |

| Age-adjusted model | 1.35 (1.11, 1.63) | 0.002 |

| Risk factor adjusted model§ | 1.38 (1.12, 1.70) | 0.002 |

| PVH | ||

| Unadjusted model | 1.26 (1.08, 1.47) | 0.003 |

| Age-adjusted model | 1.11 (0.92, 1.33) | 0.286 |

| Risk factor adjusted model§ | 1.11 (0.91, 1.35) | 0.304 |

| Microbleeds | ||

| Unadjusted model | 1.24 (1.02, 1.51) | 0.031 |

| Age-adjusted model | 1.15 (0.92, 1.45) | 0.225 |

| Risk factor adjusted model§ | 1.11 (0.87, 1.43) | 0.401 |

| ICAS | ||

| Unadjusted model | 1.71 (1.47, 2.00) | < 0.001 |

| Age-adjusted model | 1.70 (1.42, 2.04) | < 0.001 |

| Risk factor adjusted model§ | 1.54 (1.26, 1.88) | < 0.001 |

In the risk factor adjusted model, a total of 697 observations were analyzed, after excluding those with missing values of explanatory variables.

Adjusting covariates for risk factor adjusted model: age (year), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), antihypertensive medication (2 missing), LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL, 10 missing), HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL, 3 missing), triglycerides (mg/dL, 3 missing), lipid-lowering medication, diabetes (3 missing), smoking, and drinking habits (current, past, never).

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; CI, confidence interval; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; HDL-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ORs, odds ratio; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity.

Definitions: Age, assessed at the examination for risk factor and CAC (2010–2014); hypertension, systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or antihypertensive medication use; diabetes, a fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or HbA1c (NGSP) ≥ 6.5% or anti-diabetic medication use; lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; Microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

Table 4. Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of prevalent subclinical cerebrovascular diseases according to coronary artery calcification category by age-strata (< 70 and ≥ 70 years).

| age < 70 years (n = 380) |

age ≥ 70 years (n = 329) |

P for interaction‡ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC category (CAC scores) |

P for trend§ | CAC category (CAC scores) |

P for trend§ | ||||||

| Moderate to severe | Moderate to severe | ||||||||

| No (0) | Mild (1–100) | (> 100) | No (0) | Mild (1–100) | (>100) | ||||

| n = 159 | n = 118 | n = 103 | n = 74 | n = 118 | n = 137 | ||||

| Lacunar infarction | |||||||||

| N (%) | 14 (9) | 18 (15) | 17 (17) | 08 (11) | 31 (26) | 53 (39) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.86 (0.89, 3.92) | 2.05 (0.96, 4.36) | 0.158 | Reference | 2.94 (1.27, 6.81)* | 5.20 (2.31, 11.70)** | < 0.001 | 0.608 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.61 (0.75, 3.43) | 1.51 (0.70, 3.28) | 0.537 | Reference | 2.91 (1.25, 6.77)* | 4.92 (2.18, 11.13)** | < 0.001 | 0.300 |

| DSWMH | |||||||||

| N (%) | 17 (11) | 23 (19) | 27 (26) | 17 (23) | 24 (20) | 42 (31) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 2.02 (1.03, 3.99)* | 2.97 (1.52, 5.79)** | 0.005 | Reference | 0.86 (0.42, 1.73) | 1.48 (0.77, 2.85) | 0.060 | 0.168 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.86 (0.93, 3.68) | 2.49 (1.26, 4.93)** | 0.028 | Reference | 0.87 (0.43, 1.77) | 1.55 (0.80, 3.00) | 0.045 | 0.250 |

| PVH | |||||||||

| N (%) | 16 (10) | 18 (15) | 21 (20) | 25 (34) | 43 (36) | 50 (37) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.61 (0.78, 3.31) | 2.29 (1.13, 4.63)* | 0.038 | Reference | 1.12 (0.61, 2.07) | 1.13 (0.62, 2.04) | 0.824 | 0.082 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.35 (0.64, 2.82) | 1.62 (0.78, 3.34) | 0.262 | Reference | 1.14 (0.62, 2.11) | 1.18 (0.65, 2.14) | 0.720 | 0.181 |

| Microbleeds | |||||||||

| N (%) | 11 (7) | 14 (12) | 14 (14) | 10 (14) | 21 (18) | 23 (17) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.81 (0.79, 4.15) | 2.12 (0.92, 4.87) | 0.158 | Reference | 1.39 (0.61, 3.14) | 1.29 (0.58, 2.88) | 0.841 | 0.264 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.58 (0.68, 3.66) | 1.61 (0.69, 3.77) | 0.448 | Reference | 1.38 (0.61, 3.13) | 1.29 (0.57, 2.88) | 0.852 | 0.436 |

| ICAS | |||||||||

| N (%) | 25 (16) | 28 (24) | 37 (36) | 10 (14) | 40 (34) | 64 (47) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.67 (0.91, 3.04) | 3.01 (1.67, 5.40)** | < 0.001 | Reference | 3.28 (1.52, 7.07)** | 5.61 (2.66, 11.83)** | < 0.001 | 0.429 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.57 (0.85, 2.88) | 2.66 (1.45, 4.85)** | 0.003 | Reference | 3.29 (1.51, 7.15)** | 5.32 (2.50, 11.32)** | < 0.001 | 0.724 |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01.

P-values for trend were calculated using the logistic regression applying the median value of CAC score for each group.

Interaction by age-strata was checked using logistic regression assigning the age-group specific median CAC score for each CAC-group where SCVDs components were individually treated as an outcome variable.

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity.

Definitions: Age, assessed at the examination for risk factor and CAC (2010–2014); lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

Table 5. Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of prevalent subclinical cerebrovascular diseases according to coronary artery calcification category stratified by hypertension (absent and present).

| Hypertension absent (n = 314) |

Hypertension present (n = 395) |

P for interaction‡ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC category (CAC scores) |

P for trend§ | CAC category (CAC scores) |

P for trend§ | ||||||

| Moderate to severe | Moderate to severe | ||||||||

| No (0) | Mild (1–100) | (> 100) | No (0) | Mild (1–100) | (> 100) | ||||

| n = 133 | n = 107 | n = 74 | n = 100 | n = 129 | n = 166 | ||||

| Lacunar infarction | |||||||||

| N (%) | 6 (5) | 19 (18) | 14 (19) | 16 (16) | 30 (23) | 56 (34) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 4.57 (1.76, 11.90)** | 4.94 (1.81, 13.49)** | 0.031 | Reference | 1.59 (0.81, 3.12) | 2.67 (1.43, 4.99)** | 0.002 | 0.531 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 3.55 (1.34, 9.43)* | 3.40 (1.21, 9.53)* | 0.192 | Reference | 1.39 (0.70, 2.76) | 2.12 (1.12, 4.03)* | 0.019 | 0.819 |

| DSWMH | |||||||||

| N (%) | 15 (11) | 22 (21) | 17 (23) | 19 (19) | 25 (19) | 52 (31) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 2.04 (1.00, 4.15) | 2.35 (1.09, 5.03)* | 0.099 | Reference | 1.03 (0.53, 1.99) | 1.95 (1.07, 3.54)* | 0.006 | 0.862 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.69 (0.81, 3.51) | 1.80 (0.82, 3.96) | 0.326 | Reference | 1.01 (0.52, 1.97) | 1.89 (1.03, 3.49)* | 0.009 | 0.985 |

| PVH | |||||||||

| N (%) | 17 (13) | 26 (24) | 18 (24) | 24 (24) | 35 (27) | 53 (32) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 2.19 (1.12, 4.30)* | 2.19 (1.05, 4.58)* | 0.162 | Reference | 1.18 (0.65, 2.15) | 1.49 (0.85, 2.61) | 0.169 | 0.542 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.64 (0.81, 3.31) | 1.43 (0.66, 3.10) | 0.721 | Reference | 1.00 (0.54, 1.87) | 1.13 (0.63, 2.04) | 0.605 | 0.894 |

| Microbleeds | |||||||||

| N (%) | 10 (8) | 13 (12) | 9 (12) | 11 (11) | 22 (17) | 28 (17) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 1.70 (0.72, 4.05) | 1.70 (0.66, 4.40) | 0.460 | Reference | 1.66 (0.77, 3.62) | 1.64 (0.78, 3.46) | 0.449 | 0.744 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 1.25 (0.51, 3.07) | 1.10 (0.41, 2.95) | 0.968 | Reference | 1.60 (0.73, 3.50) | 1.53 (0.72, 3.28) | 0.582 | 0.934 |

| ICAS | |||||||||

| N (%) | 13 (10) | 24 (22) | 21 (28) | 22 (22) | 44 (34) | 80 (48) | |||

| Unadjusted model | Reference | 2.67 (1.29, 5.54)** | 3.66 (1.70, 7.85)** | 0.008 | Reference | 1.84 (1.01, 3.33)* | 3.30 (1.88, 5.79)** | < 0.001 | 0.553 |

| Age adjusted model | Reference | 2.41 (1.14, 5.08)* | 3.16 (1.43, 6.95)** | 0.029 | Reference | 1.70 (0.93, 3.11) | 2.89 (1.63, 5.12)** | < 0.001 | 0.736 |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01.

P-values for trend were calculated using the logistic regression applying the median value of CAC score for each CAC category.

Interaction by hypertension-strata was checked using logistic regression assigning the hypertension-group specific median CAC score for each CAC-group where SCVDs components were individually treated as an outcome variable.

Abbreviations: CAC, coronary artery calcification; DSWMH, deep and subcortical white matter hyperintensity; ICAS, intracranial arterial stenosis; PVH, periventricular white matter hyperintensity.

Definitions: Age, assessed at the examination for risk factor and CAC (2010–2014); lacunar infarction, number of lesions ≥ 1; DSWMH, grade ≥ 3; PVH, grade ≥ 2; microbleeds, number of lesions ≥ 1; ICAS, a stenosis of ≥ 1% identified in the basilar artery, plus the following five vessels bilaterally: intracranial segments of the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, intracranial segments of the vertebral artery, and the posterior cerebral artery.

Discussion

The results of this population-based study of Japanese men showed the coexistence of CAC and SCVDs, as well as graded relationships between them, independent of age. Even in a model adjusted for risk factors, the association remained similar to the age-adjusted analyses. These results suggest that the predictive value of CAC for SCVDs is incremental and independent of vascular risk factors. To our knowledge, this is the first study in which both small- and large-cerebral-vessel diseases were included as forms of SCVD and the first to explore the graded association with coronary atherosclerosis measured by CAC.

It is speculated that the coexistence of CAC and SCVDs points to a mechanistic explanation for why CAC predicts noncardiac diseases, such as stroke and dementia. However, this coexistence has rarely been shown3, 7, 21). In this study, coexistence of CAC and SCVDs was directly demonstrated in a communitybased sample of healthy men with a broad age range. In addition, hypertension-stratified analyses showed higher odds of prevalent lacunar infarction and ICAS in the highest CAC category even in the no-hypertension group with no evidence of interaction by hypertension status on the association between CAC and SCVDs. These findings have important scientific and clinical implications given the conventional thought that CAC and cerebral small-vessel diseases differ in terms of pathogenesis, atherosclerosis for the former and arteriolosclerosis for the latter2, 4–6, 21–23). While this is a valid thought from the pathological viewpoint, our findings support an epidemiological hypothesis that CAC can work as a marker for both atherosclerosis and, to a lesser extent, arteriolosclerosis at a population level. The results from our secondary aim helped us understand the reason of such predictability of CAC for atherosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis because CAC was broadly related to conventional risk factors, whereas all of the small-vessel diseases were only related to age and hypertension/systolic blood pressure. The presence and degree of CAC may be a promising clinical indicator for pointing out prevalent SCVDs; thus, they may be utilized for early identification and prevention of SCVD-related diseases, such as stroke and dementia, although further studies are clearly needed to justify the clinical use of CAC as a candidate marker.

Association between CAC and SCVDs

Higher CAC scores were associated with subclinical lacunar infarction, which is consistent with other studies6, 7, 21, 22). In contrast, CAC was associated with DSWMH6, 7), but not with PVH. This differential relationship might be due to pathological, functional, and underlying microstructural properties that differ between PVH and DSWMH15). Similarly to Bos et al.7), we observed no association between CAC and microbleeds. To our knowledge, only two studies reported a positive association between CAC and microbleeds6, 21). The participants in those studies were older than those in the present study (age > 65 years). In one of these studies, the AGES-Reykjavik Study conducted in Iceland6), no graded association across the CAC categories was shown by point estimates, although the P-value for the association was highly significant. In another study conducted in Korea21), only a sex-adjusted relationship was reported without reporting the presence or absence of interaction by sex. Thus, their results may be distorted due to residual confounding by sex. In addition, the pathogenesis of microbleeds is likely heterogeneous, including amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive vasculopathy24), differing from other cerebral small-vessel disease components4, 24). This heterogeneous etiology of microbleeds, along with the aforementioned factors, may explain the inconsistencies between studies.

We observed a strong, independent, graded association between CAC and ICAS and a similar pattern of association with conventional risk factors. This was expected as it is consistent with previous studies5, 8). Our observation further supports the use of the CAC score as a predictor of brain diseases, because ICAS is a significant cause of ischemic stroke16) and has been shown to be associated with cognitive impairment/dementia in a community-based study in the USA25).

A Similar Study in Asia

A study with a similar objective to ours was conducted on a Korean population21). The major advantage of our study is that we studied a wider age range (46–83 years), whereas the Korean study included only those aged 65 or older as the investigators believed that small-vessel diseases are rare in younger groups (< 65 years). However, the age-stratified analyses of our study showed that the overall relationship between CAC and SCVDs was similar in younger (< 70 years) and older (≥ 70 years) men. The lack of providing sex-specific results or lack of assessment of interaction by sex in the Korean study as mentioned earlier may limit its interpretation because the relationship may differ between the sexes owing to differences in the risk factors and incidence of CAC26).

Risk Factors for CAC and SCVDs

Our study did not show a statistically significant positive association with some known conventional risk factors such as diabetes with cerebral small-vessel diseases, as well as smoking with CAC and SCVDs. This was an unexpected result in light of the wellknown adversarial effects of those factors on atherosclerosis and vascular diseases8, 27). This lack of statistical significance may be due to the following reasons: (a) the simultaneous inclusion of all the covariates that partially share a common causal pathway in the model may have attenuated the estimated association; (b) a true association may be weaker relative to other risk factors; and (c) residual confounding is possible relative to change or control of past modifiable risk behaviors. It is noteworthy that some other studies also failed to show an independent association of these factors with atherosclerosis28, 29).

Limitations and Strengths

Some limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, given the observational nature of the study, no cause–effect relationship could be established. Second, our study results apply only to men as we did not include women. Third, we used visual grading for white matter hyperintensity, whereas volumetric measurements may be more accurate and sensitive30). Fourth, we may have underestimated the relationship between CAC and SCVDs because older and more risk-factor-clustered participants were excluded from our analyses. The strengths of the study include the community-based random sample of apparently healthy men, which enhanced the generalizability of the findings to the Japanese male population. Other strengths include masked assessment of key components, CAC and SCVDs, from the participants' characteristics to minimize information bias (i.e., so-called “suspicious bias”), as well as the standardized measurements of relevant parameters, including laboratory data, and a moderate sample size.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study showed that higher CAC was associated with some but not all forms of prevalent SCVDs. This finding provides a mechanical explanation of why CAC can predict brain diseases such as dementia and stroke, although CAC and cerebral small-vessel diseases differ in terms of pathogenesis. The differential association of CAC with various components of SCVDs warrants further study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the investigators, staff, and study participants of Shiga Epidemiological Study of Subclinical Atherosclerosis (SESSA) for their outstanding dedication and commitment. The names of the members of the SESSA research group are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Sources of Funding/Grant Support

SESSA as supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 13307016, (A) 17209023, (A) 21249043, (A) 23249036, (A) 25253046, (A) 15H02528, (A) 18H04074, (B) 26293140, (B) 24790616, (B) 21790579, and (B) 18H03048 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and by Grant R01HL068200 from GlaxoSmithKline GB. This study was initiated and analyzed by the authors. The funding sources listed above had no role in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Members of the SESSA Research Group:

Co-chairpersons: Hirotsugu Ueshima and Katsuyuki Miura (Department of Public Health, Center for Epidemiologic Research in Asia, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga).

Research members: Minoru Horie, Yasutaka Nakano, Takashi Yamamoto (Department of Cardiovascular and Respiratory Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Emiko Ogawa (Health Administration Center, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Hiroshi Maegawa, Itsuko Miyazawa (Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Kiyoshi Murata (Department of Radiology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Kenichi Mitsunami (Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Kazuhiko Nozaki (Department of Neurosurgery, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Akihiko Shiino (Molecular Neuroscience Research Center, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Isao Araki (Kusatsu Public Health Center, Kusatsu, Shiga), Teruhiko Tsuru (Department of Urology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Ikuo Toyama (Unit for Neuropathology and Diagnostics, Molecular Neuroscience Research Center, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Hisakazu Ogita, Souichi Kurita (Division of Medical Biochemistry, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Toshinaga Maeda (Central Research Laboratory, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Naomi Miyamatsu (Department of Clinical Nursing Science Lecture, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Toru Kita (Kobe Home Care Institute, Kobe, Hyogo), Takeshi Kimura (Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto), Yoshihiko Nishio (Department of Diabetes, Metabolism, and Endocrinology, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima), Yasuyuki Nakamura (Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Faculty of Agriculture, Ryukoku University, Otsu, Shiga), Tomonori Okamura (Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, School of Medicine, Keio University, Tokyo), Akira Sekikawa, Emma JM Barinas-Mitchell (Department of Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), Daniel Edmundowicz (Department of Medicine, Section of Cardiology, School of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA), Takayoshi Ohkubo (Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Teikyo University School of Medicine, Tokyo), Atsushi Hozawa (Preventive Medicine, Epidemiology Section, Tohoku University, Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Sendai, Miyagi), Nagako Okuda (Department of Health and Nutrition, University of Human Arts and Sciences, Saitama), Aya Higashiyama (Research and Development Initiative Center, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Suita, Osaka), Shinya Nagasawa (Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Kanazawa Medical University, Kanazawa, Ishikawa), Yoshikuni Kita (Faculty of Nursing Science, Tsuruga Nursing University, Tsuruga, Fukui), Yoshitaka Murakami (Division of Medical Statistics, Department of Social Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo), Aya Kadota (Center for Epidemiologic Research in Asia, Department of Public Health, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Akira Fujiyoshi, Naoyuki Takashima, Takashi Kadowaki, Sayaka Kadowaki (Department of Public Health, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Robert D. Abbott, Seiko Ohno, Maryam Zaid (Center for Epidemiologic Research in Asia, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga), Hisatomi Arima (Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka University), Takashi Hisamatsu (Department of Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Shimane University), Naoko Miyagawa, Sayuki Torii, Yoshino Saito, Sentaro Suzuki and Takahiro Ito (Department of Public Health, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Shiga).

References

- 1). Osawa K, Nakanishi R, Budoff M: Coronary artery calcification. Glob Heart, 2016; 11: 287-293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Vliegenthart R, Hollander M, Breteler MM, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC: Stroke is associated with coronary calcification as detected by electron- beam CT: the Rotterdam Coronary Calcification Study. Stroke, 2002; 33: 462-465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Fujiyoshi A, Jacobs DR, Fitzpatrick AL, Alonso A, Duprez DA, Sharrett AR, Seeman T, Blaha MJ, Luchsinger JA, Rapp SR: Coronary Artery Calcium and Risk of Dementia in MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Circ Cardiovasc Imaging, 2017; 10: e005349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Pantoni L: Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol, 2010; 9: 689-701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Oh HG, Chung PW, Rhee EJ: Increased risk for intracranial arterial stenosis in subjects with coronary artery calcification. Stroke, 2015; 46: 151-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Vidal JS, Sigurdsson S, Jonsdottir MK, Eiriksdottir G, Thorgeirsson G, Kjartansson O, Garcia ME, van Buchem MA, Harris TB, Gudnason V, Launer LJ: Coronary artery calcium, brain function and structure: the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Stroke, 2010; 41: 891-897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Bos D, Ikram MA, Elias-Smale SE, Krestin GP, Hofman A, Witteman JC, van der Lugt A, Vernooij MW: Calcification in major vessel beds relates to vascular brain disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2011; 31: 2331-2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). de Weert TT, Cakir H, Rozie S, Cretier S, Meijering E, Dippel DW, van der Lugt A: Intracranial internal carotid artery calcifications: association with vascular risk factors and ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Am J Neuroradiol, 2009; 30: 177-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Shitara S, Fujiyoshi A, Hisamatsu T, Torii S, Suzuki S, Ito T, Arima H, Shiino A, Nozaki K, Miura K, Ueshima H: Intracranial Artery Stenosis and Its Association With Conventional Risk Factors in a General Population of Japanese Men. Stroke, 2019; 50: 2967-2969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Nomura Y, Faegle R, Hori D, Al-Qamari A, Nemeth AJ, Gottesman R, Yenokyan G, Brown C, Hogue CW: Cerebral small vessel, but not large vessel disease, is associated with impaired cerebral autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass: a retrospective cohort study. Anesth Analg, 2018; 127: 1314-1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Ueshima H, Kadowaki T, Hisamatsu T, Fujiyoshi A, Miura K, Ohkubo T, Sekikawa A, Kadota A, Kadowaki S, Nakamura Y, Miyagawa N, Okamura T, Kita Y, Takashima N, Kashiwagi A, Maegawa H, Horie M, Yamamoto T, Kimura T, Kita T: Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 is related to risk of subclinical atherosclerosis but is not supported by Mendelian randomization analysis in a general Japanese population. Atherosclerosis, 2016; 246: 141-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R: Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1990; 15: 827-832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Shinohara Y, Tohgi H, Hirai S, Terashi A, Fukuuchi Y, Yamaguchi T, Okudera T: Effect of the Ca antagonist nilvadipine on stroke occurrence or recurrence and extension of asymptomatic cerebral infarction in hypertensive patients with or without history of stroke (PICA Study). Cerebrovasc Dis, 2007; 24: 202-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). A new guideline making committee of a brain dock Brain MRI examination In: Japanese Society for Detection of Asymptomatic Brain Disease, ed. Braindock Guideline 2014 [in Japanese]. 4th ed. Tokyo, Japan: Kyobunsha; 2014: 38-47 [Google Scholar]

- 15). Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA: MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. Am J Roentgenol, 1987; 149: 351-356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, Smith HA, Chimowitz MI: A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. Am J Neuroradiol, 2000; 21: 643-646 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Nakamura M, Sato S, Shimamoto T: Improvement in Japanese clinical laboratory measurements of total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol by the US Cholesterol Reference Method Laboratory Network. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2003; 10: 145-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem, 1972; 18: 499-502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Kashiwagi A, Kasuga M, Araki E, Oka Y, Hanafusa T, Ito H, Tominaga M, Oikawa S, Noda M, Kawamura T, Sanke T, Namba M, Hashiramoto M, Sasahara T, Nishio Y, Kuwa K, Ueki K, Takei I, Umemoto M, Murakami M, Yamakado M, Yatomi Y, Ohashi H, International clinical harmonization of glycated hemoglobin in Japan : from Japan Diabetes Society to National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program values. J Diabetes Investig, 2012; 3: 39-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Kohara K, Okada Y, Ochi M, Ohara M, Nagai T, Tabara Y, Igase M: Muscle mass decline, arterial stiffness, white matter hyperintensity, and cognitive impairment: Japan Shimanami Health Promoting Program study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2017; 8: 557-566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Kim BJ, Lee SH, Kim CK, Ryu WS, Kwon HM, Choi SY, Yoon BW: Advanced coronary artery calcification and cerebral small vessel diseases in the healthy elderly. Circ J, 2011; 75: 451-456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Romero JR, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Benjamin EJ, Polak JF, Vasan RS, Au R, DeCarli C, Wolf PA: Carotid artery atherosclerosis, MRI indices of brain ischemia, aging, and cognitive impairment: the Framingham study. Stroke, 2009; 40: 1590-1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Ooneda G: Pathology of stroke. Jpn Circ J, 1986; 50: 1224-1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Martinez-Ramirez S, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A: Cerebral microbleeds: overview and implications in cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2014; 6: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Suri MFK, Zhou J, Qiao Y, Chu H, Qureshi AI, Mosley T, Gottesman RF, Wruck L, Sharrett AR, Alonso A, Wasserman BA: Cognitive impairment and intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in general population. Neurology, 2018; 90:e1240-e1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SA: Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis, 2015; 241: 211-218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Shea S, Lima JA, Cushman M, Bild DE, Burke GL: Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation, 2007; 115: 2722-2730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Matsui R, Nakagawa T, Takayoshi H, Onoda K, Oguro H, Nagai A, Yamaguchi S: A prospective study of asymptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in neurologically normal volunteers in a Japanese cohort. Front Neurol, 2016; 7: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Suri MFK, Qiao Y, Ma X, Guallar E, Zhou J, Zhang Y, Liu L, Chu H, Qureshi AI, Alonso A, Folsom AR, Wasserman BA: Prevalence of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis using high-resolution magnetic resonance angiography in the general population: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Stroke, 2016; 47: 1187-1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Ogama N, Saji N, Niida S, Toba K, Sakurai T: Validation of a simple and reliable visual rating scale of white matter hyperintensity comparable with computer-based volumetric analysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2015; 15: 83-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]