Abstract

Multiple methodological approaches have been used to explore adolescent alcohol use and related sexual behaviors, ranging from surveys to assessments of alcohol outlet density. Although surveys can capture the extent of alcohol use, they do not allow for a contextualized understanding of young people’s voiced experiences with alcohol, including sociocultural, gendered and environmental pressures to consume, and related engagement in sex. The mapping of alcohol outlets provides physical density information, but infrequently from youths’ perspectives. Traditional qualitative methods like in-depth interviews and focus group discussions do allow for a more nuanced understanding of adolescents’ experiences, but they can be limited by the use of semi-structured guides that may negatively impact the fluidity of discussion. We seek to contribute to the methodological approaches utilized with adolescents by demonstrating how contextualized data were captured from Tanzanian adolescents’ experiences of alcohol and sex, which are sensitive topics in many African countries. We collected data in secondary schools and youth centers across four sites in Dar es Salaam, the largest and most diverse city in Tanzania.

As a complement to in-depth interviews, archival reviews, and a systematic mapping of alcohol availability, participatory methodologies such as photovoice, story writing, and drawing allowed Tanzanian youth to offer more honest, descriptions of lived experiences with their physical and social environment in relation to alcohol use and related sexual behavior patterns. Through participatory methods, study participants were able to discuss behaviors that are viewed as social transgressions, sensitive topics like violence in relation to sex, and views around their own self-agency. The use of a methodological toolkit including participatory methodologies enabled youth to trust the researchers and share sensitive information in a relatively short period of time, overcoming some of the challenges of traditional qualitative methods.

Keywords: Qualitative, Participatory, Photovoice, Adolescent, Alcohol, Africa

Background

Conducting research with adolescents on sensitive topics, such as alcohol use and risky sexual behaviors, presents multiple methodological challenges. A key challenge is the ability to capture valid descriptions of self-reported behaviors concerning their own and their peers’ drinking behaviors, and subsequent engagement in or condom-free sex (Mensch, Hewett, & Erulkar, 2003). In many societies, youth may not honestly describe alcohol use out of fear of social sanctioning from family or community members. Similarly, there may be negative repercussions for youth who transgress existing sociocultural norms concerning the age considered appropriate for sexual relations (DiClemente, Swartzendruber, & Brown, 2013). These repercussions may include, for example, physical beatings, early marriage, or expulsion from the home, depending on local beliefs and circumstances. Although young people in Tanzania may have sexual relations before marriage, many keep their behaviors hidden unless from select tribal or ethnic groups that condone premarital sex. Many of the methodologies currently used to capture such behaviors among young people, such as surveys that aim for generalizability, do not allow for a deeper understanding of the “why” and “how” of youth risk behaviors (Fenton, Johnson, McManus, & Erens, 2001). Traditional qualitative methodologies, such as in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, greatly enhance the ability to explore youth behaviors in relation to alcohol use and sex, but may be limited because of their reliance on an interactive discussion using a semi-structured guide. In order to more effectively capture youth’s perceptions, desires, experiences and recommendations in relation to their own and their peers’ vulnerability to risky behaviors, it is important to utilize more creative approaches that are rigorous in design, capture a richness of data, and empower youth through the research process.

Currently there are over 1.8 billion young people aged 10–24, 88% of which live in low-income countries (Das Gupta et al., 2014). Although adolescence is recognized globally as a period of increased vulnerability to risky behaviors (Blum, Astone, Decker, & Chandra-Mouli, 2014; Gardner & Steinberg, 2005), research on adolescents’ alcohol use and related unsafe sexual behaviors in sub-Saharan African is minimal (Page & Hall, 2009; Weiser et al., 2006). This includes inadequate documentation of the ways in which youth are accessing alcohol in rapidly growing urban environments. Although a small body of evidence on youth uptake and use of alcohol exists from a few countries (e.g., Kenya, Zambia, South Africa; Morojele & Ramsoomar, 2016; Mugisha, Arinaitwe-Mugisha, & Hagembe, 2003; Onya, Tessera, Myers, & Flisher, 2012; Swahn, Ali, Palmier, Sikazwe, & Mayeya, 2011a; Swahn et al., 2011b; Swahn & Donovan, 2004), there remains insufficient evidence as to where and when adolescents are initiating alcohol use, gendered patterns of alcohol consumption, and related implications for their health and wellbeing. Tanzania, similar to many sub-Saharan African countries, has a culture of alcohol use that includes “home brew” (alcohol made for ceremonial purposes or income-generation; Haworth & Simpson, 2004; McCoy, Ralph, Wilson, & Padian, 2013), and a range of commercial alcohols. There is a diversity of homebrews produced by different ethnic groups across the country, of which some introduce alcohol to children at very young ages during ceremonies (e.g., weddings; Sommer, Likindikoki, & Kaaya, 2013a), and others sanction adolescent alcohol use for social or religious reasons.

Little is known about youths’ patterns of alcohol initiation and use in Tanzania, including the visual and social presence of alcohol in their daily lives, and the ways in which alcohol may be influencing subsequent sexual behaviors. Recent evidence suggests the presence of gendered patterns of use, with Tanzanian boys and men experiencing greater pressure to drink and consuming higher amounts than girls and women, and related implications for behaviors related to violence and unsafe sex (Sommer et al., 2013a). One study estimated that about 17.2% of sampled individuals aged 15–59 were using alcohol as of 2006, and 5.7% at a hazardous level (Mbatia, Jenkins, Singleton, & White, 2009). Although minimal data exists from Tanzania, in studies of youth conducted in other contexts, alcohol use has been found to increase youth vulnerability to unsafe sexual behaviors, such as sexual violence, unwanted pregnancy, and HIV infection (Eaton et al., 2012; Kalichman, Simbayi, Kaufman, Cain, & Jooste, 2007; Stueve & O’Donnell, 2005). However, soliciting honest information from youth about their own (or their peers’) use of alcohol and related engagement in sexual behaviors poses challenges. In Tanzania, the legal age of alcohol use is 18, and premarital sexual activity is sanctioned by much of society (Lyimo, Masinde, & Chege, 2017). Creative, rigorous and empowering participatory methodologies are one possible approach to gathering valid data from adolescents, embedded within a larger methodological toolkit (Sommer, 2009).

In this article, we discuss the application of one such approach, a methodological toolkit that was designed to gain an in-depth understanding of urban Tanzanian adolescents’ experiences and perspectives on alcohol use within their local environments, their gendered patterns of use, and related sexual behaviors. Our overall aim was to begin filling the significant gap in the evidence on adolescent alcohol use and unsafe sexual behaviors in sub-Saharan Africa, and to also utilize new participatory approaches aimed at capturing sensitive information from them. This included the use of anonymous story writing, mapping, and photo-voice with adolescents, along with the application of more traditional qualitative methodologies, such as key informant and in-depth interviews. Given the sensitivity of the topics, it was critical to utilize participatory methodologies that encourage honesty, create a safe space for youth to feel heard, and demonstrate respect for adolescents’ own abilities to tell their stories and identify solutions to the challenges they face (Catalano et al., 2012). The use of the participatory and more traditional qualitative approaches was enhanced by the inclusion of a systematic quantitative mapping of the alcohol environment around the schools and youth centers by the adult research team. Together, the methods provided a rich triangulation of adolescents’ lives in relation to the influences shaping their alcohol use and subsequent sexual behaviors. Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) Internal Review Board (IRB), the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) IRB, the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) and the Tanzania Commission on Science and Technology (COSTECH).

Context

Tanzania is a rapidly urbanizing country, with one-third of the population located in urban areas (UNICEF, 2016). The population is almost 52 million, two-thirds of whom are under age 25 (Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics, 2012, 2017). The prevalence of HIV is 4.7%, with the number of people living with HIV and AIDS estimated to be almost 4 million (UNAIDS, 2016). Young women (15–24 years old) are particularly vulnerable, with an HIV prevalence of 2.3%. The country ranks 23rd globally in maternal mortality, with many of these deaths happening among adolescent girls (Patton et al., 2009). Consumption of alcohol, either by adolescent girls or their partners, increases their vulnerability to HIV and unwanted pregnancy, along with experiencing sexual violence (Blum & Mmari, 2005; Maughan-Brown, Evans, & George, 2016).

Dar es Salaam is a densely populated urban environment, with local districts varying in socioeconomic status, tribal clustering, and access to health, education and social services (Muzzini & Lindeboom, 2008). Many neighborhoods have tightly packed small houses, and formal or informal bars and shops with narrow alleyways. Street lighting is minimal at night, contributing to an environment of diminished safety. The research team chose Dar es Salaam as it is the largest and most diverse city in Tanzania. It is expected that rural areas would have different youth drinking patterns.

Tanzania is experiencing a changing political environment in relation to alcohol. At the beginning of data collection in the four sites in Dar es Salaam, the government was bringing pressure to bear on the lack of taxes being paid by sellers of various goods (including alcohol), along with new mandates on bar opening hours (after 4pm and closing by 11pm). This created challenges for the research team, who were all Tanzanians from Dar es Salaam, but were perceived to be outsiders in the study districts, with the potential for suspicion if too many questions were asked about alcohol selling and usage behaviors. The team spent time during the training period discussing how to conduct the data collection to maximize its quality and minimize hostility from the community and the government.

In each of the four sites, the research team identified a secondary school and youth center for conducting the data collection with students and out of school youth. These institutions were also the focal points for the systematic mapping that was conducted of alcohol availability.

Developing a New Methodological Toolkit

The two-year qualitative research study combined multiple methods, including participatory methodologies, to advance knowledge on alcohol initiation and use among youth (aged 15–19) in urban Tanzania, and their relationship to risky sexual behavior. The study also aimed to advance knowledge on the role of alcohol accessibility, availability, and acceptability in shaping youth alcohol use in urban Tanzania, and on potential structural interventions for preventing and reducing youth alcohol use and risky sexual behavior. The methodological toolkit is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Range of Methods Utilized

| Method | Description | Rationale/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Formative Key Informant Interviews | In-depth interviews with stakeholders engaged in policy and practice such as current leaders in diverse government ministries (e.g. health, education) and non-governmental organizations working in HIV prevention and adolescent health. | To gather insights into past and present patterns of adolescent alcohol use and unsafe sexual behaviors in urban Tanzania |

| Archival Review | Existing documents such as legislative policies and reports on the availability and accessibility of alcohol for adolescents, the new National Alcohol Policy. | The new National Alcohol Policy was under development at the time of drafting the research grant application |

| Mapping of alcohol availability and advertising | Physical mapping in systematic bounded circles around each of the four secondary schools and four youth centers (designated sites within the three districts in Dar es Salaam). | The research assistants worked in teams of two to document the physical environment around youth in all four sites. This included availability and ease of accessibility along with marketing/advertisements. |

| Participatory Methodologies with adolescent girls and boys in and out of school | A range of methodologies were utilized to capture young people’s individual and group perceptions and experiences in relation to alcohol and related unsafe sex in their lives. | More creative methods were deemed essential to capturing data on more sensitive topics. Details on specific methods appear in Table 2. |

| In-Depth Interviews with adolescents | In-depth semi-structured interviews with a sample of adolescent girls and boys in and out of school in each of the four sites. | To create an opportunity for more in-depth exploration of youth’s experiences than group activities permitted |

| In-Depth Interviews with adults | In-depth semi-structured interviews with a sample of adults interacting in youths’ lives in each of the four sites. | For example, parents, teachers, policemen, shopkeepers, alcohol brewers, health care workers, religious leaders; independent of adolescent participants |

| Concluding Key Informant Interviews | In-depth interviews with stakeholders from relevant sectors (e.g. legal institutions, health, non-governmental organizations, alcohol industry) | To inform the development of new (or adapt existing) structural interventions aimed at reducing adolescent alcohol initiation and use and related unsafe sex |

As noted in Table 1, the toolkit incorporated the use of traditional qualitative methods including formative (n=8) and concluding (those capturing perspectives and insights into the preliminary findings) (n=8) key informant interviews with stakeholders, and in-depth interviews with adolescents (n=24) and adults (n=24). Such methods are recognized for their ability to rigorously investigate diverse perspectives and experiences (Ritche, Lewis, McNaughton Nicholls, & Ormston, 2013), and played an essential role in the triangulation of findings. However, such approaches were perceived to be inadequate for capturing youths’ honest experiences in relation to alcohol and sex related behaviors, and insufficient for enabling youth to feel empowered in telling stories of their own lives, given the inherent power dynamic between the (older, more educated) interviewer and the (younger, less educated) interviewee. This led to the decision to adapt a range of participatory methodologies for inclusion in the toolkit that would aim to overcome these challenges.

Participatory Methodologies With Youth

The development and application of participatory methodologies with youth, the main focus of this paper, was critical for capturing their lived experiences with alcohol and alcohol-related sexual interactions, along with their recommendations for how to address youth alcohol use and related unsafe sex. Participatory methodologies emphasize an equalizing and dynamic exchange between researchers and participants (Minkler, Blackwell, Thompson, & Tamir, 2003), and because it empowers youth, enables them to feel like researchers of their own lives (Mitchell & Sommer, 2016). Such approaches engage participants in the research process, in a qualitatively different way, which is especially important in gaining entry for the discussion of hard-to-discuss issues. Ideally, such approaches enable youth to interrogate their own experiences in a way that they might not otherwise have done through the use of traditional qualitative methods. This can create or instigate a consciousness-raising effect, along the lines of Paulo Freire’s (1972) conscientização and the notion of praxis, or combining theory and practice. In addition, participatory methodologies that include the creation of writing (stories) or images (photovoice) are:

…modes of inquiry that can engage participants…eliciting evidence about their own health and well-being, and at the same time are modes of representation and modes of production in the co-creation of knowledge, and modes of dissemination in relation to knowledge translation and mobilization (Mitchell & Sommer, 2016, p. 521).

The use of participatory methodologies thus offers insights into how Tanzanian youth themselves perceive their environment, both physically and socially, in relation to alcohol availability and usage, and alcohol-related sexual behaviors. Such methods serve to triangulate the other forms of qualitative research methodologies included in the larger study design. If only traditional qualitative methodologies had been used, or only classroom-based activities, youth would not have had the opportunity to be active investigators of their environments, which was enabled by the inclusion of photovoice. The co-creation of drawings and photos, while important forms of empirical evidence, can also be shared at the conclusion of a study with local policy makers and practitioners as effective ways to convey the views of their country’s youth.

The process of developing and adapting the participatory methodologies was based on an extensive review of the literature on approaches for soliciting information on sensitive topics (including alcohol and sex) from youth in various contexts (Ansell, Robson, Hajdu, & van Blerk, 2012; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Powers & Tiffany, 2006), and the prior use of similar participatory methodologies by the principal investigator and co-investigators in the Tanzania context over the last decade (Sommer, 2009; Sommer et al., 2013a; Sommer, Likindikoki, & Kaaya, 2013b, 2015). Although the prior Tanzania studies did not explicitly focus on alcohol and sex, they engaged similar aged youth in written and verbal activities that explored individually and within groups their experiences of pubertal body changes, family and peer pressures, gender dynamics, and violence, along with their recommendations for addressing such challenges.

The range of methodologies developed for, or adapted to, the Tanzania context are outlined in Table 2, with a description of data sets in Table 3. We have separated out activities that were conducted weekly with each group of youth in and out of school (the research assistants met with each group a total of four times, 1.5 hours per session), with further details on the sample and data collection described below. Weekly sessions with each group (over a period of four weeks per site) were essential to building trust between youth and the research team to encourage the sharing of sensitive information, and for enabling youth to grasp the concept of structural factors in exploring how their environments might contribute to alcohol use and unsafe sex, and for generating creative ideas about how their environments might be modified.

Table 2.

Participatory Methodologies Utilized

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Week 1: | |

| • Introduction | |

| • Brainstorming: Alcohol use in Tanzania society and types of alcohol | • In large group, youth listed out first the reasons for alcohol use in the society, and then made lists of the range of alcohol types |

| • Good & Bad things about alcohol | • In large group, youth filled out a table with “good” and “bad” listed at the top, identifying what they felt belonged in each category |

| • Mapping alcohol in community | • Youth were divided into small groups of 4–6, given large white paper and pens, and asked to draw (and label) the places in their community where alcohol was available (sold, used, given out). The research team then spent time discussing each map with the groups. |

| • Story writing: Pressure to use or usage of alcohol | • Youth were separated so sitting a desk apart from each other and given paper and pen to write an anonymous story about a time when they felt pressured to use (or used) alcohol |

| • Anonymous question writing on alcohol and other drugs, sex and other growing up question | • Youth continued to sit separately and were given paper and pen to list out anonymously their top 3–4 questions about alcohol, sex and growing up |

| Week 2: | |

| • Brainstorming: Reasons people have sex | • In large group, youth listed out reasons people in the society and their communities have sex |

| • Comfortable or Uncomfortable talking about sex | • In large group, youth filled out a two-column table with the reasons people are comfortable (or not) talking about sex in their communities |

| • Brainstorming: Learning about sex | • In large group, youth listed out how youth learn about sex |

| • Gendered sexual initiation | • First in small group breakouts (with pieces of paper and pen), and then in large group, youth filled in a table with girl/boy columns about the age at which girls vs. boys have sex, and the reasons for beginning |

| • Condoms or No Condoms | • First in small group breakouts (with pieces of paper and pen), and then in large group, youth filled in table with use/don’t use columns on the reasons why youth do or do not use condoms |

| • Mapping condoms in community | • Youth were divided into small groups of 4–6, given large white paper and pens, and asked to draw (and label) the places in their community were condoms are provided (for free) or sold. The research team then spent time discussing each map with the groups. |

| • Story writing: Pressure to have sex (or about having sex) | • Youth were separated so sitting a desk apart from each other and given paper and pen to write an anonymous story with various possible prompts, including to write about the first time they had sex, a time when they felt pressured to have sex or had sex (by choice), a time someone they knew felt pressured to have sex, or a time when they had sex (by choice) or felt pressured to have after drinking alcohol |

| • Answering anonymous questions | • Research team answered 1/3 of the questions submitted during the previous week’s session |

| Week 3: | |

| • Brainstorming: Pictures/images youth have seen of people drinking alcohol |

• In large group, youth listed out pictures/images/advertisements they have seen in the environment or on media/social media about alcohol |

| • Encourages or Discourages drinking | • In large group, youth filled out a table with encourages/discourages columns about what influences alcohol use among youth |

| • Gendered drinking patterns | • First in small group breakouts (with pieces of paper and pen), and then in large group, youth filled in a table with girl/boy columns about the drinking behaviors of and pressures on girls vs. boys in the society |

| • Brainstorming and Ranking: Changing the alcohol environment | • First the youth explored in a large group (listing) their understanding of what it means “to change the alcohol environment,” and why changing the environment might reduce youth alcohol use. Second, the youth broke into groups (with pieces of paper and pen) and listed and ranked the ways to change the environment that they felt would be most effective in reducing youth alcohol use |

| • Gendered interactions of alcohol and sexual behaviors among youth | • First in small group breakouts (with pieces of paper and pen), and then in large group, youth filled in a table with girl/boy columns about the places where girls vs. boys have sex after drinking |

| • Answering anonymous questions | • Research team answered another 1/3 of the questions submitted during the first week’s session |

| Week 4: | |

| • Brainstorming: Reasons it may be difficult for youth to use condom after drinking alcohol | • In large group, youth listed out reasons it can be difficult for youth to use condoms when they have sex after drinking alcohol |

| • Brainstorming: Changing the physical and social environment to reduce risky sexual behaviors | • In large group, youth first discussed and listed out why providing condoms in bars might (or might not) reduce unsafe sex, and second, youth discussed and listed out how friends might (or might not) protect each other from having unsafe sex after drinking |

| • One billion Tanzanian shillings activity to address youth alcohol use and unsafe sex | • In small group breakouts (with pieces of paper and pen), youth listed out what they would do if given a huge sum of Tanzanian money to change the environment in such a way as to increase youth’s safer sex after drinking alcohol. The groups reported out to the large group, and discussed common answers, ranking those they felt were most effective. |

| • Answering anonymous questions | • Research team answered the final 1/3 of the questions submitted during the first week’s session; youth were able to ask any additional questions that arose for them. |

Table 3.

Participatory Data Setsa

| Transcripts: | Weeks 1–4; total n=64 (4 groups/site, 4 sessions each) Included tables, lists, and notes from discussions |

| Stories (written): | Week 1: One page; n=177; experiences of pressure to drink Week 2: One page; n=177; experiences of pressure to have sex |

| Maps (drawn): | Week 1: Alcohol availability (n=48 maps; 3 per each of 4 groups) Week 2: Condom availability (n=48 maps; 3 per each of 4 groups) |

| Questions: | Week 1; n=16 lists of questions (one per group; 4 groups total) |

Photos were taken of the lists generated on the blackboard during each session and used to build out the transcripts created from each group session of brainstorming and discussion.

The Inclusion of Photovoice

All of the above participatory activities were conducted with the entire youth sample (n=177). We selected a sub-sample of in-school youth from each site (n=10/site; drawn from the groups) to participate in a photovoice activity during weeks 2 and 4. Photovoice is a qualitative research method in which participants are given cameras and asked to share or express their points of view, represent their communities, or capture their perceptions of an issue, by photographing images or scenes and describing their meaning (Wang & Burris, 1997). The inclusion of visual methodologies provided participants with an opportunity to bring their environments into the discussion space, along with empowering youth to feel like the researchers of their own lives in their communities (Carlson, Engebretson, & Chamberlain, 2006). In many African societies, Tanzania included, youth are raised to defer to adults and suppress their own views and opinions as a demonstration of respect (Otiso, 2013). This may hinder their expressions of their own perceptions and experiences during individual interviews, which the photovoice (and other participatory methods) were designed to overcome.

We used a smaller sample primarily because of the limited budget available for purchasing disposable cameras and paying for photo development, but also because of safety issues that might arise from youth taking photos of alcohol spaces, and the need for smaller groups that could receive focused training on the activity. Although there has been a shift in the photovoice community to using digital cameras (Foster-Fishman, Mortensen, Berkowitz, Nowell, & Lichty, 2013; Latz, 2017), we chose to use disposable cameras to reduce the likelihood of youth being robbed or harassed. For the photovoice activity, the team conducted two sessions with each group, with a week in-between to take photos in their communities (see Table 4 describing the photovoice activities and Table 5 for a description of the data set).

Table 4.

Photovoice Activities

| Methods | Description |

|---|---|

| Session 1: | |

| • Conducted week 3 • Meanings within images |

• Research team shared images to explore various meanings within image. |

| • Brainstorming on topic | • Brief brainstorming (refresher from group meetings) about where youth are drinking alcohol and where youth are having sex after drinking |

| • Teaching about camera use • Safety and ethics training |

• Youth taught how to use disposable camera and allowed to practice using one • Youth taught how to be safe while using cameras, and the ethics of not taking actual individual’s photos (unless they had permission) |

| • Group assignment | |

| • Youth divided into small groups and given assignment to take photos of things in the environment that pressure youth to drink alcohol, and things in the environment that make it difficult for youth who are drinking alcohol to use condoms if they decide to have sex | |

| One week with camera | Study coordinator picked up cameras and dropped at shop for development |

|

Session 2: • Conducted week 4 |

• Review of youth’s experiences taking the photos, and what they did/didn’t enjoy |

| • Sharing and discussing of photos | • Groups describe in writing and verbally to the whole group each of their favorite 2–3 photos and why they picked them to discuss, explaining how the pictures respond to the assignment and what can be learned from them, including solutions on how to address youth alcohol use and/or risky sex after drinking. |

Table 5.

Photovoice Data Sets

| Transcripts | Week 1 (n=4); discussion points Week 2 (n=4); discussion points; youth ranking of photos, articulations of why photos selected, and youth solutions around how to change environment |

| Photos: | n=48 photos (3 photos selected per group; 4 groups; 12 per site; 4 sites) |

A secondary aim of using participatory methods was to build the capacity of the research team members, primarily recent graduates from medical, public health or social science programs (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2011). The senior research team sought to encourage the research assistants to feel empowered from leading the activities with the youth, and from their own engagement in the physical mapping activity of alcohol in the sites (see Table 1). Both roles required the development of new skill sets and the implementation of the research assistants’ own knowledge as young adult members of the society in which the youth were growing up, but separated by their generational differences.

Adapting and developing the methodology for the Tanzania context

The selected methodologies innovated on the previous approaches utilized in a few ways. One, the topical content was much more sensitive than prior topics explored, and thus the approaches needed to be adapted for ways to capture valid content in a rigorous and culturally appropriate way. For this, we drew on the existing literature around incorporating mapping and story writing into data collection (Bohn & Berntsen, 2008; Fargas-Malet, McSheery, Larkin, & Robinson, 2010; Palacios et al., 2015; Wright, Wahoush, Ballantyne, Gabel, & Jack, 2016). Two, noting safety concerns around using devices in the sites, the mapping of alcohol sales and advertisements was adapted to a non-technological approach. A formative research period included field-testing the instruments with youth (n=20) and adults (n=10), including gathering inputs about modifying the participatory activity tools. This was essential to assure that youth were comfortable engaging in the activities, able to respond to the different modes of expressing themselves, and willing to share sensitive information through the use of such approaches. The final tools were translated into Swahili and back-translated into English.

Training of research team

The four research assistants included two young men and two young women between the ages of 25 – 32 from Tanzania, who were trained by the investigative team, including extensive practice with the tools. The training was essential for the participatory methodologies in particular given that the pedagogy of many Tanzanian schools includes very limited use of story writing or drawing, limited opportunities for asking questions openly about body changes, and does not include the concept of structural (social, economic, political influences that structure the risk produced or experienced) factors and approaches (those that address such factors, in contrast to, for example, individual level approaches). The participants were expected not to have had prior experience using a disposable camera. Hence the research assistants needed to feel confident in their abilities to elicit such information from the youth, and to train youth on the use of cameras.

Sample recruitment

The team selected key informants through purposive sampling with the aim of capturing a diversity of perspectives on alcohol use and availability in Tanzania, adolescent behaviors in relation to alcohol and sex, regulatory approaches to reducing alcohol use, and the enabling environment for increasing or preventing alcohol and condom use among youth. For the participatory methodologies, the team recruited youth in collaboration with administrations of the secondary schools and youth centers, with purposive sampling utilized to identify diverse youth (lower versus higher economic status, differing academic abilities, differing tribal backgrounds). The youth were aged 15–19, with a total of 177 youth included in the study, divided into 16 groups across four sites. On average there were 10–12 youth per group of in-school or out-of-school youth.

Data collection

The data collection occurred over a three-month period. A schedule enabled the four research assistants to work in alternate pairs as needed. Sometimes the two men and two women worked together, such as with the single sex youth groups, and sometimes in male-female pairs, such as the photovoice activities which were conducted in coed groups. The team also worked in male-female pairs for conducting the systematic mapping, as this was deemed most appropriate for safety reasons.

All interviews were conducted in a confidential space. The research assistants conducted the interviews individually with the participants, always pairing youth with a same-sex interviewer, while for the key informant interviews (KIIs), same-sex pairings were only done when considered important for a participant’s sense of ease. The research assistants digitally recorded the interviews only if the participants granted permission (otherwise the team took handwritten notes). The team conducted the participatory activities with youth in a private room that was out of earshot of others. Each week the team met with the study coordinator, with one or more members of the investigative team present to discuss the week’s activities, modify approaches as needed, and to address challenges.

Thematic data analysis

The final data included interview transcripts, maps drawn and labeled by the youth, written stories, lists created by groups of youth, group discussion transcripts, systematic mapping information of alcohol in the sites, and photos with written summaries (see Tables 3 and 5). The Tanzanian research team coded and analyzed the data with oversight from the larger investigative team. This included NVivo (qualitative data analysis software) coding of the interview transcripts, and matrices developed for analysis of the participatory activities. We conducted thematic analysis on the transcripts from the participatory activities and the notes from the ethnographic observations.

Types of thematic findings that emerged ranged from the density of alcohol in environments around youth (systematic mapping and drawings), the lack of condom accessibility in their environments (brainstorming activities), and rushed nature of sexual encounters (stories and brainstorming), the gendered dynamics of alcohol use (stories), and (from the photos) the places where youth are purchasing or consuming alcohol. The ability to triangulate the findings through the range of methodologies was critical to gathering an in-depth picture of alcohol and sex in youth’s lives.

Discussion

This article describes how a methodological toolkit that includes participatory and other qualitative methodologies can be an effective approach for exploring issues around youth access to and use of alcohol and related sexual behavior in urban Tanzania, and how the process empowers youth to serve as researchers of their own lives with meaningful solutions to the challenges they face. The various participatory methodologies, such as the stories they wrote detailing experiences with alcohol and with sex, revealed a range of findings that might otherwise not have been captured, including occasions of violence in relation to sex, and the interpersonal aspects of relationships that sometimes include discordant feelings about sexual engagement. Such findings go far beyond what might emerge through the use of traditional qualitative methods, and provide critical insights not only into the realities of their individual perspectives but also the social and structural influences shaping their beliefs and behaviors. For example, the anonymity with which the youth could write stories about themselves or others they knew opened up the potential for youth to share experiences of covert behaviors and perceived socially transgressing actions, along with expressions of self-agency, or the personal will an individual has over their actions. Such findings would have been unlikely to emerge from face-to-face interviews or open group discussions, and the use of these approaches offers possibilities for use with youth in other African contexts.

Similarly, the inclusion of opportunities to map the alcohol in their environments from their own and their collective memories, and then to seek out images of local places of youth alcohol purchase and consumption through photovoice, provided an opportunity for the youth to educate the research team. While mapping their communities was found to be a relatively novel activity for the youth, no challenges arose around their ability to convey their intentions when coupled with the questions posed during the discussion. In contrast, while the photovoice activity proved to be very successful, there were challenges related to assuring that the youth were able to take photos safely, with their neighborhoods often being lower-income with the potential for the camera to be stolen, or their desire to take photographs of alcohol sellers having to be balanced with safety concerns. Practices concerning the use of alcohol are complex in Tanzania. While a 1968 law prohibits the use and selling of alcohol to those underage (The United Republic of Tanzania, 1968), the country is made up of over 120 tribes, some of which encourage youth alcohol use for social or religious reasons, while others strongly sanction use. The modeling of heavy male alcohol use in some tribes (Sommer et al., 2013b) provides a powerful incentive for young men to try alcohol. As the participatory methods made clear, homebrew and commercial alcohol are readily available. Capturing youth’s views – in the co-created maps, photos or personal stories – provides powerful visual and written imagery about youth’s everyday realities of alcohol for the research team and ultimately the policy makers with whom the findings are shared.

The application of the methodological toolkit across Dar es Salaam, a multi-cultural urban environment that includes a range of socioeconomic statuses, revealed patterns that suggested the possible influence of high-density alcohol environments as critical shapers of youth’s lives and alcohol use behaviors. In addition, the photo images of where youth were having sex after drinking, combined with their stories and readily offered insights into where girls and boys go to have sex, and the reasons they do or do not use condoms in those locations, revealed aspects of the Dar es Salaam urban physical and social environment (e.g., alleyways where rushed sex would occur). Given the strong societal sanctions around youth drinking and sex, such insights would be unlikely to emerge from face-to-face interviews, nor would the way in which the environment is shaping their behaviors have been as apparent.

In applying a diverse array of approaches, such as the systematic mapping by the research team that documented alcohol availability, in tandem with the drawings by the youth of where alcohol is available to them, the study revealed the structural risk factor that has been found in other countries in relation to high-density alcohol availability (Popova, Giesbrecht, Bekmuradov, & Patra, 2009), and its potential implications for increased adolescent uptake and use (Campbell et al., 2009; Pasch, Komro, Perry, Hearst, & Farbakhsh, 2007; Rowland, Toumbourou, & Livingston, 2015; Rowland et al., 2014). The findings were further triangulated by the photos the teams of youth took of the places where adolescents are gathering to drink, and are being given or sold alcohol. Their subsequent brainstorming of regulatory and environmental approaches for reducing youth alcohol use or delaying alcohol initiation provided an important emic perspective on how to truly impact youth drinking behaviors in this context.

In addition, the drawings that youth made of condom availability and access in their communities, analyzed with their lists of when and why youth do and do not use condoms after drinking, triangulated with the in-depth interviews with adults who intersect in youth’s lives, highlighted enormous barriers that remain in Tanzania (or in Dar es Salaam) to youth condom use, with its related implications for prevention of infection with HIV and unwanted pregnancy (Mnyika, Kvale, & Klepp, 1995; Obasi et al., 2006; Plummer et al., 2012; Sommer et al., 2015). Such insights were greatly enhanced from the stories and images that the youth created, building a research case from within the youth’s lived viewpoints.

Lastly, findings from the combination of methods that were used, such as the insights drawn from their writing about pressures to drink or have sex, and the messaging they reported seeing through photos or hearing from families, peers and the larger society around using alcohol, revealed the current patterns of adolescents’ daily lives growing up in modernizing Tanzania today. The conceptual training on the idea of structural factors revealed sophisticated insights from youth on how their environment could be modified to produce healthier outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the findings from participatory and qualitative engagement cannot be “verified” in the same way that a randomized control trial allows one to verify the validity of given responses, the data are nevertheless considered valid in the learning that comes from the stories that people report, the interpretations they have of their surroundings, and the analysis of multiple sources of data that triangulate their findings to reveal a pattern of insights. The participatory methodologies toolkit described here could be used as the basis for future studies exploring young peoples’ usage of alcohol and engagement in related unsafe sex in differing contexts, or, if adapted, for use in exploring other sensitive topics around alcohol use with similar populations. Select aspects of the methods may also be useful in the conduct of formative qualitative research used to guide the design and implementation of quantitative research on alcohol, unsafe sex, and young people. Lastly, the application of the toolkit might be useful for a variety of theoretical frameworks and cultures.

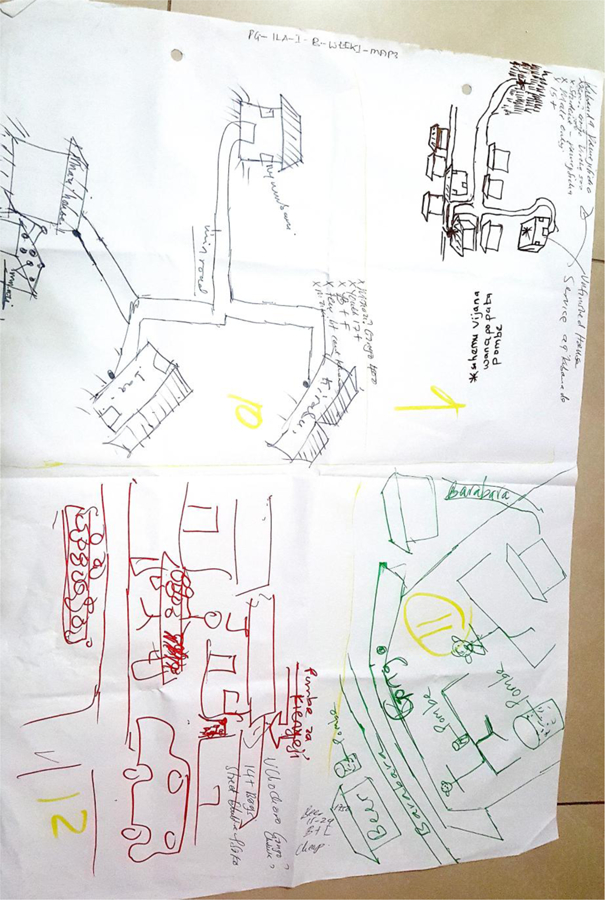

Figure 1.

Four youths’ drawings of maps of where alcohol is available in their communities.

Figure 2.

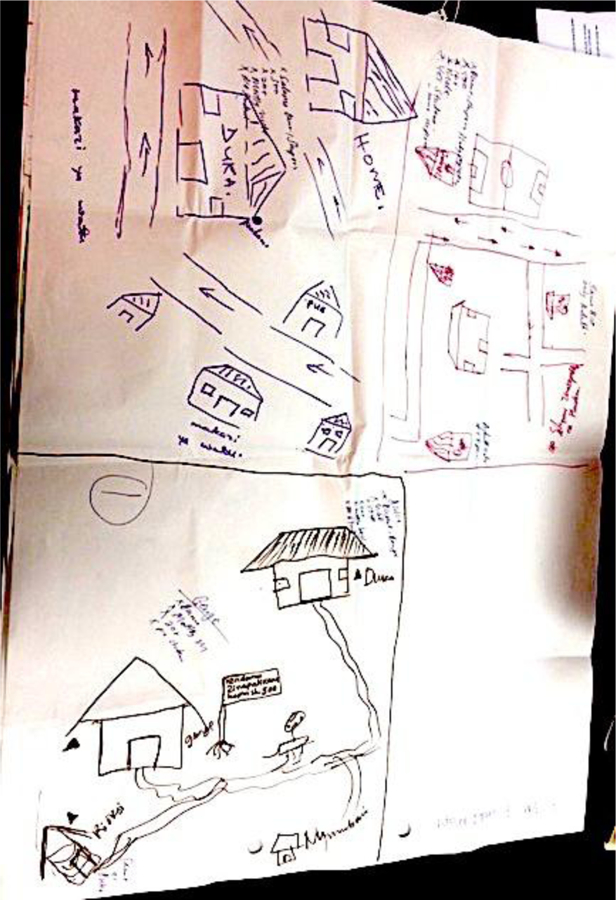

Three adolescents’ drawings of maps of where condoms are available in their communities.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to gratefully acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. We would also like to express our deepest gratitude to our research assistants, our Tanzanian colleagues in the field sites, and to all the Tanzanian young people and adults who kindly provided time and information that made this research possible.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), under Grant #R21 AAA02286801A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Disclosures:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. IRB approval was sought (and given) to waive parental consent given the sensitivity of the research topics, and the likelihood that the youth would be less likely to share their perceptions about alcohol use and sexual activity if parents were notified about the contents of the study. However careful review was conducted to reasonably assure that the content being explored, most of it anonymous, would not cause harm to any participants. Due to the expected high levels of illiteracy across the participants, verbal consent was obtained. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Shisana O, Zungu N, BeLue R, Makofani DM, Shefer T, … Simbayi L (2011). Research capacity building: A US-South African partnership. Global Health Promotion, 18(2), 27–35. 10.1177/1757975911404745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell N, Robson E, Hajdu F, & van Blerk L (2012). Learning from young people about their lives: Using participatory methods to research the impacts of AIDS in southern Africa. Children’s Geographies, 10(2), 169–186. 10.1080/14733285.2012.667918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Astone NM, Decker MR, & Chandra-Mouli V (2014). A conceptual framework for early adolescence: A platform for research. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26(3), 321–331. 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, & Mmari KN (2005). Risk and protective factors affecting adolescent reproductive health in developing countries. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43341/9241593652_eng.pdf;jsessionid=B795A3F85D75D34D1C8C817F9DBDF951?sequence=1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bohn A, & Berntsen D (2008). Life story development in childhood: The development of life story abilities and the acquisition of cultural life scripts from late middle childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1135–1147. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CA, Hahn RA, Elder R, Brewer R, Chattopadhyay S, Fielding J, … Middleton JC (2009). The effectiveness of limiting alcohol outlet density as a means of reducing excessive alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6), 556–569. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ED, Engebretson J, & Chamberlain RM (2006). Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research, 16(6), 836–852. 10.1177/1049732306287525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Fagan AA, Gavin LE, Greenberg MT, Irwin CE, Ross DA, & Shek DTL (2012). Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1653–1664. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60238-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta M, Engelman R, Levy J, Luchsinger G, Merrick T, & Rosen JE (2014). The Power of 1.8 billion: Adolescents, Youth and the Transformation of the Future. UNFPA State of World Population 2014. Accessed online 1/1/20 at: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP14-Report_FINAL-web.pdf

- DiClemente RJ, Swartzendruber AL, & Brown JL (2013). Improving the validity of self-reported sexual behavior: No easy answers. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 40(2), 111–112. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182838474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, … Wechsler H (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries, 61(4), 1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargas-Malet M, McSheery D, Larkin E, & Robinson C (2010). Research with children: Methodological issues and innovative techniques. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(2), 175–192. 10.1177/1476718X09345412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McManus S, & Erens B (2001). Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77(2), 84–92. 10.1136/STI.77.2.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman P, Mortensen J, Berkowitz S, Nowell B, & Lichty L (2013). Photovoice : Using Images to tell Communities ‘ Stories. Participant Handbook. Accessed online 1/1/20 at: http://systemexchange.msu.edu/upload/Photovoice%20Training%20Manual_systemexchange.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, & Steinberg L (2005). Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 625–635. 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth A, & Simpson R (2004). Moonshine markets: Issues in unrecorded alcohol beverage production and consumption. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Simbayi L, Kaufman M, Cain D, & Jooste S (2007). Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science, 8(2), 141–151. 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz A (2017). Photovoice research in education and beyond: A practical guide from theory to exhibition. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo WJ, Masinde JM, & Chege KG (2017). The influence of sex education on adolescents’ involvement in premarital sex and adolescent pregnancies in Arusha City, Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Policy Research and Review, 4(6), 113–124. 10.15739/IJEPRR.17.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan-Brown B, Evans M, & George G (2016). Sexual behaviour of men and women within age-disparate partnerships in South Africa: Implications for young women’s HIV risk. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0159162. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbatia J, Jenkins R, Singleton N, & White B (2009). Prevalence of alcohol consumption and hazardous drinking, tobacco and drug use in urban Tanzania, and their associated risk factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(7), 1991–2006. 10.3390/ijerph6071991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SI, Ralph LJ, Wilson W, & Padian NS (2013). Alcohol production as an adaptive livelihood strategy for women farmers in Tanzania and its potential for unintended consequences on women’s reproductive health. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e59343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch BS, Hewett PC, & Erulkar A (2003). The reporting of sensitive behavior by adolescents: A methodological experiment in Kenya. Demography, 40(2), 247–268. 10.1353/dem.2003.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, & Tamir H (2003). Community-based participatory research: Implications for public health funding. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1210–1213. 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, & Sommer M (2016). Participatory visual methodologies in global public health. Global Public Health, 11(5–6), 521–527. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1170184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnyika KS, Kvale G, & Klepp KI (1995). Perceived function of and barriers to condom use in Arusha and Kilimanjaro regions of Tanzania. AIDS Care, 7(3), 295–306. 10.1080/09540129550126524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, & Ramsoomar L (2016). Addressing adolescent alcohol use in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 106(6), 551–553. 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.10944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mugisha F, Arinaitwe-Mugisha J, & Hagembe BON (2003). Alcohol, substance and drug use among urban slum adolescents in Nairobi, Kenya. Cities, 20(4), 231–240. 10.1016/S0264-2751(03)00034-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzini E, & Lindeboom W (2008). The Urban Transition in Tanzania: Building the Empirical Base for Policy Dialogue. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Obasi AI, Cleophas B, Ross DA, Chima KL, Mmassy G, Gavyole A, … Hayes RJ (2006). Rationale and design of the MEMA kwa Vijana adolescent sexual and reproductive health intervention in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. AIDS Care, 18(4), 311–322. 10.1080/09540120500161983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onya H, Tessera A, Myers B, & Flisher A (2012). Community influences on adolescents’ use of home-brewed alcohol in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 642. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otiso KM (2013). Culture and customs of Tanzania. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Page RM, & Hall CP (2009). Psychosocial distress and alcohol use as factors in adolescent sexual behavior among sub-Saharan African adolescents. Journal of School Health, 79(8), 369–379. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios JF, Salem B, Hodge FS, Albarrán CR, Anaebere A, & Hayes-Bautista TM (2015). Storytelling: A qualitative tool to promote health among vulnerable populations. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26(4), 346–353. 10.1177/1043659614524253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch KE, Komro K. a, Perry CL, Hearst MO, & Farbakhsh K (2007). Outdoor alcohol advertising near schools: What does it advertise and how is it related to intentions and use of alcohol among young adolescents? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 587–596. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, … Mathers CD (2009). Global patterns of mortality in young people: A systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet, 374(9693), 881–892. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer ML, Wight D, Wamoyi J, Mshana G, Hayes RJ, & Ross DA (2006). Farming with your hoe in a sack: Condom attitudes, access and use in rural Tanzania. Studies in Family Planning, 37(1), 29–40. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova S, Giesbrecht N, Bekmuradov D, & Patra J (2009). Hours and days of sale and density of alcohol outlets: Impacts on alcohol consumption and damage: A systematic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 44(5), 500–516. 10.1093/alcalc/agp054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JL, & Tiffany JS (2006). Engaging youth in participatory research and evaluation. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 12(Suppl), S79–87. 10.1097/00124784-200611001-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritche J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, & Ormston R (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B, Toumbourou JW, & Livingston M (2015). The association of alcohol outlet density with illegal underage adolescent purchasing of alcohol. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 146–152. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B, Toumbourou JW, Satyen L, Tooley G, Hall J, Livingston M, & Williams J (2014). Associations between alcohol outlet densities and adolescent alcohol consumption: A study in Australian students. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 282–288. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M (2009). Ideologies of sexuality, menstruation and risk: Girls’ experiences of puberty and schooling in northern Tanzania. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(4), 383–398. 10.1080/13691050902722372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M, Likindikoki S, & Kaaya S (2013a). Boys’ and young men’s perspectives on violence in Northern Tanzania. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(6), 695–709. 10.1080/13691058.2013.779031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M, Likindikoki S, & Kaaya S (2013b). Parents, sons, and globalization in Tanzania: Implications for adolescent health. Boyhood Studies, 7(1), 43–63. 10.3149/thy.0701.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M, Likindikoki S, & Kaaya S (2015). “Bend a fish when the fish is not yet dry”: Adolescent boys’ perceptions of sexual risk in Tanzania. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 583–595. 10.1007/s10508-014-0406-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, & O’Donnell L (2005). Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health, 95(5), 887–893. 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Ali B, Palmier JB, Sikazwe G, & Mayeya J (2011). Alcohol marketing, drunkenness, and problem drinking among Zambian youth: Findings from the 2004 Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2011, 497827. 10.1155/2011/497827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Ali B, Palmier J, Tumwesigye NM, Sikazwe G, Twa-Twa J, & Rogers K (2011). Early alcohol use and problem drinking among students in Zambia and Uganda. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 2(2), e20. 10.4081/jphia.2011.e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, & Donovan JE (2004). Correlates and predictors of violent behavior among adolescent drinkers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(6), 480–492. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Tanzania Population and Housing Census by Age - 2012. Tanzania. Accessed online 1/1/20 at: http://www.tzdpg.or.tz/fileadmin/documents/dpg_internal/dpg_working_groups_clusters/cluster_2/water/WSDP/Background_information/2012_Census_General_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Tanzania Total Population by District - Regions - 2016–2017. Tanzania. Accessed online 1/1/20 at: https://www.nbs.go.tz/index.php/en/census-surveys/population-and-housing-census/178-tanzania-total-population-by-district-regions-2016-2017 [Google Scholar]

- The United Republic of Tanzania. The Intoxicating Liquors Act, 1968 (1968). Accessed online 1/1/2020 at: http://www.tanzania.go.tz/egov_uploads/documents/The_Intoxiacating_Liquors_Act,_28-1968_en.pdf

- UNAIDS. (2016). Country factsheets Tanzania | 2016 HIV and AIDS Estimates. Accessed online 1/1/2020 at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/UNAIDS_GlobalplanCountryfactsheet_tanzania_en.pdf

- UNICEF. (2016). The state of the world’s children 2016: A fair chance for every child. New York: UNICEF. 10.18356/4fb40cfa-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Leiter K, Heisler M, McFarland W, Korte FP, DeMonner SM, … Bangsberg DR (2006). A population-based study on alcohol and high-risk sexual behaviors in Botswana. PLoS Medicine, 3(10), e392. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AL, Wahoush O, Ballantyne M, Gabel C, & Jack SM (2016). Qualitative health research involving indigenous peoples: Culturally appropriate data collection methods. Qualitative Report, 21(12), 2230–2245. [Google Scholar]