Abstract

Purpose

While gender-affirming hormones (GAH) may impact the fertility of transgender and gender diverse (TGGD) youth, few pursue fertility preservation (FP). The objective of this study is to understand youth and parent attitudes toward FP decision-making.

Methods

This study is a cross-sectional survey of youth and parents in a pediatric, hospital-based gender clinic from April to December 2017. Surveys were administered electronically, containing 34 items for youth and 31 items for parents regarding desire for biological children, willingness to delay GAH for FP, and factors influencing FP decisions.

Results

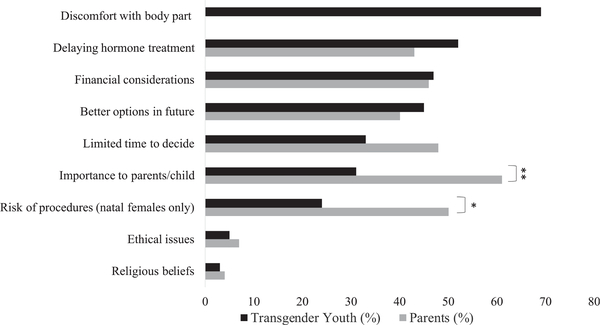

The mean age of youth (n = 64) was 16.8 years, and 64% assigned female at birth; 46 parents participated. Few youth (20%) and parents (13%) found it important to have biological children or grandchildren, and 3% of youth and 33% of parents would be willing to delay GAH for FP. The most common factor influencing youth FP decision-making was discomfort with a body part they do not identify with (69%), and for the parents, whether it was important to their child (61%). In paired analyses, youth and their parents answered similarly regarding youth desire for biological children and willingness to delay GAH for FP.

Conclusions

The majority of TGGD youth and parents did not find having biological offspring important and were not willing to delay GAH for FP. Discomfort with reproductive anatomy was a major influencing factor for youth FP decision-making and their child’s wishes was a major factor for parents. Future qualitative research is needed to understand TGGD youth and parent attitudes toward FP and to develop shared decision-making tools.

Keywords: Transgender youth, Transgender adolescents and young adults, Transgender medicine, Fertility preservation, Gender-affirming hormones, Survey, Fertility counseling, Gender dysphoria

Many transgender and gender diverse (TGGD) youth seek medical interventions to align their body with their gender identity. These treatments include pubertal suppression or initiation of gender-affirming hormones (GAH), which have led to significantly improved psychological outcomes in young adulthood [1]. The impact of GAH on future reproductive function is unclear; previous studies have shown negative impacts of GAH on fertility, but data are limited and conflicting [2–10].

Given the possibility of infertility after receiving GAH, the Endocrine Society, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine have recommended counseling on the risk of fertility impairment and the potential options before starting therapy [11–13]. Even when counseled, studies to date show low fertility preservation (FP) utilization among TGGD youth (<5%), although one study from the Netherlands showed a higher rate of about one third, but this study was limited to transgender females [14–17]. There is a paucity of data in transgender youth on their desire for biological children, knowledge of the FP process, or the factors that influence their decision on whether to pursue FP. A few recent studies have looked at interest in FP by retrospective chart review and surveys, and all found low interest in biological parenthood (24%–35.9%) [14,17–19]. Conversely, in the pediatric cancer population, fertility has been found to be an important consideration in patients and their parents, with one large retrospective study by van Dijk et al. showing 86% of women with a history of childhood cancer desired to have children which was similar to 89% of control women [20–24]. The wishes of the TGGD population are unique, and only one study has explicitly examined factors that may contribute to the decision to pursue FP in 18 transgender adolescents and young adults, and none have investigated the impact of parental influence or factors influencing the parents’ decision [25].

Decisions to initiate GAH therapy are often made before the age of 18; therefore, parental involvement and consent is necessary in FP discussions. However, these decisions may be difficult for parents to make with or for their children [26]. A deeper understanding of how these decisions are made and what factors influence them is necessary to better counsel youth and their parents about FP. Thus, the objective of this study was to understand attitudes toward FP for TGGD youth seeking gender-affirming medical treatment and their parents, and the factors influencing their decisions.

Methods

Between April and December 2017, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of youth and their parents who received care at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Gender and Sexuality Development Clinic. This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Survey instrument

The research team developed two separate questionnaires for youth and their parents. These surveys were adapted from a survey administered to parents of patients with cancer and to postpubertal patients who were planning to undergo testicular tissue cryopreservation for FP before undergoing cancer treatment [24]. The questionnaires focused on factors that influenced their decision. Survey questions were adapted by the study investigators to more accurately target our patient and parent population, and new items were added by the study team as appropriate. The majority of the questions were Likert scale items, excluding demographic information. The youth survey comprised 34 items that addressed knowledge of hormones’ impact on fertility; interest in having biological children and pursuing FP; if they believe they can make a meaningful decision at their age; willingness to delay hormone treatment for FP; their parents’ desire for biological grandchildren as well as various questions addressing factors that may contribute to their decision to pursue FP, such as attitudes toward the procedures involved in FP (including masturbation for males assigned at birth or surgical procedure for females assigned at birth [FAAB]); sex of their ideal future partner; financial, religious, or ethical concerns surrounding FP; discomfort with anatomic reproductive organs; and time to decide. The parent survey consisted of 31 items similar to the youth survey. At the end of the survey, there was an open-ended item: “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about how you have learned about or would like to learn more about fertility preservation? Or, what has been helpful in your decision making process?” Content validation was performed with five experts in the fields of adolescent medicine, endocrinology, transgender health and fertility preservation, including the individuals who developed the original survey.

Study population

Eligible participants were youth aged 12–24 years who were seen at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Gender and Sexuality Development Clinic and their caregivers. Participants were approached and recruited during medical clinic visits. Youth who were not minors were allowed to participate in the study even if they were not accompanied by a parent at the visit or a parent did not wish to participate. Youth who were minors were allowed to participate with parental consent even if the parent chose not to participate themselves. Research assistants consented youth and their caregivers separately. Participants had the option of completing the survey during clinic on a tablet or at their convenience via an email link. Parents gave consent for their children under 18 years, and minors gave their assent. All surveys were administered via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web-based application for electronic collection and management of research data developed specifically around HIPAA security guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as frequencies and percentages, and mean ± standard deviation. For the analysis, due to the distribution of responses, ordinal responses were consolidated into two categories: “agree” (which included strongly agree and agree) and “disagree” (which included neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree). Youth and parent response comparisons were performed using chi-square tests. Univariable logistic regression models tested the predictive relations between the list of influential factors and other characteristics (i.e., age, sex assigned at birth [SAAB] [youth], gender, education [parents]), and willingness to delay hormone therapy or not for FP. Spearman’s rho was used to test the correlations between youth and their respective parent’s responses to selected questions. Observed frequencies, differences in proportions, magnitude of the correlation coefficients, and odds ratios (95% confidence interval) along with two-sided p values were considered when determining the strength of the statistical evidence. Open-ended responses were reviewed by the primary investigator (R.P.) for noting themes related to the responses. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 99 eligible youth and caregivers, we enrolled 66 youth and 52 caregivers. Two youth were excluded from analysis as they reported that their SAAB and their current gender were the same, resulting in 64 youth included in the analysis. Six youth had two parents who completed the questionnaire; therefore, to avoid overrepresenting these family units, we excluded the parent who was randomly assigned “parent 2” (p2), resulting in 46 parents included in the analysis. A sensitivity analysis was performed which showed that the parent responses were overall similar between “parent 1” (p1) and p2. The average age of youth was 16.8 years old; 64% of youth respondents were FAAB. Six percent of the youth described themselves as genderqueer or gender nonconforming, 58% as trans male or male, and 36% as trans female or female; 59% had already started GAH. The majority of both youth and parents were white and non-Hispanic. Three parents were not the biological parents of the youth. Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of transgender youth and their parents

| Characteristics | Youth | Parents |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects included, n | 64 | 46 |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 16.8 (2.1) | 48.3 (6.4) |

| Sex assigned at birth, n (%) | ||

| Male | 23 (36) | n/a |

| Female | 41 (64) | n/a |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Trans male or malea | 37 (58) | 11 (25) |

| Trans female or femaleb | 23 (36) | 32 (73) |

| Genderqueer or gender nonconforming | 4 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 56 (90) | 42 (93) |

| Black | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Multiracial | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 62 (98) | 46 (100) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Not yet graduated from high school | 38 (61) | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate | 23 (37) | 12 (26) |

| College graduate | 1 (2) | 22 (48) |

| Postcollege graduate | 0 | 12 (26) |

| Have received gender-affirming hormones, n (%) | 38 (59) | 21 (46)c |

| Biological parent, n (%) | n/a | 43 (93) |

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

n/a = not applicable; SD = standard deviation.

Youth answered either “trans male” or “male,” parents answered only “male.”

Youth answered either “trans female” or “female”, parents answered only “female.”

The number (percentage) of parents who responded that their child has received gender-affirming hormones.

General attitudes towards FP

Of participants, 20% of youth and 13% of parents responded that it was important to have biological children or grandchildren. The majority of youth (69%) and parents (83%) stated they had considered the impact hormone therapy may have on their or their child’s future fertility, respectively. Similarly, the majority of youth and their parents endorsed that they or their child would be able to make a meaningful decision at this point in their life (69% and 63%, respectively). Very few youth would choose to delay hormone treatment by up to 3 months (3%) to take measures to preserve their fertility, but a higher percentage of parent respondents (33%) would be willing to delay hormone treatment by up to 3 months to preserve their child’s fertility. This difference was statistically significant (p < .001). However, if it were possible to preserve fertility while taking hormones, 34% of youth would choose to do so. A little more than half of the youth (58%) and a little under half of their parents (46%) stated that the idea of having children with their biological gametes conflicted with their affirmed gender. Only 27% and 30% of trans males and trans females, respectively, would be willing to undergo a short, surgical procedure or masturbate (as applicable according to SAAB) to preserve their fertility at the time of the survey. Only 2% of trans males indicated they would feel comfortable using their uterus to carry a pregnancy. The majority of youth (72%) would prefer to make this decision alone, without their parents. Table 2 shows the responses to selected survey questions by youth and parents.

Table 2.

Selected survey responses of transgender youth and their parents

| Agree to the following statement | Youth, n (%) N = 64 |

Parent, n (%) N = 46 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is important to me to be able to have biologic children or grandchildren. | 13 (20) | 6 (13) | .32 |

| I have considered the impact hormone therapy may have on my or my child’s future fertility. | 44 (69) | 38 (83) | 0.1 |

| I would choose or would have chosen to delay hormone therapy (by up to 3 months) to preserve my or my child’s fertility if asked today. | 2 (3) | 15 (33) | <.001 |

| If it were possible to take measures to preserve fertility while taking hormones, I would choose to do it. | 22 (34) | n/a | n/a |

| I believe I or my child can make a meaningful decision about taking steps to preserve fertility at this point in my or their life. | 44 (69) | 29 (63) | .53 |

| The idea of having children with my biologic gametes conflicts with my or my child’s affirmed gender. | 37 (58) | 21 (46) | .21 |

| I am willing to undergo a short, surgical procedure to preserve fertility if asked today. (Asked of natal females only). | 11 (27) | n/a | n/a |

| I would feel comfortable using my uterus to carry a baby. (Asked of natal females only). | 1 (2) | n/a | n/a |

| I would be willing to masturbate in order to collect sperm to freeze for future fertility. (Asked of natal male only). | 7 (30) | n/a | n/a |

| The sex of a partner with whom I may want to parent with impacts my decision to proceed with fertility preservation. | 12 (19) | n/a | n/a |

| Who would you want to be involved in the decision to undergo fertility preservation? | Me alone: 46 (72) Me and my parents 17 (27) My parents alone: 1 (1) |

n/a | n/a |

n/a = not applicable.

Factors influencing decision to pursue FP

Figure 1 shows youth and parent responses when asked if the listed factors influenced their decision to pursue FP. Religious and ethical reasons were not major influences for the majority of respondents (>90% of youth and parents), but about half of youth and parents stated that financial considerations played a role (47% and 46%, respectively). Twice as many parents of trans masculine youth when compared to trans masculine youth themselves (50% vs. 24%, p = .028) agreed that the risk of procedures influenced their decision. Twice as many parents than youth (61% vs. 31%, p = .002) stated that the importance of FP to their child (for parent responders) or their parents (for youth responders) influenced their decision to pursue FP. The most common influential factor for youth was discomfort with a body part they do not identify with (69% agreed) and the most common factor for parents was whether FP was important to their child (61% agreed).

Figure 1.

Factors influencing transgender youth and parents’ decisions to pursue fertility preservation (FP). The bars indicate the percentage of youth (black) and parents (gray) that agree that the factor listed influenced their decision on whether to pursue FP. **61% versus 31%, p = .002; *50% versus 24%, p = .028.

Associations between participant characteristics including age, SAAB (youth only), gender (youth and parents), education level (parents only) as well as how they responded to the proposed factors and if they were willing to delay GAH to undergo FP were explored using univariable logistic regression for youth and parents separately. For both groups, there were no meaningful associations between any characteristics or how they responded to the factors and response to willingness to delay hormones for FP (data not shown).

Paired youth and parent analysis

There were 41 pairs of youth and parents from the same family unit who completed their respective surveys. Youth responses and their respective parent’s responses to selected similar questions were assessed for correlations and are shown in Table 3. There was no correlation between the paired responses to the youth and parent question asking about the youth’s ability to make a meaningful decision at this time in their life or whether the youth has considered the impact GAH have on their fertility, or whether the parent believes that their child understands the possibility of being infertile from GAH. There were correlations between youth and parent responses regarding their willingness to delay therapy (by up to 3 months) to preserve fertility (rs= .58, p = .001), and the importance of the youth having biological offspring according to the child (rs = .41, p = .008), but not according to the parent.

Table 3.

Paired transgender youth-parent responses to selected survey questions

| Youth question | Parent question | Correlation between youth and parent responses |

|---|---|---|

| I believe I can make a meaningful decision about taking steps to preserve my fertility at this time in my life. | I believe my child can make a meaningful decision about taking steps to preserve fertility at this point in his or her or their life. | No rs = .09, p = .56 |

| I have considered the impact hormone therapy may have on my future fertility. | I think my child understands the possibility of being infertile later in life as a result of hormone therapy. | No rs = −.007, p = .97 |

| I would choose or would have chosen to delay hormone therapy (by up to 3 months) to preserve my fertility if asked today. | I would choose to delay giving my child hormone therapy (by up to 3 months) to preserve my child’s fertility if asked today. | Yes rs = .58, p < .001 |

| It is important to me to have biologic children. | I believe having biologic children is important to my child. | Yes rs = .41, p = .008 |

| It is important to my parents to have biologic grandchildren. | It is important to me to have biologic grandchildren. | No rs = .20, p = .22 |

Open-ended responses

Assessment of open-ended responses revealed several themes which are displayed in Table 4 with selected quotes. Themes included gender-based parental role, age and maturity level required to make FP decisions, and adoption as a preferred or alternative option for parenthood.

Table 4.

Key themes identified regarding fertility preservation decisions among transgender youth and parents participating in a cross-sectional survey study

| Theme | Youth | Parent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender-based parental role | “I am a man and I don’t want to be the ‘biological mother’ of anything, that is why I am not preserving my eggs.” “I would prefer as a trans woman to give birth to my children and be able to have them as a combination with my partner, not have someone else involved as a surrogate or egg donor.” “Me not being able to have kids myself was hard for me cuz if I had a kid I would want to be the one to carry my child and because I can’t do that I just chose not to have kids.” |

“My son has no desire to have children, and if he does decide in the future, his female partner would carry the child.” |

| Age and maturity level required to make FP decisions | “I feel like I’m too young to really make ‘official’ and ‘final’ decisions regarding fertility” | “....More information to the child, not sure they can make a decision of that magnitude as a teenager or younger” “Most important is how crucial it would be to my child. Unsure whether he is mature enough to make fully-informed decision on his own.” “....If it was a concern to them (which it is hard to make a 15 realize they may one day want this) then I think it would be a high priority in my eyes.” “I am not sure my child understands that she(he) may not be able to have children in the future. I think at 14 she is not ready to make that decision just yet. 14 is young to be thinking about having children.” |

| Adoption as a preferred or alternative option for parenthood | “I strongly think that adopting a child is just as magical and wonderful as having one, if not more so.” “I have never been interested in having biological children. When I was a small child I instantly knew that I would choose adoption... Fortunately for me, the dysphoria is barely an issue for me because even if I were a cisgender male I’d still adopt children instead.” |

“My child, from a young age, has expressed interest in adopting children only. This is a good fit with their gender transition, so as a family we decided not to pursue fertility preservation at all....” |

Discussion

In this study, we found that the majority of youth and their parents did not find it important to have biological children or grandchildren, respectively, and the majority would not be willing to delay gender-affirming hormone treatment to pursue FP. The most common factor influencing youth’s decision was discomfort with a body part with which they do not identify. For parents, the most common factor was whether it was important to their child.

Our findings are concordant with previous survey studies about transgender youth, FP, and desire for biological children [18,19]. Twenty percent of youth in our study agreed that biological parenthood was important to them, which was similar to the findings in the study by Strang et al. [19], another clinic-based population of youth seeking gender-affirming care, who found that 24% of youth desired biological children. A higher percentage (35.9%) was interested in biological parenthood in a study by Chen et al., which surveyed an online sample of TGGD youth regarding interest in FP and parenting options [18]. There may be a variety of reasons for lower rates of youth desiring biological parenthood in our clinic-based sample. The majority of youth in our study had already started hormones (59%) and therefore have already made this decision and may be more likely to say they do not wish to have biological children if they did not choose to undergo FP, whereas relatively few participants in the online study had taken hormones or puberty blockers (3.8%). This difference may indicate that these participants had less dysphoria, poor access to care, or lack of interest in medical affirmation [18].

Delaying GAH for FP is undesirable for the vast majority of our participants as only 3% of youth in our study stated they would be willing to delay hormone therapy (by up to 3 months) to preserve their fertility. There was a tenfold increase (34%) in those that would choose to preserve their fertility while taking hormones if that were an option. Similarly, a recent survey study on FP in TG adolescents showed 78% of FAAB and 87% of males assigned at birth would not consider FP if it meant waiting to start or stopping GAH [17]. At this time, the data on GAH’s impact on fertility outcome are limited by small numbers and variable treatment regimens. However, recent publications have indicated that there may be some preservation of germ cells even while on hormones. Jiang et al. [27] has shown that 80% of testicular tissue in orchiectomized trans women, most of whom continued on estrogen throughout the procedure, contained germ cells, but whether this translates into viable germ cells that are successful in conception is unclear. There have also been publicized reports of trans men conceiving and resulting in live births after taking testosterone [28]. The pediatric population is unique in that they may undergo pubertal suppression at the start of puberty and therefore present a challenge with regard to FP as their reproductive organs have not matured in the typical fashion aligned with their SAAB. A recent article by Rothenberg et al. [29] described a case of a 16-year-old trans male who successfully completed oocyte cryopreservation while continuing on pubertal suppression, although the process resulted in breast development and vaginal bleeding which was distressing to the patient. Prepubertal ovarian and testicular tissue cryopreservation may be an option for this population in the future, but currently these procedures are considered experimental [30]. Future studies focused on devising methods to preserve fertility while continuing on gender-affirming medical therapy may be able to alleviate some of the barriers that prevent TGGD youth and adults from pursuing FP.

Discomfort with a body part they did not identify with was the most common factor that youth agreed contributed to their decision regarding FP and was further exemplified in the open-ended responses. A qualitative study of 32 transgender young adults found that participants described a desire for reproductive anatomy that matched their affirmed gender, and this discordance was a barrier to becoming a biological parent [31]. Similarly, our study found only 2% of FAAB felt comfortable with the idea of using their uterus to carry a baby. Furthermore, in our study twice as many affirmed females found it important to have biological children than affirmed males (30% vs. 15%), although the difference was not statistically significant. This difference may be due to personal or societal expectations of maternal or female identity in which trans women are more likely to want to be a biological parent.

FP in youth is a challenging topic. Young people are being asked to make an important, personal, and mature decision about future wishes to be a biological parent at an age when they may not be able to anticipate their future desires or fully understand the implications of their decision. The majority of youth in our survey did believe they were able to make a meaningful decision at this stage in their life. However, surveys performed in transgender adults in Belgium have found that 39%–54% of trans men and gender nonbinary FAAB and 40% of trans women without children desire children and about one-third of trans men and half of trans women would have considered germ cell cryopreservation if it had been offered [10,32,33]. Another study of transgender young adults without children found that 47% desired to be a parent by having biological offspring [31]. These data suggest that as people age, they may change their minds about biological parenthood. Interestingly, the majority of parents also believed that their child could make a meaningful decision at this stage in their life and were willing to defer to their child’s wishes on FP. Similarly, the questionnaire by Strang et al. regarding FP in TGGD youth was given to the parents of their youth, and they found that 20.8% of the parents in their population wished their child would have biological children someday [19].

While there seems to be alignment between parents and youth in these clinic-based samples, this may not be representative of many families with a transgender child who are in various stages of supporting their child’s identity and access to gender-affirming care. Nahata et al. [26] reported a case of a 16-year-old trans female and her parents who had a strong disagreement about pursuing FP which sparked a multidisciplinary discussion on the topic involving a medical provider, psychologist, and bioethicist. Although the majority of parents in our study agreed that their child could make a meaningful decision at this time in their life, multiple open-ended responses showed concern about their child’s developmental capacity to make this decision.

Our study also found concordance between youth and parents’ responses to selected questions. The paired parent-youth dyad analysis showed that parents tend to feel similarly about their willingness to delay hormone treatment to pursue FP as their own child does. Additionally, parents’ responses regarding their child’s desire to have biological children with their child’s answer was significantly correlated, but when youth were asked about their parents’ desire for biological grandchildren, the answers were not significantly correlated, indicating parents may have a better understanding of their child’s wishes than the reverse.

Our study is not without limitations. We had a small sample size from a single clinic with majority white participants. However, this is one of the largest samples reported of youth-parent pairs regarding FP in trans youth. The limited variability in the responses to the major outcome of interest and small sample size may have limited our ability to detect associations between participant characteristics and influencing factors with the willingness to delay GAH for FP. The age range of the youth included in this study was wide (12–24 years). In future studies, investigators should consider stratifying by age to better understand how to approach families with adolescents at varying developmental stages about FP. There may be a component of sampling bias as individuals who agreed to participate in the study and those who completed the survey may be in some way different than those who declined or did not complete the survey despite expressing interest in participation. For example, parents who completed the survey may have already discussed this topic with their children and thus may have been more willing to answer questions about FP decisions. Our sample was also majority trans-masculine; however, this is generally representative of youth accessing care at large pediatric hospital-based gender clinics [34]. Our survey did not address adoption, which is another option for parenthood and previous studies found that the desire for adoption may be higher than desire for biological children in this population which was also a theme in openended responses in our study [14,17–19].

In conclusion, in our clinic-based sample, we found that the majority of transgender youth and their parents are not prioritizing biological parenthood or grandparenthood, respectively, and would not be willing to delay hormone treatment to pursue FP. However, a significant minority do find it important and yet despite clinic protocols for counseling, FP is rarely utilized in this patient population [14,16]. Future quantitative and qualitative research is needed to explore our preliminary findings in larger samples at various stages of parental support and access to care. Specifically, qualitative work may help to better delineate the process of decision-making between parents and youth, barriers to pursuing FP when desired, and how youth and parents want to learn about this important topic at various stages in the process of accessing gender-affirming care. Ultimately, this investigation may lead to development of new shared decision-making tools that providers and families can use to ensure the best outcomes and improve the process for those who do wish to be a biological parent one day.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

In this clinic-based sample, the majority of transgender and gender diverse youth and their parents were not interested in biological parenthood or grandparenthood. Youth and parents were in agreement that FP was not a priority and should not be a reason for delaying treatment. The study identifies various factors that contributed to their decision.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented as a poster and short oral presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies conference in May 2018.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [K23 MH 102128] (PI: N.D.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- [1].de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, et al. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics 2014;134:696e704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].De Roo C, Lierman S, Tilleman K, et al. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation in female-to-male transgender people: Insights into ovarian histology and physiology after prolonged androgen treatment. Reprod Biomed Online 2017;34:557e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hamada A, Kingsberg S, Wierckx K, et al. Semen characteristics of transwomen referred for sperm banking before sex transition: A case series. Andrologia 2015;47:832e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ikeda K, Baba T, Noguchi H, et al. Excessive androgen exposure in femaleto-male transsexual persons of reproductive age induces hyperplasia of the ovarian cortex and stroma but not polycystic ovary morphology. Hum Reprod 2013;28:453e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pache TD, Chadha S, Gooren LJ, et al. Ovarian morphology in longterm androgen-treated female to male transsexuals. A human model for the study of polycystic ovarian syndrome? Histopathology 1991;19: 445e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Payer AF, Meyer WJ 3rd, Walker PA. The ultrastructural response of human Leydig cells to exogenous estrogens. Andrologia 1979;11:423e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schmidt L, Levine R. Psychological outcomes and reproductive Issues among gender dysphoric individuals. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2015;44:773e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schulze C Response of the human testis to long-term estrogen treatment: Morphology of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells and spermatogonial stem cells. Cell Tissue Res 1988;251:31e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Van Den Broecke R, Van Der Elst J, Liu J, et al. The female-to-male transsexual patient: A source of human ovarian cortical tissue for experimental use. Hum Reprod 2001;16:145e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Pennings G, et al. Reproductive wish in transsexual men. Hum Reprod 2012;27:483e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-Dysphoric/gender-Incongruent persons: An endocrine society clinical Practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:3869e903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-Nonconforming people, Version 7. Int J Transgenderism 2012;13:165e232. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive M. Access to fertility services by transgender persons: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2015;104:1111e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nahata L, Tishelman AC, Caltabellotta NM, et al. Low fertility preservation utilization among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:40e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brik T, Vrouenraets L, Schagen SEE, et al. Use of fertility preservation among a Cohort of Transgirls in The Netherlands. J Adolesc Health 2019;64: 589e93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen D, Simons L, Johnson EK, et al. Fertility preservation for transgender adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:120e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chiniara LN, Viner C, Palmert M, et al. Perspectives on fertility preservation and parenthood among transgender youth and their parents. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:739e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen D, Matson M, Macapagal K, et al. Attitudes toward fertility and reproductive health among transgender and gender-Nonconforming adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2018;63:62e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Strang JF, Jarin J, Call D, et al. Transgender youth fertility attitudes questionnaire: Measure development in Nonautistic and Autistic transgender youth and their parents. J Adolesc Health 2018;62:128e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nahata L, Quinn GP. Fertility preservation in young males at risk for infertility: What Every pediatric provider should Know. J Adolesc Health 2017;60:237e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stein DM, Victorson DE, Choy JT, et al. Fertility preservation Preferences and perspectives among adult male survivors of pediatric cancer and their parents. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2014;3:75e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].van Dijk M, van den Berg MH, Overbeek A, et al. Reproductive intentions and use of reproductive health care among female survivors of childhood cancer. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1167e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ferrante AC, Gerhardt CA, Yeager ND, et al. Interest in learning about fertility Status among male adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2019;8:61e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ginsberg JP, Li Y, Carlson CA, et al. Testicular tissue cryopreservation in prepubertal male children: An analysis of parental decision-making. Pediatr BloodCancer 2014;61:1673e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen D, Kyweluk MA, Sajwani A, et al. Factors Affecting fertility decisionmaking among transgender adolescents and young adults. LGBT Health 2019;6:107e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nahata L, Campo-Engelstein LT, Tishelman A, et al. Fertility preservation for a transgender Teenager. Pediatrics 2018;142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jiang DD, Swenson E, Mason M, et al. Effects of estrogen on spermatogenesis in transgender women. Urology 2019;132:117e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Light AD, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius JM, et al. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:1120e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rothenberg SS, Witchel SF, Menke MN. Oocyte cryopreservation in a transgender male adolescent. N Engl J Med 2019;380:886e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dittrich R, Hackl J, Lotz L, et al. Pregnancies and live births after 20 transplantations of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a single center. Fertil Steril 2015;103:462e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tornello SL, Bos H. Parenting intentions among transgender individuals. LGBT Health 2017;4:115e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].De Sutter P, Verschoor A, Hotimsky A, et al. The desire to have children and the preservation of fertility in transsexual women: A survey. Int J Transgenderism 2002;6 No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Defreyne MS, Van Schuylenbergh J, Motmans J, et al. Parental desire and fertility preservation in assigned female at birth transgender people living in Belgium. Fertil Steril 2020;113:149e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zucker KJ. Epidemiology of gender dysphoria and transgender identity. Sex Health 2017;14:404e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]