Abstract

Objective

Dignity therapy is a life review intervention shown to reduce distress and enhance the quality of life for people with a terminal illness and their families. Dignity therapy is not widely used in clinical practice because it is time and cost prohibitive. This pilot study examined the feasibility and acceptability of dignity therapy delivered through therapist-supported web-based delivery to reduce costs, increase time efficiency, and promote access to treatment.

Methods

This study employed a one-group pre-test post-test design to pilot methods. Australian adults diagnosed with a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months or less were recruited for the study. The primary outcome measure was a Participant Feedback Questionnaire used in previous face-to-face dignity therapy studies. Data regarding therapist time and details about final documents were recorded.

Results

Six people were recruited; four chose to complete the intervention via videoconference and two chose email. Participants reported high levels of acceptability and efficacy comparable to face-to-face delivery; meanwhile therapist time was about 40% less and legacy documents were longer. Participants described dignity therapy online as convenient, but technological issues may create challenges.

Conclusions

Online delivery of dignity therapy is feasible and acceptable, reduces therapist time and clinical cost, and appears to reach people who would not otherwise receive the therapy. Dignity therapy via email may have the greatest potential to reduce time and cost barriers. This pilot study demonstrates a need for further research to determine the full benefits of online delivery of dignity therapy.

Keywords: E-health, dignity therapy, palliative care, life review, end of life care, telepsychology, psychotherapy, counselling, psychosocial care

Background

Dignity therapy is a manualised psychotherapeutic life review intervention that reduces distress and enhances quality of life for people with terminal illness and their families.1,2 During dignity therapy, a therapist invites a person with a life-limiting illness to discuss aspects of their life they want remembered using a flexible ten-question framework.3 The therapy sessions are audio-recorded and transcribed, and the transcript is edited by the therapist and client together until a final document is printed and given to the client, who can then share with others as they wish.3 Dignity therapy allows people to reflect on their life, confront issues related to grief, offer comfort to their loved ones, and provide guidance for the future.1,2

Dignity therapy has a well-established empirical foundation.1,2 The psychotherapy was created by Professor Harvey Max Chochinov and colleagues after conducting foundational research that created a model for understanding dignity-related distress in the terminally ill.4 Dignity therapy was pilot tested in 20053 followed by a large international randomised controlled trial in 2011.5 In these, and in dozens of other studies, recipients of dignity therapy consistently report high satisfaction and benefits to themselves and to their family members.2 Recipients report that dignity therapy increases quality of life, reduces distress, reaffirms identity, strengthens relationships, increases hope and meaning, and addresses a host of other psychosocial concerns.1 Studies also indicate that dignity therapy may benefit family members during their caring experience6,7 and during bereavement.8

Despite this robust theoretical and empirical basis, dignity therapy is not widely used in clinical practice. Research indicates that life review interventions in general, as well as dignity therapy in particular, are relatively time-consuming and expensive to perform, which creates a barrier to clinical implementation.2,9 In two studies that tracked total therapist time, dignity therapy averaged approximately 14 hours10 and 15 hours of therapist time to deliver11 per client. In addition, time spent arranging visits, travel time, waiting time, and cancelled appointments have been noted as common issues that increase the time commitment required to deliver dignity therapy.11 Additional cost barriers exist when providing dignity therapy to people who have high care needs, such as those who have lost the ability to speak or are immobile, and with those who live in rural or remote areas.6,12

Using online technologies to provide dignity therapy has the potential to help overcome these barriers. There are three online modes of service delivery for psychological support – web-based information and psychoeducation, self-guided web-based therapy, and therapist-supported web-based therapy.13 Research indicates that psychological interventions using online modes of delivery can be just as effective as face-to-face therapeutic interventions for people who are unwilling or unable to access more “traditional’ forms of support.14

As such, the aim of this pilot study was to examine the acceptability, efficacy, and feasibility of dignity therapy delivered to adults in Australia living with a life-limiting illness through therapist-supported web-based therapy using smartphones, tablets and computers, to provide more equitable access to the intervention, to reduce costs, and to increase time efficiency. We chose to deliver a “therapist-supported web-based therapy”13 because it corresponds to underlying principles of dignity therapy that emphasise person-centred and dignity-affirming care by health care professionals.15

Methods

Design

This study employed a one-group pre-test post-test design to pilot methods for a larger study. For the purposes of the pilot study findings reported here, the study is a descriptive study.

Participants

A convenience sample of Australian adults diagnosed with a life-limiting illness with a prognosis of six months or less but who were expected to survive at least four weeks where recruited for the study.5,16 Participants were required to have home access to an internet-connected computer, smartphone, or tablet, be able to communicate in English, and be able to provide informed consent. Capacity to provide informed consent was based on a score of 10 or above on the Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration test (BOMC).17 Enrolment occurred between June 2015 and December 2016.

Measures

The primary outcome was the Participant Feedback Questionnaire used in previous dignity therapy research.5,16,18 Use of this measure enabled comparison of results with findings from other dignity therapy studies that involved face-to-face contact. Secondary outcomes were the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,19 the Herth Hope Index,20 and the FACIT-Pal.21 The use of these instruments enabled the research team to pilot methods and acquire data for use in a future study. Demographic data were also collected.

A contact sheet was used by the research team to record data regarding each participant meeting/contact, including the number of therapy sessions, the duration of sessions, costs, and details about final documents. Contact sheets also included brief field notes related to the delivery of the intervention, such as technical issues, participant experiences, the impact of symptoms on the intervention, and therapist observations.

Procedure

Participants were recruited on-line through social media (FaceBook and Twitter) postings and advertisements in Australia (n = 2), and through flyers provided to a cancer nurse coordinator in Western Australia who passed the flyers on to potential participants (n = 4). Potential participants contacted the researchers directly by phone or email, or by completing a short survey linked to social media posts.22 The participant was then mailed or emailed the Participant Information Sheet and Consent form. In a subsequent phone call, after further explaining the research and answering questions, the BOMC was given over the phone23 to ensure the participant could provide informed consent. Written consent was subsequently obtained by mail or email. Demographic data and pre-test measures were collected by online survey or phone at the participant’s choosing. Participants were given the choice to receive the dignity therapy intervention through videoconferencing using Skype or FaceTime, by email, or by text messaging.

Dignity therapy was delivered by two therapist-researchers who were trained by Professor Chochinov in dignity therapy and who had experience performing the intervention in previous dignity therapy studies.5,16 When the therapy interviews were conducted by videoconference or phone, they were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Where they were conducted through email question/answer format, there were no recordings and the emailed interactions served as the transcript. No participants chose to complete the intervention via text.

The therapist who performed the interview shaped the transcribed or emailed responses using the prescribed editing process24 and then re-engaged with the participant using their preferred contact method to further edit and finalise the document. Final documents were printed and mailed to participants, and an electronic copy was provided via email, if requested. One week after the therapy, post-test measures and the Participant Feedback Questionnaire were collected by online survey or mail to reduce response bias.25

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was granted by Murdoch University (HR2015/148). A protocol for minimising risk of emotional and psychological harm was used to increase safety and minimise potential distress resulting from the intervention. The protocol included: 1) a requirement that participants identify an emergency contact who lived with or near them that the researchers could use in case of concern or emergency; 2) debriefing with the participant at the end of each contact; 3) referral to previously identified support services if distress was encountered, and 4) a follow-up letter two weeks after the intervention was completed to remind participants about the emotional support services that were available, if needed.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographic variables, feedback responses and data regarding the time involved with dignity therapy sessions and length of documents.

Results

Demographic information

Participants, five women and one man, ranged from 49 to 76 years old. Two lived in metropolitan areas and four in rural areas of Australia. Four had terminal cancer, one had motor neurone disease, and one did not disclose the diagnosis. Participants were well-educated with all having post-secondary education. (See Table 1 for more demographic information on the study group).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| N = 6 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 1 |

| Female | 5 |

| Age | |

| 40–49 | 1 |

| 50–59 | 3 |

| 60–69 | 1 |

| 70–79 | 1 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 4 |

| Divorced | 2 |

| Living with | |

| Alone | 2 |

| Spouse | 2 |

| Spouse/Children | 2 |

| Education | |

| Post-secondary | 5 |

| Postgrad | 1 |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 4 |

| Metro | 2 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Motor neurone disease | 1 |

| Brain tumour/glioblastoma | 2 |

| Metastatic Breast Cancer | 2 |

| Declined to state | 1 |

| Method used for DT interview | |

| 2 | |

| Videoconference/phone | 4 |

| Method Used for DT editing | |

| 3 | |

| Videoconference/phone | 3 |

Online method(s) used

For the dignity therapy interview, four participants chose to communicate by videoconference and all used Skype. In one instance, Skype was used in audio-only mode as the participant’s internet connection did not support the use of video without dropping or freezing the call. Two participants chose to complete the dignity therapy interview through emailed questions and answers. One participant chose email because she had lost the ability to speak. The other chose email because he preferred privacy, to reflect on his responses, and to go at his own pace.

Three participants chose to complete the editing of the interview documents in conversation with the researcher over the phone or Skype, while the remaining three participants chose to use email conversations to edit documents. The three people who used email included two who chose email for their interviews plus one participant who originally used Skype for the interview, but who wished to change to email for the editing process because she preferred more control and involvement with editing.

Acceptability and efficacy

The participants’ reported levels of acceptability and efficacy were compared to findings in other dignity therapy research, which included a large international randomised controlled trial and an Australian study of dignity therapy with people who have motor neurone disease.5,6 (See Table 2 which reports the results of the feedback survey alongside findings from two other studies which utilised the same survey). This small group who completed dignity therapy online reported slightly higher benefits in many feedback areas.

Table 2.

Results of dignity therapy online participant feedback questionnaire compared to dignity therapy IRCT and dignity therapy for people with MND.

| Dignity therapy online (n = 6) | Dignity therapy IRCT (n = 108) | Dignity therapy with MND (n = 28) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have found DT to be helpful to me | 4.67 (0.52) | 4.23 (0.64) | 4.18 (0.72) | |

| I have found DT to be as helpful as any other aspect of my health care | 3.67 (1.03) | 3.63 (1.04) | 3.50 (0.88) | |

| I believe DT has improved my quality of life | 3.67 (1.21) | 3.54 (0.95) | 3.39 (0.79) | |

| DT has given me a sense of looking after unfinished business | 4.00 (0.63) | 3.35 (1.01) | 3.68 (0.61) | |

| DT has improved my spiritual wellbeing | 3.17 (1.33) | 3.27 (1.09) | 3.36 (0.68) | |

| DT has lessened my sadness or depression | 2.83 (0.41) | 3.11 (1.02) | 3.04 (0.96) | |

| DT has lessened my sense of feeling a burden to others | 2.83 (0.75) | 2.81 (0.98) | 2.96 (0.92) | |

| DT has helped me feel more worthwhile or valued | 3.33 (1.03) | 3.38 (0.93) | 3.50 (0.79) | |

| DT has helped me feel like I am still me | 4.17 (0.75) | 3.81 (0.85) | 3.71 (0.85) | |

| DT has given me a greater sense of having control over my life | 3.33 (0.52) | 3.02 (1.02) | 3.18 (0.77) | |

| DT has helped me accept the way things are | 3.50 (0.55) | 3.39 )1.06) | 3.54 (0.92) | |

| DT has helped me feel more respected and understood by others | 3.17 (0.98) | 3.16 (0.90) | 3.33 (0.98) | |

| DT has helped me feel that i am still able to carry out an important task or fill an important role | 3.83 (0.98) | 3.62 (0.97) | 3.61 (0.99) | |

| I have found DT to be satisfactory | 4.33 (0.82) | 4.26 (0.63) | 4.21 (0.69) | |

| DT made me feel that my life is currently more meaningful | 3.83 (0.98) | 3.55 (1.05) | 3.54 (0.69) | |

| DT has given me a heightened sense of purpose | 4.00 (0.89) | 3.49 (1.04) | 3.32 (0.82) | |

| DT has given me a heightened sense of dignity | 4.17 (0.75) | 3.52 (1.04) | 3.36 (0.87) | |

| DT has lessened my sense of suffering | 3.00 (0.00) | 2.86 (1.04) | 3.00 (0.86) | |

| DT has made me feel more hopeful | 3.33 (0.82) | N/R | 3.25 (0.75) | |

| DT has increased my will to live | 3.50 (1.05) | 2.94 (1.11) | 2.96 (0.98) | |

| DT has helped me feel closer to the people who mean the most to me | 4.00 (0.89) | N/R | 3.63 (0.97) | |

| I believe DT has or will be of help to my family | 4.17 (0.75) | 3.93 (0.80) | 4.00 (0.78) | |

| I believe DT could change the way my family sees or appreciates me | 3.83 (0.75) | 3.58 (1.01) | 3.48 (1.05) | |

| I would recommend DT to other people and family members who are dealing with life-limiting conditions | 4.50 (0.55) | N/R | 3.48 (1.05) | |

| I recommend that DT be made available to other people as an online therapy | 4.33 (0.52) | N/R | N/R | |

Feasibility

Dignity therapy online was found to be feasible based on the information compiled from contact sheets and feedback questionnaires. Most participants noted that the convenience and easy access created by online meetings was very attractive. A few people in rural areas noted that the online meetings gave them access to care they wouldn’t otherwise have. Two people who completed the therapy through email noted that the privacy and reflective time afforded by that method was positive for them. However, technological issues, such as poor internet connections or unfamiliarity with videoconferencing, were noted by some participants as potential barriers although these were overcome by providing flexibility in communication methods and extra support.

Time and cost

Data on contact sheets showed therapist time, including interviews, editing, and support, ranged from 3.5 to 13 hours with a mean of 8.5 hours per participant. This is a significant decrease of approximately 40% from reports in other research that tracked total therapist time and where the mean therapist time was 1410 and 1511 hours per participant. Online meetings also saved travel time and waiting time which have not been tracked in previous research but were mentioned as potential barriers.11 The two participants who completed the intervention by email took the least amount of therapist time to complete (3.5 hours and 7 hours). (See Table 3, Therapist time and document characteristics).

Table 3.

Therapist time and document characteristics

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist interview and editing hours | 6 | 3.5 | 13.0 | 8.500 | 3.2863 |

| Copies requested | 6 | 2 | 7 | 3.67 | 1.751 |

| Page length | 6 | 17 | 61 | 31.67 | 19.552 |

| Word length | 6 | 4605 | 19763 | 9900.17 | 5964.673 |

Length of documents

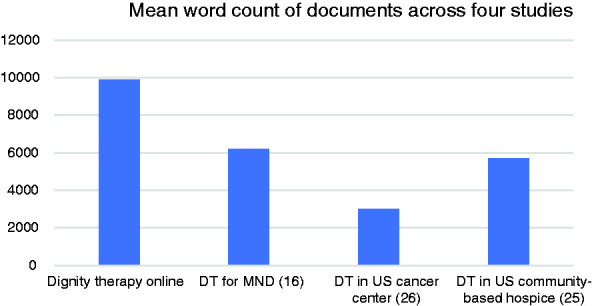

While therapist time was reduced, dignity therapy online created longer legacy documents, ranging from 17 to 61 pages or 4,605 to 19,763 words, when compared with previous research.16,26,27 (See Figure 1 which compares the mean words contained in legacy documents across four different studies which tracked mean word length of dignity therapy documents). Notably, the two participants who completed the intervention by email created the two longest legacy documents (52 and 61 pages). While no research points to the utility of document length, the creation of longer documents suggests that online delivery may provide a better environment for reflection and self-expression.

Figure 1.

Mean word count of dignity therapy documents across four studies.

Discussion

While our research found that participants liked the convenience of using e-health methods, online delivery also created the potential for technical difficulties creating a new potential challenge. This finding is supported by previous research. Passik and colleagues explored delivering dignity therapy in a rural area of the United States through videoconferencing to reduce time and increase opportunity.28 In their study with eight participants, the research team installed a videophone in the participant’s home. Dignity therapy was found to be feasible and acceptable, but the researchers noted there were technical and educational issues with the use of the videophones. The researchers also noted that the time commitment was not reduced significantly, and editing documents was overly time consuming. While most people today have personal access to digital devices and our research participants did not require the installation of equipment, our study also suggests that technological difficulties and editing time continue to be important considerations when delivering dignity therapy online. Using common technologies that the participant is already familiar with can overcome this barrier, as well as allowing flexibility to switch methods, e.g. from videoconference to email, or email to phone, when one is not working well for the participant.

Other research has focused on using technology in dignity therapy to reduce therapist time but found new barriers. Beck and colleagues researched a brief dignity therapy intervention in the United States that was part online and part face-to-face with the primary goal of reducing the therapist time.29 In this study with 10 participants, researchers choose three questions from the ten-question dignity therapy framework to discuss face-to-face in a recorded and transcribed interview. Participants were then provided with the transcript of the interview which they edited themselves using personal computers while being supported with three follow-up 5 to 10-minute phone calls. The researchers found that abbreviated dignity therapy only required an estimated 1.75 to 2 hours of therapist time and that participants found dignity therapy helpful to them and their families. However, while the researchers noted that the burden was reduced for therapists, it increased for participants who struggled to find time for the project. Participants also struggled with emotional burden during the time they worked alone on their documents, finding it difficult to confront their mortality and other existential issues alone, and to read their final documents.

The same research group earlier piloted a similar method using a “legacy building web portal”.30 Here, the researchers also performed an abbreviated interview with three questions and then asked participants to edit and finalise their own transcripts using an online platform. This method was unsuccessful and technological problems were the main issue. Research participants found using the web portal to be largely unworkable. Only 45% of participants used the web portal, and 80% of those reported they were dissatisfied with the online program. Most participants in the study abandoned the web portal and edited the document using their own word processing software.

These studies28–30 and ours indicate that integrating technology into dignity therapy delivery has the potential to create new barriers to service provision and uptake. Integrating technology could burden people with a need to learn how to use technology during an already stressful time. Allowing people to use apps or programs that they already regularly use would decrease this burden. With the range and speed of, and access to, relevant technologies increasing, online delivery of psychosocial interventions is likely to increase.

A further challenge is that using technology in dignity therapy has the potential to decrease therapist-client interactions, which might leave clients with insufficient emotional support during a time of existential distress. People who are facing death benefit from having their unique identity and dignity affirmed by caregivers, and by experiencing empathic understanding and social support in their caring relationships.15 Providing choice and flexibility about how to engage with online delivery, including face-to-face options, and offering therapist time as-needed for regular online communication and support, may help to overcome these issues.

Despite these challenges, our results support previous findings that online therapy can be equally beneficial as face-to-face therapy.14,31 Moreover, while many therapists believe that face-to-face interactions are necessary for therapeutic change,32 this research adds to mounting evidence dispelling that belief.

Limitations

Although this study shows promising results for offering dignity therapy online, it has some limitations. The pilot study included a small sample size with an over-representation of female, educated participants. All participants were regular users of smartphones and/or computers. Combining data for participants who completed the intervention via email with those who used videoconferencing may have skewed therapist time downward and the document length upward. These factors may inhibit generalizability of the study results and suggests more research is needed. Future research is suggested with a larger population, which examines differences in email versus videoconference delivery, and which explores whether there is any relationship between document length and benefits experienced by dying people and their families.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this paper suggest that it is feasible for dignity therapy to be delivered online to save therapist time and clinical cost. Research participants reported slightly higher acceptability using this method than reports in previous research with traditional face-to-face meetings. Online delivery appeared to be an effective way to reach people who would otherwise not be offered or engage with dignity therapy face-to-face. Dignity therapy by email appears to have the most potential to reduce time and cost barriers while simultaneously creating longer documents.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Celine Fournier for her research assistance with ethics approval, recruitment and data gathering, and Dr Robert Kane and Dr Rachael Moorin for their input into the study protocol.

Contributorship

BB researched literature and conceived the study. All authors were involved in protocol development. BB gained ethical approval, recruited participants, performed data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was granted by Murdoch University (HR2015/148).

Funding

This work was supported by the School of Health Professions, Murdoch University.

Guarantor

BB.

Peer Review

This manuscript was reviewed by reviewers who have chosen to remain anonymous.

Trial Registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12615000800527

ORCID iD

Brenda Bentley https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4663-9662

References

- 1.Bentley B, O'Connor M, Shaw J, et al. A narrative review of dignity therapy research. Aust Psychol 2017; 52: 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, et al. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chochinov H, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 5520–5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chochinov HM, Hack T, McClement S, et al. Dignity in the terminally ill: a developing empirical model. Soc Sci Med 2002; 54: 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncology 2011; 12: 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley B, O'Connor M, Breen LJ, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for family carers of people with motor neurone disease. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scarton LJ, Boyken L, Lucero RJ, et al. Effects of dignity therapy on family members: a systematic review. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2018; 20: 542–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClement S, Chochinov HM, Hack T, et al. Dignity therapy: family member perspectives. J Palliat Med 2007; 10: 1076–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keall RM, Clayton JM, Butow PB. Therapeutic life review in palliative care: a systematic review of quantitative evaluations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 49: 747–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bentley B. Dignity therapy: a psychotherapeutic intervention to enhance the end of life experience for people with motor neurone disease and their family carers. Published thesis. School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, Perth, 2014.

- 11.Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for older people in care homes: a phase II randomized controlled trial of a brief palliative care psychotherapy. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentley B, O'Connor M. Counselling people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Age 2017; 30: 50–59.

- 13.Barak A, Klein B, Proudfoot JG. Defining internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Ann Behav Med 2009; 38: 4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barak A, Hen L, Boniel-Nissim M, et al. A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J Technol Human Services 2008; 26: 109–160. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ 2007; 335: 184–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentley B, O'Connor M, Kane R, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e96888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, et al. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer; a randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011; 1: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond A, Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361– 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 1992; 17: 1251–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyons K, Bakitas M, Hegel M, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-palliative care (FACIT-Pal) scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 37: 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster Akard T, Gerhardt C, Hendricks-Ferguson V, et al. Facebook advertising to recruit pediatric populations. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 692–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawas C, Karagiozis H, Resau L, et al. Reliability of the blessed telephone information-memory-concentration test. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8: 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chochinov HM. Dignity therapy: final words for final days. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed Los Angeles: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johns S. Translating dignity therapy into practice: effects and lessons learned. Omega (Westport) 2013; 67: 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montross L, Winters KD, Irwin SA. Dignity therapy implementation in a community-based hospice setting. J Palliat Med 2011; 14: 729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Leibee S, et al. A feasibility study of dignity psychotherapy delivered via telemedicine. Palliat Support Care 2004; 2: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AM, Cottingham A, Stutz P, et al. Abbreviated dignity therapy for adults with advanced-stage cancer and their family caregivers: qualitative analysis of a pilot study. Palliat Support Care 2019; 17: 262–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernat JK, Helft PR, Wilhelm LR, et al. Piloting an abbreviated dignity therapy intervention using a legacy-building web portal for adults with terminal cancer: a feasibility and acceptability study. Psychooncology 2015; 24: 1823–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, et al. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PloS One 2010; 5: e13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rees CS, Stone S. Therapeutic alliance in face-to-face versus videoconferenced psychotherapy. Profession Psychol: Res Pract 2005; 36: 649–653. [Google Scholar]