Abstract

Mammaglobin B, also referred to as secretoglobin family 2A member 1 (SCGB2A1), has been reported to be highly expressed in uterine corpus endometrial cancer (UCEC) compared with in the normal endometrium. However, the prognostic value of SCGB2A1 in UCEC remains unclear. The Oncomine, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium databases were used to explore the differential expression of SCGB2A1. Furthermore, data of patients with UCEC were downloaded from TCGA, and logistic regression analysis, survival analysis, univariate and multivariate analyses, and nomogram construction were performed to identify its prognostic value in UCEC. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was utilized to estimate the mechanisms of SCGB2A1 in UCEC. Finally, immune infiltration of SCGB2A1 in UCEC was analyzed using the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource. Decreased mRNA and protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 were significantly associated with poor prognostic clinicopathological characteristics (all P<0.05). Additionally, low expression levels of SCGB2A1 were associated with decreased survival of patients with UCEC compared with high expression levels of SCGB2A1. Furthermore, the independent prognostic value of SCGB2A1 in UCEC was identified by univariate and multivariate analyses. A nomogram based on 6 variables, including SCGB2A1 expression, was developed for the estimation of the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probability in UCEC. Additionally, GSEA suggested that the vascular endothelial growth factor, PTEN, platelet-derived growth factor, DNA repair, KRAS signaling, and PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathways were differentially enriched in the low SCGB2A1 expression phenotype. Finally, high infiltration levels of CD8+ T cells were associated with SCGB2A1 in UCEC and this was associated with prognosis. The present results indicated that SCGB2A1 may be a promising independent prognostic factor in UCEC. These signaling pathways may be crucial for the regulation of UCEC via SCGB2A1.

Keywords: secretoglobin family 2A member 1, mammaglobin B, uterine corpus endometrial cancer, prognosis, The Cancer Genome Atlas, Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium

Introduction

Uterine corpus endometrial cancer (UCEC) is the second most prevalent type of malignancy among women in the United States of America (1). Despite the rapid development of the modern medical industry, the mortality of UCEC has been continuously increasing (2). Due to a lack of effective therapeutic strategies, the 5-year survival rate of patients with advanced-stage disease is only 16%. However, patients diagnosed at an early stage have a favorable prognosis (3,4). Recently, cancer antigen 125 (CA125) and human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) have been utilized as serum biomarkers in UCEC; however, they only have modest effects due to relatively low predictive accuracy (5–7). Therefore, it is necessary to identify reliable molecular biomarkers to predict prognosis, guide treatments and monitor recurrence.

Mammaglobin B, also referred to as secretoglobin family 2A member 1 (SCGB2A1), is a member of the uteroglobin superfamily which is localized on chromosome 11q12.2 and includes nine human secretoglobins (8,9). SCGB2A1 was first isolated from the human endometrium, and it is highly homologous to mammaglobin A (secretoglobin family 2A member 2) (10). Although its biological function has not been clarified, the differential expression and specific significance of SCGB2A1 in various malignancies have been reported (11). SCGB2A1 has been identified as a candidate biomarker for the detection of lymph node micrometastases in breast cancer (12,13) and abdominal cancer types (14). In addition, SCGB2A1 has been considered as a promising diagnostic marker for occult tumor cells in effusions of several malignancies (15,16) and as a potential immunotherapeutic target in ovarian cancer (17). However, to the best of our knowledge, the prognostic value of SCGB2A1 in UCEC has not been reported, although Tassi et al (18) observed the overexpression of SCGB2A1 in endometrioid endometrial cancer.

The present study assessed the prognostic significance of SCGB2A1 in UCEC using bioinformatics. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to further explore the function of SCGB2A1. A number of other databases were utilized to explore the significance of SCGB2A1 in transcriptomics, proteomics, and the immune microenvironment. In conclusion, the present study may provide further insights into potential therapeutic targets in UCEC.

Materials and methods

Oncomine database analysis

The Oncomine database (http://www.oncomine.com) (19) was utilized to compare the differential expression levels of SCGB2A1 between tumor and normal tissues in various tumor types. The threshold was set according to the following values: P<0.0001; fold change >2; and gene ranking of all.

Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) database analysis

The CPTAC database enables large-scale proteome and genome analyses, in order to understand the molecular basis of cancer (20). UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu) (21), a comprehensive web resource for analyzing cancer-omics data, includes CPTAC analysis for various tumor types. The analysis of protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC was performed by UALCAN based on the CPTAC database. UALCAN performed the comparison of differential expression between each two groups by using t-tests (22), and similar results from the UALCAN using the same statistical methods have been published previously (23–25). Differential protein expression of SCGB2A1 between UCEC and normal tissues, and the association between clinical characteristics and protein expression levels of SCGB2A1, were analyzed. Additionally, all P-values from the UALCAN were adjusted using Bonferroni's correction.

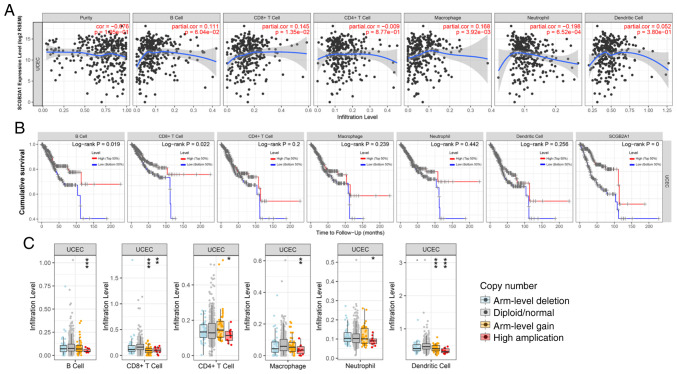

Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) analysis

TIMER (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) (26) is a tool for the systematic analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) across diverse types of cancer in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) (27). TIMER consists of several modules: The ‘DiffExp’ module provides the differential expression between tumor and adjacent normal tissues for genes in TCGA; the ‘Gene’ module provides visualization of the association between gene expression and tumor purity and immune infiltration levels in tumors; the ‘Survival’ module provides survival curves of TIICs at high and low levels and genes in specific tumors; and the ‘SCNA’ module provides the comparison of tumor infiltration levels among tumors with different somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) for a given gene. Defined by Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer 2.0 (28,29), SCNAs include deep deletion (−2), arm-level deletion (−1), diploid/normal (0), arm-level gain (1) and high amplification (2). The infiltration level for each SCNA category in UCEC was compared with that in normal tissues using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. SCGB2A1 was analyzed using the ‘DiffExp’, ‘Gene’, ‘Survival’, and ‘SCNA’ modules.

Downloaded data

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) expression data of UCEC and corresponding clinical data were downloaded from TCGA. The details of RNA-seq data were as follows: Project, TCGA-UCEC; data category, transcriptome profiling; data type, gene expression quantification; workflow type, HTSeq-FPKM. Furthermore, data of normal samples were excluded.

Statistical analysis and nomogram construction

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (v.3.6.2) (30). Expression differences for discrete variables were visualized using boxplots and the survival curve was drawn using the survival package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/views/Survival.html). The association between clinical characteristics and SCGB2A1 expression was determined by logistic regression analysis. Notably, the median value of SCGB2A1 expression was set as the cut-off value. Furthermore, univariate Cox analysis was used to estimate the prognostic value of certain clinicopathologic variables, including age, BMI, grade, stage, peritoneal cytology, pelvic lymph node status, para-aortic lymph node status, histological subtype, myometrial invasion, residual tumor and tumor status. Additionally, multivariate Cox analysis was performed to identify the independent prognostic value of SCGB2A1 with stage, peritoneal cytology, pelvic lymph node status, myometrial invasion, and tumor status.

Following integration of the results of univariate and multivariate Cox analysis, 6 variables (stage, tumor status, peritoneal cytology, pelvic lymph node status, myometrial invasion, and SCGB2A1 expression) were selected for nomogram construction. The rms package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html) in R was used to construct the nomogram.

GSEA

The present study performed GSEA (31), which determines whether an a priori defined set of genes indicates statistically significant differences between 2 biological states, to identify the potential mechanism of SCGB2A1 in UCEC. In the present study, GSEA software v3.0 was used to analyze the ‘h.all.v6.2.symbols.gmt’ and ‘c2.cp.biocarta.v6.2.symbols.gmt’ gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (32). Based on the expression levels of SCGB2A1, ‘high’ and ‘low’ were applied as phenotype labels. For each analysis, 1,000 gene set permutations were run to obtain the normalized enrichment score (NES). False discovery rate <0.25 and normal P<0.05, were used as the cut-off to identify the significantly enriched gene sets.

Results

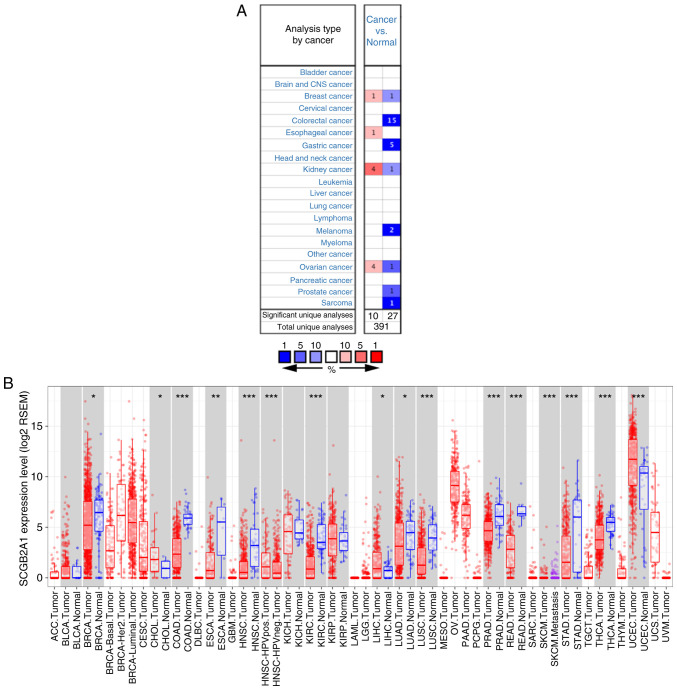

Pan-cancer analysis of SCGB2A1 mRNA expression in different databases

The Oncomine and TCGA databases were utilized to determine the mRNA expression levels of SCGB2A1 in tumor and normal tissues in different tumor types. According to the Oncomine database, SCGB2A1 was expressed at low levels in breast, colorectal, gastric, and kidney cancer, melanoma, ovarian and prostate cancer, and sarcoma, whereas overexpression of SCGB2A1 was identified in breast, esophageal, kidney, and ovarian cancer in some analyses (P<0.0001; Fig. 1A). Detailed information of SCGB2A1 expression in various cancer types based on the Oncomine database is shown in Table SI. In addition, all tumor and adjacent normal tissues in TCGA were analyzed to further comprehend the differential expression of SCGB2A1 (Fig. 1B). The results revealed that SCGB2A1 expression was markedly decreased in breast invasive carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, head and neck cancer, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, prostate, rectum, and stomach adenocarcinoma, and thyroid carcinoma compared with in adjacent normal tissues. However, SCGB2A1 expression was markedly increased in cholangiocarcinoma, liver hepatocellular carcinoma and UCEC tissues compared with in adjacent normal tissues.

Figure 1.

Pan-cancer analysis of SCGB2A1 mRNA expression in different databases. (A) SCGB2A1 mRNA expression in different tumor types compared with normal samples according to different analyses of the Oncomine database. The number represents the count of significant unique analyses. Red represents overexpression of the gene and blue represents low expression of the gene. All P<0.0001 cancer vs. normal. (B) mRNA expression levels of SCGB2A1 in different tumor types analyzed by TIMER based on TCGA. Red indicates tumor tissues and blue indicates normal tissues. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1; TIMER, Tumor Immune Estimation Resource; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; BRCA, breast invasive carcinoma; CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; HNSC, head and neck cancer; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma.

Patient characteristics

Gene expression and clinical data of 545 primary tumors from the TCGA-UCEC project were downloaded in June 2019. After discarding unqualified samples with apparently abnormal data or gene expression data missing (Table SII), the data of 540 patients were retained for further analysis. Notably, a 64-year-old female patient was identified in the database with a weight of 93 kg, but her height was recorded as only 66 cm. As the accuracy of these data could not be verified, the data of this patient was excluded in a previous study (33). Therefore, this data was defined as apparently abnormal data in the present study. The clinicopathological characteristics of these patients, including age, BMI, grade, stage, peritoneal cytology status, lymph node status, histology, myometrial invasion, tumor status, residual tumor, and surgery approach, are shown in Table I. The median age of these patients was 64 years old, ranging between 31 and 90 years old, while the median BMI was 32.2, ranging between 17.4 and 81.6.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients with uterine corpus endometrial cancer (n=540) downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas database.

| Clinical characteristics | Value | % |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 64 (31–90) | |

| Median BMI (range) | 32.2 (17.4–81.6) | |

| Grade, n | ||

| 1 | 97 | 18.3 |

| 2 | 120 | 22.7 |

| 3 | 312 | 59.0 |

| Stage, n | ||

| I | 337 | 62.4 |

| II | 51 | 9.4 |

| III | 123 | 22.8 |

| IV | 29 | 5.4 |

| Peritoneal cytology, n | ||

| Negative | 349 | 86.0 |

| Positive | 57 | 14.0 |

| Pelvic lymph nodes, n | ||

| Negative | 366 | 83.2 |

| Positive | 74 | 16.8 |

| Para-aortic lymph nodes, n | ||

| Negative | 327 | 89.6 |

| Positive | 38 | 10.4 |

| Histology, n | ||

| Endometrioid | 404 | 74.8 |

| Mixed serous and endometrioid | 22 | 4.1 |

| Serous | 114 | 21.1 |

| Myometrial invasion, n | ||

| ≤50% | 314 | 67.1 |

| >50% | 154 | 32.9 |

| Status, n | ||

| With tumor | 78 | 15.5 |

| Tumor-free | 425 | 84.5 |

| Residual tumor, n | ||

| R0 | 370 | 90.7 |

| R1 | 22 | 5.4 |

| R2 | 16 | 3.9 |

| Surgical approach, n | ||

| Minimally invasive | 201 | 38.8 |

| Open | 317 | 61.2 |

BMI, body mass index.

mRNA expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC according to TCGA

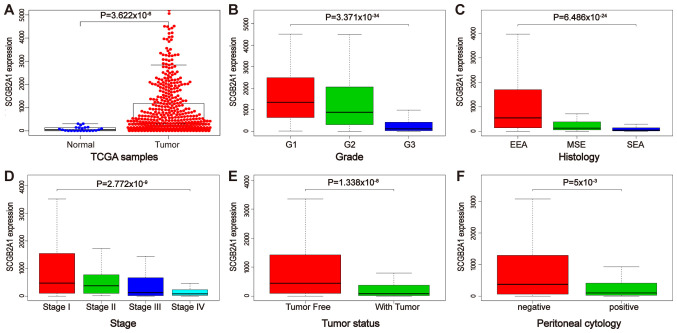

As shown in Fig. 2A and S1, the expression levels of SCGB2A1 in normal tissues were significantly decreased compared with those in UCEC, G3 cancer, stage III or IV, with tumors, and peritoneal cytology-positive tissues (P<0.05), and no significant differential expression was identified between normal tissues and serous endometrial adenocarcinoma and stage IV tissues. Furthermore, the association between SCGB2A1 expression and clinicopathological variables in UCEC was analyzed using boxplots. The results indicated that the decreased expression levels of SCGB2A1 were significantly associated with the grade (P<0.001), stage (P<0.001), tumor status (P<0.001), histological subtype (P<0.001) and peritoneal cytology status (P=0.005) (Fig. 2B-F). Additionally, the results of the logistic regression analysis revealed that decreased expression levels of SCGB2A1 were significantly associated with poor prognostic clinicopathological features, including grade [odds ratio (OR)=0.11 for grade 3 vs. grade 1 or 2; P<0.001], stage (OR=0.35 for stage III or IV vs. stage I or II; P<0.001), peritoneal cytology status (OR=0.37 for positive vs. negative; P=0.001), pelvic lymph node status (OR=0.26 for positive vs. negative; P<0.001), para-aortic lymph node status (OR=0.49 for positive vs. negative; P=0.045), histological subtype (OR=0.09 for serous vs. endometrioid; P<0.001), myometrial invasion (OR=0.47 for >50 vs. ≤50%; P<0.001), status (OR=0.31 for with tumor vs. tumor-free; P<0.001) and residual tumor (OR=0.49 for R1 or R2 vs. R0; P=0.044) (Table II).

Figure 2.

mRNA expression levels of SCGB2A1 according to The Cancer Genome Atlas database. (A) Differential mRNA expression of SCGB2A1 between UCEC and normal tissues. Boxplots of the association between SCGB2A1 mRNA expression and clinicopathological characteristics, including (B) grade, (C) histology, (D) stage, (E) tumor status, and (F) peritoneal cytology. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; EEA, endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma; MSE, mixed serous and endometrioid; SEA, serous endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Table II.

Logistic regression on the association between SCGB2A1 expression and clinical pathological characteristics.

| Clinical characteristics | Total (N) | Odds ratio in SCGB2A1 expression | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (continuous) | 538 | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | <0.01a |

| BMI (continuous) | 509 | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) | <0.01a |

| Grade (3 vs. 1 or 2) | 529 | 0.11 (0.08–0.17) | <0.01a |

| Stage (III or IV vs. I or II) | 540 | 0.35 (0.23–0.51) | <0.01a |

| Peritoneal cytology (positive vs. negative) | 406 | 0.37 (0.20–0.67) | 0.001a |

| Pelvic lymph nodes (positive vs. negative) | 440 | 0.26 (0.14–0.45) | <0.01a |

| Para-aortic lymph nodes (positive vs. negative) | 365 | 0.49 (0.23–0.97) | 0.045a |

| Histology (serous vs. endometrioid) | 518 | 0.09 (0.05–0.16) | <0.01a |

| Myometrial invasion (>50vs. ≤50%) | 468 | 0.47 (0.32–0.70) | <0.01a |

| Status (with tumor vs. tumor free) | 503 | 0.31 (0.18–0.53) | <0.01a |

| Residual tumor (R1 or R2 vs. R0) | 408 | 0.49 (0.24–0.97) | 0.044a |

| Surgical approach (open vs. minimally invasive) | 518 | 0.95 (0.67–1.36) | 0.787 |

P<0.05. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1.

Protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC according to CPTAC database

Analysis of the protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC was performed by UALCAN based on the CPTAC database. As shown in Fig. 3A, the protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC were significantly increased compared with those in normal tissues (P<0.05). Furthermore, the association between SCGB2A1 protein expression and clinicopathological variables in UCEC is shown in Fig. 3B-E. The results revealed that decreased protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 were associated with high grade (P<0.05). No significant association was identified between decreased protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 and serous histological subtype, advanced stage and advanced age.

Figure 3.

Protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC analyzed by UALCAN based on the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium database. (A) Differential protein expression of SCGB2A1 between UCEC and normal tissues. Boxplots of the association between protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 and clinicopathological characteristics, including (B) grade, (C) histology, (D) stage and (E) age. ***P<0.001. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma.

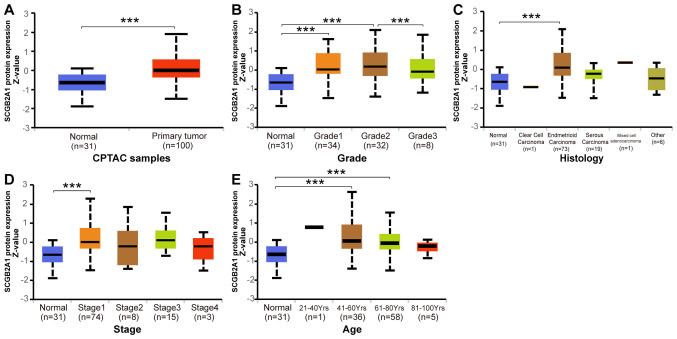

Analysis of the prognostic value of SCGB2A1 mRNA expression and clinicopathological variables in UCEC

The survival curve suggested that low expression levels of SCGB2A1 were associated with poor prognosis in UCEC (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the prognostic value of SCGB2A1 was estimated by univariate Cox analysis (Table III). It was revealed that low expression levels of SCGB2A1, advanced stage, positive peritoneal cytology status and pelvic lymph node status, deep myometrial invasion, ‘with tumor status’ and residual tumor were associated with poor prognosis in UCEC (Table III). As defined in TCGA, ‘with tumor status’ meant that new tumors occurred after operation during the follow-up, while ‘tumor-free status’ meant that no new tumors occurred until the follow-up finished. Finally, multivariate Cox analysis was performed to estimate the independent prognostic value of SCGB2A1. Considering that residual tumor was uncommon in clinical practice, this variable was not included in the multivariate analysis. The results revealed that, in addition to stage, peritoneal cytology, pelvic lymph node status, myometrial invasion, and tumor status, SCGB2A1 was independently associated with poor prognosis in UCEC (hazard ratio, 0.88; P=0.025; Table III).

Figure 4.

Survival analysis for SCGB2A1 in UCEC. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival and SCGB2A1 mRNA expression in patients with UCEC in The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort. (B) Nomogram for prediction of 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probabilities of patients with UCEC based on 6 variables. SCGB2A1 mRNA expression levels were normalized. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma.

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the association between SCGB2A1 expression with overall survival among patients with uterine corpus endometrial cancer.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (continuous) | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.156 | ‒ | ‒ |

| BMI (continuous) | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.284 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Grade (3 vs. 1 or 2) | 1.91 (0.76–4.81) | 0.167 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Stage (III or IV vs. I or II) | 5.62 (2.29–13.79) | 0.000a | 1.27 (0.50–3.22) | 0.615 |

| Peritoneal cytology (positive vs. negative) | 4.21 (1.62–10.97) | 0.003a | 2.75 (1.27–5.97) | 0.010a |

| Pelvic lymph nodes (positive vs. negative) | 1.58 (1.26–1.98) | 0.000a | 1.82 (0.77–4.33) | 0.174 |

| Para-aortic lymph nodes (positive vs. negative) | 1.57 (0.36–6.78) | 0.546 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Histology (serous vs. endometrioid) | 2.35 (0.90–6.14) | 0.081 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Myometrial invasion (>50 vs. ≤50%) | 2.62 (1.09–6.31) | 0.032a | 1.51 (0.71–3.21) | 0.290 |

| Status (with tumor vs. tumor-free) | 6.00 (2.49–14.43) | 0.000a | 3.93 (1.97–7.87) | <0.01a |

| Residual tumor (R1 or R2 vs. R0) | 3.19 (1.16–8.77) | 0.025a | ‒ | ‒ |

| SCGB2A1 expression (continuous) | 0.82 (0.72–0.93) | 0.003a | 0.88 (0.79–0.98) | 0.025a |

P<0.05. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1; HR, hazard ratio.

Construction of the nomogram

A nomogram was constructed for the prediction of 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probabilities of patients with UCEC based on 6 variables, including stage, tumor status, myometrial invasion, peritoneal cytology, pelvic lymph node status, and SCGB2A1 expression (Fig. 4B). According to this nomogram, the variables corresponded to the respective points, and the sum of the six variable points was defined as the total points. Additionally, the estimated 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probability could be obtained based on the total points.

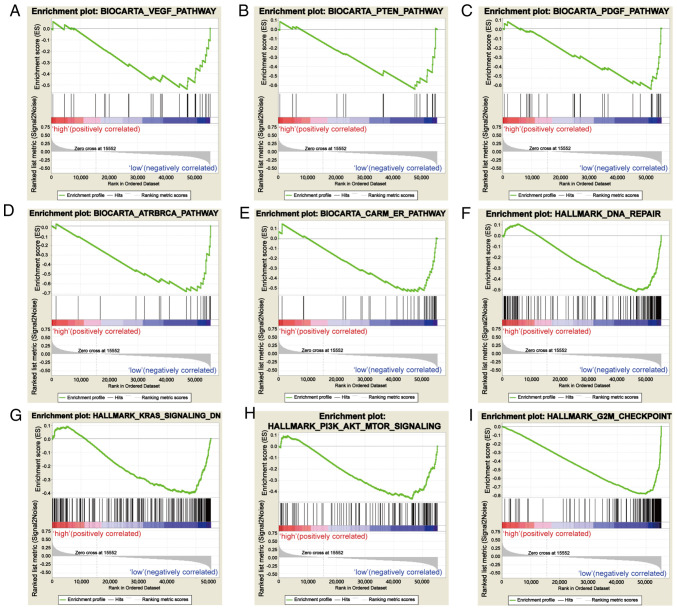

GSEA

Based on the value of the NES, the most significantly enriched signaling pathways were selected. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway, PTEN pathway, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) pathway, DNA repair, coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase (CARM) and estrogen receptor (ER) pathway, KRAS signaling pathway, PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway, ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) and BRCA pathway, and G2M checkpoint were significantly enriched in the SCGB2A1 low-expression phenotype. The details are shown in Table IV.

Figure 5.

Enrichment plots from gene set enrichment analysis. (A) VEGF pathway, (B) PTEN pathway, (C) PDGF pathway, (D) ATR and BRCA pathway, (E) CARM and ER pathway, (F) DNA repair, (G) KRAS signaling pathway, (H) PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway, and (I) the G2M checkpoint were differentially enriched in SCGB2A1-associated uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; ATR, ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related; CARM, coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase; ER, estrogen receptor; SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1.

Table IV.

Gene sets enriched in phenotype low.

| MSigDB collection | Gene set name | NES | NOM P-value | FDR q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c2.cp.biocarta.v6.2.symbols.gmt | BIOCARTA_VEGF_PATHWAY | −1.681 | 0.027 | 0.072 |

| BIOCARTA_PTEN_PATHWAY | −1.703 | 0.025 | 0.070 | |

| BIOCARTA_PDGF_PATHWAY | −1.896 | 0.000 | 0.042 | |

| BIOCARTA_ATRBRCA_PATHWAY | −1.690 | 0.025 | 0.069 | |

| BIOCARTA_CARM_ER_PATHWAY | −1.698 | 0.019 | 0.069 | |

| h.all.v6.2.symbols.gmt | HALLMARK_DNA_REPAIR | −1.722 | 0.044 | 0.069 |

| HALLMARK_KRAS_SIGNALING_DN | −1.675 | 0.009 | 0.073 | |

| HALLMARK_PI3K_AKT_MTOR_SIGNALING | −1.777 | 0.008 | 0.057 | |

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT | −2.278 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

MSigDB, Molecular Signatures Database; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; ATR, ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related; CARM, coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase; ER, estrogen receptor; FDR, false discovery rate; NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM, nominal.

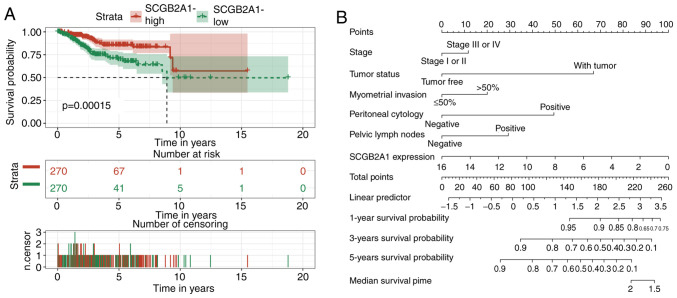

Systematic analysis of immune infiltrates associated with SCGB2A1 mRNA expression in UCEC

TIMER was used to further investigate the association between SCGB2A1 and immune infiltration in UCEC. SCGB2A1 exhibited a significant positive association with the infiltration level of CD8+ T cells (P<0.05) and macrophages (P<0.05), and a negative association with neutrophils (P<0.05) (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, high infiltration levels of B cells and CD8+ T cells were statistically significant in UCEC according to the cumulative survival analysis (P<0.05; Fig. 6B). Finally, the distribution of tumor infiltration levels in UCEC with different SCNAs for SCGB2A1 is shown in Fig. 6C. Compared with those in normal tissues, the infiltration levels of B cells, CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells for high amplification in UCEC were significantly different (P<0.05). In addition, the infiltration levels of CD8+ T cells and dendritic cells for arm-level gain in UCEC were statistically different from those of the normal tissues (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Systematical analysis of immune infiltrates associated with SCGB2A1 mRNA expression in UCEC using the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource. (A) Association between SCGB2A1 mRNA expression and the infiltration levels of tumor-infiltrating immune cells in UCEC. (B) Kaplan-Meier plots for immune infiltrates and SCGB2A1 mRNA expression to visualize survival differences in UCEC. (C) Distribution of tumor infiltration levels among different SCNAs for SCGB2A1 in UCEC. The infiltration levels for each SCNA category in UCEC were compared with those in normal tissues. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. SCGB2A1, secretoglobin family 2A member 1; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; SCNAs, somatic copy number alterations.

Discussion

The present study revealed that decreased expression levels of SCGB2A1 were associated with poor prognostic clinicopathological characteristics and short survival time in UCEC. In addition, the significance of SCGB2A1 in transcriptomics, proteomics and the immune microenvironment was explored using Oncomine, CPTAC and TIMER. However, in certain cancer types, SCGB2A1 expression is controversial. In breast, kidney, and ovarian cancer, SCGB2A1 was identified to be highly expressed in some analyses, while in other analyses, it was identified to be expressed at low levels (Fig. 1A). Based on the detailed information in Table SI, it was proposed that different cancer subtypes and the number of samples may affect SCGB2A1 expression. Additionally, a nomogram based on 6 variables, including SCGB2A1 expression, was developed for the estimation of the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probability in UCEC. GSEA was utilized to further understand the function of SCGB2A1, which revealed that the VEGF, PTEN, and PDGF pathways, DNA repair, CARM and ER, KRAS, and PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathways, and the ATR and BRCA pathway were differentially enriched in the low SCGB2A1 expression phenotype. These results suggested that SCGB2A1 may be considered as a candidate prognostic marker and a novel therapeutic target in UCEC.

As a member of the uteroglobin gene family, SCGB2A1 was first isolated from the human endometrium (10); however, it has rarely been investigated in UCEC. Tassi et al (18) reported that SCGB2A1 was upregulated in endometrioid endometrial cancer tissues compared with normal tissues; however, the aforementioned study presented some limitations due to a lack of prognostic analysis and subgroup analysis in UCEC. The present study revealed the differential expression of SCGB2A1 in UCEC, and that the mRNA and protein expression levels of SCGB2A1 in serous carcinoma were decreased compared with those in endometrioid carcinoma, which suggested that SCGB2A1 may be involved in the carcinogenesis of UCEC cells. Although no significant differential expression of SCGB2A1 was identified between normal tissues and serous carcinoma and stage IV cancer tissues, the expression levels of SCGB2A1 in normal tissues were significantly decreased compared with those in G3 cancer, stage III or IV, with tumor and peritoneal cytology-positive tissues (P<0.05). The specific mechanism requires further exploration. In UCEC, genetic alternations of KRAS and PTEN are common (34,35). PTEN is an essential tumor suppressor gene in UCEC (36), and changes in PTEN could result in disorders of the cell cycle, and abnormal proliferation and differentiation in carcinogenesis (37). As an oncogene, KRAS has a synergistic effect with PTEN in tumorigenesis and upregulates the expression levels of ER (38,39). Furthermore, the activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway via the ER signaling pathway results in cell proliferation (40). The present results revealed that SCGB2A1 was associated with the PTEN, KRAS, and PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathways. Therefore, SCGB2A1 may be involved in the carcinogenesis of UCEC by mediating cell proliferation via these signaling pathways. Although these pathways have not been reported to be associated with SCGB2A1, further exploration is required.

In the past, the prognostic value of SCGB2A1 expression has been analyzed in some specific tumors. Higher expression levels of SCGB2A1 may decrease the risk of recurrence of epithelial ovarian cancer (9). However, upregulation of SCGB2A1 in colorectal cancer decreases the sensitivity to 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin, and promotes chemoresistance and radio-resistance, which results in poor prognosis (16). To the best of our knowledge, the prognostic value of SCGB2A1 in UCEC remains unclear. The results of the present study revealed that decreased SCGB2A1 expression was associated with short survival time in UCEC. Furthermore, a nomogram was constructed to predict the prognosis of patients with UCEC more accurately. Notably, SCGB2A1 expression levels decreased as age, stage, grade, and level of myometrial invasion increased, suggesting that SCGB2A1 may be associated with the progression of UCEC. Furthermore, SCGB2A1 was downregulated in samples with positive peritoneal cytology, and positive pelvic lymph node and para-aortic lymph node statuses, and upregulated in the samples with negative statuses of these indicators. It has been acknowledged that angiogenesis is a common process in the development of tumors, including UCEC (41,42). VEGF acts as a key mediator of tumor angiogenesis, and it is upregulated by the induction of several growth factors and hypoxia (43,44). In addition, overexpression of VEGF in UCEC has been reported to be associated with deep myometrial invasion and lymph node metastasis (45). Therefore, SCGB2A1 may be involved in the progression of UCEC by mediating angiogenesis via the VEGF signaling pathway. Additionally, serum biomarkers are critical during the management of patients with cancer in clinical practice, while advances in UCEC are limited. CA125 and HE4 have been identified as promising serum biomarkers in guiding the management of UCEC, but some limitations remain (46). Further analysis of serum levels of SCGB2A1 may prompt it to become a potential marker for monitoring the development of UCEC and predicting prognosis (47).

The present study performed immune infiltration analysis of SCGB2A1 in UCEC, and the levels of B cells, CD8+ T cells, macrophages and neutrophils were identified to be statistically significant. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been reported regarding the association between SCGB2A1 and TIICs in UCEC, but there are some analyses regarding the effect of TIICs on UCEC (48–50). A previous study revealed that high levels of CD8+ T lymphocytes are an independent favorable prognostic predictor in UCEC (51), which is consistent with the results of the present study. A high density of macrophages is associated with type 2 endometrial cancer (52), and tumor-associated macrophages have been reported to promote the invasion of UCEC cells (53). However, the present results indicated that the infiltration levels of macrophages were positively associated with SCGB2A1. As the immune infiltration analysis by TIMER was limited to the general scope of macrophages, further specific analysis is required.

One of the limitations of the present study was that it was primarily based on in silico analysis, while in vitro and in vivo experiments were lacking. The present study developed a multi-omics analysis and prognostic module, and several databases were utilized to validate the results. However, it remains necessary to conduct further assessments using in vitro and in vivo analyses. Furthermore, the validation of the feasibility of serum SCGB2A1 levels is also essential for clinical practice value.

In conclusion, low expression levels of SCGB2A1 in UCEC may predict poor prognosis, and these signaling pathways may be crucial for the regulatory effect of SCGB2A1 in UCEC. As the present results were primarily based on bioinformatics analysis, further studies are required to validate the role of SCGB2A1 in UCEC and to improve the understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The results shown here are based on the data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/).

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Authors' contributions

JL was responsible for the conception and design of the study, drafting the manuscript, and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. WX collected, analyzed and interpreted the data. YZ made substantial contributions to conception and design, and he contributed to revising this manuscript critically for important intellectual content and overall supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:363–385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks RA, Fleming GF, Lastra RR, Lee NK, Moroney JW, Son CH, Tatebe K, Veneris JL. Current recommendations and recent progress in endometrial cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:258–279. doi: 10.3322/caac.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, Bosse T, González-Martín A, Ledermann J, Marth C, Nout R, Querleu D, Mirza MR, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO consensus conference on endometrial cancer: Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:16–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reijnen C, IntHout J, Massuger LFAG, Strobbe F, Küsters-Vandevelde HVN, Haldorsen IS, Snijders MPLM, Pijnenborg JMA. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical biomarkers for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in endometrial carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2019;24:e880–e890. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YC, Lheureux S, Oza AM. Treatment strategies for endometrial cancer: Current practice and perspective. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29:47–58. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tewari KS, Burger RA, Enserro D, Norquist BM, Swisher EM, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Huang H, Homesley HD, et al. Final overall survival of a randomized trial of bevacizumab for primary treatment of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2317–2328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ni J, Kalff-Suske M, Gentz R, Schageman J, Beato M, Klug J. All human genes of the uteroglobin family are localized on chromosome 11q12.2 and form a dense cluster. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;923:25–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tassi RA, Calza S, Ravaggi A, Bignotti E, Odicino FE, Tognon G, Donzelli C, Falchetti M, Rossi E, Todeschini P, et al. Mammaglobin B is an independent prognostic marker in epithelial ovarian cancer and its expression is associated with reduced risk of disease recurrence. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker RM, Darrow C, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, Watson MA, Fleming TP. Identification of mammaglobin B, a novel member of the uteroglobin gene family. Genomics. 1998;54:70–78. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong RL, Wang Q, Treviño LS, Bosland MC, Chen J, Medvedovic M, Prins GS, Kannan K, Ho SM, Walker CL. Identification of secretaglobin Scgb2a1 as a target for developmental reprogramming by BPA in the rat prostate. Epigenetics. 2015;10:127–134. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1009768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouellette RJ, Richard D, Maicas E. RT-PCR for mammaglobin genes, MGB1 and MGB2, identifies breast cancer micrometastases in sentinel lymph nodes. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:637–643. doi: 10.1309/MMACTXT55L8QTKC1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan EM, Willmore WG, McKay BC, DeRosa MC. In vitro selections of mammaglobin A and mammaglobin B aptamers for the recognition of circulating breast tumor cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14487. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13751-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aihara T, Fujiwara Y, Miyake Y, Okami J, Okada Y, Iwao K, Sugita Y, Tomita N, Sakon M, Shiozaki H, Monden M. Mammaglobin B gene as a novel marker for lymph node micrometastasis in patients with abdominal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2000;150:79–84. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00378-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiegl M, Haun M, Massoner A, Krugmann J, Müller-Holzner E, Hack R, Hilbe W, Marth C, Duba HC, Gastl G, Grünewald K. Combination of cytology, fluorescence in situ hybridization for aneuploidy, and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for human mammaglobin/mammaglobin B expression improves diagnosis of malignant effusions. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:474–483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munakata K, Uemura M, Takemasa I, Ozaki M, Konno M, Nishimura J, Hata T, Mizushima T, Haraguchi N, Noura S, et al. SCGB2A1 is a novel prognostic marker for colorectal cancer associated with chemoresistance and radioresistance. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:1521–1528. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellone S, Tassi R, Betti M, English D, Cocco E, Gasparrini S, Bortolomai I, Black JD, Todeschini P, Romani C, et al. Mammaglobin B (SCGB2A1) is a novel tumour antigen highly differentially expressed in all major histological types of ovarian cancer: Implications for ovarian cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:462–471. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tassi RA, Bignotti E, Falchetti M, Calza S, Ravaggi A, Rossi E, Martinelli F, Bandiera E, Pecorelli S, Santin AD, et al. Mammaglobin B expression in human endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1090–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, Varambally R, Yu J, Briggs BB, Barrette TR, Anstet MJ, Kincead-Beal C, Kulkarni P, et al. Oncomine 3.0: Genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boja E, Tezak Z, Zhang B, Wang P, Johanson E, Hinton D, Rodriguez H. Right data for right patient-a precisionFDA NCI-CPTAC Multi-omics mislabeling challenge. Nat Med. 2018;24:1301–1302. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi BVSK, Varambally S. UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19:649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen F, Chandrashekar DS, Varambally S, Creighton CJ. Pan-cancer molecular subtypes revealed by mass-spectrometry-based proteomic characterization of more than 500 human cancers. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5679. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13528-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huo Q, Li Z, Cheng L, Yang F, Xie N. SIRT7 is a prognostic biomarker associated with immune infiltration in luminal breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:621. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H, Gao S, Chen J, Lou W. UBE2I promotes metastasis and correlates with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:234. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01311-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W, Dai X, Chen Y, Tian F, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Lu J. Significance of STAT3 in immune infiltration and drug response in cancer. Biomolecules. 2020;10:834. doi: 10.3390/biom10060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: A web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomczak K, Czerwinska P, Wiznerowicz M. The cancer genome atlas (TCGA): An immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015;19A:A68–A77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sepulveda JL. Using R and Bioconductor in clinical genomics and transcriptomics. J Mol Diagn. 2020;22:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstråle M, Laurila E, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1739–1740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellinger TH, Smith DD, Ouyang C, Warden CD, Williams JC, Han ES. L1CAM is an independent predictor of poor survival in endometrial cancer-An analysis of the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:336–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minaguchi T, Yoshikawa H, Oda K, Ishino T, Yasugi T, Onda T, Nakagawa S, Matsumoto K, Kawana K, Taketani Y. PTEN mutation located only outside exons 5, 6, and 7 is an independent predictor of favorable survival in endometrial carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2636–2642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson WJ, Hoivik EA, Halle MK, Taylor-Weiner A, Cherniack AD, Berg A, Holst F, Zack TI, Werner HM, Staby KM, et al. The genomic landscape and evolution of endometrial carcinoma progression and abdominopelvic metastasis. Nat Genet. 2016;48:848–855. doi: 10.1038/ng.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witek L, Janikowski T, Bodzek P, Olejek A, Mazurek U. Expression of tumor suppressor genes related to the cell cycle in endometrial cancer patients. Adv Med Sci. 2016;61:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Zhao KN, Li R, Shao R, Chen C. Activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and dual inhibitors of PI3K and mTOR in endometrial cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:3070–3080. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140414095605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tu Z, Gui L, Wang J, Li X, Sun P, Wei L. Tumorigenesis of K-ras mutation in human endometrial carcinoma via upregulation of estrogen receptor. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald ME, Bender DP. Endometrial cancer: Obesity, genetics, and targeted agents. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019;46:89–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee II, Maniar K, Lydon JP, Kim JJ. Akt regulates progesterone receptor B-dependent transcription and angiogenesis in endometrial cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:5191–5201. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vassileva V, Millar A, Briollais L, Chapman W, Bapat B. Genes involved in DNA repair are mutational targets in endometrial cancers with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4095–4099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–845. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology. 2005;69(Suppl 3):S4–S10. doi: 10.1159/000088478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirai M, Nakagawara A, Oosaki T, Hayashi Y, Hirono M, Yoshihara T. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF-A/VEGF-1 and VEGF-C/VEGF-2) in postmenopausal uterine endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:181–188. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Cello A, Di Sanzo M, Perrone FM, Santamaria G, Rania E, Angotti E, Venturella R, Mancuso S, Zullo F, Cuda G, Costanzo F. DJ-1 is a reliable serum biomarker for discriminating high-risk endometrial cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317705746. doi: 10.1177/1010428317705746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernstein JL, Godbold JH, Raptis G, Watson MA, Levinson B, Aaronson SA, Fleming TP. Identification of mammaglobin as a novel serum marker for breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6528–6535. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holub K, Biete A. New pre-treatment eosinophil-related ratios as prognostic biomarkers for survival outcomes in endometrial cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1280. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ning C, Xie B, Zhang L, Li C, Shan W, Yang B, Luo X, Gu C, He Q, Jin H, et al. Infiltrating macrophages induce ERα expression through an IL17A-mediated epigenetic mechanism to sensitize endometrial cancer cells to estrogen. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1354–1366. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang WC, Li CH, Huang SC, Chang DY, Chou LY, Sheu BC. Clinical significance of regulatory T cells and CD8+ effector populations in patients with human endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:5777–5788. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kondratiev S, Sabo E, Yakirevich E, Lavie O, Resnick MB. Intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocytes as a prognostic factor of survival in endometrial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4450–4456. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0732-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly MG, Francisco AM, Cimic A, Wofford A, Fitzgerald NC, Yu J, Taylor RN. Type 2 endometrial cancer is associated with a high density of tumor-associated macrophages in the stromal compartment. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:948–953. doi: 10.1177/1933719115570912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jing X, Peng J, Dou Y, Sun J, Ma C, Wang Q, Zhang L, Luo X, Kong B, Zhang Y, et al. Macrophage ERα promoted invasion of endometrial cancer cell by mTOR/KIF5B-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Immunol Cell Biol. 2019;97:563–576. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request