Abstract

Many strains of Campylobacter jejuni display modified heptose residues in their capsular polysaccharides (CPS). The precursor heptose was previously shown to be GDP-d-glycero-α-D-manno-heptose, from which a variety of modifications to the sugar moiety have been observed. These modifications include the generation of 6-deoxy derivatives and alterations of the stereochemistry at C3, C4, C5, and C6. Previous work has focused on the enzymes responsible for the generation of the 6-deoxy derivatives and those involved in altering the stereochemistry at C3 and C5. However, the generation of the 6-hydroxyl heptose residues remains uncertain due to the lack of a specific enzyme to catalyze the initial oxidation at C4 of GDP-d-glycero-α-D-manno-heptose. Here we reexamine the previously reported role of Cj1427, a dehydrogenase found in C. jejuni NTCC 11168 (HS:2). We show that Cj1427 copurifies with bound NADH thus hindering catalysis of oxidation reactions. However, addition of a co-substrate, α-ketoglutarate, converts the bound NADH to NAD+. In this form, Cj1427 catalyzes the oxidation of l-2-hydroxyglutarate back to α-ketoglutarate. The crystal structure of Cj1427 with bound GDP-d-glycero-α-D-manno-heptose shows that the NAD(H) cofactor is ideally positioned to catalyze the oxidation at C4 of the sugar substrate. Additionally, the overall fold of the Cj1427 subunit places it into the well-defined short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily. The observed quaternary structure of the tetrameric enzyme, however, is highly unusual for members of this superfamily.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The Gram-negative bacterium, Campylobacter jejuni, is considered commensal in many animals, including cattle and chickens (1, 2). However, in humans, C. jejuni is pathogenic, resulting in campylobacteriosis, which is the leading cause of bacterial food-borne infections in the United States and Europe (3, 4). C. jejuni is known to exhibit several carbohydrate-based structures on the surface of the cell, including lipooligosaccharides (LOS) and capsular polysaccharides (CPS) (5–7). These structures are necessary for colonization and contribute to pathogenicity by aiding in the evasion of the host immune response (2). The capsular polysaccharide is composed of repeating units of monosaccharides joined by glycosidic bonds. The structure of the repeating CPS unit of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2) is shown in Scheme 1 (7, 8).

Scheme 1.

Structure of the CPS unit of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2).

The heptose unit is common amongst many different capsular polysaccharide serotypes. Our previous biochemical analysis showed that approximately 77% of the sequenced C. jejuni strains incorporate a heptose residue into their capsular polysaccharides (9). Of the 12 published CPS structures, 9 contain heptose moieties with 13 different structural variations identified (8). The CPS of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (HS:2) contains a single heptose moiety, identified as d-glycero-l-gluco-heptose (7).

Previous bioinformatic analyses and experimental data indicate that all heptose variations in C. jejuni most likely originate from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) (9, 10). This compound was shown to be the initial substrate for the enzymes responsible for subsequent stereochemical modifications in C. jejuni 81–176 (HS:23/36) (11, 12). In C. jejuni strain 11168 the proposed pathway for the conversion of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) to GDP-d-glycero-β-l-gluco-heptose (4) is outlined in Scheme 2 (13). The most logical candidate for the initial oxidation of 1 to GDP-d-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2) is Cj1427. However, this enzyme has previously been reported not to catalyze the oxidation of 1 to 2 (11–13). This observation is difficult to understand since Cj1427 can apparently catalyze the NADH-dependent reduction of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (5) to GDP-6-deoxy-α-d-manno-heptose (6), as illustrated in Scheme 2 (13).

Scheme 2.

(top) Proposed biosynthetic pathway for the conversion of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) to GDP-d-glycero-β-l-gluco-heptose (4) in C. jejuni (13). (bottom) Previously reported reaction catalyzed by Cj1427 from C. jejuni (13).

In this report, we demonstrate that Cj1427 co-purifies with NADH and the nucleotide is unable to be exchanged with exogenous NAD+, preventing the enzyme from catalyzing an oxidation reaction. However, the addition of α-ketoglutarate converts the bound NADH to NAD+ and l-2-hydroxyglutarate. In addition, we present the three-dimensional crystal structures of Cj1427 in complex with either GDP and NAD(H) or GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose and NAD(H). The structure of the GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose/NAD(H) complex reveals that the C4 carbon of the GDP-sugar ligand lies within 3.5 Å of C4 of the nicotinamide ring and that it is appropriately positioned for facile hydride transfer.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Chemicals.

All materials used in this study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Carbosynth, or GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, unless otherwise stated. Escherichia coli strains XL1 Blue and BL21-Gold (DE3) were obtained from New England Biolabs. UV spectra were collected on a SpectraMax340 UV-visible plate reader using 96-well NucC plates. α-Ketoglutarate was purchased from AK scientific (Union City, CA). Oxaloacetate, pyruvate, l- and d-2-hydroxyglutarate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cloning of cj1427 into pET30a+ Expression Vector.

The gene for Cj1427 (Uniprot ID: Q0P8I7) was amplified from the genomic DNA of C. jejuni strain NCTC 11168 (ATCC-700819D-5) using the following primer pair:

5’- GATTG GGATCC ATGTCAAAAAAAGTTTTAATTACAGGTG -3’

5’- GCTAG CTCGAG TTAATTAAAATTTGCAAAGCGATTAACT -3’

Restriction sites for BamHI and XhoI (underlined) were introduced into the forward and reverse primers, respectively. These sites allow for the addition of an N-terminal 6x-His-tag in the pET30a+ expression vector. Procedures for gene amplification, restriction digest, ligation, and plasmid isolation were followed as previously reported (9, 14, 15). The DNA constructs were fully sequenced to confirm the correctly cloned gene in the appropriate vector.

Expression and Purification of Cj1427.

Recombinant pET30a+ plasmid containing the gene for Cj1427 with an N-terminal His-tag was used to transform E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells using the method of heat-shock. Conditions for expression and His-tag protein purification were followed as previously described (14, 15). Briefly, cultures were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium at 37 °C until OD600 = 0.6, followed by the addition of 1.0 mM isopropyl β-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to induce protein expression for 18 h at 22 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C. For purification, the cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM HEPES/K+, pH 8.5, with 250 mM KCl and 10 mM imidazole, lysed by sonication. Cj1427 was purified using the HisTrap HP column following the methods outlined previously (14, 15). Purified Cj1427 was buffer exchanged into 50 mM HEPES/K+, pH 8.5 with 250 mM KCl, and concentrated. The protein concentration was determined by the absorbance at 280 nm and by a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA) (16). The initial extinction coefficient used for Cj1427 was ε280 = 28,100 M−1 cm−1, which was estimated based on the protein sequence including the His-tag and linkers (17). Final yield of purified enzyme was 50–75 mg from 2.0 L of cell culture.

Synthesis of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose.

The synthesis of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) was conducted by addition of Cj1423, Cj1424, Cj1425, GmhB (d-glycero-d-manno-heptose 1,7-bisphosphate 7-phosphatase), and TktA (transketolase) to a single reaction vessel starting from d-ribose-5-P and hydroxypyruvate following the methodology described previously (9). GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) was purified by DEAE anion exchange chromatography as described previously (9, 15).

UV-vis Spectra of Cj1427.

UV-vis spectra of Cj1427 were collected using 96-well NucC plates. The spectra collected of Cj1427 (50 μM) included the following: as-purified enzyme (untreated), heat-denatured enzyme (95 °C for 60 s), and with potential co-substrates (2.0 mM). The co-substrates tested were α-ketoglutarate, oxaloacetate, pyruvate, acetone, dihydroxyacetone, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, and hydroxypyruvate. Precipitated protein from the heat-denaturation sample was removed using a PALL-Omega 10K centrifugal filtration column. In addition to these samples, a 50 μM solution of Cj1427 was treated with α-ketoglutarate (2.0 mM), followed by a series of washing steps (5x) using a Vivaspin 500 3K centrifugal concentrator (GE Healthcare) to remove any remaining α-ketoglutarate. To these samples, 2.0 mM d-2-hydroxyglutarate or 2.0 mM l-2-hydroglutarate was added, and the corresponding spectra were collected.

Direct exchange of NADH bound to Cj1427 with exogenous NAD+ was attempted. Purified Cj1427 (100 μM) was treated with a 10 mM solution of NAD+ in 50 mM HEPES/KCl buffer, pH 7.4. This operation was followed by washing steps with additional solutions of NAD+ (10 mM). After three washes, Cj1427, in the presence of 10 mM NAD+, was allowed to stand at room temperature for 72 h, followed by three subsequent washing steps. The absorbance at 340 nM was monitored.

Cofactor Identification and Occupancy of Cj1427.

Cofactors bound to Cj1427 were determined by FPLC anion exchange chromatography (9, 18). Briefly, solutions of Cj1427 (208 μM) were mixed with water or α-ketoglutarate (2.0 mM) for 60 s, then heat-denatured (95 °C for 60 s) to liberate bound cofactor. The precipitated protein was removed using a PALL-Omega 10K centrifugal filtration device. The resulting flow-through was injected onto a 1.0 mL Resource Q column (GE Healthcare) connected to a BioRad FPLC system. The column was washed with water, and the products were eluted with a linear gradient of 500 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.5). The elution of products was monitored by changes in absorbance at 255 nm and quantified by relative peak area integration. To each sample, a known concentration of NADPH was added and used as an internal standard to quantify the amount of NAD(H) in the sample. A control chromatogram was collected using known concentrations of NAD+ and NADH (150 μM), and of NADP+ and NADPH (300 μM).

Protein Expression and Purification for X-ray Crystallographic Studies.

For crystallization experiments, the gene for Cj1427 was inserted into a pET31(b) vector to generate a C-terminally tagged protein (LEHHHHHH). Cultures of E. coli containing this vector were grown in lysogeny broth supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg/L) and chloramphenicol (50 mg/L) at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8. The flasks were cooled in an ice bath, and the cells were induced with 1.0 mM IPTG at 21 °C for 24 h.

The cells were harvested by centrifugation and frozen as pellets in liquid nitrogen. The pellets were subsequently disrupted by sonication on ice in a lysis buffer composed of 50 mM sodium phosphate, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, and 300 mM sodium chloride (pH 8.0). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation, and the protein was purified at 4 °C utilizing Prometheus Ni-NTA agarose according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All buffers were adjusted to pH 8.0 and contained 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, and imidazole concentrations of 20 mM for the wash buffer and 300 mM for the elution buffer. The purified protein was dialyzed against 4 L of 200 mM NaCl and 10 mM TRIS (pH 8.0). The dialyzed protein was concentrated to ~11.5 mg/mL based on an extinction coefficient of 1.28 (mg/mL)−1 cm−1. Selenomethionine-labeled protein was grown using standard methods, purified, and concentrated as described for the wild-type enzyme.

Crystallization of Cj1427.

Crystals of the protein/GDP complex were grown via hanging drop vapor diffusion at room temperature from 8–11% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 1.0 M tetramethylammonium chloride, and 100 mM HOMOPIPES (pH 5.0) in the presence of 5 mM GDP. The crystals belonged to the monoclinic space group C2 with unit cell dimensions of a = 132.6 Å, b = 84.3 Å and c = 135.5 Å and β = 97.0°. The asymmetric unit contained one tetramer. For X-ray data collection, the crystals were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution composed of 20% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 200 mM NaCl, 1.25 M tetramethylammonium chloride, 12% ethylene glycol, 5.0 mM GDP, and 100 mM HOMOPIPES (pH 5.0). Crystals of the selenomethionine-labeled protein/GDP complex were grown in a similar manner.

Crystals of the complex with GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) were grown via hanging drop vapor diffusion at room temperature from 8–10% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 2% t-butyl alcohol, and 100 mM HOMOPIPES (pH 5.0) in the presence of 2.5 mM GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1). For X-ray data collection, the crystals were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution composed of 26% poly(ethylene glycol) 8000, 350 mM NaCl, 2% t-butyl alcohol, 18% ethylene glycol, 100 mM HOMOPIPES (pH 5.0) and 2.5 mM GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1). The crystals belonged to the orthorhombic space group P21212 with unit cell dimensions of a = 98.7 Å, b = 98.9 Å and c = 72.9 Å and two subunits in the asymmetric unit.

X-ray Data Collection and Processing.

Data from the protein/GDP complex crystals (grown from either the native or the selenomethionine-labeled protein) were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, Structural Biology Center (Beamline 19-BM) and processed with HKL3000 (19). Single isomorphous anomalous data were collected at a wavelength of 0.97919 Å. Data from the GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose complex crystals were collected using a BRUKER D8-VENTURE sealed tube system equipped with HELIOS optics and a PHOTON II detector. These data were processed with SAINT and scaled with SADABS (Bruker AXS). Relevant X-ray data collection statistics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

X-ray Data Collection Statistics and Model Refinement Statistics

| Cj1427-GDP complex (Se-Met) | Cj1427-GDP complex | GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution limits (Å) | 50–2.0 (2.03–2.0)b | 50.0–1.5 (1.53 – 1.5)b | 50.0–2.40 (2.50 – 2.40)b |

| Number of independent reflections | 99927 (4964) | 229896 (11032) | 28260 (3174) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) | 97.7 (94.5) | 98.8 (97.5) |

| Redundancy | 5.0 (4.2) | 3.7 (2.9) | 10.7 (4.2) |

| avg I/avg σ(I) | 12.7 (5.6) | 32.6 (3.4) | 13.3 (3.0) |

| Rsym (%)a | 10.1 (20.7) | 7.9 (30.2) | 9.6 (35.1) |

| cR-factor (overall)%/no. reflections | 16.4/397722 | 21.1/28260 | |

| R-factor (working)%/no. reflections | 16.3/218283 | 20.6/26670 | |

| R-factor (free)%/no. reflections | 18.9/11613 | 28.6/1590 | |

| number of protein atoms | 9898 | 4801 | |

| number of heteroatoms | 1608 | 364 | |

| average B values | |||

| protein atoms (Å2) | 19.9 | 28.2 | |

| ligand (Å2) | 14.0 | 19.7 | |

| solvent (Å2) | 32.1 | 19.1 | |

| weighted RMS deviations from ideality | |||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.009 | |

| bond angles (°) | 1.90 | 1.80 | |

| planar groups (Å) | 0.011 | 0.007 | |

| Ramachandran regions (%)d | |||

| most favored | 97.6 | 95.5 | |

| additionally allowed | 2.2 | 4.4 | |

| generously allowed | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Protein Data Bank codes | 6VO6 | 6VO8 |

Rsym = (∑|I - |/ ∑ I) × 100.

Statistics for the highest resolution bin.

R-factor = (Σ|Fo - Fc| / Σ|Fo|) × 100 where Fo is the observed structure-factor amplitude and Fc. is the calculated structure-factor amplitude.

Distribution of Ramachandran angles according to PROCHECK (24).

Structure Solution and Refinement.

The structure of Cj1427 was solved using Se-SAD data. Out of a potential 44 selenium sites, 40 were identified. The use of the software package CRANK (20) and fourfold averaging allowed for an almost complete tracing of the polypeptide chain. This preliminary model was then used as a starting point for refinement of the structure against the native X-ray data set. The structure of the GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) complex was solved by molecular replacement using the structure of the protein/GDP model as a search probe. All refinements utilized the software package REFMAC (21), and all model building was done with COOT (22, 23). Refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

Computational Docking.

α-Ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate were docked into the active site of chain B of Cj1427 with GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) and NAD(H) bound. The docking search space was confined to a 25.0 Å × 20.0 Å × 20.0 Å box centered near the β-phosphoryl group of the bound GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose. To prepare the receptor for docking, GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose was removed from the active site. Computational docking was conducted using the command-line scripts from the AutoDock Tools Package provided by The Scripps Research Institute with the output set to provide 10 poses (25, 26). A modified version of the flexible side chain method for covalent docking was employed (14, 27). For this method, α-ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate were individually positioned in the active site such that the C2 carbons were superimposed on the C4 carbon of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose and oriented to yield the correct stereochemistry. α-Ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate were then considered to be part of the receptor with the C2 carbon held fixed at the placed location. The remaining bonds of the molecules were considered to be a flexible side chain during subsequent docking routines. For this experiment, a water molecule served as the ligand to be bound. In addition, docking trials were conducted with Arg177 and Arg270, where their side chains were flexible.

Results

Purification and Preliminary Characterization of Cj1427.

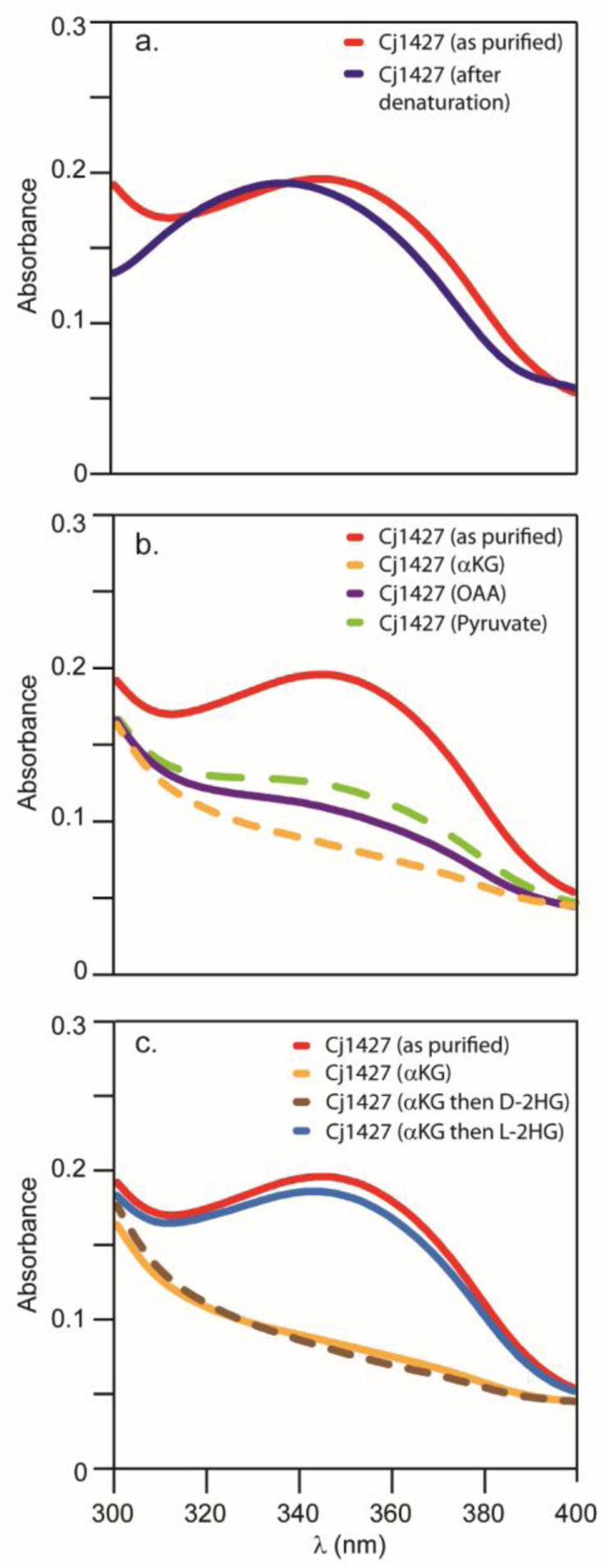

An N-terminal His-tagged derivative of Cj1427 was purified by nickel affinity chromatography to homogeneity. An apparent molecular mass of ~199 kDa for the purified protein was obtained from the elution volume using a calibrated size exclusion column (Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL). The molecular mass of the monomeric protein, including the purification tag and NADH (see below) is 41,565 daltons. The oligometric state of the enzyme is therefore consistent with formation of a tetramer as determined in the three-dimensional structure of this enzyme (see below). The absorbance spectrum of the purified Cj1427 exhibited a maximum at 350 nm (Figure 1a). Heat denaturation of Cj1427, followed by removal of the precipitated protein, demonstrated that the absorbance maximum of the initially bound material is 340 nm (Figure 1a). Previously, McCallum et al., noted that the close Cj1427 homologue, WcaG from C. jejuni strain 81–176, contained a bound reduced nicotinamide cofactor that was not removed during nickel chromatography purification (11). The

Figure 1.

Absorbance spectra of Cj1427. (a) Spectrum of Cj1427 (red) and free NADH cofactor (blue) from denatured Cj1427. Spectra were collected in 50 mM HEPES/KCl buffer, pH 7.4 at 30 °C. (b) Absorbance spectra of Cj1427 (red) with addition of 2.0 mM α-ketoglutarate (orange), 2.0 mM oxaloacetate (purple), or 2.0 mM pyruvate (green). Spectra were collected in 50 mM HEPES/KCl buffer, pH 7.4 at 30 °C after 10 min incubation. (c) Absorbance spectra of Cj1427 (red) and with 2.0 mM α-ketoglutarate (orange). The α-ketoglutarate was subsequently removed and then either d- or l-2-hydroxyglutarate (2.0 mM) was added. These spectra are shown as the brown and blue traces, respectively. Spectra were collected in 50 mM HEPES/KCl buffer, pH 7.4 at 30 °C.

Cofactor Identification and Fractional Occupancy.

To determine the identity of the bound cofactor and its fractional occupancy in Cj1427, ion exchange chromatography was utilized to separate NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH from one another. The chromatographic separation of a mixture of these four cofactors is presented in Figure 2a. To liberate the bound cofactor from Cj1427, the enzyme was heated to 95 °C for 60 s (28) and the supernatant applied to an ion exchange column. The cofactors bound to Cj1427 were shown to be NAD+ and NADH in a ratio of 17:83, based on an integration of the absorbance at 9.5 and 12.5 min, respectively (Figure 2b). To determine the amount of cofactor present, an internal standard of NADPH (36 nmoles) was added to quantify the amount of NAD+ and NADH liberated from 26 nmoles of Cj1427 (Figure 2c) where the concentration of Cj1427 was based on a Bradford assay. From this experiment the total amount of NAD+ and NADH was determined to be 26 nmoles, and thus the enzyme is essentially saturated with bound nucleotide. If the protein concentration was determined from the calculated extinction coefficient at 280 nm (ε = 28,100 M−1 cm−1) plus the contribution from one equivalent of NAD+/NADH (ε = 3,600 M−1 cm−1) the calculated fractional occupancy of the bound nucleotides to Cj1427 was 93%.

Figure 2:

FPLC absorbance traces. (a) Control sample containing a mixture of NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH. (b) Heat-treated sample of purified Cj1427 containing NADH and NAD+. (c) Heat-treated sample of purified Cj1427 containing NADH and NAD+ with NADPH added as an internal standard for quantification. (d) Purified Cj1427 treated with α-ketoglutarate (1.0 mM) followed by heat denaturation to remove protein. Additional details are provided in the text.

Oxidation of Cj1427 by Cosubstrates.

The high occupancy of NADH in the active site of Cj1427 provides a provisional explanation for the inability of this enzyme to catalyze the oxidation of sugar substrates including GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1). Several attempts were made to exchange the bound NADH with exogenous NAD+. Surprisingly, there was no apparent decrease in the absorbance at 350 nm after six 10-fold dilution steps in 10 mM solutions of NAD+ or incubation of the enzyme with 10 mM NAD+ solution for 72 h. This result strongly suggests that the NADH cofactor is tightly bound and cannot be replaced with exogenously added cofactors. Therefore, if Cj1427 functions as an oxidoreductase, then the bound cofactor must be recycled by another substrate/product pair. This situation has previously been noted for the reactions catalyzed by PdxB, WlbA/WbpA, and SerA where α-ketoglutarate functions as the oxidant after each catalytic cycle (28–31). Cj1427 was therefore incubated with α-ketoglutarate, oxaloacetate, and pyruvate as potential oxidants and the absorbance spectrum determined for each reaction mixture (Figure 1b). The absorbance maximum at 350 nm of purified Cj1427 was lost in the presence of added α-ketoglutarate, oxaloacetate, or pyruvate and thus the NADH bound in the active site of Cj1427 was oxidized to NAD+. Other small molecules, including acetone, dihydroxyacetone, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, or hydroxypyruvate at a concentration of 2.0 mM, showed no loss in the absorbance maximum of Cj1427 at 350 nm after 60 min of incubation (data not shown). Ion exchange chromatography was used to confirm that the initially bound NADH was converted to NAD+ in the presence of α-ketoglutarate (Figure 2d).

To demonstrate the ability of the NAD+-bound form of Cj1427 to oxidize molecules and investigate the stereoselectivity, d- and l-2-hydroxyglutarate were mixed with the NAD+-bound form of Cj1427. To generate this form of the enzyme, Cj1427 was incubated with α-ketoglutarate followed by washing steps to remove any remaining α-ketoglutarate. The absorbance spectra show that Cj1427 with bound NAD+ catalyzes the oxidation of l-2-hydroxyglutarate to α-ketoglutarate and NADH (Figure 1c). The same experiment with d-2-hydroxyglutarate shows no change in the absorbance spectrum (Figure 1c).

Structure of Cj1427.

The first structure of Cj1427 was solved using crystals grown in the presence of 5.0 mM GDP. These crystals diffracted to 1.5 Å resolution and contained a full tetramer in the asymmetric unit. The model was refined to an overall R-factor of 16.4%. The observed electron densities are shown in Figure 3a for both the GDP and the tightly bound NAD(H) in subunit A. A ribbon-representation of the subunit is presented in Figure 3b. The overall fold of Cj1427 places it into the well-defined short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) superfamily (32). The nucleotide-binding region adopts a modified Rossmann-fold with a seven-stranded parallel β-sheet flanked on either side by a total of six α-helices. The C-terminal domain provides the binding pocket for the GDP ligand. There is a break in the electron density corresponding to the surface loop defined by Ile125 to Ala130.

Figure 3.

Structure of the Cj1427/NAD(H)/GDP complex. (a) The observed electron densities for the two ligands in subunit A are shown in stereo. These densities were calculated with coefficients of the form Fo - Fc where Fo and Fc are the native and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively. The map was contoured at 3σ. (b) A ribbon representation of one subunit is shown in stereo. The α-helices and β-strands are highlighted in teal and purple, respectively. The bound ligands are drawn in stick representations. Figures 3–6 and 8 were prepared with the software package PyMOL (35).

A ribbon representation of the complete tetramer is presented in Figure 4a, which shows 222 symmetry. The α-carbons for the individual subunits superimpose with root-mean-square deviations of between 0.6 Å to 1.0 Å. Additionally, the total buried surface area between subunits A and B is 2700 Å2, whereas that between subunits B and C is 1700 Å2. The manner in which the subunits form the quaternary structure of Cj1427 is unique amongst SDR superfamily members. Typically, the α-helices defined by Pro90 – Phe107 and Glu 143 – Lys 158 in Cj1427 (as indicated in Figure 3b) provide subunit:subunit interactions within dimers. In higher order quaternary structures, such as tetramers, the subunits assemble as “dimers of dimers.” Importantly, the active sites within the dimers are separated by ~35 Å and are solely contained within each monomer. In the case of Cj1427, however, these α-helices are on the outside of the tetramer as can be clearly seen in Figure 4a. In addition, the C-termini of subunits A and C and subunits B and D project into the active sites of one another.

Figure 4.

(a) Quaternary structure of Cj1427. Whereas the overall subunit fold of Cj1427 places it into the well-defined SDR superfamily, the manner in which the monomers form the tetrameric structure is unprecedented. Typically, the α-helices colored in bright pink form the subunit:subunit interface. In subunits A and C, electron density for both NAD(H) and GDP were observed, whereas in subunits B and D only electron density for the bound NAD(H) was found. (b) The binding of GDP to the protein resulted in a large conformational change in the loop defined by Asn262 to Tyr272 as can be seen by the superpositions displayed in stereo. The purple and green loops correspond to the subunits with or without bound GDP, respectively.

The active sites of subunits A and D contained both NAD(H) and GDP. In the active sites of subunits B and C, however, only tightly bound NAD(H) was observed. The lack of bound GDP resulted in the region defined by Asn262 to Tyr272 adopting different conformations as illustrated by the superpositions of subunits A and B presented in Figure 4b. Indeed, the Type I turn defined by Asp266 to Lys269 moves by over 19 Å. This large conformational change may be, in part, due to crystalline packing interactions given that the corresponding electron density for this region in subunit C is disordered.

A close-up view of the active site in subunit A is displayed in Figure 5. All of the ribose moieties for both the NAD(H) and GDP ligands adopt the C2’-endo pucker. The guanine ring of the GDP is involved in T-shaped and parallel stacking interactions with the side chains of Phe185 and Phe198, respectively. It is further anchored into the active site by hydrogen bonding interactions with the carbonyl oxygen of Val196 and the backbone amide of Phe198. The side chain of Lys242 completes the hydrogen bonding sphere surrounding the guanine group. The carbonyl of Asp179 and the carboxylate of Asp184 lie within 3.2 Å of the GDP ribose. Key side chains involved in positioning the pyrophosphoryl group of the GDP into the active site include Thr168, Arg204, and Arg270. In addition to the various protein interactions, ten water molecules surround the GDP ligand.

Figure 5.

Stereo close-up view of the active site in subunit A. The ligands are highlighted in gray bonds, whereas the protein side chains are displayed in teal. Ordered water molecules are depicted by the red spheres. The dashed lines indicate possible hydrogen bonding interactions within 3.2 Å. Note that Asn311 is colored in pink bonds to emphasize that it belongs to a neighboring subunit in the tetramer.

With respect to the NAD(H) coenzyme, as expected for a member of the SDR superfamily, the nicotinamide ring adopts the syn orientation. Both Tyr144 and Lys148 that belong to the characteristic signature sequence of the SDR superfamily, lie within 3.2 Å of the nicotinamide ribose. The side chains of Arg175 and Arg177 serve to neutralize the negative charges on the pyrophosphoryl group. The adenine and its associated ribose are oriented into the active site by hydrogen bonding interactions with the side chains of Asp57, Asp33 and Gln39 and the backbone amide of Ala58. Strikingly, the side chain of Asn311, which interacts with one of phosphoryl oxygens of the NAD(H) is provided by subunit C. This interaction is highly unusual and is, perhaps, in keeping with the novel quaternary structure observed for Cj1427. Three ordered water molecules are also associated with the coenzyme.

The second structure determined in this investigation was that of the enzyme complexed with NAD(H) and GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1). The crystals utilized for this analysis belonged to the space group P21212 with half of a tetramer in the asymmetric unit. X-ray data were collected to a nominal resolution of 2.4 Å, and the model was refined to an overall R-factor of 21.1 %. Both subunits contained NAD(H) and the GDP-linked sugar. Shown in Figure 6a is the observed electron density corresponding to the ligands in subunit A. The α-carbons for the Cj1427 models with either bound GDP or GDP-sugar superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.3 Å. There are no major changes in the side chain conformations lining the active site with the exception that Asn311 no longer interacts with an NAD(H) phosphoryl oxygen. Indeed, the electron density from Met304 to the C-terminus is disordered. The sugar moiety of the ligand simply replaces the ordered water molecules observed in the enzyme/NAD(H)/GDP complex model. Additionally, the O6’, C6’, C7’ and O7’ atoms of the sugar group displace a bound ethylene glycol observed in the enzyme/NAD(H)/GDP model. Due to the sugar binding, however, the C4 carbon of the nicotinamide ring moves into the binding pocket by ~1 Å.

Figure 6.

(a) Structure of the Cj1427/NAD(H)/GDP-sugar complex. The electron density corresponds to the bound ligands in subunit A. The omit map was calculated according to that described in the legend to Figure 3, and it was contoured at 2σ. (b) A close-up stereo view of the active site near the C4 of the GDP-sugar and the C4 of the NAD(H). The green dashed line emphasizes that these two carbons, separated by ~3.5 Å, are ideally positioned for hydride transfer.

A close-up view of the active site with bound GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose is depicted in Figure 6b. The C4 oxygen of the GDP-sugar lies within 3.2 Å of Tyr144 and Thr146. Previous studies have demonstrated that Tyr144 is typically conserved amongst members of the SDR superfamily although a recent study has reported an example whereby it is replaced with a methionine (33). In cases where the tyrosine is conserved, it has been demonstrated to function as either an active site acid or base depending upon the enzyme under investigation (34). Given its position in Cj1427, it can be postulated that Tyr144 functions as an active site base. As can be seen in Figure 6b, the C4 carbon of the GDP-ligand and the C4 carbon of the nicotinamide ring are ideally positioned for hydride transfer to the si face of the nicotinamide ring. Indeed, the distance separating them is 3.5 Å. It is particularly noteworthy that, as opposed to the enzyme/NAD(H)/GDP complex, Asn311 from the neighboring subunit is no longer positioned in the active site. The electron densities for the C-termini of the two subunits in the asymmetric unit are disordered after Met304.

Docking of α-Ketoglutarate and l-2-Hydroxyglutarate.

Unfortunately, crystals of Cj1427 in complex with either α-ketoglutarate or l-2-hydroxyglutarate were unable to be grown. Soaking pre-formed crystals with these compounds was also unsuccessful. Therefore, computational docking methods were used to visualize how these two molecules might bind in the active site. The active sites of Cj1427 bound with either GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) or GDP are very similar to one another where the putative key residues (Tyr144, Arg177, and Arg270) are superimposable. Initial docking poses with α-ketoglutarate or l-2-hydroxyglutarate place the C2 carbon of these molecules 2.7 Å from where C4 of the heptose moiety of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) is found in the crystal structure and at least 4.0 Å away from C4 of the nicotinamide moiety of NAD(H). Therefore, a modified version of the flexible side chain method for covalent docking was utilized (14, 27). The C2 carbon of α-ketoglutarate or l-2-hydroxyglutarate was positioned in the same location as C4 from the heptose moiety of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose and held fixed. The remaining bonds of these ligands were optimized during the docking routines. The top results are shown in Figure 7. In both cases, the carboxylate moieties of α-ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate are placed in similar positions. The side chain of Arg270 moves slightly, placing it 2.9 Å and 2.7 Å away from the C1 carboxylate group of α-ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate, respectively. For both α-ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate, the C5 carboxylate is found in two primary locations. One is shown in the α-ketoglutarate pose where the C5 carboxylate is positioned 3.0 Å away from Arg177, which has slightly twisted to allow for the new position of the carboxylate. The second pose is shown for l-2-hydroxyglutarate where the C5 carboxylate moiety is positioned between Arg270 and Arg177. Arg270 and Arg177 are 3.7 Å and 3.5 Å away from the C5 carboxylate moiety, respectively. For this pose, there was no significant movement in the Arg177 residue.

Figure 7.

Docking poses of α-ketoglutarate and l-2-hydroxyglutarate. (a) The best docking pose of α-ketoglutarate (teal sticks) in the active site of Cj1427. Shown in teal sticks are the new locations of the side chains of Arg270 and Arg177 residues after docking. Shown in green sticks is the NAD(H) cofactor and original location of key residues (Arg204, Arg270, and Arg177) in the active site. (b) The best docking pose of l-2-hydroxyglutarate (blue sticks) in the active site of Cj1427. Shown in blue sticks is the new location of Arg270 residues after docking. Shown in green sticks is the NAD(H) cofactor and the original location of key residues (Arg204, Arg270, and Arg177) in the active site.

Discussion

Heptose moieties are found in many extracellular structures of C. jejuni, including the lipooligosaccharides and the capsular polysaccharides. A previous bioinformatic analysis showed that 77% of C. jejuni genomes contain the four enzymes required for the biosynthesis of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (9). Due to the high amino acid sequence conservation amongst the four enzymes, the final product, GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1), is believed to be the base unit from which the known derivatives are synthesized (9, 10, 36). As of 2019, there were 13 heptose derivatives that have been identified in various C. jejuni capsular polysaccharides (8). All of these heptose structures can be derived from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose by enzymatic modification of the stereochemistry about C3, C4, C5, or C6. The Creuzenet laboratory has identified the enzymes responsible for many of the stereochemical modifications at C3, C4, and C5 (13). However, the biosynthetic pathway for heptoses that retain a hydroxyl group at C6 of the sugar remain elusive due to the apparent lack of an enzyme to catalyze the formation of the critical GDP-d-glycero-4-keto-d-lyxo-heptose (2) intermediate (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3:

Unidentified oxidation reaction of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose.

Despite the previously proposed regulatory reductase role for WcaG and Cj1427, these enzymes and their close homologues remain the most likely candidates to catalyze the critical initial oxidation required at C4 of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose. This conclusion is based on previous findings that these enzymes are highly similar to one another and their reported ability catalyze the reduction of GDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (5) to GDP-6-deoxy-α-d-manno-heptose (6) (12, 13). As a result, it seemed reasonable to us that these enzymes could catalyze the oxidation of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) to GDP- d-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2).

Given these bioinformatic data, Cj1427 and its homologues appear to serve more of a critical function than previously suggested (12, 13). Here we have shown that Cj1427 copurifies with tightly bound NADH and no observable exchange with exogenous NAD+ could be demonstrated, thus preventing the enzyme from catalyzing multiple turnovers in the oxidation of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1). However, the co-substrate, α-ketoglutarate can convert the bound NADH cofactor to NAD+. The NAD+-bound form of Cj1427 was shown to catalyze the oxidation of l-2-hydroxyglutarate.

This type of recycling mechanism of a tightly bound NAD(H) cofactor has been previously described for a small set of enzymes, specifically PdxB, WlbA, and SerA. PdxB catalyzes the second step of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate biosynthesis in E. coli, converting 4-phospho-d-erythronate to 2-keto-3-hydroxy 4-phosphobutanoate (28). PdxB was shown to contain a tightly bound NAD+ cofactor that was unable to conduct multiple turnovers without added α-ketoglutarate (28). SerA catalyzes the oxidation of 3-phosphoglycerate to 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate in the biosynthesis of l-serine (31). SerA has a 26% amino acid sequence identity with PdxB, despite catalyzing oxidation reactions on similar substrates (31). Like PdxB, SerA requires α-ketoglutarate to recycle the bound NAD(H) cofactor for multiple turnovers (31). A third enzyme, WlbA (also known as WbpB) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires α-ketoglutarate to recycle a bound NAD(H) cofactor to catalyze the oxidation of UDP-N-acetyl-d-glucosaminuronic acid to UDP-N-acetyl-3-keto-d-glucosaminuronic acid (29, 30). WlbA shares 21% and 19% sequence identity to PdxB and SerA, respectively. These low sequence identity values may not be surprising given highly dissimilar substrates, but all three use the same mechanism of recycling a tightly-bound NAD(H) cofactor with α-ketoglutarate to catalyze the oxidation of their respective substrates (28–31). As opposed to Cj1427, however, these enzymes do not belong to the SDR superfamily, and they are A-side (re-face) rather than B-side (si-face) specific dehydrogenases.

It is important to note that all three of these enzymes are found in biosynthetic pathways where the subsequent enzyme functions as an aminotransferase, converting l-glutamate to α-ketoglutarate with transfer of the amino group to the newly formed keto-substrate (28–31). The flux of substrate through the pathway generates the co-substrate necessary to regenerate the tightly bound cofactor required in the formation of the critical keto product. PdxB and SerA rely on a common aminotransferase called SerC to generate α-ketoglutarate; WlbA is followed by the aminotransferase WlbC (29, 30). Characterizations of PdxB, SerA, and WlbA were only successful when assayed in the presence of their required aminotransferase partners to generate α-ketoglutarate (28–31). Unlike PdxB, SerA, and WlbA, Cj1427 and its homologues in C. jejuni do not have an apparent aminotransferase partner to generate α-ketoglutarate. Moreover, PdxB and SerA both yield d-2-hydroxyglutarate as the product of α-ketoglutarate reduction (28, 31), whereas Cj1427 yields l-2-hydroxyglutarate.

One of the striking aspects of Cj1427 is its unique quaternary structure. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, this type of quaternary arrangement of the four subunits has not been observed in other members of the SDR superfamily. A search of the Protein Structure Bank using the software package SSM reveals that Cj1427 most closely aligns with the UDP-glucose epimerases and the UDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratases (37). The mechanisms of these enzymes involve the transient reductions of the tightly bound coenzymes, which are ultimately returned to NAD+. Thus, no recycling mechanisms are required. The top matches include UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase from Methanobrevibacter ruminantium M1 and PAL from Bacillus thuringiensis (38, 39). Shown in Figure 8a is a superposition of the Cj1427 and M. ruminantium M1 epimerase subunits. The α-carbons for these two models superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation of ~2 Å. The overall molecular folds are similar, but there are significant differences in the way the nucleotide-linked sugars are accommodated in the active site clefts. In particular, the ribose moieties are rotated by nearly 180° as can be seen in Figure 8b. There are three residues typically conserved in SDR superfamily members, Tyr144, Lys148, and Thr119 in Cj1427 (or a serine). As expected, these side chains align well between Cj1427 and the epimerase. Due to the differences in the ribose orientations, however, the side chains of Arg204 and Arg212 in Cj1427 and the epimerase, respectively, adopt different side chain torsional angles. The most striking changes occur at Arg177 and Arg270 where in the epimerase these residues are Asp180 and Ile273, respectively. These residues in Pal correspond to Gln179 and Ile276. On the basis of the docking studies described above, it has been suggested that Arg177 and Arg270 may, indeed, be important for anchoring the α-ketoglutarate into the active site.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the Cj1427 structure with other members of the SDR superfamily. Shown in stereo in (a) is a ribbon presentation of the Cj1427 subunit (teal) onto that for UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase (gray) (PDB code 6DNT). A closeup stereo view of their respective active sites is provided in (b). Those residues and ligands belonging to Cj1427 are highlighted in teal whereas those corresponding to the epimerase are colored in wheat and orange bonds. The top and bottom labels correspond to those residues in Cj1427 and the epimerase, respectively. Shown in (c) is a closeup stereo view of the active sites for Cj1427 (teal) and GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (wheat and orange) (PDB code 1N7G).

Both the epimerase and PAL function on UDP-linked sugar substrates. The question then arises as to whether the differences in conformation observed for the nucleotide-linked sugar ligands between these enzymes and Cj1427 is due to the guanine ring of the GDP-linked substrate. Shown in Figure 8c is a superposition of the active sites for Cj1427 and the GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase from Arabidopsis thaliana (40). Again, the ribose moieties of the nucleotide-linked sugars are rotated by nearly 180° with respect to one another and Arg270 in Cj1427 is replaced with Val318 in the dehydratase. The unusual binding conformation of the GDP-sugar in Cj1427 is due to a variety of changes, but in particular the replacement of a hydrophobic residue with Arg270. As seen in Figure 8c, the region surrounding Arg177 in Cj1427 is also decidedly different in the dehydratase with the side chain of Phe224 filling in the position occupied by that of Arg177.

In conclusion, Cj1427 and its homologues display high amino acid sequence conservation and are found in all C. jejuni strains known to contain a heptose moiety with a C6 hydroxyl group in their CPS. Cj1427 copurifies with tightly-bound NADH thus preventing it from catalyzing an oxidation reaction in the absence of other co-substrates. However, the addition of the α-ketoglutarate converts the tightly bound NADH to NAD+, and the NAD+-bound Cj1427 will catalyze the oxidation of l-2-hydroxyglutarate to α-ketoglutarate. The crystal structure of Cj1427 demonstrates that Cj1427 can bind GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose with the C4 carbon of the sugar positioned for oxidation. We propose that the unrecognized requirement of α-ketoglutarate was the previous missing component for the oxidation of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) to GDP-d-glycero-4-keto-α-d-lyxo-heptose (2). We believe Cj1427, along with Cj1430 and Cj1428, facilitate the transformation from GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1) to GDP-d-glycero-β-l-gluco-heptose (4). In the subsequent publication, we demonstrate that Cj1427 does, in fact, catalyze the C4 oxidation of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose (1). Finally, it can be postulated that both the unusual quaternary structure of Cj1427 and the manner in which the enzyme binds a GDP-linked sugar will also be observed in its homologues. Importantly, Cj1427 represents the first enzyme belonging to the SDR superfamily that requires a recycling mechanism for activity.

CONCLUSIONS

The enzyme Cj1427 from Campylobacter jejuni NTCC11168 is critical for the biosynthesis of modified heptose sugars found in the capsular polysaccharide of this human pathogen. The recombinant enzyme co-purifies with tightly bound NADH, which cannot be removed except by denaturation of the protein with acid. This observation explains why the as-purified enzyme could not catalyze the oxidation of likely candidate substrates. However, the tightly bound NADH is oxidized in the presence of added α-ketoglutarate to NAD+ and l-2-hydroxyglutarate. The three-dimensional structure of the enzyme was determined in the presence of added GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose. The positioning of this potential substrate with respect to the nicotinamide moiety of NAD(H) demonstrates that C4 of the sugar moiety is ideally positioned to be oxidized. The tertiary structure of Cj1427 places the enzyme within the short-chain dehydrogenase superfamily.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM122825).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Accession Codes

Cj1427 Q0P8I7

References

- (1).Humphrey S, Chaloner G, Kemmett K, Davidson N, Williams N, Kipar A, Humphrey T, and Wigley P (2014) Campylobacter jejuni is not merely a commensal in commercial broiler chickens and affects bird welfare, mBio, 5, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Facciolà A, Riso R, Avventuroso E, Visalli G, Delia SA, and Laganà P (2017) Campylobacter: from microbiology to prevention, J Prev Med Hyg, 58, E79–E92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).García-Sánchez L, Melero B, and Rovira J (2018) Campylobacter in the Food Chain, In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research (Rodríguez-Lázaro D, Ed.), pp 215–252, Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Burnham PM, and Hendrixson DR (2018) Campylobacter jejuni: collective components promoting a successful enteric lifestyle, Nat. Rev. Microbiol, 16, 551–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Godschalk PC, Kuijf ML, Li J, St Michael F, Ang CW, Jacobs BC, Karwaski MF, Brochu D, Moterassed A, Endtz HP, van Belkum A, and Gilbert M (2007) Structural characterization of Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharide outer cores associated with Guillain-Barre and Miller Fisher syndromes, Infect. Immun, 75, 1245–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gilbert M, Karwaski MF, Bernatchez S, Young NM, Taboada E, Michniewicz J, Cunningham AM, and Wakarchuk WW (2002) The genetic bases for the variation in the lipo-oligosaccharide of the mucosal pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni. biosynthesis of sialylated ganglioside mimics in the core oligosaccharide, J. Biol. Chem, 277, 327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Michael FS, Szymanski CM, Li J, Chan KH, Khieu NH, Larocque S, Wakarchuk WW, Brisson J-R, and Monteiro MA (2002) The structures of the lipooligosaccharide and capsule polysaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni genome sequenced strain NCTC 11168, Eur. J. Biochem, 269, 5119–5136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Monteiro MA, Noll A, Laird RM, Pequegnat B, Ma Z, Bertolo L, DePass C, Omari E, Gabryelski P, Redkyna O, Jiao Y, Borrelli S, Poly F, and Guerry P (2018) Campylobacter jejuni capsule polysaccharide conjugate vaccine, In Carbohydrate-based vaccines: from concept to clinic, pp 249–271, American Chemical Society. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Huddleston JP, and Raushel FM (2019) Biosynthesis of GDP-d-glycero-α-d-manno-heptose for the capsular polysaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni, Biochemistry, 58, 3893–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kneidinger B, Graninger M, Puchberger M, Kosma P, and Messner P (2001) Biosynthesis of nucleotide-activated d-glycero-d-manno-heptose, J. Biol. Chem, 276, 20935–20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).McCallum M, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2011) Characterization of the dehydratase WcbK and the reductase WcaG involved in GDP-6-deoxy-d-manno-heptose biosynthesis in Campylobacter jejuni, Biochem. J, 439, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).McCallum M, Shaw SD, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2012) Complete 6-Deoxy-d-altro-heptose biosynthesis pathway from Campylobacter jejuni, J. Biol. Chem, 287, 29776–29788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).McCallum M, Shaw GS, and Creuzenet C (2013) Comparison of predicted epimerases and reductases of the Campylobacter jejuni D-altro- and l-gluco-heptose synthesis pathways, J. Biol. Chem, 288, 19569–19580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Huddleston JP, Thoden JB, Dopkins BJ, Narindoshvili T, Fose BJ, Holden HM, and Raushel FM (2019) Structural and functional characterization of YdjI, an aldolase of unknown specificity in Escherichia coli K12, Biochemistry, 58, 3340–3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Huddleston JP, and Raushel FM (2019) Functional characterization of YdjH, a sugar kinase of unknown specificity in Escherichia coli K12, Biochemistry, 58, 3354–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding, Anal. Biochem, 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S. e., Wilkins MR, Appel RD, and Bairoch A (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server, In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker JM, Ed.), pp 571–607, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Taylor ZW, Brown HA, Holden HM, and Raushel FM (2017) Biosynthesis of nucleoside diphosphoramidates in Campylobacter jejuni, Biochemistry, 56, 6079–6082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, and Chruszcz M (2006) HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution-from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 62, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Ness SR, de Graaff RAG, Abrahams JP, and Pannu NS (2004) Crank: New methods for automated macromolecular crystal structure solution, Structure, 12, 1753–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Laskowski RA, Moss DS, and Thornton JM (1993) Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures, J Mol Biol, 231, 1049–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, and Olson AJ (2009) AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility, journal of computational chemistry 30, 2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Trott O, and Olson AJ (2009) AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading, Journal of Computer Chemistry, 31, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bianco G, Forli S, Goodsell DS, and Olson AJ (2016) Covalent docking using autodock: Two-point attractor and flexible side chain methods, Protein Science, 25, 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Rudolph J, Kim J, and Copley SD (2010) Multiple turnovers of the nicotino-enzyme PdxB require alpha-keto acids as cosubstrates, Biochemistry, 49, 9249–9255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Thoden JB, and Holden HM (2010) Structural and functional studies of WlbA: A dehydrogenase involved in the biosynthesis of 2,3-diacetamido-2,3-dideoxy-D-mannuronic acid, Biochemistry, 49, 7939–7948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Larkin A, and Imperiali B (2009) Biosynthesis of UDP-GlcNAc(3NAc)A by WbpB, WbpE, and WbpD: enzymes in the Wbp pathway responsible for O-antigen assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, Biochemistry, 48, 5446–5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zhao G, and Winkler ME (1996) A novel α-ketoglutarate reductase activity of the serA-encoded 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli K-12 and its possible implications for human 2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria, J. Bacteriol, 178, 232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Persson B, Kallberg Y, Bray JE, Bruford E, Dellaporta SL, Favia AD, Duarte RG, Jornvall H, Kavanagh KL, Kedishvili N, Kisiela M, Maser E, Mindnich R, Orchard S, Penning TM, Thornton JM, Adamski J, and Oppermann U (2009) The SDR (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase and related enzymes) nomenclature initiative, Chemico-biological interactions, 178, 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Riegert AS, Thoden JB, Schoenhofen IC, Watson DC, Young NM, Tipton PA, and Holden HM (2017) Structural and biochemical investigation of PglF from Campylobacter jejuni reveals a new mechanism for a member of the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily, Biochemistry, 56, 6030–6040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kavanagh KL, Jörnvall H, Persson B, and Oppermann U (2008) Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families : the SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes, Cell Mol Life Sci, 65, 3895–3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).DeLano WL (2002) The PyMOL molecular graphics system, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Butty FD, Aucoin M, Morrison L, Ho N, Shaw G, and Creuzenet C (2009) Elucidating the formation of 6-deoxyheptose: biochemical characterization of the GDP-d-glycero-d-manno-heptose C6 dehydratase, DmhA, and its associated C4 reductase, DmhB, Biochemistry, 48, 7764–7775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Krissinel E, and Henrick K (2004) Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Carbone V, Schofield LR, Sang C, Sutherland-Smith AJ, and Ronimus RS (2018) Structural determination of archaeal UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase from Methanobrevibacter ruminantium M1 in complex with the bacterial cell wall intermediate UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid, Proteins 86, 1306–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Delvaux NA, Thoden JB, and Holden HM (2018) Molecular architectures of Pen and Pal: Key enzymes required for CMP-pseudaminic acid biosynthesis in Bacillus thuringiensis, Protein Sci 27, 738–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Mulichak AM, Bonin CP, Reiter WD, and Garavito RM (2002) Structure of the MUR1 GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase from Arabidopsis thaliana: implications for ligand binding and specificity, Biochemistry 41, 15578–15589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]