Abstract

Locally advanced gastric cancer (GC) is often managed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery; however, pathological complete responses to preoperative systemic treatment are rare. Some GCs are characterised by high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and therefore are potentially sensitive to anti-PD1 (the programmed death 1) therapy. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade demonstrated promising results in a number of trials involving various categories of patients with cancer; therefore, we considered feasible to offer preoperative nivolumab to a patient with T3N1M0 MSI-H GC. The patient experienced a reduction of the tumour size and the analysis of surgical material revealed complete elimination of tumour cells. MSI-H status deserves to be considered in future trials on patients with GC.

Keywords: gastric cancer, gastrointestinal system, immunology

Background

Systemic chemotherapy is a standard treatment option for locally advanced gastric cancer (GC) in many countries across the world. Neoadjuvant drug administration increases the probability of complete surgical removal of the tumour, prevents early cancer spread and helps to rapidly evaluate whether the GC disease is sensitive to therapeutic intervention. Several cytotoxic combinations have been approved for GC management, including FLOT (docetaxel 60 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2 and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 2600 mg/m2 as a 24-hour infusion), ECF (epirubicin 50 mg/m2 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, with continuous infusion of 5-FU 200 mg/m2 per day), FOLFOX (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 and leucovorin 400 mg/m2 (or l-leucovorin 200 mg/m2) as a 2-hour infusion, followed by 5-FU 400 mg/m2 as a bolus and 2400 mg/m2 as a 46-hour infusion) and DCF (intravenous docetaxel 60–70 mg/m2 and cisplatin 60–70 mg/m2 on day 1, and a continuous infusion of 5-FU 750–800 mg/m2 per day for 5 days). There are evidences suggesting that neoadjuvant therapy may improve the overall survival of patients with GC, although the available studies have been criticised for deficiencies in their design and data interpretation. While the clinical utility of preoperative therapy for GC remains the subject of debate, it is beyond a doubt that pathological complete response (pCR) is a reliable predictor of very good prognosis. Unfortunately, complete elimination of cancer cells rarely occurs after neoadjuvant therapy, and there are no predictive tools to evaluate the feasibility of the upfront drug treatment in any given patient with GC.1–4

Inhibitors of immune checkpoints have been recently incorporated in the treatment schemes for many tumour varieties, including GC. These drugs are particularly effective in tumours with high mutation burden, as the latter have a high antigen load. Consequently, anti-PD1 drugs demonstrated remarkable efficacy in microsatellite-unstable carcinomas of various categories, including GC.5–8 The frequency of microsatellite instability (MSI) in GC varies within 5.6%–33%, depending on the mode of patient recruitment and the method of MSI determination.5 7–9 There are recent reports describing a pCR in patients with high-level MSI (MSI-H) colorectal cancer, which were subjected to neoadjuvant therapy by nivolumab or pembrolizumab.10 11 Here, we describe patient with MSI-H GC, who also experienced pCR in response to neoadjuvant nivolumab

Case presentation

The patient, a woman of 64 years, requested medical examination in March 2019 due to severe fatigue, dyspnoea and chest pain starting from November 2018. Blood test revealed a pronounced anaemia (haemoglobin 54 g/L). Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy detected an exophytic pyloric tumour with an ulcerated surface. Histological examination classified this neoplasm as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. MSI analysis was performed using a standard panel of mononucleotide markers and revealed an MSI-H status.12 PD-L1 immunohistochemical staining was detected in more than 1% of tumour cells, while the test for HER2 overexpression was negative. CT scan estimated the size of the lump to be 60×54×44 mm, with no invasion to serosa. There were metastases in infrapyloric lymph nodes (up to 5 mm), while no distant tumour spread was detected. Diagnostic laparoscopy revealed no tumour cells in the peritoneal lavage. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT was performed at the beginning of June 2019. It revealed primary tumour lump with the size 41×36 mm and standardised uptake value (SUV) 16.3. Thus, this disease was considered to be a locally advanced MSI-H GC, cT3N1M0 (stage III, TNM 8th ed.

Treatment

The staging of the tumour disease in this patient called for the use of neoadjuvant therapy. We considered that the commonly accepted cytotoxic regimens rarely result in a complete elimination of tumour cells.1–4 At the same time, there is a number of published neoadjuvant anti-PD1 trials, which involved distinct categories of patients with cancer; although these trials often did not use rigorous selection of the study participants, they produced generally encouraging results.13 14 MSI-H is a strong predictor of tumour sensitivity to the immune checkpoint blockade, and neoadjuvant immune therapy produced spectacular tumour responses in some patients with MSI-H colorectal cancer.15 16 Therefore, we considered ethical to offer to the patient neoadjuvant nivolumab as an experimental preoperative treatment. Personal preferences of the patient played a role in this decision, as she was reluctant to canonical cytotoxic therapy and strongly desired to receive novel cancer drugs. She signed the informed consent and started the therapy on 14 June 2019 (nivolumab 3 mg/kg intravenous, every 14 days). Six cycles were performed without any clinically significant adverse effects. CT scan was performed on 7 August 2019, after 4 cycles of nivolumab therapy (table 1). There was a significant reduction of the primary tumour size classified as partial response (figure 1).

Table 1.

Neoadjuvant nivolumab treatment of high-level microsatellite instability gastric cancer

| Baseline | After 4 cycles | After 6 cycles | |

| Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy | Exophytic tumour 3.5 cm long with an ulcerated surface | Tumour shrinkage up to 3 cm | Peptic ulcer up to 10 mm with mucosa infiltration |

| CT scan | The primary tumour with the size 60×54×44 mm, no invasion to serosa | Thickening of the wall in the distal portion of the large curvature, with the spread to pylorus; up to 14 mm in height, about 3 cm long | – |

| FDG-PET-CT | The primary tumour with the size 41×36 mm and SUV 16.3 | – | Thickening of the wall in the distal part of the gastric, SUV 1,4 |

| Histology | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | – | No residual tumour cells. Fragments of erosion, hyperplastic gastric mucosa with fibrosis and focal inflammation. |

FDG-PET-CT, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT; SUV, standardised uptake value.

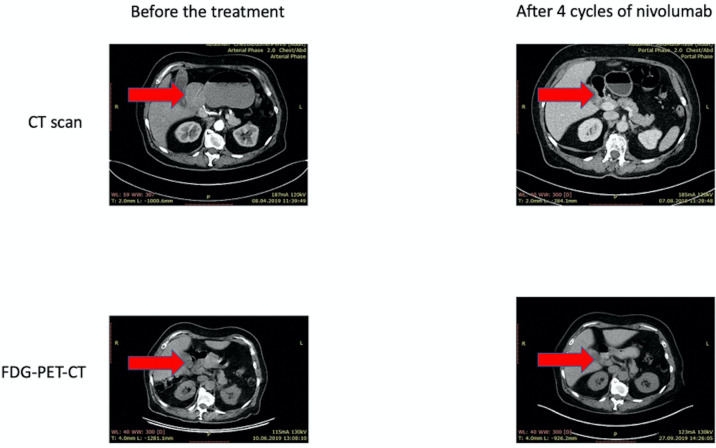

Figure 1.

Radiological response to neoadjuvant treatment with nivolumab. Abdominal CT and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT (FDG-PET-CT) scans of the patient receiving neoadjuvant therapy for high-level microsatellite instability gastric cancer. Significant tumour shrinkage is observed after 4 cycles of nivolumab treatment.

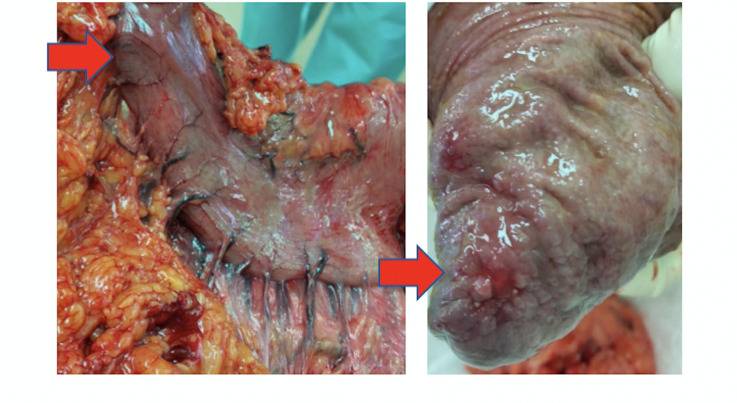

The patient was examined by diagnostic laparoscopy on 6 November 2019 and then underwent distal subtotal resection of the stomach (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Surgical resection specimen: macroscopic response of the primary tumour to the neoadjuvant nivolumab treatment. The lesion observed at surgery resembles cancer lump. However, morphological examination revealed only fibrosis and inflammation, with no evidence for the presence of cancer cells.

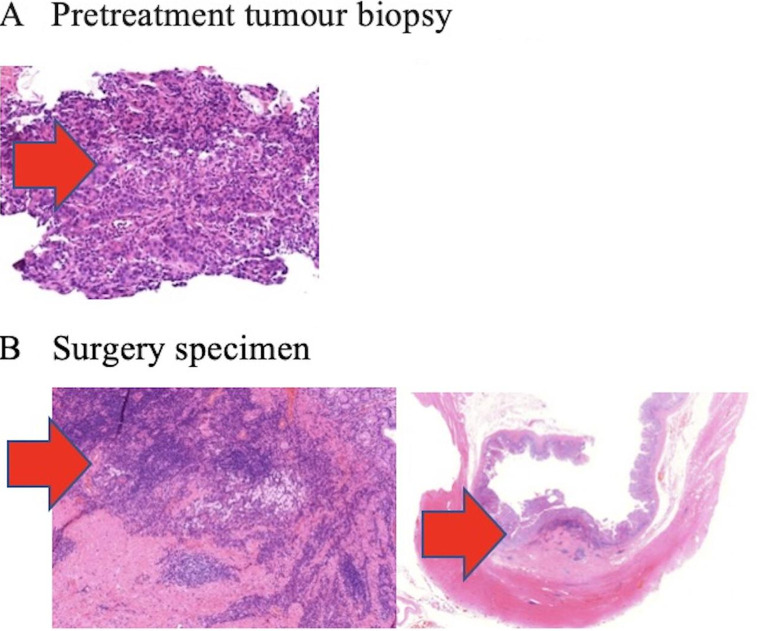

The postoperative histological examination revealed no residual tumour cells in the excised tissues. The microscopic analysis of the tumour bed detected fibrosis and infiltration by lymphocytes, plasmocytes and foamy macrophages. The examination also included 10 lymph nodes from the lesser curvature and 2 lymph nodes from the large curvature. None of them contained metastatic cells, while two lymph nodes had focal fibrosis (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Complete pathological response to neoadjuvant treatment with nivolumab. (A) Representative section of the poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma obtained before the administration of neoadjuvant therapy. (B) No viable cancer cells are detected after 6 cycles of nivolumab. There are fibrosis and infiltration by lymphocytes, plasmocytes and foamy macrophages.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient received 2 cycles of the adjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab. Currently, she is under observation (ECOG 0) with no signs of the disease relapse.

Discussions

Several clinical trials involving neoadjuvant use of immune checkpoint inhibitors have been published recently.17–21 They demonstrate remarkable efficacy in various types of cancer, which are characterised by a high mutation burden. Although the direct comparison is complicated, there is an impression that immune therapy produced somewhat better response and cure rates in neoadjuvant than in metastatic cancer setting. Furthermore, neoadjuvant immune therapy may outperform conventional cytotoxic drug combinations when considering the available options for preoperative treatment.17–21

Microsatellite unstable cancers and some other cancers characterised by deficient DNA repair are outliers with regard to the antigen burden, as the number of mutations in these cancers may exceed the average by two orders of magnitude. As a consequence, these tumours are characterised by particularly pronounced response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.5–8 21 MSI-H tumours are relatively infrequent and are characterised by a more favourable disease course as compared with unselected cancers.22 Therefore, it is complicated to perform head-to-head comparison of chemosensitivity of MSI-H versus microsatellite-stable cancers in metastatic or neoadjuvant setting. Nevertheless, the already available evidences indicate that immune therapy is at least non-inferior and probably superior to cytotoxic therapy when MSI-H cancers are considered as a separate tumour entity. Present report provides additional support to this statement.

Patient’s perspective.

My illness started with severe weakness and pain, which did not allow me to serve myself. After diagnostic measures, I was diagnosed with gastric cancer and I was very afraid of the planned operation. In this regard, I was happy to start immunotherapy treatment. I felt myself well during infusions of immunotherapy, and the CT results and absence of complaints made me very happy. The operation showed that the entire tumour had disappeared. Today, nothing bothers me, I can carry out my normal activities.

Learning points.

This clinical case demonstrates complete pathological response of high-level microsatellite instability gastric cancer to neoadjuvant nivolumab.

Complete pathological response is highly predictive for long-term survival or even cure.

Microsatellite instability status needs to be considered in future neoadjuvant trials on patients with gastric cancer.

Footnotes

Contributors: Due to the rapid progression of locally advanced gastric cancer after perioperative chemotherapy in routine clinical practice, our Center attempts to individualise treatment based on predictive biomarkers. After presenting a patient with MSI-H gastric cancer at MTD by the medical oncologist GI and conducting a scientific discussion with the Head of the Cancer Center VM, Head of the genetic laboratory EI, Head of the CT Department VC, an attempt was made to individualise the immunotherapy of the patient taking into account genetic disorders. This strategy was based on the clinical experience of the Head of the Cancer Center VM and the Head of the CT Department VC, which included achieving an extremely high objective response of the MSI-H disseminated tumours of the various locations. Medical oncologist GI carried out the immunotherapy for the patient in the CT Department under the guidance of VC. Consultations in the scientific group, which included all authors, as well as employees of the Department of endoscopy, radiology and abdominal surgeons, were performed at each cycle of immunotherapy. Our team has not found similar studies in locally advanced gastric cancer, taking into account the molecular marker, in the literature. Therefore, taking into account the positive effect of this treatment with CPI and the absence of the toxicity, VC prepared the manuscript draft with important intellectual input from EI and VM. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant 17-75-30027).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cho H, Nakamura J, Asaumi Y, et al. Long-Term survival outcomes of advanced gastric cancer patients who achieved a pathological complete response with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:787–92. 10.1245/s10434-014-4084-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bringeland EA, Wasmuth HH, Grønbech JE. Perioperative chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer - what is the evidence? Scand J Gastroenterol 2017;52:647–53. 10.1080/00365521.2017.1293727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imyanitov EN, Yanus GA. Neoadjuvant therapy: theoretical, biological and medical consideration. Chin Clin Oncol 2018;7:55. 10.21037/cco.2018.09.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell MC. Comparison of neoadjuvant versus a surgery first approach for gastric and esophagogastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 2016;114:296–303. 10.1002/jso.24293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e180013. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 2017;357:409–13. 10.1126/science.aan6733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1182–91. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30422-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janjigian YY, Bendell J, Calvo E, et al. CheckMate-032 study: efficacy and safety of nivolumab and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2836–44. 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratti M, Lampis A, Hahne JC, et al. Microsatellite instability in gastric cancer: molecular bases, clinical perspectives, and new treatment approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018;75:4151–62. 10.1007/s00018-018-2906-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Cai J, Deng Y, et al. Complete response in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant treatment with nivolumab. Oncoimmunology 2019;8:e1663108. 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1663108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanus GA, Belyaeva AV, Ivantsov AO, et al. Pattern of clinically relevant mutations in consecutive series of Russian colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol 2013;30:686. 10.1007/s12032-013-0686-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaria RN, Reddy SM, Tawbi HA, et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in high-risk resectable melanoma. Nat Med 2018;24:1649–54. 10.1038/s41591-018-0197-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin H, Li P, Mao C, et al. Pathological complete response after a single dose of anti-PD-1 therapy in combination with chemotherapy as a first-line setting in an unresectable locally advanced gastric cancer with PD-L1 positive and microsatellite instability. Onco Targets Ther 2020;13:1751–6. 10.2147/OTT.S243298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Cheng S, Gong J, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with microsatellite instability-high gastrointestinal malignancies: a case series. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020. 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demisse R, Damle N, Kim E, et al. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy-Based systemic treatment in MMR-Deficient or MSI-High rectal cancer: case series. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18:798–804. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu D-X, Li D-D, He W, et al. PD-1 blockade in neoadjuvant setting of DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 2020;9:1711650. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1711650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blank CU, Rozeman EA, Fanchi LF, et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat Med 2018;24:1655–61. 10.1038/s41591-018-0198-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1976–86. 10.1056/NEJMoa1716078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang AC, Orlowski RJ, Xu X, et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med 2019;25:454–61. 10.1038/s41591-019-0357-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Necchi A, Anichini A, Raggi D, et al. Pembrolizumab as neoadjuvant therapy before radical cystectomy in patients with muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma (PURE-01): an open-label, single-arm, phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:3353–60. 10.1200/JCO.18.01148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkov NM, Yanus GA, Ivantsov AO, et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in MUTYH-associated hereditary colorectal cancer. Invest New Drugs 2020;38:894–8. 10.1007/s10637-019-00842-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilar E, Gruber SB. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer-the stable evidence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010;7:153–62. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]